Abstract

Accountability relies on voters accurately evaluating government performance in addressing the important issues of the day. This requirement arguably applies to an even greater extent when addressing fundamental societal crises. However, partisanship can bias evaluations, with government partisans perceiving outcomes more favorably, or attributing less responsibility for bad outcomes. We examine partisan motivated reasoning in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic crisis, using panel data and a survey experiment of over 6000 respondents in which vignettes prime respondents about the UK government’s successes and failures in tackling the pandemic. We also propose a novel extension of the partisan bias thesis: partisans arrive at biased judgements of government competence by recalling the past performance of the government differently, according to whether or not their favored party held power at that time. We find that even in the relatively consensual partisan context of the UK’s response to Covid-19, where both major parties endorsed both lockdown and vaccination programs, there is evidence of both current and recall partisan biases: Opposition partisans are more likely to blame the government for negative outcomes and less likely to recall positive aspects of the government’s recent and past performance unless prompted to do so. Our findings have implications for understanding the limits of democratic accountability under crisis conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Democracy relies on citizens holding governments to account at the ballot box for the outcomes of their policies (Fiorina, 1981; Key, 1966; Powell, 2000). Yet research has repeatedly cast doubt on the ability of voters to objectively evaluate government performance on important issues. One frequently raised concern is that many voters have a strong attachment to a particular political party, a ‘partisan identity’, and that this leads to biased assessments of real-world conditions (Anderson, 2007; Green et al., 2002; Sniderman et al., 1991). When outcomes are hard to dispute, government and opposition partisans can agree about the current state of affairs but attribute responsibility for the outcomes to different actors (Bisgaard, 2015; Tilley & Hobolt, 2011). In this paper, we use panel data analysis combined with an experimental approach to examine whether these consequences of partisan bias are present in the context of a highly salient non-economic issue; the UK government’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic, which was noticeably less party polarized than in the more commonly studied US context. We also use the opportunity to test a new potential consequence of partisan reasoning; that partisans may exhibit biased recall of the government’s past performance.

The Covid-19 pandemic provides an excellent opportunity for the study of partisan motivated reasoning and its effects on evaluations of government competency.Footnote 1 Perceiving real-world conditions in line with partisan leanings is to be expected when issues are of low salience to voters and signals about the government’s performance are mixed. The Covid-19 pandemic, however, was highly salient and performance signals were relatively clear. People cared about the government’s handling of the pandemic for over two years,Footnote 2 and the media provided constant coverage and offered continual information about simple indicators like death and vaccination rates throughout (Nielsen et al., 2020). Moreover, Covid-19 handling in the UK was not strongly polarized by party: the government was unchanged throughout the pandemic and the main parties were relatively consensual in their positions on the measures adopted to address the pandemic and implementation of vaccination programs (Klymak & Vlandas, 2022). This contrasts with the polarization over Covid-19 seen in, for example, the United States (Rodriguez et al., 2020). In this respect, Gadarian et al (2022) provide substantial evidence that Donald Trump’s administration tied the pandemic to the president’s political fate, emphasizing partisanship over public health, while Democrats depicted the crisis as evidence of Trump’s lack of concern with public well-being.Footnote 3 In contrast, the comparatively de-polarized UK pandemic provides a particularly tough test of partisan motivated reasoning and the thesis that partisans view the world through a perceptual lens (Achen & Bartels, 2016; Campbell et al., 1960; Green et al., 2002). In this paper we assess whether that lens is strong enough to distort perceptions of the worst global health crisis of recent decades.

In this context, the UK government is widely acknowledged to have performed both extremely badly on some aspects of pandemic management and extremely well on other aspects, thereby creating two strong but opposing performance signals. This allows us to prime respondents to focus on a positive or a negative aspect of handling without lying or distorting reality, increasing the external validity of our results as well as allowing causal inference about the impact of partisanship. As a pre-pandemic wave of our survey was fielded at the time of the UK’s last general election, in December 2019, it further allows us to incorporate pre-Covid partisanship into our models and thus to provide a temporal basis for inferring possible causal impact.

In addition to testing whether partisans display bias when evaluating performance and attributing responsibility for outcomes, we also examine an additional and novel way in which partisan voters may draw different conclusions about the competence of the governing party. Existing literature shows that motivated reasoning can affect the accuracy of a person’s memory (Greene et al., 2020; Murphy et al., 2019). We build on these findings by hypothesizing that government partisans will selectively recall positive aspects of the government’s past performance, whilst opposition partisans focus on more negative aspects. These hypotheses have not been tested in previous research.

Overall, our results show that voters assess government performance in a partisan-biased manner. Panel data analysis provides evidence for almost all of our proposed mechanisms. Government partisans are more positive about the UK’s coronavirus performance than opposition partisans, slightly less likely to attribute responsibility to the government for the pandemic overall, and more positive when recalling the government’s handling of the pandemic a year before our experiment compared to how they perceived it at the time. In contrast, when recalling past performance, opposition partisans are significantly less likely than government partisans to think about a positive aspect of crisis management.

Our experimental results mostly support our panel data findings. We find evidence that government partisans focus on positive aspects of the crisis when forming evaluations of the UK’s performance overall, whilst opposition partisans are less likely to consider the success of the UK’s vaccination program unless explicitly forced to do so. We also find that government partisans are less likely to attribute responsibility for the UK’s pandemic experience to the government even when reminded of the UK’s high death toll.

Theory and Hypotheses

People are not only motivated to reach accurate conclusions, but also to reach conclusions that accord with their prior opinions (Mercier & Sperber, 2017). This process of (directionally) ‘motivated reasoning’ (Kunda, 1990) results in a range of cognitive biases that are frequently observed when voters reason about politics (Flynn, Nyhan, and Reifler 2017; Leeper & Slothuus, 2014; Lodge & Taber, 2013; Taber & Lodge, 2006).

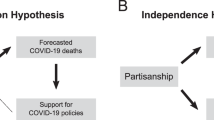

The role of motivated reasoning in politics is most clearly apparent in the case of partisanship. Rather than acting as a ‘running tally’ of party performances (Fiorina, 1981), partisan identity can create a ‘perceptual screen’ through which voters see different realities (Butler & Stokes, 1969; Campbell et al., 1960). In particular, partisans tend to view conditions more favorably when their party is in power (‘selective evaluation’), and to attribute more responsibility for positive outcomes and less responsibility for negative outcomes to the government when their party is in power (‘selective attribution’). As we shall elaborate below, there are also reasons to expect partisans to recall the government’s past performance differently according to whether or not their party held power. These processes allow voters to reduce the cognitive dissonance that results from supporting a political party which is failing to deliver desirable outcomes.

The tendency to twist new information in service to prior opinions is, however, bounded (Lebo & Cassino, 2007; Redlawsk, Civettini, and Emmerson 2010). Even committed partisans acknowledge economic reality when conditions are extreme or signals about performance are particularly clear. The case of Covid-19 allows us to test the limits of partisan reasoning during an extreme and highly salient health crisis, such as occurred in response to the economic crisis of 2008–09 when the endogenous nature of economic perceptions was mitigated by the strength of the signals resulting from the financial crisis (Chzhen, Evans, and Pickup 2014; Parker-Stephen, 2013). For partisanship to affect evaluations of the government during the Covid-19 crisis, and in a relatively non-polarized political environment such as that in the UK, would be strong evidence of the resilience of partisan biases.

Selective Evaluation

The simplest way for partisans to avoid confronting harsh truths about the failures of their favored party or the successes of other parties is to ignore these truths altogether. For example, when inflation rates are worryingly high, government partisans might focus on the low level of unemployment and therefore judge that the economy is performing well.

Existing literature has established that partisans view conditions more positively when their favored party holds office than when it is in opposition. In the US, VanDusky-Allen et al. (2022) find that during the pandemic onset period, Americans typically rated their state governments’ responses more favorably if their governor was a co-partisan. But even in the UK, panel data analysis of voters in the 1990s showed clearly that socio-tropic perceptions of the economy are themselves affected by prior opinions about the incumbent party and by party choice at the last election (Anderson, Mendes, and Tverdova 2004; Evans & Andersen, 2006), as are egocentric economic evaluations (Johnston et al., 2005). The causal relationship between vote choice and economic perceptions extends beyond the UK (Wlezien et al., 1997), as does the persistent effect of partisanship on perceptions of not just the economy (Wilcox & Wlezien, 1993) but also foreign policy (Bartels, 2002). Accordingly, we expect to find descriptive partisan differences in how respondents view the UK’s experience of the Covid-19 pandemic. We anticipate that government partisans will be more positive about the UK’s coronavirus performance than opposition partisans, because they are motivated to believe that the government has handled the crisis successfully.

We expect that government partisans will have arrived at a positive view of the UK’s performance, in part, by already incorporating positive information like the vaccine rollout success into their perceptions. Opposition partisans, in contrast, are expected to have already incorporated negative information like the high death toll. Accordingly, we expect our negative treatment to have a bigger effect on government partisans, who will avoid thinking about negative aspects of the crisis management unless prompted to do so. Likewise, we expect our positive treatment to have a bigger effect on opposition partisans, who will avoid thinking about positive aspects of the government’s crisis management unless prompted to do so:

H1: Government partisans who are reminded about a negative aspect of the UK’s experience of coronavirus are made more negative about the UK’s overall pandemic performance compared to opposition partisans (and conversely for opposition partisans with regards to the positive treatment).

Selective Attribution

When faced with uncomfortable and undeniable facts about reality, there remain a number of possible options for engaging in motivated reasoning (Gaines et al., 2007). One of these options is selective attribution. Voters who hold a partisan identify may accept objective facts about policy outcomes like the state of the country’s economy or health service, but choose to attribute responsibility for these outcomes differently according to whether their favored party holds power. Multiple studies have found evidence that partisans engage in this form of motivated reasoning, raising concerns about democratic accountability (Gomez and Wilson 2003; Rudolph and Grant 2002). The opportunities to engage in selective attribution are expanded by the fact that attributing responsibility for policy outcomes is often difficult even for a non-partisan voter (Anderson, 2000; Hobolt, Tilley, and Banducci 2013; Powell & Whitten, 1993), particularly given the clear political incentives for parties to intentionally blur the lines of responsibility (Hellwig, 2012; Hobolt & Tilley, 2014).

Previous research has shown that partisans in the United States are more likely to attribute responsibility for good economic outcomes and less likely to attribute blame for bad economic outcomes to officials from their favored party (Brown, 2010; Rudolph, 2003a, 2003b, 2006). They are also more likely to selectively blame officials for the handling of natural disasters (Healy et al., 2014; Malhotra & Kuo, 2008), foreign policy (Nawara, 2015; Sirin & Villalobos, 2011) and health care (McCabe, 2016). Most recently, Graham and Singh (2023) show that selective attribution also applied to understandings of the Covid-19 pandemic, with partisans “disproportionately crediting their party for positive developments and blaming opponents for negative developments”.

Far less research has considered the UK context, but some studies have found that the findings from the U.S. extend quite well to the UK. UK partisans are more likely to blame the government for negative economic outcomes when their party does not hold power (Bisgaard, 2015; Marsh & Tilley, 2009), and similar effects have been found for health care outcomes (Tilley & Hobolt, 2011). Most recently with respect to the latter, Yeandle and Maxia (2023) examined the impact of emphasizing the role of the National Health Service in the UK’s Covid-19 vaccination program on attributions of responsibility to the government. They found that respondents attributed less responsibility to the government, but this was not associated with a change in government approval ratings, indicating limitation in the role of attributions for approval.

Our expectations follow the findings from this existing literature. We anticipate that government partisans will attribute less responsibility for negative aspects of crisis management than opposition partisans, and more responsibility for positive aspects. Accordingly, in our experiment, we anticipate that prompting respondents to think about the UK’s high death toll will result in government partisans affording less responsibility for the pandemic overall to the government compared to opposition partisans. We expect the exact reverse when we prompt respondents with details of the UK’s vaccine success:

H2: Government partisans who are reminded about a negative aspect of the UK’s experience of coronavirus attribute less responsibility to the government for the handling of the pandemic overall compared to opposition partisans (and conversely when reminded about a positive aspect).

Selective Recall

Far less research has investigated the effect of partisanship on memory of political events. Literature from psychology shows that human memories are frequently distorted or even patently false (for an overview, see: Koriat, Goldsmith, and Pansky 2000). There is also a clear neurological link between motivated reasoning and memory (Bavel and Pereira 2018). Given that partisans are willing to selectively evaluate present conditions differently according to whether their favored party holds power, it stands to reason that they are also likely to evaluate past performance differently according to whether their party held power at that time. When attempting to reach a motivated conclusion about the competence of the governing party, individuals may selectively recall or ignore elements of the party’s past performance. For example, a government partisan may forget about some of the government’s past failings and instead conclude that the government was performing well, even if they thought the government was performing badly at the time. Despite the intuition of this possibility, we are not aware of any studies directly testing this potential consequence of partisan bias, which we term ‘selective recall’.Footnote 4

Very few articles come close to testing the type of selective recall examined in this paper. Castelli and Carraro (2011) used an experimental approach to show that ideologically conservative participants were more likely to recall negative facts about immigrants than ideological liberal participants. It seems reasonable to expect similar differences in memory according to partisanship. And Jacobson (2010) used panel data to show that perceptions of the Iraq war in the U.S. changed over time in line with partisan identity, with respondents falsely recalling their earlier opinions. For example, many Democrats forgot that they had once believed Iraq to possess weapons of mass destruction (Jacobson, 2010), which mirrors a similar amnesia with respect to the Gulf War of the early 1990s, where Zaller (1994) found that voters had forgotten the partisan divisions preceding the conflict and believed that there had always been uniform, bipartisan support for expelling Saddam Hussein from Kuwait.

Our paper builds on these findings by considering whether past memories about government performance can be affected by partisanship. The question of whether voters can accurately recall past performance, or whether this is biased by partisan identity, is important for understanding the relationship between time and the limits of democratic accountability.

We expect that partisan bias will result in government partisans recalling the government’s performance a year ago more favorably than opposition partisans. The explanation for this could of course simply be that government partisans were more positive about their handling of the pandemic at the time. In addition, however, we also anticipate that partisan bias actually distorts recollections of the past. Accordingly, we expect that government partisans will recall the government’s past handling more positively than they perceived it at the time, and conversely for opposition partisans.

The motivated reasoning account of this outcome is that people selectively mis-remember their evaluations from the previous year in order to make them consistent with their current beliefs. However, it could also reflect partisan biases in updating. Thus government partisans incorporate new information (e.g. that the vaccine roll out has gone well, so the government were probably fairly effective in preparing the ground for this) whilst opposition partisans incorporate negative information from the present (e.g. long covid rates are high, so perhaps the government was even poorer at handling the crisis than it seemed at the time). So, voters project backwards on the basis of partisan-biased updating procedures.

Whichever of these interpretations is most accurate, we expect this mechanism of selective recall to operate similarly to selective evaluation; government partisans typically avoid thinking about the negative aspects of past performance when evaluating earlier government competence. We therefore anticipate that reminding government partisans of the UK’s high pandemic death toll will have a bigger negative effect than reminding opposition partisans of this fact (opposition partisans are likely to think about the death toll even without a prompt to do so) and conversely for the vaccine success:

H3: Government partisans who are reminded about a negative aspect of the UK’s experience of coronavirus will become more negative about the government’s past handling compared to opposition partisans (and conversely for a positive aspect).

Analytical Strategy

To test our hypotheses, we employ both panel data analysis and a survey experiment. Our data is from the British Election Study Internet Panel (BESIP), and we make use of three waves (19–21) from this survey (Fieldhouse et al., 2021). Wave 19 was fielded between 13th and 23rd December 2019, wave 20 between 3rd and 22nd June 2020, and wave 21 between 7 and 25th May 2021. Our experiment was fielded at the end of the full May 2021 survey wave, in England and Wales, with a sample comprising 6884 respondents who were randomly selected from the full panel (n = 30,821). For tables showing the distribution of the sample across a range of demographic and non-demographic variables, see Appendix 3 of the Supplementary Material.

The timing of these survey waves allows us to exploit exogenous variation in the British experience of the Covid-19 pandemic (see Fig. 1). Covid-19 first reached Europe in early 2020, just after a UK general election that gave then Prime Minister Johnson a large majority in the House of Commons. Yet by May 2020, the UK government was perceived by many as too slow to react to the pandemic, resulting in comparatively high infection and death rates as the virus spread fast during a period of very few restrictions on social activity. By June 2020, when the BESIP wave 20 was in the field, UK citizens had endured multiple weeks of ‘lockdown’, with a police-enforced ‘stay at home’ order that prohibited leaving one’s home except to shop for necessities or engage in one hour of daily exercise. Public approval of the government’s handling of the crisis had dropped from 60% in April to around 40% (Gov.UK, 2023; Yougov, 2023).

By May 2021, the time at which we fielded our experiment, the UK situation had dramatically reversed. Though there had been additional (less extreme) lockdowns in the 11 interceding months, May 2021 was a period of relatively few restrictions, and a time at which the UK’s vaccination program was proving extremely successful. Vaccination rates outstripped those seen across Europe, partly due to the government’s successful procurement program, and the UK’s pandemic performance had received praise even from traditionally anti-Conservative media outlets.Footnote 5 Handling ratings had improved accordingly (Yougov, 2023).

Our panel data analysis uses this exogenous variation to examine evaluations of the government’s handling of Covid-19 as a product of pre-Covid-19 evaluations. Our experiment exploits the variation by priming respondents to think about negative and positive aspects of the crisis without lying or distorting reality; we simply call attention to either Britain’s initial struggle with the virus or to the later success that came from the vaccine program. It is also worth noting that early evidence suggests that voters differ substantially in their evaluation of the government’s performance but tend to agree on what the goal should be (Green et al., 2020), which avoids the conflation of performance evaluations with ideological preferences.

The panel data analysis consists of examining the relationship between pre-pandemic partisanship and evaluations of the government’s handling of the pandemic two years later. On the question of recalled past handling, we also make use of the 2021 survey wave to compare respondents’ recollections of pandemic handling ‘this time last year’ to how they actually responded at the time. Over half (n = 3796) of the full sample had participated in the June 2020 wave of the BESIP, which was fielded one year before our experiment, and 3784 had participated in the December 2019 wave of the BESIP, providing a reasonable sample size for panel data analysis.

To corroborate the findings of our panel data analysis we also make use of an experimental approach. We primed respondents to think about a positive or negative aspect of the UK’s Covid-19 performance, either the successful vaccine program or the high pre-vaccine death toll, and observed how this treatment affected responses to questions about the government’s handling of the pandemic.

Experimental Treatment

We randomly assigned respondents to one of two treatment conditions or to a control group.Footnote 6 For experimental treatments we used short vignettes that highlighted either a negative or a positive aspect of the UK’s experience with the Covid-19 pandemic. By comparing the responses of those in the control group (who received no vignette) to those who did receive a vignette, we can infer whether respondents would have been thinking about the points raised in our vignettes even had we not prompted them first.

The exact wording was as follows:

Negative performance reminder:

“Before the rollout of the coronavirus vaccine, the UK had one of the highest coronavirus death tolls per capita in the entire world. Over 125,000 Britons have died after contracting the virus.”

Positive performance reminder:

“Well over half of the UK adult population have already received their first dose of the Covid-19 vaccine, and the UK continues to have one of the best vaccination rates in the entire world.”

Dependent Variables

After receiving treatment in the form of vignettes, respondents were asked a number of questions that allow us to test our hypotheses about selective evaluation, attribution and recall. First, to test for selective evaluation we asked: “How well has the UK performed overall in dealing with the coronavirus crisis?”. Answers were given on a five-point scale from ‘very well’ to ‘very badly’, with a ‘don’t know’ option available. This dependent variable also acts as a useful manipulation check, allowing us to assess whether respondents were affected by our treatments at all.

We then tested selective attribution by asking three questions about the government’s responsibility for crisis management. Respondents were asked: “To what extent are the following the result of decisions taken by the UK government?” and asked to rate responsibility for three outcomes (in a randomized order) on a scale from 0 (“Not at all due to government decisions”) to 10 (“Entirely due to government decisions”), again with an option for “Don’t know”. The three outcomes we asked about were “The UK’s overall experience of the coronavirus crisis”, “The UK’s high coronavirus death toll” and “The fast pace of the UK’s vaccine rollout”.

To test our novel theoretical expectations about retrospective evaluations of distant past performance, we asked respondents: “Thinking back to this time last year, how well do you think the UK Government had handled the coronavirus outbreak in Britain?”.Footnote 7 This was measured on a 5-point response scale ranging from ‘Very well’ to ‘Very badly’ in order to match the question about the UK’s overall performance and matches the question in the BESIP survey for the June 2020 wave in which respondents were asked: “How well do you think the UK Government has handled the coronavirus outbreak in Britain?”.Footnote 8

Independent Variables

Partisan identity is our main independent variable of interest, which we interact with treatment status to see whether government partisans responded differently to our vignettes compared to opposition partisans. We make use of the standard BESIP question for partisan identity: “Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as Labour, Conservative, Liberal Democrat or what?”, coding all Conservative partisans as ‘government partisans’ and all those expressing any other partisan identity as opposition partisans. This was measured prior to our experiment in the main survey. Of those who also participated in the June 2020 wave of the BESIP, we were able to check whether their partisan identity had changed during the pandemic; just 3% of the sample switched from the Conservatives to another party, or vice versa, and the results reported below remove these switchers from the sample. We also remove the 1% of the sample who were Brexit party identifiers because they are not ‘government partisans’ but cannot really be considered ‘opposition partisans’ given the ideological overlap between the Brexit and Conservative parties. The effect of not removing these individuals can be seen in Appendix 5 of the Supplementary Material, as can the effect of restricting the analysis to Conservative vs Labour, while excluding all other opposition party supporters. The main coefficients are not substantively affected in either case.Footnote 9

Method

We analyze our data with ordinary least squares regression models, with each dependent variable modelled in turn as a function of treatment status. For hypotheses concerning differences of treatment effect by partisan identity we also include the interaction of treatment status with these variables. In the case of our evaluation measures (overall performance and retrospective evaluation) we also re-ran the analysis using ordered logit models—the results of this robustness check were not substantively different from using OLS and can be found in Appendix 5 of the Supplementary Material. The use of randomized allocation to treatment theoretically removes the need to include control variables, since demographics do not differ systematically according to treatment status, but demographic variables can help to increase the precision of other coefficient estimates. Accordingly, all models reported below include full demographic controls for gender, ethnicity, age, class and educational attainment. Full details of how these variables are coded can be found in Appendix 1 of the Supplementary Material.

Surveys typically under-represent individuals with low political attention, which may bias our experimental results if these individuals differ in response to treatment compared to individuals with high political attention. Accordingly, we adapt the weighting variable for our analysis to match the levels of self-reported political attention in our experimental sample to those found in the random probability British Election Study (BES). An additional concern is that our vignette praising the success of the UK’s vaccine program might have an opposite effect on those individuals who oppose vaccination on ideological grounds. All reported models therefore omit those individuals who indicated earlier in the survey that they are not generally in favor of vaccinations (3% of the sample).

The effect of including these individuals and of not weighting by political attention can be found in Appendix 5 of the Supplementary Material. The model specification has no systematic effect on coefficient sizes or standard errors and does not affect our substantive conclusions.

Results—Panel Data Analysis

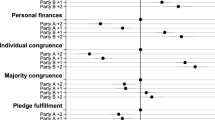

Figure 2 shows the main results of the panel data analysis. The models show clearly that there are partisan differences across almost all dependent variables. In line with our expectations, individuals who were government partisans before the pandemic were more positive about the government’s handling of the pandemic by May 2021 compared to those respondents who were opposition partisans in 2019. Government partisans were less likely than opposition partisans to attribute responsibility for the death toll to the government, but more likely to attribute responsibility for the success of the vaccine rollout. Those without any partisan identity, meanwhile, sat between both of these extremes.

Average predicted position for government and opposition partisans across all six dependent variables. Note: Triangular points indicate that there is a significant difference in the predicted response between government and opposition partisans at the 95% level. The ‘Change in retro handle’ model only includes those individuals who were also surveyed in the pre-experiment wave one year prior to the experiment. The predicted positions displayed in this figure are calculated from a model that also includes controls for gender, ethnicity, age, class and education. The ‘whiskers’ shown reflect 95% confidence intervals. The full results of these models can be found in Appendix 4 of the Supplementary Material

Furthermore, we find that government partisans were more positive when recalling the government’s performance than opposition partisans. We also find evidence that this reflects genuine bias among the government partisans, who are actually more positive than they recalled at the time. Surprisingly, and contrary to the expectations, opposition partisans are also significantly more positive about the government’s handling of the pandemic one year ago than they stated at the time, as are non-partisans.

To give some substantive context to how extreme this last result is, we considered the relationship between current and past evaluations of the UK’s coronavirus experience, and respondents’ recollections of the government’s past handling. As Table 1 shows, there is a greater association between evaluations of the UK’s current coronavirus experience and recall of the government’s earlier handling than there is with individuals’ actual evaluations of the government’s handling at the time.

Furthermore, government partisans rely significantly more on present evaluations when forming their opinions about the past than opposition partisans. This adds further evidence to our suggestion that partisanship affects the way in which individuals recall the past, with government partisans extrapolating back from the sunny present and forgetting about their actual feelings concerning the government’s performance one year ago.

Results—Experiment

Our first dependent variable, perceptions of the UK’s pandemic performance overall, can be used as a manipulation check for our treatments. As Table 2 shows, our treatments had the desired effect. Those individuals who were informed (or reminded) about the UK’s high death toll were significantly more negative about the UK’s experience of the coronavirus pandemic overall than the control group receiving no vignette. Those who were informed (or reminded) about the success of the UK’s vaccination program were significantly more positive about the UK’s experience of the pandemic than the control group.

The results of our main analysis, testing whether our successful manipulation affected government and opposition partisans differently, can be found in Fig. 3. The figure shows the marginal effect of our treatment conditions on each of our dependent variables, separated by partisanship. Triangular points indicate that the interaction term was significant in the model, providing evidence at the 95% level that government and opposition partisans reacted differently to our treatment vignettes.

Average marginal treatment effects for government and opposition partisans for all six dependent variables. Note: Triangular points indicate that the interaction term is significant at the 95% level, i.e., that government partisans differ significantly from opposition partisans in response to that treatment condition for that dependent variable. The ‘Change in retro handle’ model only includes those individuals who were also surveyed in the pre-experiment wave one year prior to the experiment. The marginal effects displayed in this figure are calculated from a model that also includes controls for gender, ethnicity, age, class and education. The ‘whiskers’ shown reflect 95% confidence intervals. The full results of these models can be found in Appendix 4 of the Supplementary Material

With regards to our hypotheses about selective evaluation, we find partial support for H1. In line with our expectations, opposition partisans were significantly more affected by a reminder about the UK’s vaccine success than government partisans, indicating that they were less likely than government partisans to recall the vaccine success when evaluating the UK’s overall experience of coronavirus unless explicitly prompted to do so. However, the negative treatment was equally effective at dampening evaluations of the UK’s performance for government and opposition partisans, and so does not provide further evidence for H1. In line with the panel data analysis, non-partisans lay between these two extremes, being more affected by the positive treatment than government partisans but less so than opposition partisans.

Turning to responsibility attribution, we find the reverse of our findings on performance evaluations, with a significant partisan difference for the effect of the negative treatment but not for the positive treatment. In line with H2, we find that government partisans attribute significantly less responsibility to the government for the UK’s pandemic performance overall when they are first reminded about the UK’s high coronavirus death toll. In this respect they differ significantly from opposition partisans. However, the positive treatment has no effect on either government or opposition partisans, nor for non-partisans.

For our final dependent variable, retrospective handling evaluations, we find no significant partisan differences in the effect of the negative treatment but a significant difference for the positive treatment. When reminding respondents about the UK’s high death toll, we do not find a significant difference in the resulting evaluations of past handling compared to the control group who received no reminder. This is true for both government and opposition partisans. Somewhat surprisingly, we find that non-partisans became slightly more negative about the UK’s past performance when exposed to either the positive or the negative treatment. We did not put forward any expectations on this front, nor have any explanations post-hoc for why this might be the case. Future research into political recall may shed further light on this apparently counter-intuitive finding.

There is some evidence that, for those respondents who were surveyed a year before the experiment as well as during the experiment, government partisans became slightly more negative about the past performance compared to how they felt at the time. Yet this does not significantly differ from opposition partisans.

We do find a significant interaction effect in the case of the positive treatment, as hypothesized in H3. Opposition partisans reminded about a positive aspect of the UK’s coronavirus handling became significantly more positive about the government’s response to the pandemic a year prior to the experiment. Government partisans, by contrast, appear to have become more negative, though this is not quite significant in the model for the full sample. When focusing on those who took the survey one year before the experiment, we also find a significant interaction effect and, in this case, we find that government partisans reminded about the vaccine success actually became more negative about the government’s past performance compared to how they rated it at the time.

Discussion

The results in this paper offer an important confirmation that government evaluations are heavily endogenous to partisan identity. The findings, derived from panel data analysis corroborated by a survey experiment, suggest that partisans evaluate performance, past performance and responsibility in a manner that reflects positively on their favored party, even in the context of a highly salient health crisis like the Covid-19 pandemic.

This article provides an important update to a body of research that has tended to be limited either in scope or by a lack of external validity. Much scholarship on the topic of partisan bias focusses exclusively on the consequences for economic evaluations, often in the United States. This leaves open questions about whether partisan bias extends beyond the economy to other issues, and about how well the results replicate to less politically polarized countries. Studies that attempt to move beyond the economy or the United States, however, tend to struggle with providing experimental treatments that are realistic. For example, experimenters sometimes present respondents with hypothetical scenarios or non-factual prompts, such as claiming to respondents in the treatment group that ‘experts say that… the British economy is doing considerably worse than most other countries’ (Tilley & Hobolt, 2011). There is good reason to doubt whether voters react to real-world information in the same way that they react to these kinds of hypothetical vignettes. Alternatively, some papers focus on natural disasters like hurricanes or floods, which have a short-term saliency and are often quite localized (Malhotra & Kuo, 2008). Our study builds on existing research by addressing both of these shortcomings—we manipulated factually accurate information about a real-world and enduringly salient non-economic crisis.

It is also worth noting that our experimental set-up provided a very tough test of the mechanisms of partisan motivated reasoning established in the literature. Covid-19 was a highly salient event, covered extensively in the national media, with easy to grasp figures like death rates that could be compared to other countries by ordinary voters.Footnote 10 In such a context, finding evidence of motivated reasoning testifies to the strength of the partisan perceptual screen. It also fits with the findings of Becher et al (2023), who examined self-selection biases in benchmarking of media headlines in France, Germany and the UK, showing that respondents sought out information that was consistent with their prior attitude towards the government, even without the use of partisan labels.

It is possible moreover that our experiment setup may have downwards-biased our estimates of motivated reasoning. We fielded the experiment at the end of the May 2021 wave of the British Election Study Internet Panel, meaning that our sample comprised relatively knowledgeable and politically interested respondents who had just answered a number of questions about politics and Covid-19. Accordingly, our treatment vignettes might have been expected to have no detectable effect on these respondents. The fact that we detected changes in the attitudes of our respondents after treatment, and that these changes fell along predictable patterns of partisanship, further emphasizes the robustness of the partisan perceptual screen.

One interesting nuance of our findings is that the effect of our negative and positive prompts was asymmetric. In the case of selective evaluation, our positive prime affected opposition respondents more than government respondents, whilst the negative prime affected both equally. In contrast, our negative treatment affected opposition partisans significantly more for a question of overall responsibility, but the positive treatment was equally ineffective at changing attributions of responsibility for opposition or government partisans. One possible explanation for this is that respondents reacted to our primes by engaging in one of two forms of motivated reasoning. When reminded of a positive, they chose to update their overall evaluation, but when reminded of a negative they instead changed their attribution of responsibility. In neither case was there a need for partisans to both selectively evaluate performance and to selectively attribute responsibility. This accords with findings from previous literature that partisans need only engage in one form of motivated reasoning to arrive at a biased conclusion, for example by attributing responsibility differently only when forced to confront the fact that conditions are getting worse (Bisgaard, 2015). However, more work is needed to establish whether the specific positive / negative asymmetry we found in our paper generalizes to other cases, or whether it is merely a feature of the context in which we conducted our experiment. For example, the UK’s high death toll may simply be too strong a performance signal for even ardent government partisans to ignore, instead leading them to allocate responsibility differently. It is also worth highlighting that for the panel data analysis we do not find this asymmetry, further suggesting that these caveats may not generalize to other settings.

Our paper is also the first to posit and test that voters may differ with regard to how they recall the distant past performance of governments. Our results suggest that recall differs according to partisan identity. Our findings are not meant to suggest that voters care less about the past, though this may be the case, but that they genuinely recall past performance differently. For example, we find experimental evidence that opposition partisans are unlikely to recall the vaccine success when evaluating early government performance unless explicitly reminded about it. Relatedly, government partisans seem more likely than opposition partisans to essentially extrapolate back from the positive present context when evaluating the government’s performance at a far more negative stage in the pandemic. This carries obvious implications for democratic accountability in a context of increasing political polarization and invites further research.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that voters evaluate the government’s performance with bias even in the context of a deadly worldwide pandemic. Not only are voters biased in their evaluation of conditions and their attributions of responsibility, but they appear to have short and biased memories too. There are many challenges to democratic accountability—one is undoubtedly the bias that voters themselves bring into the ballot box. Democracy relies on voters accurately holding governments to account without bias, and our findings concerning selective evaluation, selective attribution and selective recall therefore have important implications for the limits of democratic accountability.

Data availability

All code for replicating these results can be found on the Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/7QO4RV)—the data used can be downloaded from the British Election Study website.

Notes

An alternative explanation for partisan differences is that voters instead engage in a form of ‘Bayesian updating’ (Graham and Singh, 2023; Gerber and Green, 1999). According to this theory, voters strive to reach accurate conclusions but give consideration to prior beliefs when evaluating new information. For example, a Conservative partisan who has concluded that Prime Minister Johnson is competent may, upon exposure to evidence of government incompetence, conclude that Johnson cannot have had much control over that area of government. In practice, these two explanations overlap considerably, as the reason for why some people have more positive competence ratings of political leaders could itself be rooted in partisan motivations.

Health was cited as the most important problem facing the country in over 60% of the YouGov surveys asking that question over the period of 2020 to 2022: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/education/trackers/the-most-important-issues-facing-thecountry

Bisbee and Lee (2022) even found evidence that President Trump’s tweets about the virus influenced differences in social distancing behaviors between Democrat and Republican counties in 2020, although the level of local Covid-19 cases was somewhat more influential.

Our concept of selective recall is distinct from voter myopia. The conventional wisdom in the economic voting literature is that voters evaluate conditions myopically, placing more emphasis on recent economic performance than on past performance (Achen and Bartels 2016; Tufte 1978). In this paper we are not examining the question of whether voters care about recent performance more than past performance, but rather whether voters can recall past performance without bias.

See, for example, the positive coverage in the Guardian at the start of 2021: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/jan/29/we-had-to-go-it-alone-how-the-uk-got-ahead-in-the-covid-vaccine-race

Because assignment was genuinely random, the groups are only roughly equal sized. 2042 were assigned to the control group, 2160 to the negative treatment group, and 2292 to the positive treatment group.

The bold highlighting of the text to focus on ‘this time last year’ was present in the actual survey question shown to respondents.

Technically the gap between the June 2020 and our experiment is closer to 11 months, and varies slightly across individual respondents since each survey is conducted over four weeks and respondents can choose when exactly they take part within that time frame. Our use of the phrase, ‘thinking back to this time last year’ reflects a desire for a question that is simple to read and understand. For our purposes in this experiment, it only really matters that respondents are prompted by this question to think back to before the vaccine rollout, when the UK’s performance became much more positive relative to other countries.

One small difference is that the experimental treatments, outlined in the next section, seems to have had a slightly smaller effect on Labour partisans than on Opposition partisans as a whole, in the specific case of overall performance evaluations (see Tables A5.2 and A5.3 in Appendix 5 of the Supplementary Material). We assume this reflects slightly less malleable opinions of the UK’s pandemic performance among Labour partisans, but the coefficients are in the same direction so this may also be simply a product of differences in sample size.

Interestingly, we find that our experimental manipulations were, if anything, slightly more impactful for voters with high levels of political attention than for those reporting low levels of attention (see Table A5.3 in Appendix 5 of the Supplementary Material). This might suggest that the information we provided in our experiments was already known by even the less politically attentive, who were not more affected by it than their more attentive counterparts, or that the less attentive paid less attention to the cues.

References

Achen, C. H., & Larry M. B.(2016). Democracy for realists: Why elections do not produce responsive government. Princeton studies in political behavior. Princeton.

Anderson, C. J. (2000). Economic voting and political context: A comparative perspective. Electoral Studies, 19(2–3), 151–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0261-3794(99)00045-1

Anderson, C. J. (2007). The end of economic voting? Contingency dilemmas and the limits of democratic accountability. Annual Review of Political Science, 10(1), 271–296. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.050806.155344

Anderson, C. J., Mendes, S. M., & Tverdova, Y. V. (2004). Endogenous economic voting: evidence from the 1997 British election. Electoral Studies, 23(4), 683–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2003.10.001

Bartels, L. M. (2002). Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Political Behavior, 24(2), 117–150. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1021226224601

Bavel, J. J. (2018). The partisan brain: An identity-based model of political belief. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(3), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.01.004

Becher, M., Sylvain B., & Daniel S. (2023). "Endogenous benchmarking and government accountability: Experimental evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic.” British Journal of Political Science.

Bisbee, J., & Da In, D. (2022). Objective facts and elite cues: Partisan responses to COVID-19. Journal of Politics, 84(3), 1278–1291.

Bisgaard, M. (2015). Bias will find a way: Economic perceptions, attributions of blame, and partisan-motivated reasoning during crisis. The Journal of Politics, 77(3), 849–860. https://doi.org/10.1086/681591

Brown, A. R. (2010). Are governors responsible for the State Economy? Partisanship, blame, and divided federalism. The Journal of Politics, 72(3), 605–615. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381610000046

Butler, D., & Stokes, D. (1969). Political Change in Britain: The Evolution of Electoral Choice. Macmillan.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American Voter. University of Chicago Press.

Castelli, L., & Carraro, L. (2011). Ideology is related to basic cognitive processes involved in attitude formation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(5), 1013–1016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.03.016

Chzhen, K., Evans, G., & Pickup, M. (2014). When do economic perceptions matter for party approval? Political Behavior, 36(2), 291–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9236-2

Evans, G., & Andersen, R. (2006). The political conditioning of economic perceptions. The Journal of Politics, 68(1), 194–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00380.x

Fieldhouse, E., Jane, G., Geoffrey, E., Jon, M., & Chris, P. (2021). British Election study internet panel waves, 19–21. Accessed March 26, 2021.

Fiorina, M. (1981). Retrospective Voting in American Presidential Elections. Yale University Press.

Flynn, D. J., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2017). The nature and origins of misperceptions: understanding false and unsupported beliefs about politics. Political Psychology, 38, 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12394

Frenda, S. J., Knowles, E. D., Saletan, W., & Loftus, E. F. (2013). False memories of fabricated political events. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(2), 280–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.10.013

Gadarian, S. K., Sara W. G., Thomas B. P., (2022). Pandemic Politics: The Deadly Toll of Partisanship in the Age of COVID, Princeton University Press, Princeton; https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691218991/pa politics.

Gaines, B. J., Kuklinski, J. H., Quirk, P. J., Peyton, B., & Verkuilen, J. (2007). Same facts, different interpretations: Partisan motivation and opinion on Iraq. The Journal of Politics, 69(4), 957–974. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00601.x

Gerber, A., & Green, D. (1999). Misperceptions about perceptual bias. Annual Review of Political Science, 2(1), 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.189

Gomez, B. T., & Matthew Wilson, J. (2003). Causal attribution and economic voting in American congressional elections. Political Research Quarterly, 56(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290305600303

Gov.U. K. (2023). Covid-19 – General public opinion tracker. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-general-public-opinion-tracker

Graham, M. H., & Singh, S. (2023). An outbreak of selective attribution: Partisanship and blame in the COVID-19 pandemic. American Political Science Review. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055423000047

Green, D., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan Hearts & Minds: Political Parties and the Social Identities of Voters. Yale University Press.

Green, J., Evans, G., & Snow, D. (2020). The government is losing support over its handling of coronavirus, especially among its new 2019 voters. Technical report. Nuffield Politics Research Centre. https://www.nuffield.ox.ac.uk/media/4396/covidattitudesreport.pdf

Greene, C., Robert N., & Gillian M. (2020). Misremembering brexit: Partisan bias and individual predictors of false memories for fake news stories among Brexit voters. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/dqjk4

Healy, A., Kuo, A. G., & Malhotra, N. (2014). Partisan bias in blame attribution: When does it occur? Journal of Experimental Political Science, 1(2), 144–158. https://doi.org/10.1017/xps.2014.8

Hellwig, Timothy. (2012). Constructing accountability: Party position taking and economic voting. Comparative Political Studies, 45(1), 91–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414011422516

Hellwig, T., & Marinova, D. M. (2014). More misinformed than myopic: Economic retrospections and the voter’s time horizon. Political Behavior, 37(4), 865–887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-014-9295-z

Hobolt, S. B., & James T. (2014). “Blaming Europe?”. In Blaming Europe?, (pp. 2–7). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199665686.003.0001.

Hobolt, S. B., Tilley, J., & Banducci, S. (2013). Clarity of responsibility: How government cohesion conditions performance voting. European Journal of Political Research, 52(2), 164–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02072.x

Jacobson, G. C. (2010). Perception, memory, and partisan polarization on the Iraq war. Political Science Quarterly, 125(1), 31–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-165x.2010.tb00667.x

Johnston, R., Sarker, R., Jones, K., Bolster, A., Propper, C., & Burgess, S. (2005). Egocentric economic voting and changes in party choice: Great Britain 1992–2001. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties, 15(1), 129–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/13689880500064692

Key, V. O. (1966). The responsible electorate. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674497764

Klymak, M., & Vlandas, T. (2022). Partisanship and Covid-19 vaccination in the UK. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23035-w

Koriat, A., Goldsmith, M., & Pansky, A. (2000). Toward a psychology of memory accuracy. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 481–537. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.481

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498.

Lebo, M. J., & Cassino, D. (2007). The aggregated consequences of motivated reasoning and the dynamics of partisan presidential approval. Political Psychology, 28(6), 719–746. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2007.00601.x

Leeper, T. J., & Slothuus, R. (2014). Political parties, motivated reasoning, and public opinion formation. Political Psychology, 35(January), 129–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12164

Lodge, M., & Charles S. T. (2013). The Rationalizing Voter. Cambridge studies in public opinion and political psychology. Cambridge University Press. New York

Malhotra, N., & Kuo, A. G. (2008). Attributing blame: The public’s response to hurricane katrina. Journal of Politics, 70(1), 120–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381607080097

Marsh, M., & Tilley, J. (2009). The attribution of credit and blame to governments and its impact on vote choice. British Journal of Political Science, 40(1), 115–134. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007123409990275

McCabe, K. T. (2016). Attitude responsiveness and partisan bias: direct experience with the affordable care act. Political Behavior, 38(4), 861–882. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109016-9337-9

Mercier, H., & Sperber, D. (2017). The enigma of reason: A New Theory of Human Understanding. Harvard University Press.

Murphy, G., Loftus, E. F., Grady, R. H., Levine, L. J., & Greene, C. M. (2019). False memories for fake news during ireland’s abortion referendum. Psychological Science, 30(10), 1449–1459.

Nawara, S. P. (2015). Who is responsible, the incumbent or the former president? Motivated reasoning in responsibility attributions. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 45(1), 110–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/psq.12173

Nielsen, R. K., Richard F., Antonis K., & Felix S. 2020. Communications in the coronavirus crisis: lessons for the second wave”. Final Report, UK COVID-19 new and information project, 27th October, https://doi.org/10.60625/risj-0666-xv66

Parker-Stephen, E. (2013). Tides of disagreement: How reality facilitates (and inhibits) partisan public opinion. The Journal of Politics, 75(4), 1077–1088. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381613000789

Powell, G. B. (2000). Elections as instruments of democracy: Majoritarian and proportional visions. New Haven, Connecticut.

Powell, G. B., & Whitten, G. D. (1993). A cross-national analysis of economic voting: Taking account of the political context. American Journal of Political Science, 37(2), 391–414. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111378

Redlawsk, D. P., Civettini, A. J. W., & Emmerson, K. M. (2010). The affective tipping point: Do motivated reasoners ever “Get It”? Political Psychology, 31(4), 563–593. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00772.x

Rodriguez, Cristian G., Shana K. G., Sara W. G., & Thomas P. (2020). Morbid polarization: Exposure to COVID-19 and partisan disagreement about pandemic response. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/wvyr7.

Rudolph, T. J. (2003). Institutional context and the assignment of political responsibility. The Journal of Politics, 65(1), 190–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.00009

Rudolph, T. J. (2003). Who’s responsible for the economy? The formation and consequences of responsibility attributions. American Journal of Political Science, 47(4), 698–713. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5907.00049

Rudolph, T. J. (2006). Triangulating political responsibility: The motivated formation of responsibility judgments. Political Psychology, 27(1), 99–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14679221.2006.00451.x

Rudolph, T. J., & Tobin Grant, J. (2002). An attributional model of economic voting: Evidence from the 2000 presidential election. Political Research Quarterly, 55(4), 805–823. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290205500404

Sirin, C. V., & Villalobos, J. D. (2011). Where does the buck stop? Applying attribution theory to examine public appraisals of the president. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 41(2), 334–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5705.2011.03857.x

Sniderman, P. M., Brody, R. A., & Tetlock, P. E. (1991). Reasoning and choice : Explorations in political psychology. Cambridge University Press.

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x

Tilley, James, & Hobolt, Sara B. (2011). Is the government to blame? An experimental test of how partisanship shapes perceptions of performance and responsibility. The Journal of Politics, 73(2), 316–330. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381611000168

Tufte, E. R. (1978). Political control of the economy. Princeton University Press.https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691219417.

VanDusky-Allen, J. A., Utych, S. M., & Catalano, M. (2022). Partisanship, policy, and americans’ evaluations of state-level COVID-19 policies prior to the 2020 election. Political Research Quarterly, 75(2), 479–496.

Wilcox, N., & Wlezien, C. (1993). The contamination of responses to survey items: Economic perceptions and political judgments. Political Analysis, 5, 181–213. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/5.1.181

Wlezien, C., Franklin, M., & Twiggs, D. (1997). Economic perceptions and vote choice: Disentangling the endogeneity. Political Behavior, 19(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024841605168

Yeandle, A., & Maxia, J. (2023). Partisanship, attribution and approval in a public health shock. Electoral Studies, 84, 102643.

Zaller, J. (1994). “Elite leadership of mass opinion: New evidence from the Gulf War.” In Lance B. & David L. P. (Eds.), Taken by Storm: Public Opinion and US Foreign Policy in the Gulf War, (pp. 186–209). University of Chicago Press.

YouGov. (2023). Covid-19: government handling and confidence in health authorities. https://yougov.co.uk/international/articles/29429-perception-government-handling-covid-19?redirect_from=%2Ftopics%2Finternational%2Farticles-reports%2F

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Nuffield Politics Research Centre for funding this experiment. We thank Jane Green for her instrumental help in designing this experiment, and thank Stephen Fisher and Mathis Ebbinghaus for comments on previous drafts of this article. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Oxford Political Psychology workshop, and the 2022 EPSA conference in Prague, and we are grateful to participants at these events for their helpful comments and suggestions. Any remaining imperfections are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Snow, D., Evans, G. Partisanship in a Pandemic: Biased Voter Assessments of Past and Present Government Performance. Polit Behav (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-024-09929-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-024-09929-7