Abstract

Public organizations have widely adopted corporate entrepreneurial strategy. The complex and financially constrained context in which public organizations operate calls for the implementation of entrepreneurial actions. Our study validates the theoretical framework of Kearney and Meynhardt (Int Public Manage J 19(4):543–572, 2016), which recognizes strategic vision and organizational factors as the main components of corporate entrepreneurial strategy and theorize its main antecedents and outcomes. Thus, by analyzing the public University of Bergamo as a single case study, we demonstrate that entrepreneurial orientation is beneficial for public organizations such as universities. Specifically, the entrepreneurial leadership was able to recognize opportunities in the unsupportive political external environment characterizing the entire Italian public sector during the period 2009-2015. The austerity policy known as the Gelmini reform was designed to make public organizations more efficient and transparent, by cutting personnel costs, by explicitly accounting for university budgets, and introducing external controls on university governance and performance. Despite the climate of general austerity, the entrepreneurial leadership succeeded in engaging several stakeholders and grounding an entrepreneurial strategy at the university. This has significantly changed the image of this public organization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Corporate entrepreneurship strategy (henceforth CES) is a unique organizational technique adopted by organizations to embrace a strategic approach that enables entrepreneurial activities (Ireland et al., 2009). Although it originated in the private sector, it has been taking hold solidly in public sector organizations because of the complex environment in which they operate. Reduced budgets, shifting funding sources, divergent stakeholder expectations, more complex societal demands, unfunded mandates from elected bodies, rising costs, pressure for greater transparency and accountability, union demands, and new technologies are just a few of the complexities that public organizations experience (Andrews et al., 2005).

Public managers are under increasing pressure to provide a strategic approach to overcome such obstacles and enhance organizational performance (Andrews et al., 2011; Meier & O’Toole, 2009). Because CES is mostly the task of those at the top of the organization, it does not happen just once leaders within organizations should have a vision for it and be responsible for monitoring and assessing the system to accomplish organizational goals and objectives (Kearney & Meynhardt, 2016). Eloquent expositions of entrepreneurial leadership, mainly drawn on Anglo-Saxon cases have investigated the role of entrepreneurs in public administration as prominent individuals who can enact entrepreneurship (Currie et al., 2008; Meier & O’Toole, 2009; Osborne, 1993; Osborne & Brown, 2011; Sadler, 2000). However, there is still much to study regarding the conditions under which these kinds of individuals emerge and enact a (successful) CES (Currie et al., 2008; Kearney & Meynhardt, 2016; Kearney & Morris, 2015).

Our study aims to fill this gap by addressing the research question: “how can an entrepreneurial leadership emerge and shape the entrepreneurial orientation of a public organization like the university?”

By adopting the framework of Kearney and Meynhardt (2016), we describe the individual, organizational, and contextual factors that concur to establish a CES by public leaders. We specifically focus on the reaction that individuals in leadership position may have in face of the increasing pressures that government policies (Currie et al., 2008) as well as external environmental conditions (Currie & Procter, 2005; Kearney et al., 2010) should be imposed. We focus on leadership at an Italian public university – the University of Bergamo during the period 2009–2015. It is appropriate to investigate how leadership steers an organization towards CES, a supportive environment. The university context was chosen because universities have been largely recognized as promoters of entrepreneurship owing to the administrative techniques, strategies, and competitive postures that they develop (Guerrero & Urbano, 2012). Italian universities represent a convenient setting because, on the one hand, they are characterized by a pronounced entrepreneurial attitude (Civera et al., 2019; Fini et al., 2011) and on the other hand they are representative of the European continental tradition, where higher education institutions are public, subject to regulatory interventions, and highly dependent on the state in terms of resources (Bleiklie et al., 2011; Ferlie et al., 2008). The period between 2009 and 2015 was selected because, in those years, an extensive reform in the Italian university sector occurred after the 2008 crisis and consequent cuts in university funding. The Gelmini reform was implemented in 2012 and was inspired by the new Public Management movement, which began in the US in the Eighties and in Europe in the Nineties (Grimaldi et al., 2011). The aim is to make universities more accountable, transparent, and efficient (Bleiklie et al., 2011; Ferlie et al., 2008). It in turn, led to the formal strengthening of the university leadership managerial role (Bleiklie et al., 2011) and the introduction of a more hierarchical-bureaucratic model of governance (Brunsson & Sahlin-Andersson, 2000).

The case of the University of Bergamo represents an example of best practice, as despite the climate of general austerity, the entrepreneurial leadership of the public organization was able to engage several stakeholders and ground an entrepreneurial strategy within the whole university. This results in a relevant change of the university image, which changes from an isolated peripheral position to become an innovative and dynamic reality within a local context.

The reminder of this paper is organized as follows. First, we explore the concept of CES and how it conceptually differs between the private and public sector. Moreover, we highlight the distinctive challenges faced in the university context. Second, we set out our research design, by emphasizing the rationale for choosing of the Italian public university of Bergamo. Our empirical findings will follow, where we illustrate the enactment of CES and the key role of its leadership. Concluding remarks will close the paper.

2 Theoretical framework

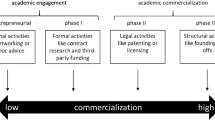

We embrace the Kearney and Meynhardt’s (2016) attempt to create a theoretical framework for CES within public sector organizations. A graphical representation of this process is shown in Fig. 1. Accordingly, we identify the strategic vision of an organization together with organizational factors such as organizational conditions, entrepreneurial orientation, and individual behavior, as components of CES. Once the main components were identified, we considered the antecedents and consequences in terms of outcomes as part of our framework. Below, we discuss the most relevant studies.

Corporate entrepreneurship strategy in public sector organizations. Adapted from Kearney and Meynhardt (2016). Directing Corporate Entrepreneurship Strategy in the Public Sector to Public Value: Antecedents, Components, and Outcomes. International Public Management Journal, 19(4), pp. 546

2.1 The antecedents of CES

According to the contingency theory of organizations, which posits that organization strategy is a function of environmental resources (Miller & Friesen, 1983), we focus on the external environment. Thus, entrepreneurship in every sector is the result of capitalization on external opportunities (Ireland et al., 2009), and an external environment may be full or empty of opportunities (Kearney & Morris, 2015). According to Kearney and Meynhardt (2016), four environmental conditions affect CES in the public sector: munificence, dynamism, hostility, and embeddedness.

Munificence refers to the availability of critical resources from the external environment (Miller & Friesen, 1983). The entrepreneurial literature has underlined the benefits derived from environmental munificence, which represents an opportunity to eventually exploit, such as generating slack resources to grow and evaluate investments (Simsek et al., 2007) while facing a limited amount of competition for new entrants (Nielsen, 2015). In contrast, for public organizations opportunities are to be searched in non-munificent environments because they are more likely to experience a shortage of resources, both financial and non-financial in nature (Kearney & Morris, 2015). This is especially true for universities that, when a deterioration of public resources occurs, are the first ones to be penalized as education is assessed as less strategic than other public sectors such as healthcare and social security (see for example Civera et al., 2021).

Dynamism is related to the level of environmental uncertainty. Dynamic environments are propellers of entrepreneurship, as they stimulate new ideas and open doors for new opportunities in terms of new technologies and markets (Wu et al., 2021). In addition, public organizations are subjected to a great extent of uncertainty and more likely can find new opportunities when challenged (Carnes et al., 2019; Meier & O’Toole, 2009). Universities have recently experienced quite a bit of dynamism, having undertaken a change in strategy due to the New Public Management (NPM) movement (Bleiklie et al., 2011). The rationale behind NPM is the need to make universities more accountable, transparent, and efficient through hierarchization, monitoring, and financial austerity (Ferlie et al., 2008). Universities must strive to find alternative sources of revenue to ensure daily functioning (Bleiklie et al., 2011).

Hostility represents the degree of difficulty in accessing external resources because of the presence of other actors competing for the same resources (Andrews et al., 2005). Entrepreneurial strategies may be challenged by hostile contexts (Kearney & Morris, 2015) whereas public organizations that are used to competing for a finite amount of resources can be motivated by it. Universities are thus used to competing for students, researchers, and funding that are limited (Cattaneo et al., 2020). Universities have adopted innovative strategies over time, leading to the development of entrepreneurial universities (Guerrero & Urbano, 2012).

Finally, embeddedness is the extent to which organizations develop a strong interrelation with the environment. The literature on entrepreneurial ecosystems has outlined the relevance of integrating a company with its surrounding institutions to pursue a successful entrepreneurial strategy (Audretsch & Belitski, 2017). It can be the same for public organizations, that are exposed to a wide variety of stakeholders, including the whole society, which can help identify needs and opportunities (Bernier & Hafsi, 2007). A particular argument can be developed for universities, that are accountable to policy makers, students and their families, university personnel, and the wider public, depending on the mission under consideration (Cheng, 2014). Interaction with such a kaleidoscope of actors may induce universities to detect and exploit new opportunities (Posselt et al., 2019; Siegel & Wright, 2015).

2.2 The component of CES

Parallelism with CES in the private sector suggests that the first ingredient to develop CES is entrepreneurial strategic vision. It can be defined as the tool used by an organization top-level managers to describe the kind of organization they want to run in the future (Ireland et al., 2009). It represents a commitment to innovation and entrepreneurial processes (Ireland et al., 2009). In the public sector the acceptance may be broader, as the ultimate aim is to improve public services (Kearney & Meynhardt, 2016). The need for a strategic vision has permeated the public sector because of the demand for more transparency in objectives, outputs, and results, as well as rising managerialism (Llewellyn & Tappin, 2003). However, in the public sector and universities, bureaucracy may constitute a major obstacle to achieving an entrepreneurial strategic vision. It is, therefore, necessary for management in the public sector to engage in entrepreneurial activities by shaping the organization to successfully realize its strategic vision (Guerrero & Urbano, 2012). The role of rectors in universities has been demonstrated to be fundamental to organizational entrepreneurial performance and the root of entrepreneurial culture and mechanisms (Sporn, 2001).

2.2.1 Organizational conditions

Alongside, there are several specific organizational conditions which can be conducive to CES.

First, the leadership support. Thus, an entrepreneurial strategy can be realized within an organization when leaders promote entrepreneurial actions by providing support and resources (Kuratko et al., 2005). Leadership has been found to be beneficial for organization’s entrepreneurial outcomes, more specifically in the private sector, public sector, and universities (Klofsten et al., 2019).

Second, work discretion/autonomy is the extent to which organizations tolerate failures and delegates responsibility and authority to lower levels of the hierarchy (Hornsby et al., 2002). Organization members are more entrepreneurial when they perceive that they have room for maneuvering. Unfortunately, discretion is difficult to achieve in the public sector, where policymakers scrutinize individuals. A successful mechanism may be the development of excellence in specific indicators and situations (Currie et al., 2008). Thus, public sector leaders may earn some autonomy. For instance, in the case of universities, excellent ones are often located in context in which the governance of higher education institutions has experienced the most advanced reforms in terms of autonomy and accountability (Michavila & Martinez, 2018).

Third, rewards for individuals’ entrepreneurial activities. Recognition of individuals’ tendencies to behave entrepreneurially is the most relevant mechanism to successfully reward entrepreneurship in organizations (Hornsby et al., 2002). Recognition may be financial or non-financial; both have proven beneficial in the private sector (Hornsby et al., 2009). In contrast, in the public sector, financial rewards may become detrimental as they can have a crowding out effect on intrinsic motivations typical of the public sphere, such as advancing society, solving environmental and social issues, and diffusing science and innovation (Civera et al., 2020; Hayter, 2011). In universities, this has been a long debated topic as entrepreneurship has been perceived as incompatible with the Mertonian connotation of science (Lam, 2011). Tools such as intellectual property and royalties have been introduced and fiercely criticized (Grimaldi et al., 2011). Thereby, in the public sector recognizing the contribution of individuals and groups within the organization is suggested to be the most effective way to foster entrepreneurship (Kearney et al., 2009).

Fourth, time availability. Potential corporate entrepreneurs may be able to take advantage of opportunities for innovation that may be hindered by their mandated job schedules if they have extra time to devote (Hornsby et al., 2009; Kuratko et al., 2014). Teamwork and appropriate time distribution can also be beneficial for public sector organizations.

Fifth and last, flexibility. Flexibility is important for entrepreneurship as it allows adaptation to any eventuality and enhances the exchange of resources, including knowledge within and outside organizations (Acs et al., 2013; Qian & Acs, 2013). Universities among other public organizations are traditionally extremely rigid and flexible flows seldom occur. Sadler (2000) argued that entrepreneurship can occur even in hierarchical structures.

2.2.2 Entrepreneurial orientation

In addition to entrepreneurial strategic vision and organizational conditions, entrepreneurial orientation defined as the decision-making process, activities, and practices leading to entrepreneurship, and has been identified as a part of CES (Kreiser et al., 2020). Entrepreneurial orientation comprises three components: innovativeness, risk-taking, and proactiveness (Covin & Slevin, 1991).

Innovativeness is related to creativity and experimentation. Entrepreneurship is fostered by the innovativeness of individuals and organizations (Qian & Acs, 2013). In public sector organizations, innovativeness refers to reorganizing decision-making, financing, and processes to improve the quality of the service offered by overcoming bureaucratic and political obstacles (Osborne & Brown, 2011).

Risk taking is the extent to which organizations and their managers are eager to invest large resources in projects with uncertain results and the potential for severe loss (Ireland et al., 2009). By definition, an entrepreneur is a risk-taker (McGrath et al., 1992; Qian & Acs, 2013). In the public sector, risk taking is manifested through investment decisions and strategic actions in the face of bureaucratic and political barriers (Kearney & Morris, 2015). Nevertheless, risk-taking in the public sector is rare because failure is hardly an option. As pointed out by Currie et al. (2008), in the public education sector due to the prevalent blame culture and public awareness of mistakes, individuals in formal leadership positions may place a greater emphasis on preserving stability rather than encouraging innovation and change through entrepreneurial activity.

Proactiveness has the same meaning for public and private sector entrepreneurship. This is the ability to anticipate opportunities and being able to ground an innovation before others (Covin & Slevin, 1991). In the university sector anticipating a tendency is relevant for capturing students in the face of competitors or attracting research staff (Smilor et al., 2007).

2.2.3 Individual behavior

Entrepreneurial orientation has supported the idea that, in general, the individual matters more than the organization. The last component of CES is individual behavior. The definition of entrepreneurship relates to a single individual dimension. The entrepreneur is often described as a hero who can change the status quo (Qian & Acs, 2013). Individual characteristics interact with the environment to create conditions that foster entrepreneurship. Individual behavior is revealed through specific actions such as entrepreneurial alertness, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial effectuation (Kearney & Meynhardt, 2016).

Entrepreneurial alertness refers to the ability to recognize opportunities. Public managers should be aware of the political climate to advance or garner support for a specific project. It introduces a delicate layer, politics, that makes the environment extremely constrained. Currie et al. (2008) illustrate the restricted policy context for entrepreneurial behavior represented by the New Public Management policy era for the English education sector.

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s confidence in performing a task. Entrepreneurs possess a great capacity for self-efficacy because they persevere in achieving their goals and overcoming eventual failures (Ahlin et al., 2014). They tend to persist in extremely overwhelming environments. Therefore, self-efficacy is a necessary aptitude for public sector managers, who face additional complexities related to bureaucracies and the political setting, to name a few (Kearney & Meynhardt, 2016).

Entrepreneurial effectuation is the ability to ground projects by trying as many different solutions as possible with the limited resources at hand (Sarasvathy, 2001). Effectuation is the idea that although the future is uncertain, entrepreneurs may influence a portion of the value creation process by using a certain set of tools at their disposal (Fisher, 2012). For organizations in the public sector, effectuation is a crucial process as it operates in more complicated situations with uncertain futures and scarce resources (Kearney & Meynhardt, 2016). Universities have been increasingly forced to adopt entrepreneurial effectuation approaches in their teaching (Watson & McGowan, 2020) and research activities (De Silva et al., 2023).

2.2.4 Outcomes

The final part of our framework is the type of outcome that a public sector organization can generate (Kearney & Meynhardt, 2016).

Mirroring what happens in the private sector, corporate venturing or strategic renewal may occur. The former involves creating new businesses. This outcome has been studied extensively in the public sector through academic spinoffs (Civera et al., 2019; O’Shea et al., 2008; Rasmussen & Wright, 2015). The latter involves the implementation of continuous, small transformations or disruptive changes. Examples include the development of new business models, the offering of new products, services, and processes; and the generation of new sources of revenue (Kearney & Morris, 2015). Translated in the university context, it could be exemplified by changes made to address COVID like the hybridization of teaching; and resorting to new platforms, technologies, and teaching models (Komljenovic, 2022; Watermeyer et al., 2021).

However, the public sector has public and social dimensions that makes the outcome difficult to define. Thus, the public sector aims to create what is called public value – that is what the wider public cares about.

According to the classification from Meynhardt (2009), four distinct value-creation axes can be identified: first, an instrumental-utilitarian value, such as improved service or financial results; second, a moral-ethical value, such as increased fairness and justice; third, a political-social value, such as improved relationships between various social groups; and fourth, a hedonistic-aesthetic value, such as improved reputation and self-esteem of an organization (Meynhardt, 2009). A university may pursue an instrumental-utilitarian approach by providing higher-quality services in terms of teaching and research activity, a moral-ethical approach by increasing access conditions like American colleges are trying to do, a political-social value, by involving external actors through effective communication, or a hedonistic- aesthetic approach by establishing themselves as top universities for example by climbing in the university rankings.

2.3 Research design

CES studies have extensively adopted quantitative approaches. Whenever leadership and its specific behaviors and dimensions must be investigated, scholars advocated for qualitative analyses (Bryman, 2004; Currie et al., 2008). In particular, a single-case study approach has been extensively adopted over the last 15 years to improve how people frame and solve collective problems arising in factual contexts other than those studied intensively (Barzelay, 1993; Crosby & Bryson, 2018). This approach has been validated in several social science contexts, including business and entrepreneurship (Colombelli et al., 2021; Cunningham et al., 2017; Villani & Lechner, 2021).

In light of this, our study is a qualitative, interview-based investigation of leadership in an Italian public university, enriched with access to official statements issued by the leadership, such as strategic plans, annual reports, and balance sheets (Villani & Lechner, 2021).

The University of Bergamo was selected for the following reasons. It was revelatory for the theoretical characteristics associated to the CES in a public medium-sized university located in a provincial context in competition with bigger and better-established universities nearby (those in Milan and Brescia). This may also be the case for other Italian and non-Italian public universities.Footnote 1 In general, it is indicative of the wider Italian public university context and beyond the public sector, which has been subject to a comprehensive austerity policy reform within the last ten years, the Gelmini reform. This reform was designed to solve the inefficiency and lack of transparency of the Italian public administration sector and had repercussions for employees and institutions in the public sector. In addition, the authors had access to all relevant information and data and can be considered among the most informed people on the activities initiated at the University.

The Gelmini reform focused on transforming university governance through the compulsory revision of statutes (Donina et al., 2015b). It also involved changes to the rector’s office. Specifically, the rectors could be elected for one non-renewable 6-year term only. Formerly, the length and renewability of the mandate was at the discretion of each institution. Therefore, rectors’ influence is therefore more limited in time, but their role in institutional governance has been strengthened by performing managerial and directive tasks and exercising decisional power on strategic and financial matters (Donina & Hasanefendic, 2019). The rector, elected from the academic community among full professors at the university as primus inter pares, chairs both collegial governing bodies (the Senate and Board), and her authority prevails in the decision-making process (Donina et al., 2015a). This is the rationale for focusing on leadership roles within universities.

The Gelmini reform also introduced new allocation mechanisms concerning the FFO (Fondo di Finanziamento Ordinario), by specifically implementing the standard cost per student in the funding formula and increasing the share of funds allocated through a competitive mechanism (Lumino et al., 2017). Public funding was distributed according to the number of students enrolled as well as performance indicators concerning the teaching, research, and internationalization dimensions. therefore, it became imperative for universities to attract students and overperform other institutions.

This transformation occurred from in the period 2009–2015, a climate of general austerity was present in Italy, ultimately leading to severe resource cutting (Civera et al., 2021). The annual basic operational grant for Italian universities, the FFO, has been characterized by a 10% contraction. In addition, staff turnover, limited by law, was tightened from 50% (quota since 2009) to 20% (Ministerial Decree 95/2012). Additionally, a block in staff turnover was implemented (Legislative Decree 78/2010), with the consequent suspension of salary adjustments for all public sector employees, including university professors.

The implementation of the Gelmini reform in a time of austerity increased competition amongst the Italian universities, as NPM reforms rely on increasing confrontation between service providers and the creation of markets, or “quasi-market” mechanisms, accountability, and control for results, through strong performance measurement (Ferlie et al., 2008). These effects were exacerbated by the contextual reduction of FFO and provided for the strongest effect in Lombardy, the region where the University of Bergamo is located, where the challenge for student attractiveness is toughest due to the presence of 12 universities and the highest Italian level of competitiveness due to the proximity of other institutions (Cattaneo et al., 2017). Being located close to Milan (Bergamo is 50 km to the northeast), competition with the top-ranked Italian institutions (e.g. the Polytechnic of Milan with respect to Technology, and the Bocconi University for Business Studies) has always been a challenge for the University of Bergamo. Therefore, this case was chosen because of its disadvantageous position in an unfavorable context.

The case study presented in this paper was performed by interviewing the Rector of the University of Bergamo during the period 2009–2015. Before the Gelmini reform was approved, Stefano Paleari was elected in 2009. His mandate led the university over a period of extreme challenges, as described above. We conducted an extensive interview with the rector, focusing on each of the components of the CES framework, and identifying the antecedents, components, and outcomes of the CES in a period of austerity. The interview is best considered as “narrative” because our interviewee is telling stories, typically time sequenced, relating to his experiences (Riesman, 1993). We draw on well-established literature arguing that narrative is an appropriate interpretive lens for understanding the processes of organizing (Currie & Brown, 2003; Rhodes, 2000). Our narrative approach allows for a sophisticated analysis of an individual efforts to describe his leadership behavior. To provide a counterpart of the rector’s thoughts, we interviewed Giuseppe Giovanelli, the Managing Director of the University of Bergamo at that time. As Managing Director, he was nominated by the Governing Board at the suggestion of the previous Rector. Legally, he was responsible for the administrative transparency of the university, thereby managing non-academic staff and interacting with the two governing bodies (i.e. the Governing Board and the Academic Senate) to implement the general directives. by virtue of his role, he was aware of the reactions of both academic and non-academic staff to the rector’s behavior. He was the most informed person when verifying the rector’s statements.

2.4 Findings

In this section we report the findings of our analysis of the University of Bergamo, with reference to the implementation of the CES during the period 2009–2015, corresponding to the mandate of Rector Stefano Paleari. We used the CES framework introduced in the previous section to describe the antecedents, components, and outcomes. Our key arguments derived from the interview with the rector and are enriched by the official statements issued by the leadership team (strategic plans, annual reports, and balance sheets).

2.5 The antecedents of CES

As discussed by Kearney and Morris (2015), opportunities for the implementation of CES in public organizations are often searched for in non-munificent environments, because the lack of resources, both financial and non-financial, leads to the implementation of a long-term vision inspired by dynamic and sustainable approaches. In these respects, the interviewee mentions that “the scarcity of external resources, posed significant challenges during the implementation of our strategy at the University of Bergamo,” and mentions amongst them the following: First, “the implementation of the Gelmini reform in Italy brought about substantial changes to the higher education system. This reform aimed to enhance efficiency and accountability but also introduced budget cuts and reduced public funding for universities. Consequently, the University of Bergamo faced financial constraints and a decline in public resources, making it challenging to invest in new initiatives and ventures.” Second, “the reform had implications for academic careers. It introduced a tenure-track system, emphasizing performance-based evaluations and reducing job security for academic staff. This created a sense of uncertainty and, in some cases, discouraged risk-taking and innovative approaches among faculty members who might have been hesitant to invest time and effort in entrepreneurial activities.” Third, “I suffered a lack of organizational incentives. Given limited resources, providing incentives for staff and faculty members to engage in entrepreneurship became challenging. Implementing new initiatives, such as innovation hubs and incubators, required financial support and time commitment from various departments, which might not have been readily available owing to budgetary constraints.” Fourth, “As the former rector, I faced the challenge of developing a strategy without immediate, tangible incentives or substantial support from external sources. The implementation of an entrepreneurial strategy demanded additional efforts in terms of networking, seeking partnerships, and navigating through bureaucratic processes while managing the day-to-day responsibilities of the university.” However, such challenges were at the basis of the implementation of the CES, given that, as the rector said, “We recognized the importance of staying resilient and adaptive to achieve our goals. Although the lack of resources made it difficult to allocate resources for entrepreneurship initiatives, it reinforced the urgency and necessity of implementing such strategies to secure the university long-term viability.”

A dynamic environment has been identified as a propeller of CES, stimulating ideas and opening doors for new opportunities (Wu et al., 2021). This was perceived as a consequence of policy changes pushing for the implementation of New Public Management practices (Bleiklie et al., 2011). In fact, as the rector stated “the Gelmini reform, often perceived as a challenge, actually created a number of opportunities for implementing our strategy, and we tried to embrace the opportunities presented by the reform’s emphasis on autonomy and performance orientation.” First, the reform introduced the single mandate for rectors, “allowing us to reduce internal political distractions, enabling us to focus on strategic planning.” Second, all universities were required to revise their own statute, redefining the roles of governing bodies, and the institutional relationships, which “provided us with the opportunity to revise our internal governance structures. We leveraged this opportunity to engage stakeholders, including faculty, staff, and students, in the decision-making process. Involving them in shaping the new statute fostered a sense of ownership and belonging within the university community. This sense of involvement and ownership was instrumental in gaining support for the corporate entrepreneurship strategy and encouraging participation in entrepreneurial activities.” Third, “the reform introduced a performance-based evaluation system for universities, encouraging focus on outcomes and results. This shift towards performance orientation aligned well with our strategy, as we could now measure the success of our initiatives based on tangible outcomes, such as research impact, industry partnerships, and revenue generation, with a visible impact on the FFO,” the main source of public funding in Italy.

The third antecedent of CES is, hostility, that is the difficulty in accessing external resources. This is relevant in the case of Italian universities, as the consequences of the Gelmini reform created a boost in competition to attract students (Cattaneo et al., 2017), with the largest impact in Lombardy, where the University of Bergamo is located. According to the rector, “Lombardy, being a region with a high number of universities, resulted in intense competition for students. Competition can lead to better quality and innovation, although it also pressures the University of Bergamo to differentiate itself and attract students. This was particularly challenging given the lack of sufficient resources to invest in marketing and outreach efforts to stand out in the competitive landscape.” This hostility was perceived as particularly severe in Bergamo, as “the University of Bergamo faced the challenge of a perceived lack of academic culture and reputation compared to more established universities in Italy. This perception did not impact our ability to attract scholars given the excellent environment but was rather a challenge with respect to student families, making it difficult to gain recognition for our research and academic programs.” The Managing Director pointed out that the University of Bergamo suffered from “a sense of inferiority in comparison with public and economic institutions. The University was unable to influence the external environment.”

However, the rector believes that these challenges have greatly boosted the implementation of several initiatives at the University of Bergamo. Among them, the university invested in a strong relationship with the local authority “to foster a stronger academic culture in Bergamo and enhance the university’s connection with the city. This was so effective that, by the end of my mandate, municipality declared Bergamo a ‘university city,’ coming quite a long way for a town which was lacking university signs in the streets just a few years before! This initiative aimed to promote a sense of pride and ownership among the local community, encouraging greater support for the university’s endeavors.”

Finally, the University of Bergamo was embedded in the environment owing to its exposure to a wide variety of stakeholders, including society as a whole (Bernier & Hafsi, 2007). According to the rector, “We faced the challenge of having a small alumni network, and skepticism of stakeholders about its academic reputation or quality. However, once again, challenges came with opportunities, as the University of Bergamo was a young institution, and it was easier to implement novelties in Bergamo than in well-established universities. Bergamo entrepreneurs have often felt peripheral in Lombardy, but there was an opportunity to be linked to an institution that wanted to look internationally and compete at the highest levels.” However, during the mandate, the Managing Director noted that “the University became ‘empathic’ in the sense that it started to influence and being influenced by the external context.” (See Table 1).

2.5.1 The components of CES

The first component in developing CES is entrepreneurial strategic vision, especially in the public sector, to allow the leader to shape the organization and successfully transmit the strategic vision (Guerrero & Urbano, 2012). The words of the Managing Director show how the rector succeeded in this task “Having leadership, a vision superior to that of others. This vision was also transmitted, overcoming resistance.” The rector pointed out that the strategic vision at the University of Bergamo was made public, through the implementation of “transparent communication with all stakeholders, including faculty, staff, students, local policy makers, and representatives of the industry.” According to the Managing Director “The rector was able to communicate both internally and externally his own vision. His ability to communicate was taken into consideration, and he was respected for that.” For transparent communication, the rector intended “to hold annual meetings where we shared the university strategic vision, goals, and progress with Bergamo’s stakeholders, something the city was not used to. Transparent communication fosters trust and a sense of shared responsibility among stakeholders. At these annual meetings, we used the presentation of balance sheets as an opportunity to showcase the university academic performance, novelties in internationalization, and reputation building. By presenting clear and concise financial data, we demonstrated how the university efficiently managed its resources to achieve its goals. Balance sheets have become a tool for highlighting our commitment to responsibility and accountability. At a distance, I can define the strategy as Light, Open, and Competitive (LOC)”. This strategy emphasized streamlining administrative processes (light) to maximize operational efficiency, promote openness to new ideas, collaborations, and innovations (open), and adopt a competitive mindset to excel in research, academic, and industry partnerships (competitive).” The ultimate achievement of this strategy was a joint project between the municipality and several local stakeholders. “The project, named ‘Bergamo 2035,’ engaged academic, local policy makers, and industry representatives in envisioning the future of Bergamo. This was a collaborative initiative in which various stakeholders came together to envision how the university and the city could evolve over the next 15 years. Through workshops, brainstorming sessions, and strategic planning exercises, we encouraged participants to contribute their ideas and expertise in shaping the city future”. (See Table 2)

In addition, specific organizational conditions could be identified for the University of Bergamo as conducive to CES. As far leadership support is concerned, the rector mentioned how “My leadership style focused on establishing authority through competence, transparency, and open communication rather than relying on authoritarian measures. Being relatively young and approachable, I fostered a leadership approach that encourages collaboration and teamwork. I value the expertise and input of others, treating all staff with respect to and on a first-name basis.” As proof of that, the Managing Director stated “The rector has never imposed his ideas; he did not believe in a coercive strategy. He was able to maintain a strong internal consensus and listen to people. It was not merely acquiescence but rather a generative listening skill. He has always been attentive to people to understand their needs. With him, people felt free to talk about personal matters, often in front of coffee. He built friendships with others, based mainly on informal connections”.

This was also important for the society. “When we chose to host the Inauguration of the Academic Year in the Donizetti Theatre” the rector explained “We were looked at with skepticism by traditionalists, but the population responded well, and the celebration quickly became an event for the whole city of Bergamo.” As far as autonomy and discretion are concerned, the rector stated, “In managing discipline issues, I recognized the importance of handling matters discreetly and with sensitivity. Instead of publicly reprimanding individuals, I opted for private discussions to address my concerns and provide guidance for improvement. By focusing on constructive feedback and support, I aimed to encourage growth and personal development without shaming or humiliating the individuals.” Indeed, this style was based on rewards and reinforcement for people in the team: “I strongly believed in recognizing and rewarding individuals based on merit and competence rather than political considerations. I ensured that the right people were placed in positions where their skills were best utilized, regardless of political pressures. By promoting a merit-based system, I encouraged a culture of excellence and motivated staff to strive for continuous improvement”. As far as time availability is concerned, the rector pointed out “I understood the importance of time management and leveraging teamwork. By fostering a collaborative environment and delegating responsibilities to capable individuals, I freed up time to focus on strategic decision-making and engaging with stakeholders. Empowering team members to take ownership of their roles not only increased efficiency but also enhanced their professional growth.” The Managing Director underlined how the rector was able to “recognize the autonomy and competency of the administrative staff. This is often a reason for conflicts in other universities, but not in the University of Bergamo during his office.”

Finally, flexibility was a necessary response to the typical rigidity of public sector culture. According to the rector, “Recognizing the challenges posed by the rigid structures and bureaucracy in the Italian university system, I sought to introduce flexibility where possible. This included streamlining administrative processes, encouraging interdisciplinary collaboration, and supporting initiatives that embraced innovative approaches to teaching and research. By championing flexibility, we aimed to adapt to changing circumstances and respond proactively to the evolving needs of the academic community and society.”

In addition, entrepreneurial orientation was required to react to the challenges of the time through innovative, risky, and proactive actions. The rector addressed each element. The level of innovativeness was perceived as very high, as a few programs were introduced, to improve attractiveness in the eyes of talented students (“the ‘Top Ten Students’ Program was designed to attract high-achieving students from the high school system given the average reputation of the university, we offered scholarships to all students qualifying in the top decile of high-school grades, and this increased dramatically our attractiveness”), to increase the quality of bachelor and master programs (“I knew we did not have direct incentive to improve teaching activity, so we tried to enhance the overall quality of programs by setting a number of internal standards that, many years later, are still in place”), and to increase research internationalization (“We introduced the STaRs program, i.e., the ‘supporting talented researchers’ program, creating a competitive environment to attract and retain top-tier researchers. The program provided research fellowships and support for outgoing and incoming visiting programs, encouraging collaboration with other renowned institutions”). By investing in the quality of its students, teaching, and research activities, the University of Bergamo could enhance reputation both in the eyes of academic and non-academic, “as certified by the entry in the Times Higher Education Worldwide ranking, which listed the University of Bergamo for the first time in 2017.” Indeed, risk-taking is an inherent part of entrepreneurial orientation, and the decision to invest significantly in the auditorium (in Italian, Aula Magna) exemplified the university willingness to embrace risks for potential long-term benefits. Here is how the rector approached this decision: “Investing in the Aula Magna was driven by the vision of enhancing the university’s academic environment and reputation. Aula Magna presented an opportunity to attract prominent speakers, researchers, and industry leaders as a prestigious and well-equipped venue for important events, lectures, and conferences. This aligned with our orientation towards creating a dynamic and engaging academic community.” The Managing Director recalled a different moment in the rector’s risk-tanking attitude. This was an intervention to renovate the former Collegio Baroni located in via Pignolo. “We inherited the project from the previous rector, but the implementation phase began with his mandate. It was a complex intervention, within entrepreneurial logic, the valorization of a historic area of the city, with a contemporary architectural intervention within a delicate, historical area. Many did not understand this intervention, and neither did the inhabitants of the neighborhood or in the city. This is a rich neighborhood with wealthy citizens. There were many problems with making it, but we did not feel apart. We supported each other. The outcome was very positive, and no one disputed it; on the contrary, it was one of the most valued interventions in that context. The rector could legitimately have made a different decision there, for example, by considering the intervention as too daring and risky. This did not happen; we took the risk, and the result, also compared to my expectations, to my previous experience, was excellent.”

As the third trait of entrepreneurial orientation, the strategy was characterized by a high level of proactiveness in that the rector demonstrated an initiative-driven leadership to improve various aspects of the university and the overall environment. On campus, “we understood that we were attracting a diverse international community at the University of Bergamo, and well before English became the campus’s common language, I spearheaded the initiative to provide indications and signage in English on campus. This simple but effective change made the university more welcoming and accessible to international students and staff, fostering a sense of inclusivity and creating positive impressions of the institution.” The introduction of English not only one campus signs but also in the education curriculum was described by the Managing Director as “an element of strong historical discontinuity. I remember the effort made by the Polytechnic of Milan to offer degrees taught only in English, which raised legislative conflicts. The rector avoided these forcings but accompanied the transformation.” The Managing Director recognized the proactiveness of the rector’s “willingness to accept others’ ideas, even when different from his own. He listened to the people.” In this regard, the rector says “I followed the advice of a professor of Physics, who proposed the ‘Beautiful Campus’ initiative, aimed to enhance the aesthetics and functionality of the technological campus. Originally modern and aseptic, the campus has become a science-oriented and conducive environment for research and innovation.” Out of campus, the rector says, “I took the initiative to engage with the city authorities and propose the idea of putting up indications for the universities. In the absence of clear signage, it was challenging for visitors and newcomers to navigate the city and locate different university campuses. By collaborating with the municipality, we successfully implemented a comprehensive system of indicators for university campuses, making it easier for students, faculty members, and visitors to find their way around the campus. This was one of the first steps taken by the municipality in the direction of declaring Bergamo a ‘University City’.”

Finally, individual behavior is the last component of CES that emerged at the University of Bergamo. The role of entrepreneurial alertness, namely, the capability to recognize opportunities, is pivotal to the success and growth of any institution. “As the rector, I valued the contributions and ideas of the staff members and recognized that their expertise and dedication were essential for achieving our strategic objectives. In 2012, one of our researchers visited Harvard for a one-year visiting grant from the Radcliff Institute. She managed to grant me a visit and meet with a number of academics, a visit that I enjoyed with a few key collaborators, and allowed me to start off a collaboration that is still in place today, and has had an enormous impact on the Bergamo region, where a collaboration with such a prestigious institution has been perceived as one of the greatest institutional achievements of those times.” “Other ideas were always considered. Even at the moment of decision, a door was always left open, a word dedicated to letting an idea pass,” confirmed the Managing Director.

The rector of the University of Bergamo also identified the relevance of his own self-efficacy. “My age – I became a rector at the age of 44 – and prior experience as a water polo player in the Italian first league, played a significant role in shaping my leadership style and influencing how I was perceived by others as the Rector of the University of Bergamo. My relatively young age made me more relatable and approachable to students and younger faculty members. Being a former water polo player in the Italian First League has allowed me to serve as a role model and inspiration for students and faculty members. My sports background exemplified qualities such as teamwork, discipline, and leadership, which are valuable attributes in both sports and academia.” The rector was an example for students. “He was a rector loved and followed by students. Students made a qualitative leap in how they experience university. For every decision, student representatives were consulted. He has generated a sense of belonging,” clarified the Managing Director.

Last, the ability to ground a project, namely entrepreneurial effectuation capability, was a crucial process for the rector to operate the transformation of a public organization like a university: “I reckon I was perceived as a person capable of grounding projects. Take the most difficult goal we had, namely, the implementation of master’s degrees entirely taught in English. To ensure the successful implementation of this project, key stakeholders were involved in the decision-making process, including faculty members, academic administrators, and student representatives. Their input and support were vital for identifying suitable programs, defining language requirements, and addressing potential challenges. Several local institutions had severe issues in this process, while we made it, and it was quick. The introduction of a master’s degree in English showcased the university commitment to global education and innovation. We actively engaged local stakeholders, including donors, friends, and supporters, in the project’s development and implementation. We gained enthusiastic support and involvement by sharing the vision and benefits of the initiative. We even had to solve issues such as dealing with donations to the university, which was not common at that time.” By grounding challenging projects, such as the introduction of master’s degrees in English, with careful planning, collaboration, and engagement with stakeholders, the University of Bergamo was able to position itself as a dynamic and forward-looking institution. This strategic approach not only enhanced the university’s reputation but also fostered a sense of pride and enthusiasm among donors, friends, and supporters, who were happy to be associated with a university capable of making bold and meaningful changes to meet the demands of a globalized world”. In the view of the Managing Director, this was due to the ability of the Rector to “dialogue with institutions, influencing the opinion of leaders and businesses. He became an interlocutor at the same level, if not superior, to other institutions. He made the university credible by virtue of his own credibility.” (See Table 3).

2.5.2 Outcomes

To complete our framework, we focused on the outcomes generated by the University of Bergamo as a whole.

The most striking finding was that university was perceived as a renewed entity. The successful implementation of a light, open, and competitive (LOC) strategy at the University of Bergamo had a transformative impact, leading the university to being perceived as a new institution that embraced innovation, excellence, and financial sustainability. From a financial perspective, the rector believed that the strategy prioritized efficiency and streamlined administrative processes, leading to improved financial sustainability: “By optimizing resource allocation and embracing cost-effective measures, the university’s financial health improved significantly. This positive trajectory was evident in its ability to attract more students, which contributed to increased tuition revenue. Additionally, the successful fundraising activity played a crucial role in securing external funding and support from donors and supporters, further bolstering the university’s financial position.” The rector also turned to the students to make the university financially sustainable. The Managing Director illustrated how “the university encountered periods in which infrastructural problems had to be resolved. Students were asked to contribute through higher tuition. This was proposed to them and explained; these were difficult steps. We experienced the rector’s ability to make them perceive that a greater good was at stake, for the university, for themselves, and for the students who would come later. The greater good justified the efforts required. The student representatives conveyed this message to their colleagues.”

However, what was most effective is the perception that the university had increased its public value performance. According to an instrumental-utilitarian perspective of value, the rector pointed out that “the University of Bergamo had significantly enhanced its role as a public institution dedicated to creating value for society. Universities contribute to social progress and economic development by promoting academic excellence, research advancement, and innovation. The university partnerships with industries and local communities also facilitated knowledge transfer and technology commercialization, further reinforcing its reputation as a dynamic and socially engaged institution.” From a hedonistic-aesthetic point of view, the successful implementation of our strategy elevated the university reputation at both national and international levels. This success in reputation was both at a personal level for the rector, and at the institutional level for the University of Bergamo: “Consequently, I was nominated to serve in leadership roles that were unusual for a rector coming from a somewhat average university. First, being appointed as general secretary of the Italian Conference of Rectors (CRUI) displayed recognition from my peers within the Italian higher education system. Being elected President of the CRUI was a testament to the trust and confidence placed in my leadership abilities. Additionally, my appointment to the board of the European University Association (EUA) demonstrated recognition at the European level, allowing me to contribute to discussions and decisions that impacted higher education across the continent.” “The success in reputation directly influenced the University of Bergamo’s position and capabilities. The university hosted major events, such as world conferences (e.g., the first European edition of the World Conference of the Technology Transfer Society in 2012 or the World Conference of the Air Transport Research Society in 2013) and European forums (e.g., the Funding Forum of the European University Association in 2014). This was a direct result of an improved reputation and increased visibility in the academic community.” These high-profile events not only highlighted the university academic excellence and research capabilities, but also allowed for valuable networking opportunities with scholars, researchers, and experts worldwide. Hosting such events contributed to the university’s internationalization efforts and bolstered its position as a prominent institution in the academic and research arenas.

The Managing Director concluded that “the University of Bergamo was cleared by customs in the territory. This was a real leap, merely progression. I have always said this, both to the rector and to other people at the university. At the end of his mandate, the university was overestimated.” (See Table 4).

2.5.3 Concluding remarks

In conclusion, this study highlights the significance of implementing the CES within the challenging context of the University of Bergamo, as a corporate entrepreneurship strategy can empower universities to thrive even in inflexible contexts (Sadler, 2000). Our discussion underscores the three essential pillars driving the success of this strategy.

First, the pivotal role of people (Hornsby et al., 2002) both within and outside the university, cannot be overstated. A visionary leader (Kreiser et al., 2021; Kuratko et al., 2005), complemented by dedicated and innovative staff, forms the bedrock of entrepreneurial culture. Collaborative efforts and the willingness to embrace change (Dayan et al., 2016) foster transformative initiatives that propel the university towards growth and excellence. Second, unfavorable environments, such as a weak, young, or enclosed university, can paradoxically serve as catalysts for entrepreneurship when viewed as opportunities rather than obstacles. Embracing these challenges enables creative and effective solutions, reinforcing the notion that constraints fuel innovation (Kearney & Morris, 2015). Third, a leader entrepreneurial orientation (Kreiser et al., 2020) plays a decisive role in repositioning the university. By demonstrating calculated risk-taking, proactivity, and innovative approaches (Anderson et al., 2015; Covin & Slevin, 1991), the leader inspires the entire institution to evolve, adapt, and flourish. Furthermore, the personal attributes of the leader (Qian & Acs, 2013), informed by prior experiences such as sports, contribute significantly to their ability to instigate and drive change. Traits such as self-esteem, determination, and resilience (Kearney & Meynhardt, 2016) inspire confidence and trust among stakeholders and foster a unified and motivated team that strives to achieve excellence.

This study aims to test a comprehensive theoretical framework of CES in the public sector and demonstrate that the entrepreneurial attitudes of universities can emerge in several forms (Guerrero & Urbano, 2012), other than the most traditional (and largely investigated), such as technology transfer, academic spinoffs, patents, and incubators (Nielsen, 2015; O’Shea et al., 2008; Rasmussen & Wright, 2015; Siegel & Wright, 2015; Wu et al., 2021). Our study contributes to entrepreneurial literature by showing a new strategic approach that can foster innovation, adaptability, and financial sustainability, thereby positioning the university for sustained growth and success. The case of the University of Bergamo exemplifies the potential for repositioning and achieving excellence through a corporate entrepreneurship strategy. By capitalizing on the entrepreneurial mindset (Kuratko et al., 2021), leveraging the capabilities of the university’s staff, and employing effective leadership strategies, the university redefines its trajectory amidst the challenges posed by the external environment. In conclusion, this study serves as a testament to the transformative power of corporate entrepreneurship and urges universities to embrace a dynamic and forward-thinking approach to create a brighter and more impactful future in the changing landscape of higher education.

2.6 Limitations and Future Research

A single case study approach can be useful for social scientists who aim to address social problems coming from contexts other than the one analyzed here, but still somehow ascribable to it (Barzelay, 1993). Nevertheless, if one wants to replicate across several separate instances, a multi-case study approach is recommended (Yin, 2009). In our case, the adoption of a multiple case study analysis allowed us to investigate the differences in CES between public and private universities. Private universities are thus in the middle between the private and public spheres, and in Italy, they are characterized by a different statute, enjoying more autonomy and freedom of action. Therefore, private Italian universities are expected to be more entrepreneurial than their public counterparts. Consequently, it would be interesting to compare the effect of entrepreneurial leadership in the two typologies and investigate the impact of some specificities in the internal and external environments that may lead to different results. If we assume that contingencies play a role in CES design and implementation, multi-case studies create the opportunity to analyze the eventual divergences of universities located in the same context. The University of Bergamo is in Lombardy, along with the University of Milan, Polytechnic of Milan, the University of Brescia, and Insubria University (in Varese) among others. The identification of the peculiarities of each university that are not related to the geographical position explains different levels of entrepreneurial leadership and CES adoption. On the other hand, comparing similar universities located in completely different contexts would shed light on the features of the Italian HE system that make the difference. An interesting international example would be the University of Augsburg, which shares with Bergamo the proximity to a big city (i.e., Munich) and the peripheral and isolated condition that such proximity creates. However, in Germany and Italy, leadership is elected through different mechanisms, and university autonomy, governance, and financing are dissimilar. Insightful results may, therefore, follow.

If one is engaged in finding systematic differences within or cross countries, a statistical analysis would be more suitable. Regressions allow for the detection of variability in leadership effectiveness with reference to organizational performance, social impact, and sustainability. Thus, these outputs are fundamental to the creation of public value, which should be the basis of public organizations’ missions (Klofsten et al., 2019). Quantitative statistical analyses have the advantage of providing results that can be generalizable and concurring to create standard measures that can be adopted and tested internationally. Leadership effectiveness in different organizations, within the public sector, and in different countries can be measured and tested using this methodology.

Our analysis provides several insights from a theoretical perspective. Entrepreneurial leadership does not exist in a vacuum. One of the biggest limitations of approaches like ours according to Currie et al. (2008) is to portray CES as a individualistic, “heroic” action. It is mostly due to the fact that we have interviewed the one at the apex of the organization. Bryman (2004) posits that formal leaders may overly attribute strategic changes to the effects of their own leadership actions. CES is also the expression of internal norms, values, and climate resulting from interaction with members internal to the organization (Guerrero & Urbano, 2012; Klofsten et al., 2019). In Italian public universities, faculty and decision-making bodies play a role in influencing CES by virtue of their relationships with leadership. Leadership is elected from among full professors at the same university (Civera et al., 2021). Therefore, the extent of entrepreneurial leadership may depend on the entrepreneurial spirit that is widespread among faculty members. Simultaneously, according to the Gelmini reform, leadership is limited in its autonomy by the academic senate and board of directors (Civera et al., 2021). The interaction between these two stakeholders deserves special attention when documenting the internal power balance process (Civera et al., 2023).

Similarly, an internal stakeholder that is mostly neglected is represented by the student body. Analyzing the CES in view of students’ mindset development may include teaching and learning activities as well as the direct involvement of students in entrepreneurial outputs and ecosystems, by, for instance, reaching out to local communities or integrating entrepreneurial curricula in the university educational offer (Guerrero & Urbano, 2012; Klofsten et al., 2019).

Therefore, further research is needed to better understand the effects of leadership on CES. We suggested several venues for future research on this topic.

Notes

Universities sharing a similar condition in Italy may be the University of Modena e Reggio Emilia, the University of Piemonte Orientale and the University of Insubria. Abroad, the University of Augsburg experiences the same relationship with the Technical University of Munich and the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

References

Acs, Z. J., Audretsch, D. B., & Lehmann, E. E. (2013). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 41(4), 757–774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9505-9.

Ahlin, B., Drnovšek, M., & Hisrich, R. D. (2014). Entrepreneurs’ creativity and firm innovation: The moderating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Small Business Economics, 43(1), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9531-7.

Anderson, B. S., Kreiser, P. M., Kuratko, D. F., Hornsby, J. S., & Eshima, Y. (2015). Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 36(10), 1579–1596. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2298.

Andrews, R., Boyne, G. A., Law, J., & Walker, R. M. (2005). External constraints on local service standards: The case of comprehensive performance assessment in english local government. In Public Administration (Vol. 83, Issue 3, pp. 639–656). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-3298.2005.00466.x.

Andrews, R., Boyne, G. A., Law, J., & Walker, R. M. (2011). Strategy implementation and public service performance. Administration and Society, 43(6), 643–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399711412730.

Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2017). Entrepreneurial ecosystems in cities: Establishing the framework conditions. Journal of Technology Transfer, 42(5), 1030–1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-016-9473-8.

Barzelay, M. (1993). The single case study as intellectually ambitious inquiry. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 3(3), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473915480.n70.

Bernier, L., & Hafsi, T. (2007). The changing nature of public entrepreneurship. Public Administration Review, 67(3), 488–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00731.x.

Bleiklie, I., Enders, J., Lepori, B., & Musselin, C. (2011). NPM, network governance and the university as a changing professional organization. In The Ashgate Research Companion to New Public Management (pp. 161–176). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315613321-19.

Brunsson, N., & Sahlin-Andersson, K. (2000). Constructing organizations: The example of public sector reform. Organization Studies, 21(4), 721–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840600214003.

Bryman, A. (2004). Qualitative research on leadership: A critical but appreciative review. Leadership Quarterly, 15(6), 729–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.09.007.

Carnes, C. M., Gilstrap, F. E., Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., Matz, J. W., & Woodman, R. W. (2019). Transforming a traditional research organization through public entrepreneurship. Business Horizons, 62(4), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2019.02.002.

Cattaneo, M., Malighetti, P., Meoli, M., & Paleari, S. (2017). University spatial competition for students: The Italian case. Regional Studies, 51(5), 750–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2015.1135240.

Cattaneo, M., Civera, A., Meoli, M., Paleari, S., & Seeber, M. (2020). Universities’ tuition fee setting under competitive pressure. Evidence from the Italian experience across the financial crisis

Cheng, S. (2014). Executive compensation in Public Higher Education: Does performance matter? Research in Higher Education, 55(6), 581–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-014-9328-9.

Civera, A., Meoli, M., & Vismara, S. (2019). Do academic spinoffs internationalize? Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(2), 381–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9683-3.

Civera, A., Meoli, M., & Vismara, S. (2020). Engagement of academics in university technology transfer: Opportunity and necessity academic entrepreneurship. European Economic Review, 123, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2020.103376.

Civera, A., Meoli, M., & Paleari, S. (2021). When austerity means inequality: The case of the Italian university compensation system in the period 2010–2020. Studies in Higher Education, 46(5), 926–937. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.1896800.

Civera, A., D’Adda, D., Meoli, M., & Paleari, S. (2023). The political power of the Italian rectors. An analysis of recruitments in the period 2001–2021. In Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2260420.

Colombelli, A., De Marco, A., Paolucci, E., Ricci, R., & Scellato, G. (2021). University technology transfer and the evolution of regional specialization: The case of Turin. Journal of Technology Transfer, 46(4), 933–960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-020-09801-w.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1991). A conceptual model of Entrepreneurship as Firm Behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879101600102.

Crosby, B. C., & Bryson, J. M. (2018). Why leadership of public leadership research matters: And what to do about it. Public Management Review (Vol, 20, 1265–1286. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1348731.

Cunningham, J. A., Menter, M., & Young, C. (2017). A review of qualitative case methods trends and themes used in technology transfer research. Journal of Technology Transfer, 42(4), 923–956. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-016-9491-6.

Currie, G., & Brown, A. D. (2003). A narratological approach to understanding processes of organizing in a UK hospital. In Human Relations (Vol. 56, Issue 5, pp. 563–586). https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726703056005003.

Currie, G., & Procter, S. J. (2005). The antecedents of middle managers’ strategic contribution: The case of a professional bureaucracy. Journal of Management Studies (Vol, 42, 1325–1356. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00546.x.

Currie, G., Humphreys, M., Ucbasaran, D., & Mcmanus, S. (2008). Entrepreneurial leadership in the English public sector: Paradox or possibility? Public Administration, 86(4), 987–1008. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.00736.x.

Dayan, M., Zacca, R., Husain, Z., Di Benedetto, A., & Ryan, J. C. (2016). The effect of entrepreneurial orientation, willingness to change, and development culture on new product exploration in small enterprises. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 31(5), 668–683. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-02-2015-0023.

De Silva, M., Al-Tabbaa, O., & Pinto, J. (2023). Academics engaging in knowledge transfer and co-creation: Push causation and pull effectuation? Research Policy, 52(2), 104668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2022.104668.

Donina, D., & Hasanefendic, S. (2019). Higher Education institutional governance reforms in the Netherlands, Portugal and Italy: A policy translation perspective addressing the homogeneous/heterogeneous dilemma. Higher Education Quarterly, 73(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12183.

Donina, D., Meoli, M., & Paleari, S. (2015a). The new institutional governance of Italian state universities: What role for the new governing bodies? Tertiary Education and Management, 21(1), 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2014.994024.

Donina, D., Meoli, M., & Paleari, S. (2015b). Higher education reform in Italy: Tightening regulation instead of steering at a distance. Higher Education Policy, 28(2), 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2014.6.

Ferlie, E., Musselin, C., & Andresani, G. (2008). The steering of higher education systems: A public management perspective. Higher Education, 56(3), 325–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9125-5.

Fini, R., Grimaldi, R., Santoni, S., & Sobrero, M. (2011). Complements or substitutes? The role of universities and local context in supporting the creation of academic spin-offs. Research Policy, 40(8), 1113–1127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.05.013.

Fisher, G. (2012). Effectuation, causation, and bricolage: A behavioral comparison of emerging theories in entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 36(5), 1019–1051. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00537.x.

Grimaldi, R., Kenney, M., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2011). 30 years after Bayh-Dole: Reassessing academic entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 40(8), 1045–1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.04.005.

Guerrero, M., & Urbano, D. (2012). The development of an entrepreneurial university. Journal of Technology Transfer, 37(1), 43–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-010-9171-x.

Hayter, C. S. (2011). In search of the profit-maximizing actor: Motivations and definitions of success from nascent academic entrepreneurs. Journal of Technology Transfer, 36(3), 340–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-010-9196-1.

Hornsby, J. S., Kuratko, D. F., & Zahra, S. A. (2002). Middle managers’ perception of the internal environment for corporate entrepreneurship: Assessing a measurement scale. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(3), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00059-8.

Hornsby, J. S., Kuratko, D. F., Shepherd, D. A., & Bott, J. P. (2009). Managers’ corporate entrepreneurial actions: Examining perception and position. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(3), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.03.002.

Ireland, R. D., Covin, J. G., & Kuratko, D. F. (2009). Conceptualizing corporate entrepreneurship strategy. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 33(1), 19–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00279.x.

Kearney, C., & Meynhardt, T. (2016). Directing corporate entrepreneurship strategy in the Public Sector to Public Value: Antecedents, components, and outcomes. International Public Management Journal, 19(4), 543–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2016.1160013.

Kearney, C., & Morris, M. H. (2015). Strategic renewal as a mediator of environmental effects on public sector performance. Small Business Economics, 45(2), 425–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9639-z.

Kearney, C., Hisrich, R. D., & Roche, F. (2009). Public and private sector entrepreneurship: Similarities, differences or a combination? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 16(1), 26–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000910932863.

Kearney, C., Hisrich, R. D., & Roche, F. W. (2010). Change management through entrepreneurship in public sector enterprises. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 15(4), 415–437. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946710001646.

Klofsten, M., Fayolle, A., Guerrero, M., Mian, S., Urbano, D., & Wright, M. (2019). The entrepreneurial university as driver for economic growth and social change - key strategic challenges. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 141, 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.12.004.

Komljenovic, J. (2022). The future of value in digitalised higher education: Why data privacy should not be our biggest concern. Higher Education, 83(1), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00639-7.

Kreiser, P. M., Anderson, B. S., Kuratko, D. F., & Marino, L. D. (2020). Entrepreneurial orientation and environmental hostility: A threat rigidity perspective. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 44(6), 1174–1198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258719891389.

Kreiser, P. M., Kuratko, D. F., Covin, J. G., Ireland, R. D., & Hornsby, J. S. (2021). Corporate entrepreneurship strategy: Extending our knowledge boundaries through configuration theory. Small Business Economics, 56(2), 739–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00198-x.

Kuratko, D. F., Ireland, R. D., Covin, J. G., & Hornsby, J. S. (2005). A model of middle-level managers’ entrepreneurial behavior. Entrepreneurship: Theory and practice (Vol. 29, pp. 699–716). SAGE PublicationsSage CA. 6https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00104.x. Los Angeles, CA.

Kuratko, D. F., Covin, J. G., & Hornsby, J. S. (2014). Why implementing corporate innovation is so difficult. Business Horizons, 57(5), 647–655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2014.05.007.

Kuratko, D. F., Fisher, G., & Audretsch, D. B. (2021). Unraveling the entrepreneurial mindset. Small Business Economics, 57(4), 1681–1691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00372-6.

Lam, A. (2011). What motivates academic scientists to engage in research commercialization: ‘Gold’, ‘ribbon’ or ‘puzzle’? Research Policy, 40(10), 1354–1368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.09.002.