Abstract

The aim of auditing is to protect active and potential investors from accounting fraud. Nevertheless, as many auditing scandals have demonstrated, auditing has a dark side. Correct auditing is a public good provided by private auditing firms, but these firms are paid by the enterprise being audited. Therefore, audit firms may be dubbed as agents of two principals, the audited firm and the public. Reputation theory conjectures that auditors are disincentivized from performing shallow and fraudulent auditing because of reputational concerns and associated reputational costs. However, empirical evidence does not support this claim. While it may be irrational for a large audit firm (such as Arthur Andersen LLP) to sacrifice its reputational capital for a single client by doing superficial audits (such as WorldCom), it may be quite rational for the auditing firm’s engagement partners to do so. The result might be a conspiracy against the public and investors. Because of an inelastic supply of experienced auditors and a highly concentrated market of big auditing firms, reputational losses due to auditing scandals for the audit firms’ local partners and staff seem to be rather small. With a game theoretic model, we argue here that neither higher transparency nor higher fines for auditing failures may prevent such conspiracies. Therefore, legal regulations and court rulings can only change the expected fines for audit fraud, but they cannot solve the general problems arising from the symbiotic relationship between auditors and their client firms. As auditing firms may use the so-called expectation gap to protect themselves against legal claims of wrongdoing, avenues more suitable to deterring conspiracies by auditors and their client firms might include whistleblowing, short-selling investors and investigative journalism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction and literature review

A significant problem in the accounting industry is the scope of accounting scandals. Accounting scandals are common and tend to involve audit firms in which local auditors either cannot prevent fraud or even help their client firms execute the fraud. However, reputation theory claims that this should not happen; this theory suggests that a large audit firm (such as Arthur Andersen LLP) would find it irrational to sacrifice its reputational capital for a single client. The fundamental idea is that bad auditing quality, e.g., by misreporting or helping with fraud, will likely be uncovered in a way that damages the auditing firm’s reputation, implying the loss of future business. The importance of reputation in the audit industry is not questioned, even via recent regulatory attempts like EU (Regulation No 537/2014) and German regulations (for instance, the Public Accountant Act, WPO, 2021). While these regulations have made minor changes to oversight, rotation, liability, fines and sanctions of auditors, they have not significantly altered the rules of the audit game. For example, one of the most recent German regulations, which followed the major Wirecard accounting scandal, is the Financial Market Integrity Strengthening Act (Finanzmarktintegritätsstärkungsgesetz, FISG, 2021); while this regulation has increased the auditor’s liability for grossly negligent performance of duties (liability limits are discussed below), the basic assumption remaining in the new law is that the industry will deliver good audit quality if left to self-regulation.

Through our study, it becomes clear that the empirical content of reputation theory depends empirically on several preconditions. Here, we check the applicability of reputation theory in the case of audit firms and auditors by analyzing the determinants of the benefits and costs of reputation. This paper contributes to the theory by reconceptualizing reputation theory in an auditing context. It also reconciles the interaction between auditors and their customers in a game theoretical setting. In this new setting, stylized facts of audit scandals can be better (re)interpreted than when using established model structures. This new setting is also used to analyze some of the initiatives and ideas for fraud prevention. The paper also contributes to the use of a cooperative solution in a non-cooperative game in the context of auditing.

Usually, reputation theory is applied by modeling the interaction between an audit firm, which can build up and also lose its reputation, and a client firm. Yet, when a common diagnosis of audit scandals hints at misaligned incentives, one must ask about the level at which the incentives work most strongly: at the partner level of the audit firm and the client firm or at the level of the firm? Although the usual reputation model setting describes firms interact with firms, one can instead focus on the interaction between managers of the client firm and individual auditors of the audit firm. This focus is in line with the recommendation given by Ye (2021) in a review of analytical papers on the economics of auditing, where the author diagnoses that most models fail to capture the “actual practice” in auditing firms (Ye, 2021, p.72).

Thus, our setting with the audit firm’s local auditors and the client firm’s managers better describes who does business with whom in the context of fraudulent behavior. Given that audit firms interact with client firms in fraudulent activities, ensuing reputational penalties after the fraud is detected are expected in reputational theory. But when individual auditors interact with individual managers in fraudulent activities, both can impose costs on investors (Doxey et al., 2021), that is, on parties other than those they do business with. Specifically, while the auditor harms the reputation of the audit firm, the manager of the client firm decreases shareholder and stakeholder value. When the interaction between managers and (local, individual) auditors is the relevant interaction to be studied, as we show, the outcome is different from that of an interaction between client firms and audit firms. This has a tremendous effect on the applicability and appropriateness of the concept of reputation. Thus, for example, while it may be irrational for a large audit firm (such as Arthur Andersen LLP) to sacrifice its reputational capital for a single client (such as WorldCom), it may be quite rational for the individual partners of the audit firm to do so (Macey, 2004; Painter, 2004; Ribstein, 2004). It has been shown empirically that audit fraud occurs independent of the reputation of the audit firm (Gerrety & Lehn, 1997). Moreover, the auditing performance of Arthur Anderson, measured by the frequency of financial restatements, also did not differ significantly from the performance of other big auditing firms (Eisenberg & Macey, 2004).

Our setting of client firm managers interacting with local auditors (in short: auditors) resembles business interactions and their effects on third parties. While the auditor acts as the agent for the manager of a client firm, she may do harm to the shareholders of this firm at the same time, which can be considered a third party to the relationship. This setting has much in common with environmental externalities (Karpoff et al., 2005) that differ from fraud and other types of wrongdoing in that they impose costs on parties other than those with whom the polluting firm does business. This means here that auditors do not do business with investors but, nevertheless, misreporting does hurt them. Empirically, in the case of environmental externalities, the reputational penalties are seemingly small compared to prospective legal penalties. In that context, share value losses usually only reflect legal penalties (see, for instance, the so-called Diesel scandal in the automobile industry).

A good case in point is the infamous German Wirecard scandal. The audit firm EY claimed that the Wirecard management was successful in deceiving the auditors, who had no chance of seeing through the fraud. Yet, the KPMG special auditor for Wirecard, Mr. Geschonneck, held an entirely different view. The official parliamentary committee report (Deutscher Bundestag, 2021 p. 335) stated:

At the beginning, Mr. Geschonneck explained the audit standards applied in the investigation: In determining and analyzing the facts, we used the audit standards of the Institute of German Auditors, IDW, as a benchmark. Our investigative and auditing activities essentially consisted of process recordings, document and data analyses, interviews with the persons involved, background research in public sources on natural and legal persons and individual investigations and individual audits. The auditors from KPMG had carried out standard auditing activities, which the company also carried out for other clients. Mr. Geschonneck listed IDW PS 302 as an example, according to which third-party confirmations were obtained. In this respect, no fundamental forensic activities were carried out.

In this paper, we show that Mr. Geschonneck’s perspective perfectly fits our model presented below. Thereby, we follow the recommendation of Minlei Ye to capture actual auditing practice in analytical auditing research (Ye, 2021, p. 72). If we assume a dyadic relationship between a local auditor and the client firm’s (local) management, we find an incentive for shallow auditing (restricting auditing diligence to a level that renders it superficially sound) when the local auditor is afraid of detecting severe problems that could cost him his auditing assignment with his client firm, including the loss of all future fees. Therefore, even though deep auditing (performing effortful auditing with the assumption that the firm’s accounting might be fraudulent) might help preserve the audit firm’s reputation, the local auditor will be less interested in deep auditing because his client is his entire business case; deep auditing could both reduce the profit of the local audit partner and increase the risk of revealing unpleasant news about the financially unhealthy state of the client firm. On the other hand, a fraudulent business firm is just another client for a large audit firm, adding only a small contribution to its total fees. Interestingly, the abovementioned IDW Standard PS 302 requires more or less mandatorily to obtain reliable external confirmations for funds, even with normal year-end closing work. This supports our argument that not fraud, but shallow auditing was at stake in the Wirecard case.

In the relevant literatureFootnote 1 (see, e.g., Karpoff & Lott, 1993; Alexander, 1999; Fich and Shivdasani, 2007), it is argued that a potential reputation loss may prevent auditing firms from superficial auditing and auditing that is too friendly. When accounting fraud is detected, the audit firm is blamed and may suffer a reputation loss. According to Karpoff et al. (2008), a reputational penalty can be defined as the expected loss in the present value of future cash flows due to lower sales and higher contracting costs. An implication of reputation theory is that reputation does not matter that much when its benefits are small and there are no substantial costs by losing it. Applied to a detected audit scandal in which the legal-regulatory system has imposed penalties, there is no substantial loss of reputation as long as the legal-regulatory costs are higher than the loss in future cash flows or stock market capitalization.

Nonetheless, this is only one part on the cost side. Fraud has resulted in economic advantages, such as for the Andersen partners before bankruptcy, and may not even result in personal reputation losses thereafter in the form of, for instance, unemployment. When the supply of experienced auditors for global firms is scarce, excess demand arises for their services, however inaccurate they have been in carrying out their audits. The scarcity of experienced auditors had a great impact on the market demand for Andersen auditors after the indictment and then conviction of the Arthur Andersen firm in 2002. Interestingly, the conviction of Arthur Andersen was legally based on the obstruction of justice in its role as auditor of Enron. Afterward, the industry underwent a rapid consolidation: While Arthur Andersen lost clients (for a detailed account of their client losses, see Jensen, 2003, 2006), the Andersen partners and employees moved into the remaining industry remarkably smoothly. Most of the partners and employees were hired by three firms of the so-called Big Four, whereas the fourth, PricewaterhouseCoopers, acquired only a small number of Andersen’s employees and partners. Grant Thornton, one of the largest second-tier firms, took the opportunity to move upward in the ranking of auditor experience and hired many former Andersen partners and employees, specifically 60 partners and 500 staff members (Bugbee Brown (2006), 47 f). All in all, although Arthur Andersen as a firm was dissolved, a loss of personal reputation did not seem to have followed the Andersen crisis. In accordance with Rajan and Zingales (2001), it can be said that auditing firms are human capital intense and have very little physical capital. Put differently, the employees are the firms’ capital.

Another implication of reputation theory is that high-quality auditing first translates into higher sales and profits and finally into reputational gains. But it may be the case that the market, namely the managers of the client firm, demand acquiescence and understanding. Interestingly EY increased its number of important audit clients in 2021 despite the Wirecard scandal mentioned above (Fehr, 2021). Thus, some clients may prefer opportunistic auditors who shy away from a clean opinion on financial statements, even when they suspect that the statements include omissions and misrepresentations. Depending on the market structure, some segments of the market may preferentially hire auditors who develop such reputations with managers (Ronen, 2006), especially given the fact that a critical audit report increases the probability that a client will switch auditors. Thus, auditors may not be encouraged to hand in a critical report (Levinthal & Fichman, 1988; Seabright et al., 1992).

From the beneficial side of reputation, client firms will not necessarily demand high-quality auditing in the form of critical reports. But what are the costs to audit firms for such misbehavior? The potential costs of fraudulent behavior have diminished since audit firms have mainly shifted from partnerships to limited liability entities (Ribstein, 2004). This has reduced their incentives to improve reputation and quality compared to the previous regime, where partners were jointly and severely liable for negligence.

It may be the case that both the beneficial effects of building up reputation and the costs of eventually losing it only materialize if there is a reasonable risk that misreporting will be “publicly” uncovered. The chances of such detection depend on several factors. Where auditors develop a reputation with managers as being acquiescent, the client firm will presumably not make a strong effort to uncover accounting problems. In addition, clients with a greater risk of fraud are less likely to engage new auditors in competitive bidding, consistent with the theory that these companies seek to limit access to information that might reveal their high-risk status (Adams et al., 2005). Among other factors, detection also hinges on the economic climate and profitability of the firm. In addition, the visibility of fraud plays a role, and the visibility itself derives from the characteristics of the client firm’s business. For example, empirical findings (Gerrety & Lehn, 1997) have shown that the costlier it is to value assets, the more likely accounting fraud becomes. One proxy for the ease of carrying out comprehensible audits could be the ratio of intangible to tangible assets in a client firm; the higher this ratio, the higher the potential for accounting fraud.

The importance of the business firm’s economic situation for fraud detection can be recognized by considering a profitable firm in a climate of economic prosperity. In this case, auditors are highly unlikely to be detected committing or ignoring fraud, because the profitability of the firm will hide fraud. Further, even if fraud is detected, the clients usually reimburse litigation costs, which may even increase an auditor’s reputation as being amenable to opportunistic clients, as any detected auditing misdeeds may show that an auditor is willing to cooperate with clients to the detriment of investors (Ronen, 2006).

After the Andersen-Enron audit scandal, most of the partners and employees were hired either by three of the Big Four firms or by aspiring second-tier audit firms. In more general terms, the market structure among audit firms and market demand for, as well as the scarcity of, experienced auditors directly determine the benefits and costs of audit reputation. These factors can easily outweigh effects of audit quality. Starting with the market structure of audit firms, mandatory audits of global firms create demand for a global network of experienced auditors. However, there exist only a small number of audit firms, i.e., the Big Four (or even fewer) first-tier firms and several second-tier firms.Footnote 2 Therefore, the expected losses of personal reputation of a fraudulent auditor seem to be rather small, even in the most extreme case of an audit firm going bankrupt. With such a bankruptcy, not only do choices among audit firms decrease, but audit firms’ choices of available auditors also decrease.

In the remainder of the paper, Sect. 2 sets the stage by presenting some facts on auditing scandals. Building upon that, a model for an extended auditing game is presented in Sect. 3. The first part of the model (3.1.) implicitly takes the perspective of the entire auditing firm, where reputational capital may be very high compared to the potential profit of doing superficial audits for a single client. The second part of the model (3.2.) shows from a more “local” perspective that when individual auditors interact with individual managers in fraudulent activities, both can profit while imposing costs on investors, that is, on parties other than those they do business with. Section 4 presents some policy implications, while Sect. 5 concludes.

2 Auditing scandals

In the Appendix, an impressive list of the biggest accounting scandals over the last decades can be found. For reasons outlined above, it is difficult to provide direct empirical tests for our analysis. The argument that clearly explains this difficulty arises from our analytical perspective: the dyadic relationship between a local auditor and the local management of the client firm. This relationship is, by definition, not covered by written contracts, especially when it includes fraud or at least poor oversight. But this does not preclude other propositions that can be made using the facts known about the scandals. We stress propositions concerning three aspects of auditing scandals:

-

1.

The importance of intangibles,

-

2.

The identity of the detectors of fraud and

-

3.

The scandal involvement of Big Four firms or their predecessors.

These determinants taken alone or viewed together call into question the empirical range of reputation theory. As will be explained below, even the most obvious stylized facts of these auditing scandals do not lend support to the most relevant claims made by reputation theory in accounting.

In the old industrial economy, with long-term assets, e.g., plants and equipment, the auditor had to validate data through extensive counting of inventory, etc. The economy-wide movement from tangible to intangible assets with very long lives and from liabilities whose principal and terms belong to other factors, such as found in derivatives, have substantially reduced the ability of all external observers, be they auditors or investors, to validate the values presented in the financial statements. The consequences of this development are severe: The more intangibles that are relevant in a firm’s business model, the more difficult the valuation of assets becomes. Gerrety and Lehn (1997) empirically found that the costlier it is to value assets, the more likely accounting fraud becomes. A good breeding ground for carrying out poor-quality audits could be intangible assets in a client firm. Our assumption – that the higher this ratio, the higher the potential for accounting fraud – shows up in the data in the Appendix. We use a crude proxy for intangibles according to the firm’s industry and/or its business model. As demonstrated, most firms involved in the biggest accounting scandals are highly intangible firms. These data hint at a possible connection between opportunities for and results of (at least) poor-quality audits.

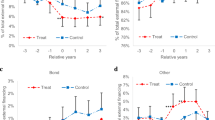

The finding explained above has a direct impact on the identity of those who uncover the fraud. Looking at the detectors, it is noticeable that around 50% of the 84 scandals mentioned were communicated by regulatory institutions, while investors, whistleblowers and the media discovered around 25% of them overall. In only around 11% of the scandals mentioned did the auditors involved report them to legal institutions. Assuming that U.S. regulators are experienced and technically and legally equipped to deal with these problems, it is noticeable that the intangible asset issue mentioned above makes it difficult for any actor outside the company to uncover these scandals. Therefore, it can be assumed that auditors and regulators are the most likely to detect fraudulent accounting. According to the academic literature on the impact of reputational loss on audit firms, one would expect audit firms to make every effort to detect fraudulent accounting. This would likely be reflected in fewer accounting scandals and a higher proportion of accounting fraud being uncovered by audit firms. However, this does not appear to be the case. Instead, the fairly low detection rate of audit firms fits well with our view that individual auditors interact with individual managers in accounting fraud. Otherwise, it is unclear how the low fraud detection rates in audits are consistent with the fact that accounting scandals uncovered by other individuals or institutions have significantly damaged the reputation of the respective audit firms.

Regarding the involvement of Big Four firms or their predecessor firms, it is notable that the major claim of audit reputation theory is that the more successful the audit firm (with size and sales as an indicator of successful reputation capital), the less likely it is to make sacrifices for an individual client firm. However, the data in the Appendix raise doubts about this. A simple comparison of the frequency with which at least one of the Big Four firms was involved in a scandal and the frequency with which it reported the matter to the authorities provides a rough idea of the success of the firms’ fraud detection: In 52 cases was at least one of the Big Four firms the audit firm,Footnote 3 but only in five cases did the audit firm uncover fraud. If one includes the cases in which the company itself discovered the fraud (presumably forced by the auditor), the number of cases discovered increases to 13 out of 52, or a quarter. This means that in at least three-quarters of the scandals mentioned, the respective audit firm did not uncover the fraud. Furthermore, because only large accounting scandals are considered, the magnitude of these scandals reflects the size of the client firm involved, which is most likely significantly correlated with the size of the audit firm that conducted the audit. According to reputation theory, the loss of audit firms’ reputational capital should be reflected in large business losses or bankruptcies of large audit firms and/or in unemployment of the auditors involved in the scandals. Although we cannot provide data for these variables, it may be enough to point out that only Arthur Andersen disappeared as a firm after being convicted of obstruction of justice in its role as Enron’s auditor. Whether these facts are consistent with reputation theory is an empirical question that cannot be answered here.

We cannot empirically distinguish the reasons why audit firms do not lose reputation capital after fraud or misbehavior is uncovered. One reason may be that in some segments of the market, auditors who have developed a profitable reputation with managers will continue to benefit (Ronen, 2006). Other reasons for the lack of reputation losses may include the inelastic supply of experienced auditors and the highly concentrated market of big auditing firms. Whatever the reasons, the empirical facts do not lend support for this part of the theory of reputation.

3 The extended auditing game

3.1 Structure of the game

In this section, the structure of the auditing game is shown. To start, we assume that both the audit firm and the client firm have two objectives, namely profit and reputation. Profit is the objective of both firms, and it depends to a certain extent on their reputation according to firm-outsiders’ viewpoints as investors, the general public and other firms. For the audit firm, reputation may be more important than for the client firm, mainly because an audit firm that is suspected to be unreliable might lose auditing contracts with other economic firms because these firms fear losing their investors’ confidence. This may imply that a minimum level of reputation is required for the audit firm. In contrast, it might be more relevant for the client firm to reach a minimum profit goal. However, it holds true for both firms that a higher reputation must be “bought” with lower profits, and vice versa. For instance, managers of the client firm could increase profits by using fraudulent accounting methods. Partners of the audit firm could increase profits by hiding fraudulent accounting, at the price of putting their own reputation and the firm’s reputation at risk.

The audit firm’s partners are relevant to the quality of the on-site audit. This aspect is captured by the notion of shallowing auditing (low-quality audit) in contrast to deep auditing (high-quality audit). As demonstrated experimentally by Balafoutas et al. (2020), offering professional internal auditors remuneration based on incentives led to these auditors under-reporting or over-reporting others’ performance, depending on whether the compensation scheme was competitive or collective. In addition, internal profit sharing and fixed compensation of partners in auditing firms was correlated with auditing quality in a German empirical investigation. Specifically, audit quality suffered the most when partners were remunerated mostly with variable compensation in cases of small profit pools (Ernstberger et al., 2020). In a Belgian investigation of Big Four audit firms, Dekeyser et al. (2021) also found connections between audit quality and the compensation of the partners. While there was a negative correlation between compensation by fees and audit quality, the correlation between partners’ “observable net wealth” and audit quality was positive (Dekeyser et al., 2021).

The above reasoning may have implications for the level of accuracy of accounting and auditing. Maximum reputation can be defined ex negativo as the absence of accounting fraud on the client firm’s side and as the absence of hiding or concealing accounting fraud on the audit firm’s side. The reputations of both firms depend on accuracy, such that a higher degree of accuracy is positively correlated with a higher level of reputation. As a consequence of these relationships, profit maximization and reputation maximization do not seem possible at the same time, as a trade-off exists between profits and reputation. Put differently, reputation is unattainable without incurring some cost. A further consequence is that maximal accuracy in accounting and auditing is also presumably not attainable. To paraphrase this with Darby and Karni (1973), there exists an optimum amount of fraud in a society with free competition but not freely available financial information. Hidden information inside the economic firm and the possibility of hidden actions of both firms are serious economic obstacles that stand in the way of preventing fraudulent behavior.

In the following, the behavior of the client firm and the audit firm will be studied in game-form (see Fig. 2 below). There are three players, the first player, the “Manager,” represents the management of the client firm, player two is the local auditor of the audit firm, namely the “Auditor,” and player three represents the external authority, the public prosecutors and the courts, called the “Courts.” The auditing game is a game with imperfect information. The management of the firm may be honest or fraudulent; this assumption is in accordance with the model by Corona and Randhawa (2010). Auditors of the firm cannot a priori know whether the management conducts honest or fraudulent accounting.

In the second stage of the game, the Auditor decides on the level of auditing. It is assumed here that each Auditor is of equally high ability, in contrast to Corona and Randhawa (2010). In their model, the type of auditor is defined ex ante and cannot change in the game; there, “nature” decides whether an auditor is of low or high ability. Instead, in our game, the Auditor chooses the level of auditing, i.e., whether the auditing will be deep or shallow, assuming that deep auditing is legally possible. Deep auditing means that auditors are completely independent and accurate up to the point of the minimum-profit constraint for the auditing firm. Such auditors might be called KantianFootnote 4 auditors. In contrast, shallow auditing implies that auditors either do not look actively to detect fraud or that they even collude tacitly with a fraudulent management.

With honest accounting, it does not matter whether the Auditor chooses deep or shallow auditing. The game ends at this point, and the payoffs for the Manager and the Auditor are doled out. With fraudulent accounting, the Auditor may or may not detect fraud, depending on the chosen level of auditing. Deep auditing is assumed to always detect fraud, whereas shallow auditing will never. In the last step, the Courts decide on the level of fines (big or small), and payoffs are made. We note that the “external” losses of the Auditor from shallow accounting always encompass both the reputation loss and the fine imposed by the Courts. In this paper, we refer to reputation losses as the present value of market-imposed losses of sales on audit firms due to their shallow auditing. Since the probability of detecting accounting fraud is exogenously determined by criminal courts, a multiperiod model seems not to be required.

The point that the probability of detecting fraud is exogenously determined leads to important implications. Structurally, in this three-player game, only two are active players in the sense that they make strategic choices. The Manager can choose to be honest or fraudulent, and the Auditor can decide to audit deeply or shallowly. The Courts, however, do not actively choose their fraud detection probability. This is rather given by an ex ante determined rate of control, as in other areas of state control, for instance, tax audits. In addition, it is worth mentioning that auditors are sworn in as “organs of the administration of justice.” This gives their statements greater credibility, and it can be interpreted as a partial delegation of financial law enforcement to the auditors’ profession.

The Auditor and the Manager are embedded in relationships with investors and the general public, which also encompasses former and potential investors, as well as organizations that observe the firm and the outcome of the audit. A second principal-agent relationship results from the interest of the investors and the public in the certification of fraud-free accounting by the Manager. Lawmakers belong to the general public, but they also provide the accounting rules for the Manager and the legal auditing rules for the Auditor. On behalf of the legal authorities as principal, the Auditor as an agent must verify the correct application of the accounting rules by the Manager. To incentivize the Auditor, the law provides fines for sanctioning the violation of auditing rules as well as public prosecutors and courts for law enforcement. In addition, investors might threaten to litigate against the Auditor if they recognize rule violations. The Auditor is dependent on the client firm insofar as the firm must provide the data for the audit. The quality of the audit report is, among other factors, determined by data quality. Moreover, the Auditor finds out a lot about the firm that can be useful for business consulting. In this way, the Auditor and the Manger can enter into a symbiotic relationship (Schanze, 1993).Footnote 5

In effect, auditors are “double agents” or “servants of two masters.” The state, representing investors’ interests by enacting accounting laws, is the first master, and the audited (client) company is the second master, as it selects and pays its auditor.Footnote 6 Nevertheless, only the Auditor and the Manager are strategically active and rational players. This corresponds with the practical experience of Richard Kaplan, in that the “corporate leadership” is the addressee of the audit report, not the investors or the public (Kaplan, 2014, p. 366). In Kaplan’s plain words: “After all, the audit personnel who were the subjects of praise and admiration were the ones who earned the highest epithet: ‘He [still always ‘he’] knows how to keep clients happy.’” (Kaplan, 2014, p. 365). In other words, strong incentives exist to not deliver negative audit results to the management that employs and remunerates auditors (Moore et al., 2006).

The state, represented by public prosecutors and courts, acts as “nature” in this game, since it does not strategically adjust the detection probabilities of law enforcement (see Tsebelis, 1990, for this differentiation).

3.2 The bright side of the game

In Fig. 2, the audit game of Fig. 1 is specified with additional assumptions. From the auditor’s viewpoint, “nature” selects the type of the firm management’s accounting method as either honest with probability h or fraudulent with probability 1-h. Nevertheless, it is the management that decides on honest or fraudulent accounting. Therefore, the Manager is an active player in the auditing game. The Auditor chooses deep or shallow auditing with probability d and 1-d, respectively. With deep auditing, accounting fraud is always detected with probability of 1. Applying shallow auditing, fraud is detected with probability p.Footnote 7 Detected accounting fraud is punished with a big fine, b, with probability f and with a small one, s, otherwise.

The payoffs are assumed as follows. Firstly, the case of honest accounting is described. The firm’s true profit is Y, net of accounting fees. In the case of shallow auditing, there is no additional cost (for instance, provide additional accounting evidence) due to the audit. With deep accounting, however, further accounting effort is necessary that reduces the firm´s profit by a. The accounting fee, F, contains two elements: a fixed fee of K and a variable component, c∙Y, that is dependent on the true profit of the firm:

In contrast to shallow accounting, deep accounting requires additional effort of the Auditor and imposes additional auditing cost of e. This reduces the remuneration of the Auditor to F-e.

Secondly, fraudulent accounting under deep auditing and fraud detection reduces the firm’s true profit to Y-a-b with a big fine and to Y-a-s with a small fine. With shallow auditing and undetected fraud, the firm’s profit is Y + g, with g > 0 as fraudulent profit. However, if the fraud is externally detected, the firm’s profit is Y − b with a big fine and Y − s with a small fine.The Auditor’s payoff with fraudulent accounting and deep auditing is F − e. With shallow accounting and undetected fraud, the Auditor payoff is F. However, with externally detected fraud the Auditor’s remuneration is assumed as K − r with K − r ≤ 0. This means that the Auditor loses its profit share, c∙Y, and receives only the fixed fee K which is not large enough to compensate for the losses that consist of a reputation loss, ρ, and a fine, D:

Furthermore, it is assumed that \(F-e>\left(1-p\right)F+p(K-r)\), i.e., that deep auditing provides a higher auditing remuneration than shallow auditing with external fraud detection. In addition, for the firm is supposed that fraudulent accounting brings about a higher payoff with shallow auditing, i.e., \(Y+\left(1-p\right)g-p\left[s+f\left(b-s\right)\right]>Y\).

To sum up, the payoffs read as follows (PF: payoff of the firm; PA: payoff of the Auditor):

-

Honest accounting

-

Deep auditing: PF = Y − a, PA = F-e, Y-a, F-e > 0,

-

Shallow auditing: PF = Y, PA = F

-

-

Fraudulent accounting

-

Deep auditing:

-

Big fine: PF = Y-a-b, PA = F-e

-

Small fine: PF = Y-a-s, s < b, PA = F-e

-

-

-

Shallow auditing:

-

Fraud detected:

-

Big fine: PF = Y-b, PA = K-r,

-

Small fine: PF = Y-s, PA = K-r

-

-

Fraud undetected: PF = Y + g, PA = F

First of all, it is checked whether there are pure strategy Nash equilibria for the auditing game. To check it, the payoffs are shown in the payoff matrix in Table 1.

As is easy to verify, there is no Nash equilibrium in pure strategies. With honest accounting on the side of the Manager, shallow auditing would be the best response of the Auditor, whereas with fraudulent accounting, deep auditing would be the Auditor’s best response. However, with deep auditing, honest accounting is the best response of the Manager, whereas with shallow auditing, fraudulent accounting would be the best response of the Manager. It follows that no “tacit collaboration” between Auditor and Manager, which will be discussed in 3.3., can become a possible equilibrium in the setting discussed here.

Therefore, the mixed-strategy equilibrium is determined. The firm’s expected payoff in the auditing is given by:

The auditor’s expected payoff yields:

The mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium of the non-cooperative auditing game results from the maximization of the respective expected payoffs, whereby the firm maximizes its payoff by choosing the probability for honest accounting, h, and the auditor the probability for deep auditing, d.

The firm’s maximization problem reads:

which gives the first-order condition:

and hence:

with:

The optimal probability for deep auditing is larger than zero if the potential gain by fraudulent accounting is higher than the expected punishment:

The auditor’s maximization problem reads:

which gives the first-order condition:

and therefore:

with

The probability for honest accounting is larger than zero if the reputation loss plus the fine is higher than the expected cost for deep auditing:

Moreover, the probability for honest accounting increases in both the fraud detection probability by shallow auditing, p, and the size of the reputation loss, r.

The mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium is, therefore, for \(g>\frac{p[s+f\left(b-s\right)]}{1-p}\) and \(r>\frac{e+pK}{p} \; \mathrm{for} \; r>K\) given by:

Note that the probability for deep auditing in the non-cooperative Nash equilibrium is increasing in the potential gain by fraudulent accounting, g, and decreasing in the exogeneous probability of fraud detection, p, and the exogenous probability for a high fine, f. By contrast, the probability for honest accounting in the non-cooperative Nash equilibrium, h, depends on the effort cost of the auditor, e, the size of the loss r and (K − r), as well as the exogeneous probability of fraud detection, p. The probability for honest accounting increases in r and in p for r > K.

It is to be noted that K from a single client is very small for a large audit firm, while its reputational capital at stake may be relatively high. But as is argued in the introduction above, the reputation loss after audit scandals was rather small. Therefore, the detection of accounting fraud depends predominantly on the exogenous detection probability, p.

3.3 The dark side of the game

The bright side of the auditing game is based on the implicit assumption that the Manager of the firm and the Auditor are actors in a non-cooperative game. This implicit assumption may be justified if there was only one principal-agent situation in the game Manager and Auditor are supposed to play. The Manager is the principal and the Auditor the agent who perform the audit to provide the Manager with a certification of honest accounting. As shown in Fig. 1, the assumption of a single principal-agent constellation is too simple.

The dark side of the double agency of the Auditor is that the quality of the audit depends on data reported by the Manager. As argued above, the close relationship between Manager and Auditor can bring about a symbiotic arrangement (Schanze, 1993) between them, although they are in a principal-agent relationship. The reason is that both the Auditor and the Manager have common interests. Both prefer less effort and cost, as well as higher incomes and profits (Hohenfels and Quick, 2020). In addition, the Auditor is paid by the first principal, the Manager, but not by the second principals, investors and the public. Concerning the second principals, the Auditor has a decisive interest not to be negatively sanctioned. Taking all aspects together, the Auditor and the Manager may consider playing according to their own rules, i.e., to cooperate. This cooperation may not be open, but rather tacit (Quick and Henrizi, 2019). Furthermore, shallow auditing in the past might slowly drive auditors to cooperate with managers now and in the future in order to cover-up auditing misbehavior in the past (Corona & Randhawa, 2010).

Another good point in case on how shallow auditing in tacit collusion does materialize are the activities of the audit firm EY in the Wirecard case. As the official Wambach Report clearly states several times, the problem was not fraudulent behavior by the Wirecard management deceiving the auditors, but shallow auditing:

“On March 29, 2017, the board of directors and the supervisory board were informed verbally and in writing about potential obstacles to the examination. The auditor announces a limited confirmation note of the Auditor for the consolidated and annual financial statements of Wirecard AG for the 2016 financial year, if not in the short term sufficient and adequate audit evidence on more than 20 open-ended questions relevant to the completion of central relevance and above all the fraud allegations of a whistleblower concern, will be submitted. The audit evidence received essentially consists of oral and written statements by the board of directors. A further clarification of the content of the open Points is not apparent from the working papers. The consolidated financial statements were published on April 5th, 2017, and the annual financial statements were published on April 25th, 2017, each issued an unqualified audit confirmation note” (Wambach, 2021, p. 36, own translation).

Since the seminal game theoretic papers of Bernheim et al. (1987) and Bernheim and Whinston (1987), it is well-known that a non-cooperative game might have a superior cooperative solution. Moreover, although binding cooperative commitments in the context of auditing are neither enforceable nor expedient, tacit cooperative commitments between Auditor and Manager may nevertheless be possible because of mutual interests in such a commitment.

If in the following the Auditor chooses shallow auditing–i.e., d = 0–with unity probability, the Auditor is called “tacitly cooperating” with the Manager. This assumption is in line with the earlier on mentioned statement by Mr. Geschonneck, the KPMG special auditor for Wirecard. Of course, it must pay for the Auditor to cooperate with the Manager in this way. Using (6) and inserting the results of (17) into \({EU}_{A}({d}^{*},{h}^{*})\), this will happen if the following condition is met:

with \({p}_{A}^{c}\) as the Auditor’s critical external detection probability.

Hence, for a critical external detection probability smaller than \({p}_{A}^{c}\), tacit collusion from the Auditor’s viewpoint is feasible because it provides a higher expected payoff. To put it differently: \({p}_{A}^{c}\) is the upper bound of the range within tacit collusion is feasible. The determinants of this bound are the effort level of deep auditing, e, the monetary and reputation losses by detection of shallow auditing, r, and the fixed fee for auditing, K, provided that r > K. Let K* be the upper limit that guarantees r > K for the individual audit firm. The critical detection probability \({p}_{A}^{c}\) for shallow auditing increases in K until K ≤ K* and decreases in r: \(\frac{\partial {p}_{A}^{c}}{\partial K}=\frac{e}{{(r-K)}^{2}}>0,\frac{\partial {p}_{A}^{c}}{\partial r}=\frac{-e}{{(r-K)}^{2}}<0\). Furthermore, the probability increases in e, the additional auditor effort for a deep audit, if \(r>K\). These results are in line with economic intuition as the higher K does not incentivize deep accounting since it is a fixed sum that is independent of auditing quality. But this also means that a higher K up to K ≤ K* implies a higher \({p}_{A}^{c}\). Hence, the more expensive the mere threat of losing K becomes when doing deep auditing, the larger gets the critical detection probability.

These results can easily be reconciled with the results of the empirical papers cited above. A higher K up to K* implies a higher \({p}_{A}^{c}\). Hence, the more expensive the mere threat of losing K becomes when doing deep auditing, the larger gets the critical detection probability. K can be viewed as “variable compensation” for local partners; Gosh and Siriviriyakul (2018) show for “K” that a 100% increase in tenure increases audit fees by 7% for the Big 4 audit firms.

The smaller K, e.g., because of a large profit pool of the audit firm, the less the incentive for shallow auditing, because the eventual loss of K and of one client will be compensated by the national or worldwide firm. We can interpret the size of the profit pool as a proxy for the size and the relevance of reputation for the national or worldwide firm. Therefore, the reputational concerns of the firm would lead to a quality enhancing income insurance of the client auditors on the local level. In this respect, firms with high reputation provide a comparable high difference between r and K. Thereby they decrease, c.p., the incentive for shallow auditing. It is worth mentioning that also greater supply of auditors could have a negative impact on K and therefore a positive impact on audit quality. This seems to imply that an additional potential solution would be to reduce barriers to entry such as regulation, licensure, and certification.Footnote 8

The dependency of local partners on high values of K–because of small firmwide profit pools–can be increased when partners carry extensive debt which leads to low audit quality (Dekeyser et al., 2021). By contrast, net wealth of the auditor, serving as an insurance coverage against fluctuating K up to K ≤ K*, positively affects audit quality (Dekeyser et al., 2021).

Furthermore, the Auditor’s critical external detection probability increases in e, the additional auditor effort for a deep audit. How can this be reconciled with empirical results? Gosh and Siriviriyakul (2018) show in their paper on quasi rents of tenure and effort that: “Audit effort decreases with audit firm tenure across all groups of filers,” that goes hand in hand with economic bonding between auditor and client. To illustrate the argument on effort e elaborated in our model, we assume that e2d (e1d, e1s) stands for shallow, s, and deep, d, auditing with quasi rents in t2 and in t1, respectively, with e2s < e1s < e1d < e2d (according to Gosh & Siriviriyakul, 2018). Therefore, it holds that (e2d–e2s) > (e1d–e1s), i.e., because of the decrease of effort with audit tenure over time a larger amount of effort would be required to exercise deep auditing in t2 after shallow auditing in t1 than to apply already deep instead of shallow auditing in t1.

The higher the total loss of the Auditor (measured as \(r=\rho +D\)) is when shallow auditing is detected, the smaller the range of the external detection probability that makes collusion attractive. Collusion is also attractive for the Auditor if the additional effort of deep auditing is high and the net loss of an externally detected fraud, r-K, is small.

The Manager will also tacitly collude with the Auditor if the expected payoff is larger with collusion, i.e., if \({EU}_{F}\left(h=0,d=0\right)>{EU}_{F}\left({h}^{*},{d}^{*}\right)\). The latter requires:

with \({p}_{F}^{c}\) as the Manager ‘s (and, hence, the firm’s) critical external detection probability. Note that there are two such values as the determining inequality is quadratic in p and has therefore two solutions for \({p}_{F}^{c}\).

This detection probability increases in the size of the fraudulent gain, g (as well as in the size of the fines, s and f(b-s)):

The Auditor and the Manager may collude rather than play non-cooperatively Nash, i.e., \((h=0,d=0)\), if both critical external detection probability values are low:

Given that the external detection probability of accounting fraud is rather small, the Manager has an incentive for fraudulent accounting and at the same time the Auditor has an incentive to audit shallowly. Although the brand of the audit firm may be destroyed (as, for instance, in the case of Arthur Andersen), the individual auditors are much less endangered by reputation loss. It is noteworthy that while a fraudulent firm is just another client for a large audit firm, adding only a small contribution to its total fees, this client is at the same time the entire business case of the local audit partner. If we assume a dyadic relationship between a local auditor and the (local) management of the client firm, we find an incentive for shallow auditing when the local auditor is afraid of detecting severe problems. That could cost her the auditing assignment with her client firm, including the loss of all future fees, and thereby putting her partnership at the audit firm at risk. Put differently, tacit collusion may be a cooperative solution for the audit game. The “local” perspective taken here is also applied by the Financial Reporting Council, FCR, in the UK, the audit and accounting regulator’s disciplinary tribunal, which in a recent case centers on the claim that the audit firm KPMG forged documents and provided misleading information during audit inspections. This inspection could result in fines, individuals being barred from the profession and other sanctions directed at individuals (WSJ, 2022).

3.4 Sed quis custodiet ipsos custodes (But who will guard the guardians)?

In his Nobel Prize lecture 2007, Hurwicz asked the old question of the Roman author Juvenal, “But who will guard the guardians?” The relevance of this question reveals itself if an insight of Hurwicz is accounted for, namely: “Truth is not a Nash equilibrium” (Hurwicz, 2007, p. 283), although in a different context. On the bright side of the auditing game, both the Auditor and the Manager play mixed strategies in the auditing game. As a consequence, “truth” is not fully guaranteed. On its dark side, the game demonstrates that there are substantial opportunities to cheat to the detriment of investors and the public. However, as briefly said above, the key problem is that auditors are the agents of two principals. Almost ironically, the principal who is the target of the auditing is obliged to choose and to pay the agent. This then leads to the question “But who will guard the auditors from misbehaving?” or as Myerson (2009, p. 69) put it “who enforces the enforcers (i.e., auditors) to enforce our (accounting) laws.”

It might be argued that more rigorous reading of the mixed Nash equilibrium of the non-cooperative auditing game gives several hints for a solution of the double agent problem. That is, the parameters of the model–the external detection probability of fraud, p, the probability for small and big punishments, s and b, the liability and reputation, r, of the audit firms–should be set to make deep auditing of auditors and honest accounting of managers–a dominant strategy. The simplest way to do that would be to set the external detection probability equal to unity, \(p=1\). However, if it were possible to set this probability equal to unity, why should there be auditors? Moreover, the sizes of punishments cannot be increased so much, that deep auditing and honest accounting will become a dominant strategy. The same holds true for the liability of audit firms. Finally, there are three additional variables that cannot be easily set externally: the fix payment for audits, K, the effort cost of auditing, e, and the size of the fraudulent profit, g. In this respect, the effort cost, e, is particularly relevant. The deeper the auditing is, the higher will be the effort cost–and the less likely becomes honest accounting according to the mixed strategy Nash equilibrium value, \({h}^{*}\).

Another solution to the Guardian issue might be internal guardians (Hurwicz, 2007; see Ronen, 2010, for an overview of several attempts to reform corporate auditing). Audit firms are business organizations with principals and agents within it. Even if the firm faces reputational constraints that may prevent the firm as a whole from (open or tacit) cooperation with the audited firm, this does not hold necessarily for the auditors as agents of the audit firm as a principal. The reason is that there may be strategic incentives for the individual auditor to ignore the reputational concern of the audit firm. In this respect, it is not the audit firm that may have a strategic incentive to cooperate with the managers of the audited firm, but the individual auditors. Therefore, internal guardians could probably solve the Guardian issue. As pointed out by Myerson (2009), such a solution would be based on (team) leaders within the audit firm organizations who monitor team members and prevent them from moral shirking, that is, from cooperating (openly or tacitly) with managers of the firm they audit. In this respect, team spirit (Alchian & Demsetz, 1972, p. 790) or a sense of group identity (Myerson, 2009, p. 74), supported and enforced by a team leader, might be at least a partial solution. However, even here the Guardian issue arises anew as the question remains who will guard team leaders themselves from misbehaving, except that team leaders are motivated by Kantian duty of beneficence (Mansell, 2013).

By theory, in (big) audit firms, the incentive for high-quality, deep auditing within an audit firm should come from career opportunities, in particular, from being promoted to a partner status. However, as it seems, to become a partner in an audit firm, auditors are motivated to attract new, wealthy client firms. This incentive deviates starkly form a high-quality incentive if new client firms value the cooperation between auditor and firm managers higher than deep, high-quality audits. Since the firms themselves choose and pay the audit firm, it seems not very likely that audit quality is decisive for the choice of the audit firm. Gosh and Siriviriyakul (2018) find that in Big Four audit firms, audit fees increase with tenure length whereas auditing costs decline. In contrast to smaller, non-Big Four firms, Big Four firms realize quasi rents from their lengthy tenure (Gosh & Siriviriyakul, 2018). The realization of quasi rents seems not to be related with audit quality, but rather with firm-auditor bonding. However, as long as the public perception of the reputation of the audit firm is not seriously damaged, complacent auditors may have a competitive advantage over high-quality auditors. To put it briefly, internal guardians provided by the audit firm’s organization may not solve the Guardian issue.

In recent times, a new form of internal guardian originated, namely whistleblowers. As insiders they have information advantages in comparison to persons outside firms. Moreover, whistleblowers can come from the audited firm, as well as from the audit firm. In the model presented above, whistleblower activities would increase the probability p for a detection of accounting fraud by a non-auditor. In several countries (e.g., U.S. and U.K.), whistleblowers are legally protected against retaliation and they may also receive rewards for whistleblowing. Although whistleblowing is an effective instrument to detect corporate financial fraud (Call et al., 2018; Wilde, 2017), it is also a double-edged sword against fraud. The first reason is that the rewards must be substantially large to compensate for the individual whistleblower’s risk and costs, but high rewards provide incentives for false reports (Givati, 2016; Buccirossi, Immordino and Spagnolo, 2017). The second reason is psychological. Whistleblowing, considered as a kind of denunciation, violates social norms of otherwise cooperating individuals. Its consequence might be a reduction of cooperation in the respective firms, as was demonstrated experimentally by Wallmeier (2019). After all, Jenk (2016) argues that whistleblowing may be good for society, but does not pay for the whistleblower. Hence, although whistleblower can add power to the enforcement of legal rules by detecting accounting fraud, the personal consequences are seemingly too serious so that whistleblowing will rather be an exception. Therefore, it may not increase the detection probability, p, to a decisive extent.

Another solution of the Guardian issue is external guardians (Hurwicz, 2007). As indicated by Eq. (23), cooperation between Auditor and Manager depends on the critical size of the external detection probability. This is empirically evident from the accounting scandals reported in Sect. 2 and in the Appendix, but also from Dyck et al. (2010).

The most promising external guardians are:

-

Regulators and other authorities,

-

Investors (short sellers) and

-

The media

Regulators and authorities determine the legal standards of accounting, but they must also enforce the respective rules. In effect, they define the “rules of the game” and are responsible for rule enforcement, i.e., they are the referees. In this respect, auditors are agents of the rule enforcers. In contrast to auditors, regulators and authorities do not have a strategic incentive problem,Footnote 9 but an information incentive problem. The strategic incentive issue of auditors is the result of the principal-agent relationship between auditors and managers, where the firm of the manager pays the agent-auditors. The information incentive issue between the regulators and authorities on one side and auditors on the other side results also from a principal-agent relationship where the agent is not paid by the principal. However, the agent-auditors have an informational advantage in this relationship that they may use in their own economic interest. Put differently, the auditors may earn an information rent due to their knowledge of the internal financial accounting of the firm they audit. This information will not necessarily be shared with the principal-authority. Therefore, the authorities may not be able to respond in a timely manner to prevent scandals. Although the respective authorities are institutionally indispensable, they are not equally well suitable external guardians. Finally, as argued and theoretically demonstrated by Ewert and Wagenhofer (2019), there might be too much enforcement that decreases the quality of firms’ financial reporting as enforcement and auditing can be either complements or substitutes for each other.

This is different for investors and in particular for short-sellers. Although they do not have a direct relationship with auditors, they have financial stakes in the respective firms. Investors and short-sellers have, therefore, strong monetary incentives for monitoring firms from outside. The latter is not possible without information that exceeds what is publicly known about firms. Even gossip might be relevant for them. The possibility for short-selling stock is a strong instrument to transform new information into actions and money. The downside of short-selling is, of course, that it can falsely put enormous pressure on firms or even ruin them. This downside is mitigated by respective short-selling risks for short-sellers themselves, for instance, when stocks become more expensive than expected (Engelberg et al., 2018). Nevertheless, short-sellers have more information than other traders (Reed, 2013), and this informational advantage is crucial for their role in fraud detection.

In the external detection of corporate fraud, the media may participate. Recently, this became visible to the general public by investigations in tax evasion, as e.g., the so-called Panama papers. However, according to Rosoff (2007), mass media in particular may be a cure, but also a cause of corporate crime. The reason is that mass media may enhance the hype of new firms over and above of realistic expectations. In addition, mass media may increase the public’s expectation gap with respect to the function and objective of audits, particularly after the detection of corporation fraud (Cohen et al., 2017). Media can also be a cure for corporate fraud as investigative journalism supports the detection of such crimes.

In the aftermath of the Wirecard scandal in Germany, Ewert and Wagenhofer (2020) ask for more transparency of audits and their results. According to recommendations of Ewert and Wagenhofer, besides the publication of problems with internal control systems of big enterprises and a better coordination of the regulatory authorities, the quality of audits should be published to force reputation losses on audit firms with shallow audits. As said in the first section of this paper, the main issue is that even scandalous firm events seem not to reduce reputation of auditors (partially in contrast to audit firms) to a significant extent. The complexity of auditing, as well as the scarcity of experienced auditors, may prevent auditors from the consequences of detected financial fraud scandals. Therefore, it seems rather unlikely that transparency of audit quality is the key in the fight of corporate fraud. In effect, transparency may not be a reliable external guardian in the Guardian issue.

4 Policy implications

To incentivize auditors to certify only deeply researched financial statements of their client firms is a very difficult task. In our paper, the double-agent nature of the auditor-firm relationship is the key to the understanding of the issue. Despite legal regulations and professional standards, auditors are selected by firms and also paid by them. In this way, the relationship between auditors and their client firms resembles a symbiotic attachment. Put differently, there is an asymmetry for the auditor double-agent that tilts the game to the favor of the firm.

As argued in the relevant literature, the audit firm has “skin in the game” (Taleb, 2018) as it risks its reputation by shallow auditing or even collaboration with a fraudulent firm. However, as the accounting scandals demonstrate, this “skin” is not really big. The reason is that only a few big auditing firms are able and capable to audit large corporations. Even if an audit firm is destroyed in an accounting scandal, the firms’ partners and employees do not lose much in such an event because they are needed furthermore in the business. Since whistleblowing is also questionable, the question arises as to how the incentives for deep auditing can be strengthened.

Increasing the liability of the auditing firms might be such an instrument. As pointed out by Ronen, the success of this policy hinges on the expected liability costs that are determined by the probability of fraud detection by the regulator and the respective civil litigation (Ronen, 2010, p. 203). According to Ronen, the detection probability is low and the chances for civil litigation are lower or even nonexistent (Ronen, 2010, p. 204). Finally, the liability costs can be transferred to the clients (Ronen, 2010, p. 204). In this way, the intended incentives deflagrate.

Ronen (2002, 2006, 2010) himself proposed another solution to the auditor incentive issue, a so-called “Financial Statement Insurance,” FSI for short. Firms are free to buy such an insurance or not. If they buy it, the insurer investigates “the risk of omissions and misrepresentations by examining a company’s internal controls and management incentive structures, its history and competitive environment, and other relevant factors” (Ronen, 2010, p. 205). In addition, the insurer determines the coverage and the premium that a company must pay. An insured firm can select an auditor from a list that is provided by the insurer that also pays the auditing fees. The latter will then be reclaimed by the insured firm. Most importantly, the investors are insured in this way and not the managers or the company. That is, if investors suffer losses due to omissions or misrepresentations in the financial statement, they are compensated by the insurer (see Ronen, 2002, 2006, as well as Ronen & Yaari, 2002; Ronen & Sagat, 2007, for more details).

Ronen’s idea is in line with the model provided here. The main idea is to insure investors against the risk of fraudulent accounting by letting the respective firms pay for it. However, firms that chose a financial statement insurance have an incentive to avoid fraudulent accounting since they may not get such an insurance anymore if they were detected to be fraudulent. Moreover, the insurer takes over the responsibility to select trustworthy auditors for its list. Since the auditors are now paid by the insurer, the relationship between auditor and its client firm will change as there will be no incentive for a symbiotic relationship. The double-agent nature of auditors is dissolved as the principal of the auditor is now the insurer.

However, the insurance solution of Ronen did not find much support. The main reason might be that it is too complicated and that it requires a completely new insurance scheme. According to the ‘dark side’ of our above model, it might even be possible that the insurance and the auditors cooperate with each other to the disadvantage of investors.

A final attempt to tilt the auditing game to investors could be that investors as a group decide which auditing company is selected and investors pay the auditing directly. In this concept, investors are clearly the sole principal of auditors. The crucial issue of the concept is the heterogeneity and the number of investors. One could argue that the board of supervisors is the adequate representation of investors’ interests. If this is accepted, this board may select the auditors and pay them by reimbursing the payment directly from investors by, e.g., reducing their dividend payments accordingly. Nevertheless, also this approach is not completely immune to dark-side cooperation between auditors and managers. The information rent of auditors can be big enough to collaborate with a fraudulent management.

As it seems, the policy implications of the analysis in this paper is as follows:

-

1.

It will not be possible to create incentives such that the first-best solution of a fraud-free corporate world is realized. The reason is the information asymmetry between the firm and auditors on one side and the investors on the other side.

-

2.

The remaining approaches to tilt the auditing game to investors are:

-

a.

Whistleblowers,

-

b.

Short sellers among the investors and

-

c.

Journalists and the media.

-

a.

-

3.

Although the mentioned persons may take part in improving the quality of accounting and auditing, these approaches have their own downside. Whistleblowers, short-sellers and journalists can falsely claim fraud and harm businesses and likely investors. Therefore, careful handling of such claims is recommended.

5 Conclusion

In this paper, auditing is investigated as a privately provided public good. The main aim of auditing is to protect the public and actual, as well as potential, investors from accounting fraud. However, auditors are paid by the firm for auditing. According to agency theory, auditors are agents of two principals whose objectives are not identical. In particular, managers of firms have their own aims that may deviate from their firm’s aims. In a game between two principals and one agent, the possibility for complicity occurs. This gives rise to two games with different outcomes, a bright-side game where auditing as a public good is provided with high quality. However, there may also exist a dark-side game where the auditors conspire with the management of the audited firm. Unfortunately, this conspiracy may not be a criminal association, but rather a tacit symbiotic arrangement. The existence of a criminal association can be detected with respective investigations. Tacit symbiotic arrangements are difficult to detect and even more difficult to prove.

In this paper, both the bright-side game and the dark side game are solved. It is demonstrated that shallow auditing is a method for tacit symbiotic arrangements that is not only difficult to detect, but also even more difficult to prevent. In particular on the cost side, the loss of reputation of the audit firm may not be very noticeable for the auditors themselves. Although the brand of the audit firm may be destroyed (as, for instance, in the case of Arthur Andersen), the individual auditors are much less endangered by reputation loss. On the revenue side, the client firm is the entire business case of the local audit partner. If we assume a dyadic relationship between a local auditor and the (local) management of the client firm, we find an incentive for shallow auditing if the local auditor is afraid of detecting severe problems that could cost her the auditing assignment with her client firm, including the loss of all future fees. Given that an auditing firm’s capital consists to a very large extent of the auditors’ human capital (Rajan & Zingales, 2001) and that the availability of auditors who are able to audit large companies is restricted, the auditing firm’s reputation loss does not extend to auditors. As a consequence, reputation loss is only a weak threat to shallow auditing, i.e., to collaborate tacitly with the audited firm.

Since the dark-side collaborative game, in particular between local auditors and managers, is hardly to deter by usual policy methods, unusual internal and external controls by persons with “skin in the game” (Taleb, 2018) seem to be required. Whistleblowers from inside the firm, short-sellers, as well as journalists and the media are the relevant persons here.

Nevertheless, it is to emphasize that it will not be possible to reach the first-best state of fraud-free firm finances.

Notes

See Ye (2021) for a thorough review of theoretical papers in auditing research.

Some companies involved in accounting scandals employed more than one auditing firm.

Dabrowka Grodz (2016) proposed a policy to change the appointment and payment of external auditors. She suggested a Public Auditing Board whose obligation is to appoint and pay auditors. In this way, the “second master” would take over the role of the principal in the auditing game.

In a variant of the audit game in Appendix 2 of this paper, a strategically active (large) investor is included who decides whether to trust the auditor’s certificate and hold the investment or to distrust it and sell the investment.

Gimbar and Mercer (2021) report that auditors overestimate the probability of a jury verdict because of negligence, and therefore, they also anticipate too negative consequences for reputation and litigation. However, since these results are found in a rather artificial environment (auditors had to decide on the risk that a jury will return a verdict in real negligence lawsuits), it seems not applicable to behavior in the practice of auditing (see, for instance, Kaplan, 2014).

We owe this aspect to an anonymous reviewer of an earlier version of this paper.

Nonetheless, regulators may face their own incentive problem, as explored in the regulatory capture literature. – We owe this point to an anonymous reviewer.

References

Adams, F. G., Bedard, J. C., & Johnstone, K. M. (2005). Information asymmetry and competitive bidding in auditing. Economic Inquiry, 43(2), 417–425.

Alchian, A. A., & Demsetz, H. (1972). Production, information costs, and economic organization. American Economic Review, 62(5), 777–795.

Alexander, C. R. (1999). The nature of the reputational penalty for corporation crime: Evidence. Journal of Law and Economics, 42, 489–526.

Balafoutas, L., Czermak, S., Eulerich, M., & Fornwagner, H. (2020). Incentives for dishonesty: An experimental study with internal auditors. Economic Inquiry, 58(2), 764–779.

Bernheim, B. D., Peleg, B., & Whinston, M. D. (1987). Coalition-proof Nash equilibria I concepts. Journal of Economic Theory, 42, 1–12.

Bernheim, B. D., & Whinston, M. D. (1987). Coalition-proof Nash equilibria II applications. Journal of Economic Theory, 42, 13–29.

Buccirossi, P., Immordino, G., & Spagnolo, G. (2017). Whistleblowers rewards, false reports and corporate fraud. CEPR Discussion Paper no. 12260.

Bugbee Brown, A. (2006). Private Firms Working in the Public Interest-Is the Financial Statement Audit Broken? PhD Dissertation Pardee RAND Graduate School.

Call, A. C., Martin, G. S., Sharp, N. Y., & Wilde, J. H. (2018). Whistleblowers and outcomes of financial misrepresentation enforcement actions. Journal of Accounting Research, 56(1), 123–171.

Cohen, J., Ding, Y., Lesage, C., & Stolowy, H. (2017). Media bias and the persistence of the expectation gap: An analysis of press articles on corporate fraud. Journal of Business Ethics, 144, 637–659.

Corona, C., & Randhawa, R. S. (2010). The auditor’s slippery slope: An analysis of reputational incentives. Management Science, 56(6), 924–937.

Cox, J. D. (2006). The oligopolistic gatekeeper: The US accounting profession. Duke Law School Legal Studies Paper No. 117. Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=926360

Darby, M. R., & Karni, E. (1973). Free competition and the optimal amount of fraud. The Journal of Law and Economics, 16(1), 67–88.

Dekeyser, S., Gaeremynck, A., Knechel, W. R., & Willekens, M. (2021). The impact of partners’ economic incentives on audit quality in Big 4 partnerships. Accounting Review, 96(6), 129–152.

Deutscher Bundestag (Hg.) (2021). Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des dritten Untersuchungsausschusses der 19. Wahlperiode gemäß Artikel 44 des Grundgesetzes. 19. Wahlperiode, Drucksache 19/30900.

Doxey, M., Lawson, J., Lopez, Th., & Swanquist, Q. (2021). Do investors care who did the audit? Evidence from form AP. Journal of Accounting Research, 59(5), 1741–1782.

Dyck, A., Morse, A., & Zingales, L. (2010). Who blows the whistle on corporate fraud? Journal of Finance, 65(6), 2213–2253.

Eisenberg, T., & Macey, J. R. (2004). Was Arthur Andersen different? An empirical examination of major accounting firm audits of large clients. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 1(2), 263–300.

Engelberg, J. E., Reed, A. V., & Ringgenberg, M. C. (2018). Short-selling risk. Journal of Finance, 73(2), 755–786.

Ernstberger, J., Koch, C., Schreiber, E. M., & Trompeter, G. (2020). Are audit firms‘ compensation policies associated with audit quality? Contemporary Accounting Research, 37(1), 218–244.

Ewert, R., & Wagenhofer, A. (2020). Transparenz schützt vor Betrug. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Nr. 301 vom 28.12.2020, p. 16.

Ewert, R., & Wagenhofer, A. (2019). Effects of increasing enforcement on financial reporting quality and audit quality. Journal of Accounting Research, 57(1), 121–168.

Fehr, M. (2021). EY steigert trotz Wirecard die Zahl wichtiger Prüfungskunden. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Vom, 02(11), 2021.

Fich, E., & Shivdasani, A. (2007). Financial fraud, director reputation, and shareholder wealth. Journal of Financial Economics, 86, 306–336.

Financial Market Integrity Strengthening Act (2021). Gesetz zur Stärkung der Finanzmarktintegrität (Finanzmarktintegritätsstärkungsgesetz, FISG) vom 03. Juni 2021. Bundesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2021 Teil I Nr. 30: 1534–1567.

Gerrety, M., & Lehn, K. (1997). The causes and consequences of accounting fraud. Managerial and Decision Economics, 18, 587–599.

Gimbar, C., & Mercer, M. (2021). Do auditors accurately predict litigation and reputation consequences of inaccurate accounting estimates? Contemporary Accounting Research, 38(1), 276–301.

Givati, Y. (2016). A theory of whistleblower rewards. Journal of Legal Studies, 45, 43–71.

Gosh, A., & Siriviriyakul, S. (2018). Quasi rents to audit firms from longer tenure. Accounting Horizons, 32(2), 81–102.

Grodz, D. (2016). The regulation of external audit in the UK and US and a proposal for a new audit model. PhD Thesis, Queen Mary University of London, Department of Law, 2016.

Hohenfels, D., & Quick, R. (2020). Non-audit services and audit quality: Evidence from Germany. Review of Managerial Science, 14, 959–1007.

Hurwicz, Leonid (2007). But who will guard the guardians? https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/hurwicz_lecture.pdf.

Jenk, J. (2016). The economics of whistleblowing – it doesn’t pay. Conference Paper. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299599113.

Jensen, M. C. (2003). A theory of the firm. Harvard University Press.

Jensen, M. C. (2006). Should we stay or should we go? Accountability, status anxiety, and client defections. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51, 97–128.

Jones, C., Temouri, Y., & Cobham, A. (2018). Tax haven networks and the role of the Big 4 accountancy firms. Journal of World Business, 53, 177–193.

Kaplan, R. (2014). Mother of all conflicts: Auditors and their clients. University of Illinois College of Law, Law and Economics Working Papers, Year 2014, Paper 13.