Abstract

Purpose of Review

To synthesise the research which has sought to evaluate interventions aiming to tackle children’s food insecurity and the contribution of this research to evidencing the effectiveness of such interventions.

Recent Findings

The majority of studies in this review were quantitative, non-randomised studies, including cohort studies. Issues with non-complete outcome data, measurement of duration of participation in interventions, and accounting for confounds are common in these evaluation studies. Despite the limitations of the current evidence base, the papers that were reviewed provide evidence for multiple positive outcomes for children participating in attended and subsidy interventions, inter alia, reductions in food insecurity, poor health and obesity. However, current evaluations may overlook key areas of impact of these interventions on the lives and outcomes of participating children.

Summary

This review suggests that the current evidence base which evaluates food insecurity interventions for children is both mixed and limited in scope and quality. In particular, the outcomes measured are narrow, and many papers have methodological limitations. With this in mind, a systems-based approach to both implementation and evaluation of food poverty interventions is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Food insecurity is defined as “limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways (e.g. without resorting to emergency food supplies, scavenging, stealing or other coping strategies)” [1]. Despite experiencing relative wealth as nations, food insecurity is an increasingly common phenomenon in some developed countries. Recent statistics indicate that in 2016, 12.3% of households and 8% of children in America experienced food insecurity [2]. Similarly, 19% of UK children under 15 live with a respondent who is moderately or severely food insecure and 10% live with a respondent who is severely food insecure [3]. Whilst there is no current data on levels of children’s food insecurity in the UK, eligibility for free school meals (which is based upon low household income) can be used as a proxy measure. In 2018, 13.6% of UK school children were eligible for free school meals [4], suggesting that food insecurity may also be a significant issue among UK children.

It is well-evidenced that food insecurity results in a restricted and less nutritionally adequate diet [5]. This has health implications, as children who experience food insecurity are likely to have poorer general health, approximately twice as likely to have asthma and almost three times as likely to have iron deficiency anaemia than food-secure children [6,7,8]. Children who experience food insufficiency are also significantly more likely to exhibit behavioural problems, have difficulty getting on with other children [9] and experience anxiety and depression [9, 10]. Moreover, in 2015, only 33.1% of UK school children eligible for free school meals achieved the key attainment indicator at the end of secondary school, compared to 60.9% of more food-secure school children [11].

The evidence base described provides a compelling case for interventions that seek to tackle children’s food insecurity, in order to minimise the health and social disparities between children who experience food insecurity and those who do not.Footnote 1 These interventions take multiple formats; from attended interventions (e.g. school food assistance and holiday clubs) to providing disadvantaged families with subsidies (e.g. the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP). However, there is currently a lack of synthesis of the evidence base which examines the effectiveness of these interventions, particularly regarding the ways in which effectiveness is evaluated.

To our knowledge, two systematic reviews of interventions to tackle children’s food insecurity have been published to date. One is a rapid review recently published which only included interventions in the form of charitable breakfast clubs and holiday hunger projects in the UK [12••]. The other is a recent rapid review funded by the NIHR which explores the nature, extent and consequences of food insecurity among children [13]. However, this review focused on quantitative outcomes of interventions where the food insecurity status of the sample has been measured and, therefore, only includes a very targeted and limited number of studies. With this in mind, the current review sought to produce a systematic review of the literature on interventions from developed countries which seek to tackle children’s food insecurity, to gain a clear picture of the following: (1) the ways in which food insecurity interventions are evaluated; and the quality of this evaluation and (2) the evidence base of the impact of these interventions, in terms of positive outcomes for the targeted children.

Methods

Search Strategy

Online searches were conducted using three databases to ensure that the full breadth of relevant publications was identified. These databases were PsycINFO, Medline and Scopus. Key terms relating to food insecurity interventions were used to identify a pool of potentially relevant papers for this review. These key words were the following: child* adolescent* “young people” “youth” “intervention” “holiday club” combined using the Boolean operator AND with any of the following words: “food insecurity” OR “food poverty” OR “food insufficiency” OR “holiday hunger”. Relevant articles were detected up until July 2018.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in this review, papers were required to evaluate interventions that seek to tackle food insecurity and to measure the outcomes specifically for children. Studies were also required to take place in a developed country as defined by the United Nations [14] and to be published in a peer-reviewed journal. Papers were excluded if they only measured children’s uptake of an intervention (e.g. a process evaluation) or if the outcome measures referred to households or families rather than children. They were also excluded if they were not published in English.

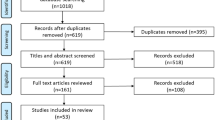

Identification of Relevant Papers

The process for identification of relevant papers can be seen in Fig. 1. The first author screened the titles of all the search results to identify potentially relevant papers. When a title was deemed relevant (or when relevance was ambiguous), the abstract was screened for eligibility to assess whether the paper met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full text was then read for all papers which either (a) met these criteria or (b) did not contain sufficient detail in the abstract to assess eligibility.

Data Extraction

Data was extracted by the first author from 42 papers that met the eligibility criteria for this review. Data extracted was standardised across studies using a form specifically developed to meet the aims of this review. Extracted data included author(s), date and place of publication, country of study, study aim(s), type of intervention, target population of intervention, method of evaluation and the findings pertaining to child outcomes of the intervention(s). A summary of this data can be seen in Tables 1 and 2 for attended (in person) and subsidy-based interventions respectively.Footnote 2

Quality Assessment

The first author performed an assessment of the quality of the final papers included in this review using the latest version of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [15]. This tool provides five questions to assess the quality of studies with qualitative, quantitative or mixed methodologies. In line with the creating authors’ guidance, scores for individual papers were not calculated. Instead, analysis was undertaken on the quality of the included papers collectively.

Results

The 42 papers included in this review were published between 2002 and 2018 and reported on studies conducted in the USA (n = 34), UK (n = 4), Australia (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), Greece (n = 1) and New Zealand (n = 1). The interventions took multiple formats that can be categorised into two groups, attended (in-person) interventions and subsidy interventions. First, the ways in which these papers evaluate food insecurity interventions are explored, as well as the quality of these papers. Next, the evidence base, as described in these papers, of the outcomes of these interventions for participating children is discussed.

The Kinds of Evaluation of Food Insecurity Interventions Taking Place

Interventions captured in this review adopt different approaches that aim to tackle separate aspects of food insecurity in order to achieve particular positive outcomes for children, and this, therefore, informs the kind of evaluation which takes place. For example, school-based interventions that typically aim to tackle children not accessing an adequate breakfast or lunch and then examine the impact on children in the classroom (e.g. behaviour, educational achievement). Interventions that attempt to increase consumption of fruit and vegetables measure effectiveness in terms of achieving this aim, whilst ignoring any potential wider impacts that may impact positively (or negatively) on children’s outcomes.

The research methods used in the papers included in this review are listed in Tables 1 and 2. There is a paucity of large-scale RCTs to investigate the effectiveness of interventions for tackling children’s food insecurity, and for ethical reasons (such as withholding an intervention from individuals who it is believed would benefit), this would be difficult to overcome. Several studies captured in this review utilise cohort data to overcome these ethical issues. Whilst this allows comparison between participants and other individuals of a similar demographic, there are other methodological limitations of this approach. For example, as described in Dunifon and Kowaleski-Jones’ evaluation of the Nation School Lunch Program (NSLP), differences in outcomes between eligible children who do and do not participate in interventions may well be driven by unmeasured factors and selection bias [16]. To attenuate the issue of selection bias, as well as issues of identification (where it is not always possible to assess participation), the cohort studies included in this review, particularly those which explore relationships between subsidy intervention participation and children’s food insecurity and obesity, have used a range of statistical methods [16,16,17,19]. However, there is a lack of consensus as to which of these statistical methods is most appropriate for overcoming issues of bias within data, and this makes it difficult to assess the robustness of findings reported in these papers.

Several of the studies detected by this review are experimental studies that provide valuable quantitative results on the outcomes of the interventions seeking to tackle children’s food insecurity. However, these are often small-scale, with only parent-report/self-report measures of outcomes, such as dietary intake [20,20,21,23].

When considering the quantitative articles in this review as a whole, it is apparent that there is a lack of longitudinal analyses which can better unpack the causality of relationships between intervention participation and outcomes for children. The studies presented provide the beginning of an understanding of the possible benefits for children participating in food insecurity interventions. However, large-scale longitudinal studies which allow assessment of long-term outcomes and remove the potential confounds associated with group comparisons are strongly needed.

Qualitative studies have been conducted to gain service-user perspectives on food insecurity interventions and the positive benefits for children [24, 25, 26•, 27]. Whilst these studies play an important role in evaluating these interventions, those captured in this review have predominantly utilised parents and stakeholders as participants, whereas children’s voice is only included in a small proportion of these studies. In light of this, future research should seek to ensure that the voices of participating children and young people are included in evaluation work, as those best placed to report their own experiences [28].

Quality Assessment

Utilising the MMAT (2018) revealed that there was variation between the attended and subsidy interventions in the quality of the studies that were undertaken. For each of the groups, 24 papers were reviewed in total. It is important to note that as the methods varied for the studies, the quality criteria also varied across the studies. However, examining the number of papers that met all five criteria associated with the particular study design is useful as a way of exploring the overall quality of the evidence base. For the subsidy programmes, 95% of the papers met at least three of the quality criteria whilst a smaller number met the third (58%) and fourth (50%) quality criteria. For the attended programmes, there was less divergence and more consistency across studies in meeting the quality criteria (criteria 1 = 75%, criteria 2 = 71%, criteria 3 = 83%, criteria 4 = 63%, criteria 5 = 79%.)

The majority of the studies (n = 32, 76%) were quantitative non-randomised studies defined as any quantitative studies estimating the effectiveness of an intervention or studying other exposures that do not use randomisation to allocate units to comparison groups [29]. Of these studies, the majority involved participants that were representative of the target population (91%); used appropriate measurements regarding both the outcome and intervention (96%); and involved interventions that were administered as intended (91%). However, only 70% provided complete outcome data (with very few measuring duration or level of participation in the intervention), and only 52% accounted for confounders in the design and analysis. Of the remaining studies, three were qualitative, five were quantitative randomised controlled trials and 2 were mixed-methods. Whilst RCTs are the gold standard of intervention evaluation, those captured in this review were typically of poor quality (meeting a maximum of three criteria), with inadequate reporting or implementation of randomisation, a lack of information of blinding of the experimenters and some issues with baseline group differences. This overview indicates that designing a high-quality study that meets all quality criteria on this topic is challenging.

The Evidence for Positive Outcomes for Children Targeted by Food Insecurity Interventions

Attended Interventions

Twenty-four papers included in this review related to attended interventions, including school food assistance (breakfast and lunch provision; n = 13), holiday clubs (n = 3), interventions including nutrition education (n = 7) and gardening clubs (n = 1). A summary of these papers can be found in Table 1.

School Food Assistance

Four papers assessed the impact of school food assistance (as a group of interventions) on children. It was found that US school food assistance can significantly improve educational difficulties, where the relationship between household food insecurity and educational difficulties disappears for children who participate [30]. It has also been found that food-insecure girls participating in the US’s School Breakfast Program (SBP), National School Lunch Program (NSLP) or Food Stamp Program (FSP—or all three) have a reduced risk of obesity compared to non-participating food-insecure girls. However, there was no effect of participation on risk of obesity for boys [31]. Moreover, participation in US school meals alongside WIC (Women, Infants and Children) and/or SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) has been associated with increased risk of obesity for food-secure children, but not for food-insecure children [32]. Lastly, evidence has been found that school-based food assistance can reduce the odds of children experiencing food insecurity among high-risk (border colonias) populations [33].

Five papers evaluated the impact of school breakfast interventions on children’s outcomes, with US studies finding that they can reduce the disparity in breakfast consumption between food-secure and food-insecure children and reduce children’s food insecurityFootnote 3 [34, 35]. UK stakeholders also perceive benefits of universal free school breakfast, including alleviating hunger and improving health outcomes, as well as providing social, behavioural and educational benefits [25]. Whilst one paper reported that UK stakeholders have concerns about universal free school breakfast increasing obesity [25], no associations between participation in US breakfast in the classroom and obesity have been found [36]. Research has failed to find evidence of gains in academic performance in relation to breakfast in the classroom in the US [36]. However, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of UK school breakfast provision reported that post-intervention, participating children demonstrated significantly improved concentration, skipped fewer classes and ate fruit for breakfast more when compared to control children [37•]. Post-intervention, participating primary school children had higher rates of borderline/abnormal conduct and behavioural difficulties compared to the control group, and participating secondary school children more frequently had borderline/abnormal prosocial scores than the control group. However, these findings were not supported by all analyses, and a lack of baseline assessment prevents conclusions being drawn from these findings[37•].

Four papers evaluated the effects of participating in school lunch interventions. Participation in the US NSLP has been associated with increased odds of hunger [33], a health limitation, and lower maths test scores, as well as increased odds of externalising behaviour [16]. However, when comparing outcomes of siblings, one of whom does not participate in the NSLP, there are no associations of NSLP participation with negative child outcomes, suggesting that these increased odds may be a product of familial factors not controlled for elsewhere [16]. A further paper evaluated the impact of the NSLP, whilst controlling for methodological issues, such as participants self-selecting to participate in the NSLP (which has been suggested as an explanation for the positive relationship of participation with poor health), and using comparison groups of participants who were ineligible for the intervention [17]. Using this approach suggests that the NSLP reduces incidences of poor health and obesity. Other research has also explored whether the relationship between BMI and obesity is modified by participation in the NSLP [38]. However, no significant relationship between household food insecurity and child BMI was found among NSLP participants or non-participants.

Holiday Clubs

Three qualitative papers were detected which evaluated summer holiday clubs that offer free food alongside other enrichment activities, such as physical activity, stories and crafts. Both staff and attendees at UK holiday breakfast clubs and other holiday clubs report nutritional (e.g. more substantial and varied breakfast, trying new foods, attenuating hunger), social (e.g. removing social isolation and providing new interactions) and financial benefits to attending these clubs [26•, 27]. Lastly, parent attendees of a US lunch in the library scheme described that the intervention allowed their children to socialise, and they valued the other enrichment opportunities this intervention provided [24].

Nutrition Education

Six papers reported outcomes for children who had participated in food insecurity interventions involving nutrition education, with two finding no significant effects. One such paper explored the addition of six sessions of nutrition education to the Kid’s Café Program, a free meal initiative in the US, using an RCT [22]. No significant effect was found in the intervention on children’s vegetable consumption, and intervention children had significantly higher sodium intake post-intervention than control children. However, it should be noted that the authors report that there were issues with the acceptability of nutrition education classes. Another experimental paper assessed an intervention in New Zealand which offered nutrition education, fruit and vegetable tasting and encouraged growing and cooking vegetables and other healthy meals [21]. No significant effect of intervention was found on nutrient intake, but children consumed significantly fewer highly processed snack foods post-intervention. There were increases in fruit and vegetable consumption at 6 months post-intervention, but significance could not be tested due to drop out rates.

Four papers reported positive outcomes of nutrition education food insecurity interventions. A small-scale experimental study explored the effects of the Food and Fun intervention, an eight-week curriculum of nutrition education alongside education about physical activity, tasting healthy foods, free meals and physical activity [23]. The authors report that children’s fruit and vegetable consumption, as well as their levels of physical activity, significantly increased after the intervention. A similar intervention has also been implemented among sheltered homeless children, called Cooking, Healthy Eating, Fitness and Fun (CHEFF). A qualitative study found that child attendees showed some increased willingness to try different foods, developed increased liking of new foods and intentions to change health behaviours [39]. The Brighter Bites intervention in the US also has a nutrition education component, which is delivered alongside provision of free fresh produce which is redirected from food waste [40]. Parents reported that their child’s intake of fresh produce increased after participating, with most reporting that the nutrition education component was effective. Similarly, nutrition education has been integrated into a free-school meal intervention in low SES schools in parts of Greece [41]. Here, provision of a free meal, education about a healthy diet and physical activity, as well as cooking demonstrations for parents, resulted in significant increases in consumption of multiple healthful foods, and some movement towards a Mediterranean diet pattern, which is suggested to have health benefits.

Nutrition education has also been added in to subsidy interventions that seek to tackle food poverty, such as the US Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP-Ed). One paper evaluated the long-term effects of SNAP-Ed participation on children’s food insecurity in an RCT [42]. It was found that there was no significant change in children’s food insecurity status in comparison to a control group who received SNAP benefits alone. The authors highlight that it is likely that children are buffered from the main effects of household food insecurity (which was lowered by the intervention) and that children’s food insecurity was low in the sample at baseline.

Community Gardening

One paper explored the utility of a community gardening intervention for increasing vegetable intake and reducing food insecurity among child attendees. After participation, the number of children consuming vegetables several times a day increased substantially, but there was no significant change in the number of meals children missed [20].

Subsidy Interventions

Twenty-three papers identified in this review explored the impact of subsidy interventions on children’s outcomes. These included papers evaluating the Women, Infants and Children intervention (n = 4), SNAP (previously known as the Food Stamp Program; FSP) (n = 14), and other subsidy interventions (n = 6). A summary of these papers can be found in Table 2.

Women, Infants and Children

WIC is a short-term multi-faceted US intervention that seeks to alleviate nutritional risk among low-income women, infants and children in order to protect their health. It does this by providing nutritious foods, information on healthy eating and referrals to additional healthcare (including immunisation and screening) [43]. Four papers evaluated the possible effects of WIC on children, with the first suggesting that WIC reduces the prevalence of child food insecurity [44]. Further research has found that among WIC eligible infants, claimers had a significantly lower probability of being underweight, short or being rated as having poorer health than infants not claimed for due to access issues [45]. This, combined with the fact that infants of WIC claimants were of comparable weight and length to national averages, suggests that WIC may well attenuate nutritional and growth deficits among participants. Indeed, a further study found that WIC participation attenuates child health risks associated with family stressors, with WIC participants having higher odds of well child status and lower odds of poorer health status and overweight compared to eligible non-participants [46]. Lastly, WIC participation (along with SNAP and free school meals) has been associated with increased BMI and waist circumference for food-secure but not food-insecure children [32].

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

SNAP is a US intervention that provides food-purchasing assistance to low-income families and individuals [43]. The outcomes of SNAP participation for children were assessed in 14 papers included in this review, making it the most extensively evaluated intervention captured. In terms of educational attainment, participation has been found to improve girls’ mathematics and reading scores [47] and moderate the negative relationship between deprivation and children’s grade attainment [48]. In terms of health outcomes, the evidence suggests that participation reduces poor health among food-insecure children [7, 18].

Evidence as to whether SNAP participation affects weight status or decreases children’s food insecurity is mixed. For example, when operating under the name the “Food Stamp Program” (FSP), participation over a five-year period was associated with decreased odds of overweight among young boys and increased odds among young girls, with no associations found for older children [49]. However, the authors acknowledge that food insecurity was not controlled for in these analyses. In other research, FSP participation has been associated with a reduced risk of overweight among food-insecure girls compared to non-participating food-insecure girls, although no significant effects were found for boys [31], and SNAP participation (along with WIC and free school meals) has been associated with increased BMI and waist circumference for food-secure but not food-insecure children [32]. Moreover, whilst one study found that, when controlling for financial stress, participation decreases both weight status and severity of overweight among children [50], a further study (which did not control for financial stress) found no relationship between food insecurity and BMI among SNAP users or non-users [38].

Findings on the effects of SNAP participation on children’s food insecurity are also mixed. Some studies have suggested that participation in SNAP is associated with decreased odds of child food insecurity among a general US population and border colonias [18, 51, 52], as well as the proportion of children not eating enough [53]. However, one study reports that there is no relationship between SNAP participation and children’s food insecurity [54] whilst a second reports that although SNAP participation reduces household food insecurity, it increases food insecurity among children [55].

Other Subsidy Interventions

A similar intervention to WIC is the Keeping Infants Nourished and Developing (KIND) intervention. KIND is a collaboration between primary care physicians and a food bank, providing supplementary infant formula, educational materials, and clinic and community resources. KIND intervention infants were more likely to complete a full set of well-infant healthcare visits than non-users, but there was no significant difference in weight-for-length between users and non-users [56], suggesting possible attenuation of nutritional deficits.

Two papers included in this review evaluated the Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer for Children (SEBTC), which is an extension of the standard SNAP provision. This intervention provides eligible families with an additional $60 per eligible child each month during the summer, when demands on family finances are greater. These papers reported significantly lower levels of food insecurity among randomly allocated participants, compared to a control group, as well as moderate improvements in children’s fruit, vegetable and dairy consumption [57, 58].

The Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) is an American intervention that reimburses child care providers for meals and snacks consumed. One study in this review explored relationships between CACFP participation and overweight status, food consumption and food insecurity [59]. It was found that participation may reduce the prevalence of overweight among low-income children (although the authors highlight the detected effect was too small to be of note) and moderately increases consumption of vegetables and milk.

Another subsidy intervention detected in this review is the Individual Development Account (IDA) savings programme, which matches every USD saved with further two. It also provides financial education and training on budgeting and credit repair and other asset-specific training. The research presented in this review found no significant difference in children’s food insecurity between those newly enrolled on the programme and those who had graduated from the programme [60].

The final subsidy intervention detected in this review was a community-supported agriculture intervention, where low-income families can purchase a share of a farmer’s harvest at a 50% discount and then receive deliveries of fresh fruit and vegetables throughout the season. Whilst participating children had higher fruit and vegetable intake than the national average and were more likely to meet recommendations for consumption, there was no significant difference in consumption between the summer and winter when they were not receiving fresh produce [61]. Therefore, the study does not evidence a positive effect of the intervention on consumption, instead it is likely that those who chose to participate had higher consumption of fruit and vegetable consumption.

Discussion

This review has examined the existing evidence base pertaining to interventions that have attempted to address children’s food insecurity. The review has highlighted that the existing evidence base about what works in terms tackling children’s food insecurity and the resultant potential for delivering positive impacts for children is problematic due to issues including the following: interventions having ill-defined aims; a lack of robust evaluation approaches; a lack of consistency in measures (both in terms of food insecurity and intervention outcomes); measurement of a restricted outcome or outcomes; and a lack of explanatory value. There is also considerable variation in the methods utilised to evidence the effectiveness of the interventions as some claim a broad range of positive outcomes which are measured qualitatively (e.g. self-reports) whilst other interventions are evaluated using very narrow criteria (e.g. vegetable consumption, number of healthcare visits) rather than examining the broader impact on the family in the long term. This supports concerns raised in other literature, where concepts like food insecurity are used too narrowly, with too strong a focus on outcomes of food quantity or nutrient intake [12••]. There is a lack of robust evidence of outcomes, such as that derived from RCTs. However, as outlined elsewhere, conducting such research has numerous methodological issues, particularly when related to public health interventions where implementation is rapid [37•, 62].

Several of the papers reported in this review seek to evaluate the impact of interventions on children’s food insecurity. However, food insecurity is a multi-faceted construct, with implications for food quality, variety and quantity [1]. Furthermore, there is no one internationally agreed measure of food insecurity. For example, the US government routinely collect data on food insecurity using the United States Department for Agriculture Food Security Scale, with possible outcomes ranging from high to marginal, low and very low food security. Meanwhile, the UK government does not collect such data or have an agreed standardised measure in place. Consistent measurement of food insecurity is needed not only to assess the scale and nature of the issue but also to allow robust development of interventions to address food insecurity.

Additionally, there is considerable variation in the design of interventions, with some designed to alleviate food insecurity, whilst others are designed to tackle issues that are (assumed) consequences of food insecurity and food scarcity (e.g. increasing consumption of fruit and vegetables, developing food confidence, providing nutritional education). Moreover, whilst attended interventions, such as holiday clubs, are increasingly prevalent, this review has found that they can be poorly described with very limited evaluation, and there is a paucity of comprehensive data on how, where and with whom these interventions are implemented [12••]. Typically, the interventions represented in this review lack a clear theory of change which outlines how and why the intervention might deliver the intended outcomes [63, 64]. It is therefore recommended that firstly, future research seeks to more demonstrate that interventions impact food insecurity. Secondly, plans for interventions must outline how and why the intervention will alleviate food insecurity, and therefore achieve the resultant impacts. Having done this, it will then be possible to identify how reduced food insecurity impacts on delivering particular positive outcomes for children.

The review has also revealed that there are two main strategies that have been adopted in attempts to address children’s food insecurity, which are described here as attended and subsidy interventions. These two strategies provide different possibilities for supporting families experiencing food insecurity which are also important to note. Subsidy programmes provide families with more flexibility to make decisions about how the additional resources they are provided with can best be utilised within individual families, but they have the disadvantage of potentially further stigmatising families who are defined by their low socio-economic status [65]. In contrast, the attended programmes can be devised in ways where children access support in spaces and places that they already attend (e.g. school) as universal provision which reduces the risk of children being further stigmatised [26•]. Whilst it appears that both these strategies may result in positive outcomes, it is not clear the extent to which families experiencing food insecurity are influencing the design of the interventions that they are the beneficiaries of. The disadvantage of this approach is that families do not have the opportunity to ensure that interventions best meet their complex needs in a holistic manner. Another recommendation arising from this review is therefore that systems-based approaches to tackling food insecurity are needed if real change is to be both delivered and evidenced in the long term.

Conclusions

In summary, this review has synthesised the research that evaluates interventions to tackle children’s food insecurity and found this evidence base to be both mixed and lacking in robustness. In order to promote effective interventions to tackle children’s food insecurity, interventions should be grounded in theory of change and take a systems-based approach to both implementation and evaluation of these interventions. To do this, measurement of food insecurity must be standardised and universally implemented, ensuring that such interventions are meeting their primary aim as well as the broad variety of other positive outcomes such interventions have the potential to achieve.

Change history

04 March 2019

The original version of this article unfortunately contained mistakes in Tables captions.

Notes

It is noted that children can move in and out of these binary groupings and may do so several times across their childhood.

This paper reports outcomes in terms of changes in low and very low food security as measured by the USDA Food Security Scales. For consistency and ease of interpretation, findings that have been anchored in relation to changes in food security have been used throughout this review.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Taylor A, Loopstra A. Too poor to eat: food insecurity in the UK, London; 2016.

United States Department of Agriculture: Economic Research Service. Food security in the US: key statistics and graphics; 2017. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/key-statistics-graphics.aspx#children.

The Food Foundation. In: New evid. child food insecurity UK; 2017. https://foodfoundation.org.uk/new-evidence-of-child-food-insecurity-in-the-uk/.

Department for Education. Schools, pupils and their characteristics: January 2018; 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/719226/Schools_Pupils_and_their_Characteristics_2018_Main_Text.pdf. Accessed 16 Aug 2018.

Molcho M, Gabhainn S, Kelly C. Food poverty and health among schoolchildren in Ireland: findings from the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:364–70.

Eicher-Miller H, Mason A, Weaver C, Boushey CJ. Food insecurity is associated with iron deficiency anemia in US adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1358–71.

Cook JT, Frank DA, Levenson SM, Neault NB, Heeren TC, Black MM, et al. Child food insecurity increases risks posed by household food insecurity to young children’s health. J Nutr. 2006;136:1073–6.

Kirkpatrick SI, McIntyre L, Potestio ML. Child hunger and long-term adverse consequences for health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:754–62.

Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA Jr. Food insufficiency and American school-aged children’s cognitive, academic, and psychosocial development. Pediatrics. 2001;108:44–53.

Melchior M, Chastang J-F, Falissard B, Galéra C, Tremblay RE, Côté SM, et al. Food insecurity and children’s mental health: a prospective birth cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52615.

Department for Education. National statistics: GCSE and equivalent attainment by pupil characteristics; 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/gcse-and-equivalent-attainmentby-pupil-characteristics-2014. Accessed 10 Aug 2018.

•• Lambie-Mumford H, Sims L. ‘Feeding hungry children’: the growth of charitable breakfast clubs and holiday hunger projects in the UK. Child Soc. 2018;32:244–54 This is the first review to synthesise the knowledgebase on UK charitable responses to children's food insecurity.

Aceves-Martins M, Cruickshank M, Fraser C, Brazzelli M. Child food insecurity in the UK: a rapid review. Public Health Res 2018;6(13).

United Nations. World economic situation and prospects; 2018. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wpcontent/uploads/sites/45/publication/WESP2018_Full_Web-1.pdf. Accessed 05 July 2018.

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fabregues S, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 user guide; 2018. http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf. Accessed 27 Sept 2018.

Dunifon R, Kowaleski-Jones L. The influences of participation in the National School Lunch Program and food insecurity on child well-being. Soc Serv Rev. 2003;77:72–92.

Gundersen C, Kreider B, Pepper J. The impact of the National School Lunch Program on child health: a nonparametric bounds analysis. J Econ. 2012;166:79–91.

Kreider B, Pepper JV, Gundersen C, Jolliffe D. Identifying the effects of SNAP (food stamps) on child health outcomes when participation is endogenous and misreported. J Am Stat Assoc. 2012;107:958–75.

Gundersen C, Kreider B, Pepper JV. Partial identification methods for evaluating food assistance programs: a case study of the causal impact of snap on food insecurity. Am J Agric Econ. 2017;99:875–93.

Carney PA, Hamada JL, Rdesinski R, Sprager L, Nichols KR, Liu BY, et al. Impact of a community gardening project on vegetable intake, food security and family relationships: a community-based participatory research study. J Community Health. 2012;37:874–81.

Munday K, Wilson M. Implementing a health and wellbeing programme for children in early childhood: a preliminary study. Nutrients. 2017;9. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9091031.

Dave JM, Liu Y, Chen T-A, Thompson DI, Cullen KW. Does the Kids Café Program’s nutrition education improve children’s dietary intake? A pilot evaluation study. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018;50:275–282.e1.

Racine EF, Coffman MJ, Chrimes DA, Laditka SB. Evaluation of the Latino food and fun curriculum for low-income Latina mothers and their children: a pilot study. Hisp Health Care Int. 2013;11:31–7.

Bruce JS, De La Cruz MM, Moreno G, Chamberlain LJ. Lunch at the library: examination of a community-based approach to addressing summer food insecurity. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20:1640–9.

Harvey-Golding L, Donkin LM, Defeyter MA. Universal free school breakfast: a qualitative process evaluation according to the perspectives of senior stakeholders. Front Public Health. 2016;4:161.

• Defeyter MA, Graham PL, Prince K. A qualitative evaluation of holiday breakfast clubs in the UK: views of adult attendees, children, and staff. Front Public Health. 2015;3:199 This is the only qualitative paper included in this review which triangulates the opinions of staff and attendees at a community intervention to tackle children's food insecurity. As attendees voices are critical in evaluative work, this is an important paper.

Graham PL, Crilley E, Stretesky PB, Long MA, Palmer KJ, Steinbock E, et al. School holiday food provision in the UK: a qualitative investigation of needs, benefits, and potential for development. Front Public Health. 2016;4:172.

Fram MS, Ritchie LD, Rosen N, Frongillo EA. Child experience of food insecurity is associated with child diet and physical activity. J Nutr. 2015;145:499–504.

Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: Wiley Online Library; 2008.

Roustit C, Hamelin A-M, Grillo F, Martin J, Chauvin P. Food insecurity: could school food supplementation help break cycles of intergenerational transmission of social inequalities? Pediatrics. 2010;126:1174–81.

Jones SJ, Jahns L, Laraia BA, Haughton B. Lower risk of overweight in school-aged food insecure girls who participate in food assistance: results from the panel study of income dynamics child development supplement. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:780–4.

Kohn MJ, Bell JF, Grow HMG, Chan G. Food insecurity, food assistance and weight status in US youth: new evidence from NHANES 2007–08. Pediatr Obes. 2014;9:155–66.

Nalty CC, Sharkey JR, Dean WR. School-based nutrition programs are associated with reduced child food insecurity over time among Mexican-origin mother-child dyads in Texas border colonias. J Nutr. 2013;143:708–13.

Khan S, Pinckney RG, Keeney D, Frankowski B, Carney JK. Prevalence of food insecurity and utilization of food assistance program: an exploratory survey of a Vermont middle school. J Sch Health. 2011;81:15–20.

Fletcher JM, Frisvold DE. The relationship between the school breakfast program and food insecurity. J Consum Aff. 2017;51:481–500.

Corcoran SP, Elbel B, Schwartz AE. The effect of breakfast in the classroom on obesity and academic performance: evidence from New York City. J Policy Anal Manag. 2016;35:509–32.

• Shemilt I, Harvey I, Shepstone L, Swift L, Reading R, Mugford M, et al. A national evaluation of school breakfast clubs: evidence from a cluster randomized controlled trial and an observational analysis. Child Care Health Dev. 2004;30:413–27 This is one of a small number of RCTs captured in this review. It exemplifies the difficulties with conducting RCTs with public health interventions, and makes a clear statement about the necessary policy changes to overcome such difficulties.

Nguyen BT, Ford CN, Yaroch AL, Shuval K, Drope J. Food security and weight status in children: interactions with food assistance programs. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:S138–44.

Rodriguez J, Applebaum J, Stephenson-Hunter C, Tinio A, Shapiro A. Cooking, Healthy Eating, Fitness and Fun (CHEFFs): qualitative evaluation of a nutrition education program for children living at urban family homeless shelters. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:S361–7.

Sharma SV, Upadhyaya M, Bounds G, Markham C. A public health opportunity found in food waste. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd14.160596.

Kastorini CM, Lykou A, Yannakoulia M, Petralias A, Riza E, Linos A. The influence of a school-based intervention programme regarding adherence to a healthy diet in children and adolescents from disadvantaged areas in Greece: the DIATROFI study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70:671–7.

Rivera RL, Maulding MK, Abbott AR, Craig BA, Eicher-Miller HA. SNAP-Ed (supplemental nutrition assistance program-education) increases long-term food security among Indiana households with children in a randomized controlled study. J Nutr. 2016;146:2375–82.

United States Department of Agriculture: Food and Nutrition Service. Women, infants, and children (WIC); 2018. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/women-infants-and-children-wic.

Kreider B, Pepper JV, Roy M. Identifying the effects of WIC on food insecurity among infants and children. South Econ J. 2016;82:1106–22.

Black MM, Cutts DB, Frank DA, et al. Special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children participation and infants’ growth and health: a multisite surveillance study. Pediatrics. 2004;114:169–76.

Black MM, Quigg AM, Cook J, et al. WIC participation and attenuation of stress-related child health risks of household food insecurity and caregiver depressive symptoms. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:444–51.

Frongillo EA, Jyoti DF, Jones SJ. Food stamp program participation is associated with better academic learning among school children. J Nutr. 2006;136:1077–80.

Beharie N, Mercado M, McKay M. A protective association between SNAP participation and educational outcomes among children of economically strained households. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2017;12:181–92.

Gibson D. Long-term food stamp program participation is differentially related to overweight in young girls and boys. J Nutr. 2004;134:372–9.

Burgstahler R, Gundersen C, Garasky S. The supplemental nutrition assistance program, financial stress, and childhood obesity. J Agric Resour Econ. 2012;41:29–42.

Mabli J, Worthington J. Supplemental nutrition assistance program participation and child food security. Pediatrics. 2014;133:610–9.

Sharkey JR, Dean WR, Nalty CC. Child hunger and the protective effects of supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP) and alternative food sources among Mexican-origin families in Texas border colonias. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-13-143.

Gundersen C, Kreider B, Pepper J, Tarasuk V. Food assistance programs and food insecurity: implications for Canada in light of the mixing problem. Empir Econ. 2017;52:1065–87.

Nalty CC, Sharkey JR, Dean WR. Children’s reporting of food insecurity in predominately food insecure households in Texas border colonias. Nutr J. 2013;12:15.

Zhang J, Yen ST. Supplemental nutrition assistance program and food insecurity among families with children. J Policy Model. 2017;39:52–64.

Beck AF, Henize AW, Kahn RS, Reiber KL, Young JJ, Klein MD. Forging a pediatric primary care–community partnership to support food-insecure families. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e564–71.

Collins AM, Klerman JA. Improving nutrition by increasing supplemental nutrition assistance program benefits. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:S179–85.

Klerman JA, Wolf A, Collins A, Bell S, Briefel R. The effects the summer electronic benefits transfer for children demonstration has on children’s food security. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2017;39:516–32.

Korenman S, Abner KS, Kaestner R, Gordon RA. The Child and Adult Care Food Program and the nutrition of preschoolers. Early Child Res Q. 2013;28:325–36.

Loibl C, Snyder A, Mountain T. Connecting saving and food security: evidence from an asset-building program for families in poverty. J Consum Aff. 2017;51:659–81.

Hanson KL, Kolodinsky J, Wang W, Morgan EH, Jilcott Pitts SB, Ammerman AS, et al. Adults and children in low-income households that participate in cost-offset community supported agriculture have high fruit and vegetable consumption. Nutrients. 2017;9. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070726.

Tapper K, Murphy S, Moore L, Lynch R, Clark R. Evaluating the free school breakfast initiative in Wales: methodological issues. Br Food J. 2007;109:206–15.

W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Using logic models to bring together planning, evaluation & action logic model development guide. Michigan; 2001. https://www.bttop.org/sites/default/files/public/W.K.%20Kellogg%20LogicModel.pdf. Accessed 02 Nov 2018.

Kubisch AC, Fullbright-Anderson K, Connell JP. Evaluating community initiatives: a progress report. New approaches to eval. community initiat. vol. 2 Theory, meas. anal. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute; 1998. p. 1–13.

Reutter LI, Stewart MJ, Veenstra G, Love R, Raphael D, Makwarimba E. “Who do they think we are, anyway?”: perceptions of and responses to poverty stigma. Qual Health Res. 2009;19:297–311.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Clare E. Holley and Carolynne Mason declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: Tables 1 and 2 captions were corrected.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Maternal and Childhood Nutrition

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Holley, C.E., Mason, C. A Systematic Review of the Evaluation of Interventions to Tackle Children’s Food Insecurity. Curr Nutr Rep 8, 11–27 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-019-0258-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-019-0258-1