Abstract

This paper investigates how a monopoly seller should determine the optimal set of pricing variables (pricing metrics) for third-degree price discrimination applications in which buyers have log-normally distributed willingness-to-pay (WTP). In a setup that closely resembles linear and probit regressions, this paper shows that when the monopoly seller is restricted to using one metric and no price discrimination cost exists, the pricing metric that best reduces the residual variance of buyers’ willingness-to-pay is the one that maximizes revenue. Equivalently, the explanatory power of willingness-to-pay is the ordering criterion. This paper also shows that this criterion is not universally true when willingness-to-pay follows other distributions. When the seller incurs price discrimination costs associated with different metrics, the ordering criterion becomes the explanatory power of each pricing metric divided by its cost. This paper also discusses how to apply this model to solve real-world pricing problems with contingent valuation models or using probit regression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this study, WTP is defined as the largest amount of money that an individual or group will pay for a product or service without being worse off with the purchase than without it.

In this example, readers may consider pricing by “weight” or “distance” as second-degree price discrimination cases. In fact, conventional categorization by second- and third-degree price discrimination is not exhaustive. Economists find different ways to categorize price discrimination (e.g., Png and Lehman 2007). This paper categorizes price discrimination into three cases: (1) buyers are not allowed to change the values of their metrics (3rd degree price discrimination); (2) buyers are allowed to change the values of their metrics, but rarely do so in practice; (3) buyers can and do change metrics values in practice (2nd degree price discrimination). Our model applies well to the first two cases and the DHL example applies to the second case. Specifically, a one-time customer who does not use DHL frequently, essentially, cannot change the distance or the weight of a package. Other examples include the following: eTrade’s users may not change the dollar value or number of their transactions because transaction fee is relatively small, and eBay’s auction sellers are charged a percentage of final auction prices, which are beyond their control. Some apparel retailers price by size, although consumers can self-select different sizes, they won’t choose other sizes because of small price differences.

The objective of this paper is to advise marketing decision makers via a data-driven model. Also, competitive equilibrium results are not an appropriate focus because few marketers are equipped with sufficient analytical tools to make rational decisions about the metric selection problem (Shugan 2002). Relaxing the monopoly assumption also conflicts with the normality assumption, which is required for linking the present model to empirical models.

A rigorous model about unfairness in price discrimination should be included as part of the WTP of each type of customer, rather than an additional cost. This is an important topic for future research, but is beyond the scope of the present paper.

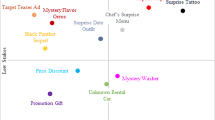

Residual Variance = \( \tfrac{SSE}{n - q}; \) \( SSE = (1 - {R^2}) \times n \times \)Prior Variance. n = 777 (the number of sample). q = 30 (the number of independent variables).

If we estimate β 0 and β 1 by the probit model, then we cannot derive both μ and σ from Equation (8). If we try to estimate β 0, β 1 and σ at the same time using the probit model, then the first-order conditions of the maximum likelihood function will be a system of linearly dependent equations.

References

Allenby, G. M., & Rossi, P. E. (1999). Marketing models of consumer heterogeneity. Journal of Econometrics, 89(1–2), 57–78.

Anderson, E. T., & Simester, D. I. (2008). Does demand fall when customers perceive that prices are unfair? The case of premium pricing for large sizes. Marketing Science, 27(3), 495–500.

Armstrong, M. (1996). Multiproduct nonlinear pricing. Econometrica, 64(1), 51–75.

Bagnoli, M., & Bergstrom, T. (2005). Log-concave probability and its applications. Economic Theory, 26, 445–469.

Besanko, D., Dube, J. P., & Gupta, S. (2003). Competitive price discrimination strategies in a vertical channel using aggregate retail data. Management Science, 49(9), 1121–1138.

Bolton, R. N., & Myers, M. B. (2003). Price-based global market segmentation for services. Journal of Marketing, 67(3), 108–128.

Cameron, T. A., & James, M. D. (1987). Estimating willingness to pay from survey data — An alternative pre-test-market evaluation procedure. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(4), 389–395.

Chen, Y., & Iyer, G. (2002). Individual marketing with imperfect targetability. Marketing Science, 21(2), 197–208.

Chen, Y., Narasimhan, C., & Zhang, Z. J. (2001). Consumer addressability and customized pricing. Marketing Science, 20(1), 23–41.

Choudhary, V., Ghose, A., Mukhopadhyay, T., & Rajan, U. (2005). Personalized pricing and quality differentiation. Management Science, 51(7), 1120–1130.

Corts, K. (1998). Third-degree price discrimination in oligopoly: all-out competition and strategic commitment. The Rand Journal of Economics, 29(2), 306–323.

Feinberg, F., Krishna, A., & Zhang, Z. J. (2002). Do we care what others get? A behaviorist approach to targeted promotions. Journal of Marketing Research, 39(3), 277–291.

Greene, W. (2003). Econometric Analysis. Prentice Hall, fifth edition.

Ghose, A. & Huang, K. (2009). Personalized Pricing and Quality Customization. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 18(4), forthcoming.

Hsiao, C., & Sun, B. H. (1999). Modeling survey response bias — with an analysis of the demand for an advanced electronic device. Journal of Econometrics, 89(1–2), 15–39.

Hofstede, F. T., Wedel, M., & Steenkamp, J. M. (2002). Identifying spatial segments in international markets. Marketing Science, 21(2), 160–177.

Huang, K. (2009). Equilibrium Market Segmentation for Targeted Pricing Based on Customer Characteristics. SSRN Working Paper Series.

Keenan, F. (2003). The price is really right with a web-savvy system. Business Week, 3826.

Khan, R. J., & Jain, D. C. (2005). An empirical analysis of price discrimination mechanisms and retailer profitability. Journal of Marketing Research, 42(4), 516–524.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. (1986). Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: entitlements in the market. American Economic Review, 76(4), 728–741.

Krishna, A., Feinberg, F. M., & Zhang, Z. J. (2007). Should price increases be targeted? Pricing power and selective vs. across-the-board price increases. Management Science, 53(9), 1407–1422.

Leslie, P. (2004). Price discrimination in Broadway theater. The Rand Journal of Economics, 35(3), 520–541.

Liu, Y., & Zhang, Z. J. (2006). The benefits of personalized pricing in a channel. Marketing Science, 25(1), 97–105.

Montgomery, A. L. (1997). Creating micro-marketing pricing strategies using supermarket scanner data. Marketing Science, 16(4), 315–337.

Park, J. H., & MacLachlan, D. L. (2008). Estimating willingness to pay with exaggeration bias-corrected contingent valuation method. Marketing Science, 27(4), 691–698.

Plott, C. R., & Zeiler, K. (2005). The willingness to pay-willingness to accept gap, the “endowment effect”, subject misconceptions, and experimental procedures for eliciting valuations. American Economic Review, 95(3), 530–545.

Png I. and Lehman D. (2007). Managerial Economics. Wiley-Blackwell, 3rd edition.

Rappoport, P., Taylor, L. D., Kridel, D., & Alleman, J. (2004). Estimating the demand for voice over IP services. Berlin, Germany: Fifteenth Biennial Conference of the ITS.

Rochet, J. C., & Chone, P. (1998). Ironing, sweeping, and multidimensional screening. Econometrica, 66(4), 783–826.

Rossi, P. E., McCulloch, R. E., & Allenby, G. M. (1996). The value of purchase history data in target marketing. Marketing Science, 15(4), 321–340.

Schmalensee, R. (1981). Output and welfare implications of monopolistic third-degree price discrimination. American Economic Review, 71(1), 242–247.

Shaffer, G., & Zhang, Z. J. (1995). Competitive coupon targeting. Marketing Science, 14(4), 395–416.

Shaffer, G., & Zhang, Z. J. (2002). Competitive one-to-one promotions. Management Science, 48(9), 1143–1160.

Shugan, S. M. (2002). Marketing Science, models, monopoly models, and why we need them. Marketing Science, 21(3), 223–228.

Sonnier, G., Ainslie, A., & Otter, T. (2007). Heterogeneity distributions of willingness-to-pay in choice models. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 5(3), 313–331.

Thibodeau, P. (2004). IT execs ambivalent about subscription pricing. Computerworld, 38(15), 7.

Thisse, J.-F., & Vives, X. (1989). On the strategic choice of spatial price policy. American Economic Review, 78(1), 122–138.

Varian, H. (1985). Price discrimination and social welfare. American Economic Review, 75(4), 870–875.

Voelckner, F. (2006). An empirical comparison of methods for measuring consumers’ willingness to pay. Marketing Letters, 17(2), 137–149.

Wertenbroch, K., & Skiera, B. (2002). Measuring consumers’ willingness to pay at the point of purchase. Journal of Marketing Research, 39(2), 228–241.

Xia, L., Monroe, K. B., & Cox, J. L. (2004). The price is unfair! A conceptual framework of price fairness perceptions. Journal of Marketing, 68(4), 1–15.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper is based on my dissertation at New York University. I would like to thank my advisor, Roy Radner, for encouragements and numerous helpful suggestions. I would also like to thank the following people for their comments on the earlier drafts of this paper: Joel Steckel, William Greene, Lorin Hitt, DJ Wu, Ivan Png, Anindya Ghose, Arun Sundararajan, Ying-Ju Chen, the co-editor, the two anonymous associate editors, seminar participants at Workshop on Information Systems and Economics 2006, Stern School of Business, University of Connecticut, Georgia Tech., Wharton School of Business, and National University of Singapore. This project has been supported by Taiwan Merit Scholarship(TMS-094-1-A-043). The usual disclaimer applies

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, KW. Optimal criteria for selecting price discrimination metrics when buyers have log-normally distributed willingness-to-pay. Quant Mark Econ 7, 321–341 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11129-009-9069-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11129-009-9069-9

Keywords

- Price discrimination

- Pricing research

- Promotion

- Segmentation

- Probit regression

- Contingent valuation model