Abstract

Research shows that in university education programs, students’ motivation decreases over time, which is associated with indicators of reduced academic success, such as student dropout rate. Consequently, researchers have analyzed motivation change and explored the options available to universities to maintain a high level of motivation among students. Using Person-environment fit theory, our research suggests that perceived support offered by lecturers and instructional quality influence students’ subject interest. We conducted a longitudinal design of 823 participants from Baden-Wuerttemberg Cooperative State University and estimated a latent change score model using data collected between the participants’ first and second academic years. Our findings suggest that perceived support from lecturers mitigated the decrease in subject interest. Moreover, our results support the hypothesis that universities can attenuate the decreasing change of subject interest from students. Our findings are contextualized with reference to contemporary research in the field and we offer practical suggestions for maintaining high motivation among students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The beginning of a study program at university leads to many new situations and challenges for students in their first academic year. This kind of transition means, first of all, a new learning environment (Briggs et al., 2012), sometimes revealing learning strategies ill-suited for rigorous scientific study program (Endres et al., 2021). Often this transition is also marked by disappointment due to high expectations (Grassinger, 2018). In the same way this transition could also lead to significant changes in life, for example “the first time of living away from home for an extended period” (Alsubaie et al., 2019, p. 484). In this process, social and academic requirements have to be adapted to the new environment, which could affect motivational aspects (Noyens et al., 2019). Researchers studying this period have found evidence of decreasing motivation, which is associated with the intention to drop out (Benden & Lauermann, 2022; Chen, 2012; Schnettler et al., 2020). In contrast, high motivation is associated with higher achievement in higher education (Schneider & Preckel, 2017) or continuing to master’s level study (Harackiewicz et al., 2002). From universities` point of view, this is very important because their reputation and revenue suffer as a result of high dropout rates (Beer & Lawson, 2016; Klein & Stocké, 2016).

For this reason, the question of how universities can maintain high motivation to ensure academic success is important to answer. For example, offering self-regulated learning programs motivation is a central linked to performance (Perels et al., 2022; Schmitz & Perels, 2011; Theobald, 2021). Researchers stated that other predictors of achievement (e.g., cognitive abilities or socioeconomic background) are hardly modifiable as opposed to motivational components (van Maurice et al., 2014). Using Person-environment fit theory (PEF; Rubach et al., 2022), our research aims to identify factors in the university context that influence motivation change, like instructional quality or perceived support of lecturers. In other words, we aim to analyse why some students experience a more significant motivational change than others. We focus on the first academic year.

Xu et al. (2021) emphasize that longitudinal research in higher education is needed for motivation analysis, despite challenges in data collection. It has been argued that administrative (or institutional) data should be used to support research concerning university students (Fredricks et al., 2019; Jansen et al., 2022), because most research is undertaken within the field of school research (Frenzel et al., 2010; Lazarides et al., 2019; Schwarzenthal et al., 2023; Wentzel, & Miele, 2016). To test the robustness of theories, researching subpopulations such as cooperative universities, which have doubled their enrollments in Germany to 120,000 in the last decade (Hofmann, 2023), provides welcome support. In cooperative education students rotate between academic learning at university (the theory phase) and work experience in a workplace of a company (the work phase). These students therefore have an employment contract with a company (Coll & Zegwaard, 2011; Wild & Neef, 2019). Kramer and colleagues (2011) demonstrate that cooperative students are more motivated in certain aspects compared to students at a traditional or applied sciences university. Our research intends to meet the research desiderata presented here.

Theoretical framework

The pioneering work of Lewin emphasised that human behaviour is a function of a person in their environment and contrasted with Freud and other contemporaries who focused almost exclusively on the role of the individual in explaining behaviour (Bowman, & Denson, 2014). The further development of this framework into the person-environment fit state (PEF), in line with the conclusions of Rubach et al. (2022), stated that the interaction between a person (P) and the environment (E) influences the individual’s behaviour (B = f(P, E); summarised in Holland, 1997; Eccles et al., 1993). De Clercq et al. (2021a) identify a research gap in analysing the impact of the university environment on student behaviour, e.g. in the transition from school to university, and present initial results from recent years.

Using PEB framework, Phillips (2017) reported that educational learning settings are influenced by social conditions and social context; in other words, this framework can be described as socioculturally based. Good fits are thought to promote positive outcomes, in terms of students’ satisfaction with their university experience, psychological well-being (Gilbreath et al., 2011) and family relationships (Gutman & Eccles, 2007), while poor fits promote negative outcomes. Jansen and Kristof-Brown (2006) point out that not only one, but several dimensions of fit contribute simultaneously to an individual’s attitudes and behaviour. A poor fit with one or more environmental dimensions may be compensated by a good fit with another environmental dimension. Furthermore, the PEF focuses on longer-term developments and outcome (Jansen & Kristof-Brown, 2006).

An example of this is Holland’s (1997) framework, where PEF has also received recent attention (Bowman, & Denson, 2014). In his research, Holland proposes six categories of interest, the so-called RIASEC model (R: Realistic; I: Investigative; A: Artistic; S: Social; E: Enterprising; C: Conventional) and suggests that people who fit or match their interests with their actions and choices in an academic field of study are generally more satisfied, more productive and more likely to persist than those who mismatch. Research on Holland’s typology generally supports this prediction in both undergraduate majors and professional settings (Fonteyne et al., 2017; Putz, 2011). Further research into person-environment fit and academic success in higher education underlined the relevance of this framework and showed that study grades, perceived performance and study satisfaction were more strongly related to subjective fit than to subjective abilities (Bohndick et al., 2018). However, to our knowledge there is no longitudinal research into mitigating the decline of motivation against the background of person-environment fit in higher education and cooperative education.

Kahu and Nelson’s (2018) suggest a theoretical framework of structural influences from the university environment that affect the educational interface between the higher education institutions and the student, as well as impact student engagement and finally social and academic outcomes. Empirical findings support this framework and assumptions. De Clercq et al. (2021b) present findings that class size contributes to academic achievement. Further analysis by Bohndick et al. (2021) shows the influence of type of higher education as well as academic disciplines on students’ self-efficacy, goal commitment and volition. Schaeper (2019) also provides evidence of the importance of the influence of the university environment on student behaviour, as she finds that a cognitively activating learning environment significantly increases academic integration.

The advantage of utilizing the PEF lies in its ability to elucidate how environmental factors, such as the university institution, influences individual interest development. This impact can be attributed to factors like perceived instructional quality or lecturer support. Our study aims to investigate this research query.

Theoretical framework of interest development and predictors

In line with Hidi and Renninger (2006, p. 112), we understand interest as a motivational variable in terms of psychological state, where individuals, over a given time, engage or are predisposed to reengage, with particular classes of objects, events, or ideas. Krapp (2007) divides interest into situational interests, which exist for a limited period of time and are triggered by external incentives (situational interests), and individual interests, which refer to a characteristic of a person conceived as a stable disposition. The further theoretical assumptions of the Four-Phase Model of Interest development by Hidi and Renninger (2006) postulate a number of phases. Phase one is “Triggered Situational Interest” and phase two is “Maintained Situational Interest” (developing of situational interests). Phase three is “Emerging Individual Interest” and finally phase four is “Well-Developed Individual Interest” (the creation of individual interest). Our research focuses on subject interest as a type of individual interest, which falls within a late phase of this model.

Declining interest in programs both at schools (Gaspard et al., 2020) and at universities (Wild, 2022) is well-documented. In the following paragraphs, we discuss existing research in school and university contexts, using cross-sectional and longitudinal study designs that consider account the association of interest with gender, academic field, social background and performance. This is done because of the PEF framework, in which there are multiple dimensions of fit contribution, and one or more environmental dimensions may compensate for another, less developed environmental dimension (Jansen & Kristof-Brown, 2006). Unfortunately, results from higher education research are scarce, so we are forced to present results from additional educational institutions. In addition, results are available from many different areas, resulting in a relatively blurred picture of results.

Existing research on the influence of gender on interest has thus far been inconclusive. Research from schools is presented first, as it is better developed compared to higher education. The academic domain of mathematics is well represented in research. A study in Norway demonstrated lower interest for girls in middle school (Høgheim & Reber, 2019). Frenzel et al. (2010) reported similar findings in Bavarian schools, showing that although boys are more interested in mathematics than girls, both groups are characterized by declining trajectories. Krapp (2002) noted a trend towards a more rapid decline in interest in science-related subjects among girls than boys. In contrast, however, Dotterer et al. (2009) reported a more rapid decline in academic interest among boys. Different findings on gender trajectories in academic fields indicate the influence of the respective academic field on students’ interest. Renninger and Hidi (2017) studied the variable ‘decline of interest’ in one working-class school among grade 6 students in 12 subjects: Arts, English, Mathematics, Music, Physical Education, Science, and Social Studies. They concluded that classroom experiences (including instructional practices) influenced these results. Correlatively, Renninger and Su (2019) emphasize that disciplinary approach, content, activities, events or ideas influence the development of interest in a subject. Studies predicting the development of motivational values in relation to gender in higher education can be summarized as inconsistent. Studies, particularly in STEM education, had not found gender differences (Robinson et al., 2019; Kosovich et al., 2017), while other studies have demonstrated gender differences (Benden & Lauermann, 2022; Watt et al., 2012).

Research concerning interest and its development over time has demonstrated that social background is an influence factor. Frenzel et al. (2010), for example, show in their study of students’ interest in mathematics between grade 5 and grade 9, that higher values of family interest in mathematics correlate with higher values among students’ interest in mathematics. Similarly, Dotterer et al. (2009) report in school research that for the development of academic interests, students’ mothers’ educational expectations were positively related to students’ interests. Notably, students’ interest declined to a less significant extent when their fathers had greater educational attainment. Moreover, decline in student interest was slower when students’ mothers’ level of academic interest was higher. In a study of first-year university mathematics students Benden and Lauermann (2022) found that between the midpoint and the end of the semester the interest of students from wealthier families declined less than that of their peers.

Researchers have found an association between performance and interest, with one meta-analysis reporting an effect of r = .30 (Schiefele et al., 1993). However, Schiefele (2009) emphasized that the causal relation between interest and achievement has not yet been established. Van Maurice et al. (2014) conducted a longitudinal study in a primary school and found that grades influence interest but not vice versa. In their research on a secondary school, Scherrer et al. (2020) found that the associations between interest and achievement were reciprocal rather than unidirectional. Schiefele (2009) emphasizes, in line with findings from Dotterer et al. (2009), that for the lower secondary school level interest is either a nonsignificant or weak antecedent of achievement, while for post-secondary education, Rotgans and Schmidt (2011) conclude that situational interest impacts achievement. Meta-analysis in higher education shows that intrinsic motivation, which is included in the construct of interest, is associated with performance (Schneider & Preckel, 2017). In the following sections, interest and its association with perceived instructor support and perceived instructional quality will be discussed.

Interrelation between the development of interest and perceived lecturer support

We conceptualize lecturer support, in line with Lazarides et al. (2019) and Leenknecht et al. (2020), as the degree to which lecturers provide adaptive explanations, respond constructively to errors, adequately pace students’ learning and have a respectful and caring attitude to lecturer-student interactions both in the course environment and the educational institute. Given our use of PEF as a theoretical context, we assume that lecturer support is an important component that affects students’ behaviour. This is because we understand lecturer support as a social condition of the environment that influences individuals’ behaviour. Consequently, better perceived lecturer support is in line with good fits between individuals and their environments, leading to positive outcomes, such as increasing interest. Lazarides et al. (2019) note that only a few studies exist in this field, especially regarding perceived teacher support on a class-level and its effects on students’ academic outcomes.

Empirical results indicate the importance of perceived support in educational settings and confirm its effect on students’ academic outcomes. More specifically, research shows associations between perceived teacher support and student interest (Dietrich et al., 2015; Hettinger et al., 2022) as well as an indirect impact of teacher support on academic performance via motivation, as revealed by longitudinal studies (Affuso et al., 2022). Lazarides et al. (2019) present similar results, showing that teacher support mitigated the decline in students’ interest. Moreover, research has explored an association between perceived support and fewer instances of anti-immigrant attitudes (Miklikowska et al., 2019) as well as perceived support and decreased intention to quit (Tvedt et al., 2021a; Van Houtte & Demanet, 2016). Grew et al. (2022) underline the importance of teacher support on account of its reported association with higher engagement and achievement, based on their meta-analysis of approximately 200 studies (Roorda et al., 2017). Lei et al. (2018) found an association between teacher support and emotions in a meta-analysis. Nonetheless, the question of change of perceived support over time in education programs remains open. Wit et al. (2010) and Lazarides et al. (2019) report a decline, but Tvedt et al. (2021b) found no change in perceived support over time in their study. Research in higher education shows further effects of lecturer support on students’ engagement (Chan & Lee, 2023).

Interrelation between the development of interest and perceived instructional quality

In line with the approach taken by Holzberger et al. (2013), we characterized instructional quality as interaction between the three theoretical dimensions of cognitive activation, effective classroom management, and individual learning support. Meta-analyses, such as conducted by Schneider and Preckel (2017) for higher education and Seidel and Shavelson (2007) for school, show the effects of instructional quality on educational outcomes. As it is clear from the theoretical approach framework of PEF shown above, instructional quality is possibly a condition creating a good fit for the environment, in terms of influence on students’ behaviour. Consequently, positive outcomes follow, such as increasing interest.

Empirical research underlines these theoretical assumptions. Results show instructional quality is associated with interest in higher education (Schiefele & Jacob-Ebbinghaus, 2006) and school (Dorfner et al., 2018). Moreover, studies in school research by Yang and Kaiser (2022) and Klusmann et al. (2022) demonstrate the importance of instructional quality for academic outcome factors, such as performance (Atlay et al., 2019; Capin et al., 2022). A further aspect is the relationship between perceived instructional quality and perceived lecturer support. Initial empirical research into this relationship has been carried out by Blömeke and Klein (2013) for school and Hagenauer et al. (2022) for higher education.

Overall, regarding the state of contemporary research in this field, it should be noted that many studies refer to schools. As a result, there are still research gaps regarding the decline of motivation and the relevance of lecturer support, as well as instructional quality, for higher education. We respond to these desiderata with our study.

Objective

The aim of our research is to understand which institutional factors mitigate the decline of motivation in a higher education context. Using the theoretical framework of PEF, we assume that a higher scoring of education environments, as an indicator of better fit, influences students’ behaviour positively. In addition, we anticipate, based on this theoretical framework, that personal characteristics also affects students’ behaviour. Consequently, we integrate control variables into our model. More specifically, we postulate the following two hypotheses in our research.

Hypothesis 1

the decline of subject interest is associated with perceived lecturer support.

Hypothesis 2

the decline of subject interest is associated with perceived instructional quality.

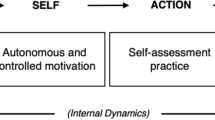

A visualized summary of our theoretical considerations, the empirical findings reported above, and our hypotheses are presented in Fig. 1. Furthermore, we control some personal characteristics that affect the cognitive variable of university entrance qualification grades in our research. Studies have found that gender (Voyer & Voyer, 2014; Baye & Monseur, 2016), academic field (Westrick et al., 2021) and social background (Sirin, 2005; Rodríguez-Hernández et al., 2020) influence student performance in various ways. Lastly, we explore the effects of demographic group differences (gender, academic field, social background and University entrance qualification grade), perceived lecturer support and perceived instructional quality on subject interest in a cross-sectional perspective.

Methods

Participants and design

Our longitudinal analysis is based on data from cooperative students in their first (July 2016) and second academic years (March 2017), from the cohort starting in 2015 of the panel study titled “Study Process – Crossroads, Determinants of Success and Barriers during a Study at the DHBW” (Deuer & Meyer, 2020). These timepoints were chosen, so that students would have completed a theory phase and a work integrated phase in each academic year. In this study, we invited all 34,000 enrolled students at Baden-Wuerttemberg Cooperative State University (DHBW) every year by email to participate in an online survey. The research group sent an email twice in an interval of two weeks to all students with a link to a questionnaire, inviting them to participate in the survey. Participation was voluntary and a privacy policy was adhered to. Every 50th student who answered more than one question received a coupon worth 10€. At the end of the project (September 30th, 2019), we matched the survey data with demographic data from the university’s administrative department.

In the annual survey in 2016 and 2017 all enrolled students of DHBW, approximately 34,000, were invited. In wave 1 there were 5,838 participations and in wave 2 there were 5,697 participations (Deuer & Meyer, 2020). Only 823 participated twice. The 823 participants had an average age of M = 21.12 years (SD = 2.69) in their first academic year. Regarding gender, the distribution was 455 female (55.3%) to 368 male (44.7%) students. 57.6% of the students were enrolled in business administration, 31.0% in engineering, and 11.4% in social work. We have chosen these academic disciplines for our research, because the aim of the panel study was to analyse the cooperative education system with these three faculties (Deuer & Meyer, 2020). However, the relevance of research on these fields of study can be justified in furtherways. On the one hand, economics, engineering and social work are among the most popular, i.e., most highly frequented, fields of study in Germany (Federal Statistical Office of Germany, 2022, p. 31). On the other hand, there is also a high demand for skilled workers in these fields. For example, a current and future shortage of skilled workers is diagnosed for social work (Vogler-Ludwig et al., 2016; Hickmann & Koneberg, 2022). Our data shows that more male students (z = 6.8; 73.3%) were enrolled in engineering, whereas more female students were studying business administration (z = 2.4; 63.5%) and social work (z = 4.7; 91.5%) with a significant effect size (χ2 (2) = 147.27, p < .001, Cramérs V = 0.42). In total, 39.1% of the participants had at least one parent with a university degree ( ≙ high social background).

The participating students in the sample were enrolled in three-year bachelor’s programs. This program is worth 210 credit points, measured according to the European Credit Transfer System. There is a precondition for this program, that students must have a university entrance qualification as well as a three year contract with their partner companies. Consequently, they earn a monthly salary in this program (including during the theoretical semesters) with a status as regular employees and were thereby entitled to vacation and insurance protection. This curriculum is highly standardized and so most of the students reach a degree in regular study time. There are few dropouts in this program and the dropout rate is below universities of applied science as well as universities. After graduation about 83% of cooperative students in this program are offered a permanent contract of employment, normally by their corporate partner (Nickel et al., 2022; Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg, 2016; Wild & Neef, 2019). Some people see this study program as a method for “selection of the best” by companies (Weich et al., 2017).

Measures

Subject interest

We measured subject interest as self-report using an adjusted instrument originally used by Fellenberg and Hannover (2006). All items of psychometric scales used in this research are listed in Table 1. The three items (sample item: My field of study matches my interests.) ranged from 1 (= strongly disagree) to 5 (= strongly agree). Reliability in academic year one (ω = 0.83) and academic year two (ω = 0.85) were recorded as good. Furthermore, we conducted a longitudinal invariance analysis for this instrument using cutoff criteria designed by Chen (2007), which indicated a change of Δ CFI ≤ 0.010 or RMSEA Δ CFI ≤ 0.015 in the models of configural, metric, scalar and strict invariance (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016; Widaman et al., 2010). The results confirm strict measurement invariance for time (see Table 2), which is a precondition for latent change analysis (McArdle, 2009).

Perceived lecturer support

In our study, perceived lecturer support was measured as self-report by an instrument adapted from Thiel et al. (2008) with four items. Reliability in our sample was seen as adequate (ω = 0.74; sample item: Are you satisfied with the support and supervision provided by the lecturers in terms of assistance with learning and work difficulties?). The scale ranged from 1 (= very dissatisfied) to 5 (= very satisfied).

Perceived instructional quality

The scale for perceived instructional quality was adapted from Thiel et al. (2008) and measured as self-report. The four items had tolerable reliability (ω = 0.75; sample item: The courses are well structured.). Measurement varied between 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree).

University entrance qualification grades

In the German education system, university entrance qualification grades range from 1 (the highest score, equivalent to a grade A in Great Britain and the United States) to 4 (the lowest passing score, equivalent to a grade E in Great Britain or a grade D in the United States). The university administration gave us access to this data. For a better interpretation of this variable, we have recoded this variable for our analyses in this study so that higher values mean better scores.

Data analyses and missing values

In our preliminary analysis through SPSS 29, using descriptive statistics we interpreted kurtosis and skewness outside the range of − 1 to + 1 as problematic for the assumption of normal distribution (e.g. Hair et al., 2014). Following Cohen (1988), we interpreted the effect size for Pearson’s correlation r (small is r = .10–29; medium is r = .30–49, and large is r ≥ .50), Cohen’s d for t-tests (small is d = 0.20–49; medium is d = 0.50–79, and large is d ≥ 0.80) and Cohen’s f for analyses of variance (small is f = 0.10–22; medium is f = 0.23–39, and large is f ≥ 0.40). In our research, a p-value of less than 0.05 (two-tailed) was deemed statistically significant.

Latent Change Score Models were used to test our hypothesis by MPUS Version 8.8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). Testing preconditions by longitudinal measurement invariance are reported in the chapter ‘measures’ and was performed using the R software package ‘semTools‘ (Jorgensen et al., 2022). We used a latent change score model because such models are largely free from measurement error and, consequently, inter-individual differences in intra-individual change can be estimated more precisely relative to models working with manifest scores (Lazarides et al., 2019; McArdle, 2009; Steyer et al., 1997). In line with McArdle (2009, p. 583), we fixed values (= 1) between the values of T1 and T2 to estimate the latent change score (Δ) (Rupprecht et al., 2019). Moreover, we set the parameter between their latent change score and their level at Time 2 to 1 for identifying the model (McArdle, 2009; Rupprecht et al., 2019). See Fig. 1 for details. In our analysis, we used the criteria of Hu and Bentler (1999) with RMSEA ≤ 0.06 and CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95, as well as SRMR ≤ 0.08 judged a good model fit.

Some values in our 1,646 measurements (two measurements for each participant) were missing. Variables had missing values between 0% and 8.3% (M = 4.85; SD = 2.72). In 1,418 cases (86.15% of the sample) and in 23,493 (95.15% of the sample) of 24,690 values, no values were missing. When the measurement of a single item or demographic variable was missing in a measurement point, we replaced the missing data using multiple imputations by chained equations of the software R package “mice” with 20 imputations (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011), taking into account the time variable using the multilevel structure of the data (Grund et al., 2018).

Results

Preliminary analysis

Descriptive analyses of the study variables are presented in Table 3, as well as the correlations between them. Perceived instructional quality is particularly striking because of Kurtosis = 1.74, which indicates a problem for normal distribution. The correlation between the two measurement points of interest is r = .71. Medium effects were recorded for the correlation between perceived lecturer support and perceived instructional quality (r = .46). All other correlations are r < .30. Further bivariate analysis of the manifest change score of interest that is based on the two measurement points indicates association with perceived lecturers support (r = –.07), perceived instructional quality (r = .01) and university entrance qualification grade (r = –.04).

An analysis based on t-tests showed no significant differences in university entrance qualification grades and gender (t(821) = 1.71, p = .087, d = 0.12) or social background (t(821) = 0.92, p = .357, d = 0.07). However, significant differences were found, as estimated by analysis of variance, in academic fields for university entrance qualification grades with medium effect size (F (2, 820) = 39.33, p < .001, f = 0.31), with the highest performance score for engineering (M = 4.06; SD = 0.54), followed by business administration (M = 3.85; SD = 0.58), with social work having the lowest performance (M = 3.48; SD = 0.46) (significant post hoc tests were conducted according to Scheffé for all three fields). Analysis of variance for repeated measurements showed a significant decline of subject interest from measurement one to measurement two with small effect size (F (1, 822) = 14.04, p < .001, f = 0.13).

Further preliminary analyses using analysis of variance as well as analysis of variance for repeated measures for the two measurement points tested the existence of interaction effects with different combination of factors gender, social background, university entrance qualification grade and academic field on subject interest, perceived lecturers support as well as perceived instructional quality. The presence of interaction terms should be excluded from latent change score models due to the assumption of consistent associations. However, there are no significant interaction terms with at least small effect size (Cohen’s f ≥ 0.10). See supplementary material for details. Consequently, the combination of analysed factors does not have a systematic impact on the way in which the teaching environment in higher education is experienced by students in our study.

Testing the hypotheses

To test our hypotheses, we estimated the latent change score model. The achieved fit was found to be acceptable (χ2 = 399.379; df = 134; χ2 / df = 2.980; p < .001; CFI = 0.944; TLI = 0.931; RMSEA = 0.049; SRMR = 0.044). Table 4 shows the results of influence factors on subject interest in academic year one and of change in subject interest from academic year one to academic year two, according to the research question.

The first analysis in Table 4 shows the influence of perceived instructional quality (β = 0.31; p < .001) and perceived lecturer support (β = 0.15; p = .001) on subject interest in measurement one. Notably, social work students showed higher subject interest than students of business administration (β = –0.22; p < .001). However, the explained variance of approximately 4% indicated that there are further variables that affect subject interest.

Next, an analysis of change in subject interest from T1 to T2 was conducted. Our results indicate that only perceived lecturer support (β = 0.18; p = .018) had a positive effect. In other words, high perceived lecturer support mitigated the decline of subject interest from measurement one to measurement two. Again, the explained variance of approximately 4% was analysed. The direction of the algebraic effect sign for the change score has shifted from minus to plus comparing the bivariate and manifest analysis in Table 3 to this multivariate and latent analysis in Table 4.

Discussion

Given the numerous challenges which new students at universities face (Dresel & Grassinger, 2013; Pillay & Ngcobo, 2010), it is particularly important to understand why students’ motivation decreases over time, especially in the first academic year (Benden & Lauermann, 2022; Wild, 2022). Determining the exact reasons for this is challenging is significant, because motivation is associated with many variables, such as student dropout (Schnettler et al., 2020; Wild et al., 2023a) and academic performance (Richardson et al., 2012; Schneider & Preckel, 2017). In this context, we analysed data with the aim of identifying variables that mitigated the decline of motivation, especially from an institutional perspective, with a focus on subject interest as a dependent variable. Most research in this context has been conducted in the context of schools, and a view from the higher education perspective is therefore needed.

Using the PEF framework, we assumed that personal characteristics as well as the characteristics of the environment – in this case, the university – interact to influence behaviour (Rubach et al., 2022). Our research centered on the university environment with a focus on the first academic year and subsequent development, up to the second academic year. In our initial explorative cross-sectional analysis, we identified associations between subject interest and the variables of perceived lecturers’ support, perceived instructional quality as well as academic subject based on data for the first academic year. These findings are in line with those of Dorfner et al. (2018) and Schiefele and Jacob-Ebbinghaus (2006), who report an association between perceived instructional quality and interest. Moreover, our findings likewise support those of Dietrich et al. (2015) and Hettinger et al. (2022) regarding perceived lecturers’ support and interest, respectively. The analysis of the latent change score from academic year one to academic year two shows a significant positive effect for perceived lecturers’ support, which confirms Hypothesis 1 and demonstrates that perceived lecturer support mitigated the decline of students’ subject interest from the first to the second academic year. Research from Lazarides et al. (2019) confirms this finding. In contrast, no significant influence on the change score could be found based on our analysis of perceived instructional quality. Consequently, Hypothesis 2 must be rejected.

Our study strengthens and contributes to the further development of PEF because our findings support its theoretical assumptions. This can be seen in the fact that we offer a contribution of analysing the importance of the environment in higher education as an influence factor and we do research on a subsample that has nearly doubled in Germany in the last decade from 2012 to approximately 120,000 cooperative students (Hofmann, 2023). Other empirical research based on person-environment-fit theories demonstrated similar findings in higher education on related topics, such as the conclusion of Buß (2019) that flexible study program structures improve the fit between students’ needs and universities’ offers. Further determinants are found in a high percentage of elective courses, a small number of teaching hours, and regularly distributed exams (Buß, 2019). Our research also shows that several environmental factors have an impact on interest, as shown in Table 4. Apparently, the assumption that multiple dimensions of fit contribute simultaneously to an individual’s attitudes and behaviour as well as that one or more environmental dimensions could compensate for another less developed environmental dimension seems to hold (Jansen & Kristof-Brown, 2006). In addition, the theory-based assumption that longer-term developments are particularly relevant in the context of the PEF seems to hold, as evidenced by the effect of perceived lecturer support on the latent change score of changing interest when there is a time difference of almost one year as seen in our research (Jansen & Kristof-Brown, 2006). Furthermore, our study gives hints that PEF can also be used for higher education research (Bohndick et al., 2018).

The perspective on environmental factors in the transition phase to higher education is significant and therefore needs to be considered in more detail. A possible starting point for this is the qualitative research by Trautwein and Bosse (2017), which highlights four critical requirements for students in the transition to higher education with the (1) organisational dimension in addition to the (2) personal requirements, the (3) content dimension and the (4) social dimension. For the organisational dimension, this research highlights as examples coping with the quality of teaching (e.g. lack of support from their lecturers), coping with examination conditions (e.g. tight examination schedules and assessment mode), coping with formal regulations as administrative hurdles, and adjusting organisational requirement with the personal challenges of student life.

This raises the question of how to strengthen lecturer support in a university setting. According to Metheny et al. (2008), and adjusted for university, more cooperation between guidance counsellors and lecturers should be conducted to benefit students´ development. Other suggestions from school research are working in small groups and giving students positive feedback and praise, both of which are key strategies to foster teacher–student relationships (Joyce & Early, 2014). Coaching or mentoring programs, as well as online self-assessments, are also seen as enabling understanding of students’ motivations from both an institutional perspective and from students’ self-perspective (Ćukušić et al., 2014; Sneyers & de Witte, 2018; Unterbrink et al., 2012).

One strength of our research is its use of demographic data from university administration, specifically, university entrance qualification grade, gender and academic fields. This enables us to limit measurement error and social desirability bias. Another strength of our research is our use of latent change score models, which, relative to manifest scores, are more precise as measurement error is reduced. Furthermore, our data was not impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, because they were collected in 2016 and 2017. The reliability of our study, according to McDonald’s omega (McDonald, 1999), shows an acceptable value of ω ≥ 0.70 (Viladrich et al., 2017) and the model fit of latent change score analysis is adequate (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Nonetheless, our research has limitations. The data used is from only one university, which has 12 campuses in one federal state of Germany. Consequently, our analysis can be seen as a kind of case study. The generalizability of our findings is also limited because the students are cooperative students chosen by companies, suggesting a possible selection bias (Kupfer, 2013). Our research explains nearly 4% of the variance of interest, which indicates that further indicators influence interest, such as the three basic psychological needs from self-determination theory, competence, autonomy and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2017). We measured interest with subject interest in a very general way and with only three items, and in further research, interest should be measured in a subject domain-specific focus, following the study of Jansen et al. (2016) conducted in a school context. Reliability for perceived instructor support and perceived instructional quality is ω ≤ 0.75. All the measurement instruments we use should be discussed and further developed in the academic discourse with regard to their quality (e.g. validity) in order to enable an even more precise measurement of teaching quality - although there are always limitations to measuring teaching practice through self-reporting (see comments below).

The response rate of 823 participants from 34,000 enrolled students at DHBW, that participate immediately two times successively in two surveys as a depend sample, was compared to the nearly 5,000 participants in these two surveys answering only one time (independent view) low and must be seen as a further limitation. This is due to the fact that the students could not be motivated to participate at two consecutive points in time. However, our results seem to be significant, because there exists, for example, a decrease in interest in our sample, as is known from previous research (Benden & Lauermann, 2022; Schnettler et al., 2020).

As already emphasized in the section ‘measures’, we use self-reports to measure subject interest, perceived lecturer support and perceived instructional quality in our research. According to Demetriou et al. (2015), there are limitations of using self-reporting. Individuals may provide invalid responses, as respondents may not answer truthfully or in a socially acceptable way, especially for sensitive questions. This is known as social desirability bias. Another problem is response bias, because participants may answer irrespective to the questions, such answering all questions with yes or no. Another challenge with self-reports is the clarity of the text in the items, which carries the risk of different interpretations of the questions. Being part of a research program is another factor influencing the response and a potential factor for invalid answers (Hawthorne effect). The lack of flexibility in scoring an answer is another limitation, as it limits the participants’ ability to express themselves and their feelings. However, in medicine (Short et al., 2009) or in crime research (Jolliffe, & Farrington, 2014), it is argued that the use of self-reports creates robust results. Sticca et al. (2017) reported same findings for grades. Consequently, first practical implications can be derived using self-reports, that need to be closely observed and evaluated.

Another limitation of our design is the method of collecting annual data, as it does not allow for pinpointing critical moments of motivational change or development within the first year. This is particularly problematic since motivational changes are particularly likely to occur in the first year or immediately after the start of the study program (Benden & Lauermann, 2022). However, we conduct annual surveys only in the spring after the first semester for research and cost-effectiveness reasons, and also to ensure that new students have completed a theoretical and work integrated phase before participating in the survey for the first time.

Our study opens avenues for further research. It is important to analyse the development of different motivational aspects relative to the independent variable of perceived lecturer support, such as the motivational aspect of the cost (Flake et al., 2015) in the context of situated expectancy–value theory (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020). Theories and results should be tested for robustness in subgroups analysis to elaborate specific prevention and intervention options based on moderator analysis (e.g., Wang & Ware, 2013), in terms, for example, of the growing population of non-traditional students in higher education (Wild et al., 2023b). Although research on motivation at universities is of growing interest (Xu et al., 2021), this field is underdeveloped relative to school research.

Conclusion

Motivation in higher education study programs decreases over time (Benden & Lauermann, 2022; Wild, 2022). The first year at university is particularly important, as students are confronted with many new situations (Dresel & Grassinger, 2013; Pillay & Ngcobo, 2010; Wild & Grassinger, 2023) and the probability of students dropping out is highest in this phase (Chen, 2012). In our study, we were able to show that perceived support from lecturer slows down the decline in motivation from the first to the second year of study. Future research should verify our results for robustness and analyse further motivational aspects.

Code availability

Syntax is available. Please contact the corresponding author.

Data availability

Data is available. Please contact the corresponding author.

References

Affuso, G., Zannone, A., Esposito, C., Pannone, M., Miranda, M. C., De Angelis, G., Aquilar, S., Dragone, M., & Bacchini, D. (2022). The effects of teacher support, parental monitoring, motivation and self-efficacy on academic performance over time. European Journal of Psychology of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-021-00594-6.

Alsubaie, M. M., Stain, H. J., Webster, L. A. D., & Wadman, R. (2019). The role of sources of social support on depression and quality of life for university students. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 24(4), 484–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1568887.

Atlay, C., Tieben, N., Hillmert, S., & Fauth, B. (2019). Instructional quality and achievement inequality: How effective is teaching in closing the social achievement gap? Learning and Instruction, 63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.05.008. Article 101211.

Baye, A., & Monseur, C. (2016). Gender differences in variability and extreme scores in an international context. Large-scale Assessments in Education, 4, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40536-015-0015-x.

Beer, C., & Lawson, C. (2016). The problem of student attrition in higher education: An alternative perspective. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 41(6), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2016.1177171.

Benden, D. K., & Lauermann, F. (2022). Students’ motivational trajectories and academic success in math-intensive study programs: Why short-term motivational assessments matter. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(5), 1062–1085. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000708.

Blömeke, S., & Klein, P. (2013). When s a school environment perceived as supportive by beginning mathematics teachers? Effects of leadership, trust, autonomy and appraisal on teaching quality. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 11, 1029–1048. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-013-9424-x.

Bohndick, C., Rosman, T., Kohlmeyer, S., & Buhl, H. M. (2018). The interplay between subjective abilities and subjective demands and its relationship with academic success. An application of the person—environment fit theory. Higher Education, 75(5), 839–854. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45116616.

Bohndick, C., Bosse, E., Jänsch, V. K., & Barnat, M. (2021). How different diversity factors affect the perception of First-Year requirements in Higher Education. Frontline Learning Research, 9(2), 78–95. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v9i2.667.

Bowman, N. A., & Denson, N. (2014). A missing piece of the departure puzzle: Student–institution fit and intent to persist. Research in Higher Education, 55(2), 123–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-013-9320-9.

Briggs, A. R. J., Clark, J., & Hall, I. (2012). Building bridges: Understanding student transition to university. Quality in Higher Education, 18(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2011.614468.

Buß, I. (2019). The relevance of study programme structures for flexible learning: An empirical analysis. Zeitschrift für Hochschulentwicklung, 14(3), 303–321. https://doi.org/10.3217/zfhe-14-03/18.

Capin, P., Roberts, G., Clemens, N. H., & Vaughn, S. (2022). When treatment adherence matters: Interactions among treatment adherence, Instructional Quality, and Student characteristics on reading outcomes. Reading Research Quarterly, 57(2), 753–774. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.442.

Chan, S. C., & Lee, H. (2023, online first). New ways of learning, subject lecturer support, study engagement, and learning satisfaction: an empirical study of an online teaching experience in Hong Kong. Education and Information Technologies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11605-y.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834.

Chen, R. (2012). Institutional characteristics and college student dropout risks: A multilevel event history analysis. Research in Higher Education, 53(5), 487–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-011-9241-4.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

Coll, R., & Zegwaard, K. E. (2011). International handbook for cooperative and work-integrated education: International perspectives of theory, research and practice (2nd ed.). World Association for Cooperative Education (WACE).

Ćukušić, M., Garača, Z., & Jadrić, M. (2014). Online self-assessment and students’ success in higher education institutions. Computers & Education, 72, 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.10.018.

De Clercq, M., Jansen, E., Brahm, T., & Bosse, E. (2021a). From Micro to Macro: Widening the investigation of diversity in the transition to Higher Education. Frontline Learning Research, 9(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v9i2.783.

De Clercq, M., Galand, B., Hospel, V., & Frenay, M. (2021b). Bridging contextual and individual factors of academic achievement: A multi-level analysis of diversity in the transition to higher education. Frontline Learning Research, 9(2), 96–120. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v9i2.671.

De Wit, D. J., Karioja, K., & Rye, B. (2010). Student perceptions of diminished teacher and classmate support following the transition to high school: Are they related to declining attendance? School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 21(4), 451–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2010.532010.

Demetriou, C., Uzun, B., & Essau, C. A. (2015). Self-Report Questionnaires. In R. L. Cautin & S. O. Lilienfeld (Eds.), The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology (pp. 1–6). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp507.

Deuer, E., & Meyer, T. (2020). Studienverlauf und Studienerfolg im Kontext des dualen Studiums. Ergebnisse einer Längsschnittstudie [Study process and study success in cooperative study programmes. Results of a longitudinal study]. WBV.

Dietrich, J., Dicke, A. L., Kracke, B., & Noack, P. (2015). Teacher support and its influence on students’ intrinsic value and effort: Dimensional comparison effects across subjects. Learning and Instruction, 39, 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.05.007.

Dorfner, T., Förtsch, C., & Neuhaus, B. J. (2018). Effects of three basic dimensions of instructional quality on students’ situational interest in sixth-grade biology instruction. Learning and Instruction, 56, 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.03.001.

Dotterer, A. M., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2009). The development and correlates of academic interests from childhood through adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(2), 509–519. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013987.

Dresel, M., & Grassinger, R. (2013). Changes in achievement motivation among University freshmen. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 1(2), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v1i2.147.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859.

Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & Iver, D. M. (1993). Development during adolescence. The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. The American Psychologist, 48(2), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.48.2.90.

Endres, T., Leber, J., Böttger, C., Rovers, S., & Renkl, A. (2021). Improving lifelong learning by fostering students’ learning strategies at University. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 20(1), 144–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725720952025.

Federal Statistical Office of Germany, & Statistisches Bundesamt. (2022). Bildung Und Kultur. Studierende an Hochschulen. Wintersemester 2021/2022. Fachserie 11 Reihe 4.1. Statistisches Bundesamt. [Education and culture. students at universities. Winter semester 2021/2022. Subject series 11 row 4.1.].

Fellenberg, F., & Hannover, B. (2006). Kaum begonnen, schon zerronnen? Psychologische Ursachenfaktoren für die Neigung Von Studienanfängern, das Studium Abzubrechen Oder das Fach zu wechseln [Easy come, easy go? Psychological causes of students´ drop out of university or changing the subject at the beginning of their study]. Empirische Pädagogik, 20(4), 381–399.

Flake, J. K., Barron, K. E., Hulleman, C., McCoach, B. D., & Welsh, M. E. (2015). Measuring cost: The forgotten component of expectancy-value theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 232–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.03.002.

Fonteyne, L., Wille, B., Duyck, W., & De Fruyt, F. (2017). Exploring vocational and academic fields of study: Development and validation of the flemish SIMON Interest Inventory (SIMON-I). International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 17, 233–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-016-9327-9.

Fredricks, J. A., Hofkens, L., & Wang, M. T. (2019). Addressing the challenge of Measuring Student Engagement. In K. A. Renninger, & S. E. Hidi (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Motivation and Learning (pp. 689–712). Cambridge University Press.

Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., Pekrun, R., & Watt, H. M. G. (2010). Development of mathematics interest in adolescence: Influences of gender, family, and school context. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(2), 507–537. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00645.x.

Gaspard, H., Lauermann, F., Rose, N., Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2020). Cross-domain trajectories of students’ ability self-concepts and intrinsic values in math and language arts. Child Development, 91(5), 1800–1818. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13343.

Gilbreath, B., Kim, T. Y., & Nichols, B. (2011). Person-environment fit and its effects on University students: A response surface methodology study. Research in Higher Education, 52, 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-010-9182-3.

Grassinger, R. (2018). Unfulfilled expectancies for success, unfulfilled study values and their relevance for changes in achievement motivation, achievement emotions and the intention to drop out in the first semester of a degree program. Zeitschrift für Empirische Hochschulforschung, 2(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.3224/zehf.v2i1.02.

Grew, E., Baysu, G., & Turner, R. N. (2022). Experiences of peer victimization and teacher support in secondary school predict university enrolment 5 years later: Role of school engagement. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(4), 1295–1314. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12500.

Grund, S., Lüdtke, O., & Robitzsch, A. (2018). Multiple imputation of missing data for multilevel models: Simulations and recommendations. Organizational Research Methods, 21(1), 111–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428117703686.

Gutman, L. M., & Eccles, J. S. (2007). Stage-environment fit during adolescence: Trajectories of family relations and adolescent outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 43(2), 522–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.522.

Hagenauer, G., Muehlbacher, F., & Ivanova, M. (2022). It’s where learning and teaching begins – is this relationship — insights on the teacher-student relationship at university from the teachers’ perspective. Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00867-z.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Tauer, J. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2002). Predicting success in college: A longitudinal study of achievement goals and ability measures as predictors of interest and performance from freshman year through graduation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(3), 562–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.3.562.

Hettinger, K., Lazarides, R., & Schiefele, U. (2022). Motivational climate in mathematics classrooms: Teacher self-efficacy for student engagement, student- and teacher-reported emotional support and student interest. ZDM – Mathematics Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-022-01430-x.

Hickmann, H., & Koneberg, F. (2022). Die Berufe mit den aktuell größten Fachkräftelücken, IW-Kurzbericht, Nr. 67 [The occupations with the currently largest skilled labour gaps, IW Short Report, No. 67.]. German economic institute.

Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of Interest Development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4.

Hofmann, S. (2023). AusbildungPlus. Duales Studium in Zahlen 2022. Trends und Analysen [TrainingPlus. Dual study in Fig. 2022. trends and analyses]. Verlag Barbara Budrich.

Høgheim, S., & Reber, R. (2019). Interesting, but less interested: Gender differences and similarities in mathematics interest. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63(2), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2017.1336482.

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments (3rd ed.). Psychological Assessment Resources.

Holzberger, D., Philipp, A., & Kunter, M. (2013). How teachers’ self-efficacy is related to instructional quality: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 774–786. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032198.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Jansen, K. J., & Kristof-Brown, A. (2006). Toward a multidimensional theory of person-environment fit. Journal of Managerial Issues, 18(2), 193–212. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40604534.

Jansen, M., Lüdtke, O., & Schroeders, U. (2016). Evidence for a positive relation between interest and achievement: Examining between-person and within-person variation in five domains. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 46, 116–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.05.004.

Jansen, T., Meyer, J., Wigfield, A., & Möller, J. (2022). Which student and instructional variables are most strongly related to academic motivation in K-12 education? A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 148(1–2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000354.

Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2014). Self-Reported Offending: Reliability and Validity. In: G. Bruinsma, G. & Weisburd, D. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice (pp. 4716–4722). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5690-2_648.

Jorgensen, T. D., Pornprasertmanit, S., Schoemann, A. M., & Rosseel, Y. (2022). semTools: Useful tools for structural equation modeling. R package version 0.5-6. [Computer software].

Joyce, H. D., & Early, T. J. (2014). The impact of School connectedness and teacher support on depressive symptoms in adolescents: A Multilevel Analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 39, 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.02.005.

Kahu, E. R., & Nelson, K. (2018). Student engagement in the educational interface: Understanding the mechanisms of student success. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1344197.

Klein, D., & Stocké, V. (2016). Studienabbruchquoten als Evaluationskriterium Und Steuerungsinstrument Der Qualitätssicherung Im Hochschulbereich [Dropout rates as an evaluation criterion and control instrument for quality assurance in higher education]. In D. Großmann, & T. Wolbring (Eds.), Evaluation Von Studium Und Lehre. Grundlagen, methodische herausforderungen und Lösungsansätze [Evaluation of study and teaching. Basics, methodological challenges and approaches to solutions] (pp. 323–365). Springer.

Klusmann, U., Aldrup, K., Roloff, J., Lüdtke, O., & Hamre, B. K. (2022). Does instructional quality mediate the link between teachers’ emotional exhaustion and student outcomes? A large-scale study using teacher and student reports. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(6), 1442–1460. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000703.

Kosovich, J. J., Flake, J. K., & Hulleman, C. S. (2017). Short-term motivation trajectories: A parallel process model of expectancy-value. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 49, 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.01.004.

Kramer, J., Nagy, G., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Jonkmann, K., Maaz, K., & Treptow, R. (2011). High class students in the universities, the rest in the other institutions of higher education – how students of different college types differ. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 14(3), 465–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-011-0213-4.

Krapp, A. (2002). Structural and dynamic aspects of interest development: Theoretical considerations from an ontogenetic perspective. Learning and Instruction, 12(4), 383–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(01)00011-1.

Krapp, A. (2007). An educational–psychological conceptualisation of interest. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 7(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-007-9113-9.

Kupfer, F. (2013). Duale Studiengänge aus Sicht Der Betriebe – Praxisnahes Erfolgsmodell durch bestenauslese [Cooperative Education programmes from the point of view of companies – A practical success model through selection of the best]. Berufsbildung in Wissenschaft Und Praxis, 42(4), 25–29.

Lazarides, R., Gaspard, H., & Dicke, A. L. (2019). Dynamics of classroom motivation: Teacher enthusiasm and the development of math interest and teacher support. Learning and Instruction, 60, 126–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.01.012.

Leenknecht, M., Snijders, I., Wijnia, L., Rikers, R. M. J. P., & Loyens, S. M. M. (2020). Building relationships in higher education to support students’ motivation. Teaching in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1839748.

Lei, H., Cui, Y., & Chiu, M. M. (2018). The relationship between teacher support and students’ academic emotions: A Meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2288. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02288.

McArdle, J. J. (2009). Latent variable modeling of differences and changes with longitudinal data. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 577–605. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163612.

McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Metheny, J., McWhirter, E. H., & O’Neil, M. E. (2008). Measuring perceived teacher support and its influence on adolescent Career Development. Journal of Career Assessment, 16(2), 218–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072707313198.

Miklikowska, M., Thijs, J., & Hjerm, M. (2019). The impact of Perceived Teacher support on Anti-immigrant attitudes from early to late adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(6), 1175–1189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-00990-8.

Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthen & Muthen.

Nickel, S., Pfeiffer, I., Fischer, A., Hüsch, M., Kiepenheuer-Drechsler, B., Lauterbach, N., Reum, N., Thiele, A. L., & Ulrich, S. (2022). Duales Studium: Umsetzungsmodelle Und Entwicklungsbedarfe [Cooperative Education: Implementation models and development needs]. WBV.

Noyens, D., Donche, V., Coertjens, L., van Daal, T., & Van Petegem, P. (2019). The directional links between students’ academic motivation and social integration during the first year of higher education. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-017-0365-6.

Perels, F., Benick, M., & Dörrenbächer-Ulrich, L. (2022). Selbstreguliertes Lernen [self-regulated learning]. In H. Reinders, D. Bergs-Winkels, A. Prochnow, & I. Post (Eds.), Empirische Bildungsforschung. Eine Elementare Einführung [Empirical Educational Research. An elementary introduction] (pp. 713–739). Springer.

Phillips, K. M. (2017). Professional Development for Middle School Teachers: The Power of Academic Choice in the Classroom to Improve Stage-Environment Fit for Early Adolescents. [Dissertation, Johns Hopkins University]. http://jhir.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/44717.

Pillay, A. L., & Ngcobo, H. S. B. (2010). Sources of stress and support among rural-based first-year university students: An exploratory study. South African Journal of Psychology, 40, 234–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124631004000302.

Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review, 41, 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004.

Putz, D. (2011). Measurement of vocational interests for vocational guidance: approaches to increase the criterion-related validity of interest congruence [Doctoral thesis, RWTH Aachen University]. University Library RWTH Aachen University. https://publications.rwth-aachen.de/record/63972/files/3550.pdf.

Renninger, K. A., & Hidi, S. (2017). Interest and content. In K. A. Renninger, & S. E. Hidi (Eds.), The Power of Interest for Motivation and Engagement (pp. 96–123). Routledge.

Renninger, K. A., & Su, S. (2019). Interest and its development, revisited. In R. M. Ryan (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation (2nd ed., pp. 204–226). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190666453.013.12.

Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026838.

Robinson, K. A., Lee, Y., Bovee, E. A., Perez, T., Walton, S. P., Briedis, D., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2019). Motivation in transition: Development and roles of expectancy, task values, and costs in early college engineering. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(6), 1081–1102. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000331.

Rodríguez-Hernández, C. F., Cascallar, E., & Kyndt, E. (2020). Socio-economic status and academic performance in higher education: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 29, 100305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100305.

Roorda, D. L., Jak, S., Zee, M., Oort, F. J., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2017). Affective teacher-student relationships and students’ engagement and achievement: A meta‐analytic update and test of the mediating role of engagement. School Psychology Review, 46(3), 239–261. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2017-0035.V46-3.

Rotgans, J. I., & Schmidt, H. G. (2011). Situational interest and academic achievement in the active-learning classroom. Learning and Instruction, 21(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.11.001.

Rubach, C., von Keyserling, L., Simpkins, S. S., & Eccles, J. S. (2022). Motivational Beliefs and Positive Achievement Emotions During COVID-19: A Person-Environment Fit Perspective in Higher Education. In H. Burgsteiner & G. Krammer (Eds.), Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic’s Distance Learning on Students and Teachers in Schools and in Higher Education – International Perspectives (pp. 100–125). Leykam.

Rupprecht, F. S., Dutt, A. J., Wahl, H. W., & Diehl, M. K. (2019). The role of personality in becoming Aware of Age-related changes. GeroPsych, 32(2), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000204.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory. Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

Schaeper, H. (2019). The first year in higher education: The role of individual factors and the learning environment for academic integration. Higher Education, 79, 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00398-0.

Scherrer, V., Preckel, F., Schmidt, I., & Elliot, A. J. (2020). Development of achievement goals and their relation to academic interest and achievement in adolescence: A review of the literature and two longitudinal studies. Developmental Psychology, 56(4), 795–814. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000898.

Schiefele, U. (2009). Situational and individual interest. In K. R. Wentzel, & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 197–222). Routledge.

Schiefele, U., & Jacob-Ebbinghaus, L. (2006). Student characteristics and perceived teaching quality as conditions of study satisfaction. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 20(3), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652.20.3.199.

Schiefele, U., Krapp, A., & Schreyer, I. (1993). Metaanalyse Des Zusammenhangs Von Interesse und schulischer leistung [Meta-analysis of interest and academic achievement]. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie Und Pädagogische Psychologie, 25(2), 120–148.

Schmitz, B., & Perels, F. (2011). Self-monitoring of self-regulation during math homework behavior using standardized diaries. Metacognition Learning, 6, 255–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-011-9076-6.

Schneider, M., & Preckel, F. (2017). Variables associated with achievement in higher education: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 143(6), 565–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000098.

Schnettler, T., Bobe, J., Scheunemann, A., Fries, S., & Grunschel, C. (2020). Is it still worth it? Applying expectancyvalue theory to investigate the intraindividual motivational process of forming intentions to drop out from university. Motivation and Emotion, 44, 491–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-020-09822-w.

Schwarzenthal, M., Daumiller, M., & Civitillo, S. (2023). Investigating the sources of teacher intercultural self-efficacy: A three-level study using TALIS 2018. Teaching and Teacher Education, 126, 104070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104070.

Seidel, T., & Shavelson, R. J. (2007). Teaching effectiveness research in the past Decade: The role of theory and Research Design in Disentangling Meta-Analysis results. Review of Educational Research, 77(4), 454–499. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654307310317.

Short, M. E., Goetzel, R. Z., Pei, X., Tabrizi, M. J., Ozminkowski, R. J., Gibson, T. B., Dejoy, D. M., & Wilson, M. G. (2009). How accurate are self-reports? Analysis of self-reported health care utilization and absence when compared with administrative data. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 51(7), 786–796. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181a86671.

Sirin, S. R. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 417–453. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075003417.

Sneyers, E., & de Witte, K. (2018). Interventions in higher education and their effect on student success: A meta-analysis. Educational Review, 70, 208–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2017.1300874.

Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg (2016). Ergebnisse der Absolventenbefragung 2013 an der Dualen Hochschule in Baden-Württemberg. Absolventinnen und Absolventen der Prüfungsjahre 2008 und 2011 [Results of the 2013 graduate survey at the Baden-Wuerttemberg Cooperative State University. Graduates of the examination years 2008 and 2011.]. Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg.

Steyer, R., Eid, M., & Schwenkmezger, P. (1997). Modeling true intraindividual change: True change as a latent variable. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 2(1), 21–33.

Sticca, F., Goetz, T., Bieg, M., Hall, N. C., Eberle, F., & Haag, L. (2017). Examining the accuracy of students’ self-reported academic grades from a correlational and a discrepancy perspective: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Plos One, 12(11), e0187367. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187367.

Theobald, M. (2021). Self-regulated learning training programs enhance university students’ academic performance, self-regulated learning strategies, and motivation: A meta-analysis. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 66, 101976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2021.101976.

Thiel, F., Veit, S., Blüthmann, I., & Lepa, S. (2008, January). Ergebnisse der Befragung der Studierenden in den Bachelorstudiengängen an der Freien Universität Berlin. Sommersemester 2008 [Results of the Survey of Students in the Bachelor’s Programs at Freie Universität Berlin. Summer term 2008]. https://www.geo.fu-berlin.de/studium/Qualitaetssicherung/Ressourcen/FU_bachelorbefragung_2008.pdf.

Trautwein, C., & Bosse, E. (2017). The first year in higher education—critical requirements from the student perspective. Higher Education, 73(3), 371–387. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26447620.

Tvedt, M. S., Bru, E., & Idsoe, T. (2021a). Perceived teacher support and intentions to quit Upper secondary school: Direct, and Indirect associations via Emotional Engagement and Boredom. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 65(1), 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1659401.

Tvedt, M. S., Bru, E., Idsoe, T., & Niemiec, C. P. (2021b). Intentions to quit, emotional support from teachers, and loneliness among peers: Developmental trajectories and longitudinal associations in upper secondary school. Educational Psychology, 41(8), 967–984. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2021.1948505.

Unterbrink, T., Pfeifer, R., Krippeit, L., Zimmermann, L., Rose, U., Joos, A., Hartmann, A., Wirsching, M., & Bauer, J. (2012). Burnout and effort-reward imbalance improvement for teachers by a manual-based group program. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 85(6), 667–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0712-x.

van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). Mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(3), 167. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v045.i03.

Van Houtte, M., & Demanet, J. (2016). Teachers’ beliefs about students, and the intention of students to drop out of secondary education in Flanders. Teaching and Teacher Education, 54, 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.12.003.

Van Maurice, J., Dörfler, T., & Artelt, C. (2014). The relation between interests and grades: Path analyses in primary school age. International Journal of Educational Research, 64, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2013.09.011.

Viladrich, C., Angulo-Brunet, A., & Doval, E. (2017). A journey around alpha and omega to estimate internal consistency reliability. Annals of Psychology, 33(3), 755–782. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.3.268401.

Vogler-Ludwig, K., Düll, N., & Kriechel, B. (2016). Arbeitsmarkt 2030. Wirtschaft und Arbeitsmarkt im digitalen Zeitalter. Prognose 2016. Kurzfassung Economix.

Voyer, D., & Voyer, S. D. (2014). Gender differences in scholastic achievement: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1174–1204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036620.

Wang, R., & Ware, J. H. (2013). Detecting moderator effects using subgroup analyses. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 14(2), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-011-0221-x.

Watt, H. M. G., Shapka, J. D., Morris, Z. A., Durik, A. M., Keating, D. P., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Gendered motivational processes affecting high school mathematics participation, educational aspirations, and career plans: A comparison of samples from Australia, Canada, and the United States. Developmental Psychology, 48(6), 1594–1611. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027838.

Weich, M., Kramer, J., Nagengast, B., & Trautwein, U. (2017). Differences in study entry requirements for beginning undergraduates in dual and non-dual study programs at bavarian universities of applied sciences. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 20(2), 305–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-016-0717-z.

Wentzel, K. R., & Miele, D. B. (2016). Handbook of Motivation at School (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315773384.

Westrick, P. A., Marini, J. P., & Shaw, E. J. (2021). Using SAT® Scores to Inform Academic Major-Related Decisions and Planning on Campus CollegeBoard.

Widaman, K. F., Ferrer, E., & Conger, R. D. (2010). Factorial Invariance within Longitudinal Structural equation models: Measuring the same construct across Time. Child Development Perspectives, 4(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00110.x.

Wild, S., & Neef, C. (2019). The role of academic major and academic year for self-determined motivation in cooperative education. Industry and Higher Education, 33(5), 327–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950422219843261.

Wild, S. (2022). Trajectories of subject-interests development and influence factors in higher education. Current Psychology, 42, 12879–12895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02691-7.

Wild, S., & Grassinger, R. (2023). The importance of achievement motivation, difficulties in self-regulation, and quality of instruction in students’ university drop out process. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(3), 758–772. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12590.

Wild, S., Rahn, S., & Meyer, T. (2023a). The relevance of basic psychological needs and subject interest as explanatory variables for student dropout in higher education — a German case study using the example of a cooperative education program. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 38, 1791–1808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-022-00671-4.

Wild, S., Rahn, S., & Meyer, T. (2023b). Comparing long-term trajectories in subject interest among non-traditional students and traditional students – An example from a cooperative higher education programme in Germany. Learning and Individual Differences, 101, 102250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2022.102250.