Abstract

Purpose

Using health-related quality-of-life measures for patient management requires knowing what changes in scores require clinical attention. We estimated changes on the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life-Questionnaire-Core-30 (EORTC-QLQ-C30), representing important changes by comparing to patient-reported changes in supportive care needs.

Methods

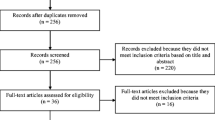

This secondary analysis used data from 193 newly diagnosed cancer patients (63 % breast, 37 % colorectal; mean age 60 years; 20 % male) from 28 Canadian surgical practices. Participants completed the Supportive Care Needs Survey-Short Form-34 (SCNS-SF34) and EORTC-QLQ-C30 at baseline, 3, and 8 weeks. We calculated mean changes in EORTC-QLQ-C30 scores associated with improvement, worsening, and no change in supportive care needs based on the SCNS-SF34. Mean changes in the EORTC-QLQ-C30 scores associated with the SCNS-SF34 improved and worsened categories were used to estimate clinically important changes, and the ‘no change’ category to estimate insignificant changes.

Results

EORTC-QLQ-C30 score changes ranged from 6 to 32 points for patients reporting improved supportive care needs; statistically significant changes were 10–32 points. EORTC-QLQ-C30 score changes ranged from 21-point worsening to 21-point improvement for patients reporting worsening supportive care needs; statistically significant changes were 9–21 points in the hypothesized direction and a 21-point statistically significant change in the opposite direction. EORTC-QLQ-C30 score changes ranged from a 1-point worsening to 16-point improvement for patients reporting stable supportive care needs.

Conclusion

These data suggest 10-point EORTC-QLQ-C30 score changes represent changes in supportive care needs. When using the EORTC-QLQ-C30 in clinical practice, scores changing ≥10 points should be highlighted for clinical attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- EORTC-QLQ-C30:

-

European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life-Questionnaire-Core-30

- GEE:

-

Generalized estimating equation

- HRQOL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- MID:

-

Minimal important difference

- PRO:

-

Patient-reported outcome

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SCNS-SF34:

-

Supportive Care Needs Survey-Short Form-34

References

Snyder, C. F., & Aaronson, N. K. (2009). Use of patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice. The Lancet, 374, 369–370.

Greenhalgh, J. (2009). The applications of PROs in clinical practice: What are they, do they work, and why? Quality of Life Research, 18, 115–123.

Velikova, G., Booth, L., Smith, A. B., et al. (2004). Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22, 714–724.

Berry, D. L., Blumenstein, B. A., Halpenny, B., et al. (2011). Enhancing patient-provider communication with the electronic self-report assessment for cancer: A randomized trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29, 1029–1035.

Detmar, S. B., Muller, M. J., Schornagel, J. H., Wever, L. D. V., & Aaronson, N. K. (2002). Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 288, 3027–3034.

Greenhalgh, J., & Meadows, K. (1999). The effectiveness of the use of patient-based measures of health in routine practice in improving the process and outcomes of patient care: A literature review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 5, 401–416.

Marshall, S., Haywood, K., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2006). Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: A structured review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 12, 559–568.

Haywood, K., Marshall, S., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2006). Patient participation in the consultation process: A structured review of intervention strategies. Patient Education and Counseling, 63, 12–23.

Cleeland, C. S., Wang, X. S., Shi, Q., et al. (2011). Automated symptom alerts reduce postoperative symptom severity after cancer surgery: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29, 994–1000.

McLachlan, S.-A., Allenby, A., Matthews, J., et al. (2001). Randomized trial of coordinated psychosocial interventions based on patient self-assessments versus standard care to improve the psychosocial functioning of patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 19, 4117–4125.

Snyder, C. F., Blackford, A. L., Aaronson, N. K., et al. (2011). Can patient-reported outcome measures identify cancer patients’ most bothersome issues? Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29, 1216–1220.

Snyder, C. F., Blackford, A. L., Wolff, A. C., et al. (2013). Feasibility and value of PatientViewpoint: A web system for patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice. Psycho-Oncology, 22, 895–901.

Jensen, R. E., Snyder, C. F., Abernethy, A. P., et al. (2013). A review of electronic patient reported outcomes systems used in cancer clinical care. Journal of Oncology Practice, 10, e215–e222.

Brundage, M. D., Bantug, E. T., Little, E. A., Smith, K. A., Snyder, C. F., PRO data presentation stakeholder advisory board. (2014). Which formats for communicating patient-reported outcomes (PROs) work best? Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32, 5s (suppl; abstr 6616).

Snyder, C. F., Blackford, A. L., Brahmer, J. R., et al. (2010). Needs assessments can identify scores on HRQOL questionnaires that represent problems for patients: an illustration with the Supportive Care Needs Survey and the QLQ-C30. Quality of Life Research, 19, 837–845.

Snyder, C. F., Blackford, A. L., Okuyama, T., et al. (2013). Using the EORTC QLQ-C30 in clinical practice for patient management: Identifying scores requiring a clinician’s attention. Quality of Life Research, 22, 2685–2691.

Snyder, C. F., Dy, S. M., Hendricks, D. E., et al. (2007). Asking the right questions: Investigating needs assessments and health-related quality of life questionnaires for use in oncology clinical practice. Supportive Care in Cancer, 15, 1075–1085.

Sussman, J., Howell, D., Bainbridge, D., et al. (2012). Results of a cluster randomized trial to evaluate a nursing lead supportive care intervention in newly diagnosed breast and colorectal cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30 (suppl), Abstract 6035.

Aaronson, N. K., Ahmedzai, S., Bergman, B., et al. (1993). The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85, 365–376.

Lipscomb, J., Gotay, C. C., & Snyder, C. (Eds.). (2005). Outcomes assessment in cancer: Measures, methods, and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Snyder, C. F., Herman, J. M., White, S. M., et al. (2014). When using patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice, the measure matters: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Oncology Practice, 10, e299–e306.

Bonevski, B., Sanson-Fisher, R. W., Girgis, A., et al. (2000). Evaluation of an instrument to assess the needs of patients with cancer. Cancer, 88, 217–225.

Sanson-Fisher, R., Girgis, A., Boyes, A., et al. (2000). The unmet supportive care needs of patients with cancer. Cancer, 88, 226–237.

National Cancer Institute. Grid-Enabled Measures Database: Supportive Care Needs Survey-Short Form (SCNS-SF34). https://www.gem-beta.org/Public/MeasureDetail.aspx?mid=1592&cat=2.

Snyder, C. F., Aaronson, N. K., Choucair, A. K., et al. (2012). Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: A review of the options and considerations. Quality of Life Research, 21, 1305–1314.

International Society for Quality of Life Research. User’s Guide to Implementing Patient‐Reported Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice, Version: November 11, 2011. http://www.isoqol.org/research/isoqol-publications.

Jaeschke, R., Singer, J., & Guyatt, G. H. (1989). Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Controlled Clinical Trials, 10, 407–415.

Osoba, D., Rodrigues, G., Myles, J., Zee, B., & Pater, J. (1998). Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 16, 139–144.

King, M. T. (1996). The interpretation of scores from the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30. Quality of Life Research, 5, 555–567.

Maringwa, J. T., Quinten, C., King, M., et al. (2011). Minimal important differences for interpreting health-related quality of life scores from the EORTC QLQ-C30 in lung cancer patients participating in randomized controlled trials. Supportive Care in Cancer, 19, 1753–1760.

Ahmed, S., Schwartz, C., Ring, L., & Sprangers, M. A. G. (2009). Applications of health-related quality of life for guiding health care: Advances in response shift research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62, 1115–1117.

Kvam, A. K., Wisloff, F., & Fayers, P. M. (2010). Minimal important differences and response shift in health-related quality of life; a longitudinal study in patients with multiple myeloma. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8, 79.

Acknowledgments

This analysis was funded by the American Cancer Society (# MRSG-08-011-01-CPPB). The original data collection was supported by the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care. Dr Snyder and Dr Carducci are members of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins (P30 CA 006973).

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Snyder, C.F., Blackford, A.L., Sussman, J. et al. Identifying changes in scores on the EORTC-QLQ-C30 representing a change in patients’ supportive care needs. Qual Life Res 24, 1207–1216 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0853-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0853-y