Abstract

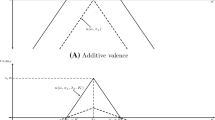

This paper studies electoral competition between two purely office-motivated and heterogeneous (in terms of valence) established candidates when the entry of a lesser-valence third candidate is anticipated. In this model, when the valence asymmetries among candidates are not very large, an essentially unique equilibrium always exists and it is such that: (a) the two established candidates employ pure strategies, (b) the high-valence established candidate offers a more moderate platform than the low-valence established candidate, (c) the entrant locates between the two established candidates and nearer to the established high-valence candidate and, surprisingly, (d) both established candidates receive equal vote-shares.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The term centripetal force denotes here the force that makes one candidate want to move in the direction of the other candidate and not necessarily towards some notion of a center of the policy space.

Introduction of a valence asymmetry between the two candidates in such a model of electoral competition seems very intuitive as common observation dictates that voters decide which candidate to support not only on the basis of the electoral platforms, but also on the basis of non-policy characteristics such as charisma, corruption allegations, personal appeal and others.

Further results on electoral competition between heterogeneous candidates (or parties) may be found in Stokes (1963), Adams (1999), Ansolabehere and Snyder (2000), Erikson and Palfrey (2000), Dix and Santore (2002), Laussel and Breton (2002), Aragonès and Palfrey (2005), Herrera et al. (2008), Schofield (2007), Degan (2007), Kartik and McAfee (2007), Carillo and Castanheria (2008), Meirowitz (2008), Zakharov (2009), Ashworth and de Mesquita (2009), Krasa and Polborn (2012), Pastine and Pastine (2012), Ansolabehere et al. (2012), Xefteris (2012), Bernheim and Kartik (2014), Aragonès and Xefteris (2017a, b).

Results for the case in which candidates are office-motivated and the third-candidate’s entry decision is endogenous can be found in Greenberg and Shepsle (1987), Weber (1992, 1997), Callander (2005), Callander and Wilson (2007), Buisseret (2017), Shapoval et al. (2015). The last study relates to the present paper also because an established candidate is considered to have a valence advantage over the entrant. Unlike the current paper though, Shapoval et al. (2015): (a) consider rank-motivated candidates and (b) they show existence of an equilibrium only when the valence asymmetry between the high-valence established candidate and the entrant is substantially large. Moreover, Osborne (1993) provides results for the case in which the entry of all candidates (and not just that of a third entrant) is endogenous. Loertscher and Muehlheusser (2011) also study a model such that entry of all candidates is endogenous, but, in contrast to Osborne (1993), who assumes that all players decide whether to enter or not simultaneously, they consider that candidates’ decisions are taken in a sequential manner. For the standard Downsian model without valence asymmetries or endogenous entry one is referred to Eaton and Lipsey (1975), Shaked (1982), Osborne and Pitchik (1986) and Collins and Sherstyuk (2000). Welfare implications of the number of competing candidates in different setups are discussed, for instance, in Dellis (2009) and Crutzen et al. (2009).

Despite the fact that mixed strategies commonly are used in certain branches of the literature (one is referred, for example, to Baye et al. (1996), who characterize mixed equilibria for all-pay auctions), their use in electoral competition models is still not universally accepted.

Three-candidate electoral competition models with valence asymmetries that consider simultaneous platform decisions also may result in equilibria such that the highest and the lowest valence candidates are located to the left (right) of the median voter, while the intermediate valence candidate is located to the right (left) of the median voter (see, for example, Evrenk and Kha 2011; Xefteris 2014).

A recent literature considers local Nash equilibrium to be a reasonable solution concept for electoral competition games. See, for example, Schofield (2007), Krasa and Polborn (2012). A theoretical and experimental investigation of a variant of Palfrey’s (1984) model in which candidates do not differ in valence, but third candidate entry is probabilistic, may be found in Tsakas and Xefteris (2018).

Brusco and Roy (2011) employ this assumption too when they analyze the citizen-candidate model with aggregate uncertainty. We partially relax the assumption after the presentation of the equilibrium existence result.

We need to note here that a substantial difference exists between assuming that the entrant can mix among their \(\varepsilon\)-best responses and allowing for mixed strategies. The first assumption is mostly technical since it deals with the discontinuities in the entrant’s payoff function—which are a consequence of the continuous policy space. If we consider, for instance, a discrete policy space, then the entrant will always have a well-defined best response and this behavioral assumption could be dropped without any effect on the results. On the other hand, we can never have a pure equilibrium in the standard model without entry, independently of whether the policy space is continuous or discrete (in fact, Aragonès and Palfrey 2002 use explicitly a discrete space to characterize a mixed equilibrium).

Whenever a set H contains a unique element, \(\eta\), we abuse notation slightly and instead of writing \(H=\{\eta \}\), we write \(H=\eta\).

Specifically, Palfrey (1984) shows that (for \(b=0\)), \(F(\hat{y} _{A}-v_{A})\ge \frac{1}{4}\) and that \(F\left( \frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{2}v_{B}+\frac{1 }{2}\hat{y}_{A}\right) \ge \frac{1}{3}\). Hence, \(F\left( \frac{\hat{y}_{A}+v_{A}+\hat{y} _{B}-v_{B}}{2}\right) -F(\hat{y}_{A}-v_{A})=\frac{1}{2}-F(\hat{y}_{A}-v_{A})\le \frac{1}{4}\).

When no valence asymmetries emerge between the two established candidates, that is, when \(v_{A}=v_{B}\ge 0\), we naturally have that \(\left| \frac{1}{2}-\hat{y}_{A}\right| =\left| \frac{1}{2}-\hat{y}_{B}\right|\). Kim (2005) provides an equivalent result by studying this particular case (two established candidates of equal valences face an entrant of lower valence) when the distribution of voters is uniform.

Just for the completeness of the argument, let us note that we consider that the (non-conventional) object [x, x] is the singleton \(\{x\}\). The clarification is necessary because a pair \((y_{A},y_{B})\ne (0,1)\) with \(y_{A}<y_{B}\) might be such that \(y_{A}=0\) and \(y_{B}<1\) or such that \(y_{A}>0\) and \(y_{B}=1\). That is, \([0,y_{A}]\) might be the singleton \(\{0\}\) or \([y_{B},1]\) might be the singleton \(\{1\}\) but never both (\(\{0,1\}\subset [0,y_{A}]\cup [y_{B},1]\)).

Recall that the assumption that \(v_{C}=0\) is without loss of generality. If we considered \(v_{C}>0\) instead, then all the conditions of the equilibrium should be rewritten by substituting \(v_{A}\) with \(v_{A}-v_{C}\) and \(v_{B}\) with \(v_{B}-v_{C}\). That is, an increase in the difference between the valence level of an established candidate and the valence level of the entrant (when the valence difference between the established candidates is fixed) can be seen either as an equal increase in the valence levels of the established candidates or as a reduction in the valence level of the entrant.

References

Adams, J. (1999). Policy divergence in multicandidate probabilistic spatial voting. Public Choice, 100, 103–22.

Ansolabehere, S., & Snyder, J. M, Jr. (2000). Valence politics and equilibrium in spatial election models. Public Choice, 103, 327–336.

Ansolabehere, S., Leblanc, W., & Snyder, J. M, Jr. (2012). When parties are not teams: Party positions in single-member district and proportional representation systems. Economic Theory, 49(3), 521–547.

Aragonès, E., & Palfrey, T. R. (2002). Mixed strategy equilibrium in a Downsian model with a favored candidate. Journal of Economic Theory, 103, 131–161.

Aragones, E., & Palfrey, T. R. (2004). The effect of candidate quality on electoral equilibrium: An experimental study. American Political Science Review, 98(1), 77–90.

Aragonès, E., & Palfrey, T. R. (2005). Social choice and strategic decisions. In D. Austen-Smith & J. Duggan (Eds.), Spatial competition between two candidates of different quality: The effects of candidate ideology and private information. Berlin: Springer.

Aragonès, E., & Xefteris, D. (2012). Candidate quality in a Downsian model with a continuous policy space. Games and Economic Behavior, 75(2), 464–480.

Aragonès, E., & Xefteris, D. (2017a). Imperfectly informed voters and strategic extremism. International Economic Review, 58(2), 439–471.

Aragonès, E., & Xefteris, D. (2017b). Voters’ private valuation of candidates’ quality. Journal of Public Economics, 156, 121–130.

Ashworth, S., & de Mesquita, E. B. (2009). Elections with platform and valence competition. Games and Economic Behavior, 67, 191–216.

Baye, M. R., Kovenock, D., & De Vries, C. G. (1996). The all-pay auction with complete information. Economic Theory, 8(2), 291–305.

Bernheim, B. D., & Kartik, N. (2014). Candidates, character, and corruption. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 6, 205–246.

Brusco, S., & Roy, J. (2011). Aggregate uncertainty in the citizen candidate model yields extremist parties. Social Choice and Welfare, 36(1), 83–104.

Buisseret, P. (2017). Electoral competition with entry under non-majoritarian run-off rules. Games and Economic Behavior, 104, 494–506.

Cadigan, J. (2005). The citizen candidate model: An experimental analysis. Public Choice, 123(1–2), 197–216.

Callander, S. (2005). Electoral competition in heterogeneous districts. Journal of Political Economy, 113(5), 1116–1145.

Callander, S., & Wilson, C. H. (2007). Turnout, polarization, and Duverger’s law. Journal of Politics, 69(4), 1047–1056.

Carillo, J. D., & Castanheria, M. (2008). Information and strategic political polarisation. Economic Journal, 118, 845–874.

Collins, R., & Sherstyuk, K. (2000). Spatial competition with three firms: An experimental study. Economic Inquiry, 38(1), 73–94.

Crutzen, B. S., Castanheira, M., & Sahuguet, N. (2009). Party organization and electoral competition. The Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 26(2), 212–242.

Degan, A. (2007). Candidate valence: Evidence from consecutive presidential elections. International Economic Review, 48(2), 457–482.

Dellis, A. (2009). Would letting people vote for multiple candidates yield policy moderation? Journal of Economic Theory, 144(2), 772–801.

Dix, M., & Santore, R. (2002). Candidate ability and platform choice. Economics Letters, 76, 189–194.

Eaton, B. C., & Lipsey, R. G. (1975). The principle of minimum differentiation reconsidered: Some new developments in the theory of spatial competition. Review of Economic Studies, 42(1), 27–49.

Elbittar, A. & Gomberg, A. (2009). An experimental study of the citizen-candidate model. In E. Aragonès, C. Beviá, H. Lllavador, & N. Schofield (Eds.), The political economy of democracy. Fundación BBVA conference proceedings.

Erikson, R. S., & Palfrey, T. R. (2000). Equilibria in campaign spending games: Theory and data. American Political Science Review, 94, 595–609.

Evrenk, H., & Kha, D. (2011). Three-candidate spatial competition when candidates have valence: Stochastic voting. Public Choice, 147, 421–438.

Greenberg, J., & Shepsle, K. (1987). The effect of electoral rewards in multiparty competition with entry. American Political Science Review, 81, 525–537.

Groseclose, T. (2001). A model of candidate location when one candidate has a valence advantage. American Journal of Political Science, 45, 862–86.

Grosser, J., & Palfrey, T. R. (2014). Candidate entry and political polarization: An antimedian voter theorem. American Journal of Political Science, 58(1), 127–143.

Grosser, J., & Palfrey, T. R. (2017). Candidate entry and political polarization: An experimental study. New York: Mimeo.

Herrera, H., Levine, D., & Martinelli, C. (2008). Policy platforms, campaign spending and voter participation. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 501–513.

Hummel, P. (2010). On the nature of equilibriums in a Downsian model with candidate valence. Games and Economic Behavior, 70(2), 425–445.

Kartik, N., & McAfee, R. P. (2007). Signaling character in electoral competition. American Economic Review, 97, 852–870.

Kim, K. (2005). Valence characteristics and entry of a third party. Economics Bulletin, 4, 1–9.

Krasa, S., & Polborn, M. (2012). Political competition between differentiated candidates. Games and Economic Behavior, 76(1), 249–271.

Laussel, D., & Le Breton, M. (2002). Unidimensional Downsian politics: Median, utilitarian, or what else? Economics Letters, 76, 351–356.

Loertscher, S., & Muehlheusser, G. (2011). Sequential location games. The RAND Journal of Economics, 42(4), 639–663.

Meirowitz, A. (2008). Electoral contests, incumbency advantages and campaign finance. Journal of Politics, 70(3), 681–699.

Osborne, M. J. (1993). Candidate positioning and entry in a political competition. Games and Economic Behavior, 5(1), 133–151.

Osborne, M. J., & Pitchik, C. (1986). The Nature of equilibrium in a location model. International Economic Review, 27(1), 223–237.

Osborne, M. J., & Slivinski, A. (1996). A model of political competition with citizen-candidates. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111(1), 65–96.

Palfrey, T. R. (1984). Spatial equilibrium with entry. Review of Economic Studies, 51, 139–56.

Pastine, I., & Pastine, T. (2012). Incumbency advantage and political campaign spending limits. Journal of Public Economics, 96, 20–32.

Schofield, N. J. (2007). The mean voter theorem: Necessary and sufficient conditions for convergent equilibrium. The Review of Economic Studies, 74, 965–980.

Serra, G. (2010). Polarization of what? A model of elections with endogenous valence. Journal of Politics, 72(2), 426–437.

Shaked, A. (1982). Existence and computation of mixed strategy Nash equilibrium for 3-firms location problem. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 31, 93–96.

Shapoval, A., Weber, S., & Zakharov, A. (2015). Valence influence in electoral competition with rank objectives. New York: Mimeo.

Stokes, D. E. (1963). Spatial models of party competition. American Political Science Review, 57, 368–77.

Tsakas, N., & Xefteris, D. (2018). Electoral competition with third party entry in the lab. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 148, 121–134.

Weber, S. (1992). On hierarchical spatial competition. The Review of Economic Studies, 59(2), 407–425.

Weber, S. (1997). Entry deterrence in electoral spatial competition. Social Choice and Welfare, 15(1), 31–56.

Xefteris, D. (2012). Mixed strategy equilibrium in a Downsian model with a favored candidate: A comment. Journal of Economic Theory, 147(1), 393–396.

Xefteris, D. (2014). Mixed equilibriums in a three-candidate spatial model with candidate valence. Public Choice, 158, 101–120.

Zakharov, A. (2009). A model of candidate location with endogenous valence. Public Choice, 138, 347–366.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xefteris, D. Candidate valence in a spatial model with entry. Public Choice 176, 341–359 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-0549-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-0549-x