Abstract

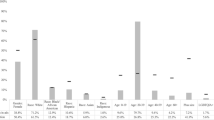

Anime is now considered an accepted form of animation and is considered to represent Japanese contemporary culture worldwide. There are many fans of anime and manga, creating a community known as otaku world. However, Japanese anime and manga have gained popularity in Western countries as well as in Japan. This paper attempts to ascertain the determinants of watching anime in Japan based on individual-level data from Japan. Despite the growth in the number of adult anime fans, children are still more likely to watch anime than adults are. Hence, this study investigates how adults are influenced by the presence of their children. After controlling for individual characteristics, it was found that people are more likely to watch anime when they have children aged less than 12 years who have not yet entered junior high school. Such an effect is larger for parents who belong to an older generation where people are less likely to prefer anime. This implies that the externality coming from children results in parents watching anime. The findings of this study show that externalities from surrounding people play a critical role in enlarging the market of modern cultural goods representing “Cool Japan.”

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Takashi Murakami, an influential Japanese artist, has adopted anime-style characters in his artworks, including paintings and plastic figures.

Asai (2011) attempted to analyze demand for popular music in Japan, which is also considered as Japanese contemporary culture.

Even if watching anime does not influence parents’ utility levels, parents naturally glance at anime when children are watching it in the living room.

Data for this secondary analysis, “Japanese General Social Surveys (JGSS), Ichiro Tanioka,” were provided by the Social Science Japan Data Archive, Information Center for Social Science Research on Japan, Institute of Social Science, University of Tokyo.

In the original dataset, annual earnings were grouped into 19 categories, and it was assumed that everyone in each category earned the midpoint value. For the top category of “23 million yen and above,” it is assumed that everybody earned 23 million yen. Approximately 1 % of observations fell in this category; therefore, the problem of top-coding should not be an issue here.

A Japanese prefecture is equivalent to a state in the USA or a province in Canada. There are 47 prefectures in Japan.

To consider such spatial correlation in line with this assumption, the Stata cluster command was used and z-statistics were calculated using robust standard errors.

Manga is different from anime in that consumers cannot read and enjoy manga with others. Hence, the externality for manga is thought to be smaller than for anime.

Professor Kentaro Takemura is a creator and critic of manga at the Kyoto Seika University. He has been reported to have an ambivalent reaction to the fact that manga is now officially recognized by the Japanese government (Takekuma 2004, 67–70).

“Manga and anime museums have sprung up across Japan since the 1990s” (Daily Yomiuri 2011).

References

Abe, Y. (2009). The effects of the 1.03 million yen ceiling in a dynamic labor supply model. Contemporary Economic Policy, 27(2), 147–163.

Abe, Y. (2011). The equal employment opportunity law and labor force behavior of women in Japan. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 25, 39–55.

Akerlof, G. A., & Kranton, R. E. (2000). Economics and identity. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 715–753.

Asai, S. (2011). Demand analysis of hit music in Japan. Journal of Cultural Economics, 35(2), 101–117.

Becker, G. (1996). Accounting for tastes. London: Harvard University Press.

Belk, R. W. (1987). Material values in the comics: A content analysis of comic books featuring themes of wealth. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(1), 26–42.

Calvo-Armengol, A., & Jackson, M. O. (2009). Like father, like son: Social network externalities and parent-child correlation in behavior. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 1(1), 124–150.

Cameron, S. (1986). The supply and demand for cinema tickets: Some UK evidence. Journal of Cultural Economics, 10, 38–62.

Cameron, S. (1988). The impact of video recorders on cinema attendance. Journal of Cultural Economics, 12, 73–80.

Cameron, S. (1990). The demand for cinema in the United Kingdom. Journal of Cultural Economics, 14, 35–47.

Cameron, S. (1999). Rational addiction and the demand for cinema. Applied Economics Letters, 6, 617–620.

Cheng, S. W. (2006). Cultural goods creation, cultural capital formation, provision of cultural services and cultural atmosphere accumulation. Journal of Cultural Economics, 30(4), 263–286.

Cuadrado, M., & Frasquet, M. (1999). Segmentation of cinema audiences: An exploratory study applied to young consumers. Journal of Cultural Economics, 23, 257–267.

Daily Yomiuri. (2008). Aso unveils statue of ‘Kochikame’ cop. Daily Yomiuri. Accessed 9 Nov 2008.

Daily Yomiuri. (2011). Manga museums preserve precious cultural tradition. Daily Yomiuri. Accessed 23 Sep 2011.

Denison, R. (2008). Star-spangled Ghibli: Star voices in the American versions of Hayato Miyazaki films. Anime, 3, 129–146.

Dewally, M., & Ederington, L. (2006). Reputation, certification, warranties, and information as remedies for seller-buyer information asymmetries: Lessons from the online comic book market. Journal of Business, 79(2), 693–729.

Dewenter, R., & Westermann, M. (2005). Cinema demand in Germany. Journal of Cultural Economics, 29, 213–231.

Fernández, V., & Baños, J. (1997). Cinema demand in Spain: A cointegration analysis. Journal of Cultural Economics, 21, 57–75.

Fernandez, R., Fogli, A., & Olivetti, C. (2004). Mother’s and sons: Preference formation and female labor force dynamics. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119, 1249–1299.

Greene, W. (2008). Econometric analysis (6th ed.). London: Prentice-Hall.

Halloway, S. D. (2010). Women and family in contemporary Japan. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hoge, D., Petrillo, G., & Smith, E. (1982). Transmission of religious and social values from parents to teenage children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 44(3), 569–580.

Jepsen, L. K. (2005). The relationship between wife’s education and husband’s earnings: Evidence from 1960–2000. Review of Economics of the Household, 3, 197–214.

Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO). (2005a). “Cool” Japan’s economy warms up. Japan Economic Monthly. http://www.jetro.go.jp/en/reports/market/pdf/2005_27_r.pdf. Accessed 3 Dec 2013.

Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO). (2005b). Japan anime industry trends. Japan Economic Monthly. http://www.jetro.go.jp/en/reports/market/pdf/2005_35_r.pdf. Accessed 3 Dec 2013.

Lu, A. S. (2008). The many faces of internationalization in Japanese anime. Anime, 3, 169–187.

MacMillan, P., & Smith, I. (2001). Explaining post-war cinema attendance in Great Britain. Journal of Cultural Economics, 25, 91–108.

MECSST (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology). (2000). Japanese government policies in education, science, sports and culture 2000. Tokyo: MECSST.

Moulton, B. R. (1990). An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro unit. Review of Economics and Statistics, 72(2), 334–338.

Nakamura, I., & Onouchi, M. (2006). The Japan’s Pop Pawer (Nippon no Pop Pawer). Tokyo: Nihon Kezai Shimbun-sha Press (in Japanese).

Napier, S. J. (2000). Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing contemporary Japanese Anime. New York: Palgrave.

Oswald, A. J., & Powdthavee, N. (2010). Daughters and left-wing voting. Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(2), 213–227.

Sakurai, T. (2009). The history of Japan’s Anime foreign policy (Anime Bunka Gaikoshi). Tokyo: Chikuma-shobo Press (in Japanese).

Sakurai, T. (2010). That’s what makes Japan’s culture so unique (Grapagosu-ka no Susume). Tokyo: Kodan-sha Press (in Japanese).

Shiraishi, S. (1997). Japan’s soft power: Doraemon goes overseas. In P. J. Katzen & T. Shiraishi (Eds.), Network power: Japan and Asia. New York: Cornell University Press.

Shiraishi, S. (2013). The Globalization of Japan’s Manga and Anime (Gurobaru-ka shita Nihon no Manga to Aneme). Tokyo: Gakujutsu Shuppan-kai Press (in Japanese).

Sugiyama, T. (2006). Cool Japan (Sekai ga Kaitagaru Nihon). Tokyo: Shoden-sha Press (in Japanese).

Takekuma, K. (2004). Why is payment for copy of comics low? (Manga Genkoryo wa Naze Yasuika). Tokyo: East Press (in Japanese).

Washington, E. L. (2008). Female socialization: How daughters affect their legislator father’s voting on women’s issues. American Economic Review, 98, 311–332.

Wyburn, J., & Roach, P. (2012). A hedonic analysis of American collectable comic-book prices. Journal of Cultural Economics, 36(4), 309–326.

Yamamura, E. (2008). Socio-economic effects on increased cinema attendance: The case of Japan. Journal of Socio-economics, 37(6), 2546–2555.

Yamamura, E. (2009). Rethinking rational addictive behavior and demand for cinema: A study using Japanese panel data. Applied Economics Letters, 16(7), 693–697.

Yamamura, E. (2010). How do female spouses’ political interests affect male spouses’ views about a women’s issue? Atlantic Economic Journal, 38(3), 359–370.

Yoon, H., & Malecki, E. J. (2010). Cartoon planet: Worlds of production and global production networks in the anime industry. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(1), 239–271.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the insightful comments of two anonymous referees, which have improved this article considerably. I am responsible for all remaining errors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yamamura, E. The effect of young children on their parents’ anime-viewing habits: evidence from Japanese microdata. J Cult Econ 38, 331–349 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-013-9213-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-013-9213-y