Abstract

Do economic perceptions influence partisan preferences or vice versa? We argue that the direction of influence between government approval and economic perceptions is conditional on the state of the economy. Under conditions of economic crisis, when economic signals are relatively unambiguous, perceptions of the economy can be expected to exogenously influence government approval but this is not found when the economy is experiencing a more typical pattern of moderate growth and economic signals are more mixed. We test these arguments using British election panel surveys covering electoral cycles of moderate economic growth (1997–2001) and dramatic and negative disruption (2005–2010). We examine the most commonly employed measures of retrospective economic perceptions and estimate a range of models using structural equations modelling. We demonstrate that when the economy is performing extremely badly economic perceptions have an exogenous effect on government approval and provide a means of electoral accountability, but this is not the case in under more normal circumstances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These concerns apply primarily to the use of perceptions rather than objective measures of economic performance. The latter have far stronger claim to exogenous status and can address concerns about endogeneity by examining how economic performance (measured with non-survey based metrics, such as unemployment or GDP growth) and incumbent vote share are related over time. Usually, however, these objective measures have an unmeasured ‘black box’ with respect to voters’ assessments and motivations.

The BEPS 1997–2001 is accessible through the UK Data Archive; the BEPS 2005–2010 can be downloaded from the British Election Study at the University of Essex (http://bes2009-10.org/).

The initial wave contains 7,793 respondents, with 3,402 participating in the 2010 pre-campaign survey.

In both panels, respondents tend to go in and out of the survey rather than leave permanently. Only 13 and 4 % of respondents in the 1997–2001 and 2005–2010 panels, respectively, dropped out after the first wave.

In both panels, respondents who participated in all of the studied waves may have experienced different changes in their party approval and economic perceptions than those who left the panel. There is also some evidence of differential attrition by education and age across the two panels. Therefore, all of the SEM’s were re-estimated on the samples constructed with multiple imputation (Tables 4B and 5B in the Online Appendix). Multiple imputation was performed using ‘Amelia II’ (Honaker et al. 2012), package in R. The estimates are very similar, although model fit is somewhat worse due to larger numbers of cases.

The proportion of “don’t know” responses has declined noticeably after the economic crisis: it went from around 7 % in wave 1 (2005) and wave 4 (2006) to around 2 % in wave 5 (2008) and wave 6 (2009), to under 1 % in wave 7 (2010).

We replicated the analysis with the strength of Labour party identification (coded as 0 “not Labour” 1”not very strongly” 2”fairly strongly” 3”very strongly”). In the earlier panel, the strength of Labour party identification and economic perceptions do not have significant contemporaneous reciprocal effects, while in the later panel, the strength of Labour party identification has a small positive effect on economic perceptions, significant at p < 0.05, with no reciprocal effect of economic perceptions (results available on request). .

The variable is recoded as follows: 0 = 1, 1/3 = 2, 4/6 = 3, 7/9 = 4, 10 = 5. Although this results in a loss of information, we re-estimate the models with the original 11-point measure and the findings are similar (Table 1B in the online appendix). We also replicate the results using alternative recoding, such as 0/1 = 1, 2/3 = 2, 4/6 = 3, 7/9 = 4, 10 = 5, but the estimates are similar (full results available on request).

The unconditional expected values of all error terms are zero because the main model includes an intercept.

Aggregate data is calculated using the responses to the British Election Studies in all years except those in which the questions were not asked: 2003, 2004 and 2007 (and 1998 for economic evaluations only). Economic evaluations in these years are based on responses to the retrospective economic evaluations question asked by GfK NOP. The question is nearly identical to that asked in the BES: How do you think the general economic situation in this country has changed over the last 12 months? (Got a lot better, Got a little better, Stayed the same, Got a little worse, Got a lot worse). Labour government approval for 2003, 2004 and 2007 is based on YouGov’s approval question: Do you approve or disapprove of the Government’s record to date? (Approve, Disapprove, don't know). The BES responses were recoded to match this approve/disapprove dichotomy, before being aggregated.

Demographic and socio-economic controls such as gender, age, education and occupation were not statistically significant and did not affect the coefficients of the variables of interest, so they were excluded from the final models. Furthermore, to the extent that they are time-invariant in such a short panel, their effects will be differenced out in the ensuing SEM estimation.

All SEM models are estimated in R using the SEM package (Fox 2006). The models were also replicated in AMOS and Stata 12, with nearly identical results.

While first-differenced variables are normally distributed, non-differenced variables show deviations from the normal distribution. As asymptotic standard errors may be incorrect, we bootstrap standard errors with 800 replications. As the variables of interest are on a 1-5 scale, they could be treated as ordinal rather than continuous. We re-estimated all the SEM’s with polychoric correlations and bootstrapped standard errors (Tables 2B and 3B in the online appendix). Although the results are very similar, the model fit is considerably worse.

Since there were two shorter surveys between wave 8 (2001 after the general election) and wave 5 (spring 1999), wave 5 is technically a t-4 lag, but feelings about the Labour party were not measured in the intervening waves.

To check if traditional Labour voters were disproportionately negatively affected by the economy at the end of the 1997–2001 electoral cycle, which would perhaps account for the lack of the effect of economic perceptions on Labour approval, changes in economic perceptions between 2001 and 2000 are tabulated by occupation (see Table 6B in the online Appendix). However, traditional labour voters (e.g. foremen and technicians; manual workers) were more likely to experience positive changes in their self-reported economic perceptions between 2000 and 2001 than most other occupational groups.

Estimating the models separately by demographics does not alter the finding that economic perceptions have an exogenous effect on Labour approval in the later electoral cycle only. In the 1997–2001 panel, the significant positive effect of Labour approval on economic perceptions, with no corresponding effect of economic perceptions on Labour approval, holds for both the higher and lower educated respondents. In the 2005–2010 panel, the direction and strength of the coefficients are similar among those with degree-level education, below-degree education, and the full sample. Similarly, the estimates are robust to sub-setting the samples by age group (full results available on request). This suggests that it is unlikely that our instruments are correlated with time-varying predictors of economic perceptions and Labour approval such as newspaper readership, for example, which tend to vary across demographic subsets.

The results are similar when the model is re-estimated with the 2010 campaign wave, rather than the pre-campaign wave, as t0 and the 2009 wave as t-1. In contrast, an otherwise identical model with the 2009 wave as t0, 2008 as t-1 and 2006 as t-2 produces positive but statistically insignificant reciprocal effects for both Labour approval and economic perceptions. Given a two-year gap between 2008 and 2006, it is not surprising that the effects are negligible.

The observation of a sub-group within the electorate who do not update their party affiliation in response to perceptions of changing conditions fits well with the established literature on the effects of stable identities that are to some degree immune to updating in response to changing evaluations (Bartels 2002; Green et al. 2002). It is also fits with the findings of an analysis of performance voting amongst respondents with varying levels of political interest using the 2005–2010 BES panel. This study finds that amongst less politically interested respondents updating simply does not occur as a result of changes in current evaluations across a range of performance indicators (Evans and Chzhen 2013).

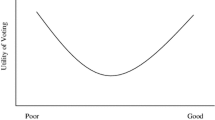

We have replicated the analysis using data from the BEPS 1992–1997, covering the electoral cycle when the Conservative party was in power. The estimated effect of economic perceptions on the Conservative party approval (0.056, p = 0.06) is somewhere between the effect of economic perceptions on Labour party approval estimated in the 1997–2001 panel (0.029, p = 0.207) and the one in the 2005–2010 panel (0.095, p = 0.001). The effect of Conservative approval on economic perceptions is not statistically significant (see Table 8B in the online appendix). This is consistent with the observation that the proportion of the voting age population citing the economy as one of the top two most important issues facing the country in 1996–1997 was higher than in 2001–2000, but lower than in 2010–2009 (Fig. 1). We also replicated the 2005–2010 analysis using issue competence questions, in place of economic evaluations. We find that evaluations of the government’s economic competence, measured on a five-point (1–5) scale, have a significant positive effect on Labour approval, but the reciprocal effect of Labour approval on economic competence is not statistically significant—see online appendix, Table 10B and 11B. This is entirely consistent with our findings for economic perceptions and Labour approval, suggesting that a similar causal mechanism is at work. Moreover, this finding does not hold for non-economic issues. While Labour approval has a significant positive effect on competence in handling the NHS, the reciprocal effect is not statistically significant, suggesting that the NHS handling competence is endogenous to feelings about the governing party even when the economy is performing badly.

References

Abramowitz, A. I., Lanoue, D. J., & Ramesh, S. (1988). Economic conditions, causal attributions, and political evaluations in the 1984 Presidential Election. Journal of Politics, 50(4), 848–863.

Anderson, C. J. (2007). The end of economic voting? Contingency dilemmas and the limits of democratic accountability. Annual Review of Political Science, 10, 271–296.

Anderson, T. W., & Hsiao, C. (1981). Estimation of dynamic models with error components. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 76, 598–606.

Anderson, T. W., & Hsiao, C. (1982). Formulation and estimation of dynamic models using panel data. Journal of Econometrics, 18, 47–82.

Anderson, C. J., Mendes, S. M., Tverdova, Y. V., & Kim, H. (2004). Endogenous economic voting: Evidence from the 1997 British Election. Electoral Studies, 23(4), 683–708.

Bartels, L. M. (2002). Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Political Behavior, 24(1), 117–150.

Bartle, J., & Laycock, S. (2012). Telling more than they can know? Does the most important issue really reveal what is most important to voters? Electoral Studies, 31, 679–688.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370.

Berelson, B., Lazarsfeld, P. F., & McPhee, W. N. (1954). Voting: A study of opinion formation in a presidential campaign. Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press.

Bloom, H. S., & Price, H. D. (1975). Voter response to short-run economic conditions: The asymmetric effect of prosperity and recession. American Political Science Review, 69(4), 1240–1254.

Campbell, A., Converse, P., Miller, W., & Stokes, D. (1960). The american voter. New York: Wiley.

De Boef, S., & Kellstedt, P. M. (2004). The political (and economic) origins of consumer confidence. American Journal of Political Science, 48(4), 633–649.

Duch, R. M., Palmer, H. D., & Anderson, C. J. (2000). Heterogeneity in perceptions of national economic conditions. American Journal of Political Science, 44(4), 635–652.

Erikson, R. S., MacKuen, M. B., & Stimson, J. A. (2002). The macro polity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Evans, G., & Andersen, R. (2006). The political conditioning of economic perceptions. Journal of Politics, 68(1), 194–207.

Evans, G., & Chzhen, K. (2013). Re-evaluating the valence model of political choice. Political Science: Research & Methods, 1(2).

Evans, G., & Pickup, M. (2010). Reversing the Causal Arrow: The political conditioning of economic perceptions in the 2000–2004 US Presidential election cycle. Journal of Politics, 72(4), 1236–1251.

Fiorina, M. (1981). Retrospective voting in American National Elections. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Fox, J. (2006). Structural equation modeling with the SEM package in R. Structural Equation Modeling, 13(3), 465–486.

Freeman, J., Houser, D., Kellstedt, P., & Williams, J. T. (1998). Long memoried processes, unit roots, and causal inference in political science. American Journal of Political Science, 42(4), 1289–1327.

Gerber, A. S., & Green, D. (1999). Misperceptions about perceptual bias. Annual Review of Political Science, 2, 189–210.

Gerber, A. S., & Huber, G. A. (2010). Partisanship, political control, and economic assessments. American Journal of Political Science, 54(1), 153–173.

Green, D., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan hearts and minds. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hetherington, M. J. (1996). The media’s role in forming voters’ national economic evaluations in 1992. American Journal of Political Science, 40(2), 372–395.

Honaker, J., King, G., & Blackwell, M. (2012). Amelia II: A Program for Missing Data. http://r.iq.harvard.edu/docs/amelia/amelia.pdf. Accessed 10 April 2011.

Jennings, W., & Wlezien, C. (2011). Distinguishing between most important problems and issues? Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(3), 545–555.

Johnston, R., Sarker, R., Jones, K., Bolster, A., Propper, C., & Burgess, S. (2005). Egocentric economic voting and changes in party choice: Great Britain, 1992–2001. Journal of Elections, Political Opinion and Parties, 1, 129–144.

Kinder, D. R., Adams, G. S., & Gronke, P. W. (1989). Economics and politics in the 1984 American Presidential Election. American Journal of Political Science, 33(2), 491–515.

Kinder, D. R., & Kiewiet, D. R. (1981). Sociotropic politics: The American Case. British Journal of Political Science, 11(1), 129–161.

Ladner, M., & Wlezien, C. (2007). Partisan preferences, electoral prospects, and economic expectations. Comparative Political Studies, 40, 571–596.

Lewis-Beck, M., Nadeau, S. R., & Elias, A. (2008). Economics, party, and the vote: Causality issues and panel data. American Journal of Political Science, 52(1), 84–95.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Stegmaier, M. (2007). Economic models of the vote. In R. Dalton & H.-D. Klingemann (Eds.), The oxford handbook of political behavior (pp. 518–537). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marsh, M., & Tilley, J. (2010). The attribution of credit and blame to governments and its impact on vote choice. British Journal of Political Science, 40(1), 115–134.

Mutz, D. C. (1998). Impersonal influence: How perceptions of mass collectives affect political attitudes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nannestad, P., & Paldam, M. (1997). The grievance asymmetry revisited: A micro study of economic voting in Denmark, 1986–1992. European Journal of Political Economy, 13(1), 81–99.

Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica, 49, 1417–1426.

Parker-Stephen, E. (2013). Tides of disagreement: How reality facilitates (and inhibits) Partisan Public Opinion. Department of Political Science, Stony Brook University (Unpublished Ms).

Peffley, M. (1984). The voter as juror: Attributing responsibility for economic problems. Political Behavior, 6(3), 275–294.

Rozin, P., & Royzman, E. B. (2001). Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(4), 296–320.

Rudolph, T. J. (2003). Who’s responsible for the economy? The formation and consequences of responsibility attributions. American Journal of Political Science, 47(4), 698–713.

Rudolph, T. J. (2006). Triangulating political responsibility: The motivated formation of responsibility judgments. Political Psychology, 27(1), 99–122.

Sanders, D. (2000). The real economy and the perceived economy in popularity functions: How much do voters need to know? A study of British data, 1974–97. Electoral Studies, 19(2–3), 275–294.

Sanders, D., Clarke, H. D., Stewart, M. C., & Whiteley, P. (2011). Downs, stokes and the dynamics of electoral choice. British Journal of Political Science, 41, 287–314.

Sanders, D., Clarke, H. D., Stuart, M. C., & Whiteley, P. (2007). Does mode matter for modeling political choice? Evidence from the 2005 British Election Study. Political Analysis, 15, 257–285.

Sanders, D., & Gavin, N. T. (2004). Television news, economic perceptions and political preferences in Britain, 1997–2001. Journal of Politics, 66, 1245–1266.

Soroka, S. N. (2006). Good news and bad news: Asymmetric responses to economic information. The Journal of Politics, 68(2), 372–385.

Taylor, S. E. (1991). Asymmetrical effects of positive and negative events: The mobilization minimization hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 67–85.

Tilley, J., & Hobolt, S. B. (2011). Is the government to blame? An experimental test of how partisanship shapes perceptions of performance and responsibility. Journal of Politics, 73(2), 1–15.

van der Eijk, C., Franklin, M. N., Demant, F., & van der Brug, W. (2007). The endogenous economy: ‘Real’ economic conditions, subjective economic evaluations and government support. Acta Politica, 42(1), 1–22.

Wilcox, N. T., & Wlezien, C. (1993). The contamination of responses to survey items: Economic perceptions and political judgments. Political Analysis, 5(1), 181–213.

Wlezien, C., Franklin, M., & Twiggs, D. (1997). Economic perceptions and vote choice: Disentangling the endogeneity. Political Behavior, 19(1), 7–17.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2006). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach (3rd ed.). Mason, OH: Thompson South-Western.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross-sectional and panel data (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chzhen, K., Evans, G. & Pickup, M. When do Economic Perceptions Matter for Party Approval?. Polit Behav 36, 291–313 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9236-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9236-2