Abstract

Both the GAO (Public accounting firms: mandated study on consolidation and competition. GAO, Washington, 2003; Audits of public companies: continued concentration in audit market for large public companies does not call for immediate action. GAO, Washington, 2008) and the US Treasury (Advisory committee on the auditing profession: final report, 2008. http://www.tres.gov/offices/domestic-finance/acap/docs/final-report.pdf) have implied that the Big 4 dominated US audit market lacks competition. More recently, the PCAOB has expressed a somewhat different concern, i.e., that because audit committees may be primarily interested in negotiating a lower audit fee (rather than championing higher audit quality) for their clients, fee competition in the US audit market could pressure the incumbent auditor to compromise on audit quality (Doty in Keynote address: the reliability, role and relevance of the audit: a turning point, 2011. www.pcaobus.org). We utilize the notion of counterfactual fees chargeable by auditors to assess fee competition and investigate competing views on the relation between fee competition among Big 4 auditors and audit quality in US local audit markets. To operationalize fee competition at the client-level in the context of each local audit market, we compute a separate counterfactual audit fee that would be charged by every other Big 4 auditor for that particular engagement and use the minima of the counterfactuals. We validate our audit fee competition metric by showing a positive relation with the incumbent auditor’s switching risk. Collectively, our findings suggest that fee competition is useful as a mechanism for improving audit quality in the highly concentrated US audit market, albeit only in local audit markets where the incumbent auditor has below-median market power and only for higher quality clients. Overall, our findings speak to the interplay between fee competition and auditor incentives and are of potential interest to regulators such as the PCAOB concerned about competition in US audit markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We focus on the Big 4 firms because of their oligopolistic dominance of the highly concentrated US audit market and to avoid the confounding audit quality effects of Big 4 versus non-Big 4 auditors. Consistent with prior research, we use the terms “city,” “local audit market” and “CBSA” (Core Based Statistical Area) interchangeably to vary the exposition. The US Office of Management and Budget defines CBSA as an area surrounding an urban center of “at least 10,000 people and adjacent areas that are socio-economically tied to the urban center by commuting.”

As noted by DeFond and Zhang (2014), audit fee models have very high explanatory power (R-squares) and, consequently, estimates derived from audit fee models are reliable. In our study, our fee estimation model R-squares range between 75 and 79%.

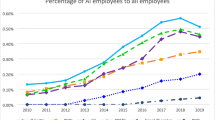

As reported in Accounting Today, the commoditization of the Big 4 audit is part of the motivation behind the rapid growth of nonaudit services, albeit to nonaudit clients, at the Big 4 firms from 48 to 62% of total revenues between 2004 and 2013. PCAOB Chairman Doty (2013) notes that within 10 years for these firms audit fees are likely to amount to less than 20% of total revenues.

Cohen et al. (2010) suggest that CFOs, rather than audit committees, continue to hold power in the hiring of the auditor. Also, survey evidence of CFO beliefs suggests that earnings management is common and that approximately a fifth of public companies manage earnings in any given year (Dichev et al. 2013). Hence, it is not unreasonable to view at least some clients with a Big 4 auditor as reprobate or lower quality, i.e., as preferring a lower (rather than a higher) quality Big 4 audit. Relatedly, Doty (2013) notes that PCAOB inspections have identified and documented promises by auditors to clients to be their “trusted partner” and to support the client in obtaining a “desired outcome” in accounting matters. DeFond et al. (2000) report that in China higher audit quality is associated with loss of market share.

Our discussions with Big 4 auditors suggest that faced with audit fee competition from another Big 4 auditor, the incumbent may offer incentives that are often personnel related. In other words, given the high levels of staff turnover in public accounting, it can be frustrating for a client to have to answer the same questions repeatedly or otherwise “train” the auditor’s staff year after year. Hence, an offer of personnel-related incentives (such as more senior/experienced personnel assigned to the audit) may be sufficient to ward-off a client bid process with little or no fee discount.

“If we want the audit profession to compete on quality more than price, we’ve got to provide markets more information about the audit,” Doty (2013, p. 9). Proposed PCAOB initiatives such as a more explanatory audit report (opinion), identifying the engagement partner on an audit, disclosure of other firms participating in the audit are all intended to help investors better judge audit quality.

As noted previously (fn. 4), the incumbent Big 4 auditor may offer to assign its “A-team” (i.e., its more senior and experienced personnel) to the client’s audit. Given the high levels of staff turnover in public accounting, it can be frustrating for a client to have to answer the same questions repeatedly or otherwise “train” the auditor’s staff year after year. Hence, an offer of personnel-related incentives may be sufficient to ward-off a client bid process.

Prior research (e.g., Banker et al. 2003) on the audit industry production function pools data at the national level for both Big 4 and non-Big 4 audit firms, i.e., implicitly assumes that the production function is the same for all (Big 4 as well as non-Big 4) audit firms. By contrast, we examine the audit fee model for each Big 4 firm separately for each year over our study period (2005–2015). Put differently, we add to the degrees of freedom in our estimation of AFCOMP by allowing the fee models (Appendices 1 and 3) to be different for each Big 4 firm each year. The significant differences in the coefficients of the annual regressions for the Big 4 firms (reported in Appendix 1) justify this modeling choice consistent with the reasonable notion that these audit firms are not homogenous and that pricing models can vary by audit firm.

We are grateful to Elaine Mauldin for sharing the audit committee related data.

All variables are winsorized in the (1, 99%) range. To avoid sample attrition, mean values for the industry-year are used for missing control variables. Exclusion of client-years with such missing data does not change conclusions.

Significant correlations among the independent variables (other than the test variables AFCOMP_NEG and AFCOMP_POS) are not a concern since they do not affect any of our test results or interpretations, and are therefore not reported for brevity. Later in the study we report VIFs.

Recall that AFCOM_NEG implies absence of audit fee competition, i.e., for this particular audit engagement no other Big 4 auditor has a counterfactual fee that is lower than that of the incumbent Big 4 auditor.

Additionally, the correlation of AFCOMP with abnormal audit fees for AFCOMP > 0 is 0.0169 and for AFCOMP < 0 is 0.0354. This further confirms that our competition measure is fundamentally different from abnormal audit fees.

In Table 7, for lower quality clients, our test variable AFCOMP_POS is significant only for one audit quality proxy (DACC), i.e., significant with a positive sign in column 1, which appears to provide weak support for the PCAOB concern that audit fee competition may lower audit quality. However, this concern applies only for lower quality clients, i.e., clients where the relative power of the audit committee vis-à-vis the CFO is below median.

We utilize 1-digit (rather than 2-digit) SIC for practical reasons. With 2-digit SIC, there are over 50 industries, and 4 Big 4 auditors × 11 years × 50 industries implies over 2200 regressions with the 12,618 observations in our sample (see Table 1), i.e., an average of only 6 observations per regression. Even with the 1-digit SIC, for industries with SIC codes 0 and 9 we do not have enough observations to run by year and auditor; hence, for these 2 industries (51 + 48 = 99 observations) we run the regressions only by auditor.

One limitation of AFCOMP is that we do not know which audit office of the other Big 4 firm would perform the engagement if in fact the lowest counterfactual fee was accepted by the client. However, when we use the incumbent auditor’s attributes and the characteristics of the incumbent’s CBSA in estimating AFCOMP, sequential regression analysis shows that 96% of the explanatory power of model (3) comes from client characteristics and only 4% from audit office and audit market characteristics. Hence, the measurement error in AFCOMP is expected to be minimal. Moreover, any measurement error in AFCOMP is likely to bias the coefficient against being significant.

References

Antle R, Gordon E, Narayanamoorthy G, Zhou L (2006) The joint determination of audit fees, non-audit fees, and abnormal accruals. Rev Quant Financ Acc 27:235–266

Ashbaugh H, LaFond R, Mayhew B (2003) Do nonaudit services compromise auditor independence? Further evidence. Account Rev 78(3):611–639

Asthana S (2017) Diversification by the audit offices in the US and its impact on audit quality. Rev Quant Financ Acc 48:1003–1030

Asthana S, Boone J (2012) Abnormal audit fee and audit quality. Audit J Pract Theory 31(3):1–22

Asthana S, Raman KK, Xu H (2015) US-listed foreign companies’ choice of a US-based vs. home country-based Big N principal auditor and the effect on audit fees and earnings quality. Account Horiz 29(3):631–666

Ball R, Jayaraman S, Shivakumar L (2012) Audited financial reporting and voluntary disclosure as complements: a test of the confirmation hypothesis. J Account Econ 53:136–166

Balsam S, Krishnan J, Yang J (2003) Auditor industry specialization and earnings quality. Audit J Pract Theory 22:71–97

Banker R, Chang H, Cunningham R (2003) The public accounting industry production function. J Account Econ 35:255–281

Baumol W, Panzar J, Willig R (1982) Contestable market and the theory of market structure. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc

Beasley M, Carcello J, Hermanson D, Neal T (2009) The audit committee oversight process. Contemp Account Res 26(1):65–122

Beck M, Mauldin E (2014) Who’s really in charge? Audit committee versus CFO power and audit fees. Account Rev 89(6):2057–2085

Beck M, Francis J, Gunn J (2013) Auditing and city-level human capital. Working paper, University of Missouri-Columbia, MO

Bell T, Landsman W, Shackelford D (2001) Auditors’ perceived business risk and audit fees: analysis and evidence. J Account Res 39:35–43

Bell T, Doogar R, Solomon I (2008) Audit labor usage and fees and business risk auditing. J Account Res 46:729–760

Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE (1980) Regression diagnostics: identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. Wiley, New York

Boone J, Khurana IK, Raman KK (2012) Audit market concentration and auditor tolerance of earnings management. Contemp Account Res 29(4):1171–1203

Boone J, Khurana IK, Raman KK (2015) Did the 2007 PCAOB disciplinary order against Deloitte impose actual costs on the firm or improve its audit quality? Account Rev 90(2):405–441

Butler M, Leone A, Willenborg M (2004) An empirical analysis of auditor reporting and its association with abnormal accruals. J Account Econ 37(2):139–165

Cabral L (2017) Introduction to industrial organization, 2nd edn. MIT Press, Cambridge

Chen L, Krishnan G, Pevzner M (2012) Pro forma disclosures, audit fees, and auditor resignations. J Account Public Policy 31:237–257

Choi J, Kim J, Zang Y (2010) The association between audit quality and abnormal audit fees. Audit J Pract Theory 29(2):115–140

Choi J, Kim J, Qui A, Zang Y (2012) Geographic proximity between auditor and client: how does it impact audit quality. Audit J Pract Theory 31(2):43–72

Chow GC (1960) Tests of equality between sets of coefficients in two linear regressions. Econometrica 28(3):591–605

Chung H, Kallapur S (2003) Client importance, nonaudit services, and abnormal accruals. Account Rev 78(4):931–956

Cohen J, Krishnamurthy G, Wright A (2010) Corporate governance in the post-SOX era: auditors’ experiences. Contemp Account Res 27(3):751–786

Dechow P, Ge W, Larson C (2011) Predicting material accounting misstatements. Contemp Account Res 28(1):17–82

DeFond ML, Jiambalvo J (1994) Debt covenant violation and manipulation of accruals. J Account Econ 17(January):145–176

DeFond M, Zhang J (2014) A review of archival auditing research. J Account Econ 58(2):275–326

DeFond M, Wong T, Li S (2000) The impact of improved auditor independence on audit market concentration in China. J Account Econ 28:269–305

DeFond ML, Raghunandan K, Subramanyam KR (2002) Do non-audit service fees impair auditor independence? Evidence from going concern audit opinions. J Account Res 40(4):1247–1274

Demsetz H (1973) The market concentration doctrine. American Enterprise Institute, Stanford

Dichev ID, Graham JR, Harvey CR, Rajgopal S (2013) Earnings quality: evidence from the field. J Account Econ 56:1–33

Doogar R, Sivadasan P, Solomon I (2015) Audit fee residuals: costs or rent? Rev Acc Stud 20(4):1247–1286

Doty J (2011) Keynote address: the reliability, role and relevance of the audit: a turning point. May 5. www.pcaobus.org

Doty J (2013) The role of the audit in the global economy. April 18. www.pcaobus.org

Doyle J, Weili G, McVay S (2007) Accruals quality and internal control over financial reporting. Account Rev 82:1141–1170

Dye R (1991) Informationally motivated auditor replacement. J Account Econ 14:347–374

Ettredge M, Fuerherm E, Li C (2014) Fee pressure and audit quality. Acc Organ Soc 39:247–263

Ettredge M, Fuerherm E, Guo F, Li C (2017) Client pressure and auditor independence: evidence from the ‘‘Great Recession” of 2007–2009. J Account Public Policy 36(4):262–283

Francis JR, Michas P (2013) The contagion effect of low-quality audits. Account Rev 88(2):521–552

Francis JR, Yu M (2009) Big 4 office size and audit quality. Account Rev 84(5):1521–1552

Francis JR, Pinnuck M, Watanabe O (2013) Auditor style and financial statement comparability. Account Rev 89(2):605–633

Frankel R, Johnson M, Nelson K (2002) The relation between auditors’ fees for nonaudit services and earnings quality. Account Rev 77(Supplement):71–105

Geiger MA, North DS (2006) Does hiring a new CFO change things? An investigation of changes in discretionary accruals. Account Rev 81(4):781–809

Goldschmeid H, Mann H, Weston J (1974) Industrial concentration: the new learning. Columbia University Center for Law and Economic Studies, New York

Government Accountability Office (GAO) (2003) Public accounting firms: mandated study on consolidation and competition. GAO, Washington

Government Accountability Office (GAO) (2008) Audits of public companies: continued concentration in audit market for large public companies does not call for immediate action. GAO, Washington

Gul FA, Fung SYK, Jaggi B (2009) Earnings quality: some evidence on the role of auditor tenure and auditors’ industry expertise. J Account Econ 47:265–287

Higgs J, Skantz T (2006) Audit and nonaudit fees and the market’s reaction to earnings announcements. Audit J Pract Theory 25(1):1–26

Hope OK, Langli JC (2010) Auditor independence in a private firm and low litigation risk setting. Account Rev 85(2):573–605

Hribar P, Collins D (2002) Errors in estimating accruals: implications for empirical research. J Account Res 40(1):105–134

Hribar P, Nichols D (2007) The use of unsigned earnings quality measures in tests of earnings management. J Account Res. 45(5):1017–1053

Hribar P, Kravet T, Wilson R (2014) A new measure of accounting quality. Rev Acc Stud 19:506–538

Jaggi B, Mitra S, Hossain M (2015) Earnings quality, internal control weaknesses and industry-specialist audits. Rev Quant Financ Acc 45:1–32

Jensen K, Kim JM, Yi H (2015) The geography of US auditors: information quality and monitoring costs by local versus non-local auditors. Rev Quant Financ Acc 44:513–549

Jha A, Chen Y (2015) Audit fees and social capital. Account Rev 90(2):611–639

Jones J (1991) Earnings management during import relief investigations. J Account Res 29(2):193–228

Kaplan SE, Williams DD (2013) Do going concern audit reports protect auditors from litigation? A simultaneous equations approach. Account Rev 88:199–232

Kinney W (2005) Twenty-five years of audit deregulation and re-regulation: what does it mean for 2005 and beyond? Audit J Pract Theory 24(Suppl):89–109

Kinney W, Libby R (2002) Discussion of the relation between auditors’ fees for nonaudit services and earnings management. Account Rev 77(Supplement):107–114

Klein B, Leffler K (1981) The role of market forces in assuring contractual performance. J Polit Econ 89:615–641

Kothari K, Leone A, Wasley C (2005) Performance matched discretionary accruals. J Account Econ 39(1):163–197

Krishnan J, Wen Y, Zhao W (2011) Legal expertise on corporate audit committees and financial reporting quality. Account Rev 86(6):2099–2130

Larcker D, Richardson S (2004) Fees paid to audit firms, accrual choices, and corporate governance. J Account Res 42(3):625–658

Lawrence A, Minutti-Meza M, Zhang P (2011) Can Big 4 versus non-Big 4 differences in audit-quality proxies be attributed to client characteristics? Account Rev 86(1):259–286

Lennox C, Li B (2012) The consequences of protecting audit partners’ personal assets from the threat of liability. J Account Econ 54:154–173

Magee R, Tseng M (1990) Audit pricing and independence. Account Rev 65(2):315–336

Menon K, Williams D (2004) Former audit partners and abnormal accruals. Account Rev 79(4):1095–1118

Michas P (2011) The importance of audit profession development in emerging market countries. Account Rev 86(5):1731–1764

Myers LA, Schmidt J, Wilkins M (2014) An investigation of recent changes in going concern reporting decisions among Big N and non-Big N auditors. Rev Quant Financ Acc 43:155–172

Newton N, Wang D, Wilkins M (2013) Does a lack of choice lead to lower quality? Evidence from auditor competition and client restatements. Audit J Pract Theory 32(3):31–67

Numan W, Willekens M (2012) An empirical test of spatial competition in the audit market. J Account Econ 53(1–2):450–465

O’Keefe T, Simunic D, Stein M (1994) The production of audit services: evidence from a major public accounting firm. J Account Res 32:241–261

Oster S (1999) Modern competitive analysis. Oxford University Press, New York

Prawitt DF, Smith J, Wood D (2009) Internal audit quality and earnings management. Account Rev 84(4):1255–1280

Ruddock C, Taylor S, Taylor S (2006) Nonaudit services and earnings conservatism: is auditor independence impaired? Contemp Account Res 23(3):701–746

Scherer F (1996) Industry structure, strategy, and public policy. Harper Collins, New York

Sheth J, Sisodia R (2002) The rule of three. The Free Press, Mankato

Shu S (2000) Auditor resignations: clientele effects and legal liability. J Account Econ 29:173–205

Simunic D (1980) The pricing of audit services: theory and evidence. J Account Res 18(1):161–190

Stiglitz J (1987) Competition and the number of firms in a market: are duopolies more competitive than atomistic markets. J Pol Eco 95(5):1041–1061

US Treasury (2008) Advisory committee on the auditing profession: final report. October 6. http://www.tres.gov/offices/domestic-finance/acap/docs/final-report.pdf

Wang C, Raghunandan K, McEwen R (2013) Non-timely 10-K filings and audit fees. Account Horiz 27(4):737–755

Whisenant S, Sankaraguruswamy S, Raghunandan K (2003) Evidence on the joint determination of audit and non-audit fees. J Account Res 41(4):721–744

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor and two reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank Jong-Hag Choi, Clive Lennox, workshop participants at the University of Texas at San Antonio and the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and attendees at the AAA 2016 Annual Meeting (2016) and the Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics 2017 Symposium for their feedback and suggestions. K. K. Raman acknowledges support from the Ramsdell Endowed Chair for Accounting at The University of Texas at San Antonio.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Audit fee competition (AFCOMP) variable

To estimate AFCOMP (audit fee competition) among Big 4 auditors we estimate the following audit fee model (based on prior research, such as Jha and Chen 2015; Choi et al. 2010; Larcker and Richardson 2004; Simunic 1980; Wang et al. 2013; Whisenant et al. 2003; Antle et al. 2006):

All variables are defined in Appendix 2. The model is estimated separately for each Big 4 auditor, by year and by industry (1-digit SIC code).Footnote 15 Next, we use the model parameters to estimate the counterfactual audit fee that each Big 4 auditor (other than the incumbent) would charge, holding client and auditor characteristics constant (with the exception of TENURE which is set = 0) for the client in question. Audit fee (AFEE) is then calculated as the exponential of LAFEE. We then compare the incumbent Big 4 auditor’s AFEE with the counterfactual AFEE for each of the other three Big 4 auditors. Then AFCOMP = the incumbent’s AFEE minus the lowest counterfactual AFEE for any other Big 4 auditor, deflated by client total assets.Footnote 16 See Fig. 1 for more information. Then, AFCOMP_POS = AFCOMP for AFCOMP > 0, and 0 otherwise (see Panel A) and AFCOMP_NEG = AFCOMP for AFCOMP < 0, and 0 otherwise (see Panel B).

Since it is not practical to present 352 regressions (4 Big 4 auditors × 11 years × 8 industries), in Appendix 3 we present the pooled versions of each of the four Big 4 firm regressions with fixed-effects for years and industries. We also compare the coefficients of each of the Big 4 firm regressions taken as a set as well as individually. The 6 Chow tests comparing the 4 sets of coefficients with each other show that all of them are significantly different at 1% level with the F values ranging from 3.89 to 5.37. We also compare the 27 individual coefficients (6 × 27 independent variables = 162 tests). Of these 162 tests, 124 are significant at 10% or better which suggests that the audit fee pricing models of the Big 4 are significantly different from each other, i.e., the audit fees charged by them for any individual client is likely to be significantly different from each other.

In Fig. 1, each Big 4 line represents the audit fee model (see Appendix 1) for each of the four Big 4 firms, including the incumbent Big 4 firm. Point XC on the X-axis represents the client-specific audit fee model vector of the independent variables in the fee model for client C for a particular year. For client C, the lowest counterfactual fee is from Big 4 firm 3. Hence, variable AFCOMP_POS (NEG) is equal to the incumbent’s audit fee minus the counterfactual audit fee of the Big 4 firm 3, deflated by client total assets and can be positive or negative (as depicted in the two panels).

Appendix 2: Variable definitions

Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

Dependent variables | |

DACC | Performance adjusted discretionary accruals calculated using the modified Jones model (DeFond and Jiambalvo 1994) controlling for concurrent performance based on 2-digit SIC code and year (Kothari et al. 2005), deflated by beginning of fiscal year total assets. We use the difference between net income and cash from operations as our measure of total accruals (Hribar and Collins 2002). The higher the DACC, the lower the quality of audited earnings and the lower the implied audit quality |

MBEX | A dichotomous variable equal to 1 if the firm meets or beats the earnings expectation (proxied by the most recent median consensus analyst forecast available on IBES file) by one cent or less; 0 otherwise. The higher the probability of MBEX, the lower the quality of audited earnings and the lower the implied audit quality |

PROFIT | Dichotomous variable equal to 1 if the net income before extraordinary items and cumulative effect of accounting changes deflated by lagged total assets is between 0 and 5%; 0 otherwise (Francis and Yu 2009). The higher the probability of PROFIT, the lower the quality of audited earnings and the lower the implied audit quality |

GCOPN | Dichotomous variable equal to 1 if the client receives a going concern opinion in the current year; 0 otherwise. The higher the probability of GCOPN, the higher the implied audit quality |

Test variables | |

AFCOMP | Audit fee competition among Big 4 auditors measured as the incumbent Big 4 firm’s actual audit fee minus the lowest counterfactual fee from another Big 4 firm (which may or may not have an office in the local audit market) deflated by the client’s total assets. The counterfactual fee is based on cross-sectional audit fee regressions run by year, by industry (1 digit SIC code), and by each Big 4 auditor, controlling for client-specific, local audit office-specific, and local audit market-specific factors |

AFCOMP_POS | Equals AFCOMP for AFCOMP > 0 and 0 otherwise |

AFCOMP_NEG | Equals AFCOMP for AFCOMP < 0 and 0 otherwise |

Control variables | |

ACQUIRE | A dichotomous variable equal to 1 if the client is involved in acquisition activities during the year; and 0 otherwise |

B2M | Book-to-market equity ratio at the end of the fiscal year |

BUSY | Dummy variable equal to 1 for December 31st fiscal-year-end clients; 0 otherwise |

CASSET | Ratio of current assets to total assets |

CFFO | Cash flow from operations divided by total assets |

DISTANCE | Spatial distance metric (based on Numan and Willekens 2012) defined as the absolute fee market share difference between the incumbent Big 4 auditor and closest Big 4 competitor in the local industry audit market fiscal year. A local industry audit market consists of all companies within a two-digit SIC code in a CBSA. The lower the metric, the higher the competition in the local industry audit market. |

EGROWTH | Annual growth rate of net income before extraordinary items and cumulative effect of accounting changes |

FINANCE | A dichotomous variable equal to 1 if number of outstanding shares increased by at least 10% or long-term debt increased by at least 20% during the year (Geiger and North 2006); and 0 otherwise |

FOPS | Proportion of a client’s total income from foreign (non-US) operations |

FSCORE | Fraud Score calculated using Dechow et al. (2011) methodology on page 55 (Table 7, Panel A, Model 1) |

HERF | Herfindahl index (concentration measure) for local industry audit market fiscal year, where a local industry audit market consists of all public clients within a two-digit SIC group in a CBSA. Defined as Σ[s/S]2, where “s” is the sum of audit fees of the Big 4 audit office from all clients within the 2-digit SIC industry, and “S” is the total audit fees of all Big 4 auditors in the CBSA from all clients in that industry (Numan and Willekens 2012) |

ICMW | Number of material internal control weaknesses reported in Audit Analytics |

INDSP | Measure of industry specialization, defined as a dichotomous variable equal to 1 when an audit firm has a fee market share of at least 30% in an audit market, 0 otherwise. An audit market is defined as a two-digit SIC industry in a CBSA (Numan and Willekens 2012) |

INVRATIO | Inventory deflated by total assets |

LAFEE | Natural log of audit fee during the current fiscal year |

LDELAY | Natural log of 1 plus the number of calendar days from fiscal year-end to the date of the audit report |

LEADER | An indicator variable equal to1 when an audit firm has the largest fee market share in an audit market, 0 otherwise. An audit market is defined as a two-digit SIC industry in a CBSA (Numan and Willekens 2012) |

LEV | Long term debt plus debt in current liabilities deflated by average total assets (Lawrence et al. 2011) |

LNAFEE | Natural log of non-audit fees during the current fiscal year |

LNUMEST | Natural log of the number of analysts’ forecasts |

LOFFICE | Natural log of total annual audit fees of the local office of the incumbent Big 4 auditor (Francis and Yu 2009) |

LSIZE | Natural log of the client’s total assets (in millions of dollars) |

MODOP | A dichotomous variable equal to 1 if the audit opinion is modified (different from the standard three paragraph report); 0 otherwise |

PINTAN | Proportion of intangible assets to total assets |

REL_AC_CFO | Power of the audit committee relative to CFO as defined on page 2065 of Beck and Mauldin (2014) |

ROA | Net income before extraordinary items and cumulative effect of accounting changes deflated by total assets |

SDCFFO | Standard deviation of cash flow from operations deflated by total assets, calculated over the current and prior four years |

SDEARN | Standard deviation of earnings deflated by total assets, calculated over the current and prior 4 years |

SDSALES | Standard deviation of sales deflated by total assets, calculated over the current and prior 4 years |

SEGMENTS | Number of segments reported in Compustat segment file |

STDEST | Standard deviation of analysts’ earnings forecasts |

TENURE | Number of years the client has been with the current auditor |

Appendix 3: Big 4 audit fee models (dependent variable = LAFEE)

Variables | Deloitte | EY | KPMG | PWC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Estimate | p value | Estimate | p value | Estimate | p value | Estimate | p value | |

Intercept | 8.7539*** | < 0.0001 | 7.0932*** | < 0.0001 | 7.8903*** | < 0.0001 | 7.5844*** | < 0.0001 |

Client-specific variables | ||||||||

LSIZE | 0.5156*** | < 0.0001 | 0.4393*** | < 0.0001 | 0.4964*** | < 0.0001 | 0.4668*** | < 0.0001 |

ROA | − 0.5378*** | < 0.0001 | − 0.5381*** | < 0.0001 | − 0.5740*** | < 0.0001 | − 0.4686*** | < 0.0001 |

CFFO | − 0.4594*** | 0.0004 | 0.1910** | 0.0303 | 0.0415 | 0.7082 | − 0.0929 | 0.3631 |

B2M | − 0.0888*** | 0.0002 | − 0.0093 | 0.6479 | − 0.0734*** | 0.0015 | − 0.0247 | 0.2342 |

LEV | 0.1357** | 0.0357 | 0.1527*** | 0.0015 | 0.2091*** | 0.0005 | 0.2474*** | < 0.0001 |

CASSET | 0.6581*** | < 0.0001 | 0.4565*** | < 0.0001 | 0.9066*** | < 0.0001 | 0.7136*** | < 0.0001 |

INVRATIO | − 0.1055 | 0.2466 | 0.1066 | 0.1551 | 0.1090 | 0.2460 | 0.1561* | 0.0635 |

SEGMENTS | 0.0205*** | < 0.0001 | 0.0206*** | < 0.0001 | 0.0282*** | < 0.0001 | 0.0230*** | < 0.0001 |

FOPS | 0.2873*** | < 0.0001 | 0.2962*** | < 0.0001 | 0.3029*** | < 0.0001 | 0.3101*** | < 0.0001 |

ACQUIRE | − 0.0020 | 0.9325 | 0.0033 | 0.8660 | 0.0592*** | 0.0091 | 0.0553*** | 0.0040 |

FINANCE | 0.0267 | 0.2010 | 0.0188 | 0.2486 | 0.0165 | 0.3930 | − 0.0089 | 0.5953 |

PINTAN | 0.4407*** | < 0.0001 | 0.4017*** | < 0.0001 | 0.4440*** | < 0.0001 | 0.1260** | 0.0138 |

REL_AC_CFO | 0.0175** | 0.0124 | − 0.0053 | 0.3129 | − 0.0023 | 0.7178 | − 0.0119 | 0.3290 |

FSCORE | 0.0067 | 0.4265 | 0.0176* | 0.0486 | 0.0026 | 0.7905 | 0.0059 | 0.4936 |

Auditor-specific variables | ||||||||

TENURE | 0.0058*** | < 0.0001 | 0.0044*** | < 0.0001 | − 0.0014 | 0.1881 | 0.0054*** | < 0.0001 |

INDSP | − 0.0203 | 0.4257 | 0.0609*** | 0.0006 | − 0.0314 | 0.2556 | 0.0779*** | 0.0002 |

LOFFICE | 0.0560*** | < 0.0001 | 0.0914*** | < 0.0001 | 0.0628*** | < 0.0001 | 0.0624*** | < 0.0001 |

LDELAY | 0.0777* | 0.0521 | 0.2530*** | < 0.0001 | 0.1757*** | < 0.0001 | 0.1983*** | < 0.0001 |

LNAFEE | 0.0361 | < 0.0001 | 0.0751 | < 0.0001 | 0.0628 | < 0.0001 | 0.0771 | < 0.0001 |

MODOP | 0.0440* | 0.0685 | 0.0798*** | 0.0001 | 0.0558** | 0.0178 | 0.1148*** | < 0.0001 |

ICMW | 0.1597*** | < 0.0001 | 0.2268*** | < 0.0001 | 0.1440*** | < 0.0001 | 0.0787*** | 0.0001 |

BUSY | 0.0343* | 0.0895 | 0.0540*** | 0.0007 | 0.0021 | 0.9115 | 0.0883*** | < 0.0001 |

Audit market − specific variables | ||||||||

HERF | − 0.3125 | 0.4133 | 0.4207*** | < 0.0001 | − 0.2471 | 0.4018 | 0.2196*** | 0.0079 |

DISTANCE | 0.1057 | 0.2662 | − 0.1298 | 0.2789 | 0.2419*** | 0.0003 | 0.0910 | 0.1825 |

LEADER | 0.0514** | 0.0273 | − 0.0128 | 0.4277 | − 0.0212 | 0.3377 | − 0.0272 | 0.1984 |

Information environment-specific variables | ||||||||

LNUMEST | − 0.0908*** | < 0.0001 | − 0.0619*** | < 0.0001 | − 0.0605*** | < 0.0001 | − 0.0450*** | < 0.0001 |

STDEST | 0.0126 | 0.8706 | 0.1236** | 0.0264 | 0.2650*** | 0.0062 | 0.1791** | 0.0113 |

Year dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

Observations | 2611 | 4062 | 2701 | 3244 | ||||

Adj-R square | 0.7999 | 0.7945 | 0.8226 | 0.8496 | ||||

F value | 261.77 | 393.45 | 313.96 | 459.02 | ||||

Probability > F | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Asthana, S., Khurana, I. & Raman, K.K. Fee competition among Big 4 auditors and audit quality. Rev Quant Finan Acc 52, 403–438 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-018-0714-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-018-0714-9