Abstract

Motivation decreases in higher education programs and is associated with dropout. Consequently, analyzing the development of motivation and subsequent student behavior is needed. We focused on factors that influence subject interest through the cognitive–rational aspect (university entrance grades) as well as the emotional aspect (perceived support from lecturers) and associated these variables with student dropout. We used data from 2301 co-op students in their first academic year collected by cross-sectional survey and university administration. We identified direct effects of interest, support, and university entrance grade on dropout rates and found that interest mediates lecturers’ perceived support and student dropout.

Résumé

La motivation diminue dans les programmes d'enseignement supérieur et est associée à l'abandon. Par conséquent, il est nécessaire d'analyser le développement de la motivation et le comportement des étudiants qui en découle. Nous nous sommes concentrés sur les facteurs qui influencent l'intérêt pour le sujet à travers l'aspect cognitif-rationnel (notes d'entrée à l'université) ainsi que l'aspect émotionnel (soutien perçu des professeurs) et avons associé ces variables à l'abandon des étudiants. Nous avons utilisé des données de 2 301 étudiants en alternance en première année universitaire collectées par enquête transversale et administration universitaire. Nous avons identifié des effets directs de l'intérêt, du soutien, et des notes d'entrée à l'université sur les taux d'abandon et avons découvert que l'intérêt joue un rôle de médiateur entre le soutien perçu des professeurs et l'abandon des étudiants.

Zusammenfassung

Die Motivation nimmt in höheren Bildungsprogrammen ab und ist mit dem Studienabbruch verbunden. Daher ist eine Analyse der Entwicklung der Motivation und des daraus resultierenden Studentenverhaltens erforderlich. Wir konzentrierten uns auf Faktoren, die das Fachinteresse durch den kognitiv-rationalen Aspekt (Universitätseingangsnoten) sowie den emotionalen Aspekt (von Dozenten wahrgenommene Unterstützung) beeinflussen und verknüpften diese Variablen mit dem Studienabbruch. Wir verwendeten Daten von 2.301 dualen Studenten im ersten Studienjahr, die durch eine Querschnittserhebung und Universitätsverwaltung gesammelt wurden. Wir identifizierten direkte Auswirkungen von Interesse, Unterstützung und Universitätseingangsnoten auf die Abbruchquoten und stellten fest, dass das Interesse die von Dozenten wahrgenommene Unterstützung und den Studienabbruch vermittelt.

Resumen

La motivación disminuye en los programas de educación superior y está asociada con el abandono. En consecuencia, es necesario analizar el desarrollo de la motivación y el comportamiento estudiantil subsiguiente. Nos enfocamos en factores que influyen en el interés del sujeto a través del aspecto cognitivo–racional (calificaciones de ingreso a la universidad) así como el aspecto emocional (apoyo percibido de los profesores) y asociamos estas variables con el abandono estudiantil. Utilizamos datos de 2301 estudiantes de co-op en el primer año académico recogidos por encuesta transversal y administración universitaria. Identificamos efectos directos del interés, apoyo y calificación de ingreso a la universidad en las tasas de abandono y descubrimos que el interés media el apoyo percibido de los profesores y el abandono estudiantil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The importance of interest in research has been undisputed and has a long history (Hidi, 2006; Krapp & Prenzel, 2011; Schukajlow et al., 2017). In education science, interest, in our research seen as linking positive cognitive and affective domains of a person for a subject (Krapp, 1999; Schiefele, 1996; Spinath, 2011), plays an important role (Renninger & Hidi, 2016; Wild et al., 2023a). Researchers analyzed correlations between interest and academic performance (Jansen et al., 2016). Other researchers highlighted the associations between instructor support, defined as the provision of fairness and friendliness of lecturer in our research (Danielsen et al., 2010) and interest (Lazarides et al., 2019). Furthermore, interest and intrinsic value are known to decrease in educational programs (Gaspard et al., 2020; Wild, 2023). For higher education, further research is needed, because longitudinal analyses have shown an association between intrinsic value and student dropout (Benden & Lauermann, 2022; Schnettler et al., 2020). High dropout rates in higher education worldwide indicated the high importance of this issue (Bäulke et al., 2021; OECD, 2013).

Our study sought to shed light on the mechanism linking the emergence of interest and the subsequent behavior of students in higher education systems (Xu et al., 2021). We were interested in modeling processes for an initial understanding of this topic and investigating the factors that keep motivation high long-term in educational programs. The most important period in which to analyze these research questions is the first academic year because the risk of dropping out is regarded as highest then (Chen, 2012; Neugebauer et al., 2019). Researchers also argued that, for better academic success, motivation is easier to change than social background or intelligence (van Maurice et al., 2014). Therefore, learning what higher education institutions can do to support interest and prevent dropout become crucial.

We focused our research on the following topic. In detail, we analyzed the cognitive–rational and emotional factors affecting interest, as well as student dropout in the first academic year. Only one aspect of each component from cognitive–rational and emotional factors was analyzed to keep the research questions and the working models simple. Overly complex correlations are barely tangible using empirical methods. Individual interest as an emotional factor was chosen because it helps to understand individuals’ motivation as well as people’s engagement in a particular activity on their own initiative (Renninger, 2000). Lecturer support was essential, because it mitigate subject interest decreasing during higher education programs (Wild et al., 2023a). We see our research as a first step toward further analysis in the future.

In Germany, the number of co-op students, a type of work-integrated learning program (Wild et al., 2023b), was continuously growing; in detail, it doubled to nearly 120,000 students in the last decade up to 2022 (Hofmann, 2023), but research on this group is less common than on non co-op students (Weich et al., 2017). Therefore, testing the robustness of the selected theoretical framework for this population was necessary (Weich et al., 2017). Reducing measurement errors and social desirability bias are also challenges for researchers. Therefore, desired data that had been collected and generated by the university administration and a survey were used (Fredricks et al., 2019).

Theoretical framework and empirical results

Research on interest in learning process dates back to the late nineteenth century and has gained increasing attention in recent decades (Boekaerts & Boscolo, 2002; Hidi, 2006; Krapp, 2007; Schukajlow et al., 2017). Important findings included the role that learners’ interests play in their attentiveness (Renninger & Hidi, 2019), motivation (Renninger & Hidi, 2017), engagement (Renninger & Hidi, 2017), the goals they pursue (Hulleman et al., 2008), cognitive functioning (Hidi et al., 2004), and teacher support (Dietrich et al., 2015). However, interest is an inconsistent factor. Interest that is stimulated briefly by external circumstances and subsides after the external stimuli have disappeared is distinct from enduring interest, which is developed and consolidated during the examination of an object or subject; i.e., individual and situational interest (Hidi & Harackiewicz, 2000; Schiefele, 2009; Schukajlow et al., 2017). Hidi and Renninger (2006) proposed a four-phase model of interest development: (1) triggered situational interest, (2) maintained situational interest, (3) emerging individual interest, and (4) well-developed individual interest, in which the first two phases entail situational interest and the remaining two represent individual interest. We focused on individual interest in this study.

Developing interest

According to the person–object–theory of interest (POI), individuals’ interaction with their environments generates interest (Krapp, 2002; Neher-Asylbekov & Wagner, 2023). In this approach, interest is combined with attention or engagement with particular content that might lead to activities (Krapp, 2005). Initially, situational interest arises, after which, individual interest may develop (Krapp, 2002).

In POI, a dual regulation system exists (Krapp, 2002, 2005; Xu, 2020). This system explains why people start an activity in a given domain and why they continue to do actions there. Interest development contains two important subsystems: conscious–cognitive factors and emotional factors. Conscious–cognitive factors are central to the formation of rational–analytic intentions. These are used to overcome obstacles blocking a purposeful activity or to accomplish an uninteresting but important task. Emotional factors are biological and are considered direct feedback for the functional state of the organism. These arise from the overall context to the actual requirements of the situation and are often associated with satisfying basic psychological needs (Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2017). Both factors encompass a variety of components that can be analyzed, and interest development exists when these components are positive (Krapp, 2005).

The effect of conscious–cognitive factors on interest has been shown empirically. Pässler et al. (2015) reported, in a meta-analysis, that the investigative (ρ = 0.28) and realistic (ρ = 0.23) interest dimensions of the Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising and Conventional (RIASEC) model are associated with intelligence. Further research showed associations between interest and academic performance (Robinson et al., 2019; van Maurice et al., 2014), and academic performance appears to predict dropout in higher education (Kehm et al., 2019).

Emotional factors have also been empirically analyzed and found to be relevant to the development of interest. The three basic psychological needs influence situational interest (Minnaert et al., 2011). Further research by Ferdinand (2014) in a secondary school demonstrated the impact of autonomy on the longitudinal development of subject interest, by six measurement points. Longitudinal analyses affirmed that teacher support affects interest (Dietrich et al., 2015; Lazarides et al., 2019). Basic psychological needs (Jeno et al., 2018; Teuber et al., 2021) and teacher support (Tvedt et al., 2021) also affect dropout intentions.

Interest and dropout

Motivation is an important component for success in higher education, such as grades (Richardson et al., 2012). Other research showed that motivational aspects, such as interest, positively influence educational decisions, e.g., sought a Master’s degree at a university (Harackiewicz et al., 2002). In contrast, amotivation, the lack of will to engage in an activity, seems to reduce student well-being (Bailey & Phillips, 2016). Furthermore, existing research showed decreased motivation, such as interest, in study programs overall (Benden & Lauermann, 2022; Schnettler et al., 2020; Wild, 2023).

We based our study on the situated expectancy–value theory (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020). This theoretical perspective supports our argument that expectations, as well as intrinsic, attainment, utility, and cost values, determine activity choice, performance, and engagement. This framework assumes that intrinsic value is seen as the expected enjoyment from doing a task, as well as the enjoyment someone experiences in doing the task (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020).

Empirical research underlined the relevance of interest to student dropout. Schnettler et al. (2020) collected data from students enrolled in mathematics and law three times during a single semester and showed a negative relationship between intrinsic values and dropout intention. Heublein et al. (2017) presented a correlation between decreasing subject interest and dropout in the academic fields of economy and social science at traditional universities. Findings supported by data from the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS) in Germany showed that the most important reasons for dropout are related to interest, expectations, and aspects of student performance (Behr et al., 2019). An analysis by Powers and Watt (2021) of vocational training, with data collected every 6 months for 3 years, showed that decreasing interest is associated with dropout intentions.

Research goals

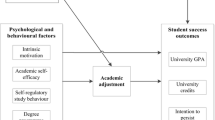

This study aimed to analyze the development of higher-education students’ interest and their subsequent behavior. The framework was the dual regulation system, based on POI, that perceived support from lecturers (emotional factor) and university entrance qualification grades (conscious–cognitive factor) as influencing subject interest (Krapp, 2002, 2005; Xu, 2020). In the context of the situated expectancy–value theory (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020), we assumed that subject interest, as an intrinsic value, affects student dropout (Benden & Lauermann, 2022; Schnettler et al., 2020). The empirical research presented above underlines these effects. Consequently, we have formulated the following four hypotheses (see also Figure 1):

Hypothesis 1

Greater perceived support from lecturers increases subject interest.

Hypothesis 2

Higher university entrance qualification grades increase subject interest.

Hypothesis 3

Subject interest decreases student dropout.

Hypothesis 4

The indirect effects of perceived support from lecturers and university entrance qualification grades on student dropout are mediated by subject interest.

Method

Participants and design

We used data collected in July 2016 from the first wave of the panel study “Study Process – Crossroads, Determinants of Success and Barriers during a Study at the DHBW” (Deuer & Meyer, 2020) to answer our research questions. The participants were students in the first academic year at Baden-Wuerttemberg Cooperative State University (DHBW) in Germany. At the end of the academic year (30 September 2016), the survey data were matched with data from the university’s administrative department.

The average age of the 2301 participating students was M = 22.12 years (SD = 3.02). In total, 1167 male (50.7%) and 1134 female students (49.3%) participated in the survey, and 58.3% were enrolled in business administration, 33.2% in engineering, and 8.5% in social work. Male students were more likely to study engineering (z = 10.2) and female students were more often enrolled in business administration (z = 4.9) and social work (z = 7.5), with a significant effect size (χ2 (2) = 372.10, p < 0.001, Cramérs V = 0.40). In addition, 36.6% of the participants had parents with at least one university degree.

The sampled students were enrolled in a co-op education program for Bachelor’s degrees. In this program, academic learning and practical experience alternate every 3 months as students move between university (the theory phase) and industry (the work phase). This co-op program lasts for 36 months and is worth 210 credits, according to the European Credit Transfer System (Wild & Neef, 2019).

Measures

The scale for perceived support from lecturers was validated with an adjusted short scale with four items (sample item: “How satisfied are you with the support and supervision provided by the lecturers in terms of assistance with learning and work difficulties?”) by Thiel et al. (2008). Participants rated the statements on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). The data for this scale were collected from the panel of participants. The scale’s reliability was considered acceptable (ω = 0.75).

We used university entrance qualification grades derived from the university’s administrative records. According to the German education system, scores from 1 (the highest score, equivalent to a grade A in Great Britain and the USA) to 4 (the lowest passing score, equivalent to a grade E in Great Britain or a grade D in the USA) were given. We recorded these values in our analysis, assuming that higher scores indicate better academic performance.

Subject interest was measured with an adjusted 5-item scale that was designed by Fellenberg and Hannover (2006). This scale showed acceptable reliability (ω = 0.74; sample item: “I cannot imagine a more interesting subject than my field of study”). Students rated the items on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

On the basis of Larsen et al. (2013), we defined students’ dropout from universities as “situations where a student leaves the university study in which (s)he has enrolled before having obtained a formal degree” (p. 5). Data from the university administration on dropout after the first academic year (ending 30 September 2016) were used and coded as 0 (no dropout) or 1 (dropout). Our sample included 130 students (5.6%) who dropped out after the first year of study.

Data analysis

We used SPSS (version 28) for our preliminary analysis and interpreted a p-value of less than 0.05 (two-tailed) as statistically significant. The results of the χ2 tests were interpreted through standardized residuals (treated as equivalent to z-scores), with those greater than 1.96 indicating cells containing significantly more observations than expected (Field, 2009; Schumacker, 2014). To estimate the effects of the t-tests, we used Hedges’ g instead of Cohen’s d because the former is adjusted for an unequal sample size (Barton & Peat, 2014). We interpreted Hedges’ g according to Cohen’s d as a small effect size from 0.20 to 0.49, medium from 0.50 to 0.79, and large at more than 0.80 (Cohen, 1988). The effect size of the correlation r in our analysis was considered small when r is 0.10–0.29, medium from 0.30–0.49, and large at ≥ 0.50 (Cohen, 1988). Kurtosis and skewness outside the range of −1 to +1 were considered problematic for the assumption of normal distribution (Hair et al., 2014).

In line with Schumacker and Lomax (2016), we used structural equation modeling to test our hypotheses in the R package lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) with the diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimator, because of binary variables in the model. We evaluated our model on the basis of model fit, viewing Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.06, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) ≥ 0.95, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) ≤ 0.08 as indicative of a good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The weighted root mean square residual (WRMR) was used to indicate a good model for cutoff at < 1 (Yu, 2002). Direct effects were used to test Hypotheses 1–3, and we used Hayes’ (2018) method of estimating bootstrapped conditional indirect effects (using 5000 replications) to test the mediator effect (Hypothesis 4).

Some missing values aroused in our sample of 2301 participants, with between 0% and 12% (M = 8.16%; SD 4.35) missing values for the variables. There were no missing values for 1881 participants (81.75% of the sample). Further missing values analysis indicated that Little’s (1988) test of missing completely at random (MCAR) was not significant (χ2 = 327.72, df = 291, p = 0.07). Therefore, no evidence suggested that the data were not MCAR. We replaced the missing data through multiple imputations that were conducted using the chained equations function of the mice package in R with 20 imputations (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011).

Results

Preliminary analysis

Table 1 presents descriptive information about the study variables, as well as the correlations between them. A small effect exists between perceived support from lecturers and subject interest (r = 0.27). All variables have left-skewed distributions inside the range of −1 to +1, which is not problematic.

We identified mean-level differences with lower measures for dropout than no dropout (see Figure 2). The t-test results showed small effects from perceived lecturer support, t(2299) = 5.29, p < 0.001, Hedges g = 0.48, and university entrance qualification grades, t(2299) = 5.20, p < 0.001, Hedges g = 0.47. However, a medium-sized effect was found for subject interest, with higher scores for students who did not drop out after their first academic year, t(2299) = 6.78, p < 0.001, Hedges g = 0.61.

Testing the hypotheses

To test our hypotheses, we used a structural equation model. The fit indices of the estimation showed a decent fit (χ2 = 214.927; df = 40; χ2/df = 5.373; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.969; TLI = 0.958; RMSEA = 0.044; SRMR = 0.044; WRMR = 1.682), indicated that the theoretical model appropriately represents the data (see Figure 3).

Model for the direct and indirect effect of perceived support through lecturers and university entrance qualification grade on drop out through subject interest. Coefficients are standardized beta weights for effects significant at the significance level of 0.05. Significant indirect effects at the significance level of 0.05 are presented with dash lines

The results of our analysis showed that support from lecturers (β = 0.28; p < 0.001) was positively associated with subject interest. In contrast, university entrance qualification grades (β = −0.02; p = 0.23) did not affect subject interest. Meanwhile, subject interest exerted a negative effect on dropout (β = −0.28; p < 0.001). There was also a direct association between perceived support from lecturers (β = −0.16; p < 0.001), university entrance qualification grades (β = −0.24; p < 0.001), and dropout.

Analysis of the 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effects confirmed the presence of mediation. Subject interest mediated the association between perceived support from lecturers and dropout (β = −0.13, 95% CI −0.19; −0.07). In contrast, subject interest did not mediate the effect that university entrance qualification grades exerted on dropout (β = 0.01, 95% CI −0.01; 0.03).

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the development of interest and its subsequent effects on study behavior of dropout. We investigated data collected in the context of the first academic year in higher education because the risk of dropout is highest during this period (Chen, 2012; Neugebauer et al., 2019). Our main findings were that perceived support from lecturers is associated with subject interest and reduces dropout after the first academic year. Furthermore, we have also shown that subject interest mediates between perceived support from lecturers and dropout. In contrast, university entrance qualification grades appear to have no effect on interest.

We approached our research with various expectations and theoretical frameworks. Our analysis was based on the framework of POI and the dual regulation system (Krapp, 2002, 2005; Xu, 2020). This allowed us to present several associations. On the one hand, we analyzed the association between an emotional factor, perceived support from lecturers, and interest, which confirmed Hypothesis 1. Our findings are in line with Dietrich et al.’s (2015) and Lazarides et al.’s (2019) empirical research. On the other hand, we assessed a conscious–cognitive factor, university entrance qualification grades, which has no association with interest. Hypothesis 2 was therefore not supported. This could be because we interviewed a population of co-op students who are selected by employers (Wild & Neef, 2019). However, the results are thought-provoking because the theoretical framework assumes that human behavior always operates on both emotional and conscious–cognitive levels (Krapp, 2002). According to situated expectancy–value theory (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020), we adopted the assumption that intrinsic values influence academic success. Our analysis confirmed Hypothesis 3. Current research (Benden & Lauermann, 2022; Schnettler et al., 2020) underlines these findings. Therefore, our findings address the demand for modeling the motivational process (Schiefele et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2021). We were able to identify an indirect association between perceived support from lecturers and dropout, via subject interest. Hypothesis 4 was therefore confirmed.

Our theoretical assumptions are largely confirmed by the empirical results. Emotional factors seem to be important for explaining the findings within this model. Other emotional aspects, such as the three basic psychological needs specified in self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2017), may have similar effects. However, aspects such as cost as defined in situated expectancy–value theory (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020) may also be important (Flake et al., 2018).

We can derive practical implications from our findings. One important element is the need to strengthen the perceived support that students receive from lecturers by improving the quality of teaching, which reduces dropout (Blüthmann et al., 2011; Georg, 2009), especially in the first year. Supporting students’ academic and social integration is another possible pathway. Several evidence-based approaches and arrangements offer methods to achieve this, such as remediation (Bettinger & Long, 2009; Tieben, 2019; Wild et al., 2024), considering the composition of groups in teaching courses (Booij et al., 2017), student–faculty mentoring (Sneyers & de Witte, 2018), and academic advising (Kot, 2014). A third way to support students’ motivation throughout their study programs is motivation programs that include coaching and the self-assessment of students’ strengths and weaknesses (Bettinger & Baker, 2014; Ćukušić et al., 2014; Stoll & Weis, 2022; Unterbrink et al., 2012). Van Maurice et al. (2014) highlighted the importance of strengthening motivation for academic success, noting that it is easier to change students’ motivation than their social backgrounds or intelligence.

Our research has several strengths. We were able to combine survey data and data from the university administration, reducing measurement error and social desirability bias. This is particularly important in research on dropout behavior because most studies, such as those of Dresel and Grassinger (2013) and Schnettler et al. (2020), only measured dropout intention, and Deuer and Wild (2019) demonstrated the low prognostic validity of dropout intention for assessing real dropout. Our theoretical assumptions fit the empirical data well, as the measures of fit in the structural equation model indicate. Our data were collected before the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic began in the year 2019, so the pandemic is not a potential source of bias. We tested our theoretical framework on the subpopulation of co-op students, who are becoming more important in Germany as their numbers increase (Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training, 2021).

The limitations of our research include that we used data from only one university with 12 campuses in one federal state of Germany. In addition, our sample’s generalizability to all students is limited because we collected data from co-op students who are chosen by companies; this may indicate the presence of a selection bias (Kupfer, 2013; Wild & Neef, 2019). Our study is cross-sectional, but longitudinal research is needed to create exact, informative modeling processes. The reliability (ω > 0.70) of our chosen psychometric instruments, perceived support from lecturers and subject interest, is acceptable (Viladrich et al., 2017). A further limitation of our research is that we focused on only one aspect, here interest in the context of motivation, in the multicausal factors of the dropout developing process (e.g., Heublein, 2014). Current research by Bäulke et al. (2021) suggested a motivational decision-making process with empirical evidence using the five named phases: (1) non-fit perception, (2) thoughts of quitting, (3) deliberation, (4) information search, and (5) final decision. However, at the time of data collection, the Bäulke et al. (2021) model was not published and we were unable to conduct research on this framework.

The use of the university entrance qualification grade as only one cognitive–rational aspect in our research is not satisfactory. Intelligence tests (Liepmann et al., 2007; Weiß, 2019), cognitive ability tests (Wo, 2010), situational judgement tests (Muck, 2013; Webster et al., 2020), or tests for performance at work (Danner, 2014), as well as in a broader sense lucrative prospects for a job or a high salary, are elements and tests that could represent cognitive–rational aspects and could be used to analyze this aspect. The same is true for the emotional aspects, as we only used the variable of perceived support from lecturers. In this aspect, other elements are needed to measure and test hypotheses, such as creativity, well-being, or joy. Further aspects are seen as relevant, such as learning opportunities in the practical phase (Böhn & Deutscher, 2021), curiosity (Bergold & Steinmayr, 2023; Mussel et al., 2012; Wild & Neef, 2023), organizational commitment to the company (Felfe et al., 2002; Wombacher & Felfe, 2017), and academic and social integration (Klein et al., 2019). Krötz and Deutscher (2022) and Böhn and Deutscher (2022) provided research and a summary for dropout in vocational education and training, and Kehm et al. (2019), Neugebauer et al. (2019) and Seidman (2012) for higher education.

Future research should investigate the sources of our results indicating different effect sizes in the associations we found, such as gender or study domain (Jansen et al., 2016; van Maurice et al., 2014), as well as other emotional components, such as the three basic psychological needs specified in self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2017), or practical experiences before university enrollment. In the context of situated expectancy–value theory, we argue that not only intrinsic value should be integrated into further research in this field, but also attainment value, utility value, costs, and expectations (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020). These variables should be analyzed for mediating variables in dropout processes. Our estimated model explains nearly 17% of the variance in dropout, which indicates that further variables that affect dropout, e.g., financial aspects, need to be investigated (Kehm et al., 2019; Neugebauer et al., 2019; Seidman, 2012). There is an existing consensus that dropout seems to be affected by different factors (Heublein, 2014). We see our work as a small step toward a better understanding of the factors affecting student dropout. Future work should investigate how to maintain university students’ motivation long-term to minimize dropout.

Conclusions

The present research investigated the development of individual interest and student dropout among the first academic year students in higher education from the frameworks of dual regulation system of POI and situated expectancy–value theory. The negative indirect effect of the emotional aspect of dual regulation system, in detail perceived support through lecturers, is associated with dropout via interest, whereas cognitive–rational aspect, here university entrance grades, is not associated with dropout via interest. Consequently, emotional aspects are seen as an important aspect for strengthening interest and counteracting dropout. As a result, future research projects, as well as actors at the university, such as student counseling, should focus more on emotional factors in interest development and handling with dropout.

Data availability

Data and syntax are available. Please contact the corresponding author.

References

Bailey, T., & Phillips, L. (2016). The influence of motivation and adaptation on students’ subjective well-being, meaning in life and academic performance. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1087474

Barton, B., & Peat, J. (2014). Medical statistics—A guide to SPSS, data analysis and critical appraisal (2nd ed.). Wiley.

Bäulke, L., Grunschel, C., & Dresel, M. (2021). Student dropout at university: a phase-orientated view on quitting studies and changing majors. European Journal of Psychology of Education., 37, 853–876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-021-00557-x

Behr, A., Giese, M., Kamdjou, H. D. T., & Theune, K. (2019). Motives for dropping out from higher education—An analysis of bachelor’s degree students in Germany. European Journal of Education, 56, 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12433

Benden, D. K., & Lauermann, F. (2022). Students’ motivational trajectories and academic success in math-intensive study programs: why short-term motivational assessments matter. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(5), 1062–1085. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000708

Bergold, S., & Steinmayr, R. (2023). The interplay between investment traits and cognitive abilities: investigating reciprocal effects in elementary school age. Child Development. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.14029

Bettinger, E., & Baker, R. B. (2014). The effects of student coaching: an evaluation of a randomized experiment in student advising. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36, 3–19.

Bettinger, E., & Long, B. (2009). Addressing the needs of under-prepared college students: does college remediation work? Journal of Human Resources, 44(3), 736–771. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.44.3.736

Blüthmann, I., Thiel, F., & Wolfgramm, C. (2011). Abbruchtendenzen in den Bachelorstudiengängen. Individuelle Schwierigkeiten oder Mangelhafte Studienbedingungen? [Drop out tendencies in bachelor's degree programmes. Individual difficulties or inadequate study conditions?]. Die Hochschule: Journal für Wissenschaft und Bildung, 20(1), 110–126.

Boekaerts, M., & Boscolo, P. (2002). Interest in learning, learning to be interested. Learning and Instruction, 12, 375–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(01)00007-X

Böhn, S., & Deutscher, V. K. (2021). Development and validation of a learning quality inventory for in-company training in VET (VET-LQI). Vocations and Learning, 14, 23–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-020-09251-3

Böhn, S., & Deutscher, V. (2022). Dropout from initial vocational education—A meta-synthesis of reasons from the apprentice’s point of view. Educational Research Review, 35, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100414

Booij, A., Leuven, E., & Oosterbeeck, H. (2017). Ability peer effects in university: evidence from a randomized experiment. Review of Economic Studies, 84, 547–578. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdw045

Chen, R. (2012). Institutional characteristics and college student dropout risks: a multilevel event history analysis. Research in Higher Education, 53(5), 487–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-011-9241-4

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

Ćukušić, M., Garača, Z., & Jadrić, M. (2014). Online self-assessment and students’ success in higher education institutions. Computers & Education, 72, 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.10.018

Danielsen, A. G., Wiium, N., Wilhelmsen, B. U., & Wold, B. (2010). Perceived support provided by teachers and classmates and students’ self-reported academic initiative. Journal of School Psychology, 48(3), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2010.02.002

Danner, D. (2014). Skala zur Beurteilung beruflicher Leistung [Scale for assessing professional performance]. Zusammenstellung Sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS). https://doi.org/10.6102/zis209

Deuer, E., & Meyer, T. (2020). Studienverlauf und Studienerfolg im Kontext des Dualen Studiums. Ergebnisse einer Längsschnittstudie [Study process and study success in cooperative study programmes. Results of a longitudinal study]. Bertelsmann.

Deuer, E., & Wild, S. (2019). Messinstrument zur Identifikation von Studienabbruchneigung im Dualen Studium (MISANDS) [Instrument of measurement to identify the tendency to drop out for cooperative student programmes (MISANDS)]. Zusammenstellung Sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS). https://doi.org/10.6102/zis265

Dietrich, J., Dicke, A.-L., Kracke, B., & Noack, P. (2015). Teacher support and its influence on students’ intrinsic value and effort: dimensional comparison effects across subjects. Learning and Instruction, 39, 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.05.007

Dresel, M., & Grassinger, R. (2013). Changes in achievement motivation among university freshman. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 1(2), 159–173.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: a developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859

Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (2021). Datenreport zum Berufsbildungsbericht 2021. Informationen und Analysen zur Entwicklung der Beruflichen Bildung [Data report on the vocational education and training programme 2021. Information and analyses on the development of vocational education and training.]. Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training.

Felfe, J., Six, B., Schmook, R., & Knorz, C. (2002). Commitment Organisation, Beruf und Beschäftigungsform (COBB) [Organisation, occupation and form of employment]. Zusammenstellung Sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS). https://doi.org/10.6102/zis9

Fellenberg, F., & Hannover, B. (2006). Easy come, easy go? psychological causes of students’ drop out of university or changing the subject at the beginning of their study. Empirische Pädagogik, 20(4), 381–399.

Ferdinand, H. D. (2014). Entwicklung von Fachinteresse. Längsschnittstudie zu Interessenverläufen und Determinanten Positiver Entwicklung in der Schule [Development of subject interest. Longitudinal study on interest trajectories and determinants of positive development at school]. Waxmann.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). Sage.

Flake, J. K., Barron, K. E., Hulleman, C., McCoach, B. D., & Welsh, M. E. (2018). “Measuring cost: the forgotten component of expectancy-value theory”: corrigendum. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 54, 309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.05.001

Fredricks, J. A., Hofkens, T. L., & Wang, M.-T. (2019). Addressing the challenge of measuring student engagement. In K. A. Renninger & S. E. Hidi (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of motivation and learning (pp. 689–712). Cambridge University Press.

Gaspard, H., Lauermann, F., Rose, N., Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2020). Cross-domain trajectories of students’ ability self-concepts and intrinsic values in math and language arts. Child Development, 91(5), 1800–1818. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13343

Georg, W. (2009). Individual and institutional factors in the tendency to drop out of higher education: a multilevel analysis using data from the Konstanz student survey. Studies in Higher Education, 34(6), 647–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802592730

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Tauer, J. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2002). Predicting success in college: a longitudinal study of achievement goals and ability measures as predictors of interest and performance from freshman year through graduation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(3), 562–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.3.562

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Heublein, U. (2014). Student drop-out from German higher education institutions. European Journal of Education, 49(4), 497–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12097

Heublein, U., Ebert, J., Hutzsch, C., Isleib, S., König, R., Richter, J., & Woisch, A. (2017). Zwischen Studienerwartungen und Studienwirklichkeit: Ursachen des Studienabbruchs, Beruflicher Verbleib der Studienabbrecherinnen und Studienabbrecher und Entwicklung der Studienabbruchquote an Deutschen Hochschulen [Between study expectations and study reality: causes of dropout, pathways of persons dropping out and development of the dropout rate at German higher education institutions] (Forum Hochschule, 1/2017). German Centre for Higher Education Research and Science Studies.

Hidi, S. (2006). Interest: a unique motivational variable. Educational Research Review, 1(2), 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2006.09.001

Hidi, S., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2000). Motivating the academically unmotivated: a critical issue for the 21st century. Review of Educational Research, 70(2), 151–179. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070002151

Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4

Hidi, S., Renninger, K., & Krapp, A. (2004). Interest, a motivational variable that combines affective and cognitive functioning. In D. Y. Dai & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Motivation, emotion, and cognition (pp. 89–118). Routledge.

Hofmann, S. (2023). AusbildungPlus. Duales Studium in Zahlen 2022. Trends und Analysen [AusbildungPlus. Cooperative Education in Figures. Trends and Analyses]. Verlag Barbara Budrich.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hulleman, C. S., Durik, A. M., Schweigert, S. A., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2008). Task values, achievement goals, and interest: an integrative analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 398–416. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.2.398

Jansen, M., Lüdtke, O., & Schroeders, U. (2016). Evidence for a positive relation between interest and achievement: examining between-person and within-person variation in five domains. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 46, 116–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.05.004

Jeno, L. M., Danielsen, A. G., & Raaheim, A. (2018). A prospective investigation of students’ academic achievement and dropout in higher education: a self-determination theory approach. Educational Psychology, 38(9), 1163–1184. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1502412

Kehm, B. M., Larsen, M. R., & Sommersel, H. B. (2019). Student dropout from universities in Europe: a review of empirical literature. Hungarian Educational Research Journal, 9(2), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1556/063.9.2019.1.18

Klein, D., Schwabe, U., Stocké, V. (2019). Studienabbruch im Masterstudium. Erklären Akademische und Soziale Integration die Unterschiedlichen Studienabbruchintentionen zwischen Master- und Bachelorstudierenden? [Dropping out of a Master’s Programme. Do academic and social integration explain the different intentions to drop out between Master’s and Bachelor’s students?]. In M. Lörz & H. Quast (Eds.), Bildungs- und Berufsverläufe mit Bachelor und Master [Educational and career paths with Bachelor’s and Master’s Degrees] (pp. 273–306). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-22394-6_9

Kot, F. C. (2014). The impact of centralized advising on first-year academic performance and second-year enrollment behavior. Research in Higher Education, 55, 527–563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-013-9325-4

Krapp, A. (1999). Interest, motivation and learning: an educational-psychological perspective. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 14, 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173109

Krapp, A. (2002). Structural and dynamic aspects of interest development: theoretical considerations from an ontogenetic perspective. Learning and Instruction, 12, 383–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(01)00011-1

Krapp, A. (2005). Basic needs and the development of interest and intrinsic motivational orientations. Learning and Instruction, 15(5), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.007

Krapp, A. (2007). An educational-psychological conceptualisation of interest. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 7(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-007-9113-9

Krapp, A., & Prenzel, M. (2011). Research on interest in science: theories, methods, and findings. International Journal of Science Education, 33(1), 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2010.518645

Krötz, M., & Deutscher, V. (2022). Drop-out in dual VET: why we should consider the drop-out direction when analysing drop-out. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 14(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-021-00127-x

Kupfer, F. (2013). Duale Studiengänge aus Sicht der Betriebe – Praxisnahes Erfolgsmodell durch Bestenauslese [Cooperative education programmes from the point of view of companies—A practical success model through selection of the best]. Berufsbildung in Wissenschaft und Praxis, 42(4), 25–29.

Larsen, M. R., Sommersel, H. B., & Larsen, M. S. (2013). Evidence on drop out phenomena at universities. Danish Clearinghouse for Educational Research.

Lazarides, R., Gaspard, H., & Dicke, A.-L. (2019). Dynamics of classroom motivation: teacher enthusiasm and the development of math interest and teacher support. Learning and Instruction, 60, 126–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.01.012

Liepmann, D., Beauducel, A., Brocke, B., & Amthauer, R. (2007). Intelligenz-Struktur-Test 2000 R [Intelligence structure test 2000 R] (2nd ed.). Hogrefe.

Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

Minnaert, A., Boekaerts, M., de Brabander, C., & Opdenakker, M.-C. (2011). Students’ experiences of autonomy, competence, social relatedness and interest within a CSCL environment in vocational education: the case of commerce and business administration. Vocations and Learning, 4, 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-011-9056-7

Muck, P. M. (2013). Development of situational judgment tests: conceptual considerations and empirical findings. Zeitschrift Für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie, 57(4), 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1026/0932-4089/a000125

Mussel, P., Spengler, M., Litman, J. A., & Schuler, H. (2012). Development and validation of the German Work-Related Curiosity Scale. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000098

Neher-Asylbekov, S., & Wagner, I. (2023). Modelling of interest in out-of-school science learning environments: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Science Education, 45(13), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2023.2185830

Neugebauer, M., Heublein, U., & Daniel, A. (2019). Higher education dropout in Germany: extent, causes, consequences, prevention. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 22, 1025–1046. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-019-00904-1

OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2013). Education at a glance 2013: OECD indicators. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2013-en

Pässler, K., Beinicke, A., & Hell, B. (2015). Interests and intelligence: a meta-analysis. Intelligence, 50, 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2015.02.001

Powers, T. E., & Watt, H. M. G. (2021). Understanding why apprentices consider dropping out: longitudinal prediction of apprentices’ workplace interest and anxiety. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-020-00106-8

Renninger, K. A. (2000). Individual interest and its implications for understanding intrinsic motivation. In C. Sansone & J. M. Harackiewicz (Eds.), Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: the search for optimal motivation and performance (pp. 373–404). Academic Press.

Renninger, K. A., & Hidi, S. E. (2016). The power of interest for motivation and engagement. Routledge.

Renninger, K., & Hidi, S. (2017). The power of interest for motivation and engagement. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315771045

Renninger, K., & Hidi, S. (2019). Interest development and learning. In K. Renninger & S. Hidi (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of motivation and learning (pp. 265–290). Cambridge University Press.

Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026838

Robinson, K. A., Lee, Y.-K., Bovee, E. A., Perez, T., Walton, S. P., Briedis, D., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2019). Motivation in transition: development and roles of expectancy, task values, and costs in early college engineering. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(6), 1081–1102. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000331

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory. Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

Schiefele, U. (1996). Motivation und Lernen mit Texten [Motivation and Learning with Texts]. Hogrefe.

Schiefele, U. (2009). Situational and individual interest. In K. R. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 197–222). Routledge.

Schiefele, U., Köller, O., & Schaffner, E. (2018). Intrinsische und extrinsische motivation [Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation]. In D. H. Rost, J. R. Sparfeldt & S. R. Buch (Eds.), Handwörterbuch Pädagogische Psychologie [Handbook educational psychology] (5th ed.; S. 309−319). Beltz

Schnettler, T., Bobe, J., Scheunemann, A., Fries, S., & Grunschel, C. (2020). Is it still worth it? Applying expectancy-value theory to investigate the intraindividual motivational process of forming intentions to drop out from university. Motivation and Emotion. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-020-09822-w

Schukajlow, S., Rakoczy, K., & Pekrun, R. (2017). Emotions and motivation in mathematics education: theoretical considerations and empirical contributions. ZDM Mathematics Education, 49, 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-017-0864-6

Schumacker, R. E. (2014). Learning statistics using R. Sage.

Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2016). A Beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Routledge.

Seidman, A. (2012). College student retention: Formula for student success (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

Sneyers, E., & de Witte, K. (2018). Interventions in higher education and their effect on student success: a meta-analysis. Educational Review, 70, 208–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2017.1300874

Spinath, B. (2011). Lernmotivation [Motivation for Learning]. In H. Reinders, H. Ditton, C. Gräsel, & B. Gniewosz (Eds.), Empirische Bildungsforschung. Gegenstandsbereiche [Empirical Educational Research. Subject Areas.] (pp. 45–55). Springer

Stoll, G., & Weis, S. (2022). Online-self-assessments zur Studienfachwahl. Entwicklung - Konzepte – Qualitätsstandards. Springer

Teuber, Z., Jia, H., & Niewöhner, T. (2021). Satisfying students’ psychological needs during the COVID-19 outbreak in German higher education institutions. Frontiers in Education, 6, 679695. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.679695

Thiel, F., & Veit, S., Blüthmann, I., & Lepa, S. (2008, January). Ergebnisse der Befragung der Studierenden in den Bachelorstudiengängen an der Freien Universität Berlin. Sommersemester 2008 [Results of the Survey of Students in the Bachelor's Programs at Freie Universität Berlin. Summer term 2008]. https://www.geo.fu-berlin.de/studium/Qualitaetssicherung/Ressourcen/FU_bachelorbefragung_2008.pdf

Tieben, N. (2019). Remedy mathematics course participation and dropout among higher education students of engineering. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 22, 1175–1202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-019-00906-z

Tvedt, M. S., Bru, E., & Idsoe, T. (2021). Perceived teacher support and intentions to quit upper secondary school: direct, and indirect associations via emotional engagement and boredom. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 21(1), 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1659401

Unterbrink, T., Pfeifer, R., Krippeit, L., Zimmermann, L., Rose, U., Joos, A., Hartmann, A., Wirsching, M., & Bauer, J. (2012). Burnout and effort-reward imbalance improvement for teachers by a manual-based group program. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 85(6), 667–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0712-x

van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(3), 1–67.

van Maurice, J., Dörfler, T., & Artelt, C. (2014). The relation between interests and grades: path analyses in primary school age. International Journal of Educational Research, 64, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2013.09.011

Viladrich, C., Angulo-Brunet, A., & Doval, E. (2017). A journey around alpha and omega to estimate internal consistency reliability. Annals of Psychology, 33(3), 755–782. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.3.268401

Webster, E. S., Paton, L. W., Crampton, P. E. S., & Tiffin, P. A. (2020). Situational judgement test validity for selection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Education Review, 54, 888–902. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14201

Weiß, R. (2019). Grundintelligenztest Skala 2—Revision (CFT 20-R) mit Wortschatztest und Zahlenfolgentest [Basic Intelligence Test Scale 2—Revision (CFT 20-R) with Vocabulary Test and Number Sequence Test] (2nd ed.). Hogrefe

Weich, M., Kramer, J., Nagengast, B., & Trautwein, U. (2017). Differences in study entry requirements for beginning undergraduates in dual and non-dual study programs at Bavarian universities of applied sciences. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 20, 305–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-016-0717-z

Wild, S. (2023). Trajectories of subject-interests development and influence factors in higher education. Current Psychology, 42, 12879–12895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02691-7

Wild, S., & Neef, C. (2019). The role of academic major and academic year for self-determined motivation in cooperative education. Industry and Higher Education, 33(5), 327–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950422219843261

Wild, S., & Neef, C. (2023). Analyzing the associations between motivation and academic performance via the mediator variables of specific mathematic cognitive learning strategies in different subject domains of higher education. International Journal of STEM Education, 10, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-023-00423-w

Wild, S., Rahn, S., & Meyer, T. (2023a). Factors mitigating the decline of motivation among first academic year students: a latent change score analysis. Motivation and Emotion. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-023-10050-1

Wild, S., Rahn, S., & Meyer, T. (2023b). Dropout predictors in the academic fields of economics and engineering in cooperative education: an observation of the first academic year using cox regression. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 15(13), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-023-00152-y

Wild, S., Rahn, S., & Meyer, T. (2024). Participation in bridging courses and dropouts among cooperative education students in engineering. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science, and Technology, 12(2), 297–317.

Wo, J. Z. (2010). Stimulating information cognitive ability value test system and method. China National Intellectual Property Administration.

Wombacher, J. C., & Felfe, J. (2017). Dual commitment in the organization: effects of the interplay of team and organizational commitment on employee citizenship behavior, efficacy beliefs, and turnover intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.05.004

Xu, J. (2020). Individual and class-level factors for middle school students’ interest in math homework. Learning and Motivation, 72, 101673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2020.101673

Xu, C., Lern, S., & Onghena, P. (2021). Examining developmental relationships between utility value, interest, and cognitive competence for college statistics students with differential self-perceived mathematics ability. Learning and Individual Differences, 86, 101980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2021.101980

Yu, C.-Y. (2002). Evaluating cutoff criteria of model fit indices for latent variable models with binary and continuous outcomes. University of California.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures of the conducted study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by Baden-Wuerttemberg Cooperative State University (8 July 2015).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all students who participated in the study prior to their completion of the research questionnaires.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wild, S., Rahn, S. & Meyer, T. Interest and its associations with university entrance grades, lecturers’ perceived support, and student dropout. Int J Educ Vocat Guidance (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-024-09684-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-024-09684-5