Abstract

To observe changes in three clients with intellectual disabilities and severe behavioral problems and staff in a long-term care residential facility after redesigning the clients’ rooms by making them more personal and homely, adjusting the amount of stimuli, changing the layout, connecting to the outdoor area, and using high-quality natural materials. Relatively many clients with intellectual disabilities exhibit severe problem behaviors, including self-harm, aggression toward others, and repeated destruction of their own rooms, which can eventually result in a barren, inhumane living environment. Research on these clients is limited. Data were collected in a mixed methods study in which quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed. After the redesigns, positive changes were observed in the well-being and behavior of all three clients, for example, with respect to quality of life, privacy, freedom of choice, problem behavior, mood, cognition, activities of daily living, leisure activities, social behavior, self-harm, and constraints. There were no changes in the use of psychotropic medication. Quality of life scores increased in two cases, but were significant in only one. Emotional and behavioral problem scores decreased significantly in two cases, but in only one case these results were maintained at follow-up. Staff experienced a more pleasant, safe, and functional work environment, with improved provision of indicated care and interaction. Absenteeism decreased significantly in two of the three cases. Redesigning clients’ rooms could potentially be a promising intervention for clients with intellectual disabilities and severe chronic behavioral problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Relatively many clients with intellectual disabilities (16% - 20% known to services) exhibit problem behavior (also called challenging behavior or behaviors that challenge), including self-harm, aggression toward others, and destruction of the physical environment (Bowring et al., 2019). To protect them from self-harm, to ensure a safe and workable situation for staff, and to prevent destruction of the physical environment, the emphasis in client care and in the design of living spaces, such as the client's own room, is usually on providing safety, control, and efficiency, resulting in a low-stimulus environment, restricted access to certain areas or materials, sturdy furniture, safe and molest-resistant materials, easy-to-clean surfaces, and few personal items (Roos et al., 2022b). In cases with chronic and severe behavioral problems, a prolonged process of repeated destruction of the client’s own room (belongings, as well as walls, floors, bathrooms), with gradual removal of more and more materials for fear of further (self) harm by the client or risky situations for the staff, may eventually result in a barren or even inhumane living environment.

Reviews show that few studies have been conducted on the impact of the physical environment on individuals with intellectual disabilities, for example, with respect to housing types, safety, and homelikeness (Casson et al., 2021; Karol & Smith, 2019; Roos et al., 2022a). Almost no studies have been found on the impact of the physical environment on individuals with intellectual disabilities combined with severe behavioral problems in long-term care facilities (Mueller-Schotte et al., 2022; Roos et al., 2022b). There is one known case where a healthcare facility gave a damaged room of such a client a total makeover in collaboration with an architect because of her knowledge of the impact of the physical environment on users and to look at the situation with a fresh perspective (see “Dolf’s room”, Leuenberger & Möhn, 2022; Möhn, 2021). After the personalized redesign, there were positive changes in both the client (for example, less destructive behavior and self-harm) and the staff (for example, less anxiety and absenteeism) (Möhn, 2021).

There are several reasons why the gap in knowledge needs to be filled. First, the influence of the physical environment may be of particular importance to these clients. An intellectual disability (ID) can lead to limitations in many areas, such as performing daily living activities (for example, washing, dressing, going to the toilet), regulating stimuli and emotions, communicating, making choices, and overseeing and understanding situations. The more severe the disability, the greater the need for (constant) support. It is hypothesized that a physical environment that does not meet the needs arising from these limitations, such as the need for overview, stimulus reduction, constant contact possibilities with caregivers, safety, and easy-to-understand pathways, leads to anxiety and stress, putting people at risk of developing problem behaviors. Second, it is important to determine whether physical features can help reduce behavioral problems and create a humane living environment, thereby improving the quality of life of clients with severe chronic conditions. This is all the more important because these clients often spend their entire lives in long-term care. Third, organizational factors such as staff turnover can have a negative effect on clients’ problem behavior (Olivier-Pijpers et al., 2020). Especially on wards for clients with severe risk behavior where (aggressive) incidents occur regularly, there is often a staff shortage and high turnover; the work is demanding and stressful, there is a high workload, and staff often experience unsafety, leading to frequent absenteeism. Knowing more about what physical features can improve the work environment of staff could potentially contribute to more stable staffing levels. Also, reducing clients' problem behavior by adapting the physical environment could contribute to a safer and thus more attractive work environment for staff.

Because of the promising outcomes regarding “Dolf’s room”, the rooms of three clients with severe chronic behavioral problems were redesigned to see if this result could be replicated. The redesigns were studied by close examination of the clients’ behavioral problems, preferences and needs, the appearance of the room before and after the redesign, and changes in the clients’ well-being and behavior after the redesign. Given the experience with Dolf, the study also includes the experiences of staff regarding their work environment and the absence of direct caregivers. The research question was: what changes, if any, regarding clients and staff occur after redesigning barren rooms of clients with ID and severe behavioral problems in a long-term care facility?

Methods

Study Design

The study was conducted using a case study approach (Kratochwill & Levin, 2014) describing each client’s behavioral problems before and after the intervention for three single cases. Because the three rooms were already completed when the study began, the cases were examined primarily retrospectively through file analysis. In addition, a semi-structured interview was conducted with staff members, including caregiver, manager, and psychologist, reflecting the “current” situation twelve months after the redesign.

Setting

The redesign of the rooms took place at several sites of a facility (Ipse de Bruggen, The Netherlands) that provides long-term care for clients with ID. These are closed units that provide 24/7 residential care and individual supervision for six to nine clients with severe behavioral problems and resulting complex and intensive care needs. Each unit consists of a living room, kitchen, and garden. Each client has their own room with sanitary facilities. The redesigns took place in 2020 and 2021.

Participants

An intellectual disability (ID) is defined as limitations in both intellectual and adaptive functioning in the conceptual, social, and practical domains, beginning during the developmental period (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and divided into four severity categories: mild (IQ 50–69), moderate (IQ 35–49), severe (IQ 20–34), and profound ID (IQ < 20). Three adult clients with ID (one moderate ID, two severe ID) participated in the room redesign project. They exhibited severe and high-risk behavioral problems that caused harm to the client himself, the staff, and the living environment. Because of their low level of emotional, adaptive, and intellectual functioning, they needed constant support and (close) supervision. They received many years of intensive care, with many interventions for their problem behavior, such as therapy, individual activities, constant supervision, strict daily schedules, psychotropic medication, and restrictions, which did not further improve their functioning. Clients were admitted by the project's steering committee if there appeared to be little prospect of further development and their room had deteriorated over the years to the point of distress.

Because of the clients' low level of functioning and the resulting limitations, they were not additionally burdened by the study. Instead, their case files were analyzed and staff members were interviewed. Because the clients were incompetent to represent their own interests, written consent for the study was obtained from their legal representatives after they were fully informed about the aims of the study both orally and in writing. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institution’s Ethics Committee. For privacy reasons, names are fictitious and places of living units and sites are not disclosed.

Intervention

The intervention consisted of redesigning the clients' rooms in close collaboration with an architect. Although the old rooms differed for each client, all designs were based on six guiding principles, which were then elaborated on by client. First, by focusing not only on the problems and resulting needs, but also on the client as a person (interests, preferences, background), all the rooms were made more personal, as in the case of Dolf (Leuenberger & Möhn, 2022; Möhn, 2021). Second, the atmosphere was improved, making the rooms feel more homelike. Research on individuals with ID associates homelikeness with less stereotypical behavior, less aggression, more positive staff-to-resident interactions, and more involvement in household tasks (Egli et al., 2002; Thompson et al., 1996), although these studies did not specifically focus on clients with severe behavioral problems. Third, more stimuli were added to the rooms. When a client cannot cope well with stimuli, there is often a tendency to reduce them. However, an environment with too few stimuli can lead to boredom and thus destruction. The designs included more stimuli (for example, color, items, furniture), but took personal preferences into account. Research on individuals with ID shows that more variety and stimulation is associated with better adaptive behavior (Heller et al., 1998), but again, this study did not specifically focus on clients with severe behavioral problems. Fourth, there were layout changes, such as changing the passageway to other rooms so staff could be closer to the client and placing the bed in a way that gave the client the most overview. Proximity to staff and need for overview meet the support needs of clients with low levels of emotional development (Došen, 2014). Fifth, in two cases the outdoor area was redesigned and more connection (view/access) to the outdoor area was created. The positive effect of connection to outdoor areas is known from research on dementia patients, but consequential effects such as more daylight, natural ventilation, and feeling less confined could also play a positive role (for example, Casson et al., 2021; Chaudhury et al., 2018). Sixth, natural materials were used. With these clients, it is important that materials can withstand rough handling or be repaired quickly. In the ID field, plastic or steel is used, which does not give a humane/homey feel. Choosing high-quality natural materials such as hardwood offered the desired molest-resistance, safety, and hygiene, but with a friendlier and warmer feel.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected by the first author (JR) in 2021 and early 2022 pertaining to three periods: approximately six months before redesign (t0), six months after redesign (t1), and twelve months after redesign (t2). The data related to t0 and t1 were all retrospectively collected.

Regarding the redesigns, information about and photographs of the (changes in the) room were obtained from project files. The architect and second author (AM) described the redesigns, which were verified by the main researcher by juxtaposing them with information from the files and visits to the rooms. Staff interviews covered the current state (t2) of the redesigned room.

Clients’ files were reviewed, which contained qualitative information on (changes in) client characteristics, diagnosis, well-being, behavior, and medication use described by the psychologist in treatment plans and evaluation reports. These are based on daily observations and notes from direct caregivers and medical information. Project files were searched for redesign goals, and the staff interviews discussed observations of staff regarding the current status (t2) of and changes in clients’ well-being and (problem) behaviors, and achievement of the redesign goals as noted in the project files. The qualitative client data were checked for any inaccuracies by the psychologist and manager involved with the client in question and categorized by outcome variables. For this purpose, the framework of a scoping review on the impact of the built environment in long-term care was used (see Roos et al., 2022a), with a slight modification (eating and sleeping were included under activities of daily living and goal attainment was added). This framework defines clusters of outcome variables related to health, behavior, and quality of life. Clustering was based on the aggregation of synonyms and integration of matrices in the reviews the authors found, keeping as broad a list as possible with as little overlap between clusters as possible (Roos et al., 2022a).

Client files also included quantitative data from staff-administered instruments on quality of life (San Martin Scale [SMS]; Verdugo et al., 2014) and emotional and behavioral problems (Developmental Behaviour Checklist – Adults [DBC-A]; Mohr et al., 2004, 2011) before and after the redesign. For SMS, higher scores mean higher quality of life. For DBC-A, the higher the score, the more severe the problem behavior. The quantitative client data were analyzed by the first and third author (AP) using the Reliable Change Index (Jacobson & Truax, 1991) with respect to total scores (Quality of Life Index and Total Behavior Problem Score). Relevant indices from the manuals: regarding Quality of Life Index, reliability score (internal consistency Cronbach’s α) = 0.97 and standard deviation score = 15. Regarding Total Behavior Problem Score, reliability score (test–retest reliability – paid carers) = 0.75 and standard deviation scores = David 19.4 (50+ , Mild ID), Samira 20.7 (50+ , Severe & Profound ID), Robert 20.7 (50+ , Severe & Profound ID).

Regarding staff, project files were reviewed and interviews were conducted with staff (two per case) about their experiences with the room redesign and perceived changes in work environment, provision of care, and staffing after the redesign. The qualitative staff data were checked for any inaccuracies by the psychologist and manager involved with the team in question.

From the organization's data system, absence rates of direct caregivers were extracted during t0, t1 and t2. The absence rate is the total number of employee sick days expressed as a percentage of the total number of available (work/calendar) days of employees during the reporting period. The absence rates were analyzed by the first and third author using average rates, baseline trends, visual inspection of graphs, and effect size calculation using non-overlap techniques (‘Tau for nonoverlap with baseline trend control’ [Tau-U]; Parker et al., 2011). A level of 0.05 was used as the threshold for statistical significance in the calculations.

Subjects and Redesigns

David

David was a 51-year-old (at the time of redesign) man with moderate ID, autism spectrum disorder, attachment problems, and bipolar disorder. He showed social and contact deficits, rigid behavior patterns, anxiety, and mood swings with manic periods and periods of depression. In good times, he came regularly to the common areas, had some basic adaptive skills, and participated in activities with the staff. He did not engage in leisure activities in his room. When he was depressed, he was alone in his room most of the time and needed more help with daily living activities. For example, he was incontinent, ate poorly, and there were sleep problems: he wandered around at night, sometimes sleeping on the floor or standing upright in one place for a night, so that his feet were swollen in the morning. He showed aggression (verbal, physical), self-harm, and destructive behavior causing him to (compulsively) organize and destroy materials in his room. He destroyed bed, floor, television, and loose items in his room, drew on the walls, and bit into corners of the walls (1). He did not seem interested in the state of his room., but he was attached to his old photographs. David's room became more and more barren over time (2). Only a bed remained, which was fixated to the floor. It was difficult to keep the room clean.

In a conversation with the architect about his wishes for the redesign of his room, David indicated that he loves nature and the color green, that his bed is important to him, and that he would like to have a television. The idea arose to create a calming environment with natural materials for David. From a selection of five forest motif photographs, David chose his favorite, which was used to cover a long wall (photo wallpaper). This photo wall incorporated a television, which he could watch from his bed (3). Another wall, not visible from the bed so that he would not be disturbed by it when he wanted to sleep, was covered with a chalkboard. The window frames and other walls were painted light green with a type of paint that allows the surfaces to be kept clean easily. The corners of the walls were covered with solid ash wood, which is also used for children's toys and can be easily repaired when he bites into them (4). The bed was made of solid pine, which is known for its aromatic properties. A picture frame (protected by plexiglass) was hung with photographs that David himself had selected from his collection. His sister completed the furnishings with a comfortable armchair. Later, the staff added a clock and light green curtains (with a hanging system so they could be easily hung back when pulled off), which David himself had requested. David followed the redesign process closely and repeatedly asked if he could watch.

Samira

Samira was a 50-year-old (at the time of redesign) woman of Surinamese descent with severe ID due to Velo-Cardio-Facial (VCF) syndrome, which is associated with mental health and behavioral problems. She had communication limitations, mood swings, anxiety, and behavioral problems such as screaming, stereotyped behavior, compulsive behavior, attention seeking behavior, withdrawn behavior, and physical aggression directed at others and objects. She hit herself with her fist on the eyes and nose and bit her hands. She often undressed as soon as she entered her room and then lay naked on the bed. The room's low-stimulus design and molest-resistant materials aimed at safety and preventing destruction (5). To prevent her from walking naked in the hallway, but not to completely cut off contact with staff and others, room and hallway were separated by a (locked) half door. This did not guarantee her privacy from passers-by. To make it impossible to look inside, the window in the outer wall was half covered with opaque film; however, this also prevented her from looking outside. From her room, she had no access to the garden (6). The room had a switch for the fluorescent lighting (which Samira herself did not use). The bathroom consisted of a stainless-steel toilet without a toilet seat, a stainless-steel sink, a fixed shower head (because of the destruction of loose shower heads), and lockable faucets (because of the unwanted opening of these).

Together with the staff and the therapist, the architect looked closely at Samira, her behavior, her stimulus processing, and her background. Information about what she liked and felt comfortable with emerged in several ways: through her family (information about the decor of her childhood home), by observing what clothes and shoes she liked to wear, and by trying out different things (for example, by placing pillows of different colors and materials in her room and observing which pillow she liked best). She showed a preference for pink, soft textures, and a Hindustani atmosphere. Also, she liked to be outdoors. A pink floor was laid, the walls were painted misty pink, and one wall in the bathroom was covered with pink mosaic tiles. The room was decorated with colorful soft pillows, pink bedding and colorfully painted flowers made of plaster (7). There was custom-made furniture made of solid cherry wood: a bed with wavy edges, a table with a bench, and a "cocoon" in which she could lie sheltered in her favorite position to give her a sense of security (8). The bed was placed against a wall so she could have an overview of her room and garden, and the cocoon was placed close to the window so she could look outside. In the bathroom, ceramic was used instead of stainless steel, and a toilet seat, a rain shower (because she loves this sensory experience), and a separate hand shower were installed. The old entrance door was closed, so Samira was no longer visible from the hallway. A connecting door in another wall to the staff room was installed instead. A private garden was created, surrounded by a willow hedge that reached to the tip of her nose, so that she could not be seen from the outside, but could look over it. The garden was accessed directly from her room through an added glass door in the exterior wall. The glass wall let in a lot of light. No longer was fluorescent lighting used, but lighting with dimmers. By showing her the progress, Samira was regularly involved in the redesign process.

Robert

Robert was a 57-year-old (at the time of redesign) man with severe ID due to oxygen deprivation at birth, and epilepsy. He was anxious, confused, felt unsafe, and suffered from rapidly changing moods. He had a strong will of his own and conflicts arose quickly. He exhibited severe problem behavior, such as screaming all day, passive behavior, agitated behavior, destructive behavior, and physical aggression directed at staff. His skills were deteriorating. He spent most of the day in his room, where he often defecated on the floor and smeared the faeces on the walls. He usually resisted wearing a diaper or taking a bath. His favorite theme was the royal family. He also liked to walk to the chapel and then pass by the statue of the Virgin Mary. Over the years, Robert's room became a barren and damaged space (9). Walls and doors were damaged, the television was built into a wall behind plexiglass. Adjacent was a small bathroom with stainless steel sink and toilet (10); for bathing, the (common) bathroom located further down the ward was used.

Regarding Robert's fascination with royalty, his mother said that as a child she took him to the Queen's ride in her golden carriage at the opening of Parliament. The importance of the royal family and Robert's connection to Mary were the main inspiration for the redesign of his room. A (heavy) chair made of solid oak was designed with a "crown" on the top, making the chair resemble a throne (11). The bed was made of the same type of wood and also had a crown as a backrest. The bed extended into a wooden lounge sofa perpendicular to it, with storage drawers at the bottom that could be slid open through a slot in the wood. The entrance door was painted gold, a cross hung above it, and on the wall hung a statue of the Virgin Mary in a gold box with bulletproof glass. Because Robert could not bear to see his own face reflected, the bathroom cabinet above the sink was painted gold, and instead of a television, a projector was attached to the ceiling that projects pictures or movies onto the white wall opposite the bed if desired. To facilitate cleaning, materials were used (paint, floor, furniture) that clean well and do not attract odors, and the chair had a removable seat. Robert's new room was the room next to his old room. Previously, a series of corridors connected these rooms to the living room. The partition wall was removed so that Robert's room was directly adjacent to the living room and there was a direct line of sight between Robert (bed) and the staff. One wall was replaced with a large window and a glass door that provided access to Robert's new private outdoor space. The bathroom had a gold-colored (ceramic) toilet, gold-colored mosaic tiles, and a synthetic floor with lightly shimmering gold flake mixture (12). The water points did not have protruding faucets because he would compulsively hit them. The water points were operated by staff through a control panel in the lockable cabinet.

Results

Qualitative Information Regarding Clients

Table 1 presents the information regarding staff-observed changes in clients at t1 and at t2 (follow-up). For all clients, positive changes were found with respect to quality of life, freedom of choice, problem behavior, mood, and activities of daily living. For two of the three clients, positive changes were found with respect to leisure activities, social behavior, health (self-harm), and constraints. For one client a positive change was found regarding privacy and for one client regarding cognition. Although in some cases there were (incidental) old behaviors, no negative changes were reported in any of the clients. There were no changes in the use of psychotropic medication in all clients at t2. No information was found on (changes in) participation in society, orientation, falls, psychiatric disorders, and apathy. As for redesign goals, three were found in the files for David, three for Samira and five for Robert (see Table 1). Almost all were considered achieved, except one for Robert.

Quality of Life and Behavioral Problems

Regarding David, between t0 and t2 the QOL Index (SMS, Fig. 13) significantly decreased (Table 2). This was mainly caused by the Personal Development and Social Inclusion subscales, which offset the increase in the Material Well-being subscale. The DBC-A (Fig. 14) shows that the TBPS decreased significantly at t1, which was partially reversed at t2 (Table 2), with the exception of the decrease in the Antisocial subscale. The aforementioned bad period seems reflected in the decrease in quality of life and a reversal of the initial decrease in emotional and behavioral problems. The increase in the Material Well-being subscale and the decrease in the Antisocial subscale seems consistent with the qualitative findings.

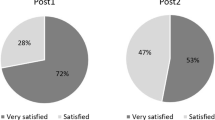

Regarding Samira, the QOL Index (SMS, Fig. 13) increased significantly after the redesign (Table 2), mainly caused by the subscales Self-Determination, Emotional Well-being, and Material Well-being. The initial increase in the Personal Development and Interpersonal Relationships subscales disappeared at t2. The DBC-A (Fig. 14) shows that the TBPS decreased significantly at t1, remained at t2, caused by almost all subscales (Table 2). The observed improvements are largely reflected in the increase in quality of life scores and decrease in emotional and behavioral problems scores. However, the lack of sustained improvement with respect to the Personal Development subscale does not seem to be consistent with the qualitative findings.

Regarding Robert, the QOL Index (SMS, Fig. 13) increased after the redesign (t2), but the difference was not significant (Table 2). However, there were significant increases with respect to the subscales Self-Determination, Physical Well-being, and Rights, but these were mainly offset by the decrease in the Material Well-being subscale. The DBC-A (Fig. 14) shows that the TBPS increased significantly, caused by almost all subscales (Table 2). The observed improvements are hardly reflected in the quality of life scores and emotional and behavioral problems scores. Regarding the intervention, a decrease in the Material Well-being subscale is notable.

Experiences of Staff

Table 3 presents the information regarding staff experiences with the room redesign and the perceived changes in (1) their work environment, (2) provision of care, and (3) staffing, between the periods before (t0) and after (t1 and t2) the redesign. All teams considered the new room more humane. Positive changes were perceived regarding the functionality of the rooms, sense of security for themselves, and the interaction among team members. An improvement was also perceived in awareness of the clients’ needs and in providing indicated care. For both team David and team Samira, no negative changes were reported. For team Robert, the use of temporary workers increased.

Staff Absence Rates

Regarding team David, the average absence rate after the redesign (3.2%) is lower than the average before the redesign (8.3%) and there is also a downward trend in absence rates after the redesign as opposed to the upward trend before it (Fig. 15). Data analysis showed that the difference between the phases is significant (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Regarding team Samira, there is a decrease in average absence rate during (from 11.0% to 9.4%) and after (to 4.0%) the redesign. The downward trend before the redesign flattens out during and after the redesign (Fig. 16). Data analysis showed that the difference between the phases during and after the redesign is significant (p = 0.0131), while the other differences (between before and during redesign, between before and after redesign) are not (p’s = 0.6889, 0.0927) (Table 4).

Regarding team Robert, the average absence rate increased after the redesign (4.7%) compared to before (1.9%) and during (1.5%) redesign, but the upward trend before the redesign turns into a downward trend during and after the redesign (Fig. 17). Data analysis showed that the differences between the phases are not significant (p’s = 0.5186, 0.1556, 0.2980) (Table 4).

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, we redesigned three rooms of clients with ID and severe behavioral problems in a long-term care facility, based on six guiding principles and clients’ preferences and needs, to see if there were subsequent changes in clients and staff. It can be concluded that observed well-being increased and problem behavior decreased both up to six months after the redesign and at follow-up one year after the redesign. Quality of life scores increased in two cases, but were significant in only one. Emotional and behavioral problem scores decreased significantly in two cases, but in only one case these results were maintained at follow-up. Here, the six guiding principles (i.e., personalization, homelikeness, attuned stimuli, layout with contact and more overview, connection to outdoor area, high-quality natural materials) may have influenced client’s and staff’s functioning and experiences because they meet the support needs of clients with ID. But possibly also because they contribute to basic human needs such as autonomy, control, choices, identity, dignity, privacy, and safety (Karol & Smith, 2019; Schalock & Verdugo, 2002), which are compromised in these clients due to the severity of their problems.

Staff experienced positive changes, such as a more pleasant, safe, and functional work environment, with improved provision of indicated care and collaboration. In two of the three cases, absenteeism decreased significantly. Since the study period fell during the COVID pandemic, which caused many healthcare workers to fall ill, it is noteworthy that absenteeism in two teams nonetheless decreased. It is possible that the improved work environment and therefore less stress among staff contributed to this. Reducing clients' problem behavior may also have contributed to less stress. This may have created a vicious cycle, whereby more stable teams in turn had a positive effect on the clients.

The study has a several limitations. First, although case studies are an important source for evidence-based practice (Schalock et al., 2011) and are especially appropriate in new topic areas (Eisenhardt, 1989), more cases are needed to gain greater certainty that the changes after redesign can plausibly be attributed to the intervention (Cope, 2015). At this time, other factors causing change could also be identified, for example, staff's reflective process on the client that the redesign entailed. Second, the interventions include a broad range of environmental features that were altered, leaving it unclear which features were associated with the changes. Third, clients or family members were not interviewed, so their perspective is lacking. Fourth, although the qualitative findings are largely consistent with the case of Dolf (Möhn, 2021), they do not always seem to be reflected in the measurement instruments. In particular, the contradictory findings about Robert raise questions: the observed improvements are hardly reflected in his scores for quality of life and emotional and behavioral problems. One reason could be that the information is not accurate because staffing was not stable (increasing use of temporary workers on team Robert) due to the COVID pandemic. Another reason could be that the instruments are too general and not sensitive enough to the specific individual changes brought about by the intervention. And fifth, this study was largely retrospective in nature, which meant we had to make do with the available data from case files.

In conclusion, although it is known that problem behaviors are often the result of interactions between the client and his (social) environment, the physical environment is not yet sufficiently highlighted in research and practice regarding clients with ID and severe chronic behavioral problems in long-term care. This study shows that the physical environment could be important and potentially a promising intervention. However, to discover potentially effective environmental features, more prospective cases with control situations are needed, with quantitative data analysis based on single- and small-case design methodology (What Works Clearinghouse, 2022).

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing

Bowring, D. L., Painter, J., & Hastings, R. P. (2019). Prevalence of challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disabilities, correlates, and association with mental health. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 6, 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-019-00175-9

Casson, J., Hamdani, Y., Dobranowski, K., Lake, J. K., McMorris, C. A., Gonzales, A., Lunsky, Y., & Balogh, R. S. (2021). Housing design and modifications for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities and complex behavioral needs: Scoping review. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 18, 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12377

Chaudhury, H., Cooke, H. A., Cowie, H., & Razaghi, L. (2018). The influence of the physical environment on residents with dementia in long-term care settings: A review of the empirical literature. The Gerontologist, 58(5), e325–e337. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw259

Cope, D. G. (2015). Case study research methodology in nursing research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 42(6), 681–682. https://doi.org/10.1188/15.ONF.681-682

Došen, A. (2014). Psychische stoornissen, probleemgedrag en verstandelijke beperking. Een integratieve benadering bij kinderen en volwassenen [Mental disorders, problem behavior, and intellectual disability. An integrative approach in children and adults]. Van Gorcum.

Egli, M., Feurer, I., Roper, T., & Thompson, T. (2002). The role of residential homelikeness in promoting community participation by adults with mental retardation. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 23(3), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0891-4222(02)00096-3

Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308385

Heller, T., Miller, A. B., & Factor, A. (1998). Environmental characteristics of nursing homes and community-based settings, and the well-being of adults with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 42, 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.1998.00155.x

Jacobson, N.S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance. A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 12–19. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12

Karol, E., & Smith, D. (2019). Impact of design on emotional, psychological, or social well-being for people with cognitive impairment. HERD Health Environments Research Design Journal, 12, 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1937586718813194

Kratochwill, T. R., & Levin, J. R. (Eds.). (2014). Single-case intervention research: Methodological and statistical advances. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14376-000

Leuenberger, T., & Möhn, A. (2022). Ein Zimmer zum Wohnen- Eine architektursoziologische Perspektive auf die Gestaltung von Lebensräumen in der Psychiatrie. In L. Hofrichter, M. Könne, & A. Kuckert-Wöstheinrich (Eds.), Soul in Space Psychiatrie trifft Architektur (pp. 161–167). Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft.

Möhn, A. (2021). Best Practice: A personalized and humanized environment. In C. Günther & B. Klein (Eds.), Connected living: International and interdisciplinary conference (pp. 117–125). Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences. https://doi.org/10.48718/98d5-zp59

Mohr, C., Tonge, B., Einfeld, B., & Taffe, J. (2011). Manual for the Developmental behaviour Checklist (DBC-A). University of New South Wales and Monash University, Australia: Supplement to the Manual for the Developmental Behaviour Checklist – DBC-P and DBC-T.

Mohr, C., Tonge, B., & Einfeld, S. (2004). The Developmental Behaviour Checklist for Adults (DBC-A): Supplement to the Manual for the Developmental Checklist - DBC-P and BBC-T. University of New South Wales and Monash University.

Mueller-Schotte, S., Huisman, E., Huisman, C., & Kort, H. (2022). The influence of the indoor environment on people displaying challenging behaviour: A scoping review. Technology and Disability. https://doi.org/10.3233/TAD-210352

Olivier-Pijpers, V. C., Cramm, J. M., & Nieboer, A. P. (2020). Cross-sectional investigation of relationships between the organisational environment and challenging behaviours in support services for residents with intellectual disabilities. Heliyon, 6(8), e04751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04751

Parker, R. I., Vannest, K. J., Davis, J. L., & Sauber, S. B. (2011). Combining nonoverlap and trend for single-case research: Tau-U. Behavior Therapy, 42, 284–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2010.08.006

Roos, J., Koppen, G., Vollmer, T. C., Van Schijndel-Speet, M., & Dijkxhoorn, Y. (2022a). Unlimited surrounding: A scoping review on the impact of the built environment on health, behavior, and quality of life of individuals with intellectual disabilities in long-term care. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 15(3), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/19375867221085040

Roos, B., Mobach, M., & Heylighen, A. (2022b). How does architecture contribute to reducing behaviours that challenge? A scoping review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 127, 104229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2022.104229

Schalock, R. L., & Verdugo, M. A. (2002). Handbook on quality of life for human service practitioners. American Association on Mental Retardation.

Schalock, R., Verdugo, M. A., & Gomez, L. E. (2011). Evidence-based practices in the field of intellectual and developmental disabilities: An international consensus approach. Evaluation and Program Planning, 34, 273–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2010.10.004

Thompson, T., Robinson, J., Dietrich, M., Farris, M., & Sinclair, V. (1996). Interdependence of architectural features and program variables in community residences for people with mental retardation. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 101(3), 315–327.

Verdugo, M.A., Gomez, L.E., Arias, B., Santamaria, M., Navallas, E., Fernandez, S., & Hierro, I. (2014). San Martín Scale. Quality of life assessment for people with significant disabilities. Fundación Obra San Martin.

What Works Clearinghouse. (2022). What Works Clearinghouse procedures and standards handbook (Version 5.0). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/WWC/Docs/referenceresources/Final_WWC-HandbookVer5_0-0-508.pdf

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval

The study protocol was approved by the organization’s Ethical Committee and performed in accordance with ethical standards comparable with those laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed Consent

Written consent for the study was obtained from clients’ legal representatives after they were fully informed about the aims of the study both orally and in writing.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roos, J., Möhn, A., Ponsioen, A. et al. Redesigning Rooms of Clients With Intellectual Disabilities and Severe Behavioral Problems in a Long-term Care Facility: Three Case Studies. J Dev Phys Disabil (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-024-09955-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-024-09955-7