Abstract

We study the impact of the media negativity bias on tax compliance. Through a framed laboratory experiment, we assess how the exposure to biased news about government action affects compliance in a repeated taxation game. Subjects treated with positive news are significantly more compliant than the control group. Instead, the exposure to negative news does not prompt any significant reaction compared to the neutral condition, suggesting that participants may perceive the media negativity bias in the selection and tonality of news as the norm rather than the exception. Overall, our results suggest that biased news provision is a constant source of psychological priming and plays a vital role in taxpayers’ compliance decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Economists have traditionally modeled tax compliance as the outcome of a rational choice between risky assets in a portfolio (Becker, 1986; Allingham & Sandmo, 1992). This approach does not fully explain the compliance behavior of individuals, as moral and social dynamics also drive individual reporting decisions (Andreoni et al., 1998; Bott et al., 2019; Hallsworth et al., 2017). Previous research suggests that taxpayers’ satisfaction with government action is a critical driver of their propensity to comply. If citizens believe that the government does not spend their taxes well, they may want to reciprocate by refusing to pay their full tax liability (Spicer & Lundstedt, 1976). If, instead, the belief prevails that institutions use taxes to fund public goods and services adequately, taxpayers will be more willing to comply (Alm et al., 1993). Even when they do not receive a full public good equivalent of their payments, citizens may be intrinsically motivated to honestly declare their income as if a “psychological contract” with tax authorities was in force (Fehr & Gächter, 1998; Frey & Feld, 2002; Frey et al., 2004). According to Feld and Frey (2007), such a contract holds as far as citizens perceive the political process as fair and the policy outcomes as legitimate, resulting in a stronger willingness to contribute to the welfare of the community.

These perspectives imply a vital role for information about government action and the fairness of the political process. The media’s coverage of economic and policy issues, however, is far from being balanced. The communication literature agrees that mass media tend to over-report negative news as they generate stronger psychophysiological reactions in the audience (Soroka et al., 2019), and they better fit the public’s preference for negative contents (Agirdas, 2015). The negativity bias has proved particularly pronounced in the presentation of political (Cappella & Jamieson, 1997; Kepplinger et al., 2012; Le Moglie & Turati, 2019) and economic news (Garz, 2014; Soroka et al., 2018). Given the role of information in shaping the public’s opinion about public institutions, research on tax compliance should address the impact of the media negativity bias. However, empirically studying how the media affect citizens’ willingness to pay their taxes is challenging in many respects. Existing surveys do not provide information about the possible bias of the news consumed by the public, and the use of survey data entails endogenous sample selection and treatment assignment that prevent ascertaining causality.

To address these issues, we design a framed laboratory experiment (Alm, 2012) that allows us to analyze how exposure to biased news affects compliance in a repeated taxation game. Experimental manipulations consist of news tickers reporting top stories about public finance and policy issues that run on subjects’ screens during the game. Using a between-subjects design, we contrast tax compliance outcomes under three conditions: negative, positive, and neutral news provision. The negative treatment reflects the media negativity bias that the communication literature credits with being the status quo in the supply of news about public finance and policy issues (e.g., Soroka et al., 2018; Soroka et al., 2019). Compared to the neutral treatment, the negative news condition seems not to affect tax compliance, suggesting that participants likely perceive the media negativity bias as the norm rather than the exception (Cappella & Jamieson, 1997; Elejalde et al., 2018; Garz, 2014; Kepplinger et al., 2012; Soroka et al., 2019). As the selection and tonality of news deviate from the status quo resulting in positive content, participants become significantly more compliant than the control group. The effect is economically sizable: subjects treated with good news reported a 23 percentage points higher compliance rate than those exposed to negative or neutral news. Overall, our results reveal that how the media present public finance and policy issues is a crucial determinant of tax compliance, suggesting that biased news is a constant source of psychological priming that may prevent the public sector from fully exploiting its tax revenue potential.

Our paper bridges two strands of literature. The first comprises the economics of tax compliance, which has been approached from many perspectives (see Andreoni et al., 1998; Alm, 2012, 2019, for a review). We focus on the moral and social perspective on taxpayers’ behavior, which has linked compliance to the efficiency and fairness of public institutions (Alm et al., 1993; Koessler et al., 2019; De Neve et al., 2021; Feld & Frey, 2007; Hallsworth et al., 2017; Murphy & Tyler, 2008; Smith, 1992; Tyler, 1990; van Dijke & Verboon, 2010). These studies implicitly assume a critical role for information. We clarify this role and add to the literature by showing the compliance implications of biased information about government action and public finance issues. More in general, our findings improve the understanding of the psychological and social drivers of compliance, also including peer effects (Alm et al., 2017), cultural traits (Alm et al., 2017), trust in institutions (McKee et al., 2018; van Dijke & Verboon, 2010), social norms (Abraham et al., 2017; Becchetti et al., 2017; Lefebvre et al., 2015), corruption (Alm et al., 2016; Rotondi & Stanca, 2015), fairness concerns (Alesina & Angeletos, 2005; Gualtieri et al., 2019; Sabatini et al., 2020), and intrinsic motivations (Calvet Christian & Alm, 2014; Cerqueti et al., 2019; Dwenger et al., 2016; Luttmer & Singhal, 2011, 2014).

The second strand of literature studies how media bias affects economically relevant behavior such as voting (Chiang & Knight, 2011; DellaVigna & Kaplan, 2007), civic-mindedness (Durante et al., 2019), crime perceptions (Mastrorocco & Minale, 2018), and consumption behavior (Nguyen & Claus, 2013), just to name a few. There is growing evidence that the media may also have an impact on tax compliance. Garz and Pagels (2018) show that the media coverage of celebrities’ tax issues causes an increase in the number of self-denunciations. Kasper et al. (2015) use a survey experiment to show that exposure to news that presents Austrian tax authorities as trustworthy leads to stronger trust in authorities and higher intended compliance. Cyan et al. (2017) find that TV and newspaper ads can improve individual attitudes toward tax compliance in Pakistan. We contribute to this field by focusing on a specific type of bias, the negativity bias, and revealing a so far unexplored outcome of this phenomenon. Our experimental approach also adds to the communication literature that studies the media negativity bias (Cappella & Jamieson, 1997; Garz, 2014; Soroka et al., 2018; Soroka et al., 2019; Trussler & Soroka, 2014), by suggesting that the systematic tendency of the media to focus on negative news may entail hidden social costs connected to the government’s inability to meet its revenue objectives.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 briefly discusses the related literature and presents our hypotheses. Section 3 describes our experimental design and procedures. Section 4 presents our results. We discuss our findings and their possible policy implications in Sect. 5 and conclude in Sect. 6.

2 Media negativity bias and tax compliance

A vast literature documents that media report bad news at a pace that does not mirror reality (Soroka, 2012). The coverage of negative events does not accurately reflect their actual distribution in real life, resulting in a distortion bias (Altheide, 1997; Entman, 2007). For example, crime reporting follows a different trend than the real indicators of crime (Lawrence & Mueller, 2003). The same holds for the involvement of minorities in riots (Entman, 1994), political scandals (Cappella & Jamieson, 1997; Semetko & Schoenbach, 2003), episodes of corruption (Soroka & McAdams, 2015), transport accidents (van Der Meer et al., 2019), and long-term socioeconomic trends (Gibson & Zillmann, 1994; Harrington, 1989; Kollmeyer, 2004). Empirical studies document that the negativity bias is stronger in the news making of issues related to politics and economic policy (Elejalde et al., 2018; Hester & Gibson, 2003; Kepplinger et al., 2012; Lengauer et al., 2012). The cross-disciplinary literature identified various sources of the media negativity bias. Communication studies emphasize that newsworthiness is linked to negativity across all subjects (Lawrence & Mueller, 2003; Soroka, 2012). Negative events are unambiguous, unexpected, and occur over a shorter time than positive news, which are more often gradual, potentially boring, and less appealing (Pinker, 2018). Many authors suggest that the disproportionate reporting of negative stories is a result of the media’s attempt to attract public attention and gain followers (Hamilton, 2011; Pinker, 2018). Trussler and Soroka (2014) show that newsstand magazine sales increase by roughly 30% when the cover is negative rather than positive. A growing body of evidence in psychology illustrates the human tendency to prioritize negative over positive news content. Soroka and McAdams (2015) show that negative increases arousal and attentiveness compared to positive content in controlled environments. Soroka et al. (2019) document that experimental subjects are more physiologically activated by negative than positive news stories, suggesting that humans may be neurologically or physiologically predisposed toward focusing on negative information. This cognitive bias may have evolutionary origins rooted in the fact that the usefulness of negative information outweighs the benefits of positive information in survival-related decisions (McDermott et al., 2008; Soroka et al., 2019). Overall, this literature suggests that the media negativity bias is driven by the public’s stronger demand for negative content. As a result, negativity has grown to become among the most dominant selection criteria of media logic (e.g., (Keung & Lee, 2015; Lawrence & Mueller, 2003), causing a systematic difference in the degree of negativity between the real world and media content (Soroka, 2012).

The negativity bias is particularly pronounced in Central-Eastern Europe, where the media are facing the challenge of regaining public trust, devastated by their role of serving the state under real socialism (Rose, 1994; Sztompka, 2000; Trifonova Price, 2019). In the Czech Republic, where we carried out our experiment, trusting the institutions, including media and journalists, was long seen as naïve (Sztompka, 2000; Volek & Urbániková, 2017). After 1989, public trust in the media has been partially restored but experienced a new decline after the economic crisis in 2008 (Newman et al., 2018). In recent years, the Czech media market has experienced significant ownership concentration with control shifting toward domestic tycoons, resulting in increasing polarization and a tendency to put the public sector in a bad light. According to the Digital News Report 2020 (Newman et al., 2020), these developments caused a further decline in trust in the media, which fell among the lowest in Europe. Moreover, positive presentations of public policy outcomes and, in general, of the State’s role in the economy still tend to prompt skepticism among the public (Volek & Urbániková, 2017). As a result, Czech media had to emphasize negative content further to gain attention and trust, especially regarding the state’s intervention in the economy.

A policy-relevant outcome of the negativity bias lies in the public’s perception of the negative events’ distribution in real life. The public is led to think that over-represented events outnumber “normal” events in real life (Soroka, 2012, 2014; van Der Meer et al., 2019). For example, Mastrorocco and Minale (2018) show that exposure to TV channels over-representing minorities in the coverage of crime episodes increases concerns about crime and raises votes for parties campaigning against minorities.

Following the literature summarized above, the Czech public could see bad news about public policy outcomes as the norm rather than the exception. As a result, the behavioral response of the experimental subjects exposed to the negative condition may not necessarily differ from that of participants involved in the neutral condition. We then expect the following result from the laboratory experiment:

Hypothesis 1

Tax compliance may not significantly differ between subjects exposed to the negative and the control condition.

With the “positive treatment,” we aim to study whether a deviation from the media’s status quo, resulting in the exposure to good news about the public sector, may increase compliance across experimental subjects. There is field evidence that providing taxpayers with factual information about the use of tax revenues may increase income self-reporting and tax compliance. Hallsworth et al. (2017) show that mentioning in tax reminders specific services that recipients were likely to have used themselves markedly raised the likelihood of individuals paying their declared tax liabilities in the UK. Bott et al. (2019) show that Norwegian taxpayers targeted with messages stressing the societal benefits of taxation self-report significantly higher amounts of foreign income. De Neve et al. (2021), instead, show that treating taxpayers with factual data about how tax revenues are spent does not increase compliance in Belgium. Invoking tax morale, instead, seems counterproductive in a payment reminder experiment.

Though less externally valid than a field experiment, our laboratory setting allows us to treat subjects with more specific information about public policy outcomes. Instead of factual information, as in De Neve et al. (2021) and Bott et al. (2019) or moral messages, as in Hallsworth et al. (2017), we administer news tickers reporting top stories about public finance and policy issues. Stories basically focus on successful projects carried out by the public sector (see Appendix 1 for the complete list of stories in the three alternative treatments). The motivation of this approach lies both in our interest in the impact of the media bias and in evidence that anecdotal messages are much more salient than factual information and prompt more significant reactions in taxpayers (Alesina et al., 2018). We differentiate from previous studies on tax morale and tax compliance by focusing on the role of the media and exploiting messages that contrast with the negative climate characterizing the media’s representation of the public sector in the Czech Republic. Instead of proposing neutral information about the destination of public expenditure (as in Bott et al., 2019; De Neve et al., 2021), we provide subjects with specific examples of successful public projects funded with tax revenues. Such examples are provided in the form of news stories. By proposing the first experiment of this kind in a post-communist country, our work allows us to study tax compliance in a setting characterized by historically low trust in the media and marked negativity bias in the representation of the public sector. Two mechanisms may stimulate the willingness to comply with experimental subjects treated with positive news. First, compliance may be a matter of reciprocity (Fehr & Gächter, 1998; Feld & Frey, 2007). Examples of successful public expenditure may raise citizens’ trust in institutions and confidence that the state will spend their taxes well, making them more willing to pay their entire tax liability. Second, evidence of how tax revenues increase public welfare may make taxpayers more concerned with fairly contributing to the well-being of the community. The very fact of deviating from the status quo resulting from the “positive treatment” may also strengthen the mechanisms, given the specific features of the Czech Republic, a post-communist country with historically low trust in institutions. The positive perception of how public institutions work may trigger reciprocity attitudes toward fellow citizens in general and, therefore, the other participants in the experiment. This issue is widely debated in the political science literature on procedural justice, which provides evidence that fair and efficient policies strengthen citizens’ trust in institutions that spills over on generalized trust, i.e., trust toward fellow, unknown, citizens. Kumlin and Rothstein (2005), Newton et al. (2018) and Rothstein and Stolle (2008) argue that well-functioning government institutions stimulate cooperative behavior and the willingness to comply with rules because people’s views of the society around them and of their fellow human beings are partly shaped by their perception of the efficiency and fairness of state institutions. Based on World Values Survey data, Letki (2006) finds that citizens are law-abiding to the extent to which democratic and bureaucratic institutions are perceived to perform well, concluding that the trustworthiness of efficient institutions influences individual attitudes and behavior. Kydd (2000) and Delhey and Newton (2005) suggest that the behavior of public institutions signals to citizens about the moral standard of the society in which they live, thereby informing their behavior in everyday strategic interactions. According to Rothstein and Stolle (2008), the mechanism relies on the belief that institutions do what they are supposed to do in a fair, reasonably efficient, and unbiased manner, which leads to thinking there is a limited chance of people getting away with treacherous actions. These beliefs may give people a good reason to refrain from cheating behaviors such as tax evasion.

In light of the arguments summarized above, we pose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

The subjects exposed to positive news are more likely to report their income correctly.

In each treatment, we made individuals earn their endowment under two different configurations as a robustness check to rule out the possibility of confusing the effect of media bias with that of the origin of income. In the first configuration, participants earned their income through a real effort task. In the second, experimenters exogenously endowed participants with an amount of money. The literature offers no clear evidence on the differential role of earned versus endowed money in tax compliance. Previous studies found that windfall gains weaken negative reciprocity (Danková & Servátka, 2015) and increase the propensity for charitable giving (Carlsson et al., 2013) and risk taking (Rudisser et al., 2017). By contrast, Luccasen and Grossman (2017) found that giving to charity or philanthropic institutions increases when the endowment is earned in a real-donation experiment. Several authors (Boylan & Sprinkle, 2001; Boylan, 2010a; Clark, 2002) found no difference in the tax compliance of subjects who earned money or were exogenously endowed. Still, when the tax rate increased, participants with earned money increased their compliance, whereas those with endowed money evaded more (Boylan & Sprinkle, 2001; Boylan, 2010a). Some experiments suggest that the impact of the source of income also depends on time, with compliance declining with the interaction between effort and the number of rounds (e.g., Durham et al., 2014). Boylan (2010a) found that participants with earned money were more compliant than those benefiting from windfall money before an audit but decreased their compliance after the audit, while the reverse was true for those with endowed money. Other authors found that participants who earn their income through a moderate effort are more likely to comply than those who performed high effort tasks or were exogenously endowed (Bühren & Kundt, 2013; Kirchler et al., 2009). Overall, the available evidence is not conclusive, and we do not have a definite hypothesis on how the origin of income may affect compliance. Instead, the two configurations mainly serve as a robustness check to disentangle the role of media bias from that of a possible confounding factor.

3 Experimental design

To circumvent the selection and endogeneity problems arising in the analysis of naturally occurring data, we designed a framed laboratory experiment (Alm, 2012; Harrison & List, 2004) where we targeted three distinct randomly determined groups of participants with two main treatments, respectively, based on the exposure to negative \((T_{{\rm NEG}})\) and positive \((T_{{\rm POS}})\) media bias. A third control group received a neutral \((T_{{\rm NEU}})\) treatment characterized by the absence of any salient bias. Experimental manipulations consisted of news tickers reporting top stories about public finance and policy issues that ran on subjects’ screens during a repeated taxation game (Alm et al., 2015; Alm & Malézieux, 2020).

As explained in Sect. 2, we made individuals receive their endowments under two different configurations. In the first endowment configuration, participants earned income by working on a structured series of conventional real-effort tasks \((C_{{\rm RE}})\) and were rewarded based on their performance.Footnote 1 We calibrated the piece rates to generate a framed endowment \(I\in (8500;50{,}500)\) EMU compatible with the nominal distribution of income in the Czech Republic.Footnote 2 In the second configuration, subjects exogenously received an endowment in the form of windfall money \((C_{{\rm WF}})\) drawn from the actual endowment distribution generated in the real-effort sessions. Finally, participants played a conventional taxation game (Malezieux, 2018) in groups of four subjects in a partner-matching protocol.

The game was repeated for five rounds. Subjects received information about their earnings at the end of each round. The final payment consisted of the sum of the earnings obtained in the five rounds (Charness et al., 2016). Each round of the taxation game was partitioned into three sequential stages. (i) The first stage concerned the individual income (I) generation. (ii) In the second stage, we asked participants to self-report their income \((0\le R_{i}\le I_{i})\) to establish their tax liability. We then taxed the declared income at a flat rate t = 0.15 as for the personal income tax rate in the Czech Republic. All the experimental parameters of our framed laboratory experiment are modeled on the Czech case (Czech General Financial Directorate, 2016).

Tax audits took place between the second and third stages. The probability of receiving an audit was p = 0.05. Tax cheaters were exposed to a fine equal to the unpaid tax multiplied by a penalty factor \(\alpha =10\). The intense penalty factor is intended to model the severe consequences that tax evaders face after conviction.Footnote 3 The parameter \(\alpha\) is always kept constant across all treatments and all rounds.Footnote 4

(iii) In the third stage, participants learned about taxation outcomes and anonymizedFootnote 5 audit results. Subjects could also see the amount of taxes overall paid by the group. To model the utility generated by the consumption of the public good funded through the taxation scheme, each participant received a share of the total tax revenue b = 0.125.Footnote 6 As a result, the payoff function was:

for subjects who did not receive the audit, and:

for participants targeted with a tax inspection.

Throughout the three stages of the game, a series of 15 news headlines rotated in 6 s intervals at the bottom of participants’ screens. The main treatment manipulation consisted of randomly assigned headlines with a systematically biased tone (positive, negative, and neutral) to each distinct experimental group of subjects. Under the positive treatment, participants regularly saw positive news about the efficient use of the government budget (for example, State Housing Department Fund will provide advantageous loans, or Governmental program supporting science centers and generous grants successful: best minds returning home). In the negative treatment that aimed at reproducing the real-world media negativity bias, subjects saw headlines reporting negative news on the ineffective or inappropriate use of public funds (for example, National debt increased to CZK 1.68 billion, or Low civil servant efficiency decreased the Czech Republic’s competitiveness; down to 46th in global ranking). In the neutral treatment baseline condition, the news reported about public events of general interest with very neutral contents (for example, The World Dog Show in Crufts is hosting 28 thousand dogs). Appendix 1 reports the complete list of headlines in detail and provides a link to video capture of the implementation.

A focus group of ten Ph.D. students in political sciences (five males, five females) at Masaryk University selected the news headlines and qualitatively classified their tone into three categories. Building on computational linguistics methods (Taboada et al., 2011), we then quantitatively assessed the sentiment gradient of the different corpora of headlines through the algorithm developed by Repustate.com (Cieliebak et al., 2013). The algorithm delivers a rating between − 1.000 and − 0.051 if the tone is negative, − 0.050 and 0.050 for neutral news, and between 0.051 and 1.000 for positively toned news. In our experiment, the rating was − 0.750 for the negative treatment, 0.010 for the neutral treatment, and 0.870 for the positive treatment.Footnote 7

A total of 220 subjects, recruited via Hroot (Bock et al., 2014), participated in the experiment in fall 2016.Footnote 8

After showing up at pre-scheduled session times, subjects were seated at individual cubicles equipped with computers. Seats were randomly assigned. Sessions took place at the Masaryk University Experimental Economics Laboratory (MUEEL) in Brno, Czech Republic. The language of the experiment was Czech. (Full translated instructions and screenshots are reported in Appendix 4.) We programmed and implemented the experiment using zTree (Fischbacher, 2007). Sessions lasted about 60 min, including a post-experimental questionnaire, and the average payoff was approximately 10 EUR (250 CZK, including the show-up fee).Footnote 9 Table 1 reports descriptive information about the composition of the experimental sessions by main experimental treatments (neutral, negative, and positive) and endowment configurations (real-effort, windfall).

4 Results

In this section, we first report about the balancedness of several sample dimensions across experimental groups (Sect. 4.1). We then analyze how the exposure to biased news affects participants’ taxation behavior considering three main outcome measures. Preliminarily, we address the overall level of tax revenue generated under the three different treatments (Sect. 4.2) and the share of full compliers (Sect. 4.3). Then, we develop our analysis examining in depth the effect of our three main treatments on the normalized compliance rate—the ratio between the amount reported and the actual income—(Sect. 4.4). This index represents our most encompassing outcome measure. Offering results from additional Double-Hurdle regression models (Cragg, 1971; Engel & Moffatt, 2014), Sect. 4.4.1 blends together—adopting an integrated framework—the sets of analysis discussed in the previous subsections.

4.1 Randomization check

Table 2 reports the mean values and randomization checks (p values according to (Chiapello, 2018) of some conventional individual characteristics elicited with a standard post-experimental questionnaire (gender, age, field of studies, religious and political attitudes, and the individual degree of risk aversion).Footnote 10 Most of these individual characters are uniformly balanced across experimental treatments (neutral, negative, and positive) and endowment configurations (real-effort, windfall). In the following parametric analysis (Tables 3 and 4), we will also consider this specific array of covariates to control for the few non-perfectly balanced characteristics.

4.2 Tax revenue

We start by investigating tax behavior focusing on the overall level of tax revenues generated under the main treatment conditions. By construction, this measure (\(tR_{i}\)) directly depends on the level of self-reported income. While the actual average income was balanced by design across treatments (Table 2), our analysis reveals that the average tax revenues generated under the positive treatment systematically differed from the other two treatment conditions. The average tax revenue generated in the neutral and the negative treatment equals 3501.01 (std. dev. 2303.07) and 3498.15 (std. dev. 2364.57) EMU, respectively. The overall effect size index (Cohen, 1988; Ellis, 2010) assessing the difference between these average amounts turns out to be very small (Cohen’s d = 0.01/ very small effect size; p value = 0.94, MWU-test). Under the positive treatment, average tax revenues jump to 4261.95 (std. dev. 2344.99) EMU. The differential effect registered under the positive treatment is meaningful in its effect size and highly statistically significant compared to the level of tax revenues observed in the neutral and the negative treatment (Cohen’s d = 0.33/medium effect size; \(p\,\mathrm{value}<0.01\), MWU-test).Footnote 11

This descriptive difference is confirmed by the plots of the tax revenue distributions reported in Fig. 1. The cumulative density function (CDF) associated with the positive treatment “first-order” dominates the CDFs observed under neutral and negative. The plot of kernel density functions (KDF) reported in Fig. 2 corroborates this finding revealing an overall well-behaved “inverted U-shape” pattern that only for the positive treatment results to be significantly negatively skewed toward higher levels of tax revenue (\(p\,\mathrm{value}<0.01\), Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for equality of distributions) compared to the other two distributions.

The higher level of tax revenues generated under the positive treatment is confirmed by the parametric analysis reported in Table 3. Since the average aggregate measures stem from repeated observations at the group and individual level, in order to take into account such interdependencies, this parametric analysis relies on estimates from panel two-way mixed models with random effects accounting for both potential individual dependencies over rounds and intragroup correlations (see Corazzini et al., 2015, 2020).

In the baseline model (Column 1 of Table 3), we regress tax revenues against the two main treatment dummies for the negative \((T_{{\rm NEG}})\) and positive \((T_{{\rm POS}})\) treatment—with the constant term capturing the neutral condition—and we control for the configuration of the endowment generation process (dummy \(C_{{\rm RE}}\), real-effort). On average, the subjects exposed to the positive treatment generate a level of tax revenues that is 784 EMU higher (\(p\,{{\rm value}}<0.05\)) compared to the levels observed under the neutral and the negative condition. The coefficient for the negative treatment is small in magnitude and not statistically significant. In the saturated model (Columns 2), we also control for individual income, the fact of having received an audit in previous rounds as well as the fact of having being sanctioned (Mittone et al., 2017), period dummies, idiosyncratic risk aversion, and an array of standard demographics (gender, age, the field of studies, as reported in Table 2). In all models, the coefficient capturing the positive treatment turns out to be positive, sizable in magnitude, and systematically statistically significant. On average, subjects exposed to positive news generated higher tax revenues of approximately 700 EMU higher (\(p\,{{\rm value}}<0.05\)) than those exposed to negative or neutral news. As expected, this outcome is positively associated with the level of income. The gender dummy, included in demographic controls, suggests a marginally lower outcome measure in the male population.Footnote 12 The coefficient associated with the real-effort configuration dummy \((C_{{\rm RE}})\) is weakly statistically significant in the reduced-form specification (Column 1) and turns statistically insignificant in the fully saturated model (Column 2). We do not observe any robust statistical difference in tax revenues generated by subjects who earned their income performing the real-effort task and those who exogenously received their endowment in the form of windfall moneyFootnote 13 (captured in the constant term of the regression). Table 5 in Appendix 2 replicates the same analysis restricting the sample excluding full tax evaders (\(R_{i}=0\)). The main treatment effect remains qualitatively unaffected by the adoption of such restriction.

4.3 Share of full compliers

We now analyze the effect of biased news on the share of full tax compliers. In Fig. 3, we plot the shares of full tax compliers under the three treatments. Under the neutral and the negative treatment the proportion of full compliers ranges in the tight interval between 35 and 40% (Cohen’s d = 0.15 suggesting a small effect size; p value = 0.06, \(X^{2}\)). Under the positive treatment, approximately 60% of the subjects duly reported their actual income (Cohen’s d = 0.51/ medium effect size; \(p\,{{\rm value}}<0.01\), \(X^{2}\)). This difference is evocative but not fully statistically accurate, as these shares stem from repeated observations at the group and individual levels.

Regressions in Table 3 (Columns 3 and 4) corroborate this descriptive evidence following the panel two-way mixed model framework introduced in Sect. 4.2. Given the large number of data points, we rely on a more intuitively interpretable linear probability approach for this outcome. In the baseline model, we regress the full tax compliance outcome—= 1 if tax compliance \((R_{i}=I_{i})\), = 0 if tax evasion \((R_{i}<I_{i})\)—against the two main treatment variables: negative \((T_{{\rm NEG}})\) and positive \((T_{{\rm POS}})\), with the constant term capturing the neutral treatment. In all models, the coefficient of the positive treatment dummy turns out to be positive, sizable in its magnitude, and highly statistically significant. On average, the share of full compliers is 23 percentage points (\(p\,{{\rm value}}<0.01\)) higher under the positive treatment than under the negative or neutral condition. In all specifications, we control for the configuration of the income generation process. When fairness considerations are salient, endowing participants with windfall money may inflate their other-regarding behavior, thereby creating a so-called “house money effect” (Danková & Servátka, 2015). In principle, this could lead to higher compliance, thereby biasing our estimates. In our analysis, the coefficient associated with the real-effort dummy \((C_{{\rm RE}})\) is never statistically significant and always has a small size. We do not detect any systematic difference in the fraction of full tax compliance between subjects who earned their income performing the real-effort task and those who exogenously received their endowment in the form of windfall money. This lack of difference reassures us that we are not confusing the effect of media bias with that of the origin of income. This finding is consistent with previous evidence of a limited or null difference in the behavior of subjects endowed with house money or earning income through real-effort tasks (Boylan & Sprinkle, 2001; Bühren & Pleßner, 2014; Boylan, 2010a; Clark, 2002). Still, as the tax rate did not change across rounds in our experiment, we cannot fully compare our results to those in Boylan and Sprinkle (2001) and Boylan (2010a), who found that compliance increases with tax rates in participants with earned money and decreases in those with endowed income. Under the real-effort task, compliance tends to slightly increase in the second and third rounds before declining in the following rounds. Still, the coefficients of the interaction term between the real-effort dummy and round dummies are never statistically significant and always small in size. This result is inconsistent with previous evidence that compliance declines with the interaction between effort and the number of rounds (Durham et al., 2014). However, our experiment is not entirely comparable to Durham et al. (2014), who studied the effect of the origin of income jointly with that of the decision context. Differently from Boylan (2010b), we find that experiencing surveillance does not significantly change compliance, as participants’ behavior is similar before and after an audit. Overall, design and treatment differences may undermine the comparability of our findings with previous evidence, as the impact of income sources was never addressed jointly with that of media bias. In the saturated model, we also control for individual income, the fact of having received an audit and sanction in previous rounds, period dummies, idiosyncratic risk aversion, and an array of standard demographics. The gradient of full compliance is increasing in the income level and, as expected, positively affected by higher individual risk aversion. Round-specific dummies highlight a significantly higher share of full tax compliers observed in the last round of the interaction. The substantial similarity of the effect sizes between the neutral and the negative conditions supports the interpretation that participants may perceive the media negativity bias as the norm rather than the exception, consistently with the prevailing view in the media negativity bias literature (Cappella and Jamieson, 1997; Garz, 2014; Soroka et al., 2018; Soroka et al., 2019; Trussler & Soroka, 2014).

4.4 Tax compliance rate

The tax compliance rate captures a normalized intensive margin for taxation behavior. Following the recent literature (Guerra & Harrington, 2018; Jacquemet et al., 2020), we define the tax compliance rate as the ratio between the amount declared and the available income (\(\frac{_{R_{i}}}{I_{i}}\)). Compliance rate equal to one means that the subject is a full tax complier. When the ratio is equal to zero, he is a full tax evader. The index allows for all the continuous values within the two extremes. The average compliance rate is 0.62 for the neutral treatment and 0.64 for the negative one (Cohen’s d = 0.03/small effect size; p value = 0.35, MWU-test). These averages are statistically comparable and in line with the experimental literature on tax compliance and public goods (Alm, 2012; Andrighetto et al., 2016; Alm et al., 2017; Casal et al., 2016; Guerra & Harrington, 2018; Bosco & Mittone, 1997; Zhang et al., 2016). The compliance rate jumps to 0.77 under the positive treatment. The differential effect induced by the positive treatment is meaningful in its size and highly statistically significant compared to the average level of tax revenues observed in the neutral and the negative treatment (Cohen’s d = 0.38/medium effect size; \(p\,{{\rm value}}<0.01\), MWU-test).

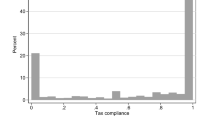

The descriptive difference is confirmed by the plots of the compliance rate distributions reported in Fig. 4. The cumulative density function (CDF) associated with the positive treatment “first-order” dominates the CDFs observed under the neutral and the negative conditions (\(p\,{{\rm value}}<0.01\), Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for equality of distributions). Figure 5 shows the plot of kernel density functions (KDF), which complements the analysis showing very similar distributions for the neutral and the negative treatments accompanied by a significantly different distribution—especially in terms of excessive negative skewness combined with positive kurtosis—generated under the positive treatment (\(p\,{{\rm value}}<0.01\), Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for equality of distributions).

The parametric analysis confirms the higher tax compliance rate observed under the positive treatment—based on panel two-way mixed estimations with random effects accounting for both potential individual dependencies over rounds and intragroup correlation—introduced in Sect. 4.2. In the baseline model (Table 3, Column 5), we regress the individual compliance rate against the two main treatment variables: negative \((T_{{\rm NEG}})\) and positive \((T_{{\rm POS}})\)—with the constant term capturing the neutral treatment. In all models, the coefficient of the positive treatment dummy turns out to be positive, sizable in magnitude, and highly statistically significant. Subjects exposed to positive news had a compliance rate 13 percentage points (\(p\,{{\rm value}}<0.01\)) higher than those exposed to negative and neutral news. In all specifications, we control for the configuration of the income generation process. Also for this outcome, the coefficient associated with the real-effort dummy \((C_{{\rm RE}})\) is never statistically significant and always has a small size. In more saturated models (columns 5–6), we also control for individual income, the fact of having received an audit and sanction in previous rounds, period dummies, idiosyncratic risk aversion, and an array of standard demographics. The compliance rate is decreasing in the level of income and, as expected, positively affected by higher levels of individual risk aversion. Round-specific dummies highlight a significantly higher compliance rate in the last round of the interaction. Table 5 in Appendix 2 replicates the analysis excluding full tax evaders from the sample (\(R_{i}=0\)). The main treatment effect holds qualitatively unaffected after the adoption of such restriction.

As for the dynamics of taxation decisions over the five rounds, Fig. 6 clearly indicates how the average compliance rate was relatively stable across rounds. The compliance rate under the positive treatment clearly dominates the one in the other two conditions in each round. While the fluctuations over rounds observed under the neutral and the negative conditions are relatively smooth, the positive last-round effect detected in the parametric analysis appears to be driven by subjects exposed to positive news.

As far as it concerns the heterogeneity “across-groups,” we analyze the plots of the kernel density functions depicting the average compliance rate at the group level, by treatments. Figures 7, 8, and 9 in Between-groups heterogeneity section of appendix show that density functions are strictly unimodal and light tailed for all the treatments, and the masses of the frequencies always concentrate around the respective mean values. The average compliance rates in the different treatments are not influenced by groups of outliers or by polarized dynamics.

The similar compliance rate observed under the neutral and the negative conditions, as well as the higher performance registered under the positive treatment, appears to be rooted in the gradient of “within-group” heterogeneity. In Within-group heterogeneity section of appendix, Figures 10, 11, and 12 display the average individual compliance rate over the five rounds, by group and treatment sorted by magnitude. Under the positive treatment only 9% of the subjects exhibits an average compliance rate smaller than 0.2—which is highly correlated with repeated full tax evasion decisions. Under the neutral and the negative conditions, the share of participants with a compliance rate smaller than 0.2 significantly increases to 15 and 20%, respectively. In all the three treatments, free riders are randomly spread across groups and not concentrated in specific clusters. At the same time, we observe a complementary pattern concerning the share of high contributors. While under the positive treatment 60% of subjects exhibit a compliance rate higher than 0.8, which is highly correlated with repeated full tax compliance decisions, this share significantly decreases to 40% under the neutral and the negative conditions. Mirroring the case for free riders, high/full compliers are homogeneously distributed in the different groups.

4.4.1 Double-Hurdle estimation

Following recent inputs by Alm et al. (2017) and Guerra and Harrington (2018) in the analysis of laboratory-generated data about the cultural determinants of tax evasion, we replicate the previous panel two-way mixed analyses adopting a Double-Hurdle (DH) approach. This class of models, introduced by Cragg (1971) and computationally developed by Engel and Moffatt (2014) for experimental applications, allows a combined estimation of the two distinct processes underlying the decision to comply and, for tax cheaters, the amount of the evasion [see Alm et al. (2017, Section 3.2) and Guerra and Harrington (2018, Section 3.2)]. In this setup, the key outcome measure is always the tax compliance rate, defined as the ratio between the amount declared and the available income (\(\frac{_{R_{i}}}{I_{i}}\)). A compliance rate = 1 means that the subject is full tax complier, with 0 meaning full tax evasion. The first hurdle is interpretable as a probability model. It focuses on the binary decision to engage in a certain degree of tax compliance (\(R_{i}>0\)) and is particularly suited to capture the effect of media bias occurring at the extensive margin. The second hurdle, interpretable as a censored Tobit model, determines the compliance gradient for subjects who chose to engage in tax compliance. Therefore, it captures the effect occurring at the intensive margin (\(\frac{_{R_{i}}}{I_{i}} \vert R_{i}>0\)).

Focusing the attention on our main coefficients of interest representing the exogenous experimental variations, the battery of Double-Hurdles models displayed in Table 4 well maps and integrates the different results described in Sects. 4.1, 4.2, and 4.3. Subjects exposed to the positive treatment are significantly more likely to engage in—at least partial—tax compliance (H1 columns). This effect is always statistically significant and sizable in its magnitude. The coefficient is relatively stable across the two alternative specifications characterized by different arrays of control variables. Coefficients associated with the negative treatment are never statistically significant at any conventional level. When we consider the second hurdle (H2 columns), we do not detect any significant differential treatment effect on the intensive margin of the compliance rate. The results of this combined analysis indicate that the positive average effect observed under the positive treatment (both in terms of absolute tax revenues and normalized compliance rate) is relatively more influenced by the higher degree of engagement in tax compliance (comparative reduction in the frequency of substantial tax evaders) in the group of subjects exposed to positive news.

5 Discussion

Our study provides the first experimental evidence that biased information about government action and public finance affects tax compliance, suggesting that news headlines are a constant source of psychological priming. In the experiment, priming participants with positive news induced a significant change in their compliance rate. The exposure to negative news, instead, failed to elicit a behavioral response. This result must be interpreted in light of the lack of statistical power detected under the neutral and the negative conditions. Though a common issue in the empirical analysis of experimental data, limited power increases the risk of mistaking a false negative for a true negative, concluding there is no effect when the treatment actually has an impact (Type 2 error). A narrower focus on the magnitude of the effects helps us to put this null result into perspective. The Cohen’s d analysis reveals that the outcomes of the neutral and the negative treatment would be negligibly different in size even in the case of full power. The substantial similarity of the two effects suggests that negative news may match what participants routinely expect to see on headlines regarding the public sector. Having in mind the caution required by the lack of statistical power, this interpretation would be in line with evidence that a negativity bias systematically pervades political (Elejalde et al., 2018; Kepplinger et al., 2012; Lengauer et al., 2012) and economic (Garz, 2014; Soroka et al., 2018) news making. This phenomenon is demand-driven, as it is likely a product of a human tendency to be more attentive to negative news content (Soroka et al., 2019), and generates a sort of ‘spiral of cynicism’ (Cappella & Jamieson, 1997), in that the public’s demand for sensational news strengthens the incentive for providing negative contents in journalists and newsmakers (Soroka et al., 2019). The historical background of the Czech Republic (Newman et al., 2020; Volek & Urbániková, 2017) and the recent spreading of anti-establishment narratives (Couttenier et al., 2019; Wettstein et al., 2018) have further exacerbated the negativity bias in reporting about the efficiency and fairness of public institutions.

Overall, the differential effect of the exposure to positive news and the substantial similarity of the size effects under the neutral and the negative conditions suggest focusing the interpretation on the positive treatment. In this case, our setup allows us to detect a statistically significant effect that is sizably different at the conventional level from those detected under the other conditions.

Contrary to intuition, which suggests that a piece of negative news could be more salient than a good one, our results show that exposing participants with authentic, concise information about the appropriate use of tax revenues may lead to higher compliance. This result is consistent with previous evidence that politeness in expressing a difference of opinions in social media is more salient than online incivility, and therefore prompts a stronger behavioral response across participants in a trust game (Antoci et al., 2019). Our findings are also consistent with field studies showing that compliance is affected by unselfish (e.g., moral and social) motives (Bott et al., 2019; Hallsworth et al., 2017). However, our treatment is remarkably different from that administered by Bott et al. (2019); De Neve et al. (2021); Hallsworth et al. (2017) in the field, making our results not fully comparable. The field works in Bott et al. (2019); De Neve et al. (2021); Hallsworth et al. (2017) randomly treat taxpayers by including moral or fairness-related communications in reminder letters. Messages aim to recall that tax revenues serve to fund various types of public expenditure or that most citizens properly self-report their income. Instead, we treat experimental subjects with anecdotal stories about specific successful public sector projects in the spirit of Alesina et al. (2018). Finally, our result is consistent with studies suggesting that increasing the perceived trustworthiness of the public sector may raise citizens’ trust in institutions and compliance (Kasper et al., 2015)

The effect of positive news is not only highly statistically significant and economically sizable but even robust to further manipulation in terms of whether participants earned their money based on a real effort task or the exogenous decision of experimenters. This evidence indicates that the bias of information about public finance and policy matters more than the source of taxpayers’ income. The analysis of the intensive margin of evasion also suggests that, once individuals have decided to cheat on taxes, the effect of the negativity media bias does not differ substantially in size, which is always negligible, and significance across the neutral and the negative condition. Thus, in the first stage of taxpayers’ decision to comply, the bias of news about public finance seems to play a major role. From an economic perspective, the results of our experiment suggest that the satisfaction of taxpayers with the functioning of the public sector and the use of tax revenues is a critical driver of their compliance decisions. Citizens may feel intrinsically motivated to honestly declare their entire tax liability to the extent to which they perceive the outcomes of public policy as fair and legitimate as if a sort of psychological contract with tax authorities was in force (Feld & Frey, 2007). The belief that the government does not spend well citizens’ taxes may encourage them to reciprocate by refusing to pay their entire tax liability (Spicer & Lundstedt, 1976). If, instead, the belief prevails that the government uses its tax revenue to fund public goods and services adequately, taxpayers will be more willing to comply (Alm et al., 1993), even if they do not personally receive a full public good equivalent of their payments (Frey & Feld, 2002; Frey et al., 2004; Feld & Frey, 2007). Theories of the psychological contract imply a crucial role for information about public policy. However, citizens’ awareness of the efficiency and fairness of public institutions does not only depend on the government’s ability to fairly and adequately communicate about its use of tax revenues. It also relies on the media’s presentation of the efficiency and fairness of public institutions. Freedom in the provision, selection, and tone of information about the government is a cornerstone of democracy, and we do not advise any form of governmental interference with the media’s freedom of expression and critique. Our results instead suggest that more substantial attention to impartially reporting—also—good news (Iggers, 1999) may ultimately strengthen the psychological contract between taxpayers and the state by allowing the public sector to fully exploit its tax revenue potential, which could, in turn, be conducive to improvements in the provision of public goods and services.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we designed a framed laboratory experiment to study how the media bias in reporting about public finance and policy issues affects tax compliance in a repeated taxation game. The striking result of our study is that even minimal exposure to authentic news about the appropriate use of tax revenues by the public sector has a statistically significant and economically sizable effect on compliance. This finding suggests that what is at stake in taxpayers’ reporting decisions may not be merely the rational choice between risky assets in a portfolio under the constraint of tax audits and penalties. Instead, individuals may tend to reciprocate the behavior they observe in the government, and more in general in public institutions, as if they were bounded to them by a psychological contract (Frey & Feld, 2002; Feld & Frey, 2007). If citizens believe the government is pursuing its objectives with efficiency and fairness, they may be more intrinsically motivated to pay their taxes to contribute to the welfare of the community. Theories of the psychological contract do not explicitly point out the crucial role of communication and information in nudging taxpayers’ behavioral responses based on reciprocity. In our experiment, we highlighted and clarified this role. Overall, our results reveal that biased news can be a constant source of psychological priming influencing tax compliance decisions. The systematic tendency of the media to focus on negative news entails hidden social costs related to the government’s inability to fully exploit its tax revenue potential and meet its fiscal goals, with detrimental effects on the efficient provision of public goods and services. Our results suggest the relevance of testing the role of negative and positive news in the field, especially in transition countries characterized by limited trust in the media and public institutions. If confirmed, our findings suggest that treating taxpayers with anecdotal evidence about successful public sector projects could provide policymakers with effective and relatively inexpensive tools to promote tax compliance.

Notes

The exchange rate was 200 experimental monetary units (EMU) for one Czech Crown (CZK), with 5000 EMU \(\approx\) 1 EUR.

According to Czech law, tax evasion entails a pecuniary penalty and imprisonment from 3 months to 3 years. The rationale for our choice of the intense penalty factor is explained in Alm et al. (1999) A penalty multiplier of 5 or 25 times unpaid taxes may seem relatively large, since actual penalties for income tax fraud are currently 75% of unpaid taxes plus the unpaid taxes. However, it is important to recognize that the discovery of income tax fraud in one year leads to investigation of potential fraud in previous years. Further, when interest penalties and, more significantly, legal costs are also considered, a penalty multiplier far in excess of 5 does not seem unreasonable. Finally, a large penalty multiplier captures the type of catastrophic loss that the detection of evasion often brings. In theory, subjects could incur a bankruptcy-like scenario in any given round of the experiment. In such a case, experimenters told participants that they would set their earnings to 0 EMU (Schram & Onderstal, 2009), but losses would not be carried forward to the following rounds. However, this scenario occurred only in 2% of the total cases.

Given our parametrization, \(I\ge tR+\alpha t(I-R);R\ge \frac{\alpha tI-I}{(\alpha -1)t}\), to expect any positive earning in a given round, a risk-neutral agent should report an amount (R) that equals at least 37% of the actual individual income (I). Reporting 36% or less of the actual income would imply a net loss in case of an audit. The 37% lower bound serves as a reference point for potential gains and losses (net profit = 0) in the round. Given the existence of loss aversion, we assume that risk-neutral and risk-averse individuals would be more likely to declare their actual income, whereas risk-seeking and risk-loving individuals would be more likely to report 36% or less of their actual income.

See Casal and Mittone (2016) concerning the role of anonymity in income reporting games.

The limited redistribution of tax revenues is relatively standard in tax evasion games (e.g., Webley, 1991). The redistribution factor b has been found to be positively correlated with tax compliance (see Malezieux (2018) for a review of the literature). In our design, it serves to model Okun’s concept of redistribution as a “leaky bucket” (Okun, 1975). Redistribution may shrink society’s resources as it undermines incentives and entails deadweight losses related to structural inefficiencies in the tax collection and public transfers systems. According to Okun’s metaphor, redistributing resources is like transferring water in a leaky bucket. Consistently with this hypothesis our experiment also did not redistribute revenues from tax penalties to model the need to fund the auditing and redistribution system.

In order to deliver a reliable rating, the algorithm needs to process at least 100 words. Given this constraint, we provide the general score for the three corpora of headlines—negative, positive, neutral—while we cannot rate the individual headlines. Please refer to Appendix 1 for the complete list of translated headlines in detail.

In PPP, 1 EUR in the Czech Republic is equivalent to 1.45 EUR in Germany, as reference eurocountry.

We elicit individuals’ attitudes toward risk through a conventional multi-lottery choice task (Attanasi et al., 2018). A continuous index, ranging from 0 to 1, captures the increasing gradients of risk aversion: 0 indicates risk proneness, 1 high risk aversion.

The analysis shows that the effect of the positive treatment on tax revenues is sizably different from those detected under the other conditions. The same differential effect holds for the share of full compliers (Sect. 4.3) and compliance rate (Sect. 4.4). Given the number of subjects involved in our experiment—which is in line with several other experiments on tax evasion (e.g., Bernasconi et al., 2014; Castro & Rizzo, 2014; Casal et al., 2016; Fochmann & Wolf, 2019; Heinemann & Kocher, 2013), a post-hoc power analysis (Faul et al., 2007) detected \(\mathrm{power}<0.80\) for the statistically insignificant differences (\(\alpha >0.10\)) between the neutral and the negative conditions. The analysis suggests that to achieve conventional levels \(\alpha =0.05\) and \(\beta =0.20\), a sample size \(N>1000\) would be required. The complementary analysis of Cohen’s d effect size allows us to provide a more comprehensive interpretation of the outcomes whose tests display unconventional \(\beta\) values (Cohen, 1988; Ellis, 2010). Given the small values of the Cohen’s d, the effect sizes would be negligibly different between the negative and the neutral conditions also assuming conventional levels for \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), suggesting that tax compliance does not significantly differ between subjects exposed to negative news and the control condition.

This finding adds to the mixed evidence on the role of the source of income. Some studies show that the degree of effort required in experimental tasks could affect compliance behavior (e.g., Boylan & Sprinkle, 2001; Boylan, 2010b; Durham et al., 2014). Other works find no difference between the behavioral response of subjects who earned their income or were exogenously endowed by experimenters (e.g., Bühren & Kundt, 2013; Kirchler et al., 2009). As Malezieux (2018) highlights, the mixed evidence could be caused by interaction effects with other variables like audit probability, tax rate, or gender. We discuss these aspects more in depth in Sect. 4.3.

References

Abeler, J., Falk, A., Goette, L., & Huffman, D. (2011). Reference points and effort provision. American Economic Review, 101(2), 470–492. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.2.470

Abraham, M., Lorek, K., Richter, F., & Wrede, M. (2017). Collusive tax evasion and social norms. International Tax and Public Finance, 24(2), 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-016-9417-0

Agirdas, C. (2015). What drives media bias? New evidence from recent newspaper closures. Journal of Media Economics, 28(3), 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/08997764.2015.1063499

Alesina, A., & Angeletos, G. M. (2005). Fairness and redistribution. American Economic Review, 95(4), 960–980. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828054825655

Alesina, A., Miano, A., & Stantcheva, S. (2018). Immigration and redistribution. NBER Working Paper #24733. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w24733.pdf. https://doi.org/10.3386/w24733

Allingham, M. G., & Sandmo, A. (1992). Income and tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics, 1(3–4), 323–338.

Alm, J. (2012). Measuring, explaining, and controlling tax evasion: Lessons from theory, experiments, and field studies. International Tax and Public Finance, 19(1), 54–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-011-9171-2

Alm, J. (2019). What motivates tax compliance? Journal of Economic Surveys, 33(2), 353–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12272

Alm, J., Bernasconi, M., Laury, S., Lee, D. J., & Wallace, S. (2017). Culture, compliance, and confidentiality: Taxpayer behavior in the United States and Italy. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 140, 176–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2017.05.018

Alm, J., Bloomquist, K. M., & Mckee, M. (2015). On the external validity of laboratory tax compliance experiments. Economic Inquiry, 53(2), 1170–1186. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12196

Alm, J., Bloomquist, K. M., & McKee, M. (2017). When you know your neighbour pays taxes: Information, peer effects and tax compliance. Fiscal Studies, 38(4), 587–613. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-5890.12111

Alm, J., Jackson, B. R., & McKee, M. (1993). Fiscal exchange, collective decision institutions, and tax compliance. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 22(3), 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(93)90003-8

Alm, J., & Malézieux, A. (2020). 40 years of tax evasion games: A meta-analysis. Experimental Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-020-09679-3

Alm, J., Martinez-Vazquez, J., & McClellan, C. (2016). Corruption and firm tax evasion. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 124, 146–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2015.10.006

Alm, J., McClelland, G. H., & Schulze, W. D. (1999). Changing the social norm of tax compliance by voting. Kyklos, 52(2), 141–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.1999.tb01440.x

Altheide, D. L. (1997). The news media, the problem frame, and the production of fear. Sociological Quarterly, 38(4), 647–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1997.tb00758.x

Andreoni, J., Erard, B., & Feinstein, J. (1998). Tax compliance. Journal of Economic Literature, 36(2), 818–860. https://doi.org/10.3726/b15896

Andrighetto, G., Zhang, N., Ottone, S., Ponzano, F., D’Attoma, J., & Steinmo, S. (2016). Are some countries more honest than others? Evidence from a tax compliance experiment in Sweden and Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 472. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00472.

Antoci, A., Bonelli, L., Paglieri, F., Reggiani, T., & Sabatini, F. (2019). Civility and trust in social media. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 160, 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2019.02.026

Attanasi, G., Georgantzís, N., Rotondi, V., & Vigani, D. (2018). Lottery- and survey-based risk attitudes linked through a multichoice elicitation task. Theory and Decision, 84(3), 341–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-017-9613-0

Becchetti, L., Pelligra, V., & Reggiani, T. (2017). Information, belief elicitation and threshold effects in the 5X1000 tax scheme: A framed field experiment. International Tax and Public Finance, 24(6), 1026–1049. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-017-9474-z

Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76(2), 169–217. https://doi.org/10.1086/259394

Bernasconi, M., Corazzini, L., & Seri, R. (2014). Reference dependent preferences, hedonic adaptation and tax evasion: Does the tax burden matter? Journal of Economic Psychology, 40, 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2013.01.005

Bock, O., Baetge, I., & Nicklisch, A. (2014). Hroot: Hamburg registration and organization online tool. European Economic Review, 71, 117–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2014.07.003

Bosco, L., & Mittone, L. (1997). Tax evasion and moral constraints: Some experimental evidence. Kyklos, 50(3), 297–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6435.00018

Bott, K. M., Cappelen, A. W., Sørensen, E. O., & Tungodden, B. (2019). You ve got mail: A randomized field experiment on tax evasion. Management Science, 66(7), 2801–2819. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2019.3390

Boylan, S. J. (2010a). Prior audits and taxpayer compliance: Experimental evidence on the effect of earned versus endowed income. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 32(2), 73–88.

Boylan, S. J. (2010b). Prioraudits and taxpayer compliance: Experimental evidence on the effect of earned versus endowed income. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 32(2), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.2308/jata.2010.32.2.73

Boylan, S. J., & Sprinkle, G. B. (2001). Experimental evidence on the relation between tax rates and compliance: The effect of earned vs. endowed income. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 23(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.2308/jata.2001.23.1.75

Bruner, D. M., D’Attoma, J., & Steinmo, S. (2017). The role of gender in the provision of public goods through tax compliance. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 71, 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2017.09.001

Bühren, C., & Kundt, T. C. (2013). Worker or shirker—Who evades more taxes? A real effort experiment. MAGKS Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics, 2013(26)

Bühren, C., & Pleßner, M. (2014). The trophy effect. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 27(4), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.1812

Calvet Christian, R., & Alm, J. (2014). Empathy, sympathy, and tax compliance. Journal of Economic Psychology, 40(February 2014), 62–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2012.10.001

Cappella, J. N., & Jamieson, K. H. (1997). Spiral of cynicism: The press and the public good. Oxford University Press.

Carlsson, F., He, H., & Martinsson, P. (2013). Easy come, easy go: The role of windfall money in lab and field experiments. Experimental Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-012-9326-8

Casal, S., Kogler, C., Mittone, L., & Kirchler, E. (2016). Tax compliance depends on voice of taxpayers. Journal of Economic Psychology, 56, 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2016.06.005

Casal, S., & Mittone, L. (2016). Social esteem versus social stigma: The role of anonymity in an income reporting game. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 124, 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2015.09.014

Castro, M. F., & Rizzo, I. (2014). Tax compliance under horizontal and vertical equity conditions: An experimental approach. International Tax and Public Finance, 21(4), 560–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-014-9320-5

Cerqueti, R., Sabatini, F., & Ventura, M. (2019). Civic capital and support for the welfare state. Social Choice and Welfare, 53(2), 313–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-019-01185-7

Charness, G., Gneezy, U., & Halladay, B. (2016). Experimental methods: Pay one or pay all. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 131, 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2016.08.010

Charness, G., & Villeval, M. C. (2009). Cooperation and competition in intergenerational experiments in the field and the laboratory. American Economic Review, 99(3), 956–978. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.3.956

Chiang, C. F., & Knight, B. (2011). Media bias and influence: Evidence from newspaper endorsements. Review of Economic Studies, 78(3), 795–820. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdq037

Chiapello, M. (2018). BALANCETABLE: Stata module to build a balance table. Technical Report, Boston College, Department of Economics.

Cieliebak, M., Dürr, O., & Uzdilli, F. (2013). Potential and limitations of commercial sentiment detection tools. CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 1096, 47–58.

Clark, J. (2002). House money effects in public good experiments. Experimental Economics, 5, 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020832203804

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power calculations for the behavioural sciences. Routledge.

Corazzini, L., Cotton, C., & Reggiani, T. (2020). Delegation and coordination with multiple threshold public goods: Experimental evidence. Experimental Economics, 23(4), 1030–1068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-019-09639-6

Corazzini, L., Cotton, C., & Valbonesi, P. (2015). Donor coordination in project funding: Evidence from a threshold public goods experiment. Journal of Public Economics, 128, 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2015.05.005

Couttenier, M., Hatte, S., Thoenig, M., & Vlachos, S. (2019). The logic of fear: Populism and media coverage of immigrant crimes (Vol. 13496). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3369665

Cragg, J. G. (1971). Some statistical models for limited dependent variables with application to the demand for durable goods. Econometrica, 39(5), 829. https://doi.org/10.2307/1909582

Cyan, M. R., Koumpias, A. M., & Martinez-Vazquez, J. (2017). The effects of mass media campaigns on individual attitudes towards tax compliance; Quasi-experimental evidence from survey data in Pakistan. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 70, 10–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2017.07.004

Czech General Financial Directorate. (2016). The annual report of the Financial Administration of the Czech Republic in 2014. Retrieved from https://www.financnisprava.cz/assets/en/attachments/fa-financial-administration/vz_fs_2014.pdf

Danková, K., & Servátka, M. (2015). The house money effect and negative reciprocity. Journal of Economic Psychology, 48, 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2015.02.007

D’attoma, J. W., Volintiru, C., & Malézieux, A. (2020). Gender, social value orientation, and tax compliance. CESifo Economic Studies, 66(3), 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1093/cesifo/ifz016

De Neve, J. E., Imbert, C., Spinnewijn, J., Tsankova, T., & Luts, M. (2021). How to improve tax compliance? Evidence from population-wide experiments in Belgium. Journal of Political Economy, 129(5), 1425–1463.

Delhey, J., & Newton, K. (2005). Predicting cross-national levels of social trust: Global pattern or nordic exceptionalism? European Sociological Review, 21(4), 311–327.

DellaVigna, S., & Kaplan, E. (2007). The fox news effect: Media bias and voting. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 1187–1234. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.3.1187

Durante, R., Pinotti, P., & Tesei, A. (2019). The political legacy of entertainment TV. American Economic Review, 109(7), 2497–2530. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150958

Durham, Y., Manly, T. S., & Ritsema, C. (2014). The effects of income source, context, and income level on tax compliance decisions in a dynamic experiment. Journal of Economic Psychology, 40, 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2012.09.012

Dwenger, N., Kleven, H., Rasul, I., & Rincke, J. (2016). Extrinsic and intrinsic motivations for tax compliance: Evidence from a field experiment in Germany. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 8(3), 203–232. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20150083

Elejalde, E., Ferres, L., & Herder, E. (2018). On the nature of real and perceived bias in the mainstream media. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193765

Ellis, P. D. (2010). The essential guide to effect sizes. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511761676

Engel, C., & Moffatt, P. G. (2014). Dhreg, xtdhreg, and bootdhreg: Commands to implement double-hurdle regression. Stata Journal, 14(4), 778–797. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867x1401400405

Entman, R. M. (1994). Representation and reality in the portrayal of blacks on network television news. Journalism Quarterly, 71(3), 509–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909407100303

Entman, R. M. (2007). Framing bias: Media in the distribution of power. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00336.x

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (1998). Reciprocity and economics: The economic implications of Homo Reciprocans. European Economic Review, 42(3–5), 845–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(97)00131-1

Feld, L. P., & Frey, B. S. (2007). Tax compliance as the result of a psychological tax contract: The role of incentives and responsive regulation. Law and Policy, 29(1), 102–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9930.2007.00248.x

Fischbacher, U. (2007). Z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-006-9159-4

Fochmann, M., & Wolf, N. (2019). Framing and salience effects in tax evasion decisions—An experiment on underreporting and overdeducting. Journal of Economic Psychology, 72, 260–277.

Frey, B., & Feld, L. (2002). Deterrence and morale in taxation: An empirical analysis (No. 760).

Frey, B. S., Benz, M., & Stutzer, A. (2004). Introducing procedural utility: Not only what, but also how matters. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 160(3), 377–401. https://doi.org/10.1628/0932456041960560

Garz, M. (2014). Good news and bad news: Evidence of media bias in unemployment reports. Public Choice, 161(3–4), 499–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-014-0182-2

Garz, M., & Pagels, V. (2018). Cautionary tales: Celebrities, the news media, and participation in tax amnesties. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 155, 288–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2018.09.001

Gibson, R., & Zillmann, D. (1994). Exaggerated versus representative exemplification in news reports: Perception of issues and personal consequences. Communication Research, 21(5), 603–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365094021005003

Gualtieri, G., Nicolini, M., & Sabatini, F. (2019). Repeated shocks and preferences for redistribution. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 167, 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2019.09.016

Guerra, A., & Harrington, B. (2018). Attitude-behavior consistency in tax compliance: A cross-national comparison. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 156, 184–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2018.10.013

Hallsworth, M., List, J. A., Metcalfe, R. D., & Vlaev, I. (2017). The behavioralist as tax collector: Using natural field experiments to enhance tax compliance. Journal of Public Economics, 148, 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.02.003

Hamilton, J. T. (2011). All the news that’s fit to sell: How the market transforms information into news. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt7smgs

Harrington, D. E. (1989). Economic news on television. Public Opinion Quarterly, 53(1), 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1086/269139

Harrison, G., & List, J. (2004). Field experiments. Journal of Economic Literature, 42(4), 1009–1055.

Heinemann, F., & Kocher, M. G. (2013). Tax compliance under tax regime changes. International Tax and Public Finance, 20(2), 225–246.

Hester, J. B., & Gibson, R. (2003). The economy and second-level agenda setting: A time-series analysis of economic news and public opinion about the economy. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 80(1), 73–90.

Iggers, J. (1999). Good news, bad news. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429500145

Jacquemet, N., Luchini, S., Malezieux, A., & Shogren, J. F. (2020). Who’ll stop lying under oath? Empirical evidence from tax evasion games. European Economic Review, 124, 103369.

Kasper, M., Kogler, C., & Kirchler, E. (2015). Tax policy and the news: An empirical analysis of taxpayers’ perceptions of tax-related media coverage and its impact on tax compliance. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 54, 58–63.

Kepplinger, H. M., Geiss, S., & Siebert, S. (2012). Framing scandals: Cognitive and emotional media effects. Journal of Communication, 62(4), 659–681.