Abstract

South-Western Ukrainian dialects have retained the option of auxiliary clitics in the formation of the past tense. At the same time, they have past-tense forms without auxiliary clitics as in Northern Ukrainian dialects, and in Standard Ukrainian based on South-Eastern dialects. A sample corpus study suggests that South-Western Ukrainian also shows a higher frequency of subject pro-drop than Standard Ukrainian. The South-Western Ukrainian pattern presents the precise mirror image of the same two features in South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish. Here, the dialect adopted the option of past-tense forms without auxiliary clitics, next to those with them as in Standard Polish. At the same time, it shows a higher frequency of non-pro-drop than Standard Polish. I argue that these matching facts are the result of long- standing language contact that worked simultaneously in two directions: the increase in the use of an existing dialectal Ukrainian pattern under Polish influence, as well as the increase in the use of an existing dialectal Polish pattern under Ukrainian influence. As a result, both dialects show the same variation between past-tense forms with auxiliary clitics and without them, and they have mutually converging tendencies in subject pro-drop – the Ukrainian dialect adapting towards Polish pro-drop, and the Polish dialect towards Ukrainian non-pro- drop. The bi-directionality of influence in the SWU dialectal area, thus, goes beyond other, unidirectional language-contact scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper presents a first sample corpus study of the omission of subject pronouns in South-Western Ukrainian (SWU). I shall refer to this as subject pro-drop, used here as a descriptive term, and without any theoretical implications. The investigation will be a usage-based one. It does not aim at contributing to the discussion of empty categories in grammatical theory, or to the validity, or lack thereof, of a possible pro-drop parameter. As far as the use of subject pro-drop is concerned, corpus data gathered for this paper suggest an increased ratio of omitted subject pronouns in SWU compared to Standard Ukrainian (SU).

A characteristic that grammarians have long related to subject pro-drop preferences in individual Slavonic varieties is the morphological richness of their past-tense forms. The key contrast is between languages that retain a person-number auxiliary clitic or inflectional affix in the past tense, such as West Slavonic, and those that do not, such as East Slavonic. The former – so the assumed relation goes – will generally prefer subject pro-drop, while the latter will generally show the opposite preference due to their morphologically more ambiguous past-tense forms. An early observer of this was, e.g., Jakobson (1971 [1935], p. 21): “La perte des formes du présent du verbe auxiliaire et du verbe-copule exigeait qu’on introduisît dans des propositions telles que dal (< dal esi), mal (> mal est’) un pronom personnel pour exprimer le sujet (ty dal – tu as donné, on mal – il est petit).”

A well-known feature of SWU, in contrast to all other Ukrainian varieties including SU, is that they retain past-tense forms with an auxiliary person-number clitic. This would seem to tie in well with its increased ratio of pro-drop compared to SU. What often remains unmentioned though is the fact that SWU also has the typically East Slavonic past-tense forms without the auxiliary clitic as in SU. This variation represents contradictory input for subject pro-drop as a correlate. As a result, I shall claim that there is no such direct dialect-internal correlation in SWU. The motivation for the higher ratio of pro-drop in SWU compared to SU lies elsewhere. It stems from contacts with South-Eastern ‘Borderland’Footnote 1 Polish. More specifically, SWU patterns in the use of past-tense forms and subject pro-drop changed under Polish dialectal influence. At the same time, South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish accommodated its corresponding use patterns to SWU influence. The mutual influence created an area of dialectal convergence that goes beyond contact settings with a source language and a target language. I shall argue that, due to wide-spread forms of Ukrainian-Polish bi-dialectalism until WWII, both dialects were source and target at the same time.

To develop the argument, the paper will proceed as follows: The first part profiles the well-known retention of auxiliary clitics in SWU past-tense forms, albeit with greater emphasis on dialectal micro-variation than in the existing literature. The second part introduces a first sample corpus study on subject pro-drop in SWU as opposed to SU. In part three, we shall see in what way the SWU facts mirror the variation in past-tense forms and subject pro-drop in South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish. In the fourth and concluding part, I shall argue that the most natural explanation for this is mutual, i.e. bi-directional influence; at least until World War II when forms of Ukrainian-Polish bilingualism and language mixing were wide-spread in many localities of the SWU linguistic area.

2 Past-tense auxiliary clitics in South-Western Ukrainian

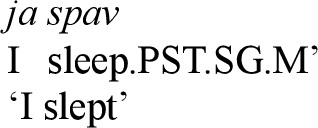

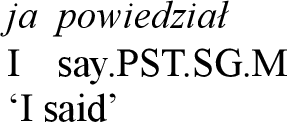

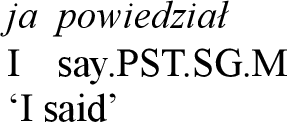

SWU dialects retain the option of first- and second-person past-tense forms consisting of the old resultative \(l\)-participle and clitics derived from the auxiliary \(be\) which expresses grammatical person and number. At the same time, they have the same past-tense forms without the auxiliary that are the only available preterits in all other Ukrainian varieties, including the standard language. To use Shevelov’s (1993, p. 996) illustration, we have both examples (1) and (2) in SWU.

-

(1)

spav=jemFootnote 2

sleep.PST.SG.M=AUX.1SG

‘I slept’

-

(2)

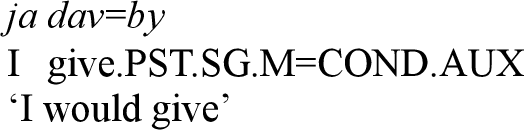

All other Ukrainian varieties have (2) only. SWU also has person-number inflected conditional auxiliaries (cf. Šylo, 1957, pp. 165–166), as shown in example (3).

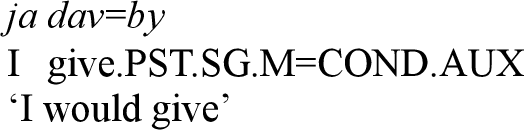

-

(3)

dav=bym

give.PST.SG.M=COND.AUX.1SG

‘I would give’

This is unlike other Ukrainian varieties, including SU, with the uninflected conditional marker only, illustrated in example (4).

-

(4)

Conditional forms do not form part of the present study. Nor shall I consider the future-tense forms consisting of the infinitive and auxiliary clitics derived from the Late Common Slavonic auxiliary *jęti. In Northern and South-Eastern Ukrainian varieties, including SU, the auxiliary has become an inflectional affix, illustrated in example (5).

-

(5)

braty-mu

take.INF-FUT.AUX.1SG

‘I will take’

In SWU, on the other hand, it remains a clitic that can attach to a host to the left of the infinitive. Since the same property applies to the auxiliary clitic in SWU past-tense forms, Danylenko (2012a) proposes a joint analysis of their development.

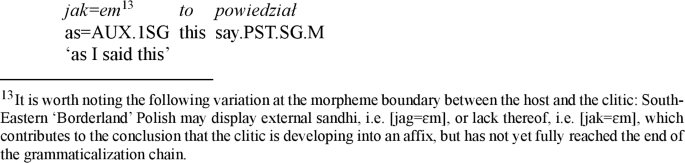

As far as the auxiliary clitics in first- and second-person past-tense forms across SWU are concerned, Danylenko (2012a, p. 13) conceives of them as the result of an “incomplete grammaticalization chain” towards inflectional past-tense affixes. The available evidence is patchy. It also comes from different points in time since the arrival of dialectological fieldwork in the SWU dialectal area from the late 19th century to the present day. What does emerge though is a strong indication that different SWU varieties have reached different points in this chain. It is noticeable that the so-called Dnister variety of SWUFootnote 3 appears to have driven this chain furthest towards person-number affixes in the past tense. On evidence from Bandrivs’kyj (1960, pp. 71–72); Bandrivs’kyj et al. (1988, map no. 245); Dejna (1957, pp. 113–117); Prystupa (1957, pp. 54–55); Rudnyćkyj (1943, p. 63); Šylo (1957, pp. 162–65); Verxrac’kyj (1912, pp. 67–68); and on evidence from some primary sources to which I shall return in due course, the paradigm that emerges of the auxiliary clitic in past-tense forms is shown in Table 1.

The key variation that Table 1 indicates for the issue at hand is in 1SG and 2SG verb-attached forms with or without the glide /j/. That is, there are forms of the clitic directly attached to the verbal stem that retain the initial glide of the original auxiliary verb, as illustrated in example (1). Crucially, however, there is good evidence that the SWU Dnister variety, unlike other SWU varieties, also developed a variant form without the glide, illustrated in example (1′).

-

(1′)

spav=em

sleep.PST.SG.M=AUX.1SG

‘I slept’

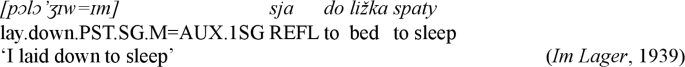

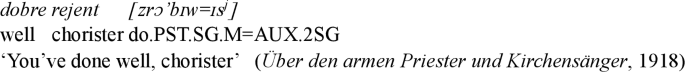

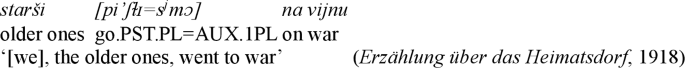

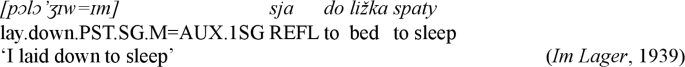

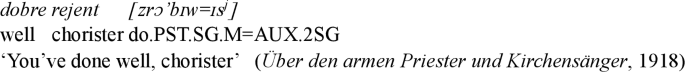

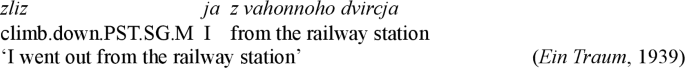

Such forms are attested too in some of the primary sources consulted for this paper, including early ones from the first half of the 20th century. Those particularly valuable for matters of phonetic substance are historical recordings, of which there are some for the SWU Dnister variety in sound archives in Vienna and Berlin. The two examples (6) and (7) are from short recorded texts by speakers of the variety under discussion.

-

(6)

-

(7)

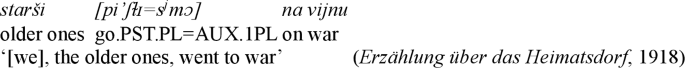

If the etymological glide of the auxiliary clitic is elided as in (6) and (7),Footnote 4 this suggests a “stronger bond of such auxiliaries with the \(l\)-stem” (Danylenko, 2012a, p. 11; cf. also Dejna, 1957, pp. 114–115). The same process, i.e. eliding a post-consonantal /j/, does not occur elsewhere other than in these particular past-tense forms. Such a morphophonological idiosyncrasy points towards affix-like characteristics (cf. Zwicky & Pullum, 1983, pp. 503–506). In other words, the omission of the glide suggests further movement of the clitic towards becoming an inflectional affix. Example (8) illustrates a plural form of the auxiliary attached to the \(l\)-stem.

-

(8)

As the glosses to examples (6)–(8) indicate, I take the past-tense meaning in these Dnister-SWU forms to be expressed by the \(l\)-form of the lexical verb. It is not plausible to include the auxiliary in the expression of past tense as it also appears in some SWU dialects as the present-tense form of the copula verb, as in the Lemkian example (9).

-

(9)

jem

be.PRS.1SG

‘I am’

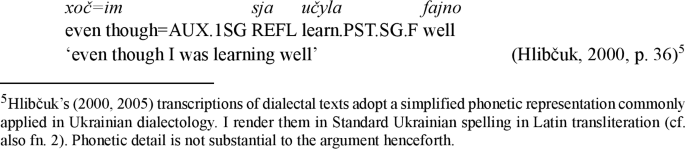

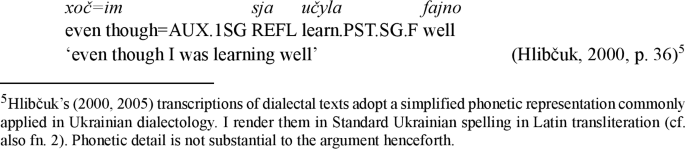

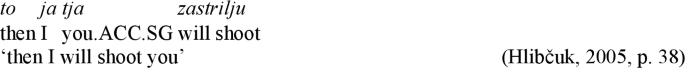

The auxiliary clitic, in turn, expresses person, number, as well as mood. It has, however, not yet been fully grammaticalized as a person-number affix. This is in evidence from the fact that the auxiliary clitic remains moveable. In Zwicky’s & Pullum’s terms, it displays the clitic-like characteristic of “a low degree of selection with respect to the[ir] hosts” (1983, p. 503). It may in fact attach to a wide range of clause-initial hosts, i.e. in the so-called ‘Wackernagel’ position. An illustrative example comes from a second set of sources. These are two collections of transcribed SWU recordings collected in the 1990s in dialectological fieldwork supervised by Hlibčuk (2000, 2005). The respondents all belong to the oldest generation of speakers whose language acquisition took place in the interwar period; i.e. at a time when the Dnister-variety area of SWU formed part of the Second Polish Republic. That is, these speakers are one or two generations later than the speakers of examples (6)–(8) are. This means that, following the integration of the area into Soviet Ukraine after WW II, they had stronger exposure to SU than their predecessors had. Nevertheless, their dialectal grammar retains the auxiliary clitic, including in non-verb adjacent position, as illustrated in example (10).

-

(10)

It is not possible in the present context to assess in further detail the status of the past-tense auxiliary in SWU with reference to the long-standing scholarly discussion of the clitic-affix distinction. The data presented in this section point towards the following conclusion: While the past-tense auxiliary continues to show some clitic-like characteristics there are also signs of a competing affix-like behaviour. This suggest that it is developing into an inflectional affix in the SWU Dnister variety under consideration here.

At this point, it is important to recall that SWU, including the Dnister variety, has the pan-Ukrainian past-tense forms without the auxiliary clitic too. That is, there is variation between the dialectal form illustrated in example (1′) and the pan-Ukrainian form (2). The sources mentioned above suggest that the latter clearly dominates in the SWU Dnister variety of all generations. I shall return to this point in the next section on subject pro-drop.

3 Subject pro-drop in South-Western Ukrainian

The present section presents a first sample corpus study of subject pro-drop in the SWU Dnister variety in comparison with SU. It suggests that the dialect employed subject pro-drop more frequently than SU. To my knowledge, subject pro-drop in SU has not yet been investigated in detail. As far as the Slavonic languages are concerned, generative grammar has focussed on Russian in particular, albeit with conflicting results. For instance, Kosta (1992, p. 471) analyses Russian as a subject pro-drop language. Franks (1995, p. 292) comes to the opposite conclusion – and, in passing, he includes Ukrainian here too. The differing views were about the theoretical question of whether in Russian and other Slavonic languages an empty pro can have case and can agree with the finite verb with respect to the relevant morphological categories. As mentioned earlier, the present paper does not aim at making a contribution to the theoretical discussion of subject pro-drop, which has evolved further since the adoption of the Minimalist Programme (cf. Holmberg, 2010).

For the present purposes, I shall adopt a usage-based approach. Following McShane (2009), I depart from the generalization that the “baseline”, i.e. default subject realization in Ukrainian is overt, and that syntactic, pragmatic and stylistic factors allow for overruling it in favour of dropping a subject pronoun. In his very brief remarks on the subject, Shevelov (1963, p. 84) suggests the same, stating “a general tendency to expression of both centres of the sentence” in Ukrainian, i.e. the predicate and the subject (cf. also Ševel’ov 2012 [1951], p. 113). As indicated earlier, the factors allowing for subject pro-drop in Ukrainian still await detailed study. It is not the aim of this section to fill this gap.

Rather, it proposes a first empirical enquiry into the frequency of subject pro-drop in SU in comparison with the dialect under investigation, i.e. the SWU Dnister variety. Meyer (2009) has identified the key methodological challenge in a comparative corpus study of this kind. In simplified fashion, the challenge is the following. After parsing the corpus material into individual predications, i.e. clauses, the analyst needs to identify the clauses where, according to the available data, pro-drop can compete with non-pro-drop at all. For the present study, I operationalise this crucial principle in two ways. I exclude clauses where the competition can clearly not occur. For those included, the count differentiates first- and second-person predicates from third-person predicates, and present-tense forms from past-tense forms. This is on the assumption that subject pro-drop may correlate with these distinctions in verbal forms, to which I shall return below.

As to exclusions, the following are the most obvious types of predicates that cannot have an overt subject at all, or do not have one by default as per the corpus data considered: elided predicates (see (11)); predicates with an indefinite, impersonal or generic animate subject (see (12)); coordinated clauses (see (13)); non-agreeing predicates, often labelled ‘impersonal’ in the Slavonic languages (see (14)); non-finite predicates, i.e. gerunds and infinitives (see (15)); subject relative clauses; and imperatives, even if in the corpus data studied these may occasionally have an overt focussed subject pronoun (see (16)).

-

(11)

daly jedno meni nakrytysja / jedno tij divčyniFootnote 5

‘they gave me one [blanket] to cover myself / [and] one to that girl’

(Hlibčuk, 2005, p. 40)

-

(12)

i po mene vstupili

‘they [unspecified agents] came inside after me’ (Hlibčuk, 2005, p. 38)

-

(13)

i vin buv u tij miliciї nimec’kyj / i pustiv

‘and he was in this German military police / and let [us] go’

(Hlibčuk, 2005, p. 38)

-

(14)

їx dva prišlo

‘there came two of them’ (Hlibčuk, 2005, p. 38)

-

(15)

dvadcjat’ p”jat’ ariv daly / aby posadyty bul’by ditjam

‘they gave [us] 25 ares / to plant potatoes for the children’ (Hlibčuk, 2000, p. 36)

-

(16)

jdy ty durnyj Kostju

‘you go, silly Kost’!’ (Hlibčuk, 2005, p. 40)

Vice versa, it is necessary to exclude clauses with overt subjects that cannot be dropped. This applies to most full noun phrases, as well as some sporadic examples of pronominal subjects other than personal pronouns, in so far as they typically indicate the introduction of a new, i.e. otherwise irretrievable discourse topic (see (17)–(18)), or they are focussed, including thetic clauses (see (19)). Occasionally, however, an overt subject noun phrase may effectively function as an honorific pronoun, which then does not warrant exclusion (see (20)). Conversely, exclusion is warranted in the case of clauses that are predicated of a focussed or contrastively topicalized subject pronoun (see (21)).

-

(17)

takyj plac buv / derevo roslo / a mij tato vyjšov

‘there was this square / a tree grew / and my dad went out’ (Hlibčuk, 2005, p. 40)

-

(18)

prijšov jeden takyj s toho sela

‘there came some person from that village’ (Hlibčuk, 2005, p. 37)

-

(19)

pryjšov toj storož

‘there came that warden’ (Hlibčuk, 2005, p. 40)

-

(20)

ne daly toho pal’cja rizaty / potim mama zaslably

‘(they [Mum] did not let that finger be cut off] / then Mum became weak’

(Hlibčuk, 2005, p. 36)

-

(21)

i tak mama vže vmerla / a ja prjala kužil’

‘and so Mum had died already / and it was me who span the sliver’

(Hlibčuk, 2005, p. 36)

Factors pertaining to the status of the subject in terms of information structure are notoriously difficult to apply consistently, as Meyer (2009, p. 388) points out. For the present study, I made exclusions contingent on the above mentioned syntactic, semantic and pragmatic factors that leave no doubt that the subject must be dropped or, conversely, must not be dropped in a given clause. This still leaves in the count some clauses that may have been erroneously qualified as potentially variable with respect to subject pro-drop. The respective decisions can be retrieved from the replication data for this section available at The Tromsø Repository of Language and Linguistics (Fellerer, 2022).

Other than for necessary exclusions, the corpus data also need to be controlled for the type of texts studied. Subject pro-drop may after all vary considerably in, say, scientific writing compared to epistolary prose. For tokens from the SWU Dnister variety under investigation in this paper, the corpus data are two sequences of together 460 clauses from Hlibčuk’s collections of dialectal texts, introduced in the previous section. The two randomly chosen sequences are from two different respondents, born in 1923 and in 1934. They are orally delivered, short memoirs (Hlibčuk, 2000, pp. 36–37, 2005, pp. 36–40). The comparative data for SU are three randomly chosen sequences of together 460 clauses from Lisovyj (2014, pp. 114–120), and from Krušel’nic’ka and Trypačuk (2001, pp. 28–31, 41–43). These are the memoirs of the philosopher and dissident Vasyl’ Lisvovyj, born near Kyiv in 1937, and the archaeologist Larysa Krušel’nic’ka, born in Lviv in 1928. Krušel’nic’ka’s memoirs also include quotations of reminiscences by her mother and grandmother. Applying the exclusion criteria outlined at the beginning of this sections, the relevant dialectal tokens were 231 as opposed to 141 relevant SU tokens.Footnote 6

For these, the count distinguishes them according to the grammatical person of the subject, and the verbal form. These basic morphosyntactic distinctions operationalise the following two assumption: The contrast between deictic first- and second-person subjects versus referential or anaphoric third-person subjects may have an impact on the application of subject pro-drop. Equally, the richness of verbal morphology may influence subject pro-drop. Present-tense forms, both perfective and imperfective, inflect for person and number. Bare \(l\)-past-tense forms, on the other hand, distinguish number and gender, but they do not inflect for person. In SU, past-tense forms with the auxiliary clitic are not available. In the SWU Dnister variety such past-tense forms are available, next to the corresponding SU forms without the auxiliary clitic. The thus configured data yield the count of subject pro-drop tokens as reported in Table 2.

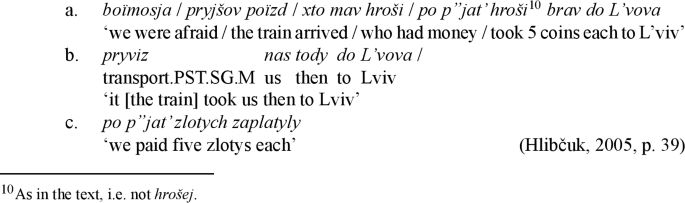

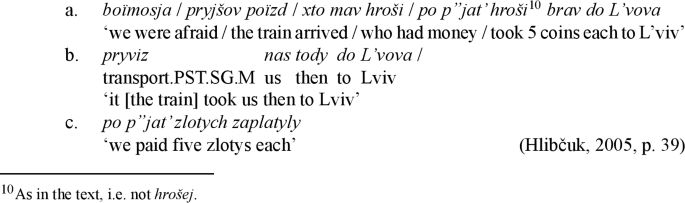

The case study reported in Table 2 is clearly small and based on author-devised and manually annotated corpus data.Footnote 7 The results, thus, need to be treated with caution and require corroboration in future studies. The small data set still presents a reasonably coherent picture as far as the main issue at hand in this paper is concerned. It suggests that subject pro-drop shows different tendencies in the SWU Dnister variety than in SU. Table 2 suggests an overall tendency for subject pro-drop to be more frequent in the SWU Dnister variety than in SU (SWU: 54% vs. SU: 31%). As to more detailed contrasts, the SWU Dnister variety does not display preference for subject pro-drop in the two morphosyntactic contexts where we expect it most from the point of view of the SU data: i.) with first-person (and rarely attested second-person) forms, which are referentially unambiguous, over third-person forms (SWU 1st (2nd): 44% < 3rd: 67% vs. SU 1st (2nd): 38% > 3rd: 25%); and ii.) with present-tense forms, which are inflected for person and number, over bare \(l\)-past-tense forms (SWU present: 51% ≈ \(l\)-past: 50%Footnote 8 vs. SU present: 60% > \(l\)-past: 20%). Thus, in the SWU Dnister variety we find subject pro-drop with third-person bare \(l\)-past-tense forms, such as in example (22-b), with the relevant context in (22-a) and (22-c).

-

(22)

Given the context in (22-a) and (22-c), the dropped subject pronoun in (22-b) is unexpected from the point of view of modern SU. It refers back to poїzd ‘train’ across a succession of two clauses with a different subject.

A further conclusion we can draw from Table 2 is that past-tense forms with the auxiliary clitic occur, as expected, in the dialect only, as illustrated in examples (1), (1′), (6)–(8), (10). However, the absolute number of these forms is small. Generally, the SWU Dnister dialect under investigation prefers the same \(l\)-past-tense forms without the auxiliary clitic as SU. Almost all of the 17 attested tokens with the auxiliary clitic have co-occurring subject pro-drop.

It is tempting to construe a joint, dialect-internal explanation of these two features, i.e. the increased use of subject pro-drop, and the availability of auxiliary clitics in the past tense. Franks and Holloway King (2000, p. 196) draw the conclusion “that whereas standard Ukr[ainian], like Rus[sian], is not pro-drop, dialects that preserve the person marking in the past tense are, like Pol[ish]”. As mentioned earlier, the idea that there is a systematic link between subject pro-drop and the morphological richness of the verbal paradigm has a long tradition in the study of Slavonic languages (cf. Jakobson 1971 [1935], p. 21). The link is also regularly called upon in the study of SWU dialects (cf. Bandrivs’kyj, 1960, p. 71; Dejna, 1957, p. 113; Šylo, 1957, pp. 163–64).

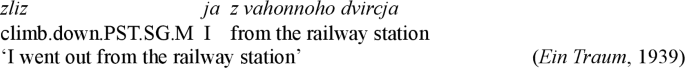

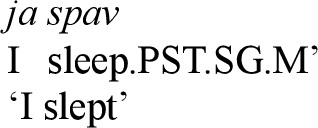

However, the available evidence does not support such a straightforward link. In the SWU Dnister dialect, the dialectal past-tense forms with the auxiliary clitic compete with those without the clitic. In fact, as we have seen from Table 2, the dialectal forms are less frequent. Many of Hlibčuk’s (2000, 2005) respondents do not use them at all. The dialectal evidence from one to two previous generations of dialect speakers points towards the same conclusion. The early recordings of the SWU Dnister variety in sound archives in Vienna and Berlin consulted for this study include texts that lack the dialectal past-tense forms altogether too, as illustrated in example (23).

-

(23)

If the dialect has variation in its past-tense forms – mostly without the clitic auxiliary, and occasionally with it –, I conclude that the subject pro-drop properties of the dialect cannot be a direct correlate. The increased use of subject pro-drop in the SWU Dnister variety compared to SU requires a different motivation than linking it straightforwardly with morphologically rich past-tense forms, i.e. with the availability of past-tense forms with the person-number inflected clitic auxiliary. In the following two sections, I shall argue that language contact with South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish provides the relevant motivation. I shall first turn to comparing SWU past-tense forms and subject pro-drop with South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish. In the final, concluding section, I shall propose a specific language-contact scenario that motivates the attested linguistic facts.

4 Convergence with South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish

Until WW II, there was wide-spread language contact between the SWU Dnister dialect and South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish, in particular in the towns and cities of the region. This was due to imbalanced social bilingualism that made it necessary for many Ukrainian dialect speakers to acquire Polish, rather than SU. For the linguistic effects of this, let us first turn to the past-tense auxiliary clitic.

As Danylenko (2012a, pp. 11–16) rightly argued, the auxiliary in the past-tense forms of various SWU varieties, such as Hucul and Rusyn, retains a degree of segmental and prosodic independence from the verbal \(l\)-forms that sets it apart from its development into a person-number affix. However, this does not apply in the same way to the SWU Dnister variety. Here, as we have seen in Sect. 2, the auxiliary shows stronger phonological integration with the verbal \(l\)-form (cf. examples (1′), (6), and (7)). At the same time, it remains moveable and can readily cliticize to a clause-initial host (cf. example (10)). South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ PolishFootnote 9 turns out to be at the same grammaticalization stage of the auxiliary clitic becoming an affix. It retains greater segmental and prosodic independence from the verbal \(l\)-form than in Standard Polish. The most important piece of evidence towards this conclusion comes from the following fact: The auxiliary may agglutinate to the \(l\)-verbal form like an affix, but, unlike Standard Polish, it does not cause the stress to shift when it attaches to the \(l\)-form host. That is, for instance, the Standard Polish form in (24) contrasts with the dialectal form in (24′).

-

(24)

powiedział-em

[pɔvʲjɛ’ʥaɫ-ɛm]

say.PST.SG.M-1SG

‘I said’

-

(24′)

powiedział=em

[pu’vʲjɛʥaɫ=ym]Footnote 10

say.PST.SG.M=AUX.1SG

‘I said’

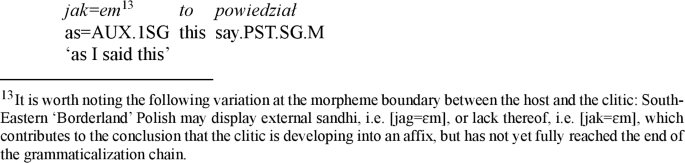

Thus, unlike Standard Polish, the auxiliary clitic is not yet a prosodically fully integrated affix. In the same vein, South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish shows a preference to float the auxiliary clitic to a range of clause-initial hosts, as illustrated in (25).

-

(25)

This is in contrast with the development in modern Standard Polish towards non-floated affixes in the past tense (cf. Kowalska, 1976, pp. 40–46). Thus, South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish retains a greater degree of segmental independence of the past-tense clitic auxiliary than Standard Polish. What is more, and has been observed for a long time (cf. Lehr-Spławiński, 1914, p. 47), South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish employs affixless past-tense forms too, as illustrated in example (26).

-

(26)

This is in stark contrast with Standard Polish where the only possible form is the one shown in (24). The dialectal innovation in (26) has cognates in Polish dialects that are not adjacent to Ukrainian, but its particularly wide-spread use across all first- and second-person past-tense forms in South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish clearly distinguishes this variety from other Polish dialects.

In Sect. 2, we saw the same variation in the SWU Dnister variety. Past-tense forms without the auxiliary clitic in the first and second person compete with forms with it. The auxiliary retains a degree of prosodic and syntactic independence from the verbal \(l\)-form that still qualifies it as a clitic. At the same time, it can readily aggulinate to the verbal \(l\)-form, with some ensuing phonological effects that are specific to that morphological context. In absolute terms, the past-tense forms with the auxiliary clitic are significantly less frequent in the SWU Dnister dialect than in South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish.

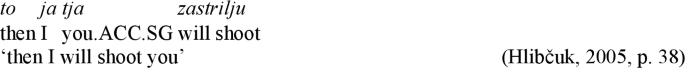

Turning to subject pro-drop, South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish shows the following characteristics: If the past-tense auxiliary clitic is present, the subject is almost always dropped (see example (24′)). The use of an overt subject pronoun is strongly dispreferred in this context, according to dialectal corpus data (see fn. 11). Vice versa, with bare first- and second-person \(l\)-past-tense forms, subject pro-drop is not available at all. That is, the form illustrated in (26) is the only available one in South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish. This hitherto unobserved regularity automatically produces a higher proportion of subject pronouns in the dialect. In Standard Polish, on the other hand, the “baseline subject realization”, in McShane’s (2009) terms, is “elided”. That is, the default is for a subject pronoun to be omitted, unless certain syntactic, pragmatic or stylistic factors overrule this. The increased use of pronominal subjects in South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish also extends to third-person past-tense and to present-tense forms. To be sure, pro-drop remained the preferred variant in these contexts, albeit by a smaller margin than one would expect from the point of view of Standard Polish.

In Sect. 3, we saw a complementary picture in the SWU Dnister dialect. Compared to SU, the SWU Dnister variety has a stronger propensity for subject pro-drop in general. Similar to South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish, subject-pronoun omission is almost always required with first- and second-person past-tense forms with the auxiliary clitic, as in examples (1)–(1′).

Table 3 summarizes these comparative facts.

Within each of the two feature categories, the first line in Table 3 refers to the quantitatively prevailing pattern. Thus, the SWU Dnister variety has first- and second-person past-tense forms, both without the auxiliary clitic (‘–’) and with it (‘+’). The former is the preferred variant. The same applies to South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish, albeit with a less pronounced propensity for bare \(l\)-past-tense forms than SWU. SU has the bare forms only, while Standard Polish has the suffixed ones only. Elided subject pronouns (‘–’) in the SWU Dnister variety are, overall, slightly more frequent than overt ones (‘+’) in comparable contexts. The same applies to South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish, albeit with a considerably more pronounced propensity for omission. The latter is the default subject realization of Standard Polish, as opposed to a tendency towards pronominal subjects in SU.

Thus, Table 3 shows that the SWU Dnister variety converges with South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish with respect to the two features discussed. Before I proceed to proposing a language-contact induced motivation, it is worth pausing on a further shared feature. This is the availability of clitic forms of personal pronouns in SWU (cf. Franks & Holloway King, 2000, pp. 199–201), including the Dnister variety, and unlike SU, as shown in examples (27) and (28).

-

(27)

-

(28)

Pronominal clitic forms, such as SWU dative my ‘me’ and accusative / genitive tja ‘you’, are not available in SU. SU has the corresponding orthotonic forms only, such as meni and tebe. Standard Polish, on the other hand, does have parallel enclitic and orthotonic pronominal forms, which are also in use in South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish. However, the distribution is different. In Standard Polish, the orthotonic forms are chosen only if the pronoun is in a focus position. South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish uses them well beyond this specific context. For example, in (29) the orthotonic pronominal accusative form jego ‘him’, instead of the clitic form go ‘him’, is a clear dialectalism that would require contrastive focus in Standard Polish.

-

(29)

czegu ty jego namawiał, ży on sie żeni z Krysiu

‘why were you persuading him that he should marry Krysia’Footnote 11

These facts suggest that SWU and South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish also converge on using pronominal forms differently from their respective standard language. SWU has clitic forms, unlike SU, but like Polish. South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish has both, like Standard Polish. However, it shows an increased use of the orthotonic forms in contexts where it can occur in Ukrainian, but not in Standard Polish.

What emerges overall is that the SWU Dnister variety shares with South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish the following three characteristics: the availability of clitic forms of personal pronouns; a tendency towards subject pro-drop; and the availability of past-tense forms with an auxiliary clitic that is developing into an affix. As argued before, it is unlikely that these shared features are the result of independent, dialect-internal developments. Instead, in the following concluding section I shall propose that they represent a contact-induced increase in “grammatical use patterns” (cf. Heine & Kuteva, 2006, pp. 48–96) that works in both directions; i.e. in the SWU Dnister variety under the influence of South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish, and vice versa.

5 Conclusion: mutual language contacts

The past-tense forms with the auxiliary clitic are an inherited feature in SWU. As we saw in Sect. 2, the auxiliary has advanced furthest towards becoming a person-number affix in the Dnister variety. It has not yet fully completed this grammaticalization chain though. The emergence of this feature can be motivated as follows: When native SWU Dnister dialect speakers acquired knowledge of South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish as the dominant vernacular of their region until WW II, they imposed upon the Polish dialect the typically Ukrainian past-tense forms without the auxiliary clitic. The pattern was not altogether alien to South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish, but it expanded significantly due to Ukrainian imposition. Subsequently, native SWU Dnister dialect speakers with established knowledge of South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish re-imposed upon their Ukrainian dialect the typically Polish past-tense forms with the auxiliary clitic. The pattern was well established in SWU, but the bond between the auxiliary clitic and the \(l\)-verbal base further strengthened in the Dnister variety due to Polish re-imposition (cf. also Danylenko, 2012b).

As to subject pro-drop, this is an existing option in SWU, as it is in SU. However, as we saw in Sect. 3, the SWU Dnister dialect employs it more frequently than SU across all morphosyntactic contexts. Mutual language contact with South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish can again explain the resulting facts. As native SWU Dnister dialect speakers acquired knowledge of South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish they imposed upon the Polish dialect the typically Ukrainian preference for subject pronouns. In the case of the past-tense forms without the auxiliary clitic, the Polish dialect made this the rule. In the case of other verbal forms, it produced an increase of subject pronouns that sets South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish apart from Standard Polish. Subsequently, native Dnister dialect speakers with established knowledge of South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish re-imposed upon their Ukrainian dialect the typically Polish preference for subject pro-drop. This is true of the SWU past-tense forms with auxiliary clitics in particular, but it also affected other past- and present-tense predications. As a result, the SWU Dnister variety shows a stronger propensity for subject pro-drop than SU.

As mentioned before, a corpus-based computation of subject pro-drop vs. non-pro-drop meets various serious challenges. First, in the present study the sample size is small. Second, it requires various decisions on the part of the analyst to identify the predicates where pro-drop and non-pro-drop, i.e. the presence or omission of a subject pronoun can compete at all. And third, the type of texts studied needs to be comparable because pro-drop is subject to considerable stylistic variation in the Slavonic languages. As Nilsson (1982) has shown, colloquial Polish has greater tolerance for the use of subject pronouns than written Standard Polish. Conversely, if colloquial Ukrainian behaves like colloquial Russian, it will have greater tolerance for subject pro-drop than written Standard Ukrainian.

Despite these potentially distorting factors, I maintain that the comparative results summarized in Table 3 capture real convergences between the SWU Dnister variety and South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish that set them apart from their respective standard varieties. This is not so because any of the variants discussed, i.e. the presence vs. omission of a subject pronoun, and past-tense forms with vs. without auxiliary clitics, were alien to any one of the two dialects and, thus, the product of direct borrowing. It is rather due to changes in grammatical use patterns. These, in turn, may have had further consequences, such as the evolution of a rule in South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish that subject omission with bare first- and second-person \(l\)-past-tense forms is not permissible. The argument that these changes are due to language contact hinges on two basic facts. First, the changes in the SWU Dnister variety closely mirror patterns in South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish, and vice versa. And second, acquisition of the Polish dialect by subsequent generations of Ukrainian dialect speakers was wide-spread till WW II due to political and social imbalances.

In this scenario, it is the bilingual Ukrainian dialect speakers where the contact-induced changes in grammatical use patterns emerged. This follows Coetsem’s (1988, p. 11) insightful concept of “source-language agentivity”: “The \(sl\) [source language] speaker-agent is the \(sl\) dominant bilingual (…), who has ‘a certain practical or functional knowledge’ of the \(rl\) [recipient language] and who applies imposition”. That is, the Ukrainian dialect speaker was the source-language speaker-agent who applied imposition on the Polish dialect as the recipient language. However, my scenario also proposes an extension to Coetsem’s concept. The Ukrainian dialect speakers who had consolidated knowledge of the Polish dialect applied re-imposition of Polish use patterns on the Ukrainian dialect as the recipient language. The linguistic proximity of the two dialects involved, and the extent of Ukrainian-Polish bi-dialectalism in the SWU-speaking area till WW II warrant this extension. Rather than with unidirectional ‘interference’ in Weinreich’s (1968 [1953]) sense, we are dealing with bi-directional convergence. This is a form of language contact reminiscent of a ‘sprachbund’, albeit involving only two languages. Ukrainian in general offers rich, often surprising and still understudied linguistic material for questions of Slavonic grammatical micro- and macro-variation, areal linguistics, and language contact.

Notes

This translates the term conventionally used in Polish dialectology, polszczyzna kresowa ‘Borderland Polish’. It appears within brackets to indicate its potentially controversial historical and political connotations.

Here and henceforth, the representation of examples adapts them to modern Ukrainian spelling in Latin transliteration, unless indicated otherwise.

The other SWU varieties that traditional Ukrainian dialectology distinguishes are: Volhynian, Bukovinian, Boikian, Lemkian, Podolian, the Sjan-variety, Hutsul, and Trans-Carpathian with separately codified Rusyn.

The relevant verbal forms are represented in IPA.

Here and henceforth, the slash indicates separate clauses. The relevant clause for illustration is the last one in each example, with any preceding ones for the relevant context. The square brackets in the English translations are my additions to clarify the intended reading of the example.

The considerably smaller number of tokens in the SU data is largely due to the fact that there is a higher number of clauses with a referential noun phrase as the subject. In most cases, these are not omissible as they introduce a new, i.e. otherwise irretrievable discourse topic. Thus, the corresponding tokens were excluded from the count.

For the current state regarding the evolving development of a Ukrainian language corpus, cf. Shvedova (2020).

The symbol ‘≈’ indicates that the proportion of subject pro-drop with present-tense forms and with bare \(l\)-past is almost the same in the SWU sample taken for this study.

The comparative linguistic evidence from South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish referred to in the remainder of this section is discussed and referenced in detail in Fellerer (2020, pp. 101–124). This includes relevant corpus data that form the basis of summative quantitative statements about South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish made in this section.

The vowel reductions in the dialectal form are immaterial for the present argument.

For the provenance of this example, and further detail about orthotonic versus clitic forms of personal pronouns in South-Eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish, cf. Fellerer (2020, p. 112).

References

Sources

Ein Traum. (1939). [Transcript of MP3 copy of gramophone record LA 1577/1]. Institut für Lautforschung an der Universität Berlin.

Erzählung über das Heimatsdorf während des Krieges. (1918). [Transcript of gramophone record Ph 2960]. Phonogrammarchiv Austrian Academy of Sciences.

Hlibčuk, N. M. (2000). Hovirky pivdenno-zaxidnoho nariččja ukraїns’koї movy: Zbirnyk tekstiv. L’viv: LNU imeni Ivana Franka.

Hlibčuk, N. M. (2005). Ukraїns’ki hovirky pivdenno-zaxidnoho nariččja: Teksty. L’viv: LNU imeni Ivana Franka.

Krušel’nic’ka, L. I., & Trypačuk, V. M. (2001). Rubaly lis… Spohady halyčanky. L’viv: L’vivs’ka naukova biblioteka im. V. Stefanyka.

Lisovyj, V. (2014). Spohady: Poeziї. Kyїv: Smoloskyp.

Im Lager. (1939). [Transcript of MP3 copy of gramophone record LA 1577/2]. Institut für Lautforschung an der Universität Berlin.

Über den armen Priester und Kirchensänger. (1918). [Transcript of gramophone records Ph 2962–63]. Phonogrammarchiv Austrian Academy of Sciences.

Literature

Bandrivs’kyj, D. H. (1960). Hovirky pidbuz’koho rajonu L’vivs’koї oblasti. Kyїv: Akademija Nauk Ukraїns’koї RSR.

Bandrivs’kyj, D. H., et al. (1988). Atlas ukraїns’koї movy: Vol. 2. Volyn’, Naddnistrjanščyna, Zakarpattja i sumižni zemli. Kyїv: Naukova dumka.

Coetsem, F. (1988). Loan phonology and the two transfer types in language contact. Dordrecht: Foris.

Danylenko, A. (2012). Auxiliary clitics in Southwest Ukrainian: questions of chronology, areal distribution, and grammaticalization. Journal of Slavic Linguistics, 20(1), 3–34.

Danylenko, A. (2012). Lota vy̆vjuh”, a pjat’ vary̆šuv’ pohubyl’: a case of Ukrainian auxiliary clitics with the element x. In A. Danylenko & S. Vakulenko (Eds.), Studien zu Sprache, Literatur und Kultur bei den Slaven: Gedenkschrift für George Y. Shevelov, München: Otto Sagner.

Dejna, K. (1957). Gwary ukraińskie Tarnopolszczyzny. Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.

Fellerer, J. (2020). Urban multilingualism in East-Central Europe: the Polish dialect of late-Habsburg Lviv. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Fellerer, J. (2022). Replication data for ‘Subject pro-drop and past-tense auxiliary clitics in South-Western Ukrainian’ (Version V.1) [Data set]. DataverseNO. https://doi.org/10.18710/UR1QAA

Franks, S. (1995). Parameters of Slavic morphosyntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Franks, S., & Holloway King, T. H. (2000). A handbook of Slavic clitics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heine, B., & Kuteva, T. (2006). The changing languages of Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Holmberg, A. (2010). Null subject paramters. In T. Biberauer, A. Holmberg, I. Roberts, & M. Sheehan (Eds.), Parametric variation: null subjects in minimalist theory, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jakobson, R. (1971 [1935]). Les enclitiques slaves. In Selected writings (Vol. 2). The Hague: de Gruyter.

Kosta, P. (1992). Leere Kategorien in den nordslavischen Sprachen: zur Analyse leerer Subjekte und Objekte in der Rektions-Bindungs-Theorie [Habilitationsschrift, Frankfurt / Main]. https://www.academia.edu/14811737.

Kowalska, A. (1976). Ewolucja analitycznych form czasownikowych z imiesłowem na -ł w języku polskim. Katowice: Uniwersytet Śląski.

Lehr-Spławiński, T. (1914). O mowie Polaków w Galicji wschodniej. Język Polski, 2, 40–51.

McShane, M. (2009). Subject ellipsis in Russian and Polish. Studia Linguistica, 63(1), 98–132.

Meyer, R. (2009). Zur Geschichte des referentiellen Nullsubjekts im Russischen. Zeitschrift für Slawistik, 54, 375–397.

Nilsson, B. (1982). Personal pronouns in Russian and Polish: a study in their communicative function and placement in the sentence. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International.

Prystupa, P. (1957). Hovirky Brjuchovec’koho rajonu L’vivs’koї oblasti. Kyїv: Vydavnyctvo Akademiї Nauk URSR.

Rudnyćkyj, J. (1943). Lemberger ukrainische Stadtmundart (Znesinnja). Berlin: Institut für Lautforschung an der Universität Berlin.

Shevelov, G. Y. (1963). The syntax of modern literary Ukrainian: the simple sentence. The Hague: Mouton.

Shevelov, G. Y. (1993). Ukrainian. In B. Comrie & G. Corbett (Eds.), The Slavonic languages, London: Routledge.

Ševel’ov, Ju. (2012 [1951]). Narys sučasnoї ukraїns’koї literaturnoї movy ta inši linhvistyčni studiї (1947–1953). Kyїv: Tempora.

Shvedova, M. (2020). The General Regionally Annotated Corpus of Ukrainian (GRAC, uacorpus.org): architecture and functionality. In V. Lytvyn et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 4th international conference on computational linguistics and intelligent systems (COLINS 2020): Vol. 1. Main conference. http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2604/.

Šylo, H. F. (1957). Pivdenno-zaxidni hovory URSR na pivnič vid Dnistra. L’viv: Vydavnyctvo L’vivs’koho deržavnoho pedahohičnoho instytutu.

Verxrac’kyj, I. (1912). Hovir Batjukiv. L’viv: Naukove Tovarystvo Ševčenka.

Weinreich, U. (1968 [1953]). Languages in contact: findings and problems. The Hague: Mouton.

Zwicky, A. M., & Pullum, G. K. (1983). Cliticization vs. inflection: English N’T. Language, 59(3), 502–513.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fellerer, J. Subject pro-drop and past-tense auxiliary clitics in South-Western Ukrainian. Russ Linguist 46, 201–216 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-022-09260-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-022-09260-x