Abstract

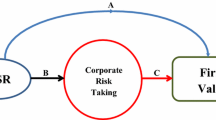

Using a sample of publicly traded U.S. REITs, we examine the impact of at-the-market (ATM) equity offerings on participating firms’ cost of capital. While ATM programs can improve a firm’s financial flexibility, capital market access, and market timing capabilities, they also may engender agency conflicts and increase the information opacity of the firm’s operations. Consistent with these adverse effects, we document a positive relation between ATM program availability and the implied cost of equity capital. These core findings are most pronounced for firms that are relatively opaque, thus providing further evidence of an information-based channel for the cost of capital effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In contrast to traditionally underwritten security offerings, where a predetermined number of shares are sold at a fixed price at a single point in time, the establishment of an ATM program grants managers the option to sporadically issue equity over an extended period at prevailing market prices. See Hartzell et al. (2019) for further details on the ATM issuance process.

It is important to note that prior research has focused on the relatively low direct costs associated with ATM share issuance as a benefit of this form of financial flexibility. For example, Hartzell et al. (2019) and Howton et al. (2018) document broker fees of approximately 2%, on average, of gross proceeds for ATM issuances.

While we recognize taxable income and cash flow are not perfectly equivalent metrics, and acknowledge many REITs routinely pay and sustain dividend payout ratios well in excess of 100% of reported net income, these mandates nevertheless provide some constraints on the ability of firms within this industry to retain cash flows.

An extensive prior literature discusses the use of cash holdings (Denis and Sibilkov 2010; Almeida et al. 2004; Dittmar and Marhart-Smith 2007; Kalcheva and Lins 2007; and Riddick and Whited 2009), low leverage policies (Marchica and Mura 2010; Ang and Smedema 2011), access to lines of credit (Ooi et al. 2012; Lins et al. 2010; and Campello et al. 2010; Sufi 2009; Hardin and Hill 2011; Harrison, Luchtenberg and Seiler, 2011), the use of secured debt financing (Stulz and Johnson 1985), and the covenant structure of unsecured debt (Riddiough and Steiner 2020) as various mechanisms for firms to achieve financial flexibility.

See Hartzell et al. (2019) for a more detailed description of the process used to identify ATM firms. Our sample period begins in 2006 as this is the first year following significant regulatory reform on eligibility requirements for ATM program access.

The use of book values in the residual income approach may understate the equity value of real estate for property portfolios that experience a significant amount of price appreciation over time. Conversely, the use of book values would overstate the equity value of real estate for property portfolios that experience significant capital depreciation over time. Thus, as real estate values were generally increasing over our sample observation interval, we recognize and acknowledge the residual income approach may, by construction, marginally understate the true cost of capital in our sample.

Lee et al. (1999) conclude using a longer period for an estimation window does not significantly affect estimates. We note that the requirement of three years of FFO data limits the window over which we can perform our analysis.

Book value of equity is forecasted using the clean surplus relation (Bt = Bt-1 + NIt –DIVt), in which dividends are assumed to be 85% of FFO. While REITs are required to pay out at least 90% of taxable income as dividends, REITs have paid approximately 71% of FFO, on average, over the past 20 years according to NAREIT. Thus, our 85% assumption is a conservative estimate of dividend payout.

It is important to note that neither of these two approaches rely on book value estimates of the real estate property portfolio as was the case with measures derived from the residual income approach. Thus, any concerns with REIT book values systematically understating true asset values due to the lack of mark-to-market accounting should be mitigated for these two alternative metrics. Reassuringly, in the empirical results which follow, all five cost of capital metrics employed provide qualitatively similarly findings and implications.

Botosan and Plumlee (2005) utilize long term earnings forecasts (e.g., Year 5 and Year 4) in place of short-run earnings forecasts to mitigate this issue. However, the low frequency of FFO forecasts available at these horizons in the IBES database precludes the use of this modified specification in our analysis.

To ease economic interpretations across cost of capital measures, we constrain the distribution of our principal component measure to have the average mean and standard deviation of our other four proxies. It is important to note that relaxing this constraint does not impact the statistical significance of our findings.

This mitigates concern that our main results may be driven by a fundamental change in the level of the cost of capital in the post-crisis period. More formally, we ensure our main results are robust to the exclusion of the crisis-period in a subsequent robustness check.

An et al. (2011) utilize a similar framework to examine the relation between REIT transparency and firm growth. However, they utilize (1-R2) to measure firm transparency rather than opacity. Consistent with An et al. (2011), we also construct this variable using lower frequency data (e.g., weekly data) to reduce any noise inherent in its construction and obtain robust results upon its inclusion in each of our empirical specifications.

As in Riddiough and Wu (2009), we eliminate observations that do not fit within the following bounds: 0 ≤ CASH ≤ 0.5.

Similarly, as firms mature, the market may gain valuable insight into the stability and consistency of a firm’s continuing operations. Such information may well reduce investor uncertainty, thereby further lowering required returns.

Cashman et al. (2016) identify clawback provisions as a value-relevant governance mechanism for equity REITs.

Institutional holdings may also enhance price discovery through increasing the available supply of shares to short, thereby facilitating the rapid incorporation of negative information into security prices.

To mitigate concern that our main ATM finding reflects a mechanical relation with our cost of capital measures that is driven by the negative stock price reaction which often accompanies equity share issuance (e.g., Jegadeesh 2000), we include quarterly lagged appreciation returns (APPRET) as an additional explanatory variable in each of our specifications and confirm our results are robust to controlling for the influence of past stock price changes. It is also important to note that Hartzell et al. (2019) find significantly less negative price reactions around the announcement of an ATM relative to a comparable SEO.

Hartzell et al. (2019) provide evidence that firm characteristics associated with a firm’s level of financial constraint, potential growth opportunities, and external monitoring impact the likelihood of establishing an ATM program. Since managerial decisions to establish an ATM program are likely to be non-random, we follow this literature and utilize a Heckman (1979) two-stage estimation to control for sample selection effects in a subsequent robustness check. We utilize average underwriter ranking scores for past seasoned equity issuances (UWRANK) to meet the exclusion requirement of the first stage regression since prior certification may influence the firm’s choice of whether to establish an ATM program. The results from the second stage regression are reported in Table IA.A1 of the Internet Appendix. The insignificant inverse mills lambda confirms that sample selection is not of prime importance in our examination of the cost of capital.

We obtain qualitatively similar results when using our other four proxies for the cost of capital, though statistical significance is reduced due to the smaller sample sizes.

It is important to note that the difference in the cost of capital prior to the establishment of an ATM program for firms that close their programs versus those that announce follow-on programs is not statistically different from zero in our univariate analysis.

Though unreported, we also find preliminary evidence that the cost of capital effect is mitigated for firms with high ATM program completion rates.

For brevity, we only report coefficient estimates for our main variables of interest in Table 5. We report coefficient estimates for each of our control variables in Table IA.A2 of the Internet Appendix.

In their comparison of ex-ante firm characteristics for ATM and SEO users outside of the REIT industry, Billett et al. (2019) identify ATM firms as being smaller, less levered, and more opaque. These differences highlight the importance of an additional line of research that examines the implications of these financing mechanisms specifically within the REIT market.

Consistent with the previous literature, we exclude t = 0 from these regressions since it is difficult to assess which quarter, before or after the event announcement, it should belong to. Examples of similar methodological approaches include Gertner et al. (2002), Brisker et al. (2013), and Howton et al. (2018), amongst others.

To mitigate concern that our cross-sectional findings are driven by our choice of OPACITY as a measure of the firm’s information environment, we construct an additional set of robustness checks utilizing two alternate measures of firm transparency: (1) the number of analysts following the firm, and (2) an indicator variable based on whether the firm is followed by Green Street Advisors, a prominent buy-side research company focused specifically on analyzing REITs. Since these information measures are increasing in the level of firm transparency (and therefore negatively correlated with our main OPACITY measure), an increase in firm transparency should help mitigate the adverse impact of ATM program access on the firm as increased transparency reduces the uncertainty associated with managerial decisions. Our results from these additional robustness checks are consistent with those using OPACITY as our measure of the firm’s information environment. A more in-depth description of these tests and associated results are reported in the Internet Appendix (Section IA.B1 and Table IA.A3, respectively).

Audit fee data were obtained from the AuditAnalytics database.

For brevity, we only report coefficient estimates for our main variables of interest in Table 9. We report coefficient estimates for each of our control variables in Table IA.A4 of the Internet Appendix.

Though unreported, multivariate tests that include the full set of firm characteristics, property type and time (quarter) fixed effects confirm the results of each of our univariate tests.

We obtain book value of equity data from S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Howton et al. (2018), amongst others, utilize a similar strategy to identify a REIT’s relative level of financial constraint.

References

Admati, A., & Pfleiderer, P. (1988). A theory of intraday patterns: Volume and Price variability. Review of Financial Studies, 1, 3–20.

Almeida, H., Campello, M., & Weisbach, M. (2004). The cash flow sensitivity of cash. Journal of Finance, 59(4), 1777–1804.

Amihud, Y. (2002). Illiquidity and stock returns: Cross-section and Tim-series effects. Journal of Financial Markets, 5, 31–56.

An, H., Cook, D., & Zumpano, L. (2011). Corporate transparency and firm growth: Evidence from real estate investment trusts. Real Estate Economics, 39(3), 429–454.

Ang, J., & Smedema, A. (2011). Financial flexibility: Do firms prepare for recession? Journal of Corporate Finance, 17(3), 774–787.

Babenko, I., Bennett, B, Bizjak, J., and Coles, J. 2014. Clawback provisions, Working Paper.

Billett, M., Floros, I., & Garfinkel, J. (2019). At-the-market (ATM) offerings. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 54(3), 1263–1283.

Botosan, C., & Plumlee, M. (2005). Assessing alternative proxies for the expected risk premium. The Accounting Review, 80(1), 21–53.

Boudry, W. I., Kallberg, J. G., & Liu, C. H. (2010). An analysis of REIT security issuance decisions. Real Estate Economics, 38(1), 91–120.

Brisker, E., Colak, G., & Peterson, D. (2013). Changes in cash holdings around the S&P500 additions. Journal of Banking and Finance, 37(5), 1787–1807.

Brown, D. T., & Riddiough, T. J. (2003). Financing choice and liability structure of real estate investment trusts. Real Estate Economics, 31(3), 313–346.

Campbell, T. (2008). A model of the market for lines of credit. Journal of Finance, 33(1), 231–244.

Campello, M., Graham, J., & Harvey, C. (2010). The real effects of financial constraints: Evidence from a financial crisis. Journal of Financial Economics, 97, 470–487.

Cashman, G., Harrison, D., & Panasian, C. (2016). Clawback provisions in real estate investment trusts. The Journal of Financial Research, 39(1), 87–114.

Chen, K., Chen, Z., & Wei, K. (2011). Agency costs of free cash flow and the effect of shareholder rights on the implied cost of equity capital. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 46(1), 171–207.

Danielsen, B., Harrison, D., Van Ness, R., & Warr, R. (2009). REIT auditor fees and financial market transparency. Real Estate Economics, 37(3), 515–557.

Danielsen, B., Harrison, D., Van Ness, R., & Warr, R. (2014). Liquidity, accounting transparency, and the cost of capital: Evidence from real estate investment trusts. Journal of Real Estate Research, 36(2), 221–251.

Denis, D., & Sibilkov, V. (2010). Financial constraints, investment, and the value of cash holdings. The Review of Financial Studies, 23(1), 247–269.

Dittmar, A., & Marhart-Smith, J. (2007). Corporate governance and the value of cash holdings. Journal of Financial Economics, 83, 599–634.

Downs, D., Guner, Z., & Patterson, G. (2000). Capital distribution policy and information asymmetry: A real estate market perspective. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 21(3), 235–250.

Easton, P. (2004). PE ratios, PEG ratios, and estimating the implied expected rate of return on equity capital. The Accounting Review, 79(1), 73–95.

Easton, P., & Monahan, S. (2005). An evaluation of accounting-based measures of expected returns. The Accounting Review, 80(2), 501–538.

Feng, Z., Ghosh, C., & Sirmans, C. F. (2007). On the capital structure of real estate investment trusts (REITs). Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 34(1), 81–105.

Gebhardt, W., Lee, C., & Swaminathan, B. (2000). Toward an implied cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 39(1), 135–176.

Gertner, R., Powers, E., & Scharfstein, D. (2002). Learning about internal capital markets from corporate spinoffs. The Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2479–2506.

Gode, D., & Mohanram, P. (2003). Inferring the cost of capital using the Ohlson-Juettner model. Review of Accounting Studies, 8, 399–431.

Gokkaya, S., Hill, M., & Kelly, G. W. (2013). On the direct costs of REIT SEOs. Journal of Real Estate Research, 35(4), 407–443.

Guay, W., Kothari, S., & Shu, S. (2011). Properties of implied cost of capital using analysts’ forecasts. Australian Journal of Management, 36(2), 125–149.

Hail, L., & Leuz, C. (2009). Cost of capital effects and changes in growth expectations around U.S. cross-listings. Journal of Financial Economics, 93(3), 428–454.

Han, B. (2006). Insider ownership and firm value: Evidence from real estate investment trusts. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 32(4), 471–493.

Hardin, W. G., Highfield, M. J., Hill, M. D., & Kelly, G. W. (2009). The determinants of REIT cash holdings. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 39(1), 39–57.

Hardin, W., & Hill, M. (2011). Credit line availability and utilization in REITs. Journal of Real Estate Research, 33(4), 507–530.

Harrison, D., Luchtenberg, K., & Seiler, M. (2011a). REIT performance and lines of credit. Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management, 17(1), 1–14.

Harrison, D. M., Panasian, C. A., & Seiler, M. J. (2011b). Further evidence on the capital structure of REITs. Real Estate Economics, 39(1), 133–166.

Hartzell, D., Howton, S., Howton, S., & Scheick, B. (2019). Financial flexibility and at-the-market (ATM) equity offerings: Evidence from real estate investment trusts. Real Estate Economics, 47(2), 595–636.

Hartzell, J., Kallberg, J., & Liu, C. (2008). The role of corporate governance in initial public offerings: Evidence from real estate investment trusts. Journal of Law and Economics, 51(3), 539–562.

Heckman, J. (1979). Sample selection Bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Howton, S., Howton, S., & Scheick, B. (2018). Financial flexibility and investment: Evidence from REIT at-the-market equity offerings. Real Estate Economics, 46(2), 334–367.

Jegadeesh, N. (2000). Long-term performance of seasoned equity offerings: Benchmark errors and biases in expectations. Financial Management, 29(3), 5–30.

Jin, L., & Myers, S. (2006). R2 around the world: New theory and new tests. Journal of Financial Economics, 79(2), 257–292.

Jiraporn, P., & Chintrakarn, P. (2009). Dividend policy, staggered boards, and managerial entrenchment. Financial Services Research, 36(1), 1–19.

Jiraporn, P., Chintrakarn, P., & Kim, Y. (2012). Analyst following, staggered boards, and managerial entrenchment. Journal of Banking and Finance, 36, 3091–3100.

Jiraporn, P., & Liu, Y. (2008). Capital structure, staggered boards, and firm value. Financial Analysts Journal, 64, 49–60.

Kalcheva, I., & Lins, K. (2007). International evidence on cash holdings and expected managerial agency problems. Review of Financial Studies, 20, 1087–1112.

Kyle, A. (1985). Continuous auctions and insider trading. Econometrica, 53, 1315–1335.

Lee, G., & Masulis, R. W. (2009). Seasoned equity offerings: Quality of accounting information and expected flotation costs. Journal of Financial Economics, 92(3), 443–469.

Lee, C. M., Myers, J., & Swaminathan, B. (1999). What is the intrinsic value of the Dow? Journal of Finance, 54(5), 1693–1741.

Ling, D., & Ryngaert, M. (1997). Valuation uncertainty, institutional involvement, and the underpricing of IPOs: The case of REITs. Journal of Financial Economics, 43(3), 433–456.

Lins, K., Servaes, H., & Tufano, P. (2010). What drives corporate liquidity? An international survey of cash holdings and lines of credit. Journal of Financial Economics, 98, 160–176.

Marchica, M., & Mura, R. (2010). Financial flexibility, investment ability, and firm value: Evidence from firms with spare debt capacity. Financial Management, 39(3), 1339–1365.

Ohlson, J., & Juettner-Nauroth, B. (2005). Expected EPS and EPS growth as determinants of value. Review of Accounting Studies, 10, 349–365.

Ooi, J., Wong, W., & Ong, S. (2012). Can Bank lines of credit protect REITs against a credit crisis. Real Estate Economics, 40(2), 285–316.

Ott, S., Riddiough, T., & Yi, H. (2005). Finance, investment, and investment performance: Evidence from the REIT sector. Real Estate Economics, 33(1), 203–235.

Riddick, L., & Whited, T. (2009). The corporate propensity to save. Journal of Finance, 64(4), 1729–1766.

Riddiough, T., & Steiner, E. (2020). Financial flexibility and manager-shareholder conflict. Real Estate Economics, 48(1), 200–239.

Riddiough, T., & Wu, Z. (2009). Financial constraints, liquidity management and investment. Real Estate Economics, 37(3), 447–481.

Stulz, R., & Johnson, H. (1985). An analysis of secured debt. Journal of Financial Economics, 14(4), 501–521.

Sufi, A. (2009). Bank lines of credit in corporate finance: An empirical analysis. Review of Financial Studies, 22(3), 1057–1088.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cashman, G.D., Harrison, D.M., Howton, S. et al. The Cost of Financial Flexibility: Information Opacity, Agency Conflicts and REIT at-the-Market (ATM) Equity Offerings. J Real Estate Finan Econ 66, 505–541 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-021-09821-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-021-09821-9

Keywords

- Financial flexibility

- At-the-market (ATM) equity offerings

- Cost of capital

- Agency problems

- Informational opacity