Abstract

Purpose

During the first SARS-CoV-2-infection wave, a deterioration in emotional well-being and increased need for mental health care were observed among patients treated or being treated for breast cancer. In this follow-up study, we assessed patient-reported quality of life (QoL), physical functioning, and psychosocial well-being during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave in a large, representative cohort.

Methods

This longitudinal cohort study was conducted within the prospective, multicenter UMBRELLA breast cancer cohort. To assess patient-reported QoL, physical functioning and psychosocial well-being, COVID-19-specific surveys were completed by patients during the first and second SARS-CoV-2-infection waves (April and November 2020, respectively). An identical survey was completed by a comparable reference population during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection waves. All surveys included the validated EORTC-QLQ-C30/BR23, HADS and “De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness” questionnaires. Pre-COVID-19 EORTC-QLQ-C30/BR23 and HADS outcomes were available from UMBRELLA. Response rates were 69.3% (n = 1106/1595) during the first SARS-CoV-2-infection wave and 50.9% (n = 822/1614) during the second wave. A total of 696 patients responded during both SARS-CoV-2-infection waves and were included in the analysis comparing patient-reported outcomes (PROs) during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave to PROs during the first wave. Moreover, PROs reported by all patients during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave (n = 822) were compared to PROs of a similar non-cancer reference population (n = 241) and to their pre-COVID-19 PROs.

Results

Patient-reported QoL, physical functioning, and psychosocial well-being of patients treated or being treated for breast cancer remained stable or improved from the first to the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave. The proportion of emotional loneliness reduced from 37.6 to 29.9% of patients. Compared to a similar non-cancer reference population, physical, emotional, and cognitive functioning, future perspectives and symptoms of dyspnea and insomnia were worse in patients treated or being treated for breast cancer during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave. PROs in the second wave were similar to pre-COVID-19 PROs.

Conclusion

Although patients scored overall worse than individuals without breast cancer, QoL, physical functioning, and psychosocial well-being did not deteriorate between the first and second wave. During the second wave, PROs were similar to pre-COVID-19 values. Overall, current findings are cautiously reassuring for future mental health of patients treated or being treated for breast cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The World Health Organization declared the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak a pandemic on March 11, 2020 [1, 2]. Due to the immediate high burden on healthcare systems, adapted cancer treatment protocols were implemented rapidly [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. A subsequent temporary disruption in breast cancer screening programs[12, 13], changed referral patterns and changed attitudes toward health care consumption [3, 4, 14] contributed to a sharp decrease in breast cancer diagnoses in 2020 [12, 15]. In response to the dropping cancer diagnoses and abrupt changes in cancer care, increased concerns and anxiety about the consequences of delay and discontinuation of screening, diagnosis, and treatment were observed among cancer patients [2, 14, 16,17,18].

The unpredictable course of the viral spread still provides an uncertain prospect toward the future for patients [19, 20]. Despite governmental efforts, including social restrictions and rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines, the global pandemic continues to affect daily life through mutant variants of the virus [21]. It is estimated that the current pandemic is likely to last for years, and that social restrictions should not be discarded completely before 2024 due to possible resurgence in contagion [22].

Regardless of a pandemic, patients with currently active or a history of breast cancer have an increased risk of impaired mental health compared to individuals without cancer [23, 24]. As long-term consequences of adverse mental health among breast cancer patients may result in poorer treatment adherence, impaired prognosis and survival, and higher barriers to returning to work [25,26,27,28,29], the pandemic could result in unforeseen long-term adverse effects [30].

During the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, a deterioration in emotional well-being and an increased need for mental health care were already observed among breast cancer patients [3, 4, 8, 31]. In our previous study [3], conducted amidst the first SARS-CoV-2-infection wave, we observed a substantial drop in emotional and social functioning among breast cancer survivors, and one in two experienced loneliness. However, initial emotional response could stabilize or diminish after patients adjust to a certain situation [32]. As previously described during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, psychological effects of a viral pandemic can last until 30 months after its onset [33]. Therefore, it is important to understand and monitor the long-term effects of the lingering COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health in patients with breast cancer [3, 32, 34].

The aim of this follow-up study was to assess patient-reported quality of life (QoL), physical functioning, and psychosocial well-being in a large prospective cohort of breast cancer patients during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave. For context, we compared patient-reported outcomes (PROs) measuring QoL, physical functioning, and psychosocial well-being during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave to (1) PROs of the same population during the first SARS-CoV-2-infection wave, (2) PROs of a similar non-cancer reference population, and (3) their own pre-COVID-19 PROs.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This study was conducted within the prospective, multicenter ‘Utrecht cohort for Multiple BREast cancer intervention studies and Long-term evaluAtion’ (UMBRELLA) [35]. From October 2013 onward, UMBRELLA has been including patients diagnosed with breast cancer in one of six regional hospitals and referred for radiation therapy to the department of Radiation Oncology of the University Medical Center Utrecht. All patients with breast cancer meeting the broad inclusion criteria are invited for participation in UMBRELLA prior to the start of radiation therapy. Inclusion criteria are histologically proven invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), having an age ≥ 18 years, sufficient written and spoken understanding of the Dutch language and the absence of mental impairment. All participants provided informed consent for longitudinal collection and use of clinical data and PROs through paper or online questionnaires at regular intervals up to 10 years, i.e., prior to radiation therapy (baseline), after 3 and 6 months, and each 6 months thereafter [35]. Clinical data are routinely provided and updated by the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR) [36].

The UMBRELLA study adheres to the Dutch Law on Medical Research Involving Human Subjects (WMO) and the Declaration of Helsinki (version 2013). The study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee (MREC) Utrecht (NL52651.041.15, MEC15/165) and is registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02839863).

Data collection

UMBRELLA participants were invited to complete two consecutive online COVID-19-specific surveys at the height [37] of the first and second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave in the Netherlands, i.e., 6 weeks and nine months, respectively, after the COVID-19 outbreak on February 27, 2020 [15]. Participants received the first survey on April 7, 2020, and the second survey on November 4, 2020. A reminder was sent after two weeks in case of non-response. Only patients who opted for online questionnaires were eligible for participation in this study. During both peaks, similar governmental restrictions and health care measures, as described in our previous paper [3], were in place in the Netherlands, with the exemption of the national breast cancer screening program, which was resumed two months before the second survey was sent [38].

The COVID-19-specific surveys included three validated questionnaires for the assessment of patient-reported QoL, physical functioning, and psychosocial well-being; the European Organization for Research and Treatment (EORTC) core (C30) and breast cancer-specific (BR23) Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ)[39]; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)[40]; and the De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale [41], complemented by COVID-19-related questions. The COVID-19-related questions were developed by clinical experts and epidemiologists and focused on the presence of COVID-19 and health care consumption (Supplementary Table 1).

Patient-reported QoL, future perspectives, physical, role, emotional, social, and cognitive functioning, symptoms of dyspnoea and insomnia and financial difficulties were assessed with the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and -BR23 questionnaires [39]. For each one to five item subscale, a summary score ranging from 0 to 100 was calculated [42]. Higher scores on the QoL, future perspectives, and functional subscales indicate better outcomes, whereas higher scores on the symptom and financial difficulties subscales indicate worse outcomes. The EORTC-QLQ-C30 and -BR23 scales are considered reliable measures of patient-reported QoL of breast cancer patients [39, 43,44,45]. Clinical relevance of the mean scores was determined according to previously published thresholds according to EORTC-guidelines, and the clinical relevance of differences between scores were determined according to previously published minimally clinically important differences (MIDs) [46,47,48,49].

Symptoms of anxiety and depression were assessed with the 14-item HADS questionnaire, which includes two 7-item subscales for anxiety and depression [40]. Summary scores range from 0 to 21 on each subscale [50]. A higher score represents a higher risk of symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. Scores > 11 on the total HADS scale and scores > 7 on the two subscales represent clinically relevant symptoms of anxiety and/ or depression [51,52,53,54]. The HADS has shown a high reliability among different Dutch populations [50]. Breast cancer-specific MIDs for the HADS are yet to be developed [55].

Feelings of loneliness were assessed with the six-item scale of the De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale questionnaire [41]. This short scale consists of two 3-item subscales for emotional loneliness and social loneliness. On the total scale, a score of 0–1 represents the absence of loneliness, 2–4 moderate loneliness and 5–6 severe loneliness [56]. On the subscales, a score of 0–1 indicates no emotional/social loneliness and 2–3 emotional/social loneliness. The De Jong-Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness are considered highly reliable measures for loneliness in the Dutch population [57].

Clinical data, as collected in the context of UMBRELLA or retrieved by the NCR[36], included age at cohort inclusion, sex, body mass index (BMI), highest educational level, type of surgery, (neo-)adjuvant radiation and systemic therapy, and pathological T-stage (AJCC 7th/8th edition).

Similar reference population without cancer

During the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave, a similar (i.e., individuals with a similar socio-economic status) and non-cancer reference population was invited to complete all relevant questions of the COVID-19-specific survey. For this purpose, all UMBRELLA participants who received the second COVID-19-specific survey were asked to invite an acquaintance (e.g., friends, colleagues, relatives, or neighbors) to complete a similar online survey. The link to this survey and the accompanying online patient information folder was added to the invitation to the UMBRELLA-participant. This enabled the UMBRELLA-participant to forward this link to the acquaintance. The survey did not include personal identifiable data. All non-cancer individuals who completed the online form provided informed consent to participate. Inclusion criteria for the reference population were as follows: same gender, age within a five-year age range from the participants’ age. Exclusion criteria were a history of or currently diagnosed cancer and completion of < 100% of the survey. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were communicated to the UMBRELLA-participant who forwarded the link and were verified through the survey.

Pre-COVID-19 PROs

PROs of responders during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave were compared to their pre-COVID-19 PROs. The pre-COVID-19 EORTC-QLQ-C30/BR23 and HADS scores were available from UMBRELLA and were derived from regular UMBRELLA questionnaires that were completed in the year before the first COVID-19 diagnosis in the Netherlands on February 27, 2020 [15].

To adjust for differences in follow-up distribution among responders pre-COVID-19 and during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave, pre-COVID-19 PROs were weighted for follow-up since cohort inclusion. This is important, as previous studies have shown that physical functioning and psychosocial well-being are expected to gradually improve during the first years after breast cancer diagnosis, independent of a pandemic [3]. Follow-up was divided into four categories, and the following statistical weights were assigned for each subgroup to match the follow-up distribution during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave: 0.42 for a follow-up < 1 year, 1.56 for a follow-up between 1–2 years, 1.01 for a follow-up between 3 and 5 years, and 2.99 for a follow-up > 5 years.

Statistical analysis

Frequencies and proportions, means with range and standard deviation (SD), or medians with range or interquartile range (IQR) were used to describe baseline characteristics of non-responders, responders, and the non-cancer reference population, as well as unadjusted mean EORTC-QLQ-C30/BR23, HADS and De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale scores during the first and second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave.

Three main comparisons are to be distinguished. First, unadjusted mean EORTC-QLQ-C30/BR23 scores were compared between the first and second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave using the paired t-test, unadjusted median HADS scores with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, the proportion of loneliness on the De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale with the McNemar-Bowker test, and proportions of emotional and social loneliness with the McNemar test. All analyses were performed on complete cases, i.e., those who completed the survey during the first and second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave.

Second, unadjusted mean PROs of all responders during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave were compared to unadjusted mean PROs of the non-cancer reference population using the independent samples T-test for the mean EORTC-QLQ-C30/BR23 scores and Mann–Whitney U-test for the median HADS scores. The Chi-square test was used to assess the differences in proportions on the De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale.

Third, mean PROs of responders during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave were compared to their weighted mean pre-COVID-19 PROs. Only complete cases on each individual EORTC-QLQ-C30/BR23 and HADS subdomain (i.e., those who completed the survey during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave and pre-COVID-19) were compared according to known MIDs [47,48,49]. Not all subdomains of the pre-COVID-19 questionnaire were completed by each participant. This resulted in varying sample sizes per subdomain of each questionnaire for this comparison.

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, PROs of patients under active treatment were affected more than PROs of patients without active treatment (i.e., those in follow-up) [3]. Therefore, we additionally assessed differences in the proportion of patients with clinically relevant impairment on the different QoL domains in patients with and without active treatment separately between the first and second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave using the McNemar test.

All reported p-values were two-sided. Because of multiple testing, p-values < 0.01 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences software, version 26 (SPSS; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

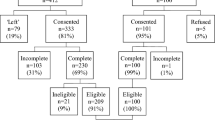

Between October 2013 and April 2020, 3239 patients were enrolled in UMBRELLA (Fig. 1). Of those, 1595 patients were eligible for receiving the COVID-19-specific survey during the first SARS-CoV-2-infection wave. By November 2020, 3364 patients were enrolled in UMBRELLA, of whom 1614 met the inclusion criteria for the second COVID-19-specific survey. Response rates were 69.3% (n = 1106) during the first SARS-CoV-2-infection wave, and 50.9% (n = 822) during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave.

In total, 696 patients responded to both COVID-19-specific surveys (Fig. 1). Mean age of responders to both surveys was 56 years (range = 29–79, SD = 9.2) and mean BMI was 26.1 (SD = 4.7, Table 1). Median follow-up was 31 months (range = 1–85). The majority were diagnosed with a pathological T1-stage tumor (n = 401, 57.6%) and treated with breast conserving surgery (n = 555, 79.7%) and (loco)regional radiation therapy (n = 631, 90.7%). Most responders (n = 554, 79.6%) were living with a partner and/or child(ren), and 25.6% (n = 178) had received mental healthcare support since diagnosis. During both waves, baseline characteristics of resp

onders and non-responders were comparable (Supplementary Table 2).

The non-cancer reference population included 241 individuals without currently active or a history of cancer with a mean age of 58 years (range = 31–82, SD = 9.2, Table 1). The majority (n = 190, 78.9%) were living with their partner and/or child(ren). Baseline characteristics of the reference population were similar to the responders of both surveys regarding age, sex, BMI, educational level, and current living situation (Table 1).

The number of responders to the survey during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave who had also completed the pre-COVID-19 survey varied per questionnaire and per subdomain, resulting in a population of 664–729 participants depending on the subdomain (Table 4).

The second vs the first SARS-CoV-2-infection wave

In comparison with the first SARS-CoV-2-infection wave, the mean score for emotional functioning improved from 78.4 (SD = 17.0) to 81.4 (SD = 17.5) in the second wave (p < 0.001, Table 2). According to established MIDs [47, 48], these mean differences (MDs) were not clinically meaningful. No other statistically significant or clinically important differences were observed in unadjusted mean EORTC-QLQ-C30/BR23 scores from the first to the second wave.

HADS subscores improved 1 point from the first to the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave (all p < 0.001). The proportion of patients feeling emotionally lonely decreased from 37.6% (n = 262) to 29.9% (n = 208, p < 0.001, Table 2). No statistically significant differences were found in social loneliness between the first and second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave.

Patients vs the non-cancer reference population during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave

During the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave, patients treated or being treated for breast cancer scored statistically significantly worse than the non-cancer and similar reference population on all EORTC-QLQ-C30/BR23 domains, except for financial difficulties (Table 3). When considering known MIDs[47, 48], patient-reported future perspectives (MD = 7.8), physical (MD = 5.0), emotional (MD = 5.2), and cognitive functioning (MD = 9.0), dyspnoea (MD = 5.6), and insomnia (MD = 7.9) seemed to reflect clinically relevant differences, all favoring the non-cancer reference population.

No statistically significant differences were found between patients and the reference population regarding anxiety and depression (HADS), nor regarding the proportion experiencing social, emotional, or overall loneliness.

The second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave vs pre-COVID-19

When compared to pre-COVID-19, emotional functioning (MD = 3.2) showed the largest deterioration during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave (Table 4). None of the MDs for the EORTC-QLQ-C30/BR23 subdomains seemed of clinical importance.

In comparison to pre-COVID-19, the HADS showed one point decrease in all subdomains during the second wave.

Patients with clinically relevant impairment of PROs during the first and second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave

When comparing the first to the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave, no statistically significant differences were observed in the proportion of patients with clinically relevant impairment of PROs (data not shown). Also, in stratified analyses by active or no active treatment at the time of completing the COVID-19-specific surveys, no statistically significant differences in the proportion of patients with clinically relevant impairment of PROs were found (Supplementary Table 3). Overall, when comparing patients with (n = 175) and without (n = 417) active treatment, patients with active treatment showed higher proportions of clinically relevant impairment on all EORTC-QLQ-C30/BR23 and HADS domains than patients without active treatment during both SARS-CoV-2-infection waves.

Discussion

This large prospective observational study observed several clinically important and reassuring findings concerning the impact of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic on patient-reported QoL, physical functioning, and psychosocial well-being among breast cancer patients up to nine months since onset. From the first to the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave, emotional functioning, and symptoms of anxiety and depression improved, while all other QoL scores remained stable. Also, the proportion of patients experiencing emotional loneliness decreased from 37.6 to 29.9%. However, during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave, patients treated or being treated for breast cancer still scored worse on all QoL domains in comparison with a similar non-cancer reference population of similar age, except for financial difficulties. When comparing PROs during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave to pre-COVID-19 PROs, outcomes were largely similar.

In accordance with our findings, previous studies observed a worldwide increase in anxiety and depression among breast cancer patients and survivors during the first months of the pandemic [31, 34, 58,59,60]. Fortunately, we observed no further clinically meaningful deterioration on all QoL-subdomains, anxiety or depression among breast cancer patients nine months after the onset of the pandemic. Moreover, the proportion of patients with clinically relevant impairment on the different QoL-subdomains did not change statistically significantly from the first to the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave.

Emotional functioning and emotional loneliness improved between the first and second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave, and lower levels of anxiety and depression were observed. Independent of a pandemic, gradual increases in physical functioning and psychosocial well-being and QoL are generally observed over time during the first years after diagnosis among patients treated or being treated for breast cancer [3, 61]. However, as mean follow-up of our study population was 31 months, our cohort was likely to have reached a plateau in which this improvement in mental well-being has naturally stabilized [62,63,64]. Moreover, whether emotional functioning (MD = 3.0) improved to a clinically relevant extent is debatable. A small MID has previously been estimated at MD > 5–10[49, 63, 65]; however, a breast cancer-specific MID for emotional functioning has yet to be established [47, 48].

Similar to our findings, Rentscher and colleagues [66] found an increase in loneliness among breast cancer survivors during the first months of the pandemic in comparison with pre-COVID-19, and no difference in loneliness compared to matched controls. Likewise, a Dutch study [24] observed increased loneliness among cancer patients and their family members during the first SARS-CoV-2-infection wave. From the first to the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave, we observed a decrease in the proportion of patients reporting moderate to severe overall loneliness from 47.7 to 42.0%, which was also comparable to our non-cancer reference population. Nonetheless, these proportions are still substantially higher than the previously published 34% of individuals experiencing loneliness in a general Dutch population of comparable age in 2019, pre-COVID-19 [67].

COVID-19 has an especially large impact on the mental health of individuals with currently active or a history of cancer when compared to similar and non-cancer reference individuals [68]. A large American study showed that, shortly after the COVID-19 outbreak, cancer survivors were more likely to feel anxious, depressed and lonely than adults without cancer [69]. Nine months after the onset of the pandemic patients still scored worse than the non-cancer reference population on all QoL-subdomains, however, we did not observe differences in anxiety, depression, and loneliness. Based on known MIDs [47, 48], the observed differences for patient-reported QoL, financial difficulties, social, role, and physical functioning would be considered clinically trivial, and differences for emotional and cognitive functioning, dyspnea and insomnia of small clinical relevance [47, 48]. No breast cancer-specific MID has been established yet for the subdomain future perspectives [47, 48], but based on the established MID for future perspectives among multiple myeloma patients, an MD < 10 would not be considered clinically meaningful [70]. Several pre-COVID-19 studies showed that, regardless of a pandemic, breast cancer patients have a higher risk of worse mental health and cognitive issues than non-cancer individuals [23, 71]. Therefore, the observed differences with small clinical relevance are most likely explained by the treatment of the disease and/or the disease itself rather than the COVID-19 pandemic.

When compared to pre-COVID-19, PROs during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave provided reassuring perspective, as all observed differences in EORTC-QLQ-C30/BR23 scores between pre-COVID-19 and the second wave were estimated clinically trivial [47, 49, 70]. No breast cancer-specific MIDs for the HADS have been established yet [55], however, based on the MIDs for the HADS among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[72], the differences in HADS scores would also not be considered clinically meaningful. Thus, the previously observed deterioration in psychosocial well-being during the first SARS-CoV-2-infection [3] wave could likely have reflected a temporal effect of the pandemic, as most QoL domains seemed to return to pre-COVID-19 levels during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave. As such, it seems that participants adjusted to the new situation and learned to live through a pandemic.

To date, herd immunity, effectiveness of vaccines and SARS-CoV-2-infection control measures have improved, resulting in dropping hospitalization and mortality rates due to SARS-CoV-2-infection [73, 74]. While this has likely reduced levels of anxiety toward contracting SARS-CoV-2-infection, the pandemic continues to cause concerns about its long-term effects. For example, the effectiveness of vaccines beyond six months is still unclear [73], and it has been reported that women older than 20 years, and thus, the vast majority of breast cancer patients are more likely to develop at least one out of the three ‘Long COVID’ symptoms, including persistent fatigue with bodily pain or mood swings, ongoing respiratory problems, or cognitive problems [75].

Since the start of the pandemic, there has been extra attention for the mental health of breast cancer patients through the implementation of various e-mental-health projects [76,77,78]. Although improved over time, emotional functioning of breast cancer patients was still lower during the second wave than pre-COVID-19 and lower when compared to non-cancer individuals. Consequences of decreased emotional functioning should not be underestimated. Impaired mental health in breast cancer patients is associated with poorer treatment compliance and might thereby negatively affect survival [29, 34, 79]. As such, long-term effects of the current COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of breast cancer patients should continue to be monitored to minimize adverse effects of the pandemic in the future [16, 68, 79, 80]. Moreover, previous studies have shown that social isolation and the lack of emotional support from family and friends are associated with higher risk of mortality [81, 82]. For current clinical practice and beyond an apparent end of the pandemic, it is therefore strongly advised to (further) develop and implement e-mental health applications and psychosocial interventions, aiming to improve mental health of this vulnerable population that is reported to be uniquely at risk for experiencing emotional distress [2, 31].

This study has some limitations. First, although baseline characteristics of responders and non-responders were comparable during both infection waves, an under- or overestimation of the results due to selective (non-)response could not be ruled out as the reasons for non-response were unclear. Second, only participants who had opted to complete online surveys were eligible for this study. Participants who opted for paper surveys were excluded, possibly resulting in some degree of selection bias. Third, although baseline characteristics, and thus, socio-economic status, of the reference population were similar to our UMBRELLA participants, the reference population might still have been subject to some degree of selection bias, as all reference individuals were directly or indirectly faced with the impact of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment through the related UMBRELLA-participant. Last, the results of this study represent PROs during the first and second SARS-CoV-2-infection peaks in the Netherlands and might therefore be subject to fluctuations that follow the severity of the infection peaks. An important strength of this study is that this is the first longitudinal study to evaluate the course of PROs in patients treated or being treated for breast cancer from pre-COVID-19 until the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave. The ongoing collection of clinical data and PROs within UMBRELLA allows for future analyses with successive PROs during and after consecutive SARS-CoV-2-infection waves to monitor the impact of the pandemic and its subsequent social measures on physical functioning and psychosocial well-being of breast cancer patients and survivors, aiming to support nationwide preventive and curative mental health care programs.

Conclusions

Despite the lingering COVID-19 pandemic, patient-reported QoL, physical functioning and psychosocial well-being in individuals treated or being treated for breast cancer did not deteriorate between the first and second SARS-CoV-2-infection waves. Emotional functioning, anxiety, and depression slightly improved, and the proportion of patients experiencing emotional loneliness decreased. Compared to a similar and non-cancer reference population, individuals treated or being treated for breast cancer still scored clinically meaningfully worse for patient-reported physical, emotional, and cognitive functioning, future perspectives, dyspnea, and insomnia nine months after the COVID-19 outbreak. However, in comparison with pre-COVID-19, no clinically meaningful differences were found during the second SARS-CoV-2-infection wave.

Data availability

The data underlying this article, including individual de-identified participant data and a data dictionary defining each field in the set, will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AJCC:

-

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- COVID-19:

-

COronaVIrus Disease 2019

- DCIS:

-

Ductal carcinoma in situ

- EORTC-QLQ-C30/BR23:

-

European Organization for Research and Treatment core and breast cancer-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- MID:

-

Minimally Clinically Important Difference

- MD:

-

Mean difference

- MREC:

-

Medical Research Ethics Committee

- NCR:

-

Netherlands Cancer Registry

- No.:

-

Number

- PROs:

-

Patient-reported outcomes

- QoL:

-

Quality of Life

- Resp.:

-

Respectively

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- UMBRELLA:

-

Utrecht cohort for Multiple BREast cancer intervention studies and Long-term evaluation

- UMCU:

-

University Medical Centre Utrecht

References

World Health Organization (WHO). (2020, Mar 11). WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. Retrieved July 19, 2021, from https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-mediabriefing-on-covid-19-11-march-2020.

Ludwigson, A., Huynh, V., Myers, S., Hampanda, K., Christian, N., Ahrendt, G., Romandetti, K., & Tevis, S. (2022). Patient perceptions of changes in breast cancer care and well-being during COVID-19: A mixed methods study. Annals of Sugical Oncology., 29(3), 1649–57.

Bargon, C. A., Batenburg, M. C. T., van Stam, L. E., van der Molen, D. R. M., van Dam, I. E., van der Leij, F., Baas, I. O., Ernst, M. F., Maarse, W., Vermulst, N., Schoenmaeckers, E. J. P., van Dalen, T., Bijlsma, R. M., Young-Afat, D. A., Doeksen, A., & Verkooijen, H. M. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patient-reported outcomes of breast cancer patients and survivors. JNCI Cancer Spectrum., 5(1), pkaa104.

van de Poll-Franse, L. V., de Rooij, B. H., Horevoorts, N. J. E., May, A. M., Vink, G. R., Koopman, M., van Laarhoven, H. W. M., Besselink, M. G., Oerlemans, S., Husson, O., Beijer, S., Ezendam, N. P. M., RaijmakersWollersheim, N. J. M. B. M., Hoedjes, M., Siesling, S., van Eenbergen, M. C., & Mols, F. (2021). Perceived care and well-being of patients with cancer and matched norm participants in the COVID-19 crisis: Results of a survey of participants in the Dutch PROFILES registry. JAMA Oncology., 7(2), 279–284.

Schrag, D., Hershman, D. L., & Basch, E. (2020). Oncology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA, 323(20), 2005–2006.

Webster, P. (2020). Virtual health care in the era of COVID-19. Lancet, 395(10231), 1180–1181.

Barsom, E. Z., Feenstra, T. M., Bemelman, W. A., Bonjer, J. H., & Schijven, M. P. (2020). Coping with COVID-19: Scaling up virtual care to standard practice. Nature Medicine., 26(5), 632–634.

van de Haar, J., Hoes, L. R., Coles, C. E., Seamon, K., Fröhling, S., Jäger, D., Valenza, F., de Braud, F., De Petris, L., Bergh, J., Ernberg, I., Besse, B., Barlesi, F., Garralda, E., Piris-Giménez, A., Baumann, M., Apolone, G., Soria, J. C., Tabernero, J., … Voest, E. E. (2020). Caring for patients with cancer in the COVID-19 era. Nature Medicine., 26(5), 665–671.

de Azambuja, E., Trapani, D., Loibl, S., Delaloge, S., Senkus, E., Criscitiello, C., Poortmans, P., Gnant, M., Di Cosimo, S., Cortes, J., Cardoso, F., Paluch-Shimon, S., & Curigliano, G. (2020). ESMO management and treatment adapted recommendations in the COVID-19 era: Breast cancer. ESMO Open., 5(Suppl 3), e000793.

Hanna, T. P., Evans, G. A., & Booth, C. M. (2020). Cancer, COVID-19 and the precautionary principle: Prioritizing treatment during a global pandemic. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 17(5), 268–270.

Marron, J. M., Joffe, S., Jagsi, R., Spence, R. A., & Hlubocky, F. J. (2020). Ethics and resource scarcity: ASCO recommendations for the oncology community during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 38(19), 2201–2205.

Dinmohamed, A. G., Cellamare, M., Visser, O., de Munck, L., Elferink, M. A. G., Westenend, P. J., Wesseling, J., Broeders, M. J. M., Kuipers, E. J., Merkx, M. A. W., Nagtegaal, I. D., & Siesling, S. (2020). The impact of the temporary suspension of national cancer screening programmes due to the COVID-19 epidemic on the diagnosis of breast and colorectal cancer in the Netherlands. Journal of Hematology & Oncology., 13(1), 147.

The, L. O. (2020). Safeguarding cancer care in a post-COVID-19 world. The Lancet Oncology, 21(5), 603.

de Joode, K., Dumoulin, D. W., Engelen, V., Bloemendal, H. J., Verheij, M., van Laarhoven, H. W. M., Dingemans, I. H., Dingemans, A. C., & van der Veldt, A. A. M. (2020). Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on cancer treatment: the patients’ perspective. Eur J Cancer., 136, 132–139.

Dinmohamed, A. G., Visser, O., Verhoeven, R. H. A., Louwman, M. W. J., van Nederveen, F. H., Willems, S. M., Merkx, M. A. W., Lemmens, V. E. P. P., Nagtegaal, I. D., & Siesling, S. (2020). Fewer cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 epidemic in the Netherlands. The Lancet Oncology., 21(6), 750–751.

Moraliyage, H., De Silva, D., Ranasinghe, W., Adikari, A., Alahakoon, D., Prasad, R., Lawrentschuk, N., & Bolton, D. (2021). Cancer in lockdown: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with cancer. The Oncologist., 26(2), e342–e344.

Dobson, C. M., Russell, A. J., & Rubin, G. P. (2014). Patient delay in cancer diagnosis: What do we really mean and can we be more specific? BMC Health Services Research, 14, 387.

Xie, J., Qi, W., Cao, L., Tan, Y., Huang, J., Gu, X., Chen, B., Shen, P., Zhao, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhao, Q., Huang, H., Wang, Y., Fang, H., Jin, Z., Li, H., Zhao, X., Qian, X., Xu, F., et al. (2021). Predictors for fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer patients referred to radiation therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-center cross-section survey. Frontiers in Oncology., 11, 650766.

National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. Third wave shows major surge in hospital admissions in younger age groups. Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Retrieved July 25, 2021, from https://www.rivm.nl/en/news/third-wave-shows-major-surge-in-hospital-admissions-in-younger-age-groups

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO health emergency dashboard (COVID-19). Retrieved Aug 2, 2021, from https://covid19.who.int/region/euro/country/nl

Bernal, J. L., Andrews, N., Gower, C., Gallagher, E., Simmons, R., Thelwall, S., Stowe, J., Tessier, E., Groves, N., Dabrera, G., Myers, R., Campbell, C. N. J., Amirthalingam, G., Edmunds, M., Zambon, M., Brown, K. E., Hopkins, S., Chand, M., & Ramsay, M. (2021). Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (delta) variant. New England Journal of Medicine., 385(7), 585–594.

Kissler, S. M., Tedijanto, C., Goldstein, E., Grad, Y. H., & Lipsitch, M. (2020). Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science, 368(6493), 860–868.

Carreira, H., Williams, R., Müller, M., Harewood, R., Stanway, S., & Bhaskaran, K. (2018). Associations between breast cancer survivorship and adverse mental health outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 110(12), 1311–1327.

Schellekens, M. P. J., & van der Lee, M. L. (2020). Loneliness and belonging: Exploring experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic in psycho-oncology. Psycho-Oncology, 29(9), 1399–1401.

Theofilou, P., & Panagiotaki, H. (2012). A literature review to investigate the link between psychosocial characteristics and treatment adherence in cancer patients. Oncology Reviews, 6(1), e5.

Ayres, A., Hoon, P. W., Franzoni, J. B., Matheny, K. B., Cotanch, P. H., & Takayanagi, S. (1994). Influence of mood and adjustment to cancer on compliance with chemotherapy among breast cancer patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38(5), 393–402.

de Boer, A. G., Torp, S., Popa, A., & HorsboelZadnikRottenbergBardiBultmannSharp, T. V. Y. E. U. L. (2020). Long-term work retention after treatment for cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 14(2), 135–150.

Satin, J. R., Linden, W., & Phillips, M. J. (2009). Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients. Cancer, 115(22), 5349–5361.

Chida, Y., Hamer, M., Wardle, J., & Steptoe, A. (2008). Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nature Clinical Practice Oncology, 5(8), 466–475.

Jammu, A. S., Chasen, M. R., Lofters, A. K., & Bhargava, R. (2021). Systematic rapid living review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer survivors: Update to August 27, 2020. Supportive Care in Cancer, 29(6), 2841–2850.

van der Molen, D. R. M., Bargon, C. A., Batenburg, M. C. T., Gal, R., Young-Afat, D. A., van Stam, L. E., van Dam, I. E., van der Leij, F., Baas, I. O., Ernst, M. F., Maarse, W., Vermulst, N., Schoenmaeckers, E. J. P., van Dalen, T., Bijlsma, R. M., Doeksen, A., & Verkooijen, H. M. (2021). (Ex-)breast cancer patients with (pre-existing) symptoms of anxiety and/or depression experience higher barriers to contact health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment., 186(2), 577–583.

Pan, K.-Y., Kok, A. A. L., Eikelenboom, M., Horsfall, M., Jörg, F., Luteijn, R. A., Rhebergen, D., van Oppen, P., Giltay, E. J., & Penninx, B. W. J. H. (2021). The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with and without depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders: A longitudinal study of three Dutch case-control cohorts. Lancet Psychiatry., 8(2), 121–129.

Taha, S., Matheson, K., Cronin, T., & Anisman, H. (2014). Intolerance of uncertainty, appraisals, coping, and anxiety: The case of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. The British Journal of Health Psychology, 19(3), 592–605.

Swainston, J., Chapman, B., Grunfeld, E. A., & Derakshan, N. (2020). COVID-19 lockdown and its adverse impact on psychological health in breast cancer. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2033.

Young-Afat, D. A., van Gils, C. H., van den Bongard, H., & Verkooijen, H. M. (2017). The Utrecht cohort for Multiple BREast cancer intervention studies and Long-term evaLuAtion (UMBRELLA): Objectives, design, and baseline results. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 164(2), 445–450.

Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR). Netherlands comprehensive cancer organisation (IKNL). Retrieved July 20, 2021, from www.iknl.nl/en/ncr/ncr-data-figures

Central Government (Rijksoverheid). (2022) [Corona Dashboard]. Retrieved Mar 30, 2022, from https://coronadashboard.rijksoverheid.nl/landelijk/intensive-care-opnames

van der Molen, D. R. M., Bargon, C. A., Batenburg, M. C. T., van Stam, L. E., van Dam, I. E., Baas, I. O., Ernst, M. F., Maarse, W., Sier, M., Schoenmaeckers, E. J. P., van Dalen, T., Bijlsma, R. M., Doeksen, A., van der Leij, F., Young-Afat, D. A., & Verkooijen, H. M. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on perceived access to health care and preferences for health care provision in individuals (being) treated for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment., 191(3), 553–564.

Aaronson, N. K., Ahmedzai, S., Bergman, B., Bullinger, M., Cull, A., Duez, N. J., Filiberti, A., Flechtner, H., Fleishman, S. B., Haes, J. C. J. M. D., Kaasa, S., Klee, M., Osoba, D., Razavi, D., Rofe, P. B., Schraub, S., Sneeuw, K., Sullivan, M., & Takeda, F. (1993). The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute., 85(5), 365–376.

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica., 67(6), 361–370.

de Jong, G. J., & van Tilburg, T. (2008). A shortened scale for overall, emotional and social loneliness. Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie, 39(1), 4–15.

Fayers, P. M., Aaronson, N. K., Bjordal, K., Groenvold, M., Curran, D., Bottomley, A., On behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group. (2001). The EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual (3rd ed.). European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer.

Tan, M. L., Idris, D. B., Teo, L. W., & LohSeowTeoTin, S. Y. G. C. Y. Y. A. S. (2014). Validation of EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 questionnaires in the measurement of quality of life of breast cancer patients in Singapore. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 1(1), 22–32.

Michels, F. A., LatorreMdo, R., & Maciel, M. S. (2013). Validity, reliability and understanding of the EORTC-C30 and EORTC-BR23, quality of life questionnaires specific for breast cancer. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 16(2), 352–363.

Shih, C. L., Chen, C. H., Sheu, C. F., Lang, H. C., & Hsieh, C. L. (2013). Validating and improving the reliability of the EORTC qlq-c30 using a multidimensional Rasch model. Value Health., 16(5), 848–854.

Giesinger, J. M., Loth, F. L. C., Aaronson, N. K., Arraras, J. I., Caocci, G., Efficace, F., Groenvold, M., van Leeuwen, M., Petersen, M. A., Ramage, J., Tomaszewski, K. A., Young, T., & Holzner, B. (2020). Thresholds for clinical importance were established to improve interpretation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in clinical practice and research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology., 118, 1–8.

Cocks, K., King, M. T., Velikova, G., St-James, M. M., Fayers, P. M., & Brown, J. M. (2011). Evidence-based guidelines for determination of sample size and interpretation of the European organisation for the research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire core 30. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29(1), 89–96.

Musoro, J. Z., Coens, C., Fiteni, F., Katarzyna, P., Cardoso, F., Russell, N. S., King, M. T., Cocks, K., Sprangers, M. A., Groenvold, M., Velikova, G., Flechtner, H.-H., & Bottomley, A. (2019). Minimally important differences for interpreting EORTC QLQ-C30 scores in patients with advanced breast cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectrum., 3(3), 037.

Osoba, D., Rodrigues, G., Myles, J., Zee, B., & Pater, J. (1998). Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 16(1), 139–144.

Spinhoven, P., Ormel, J., Sloekers, P. P., Kempen, G. I., Speckens, A. E., & Van Hemert, A. M. (1997). A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychological Medicine, 27(2), 363–370.

Ramirez, A. J., Richards, M. A., Jarrett, S. R., & Fentiman, I. S. (1995). Can mood disorder in women with breast cancer be identified preoperatively? British Journal of Cancer, 72(6), 1509–1512.

Vodermaier, A., & Millman, R. D. (2011). Accuracy of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Supportive Care in Cancer, 19(12), 1899–1908.

Smith, A. B., Selby, P. J., Velikova, G., Stark, D., Wright, E. P., Gould, A., & Cull, A. (2002). Factor analysis of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale from a large cancer population. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 75(2), 165–176.

Snaith, R. P. (2003). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1(1), 29.

Jayadevappa, R., Cook, R., & Chhatre, S. (2017). Minimal important difference to infer changes in health-related quality of life-a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 89, 188–198.

de Jong Gierveld, J., van Tilburg, T. G. Manual of the loneliness scale. VU University Amsterdam, Department of Social Research Methodology. Retrieved July 19, 2021, from https://home.fsw.vu.nl/tg.van.tilburg/manual_loneliness_scale_1999.html

De Jong, G. J., & Van Tilburg, T. (2010). The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: Tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. European Journal of Ageing, 7(2), 121–130.

Han, J., Zhou, F., Zhang, L., Su, Y., & Mao, L. (2021). Psychological symptoms of cancer survivors during the COVID-19 outbreak: A longitudinal study. Psycho-Oncology, 30(3), 378–384.

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet., 395(10227), 912–920.

Juanjuan, L., Santa-Maria, C. A., Hongfang, F., Lingcheng, W., Pengcheng, Z., Yuanbing, X., Yuyan, T., Zhongchun, L., Bo, D., Meng, L., Qingfeng, Y., Feng, Y., Yi, T., Shengrong, S., Xingrui, L., & Chuang, C. (2020). Patient-reported outcomes of patients with breast cancer during the COVID-19 outbreak in the epicenter of China: A cross-sectional survey study. Clin Breast Cancer., 20(5), e651–e662.

Gregorowitsch, M. L., van den Bongard, H., Young-Afat, D. A., Pignol, J. P., van Gils, C. H., May, A. M., & Verkooijen, H. M. (2018). Severe depression more common in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ than early-stage invasive breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 167(1), 205–213.

Lei, Y. Y., Ho, S. C., Lau, T. K. H., Kwok, C., Cheng, A., Cheung, K. L., Lee, R., & Yeo, W. (2021). Longitudinal change of quality of life in the first five years of survival among disease-free Chinese breast cancer survivors. Quality of Life Research, 30(6), 1583–1594.

Koch, L., Jansen, L., Herrmann, A., Stegmaier, C., Holleczek, B., Singer, S., Brenner, H., & Arndt, V. (2013). Quality of life in long-term breast cancer survivors—A 10-year longitudinal population-based study. Acta Oncologica, 52(6), 1119–1128.

Maurer, T., Thöne, K., Obi, N., Jung, A. Y., Behrens, S., Becher, H., & Chang-Claude, J. (2021). Health-related quality of life in a cohort of breast cancer survivors over more than 10 years post-diagnosis and in comparison to a control cohort. Cancers (Basel)., 13(8), 1854.

Snyder, C. F., Blackford, A. L., Sussman, J., Bainbridge, D., Howell, D., Seow, H. Y., Carducci, M. A., & Wu, A. W. (2015). Identifying changes in scores on the EORTC-QLQ-C30 representing a change in patients’ supportive care needs. Quality of Life Research., 24(5), 1207–16.

Rentscher, K. E., Zhou, X., Small, B. J., Cohen, H. J., Dilawari, A. A., Patel, S. K., Bethea, T. N., Van Dyk, K. M., Nakamura, Z. M., Ahn, J., Zhai, W., Ahles, T. A., Jim, H. S. L., McDonald, B. C., Saykin, A. J., Root, J. C., Graham, D. M. A., Carroll, J. E., & Mandelblatt, J. S. (2021). Loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in older breast cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Cancer., 19, 3671–3679.

Statistics Netherlands (CBS). [Eenzaamheid.]. Retrieved Aug 4, 2021, from https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/maatwerk/2020/52/eenzaamheid. Updated Dec 18, 2020

Pain, D., & Carbone, L. A. (2020). COVID-19: A time of heightened uncertainty for cancer patients and increased need for psychosocial support. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 2(4), e037.

Islam, J. Y., Vidot, D. C., & Camacho-Rivera, M. (2021). Evaluating mental health-related symptoms among cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of the COVID impact survey. JCO Oncology Practice., 17(9), e1258–e1269.

Sully, K., Trigg, A., Bonner, N., et al. (2019). Estimation of minimally important differences and responder definitions for EORTC QLQ-MY20 scores in multiple myeloma patients. European Journal of Haematology, 103(5), 500–509.

Janelsins, M. C., Heckler, C. E., Peppone, L. J., Ahles, T. A., Mohile, S. G., Mustian, K. M., Palesh, O., O’Mara, A. M., Minasian, L. M., Williams, A. M., Magnuson, A., Geer, J., Dakhil, S. R., Hopkins, J. O., & Morrow, G. R. (2018). Longitudinal trajectory and characterization of cancer-related cognitive impairment in a nationwide cohort study. Journal of Clinical Oncology., 36(32), Jco2018786624.

Puhan, M. A., Frey, M., Büchi, S., & Schünemann, H. J. (2008). The minimal important difference of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 6, 46–46.

Feikin, D. R., Higdon, M. M., Abu-Raddad, L. J., Andrews, N., Araos, R., Goldberg, Y., Groome, M. J., Huppert, A., O’Brien, K. L., Smith, P. G., Wilder-Smith, A., Zeger, S., Knoll, M. D., & Patel, M. K. (2022). Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta-regression. The Lancet., 399(10328), 924–44.

Long, B., Carius, B. M., Chavez, S., et al. (2022). Clinical update on COVID-19 for the emergency clinician: Presentation and evaluation. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 54, 46–57.

Hanson, S. W., Abbafati, C., Aerts, J. G., Al-Aly, Z., Ashbaugh, C., Ballouz, T., Blyuss, O., Bobkova, P., Bonsel, G., Borzakova, S., Buonsenso, D., Butnaru, D., Carter, A., Chu, H., De Rose, C., Diab, M. M., Ekbom, E., El-Tantawi, M., Fomin, V., et al. (2022). Estimated global proportions of individuals with persistent fatigue, cognitive, and respiratory symptom clusters following symptomatic COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021. JAMA., 328(16), 1604–15.

Dutch Cancer Society (KWF). [Vriendendienst]. Retrieved Sept 5, 2021, from https://www.kwfvriendendienst.n

Kanker.nl [Coronatijd - gezelschap en steun vind je hier Foundation Kanker.nl]. Retrieved from Aug 28, 2021,from https://www.kanker.nl/ervaringen-van-anderen/gespreksgroepen/coronatijd-gezelschap-en-steun-vind-je-hier

Central Government (Rijksoverheid). [Kabinet stelt 200 miljoen euro beschikbaar voor welzijn in coronatijd]. Retrieved from Aug 28, 2021,from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/actueel/nieuws/2021/02/12/kabinet-stelt-200-miljoen-euro-beschikbaar-voor-welzijn-in-coronatijd

Turgeman, I., Goshen-Lago, T., Waldhorn, I., Karov, K., Groisman, L., Benaim, A. R., Almog, R., Halberthal, M., & Ben-Aharon, I. (2019). Psychosocial perspectives among cancer patients during the coronavirus disease, (COVID-19) crisis: An observational longitudinal study. Cancer Report (Hoboken)., 2021, e1506.

Xiang, Y.-T., Yang, Y., Li, W., Zhang, L., Zhang, Q., Cheung, T., & Ng, C. H. (2020). Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(3), 228–229.

Chou, A. F., Stewart, S. L., Wild, R. C., & Bloom, J. R. (2012). Social support and survival in young women with breast carcinoma. Psycho-Oncology, 21(2), 125–133.

Kroenke, C. H., Michael, Y. L., Poole, E. M., Kwan, M. L., Nechuta, S., Leas, E., Caan, B. J., Pierce, J., Shu, X.-O., Zheng, Y., & Chen, W. Y. (2017). Postdiagnosis social networks and breast cancer mortality in the after breast cancer pooling project. Cancer., 123(7), 1228–37.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research (including study design; data collection, analysis, interpretation of data; and writing of the report), authorship, and/ or (the decision to submit the article for) publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The corresponding author (HM Verkooijen) confirms that she had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. Each author has contributed significantly to, and is willing to take public responsibility for, the following aspects of the study: conceptualization: CAB, DRMvdM, MCTB, LEvanS, IEvD, IO Baas, LMV, WM, MS, EJPS, JPJB, RB, FvdL, AD, DAY-A, and HMV; data curation: CAB, DRMvdM, MCTB, LEvS, IEvD, IOB, LMV, MS, EJPS, JPJB, RB, FvdL, AD, and HMV; formal analyses: CAB, DRMvdM, MCTB, LEvS, DAY-A, and HMV; funding acquisition: not applicable; investigation: CAB, DRMvdM, DAY-A, and HMV; methodology: CAB, DRMvdM, DAY-A, and HMV; project administration: CAB and DRMvdM; recourses: CAB and HMV; software: CAB and DRMvdM; supervision: AD, DAY-A, and HMV; validation: MCTB, AD, DAY-A, and HMV; visualization: CAB and DRMvdM; writing – original draft: CAB and DRMvdM; and writing – review & editing: CAB, DRMvdM, MCTB, LEvS, IEvD, IOB, LMV, WM, MS, EJPS, JPJB, RB, FvdL, AD, DAY-A, and HMV.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial or personal conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

This study was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/ or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent from all individual participants was obtained within UMBRELLA.

Originality of the work

This manuscript, including related data, figures and tables, is solely the work of the authors stated, has not been published, and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bargon, C.A., Mink van der Molen, D.R., Batenburg, M.C.T. et al. Physical and mental health of breast cancer patients and survivors before and during successive SARS-CoV-2-infection waves. Qual Life Res 32, 2375–2390 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-023-03400-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-023-03400-6