Abstract

A growing body of research has demonstrated that teachers’ judgements may be biased by the demographics and characteristics of the students they teach. However, less work has investigated the contexts in which teachers may be most vulnerable to bias. In two pre-registered experimental studies we explored whether the quality of students’ work, and the cognitive load placed on the grader, would influence the emergence of biases relating to socioeconomic status (SES) and ethnicity. In Study 1, teachers (N = 397) graded work of either high or low quality that had ostensibly been written by a student who varied in terms of SES and ethnicity. We found that SES and—to a lesser extent—ethnicity biases were more likely to manifest when the standard of work was below average, largely favouring a student from an affluent White background. In Study 2, an undergraduate sample (N = 334) provided judgements based on an identical piece of work written by a student who varied by SES and ethnicity. Importantly, they formulated these judgements whilst working under high or low cognitive load, which was manipulated via a simultaneous listening task. Results showed that under high cognitive load, a student from an affluent White British background was afforded a boost in grading that was not afforded to Black Caribbean and/or lower SES students. These findings highlight contexts in which teachers may be most prone to biased judgements and should be used by educational institutions to de-bias their workflows, workloads and workforces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Many teachers enter the profession motivated to make a positive social contribution (Watt & Richardson, 2007) yet, paradoxically, they tend to have similar levels of implicit (or unconscious) bias against certain groups as the general population (Starck et al., 2020). Indeed, a growing body of research suggests that teachers’ biased expectations for students from different socioeconomic, gender, migration, and racial/ethnic backgrounds can contribute to educational inequalities. These biases have been shown to result in disparate grading (Anderson-Clark et al., 2008; Bonefeld & Dickhäuser, 2018; Doyle et al., 2023a; Lievore & Triventi, 2023), interactions (Goudeau et al., 2023; İnan-Kaya & Rubie-Davies, 2022; Tenenbaum & Ruck, 2007), disciplinary sanctions (Jarvis & Okonofua, 2020; Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015), and school placements (Batruch et al., 2023; Glock et al., 2015). By contrast, while research has identified links between teacher biases and differential educational outcomes, little is known about the conditions under which these biases are more, or less, likely to emerge. In the wider literature, research has shown that stereotypical judgements may be more likely to be manifested at certain times of the day (Bodenhausen, 1990), when judges are hungry (Danziger et al., 2011), and when the information provided confirms a particular stereotype about the target’s group (Bonefeld & Dickhäuser, 2018). Over two studies, we aim to address two contextual gaps in the teacher bias literature by exploring whether teachers’ socioeconomic and ethnicity biases are influenced by a) the quality of students’ work (performance level), and b) the quantity of teachers’ work (cognitive load).

1.1 Theoretical background

In the United Kingdom, where the current research took place, the starkest educational inequalities tend to fall along socioeconomic and—to a slightly lesser extent—ethnic/racial lines (Department for Education, 2022). The following sections highlight these inequalities, how teacher biases may play a role in their perpetuation, and why research focusing on the conditions under which teachers’ socioeconomic status (SES) and ethnicity biases may be most prominent constitutes an important and timely area of study.

1.1.1 Students’ ethnicity

The attainment of Black Caribbean students trails that of their White British peers by an average of almost 11 months of learning by the end of compulsory education in England (Hutchinson et al., 2020). As a result, they tend to underperform compared to national averages when completing their General Certificates of Secondary Education (GCSEs; Department for Education, 2022). There are myriad causes for these inequalities, but we focus here on the potential role of teachers and schools. Black students in the UK tend to be under-rated by their teachers (Burgess & Greaves, 2013; Campbell, 2015; Connolly et al., 2019; Strand, 2012) and are held to lower academic expectations compared to their peers (Gillborn et al., 2012). Additionally, research in the US has revealed that teachers’ racial and ethnic biases can result in harsher grading for those with typically Black names (Anderson-Clark et al., 2008), greater behavioural surveillance for Black boys (Gilliam et al., 2016), and harsher disciplinary action against Black students (Jarvis & Okonofua, 2020; Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015).

1.1.2 Students’ socioeconomic status

Students eligible for free school meals (FSM)—often used as a proxy for low SES—also tend to perform considerably worse in their GCSEs, and trail non-eligible students by the equivalent of 18 months’ worth of learning by the end of compulsory education (Department for Education, 2022; Hutchinson et al., 2020). Both correlational (Anders et al., 2021; Campbell, 2015; Goudeau et al., 2023) and experimental (Batruch et al., 2017, 2019, 2023; Doyle et al., 2023a; Dunne & Gazeley, 2008; Glock & Kleen, 2020; Pit-ten Cate & Glock, 2018) research have shown that teachers’ judgements on various tasks may be biased by knowledge of their students’ SES. In one example (Doyle et al., 2023a), teachers were shown an identical piece of written work but were led to believe that it had been written by a student who varied in SES (higher or lower) and ethnicity (White British or Black Caribbean). Despite reading the exact same piece of work, those who believed it had been written by a student from a lower SES background assigned the work a lower grade and allocated the student to a lower ability group. However, there was no evidence of ethnicity bias or a two-way interaction between SES and ethnicity in the teacher sample. The authors suggest a possible reason for this is that teachers are more aware of racial and ethnicity biases than class and socioeconomic biases and are therefore better able to monitor and inhibit them when they have time and care to do so. We therefore sought to test whether certain contexts were more likely than others to yield biased judgements in education settings.

1.1.3 Contextual factors: performance level

Firstly, we explored the possibility that the quality of a students’ work may influence the emergence of teacher bias. Although student performance could be viewed as a student factor, we argue that it also provides a context for teachers’ judgements, thereby potentially altering the extent to which students’ uncontrollable characteristics influence grading. Indeed, Batruch et al. (2017) found that pre-service teachers gave harsher judgements to low-SES students when they were presented as being high achievers, thereby leading the authors to suggest that in the face of stereotype-disconfirming information these teachers acted to restore the social class order. If true, this would suggest that students from typically lower-performing groups may be subject to more bias when they produce higher quality work. By contrast, other studies have shown that bias may be more pronounced for stereotype-confirming information, with students from typically low-performing migrant backgrounds being subject to more negatively biased judgements when their performance level was low (Bonefeld & Dickhäuser, 2018; Glock & Krolak-Schwerdt, 2013). However, these studies only investigated bias in relation to one student characteristic (e.g., migration status), which could also be strongly associated with another (e.g., SES), thus leading to the possibility that the reported effects were due to a combination of factors. Here we attempt to separate the different effects of SES and ethnicity in the UK context by manipulating both variables simultaneously.

1.1.4 Contextual factors: cognitive load

The emergence of bias may also be influenced by teachers’ environment and workload. Research suggests that high levels of cognitive load can induce more biased judgements in a range of tasks from simple sentence completion (Blair & Banaji, 1996) to more real-life scenarios in healthcare (Burgess, 2010), law-enforcement (Singh et al., 2020), and potentially education (Feldon, 2007; İnan-Kaya & Rubie-Davies, 2022). The theory behind this is often described using Kahneman’s (2011) two systems: system 1 makes fast, automatic, and emotional judgements, whereas system 2 makes slow, deliberative, considered decisions. When cognitive load is increased, system 2 becomes occupied with attending to the draining demands of the task(s), leaving system 1 to make snap judgements based on heuristics and pre-defined time-saving categories (e.g., stereotypes). Therefore, if teachers are cognitively overloaded, it is possible that their judgements may exhibit more bias than would be the case if they had the time and headspace to make conscious and deliberate decisions. As teachers often feel overworked and overwhelmed (Marken & Agrawal, 2022), we believe this is a timely and important area of study that should resonate with educators, school boards and policymakers alike.

1.2 Current studies

In two pre-registered studies, we added to the existing literature by experimentally testing whether SES and ethnicity biases in academic-related judgements were more or less likely to emerge when the quality of student’s work was above or below the expected level for an 11-year old (Study 1) and when the grader was working under high cognitive load (Study 2).

2 Study 1: students’ performance level

In Study 1, we firstly tested whether teachers exhibited SES and ethnicity biases, and secondly whether these would be more likely to emerge for stereotype-confirming (e.g., Bonefeld & Dickhäuser, 2018) or stereotype-disconfirming (e.g. Batruch et al., 2017) levels of student performance. We pre-registered the following hypothesesFootnote 1:

H1

Students of lower SES will receive harsher judgements (e.g. lower grades, ability group allocations and perceived levels etc.) than those of higher SES.

H2

Specifically, there will be an interaction between SES and performance in which the effect of SES bias is most pronounced at high levels of performance.

H3

Black students will be graded more harshly (e.g. lower grades, ability group allocations and perceived levels etc.) than those from white backgrounds.

H4

Specifically, there will be an interaction between ethnicity and performance in which the effect of ethnicity bias is greater when performance level is high.

In line with previous research (Doyle et al., 2023a), we did not expect any significant two-way interactions between SES and ethnicity. By contrast, despite not pre-registering any specific hypotheses about three-way interactions, we were interested to test the conditions under which students at different intersections of SES and ethnicity would be most (dis)advantaged by teacher bias. For example, when are White British students from higher SES backgrounds (the most privileged SES-ethnicity combination in our design) most likely to gain advantageous judgements from their teachers?

2.1 Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the host university’s ethics review committee.

2.1.1 Sample

We carried out power analyses using both G*Power (Faul et al., 2007) and the INTxPower tool (Sommet et al., 2023). Based on previous research using a similar design (Doyle et al., 2023a), we aimed to recruit 403 participants to obtain .80 power to detect effect sizes of d = .28 at the standard .05 alpha error probability for our predicted main effects and two-way interactions. Furthermore, we specified that we would use eight condition groups to account for the 2 × 2 × 2 design, as we were interested in exploring the three-way interactions, despite not making any explicit hypotheses about these. In total, 449 teachers were recruited via the Prolific platform to take part in a 12-min study about education and were paid £1.30 for their time. Fifty-two participants were excluded for failing at least one pre-registered manipulation check, leaving a final sample of N = 397 (MAge = 39.72, SDAge = 10.53; 79.5% female, 19.4% male, 0.8% non-binary, 0.3% preferred not to disclose their gender; 90.7% White, 4.5% Asian or mixed Asian and White, 2% Black or mixed Black and White, 2.3% other ethnicity, 0.5% preferred not to disclose their ethnicity). Additionally, 17.6% had been eligible for free school meals during their childhood.

2.1.2 Design

Participants were randomly allocated to one of eight conditions as part of a 2 (SES: coded 0 = Higher, 1 = Lower) × 2 (Ethnicity: coded 0 = White British, 1 = Black Caribbean) × 2 (Performance level: coded 0 = Above expected standard, 1 = Below expected standard) independent measures design.

2.1.3 Materials

2.1.3.1 SES and ethnicity manipulation

Participating teachers viewed one of four Year 6 studentFootnote 2 records which had been made to vary by SES and ethnicity. These followed a similar design to those used in previous research (Batruch et al., 2017; Doyle et al., 2023a). SES was manipulated via fields such as eligibility for free school meals (No or Yes) and parental occupation (e.g., doctor or cleaner). Ethnicity was manipulated by name (typically White name, Ollie, or typically Black name, Omari), an ethnicity field (White British or Black Caribbean) and a photo of the student (White or Black) which had been pilot tested and matched on dimensions warmth, competence, and attractiveness (there were no significant differences between faces; N = 30; ps > .90). Participants were told that the student attended a state primary school in England with average pupil demographics and attainment. As a cover story, and to encourage absorption of the key details, we asked participants to highlight information on the student record that they believed would be a confidentiality breach to share with people who were not directly linked to the education or well-being of the child. At the end of the study, participants responded to two manipulation check questions that asked them to recall the ethnicity of the target student and to predict whether the student and their family would have above or below average income relative to other members of society.

2.1.3.2 Performance level manipulation and grading task

Performance was manipulated by the quality of the written work presented to participants. Those in the high performing conditions read an identical piece of handwritten work by a student who was working above the expected level for their age. Conversely, those in the low performing conditions all read the same piece of work by a student who was working below the expected level. The examples of writing (and their grades) were genuine and were taken from KS2 writing standardisation exercises (Standards & Testing Agency, 2019; see Appendices 1 and 2 in the supplementary materials). In each instance, participants were informed that this was the work of the student whose record they had just read and were asked to provide a grade (1 = poor, 10 = excellent), allocate them to an English set (ability group; 1–5), report how many errors there were (0–20), decide whether the student was working below, at, or above the expected standard for their age, estimate the student’s scaled score in their Key Stage 2 SATsFootnote 3 (80–120), and give a subjective judgement of the student’s performance from 1 (awful) to 7 (excellent).

2.1.3.3 Control variables

We also took measures of awareness of bias in education (adapted from Iyer et al., 2003), internal and external motivations to respond without prejudice (Plant & Devine, 1998), socially desirable responding (Reynolds, 1982), recent participation in diversity training, and the proportion of children at their current schools who were a) eligible for free school meals, and b) from ethnic minority backgrounds.

2.1.4 Procedure

Participants were initially presented with a student record featuring data that hinted at both the SES and ethnicity of the target student and completed a bogus confidentiality task to ensure engagement with the information. Immediately afterwards, participants read and assessed a piece of written work that was either above or below the expected standard for year 6 (age 10–11), and that had ostensibly been written by the student whose record they had just read. Finally, participants completed several individual difference measures, provided demographic details, and were fully debriefed.

2.2 Results

Descriptive statistics for each outcome can be found in the supplementary materials (Tables S1–S6). To test for main effects, we specified six separate linear models using the ‘robust’ package in R (Wang et al., 2022), predicting each of the six judgement outcomes (e.g., grade, set allocation etc.) from student SES, ethnicity, and performance level,Footnote 4Footnote 5 (see Table 1, Model 1 for full results). We then explored whether the three predictor variables would interact to show bias in certain situations but not others. Once again, we specified six separate robust linear models with judgement outcomes predicted by SES, ethnicity and performance level, as well as the two and three-way interactions between themFootnote 6 (see Table 1, Model 2 for full results). Finally, although not specified in our pre-registered analysis plan, we also ran a series of simple effects analyses to test the effect of SES, ethnicity, and the interaction between the two at different levels of performance (above or below average; thereby directly testing H2 and H4).

2.2.1 Grade

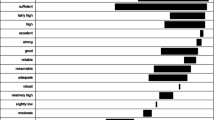

There was a significant main effect of student SES on grade judgements (b = − .48, p < .001) indicating that lower SES students were rated less favourably than higher SES students, thereby supporting H1. There was no main effect of student ethnicity (b = − .14, p = .223), thereby not supporting H3. There were two-way interactions between ethnicity and performance level (b = − .78, p = .025) and between SES and performance level (b – 1.01, p = .004), but these were qualified by a three-way interaction between SES, ethnicity, and performance (b = 1.08, p = .026). To break this interaction down, Tukey post-hoc tests and the visual representation in Fig. 1 revealed that when performance level was below the expected standard, the White British-Higher SES student was graded more favourably than the lower SES students of both White British (b = − 82, p = .019) and Black Caribbean (b = .75, p = .028) ethnicity. Meanwhile, the Black Caribbean-Higher SES student’s grade was not significantly different from that of any other student (ps > .347). Simple effects at different levels of performance confirmed that for above average performance, neither SES nor ethnicity predicted grades, whereas at low levels of performance, higher grades were significantly predicted by higher SES, b = − 1.09, SE = .27, t(195) = − 4.10, p < .001, and by being White British, b = − .66, SE .27, t(195) = − 2.48, p = .012, indicating both SES and ethnicity biases in the context of stereotype-confirming performance. Finally, in line with the full model the simple effects revealed a significant two-way interaction between SES and ethnicity at below standard performance, b = .75, SE = .38, t(195) = 2.01, p = .046, whereby higher SES White students were graded most favourably.

2.2.2 Set allocation

SES significantly predicted set allocation (b = .21, p = .019), with lower SES students being allocated to lower ability groups. There was no main effect of ethnicity (b = .00, p = .956). There were also no two-or three-way interactions. However, simple effects revealed that only when the quality of work was below average did higher SES approach significance in predicting higher set allocation, b = − .33, SE = .18, t(195) = − 1.81, p = .072. Ethnicity did not predict set allocation for either above or below average performance (see Supplementary materials Figure S1).

2.2.3 Perceived level

There was a main effect of SES on teachers’ perceptions of the students’ level (b = − .22, p = .001) with students with low SES being perceived to working at a lower level than those with high SES. There was no main effect of ethnicity (b = .02, p = .809). There were no two-or three-way interactions in the full model, but simple effects revealed that at below average performance only, lower SES predicted lower perceived level, b = − .32, SE = .15, t(195) = − 2.20, p = .029. However, ethnicity did not predict perceived level for either above or below average performance (see Supplementary materials Figure S2).

2.2.4 Objective errors

Students’ SES significantly predicted the number of objective errors that teachers reported (b = 1.13, p = .018) indicating that higher SES students were judged to have made fewer errors than those with lower SES. There was a two-way interaction between ethnicity and performance level (b = 2.70, p = .042), however, Tukey post-hoc tests revealed no significant differences between ethnicities at either above (p = .996) or below average (p = .710) performance (see Figure S3 in supplementary materials). There was no three-way interaction for errors, and no significant simple effects at either above or below average performance.

2.2.5 Scaled score

Once again, SES predicted scaled score (b = − 2.73, p < .001), with lower SES students receiving lower scores. There was no main effect of ethnicity (b = − .29, p = .682) and no two-or three-way interactions in the full model. However, simple effects revealed that for below average performance only, lower SES predicted a lower scaled score, b = − 4.34, SE = 1.52, t(195) = − 2.86, p = .005. Moreover, being White British also marginally predicted a higher score, b = − 2.42, SE = 1.45, t(195) = − 1.67, p = .097, for below average performance only (see Figure S4 in supplementary materials).

2.2.6 Subjective rating

There was a main effect of SES on teachers’ subjective ratings of students (b = − .24, p = .016), with higher SES students receiving higher ratings. There was no main effect of student ethnicity (b = .03, p = .815) and there were no two-or three-way interactions in the full model. Simple effects revealed that when performance was above average, there were no significant effects of SES or ethnicity, but for below average performers, lower SES marginally predicted lower ratings, b = − .52, SE = .27, t(195) = − 1.93, p = .055 (see Supplementary materials Figure S5).

2.2.7 Control variables

We also ran all full models with the control variables listed in the methods section and found no major differences—all significant predictors and interactions remained significant and no others became significant.

2.3 Discussion: Study 1

The results of Study 1 show that SES bias is prevalent in teachers’ judgements across a range of academic outcome variables. Moreover, these results suggest that both SES and—to a lesser extent—ethnicity biases are more likely to emerge when performance levels are below the expected standard, thus aligning with previous work showing that bias is more evident in stereotype-confirming contexts (Bonefeld & Dickhäuser, 2018; Glock & Krolak-Schwerdt, 2013).

3 Study 2: cognitive load

As teachers commonly feel overworked and overwhelmed (Marken & Agrawal, 2022), for Study 2, we tested the effects of cognitive load on judgements of academic ability. However, given such time pressures, and the challenges of carrying out online experiments—particularly those manipulating cognitive load—we opted to use a student sample. Although past research has frequently used students in the role of ‘teacher’ (e.g., Batruch et al., 2017, 2019; Jacoby-Senghor et al., 2016), we instead made the outcomes relevant to students’ own experiences by adapting the context to university level grading and students’ perceptions of suitability for a role as study skills advisor. We pre-registered several hypotheses,Footnote 7 beginning with the following main effects:

H1

Participants will give lower ratings to:

-

(a)

students from Lower (vs Higher) SES backgrounds.

-

(b)

students from Black Caribbean (vs White British) ethnic backgrounds.

We also predict that biases will be more pronounced under high cognitive load. Specifically:

H2

Under high cognitive load, participants will also give lower ratings to:

-

(a)

students from lower (vs higher) SES backgrounds compared to those in a control condition.

-

(b)

students of Black Caribbean (vs White British) ethnicity compared to those in a control condition.

As with Study 1, we made no a-priori hypotheses about three-way interactions but were keen to explore at which intersections of SES and ethnicity students would be most (dis)advantaged by teachers’ cognitive load.

3.1 Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the host university’s ethics review committee.

3.1.1 Sample

We aimed to recruit at least 200 participants through the host university’s research participation portal to have .80 power to detect a small-medium main effect size of f = .20, yet in order to add further power to our interaction effects, we pre-registered that we would continue recruitment until a pre-specified stopping date. In total 501 undergraduate students gave consent and completed a 10-min online study for course credit. Pre-registered criteria resulted in participants being excluded for failing a manipulation check about the ethnicity of the target student (n = 91), the socioeconomic background of the target student (n = 97), or both. Our final sample was N = 334 (MAge = 20.40, SDAge = 3.92). Of these, 81% identified as female, 13% male, and 4.5% non-binary, 0.3% gender fluid, and 1.2% preferred not to disclose their gender. Moreover, 75.2% reported coming from a White background, 12.7% were Asian or mixed Asian and White, 3.9% were Black or mixed Black and White, 6.1% other ethnicity, and 2.1% preferred not to disclose their ethnicity. Fifteen percent reported having been eligible for free school meals during their childhood.

3.1.2 Design

Participants were randomly allocated to one of eight conditions as part of a 2 (SES: 0 = Higher, 1 = Lower) × 2 (Ethnicity: 0 = White British, 1 = Black Caribbean) × 2 (Cognitive load: 0 = Low, 1 = High) independent measures design.

3.1.3 Materials

3.1.3.1 SES and ethnicity manipulation

Participants viewed one of four undergraduate students’ records that had been made to match the format of their university’s online portal. The students in the four records were manipulated to vary by SES and ethnicity using a similar approach to that of previous research (Batruch et al., 2017; Doyle et al., 2023a). SES was manipulated via the fields of family household income (> £100,000 or < £20,000) and parental occupation (e.g., lawyer or cleaner). Ethnicity was manipulated by name (typically White name, Charlie, or typically Black name, Omari), an ethnicity field (White British or Black Caribbean), and a photo of the student. We pilot tested the photos to ensure that they did not differ in levels of competence or attractiveness (N = 30; ps > .20). To encourage absorption of the key details, participants highlighted information on the student record that they would not want faculty members to have access to and were asked to try to remember the student’s details. At the end of the study, participants responded to the same two manipulation check questions used in Study 1 about the ethnicity and SES of the target student. Our rationale for altering the focus of the task from school children’s work to that of university students was to provide a relatable task for participants rather than one in which they had to ‘play’ the role of teacher. We argue that this increased the ecological validity of the task for the current sample.

3.1.3.2 Grading task

After reviewing the student record, participants were told they would have 2 minutes to read a short example of work by the student whose record they had just read, consider which grade they would assign it, and complete a simultaneous listening task. The example writing was an extract from an essay about children’s emotional regulation and was identical for all participants. The time limit of 2 minutes matched the length of the audio track, thereby ensuring that participants had to complete both tasks simultaneously.

3.1.3.3 Cognitive load manipulation

Cognitive load was manipulated through the content of an audio track that participants listened to whilst completing the main grading task. Those in the high cognitive load condition graded the writing whilst listening to a two-minute audio track with a number of easily identifiable sounds (e.g., cow mooing, baby crying, etc.). By contrast, those in the low cognitive load condition listened to a two-minute track of unobtrusive background white noise whilst grading the work. After 2 minutes of reading the essay and listening to the sounds, the page automatically moved on and the following questions were presented.

To check if the high cognitive load condition was indeed more challenging, participants in all conditions reported how difficult they had found the task (1. Not at all difficult—7. Extremely difficult). They were also asked to identify which sounds they had heard from a list.

3.1.3.4 Main outcomes

Participants gave judgements on the overall grade of the work in the context of UK university class bandsFootnote 8 (coded: 1 = lowest, 9 = highest), reported how likely they would be to recommend the target student for the role of student study skills advisor (a student peer mentor who may support fellow students with their studies; 1. Not at all likely, 7. Extremely likely), and how confident they would feel about taking study skills advice from this student (1. Not at all confident, 7. Extremely confident).

3.1.4 Procedure

Participants consented to take part in a study that was ostensibly about “confidentiality, study skills, and multi-tasking”. Adapting previously used experimental designs (Doyle et al., 2023a), participants were initially presented with an undergraduate student’s record that featured data hinting at both the SES and ethnicity of the target student. To engage with this information, participants completed a bogus confidentiality task. Immediately afterwards, they were informed that the researchers were interested in their ability to multi-task and that they would complete two simultaneous exercises. Participants read and assessed a piece of undergraduate work that had ostensibly been written by the student whose record they had just read. They did this whilst listening to either unobtrusive white noise (low cognitive load) or familiar sounds (high cognitive load) in headphones and were asked to identify what they had heard (see Hao & Conway, 2022 for a similar manipulation). Finally, participants completed several individual difference measures, provided demographic details, and were fully debriefed.

3.2 Results

One-way, between-participants ANOVA revealed that those in the high cognitive load conditions (M = 4.11) rated the task as significantly more difficult than did those in the low load conditions (M = 2.86), F(1, 332) = 55.48, p < .001. Descriptive statistics in Table 2 suggest that patterns of between-group difference were similar across all three outcome variables.

3.2.1 Main effects

To test for the predicted main effects (H1a and b), we first specified three separate robust linear models predicting each outcome variable (grade, recommendation, and confidence) from student SES, student ethnicity, and cognitive load.Footnote 9

Table 3, model 1 shows that for the grade outcome only, there was a significant main effect of cognitive load, whereby high cognitive load predicted a higher grade, b = .55, p = .011. However, there were no main effects of either SES (ps > .12) or ethnicity (ps > .67) on any of the outcome ratings, thus not supporting hypothesis 1.

3.2.2 Interaction effects

In order to test hypotheses 2a and 2b, we specified three separate robust linear models, this time predicting each outcome variable from student SES, student ethnicity, cognitive load, and the two-and three-way interactions between these predictorsFootnote 10 (see Table 3, Model 2).

3.2.2.1 Grade

For the Grade outcome, the full model revealed a significant main effect of ethnicity, with Black Caribbean students overall receiving higher grades than White British students (b = .82, p = .031). Moreover, under high cognitive load, participants gave significantly higher grades than did those in the low-load condition (p = 1.65, p < .001). There was no effect of SES (p = .132). There were significant two-way interactions between ethnicity and cognitive load (b = − 1.67, p = .003), SES and cognitive load (b = − 1.73, p = .001), and a marginally significant interaction between ethnicity and SES (b = − 1.10, p = .051). However, all of these effects were qualified by a significant three-way interaction between ethnicity, SES and cognitive load (b = 2.18, p = .007). Figure 2 shows that under low cognitive load, there were no significant differences between the groups’ scores, whereas, under high cognitive load, differences emerged. Post-hoc Tukey multiple comparisons of means tests revealed that the only significant effect between cognitive load conditions was for the higher SES-White British student, who was awarded a significantly more favourable grade when participants were under high (vs low) cognitive load (Mdiff = 1.65 [95% CIs .54, 2.71], p < .001).

3.2.2.2 Recommendation for the role of study skills advisor

In the full model predicting participants’ ratings of recommendation for the student to become a study skills advisor, there was no main effect of either ethnicity or SES. However, once again, those in the high cognitive load condition gave more favourable ratings than those in the low load condition (b = .96, p = .009). There was a significant two-way interaction between SES and cognitive load (b = − 1.21, p = .019), and a two-way interaction between ethnicity and cognitive load that approached significance (b = .95, p = .088). These were qualified by a significant three-way interaction between ethnicity, SES, and cognitive load (b = 1.68, p = .032). Figure 3 reveals a similar pattern to the grade outcome, whereby only the higher SES-White British student received a meaningful boost in ratings when the judge was working under high cognitive load. Post-hoc Tukey multiple comparisons of means tests revealed that the difference between low and high cognitive load for this student approached significance (Mdiff = .96 [95% CIs -.04, 1.95], p = .070).

3.2.2.3 Confidence in taking study skills advice

The full model predicting participants’ confidence in taking study skills advice from the target student revealed no main effect of either ethnicity of SES. Those in the high cognitive load condition gave more favourable ratings than those in the low load condition (b = 1.04, p = .003). There were significant two-way interactions between ethnicity and cognitive load (b = − 1.20, p = .019), and between SES and cognitive load (b = 1.04, p = .037). These were, once again, qualified by a significant three-way interaction between ethnicity, SES, and cognitive load (b = 1.49, p = .047). As with the grade and recommendation variables, Fig. 4 shows no significant between-student differences under low-cognitive load, but a favourable boost for the higher SES-White British student under high cognitive load. Once again, Tukey post-hoc multiple comparisons of means revealed this was the only target student to elicit greater confidence in the high (vs low) cognitive load condition, with this effect approaching significance, Mdiff = .94 [95% CIs -.01, 1.89], p = .055. There were no other significant differences.

3.3 Discussion: Study 2

The results of Study 2 demonstrate a nuanced pattern whereby graders’ biases were more pronounced when grading under high cognitive load. Although there were no main effects of SES or ethnicity, and the interaction findings for the three outcomes do not specifically support hypothesis 2, they do align with the prediction that when judges are overworked, they are more likely to rely on heuristics that benefit more historically privileged groups (i.e., White students from more affluent backgrounds).

4 General discussion

Educational outcomes often vary in relation to characteristics that are out of students’ control, and whilst previous research had shown that teachers’ biases may play a role in producing and maintaining such inequalities, little research has experimentally tested the conditions under which SES and ethnicity biases were most likely to emerge. In two pre-registered experiments, we showed that these biases may be more pronounced when graders are cognitively overloaded and when they are judging work of low quality.

Classrooms can often be chaotic—particularly in state schools, where class sizes can exceed 30 children (Department for Education, 2023a). Under such circumstances, the demands of the job often require teachers to attend to a number of things at once, indicating that teachers spend much of their working life under a high degree of cognitive strain (Feldon, 2007; İnan-Kaya & Rubie-Davies, 2022). We found that under such cognitively taxing conditions, biases that favour White students from more affluent backgrounds were more likely to be manifested. The consequences of this are that overworked teachers may inflate the grades of those from more stereotypically high achieving backgrounds more so than they do for those from ethnic minority or low-income backgrounds. This offers a degree of support to the claim of Doyle et al. (2023a) that under normal conditions, teachers may be better able to monitor and inhibit biases that they are mindful of and conscious not to display, but that under high cognitive load, they find such suppression more difficult.

Previous research has offered diverging accounts of whether bias will be more prominent when teachers are presented with stereotype confirming or disconfirming information (Batruch et al., 2017; Bonefeld & Dickhäuser, 2018; Glock & Krolak-Schwerdt, 2013). However, these studies had not investigated the intersectionality between two student characteristics. We explored the roles of student SES and ethnicity at different levels of performance and found that, across all outcome variables, SES bias was more likely to emerge when the quality of work was low. We also found that, when the quality of work was below average, students who were White and affluent were awarded the best grades, suggesting that both SES and ethnicity biases combine in certain situations. In sum, these findings offer support to the theory that biases are more pronounced when judging stereotype-confirming information (e.g., Bonefeld & Dickhäuser, 2018; Glock & Krolak-Schwerdt, 2013)—as would be the case if a student from a typically underperforming group produced a low-quality piece of work. One potential reason that our findings contradict those of Batruch et al. (2017) is that they presented all participants with the same piece of work but led them to believe that the student who had written it was either in a higher or lower school track (indicating higher or lower ability respectively). It is possible therefore that the idea of high-achieving low-SES students may prompt educators to restore the social order by downgrading them, but that when the quality of their work is genuinely excellent, teachers struggle to justify such judgements, thereby attenuating biases. These findings suggest that if students from typically under-achieving groups can manage to produce high quality work, they may free themselves from the barrier of biased judgements. However, schooling is not descriptively meritocratic (Mijs, 2016), with many low-SES and ethnic minority students facing major barriers to progress due to factors such as unequal access to resources (Easterbrook et al., 2023), stereotype threat (Steele et al., 2002), and bias in the education system (Doyle et al., 2023a). Consequently, for many students, the relative absence of bias at high levels of performance may never be experienced.

As discussed, the findings of both studies show—despite there being no significant two-way interactions between ethnicity and SES—indications that under certain circumstances (i.e., low performance or high cognitive load), increases in SES had a more beneficial impact on White compared to Black students. As those from Black backgrounds are more likely to eligible for free school meals and have lower SES than those from White backgrounds (Department for Education, 2023b; Francis-Devine, 2020; Williams et al., 2016), it is possible that in certain contexts, participants perceived Black students to be part of a homogenous group socioeconomically, whereas they were better able to differentiate between White students. We recommend that future research explores this phenomenon in greater detail.

4.1 Implications

These findings add further evidence to a growing body of work showing that teachers’ academic judgements can be influenced by irrelevant information about their students. Overcoming such issues requires time and investment from both individuals and their institutions (Murphy et al., 2018; Stephens et al., 2020). Two brief examples of how schools’ procedures can help attenuate biased judgements are—wherever possible—to use an evaluation rubric (Quinn, 2020), and to ensure that students’ work is anonymous during the assessment process (Malouff et al., 2013). These can help to ensure that judgements are as objective as possible and free from irrelevant influences. The latter, however, is arguably more difficult during the primary phase of schooling as teachers spend all day with their students and may inevitably recognise aspects of their handwriting and style. Nevertheless, given the evidence presented here and elsewhere about biased judgements, we recommend that these techniques be implemented to mitigate inequalities in grading.

The notion that overworked teachers may not perform to the best of their ability is, of course, not novel. Indeed, research has consistently linked heavy workloads with poor mental health (Jomuad et al., 2021; Wu, 2020). However, we show that under such cognitively demanding circumstances, judgements may also exhibit more bias, thereby benefitting some students and punishing others. Whilst it is extremely important for educators to be aware of the links between cognitive overload and bias, it is perhaps of greater importance for school leaders and policy makers to help teachers to reduce their cognitive strain where possible. Similarly, the results of Study 1 suggest that teachers should be aware that their judgements may be more prone to bias when assessing low quality work. As most bias appears to emerge at low levels of performance, an attenuation of bias here could go some way to eliminating the issue of grading bias in education.

Teachers, like many humans, may be reluctant to acknowledge their biases (Doyle et al., 2023b; Solomona et al., 2005), despite being motivated to behave in unbiased ways. Highlighting specific conditions under which teachers may be most vulnerable to bias could be a fruitful way of engaging teachers with the issue rather than simply labelling them as broadly ‘biased’.

Finally, becoming aware of one’s biases is the first step to overcoming them (Devine et al., 2012), yet teacher training often includes very little input on teacher bias (Doyle & Easterbrook, 2023). This frequent omission from teacher training programmes may leave new teachers unaware of how their judgements can unintentionally be influenced by irrelevant information. Initial teacher education centres should endeavour to include findings such as these as a core part of their training programmes to better prepare tomorrow’s teachers to equitably meet the needs of their students.

4.2 Limitations

The sample for Study 2 was comprised of Psychology undergraduate students so we adapted the tasks to be more realistic for this group whilst maintaining a focus on academic judgements. As such, we suggest caution when generalising to teachers in a school context and recommend that future research aims to replicate these findings with a teacher sample. Moreover, there may be different social and power dynamics at play when grading the work of a school student compared to grading the work of a peer. Nevertheless, our findings converge with recent research suggesting that spontaneous interactions in busy classroom environments lead to more bias and a reduction in teachers’ awareness of their differential treatment of students due to a lack of time and space for mindful thinking (İnan-Kaya & Rubie-Davies, 2022), thereby adding to our confidence in our conclusions.

The target students in both studies were male, thereby restricting our ability to generalise teachers’ SES and ethnicity biases to other student genders. Future research should aim to address this by either investigating the contexts for SES and ethnicity biases with a focus on female students, or better still, using larger samples to interact the context with SES, ethnicity, and gender combined.

Finally, we did not specify any specific hypotheses about three-way interactions. Arguably, some of our most intriguing findings related to these interactions, whereby under certain circumstances, high-SES White students were advantaged more so than all others. These findings would carry more weight if they were the result of specific hypotheses, so we recommend that future research builds on our findings to formulate testable pre-registered hypotheses about the varying impact of SES on ethnicity in different contexts.

5 Conclusion

We found that graders’ SES and ethnicity biases were most likely to affect their academic judgements when they are overworked and when they are grading work of low quality. These findings offer educators, school leaders, and policy makers insights into how best to combat the influence of bias as a driver of educational inequality.

Notes

OSF pre-registration link: https://osf.io/mc9eg/?view_only=77a16c94d26d403682ff44eca645c18b. We focus here on hypotheses 1–4.

Year 6 is the final year of primary school in England and is completed by students aged 10–11.

Key Stage 2 SATs are national curriculum tests occurring at the end of year 6 in England. Scaled scores are standardised grades for these tests and range from a minimum of 80 (well below the expected standard) to a maximum of 120 (well above the expected standard). A grade of 100 would indicate that the student has met the expected standard.

As such, the main effects models were specified as: outcome predicted by ethnicity + SES + performance level.

The robust model for the perceived level outcome did not converge, so we used a non-robust linear model for this variable.

As such, the full models were specified as: outcome predicted by ethnicity X SES X performance level, with the output including both two- and three-way interactions.

OSF pre-registration link: https://osf.io/gwtky/?view_only=d9fe0b6fd20e45c796e8316737e90f69.

In the United Kingdom, university grading occurs on a scale of 0–100, and degrees are awarded as classes, from third through lower and upper second to first. A grade of at least 40 is required for a pass and 70 is required for a first-class honours degree (the highest available grade outcome). We coded grades 1 = Fail [< 40], 2 = Low 3rd class [40–44], 3 = High 3rd class [45–49], 4 = Low 2.2 class [50–54], 5 = High 2.2 class [55–59], 6 = Low 2.1 class [60–64], 7 = High 2.1 class [65–69], 8 = Low 1st class [70–74], 9 = High 1st class [75 +].

As such, the main effects models were specified as: outcome predicted by ethnicity + SES + cognitive load.

As such, the full models were specified as: outcome predicted by ethnicity X SES X cognitive load, with the output including both two- and three-way interactions.

References

Anders, J. Macmillan, L., Sturgis, P., Wyness, G. (2021). The ‘graduate parent’ advantage in teacher assessed grades. Retreived August 11, 2021, from https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/cepeo/2021/06/08/thegraduate-parentadvantageinteacherassessedgrades/#:~:text=Morethanathirdof,gradesinitiallyassessedbyteachers

Anderson-Clark, T. N., Green, R. J., & Henley, T. B. (2008). The relationship between first names and teacher expectations for achievement motivation. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 27(1), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X07309514

Batruch, A., Autin, F., Bataillard, F., & Butera, F. (2019). School selection and the social class divide: How tracking contributes to the reproduction of inequalities. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(3), 477–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218791804

Batruch, A., Autin, F., & Butera, F. (2017). Re-establishing the social-class order: Restorative reactions against high-achieving low-SES pupils. Journal of Social Issues, 73, 42. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12203

Batruch, A., Geven, S., Kessenich, E., & van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2023). Are tracking recommendations biased? A review of teachers’ role in the creation of inequalities in tracking decisions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 123, 103985.

Blair, I. V., & Banaji, M. R. (1996). Automatic and controlled processes in stereotype priming. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(6), 1142.

Bodenhausen, G. V. (1990). Stereotypes as judgmental heuristics: Evidence of circadian variations in discrimination. Psychological Science, 1(5), 319–322.

Bonefeld, M., & Dickhäuser, O. (2018). (Biased) Grading of students’ performance: Students’ names, performance level, and implicit attitudes. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 481. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00481

Burgess, D. J. (2010). Are providers more likely to contribute to healthcare disparities under high levels of cognitive load? How features of the healthcare setting may lead to biases in medical decision making. Medical Decision Making, 30(2), 246–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X09341751

Burgess, S., & Greaves, E. (2013). test scores, subjective assessment, and stereotyping of ethnic minorities. Journal of Labor Economics, 31(3), 535–576. https://doi.org/10.1086/669340

Campbell, T. (2015). Stereotyped at seven? Biases in teacher judgement of pupils’ ability and attainment. Journal of Social Policy, 44(3), 517–547. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279415000227

Connolly, P., Taylor, B., Francis, B., Archer, L., Hodgen, J., Mazenod, A., & Tereshchenko, A. (2019). The misallocation of students to academic sets in maths: A study of secondary schools in England. British Educational Research Journal, 45(4), 873–897. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3530

Danziger, S., Levav, J., & Avnaim-Pesso, L. (2011). Extraneous factors in judicial decisions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(17), 6889–6892. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1018033108

Department for Education (2022). GCSE English and maths results. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/education-skills-and-training/11-to-16-years-old/a-to-c-in-english-and-maths-gcse-attainment-for-children-aged-14-to-16-key-stage-4/latest#by-ethnicity

Department for Education (2023a). Schools, pupils and their characteristics: Class size. Retrieved May 23, 2023, from https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-pupils-and-their-characteristics

Department for Education (2023b). Schools, pupils and their characteristics: Free school meals eligibility. Retrieved September 11, 2023, from https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-pupils-and-their-characteristics..

Devine, P. G., Forscher, P. S., Austin, A. J., & Cox, W. T. L. (2012). Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(6), 1267–1278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.06.003

Doyle, L., & Easterbrook, M. J. (2023). Biased career choices? It depends what you believe: Trainee teachers' aversions to working in low-income schools are moderated by beliefs about inequality, meritocracy, and growth mindsets. Preprint retrieved from PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/w3pzh

Doyle, L., Easterbrook, M. J., & Harris, P. R. (2023a). Roles of socioeconomic status, ethnicity and teacher beliefs in academic grading. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12541

Doyle, L., Easterbrook, M. J., & Harris, P. R. (2023b). It’s a problem, but not mine: Exploring bias-related message acceptance among teachers. Social Psychology of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09832-9

Dunne, M., & Gazeley, L. (2008). Teachers, social class and underachievement. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29(5), 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690802263627

Easterbrook, M. J., Doyle, L., Grozev, V. H., Kosakowska-Berezecka, N., Harris, P. R., & Phalet, K. (2023). Socioeconomic and gender inequalities in home learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Examining the roles of the home environment, parent supervision, and educational provisions. Educational and Developmental Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1080/20590776.2021.2014281

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Feldon, D. F. (2007). Cognitive load and classroom teaching: The double-edged sword of automaticity. Educational Psychologist, 42(3), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520701416173

Francis-Devine, B. (2020). Which ethnic groups are most affected by income inequality?. Commons Library, 10(August).

Gillborn, D., Rollock, N., Vincent, C., & Ball, S. J. (2012). ‘You got a pass, so what more do you want?’: Race, class and gender intersections in the educational experiences of the Black middle class. Race Ethnicity and Education, 15(1), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2012.638869

Gilliam, W. S., Maupin, A. N., Reyes, C. R., Accavitti, M., & Shic, F. (2016). Do early educators’ implicit biases regarding sex and race relate to behavior expectations and recommendations of preschool expulsions and suspensions. Yale University Child Study Center, 9(28), 1–16.

Glock, S., & Kleen, H. (2020). Preservice teachers’ attitudes, attributions, and stereotypes: Exploring the disadvantages of students from families with low socioeconomic status. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 67, 100929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100929

Glock, S., & Krolak-Schwerdt, S. (2013). Does nationality matter? The impact of stereotypical expectations on student teachers’ judgments. Social Psychology of Education, 16(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-012-9197-z

Glock, S., Krolak-Schwerdt, S., & Pit-ten Cate, I. M. (2015). Are school placement recommendations accurate? The effect of students’ ethnicity on teachers’ judgments and recognition memory. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 30(2), 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-014-0237-2

Goudeau, S., Sanrey, C., Autin, F., Stephens, N. M., Markus, H. R., Croizet, J.-C., & Cimpian, A. (2023). Unequal opportunities from the start: Socioeconomic disparities in classroom participation in preschool. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 152(11), 3135–3152. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001437

Hao, H., & Conway, A. R. A. (2022). The impact of auditory distraction on reading comprehension: An individual differences investigation. Memory & Cognition, 50(4), 852–863. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-021-01242-6

Hutchinson, J., Reader, M., & Akhal, A. (2020). Education in England: annual report 2020. https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/education-in-england-annual-report-2020/

İnan-Kaya, G., & Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2022). Teacher classroom interactions and behaviours: Indications of bias. Learning and Instruction, 78, 101516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2021.101516

Iyer, A., Leach, C. W., & Crosby, F. J. (2003). White guilt and racial compensation: The benefits and limits of self-focus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(1), 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202238377

Jacoby-Senghor, D. S., Sinclair, S., & Shelton, J. N. (2016). A lesson in bias: The relationship between implicit racial bias and performance in pedagogical contexts. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 63, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.10.010

Jarvis, S. N., & Okonofua, J. A. (2020). School deferred: When bias affects school leaders. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(4), 492–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619875150

Jomuad, P. D., Antiquina, L. M. M., Cericos, E. U., Bacus, J. A., Vallejo, J. H., Dionio, B. B., & Clarin, A. S. (2021). Teachers’ workload in relation to burnout and work performance. International Journal of Educational Policy Research and Review, 8(2), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.15739/IJEPRR.21.007

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

Lievore, I., & Triventi, M. (2023). Do teacher and classroom characteristics affect the way in which girls and boys are graded?: A multilevel analysis of student–teacher matched data. British Journal of Sociology of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2022.2122942

Malouff, J. M., Emmerton, A. J., & Schutte, N. S. (2013). The risk of a halo bias as a reason to keep students anonymous during grading. Teaching of Psychology, 40(3), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628313487425

Marken, S., & Agrawal, S. (2022). K-12 Workers have highest burnout rate in U.S. Retrieved May 23, 2023, from https://news.gallup.com/poll/393500/workers-highest-burnout-rate.aspx

Mijs, J. J. B. (2016). The unfulfillable promise of meritocracy: Three lessons and their implications for justice in education. Social Justice Research, 29(1), 14–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-014-0228-0

Murphy, M. C., Kroeper, K. M., & Ozier, E. M. (2018). Prejudiced places: How contexts shape inequality and how policy can change them. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 5(1), 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732217748671

Okonofua, J. A., & Eberhardt, J. L. (2015). Two strikes: Race and the disciplining of young students. Psychological Science, 26(5), 617–624.

Pit-ten Cate, I. M., & Glock, S. (2018). Teachers’ attitudes towards students with high-and low-educated parents. Social Psychology of Education, 21(3), 725–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-9436-z

Plant, E. A., & Devine, P. G. (1998). Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 811. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.811

Quinn, D. M. (2020). Experimental evidence on teachers’ racial bias in student evaluation: The role of grading scales. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(3), 375–392. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373720932188

Reynolds, W. M. (1982). Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38(1), 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(198201)38:13.0.CO;2-I

Singh, B., Axt, J., Hudson, S. M., Mellinger, C. L., Wittenbrink, B., & Correll, J. (2020). When practice fails to reduce racial bias in the decision to shoot: The case of cognitive load. Social Cognition, 38(6), 555–570. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2020.38.6.555

Solomona, R. P., Portelli, J. P., Daniel, B., & Campbell, A. (2005). The discourse of denial: How white teacher candidates construct race, racism and ‘white privilege.’ Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(2), 147–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613320500110519

Sommet, N., Weissman, D. L., Cheutin, N., & Elliot, A. J. (2023). How many participants do I need to test an interaction? Conducting an appropriate power analysis and achieving sufficient power to detect an interaction. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 6(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/25152459231178728

Standards and Testing Agency (2019). Key stage 2 English writing standardisation exercise 1. Retrieved October 14, 2021, from http://www.lancsngfl.ac.uk/curriculum/assessment/index.php?category_id=751&s=!B121cf29d70ec8a3d54a33343010cc2

Starck, J. G., Riddle, T., Sinclair, S., & Warikoo, N. (2020). Teachers are people too: Examining the racial bias of teachers compared to other American adults. Educational Researcher, 49(4), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20912758

Steele, C. M., Spencer, S. J., & Aronson, J. (2002). Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 34, pp. 379–440). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(02)80009-0

Stephens, N. M., Rivera, L. A., & Townsend, S. S. (2020). What works to reduce bias? A multilevel approach. Unpublished manuscript. https://www.nicolemstephens.com/uploads/3/9/5/9/39596235/stephensriveratownsend_rob_12,8

Strand, S. (2012). The White British-Black Caribbean achievement gap: Tests, tiers and teacher expectations. British Educational Research Journal, 38(1), 75–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2010.526702

Tenenbaum, H. R., & Ruck, M. D. (2007). Are teachers’ expectations different for racial minority than for European American students? A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(2), 253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.253

Wang, J., Zamar, R., Marazzi, A., Yohai, V., Salibian-Barrera, M., Maronna, R., ... & Konis, M. K. (2022). Package ‘robust’. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/robust/robust.pdf

Watt, H. M. G., & Richardson, P. W. (2007). Motivational factors influencing teaching as a career choice: Development and validation of the FIT-choice scale. The Journal of Experimental Education, 75(3), 167–202. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.75.3.167-202

Williams, D. R., Priest, N., & Anderson, N. B. (2016). Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: Patterns and prospects. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 35(4), 407–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000242

Wu, D. (2020). Relationship between job burnout and mental health of teachers under work stress. Revista Argentina De Clínica Psicológica, 29(1), 310. https://doi.org/10.24205/03276716.2020.41

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the University of Sussex School of Psychology Research Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LD was responsible for conceptualization; investigation; writing—original draft; methodology; visualization; writing—review & editing; Formal analysis; project administration; resources; data curation. PRH was responsible for writing—review & editing; supervision. MJE was responsible for conceptualization; writing—review & editing; supervision; methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that there was no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Doyle, L., Harris, P.R. & Easterbrook, M.J. Quality and quantity: How contexts influence the emergence of teacher bias. Soc Psychol Educ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09882-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09882-z