Abstract

Voters hold governments to account through elections, but which criteria are most important to voter evaluations of incumbent performance? While (economic) outcomes have long been central to studies of retrospective voting, recent studies have considered the influence of policy output—the policies implemented by incumbents to achieve their goals. Building on this promising development, this study identifies three ways in which policy output is expected to affect voter evaluations of incumbent performance—the congruence between implemented policy and (1) individual preferences; (2) public opinion; and (3) election pledges. A discrete choice experiment was designed to assess the relative importance of these three aspects of policy output in comparison to each other; as well as to two important economic indicators. Overall, the findings support the notion that policy output matters to voters even beyond outcomes. The findings also show that voters value congruence between policy and their personal preferences considerably more than policy congruence with public opinion; and election pledge fulfillment. This indicates that voters are egotropic in their evaluation of implemented policy, and more policy-seeking than accounted for in much of the empirical retrospective voting literature. These results inform our understanding of how policy output matters to voters, as well as of how voters hold governments accountable for their performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A central principle in most conceptions of representative democracy is that voters hold governments accountable through elections. The findings of a large number of studies on retrospective voting have provided empirical support for the principle that incumbents’ re-election is contingent upon voter evaluations of their tenures in office (see for overviews e.g., Ashworth 2012; Healy and Malhotra 2013). Therewith, voter evaluations of prior performance can be an important determinant of vote choice, even if it is by no means the only one. The focus of this study lies entirely on the retrospective component of a vote decision, namely the overall evaluation of an incumbent’s performance—namely, which performance criteria are most important to these evaluations? While most empirical studies to date have focused on the consideration of economic outcomes (see also Anderson 2007), a growing body of work is attesting to the importance of non-economic performance indicators to voter evaluations (see e.g., Healy and Malhotra 2013). These indicators include both non-economic policy outcomes—i.e., the effects of implemented government policy on society (e.g., De Vries et al. 2011; Giger and Nelson 2011; Tilley and Hobolt 2011; De Vries and Giger 2014; Gidengil and Karakoç 2016); as well as policy output—i.e., the policies implemented by incumbents to achieve their goals (e.g., Healy and Malhotra 2009; Bechtel and Hainmueller 2011; Gasper and Reeves 2011; Corazzini et al. 2014; Born et al. 2018; Naurin et al. 2019b; Matthieβ 2020; see also Healy and Malhotra 2013).

This study is particularly interested in the role of policy output in voter evaluations of government performance. While attention for the effects of policy output is on the rise in studies of retrospective voting, no comprehensive account has thus-far reconciled the various ways in which policy output may affect incumbent evaluations—nor has the relative importance of policy output for incumbent evaluations been explicitly compared to that of economic outcomes. Therein lies the dual aim of this paper, to study how, and how much the policies implemented by incumbents matter to voters. Drawing on the notion that voters are policy-seekers coined by influential classic accounts of representative democracy (e.g., Downs 1957) and supported by recent empirical work (e.g., Esaiasson et al. 2016; Naurin et al. 2019b; Werner 2019), three ways were identified in which policy output should matter to voters. These were the congruence between policy output and election manifestos (i.e., election pledge fulfillment); between policy output and public opinion (i.e., policy congruence with majority preferences); and between policy output and individual preferences (i.e., policy congruence with individual preferences). The relative importance of these three aspects of policy output to incumbent evaluations was compared to each other, as well as to sociotropic and egotropic economic considerations through a discrete-choice experimentFootnote 1 conducted on 1786 respondents in Sweden.

Thus, the scientific contribution of this study is twofold. First, this study contributes to the knowledge of how policy output matters to voters by identifying three competing aspects of policy output and comparing their relative importance to voter evaluations. Second, by comparing the relative importance of various aspects of policy output to that of important economic indicators—this study enhances the understanding of evaluations of government performance beyond economic outcomes and non-economic policy outcomes. Therewith, the findings of this study inform the literatures that address the relevance of various aspects of policy output, such as policy congruence with majority preferences and election pledge fulfillment, to voters; as well as the wider literature that seeks to understand how voters hold incumbents accountable for past performance. The latter aspect is also where this study finds its societal relevance. The results of this study expand existing knowledge on what voters believe to constitute good government, and how incumbent political actors may be held accountable for various aspects of their performance in a democracy.

In brief, the most important findings of this study are that policy output is important to voter evaluations of government performance, even beyond outcomes. Voters also value congruence between policy and their personal preferences considerably more than policy congruence with public opinion and election pledge fulfillment. These findings indicate that voters are primarily egotropic in their evaluation of implemented policy, and that voters may be considerably more policy-seeking than accounted for in much of the empirical retrospective voting literature.

Before addressing the experimental design of this study, the following sections first provide a review of the relevant literatures. After a brief discussion of the central premise of retrospective voting, the findings from previous work on voter evaluations of incumbent performance are discussed. This discussion then provides the foundation for the theoretical argument of this study, that policy output should matter to voters in three important ways; through its congruence with individual voter preferences; public opinion; and election pledges, leading up to the specific questions addressed in the experiment of this paper.

Previous work and theoretical background

Evaluations of government performance

That voter evaluations of government performance are important is attested to by a large body of literature that underlines the importance of retrospective voting for democratic accountabilityFootnote 2 (see for an overview Healy and Malhotra 2013). Expanding on the classic insights on retrospective voting (e.g., Key and Cummings 1966; Kramer 1971; Fair 1978; Fiorina 1981), it has been argued that retrospective voting allows voters to sanction poor performing incumbents (Ferejohn 1986) and select future leaders that have proven themselves to govern in a competent and honest manner; while removing from office those that have exhibited the opposite (Fearon 1999; see Healy and Malhotra 2013). This entails that the re-election of an incumbent in subsequent elections is conditional upon voter perceptions of the incumbent’s tenure in office preceding the elections.

While vote choices are notoriously complex decisions, it is well-established that evaluative retrospection forms an important part of voter psychology when it comes to incumbent re-election. In order for voters to vote retrospectively, there needs to be a reflection or evaluation of some sort on the voters’ part—which is the primary focus of this study. The notion that voter evaluations of incumbents’ prior performance underlie incumbents’ chances for re-election puts forth an important question: based on which criteria do voters evaluate incumbents? Arguably, the aspects of incumbent performance that matter most to voters can be viewed as an extension of voters’ representational preferences (e.g., Carman 2007; Bengtsson and Wass 2010; Werner 2019). A central theme in studies on voters’ representational preferences is that different views on democratic representation suppose varying degrees of discretionary freedom available to representatives to serve the interests or will of the people they represent (e.g., Pitkin 1967; Fox and Shotts 2009; Bengtsson and Wass 2010). Applied to evaluation criteria of incumbent performance, if voters allot their incumbents a limited degree of discretionary freedom, the incumbents’ actions—i.e., policy output—should be the primary performance criterion. When larger amounts of discretionary freedom are apportioned to incumbents, voters’ primary focus should be on policy outcomes instead—i.e., the perceived consequences of government action for society.

Most empirical studies interested in the evaluation criteria voters use when deciding to re-elect an incumbent, to date, have focused on the importance of outcomes (see Healy and Malhotra 2013). Recent developments in the study of retrospective voting have led scholars to consider non-economic policy outcomes in domains such as social policy (Giger and Nelson 2011), health care (Tilley and Hobolt 2011), and European integration policy (De Vries et al. 2011). Some studies have also addressed a wider spectrum of non-economic outcomes at once (Fournier et al. 2003; Hellwig 2008; Boyne et al. 2009; De Vries and Giger 2014; Gidengil and Karakoç 2016). However, the vast majority of studies on retrospective voting have focused on economic outcomes—aiming, among others, to determine whether voters evaluate short-term or longer term economic development (e.g., Hellwig and Marinova 2015; Wlezien 2015; Jankowski 2018); the global, national, or subnational economy (e.g., Atkeson and Partin 1995; Carsey and Wright 1998; Ragusa and Tarpey 2016; Thorlakson 2016; González-Sirois and Bélanger 2019); which economic indicators voters find most important (e.g., Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier 2000; Bélanger and Lewis-Beck 2004; Van der Eijk et al. 2007; Stevenson and Duch 2013); and whether voters are primarily concerned with macro-level economic development in the form of sociotropic considerations, or with the development of their personal finances, i.e., egotropic or pocketbook considerations (e.g., Kiewiet and Lewis-Beck 2011; Stubager et al. 2014; Healy et al. 2017). A few notable studies have also undertaken to compare the relative importance of economic to non-economic outcomes such as the development of crime rates, and property values during an incumbent’s tenure for the evaluation of that incumbent’s performance (e.g., Singer 2011; Holmes and Gutiérrez de Piñeres 2013; Hopkins and Pettingill 2018). These comparisons, however, have not typically included performance criteria pertaining to policy output (see also Healy and Malhotra 2013, p. 289).

Policy performance

Despite the implicit assertion of much of the empirical literature that what voters care about in incumbent performance is outcomes, a compelling argument is to be made for the importance of policy output as well. What incumbents (do not) do, arguably reflects more directly on their performance than the outcomes that may be attributed to their actions. For example, if a government implements a certain labor policy, this constitutes an active choice on the government’s part. However, if unemployment decreases, this may be the result of a policy choice made by the government; but it could also be due to global economic trends arguably well beyond the reach of that government.

Classic accounts of representative democracy apportion a pivotal role to policy performance. If voters are policy-seekers (Downs 1957), not only should the policy proposals contained in election manifestos allow voters to elect governments with favorable policy agendas prospectively (e.g., Downs 1957; Dahl 1991; Grossback et al. 2005; McDonald and Budge 2005; Elinder et al. 2015)—it should also allow them to base re-election decisions on the policies that were, and those that were not, implemented by these governments. This is an important theme in mandate models of democratic representation, as well as in the study of election pledges (e.g., Klingemann et al. 1994; Naurin et al. 2019a).

The idea that incumbents’ actions affect voters is further supported by recent empirical findings. For example, several studies have underlined that voters care about incumbents’ preparedness for, and response to natural disasterFootnote 3 (Healy and Malhotra 2009; Bechtel and Hainmueller 2011; Gasper and Reeves 2011). Other studies have found that congruence in policy positions between constituents and incumbents affects incumbents’ chances for re-election (e.g., Hogan 2008; Kassow and Finocchiaro 2011). It has also been found that voters select representatives prospectively based on the policy they propose prior to elections (e.g., Lachat 2011; Elinder et al. 2015; see also Weldon and McNeney 2019)—and more importantly, that incumbents’ delivery on those proposals matters to voter evaluations of government performance (Naurin et al. 2019b), and retrospective vote choice (Corazzini et al. 2014; Born et al. 2018; Matthieβ 2020).

What policy output represents to voters, and whether this meaning extends beyond the perceived outcomes of implemented policies, has received lesser attention in empirical work. This paper identifies three important values of democratic representation that policy output should appeal to in voters. First, if voters are indeed policy-seekers (Downs 1957), they should find it important that their government implements policy that corresponds to their policy preferences. Second, following the fundamental principles of majoritarian rule and government responsiveness in representative democracy (see e.g., Canes-Wrone 2015), voters should find it important that implemented policy is an expression of public opinion—i.e., majority preferences. Finally, if governments are expected to be honest, predictable, and capable, voters should want them to implement the policies they promised prior to taking office—i.e., fulfill their election pledges (see Naurin 2011; Naurin et al. 2019a).

These values are not mutually exclusive per definition. If a voter’s preferences are in line with public opinion (as they should be for the majority of voters), both those values can be appealed to by implementing the same policy. Similarly, if a voter selects a representative based on a certain election pledge they made prior to the election, implementing the policy contained in that pledge does not only pertain to pledge fulfillment, but also to satisfying that voter’s policy preferences (see Naurin et al. 2019b). That said, political conditions tend to change over time (Stokes 2001), and policy preferences are not set in stone (e.g., Page and Jones 1979; Carsey and Layman 2006). A voter’s policy preferences will not typically correspond entirely to any candidate’s policy platform even before the election; voters will find themselves in situations where their policy preferences will not be in line with public opinion; and the policy positions of voters, society, and incumbents may diverge. In those situations, do voters find it more important that an incumbent produces policy that is in line with their own preferences; public opinion; or the incumbent’s election manifesto?

This exact question has not been posed by an empirical study thus-far, but similar topics have been addressed in recent work. A study by Esaiasson et al. (2016) on the responsiveness-acceptance connection found that voters that are dissatisfied with a policy decision are unlikely to reward the decision-maker for its responsiveness to majority opinion. A study by Naurin et al. (2019b) of the effects of broken and fulfilled election pledges on voter evaluations of government performance found that voters may punish incumbents for implementing policies that correspond to the incumbent’s election manifesto, if the implemented policy does not correspond to those voters’ individual preferences. Finally, a recent study by Werner (2019) of voters’ representational preferences found that while voters value parties’ election pledge fulfillment highly, they prioritize favorable policy outcomes or ‘enactment of the common good’ over policy output in the form of pledge fulfillment and policy responsiveness to public opinion. In conjunction, these findings suggest that voters find both policy outcomes, and congruence of policy output and individual preferences more important than congruence of policy output and majority preferences or election pledges. However, no comprehensive study has thus-far compared the relative importance of all these aspects simultaneously, and whether voters find it more important that policy output corresponds to their preferences, or that favorable outcomes are obtained, consequently has not been tested. Bridging that gap is an important aim for this study.

Theoretical expectations

The aim of this paper is to study how, and how much, incumbents’ policy output matters to voter evaluations of government performance. This aim produces two concrete empirical questions for the study to focus on. First, to determine how policy output matters to voter evaluations: are voter evaluations of government performance more affected by congruence of incumbents’ policy output to individual preferences; to public opinion; or to the incumbents’ election pledges? The second question pertains to the aim to determine whether the effects of policy output extend beyond the more-established effects of policy outcomes. To that end, the identified ways in which policy output should affect voter evaluations were compared to two well-established measures of outcome-based performance indicators. These were the development of the national economy and voters’ personal finances during the incumbents’ tenure in office—pertaining to sociotropic and egotropic economic voter considerations, respectively. The second question was formulated as follows: are voter evaluations of government performance more affected by policy output than by the development of the national economy, or voters’ personal finances over the incumbents’ term?

As discussed in the previous subsection, this study has identified and selected five important evaluation criteria for voter evaluations of incumbent performance, and compares their relative importance to overall incumbent evaluations. These five criteria are policy congruence with majority preferences (i); individual preferences (ii); election pledge fulfillment (iii); development of the national economy (iv); and development of personal finances (v). These five criteria all come with the straightforward hypothesis that better performance on that given criterion leads to more positive evaluations of an incumbent’s overall performance, and that lower performance on each criterion leads to more negative evaluations. No additional hypotheses were formulated with regard to the relative importance of the criteria, as compared to each other, to voter evaluations of government performance. Instead, their comparison, and the conflicting theoretical expectations that policy outcomes (i.e., the economy) should matter most and that policy output should be most important to voter evaluations, are taken as the guiding focus of the empirical part of this study.

Data and design: a discrete choice experiment

To compare the relative importance of the five evaluation criteria for voter evaluations of incumbent performance, a discrete choice experiment was designed—an increasingly used method in political science, which has proven to be useful for studying multi-dimensional political preferences (e.g., Hansen et al. 2015; Knudsen and Johannesson 2019).Footnote 4 The experiment was conducted in Sweden in June 2019, in wave 34 of the Laboratory of Opinion Research (LORE). LORE is an organization within the University of Gothenburg, devoted to conducting data collection through web questionnaires. Collection of data in collaboration with LORE is performed through a number of web panels, of which the Citizen Panel is the largest with more than 60,000 active respondents in Sweden.Footnote 5 The gross subsample size of the non-probability sample was 3200. At least partial responses were provided by 1988 respondents, and 1786 respondents finished the experiment (56%). The gross sample was pre-stratified by age, education, and gender—and was therein representative of the Swedish population aged 18–70.

In this experiment, each respondent was provided with one discrete choice task pitting against each other two fictive former government parties. The tenures of both these parties were concisely described to the respondent, in terms of five attributes: the development of the national economy; the development of the respondents’ personal finances; the pledge fulfillment of the party; the congruence of the party’s implemented policy to public opinion; and the congruence of the party’s implemented policy to respondents’ personal preferences. All these five attributes were assigned three possible values—positive, negative, and neutral. Sociotropic economic considerations were operationalized in terms of development of the Swedish national economy. Following the growing amount of evidence that voters use cross-national benchmarks (e.g., Kayser and Peress 2012; Hansen et al. 2015; but see also Arel-Bundock et al. 2019) or reference points (Aytaç 2018) when evaluating the economy, respondents were presented with benchmarked information about the development of the Swedish economy compared to the EU-average. Pocketbook considerations were defined in terms of the development of respondents’ personal finances. Pledge fulfillment was described as the degree to which the respective parties fulfilled the promises they made prior to being elected. Policy congruence with majority preferences was presented as the degree to which the respective parties’ implemented policies corresponded to public opinion. Finally, policy congruence with individual preferences was incorporated as the congruence between implemented policy and the respondents’ own preferences. An example of a party profile that the respondents were confronted with can be found in the supplementary material (p. 3). Table 1 provides an overview of the attributes included in the scenarios, and the values they were allowed to take on.Footnote 6

After the confrontation with two competing party profiles, respondents chose whether they would vote for former government party A or B; and evaluated on a scale from 1 to 7 for the separate parties’ tenure in officeFootnote 7—all based on the provided information. A full description of the experiment can be found in the supplementary material (pp. 1–4).

The use of a discrete choice experiment offered two tangible advantages to other methodologies for answering the questions posed in this study (see Hainmueller et al. 2014; Knudsen and Johannesson 2019). First, the chosen design allowed for simultaneous, isolated estimation of the influence of a larger number of evaluation criteria on voters’ evaluations of government performance than a typical survey experiment would have. It also allowed for an exclusive focus on retrospective considerations. Second, the design enabled fulfilling the aim of this study to compare the relative contribution of these five criteria to overall evaluations of government performance. Moreover, it has been argued that the use of scenarios in a discrete choice experiment provides voters with an easier and more realistic choice, than if they were asked to specify the relative importance of various criteria themselves; and that there are statistical and cognitive benefits of asking voters to compare combinations of attributes in scenarios (see Hansen et al. 2015). It is important to note that this study does not provide a full model of vote choice; only the retrospective aspect of a vote choice, namely the evaluation of government performance, is studied in this design. Asking the respondents whom they would vote for, however, forces the respondents to prioritize evaluation criteria and choose which they find most important. The secondary dependent variable question, in which respondents rated the competing party profiles individually, does not force the respondents to make such a choice. Respondents can provide the same evaluation to both party profiles, irrespective of which information is supplied in these profiles. This question is mostly asked in a supporting fashion to the understanding of the central dependent variable question, the choice task. Indeed, it is the choices that the respondents make together, as a sample, that answer the question which performance criteria voters truly find of most importance in evaluating incumbents. As a potential moderator, the ratings task is placed after the choice task in the experimental design.

The analysis of the results was conducted in accordance with the influential standards set out by Hainmueller et al. (2014)—with a small modification. The unit of analysis was the choice task, consisting of two party profiles, instead of the party profile itself. This decision follows from the deliberate choice to restrict the number of choice tasks per respondent to one. As thoroughly argued by Franchino and Zucchini (2015), the common approach of presenting several choice tasks and correcting for repeated measurements in the statistical analysis can create a problem with the number of degrees of freedom available in those analyses. In such designs, the number of choice tasks needs at the very least to be greater than the number of included attributes to allow for simultaneous regression of all attributes. Moreover, if interaction effects are included or non-linear analyses are required, the number of required choice tasks increases to heights that cannot be reasonably accommodated by most experiments; and even if that were possible, questions should arise about the cognitive challenges such experiments would pose to respondents. This study sought to circumvent the problems of limited degrees of freedom, or a challenging number of choice tasks for respondents, by eliminating repeated measurements from the equation. This way, the standard errors did not need to be clustered on the respondent level, and the degrees of freedom available were plentiful. However, even with only one choice task, if the unit of analysis were set to party profile instead of choice task, two measurements per respondent would still be included. This would likewise impede the availability of degrees of freedom. To accommodate the use of the discrete choice task (0 for party A; 1 for party B) as the unit of analysis, the attributes provided for both party profiles included in the task were also included in the regression analysis. This way, the trade-offs underlying the respondents’ choice are also accounted for in the model.

With regard to other common concerns in the design of discrete choice experiments, attribute order was randomized per respondent to rule out the influence of ordering and primacy effects; and attribute orthogonality was achieved by design as no possible combinations of attribute values were excluded (see Hainmueller et al. 2014; Franchino and Zucchini 2015; Knudsen and Johannesson 2019). In order to address the recent criticism of using Average Marginal Component Effects (AMCEs) for studying voter preferences (see Abramson et al. 2019), several robustness checks were conducted to further validate the direction of the observed effects, and in particular the relative importance of the competing attributes for respondents' evaluations of government performance. The main findings of relevance to the interpretation of the results are reported along the regression coefficients in the next section where important, while more on the underlying analyses can be found in the supplementary material (pp. 5–6). In addition, it should be noted that Bansak et al. (2020) make a strong case for the continued viability of AMCE usage in political science research.

On top of the referenced general advantages of using discrete choice experiments for studying voter preferences, the particular design here has a few additional benefits. Omitting party labels other than the generic terms ‘Party A’ and ‘Party B’ removes the need to provide false information to respondents, and eliminates the risk of evaluations being affected by partisan bias. An important implication of this choice is that the findings of this study rely on the assumption that partisan bias would affect how voters process performance information on all included evaluation criteria equally. While this is arguably not an unreasonable assumption, its accuracy cannot be tested with the available data, and the degree to which the assumption may be false, takes away from the external validity of the findings. That said, the results should still provide a reliable estimate for the relative importance of the included evaluation criteria for any given voter that is either attached, or not attached to the incumbent party in question.

Attributing responsibility for the presented performance-related information to the appropriate actor was further simplified by its assignment to individual parties—not government coalitions (see e.g., Fisher and Hobolt 2010; Giuliani and Massari 2019). In addition, many potential problems associated with voter awareness and attribution are circumvented by the fact that voters are explicitly told what the government tenure of these parties entailed. As this study is primarily interested in determining which criteria voters find most important for evaluating incumbents, creating scenarios in which voters possess all important information is an elementary prerequisite. Indeed, such a comparison would be fatally hampered if respondents were unaware of certain performance-related information, or if they were to attribute responsibility for this information to the wrong actor. The possibility to isolate effects offered by the design of this discrete choice experiment is therefore very important. In addition, a serious challenge would be posed to the results of the comparison if respondents were to disagree with any of the performance-related information provided. This notion also motivated the decision not to include specific policy information in the scenarios—as it would make the analysis vulnerable to concerns as mismatching definitions of what constitutes an election pledge (e.g., Naurin 2011; Dupont et al. 2019); when pledges can be considered fulfilled/when a policy can be considered implemented; effects of varying policy preferences or perceptions of public opinion; etc. Similar measures were taken to insure the analysis against voter myopia—no alternative timeframe is offered; and level concerns in economic perceptions—the national economy is addressed for former national government parties.

Also, while the abstract formulations used may decrease how realistic the scenarios are, they help improve the comparability of the included attributes. Using concrete measures would have required assumptions on how many percent an economy should grow, or how many percent of election pledges should be fulfilled for it to count as a ‘good outcome’ or ‘good performance’. Even if reliable estimates could have been obtained from earlier work, it would have been a tough sell to argue that such estimates would represent an equal or at least similar distribution of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ performance across attributes for all respondents. Using fictive information and abstract formulations allowed for a clear division of information in more positive, and more negative information, as compared to the reference (‘neutral’) category. Still, no assumptions are made about the perceived equidistance of these values per and across attributes—and arguably such assumptions are unnecessary when the hypothesized direction of the effect is clear (see Hainmueller et al. 2014). This condition is easier to satisfy with abstract than with concrete information, and with fewer possible values per attribute. For all included attributes here, the theoretical expectation is that more positive outcomes or performance are associated with more positive evaluations of incumbent evaluations; and all attributes can only take on three values. Thus, for determining the relatively importance of the included evaluation criteria to voter evaluations of government performance, comparing the effects of more positive performance information and more negative performance information per attribute should provide a reliable estimate of the ranked importance of the included attributes.

There was an important trade-off between the internal and external validity of the experiment behind these considerations. While the fictiveness of the scenarios, the direct delivery of information, and the deliberate vagueness of some of that information in the treatments helped in isolating the effects this study aimed to obtain, this had a natural cost in the generalizability of the results and therewith the external validity of this study. Indeed, the results of this study can only speak to the retrospective considerations of voters, i.e., their evaluations of prior government performance, and which criteria they find most important to form these evaluations. In addition, there is a possibility that voters would respond somewhat differently to more concrete or different performance information about an incumbent’s tenure in office. However, this study chose to generally prioritize internal validity over external validity, for the reason that many studies have been conducted on the effects of policy output and outcomes on voter evaluations in more realistic settings, but no studies to date have directly compared the importance of the five modes of performance to voters that are studied here. That is where this study makes its most important contribution.

Empirical results

The main results of the experiment are presented in Table 2. The table contains the coefficients of a simultaneous ordinary least squares (OLS) regression including all five attributes as independent variables for both party profiles (A, − 1 to 1; and B, − 1 to 1), and respondents choosing one party profile (‘Party B’, 1) over the other party profile (‘Party A’, 0) as the dependent variable.

The results confirm the basic expectations for all attributes. The predicted probability of respondents choosing party B over party A increases for positive values (i.e., good performance) for all attributes assigned to party B; while it decreases for negative values on all attributes assigned to party B. Reversely, the predicted probability of respondents choosing party B over party A decreases for positive values on all attributes assigned to party A; and increases for negative values on all attributes assigned to party A. In other words, the anticipated direction of the effects for all attributes is confirmed by the regression analysis. All else equal, respondents choose the party with a more positive value for each included indicator of government performance—as expected.Footnote 8

While the direction of the effects is the same for all attributes, their magnitude differs substantially. For both sociotropic and egotropic economic considerations, the estimated difference in predicted probability of party choice is 11–12% points. For policy congruence with individual preferences, this is 16–19% points; for policy congruence with public opinion 4–5% points; and for pledge fulfillment 7–9% points.

The relative importance ranking provided by these coefficients is upheld in the analysis of the percentages of respondents that preferred one party over the other for different values of the same attribute (see Supplementary Material, p. 5).

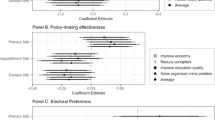

Figure 1 provides a visual overview of the change in predicted probabilities for various levels of disparity between party profiles, per attribute. This disparity was defined as the difference between the value for any attribute assigned to party A and the value for that same attribute assigned to party B, per choice task.Footnote 9

Difference in predicted probabilities of choosing party B over party A under various per attribute trade-off conditions, all else equal. Horizontal bars represent 95% confidence intervals; dots without horizontal bars represent the reference category (same attribute value for both parties in choice task). For all attributes, the four other categories represent the difference in predicted probability of choosing party B over party A compared to the reference category, if values provided for that attribute in a choice task were positive for party A and negative for party B (‘Party A + 2’); positive for party A and neutral for party B or neutral for party A and negative for party B (both ‘Party A + 1’); positive for party B and neutral for party A or neutral for party B and negative for party A (both ‘Party B + 1’); and positive for party B and negative for party A (‘Party B + 2’). The coefficients were obtained from an OLS regression analysis with dummy variables for these categories—excluding all reference categories—and party choice (party B = 1; party A = 0) as the dependent variable

The results presented in Table 2 and Fig. 1 indicate that what voters care most about in policy output is that incumbents act in accordance with their preferences; much less that implemented policy corresponds to public opinion or previously made promises. The AMCE recorded for the policy congruence with individual preferences attribute is more than twice as big as the AMCE for pledge fulfillment; and more than triple the size of the AMCE for policy congruence with majority preferences. Moreover, if respondents were presented with a choice task that had one party profile with a positive value for policy congruence with individual preferences versus one with a positive value for pledge fulfillment, or policy congruence with public opinion; respondents preferred the party associated with a positive value for individual preferences in 62 and 68% of the cases, respectively (see Supplementary Material, p. 6).

The results also indicate that voters care about policy output beyond its perceived outcomes. While the AMCEs for pledge fulfillment and policy congruence with majority preferences are smaller than for both sociotropic and pocketbook economic considerations, the AMCE for policy congruence with individual preferences is considerably larger. Indeed, a positive value for policy congruence with individual preferences increases the predicted probability of party choice by approximately 18% points, where positive values for either economic attribute increase this predicted probability by less than 12% points. Respondents presented with a choice task that had one party profile with a positive value for policy congruence with individual preferences versus one with a positive value for development of the national economy, or personal finances; respondents preferred the party associated with a positive value for policy congruence with individual preferences in 62% and 60% of the cases, respectively (see Supplementary Material, p. 6).

Similar but less pronounced results were recorded for the secondary dependent variable, the rating task (1–7). The most notable difference (see Supplementary Material, p. 12) was that when not forced to choose, and trade-off effects are thus of lesser importance, voters find economic outcomes and policy congruence with their preferences of approximate equal importance. Varying levels of political interest, self-reported ideology, age, income, and gender of the respondents were not found to materially change the reported effects (see Supplementary Material, pp. 13–19). In line with the prevailing consensus in studies on economic voting, respondents found the development of the national economy and their personal finances of similar importance.

Discussion and conclusion

This study set out to investigate how, and how much, incumbents’ policy output matters to voter evaluations of government performance. As expected, voters attach value to different aspects of government performance. Good performance on all included evaluation criteria is associated with better voter evaluations of government performance, while poor performance is associated with worse evaluations. As evidenced by the more balanced results obtained by the secondary dependent variable question included in the experiment, the ratings task, voters look for good performance on all criteria. However, when forced to choose, it is revealed what voters generally find most important when evaluating incumbents.

Overall, the findings support the central premise that the policy that incumbents implement is important to voters. This is in line with influential theoretical accounts of representative democracy that allocate an important role to policy output in accountability processes (e.g., Downs 1957; Dahl 1991). In particular, the findings illustrate that voters find it important that incumbents implement policy that corresponds to their preferences—much less so that implemented policy is in line with public opinion or incumbents’ election manifestos (pledge fulfillment). Moreover, the congruence between policy output and voters’ individual preferences was found to have a substantially greater impact on voter evaluations of government performance than economic outcomes in the form of either economic growth or development of voters’ personal finances. In summary, the findings indicate that voters seek government policy that represents their preferences, and in that way care about implemented policies even beyond their perceived outcomes.

These findings are in line with previous work that has argued for the importance of policy output to voters (e.g., Corazzini et al. 2014; Born et al. 2018)—and in particular with the notion that the congruence between policy output and voters’ individual preferences may matter more to evaluations of government performance than policy congruence with public opinion (Esaiasson et al. 2016) or election pledge fulfillment (Naurin et al. 2019b). As noted in studies on policy responsiveness (e.g., Esaiasson et al. 2016), voters want to ‘win’—and those who ‘lose’, are not consoled by the idea that incumbents are responsive and policy action is in line with majority preferences; nor that incumbents show predictability, capability, or honesty by implementing the policy agenda they promised to implement prior to the elections. This notion also resembles the concept of ‘recognition politics’ which posits that citizens care about their views and rights being reflected beyond their personal experiences with the outcomes of policy change (see Burlacu et al. 2018).

Of course, if incumbents are incentivized to implement policy that appeases as many as possible voters’ individual preferences—on aggregate, their policy output may still be responsive to public opinion/majority preferences. Similarly, since voters select representatives based on their policy proposals (e.g., Elinder et al. 2015), fulfilling pledges should to a large degree correspond to implementing desirable policy for an incumbent’s supporters. The important distinction, however, is that individual voters were found to care considerably more about the implemented policy corresponding to their own preferences, than to majority preferences or election pledges. Taken together, one possible implication is that voters are egotropic in their evaluation of implemented policy—caring about the recognition of their own views more than about the recognition of majority preferences. The notion that voters care more about themselves than society has recently received additional support in the literature on economic outcomes (Healy et al. 2017). However, when it comes to policy output rather than outcomes, it is possible that voters believe that the policy they personally support will ultimately benefit the rest of society as well.Footnote 10

The findings also provide encouragement to the signaled trend that the retrospective voting literature is starting to look beyond the economy (see e.g., Healy and Malhotra 2013). While the findings of this study, as well, support a pivotal role for both sociotropic and pocketbook considerations in incumbent evaluations—and that policy congruence with majority preferences and pledge fulfillment are less important than those considerations (Werner 2019)—they also provide a clear indication that voters care about more than the state of the economy and their personal finances. The literature on performance voting has already picked up on this notion (e.g., De Vries and Giger 2014; Gidengil and Karakoç 2016), but should also see the findings of this study as motivation to consider policy output in addition to policy outcomes.

Indeed, in terms of representational preferences, voters appear to place more emphasis on the actions of their representatives than commonly presumed. This suggests that voters allocate limited discretionary freedom to incumbents to obtain desirable outcomes by any means necessary (see e.g., Fox and Shotts 2009). In line with theories of mandate representation, the findings indicate that voters see obtaining favorable policy output itself as a form of performance, not as an—irrelevant—means to obtain favorable outcomes. Of course, in real world voting decisions different modes of incumbent performance are more entangled, performance information is not as readily available to voters, and evaluations are exposed to varying levels of influence of partisan bias; voter awareness; and clarity of attribution, especially in coalition governments. However, previous work has found that the media report in quite clear terms about policy promises and implementation (e.g., Kostadinova 2017; Duval 2019); that voters are quite aware of which policies are implemented (Naurin and Oscarsson 2017; Pétry and Duval 2017; Thomson and Brandenburg 2019); and that partisan bias impacts overall evaluations of government performance, but not necessarily the effect of policy performance on these evaluations (e.g., Naurin et al. 2019b). It is up to future research to determine whether partisanship and voter awareness impact the consideration of economic outcomes and policy output by voters in different ways. Similarly, it is up to future studies to determine whether the found effects hold up in more realistic settings—using non-fictive scenarios, more concrete information, additional attributes, or perhaps real-world performance evaluations or vote decisions. While it is important to acknowledge the limited external validity of this highly fictive experiment, the results found in this study speak to an important part of voter psychology regarding preferences in government performance, that should travel to other contexts. For now, the findings of this study warrant the conclusion that voters care which policies their government implements, even beyond outcomes, and are therewith more policy-seeking than commonly accounted for in the retrospective voting literature.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

The design of which was pre-registered with EGAP under Registration Number 20190603AA.

Arguably even more important than commonly presumed (Becher and Donnelly 2013).

Which can be seen as a partial rebuttal of the conclusion of Achen and Bartels (2016) that voters blame governments for ‘irrelevant’ events such as shark attacks. The prevailing opinion is that it is not the events itself that are considered, but rather the government’s preparation and response (see Healy and Malhotra 2013). However, Healy et al. (2010) found that truly irrelevant events such as sports scores impact voters’ evaluations of government performance as well.

The design of which was pre-registered with EGAP under Registration Number 20190603AA.

For more information, see https://lore.gu.se.

With five attributes and three values per attribute 243 different party profiles can be generated – for 29,403 possible choice tasks. As shown by Hainmueller et al. (2014), it is not necessary to test all these possible combinations of profiles, as long as the attribute values are randomly assigned – which they are here.

Comparable to the measures used in other studies on voters’ evaluations of government performance (e.g., Naurin et al. 2019b).

Running the same analysis with binary logistic regression (logit) produced similar results. The same applies to analyses where the unit of analysis was set to party profile, rather than choice task, and where dummy variables were used instead of continuous variables. The results of these analyses are presented in the supplementary material (pp. 7–10).

For example, if one respondent received a choice task in which party B was assigned a positive value for pledge performance (‘most were fulfilled’; 1), and party A a negative value (‘most were not fulfilled’; − 1), the resulting value for that respondent’s choice task would be ‘Party B + 2′ for pledge performance. Differences between positive (1) and neutral (0) values; and between neutral (0) and negative (− 1) values were assigned + 1. The reference categories are the choice tasks in which party A and party B received the same values —both neutral, both positive, or both negative—for the same attribute, and the resulting value is thus 0. In the supplementary material (p. 11) a comparison is presented of the effects for different compilations of these categories.

In essence the mirror image of the popular notion in studies on economic voting that voters are sociotropic in economic evaluations because they believe economic gains for society will eventually benefit their personal finances (e.g., Kiewiet and Lewis-Beck 2011). In terms of policy output, voters may be egotropic because they believe implementation of their views will ultimately benefit society.

References

Abramson, S., Koçak, K. and Magazinnik, A. (2019). What do we learn about voter preferences from conjoint experiments? Working Paper. https://scholar.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/kkocak/files/conjoint_draft.pdf

Achen CH, Bartels LM (2016) Democracy for realists: why elections do not produce responsive government. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Anderson CJ (2007) The end of economic voting? Contingency dilemmas and the limits of democratic accountability. Annu Rev Polit Sci 10:271–296

Arel-Bundock V, Blais A, Dassonneville R (2019) Do voters benchmark economic performance? Br J Polit Sci. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000236

Ashworth S (2012) Electoral accountability: recent theoretical and empirical work. Annu Rev Polit Sci 15:183–201

Atkeson LR, Partin RW (1995) Economic and referendum voting: a comparison of gubernatorial and senatorial elections. Am Polit Sci Rev 89(1):99–107

Aytaç SE (2018) Relative economic performance and the incumbent vote: a reference point theory. J Polit 80(1):16–29

Bansak K, Hainmueller J, Hopkins DJ, Yamamoto T (2020) Using conjoint experiments to analyze elections: the essential role of the average marginal component effect (AMCE). SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3588941

Becher M, Donnelly M (2013) economic performance, individual evaluations, and the vote: investigating the causal mechanism. J Polit 75(4):968–979

Bechtel MM, Hainmueller J (2011) How lasting is voter gratitude? An analysis of the short- and long-term electoral returns to beneficial policy. Am J Polit Sci 55(4):852–868. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00533.x

Bélanger É, Lewis-Beck MS (2004) National economic voting in France: objective versus subjective measures. In: Lewis-Beck MS (ed) The French voter: before and after the 2002 elections. Basingstoke, Palgrave McMillan

Bengtsson Å, Wass H (2010) Styles of political representation: what do voters expect? J Elect Public Opin Parties 20(1):55–81

Born A, Van Eck P, Johannesson M (2018) An experimental investigation of election promises. Polit Psychol 39(3):685–705

Boyne GA, James O, John P, Petrovsky N (2009) Democracy and government performance: holding Incumbents accountable in English local governments. J Polit 71(4):1273–1284

Burlacu D, Immergut EM, Oskarson M, Rönnerstrand B (2018) The politics of credit claiming: rights and recognition in health policy feedback. Soc Policy Admin 52(4):880–894

Canes-Wrone B (2015) From mass preferences to policy. Annu Rev Polit Sci 18:147–165

Carman CJ (2007) Assessing preferences for political representation in the US. J Elect Public Opin Parties 17(1):1–19

Carsey TM, Wright GC (1998) State and national factors in gubernatorial and senatorial elections. Am J Polit Sci 42(3):994–1002

Carsey TM, Layman GC (2006) Changing sides or changing minds? Party identification and policy preferences in the American electorate. Am J Polit Sci 50(2):464–477

Corazzini L, Kube S, Maréchal MA, Nicolò A (2014) Elections and deceptions: an experimental study on the behavioral effects of democracy. Am J Polit Sci 58(3):579–592

Dahl RA (1991) Democracy and its critics. Yale University Press, New Haven

De Vries CE, Edwards EE, Tillman ER (2011) Clarity of responsibility beyond the pocketbook: how political institutions condition EU issue voting. Comp Polit Stud 44(3):339–363

De Vries CE, Giger N (2014) Holding governments accountable? Individual heterogeneity in performance voting. Eur J Polit Res 53(2):345–362

Downs A (1957) An economic theory of democracy. Harper, New York

Dupont JC, Bytzek E, Steffens MC, Schneider FM (2019) Which kind of political campaign messages do people perceive as election pledges? Electoral Stud 57:121–130

Duval D (2019) Ringing the alarm: the media coverage of the fulfillment of electoral pledges. Electoral Stud 60:102041

Elinder M, Jordahl H, Poutvaara P (2015) Promises, policies and pocketbook voting. Eur Econom Rev 75:177–194

Esaiasson P, Giljam M, Persson M (2016) Responsiveness beyond policy satisfaction: does it matter to citizens? Comp Polit Stud 50(6):739–765

Fair RC (1978) The effect of economic events on votes for president. Rev Econom Stat 60(2):159–173

Fearon J (1999) Electoral accountability and the control of politicians. In: Przeworski A, Stokes SC, Manin B (eds) Democracy, accountability, and representation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Ferejohn JA (1986) Incumbent performance and electoral control. Public Choice 50:05–25

Fiorina MP (1981) Retrospective voting in American national elections. Yale University Press, New Haven

Fournier P, Blais A, Nadeau R, Gidengil E, Nevitte N (2003) Issue importance and performance voting. Polit Behav 25(1):51–67

Fisher SD, Hobolt S (2010) Coalition government and electoral accountability. Electoral Stud 29(3):358–369

Fox J, Shotts KW (2009) Delegates or trustees? A theory of political accountability. J Polit 71(4):1225–1237

Franchino F, Zucchini F (2015) Voting in a multi-dimensional space: a conjoint analysis employing valence and ideology attributes of candidates. Polit Sci Res Methods 3(2):221–241

Gasper JT, Reeves A (2011) Make it rain? Retrospection and the attentive electorate in the context of natural disasters. Am J Polit Sci 55(2):340–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00503.x

Gidengil E, Karakoç E (2016) Which matters more in the electoral success of Islamist (successor) parties—Religion or performance? The Turkish case. Party Polit 22(3):325–338

Giger N, Nelson M (2011) The electoral consequences of welfare state retrenchment: blame avoidance or credit claiming in the era of permanent austerity? Eur J Polit Res 50(1):1–23

Giuliani M, Massari SA (2019) The economic vote at the party level: electoral behaviour during the Great Recession. Party Polit 25(3):461–473

González-Sirois G, Bélanger É (2019) Economic voting in provincial elections: revisiting electoral accountability in the Canadian provinces. Region Federal Stud 29(3):307–327

Grossback LJ, Peterson DAM, Stimson JA (2005) Comparing competing theories on the causes of mandate perceptions. Am J Polit Sci 49(2):406–419

Hainmueller J, Hopkins DJ, Yamamoto T (2014) Causal inference in conjoint analysis: understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Polit Anal 22(1):1–30

Hansen KM, Olsen AL, Bech M (2015) Cross-national yardstick comparisons: a choice experiment on a forgotten voter heuristic. Polit Behav 37(4):767–789

Healy AJ, Malhotra N, Hyunjung Mo C (2010) Irrelevant events affect voters’ evaluations of government performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107(29):12804–12809

Healy AJ, Malhotra N (2009) Myopic voters and natural disaster policy. Am Polit Sci Rev 103(3):387–406. https://doi.org/10.1117/S0003055409990104

Healy AJ, Malhotra N (2013) Retrospective voting reconsidered. Annu Rev Polit Sci 16:285–306

Healy AJ, Persson M, Snowberg E (2017) Digging into the pocketbook: evidence on economic voting from income registry data matched to a voter survey. Am Polit Sci Rev 111(4):771–785

Hellwig T (2008) Globalization, policy constraints, and vote choice. J Polit 70(4):1128–1141

Hellwig T, Marinova DM (2015) More misinformed than myopic: economic retrospections and the voter’s time horizon. Polit Behav 37(4):865–887

Hogan RE (2008) Policy Responsiveness and incumbent reelection in state legislatures. Am J Polit Sci 52(4):858–873

Holmes JS, Gutiérrez de Piñeres SA (2013) Security and economic voting: support for incumbent parties in Colombian presidential elections. Democratization 20(6):1117–1143

Hopkins DJ, Pettingill LM (2018) Retrospective voting in big-city US mayoral elections. Polit Sci Res Methods 6(4):697–714

Jankowski R (2018) Are voters myopic? An empirical analysis. Soc Anthropol 6(4):375–385

Kassow BJ, Finocchiaro CJ (2011) Responsiveness and electoral accountability in the U.S. senate. Am Polit Res 39(6):1019–1044

Kayser MA, Peress M (2012) Benchmarking across borders: electoral accountability and the necessity of comparison. Am Polit Sci Rev 106(3):661–684

Key VO, Cummings MC (1966) The responsible electorate. Belknap Press of Harvard University, Harvard

Kiewiet DR, Lewis-Beck MS (2011) No man is an island: self-interest, the public interest, and sociotropic voting. Crit Rev 23(3):303–319

Klingemann H-D, Hofferbert RI, Budge I (1994) Parties, policies and democracy. Westview Press, Boulder

Knudsen E, Johannesson MP (2019) Beyond the limits of survey experiments: how conjoint designs advance causal inference in political communication research. Polit Commun 36(2):259–271

Kostadinova P (2017) Party pledges in the news: which election promises do the media report? Party Polit 23(6):636–645

Kramer GH (1971) Short-term fluctuations in U.S. voting behavior. Am Polit Sci Rev 65(1):131–143

Lachat R (2011) Electoral competitiveness and issue voting. Polit Behav 33(4):645–663

Lewis-Beck MS, Stegmaier M (2000) Economic determinants of electoral outcomes. Annu Rev Polit Sci 3:183–219

Matthieβ T (2020) Retrospective pledge voting: a comparative study of the electoral consequences of government parties’ pledge fulfilment. Eur J Polit Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12377

McDonald MD, Budge I (2005) Elections, parties, democracy: conferring the median mandate. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Naurin E (2011) Election promises, party behaviour and voter perceptions. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Naurin E, Oscarsson H (2017) When and why are voters correct in their evaluations of specific government performance? Polit Stud 65(4):860–876

Naurin E, Royed TJ, Thomson R (2019) Party mandates and democracy: making, breaking, and keeping election pledges in twelve countries. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Naurin E, Soroka SN, Markwat N (2019) Asymmetric accountability: an experimental investigation of biases in evaluations of governments’ election pledges. Comp Polit Stud 52(13–14):2207–2234

Page BI, Jones CC (1979) Reciprocal effects of policy preferences, party loyalties and the vote. Am Polit Sci Rev 73(4):1071–1081

Pétry F, Duval D (2017) When heuristics go bad: citizens’ misevaluations of campaign pledge fulfilment. Electoral Stud 50:116–127

Pitkin HF (1967) The concept of representation. University of California Press, Berkeley

Ragusa JM, Tarpey M (2016) The geographies of economic voting in presidential and congressional elections. Polit Sci Q 131(1):101–132

Singer MM (2011) Who says “it’s the economy”? Cross-national and cross-individual variation in the salience of economic performance. Comp Polit Stud 44(3):284–312

Stevenson RT, Duch R (2013) The meaning and use of subjective perceptions in studies of economic voting. Electoral Stud 32(2):305–320

Stokes SC (2001) Mandates and democracy: neoliberalism by surprise in Latin America. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Stubager R, Botterrill NW, Lewis-Beck MS, Nadeau R (2014) Scope conditions of economic voting: the Danish exception? Electoral Stud 34:16–26

Thomson R, Brandenburg H (2019) Trust and citizens’ evaluations of promise keeping by governing parties. Political Stud 67(1):249–266

Thorlakson L (2016) Electoral linkages in federal systems: barometer voting and economic voting in the German Länder. Swiss Polit Sci Rev 22(4):608–624

Tilley J, Hobolt SB (2011) Is the government to blame? An experimental test of how partisanship shapes perceptions of performance and responsibility. J Polit 73(2):316–330

Van der Eijk C, Franklin M, Demant F, Van der Brug W (2007) The endogenous economy: ‘real’ economic conditions, subjective economic evaluations and government support. Acta Polit 42(1):1–22

Weldon S, McNeney D (2019) Issue voting: modern and classic accounts. In: The Oxford research encyclopedia of politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.776

Werner A (2019) Voters’ preferences for party representation: promise-keeping, responsiveness to public opinion or enacting the common good. Int Polit Sci Rev 40(4):486–501

Wlezien C (2015) The myopic voter? The economy and US presidential elections. Electoral Stud 39:195–204

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to LORE for providing the infrastructure for implementing the experiment, and in particular to Elina Lindgren for her crucial help in designing the experiment. Many thanks are also due to Elin Naurin, Maria Oskarson, Mike Tomz, and Peter Esaiasson for their invaluable input during various stages of this project. Finally, the author wishes to express his gratitude to the department of Political Science, and the SOM Institute for making this research possible.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Markwat, N. The policy-seeking voter: evaluations of government performance beyond the economy. SN Soc Sci 1, 26 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-020-00030-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-020-00030-4