Abstract

Introduction/Purpose

Poverty-reduction efforts that seek to support households with children and enable healthy family functioning are vital to produce positive economic, health, developmental, and upward mobility outcomes. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is an effective poverty-reduction policy for individuals and families. This study investigated the non-nutritional effects that families experience when receiving SNAP benefits.

Methods

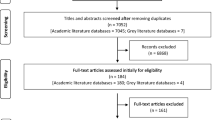

We conducted a scoping review using the PRISMA Guidelines and strategic search terms across seven databases from 01 January 2008 to 01 February 2023 (n=2456). Data extraction involved two researchers performing title-abstract reviews. Full-text articles were assessed for eligibility (n=103). Forty articles were included for data retrieval.

Results

SNAP positively impacts family health across the five categories of the Family Stress Model (Healthcare utilization for children and parents, Familial allocation of resources, Impact on child development and behavior, Mental health, and Abuse or neglect).

Discussion/Conclusion

SNAP is a highly effective program with growing evidence that it positively impacts family health and alleviates poverty. Four priority policy actions are discussed to overcome the unintentional barriers for SNAP: distributing benefits more than once a month; increasing SNAP benefits for recipients; softening the abrupt end of benefits when wages increase; and coordinating SNAP eligibility and enrollment with other programs.

Significance

Poverty-reduction efforts that invest in children have especially significant positive benefits by producing positive economic, health, developmental, and upward mobility outcomes. SNAP is among the leading poverty-reducing policies and enrolls the largest number of participants for both nutritional and non-nutritional benefits.

AbstractSection What this study adds?To our knowledge, no study has synthesized the non-nutritional impact of SNAP on family health. We found that SNAP positively impacts family health across five categories of the Family Stress Model (Healthcare utilization for children and parents, Familial allocation of resources, Impact on child development and behavior, Mental health, and Abuse or neglect). Further, we present four policy actions resulting from this scoping review that deserve attention from policymakers, program administrators, and retailer establishments: distribute benefits more than once a month; increase SNAP benefits for recipients; soften the abrupt end of benefits when wages increase; and coordinate SNAP eligibility and enrollment with other programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the largest federal nutrition assistance program in the United States (Caswell & Yaktine, 2013). SNAP provides monthly cash assistance to families meeting eligibility standards through an Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) card, which is used to purchase food items at participating grocery stores. The program was launched in 1964 with the passage of the Food Stamp Act. While the overall structure of the program has remained relatively constant, changes to the program (primarily achieved through the periodical reauthorization of the Farm Bill) have included adjustments to its funding amount, modifications to eligibility requirements, and the introduction of an electronic benefit transfer card, among others.

Families with children make up the largest demographic of SNAP participants (Center on Budget & Policy Priorities, 2023). Families with children also make up the largest demographic in poverty (Cellini et al., 2008). Children living below the federal poverty line are associated with increased odds of being overweight (Gupta et al., 2007), worsened Behavioral Problem Index scores (a measure of socio-emotional development) (Lee & Zhang, 2022), and increased odds of poverty later in life that contribute to generational cycles of deprivation (Wagmiller & Adelman, 2009). Poverty-reduction efforts that invest in children have significant benefits and enable healthy family functioning by producing positive economic, health, developmental, and upward mobility outcomes (Collyer et al., 2022).

Given SNAP’s objective to reduce poverty and increase resources for the purchase of food, extensive research has focused on evaluating the nutritional benefits and economic impact of SNAP. (Engel & Ruder, 2020; Holley & Mason, 2019; Mande & Flaherty, 2023; Ryan-Ibarra et al., 2020) For example, studies have monitored the impact of SNAP on the consumption of sugar sweetened beverages (Andreyeva et al., 2015), fruit and vegetable consumption (Verghese et al., 2019), and child weight status (Hudak & Racine, 2019).

While there is much literature and many systematic reviews studying the nutritional benefits of SNAP, an emergent and growing body of literature investigates the impact of SNAP on the family beyond its direct effects on food security and nutrition (Breck, 2018; Engle & Black, 2008; Heflin et al., 2017; Hoynes et al., 2016; Maguire-Jack et al., 2022; Parolin, 2021; Sonik, 2016). A broad review of these non-nutritional impacts of SNAP has not been conducted. Thus, this scoping review focused on the non-nutritional influence of SNAP on family functioning and child health and well-being and their policy implications, including identifying additional areas for research.

Methods

Following PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2021), we conducted a scoping review to explore the non-nutritional impact of SNAP on the family and child health and well-being. Our search terms (see Appendix 1) were informed by the component descriptors of the Family Health Scale (long form) and the Family Stress Model (Crandall et al., 2020). We conducted a search in seven databases (see Appendix 1) using a list of familial terms, outcome terms, and SNAP synonyms on February 1, 2023. We included all articles published from January 1, 2008 to February 1, 2023 given that the 2008 Farm Bill significantly altered governmental nutrition programs, increased funding, and renamed it the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Articles were compiled in EndNote Web and were manually deduplicated.

The codebook (see Appendix 2) and search terms were developed by co-authors, including two reference librarians. Based on the codebook, two co-authors screened the retrieved articles’ titles and abstracts, and the reasons for exclusion were recorded. Questions on the eligibility of articles were resolved through discussions with a third researcher. The articles included in the scoping review were categorized according to Conger et al., (1994) Family Stress Model descriptors. We defined those five family stress outcomes in this study as familial allocation of time/money, mental health of children or parents, abuse or neglect of children or other family members, healthcare utilization for children or parents, and developmental/behavioral results in children. Two co-authors who independently reviewed the articles using the codebook in Google Forms extracted the full-text review data. The entire research team used an objective definition-based consensus discussion to arbitrate less than five eligibility and coding disagreements. Lastly, two researchers reviewed the final number of included articles to compile relevant information into tables. Another trained researcher verified a randomly-selected one-third of the articles.

The inclusion criteria for the scoping review included the following:

-

Publication date: 01/01/2008–02/01/2023

-

Publication language: English

-

Geographic focus: United States

-

Study design: Empirical studies only

-

Target population: Families/children

-

Independent variable: SNAP (participation, eligibility, policies)

-

Dependent variables: Non-food-related outcomes

One of the co-authors evaluated the quality of final articles included in this scoping review using the 2018 Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., 2018) (see Table 2 for the MMAT score for each article). The MMAT appraises the quality of empirical research included in systematic or scoping reviews of mixed studies, allowing different methodological research to be compared to each other. Articles are scored from 1–5, where 1 is the lowest research quality and 5 indicates the highest research quality.

Results

Study Characteristics

The initial database searches yielded 3581 articles. After deduplication, 1125 articles were excluded, resulting in 2456 articles. Following the title-abstract screening, 2353 articles were excluded, reducing the total to 103 articles for the full-text review. After the full-text review, 57 articles were excluded, resulting in the final total of 46 articles. See Fig. 1 for the PRISMA diagram.

Several different SNAP-related independent variables emerged as ways to examine the impact of this program. The majority of studies compared SNAP participants to socioeconomically comparable, income-eligible SNAP non-participants (n = 27). Other common SNAP-related independent variables included the timing of SNAP fund distribution throughout the month (n = 9) and SNAP participation before and after a policy or implementation change (n = 4). The methodological design of included studies were quantitative (n = 43), qualitative (n = 2), and mixed-methods (n = 1). See Table 2 for a full listing of SNAP-related independent variables and study designs. Major themes identified included SNAP’s effect on healthcare utilization for children or parents (n = 9), familial allocation of resources such as time or money (n = 15), behavioral or developmental results in children (n = 12), mental health of children or parents (n = 7), and abuse or neglect of children or other family members (n = 8). The majority of articles (n = 27) had the highest MMAT score of 5, indicating high empirical research quality. Fewer articles (n = 16) had an MMAT score of 4, while only a few (n = 3) articles had an MMAT score of 3. Of studies with an MMAT score of 3, two studies were categorized under familial allocation of resources, and one was grouped with articles on mental health. No articles were excluded based on MMAT findings. See Table 1 for a description of included studies. The five major themes are expounded upon below.

Healthcare Utilization for Children and Parents

The majority of examined studies (n = 7) found a positive association between SNAP participation and receiving needed medical care (Arteaga et al., 2021; Bronchetti et al., 2019; Ettinger de Cuba et al., 2019a, 2019b; Miller & Morrissey, 2021; Morrissey & Miller, 2020; Shaefer & Gutierrez, 2013). In order to control for income, most studies limited their study population to either those under a certain income threshold, who did not have private health insurance, or who participated in SNAP (n = 7). One study looked at ecological data, and another controlled for income through statistical analysis. Those who became SNAP ineligible due to income increases experienced more missed healthcare. Results also showed that higher numbers of early childhood wellness visits were correlated to increases in SNAP benefit amounts and the purchasing power of SNAP benefits relative to the local cost of food items. One study found that SNAP participants were more likely than their non-SNAP counterparts to receive needed dental care and eyeglasses. However, they were also more likely to delay seeking care and could not afford prescription medication (Miller & Morrissey, 2021). Another study found no major difference in healthcare expenditures for children between SNAP participants and non-SNAP participants (Rogers et al., 2022). Regarding the timing of benefit distribution, it was found that non-urgent emergency room visits were lower on the day of SNAP benefit disbursement than on other days for all ages (Cotti et al., 2020).

A variety of methods were used to account for the potentially confounding role of public health insurance programs such as Medicaid in these results. Some study samples (Arteaga et al., 2021; Cotti et al., 2020) only included Medicaid participants, while other studies (Bronchetti et al., 2019; Miller & Morrissey, 2021; Morrissey & Miller, 2020) specifically controlled for Medicaid or other health insurance. The remaining studies that found a correlation between SNAP participation and healthcare usage (Ettinger de Cuba et al., 2019a, 2019b; Shaefer & Gutierrez, 2013) used various proxy measures to ensure that the entire sample was low-income and therefore did not vary with regard to Medicaid eligibility.

Familial Allocation of Resources

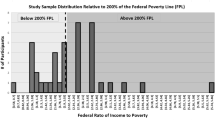

SNAP participation impacted resource management in various ways, and a majority of articles indicated improved resource allocation (n = 8). Most studies controlled for the effects of income by limiting their study population below a certain percentage of the federal poverty line (n = 6) or to only SNAP participants (n = 6); those who didn’t looked at other measures, such as food security or youth homelessness (n = 3). SNAP participation reduced housing and utility payment delays (Shaefer & Gutierrez, 2013) and overall material hardship (McKernan et al., 2021), and reducing SNAP benefits led to increased odds of housing instability and being behind on utility bills (Ettinger de Cuba et al., 2019b). Several studies (n = 5) noted that SNAP participants experience a majority of the poverty-reducing effects of SNAP towards the beginning of the month, and rely more on non-SNAP assistance, such as food pantries or social networks, at the end of the benefit cycle than at the beginning (Kinsey et al., 2019; Laurito & Schwartz, 2019; Nieves et al., 2022; Schenck-Fontaine et al., 2017; Weinstein et al., 2018). The literature is inconclusive as to SNAP’s effects on family homelessness (Parolin, 2021) as well as young mothers’ usage of other public assistance (Cheng, 2010; Mabli & Worthington, 2017; Vartanian et al., 2011). SNAP was associated with less time spent on meal preparation, non-grocery food shopping (i.e., prepared food, fast food, etc.), and eating (Beatty et al., 2013). For a full list of results, see Table 2.

Impact on Child Development and Behavior

A slight majority of studies (n = 6) found that SNAP was correlated with improvements in child development and behavior, (Barr & Smith, 2022; Bolbocean & Tylavsky, 2021; East, 2020; Ettinger de Cuba et al., 2019a, 2019b; Hong & Henly, 2020), although results were mixed. Others (n = 5) found that SNAP participation and the timing of SNAP benefit receipt was negatively associated with child development and behavior (Cotti et al., 2018; Gassman-Pines & Bellows, 2018; Gennetian et al., 2016; Hong et al., 2020; Rothbart & Heflin, 2023). Some of these studies look at ecological data including data on poverty or the impact of SNAP policies (n = 2). Others study only welfare or specifically SNAP participants past or present (n = 6), and still others look at income or other poverty measures to control the effect of income on SNAP (n = 3). SNAP benefits had a net positive correlation with child development (Bolbocean & Tylavsky, 2021; East, 2020; Ettinger de Cuba et al., 2019a, 2019b), reduced the likelihood of later criminal conviction (Barr & Smith, 2022), and improved math skills among students in deep poverty (Hong & Henly, 2020). On the negative side, SNAP-participating students received lower scores on various tests than their non-SNAP peers (Rothbart & Heflin, 2023), performed worse on tests immediately before and after SNAP distribution (Cotti et al., 2018; Gassman-Pines & Bellows), and had a higher likelihood of bullying, being bullied, and general disciplinary infractions (Gennetian et al., 2016; Hong et al., 2020). For a full list of results, see Table 2.

Mental Health

Participating in or increased SNAP benefits were largely associated with improved mental health in children and parents across studies (n = 7) (Bergmans et al., 2017; Ettinger de Cuba et al., 2019b; Frank & Sato, 2022; Munger et al., 2016; Pryor et al., 2023; Steimle et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020). All studies listed either have a study population made up entirely of past or present SNAP participants (n = 3) and/or control for income level or other resource measures (n = 4). Two studies measured SNAP as secondary or moderating variables. SNAP participation was associated with reduced maternal depression (Munger et al., 2016), and loss of SNAP was associated with increased maternal depression (Ettinger de Cuba et al., 2019b; Munger et al., 2016). However, one article suggested that SNAP benefits only decreased maternal depression if the mother did not think SNAP or government-sponsored programs limited her personal freedom (Bergmans et al., 2017). SNAP participation was associated with decreased parental stress among most studies. Parental stress increased in one study because children in SNAP-participating families were less cooperative than children in non-SNAP families, presumably due to school closures affecting one group more than the other (Steimle et al., 2021). Another study found that while SNAP participation decreased parental stress, it also decreased parental engagement due to the requirements of food preparation crowding out spending time together (Wang et al., 2020). For adolescents, SNAP was found to buffer the harmful effects of food insecurity on depression and other mental health concerns later in young adulthood (Frank & Sato, 2022; Pryor et al., 2023).

Abuse or Neglect

A majority of studies found positive impacts on abuse and neglect associated with SNAP participation (n = 8) (Austin et al., 2023; Bullinger et al., 2021; Carr & Packham, 2020; Cho & Lightfoot, 2022; Johnson-Motoyama et al., 2022; Millett et al., 2011; Morris et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2021). Some of these studies looked at SNAP as a secondary factor (n = 3). Others looked at the effects of SNAP policy changes (n = 3). Still others accounted for potential confounding variables in other ways (n = 2), such as looking at ecological data on income or unemployment. Various studies (n = 4) found that SNAP participation was associated with less child maltreatment (Austin et al., 2023; Johnson-Motoyama et al., 2022; Millett et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2021). However, Morris and colleagues (2019) found that counties with higher percentages of SNAP participation were associated with higher risk of child abuse and neglect, though these results could be due to self-selection bias. Similarly, Cho and Lightfoot (2022) observed that for parents with disabilities, receiving SNAP benefits significantly increased the risk for substantiated child maltreatment reports. Other articles indicated that child maltreatment decreases when monthly SNAP benefits are distributed at the beginning of the month rather than distributed throughout the month (Carr & Packham, 2020) and as proximity to retailers that accept SNAP benefit cards increases in rural areas (Bullinger et al., 2021).

Discussion

The Family Stress Model seeks to explain how stressors such as poverty create many adverse outcomes (Conger et al., 1994). In this model, as families encounter economic hardship, the interplay between economic pressure, parental depression, and marital conflict negatively impacts child socio-emotional development, school engagement, academic performance, and health outcomes. Poverty disrupts healthy family functioning and supportive parent–child relationships (Gard et al., 2020). Overall, SNAP participation was associated with clear improvements in four of the five categories of family outcomes, with one of the family outcomes having only a slim majority of positive results. Taking the Family Stress Model as a foundation, we propose Fig. 2 as a possible mechanism and ecology by which SNAP improves family outcomes. We do not have the data to definitively establish causation, making this a valuable area for future research.

Family Healthcare Utilization

Overall, SNAP participation is associated with increased healthcare use. This positive connection between SNAP and health care has several potential causes. First, improving basic nutrition improves health, thus diminishing the need for medical treatments as a result of better food choices. Similarly, Serchen et al., 2022 found that leveraging nutrition assistance programs during the pandemic resulted in improved public health. Second, SNAP participation can reduce the likelihood of participants being forced to choose between paying for food or paying for medicine. For example, money saved through SNAP, though modest, may help offset a portion of current or future costs of medications (Serchen et al., 2022). Third, SNAP participants with chronic diseases—such as diabetes, hypertension, and coronary heart disease—are shown to experience improved cost savings compared to nonparticipants (Carlson & Keith-Jennings, 2018; Lee et al., 2019; Liu & Eicher-Miller, 2021). Our findings support conclusions that would be drawn from the Family Stress Model: that availability of SNAP resources increases family healthcare use.

Many studies explored the association between SNAP participation, health outcomes, and healthcare use (n = 9). Most of these studies mentioned “foregone healthcare visits.” Based on the number and commonality of dependent variables, we recommend a robust variance estimation meta-analysis to identify how SNAP affects healthcare access or costs—a key consideration for policymakers, healthcare providers, and other involved parties.

Family Mental Health

Several studies found that SNAP participation was strongly associated with improved mental health in children and parents. These findings support research that associates decreased parental stress with decreased child stress through biological pathways (Lupien et al., 2000; Yoshikawa et al., 2012). Better nutrition through SNAP may also improve mental health (Grajek et al., 2022). These strong associations between SNAP participation and improved mental health outcomes validate the Family Stress Model and show potential mechanisms by which SNAP improves mental health for the whole family.

Familial Allocation of Resources

Many studies found a correlation between SNAP participation and improved family resource allocation. SNAP enabled households to devote more money to non-food-related payments than non-SNAP-participating households (Kim, 2016). However, SNAP families still faced difficulties, especially near the end of the month. Coping mechanisms included borrowing money, parents skipping meals to feed children, and the whole family eating more unhealthy food. Difficulties may arise from a variety of factors, including benefit amounts being too low to last throughout the month (Nieves et al., 2022; Schenck-Fontaine et al., 2017), lack of financial literacy (Weinstein et al., 2018), and SNAP distribution occurring only once a month (Schenck-Fontaine et al., 2017).

Child Behavior and Development

In general, SNAP participation was associated with improved behavioral and developmental outcomes in children. The SNAP cycle is a recurring theme—often, positive behavioral outcomes decrease towards the end of the SNAP month. Our results suggest that the positive economic effects of SNAP benefits decrease as the month goes on because of resources running low, which findings align with the Family Stress Model. Research shows that child behavior is vulnerable to slight shifts in nutrition (Shankar et al., 2017), which may occur as families employ coping strategies that shift to less nutritious but more affordable foods consumed towards the end of the benefit cycle. Additionally, extreme financial hardship is considered an adverse childhood experience (ACE). ACEs in early childhood are linked to behavioral problems in children as they grow up (Choi et al., 2019).

Abuse and Neglect

A majority of studies found improved abuse and neglect markers associated with SNAP. Limited access to approved SNAP retail stores, parental disability, inefficient timing of benefits, and strict income eligibility were major reasons for the results found on SNAP participation and familial abuse and neglect. Nevertheless, the majority of studies have shown that SNAP eligibility is associated with fewer cases of abuse and neglect. A recent study by Austin et al. (2023) on expanding SNAP income eligibility by eliminating the asset test—currently an optional policy action at the state level—resulted in significant reductions in CPS investigations of child maltreatment. This finding increased over time for Black and white children, affirming the positive impact of family-friendly policies on child health and well-being. Policy changes that increase SNAP accessibility address both food insecurity and child maltreatment which are among several major ACEs (Bethell et al., 2017). Helping families become food-secure can improve family functioning through effective resource allocation, which in turn promotes healthy interactions within the family.

Policy Actions Suggested

Two primary policy actions emerged from our work, which are directed toward state agencies managing SNAP benefits, state and federal policymakers legislating SNAP, and food retailers selling SNAP food items. These actions may enhance SNAP’s ability to nourish needy families, stabilize household resources, improve healthcare usage, and reduce poverty among needy households (Carlson & Keith-Jennings, 2018). Equally important, these policy actions, including reducing some of the administrative barriers noted above, may help address some unintentional and unanticipated adverse consequences of SNAP participation. These are achievable priorities, given a reasonably steady history of bipartisan political support for many essential policy improvements to SNAP, including more recent discussions formalized in 2018 and 2020 (Franckle et al., 2019).

First, distributing SNAP benefits throughout the month rather than once a month is a leading policy change priority. While benefit amounts and eligibility may remain the same, distributing SNAP resources at least twice a month may help families stretch SNAP benefits more effectively and provide many benefits, including improved diet quality, better healthcare usage, mental health, better budgeting, and other positive benefits (Cotti, 2020; Bronchetti et al., 2019).

Second, eliminate an eligibility benefit cliff by gradually reducing benefits when income limits and work requirements deadlines pass for families with children. Softening the abrupt end of SNAP participation when wages increase or work requirement deadlines pass is a frequently mentioned policy change priority (Ettinger de Cuba, 2019b; Hoynes & Schanzenbach, 2012; Neuert et al., 2019; Karpman et al., 2019; Gassman-Pines & Schenck‐Fontaine, 2019).

As identified by other studies, future research should focus on additional policy actions for SNAP since they build from or complement the policy actions we identified. First, increasing SNAP benefit payments to match the cost of food, especially with current inflationary trends, is critical to research. For example, research could consider how regionally adjusted benefits to local food prices may help policymakers consider how much SNAP benefits may change (Austin et al., 2023; Christensen & Bronchetti, 2020; Gregory & Coleman-Jensen, 2013). Second, coordinating SNAP eligibility and enrollment with other welfare services is recommended by studies outside this scoping review (Herman et al., 2023; Serchen et al., 2022; Thorndike et al., 2022). Researchers should study how and why better coordination for welfare system enrollments may reduce or end some cyclical issues that SNAP participants face.

Future research on the family health impact of SNAP needs better assessment measures. The Family Health Scale (FHS) (Crandall et al., 2020), in short or long forms, and the Family Star Plus assessment (Good & MacKeith, 2021) can help evaluate the multiple dimensions of family impact and the availability and implementation of family-friendly policies. Measures of policy and health impact on the family as a collective unit (Prime et al., 2020) may also be employed.

Limitations

Scoping reviews have a broader focus than systematic reviews. With the emphasis on breadth, there was the possibility of missing critical details that aid in interpreting study findings. We attempted to provide depth by considering studies that included dependent variables related to family impact measures. Additionally, of the 46 studies in this scoping review, only two were qualitative in nature with one mixed-methods study, thus potentially limiting the integration of richer perspectives from a broader range of study designs. While this limitation was beyond our control, it reflected the limited use of qualitative and mixed methods studies on the family implications of SNAP participation. Further, 58% of the articles passed all 5 methodological quality criteria, and an additional 34% satisfied 4 criteria, potentially reflecting a need for deeper empirical methodology in studies addressing family outcomes. Understanding the full impact of SNAP could be gained by employing a broader range of study methodologies.

Conclusion

SNAP is a highly effective program with growing evidence that it positively impacts family health and alleviates poverty. While more research needs to be conducted on the non-food-related impacts of SNAP on family health and poverty, two policy actions resulting from this scoping review deserve attention from policymakers, program administrators, and retail food establishments.

Data Availability

Available upon request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Almada, L., & McCarthy, I. M. (2017). It’s a cruel summer: Household responses to reductions in government nutrition assistance. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 143, 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2017.08.009

Andreyeva, T., Tripp, A. S., & Schwartz, M. B. (2015). Dietary quality of Americans by supplemental nutrition assistance program participation status: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(4), 594–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.035

Arteaga, I., Hodges, L., & Heflin, C. (2021). Giving kids a boost: The positive relationship between frequency of SNAP participation and Infant’s preventative health care utilization. SSM - Population Health, 15, 100910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100910

Austin, A. E., Shanahan, M. E., Frank, M., Naumann, R. B., McNaughton Reyes, H. L., Corbie, G., & Ammerman, A. S. (2023). Association of state expansion of supplemental nutrition assistance program eligibility with rates of child protective services–investigated reports. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 177(3), 294–302. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.5348

Barr, A., & Smith, A. A. (2022). Fighting crime in the cradle: The effects of early childhood access to nutritional assistance. The Journal of Human Resources, 58(1), 43–73. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.58.3.0619-10276R2

Beatty, T. K., Nanney, M. S., & Tuttle, C. (2013). Time to eat? The relationship between food security and food-related time use. Public Health Nutrition, 17(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980012005599

Bensignor, M. O., Freese, R. L., Sherwood, N. E., Berge, J. M., Kunin-Batson, A., Veblen-Mortenson, S., & French, S. A. (2021). The relationship between participation, parent feeding styles, and child eating behaviors. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 10, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2021.1994506

Bergmans, R. S., Berger, L. M., Palta, M., Robert, S. A., Ehrenthal, D. B., & Malecki, K. (2017). Participation in the supplemental nutrition assistance program and maternal depressive symptoms: Moderation by program perception. Social Science & Medicine, 197, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.039

Bethell, C. D., Carle, A., Hudziak, J., Gombojav, N., Powers, K., Wade, R., & Braveman, P. (2017). Methods to assess adverse childhood experiences of children and families: Toward approaches to promote child well-being in policy and practice. Academic Pediatrics, 17(7), S51–S69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.04.161

Bolbocean, C., & Tylavsky, F. A. (2021). The impact of safety net programs on early-life developmental outcomes. Food Policy, 100, 102018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.102018

Breck, A. (2018). Effect of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program on Health and Healthcare Expenditures. Available from Dissertation Abstracts International http://www.pqdtcn.com/thesisDetails/2D2BB2F062A61CAFB7033265C9E5FD18

Bronchetti, E. T., Christensen, G., & Hoynes, H. W. (2019). Local food prices, SNAP purchasing power, and child health. Journal of Health Economics, 68, 102231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2019.102231

Bullinger, L. R., Fleckman, J. M., & Fong, K. (2021). Proximity to SNAP-authorized retailers and child maltreatment reports. Economics and Human Biology, 42, 101015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2021.101015

Carlson, S., & Keith-Jennings, B. (2018). SNAP is linked with improved nutritional outcomes and lower healthcare costs. Targeted News Service. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1988493113

Carr, J. B., & Packham, A. (2020). SNAP schedules and domestic violence. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 40(2), 412–452. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22235

Caswell, J. A., Yaktine, A. L., Committee on Examination of the Adequacy of Food Resources and SNAP Allotments, Food and Nutrition Board, Committee on National Statistics, Institute of Medicine, & National Research Council. (2013). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Examining the Evidence to Define Benefit Adequacy. National Academies Press (US).

Cellini, S. R., McKernan, S., & Ratcliffe, C. (2008). The dynamics of poverty in the United States: A review of data, methods, and findings. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 27(3), 577–605. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20337

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2023). A Closer Look at Who Benefits from SNAP: State-by-State Fact Sheets [Fact sheet]. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/a-closer-look-at-who-benefits-from-snap-state-by-state-fact-sheets#Alabama

Cheng, T. (2010). Financial self-sufficiency or return to welfare? A longitudinal study of mothers among the working poor. International Journal of Social Welfare, 19(2), 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2010.00718.x

Cho, M., & Lightfoot, E. (2022). Recurrence of substantiated maltreatment reports between low-income parents with disabilities and their propensity-score matched sample without disabilities. Child Maltreatment, 28(2), 318–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775595211069917

Choi, J., Wang, D., & Jackson, A. P. (2019). Adverse experiences in early childhood and their longitudinal impact on later behavioral problems of children living in poverty. Child Abuse & Neglect, 98, 104181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104181

Christensen, G., & Bronchetti, E. T. (2020). Local food prices and the purchasing power of SNAP benefits. Food Policy, 95, 101937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101937

Collyer, S., Gandhi, J., Garfinkel, I., Ross, S., Waldfogel, J., & Wimer, C. (2022). The effects of the 2021 monthly child tax credit on child and family well-being: Evidence from New York City. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 8, 237802312211411. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231221141165

Conger, R. D., Ge, X., Elder, G. H., Lorenz, F. O., & Simons, R. L. (1994). Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development, 65(2), 541–561. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131401

Cotti, C. D., Gordanier, J. M., & Ozturk, O. D. (2020). Hunger pains? SNAP timing and emergency room visits. Journal of Health Economics, 71, 102313–102412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2020.102313

Cotti, C., Gordanier, J., & Ozturk, O. (2018). When does it count? The timing of food stamp receipt and educational performance. Economics of Education Review, 66, 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.06.007

Crandall, A., Weiss-Laxer, N. S., Broadbent, E., Holmes, E. K., Magnusson, B. M., Okano, L., Berge, J. M., Barnes, M. D., Hanson, C. L., Jones, B. L., & Novilla, L. B. (2020). The family health scale: Reliability and validity of a short- and long-form. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 587125. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.587125

East, C. (2020). The effect of food stamps on children’s health: Evidence from immigrants’ hanging eligibility. The Journal of Human Resources, 55(2), 387–427. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.55.3.0916-8197r2

Engel, K., & Ruder, E. H. (2020). Fruit and vegetable incentive programs for supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP) participants: A scoping review of program structure. Nutrients, 12(6), 1676. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061676

Engle, P. L., & Black, M. M. (2008). The effect of poverty on child development and educational outcomes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136(1), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1425.023

Ettinger de Cuba, S. A., Bovell-Ammon, A. R., Cook, J. T., Coleman, S. M., Black, M. M., Chilton, M. M., Casey, P. H., Cutts, D. B., Heeren, T. C., Sandel, M. T., Sheward, R., & Frank, D. A. (2019a). SNAP, young children’s health, and family food security and healthcare access. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 57(4), 525–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.027

Ettinger de Cuba, S., Chilton, M., Bovell-Ammon, A., Knowles, M., Coleman, S. M., Black, M. M., Cook, J. T., Cutts, D. B., Casey, P. H., Heeren, T. C., & Frank, D. A. (2019b). Loss of SNAP is associated with food insecurity and poor health in working families with young children. Health Affairs, 38(5), 765–773. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05265

Franckle, R. L., Polacsek, M., Bleich, S. N., Thorndike, A. N., Findling, M. T. G., Moran, A. J., & Rimm, E. B. (2019). Support for supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP) policy alternatives among US adults, 2018. American Journal of Public Health (1971), 109(7), 993–995. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305112

Frank, M. L., & Sato, A. F. (2022). Food insecurity and depressive symptoms among adolescents: Does federal nutrition assistance act as a buffer? Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 44(1), e41–e48. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000001143

Gard, A. M., McLoyd, V. C., Mitchell, C., & Hyde, L. W. (2020). Evaluation of a longitudinal family stress model in a population-based cohort. Social Development (oxford, England), 29(4), 1155–1175. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12446

Gassman-Pines, A., & Schenck-Fontaine, A. (2019). Daily food insufficiency and worry among economically disadvantaged families with young children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81(5), 1269–1284. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12593

Gassman-Pines, A., & Bellows, L. (2018). Food instability and academic achievement: A quasi-experiment using SNAP benefit timing. American Educational Research Journal, 55(5), 897–927. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831218761337

Gennetian, L. A., Seshadri, R., & Hess, N. D. (2016). Supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP) benefit cycles and student disciplinary. Social Service Review, 90(3), 403–433. https://doi.org/10.1086/688074

Good, A., & MacKeith, J. (2021). Assessing family functioning: Psychometric evaluation of the family Star Plus. Family Relations, 70(2), 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12488

Grajek, M., Krupa-Kotara, K., Białek-Dratwa, A., Sobczyk, K., Grot, M., Kowalski, O., & Staśkiewicz, W. (2022). Nutrition and mental health: A review of current knowledge about the impact of diet on mental health. Frontiers in Nutrition (lausanne), 9, 943998. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.943998

Gregory, C. A., & Coleman-Jensen, A. (2013). Do high food prices increase food insecurity in the United States? Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 35(4), 679–707. https://doi.org/10.1093/aepp/ppt024

Gupta, R. P., de Wit, M. L., & McKeown, D. (2007). The impact of poverty on the current and future health status of children. Paediatrics & Child Health, 12(8), 667–672. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/12.8.667

Heflin, C., Hodges, L., & Mueser, P. (2017). Supplemental nutrition assistance program benefits and emergency room visits for hypoglycaemia. Public Health Nutrition, 20(7), 1314–1321. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980016003153

Herman, W. H., Schillinger, D., Bolen, S., Boltri, J. M., Bullock, A., Chong, W., Conlin, P. R., Cook, J. W., Dokun, A., Fukagawa, N., Gonzalvo, J., Greenlee, M. C., Hawkins, M., Idzik, S., Leake, E., Linder, B., Lopata, A. M., Schumacher, P., Shell, D., & Wu, S. (2023). The National Clinical Care Commission report to Congress: recommendations to better leverage federal policies and programs to prevent and control diabetes. Diabetes Care, 46(2), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-1587

Holley, C. E., & Mason, C. (2019). A systematic review of the evaluation of interventions to tackle children’s food insecurity. Current Nutrition Reports, 8(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-019-0258-1

Hong, J. S., Choi, J., Espelage, D. L., Wu, C., Boraggina-Ballard, L., & Fisher, B. W. (2020). Are children of welfare recipients at a heightened risk of bullying and peer victimization? Child & Youth Care Forum, 50(3), 547–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-020-09587-w

Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

Hong, Y. S., & Henly, J. R. (2020). Supplemental nutrition assistance program and school readiness skills. Children and Youth Services Review, 114, 105034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105034

Hoynes, H. W., & Schanzenbach, D. W. (2012). Work incentives and the food stamp program. Journal of Public Economics, 96(1), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2011.08.006

Hoynes, H. W., Schanzenbach, D. W., & Almond, D. (2016). Long-run impacts of childhood access to the safety net. The American Economic Review, 106(4), 903–934. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20130375

Hudak, K. M., & Racine, E. F. (2019). The supplemental nutrition assistance program and child weight status: A review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 56(6), 882–893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.01.006

Johnson-Motoyama, M., Ginther, D. K., Oslund, P., Jorgenson, L., Chung, Y., Phillips, R., Beer, O. W. J., Davis, S., & Sattler, P. L. (2022). Association between state supplemental nutrition assistance program policies, child protective services involvement, and foster care in the US, 2004–2016. JAMA Network Open, 5(7), e2221509. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.21509

Karpman, M., Hahn, H., & Gangopadhyaya, A. (2019). Precarious work schedules could jeopardize access to safety net programs targeted by work requirements.Washington, DC: Urban Institute. https://search.proquest.com/docview/2250577999

Kim, J. (2016). Do SNAP participants expand non-food spending when they receive more SNAP benefits?—Evidence from the 2009 SNAP benefits increase. Food Policy, 65, 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.10.002

Kinsey, E. W., Oberle, M., Dupuis, R., Cannuscio, C. C., & Hillier, A. (2019). Food and financial coping strategies during the monthly supplemental nutrition assistance program cycle. SSM - Population Health, 7, 100393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100393

Laurito, A., & Schwartz, A. E. (2019). Does school lunch fill the “SNAP Gap” at the end of the month? Southern Economic Journal, 86(1), 49–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/soej.12370

Lee, K., & Zhang, L. (2022). Cumulative effects of poverty on children’s social-emotional development: Absolute poverty and relative poverty. Community Mental Health Journal, 58(5), 930–943. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-021-00901-x

Lee, Y., Mozaffarian, D., Sy, S., Huang, Y., Liu, J., Wilde, P. E., Abrahams-Gessel, S., Jardim, Td. S. V., Gaziano, T. A., & Micha, R. (2019). Cost-effectiveness of financial incentives for improving diet and health through medicare and medicaid: A microsimulation study. PLoS Medicine, 16(3), e1002761. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002761

Liu, Y., & Eicher-Miller, H. A. (2021). Food insecurity and cardiovascular disease risk. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 23(6), 24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-021-00923-6

Lupien, S. J., King, S., Meaney, M. J., & McEwen, B. S. (2000). Child’s stress hormone levels correlate with mother’s socioeconomic status and depressive state. Biological Psychiatry, 48(10), 976–980. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00965-3

Mabli, J., & Worthington, J. (2017). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation and emergency food pantry use. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 49(8), 647-656.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2016.12.001

Maguire-Jack, K., Johnson-Motoyama, M., & Parmenter, S. (2022). A scoping review of economic supports for working parents: The relationship of TANF, child care subsidy, SNAP, and EITC to child maltreatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 65, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2021.101639

Mande, J., & Flaherty, G. (2023). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program as a health intervention. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 35(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000001192

McKernan, S., Ratcliffe, C., & Braga, B. (2021). The effect of the US safety net on material hardship over two decades. Journal of Public Economics, 197, 104403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104403

Miller, D. P., & Morrissey, T. W. (2021). SNAP participation and the health and health care utilisation of low-income adults and children. Public Health Nutrition, 24(18), 6543–6554. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021003815

Millett, L., Lanier, P., & Drake, B. (2011). Are economic trends associated with child maltreatment? Preliminary results from the recent recession using state level data. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(7), 1280–1287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.03.001

Morris, M. C., Marco, M., Maguire-Jack, K., Kouros, C. D., Im, W., White, C., Bailey, B., Rao, U., & Garber, J. (2019). County-level socioeconomic and crime risk factors for substantiated child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 90, 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.02.004

Morrissey, T. W., & Miller, D. P. (2020). Supplemental nutrition assistance program participation improves children’s health care cse: An analysis of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act’s natural experiment. Academic Pediatrics, 20(6), 863–870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2019.11.009

Munger, A. L., Hofferth, S. L., & Grutzmacher, S. K. (2016). The role of the supplemental nutrition assistance program in the relationship between food insecurity and probability of maternal depression. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 11(2), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2015.1045672

Neuert, H., Fischer, E., Darling, M., & Barrows, A. (2019). Work Requirements Don’t Work: A Behavioral Science Perspective. Ideas, 42. http://www.ideas42.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/ideas42-Work-Requirements-Paper.pdf

Nieves, C., Dannefer, R., Zamula, A., Sacks, R., Ballesteros Gonzalez, D., & Zhao, F. (2022). “Come with us for a week, for a month, and see how much food lasts for you:” A Qualitative Exploration of Food Insecurity in East Harlem, New York City. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 122(3), 555–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2021.08.100

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 178–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.001

Parolin, Z. (2021). Income support policies and the rise of student and family homelessness. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 693(1), 46–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716220981847

Powell, T. W., Wallace, M., Zelaya, C., Davey-Rothwell, M. A., Knowlton, A. R., & Latkin, C. A. (2018). Predicting household residency among youth from vulnerable families. Children and Youth Services Review, 93, 226–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.012

Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000660

Pryor, L., Melchior, M., Avendano, M., & Surkan, P. J. (2023). Childhood food insecurity, mental distress in young adulthood and the supplemental nutrition assistance program. Preventive Medicine, 168, 107409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107409

Rogers, S., Garg, A., Tripodis, Y., Brochier, A., Messmer, E., Gordon Wexler, M., & Peltz, A. (2022). Supplemental nutrition assistance program participation and health care expenditures in children. BMC Pediatrics, 22(1), 155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03188-3

Rothbart, M. W., & Heflin, C. (2023). Inequality in literacy skills at kindergarten entry at the intersections of social programs and race. Children and Youth Services Review, 145, 106812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2023.106812

Ryan-Ibarra, S., DeLisio, A., Bang, H., Adedokun, O., Bhargava, V., Franck, K., Funderburk, K., Lee, J. S., Parmer, S., & Sneed, C. (2020). The US supplemental nutrition assistance program—education improves nutrition-related behaviors. Journal of Nutritional Science (Cambridge), 9, 44. https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2020.37

Schenck-Fontaine, A., Gassman-Pines, A., & Hill, Z. (2017). Use of informal safety nets during the supplemental nutrition assistance program benefit cycle: How poor families cope with within-month economic instability. Social Service Review, 91(3), 456–487. https://doi.org/10.1086/694091

Serchen, J., Atiq, O., & Hilden, D. (2022). Strengthening food and nutrition security to promote public health in the United States: A position paper from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 175(8), 1170–1171. https://doi.org/10.7326/M22-0390

Shaefer, H. L., & Gutierrez, I. A. (2013). The supplemental nutrition assistance program and material hardships among low-income households with children. The Social Service Review (chicago), 87(4), 753–779. https://doi.org/10.1086/673999

Shankar, P., Chung, R., & Frank, D. A. (2017). Association of food insecurity with children’s behavioral, emotional, and academic outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics : JDBP, 38(2), 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000383

Sonik, R. A. (2016). Massachusetts inpatient medicaid cost response to increased supplemental nutrition assistance program benefits. American Journal of Public Health (1971), 106(3), 443–448. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302990

Steimle, S., Gassman-Pines, A., Johnson, A. D., Hines, C. T., & Ryan, R. M. (2021). Understanding patterns of food insecurity and family well-being amid the COVID-19 pandemic using daily surveys. Child Development, 92(5), e781–e797. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13659

Thorndike, A. N., Gardner, C. D., Kendrick, K. B., Seligman, H. K., Yaroch, A. L., Gomes, A. V., Ivy, K. N., Scarmo, S., Cotwright, C. J., & Schwartz, M. B. (2022). Strengthening US food policies and programs to promote equity in nutrition security: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 145(24), e1077–e1093. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001072

Vartanian, T. P., Houser, L., & Harkness, J. (2011). Food stamps and dependency: disentangling the short-term and long-term economic effects of food stamp receipt and low income for young mothers. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 38(4), 101–122. https://doi.org/10.15453/0191-5096.3633

Verghese, A., Raber, M., & Sharma, S. (2019). Interventions targeting diet quality of supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP) participants: A scoping review. Preventive Medicine, 119, 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.12.006

Wagmiller, R. L., & Adelman, R. M. (2009). Childhood and intergenerational poverty: the long-term consequences of growing up poor. National Center for Children in Poverty. https://doi.org/10.7916/d8mp5c0z

Wang, J. S., Zhao, X., & Nam, J. (2020). The effects of welfare participation on parenting stress and parental engagement using an instrumental variables approach: Evidence from the supplemental nutrition assistance program. Children and Youth Services Review, 121, 105845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105845

Weinstein, O., Cordeiro, L. S., Ronnenberg, A., Sartori, A., Anderson, A. L. W., & Nelson-Peterman, J. (2018). What works when it comes to having enough: A qualitative analysis of SNAP-participants’ food acquisition strategies. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 14(5), 613–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2018.1545621

Xu, Y., Jedwab, M., Soto-Ramírez, N., Levkoff, S. E., & Wu, Q. (2021). Material hardship and child neglect risk amidst COVID-19 in grandparent-headed kinship families: The role of financial assistance. Child Abuse & Neglect, 121, 105258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105258

Yoshikawa, H., Aber, J. L., & Beardslee, W. R. (2012). The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth. The American Psychologist, 67(4), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028015

Funding

Funding was supported by the Department of Public Health at Brigham Young University to support wages.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RWE: team lead, data collection, performed analysis, manuscript writing; ZPM: data collection, performed analysis, manuscript writing; GMS: data collection, performed analysis, manuscript writing; AMB: data collection, performed analysis, manuscript writing; MCG: conceived and designed the analysis, manuscript writing; MLBN: co-conceived and designed the analysis, manuscript writing; MEF: manuscript writing; MDB: conceived the project, co-conceived and designed the analysis, manuscript writing, wrote the funding proposal for the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Not applicable.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Evans, R.W., Maguet, Z.P., Stratford, G.M. et al. Investigating the Poverty-Reducing Effects of SNAP on Non-nutritional Family Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Matern Child Health J 28, 438–469 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-024-03898-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-024-03898-3