Abstract

This paper addresses the effects of a prohibition of providing non-audit services (NAS) to audit clients. By combining a strategic auditor–client game with a circular market-matching model that has an endogenous number of auditors, we take into account the interdependence between the auditors’ and clients’ incentives, the market structure, and the quality of audited reports. We show that the regulation’s effects depend on the preexisting audit market concentration and the types of blacklisted NAS. In sharp contrast to the effects that regulators desire, a prohibition of providing NAS to audit clients can further increase audit market concentration and decrease the quality of audited reports if the fees that auditors previously earned from providing the blacklisted NAS were relatively high, compared to the reduction in audit costs that result from spillovers. In contrast, a prohibition of the NAS that generate intense spillovers and low NAS fees can have the unexpected—but desired—effect of decreasing market concentration; however, reporting quality also decreases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Regulators around the world are increasingly concerned that the joint provision of audit services (AS) and non-audit services (NAS) could impair the quality of audited financial statements. The U.S. Congress, via the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002, has prohibited registered audit firms from providing public companies with any design or implementation services for financial information systems, internal AS, and “certain other services” (Title II, § 201 (g)). By contrast, SOX does not restrict the provision of audit-related or tax services.Footnote 1 However, SOX requires the registrants’ independent audit committee to approve any NAS allowed by law (Title II, § 202). Moreover, SOX demands the separate disclosure of audit fees and various types of NAS fees. Regulation 537/2014 of the European Union (EU) also contains a list of NAS that statutory auditors must not provide to their public interest entity audit clients (European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2014, Art. 5). The blacklist excludes from the prohibition expert services unrelated to the audit, a number of tax services, and other advisory services. However, Article 4 of the regulation limits the fees an audit firm earns from providing NAS to an audit client to 70% of the average fees earned in the last three consecutive financial years for carrying out the statutory audits for this client. In the United Kingdom (UK), the Competition and Markets Authority (2019) observes that audit firms provide NAS to their audit clients well below the 70% cap. Nevertheless, on July 6, 2020, the Financial Reporting Council (2020) asked the UK Big 4 audit firms to implement an operational split of their audit practices from the rest of the firm by June 30, 2024.

Apparently, the regulators and legislators acted on the assumption that the provision of certain types of NAS leads to a decrease in the quality of audited financial reports. The empirical evidence on the effects of the joint supply of AS and NAS, however, remains inconclusive (Beattie and Fearnley 2002; Schneider et al. 2006; Sharma 2014). Some researchers conclude that single-provider auditing and consulting does not negatively affect audit quality (Craswell et al. 2002; DeFond et al. 2002; Ashbaugh et al. 2003; Chung and Kallapur 2003; Geiger and Rama 2003; Raghunandan et al. 2003; Larcker and Richardson 2004; Reynolds et al. 2004; Agrawal and Chadha 2005; Hay et al. 2006a; Higgs and Skantz 2006; Ruddock et al. 2006; Stanley and DeZoort 2007; Callaghan et al. 2009; Li 2009; Hope and Langli 2010; Lim and Tan 2010). However, there is also evidence that the joint provision of AS and NAS is associated with lower (perceived) audit quality (Sharma and Sidhu 2001; Firth 2003; Krishnan et al. 2005; Fargher and Jiang 2008; Schmidt 2012; Blay and Geiger 2013; Gaver and Paterson 2014), an increase in earnings management (see the meta-analyses by Kanagaretnam et al. (2010) and Lin and Hwang (2010)), and lower financial reporting quality (Frankel et al. 2002; Ferguson et al. 2004; Gul et al. 2006; Srinidhi and Gul 2007; Habib 2012; Markelevich and Rosner 2013; Carcello et al. 2019).

We argue that there could be at least three reasons for these inconclusive empirical results. First, not all of the NAS provided are identical. Regulators are especially concerned about the NAS that generate relatively high additional fees and thus a strong economic bonding between the auditor and her client but weak knowledge spillovers and thus a negligible effect on the efficiency of the audit. Consequently, both empirical and analytical studies should consider these NAS characteristics. Second, the prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS has not only incentive effects but also—at least in the medium term—effects on the structure of the audit market. More precisely, the prohibition of single-provider auditing and consulting affects both the audit costs and the total fees that audit firms earn and, thus, the profit contributions that audit firms can realize. A change in the profit contributions can lead to an adjustment in the number of audit firms active in the market, which, in turn, can potentially influence audit quality. Thus, to more precisely predict the effects of a prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS, regulators and academics should consider not only audit firms’ preexisting market shares, but also potential changes in the market structure resulting from auditors’ decisions to enter or exit the market. Third, a regulation’s effect on incentives works immediately, whereas its effect on market structure needs time to unfold. In a setting in which both effects differentially affect the quality of audited reports, the period studied matters.

Recent empirical studies use models of spatial competition as a theoretical background to examine audit fees. The results stress the importance of accounting for auditors’ differentiation from their competitors. For example, Numan and Willekens (2012) find that audit fees increase both in the degree of auditor–client alignment and the size of audit firms’ industry market shares, compared to the market shares of their closest competitors. Chu et al. (2018) document that the audit fees paid to the incumbent audit firm decrease both in the client’s number of potentially efficient suppliers and in the relative size difference between the largest audit firm and the incumbent. Usually, the hypotheses tested in empirical studies are based on the Hotelling (1929) model (Numan and Willekens 2012; Bills and Stephens 2016; Keune et al. 2016; Boone et al. 2017). Empirical work building on this model’s location approach adds to the literature that has identified certain auditor characteristics as drivers of audit fees and quality by incorporating auditors’ competitive behavior and its effects on observable audit output measures (Francis 2004; Hay et al. 2006b; Hay 2013). However, since the number of homogeneous suppliers is fixed at a value of at most two, Hotelling’s bounded linear model is less suitable for deriving hypotheses regarding the effect of audit regulations on market structure. The circular market-matching model introduced by Schmalensee (1978) and Salop (1979), in contrast, allows the analysis of oligopolistic markets in which the number of suppliers is neither exogenous nor necessarily stable over time. As in the linear Hotelling approach, auditors’ expertise with regard to the client characteristics that are relevant during the production of AS can be used to model audit costs. Applying a circular instead of a linear model permits the endogenization of the number of auditors active in the market, which affects the auditors’ competitive positions and thus the average quality of audited reports.

To simultaneously analyze the effects of a prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS on both incentives and market structure, we embed a strategic auditor–client game into a circular market-matching model. In the auditor–client game, we model clients’ incentives to misreport their companies’ bad economic condition as well as auditors’ incentives to exert high effort to detect potential misreporting. In line with the argument put forward by the proponents of a prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS, we assume that an auditor who issues an adverse audit opinion on a client’s report loses this client’s future NAS fees. Since the opponents of such a prohibition often refer to desirable knowledge spillovers from NAS to AS, we assume that audit costs are lower if auditors provide both AS and NAS. Using the circular matching approach, we derive auditors’ expected costs for auditing specific clients and determine the audit fees by assuming Bertrand price competition. The zero-profit constraint leads to the equilibrium number of auditors active in the market, which then has an impact on auditors’ average expertise and, therefore, on the average quality of audited reports. We thus simultaneously determine audit costs, auditors’ profit contributions, the number of auditors, and the quality of audited reports both for the setting with and the setting without the joint provision of AS and NAS.

We show that the abolition of single-provider auditing and consulting can affect auditors’ and clients’ incentives as well as the number of auditors who are active in the market. We thus take on the conclusion, from the experimental study of Dopuch and King (1991, p. 89), that “policymakers who favor proposals to prohibit auditing firms from providing both MAS [management advisory services] and verification services to the same client should contemplate whether the prohibition will have an adverse effect on the market structure of the audit industry. Adverse effects on the structure of the industry could offset any benefits the change might have on auditor independence.”

Accounting for the effects on both incentives and market structure, we investigate whether a prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS has the overall positive effect on the quality of audited reports that the proponents of such regulation envisage.

Our results indicate that the prohibition of the NAS that regulators usually classify as harmful (i.e., NAS that are associated with high NAS fees, but with a low degree of spillovers from NAS to AS) has undesired effects on both audit market concentration and the quality of audited reports. In line with the proponents’ argument, the incentive effect of a prohibition of single-provider auditing and consulting leads to an increase in the quality of audited reports (i.e., to a decrease in the individual probability that clients will misreport a bad economic condition), but only if the number of auditors is considered constant. However, the elimination of the auditors’ opportunities to provide NAS in addition to AS decreases their profit contributions. Given predetermined auditor fixed costs and a degree of competition that is sufficient to enforce the zero-profit constraint, lower profit contributions decrease the equilibrium number of auditors. The resulting decrease in the average degree of auditor expertise can overcompensate for the regulation’s effect on incentives and tends to increase the average probability that clients will misreport. Thus, the prohibition of exactly the NAS about which regulators are most concerned increases market concentration and can decrease the quality of audited reports. In contrast, if apparently harmless NAS are prohibited (i.e., NAS that generate intense spillovers from NAS to AS, but cause only low NAS fees), our model predicts the desired decrease in market concentration, although with the disadvantage of a lower quality of audited reports. Thus, the effects of a prohibition of NAS with relatively high fees and of a prohibition of NAS with comparatively intense spillovers do not simply work in opposite directions. Moreover, our results indicate that the respective effects are more intense if the regulation is implemented in highly concentrated audit markets.

Our paper contributes in several ways. First, in combining a strategic auditor–client game with a circular market-matching model, we add to the analytical audit literature, because future research can use this approach to examine other audit market regulations. Second, we provide new arguments to the regulatory debate regarding the effect of a prohibition of different types of NAS. By analyzing the channels through which regulations can affect the quality of financial reports, we show that prohibiting exactly those NAS that regulators regard as harmful could have unintended consequences. Third, our model highlights the reasons why the empirical findings on the effects of a prohibition of single-provider auditing and consulting are inconclusive. More precisely, our results indicate that the preexisting market structure, the profitability of the blacklisted NAS, and the intensity of the knowledge spillovers from NAS to AS should be controlled for in empirical models that estimate the quality of audited financial statements. This argument is in line with the call of Gerakos and Syverson (2017) for empirical research in auditing to consider more often the techniques of the industrial organization literature.

This paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature on strategic auditor–client games and market-matching models in audit research as well as the analytical literature on the prohibition of the joint provision of AS and NAS. Section 3 presents our model on the relation between the structure of the audit market and the quality of audited financial statements. Section 4 provides the analysis of the optimal auditor and client decisions and the resulting quality of audited financial statements. Section 5 analyzes the effects of a prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS on the market structure and the quality of audited reports. Section 6 summarizes our main findings and derives conclusions regarding the advantageousness of regulations on single-provider auditing and consulting.

2 Related literature

We integrate a strategic game between an auditor and her client into a market-matching model. Thus, we combine two strands of the analytical literature.

First, our work is related to approaches that use a simultaneous non-cooperative game of two players (who have a finite number of pure strategies to choose from) to analyze problems inherent in financial reporting and auditing. Each player applies a randomization strategy that determines the Nash equilibrium in mixed strategies. The type of auditor–client game we use is well established in audit research and has been applied to a multitude of issues. For example, Magee (1980) addresses auditor independence, Fellingham and Newman (1985) and Anderson and Young (1988) focus on audit planning, Matsumura and Tucker (1995) and Tucker and Matsumura (1997) investigate second-partner reviews, and Smith et al. (2000) model the effects of internal control systems. Simultaneous auditor–client games have also been extended to examine more complex settings (Fellingham et al. 1989; Newman and Noel 1989; Patterson 1993; Bloomfield 1995; Newman et al. 2001; Patterson and Smith 2007; Patterson et al. 2019). The advantage of this type of game is that it highlights the players’ incentives and their equilibrium strategies; further, strategic auditor–client games frequently have unexpected results that deviate from those obtained from purely qualitative considerations.Footnote 2

Second, our research is linked to models of spatial competition. Hotelling (1929) proposes a static model in which two identical firms provide one homogeneous product. In a two-stage game, suppliers choose their locations in a bounded linear market. They then compete on prices for a product they sell to cost-minimizing consumers who incur linear transportation costs. Hotelling (1929) mainly addresses the Nash equilibrium in the price-setting stage of the game; thus, the application of the Hotelling (1929) model to the audit market is particularly useful for analyzing audit fees.

For example, Chan (1999) assumes that audit firms strategically decide on their specializations. For clients with audit-relevant characteristics that are in line with the auditor’s specialization, auditors have a cost advantage over their competitors. Chan (1999) shows that specialized audit firms obtain market power and offer specialization- and relationship-specific audit fees. Low-balling occurs only in market segments with sufficient competition. Chan et al. (2004) extend the work of Lederer and Hurter Jr. (1986) to analyze audit firms’ investment strategies to become specialists for clients with a multidimensional vector of characteristics. Chan et al. (2004) show that audit firms specialize in market niches to earn rents. While the audit firms’ locations in the bounded linear market represent their specializations in the clients’ audit-relevant characteristics in Chan’s (1999) model, in the model of Simons and Zein (2016) they indicate the quality that audit firms offer. Simons and Zein (2016) adapt the Hotelling (1929) model to show that the presence of mid-tier audit firms improves the average quality of audits in some settings but fails to do so in others.

Our paper examines the effects of audit regulations on incentives and the market structure. However, a linear and bounded market does not allow for modeling more than two identical audit firms or for endogenizing the number of competing auditors. In contrast, the circular market of Schmalensee’s (1978) and Salop’s (1979) models allows for the presence of more than two homogeneous suppliers; consequently, researchers can account for auditors’ potential market entries and exits. As in the Hotelling (1929) model, the distance between the consumer and the supplier determines the consumer’s transportation costs but not the supplier’s production costs. A simple “relabeling” of Salop’s (1979) model to apply it to an audit context would thus mean assuming that clients prefer specific auditors (i.e., that clients regard audits as a heterogeneous product), and that the auditors’ costs are identical for all clients. Since the latter assumption seems rather unrealistic, we extend Salop’s (1979) model by presuming that audit costs vary across an auditor’s client base, but that clients do not initially prefer certain auditors. We thus take into account differences in auditors’ specializations that, in turn, determine clients’ willingness to contract with specific auditors.

Bleibtreu and Stefani (2018) also use a circular market-matching model to examine the effects of audit market regulations (in this case, the mandatory rotation of audit firms) on the market structure. However, the authors do not explicitly derive the effect of the regulation on the quality of audited reports. Instead, they use the relative importance of a client (i.e., the relation between the profit contribution an auditor earns from a specific client to the auditor’s total profit contribution) as a proxy for auditor independence. In this paper, we combine a simultaneous game representing the strategic auditor–client interaction and a circular market-matching model that determines the equilibrium number of auditors. We explicitly analyze auditors’ decisions to exert high versus low audit effort and clients’ decisions to correctly or incorrectly report the economic condition of their company. Our approach thus allows the simultaneous examination of the effects of audit regulations on audit market concentration and the quality of audited reports.

One argument against the joint provision of AS and NAS is that the expected NAS fees increase auditors’ economic bonding. Thus, a common approach is to adapt quasi-rent models that are based on DeAngelo’s (1981) work (for extensions, see Magee and Tseng (1990), Kanodia and Mukherji (1994), Schatzberg (1994), Schatzberg and Sevcik (1994), Gigler and Penno (1995), Bagnoli et al. (2001), and Ronen and Ye (2019)). In this vein, Beck et al. (1988) describe the conditions that must be fulfilled for NAS to increase the client-specific quasi-rent. However, the relation between the client-specific quasi-rent and auditors’ total quasi-rents (as a proxy for auditor independence) is undetermined, because Beck et al. (1988) do not consider the effect of the regulation on the structure of the audit market.

Kornish and Levine (2004) and Beck and Wu (2006) examine audit quality but also do not address the market structure. Kornish and Levine (2004) use an agency model to examine the interactions of a self-interested and profit-maximizing auditor with two principals: the manager, who can demand NAS in addition to the audit, and shareholders, who prefer a truthful report. Kornish and Levine (2004) show that in a single-period setting, shareholders can counterbalance the manager’s negative influence on auditor independence by arranging contingent audit fees. In a multi-period setting, contingent auditor retention schemes mimic the effects of contingent fees. Focusing on the trade-off between audit fees and quality, Beck and Wu (2006) present a non-strategic dynamic Bayesian model to analyze audit quality, which is measured as the precision of the auditor’s posterior beliefs regarding client-specific characteristics. Their results indicate that high fees can lead auditors to provide NAS that increase the engagement risk and reduce audit quality.

The effects of the auditor’s scope of services on audit market concentration have been studied only infrequently. Wu (2006) presents a model in which knowledge spillovers from consulting to auditing or vice versa are always beneficial to auditors, but also provide economic links between the audit market and the market for NAS. Because auditors’ behavior in one of the markets affects their strategies in the other market (“competition crossover”), spillovers can result in aggressive competition. Based on a Cournot duopoly game in quantities, Wu (2006) analyzes the trade-off between these two economic forces. Although Wu (2006) focuses on competition, he does not explicitly model the effect of audit regulations on the market structure. In combining a strategic auditor–client game with a circular market-matching model, we highlight the relations between the scope of services that auditors are permitted to provide, their market shares, and the quality of their audits.

3 Auditor–client interaction and market-matching model

3.1 General model description

We integrate an auditor–client game, in which each of the two players has two strategies available, into a circular market-matching model. The auditor–client game captures the client’s and the auditor’s decision-making in preparing and auditing the client’s report. Even though the client prepares the report before the auditor makes her audit effort decision, we regard the decisions as made simultaneously, since the auditor cannot observe the client’s action choice before she conducts the audit. The solution to this game is a subgame-perfect Nash equilibrium in mixed strategies; that is, the client (the auditor) chooses the probability of correctly reporting the economic condition of the company (for exerting high audit effort) that makes the auditor (client) indifferent between her pure strategies.

In the matching model, the auditors’ expertise in auditing clients with specific characteristics and the expected audit costs determine the audit fees, the auditors’ profit contributions, and the auditor–client matching. We derive the audit fees under the assumption of Bertrand price competition between heterogeneous competitors. For their fee offers, auditors make rational conjectures regarding the equilibrium of the auditor–client game to assess their own and their competitors’ audit costs. We assume that all payoffs are certain, that players are risk neutral and perfectly rational, and that all players know about all of these assumptions. Thus, in equilibrium, auditors’ (and clients’) conjectures are fulfilled. We will show that it is always optimal for the client to choose the auditor offering the lowest fees, which is also the auditor with the highest expertise.

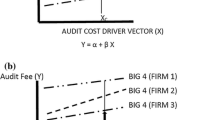

Figure 1 illustrates the chronological sequence of the auditors’ competition for clients and the auditor–client game. We first solve the auditor–client game, and then embed the players’ optimal decisions into the market-matching model. For simplicity, we restrict our analysis to a single period.

Chronological sequence of the matching model and the auditor–client game. This figure illustrates the chronological sequence of the auditors’ competition for clients (market-matching model) and the interaction between the auditor and the client after they have entered into an audit contract (auditor–client game). The auditor–client matching and the audit fees are determined in the market-matching model, where the auditors make rational conjectures about the equilibrium of the auditor–client game to derive their fee offers. In the auditor–client game, auditors and clients consider the audit fees as sunk

The zero-profit market equilibrium of the circular matching model determines the number of auditors active in the market (i.e., the market structure). The number of auditors, in turn, determines the average expertise of the auditors who are active in the market and thus the average quality of audited reports. Our combined model consequently allows for the simultaneous examination of the effects of regulations on incentives and market structure; our approach is valuable because these effects jointly determine the quality of audited reports.

3.2 Strategic auditor–client interaction

The auditor–client game reflects the strategic interaction during the process of preparing and auditing a company’s report. We thus consider the situation when a client and an auditor have already entered into an audit contract. Neither the auditor nor the client can terminate the audit contract before the auditor has issued an audit opinion. The audit fees are sunk and do not affect the auditor’s or the client’s decisions in the auditor–client game. Figure 2 illustrates the payoffs in the auditor–client game for a situation where the auditor is allowed to offer both AS and NAS and for a situation where the joint supply of AS and NAS is forbidden.

Decisions and payoffs in the auditor–client game. This figure illustrates the auditor’s and the client’s decisions and their (decision-relevant) payoffs. The term θ (1 − θ) is the exogenous probability that the client’s company is in a bad (good) economic condition. If the condition is good, the client always reports truthfully. If the condition is bad, the client misreports the condition (reports truthfully) with probability PrM (1 − PrM). If the client reports a bad condition, the auditor chooses low effort. If the client reports a good condition, the auditor chooses high (low) effort with probability PrH (1–PrH). Choosing high effort enables the auditor to discover the true condition. If the auditor detects misreporting, the auditor issues an adverse opinion; otherwise the auditor issues a clean opinion. The term v is the addressees’ rational beliefs about the value of the client’s company, given the report of a good condition and a clean audit opinion; in case of an adverse opinion or a client’s report of a bad condition, the addressees know that the value is zero. m denotes the client’s costs of misreporting. dM is the disutility the client suffers from an adverse opinion. For the adjusted client’s payoffs (see Sect. 3.2), the payoff given a clean opinion on a report of a good (bad) condition is zero (− dT) with m < dT < dM. c ∙ x is the auditor’s cost of exerting high effort, where c is a cost parameter and x is an inverse measure of the auditor’s expertise; the cost of exerting low effort is normalized to zero. l denotes the auditor’s litigation costs if the auditor issues a clean opinion on an incorrect report. For the case with NAS, s < c is the cost reduction that results from knowledge spillovers from NAS to AS. f < l is the auditor’s (expected future) fees from offering NAS to the audit client. The auditor cannot expect to receive these NAS fees if she issues an adverse opinion on the client’s report

Nature determines the economic condition of the client’s company. The condition is bad with the exogenous probability 0 < θ < 1 and good with probability 1 − θ; the intrinsic value of the company is normalized to zero (one) if the condition is bad (good). Before conducting the audit, the auditor only knows these probabilities and the firm value resulting in the good and bad condition. The client, after entering into an audit contract, gets to know the actually given economic condition (and thus the value of the company) with certainty. The addressees know about the client’s report and the auditor’s opinion, but not about the actual economic condition or the auditor’s effort choice.

The client has two strategies available: reporting truthfully or misreporting the economic condition of the company. We assume that the client does not have an incentive to underreport the economic condition and thus always truthfully reports a good condition. In case the client truthfully reports a good condition and the auditor issues a clean opinion on this report, the client’s payoff equals the addressees’ rational expectations about the company’s intrinsic value v (see formula (2) in Sect. 4 for the derivation of the expected value of the company).

If the condition is actually bad, the client decides whether to report truthfully or to misreport the bad condition as good (Amiram et al. 2018). If the client truthfully reports a bad condition, the auditor will issue a clean opinion after having provided low effort, because she knows that the client’s report is credible. The client’s payoff then is zero, because the addressees get to know the company’s bad condition.Footnote 3 If the client misreports the condition of the company and the auditor does not detect the misreporting, addressees still value the company with v. However, the client incurs misreporting costs of m < v that result from the effort of creating a misleading report and from the effort that is necessary to decrease the probability that an incorrect report will be detected. The misreporting costs also include expected monetary or reputational sanctions that will arise if the incorrect report is, by chance, detected in later periods (Ball 2009). If the client misreports the company’s bad condition as good, the client must additionally accept the risk that the auditor will detect the incorrect report and will refuse to issue a clean opinion. In this case, the addressees will recognize that the company’s true value is zero. Moreover, the detection of an incorrect report results in an additional decrease in the client’s payoff of dM. This decrease can arise from the violation of covenants that forbid the borrower from receiving a going-concern opinion (Menon and Williams 2016), from reputational consequences for the client, or from additional costs incurred in correcting the report.

In equilibrium, the client will choose the probability of misreporting the bad condition as good in a way that makes the auditor indifferent between choosing high and low effort. We denote this probability with PrM*. In Fig. 2, the line “client’s payoffs” summarizes the client’s payoffs in case the addressees rationally react to the observed combination of the client’s report and the auditor’s opinion.

For the auditor’s effort choice, we also consider two strategies. The auditor can exert high effort, which allows for the perfect observation of the actual economic condition of the company, irrespective of the client’s report. Exerting low effort, however, will leave the misstatements in the client’s report undetected. In this case, the auditor needs to issue a clean opinion on the client’s report because the auditor cannot provide evidence for a deviation between the true and the reported condition.Footnote 4 Exerting high (low) effort results in audit costs of c ∙ x (zero). c is a cost parameter and x is an inverse measure of the auditor’s expertise in auditing the client’s financial statements.Footnote 5

If the client reports a bad condition, the auditor issues a clean opinion without having to exert high effort because such a report is always credible. If the auditor observes a report of a good condition, the condition could be either good or bad. If the auditor can prove that the report is incorrect by exerting high effort, the auditor will issue an adverse opinion or force the client to correct the report.Footnote 6 If the condition is bad and the auditor exerts low effort, she cannot prove that the client has misreported and therefore has to issue a clean opinion. However, if it later turns out that the auditor confirmed an incorrect report of the client, the auditor incurs a deduction of l > c ∙ x from her payoff. This deduction results from legal action initiated by the recipients of the report (Anantharaman et al. 2016; Amoah et al. 2018) or from the loss of (potential) audit contracts with other clients due to a decrease in the auditor’s credibility (DeAngelo 1981).

To address the auditors’ possibility of offering NAS to their audit clients, we expand this basic audit setting by accounting for the main arguments of both the proponents and the opponents of a prohibition of single-provider auditing and consulting. Regulators and advocates of a prohibition frequently argue that the NAS fees earned from audit clients can lead to economic bonding and thus impair the auditor’s independence. To account for this concern, we assume that an auditor who issues an adverse opinion loses the expected future NAS fees f obtained from the respective audit client, because the client will stop buying NAS from that auditor.Footnote 7 Since the auditor can earn future NAS fees only if she issues a clean opinion, the expected future NAS fees f are decision-relevant.Footnote 8 However, we do not assume the extreme case in which an auditor is willing to issue a clean opinion against better knowledge to maintain or gain consulting contracts or in which clients demand NAS in exchange for a favorable audit opinion (Whisenant et al. 2003; Hay et al. 2006a; Srinidhi and Gul 2007; Basioudis et al. 2008). Thus, we assume f < l; that is, if the joint supply of AS and NAS is permitted, potential litigation costs are still sufficient to ensure that the auditor truthfully reports a finding of a bad condition. However, the possibility of earning NAS fees works against the litigation threat.

The opponents of a prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS frequently refer to cost-reducing knowledge spillovers from NAS to AS (Simunic 1984; Beck et al. 1988; Arruñada 1999). (For empirical evidence, see Krishnan and Yu (2011), Knechel and Sharma (2012), Knechel et al. (2012), and Svanström and Sundgren (2012).) We integrate spillover effects into our model by assuming that offering NAS to audit clients reduces the auditor’s costs for exerting high effort in the period considered to (c – s) ∙ x. The spillovers, s < c, thus become more important the lower the auditor’s expertise is (as x is an inverse measure of expertise). The reasoning behind this assumption is that auditors who are highly specialized in a certain client’s characteristics will not profit much from additionally providing NAS, whereas spillovers are quite valuable if the auditor has lesser expertise. In Fig. 2, the line “auditor’s payoffs without NAS” (“auditor’s payoffs with NAS”) summarizes the auditor’s payoffs in case she cannot (can) jointly offer AS and NAS.

In equilibrium, the auditor will choose high effort after having observed the client’s report of a good condition with a probability that makes the client indifferent between truthfully reporting and misreporting. We define this probability as PrH*.

One drawback of the assumption that the addressees rationally update their beliefs after having observed a clean audit opinion on the client’s report of a good economic condition is that PrH*(x) is indeterminate. To obtain a manageable solution for PrH, we adjust the client’s payoffs in the auditor–client game for our main analysis of the regulation (see the line “adjusted client’s payoffs” in Fig. 2). Instead of using the addressees’ beliefs about the company’s expected value v, we normalize to zero the payoff that the client receives if the auditor issues a clean opinion on a report of a good economic condition. However, if the client truthfully reports a bad economic condition, the client’s utility decreases by dT (with m < dT < dM).Footnote 9 Consequently, the main incentives resulting from the initially assumed client’s payoffs remain unchanged: the client prefers (1) a clean opinion on a misstated report over a truthful report of a bad economic condition, and (2) a truthful report of a bad economic condition over an adverse opinion on a misstated report.

3.3 Circular market-matching model

To model the competition between the auditors and to derive the auditor–client matching, we apply the circular market-matching model proposed by Schmalensee (1978) and Salop (1979) to the audit market. More precisely, we assume that all of the auditors’ potential clients are uniformly and continuously distributed on a unit circle. We normalize the mass of clients to one. The position of a client on the unit circle describes any characteristic that could affect the auditor’s work, such as the company’s accounting standards, complexity, corporate structure, industry diversification, number of business areas, and listing status.

We assume that the auditors i = 1, …, n (with n ≥ 2) are equidistantly distributed on the unit circle.Footnote 10 The distance x between an auditor and a client on the unit circle is an inverse measure of the auditor’s expertise in auditing this specific client. If a client and an auditor have identical locations on the unit circle (i.e., x = 0), the auditor’s expertise perfectly matches the client’s characteristics. The larger the distance x, the lower the degree of the auditor’s expertise in auditing a client with these characteristics. Figure 3 illustrates the structure of our circular market-matching model.

Auditors and clients on the unit circle. This figure depicts the locations on the unit circle of auditors i − 1, i, and i + 1, and illustrates the distance x from auditor i to one specific client. The distance x represents the expertise of auditor i in auditing this particular client with specific characteristics. For n auditors active in the market (n = 8 in Fig. 3), the distance from the client to the second-nearest auditor i − 1 is 1/n − x (1/8 − x in Fig. 3)

The costs for exerting high effort are c ∙ x, that is, a (linear) function of the distance x (Chan 1999; Bleibtreu and Stefani 2018).Footnote 11 The reason for this modeling choice is that auditors with lower expertise (i.e., larger x) should need more resources to conduct the audit. There is empirical evidence that specialists are more efficient at detecting errors in a client’s financial report (O’Keefe et al. 1994a; Hogan and Jeter 1999; Owhoso et al. 2002), at performing analytical procedures (Wright and Wright 1997), at assessing audit risk (Taylor 2000; Low 2004; Hammersley 2006), and at planning audits (Bedard and Wright 1994). Auditors with a high degree of expertise thus have a cost advantage over competitors with less expertise.

As the auditors differ in their client-specific expertise and thus in their audit costs, none of the clients (except the client located exactly at the distance x = 1/(2n))Footnote 12 are indifferent between the auditors. To be more precise, choosing the auditor at the shortest distance x maximizes the client’s ex ante expected payoff by affecting the addressees’ rational expectations about the company’s intrinsic value, v.Footnote 13 Moreover, clients do not have strategic incentives to choose an auditor with low expertise in order to avoid an adverse opinion on a manipulated report. Based on the concept of the Nash equilibrium in mixed strategies in the auditor–client game where an auditor’s probability of choosing high effort makes the client indifferent between misreporting and truthfully reporting a bad economic condition, we can state the following Lemma:

-

Lemma 1 When the economic condition of the client’s company turns out to be bad, the auditor’s expertise does not affect the expected payoff that the client realizes after having contracted with the auditor.

Consequently, it is optimal for the clients to choose the auditor offering the lowest audit fee, which, under the assumption of Bertrand price competition, is also the auditor with the highest expertise (Brown and Knechel 2016).Footnote 14 Each auditor acquires the contract with all of the clients that are closer to her than to other auditors. For a client located in between the two auditors i and i − 1, these two auditors undercut each other’s fee offers up to the point where one of them reaches her own expected audit costs as derived in the auditor–client game. An auditor’s profit contribution earned from auditing a specific client can thus be calculated by subtracting the auditor’s own audit costs from her nearest competitor’s costs.Footnote 15

4 Analysis and results

We start with the analysis of the auditor–client game and then embed the results into the market-matching model. We start with the model for single-provider auditing and consulting with rational beliefs of the addressees. We then simplify the client’s payoffs to obtain a probability of high audit effort that is independent of the auditor’s expertise. To analyze the effects of a prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS, we then set the NAS parameters f and s to zero.

If the client truthfully reports a bad economic condition, the auditor always chooses low effort. If the client reports a good condition, the auditor does not know the actual condition of the company prior to conducting the audit and has to decide whether to exert high or low effort. If the client does not choose to misreport with certainty, there is no Nash equilibrium in pure strategies. The probabilities PrM*(x) for the client and PrH*(x) for the auditor specify the subgame-perfect Nash equilibrium in mixed strategies.

The client’s individual probability to misreport isFootnote 16

With this probability, the auditor is indifferent between exerting high or low effort after having observed the client’s report of a good economic condition. The individual probability that a client will misreport increases in the distance x; the lower the degree of expertise the auditor has in auditing a client with specific characteristics, the more expensive high effort becomes. Thus, the client’s option of misreporting is more attractive when the auditor has less expertise.

The auditor’s probability PrH*(x) for exerting high effort after having observed a report of a good condition makes the client indifferent between truthfully reporting a bad condition and misreporting a bad condition as good. To derive this probability, we first need to calculate the addressees’ rational beliefs regarding the value of the company. Applying Bayes’ rule, the expected value of a company in the case of a report of a good condition and a clean audit opinion, v, can be calculated asFootnote 17

The probability PrH*(x) then solves the following indifference equationFootnote 18:

The auditor’s probability PrH*(x) for exerting high effort, which depends on the client’s payoff and the client’s misreporting probability PrM*(x), decreases in the distance x. However, the indirect effect of x on audit effort is less pronounced than the direct effect of x on the client’s individual probability of misreporting. We show, in the following, that the qualitative effects of the distance x on the auditor’s expected audit and litigation costs and the auditor’s expected future NAS fees—the main factors of interest in our model—do not change if the probability that the auditor will exert high effort is independent of x. This result allows us to assume a payoff structure for the client that leads to a probability PrH* that is independent of x (see the line “adjusted client’s payoffs” in Fig. 2), which makes our main analysis of the effects of a prohibition of providing NAS to audit clients more tractable.

To derive the audit costs and the auditors’ profit contributions using the market-matching model, we provisionally use a fixed number n of auditors who are active in the market. We consider two arbitrary auditors, i and i − 1, located next to each other on the unit circle, and an arbitrary client located in between the two auditors at distances 0 ≤ x ≤ 1/(2n) from auditor i and 1/n − x from auditor i − 1 (see Fig. 3). The client is located closer to auditor i than to auditor i − 1; auditor i thus has more expertise in the client’s characteristics than auditor i − 1 has.

Given the respective probabilities for manipulation and high audit effort, the direct audit costs the two auditors can ex ante expect from auditing the client are given by

and

The cost-decreasing effect of x through PrH*(x) can never override the effect of x on the costs for exerting high effort (c − s) ∙ x, which is additionally exacerbated by the client’s probability PrM*(x) of misreporting. Thus, the expected direct audit costs of the auditor with higher expertise are always lower than the expected direct audit costs of the auditor at the larger distance, 1/n − x. It is straightforward to see that the same result applies if PrH* is independent of x.

In addition to the expected direct audit costs, the litigation costs that the auditors expect ex ante must be considered:

and

The expected litigation costs become more severe as the distance x between the auditor and the client increases. The auditor with higher expertise thus has lower expected litigation costs than the auditor at a larger distance. Again, this result also holds if PrH* is independent of x.

If auditors are allowed to offer NAS to their audit clients, they take into account that they will earn future NAS fees if they do not issue an adverse opinion when competing for audit contracts. The ex ante expected future NAS fees for the auditors i and i − 1 are

and

Because the positive effect of x on PrM*(x) is larger than the negative effect of x on PrH*(x), the expected future NAS fees decrease in the auditor–client distance x. Thus, the auditor with higher expertise obtains higher expected future NAS fees than the auditor at a larger distance. To calculate the expected “net” audit costs, we subtract the expected future NAS fees from the direct audit and litigation costs. Auditor i’s expected audit costs, adjusted for the NAS fees, are

and those of auditor i − 1 are

The auditor’s expertise thus determines the expected audit costs and the expected future NAS fees. Apart from their locations on the unit circle, however, the auditors are perfectly homogeneous in our model. Thus, we do not consider different types of auditors (e.g., the Big 4/non-Big 4 dichotomy), and we do not assume that clients have any initial preferences for one specific auditor. We also do not consider the possibility that the clients’ audit-relevant characteristics are connected with the probability for the occurrence of a bad economic condition.Footnote 19

Moreover, in the case of a good economic condition, PrM*(x) decreases and PrH*(x) increases the expected value of the company v (see formula (2)) and thus the payoff a client expects. Therefore, the client’s ex ante expected payoff decreases in x, and clients will always hire the auditor with the largest expertise (who also always offers the lowest fee, given Bertrand competition between homogeneous competitors).

In line with the logic of the Bertrand competition described in Sect. 3, we can calculate the expected profit contribution the auditor earns from auditing a certain client by subtracting the expected audit costs (adjusted for the NAS fees) from the nearest competitor’s adjusted costsFootnote 20:

As the distance x increases the direct audit and litigation costs and decreases the expected NAS fees, it decreases the auditor’s expected profit contribution earned from auditing a specific client. The number n of auditors does not directly affect the audit and litigation costs or the expected NAS fees, but it decreases the closest competitor’s costs (adjusted for the NAS fees). Consequently, an increase in the number of auditors reduces the profit contribution an auditor earns from a single client.

We can generalize the results for a client at a specific distance x to all of the clients located within the distance 0 ≤ x ≤ 1/(2n) from an arbitrary auditor i in both directions of the unit circle. Assuming an arbitrary number n of auditors active in the market, we can compute the expected total profit contribution an auditor can realize by integration from zero to 1/(2n) and multiplication by two (to take into account the entire clientele on both sides of the unit circle)Footnote 21:

To assess the effects of audit regulations on the market structure, the effect of the number n of auditors on auditors’ total profit contributions is importantFootnote 22:

-

Lemma 2 The expected total profit contribution of an auditor decreases in the number n of auditors active in the market (i.e., \(\partial E\left[{PC}^{i}\right]/\partial n<0\)).

To assess the effect of audit market regulations on the quality of audited reports, we consider the probability Φ that the audited report of the client will accurately reflect the economic condition of the company:

The quality of audited reports is not identical across an auditor’s clientele: the larger the distance x, the higher the individual probability that the client will misreport and the lower the probability that the auditor will exert high effort. Consequently, the quality of audited reports decreases in the distance x. This result does not change if PrH* is independent of x. Our reasoning is in line with the empirical result that auditors who specialize in their client’s industry produce higher-quality financial reporting. More precisely, the financial reports of companies audited by experts have higher earnings quality (Balsam et al. 2003; Krishnan 2003; Kwon et al. 2007; Gul et al. 2009; Lim and Tan 2010; Reichelt and Wang 2010; Christensen et al. 2015) and reflect bad news in a more timely fashion (Krishnan 2005). Furthermore, investors perceive these reports as more reliable (Dunn and Mayhew 2004; Krishnan 2005; Knechel et al. 2007; Kwon et al. 2007).

Lemma 3 and Corollary 1 follow from the fact that the auditor’s average expertise depends on the number n of auditors. For the continuous client space, the average probability that clients will misrepresent a bad economic condition is defined as

-

Lemma 3 The average probability that clients will misrepresent a bad economic condition decreases in the number n of auditors who are active in the market (i.e., \(\partial \overline{{{Pr }_{M}}^{*}}/\partial n<0\)).

Figure 4 illustrates this effect.

The probability that clients will misrepresent a bad economic condition, given a comparatively low number n of auditors (upper panel) and a relatively high number n’ > n of auditors (lower panel). The horizontal axis depicts the section of the unit circle on which the clients are uniformly distributed, and i–1, i, and i + 1 denote competing auditors. The figure illustrates the individual probability PrM*(x) that the client of auditor i located at distance x misreports the company’s condition. The dotted horizontal lines depict the average probability \(\overline{{{Pr }_{M}}^{*}}\left|{}_{n}\right.\) \(\left(\overline{{{Pr }_{M}}^{*}}\left|{}_{{n}^{^{\prime}}>n}\right.\right)\) that clients will misreport for a comparatively low (high) number of auditors n (n’ > n). The shift from the positions on the unit circle of auditors i–1 and i + 1 in the lower panel results from the relation n’ > n and the auditors’ equidistant distribution on the unit circle. A comparison of the upper and lower panels illustrates the effect of a change in audit market structure (i.e., the number of competing auditors) on the clients’ average probability of misreporting

Analogously to the average probability of misreporting, the average quality of audited reports can be calculated to

-

Corollary 1 The average quality of audited reports increases in the number n of auditors who are active in the market (i.e., \(\partial \overline{\Phi }/\partial n>0\)).

Directly following from formula (10) and \(\partial {{Pr}_{H}}^{*}\left(x\right)/\partial{{Pr}_{M}}^{*}\left(x\right)<0\), Corollary 1 is true irrespective of whether PrH* depends on x. Our model thus predicts a negative effect of audit market concentration, as measured by auditors’ market shares, 1/n, on the average quality of audited reports, even though n does not directly affect the auditors’ competitive pricing behavior. The reason for the predicted negative association is not that auditors skimp on effort because they expect their dominant market positions to protect them from punishment (“too big or too few to fail”; see Marriage et al. (2018)), but that clients exploit the fact that exerting high effort is, on average, more costly for auditors in concentrated markets than in markets with many highly specialized auditors. Our results thus correspond to those of Bandyopadhyay and Kao (2001), Boone et al. (2012), and Huang et al. (2016), who find that audit market concentration has negative consequences for audit quality.Footnote 23 Our findings are also in line with empirical studies that show that more equally distributed market shares are associated with higher-quality audits (Dunn et al. 2013; Francis et al. 2013) and that a high degree of relative concentration lowers audit quality (Boone et al. 2012). Applied to real-world audit markets, financial reporting quality should thus be highest if an auditor’s clientele is homogeneous with regard to the audit-relevant characteristics for which the auditor has perfect expertise. Currently, the Big 4 clearly dominate the market for providing AS to listed clients. Although the Big 4 might be able to efficiently audit clients with a broad range of characteristics, they arguably cannot be highly specialized in their entire clientele. Thus, in line with the regulators’ goal of increasing the competitiveness of mid-tier audit firms, our model predicts financial reporting quality to be higher if more mid-tier or small audit firms are active in the market, provided they are highly specialized in auditing clients with certain characteristics.

To derive the equilibrium number n* of auditors who are active in the market, we assume that the auditors incur fixed costs, cF, in addition to their expected audit and litigation costs. An auditor’s expected total profit can be calculated by subtracting the fixed costs from the expected total profit contribution. If auditors earn positive profits, then new suppliers will enter the market. If, in contrast, total profits are negative, then some of the auditors will leave the market. The equilibrium number n* of auditors solves the zero-profit condition

5 Effects of a prohibition of single-provider auditing and consulting

5.1 Analysis of the individual probability that a client will misreport a bad economic condition as good

We define

with positive values for the NAS parameters f and s as the manager’s equilibrium probability to misreport a bad condition as good for the case with NAS (i.e., formula (1)). For the case without NAS, the equilibrium probability is given by

(i.e., formula (1) with f = s = 0). Because

the individual probability that clients will misreport their company’s condition is higher in a setting in which the joint supply of AS and NAS is possible than in a setting in which it is prohibited if the NAS fees f are relatively high (in comparison to the litigation costs l) and the cost-reducing effect of spillovers is relatively low (in comparison to the cost parameter c). The opposite is true for the case with relatively low NAS fees and intense spillovers. Thus, our model considers the arguments of both the advocates and the opponents of a prohibition of single-provider auditing and consulting: the NAS fees leading to economic bonding (the cost-reducing spillovers) have an undesired (desired) positive (negative) effect on the probability that an individual client will misreport.

5.2 Analysis of a prohibition of NAS connected to relatively high NAS fees

We first focus on the effects of a prohibition of NAS that generate relatively high fees for the auditor (i.e., the case f/l > s/c). Regulators usually regard these NAS as having the potential to impair audit quality because of economic bonding. The effect of providing NAS with relatively high fees on clients’ incentives supports this view: the individual probability that a client will misreport is higher if auditors are allowed to jointly offer AS and NAS (see formula (15)). Consequently, for a constant number of auditors, the average misreporting probability is also higher if offering NAS to audit clients is permitted. Thus, considering the effect of a prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS only on incentives leads to the (premature) conclusion that this regulation has the desired effect of increasing the quality of audited reports.

However, this conclusion neglects the regulation’s effect on market structure. A prohibition of NAS with the attribute f/l > s/c leads to a decrease in auditors’ total profit contributions. If the number of auditors nNAS* in a setting with the joint provision of AS and NAS fulfills the zero-profit condition, \(E\left[{PC}^{NASi}\left({n}^{NAS*}\right)\right]-{c}_{F}=0\), then the number of auditors nnoNAS* in a setting in which single-provider auditing and consulting is prohibited adjusts downwards (i.e., nnoNAS* < nNAS*) to fulfill the condition \(E\left[{PC}^{noNASi}\left({n}^{noNAS*}\right)\right]-{c}_{F}\ge 0\).Footnote 24 This result is due to the fact that the total profit contribution decreases in the number of auditors (Lemma 2). Empirical evidence indicates that regulations indeed can have a negative effect on the number of auditors who are active in the market (DeFond and Lennox 2011; Fargher et al. 2018).Footnote 25

Moreover, the regulation’s effect resulting from changes in the market structure works in the opposite direction to its effect resulting from changes in incentives: a decrease in the equilibrium number of auditors due to the prohibition of single-provider auditing and consulting increases the average misreporting probability (Lemma 3). The regulation’s effect via the market structure can override that caused by incentives and even lead to a higher average misreporting probability if NAS with the attribute f/l > s/c are put on the blacklist.

-

Proposition 1 A prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS with relatively high NAS fees and weak spillovers (i.e., f/l > s/c) has the following effects:

-

(i)

The individual probability that a client will misreport a bad economic condition as good decreases (i.e., \({{Pr}_{M}^{NAS}}^{*}\left(x\right)>{{Pr}_{M}^{noNAS}}^{*}\left(x\right)\); effect resulting directly from changed incentives).

-

(ii)

The number of auditors active in the market decreases (i.e., nNAS* > nnoNAS*; effect on market structure).

-

(iii)

The average probability that clients will misreport a bad economic condition as good increases [decreases (slightly)] (i.e., \(\overline{{{Pr }_{M}^{NAS}}^{*}}<\overline{{{Pr }_{M}^{noNAS}}^{*}\left(x\right)}\) [\(\overline{{{Pr }_{M}^{NAS}}^{*}}>\overline{{{Pr }_{M}^{noNAS}}^{*}\left(x\right)}\)]) if the concentration in an audit market where auditors can jointly supply AS and NAS is relatively high [low] (i.e., if nNAS* is relatively low [high]).

Figure 5 illustrates these effects with a numerical example.

Individual and average probabilities that clients will misreport a bad economic condition, with and without the joint provision of AS and NAS, given relatively high NAS fees (i.e., f/l > s/c). The upper panel shows the individual probability that a client at distance x from the auditor will misreport a bad economic condition. The solid line depicts the probability for the case in which auditors are allowed to offer NAS to their audit clients (i.e., \({{Pr}_{M}^{NAS}}^{*}\left(x\right)\)); the dashed line stands for the case without the joint supply of AS and NAS (i.e., \({{Pr}_{M}^{noNAS}}^{*}\left(x\right)\)). Thus, the upper panel illustrates the regulation’s effect resulting from incentives. The lower panel shows the average probability that clients will misreport a bad economic condition and the adjustment in the number of auditors due to the regulation (i.e., the decrease from nNAS* to nnoNAS*). The figure shows that the regulation’s effect resulting from changes in the market structure can override the regulation’s effect resulting from incentives: the average probability of misreporting is lower when auditors are allowed to offer NAS to their audit clients (dots, \(\overline{{{Pr }_{M}^{NAS}}^{*}}\left|{}_{f/l>s/c}\right.\)) than when they are not (triangles, \(\overline{{{Pr }_{M}^{noNAS}}^{*}}\)) if the initial audit market concentration is not very low. We use the following parameter values to construct this figure: θ = 0.5, c = 1, l = 10, s = 0.1, and f = 2. Thus, f/l > s/c holds

The effect on the quality of audited reports follows directly from Proposition 1.

-

Corollary 2 A prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS with relatively high NAS fees and weak spillovers (i.e., f/l > s/c) leads to a decrease [(slight) increase] in the quality of audited reports (i.e., \(\overline{{\Phi }^{NAS}}>\overline{{\Phi }^{noNAS}}\) [\(\overline{{\Phi }^{NAS}}<\overline{{\Phi }^{noNAS}}\)]) if the market concentration before the implementation of the regulation is relatively high [low] (i.e., nNAS* is relatively low [high]).

Thus, even though the regulation’s effect on incentives leads to a decrease in the clients’ individual misreporting probabilities and thus tends to move towards the desired effect of an increase in financial reporting quality, the regulation’s effect resulting from changes in the market structure can override that resulting from changed incentives. If regulators prohibit the NAS that enable the auditor to earn high NAS fees in a situation in which the audit market is highly concentrated, we predict an increase in the average misreporting probability and a decrease in the quality of audited reports. This undesired outcome is highly likely, since nearly all national audit markets worldwide are highly concentrated (United States General Accounting Office 2003, 2008; Public Company Accounting Oversight Board 2005; Ewert and London Economics 2006; Ballas and Fafaliou 2008; Le Vourc’h and Morand 2011; Francis et al. 2013; Competition and Markets Authority 2019; Willekens et al. 2019). Moreover, the effect of the regulation is most severe in highly concentrated markets, but it is very marginal in a market with many suppliers. Our prediction contradicts the view of regulators and proponents of a prohibition of especially this kind of NAS (European Commission 2010, 2011a, 2011b). The regulation to cap the NAS fees earned by auditors of public interest entities at 70% of the average audit fees over the last three consecutive financial years, as recently implemented within the EU (European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2014), could have similar unintended effects.

5.3 Analysis of a prohibition of NAS that lead to relatively intense spillovers from NAS to AS

NAS with relatively intense spillovers and low fees (i.e., f/l < s/c) are usually regarded as harmless or even as quality-increasing. Examples of this type of NAS are tax services and audit-related NAS,Footnote 26 which are currently not part of the blacklist defined by SOX or Regulation 537/2014 of the EU. Again, the effect that prohibiting this kind of NAS has on incentives supports the regulator’s perception: the individual misreporting probability is lower if auditors are allowed to jointly offer AS and NAS that generate intense spillovers (see formula (15)). For a constant number of auditors, the average misreporting probability is also lower if auditors offer this kind of NAS to audit clients. Thus, considering only the effect directly caused by altered incentives leads to the conclusion that a prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS with spillovers that have a strong effect on audit costs has the unintended effect of decreasing the quality of audited reports.

However, this conclusion again neglects the regulation’s effect on the market structure. A prohibition of the NAS with the attribute f/l < s/c leads to an increase in auditors’ total profit contributions. Because total profit contributions decrease in the number of auditors (Lemma 2), the prohibition of single-provider auditing and consulting tends to increase the equilibrium number of auditors. However, under the premise that the number of auditors nNAS* in the scenario with the joint provision of AS and NAS fulfills the zero-profit condition, \(E\left[{PC}^{NASi}\left({n}^{NAS*}\right)\right]-{c}_{F}=0\), a prohibition of single-provider auditing and consulting does not necessarily lead to an increase in the number of auditors. More precisely, if the zero-profit condition holds, then \(E\left[{PC}^{NASi}\left({n}^{NAS*}+1\right)\right]-{c}_{F}<0\) can still be true (nnoNAS* is not strictly larger than nNAS*, i.e., nNAS* ≤ nnoNAS*). This result particularly occurs in a setting in which the concentration in the audit market before the regulation’s implementation is high. Our prediction is in line with empirical evidence showing that the market share mobility (Willekens et al. 2019) and auditor switching rates (UK Competition and Markets Authority 2019) have slightly increased after the implementation of audit market regulations. However, the auditor switches occurred almost entirely between the Big 4 audit firms. As a result, the implementation of the EU Audit Reform increased the combined market share of the non-Big 4 audit firms in the 28 EU Member States by only about 1.4% (Willekens et al. 2019). The UK House of Commons (2018) also observed that concentration seems to be resistant to regulatory action (in this case, to the requirement to put the statutory audit out to tender at least once every 10 years).

The regulation’s effect on the market structure works in the opposite direction to that via direct incentives only if the initial concentration is low (i.e., if nNAS* is relatively high). However, in this case, the regulation’s effect resulting from changes in the market structure is only weak (one additional auditor does not make much of a difference if many auditors are already active in the market). The regulation’s effect via the market structure dampens that via incentives, but does not override it.

-

Proposition 2 A prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS with relatively intense spillovers and low NAS fees (i.e., f/l < s/c) has the following effects:

-

(i)

The individual probability that a client will misreport a bad economic condition as good increases (i.e., \({{Pr}_{M}^{NAS}}^{*}\left(x\right)<{Pr}_{M}^{noNAS*}\left(x\right)\); effect resulting directly from changed incentives).

-

(ii)

The number of auditors active in the market remains constant or increases (i.e., nNAS* ≤ nnoNAS*; effect on market structure).

-

(iii)

The average probability that the client will misreport a bad economic condition as good increases (i.e., \(\overline{{{Pr }_{M}^{NAS}}^{*}}<\overline{{{Pr }_{M}^{noNAS}}^{*}}\)).

Figure 6 illustrates these effects with a numerical example.

Individual and average probabilities that clients will misreport a bad economic condition, with and without the joint provision of AS and NAS, given relatively intense spillovers (i.e., f/l < s/c). The upper panel shows the individual probability that a client at distance x from the auditor will misreport a bad economic condition. The solid line depicts the probability for the case in which auditors are allowed to offer NAS to their audit clients (i.e., \({{Pr}_{M}^{NAS}}^{*}\left(x\right)\)); the dashed line stands for the case without the joint supply of AS and NAS (i.e., \({{Pr}_{M}^{noNAS}}^{*}\left(x\right)\)). Thus, the upper panel illustrates the regulation’s effect resulting from incentives. The lower panel shows the average probability that clients will misreport a bad economic condition and the adjustment in the number of auditors due to the regulation (i.e., a potential increase from nNAS* to nnoNAS*). The figure shows that the regulation’s effect resulting from changes in the market structure can only dampen its effect resulting from incentives: the average probability of misreporting is lower when auditors are allowed to offer NAS to their audit clients (dots, \(\overline{{{Pr }_{M}^{NAS}}^{*}}\left|{}_{f/l<s/c}\right.\)) than when they are not (triangles, \(\overline{{{Pr }_{M}^{noNAS}}^{*}}\)). We use the following parameter values to construct this figure: θ = 0.5, c = 1, l = 10, s = 0.4, and f = 1. Thus, f/l < s/c holds

Again, the effect on the quality of audited reports directly follows from Proposition 2.

-

Corollary 3 A prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS with relatively intense spillovers and low NAS fees (i.e., f/l < s/c) leads to a decrease in the quality of audited reports (i.e., \(\overline{{\Phi }^{NAS}}>\overline{{\Phi }^{noNAS}}\)).

The regulation’s effect resulting from altered incentives leads to an increase in the individual misreporting probability. However, a prohibition of NAS with the attribute f/l < s/c can decrease audit market concentration, which has a counterbalancing effect on the quality of audited reports. Thus, our model predicts that a prohibition of NAS with intense spillovers can actually decrease audit market concentration, but only if the concentration is already low before the regulation’s implementation. However, as an unintended side effect, we predict a decrease in the quality of audited reports.

5.4 Discussion of the case with rational addressees

For the model with adjusted client’s payoffs, the average probability that the auditor will exert high effort, PrH*, does not vary across the three different regimes (without NAS, with NAS that generate comparably high fees, and with NAS that strongly reduce audit costs). The adjustment of the client’s payoffs does not affect the general structure of our model and facilitates the analysis of the main effects of the regulation. However, as PrH*(x) in the reference model with rational addressees depends on the distance x via the effect of x on PrM*(x), we can draw additional conclusions from our analysis.

First, for the reference model with rational addressees, the regulation’s effect on the average quality of audited reports is qualitatively identical to that in the adjusted model (since \(\partial \left[{{Pr}_{M}}^{*}\left(x\right)\cdot \left(1-{{Pr}_{H}}^{*}\left(x\right)\right)\right]/\partial x>0\)). However, the effect is more pronounced (since not only PrM*(x) but also (1 − PrH*(x)) increases in the distance x). The adjusted model thus rather underestimates the effect of the regulation on the average quality of audited reports.

Second, we can assess the effect of the respective regimes on the empirically measurable probability for the issuance of adverse audit opinions (i.e., \(\theta \cdot \overline{{{Pr }_{M}}^{*}}\cdot \overline{{{Pr }_{H}}^{*}}\)). Since the effect of x on PrM*(x) always overrides that on PrH*(x) (i.e., \(\partial \left[{{Pr}_{M}}^{*}\left(x\right)\cdot {{Pr}_{H}}^{*}\left(x\right)\right]/\partial x>0\)), a prohibition of NAS with relatively high fees (intense spillovers) tends to increase (decrease) the probability of the issuance of adverse audit opinions.

Third, in addition to the quality of audited financial statements, we can use the intrinsic value that rational addressees expect after having observed a clean audit opinion on a client’s report of a good economic condition as a social surplus criterion.Footnote 27 Doing so seems reasonable, given that the regulator sees the audit as a means of reducing the information asymmetry between the company and the addressees. The expected intrinsic value v decreases in \({{Pr}_{M}}^{*}\left(x\right)\cdot \left(1-{{Pr}_{H}}^{*}\left(x\right)\right)\); that is, it increases in the quality of audited reports, \(\Phi \left(x\right)=1-\theta \cdot {{Pr}_{M}}^{*}\left(x\right)\cdot \left(1-{{Pr}_{H}}^{*}\left(x\right)\right)\). If the audited report becomes more reliable, the addressees expect a higher intrinsic value if a company receives a clean audit opinion on a report of a good economic condition. This result is summarized in the following corollary.

-

Corollary 4 A prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS

-

(i)

with relatively high NAS fees and weak spillovers (i.e., f/l > s/c) leads to a decrease [(slight) increase] in the intrinsic value v of the company that addressees expect after having observed a clean audit opinion on a client’s report of a good economic condition if the market concentration before the regulation’s implementation is relatively high [low] (i.e., if nNAS* is relatively low [high]).

-

(ii)

with relatively intense spillovers and low NAS fees (i.e., f/l < s/c) leads to a decrease in the intrinsic value v of the company that addressees expect after having observed a clean audit opinion on a client’s report of a good economic condition.

Thus, given the currently high degree of audit market concentration, a regulation prohibiting an auditor from offering NAS to her audit clients seems to harm external addressees. This result holds irrespective of which type of NAS is put on the blacklist.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we combine a strategic auditor–client game with a circular market-matching model. In the strategic game, the client chooses between truthfully reporting the company’s bad economic condition and misreporting the bad condition as good. After having observed the client’s report of a good condition, the auditor chooses between low or high audit effort. Whereas high effort enables the auditor to perfectly observe the actual condition, low effort leaves deviations between the client’s report and the actual condition undetected. We embed the Nash equilibrium in mixed strategies for this game into a circular market-matching model in which we use the auditor–client distance on the unit circle as an inverse measure of the auditor’s expertise in auditing this specific client. The assumption that the auditors’ costs for exerting high effort depend on the auditor–client distance provides the link between the strategic game and the market model. The market model then determines the audit fees, the auditors’ profit contributions, and—given fixed costs—the equilibrium number of auditors active in the market. We thus add to the analytical audit literature by proposing a two-stage setup that allows for the analysis of the effects of a regulation both on incentives and market structure, which simultaneously impact the quality of audited reports.

We use this combined model to examine the effects of a prohibition of the joint supply of AS and different types of NAS. We assume that the auditor can earn future NAS fees only if she issues a clean opinion in the current period; we thus take into account the argument that the joint provision of AS and NAS increases the auditor’s economic bonding. We also consider the argument that the provision of NAS creates favorable knowledge spillovers that decrease the auditor’s costs for exerting high effort. The effect of a prohibition of the joint supply of NAS and AS depends on the relative importance of the NAS fees and the spillover effects, or, put differently, on the type of NAS on the blacklist.

Our results indicate that a ban on the NAS that regulators see as especially harmful, that is, NAS with comparatively high fees and weak knowledge spillovers, can have unintended effects. In particular, the loss of the economically important NAS fees decreases the auditors’ profit contributions and thus reduces the equilibrium number of auditors active in the market. If the market before the prohibition of single-provider auditing and consulting already is highly concentrated, this regulation also has an adverse effect on the quality of audited reports, since the average probability that clients will misreport increases. The predicted effects—both on the structure of the audit market and on the quality of audited reports—are diametrically opposed to the aims that the regulators envisaged in designing rules that restrict the scope of services that auditors are permitted to supply to their audit clients.

For the prohibition of the joint supply of AS and NAS with intense spillovers and low NAS fees, that is, the NAS that regulators frequently regard as harmless or even as advantageous, our model indicates that the equilibrium number of auditors can increase (if the market concentration before the regulation is rather low), but can also remain constant. However, since the regulation’s effect on market structure can dampen the effects resulting from the changed incentives but not completely offset them, the regulation has an unintended overall negative effect on the quality of audited reports.