Abstract

One of the most important sections of nonlinear wave theory is related to the collisions of single pulses. These often exhibit corpuscular properties. For example, it is well known that solitons described by the Korteweg–de Vries equation and a few other conservative model equations exhibit properties of elastic particles, while shock waves described by dissipative models like Burgers’ equation stick together as absolutely inelastic particles when colliding. The interactions of single pulses in media with modular nonlinearity considered here reveal new physical features that are still poorly understood. There is an analogy between the single pulses collision and the interaction of clots of chemical reactants, such as fuel and oxidant, where the smaller component disappears and the larger one decreases after a reaction. At equal “masses” both clots can be annihilated. In this work various interactions of two and three pulses are considered. The conditions for which a complete annihilation of the pulses occurs are indicated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Nonlinear interactions of single pulse waves propagating in dispersive and dissipative media have been extensively studied. Historically, special attention was paid to solitary waves (solitons) behaving like elastic particles [1]. The analogy between nonlinear waves and quasi-stable particles is interesting both for the understanding of the fundamental properties of matter [2] and for analyzing processes of a different physical nature [3,4,5]. Collisions between solitons were studied in conservative media with diversified types of nonlinearity [6]. However, corpuscular properties are present also for nonlinear waves in media with energy dissipation where weak shock waves collide as inelastic particles. As a result of multiple mergers, a “large particle” is formed, the mass being equal to the sum of the masses of the colliding smaller particles [7]. As far as we know, collisions in dissipative media have been studied in depth only for the case of quadratic nonlinearity. The collisions of single pulses in media with modular nonlinearity considered in this work demonstrate new properties. Before the collision, the pulses preserve their shape. Once the collision begins, a mutual absorption starts which under certain conditions leads to total annihilation of the pulses.

The term modular nonlinearity is used here as defined in the works [8,9,10]. From a mathematical point of view, it means that the modular term is present in the equation of motion. The following anharmonic oscillator is a simple example of such a nonlinear system:

The modular term g|u| replaces in Eq. (1) the usual quadratic nonlinear term \(g\, u^{2}\) . Equation (1) describes the vibration of a mass on a spring, which is piecewise linear and has higher elasticity with respect to the compression (\(k(1+g)\)) than when extended (\(k(1-g)\)). When the nonlinear parameter \(|g|<1\), Eq. (1) describes a periodic motion in a force field with the potential \(2W/k=u^{2}+g\, u|u|\).

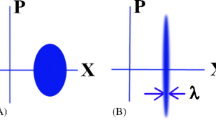

Many real media have different moduli of elasticity under tensile and compressive strains (see Fig. 1). Examples of such are construction and building materials, such as reinforced polymers and concretes [11, Chapter 1, Paragraph 10], as well as multi-phase and structurally inhomogeneous media and meta-materials.

Our derivation of a continuous model of a modular medium starts by considering the discrete chain of anharmonic oscillators (1) shown in Fig. 2.

Let the masses be located periodically along the x-direction, at equilibrium distance a from each other. The small black arrows mark their origins. The displacement of mass n is denoted by \(u_{n}\), where \(n=0, \pm 1, \pm 2, \ldots \) The nearest neighbors are connected by an ensemble of springs showing as a whole the properties of a modular nonlinearity (1). The first group of longer springs is rigidly connected to both masses, at the small solid dots in Fig. 2. The second group of shorter springs is each attached to only one mass. These springs begin to influence the system (by their compression) only after the distance between the masses is less than the spring equilibrium length.

The motion of mass of number n in this chain is described by the equation:

Let us now turn to the continuum limit, assuming that the chain period is small in comparison with the wavelength:

After substituting expansion (3) in Eq. (2), we obtain a wave equation with a modular nonlinear term:

Here \(c = a \, \sqrt{k/m}\) is the propagation velocity of a linear wave (when \(g=0\)).

Equation (4) has a remarkable property in that it permits separation of variables in some cases, despite its nonlinearity. One case corresponds to the first mode of a nonlinear standing wave in a resonator with fixed ends, i.e., when \(u(x=0,t) = 0\) and \(u(x=L,t)=0\):

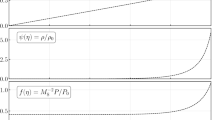

The temporal waveforms of one period of vibration (5) in the middle section of the resonator (at \(x=0.5L\)) are shown in Fig. 3, where, for convenience, the dimensionless time \(\tau = ct{/}L\) is used. These profiles correspond to the nonlinear parameter values \(g = 0, 0.2, 0.5, 0.75, 0.9\). The average of solution (5) over the period is equal to zero, which means that the displacement does not contain a constant component.

Vibration (5) consists of two sinusoidal arcs of different signs. The peak of the positive arc exceeds the peak of the negative one, but its duration is shorter. One observes an increasing difference between the shapes of the positive and negative portions with the increase in nonlinearity g. As if linear, oscillation (5) is isochronous and its period does not depend on the amplitude D:

Period (6), however, depends on the nonlinearity g. It increases with the increase in the nonlinear parameter—as \(g\rightarrow 1\). This tendency of nonlinear decrease of resonator natural frequency was observed experimentally [12,13,14].

We will now pass to the key issue of this paper, namely, to the collisions of single pulses. Equation (4) can govern the interaction of two types: collision of counter-propagating pulses; and collision of pulses running at different speeds in the same direction.

The four general types of interaction of unipolar pulses that can be realized are illustrated in Fig. 4. The following two purely positive and purely negative waves are indicated:

The subscript “+” corresponds to a wave of positive polarity, and “−” to the negative one. The superscript “R” refers to a wave running to the right, and “L” to a wave running to the left.

Separately, they behave linearly. The speed of the positive polarity wave is \(c\sqrt{1+g} \), and \(c\sqrt{1-g} \) of the wave with negative polarity. The collisions of counter-propagating waves (1 and 2 in Fig. 4) are physically similar to each other, as well as collisions of waves running in the same direction (3 and 4 in Fig. 4).

We will now confine ourselves to the analysis of collisions of pulses traveling to the right along the x-axis (3 in Fig. 4) for which Eq. (4) can now be simplified for weak nonlinearity, i.e., for \(g \ll 1\). The standard method of slowly varying profiles will be used, described in detail for example in the books [15, 16]. For a wave traveling in the positive direction of the x-axis, a solution is sought in the form

Here \(t_{1}\) is the fast variable—meaning the time is measured in a coordinate system moving with the velocity c, and \(x_{1}\) is the slow variable (\(\mu \ll 1\), see “Appendix” section) related to the smallness of the nonlinear parameter \(g\sim \mu \). Substituting (7) in (4) and neglecting the second derivative with respect to the slow coordinate, we obtain:

For the convenience of further analysis, we rewrite this equation in dimensionless notation:

where

In Formula (10), \(\omega \) means the arbitrary constant with the dimension of angular frequency, \(l_\mathrm{NL}\) is the typical nonlinear distance, and \(l_\mathrm{DISS}\) is the typical distance of dissipation. A dissipative term with a second derivative has been introduced into Eq. (9), thereby eliminating the singularities arising in solutions of nondissipative equation (8) (see below). At small values of the number \(\varGamma \) the nonlinearity dominates, and the dissipative term can be regarded as a singular perturbation. At larger values, when \(\varGamma \sim 1\) or higher, the stronger linear dissipation prevents expression of nonlinear effects.

Equation (9) is a modified form of Burgers’ equation. Other models of similar type have recently been investigated [8,9,10, 17, 18]. Here, we will now use Eq. (9) to study the interesting phenomenon of annihilation of pulses traveling in the same direction.

A curious simplicity in the equations with modular nonlinearity is that they are linear all the while the function preserves its sign, that is, when it is purely \(u>0\) or purely \(u<0\). Nonlinear effects occur only in alternating solutions. For example, a positive pulse of arbitrary shape \(u=\varPhi _{+}(\theta )\) at \(\varGamma =0\) propagates as the stationary wave \(u=\varPhi _{+}(\theta + z)\) . A purely negative pulse also propagates without changing its shape, but at a different speed, \(u=\varPhi _{-}(\theta - z)\). Because of this difference in velocities, pulses can approach each other and start to interact.

The collision of two nonoverlapping pulses of different polarities was considered only for the case \(\varGamma = 0\) [8]. First the distance between the pulses decreases as the pulses propagate linearly with different velocities. When they reach each other, a nonlinear interaction begins. After the disappearance of one of the two pulses, the interaction stops, and once again the surviving pulse propagates linearly. Consequently, the interaction of two solitary waves in a modular medium reveals properties that are different from the effects observed at elastic collisions of solitons and inelastic mergers of shock waves. There exists an analogy between the single wave collision in modular media and the interaction of clots of chemical reactants, such as a fuel and an oxidant. A chemical reaction (for example, burning) results in that the smaller component disappears, and the larger second mass decreases. At equal masses of fuel and oxidant, these clots can completely disappear or annihilate.

An analytic description of the collision of two pulses is performed below. First, we find the stationary solution of Eq. (9), so we are looking for a wave that does not change shape during propagation:

If the constant \(\beta \) is positive, it indicates an increase in the wave velocity in comparison with the velocity c. Substituting (11) into (9), we arrive at an ordinary differential equation, which is then integrated once to

Here \(C^{2}\) is the integration constant. Since Eq. (12) is an autonomous equation, the positive and negative branches of the solution can be sewn together at \(T=0\):

The solution to Eq. (12) satisfying condition (13) has the form:

It is seen that not only function (14) is continuous at the point \(T=0\), but also its first derivative. Solution (14) describes a step or shock wave with a finite front width, which is proportional \({\sim }\varGamma \). The jump occurs between the following two values of the wave function:

Thus, the constant that determines the velocity of the stationary front depends on the values of the wave function at infinity:

The position of the front, as follows from (11), is found from the equation:

Since the points corresponding to the values of the wave function \(|u_{1}|\), \(|u_{2}|\) lie both on front (14) and on the smooth sections of the wave, Eq. (17) should be supplemented by these relations, following from the solution of Eq. (9) together with \(\varGamma = 0\): \(u_{1,2} = \varPhi _{\pm } (\theta _\mathrm{FR}\pm z)\), having the form

Here \(\varPhi _{\pm }^{-1}\) are the inverse shape functions of \(\varPhi _{\pm }\).

Thus, we obtain a system of three nonlinear equations for the three unknown functions \(\theta _{FR}(z)\), \(|u_{1}(z)|\) and \(|u_{2}(z)|\). A similar approach was used to calculate the parameters of shock described by the usual Burgers equation (see [19, Problems 2.18–2.23]). Of course, this system cannot be solved for all possible forms of pulse signals.

Consider the simplest case when two pulses of different polarities form a common front. The form of the original signal (at \(z=0\)) is:

The initial peak values \(u_{10}\) and \(u_{20}\) and their initial durations \(\theta _{10}\) and \(\theta _{20}\) are assumed to be positive.

For pulses (19), Eq. (18) takes the form:

It is remarkable that nonlinear system (17), (20) has two integrals, and therefore its solution can be written in explicit form:

From this the parameters of the shock front \(|u_{1}(z)|\) and \(|u_{2}(z)|\) are calculated, and its position \(\theta _\mathrm{FR}(z)\) is determined from any of Eq. (20).

The simplest solution corresponds to when the areas of the positive and the negative pulses are equal:

and from integrals (21), (22), it follows that

As can be seen from formula (25), the annihilation occurs at the definite distance \(z=z_\mathrm{ANN}\) where the shock front displacement reaches its maximum value \(|\theta _\mathrm{FR}|_\mathrm{MAX}\):

Necessary annihilation condition (24) contains the general statement that complete annihilation of any number of pulses takes place if the total initial linear momentum of all pulses is zero. That the linear momentum L is conserved during propagation and interactions follows from Eq. (9):

Consequently, if the initial momentum \(L(z=0)\)—i.e., the area under the initial curve \(u(0,\theta )\)—is zero, pulses of different polarities disappear if they collide. For this to happen, the positive pulse should be placed behind the slower negative pulse.

It is noteworthy that conservation law (26) is not violated even in the case of a dissipative medium (\(\varGamma \ne 0\)) [15]. The annihilation effect exists there too, and it is therefore interesting to consider this more general case. The existence of dissipation helps us to eliminate the two bothersome singularities, namely the breaks of the wave and the breaks of its derivative [8, 10], which are eliminated by dissipative smoothing [8]. Consequently, in order to find a continuous solution for a wave in a modular medium one must solve Eq. (9) with a coefficient \(\varGamma \ne 0\). Numerical simulation results of the collision and annihilation processes are shown in the figures that follow.

Collision of two single pulses having initially (at \(z=0\)) the triangular shapes (curves 1). Curves 2, 3 and 4 show the form of colliding pulses at distances \(z=2, 4, 9\). Solid lines correspond to weak dissipation \(\varGamma = 0.04\), and dashed lines to stronger dissipation \(\varGamma = 0.2\)

The process of collision of two pulses of equal durations but different amplitudes and polarities (curve 1) is shown in Fig. 5. Before the collision, the negative and positive pulses approach each other while propagating at constant speeds and stable shapes. A nonlinear interaction begins once the pulses start overlapping (curve 2). As a result, the negative pulse with a smaller amplitude is absorbed by the positive pulse (i.e., at a certain distance negative pulse disappears, curve 3). In turn, the amplitude of the positive pulse decreases. During this interaction, the speed of the positive pulse is reduced. After the disappearance of the negative pulse, the nonlinear interaction is terminated and the speed of the positive pulse returns to its original value. At this stage, again only linear dissipation distorts the shape, resulting in a broadening of the positive pulse and reduction in its peak amplitude.

It is valuable to see how the total energy decreases. The energy is proportional to the integral of the square of the wave function:

The energy of two single pulses shown in Fig. 5 as a function of the distance z. Nonlinear decay is caused by the interaction of pulses which starts after their collision. Curves 1, 2, 3 and 4 correspond to increasing dissipation \(\varGamma = 0.002, 0.04, 0.2, 0.6\)

In Fig. 6 dependencies of energy on distance E(z) are constructed for different values of \(\varGamma = 0.002,\) 0.04, 0.2, 0.6 (curves 1–4). Let us first discuss how the energy decreases in a weakly dissipative medium (curve 1). During the first stage, the pulses are spatially separated and approach each other. Their total energy slowly decreases due to the usual linear absorption in the medium. During the second stage, the collision of pulses begins (curve 2 in Fig. 5). As a result of their intersection, a nonlinear absorption is activated, and the energy decreases noticeably faster. During the third stage, when the negative pulse has been completely absorbed (curves 3 and 4 in Fig. 5), the nonlinearity is de-activated and the energy loss of the surviving positive pulse again goes slowly, within the framework of linear theory.

As the dissipative parameter increases, the stage of strong nonlinear damping becomes less pronounced and is for \(\varGamma = 0.6\) in curve 4 in Fig. 6 not noticeable.

In Fig. 7 the positive and negative peak disturbances (maximum and minimum) of two colliding single pulses are shown as functions of the distance. The processes of collision are illustrated in Fig. 5. One can see that peaks decrease with increase in distance. Curves 1, 2, 3 and 4 correspond to increasing linear dissipation: \(\varGamma = 0.002, 0.04, 0.2\) and 0.6. As in Fig. 6, it is possible to distinguish the range where the pulses overlap and the added nonlinear absorption has an effect. This is most clearly seen in curve 1 where \(\varGamma = 0.002\).

Magnitudes of positive and negative peaks of the two colliding single pulses shown in Fig. 5. Peaks decrease with increase in distance z. Curves 1, 2, 3 and 4 correspond to different dissipations \(\varGamma = 0.002, 0.04, 0.2, 0.6\)

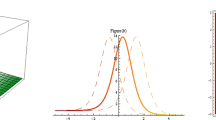

The sequential steps in the collision of two identically shaped pulses but with different polarities are shown in Fig. 8. The initial wave is given by curve 1. First the pulses do not overlap, and there is no interaction between them, but they keep closing in on each other. Curve 2 corresponds to the beginning of nonlinear interaction of the colliding pulses. Curve 3 contains the shock front, which is already smoothed by dissipation. The nonlinear mutual absorption (compare curves 3–7) continues as long as both pulses exist until they disappear.

A similar process of collision and annihilation of two pulses having initial shape in the form of negative and positive half-periods of a sinusoid is shown in Fig. 9.

Process of collision and annihilation of two pulses represented as shifted half-periods of sinusoid (dashed line). At first, the pulses approach each other without interacting (curve 1). Then, the interaction begins, and it ends with annihilation. Curves 1–4 correspond to increasing distances z. The dissipation number \(\varGamma = 0.05\) is fixed

The condition \(L(z=0)=0\) is also necessary for the annihilation of pulses in more complicated processes. One example is the triple collision of one positive and two negative pulses shown in Fig. 10. The initial disposition of three pulses is shown by curve 1. (The arrows indicate the pulses’ relative velocities—all pulses are still propagating to the right, but with different speeds.) At the input, at \(z=0\), the pulses are separated in time and begin to approach one another. The first collision occurs between a pulse of positive polarity and the closest smaller negative pulse. Curve 2 shows how the large positive pulse absorbs the first negative pulse, itself diminishing in magnitude. After the first collision, two pulses remain (curve 3). Then, a second collision happens between the remaining positive pulse and the second negative pulse (curve 4). After the second collision, all the pulses have disappeared (curve 5).

As final remark should be pointed out that we do not know of other works on nonlinear annihilation and, apparently, research in this direction will be continued. At the same time, it is of interest to study processes that are opposite to annihilation, namely the creation of new waves from a wave vacuum. The birth of counter-propagating waves as a result of self-reflection has long been studied both theoretically and experimentally (see [15, Chapter 7]). However, the corpuscular analogy was not analyzed in these prior works. Evidently, studies based on these new models with new types of nonlinearity represent mathematically and physically intriguing issues.

References

Remoissenet, M.: Waves Called Solitons. Springer, Berlin (1999)

Nguyen, J.H.V., Dyke, P., Luo, D., et al.: Collisions of matter-wave solitons. Nat. Phys. 10, 918–922 (2014)

Tang, Y., Tao, S., Zhou, M., et al.: Interaction solutions between lump and other solitons of two classes of nonlinear evolution equations. Nonlinear Dyn. 89, 429–442 (2017)

Wang, X.M., Zhang, L.L.: The nonautonomous N-soliton solutions for coupled nonlinear Schrödinger equation with arbitrary time-dependent potential. Nonlinear Dyn. 88, 2291–2302 (2017)

Pal, R., Kaur, H., Raju, T.S., et al.: Periodic and rational solutions of variable-coefficient modified Korteweg–de Vries equation. Nonlinear Dyn. 89, 617–622 (2017)

Biswas, A.: Solitary wave solution for KdV equation with power-law nonlinearity and time-dependent coefficients. Nonlinear Dyn. 58, 345 (2009)

Rudenko, O.V.: Nonlinear sawtooth-shaped waves. Physics-Uspekhi 38, 965–989 (1995)

Rudenko, O.V.: Equation admitting linearization and describing waves in dissipative media with modular, quadratic and quadratically cubic nonlinearities. Dokl. Math. 94(3), 703–707 (2016)

Rudenko, O.V.: Modular solitons. Dokl. Math. 94(3), 708–711 (2016)

Rudenko, O. V., Hedberg, C.M.: A new equation and exact solutions describing focal fields in media with modular nonlinearity. Nonlinear Dyn. 89(3), 1905–1913 (2017)

Ambartsumyan, S.A.: Elasticity Theory of Different Moduli. China Railway Publishing House, Beijing (1986)

Haller, K.C.E., Hedberg, C.M.: Constant strain frequency sweep measurements on granite rock. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100(6), 068501 (2008)

Guyer, R.A., Johnson, P.A.: Nonlinear Mesoscopic Elasticity: The Complex Behaviour of Granular Media Including Rocks and Soils. Wiley, Hoboken (2009)

TenCate, J.A., Pasqualini, D., Habib, S., Heitmann, K., Higdon, D., Johnson, P.A.: Nonlinear and nonequilibrium dynamics in geomaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93(6), 065501 (2004)

Rudenko, O.V., Soluyan, S.I.: Theoretical Foundations of Nonlinear Acoustics. Plenum, Consultants Bureau, New York (1977)

Gurbatov, S.N., Rudenko, O.V., Saichev, A.I.: Waves and Structures in Nonlinear Nondispersive Media. Springer, Berlin (2011)

Nazarov, V.E., Kiyashko, S.B., Radostin, A.V.: Self-action of ultrasonic pulses in a marble rod. Radiophys. Quantum Electron. 58, 729–737 (2016)

Radostin, A.V., Nazarov, V.E., Kiyashko, S.B.: Propagation of acoustic unipolar pulses and periodic waves in media with quadratic hysteretic nonlinearity and linear viscous dissipation. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 52, 44–51 (2017)

Rudenko, O.V., Gurbatov, S.N., Hedberg, C.M.: Nonlinear Acoustics Through Problems and Examples. Trafford, Victoria (2011)

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Russian Scientific Foundation Grant No. 14-22-00042.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Detailed derivation of equations 8 and 9

Appendix: Detailed derivation of equations 8 and 9

At a preliminary acquaintance with the manuscript, some experts expressed the desire to see a more detailed derivation of Eqs. (8) and (9). The following is rather standard and is described, for example, in monographs [15, 16] and in the textbook (collection of problems) [19]. Of course, it is convenient for readers to see the material within one article, without referring to literary sources. Therefore, a detailed derivation of the equations is given in this “Appendix” section.

The system of Lagrange equations for the chain shown in Fig. 2 has the form:

Here the dot ( \(\dot{}\) ) means differentiation with respect to time, L is the Lagrange function, and F is the dissipative Rayleigh function. The dissipation is due to friction in the springs, which depends on the speed of their deformation. For the system under consideration, the specific form of these functions is:

Substituting (29) into Lagrange’s equations (28), we obtain a system of equations of motion:

When differentiating, it is convenient to use the formula \(\partial u_{n}/\partial u_{i} = \delta _{ni}\), where \(\delta _{ni}\) is the Kronecker unit tensor.

We pass in system (30) to the continuum limit, using the expansions in series in Formula (3) with respect to the small parameter, which is the ratio of the period of the chain to the wavelength. In this case, the system of ordinary differential equations (30) transforms into a partial differential equation:

This equation generalizes (4), since it additionally takes into account dissipative losses.

From Eq. (31), one can obtain an evolution equation using the standard simplification procedure, known as the slowly varying profile method [15, 16, 19].

We seek the solution of Eq. (31) in the form of a wave traveling in the positive direction of the x-axis and slowly changing its shape due to the effects of nonlinearity and dissipation:

Here, “slowly” means that after having propagated distances on the order of the wavelength, the waveform has changed insignificantly. A small parameter \(\mu \ll 1\) is a constant on the order of the ratio of the nonlinear and dissipative terms of Eq. (31) to any of the linear terms of this equation. Substituting (32) into (31), we obtain:

When estimating the order of smallness of various terms in Eq. (33), it is convenient to assume formally that the coefficients g and \(\beta \) are small in the order \(\mu \). We see that the terms of the order \(\mu ^{0} (=1)\) cancel each other, and we will neglect the terms of order \(\mu ^{2}\). In this case, only the terms of order \(\mu ^{1}\) remain in (33), which after integration with respect to \(t_{1}\) form an evolutionary equation of the first order in the variable \(x_{1}\). Taking into account that \(\mu \partial /\partial x_{1} = \partial /\partial x \) we have:

Passing to dimensionless variables (10), we arrive at Eq. (9):

Here \(\varGamma = \beta \omega / g\). Equation (35) in the text of the work is referred to as “Burgers-type equation with modular nonlinearity.” In the absence of dissipation (\(\varGamma = \beta = 0\)), a first-order partial differential equation (8) is obtained from (34) and (35), and it makes sense to call it a “Hopf-type equation with a modular nonlinearity.”

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hedberg, C.M., Rudenko, O.V. Collisions, mutual losses and annihilation of pulses in a modular nonlinear medium. Nonlinear Dyn 90, 2083–2091 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-017-3785-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-017-3785-6

Keywords

- Nonlinear partial differential equation

- Mutual loss

- Annihilation

- Modular nonlinearity

- Bimodular media

- Pulse interaction