Abstract

The importance of having highly motivated teaching staffs is widely recognised and most teaching institutions implement various policies and incentives designed to stimulate their teachers’ motivation. It is equally important to recognise forces which have the potential to demotivate teachers. Among these forces, previous research has shown student-related factors to be the most detrimental to teacher motivation. Our aims were to examine Vietnamese university English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers’ perceptions of student-related demotivating factors, and the ways these factors influence teachers and their teaching. Using semi-structured interviews, data were collected from 30 participating EFL teachers from 14 universities in Vietnam. The results of the study revealed that students’ limited English proficiency, negative attitudes towards English and English language learning, poor classroom performance, and low academic achievement as the most potent student-related demotivating factors for Vietnamese EFL teachers; these factors were found to have a range of negative consequences for teachers’ emotions, behaviours, and attitudes. The relative impact of these factors on participating teachers was subject to individual variation. Practical implications and limitations of the study are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Second language (L2) acquisition researchers have always seen motivation as the most powerful determinant of learners’ performance and learning outcomes (Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2011). The last six decades have witnessed a huge growth in L2 learner motivation research (Ames, 1984; Dörnyei, 1990; Gardner, 1985; Guilloteaux & Dönyei, 2008; MacIntyre et al., 2009; Noels et al., 2001). More recently, there has been a growing interest in issues of L2 teacher motivation, with research showing that teacher motivation has a significant impact on L2 learners’ success, teachers’ performance and well-being, and national education reforms (Dörnyei & Csizér, 1998; Han & Yin, 2016; Jesus & Lens, 2005; Kim et al., 2014; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2010). Reeve (2009) found that autonomous motivated teachers tended to provide students with autonomy-supportive teaching methods, which facilitated students’ need satisfaction and personal accomplishment. According to this study, students instructed by intrinsically motivated teachers show a relatively high level of motivation and interest in L2 learning (Wild et al., 1997). Also, teachers who report a high level of motivation for teaching are less likely to suffer from job stress and burnout (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2010). Teaching is regarded as a challenging profession with a variety of duties and responsibilities (Reeve & Su, 2014), however, an intrinsically motivated teacher always enjoys his/her teaching as well as the development of students under no circumstances (Dinham & Scott, 1998). Roth (2014) suggests that highly motivated teachers not only show a high level of confidence and commitment to the profession but also effectively deal with obstacles and difficulties in teaching.

High teacher motivation can be uplifting, but low teacher motivation can be thwarting and destructive (Dinham & Scott, 2000; Sugino, 2010a, b). A low level of motivation in teachers can impair their performance and the development of students (Kim et al., 2014). Atkinson (2000) examined the relationships between teacher motivation and student motivation and found that demotivated teachers reported a lower level of self-efficacy and passion for teaching than motivated teachers. So far, however, very little attention has been paid to teacher demotivation in L2 learning and teaching. To address this gap, the study reported here aimed to examine teachers’ experiences and perceptions when students show negative attitudes, a low interest and effort in English language learning, and misbehave in class. Among other things, the study explored the ways in which these factors influenced teachers’ emotions, attitudes, and teaching behaviours.

2 Literature review

2.1 Teacher demotivation

Demotivation can be understood as the reduction of an individual’s effort and motivation for an action or a particular goal (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2011). Falout et al. (2009, p. 404) consider demotivation as a process “starting from an external locus, a demotivating trigger, before it becomes an internalisation”. Thus, a motivated state must exist before the demotivation process happens. In the field of education, a demotivated teacher is described as “a person who was once motivated but has lost it due to some specific causes in the teaching environment” (Kiziltepe, 2008, p. 520).

Acknowledging that external conditions play a key role in triggering a demotivating experience in teachers, previous work has focused on identifying these demotivators (Dörnyei, 2001; Hettiarachchi, 2013; Kim et al., 2014; Kiziltepe, 2008; Pourtoussi et al., 2018; Sugino, 2010a, b; Yadin, 2012; Yaghoubinejad et al., 2017). The common causes of teacher demotivation include problems related to students, problems related to teaching and curriculum, poor working conditions, job satisfaction and incentives, relationships with colleagues and administrators, and opportunities for teachers’ professional development.

Unlike previous researchers, Pourtoussi et al. (2018) used four different sources of data collection, such as interviews, diaries, journal, and open-ended questions to study the determinants and consequences of Iranian EFL teacher demotivation. The authors categorised the antecedents of teacher demotivation into two main themes: immediate setting (facilities and physical setting), and job-related setting (non-human-related and human-related). The consequences of teachers’ motivation were classified in three main categories: physical (energy), behavioural (engagement, problem solving, commitment, creativity, and rapport), and attitudinal (cynicism, anxiety, satisfaction, burnout, students’ motivation, and self-esteem). Notably, student-related factors were reported as the most demotivating among Iranian EFL teachers.

Studies on sources of teacher demotivation have shown that students’ behaviours and attitudes had a major impact on teacher motivation, job satisfaction and professional commitment (Dinham & Scott, 2000; Hettiarachchi, 2013; Kitching et al., 2009; Kiziltepe, 2008; Pennington, 1995; Pourtoussi et al., 2018; Sugino, 2010a, b). Student-related factors contributing to teacher demotivation include lack of motivation and interest in English language learning, negative attitudes towards English, English language learning, and English teachers, limited proficiency in English, lack of respect to English teachers, disruptive behaviours in class, and cultural differences between teachers and students (Hettiarachchi, 2013; Kiziltepe, 2008; Pourtoussi et al., 2018; Sugino, 2010a, b).

2.2 English language teaching in the Vietnamese higher education context

Teaching EFL at the Vietnamese tertiary level occurs in two main categories: English major programs and non-English major programs. English major programs are for students who desire to become teachers of English, interpreters, and translators (Hoang, 2010). Courses taught in the English major programs include language foundations, linguistics, English literature, translation, interpretation, and English language teaching methodology. On the other hand, non-English major students study English as a compulsory subject in their bachelor’s degree programs. English for non-English majors includes General English (GE) and English for Specific Purposes (ESP) courses. GE courses are designed to develop students’ four basic communicative skills (Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing) and English grammar rules. The ESP courses are designed to foster students’ specific knowledge and vocabulary related to their primary major (Pham & Bui, 2019; Trinh & Mai, 2019), for example, English for Economics, English for Finance, English for Tourism, English for Information Technology, etc.

Vietnamese language teachers not only impart English language knowledge to students and assist students in developing their language proficiency, but they also act in the role of ‘moral guides’ (Phan, 2008). With this unique role, teachers are expected to behave morally, demonstrate their willingness to care more for students’ language proficiency and moral development, and maintain a good relationship with students (Le & Dwyer, 2019). Teachers therefore have a high status in the Vietnamese society and receive respect as well as care from students, parents, and the broader society (Phan, 2008). Vietnamese students are expected to show their respect and gratitude to teachers by all cost (Pham, 2011). Students’ misbehaviour, rudeness, and disrespect are not acceptable in Vietnam (Nguyen & Hall, 2017). Respect and gratitude for teachers are demonstrated in various Vietnamese proverbs and quotations (Breach, 2004; Phan, 2008). For example:

You will not succeed without teachers

(Không thầy đố mày làm nên)

Respect teachers, respect morality

(Tôn sư trọng đạo)

Recent developments in teacher demotivation have heightened the need for identifying potential factors that might diminish teacher motivation and job satisfaction (Dörnyei, 2001; Hettiarachchi, 2013; Kim et al., 2014; Kiziltepe, 2008; Pourtoussi et al., 2018; Sugino, 2010a, b; Yadin, 2012; Yaghoubinejad et al., 2017). However, little is known about teacher demotivation and the demotivational process in developing countries in general in the Vietnamese higher education context in particular. With the role of ‘moral guides’ (Phan, 2008), it can be supposed that Vietnamese teachers might be less affected by student-related demotivating factors and demonstrate a high level of tolerance towards these factors. To explore this, the current study therefore set out to answer the following research questions:

-

(1)

How do Vietnamese university EFL teachers make sense of student-related demotivating factors?

-

(2)

How do Vietnamese university EFL teachers respond to student-related demotivating factors?

3 Method

3.1 Participants

The participants of the current study were 30 EFL teachers (76.67% female, 23.33% male) from 14 universities across Vietnam, with a varying length of English language teaching experience ranging from 2 to 37 years. Nearly half of the interview participants (43.33%) had been teaching English for 11 to 20 years. More than a third of them (36.67%) had 5 to 10 years of English language teaching experience. Four participants (13.33%) were experienced teachers who had working for more than 21 years. Only two participants (6.67%) were novice teachers with under 5 years of English language teaching experience. The number of teachers from metropolitan areas were slightly higher than those from provincial areas (56.67% and 43.33% respectively). More than half of the participants (53.33%) were teaching English at private universities. The percentage of those working for public universities was 46.67%.

3.2 Instruments

The current study employed semi-structured interviews to investigate teachers’ experiences and perceptions of student-related demotivating factors, and the influences of these factors on teachers’ feelings and teaching performance. Data were collected between November and December 2018. First, the participants were asked to recall a specific situation when students did something that made them feel bad about teaching, and to describe in detail their feelings and reactions. Participants were also asked to assess the impact of their student-related demotivating experiences and to describe the effects that these experiences had on their teaching practices.

3.3 Data collection and analysis

The current study employed convenience sampling. After obtaining the permission from the participating universities, the first author emailed 104 EFL teachers who employed in these universities to invite them to participate in the study. Thirty teachers agreed to participate in the study. Teachers who were interested were contacted via emails to schedule the convenient interview times. The interviews took place in meeting/seminar rooms of the institutions where the participants were working. Privacy and safety measures were put in place to ensure that participants felt confident and comfortable during the interviews. Interviews were conducted in Vietnamese – the mother tongue of participants.

At the beginning of the interviews, the aims of the interviews, how the data would be used, the confidentiality of participants and their responses, and the estimated length of the interviews were explained clearly to the participants. They were all informed that the interviews would be audio-recorded and asked if they were happy to be audio-recorded. In addition, participants could withdraw from the interviews anytime that they wished. When participants confirmed that they clearly understood the interview procedure and agreed to participate, they were requested to sign a consent form.

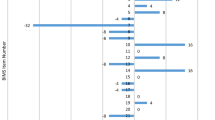

To preserve individual participants’ anonymity, their names were removed, and their data were coded (e.g., Teacher No.5; Teacher No.17). The qualitative data analysis procedure was drawn from the six-phase thematic analysis proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006). Data collected were transcribed into a Microsoft Word file and translated into English before being imported to NVivo 12 software. The data analysis procedure started with initial code generation and followed up with the emergence of themes and sub-themes. Themes and sub-themes generated were systematically revised and modified. Appendix A provided an example of how interview transcript was coded and how a sub-theme was defined. Findings emerged from themes and sub-themes were presented in reference to the research questions (see Fig. 1). Verbatim quotations were included to provide explanations and illustrations of categories and themes emerging from the analysis.

4 Findings

The findings from the data analysis are organised into two sections aligned with two research questions. The first section focuses on teachers’ perceptions of student-related demotivating factors which includes two main themes, teachers with negative perceptions of student-related demotivating factors, and teachers with optimistic perceptions of student-related demotivating factors. The second section is about teachers’ responses to student-related demotivating factors with three main themes, including: emotional responses, attitudinal responses towards EFL teaching, and behavioural responses. Figure 1 provides details of final main themes and sub-themes of the current study.

4.1 Teachers’ perceptions of student-related demotivating factors

4.1.1 Teachers with negative perceptions of student-related demotivating factors

The majority of teachers (n = 23) reported being affected by students’ negative attitudes, poor classroom performance, disruptive behaviours in the classroom, as well as perceived lack of respect for teachers.

4.1.1.1 Students’ lack of respect for effort teacher

Teachers in the current study agreed that teaching is a dedicating profession. Teachers recognised the considerable demands that their profession places on them and were prepared to invest substantial efforts into preparing their lessons and deploying effective teaching techniques. Teacher No.4 shared that she made a great attempt to prepare good lessons everyday by spending hours looking for updated materials and new teaching techniques for her lessons. Talking about teachers’ dedication, Teacher No.9 stressed that she entered the teaching profession because of her intrinsic motivation to help others and she sacrificed her own financial wellness to the profession.

When teachers put a lot of effort into their lesson plans and teaching practices, they tended to give all their attention to students and expected that students would enjoy the lessons and appreciate their efforts. Teacher No.11 stated, “Hard work should pay off. I work hard for them [students], I should get results”. This quote indicated that Teacher No.11 hold a strong belief that if she put energy and effort into teaching, she would achieve her desired outcomes.

The outcomes of teachers’ hard work could be assessed by the extent to which students engage in the lessons and their attitudes towards the learning process. Teacher No.25 stated, “I expected they would follow my instruction and advice, but they did not”. Consequently, students’ failure to perform according to teachers’ expectations might cause teachers’ perceptions that students did not recognise and respect their efforts and dedication. Teacher No.30 shared her thoughts of students’ misbehaviour in classroom,

Excerpt 1:

Seeing students’ negative attitudes and rudeness in class, I find they don’t respect what I have done for them. They never know how hard I work to prepare lessons to teach them.

4.1.1.2 Students’ lack of respect for knowledge teachers

Teachers revealed that students’ misbehaviour, low levels of engagement and motivation for English language learning was also a sign of their lack of respect for the English language knowledge. Teacher No.11 related, “They [Students] don’t need knowledge. My teaching doesn’t matter to them”. This quote suggests that teachers might have an assumption that every student came to class because they wanted to improve their English language comprehension. Therefore, they would involve in the lesson to achieve the learning outcomes. However, when students showed lack of interest and focus on the learning activities, teachers tended to interpret/ clarify/ understand/ perceive/ conclude/ assess that students were not active and engaged because the knowledge was not important to them.

4.1.2 Teachers with optimistic perceptions of student-related demotivating factors

However, not all of the participating teachers were as adversely affected by students-related factors. Some of them (n = 7) took a more optimistic stance. For example, teachers could show their understanding and tolerance to students’ poor performance and misbehaviour.

4.1.2.1 Showing understanding of students’ poor performance and misbehaviour

Three teachers shared the view that “Students” poor performance and misbehaviours are common (Teachers No.2, No.29 and No.20). According to Teacher No.2, “they are students, young and immature”, which makes their lack of discipline understandable. Teacher No.25, the most experienced teacher in the sample, with over 37 years of ELT experience, expressed the belief that students’ disinterest and disengagement in class were due to teachers’ incompetence. According to her, teachers should take charge of students’ interest and engagement in English language learning rather than expecting that students were already highly motivated and excited about learning when they came to class. As this teacher said, “Students’ passivity and misbehaviours are not students’ faults. They’re teachers’ faults. Because teachers haven’t done well enough to inspire students”.

4.1.2.2 Showing tolerance to students’ poor performance and misbehaviour

Apart from the understanding of students’ poor performance and misbehaviour, these teachers also showed greater tolerance to their students. Teacher No.13, a senior teacher at a public regional university, showed understanding and considerable sympathy towards her students’ difficulties. She said, “I can’t blame them for their weakness. They come from rural mountainous areas, and they suffer from many disadvantages in learning. Obviously, their English competence is not as good as metropolitan students”.

Besides, teachers noted that students’ lack of interest and engagement in the lesson could be a result of the mismatch between students’ personal needs and the learning topics, or their daily emotions. Therefore, Teacher No.23, who had been teaching English for more than 18 years, suggested that it was crucial for teachers to be aware and understand how students felt and what they expected from learning the English language to find appropriate motivational strategies.

Teacher No.9 took a distinctively motherly approach to her students and treated their disruptive behaviours with the same tolerance and patience as she would do with her own children. She said, “Because I’m a mother, I understand that kids are naughty. I don’t resent their impolite words and behaviours. I can stand my children, so I can stand my student”.

Teachers’ tolerance and patience with their students was found to link to their sense of being a ‘moral guide’. Teacher No.2 clarified that students not only needed someone to provide them with academic knowledge, but they also need a life mentor who could teach them soft skills and social knowledge to become good citizens. For this reason, teachers should try their best and be tolerate to students’ immaturity and misbehaviour to assist students’ both knowledge and moral development.

4.2 Teachers’ responses to student-related demotivating factors

4.2.1 Emotional responses

4.2.1.1 Negative emotions

All teachers in this study (n = 30) reported that students’ negative learning attitudes, passive performance, poor academic achievement and disrespectful behaviours caused them to experience a variety of negative emotions, such as feeling discouraged, stressed, doubtful, offended, disappointed, upset, hopeless, exhausted, and irritated. Some of the statements teachers made during the interview clearly illustrate the deep emotional impact that student-related demotivating factors had on them, e.g. “I am really upset when many students are absent from my lesson” (Teacher No.6); “It so boring when teaching silent students” (Teacher No.26); “I feel hurt when my students do not cooperate with me during the lesson” (Teacher No.22). Teacher No.7, who had more than 22 years of ELT experience talked about her depression when confronting and dealing with students’ lack of interest in English language learning,

Excerpt 2:

Students’ negative attitudes and poor performance in class hurt me terribly. I can see that my students don’t like me. I can’t believe that they behave in this way.

4.2.1.2 Perceived ineffectiveness in classroom management

Teaching passive students created more challenges and difficulties for teachers. Teacher No.29, with over 8 years of English teaching experience at a metropolitan public university, confessed that her students’ shyness and passivity during the lesson somehow made her feel angry and hopeless of teaching even though she understood that students’ learning anxiety may be the underlying cause for their learning behaviours,

Excerpt 3:

I taught a class in which students were extremely passive. I understood that they were shy and kept silent because of their low English proficiency. When I raised questions, no one answered me. Even when I called on them to answer my questions, they spoke at a low volume. It made me feel annoyed. I wanted them to overcome their anxiety and speak up in my class. But they didn’t listen to me. They still kept silent. I surrendered.

4.2.2 Attitudinal responses to student-related demotivating factors

4.2.2.1 Negative attitudes

More than two thirds of the participating teachers (n = 23) reported negative attitudes towards English language teaching as a result of student demotivating factors. These factors not only diminished their enjoyment of teaching, but also generated in them negative perceptions of their own teaching, such as “teaching as a heavy burden” (Teacher No.15) or “teaching as an obligation” (Teacher No.22).

Excerpt 4:

Teaching those who keep silent all the time in class is incredibly stressful. I only wish the lesson would end as quickly as possible. It’s quite strange that I talk less during the lesson in comparison to teaching active students. But teaching passive students makes me exhausted. (Teacher No.20)

Teaching students with limited English proficiency was often demoralising. A senior teacher from a provincial university said, “Teaching low English proficiency students is challenging and time-consuming, and it’s not effective” (Teacher No.13). Some teachers spoke very negatively about their students’ competence in English. For example, “My students’ English is too weak (Teacher No.3); “Their English proficiency is so low that they are unable to understand the lesson” (Teacher No.5); “You can’t image how terrible their English is. I don’t know how they could pass the entrance examinations” (Teacher No.24); and “My students are not clever, they sometimes cannot acquire the content knowledge” (Teacher No.14). These teachers said that students’ limited English competence resulted in students’ unfavourable learning attitudes and passive behaviour in class. Consequently, teaching became more challenging and difficult. Teacher No.5 related, “When students’ English proficiency is so low they are unable to keep up with the lesson. Sooner or later they will be afraid of learning and become passive”.

Teachers also indicated that dealing with students’ misbehaviours not only influenced their current feelings in class, but it also had a long-lasting effect on their motivation and attitudes afterwards,

Excerpt 5:

It’s not just one lesson, they [students’ misbehaviours] also affect me the next lessons. Whenever I think of students’ deteriorating behaviours, I feel discouraged and want to give up teaching immediately. Teaching disruptive students wears me out. (Teacher No.15)

4.2.2.2 Positive attitudes

Not all teachers’ attitudes were as susceptible to student-related demotivating factors as the ones quoted above. Seven of the teachers admitted that students’ low level of effort and interest in English language learning, and/or disruptive behaviours did make an impact on their emotions. However, this did not necessarily lead to a shift in their attitudes and/or motivation for teaching.

Excerpt 6:

We shouldn’t pay too much attention to students’ misbehaviours in class. Definitely, my emotions are strongly influenced by my students’ reactions and utterance in class. However, I do not hate my students or my job just because of these components. We shouldn’t keep these bad things in our mind for hours. (Teacher No.19)

These teachers had a strong sense of self-efficacy and were confident that they could improve their students’ performance, as Teacher No.25 noted,

Excerpt 7:

Teachers should be patient with students. Initially, students don’t show their interest in English language learning. It’s very common. However, by being inspired and taught by highly motivated teachers, students will gradually enjoy English language learning.

4.2.3 Behavioural responses to student-related demotivating factors

4.2.3.1 Teachers whose teaching behaviours were negatively affected by student-related demotivating factors

Teachers who reported developing negative attitudes towards teaching due to student demotivating factors (n = 23) stated that when they found their effort and dedication was not appreciated by students, they tended to put little effort into teaching. For instance, here is how a teacher from a private metropolitan university described her experiences when dealing with students’ low level of interest in English language learning,

Excerpt 8:

Normally, I often provide my students with knowledge that is not covered in textbooks. But when I don’t feel enthusiastic and motivated for teaching, I don’t want to do it [provide expanded knowledge] anymore. (Teacher No.22)

Teachers also admitted that they did not put much energy into their preparation when students did not actively engage in the lesson and did not appreciate their effort and dedication. Teacher No.11 expressed the view that students’ poor performance and misbehaviours were unchangeable, therefore her continuous effort and investment in teaching would be a waste of time,

Excerpt 9:

I stopped investing time and effort in preparing classroom activities. Suppose I kept preparing, but they [students] still wouldn’t participate in the lessons. There would be no point in wasting my time and effort for those who undervalued me.

Notably, teachers’ experiences of incompetence and hopelessness caused by student demotivating factors led to a decline in teachers’ commitment and devotion to their teaching. To avoid the feeling of ineffectiveness, teachers tended to complete their teaching by presenting all content knowledge to students with little or no concern about how much of it the students actually took in. Teacher No.8, whose EFL experience was more than 20 years, said,

Excerpt 10:

I choose to get the lesson over. Teaching is my job; therefore, I must prepare the lessons, and follow the requirements and regulations of the university. When students do not pay attention to the lessons or do something in private, it’s their business not mine. I will focus on completing my task that is lecturing all content knowledge in the lessons. Obviously, I do not feel my passion and motivation in teaching any more.

4.2.3.2 Teachers whose teaching behaviours were negatively affected by student-related demotivating factors

As mentioned previously, not all the participating teachers reacted negatively to student demotivating factors. The same group of seven teachers whose attitudes were less affected by these factors reported that they were not prepared to neglect or give up on students who were disengaged or disruptive in class. These teachers believed that they were able to “change students’ behaviours” (Teachers No.2 and No.19) and “engage them in the lesson” (Teacher No.25). Notably, instead of giving up, they increased their preparation effort and sought to deploy strategies will help improve students’ attitudes and behaviours class. For example, Teachers No.2 and No.23 investigated “the reasons for students’ lack of interest and focus on lesson”, Teacher No.19 modified “the lesson plans and teaching methods to match students’ learning styles”, while Teacher No.13 provided “students with free tutorials after school”.

Excerpt 11:

Initially, I start my lesson slowly. After students get used to my teaching style, I make every attempt to get them involved in the classroom activities to rouse their interest. After every lesson, I reflect on students’ reactions in the class, their attitudes towards the classroom activities, and their difficulties and troubles in learning. I take notes of these things and then I modify my lesson plans to meet my students’ need. (Teacher No.2)

5 Discussion

The case study reported here examined teachers’ perceptions of student-related demotivating factors and the impact of these factors on EFL teachers and their teaching in the Vietnamese higher education context. Data were collected via a semi-structured interview which were then analysed to gain insights into issues of teacher demotivation at Vietnamese universities.

Consistent with the literature, this study confirms the power of student-related factors to affect teachers and their teaching performance (Hettiarachchi, 2013; Kim et al., 2014; Kiziltepe, 2008; Pourtoussi et al., 2018; Sugino, 2010a, b). Students’ limited English proficiency, negative attitudes towards English and English language learning, poor classroom behaviour, and low academic achievement emerged as significant demotivating forces for the participating teachers.

All teachers in the current study experienced a range of disagreeable emotions. They reported feeling angry, upset, hopeless, disappointed and irritated when facing poor attitudes, lack of interest/engagement and/or disruptive behaviour on the part of their students. According to Sutton (2005), teachers’ negative emotions tend to emerge when their professional goals and aspirations are thwarted. Students’ misbehaviours unavoidably make teaching more difficult and diminish teachers’ capacity to accomplish their teaching goals. This in turn affects teachers’ sense of competence (Ryan & Deci, 2017) and can make them feel like they have lost control of their teaching.

Teaching is a highly respected profession in the Vietnamese society and students are expected to show unreserved and unconditional respect to their teachers at all times (Nguyen, 2019; Phan, 2008). Respectful behaviour includes (but is not limited to) attending class on time, being focused and engaged in class, listening to the teacher’s instruction, following the teacher’s directions, and completing their homework before coming to class. There is an expectation among Vietnamese teachers that students will show their respect and appreciation of teachers’ hard work by actively participating in the lessons (Nguyen Thi Mai & Hall, 2017). When students fail to show a suitable level of interest and engagement in learning, teachers perceive this is an act of disregard and disrespect, and consequently feel disappointed and undervalued.

Teachers adversely affected by student misbehaviour can develop negative attitudes towards English language teaching. For them, the enjoyment and meaning of teaching gets eroded and is replaced by the anxiety and pessimism. Troubles and challenges caused by students can affect teachers’ sense of agency and competence, and can reduce their ability to bring “about desired outcomes of student engagement and learning” (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001, p. 783). Most importantly, students’ challenging behaviours can have long-lasting effects on teachers’ job satisfaction and work enthusiasm (Hagenauer et al., 2015). The same situation emerged in the current study. Teachers whose attitudes towards teaching were negatively affected by student-related factors acknowledged a deterioration in their teaching effort, creativity and commitment. These teachers reported having low energy, coming to class with little or no preparation, and feeling increasingly indifferent to their students (Pourtoussi et al., 2018). They perceived adverse student attitudes and behaviours as barriers to effective teaching and often limited their instruction to mere delivery of content knowledge, with little or no attempt to engage students in the lesson. Teachers also attributed students’ poor achievement to their students’ low English proficiency (Otaala & Plattner, 2013) rather than to their own ineffective teaching. As Ryan and Deci (2017) point out, these are compensation strategies which give teachers a sense of accomplishment and somehow fulfil teachers’ need for feeling competent.

Reassuringly, not all of our teachers were equally susceptible to these demotivating forces. Seven of the teachers in our sample took a much more optimistic approach to student demotivating factors, regarding them not as a barrier, but as a professional challenge – something that should be addressed rather than dumped in the “too hard” basket. They felt sufficiently competent and self-efficacious (Bandura, 1977) to influence and engage their students in learning. Optimistic teachers also showed more patience and tolerance towards students’ challenging behaviours and limited English language proficiency. Instead of blaming students for their poor performance, they acted on the belief that it was the teachers’ responsibility to improve students’ motivation and performance (Hoy et al., 2006; Ngidi, 2012). Previous research also shows that teachers’ self-efficacy is correlated to teachers’ perceptions of opportunities and barriers during teaching (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2014). Teachers with a high sense of self-efficacy can manage their classes, overcome obstacles during teaching, and self-regulate their emotions better than those with low self-efficacy (Woolfolk et al., 1990; Zee & Koomen, 2016).

These teachers showed a high level of sympathy and understanding towards students’ limited English proficiency and poor classroom performance. They were more likely to disregard students’ weaknesses and mistakes, and less likely to blame students for not underperforming in class. Some of these teachers saw their role as extending well beyond the strict professional responsibilities of EFL instructors – they regarded themselves more as mentors or even parents choosing to apply the same care and patience with their students as they would with their children. Teaching for these teachers went beyond merely imparting knowledge and developing students’ English proficiency; they demonstrated a genuine care for their students and a strong commitment to their development. These characteristics are deeply embedded in traditional Vietnamese culture which assigns to teachers the role of ‘moral guides’ (Phan, 2008). As ‘moral guides’, teachers are expected to show great tolerance to their students, and to contribute both to students’ academic achievement and to their moral growth (Phan & Phan, 2006). Our study’s findings suggest that teachers who embraced their mission as ‘moral guides’ were less likely to be affected by students-related demotivating factors or experience a drop in the quality of their teaching as a result of exposure to demotivating factors.

6 Limitations

This paper will be incomplete without a brief acknowledgement of the current study’s limitations. While the size of the participant sample is commensurate with the scope of a small-scale case study, further research should broaden the sample to include public and private EFL institutions outside of the university sector. Likewise, it is desirable to expand the scope of the research to examine a broad spectrum of demotivating forces, not just student-related factors (notwithstanding the latter’s undeniable importance). These factors might include collegial factors, school-related factors, or policy-related factors might be helpful to capture the complexities and dynamics of teachers’ demotivating process. It is also desirable to strengthen the methodology by deploying a larger and more diverse set of data collection instruments. The current study exclusively relied on self-reported data. At a minimum, structured classroom observations can be deployed in order to capture observable behaviour in real time in the classroom and match this against teachers’ self-reported data.

7 Conclusion

This study set out to examine Vietnamese EFL teachers’ perceptions of student-related demotivating factors and their impact on teachers’ emotions, attitudes, and teaching behaviours. The study confirmed that student-related factors can act as a powerful demotivator for teachers generating in them a plethora of adverse emotions. These in turn can generate negative attitudes towards teaching, often leading to a deterioration of teachers’ performance. Perhaps the study’s most noteworthy finding concerns the fact that the teachers in our participant sample were not all equally and/or uniformly affected by student-related demotivating factors. While most of them did experience adverse effects due to exposure to such demotivating factors, with negative consequences for their teaching performance, a small number of the participating teachers displayed a remarkable resilience to demotivators – they not only did not succumb to these forces, but in fact lifted their teaching performance in order to overcome them. All of these high-performing teachers shared a strong sense of self-efficacy, optimism and high tolerance to their students. These seem to be properties which promote teachers’ resilience and diminish their demotivating experience. Ultimately, it seems crucially important to gain an in-depth understanding of resilience as a key psychological construct in teachers and develop a set of measure that will support and improve teachers’ emotional regulation and problem-solving skills.

References

Ames, C. (1984). Competitive, coorperative, and individualistic goal structures: A cognitive-motivational analysis. In C. Ames, & R. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation in education (3 vol., pp. 177–207). Academic Press

Atkinson, E. S. (2000). An investigation into the relationship between teacher motivation and pupil motivation. Educational Psychology, 20(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/014434100110371

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.08.006

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Breach, D. (2004). What makes a good teacher? Teacher’s Edition, 16, 30–37

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

Dinham, S., & Scott, C. (1998). A three domain model of teacher and school executive career satisfaction. Journal of Educational Administration, 34(6), 362–378. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578239810211545

Dinham, S., & Scott, C. (2000). Moving into the third, outer domain of teacher satisfaction. Journal of Educational Administration, 38(4), 379–396. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230010373633

Dörnyei, Z. (1990). Conceptualizing motivation in foreign language learning. Language Learning, 40(1), 46–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1990.tb00954.x

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Teaching and researching motivation. Longman

Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (1998). Ten commandments for motivating language learners: Results of an empirical study. Language Teaching Research, 2(3), 203–229. https://doi.org/10.1191/136216898668159830

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed.). Longman/Pearson

Falout, J., Elwood, J., & Hood, M. (2009). Demotivation: Affective states and learning outcomes. System, 37(3), 403–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2009.03.004

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. E. Arnold

Guilloteaux, M. J., & Dönyei, Z. (2008). Motivating language learners: A classroom-oriented investigation of the effects of motivational strategies on student motivation. TESOL Quarterly, 42(1), 55–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/40264425

Hagenauer, G., Hascher, T., & Volet, S. (2015). Teacher emotions in the classroom: Associations with students’ engagement, classroom discipline and the interpersonal teacher-student relationship. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 30(4), 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-015-0250-0

Han, J., & Yin, H. (2016). Teacher motivation: Definition, research development and implications for teachers. Teacher and Teaching, 3(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1217819

Hettiarachchi. (2013). English language teacher motivation in Sri Lankan public schools. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 4(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.4.1.1-11

Hoang, V. V. (2010). The current situation and issues of the teaching of English in Vietnam. Ritsumeikan Studies in Language and Culture, 22(1), 7–18

Hoy, W. K., Tarter, C. J., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2006). Academic optimism of schools: A force for student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 43(3), 425–446. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312043003425

Jesus, S. N., & Lens, W. (2005). An integrated model for the study of teacher motivation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54(1), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00199.x

Kim, T. Y., Kim, Y. K., & Zhang, Q. M. (2014). Differences in demotivation between Chinese and Korean English teachers: A mixed-methods study. Asia-Pacific Edu Res, 23(2), 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0105-x

Kitching, K., Morgan, M., & O’Leary, M. (2009). It’s the little things: Exploring the importance of commonplace events for early-career teachers’ motivation. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 15(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600802661311

Kiziltepe, Z. (2008). Motivation and demotivation of university teachers. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 14(5–6), 515–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600802571361

Le, L. T., & Dwyer, L. G. (2019). Revisiting “teacher as moral guide” in English language teacher education in contemporary Vietnam. In N. T. Nguyen & L. T. Tran (Eds.), Reforming Vietnamese higher education: Global forces and local demands (pp.245–267). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8918-4_13

MacIntyre, P. D., Mackinnon, S. P., & Clément, R. (2009). Toward the development of a scale to assess possible selves as a source of language learning motivation. In Z. Dörnyei, & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, Language, Identity and the L2 Self (pp. 193–214). Multilingual Matter

Ngidi, D. P. (2012). Academic optimism: An individual teacher belief. Educational Studies, 38(2), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2011.567830

Nguyen, H. T. M., & Hall, C. (2017). Changing views of teachers and teaching in Vietnam. Teaching Education, 28(3), 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2016.1252742

Nguyen, N. T. (2019). Cultual modalities of Vietnamese higher education. In N. T. Nguyen & L. T. Tran (Eds.), Reforming Vietnamese higher education (pp.17–36). Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8918-4_2

Nguyen, T., Mai, H., & Hall, C. (2017). Changing views of teachers and teaching in Vietnam. Teaching Education, 28(3), 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2016.1252742

Noels, K. A., Clément, R., & Pellettier, L. G. (2001). Intrinsic, extrinsic and integrative orientations of French Canadian learners of English. Canadian Modern Language Review, 57(3), 424–442. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.57.3.424

Otaala, L. A., & Plattner, I. E. (2013). Implicit beliefs about English language competencies in the context of teachng and learning in higher education: A comparison of university students and lecturers in Namibia. International Journal of Higher Education, 2(3), 123–131. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v2n3p123

Pennington, M. C. (1995). Work satisfaction, motivation, and commitment in teaching English as a second language.

Pham, T. H. T. (2011). Implementing a student-centered learning approach at Vietnamese higher education institutions: Barriers under layers of causal layered analysis (CLA). Journal of Future Studies, 15(1), 21–38

Pham, T. N., & Bui, L. T. P. (2019). An exploration of students’ voices on the English graduation benchmark policy across Northern, Central and Southern Vietnam. Language Testing in Asia, 9(15), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-019-0091-x

Phan, L. H. (2008). Teaching English as an international language: Identity, resistance and negotiation. Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Phan, L. H., & Phan, V. Q. (2006). Vietnamese educational morality and the discursive construction of English language teacher identity. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 1(2), 136–151. https://doi.org/10.2167/md038.0

Pourtoussi, Z., Ghanizadeh, A., & Mousavi, V. (2018). A qualitative in-depth analysis of the determinants and outcomes of EFL teachers’ motivation and demotivation. International Journal of Instruction, 11(4), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2018.11412a

Reeve, J. (2009). Why teachers adopt a controlling motivating style toward students and how they can become more autonomy supportive. Educational Psychologist, 44(3), 159–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520903028990

Reeve, J., & Su, Y. L. (2014). Teacher motivation. In M. Gagne (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of work engagement, motivation, and Self-determination theory (pp. 349–362). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199794911.013.004

Roth, G. (2014). Antecedents and outcomes of teachers’ autonomous motivation: A Self-Determination theory analysis. In P. W. Richard, H. M. G. Watt, & S. A. Karabenick (Eds.), Teacher motivation: Theory and practice. Rutledge

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2010). Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: A study of relations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4), 1059–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.11.001

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2014). Teacher self-efficacy and perceived autonomy: Relations with teacher engagement, job satisfaction, and emotonal exhaustion. Psychological Reports, 114(1), 68–77. https://doi.org/10.2466/14.02.PR0.114k14w0

Sugino, T. (2010a). Teacher demotivational factors in the Japanese language teaching context. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 3, 216–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.036

Sugino, T. (2010b). Teacher/students motivational/demotivational factors in a framework of SLA motivational research. Journal of National Defense Academy (Humanities and Social Sciences), 100, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.036

Sutton, R. E. (2005). Teachers’ emotions and classroom effectiveness: Implications from recent research. The Clearing House, 78(5), 229-234

Trinh, T. T. H., & Mai, T. L. (2019). Current challenges in the teaching of tertiary English in Vietnam. In J. Albright (Ed.), English tertiary Education in Vietnam. Routledge

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

Wild, T. C., Enzle, M. E., Nix, G., & Deci, E. L. (1997). Perceiving others as intrinsically or extrinsically motivated: Effects on expectancy formation and task engagement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(8), 837–848. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167297238005

Woolfolk, A. E., Rossof, B., & Hoy, W. K. (1990). Teachers’ sense of efficacy and their beliefs about managing students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 6(2), 137–148

Yadin, S. (2012). Factors causing demotivtion in EFL teaching process: A case study. The Qualitative Report, 17(101), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.10n.2p.56

Yaghoubinejad, H., Zarrinabadi, N., & Nejadansari, D. (2017). Culture-specificity of teacher demotivation: Irian high school teachers caught in the newly-introduced CLT trap!. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 23(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1205015

Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 981–1015. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626801

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of an Australian university. The approval number is H-2018-0185.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A: An example of an analysis schedule

Appendix A: An example of an analysis schedule

Meaning unit | Code | Sub-headings | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

Normally, I often provide my students with knowledge that is not covered in textbooks. But when I don’t feel enthusiastic and motivated for teaching, I don’t want to do it [provide expanded knowledge] anymore. | Less effort in teaching | Less effort in teaching | Teachers whose teaching practice was negatively affected by student-related demotivating factors |

Seeing students’ negative attitudes and rudeness in class, I find they don’t respect what I have done for them. They never know how hard I work to prepare lessons to teach them. | Lack of respect for effort teachers | Lack of respect for effort teachers | Teachers with negative perceptions of student-related demotivating factors |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tran, L.H., Moskovsky, C. Students as the source of demotivation for teachers: A case study of Vietnamese university EFL teachers. Soc Psychol Educ 25, 1527–1544 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-022-09732-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-022-09732-4