Abstract

Background and aims

The establishment of Rhizophoracean mangroves usually involves a transition from a horizontal to vertical orientation. Neither how this occurs nor the possible associated ecological benefits and costs have previously been considered.

Methods

The “righting” of red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle L.) propagules was studied using frequent observation and time lapse photography under growth chamber and greenhouse conditions. Rates of leaf appearance were analyzed as functions of substrate, propagule placement, propagule orientation and salinity.

Results

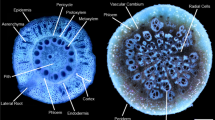

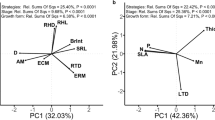

Propagule righting progressed in four phases. First, propagules alternately elevated and relaxed in a diurnal cycle. Next, propagules developed upward curvature, centered approximately two-thirds of the way between the base and tip; curvature developed and relaxed in 24 h cycles. Third, the distal portion straightened and a second center of curvature developed at the base, elevating the whole propagule. Finally, the epicotyl swelled, the stem elongated and leaves unfolded. If bases were in contact with the substrate, initial orientation had no effect on leaf opening. However, propagules without that contact experienced delays throughout the cycle. The delays were longer, initially, at higher salinity.

Conclusions

R. mangle propagules are both physiologically and phenotypically highly flexible. This improves their chances of successful establishment in a heterogeneous, unpredictable, and often, high energy environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ball MC (1988) Ecophysiology of mangroves. Trees 2:129–142

Ball MC (2002) Interactive effects of salinity and irradiance on growth: implications for mangrove forest structure along salinity gradients. Trees 16:126–139

Dassanayake M, Haas JS, Bohnert HJ, Cheeseman JM (2010) Comparative transcriptomics for mangrove species: an expanding resource. Funct Integ Genom 10:523–532

Davis JH (1940) The ecology and geologic role of mangroves in Florida. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, p 384, with 312 plates

Drexler JZ (2001) Maximum longevities of Rhizophora apiculata and R. mucronata propagules. Pac Sci 55:17–22

Ellison AM, Farnsworth EJ (1993) Seedling survivorship, growth and response to disturbance in a Belizean mangal. Amer J Bot 80:1137–1145

Ellison AM, Farnsworth EJ (1996) Spatial and temporal variability in growth of Rhizophora mangle sapling on coral cays: links with variation in insolation, herbivory, and local sedimentation rate. J Ecol 84:717–731

Farnsworth EJ, Ellison AM (1996) Sun-shade adaptability of the red mangrove, Rhizophora mangle (Rhizophoraceae): changes through ontogeny at several leves of biological organization. Amer J Bot 83:1131–1143

Feller IC (1995) Effects of nutrient enrichment on growth and herbivory of dwarf red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle). Ecol Monogr 65:477–505

Feller IC (2002) The role of herbivory by wood-boring insects in mangrove ecosystems in Belize. Oikos 97:167–176

Feller IC, Whigham D, O’Neill J, McKee K (1999) Effects of nutrient enrichment on within-stand cycling in a mangrove forest. Ecol 80:2193–2205

Gallego-Bartolome J, Kami C, Fankhauser C, Alabadi D, Blazquez MA (2011) A hormonal regulatory module that provides flexibility to tropic responses. Plant Physiol 156:1819–1825

Hart JW, Macdonald IR (1981) Phototropism and geotropism in hypocotyls of cress (Lepidium sativum L.). Plant Cell Environ 4:197–201

Janzen D (2007) Mangroves: where’s the understory? J Trop Ecol 1:89–92

Juncosa AM (1982) Developmental morphology of the embryo and seedling of Rhizophora mangle L. (Rhizophoraceae). Amer J Bot 69:1599–1611

Juncosa A, Tomlinson P (1988) Systematic comparison and some biological characteristics of Rhizophoraceae and Anisophylleaceae. Ann Mo Bot Gard 75:1296–1318

Kitaya Y, Sumiyoshi M, Kawabata Y, Monji N (2002) Effect of submergence and shading of hypocotyls on leaf conductance in young seedlings of the mangrove Rhizophora stylosa. Trees 16:147–149

Krauss KW, Allen JA (2003) Influences of salinity and shade on seedling photosynthesis and growth of two mangrove species, Rhizophora mangle and Bruguiera sexangula, introduced to Hawaii. Aquat Bot 77:311–324

Krauss K, Lovelock C, McKee K, López-Hoffman L, Ewe S, Sousa W (2008) Environmental drivers in mangrove establishment and early development: a review. Aquat Bot 89:105–127

Lovelock CE, Feller IC, Ball MC, Engelbrecht BMJ, Ewe ML (2006) Differences in plant function in phosphorus- and nitrogen-limited mangrove ecosystems. New Phytol 172:514–522

Lugo A (1986) Mangrove understory: an expensive luxury. J Trop Ecol 2:287–288

Lugo A, Snedaker SC (1974) The ecology of mangroves. Ann Rev Ecol Syst 5:39–64

Macdonald IR, Hart JW, Gordon DC (1983) Analysis of growth during geotropic curvature in seedling hypocotyls. Plant Cell Environ 6:401–406

Parida AK, Das AB (2004) Effects of NaCl stress on nitrogen and phosphorous metabolism in a true mangrove bruguiera parviflora grown under hydroponic culture. J Plant Physiol 161:921–928

Parida AK, Jha B (2010) Salt tolerance mechanisms in mangroves: a review. Trees 24:199–217

Rabinowitz D (1978a) Dispersal properties of mangrove propagules. Biotropica 10:47–57

Rabinowitz D (1978b) Early growth of mangrove seedlings in Panama and an hypothesis concerning the relationship of dispersal and zonation. J Biogeog 5:113–133

Rabinowitz D (1978c) Mortality and initial propagule size in mangrove seedlings in Panama. J Ecol 66:45–51

Smith SM, Snedaker SC (2000) Hypocotyl function in seedling development of the red mangrove, Rhizophora mangle L. Biotropica 32:677–685

Sousa WP, Mitchell BJ (1999) The effect of seed predators on plant distributions: is there a general pattern in mangroves? Oikos 86:55–66

Sousa WP, Quek SP, Mitchell BJ (2003) Regeneration of Rhizophora mangle in a Caribbean mangrove forest: interacting effects of canopy disturbance and a stem-boring beetle. Oecologia 137:436–445

Sousa W, Kennedy P, Mitchell B, Ordóñez LB (2007) Supply-side ecology in mangroves: do propagule dispersal and seedling establishment explain forest structure? Ecol Monographs 77:53–76

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Amos Gazit at the Caribbean Research and Management of Biodiversity Institute (CARMABI) in Curaçao, Klaus Rützler. Candy Feller, and the Smithsonian Caribbean Coral Reef Ecosystem (CCRE) project for access to facilities at Carrie Bow Caye and Twin Cays, Belize, and Rhanor Gillette and Bette Chapman for assistance in the field and with photography. This is contribution number 917 from the CCRE program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Timothy J. Flowers.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

“push-ups” (6.3 MB)—During the first phase of sprouting, propagules elevate and relax in a diurnal fashion, up during the day and down at night. The movements likely result from alternating hydration and partial desiccation of the propagule, made possible by soil contact at the base. The end of this phase coincides with the penetration of the soil by the adventitious roots. (M4V 6408 kb)

Play this movie a couple of times. After watching the propagule at the front, watch the dead one (same orientation, second box).

diageotropic curvature (4.7 MB)—During the second phase of sprouting, push-ups are replaced by increasing hypocotyl curvature which does not completely relax at night. The dead propagule does not enter this phase. (M4V 4792 kb)

Note that restrained propagules (the third from the front) nonetheless curve. The epicotyl-less propagule toward the rear lifts (delayed push-up phase?) but does not curve.

basal curvature and elevation (3.5 MB)—During the third phase of sprouting, a second center of curvature develops at the base of the propagules, just above the point where roots anchor them. This elevates the whole unit distal to the base. (M4V 3588 kb)

Restrained propagules (the third from the front) continue to curve. No lifting of the base is visible yet, however. The epicotyl-less propagule toward the rear lifts higher, but with minimal curvature.

autotropic straightening (and leaf emeergence) (6.3 MB)—During the last phase of sprouting, the elevated propagule straightens as it becomes vertical. This is accomplished by elongation of the inner radius of curvature. At this point, too, the epicotyl bud swells and the shoot emerges… this is NOT developmentally linked to the elevation itself (see main text). (M4V 6444 kb)

At this point, the epicotyl-less propagule has developed an adventitious bud. In general, mangroves do not retain the capacity for that for very long. The restrained propagules also develop leaves and begin to pull their bases from the soil (it is a bit hard to see).

composite of all four phases (9.4 MB)—This movie combines all four phases into a single, summarizing movie. (M4V 9599 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheeseman, J.M. How red mangrove seedlings stand up. Plant Soil 355, 395–406 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-011-1115-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-011-1115-1