Abstract

Wellbeing describes how good life is for the person living it. Wellbeing comes in degrees. Subjective theories of wellbeing maintain that for objects or states of affairs to benefit us, we need to have a positive attitude towards these objects or states of affairs: the Resonance Constraint. In this article, we investigate to what extent subjectivism can plausibly account for degrees of wellbeing. There is a vast literature on whether preference-satisfaction theory – one particular subjective theory – can account for degrees of wellbeing. This is generally taken to be problematic. However, other subjective theories – namely, desire-satisfaction, judgment- and value-fulfillment theories – do not suffer from the same difficulties. We introduce two models of degrees of wellbeing a subjectivist can employ: the Relative and the Absolute Model, and defend the claim that both models face difficulties. In particular, we argue that a subjectivist theory should describe instances of depression as instances of low degrees of wellbeing. We also argue that a reduction of desires may sometimes improve one’s degree of wellbeing, an idea we call the Epicurean Intuition. We then argue that the Relative Model fails to account for the disbenefit of certain types of depression, while the Absolute Model fails to meet a central commitment of subjectivism – the Resonance Constraint – and is unable to accommodate the Epicurean Intuition. The upshot of the paper is that subjectivist theories cannot account for degrees of well-being in a plausible way.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Wellbeing describes how good life is for the person living it (Sumner 1996; Tiberius 2006). Wellbeing comes in degrees. For instance, we say that some lives are wonderful, and others we would not wish for our worst enemies; that lives can improve, but also deteriorate; and that some bad things that happen to people are much worse than other bad things.

Most of the philosophical debate about the nature of wellbeing has focused on the identification of the objects of wellbeing: which goods determine our degrees of wellbeing. Hedonism maintains that pleasure and pain constitute wellbeing; objective list theories maintain that there is a plurality of goods, such as achievement, friendship, and knowledge that constitute wellbeing; and desire-satisfaction theories state that the satisfaction of our desires constitutes wellbeing. It may be thought that once the objects of wellbeing are identified, the question of how degrees of wellbeing are identified is a settled issue. For hedonism, for example, a person’s degree of wellbeing is the same as a person’s degree of pleasure and pain (assuming that pleasure and pain are on the same scale). It has been recognized that for objective list theories, this issue is not quite as straightforward: a plural theory requires aggregation of degrees of different goods (degrees of knowledge, friendship, etc.) to arrive at a degree of wellbeing, but this aggregation plausibly is not a simple sum (see e.g. Griffin 1986; Sen 1980).

In this article, however, we will focus on the question how subjectivism about wellbeing can account for degrees of wellbeing. Subjectivism about wellbeing maintains that states of affairs, or objects, can only be good for someone if that person has a particular attitude towards that object. Examples of subjectivism are preference-satisfaction, desire-satisfaction (Heathwood 2006a; Bruckner 2013), value-fulfillment theories (Raibley 2012; Tiberius 2018), and judgment-fulfilment theories (Dorsey 2012). These theories maintain that desiring, preferring, valuing a state of affairs, or judging that state affairs to be good, will (under certain circumstances) make the realization of this state of affairs good for us.

Subjective theories are typically distinguished from hedonism. The satisfaction of a pro-attitude, such as a desire or value, need not be pleasurable (nor does it need to involve a conscious experience; see Parfit 1984’s stranger on the train example, 494). However, hedonism can be formulated as a subjective theory. Whether hedonism is a subjective theory or an objective theory depends on the nature of pleasure (Heathwood 2014). On subjective, or attitudinal, accounts of pleasure (Feldman 2002; Heathwood 2006a), hedonism is a subjective theory, on objective account (Smuts 2011; Bramble 2013), it is an objective theory of wellbeing. References to hedonism in this article are about hedonism as an objective theory, on which pleasure and pain determine someone’s degree of wellbeing independent of whether they hold a particular attitude towards pleasure and pain. Our argument, however, does apply to subjective versions of hedonism.

There is a vast literature on the quantitative structure of wellbeing for subjective theories of wellbeing that take one particular form: preference-satisfaction theories. This topic has been discussed in both the philosophical and economic literature in the form of a particular challenge to this theory: interpersonal comparisons of preference-satisfaction (see Hausman 1995; Greaves and Lederman 2018). However, interestingly, the quantitative structure of desire-satisfaction (Heathwood 2006a; Bruckner 2013), value-fulfilment (Raibley 2012; Tiberius 2018) and goodness judgment (Dorsey 2012) theories of wellbeing has not received much attention, while such theories have tools to address interpersonal comparisons that preference-satisfaction theories lack (see Greaves and Lederman 2018 and in particular; Barrett 2019).

Our aim in the article is as follows. We first describe how desire-satisfaction, value-fulfilment and judgment-fulfillment theories have tools available to account for quantitative wellbeing judgments that preference-satisfaction theories lack. We suggest there is a relative and an absolute way to account for degrees of wellbeing in such theories. We then argue that both run into significant substantive challenges. Our claim is that such theories cannot account for degrees of wellbeing in a plausible way.

A number of qualifications are in order. First, subjective theories of wellbeing are diverse. We focus on a broad category of such theories, in which a variety of pro-attitudes may ground wellbeing – desires, values, and goodness judgments. However, subjective theories of wellbeing may also vary because they add further conditions on the pro-attitudes that count towards wellbeing. Some subjective theories are idealized – counting only those pro-attitudes individuals would have had if they were well-informed and rational, or only those endorsed by second-order pro-attitudes, or only those that are about life as whole (Parfit 1984, 497). For the sake of simplicity, we will focus on simple versions of the theories, in which all pro-attitudes (of the right sort) count equally. However, in the objection section, we will address the objection that our argument relies on this assumption.

Second, throughout this article, we will speak of pro-attitude-satisfaction in periods of time, such as periods in which one is depressed, in a straightforward manner: except when otherwise stated, we will assume that the pro-attitudes had within these timeframes are constant – and their satisfaction or frustration occurs within these time frames. This avoids having to take a specific stance on the question when the satisfaction of a pro-attitude benefits someone (see Dorsey 2013; Bruckner 2013). However, we will get back to this assumption in the objection section.

Finally, this article is about degrees of wellbeing in a conceptual sense. There are important questions to be asked about how such degrees can be measured in practice (van der Deijl 2017; Alexandrova 2017; Hausman 2015), but those will not concern us here. For instance, when we say that pleasure and pain are clear quantitative concepts, we do not mean that we now have procedures that can reliably arrive at particular types of pleasure comparisons, but rather, we mean that we take it to be conceptually meaningful to say that we can experience more or less pleasure, and that I might, at a certain time, experience more pleasure than you.Footnote 1

Section II describes subjectivism, and one of its central commitments, in more detail. Section III describes the quantitative nature of wellbeing, and how objective theories of wellbeing may account for this. Section IV describes subjective theories and the tools desire-satisfaction and value fulfillment theories have available to account for degrees of wellbeing, over and above preference-satisfaction theories. Section V presents our main argument, section VI discusses objections, and section VII concludes.

It is important to stress one feature of the argument: we will start from the observation that wellbeing is a quantitative concept, with the following properties: it is both interpersonally and intrapersonally comparable, and, it is not a mere ordinal concept, but differences in wellbeing are (at least typically) comparable as well. Theories of wellbeing list goods that substantively constitute wellbeing. If, however, such goods cannot plausibly account for this quantitative structure, these goods cannot constitute wellbeing. We will further explain this in section III.

2 Subjectivism and the Resonance Constraint

As we have seen, subjectivist theories are diverse with respect to which attitudes ground wellbeing goods. But, while they are diverse, at the heart of subjectivism lies the Resonance Constraint – the view that something cannot benefit us if we are not attracted to this good (Dorsey 2017a).Footnote 2 This idea is generally seen as carrying a particularly strong intuitive support. This intuition is often expressed with a quote by Peter Railton:

“Is it true that all normative judgments must find an internal resonance in those to whom they are applied? While I do not find this thesis convincing as a claim about all species of normative assessment, it does seem to me to capture an important feature of the concept of intrinsic value to say that what is intrinsically valuable for a person must have a connection with what he would find in some degree compelling or attractive, at least if he were rational and aware. It would be an intolerably alienated conception of someone’s good to imagine that it might fail in any such way to engage him.” (Railton 1986, 9)

In a recent defense of the Resonance Constraint, Dale Dorsey describes it as follows:

The Resonance Constraint: “an object, event, state of affairs, etc., φ is good for an agent x only if x takes a valuing attitude (of the right sort) towards φ.” (Dorsey 2017b, 687)

The endorsement of this constraint is not only the distinguishing feature,Footnote 3 but its plausibility also the main motivation of subjectivist theories of welfare, and it may also be one of the main arguments in their favor. As Dorsey, who himself defends a subjectivist account of wellbeing, writes:

“Indeed, it is a little hard to see what might motivate subjectivism were one to jettison The Constraint. After all, there appear to be a litany of counterexamples to subjectivism (…). The subjectivist’s trump card in these cases is The Constraint and its appeal.” (Dorsey 2017b, 688)

The Resonance Constraint is formulated as a constraint on goods that can benefit a person. The Resonance Constraint is particularly significant for the discussion of degrees of wellbeing, because it denies that something a person does not have any pro-attitudes about can change their wellbeing positively. The Resonance Constraint is now only formulated as a constraint on things that are good. But, a similar constraint should be in place for things that are bad for someone.

What is crucial about the Resonance Constraint as Dorsey formulates it, is that it explicitly excludes the possibility that something that leaves someone cold or indifferent can benefit them. The opposite should hold if it comes to disbenefit. If Mark is indifferent about good φ, the Resonance Constraint should not only exclude the possibility that φ benefits Mark, but it should also exclude the possibility that good φ disbenefits him.

This leaves open two ways in which something may disbenefit someone. First, something, φ, may be bad if someone has a pro-attitude towards ¬φ, where φ is a state that necessarily is incompatible with ¬φ. For instance, if someone holds a pro-attitude towards world peace, war may be bad for them. Building on Kagan (2015), we note that there may be a difference between having a desire frustrated, and having an aversion, or contra-attitude realized.Footnote 4 So, second, things may be bad for someone if some someone has a contra-attitude, or an aversion, towards something. For instance, if I am strongly averse to war, war may be bad for me. While an aversion to war may often accompany a desire for peace, this is not necessary (Barrett 2019). This gives us the following constraint on disbenefit:Footnote 5

The Disbenefit Constraint: an object, event, state of affairs, etc. φ is bad for an agent x only if x takes a contra-attitude (of the right sort) towards φ, or if x takes a pro-attitude towards ¬φ.

3 What are Degrees of Wellbeing?

Above, we provided some common examples of quantitative comparisons of wellbeing. Such comparisons of welfare are commonplace in ethical practice (Hausman 1995), for instance, when we ask who the worst off is in certain context, or, more generally, how the welfare of different individuals compares, or if we want to know who will be disbenefited (harmed) by particular actions, and how much they will be disbenefited. The comparisons we will be most concerned with are the following:

-

Intrapersonal comparisons of wellbeing: individual A at time tx is better off than, as good off as, or worse off than individual A at time ty

-

Interpersonal comparisons of wellbeing: individual A at time tx is better off as, as good off as, or worse off than individual B at time ty.

-

(Interpersonal) unit comparisons of wellbeing: A change in the wellbeing of individual A at time tx was larger than, equal to, or smaller than a change in wellbeing of individual B at time ty, where tx may be equal to ty, and individual A may or may not be equal to individual B.

We take these claims to be generally meaningful, maintain that they in principle have truth conditions. Some people are truly better off than others, and some bad things that happen to Anne are truly worse than other things that happen to Bob. We therefore hold that theories of wellbeing should be able to provide plausible comparisons. Some particular theories of wellbeing may allow for incommensurability of welfare states, in which case there may be no truth conditions for certain specific wellbeing comparisons. Even so, whenever a theory of wellbeing makes such judgments of incommensurability, they should be plausible.

Because we take unit comparisons of wellbeing to, at least sometimes, have truth conditions, wellbeing is an interval quantity: it is meaningful to say that some benefit (or harm) that someone has received (or incurred) is not as good (or bad) as some other benefit (or harm).

This has important implications for theorizing about wellbeing. If such types of wellbeing comparisons make sense, wellbeing must also be constituted by goods for which such comparisons make sense. To see this, consider the following three claims about interpersonal comparability:

-

1.

Wellbeing is interpersonally comparable

-

2.

Wellbeing is constituted (solely) by good X

-

3.

Good X is not interpersonally comparable

These claims are not jointly compatible. Here, we accept that the first is correct: some lives are better (or worse) than others. Therefore, if a good is not interpersonally comparable, it cannot (solely) constitute wellbeing. As we can replace “interpersonally” with “intrapersonally” or “cardinally” in premise 1 and 3, the same holds for intrapersonal and interval comparisons of wellbeing.

A further question is whether wellbeing has a natural zero-point. If that would be so, wellbeing would have a ratio structure. This means that we could meaningfully say that the welfare of someone – e.g. someone living in poverty – is half that of someone else – e.g. someone living in affluence. To what extent such a natural zero-point exists depends on the specific theory of wellbeing that we are considering. On the formulations of pro-attitude satisfaction we will be concerned with, wellbeing does have such a zero-point, and wellbeing can be understood as a ratio concept. However, the argument does not crucially depend on this.

3.1 Degrees of Wellbeing for Objective Theories

Before we look at the quantitative structure of subjective theories, we can briefly look at objective theories. How do objective theories account for degrees of wellbeing? Objective theories of wellbeing may identify wellbeing with a single wellbeing good, in case of monistic theories, or, in case of pluralistic theories, a set of wellbeing goods. For monistic theories, such as quantitative hedonism, the quantitative structure of wellbeing depends fully on the structure of this single good itself. The question whether there is a natural zero, and whether there are incommensurable welfare states, depends fully on the nature of pleasure.

On a simple account of pleasure and pain, on which the two are positive and negative space on a single dimension, such a zero-point exists – where the hedonic nature of one’s experience is neither pleasurable nor painful (or as painful as it is pleasurable) – wellbeing, for the hedonist, is simply a single dimension. While it may be difficult to empirically verify, it at least makes sense to say that the pleasure that I experience during my time at the beach is much higher than the pleasure that my sister experiences during her morning run. Quantitative hedonism may face a plethora of other problems (e.g. Lin 2016; van der Deijl 2019), however, the view is able to account for degrees of wellbeing in a fairly straightforward fashion.

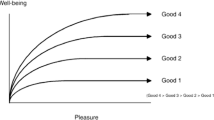

For pluralistic objective theories, or objective list theories, the question how to account for degrees of wellbeing not only depends on the quantitative structure of the goods on the lists – such as pleasure, friendship, achievement, etc. – but also on the way in which the different goods combine into an overall level of wellbeing. This structure may have different shapes, and identifying the right structure may be a challenging endeavor (Sen 1980; Heathwood 2015). Depending on the specific structure, there may, or may not be, a natural zero-point. Such a structure may allow for non-linear relationships, in which certain goods add more, or less, to our wellbeing, dependent on how much of other goods we have. Objective theories may also allow for incommensurable goods or incommensurable welfare states. There is a large variety of quantitative structures that pluralist theories of wellbeing may have, and discussing them in more detail would take us beyond the scope of this article.

4 Wellbeing Comparisons for Subjectivists

Subjective theories come in different forms. In their most common form, desire-satisfactionism, the view states that the satisfaction of desires (or other pro-attitudes) constitutes wellbeing. However, especially in economics, the view is often formulated in terms of preference-satisfaction: the satisfaction of preferences constitutes wellbeing. This difference in formulation makes an important difference to the quantitative structure of the theory. Preferences represent a dyadic relation: I cannot prefer apples on their own, with respect to apples, a preference over apples is always a preference of apples over something else (e.g. oranges). Desires are different, as I can have a desire for apples on their own. Desires, values, and judgments are monadic.

Preferences are sometimes seen as a representation of underlying desires.Footnote 6 In that sense, preferences can be seen as a different (more minimal) representation of desire. In that sense, it is not a substantively different theory from desire-satisfaction, but merely a different representation. However, this is not necessary. One can also see preference-satisfactionism as a distinct notion from desire-satisfactionism, one that does not presuppose that preferences are representations of desire (see Barrett 2019 for a discussion). References to preference-satisfaction here will be to preference-satisfactionism as a distinct theory of wellbeing, one that maintains that wellbeing is constituted by the satisfaction of one’s preferences.

The quantitative structure of preference-satisfaction – in particular its interpersonal comparability – has received much attention in the economic and philosophical literature. A central problem with the interpersonal comparison of preference-satisfaction is that preferences are merely relations over options, or states of affairs. These are most straightforwardly interpreted in an ordinal fashion: if I prefer to have an apple over an orange, having an apple is better for me than having an orange. However, it does not tell us whether an apple makes me much better off, or only mildly better off than in case I would have an orange. This structure of the theory allows comparisons of welfare within an individual for all options, but cannot result in comparisons between individuals. When I prefer grapes over apples over oranges, and you prefer grapes over oranges over apples—and I receive an apple, and you receive and orange, there is no comparison possible on an ordinal account of preference-satisfaction between my welfare and yours, as the differences between the different options are arbitrary. It is important to note that on the preference-satisfaction view, the reason we cannot compare these individuals is not epistemic – the reason is not that we do not have enough information – if it truly are preferences that constitute wellbeing, a description of preference relations contains all possibly relevant information (Hausman 1995).

The structure of preferences on its own does not allow for interpersonal comparisons, but preference-satisfaction may be normalized, such that it can be understood as an interval or ratio quantity. One way to do so, is to standardize preference-satisfaction as follows: for each individual, the option on top of their preference ranking is a assigned a 1, and the least preferred option a 0 (the zero-one rule, see Hausman 1995; Rossi 2011a), and interpret preference-satisfaction as distances from these. While such interpretations make it conceptually possible to compare individuals, they are typically regarded problematic for substantive reasons. In particular, for assigning too much importance to the “best” and “worst” options. If two people are doing equally well on such a scale before someone starts imaging a better “best” option, now that person is doing worse than the other (because their relative position has decreased). This is problematically arbitrary in the sense that merely imaging a better world should not make a difference to how good your life is for you (Hausman 1995; see Rossi 2011b, 276 for a different argument against the zero-one rule).

The core problem of interpersonal comparability of preference-satisfaction is well expressed in a recent paper by Hilary Greaves and Harvey Lederman:

“Agnes’s preferences, for example, determine the ranking of states of affairs which is relevant to considerations of her well-being; Brandon’s preferences determine a ranking of states of affairs which is relevant to considerations of his well-being. But neither Agnes’s preference ordering, nor Brandon’s, nor the pair of them taken together obviously provide the resources for comparisons between Agnes’s and Brandon’s well-being. The fact that Agnes is better off in one state than she would be in another (together with similar facts for Brandon) is not enough to determine whether Agnes is better off in that state of affairs than Brandon” (Greaves and Lederman 2017, 1164)

Thus, preference-satisfaction seems incomparable between individuals, because my and your preference-satisfaction are simply different things. We may nevertheless treat them as comparable, through a normalization, but that is generally taken to be problematically arbitrary (Barrett 2019).Footnote 7

Within the philosophical literature, recent defenses of subjectivism have typically not taken the form of preference-satisfactionism, but of desire-satisfaction (Heathwood 2006b; Bruckner 2013), value-fullfilment (Raibley 2012; Tiberius 2018), or judgment-satisfaction (Dorsey 2012). All these attitudes share a quantitative structure, even though their substantive differences may be significant. Hence, in the remainder, we will treat them similarly, and speak of pro-attitude satisfaction—where this can refer to desiring, valuing, and goodness judging attitudes.

Because their quantitative structure is different from the preference-structure, the challenge they face is different (see in particular Barrett 2019, but also; Greaves and Lederman 2018). Pro-attitudes – such as desires, values, or judgments – have different properties than preferences. These pro-attitudes exist on their own, and not merely in relation to other options, goods, or states of affairs. They have a strength, and an extent to which they are satisfied. Moreover, they have a natural zero-point: a point at which no pro-attitudes are at all satisfied.

Building on Barrett (2019), we can formalize this as follows. At a given time, a person has a set of z pro-attitudes, and each pro-attitude, i, has a certain strength, Di,t. We may also have a total of y aversions, or contra-attitudes, Ai,t, which are structurally the same as pro-attitudes, but which count negatively towards wellbeing when realized. Pro- and contra-attitudes may be realized, or frustrated. We can represent this with Si,t which is 1 if the pro- or contra-attitude is fully realized, and 0 if it is not at all realized. While some pro-attitudes may either be satisfied or frustrated – e.g. the desire that it will not rain at noon today – many other desires may be satisfied to a certain degree. A desire for world peace may not be fully realized if there is still one armed conflict in the world, but it may be satisfied to a significant extent when this is the only conflict there is, and few people are killed by it each year. While the argument will not depend on this, we will suppose that Si,t may sometimes take values in between 0 and 1.Footnote 8 We can thus write the total pro-attitude-satisfaction at a particular time as:

Total pro-attitude-satisfaction may be the structure wellbeing has for desire-satisfaction theories of wellbeing. We shall call this formula the Absolute Model of pro-attitude satisfaction. On this view, interpersonal comparisons are made as follows: a person P1 is better off than person P2 if P1’s total pro-attitude satisfaction is higher than P2’s.

While defenders of this broad category of subjective theories typically do not specify precisely the quantitative structure of their theories, we can find some textual evidence in favor of this aggregative strategy. Valerie Tiberius, for example, in her defense of Value Fulfillment theory, writes:

“For the value fulfillment theory, overall well-being consists in total value fulfillment: the ultimate goal is a life as rich in value fulfillment as it could be” (Tiberius 2018, 48; our emphasis)

And Chris Heathwood suggests the following procedure:

“The intrinsic value of a life for the one who lives it = the sum of the values of all the instances of subjective desire subjectively satisfaction [sic] and frustration contained therein” (Heathwood 2006a, 548; our emphasis)

As we shall see, there is also some rationale for this view. However, there is also some rationale for an alternative view, which we call the Relative Model. On this view, it is not the total satisfaction of pro-attitudes that determines how good a particular welfare state is compared to other states, but their relative value. On this view, a person’s degree of wellbeing is determined by the extent to which their pro-attitudes are satisfied, relative to the pro-attitudes that a person has.Footnote 9

On the Relative Model, the question is out of all pro-attitudes that one has, how much of the attitude set can be said to be satisfied? There is also some textual evidence for this view, from the fact that typically, pro-attitude-satisfaction theories are formulated as follows:

These models make a significant difference. In order to illustrate the difference, consider the following examples:

Bill: Bill is extremely affluent and has many pro-attitudes about things that he can buy: sport cars, massages, luxurious restaurant visits, etc. He develops new pro-attitudes fast, but is always able to satisfy them. We can say that, in a given period,Footnote 10 he has 50 strong pro-attitudes (Di=1), and all of them are satisfied (Si,t=1).

Eve: People often describe Eve as being “zen”. She always seems to have a calm mind. She has her daily routine, prepares all her food in a similar manner every day, sees her friends, and has a stable and tranquil life. She has few wants, but those she has are generally satisfied. We can say that, in a given period, she has 10 strong pro-attitudes (Di,t=1), and all of them are satisfied (Si,t=1).

Depending on whether we use the Absolute or the Relative Model, Bill will either come out as being five times better off as Eve, or both will come out has having a similar level of wellbeing.Footnote 11,Footnote 12

5 The Depressed and the Epicurean

5.1 The Absolute Model and the Epicurean Intuition

The Absolute Model has something to say for it. On this model, all pro-attitude satisfaction counts equally, independent of how many pro-attitudes a subject has. However, it is also easy to see why it is problematic. Consider the example of Bill and Eve above. It is one thing to say that Bill is better off than Eve because he has more satisfied pro-attitudes than she has. However, it is another to say that he is five times better off than Eve is. People with few pro-attitudes may be leading wonderful lives, if not better than those with many satisfied pro-attitudes. Eve’s life seems really good, even though she could hold many more pro-attitudes.

To enforce this point, consider a variation of Bill:

Will: Will is extremely affluent and has many pro-attitudes about things that he can buy: sport cars, massages, luxurious restaurant visits, etc. He develops new pro-attitudes very fast (even faster than Bill), is almost always able to satisfy them, but some remain unsatisfied. We can say that, in a given period, he has 60 strong pro-attitudes (Di,t=1), and 51 of them are fully satisfied (Si,t=1), the other 9 are unsatisfied (Si,t=0).

While Will has more pro-attitudes satisfied, and would come out as better off on the Absolute Model, it seems implausible that his degree of wellbeing is higher than Bill’s. The additional unsatisfied pro-attitudes seem to be, by themselves, a burden on Will’s wellbeing. And, transitioning from Will’s state to Bill’s state seems to be an improvement, as a result of eliminating unfulfilled pro-attitudes. In fact, the presence of unsatisfied pro-attitudes seems to outweigh his one additional satisfied pro-attitude.

If we merely count the number of satisfied pro-attitudes, we do not seem to do justice to the relative goodness of lives, to interpersonal comparisons in which people have vary in the total amount of pro-attitudes that they hold. In the original example, it already seemed implausible that Eve’s life was five times worse than Bill’s, but it is even more of stretch to say that Eve’s life is (even more than) five times worse than Will’s.

We believe that this judgment is rooted in a deeper idea about the value of desires, or pro-attitudes more generally. In Letter to Menoeceus, Epicurus argues that one should drop one’s desire for luxury food in favor of a simpler set of desires. Numerous philosophical schools have propagated the view that a reduction of desires, or other pro-attitudes, may directly contribute to a person’s wellbeing, even if these pro-attitudes can be satisfied at little cost. For example, the prudential strategy of an ascetic is to aim for a reduction of desires. An ascetic may aim to get rid of their worldly desires (desires for certain types of food, sex, etc.), in order to achieve a high level of wellbeing. But we do not need to endorse such an extreme strategy to see that unsatisfied pro-attitudes may be a burden on someone’s wellbeing. This intuition may explain why Eve is in a state of high wellbeing compared to Will, despite having fewer pro-attitudes that are satisfied. After all, while Will has significantly more pro-attitudes satisfied, Eve’s humble set of pro-attitudes leaves her with few wants.

What can we learn from this? Additional unsatisfied pro-attitudes are not neutral: they count negatively towards a person’s degree of wellbeing, and consequently, losing an unsatisfied pro-attitude may directly improve one’s life. We can call this the Epicurean Intuition.

Epicurean Intuition: A person may sometimes be directly benefitted by a reduction in unsatisfied pro-attitudes.

The Epicurean Intuition is not compatible with the Absolute Model. According to the Absolute Model, reducing one’s pro-attitudes is never a direct benefit (it may, of course, sometimes be an instrumental benefit).

There is a further problem with the Absolute Model, but before we get there, we need to consider the Relative Model.

5.2 The Relative Model and Depressions

The Relative Model is able to arrive at more plausible comparisons of wellbeing. On the Relative Model, Bill and Eve are equally well off, and Will is slightly worse off. This seems plausible. The Relative Model, however, faces its own challenge.

In order to see this, consider a second idea about degrees of wellbeing that subjectivism, and all theories of wellbeing, should be able to account for: depression is an archetypical case of ill-being, of having a low degree of wellbeing. Perhaps not all depressed are badly off in general, but, typically, depression is a state of ill-being. Moreover, all in all, depression disbenefits the person who suffers from it.

Depressions are diverse, but they also have common features. The DSM-5 prescribes nine criteria for identifying depressions, having five of them in two weeks is sufficient for the diagnosis. Three characteristics of depressions are worth describing here: First, depressions are often accompanied by negative affects – a depressed person typically experiences negative emotions towards the world, such as anxiety, stress, sadness, and despair. One of the DSM criteria is that one experiences bad moods throughout the day. Second, one has a low sense of self-worth and esteem. One of the DSM criteria is that one experiences “feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt nearly every day” (APA 2013, 125). Lastly, depressions are often accompanied by a loss of desire, appetite, and valuation about particular goods that one perhaps was motivated by previously, or about the world in general. One of the nine symptoms that the DSM uses to diagnose depressions is a “[m]arkedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day” (APA 2013, 125).

The challenge that depressions pose for the Relative Model stems from this latter element. A depressed person may lose their pro-attitudes in general – losing their interest in most, if not almost all, activities. Consider Mark, who is depressed, and just wants to sit on the couch all day and watch YouTube videos. This is, in fact, one of the few things Mark is able to do. So, the few pro-attitudes that he has left are easy to satisfy. In terms of pro-attitude-satisfaction, his life seems similar to Eve’s. Why then, is his depression so bad for him, whereas Eve seems to be, at the very least, moderately well off?

The Relative Model is able to account for the Epicurean Intuition through its denominator. It thereby accounts for the two-sidedness of pro-attitudes: satisfying them is good, but unsatisfied pro-attitudes may also reduce one’s wellbeing. For this very reason, however, it also runs into trouble if we look at depression. After all, the types of depression we have been concerned with limit one’s pro-attitudes, and on the Relative Model, limiting one’s unsatisfied pro-attitudes – by itself – has an upward effect on one’s degree of wellbeing.

We acknowledge that, quite plausibly, depression will have as a consequence that many pro-attitudes that a person does have are more difficult to achieve. However, because a person’s total set of pro-attitudes will typically be much reduced, it is not obvious that the relative level of satisfied pro-attitudes will overall be lower for depressed individuals compared to others. If that would be so, it is very well possible that depression, on this model, would improve lives, rather than make them worse. Mark’s pro-attitudes are limited to his positive attitude about sitting on the couch and watching YouTube videos. This pro-attitude is satisfied. Mark thus has very few pro-attitudes, but the ones that he does have, are satisfied. On the Relative Model, Mark is doing very well. However, this is an unpalatable conclusion.

Depression, prima facie, seems to be bad in virtue of the negative affect it induces on those who are depressed (Hawkins 2010). However, an account that makes wellbeing dependent upon the pro-attitudes a person has, does not negatively evaluate negative affect itself. It only does so if individuals have disvaluing attitudes towards it. We also acknowledge that many depressed individuals will value this negative affect negatively. But this is not necessary. Some depressed individuals may develop a tolerance towards this negative affect. Mark’s attitudes towards the world do not seem to fully account for the badness of his depression, especially if Mark stops judging this negative affect as bad.

We can summarize this intuition as follows:

Depression Intuition: Depression is wellbeing reducing, and the depressed are typically not very well off.

Because the depressed may have high levels of relative pro-attitude satisfaction, the Relative Model is unable to account for the Depression Intuition.

This in itself seems problematic, but the problem is worse. Ian Tully (2016) has recently argued that there are even forms of depression in which the depressed completely lose their appetite for the world. He builds on Viktor Frankl’s (1986) description of concentration camp prisoners who undergo their extremely harsh treatment in apathy.Footnote 13 He then argues:

“…these individuals no longer possess desires that can be frustrated, as is evidenced by their indifference not only to the demands placed upon them, but even to their bodily functions, to threats and to physical pain. If no desires are being frustrated, then the desire theory has no grounds for ascribing ill-being. But it is simply not plausible to suppose that those individuals Frankl observed in the Nazi camps were not in a terrible state.” (Tully 2016, 6)

If Tully is correct about the case, the following intuition needs to be met by theories of wellbeing:

Indifference Intuition: people without any pro-attitudes may be very badly off, and they may increase their degree of wellbeing

For Frankl’s prisoners, the Relative Model has mind-boggling consequences. As they hold no pro-attitudes at all, the denominator in the Relative Model is nil, and consequently, the wellbeing of these prisoners is either completely undefined, or infinite. The latter would be absurd. The wellbeing of the prisoners is terribly low, not infinitely high. And the former is absurd as well: their wellbeing is not non-existent. They still have levels of welfare, and they are very low. Exactly because this model counts the benefit of reducing one’s pro-attitudes, it runs into problems explaining the disbenefit of being in the type of depressed states we have been concerned with. Not having pro-attitudes, or having very few pro-attitudes, is not a benefit in these cases, but a harm. Frankl’s depressed prisoners do not value anything, but their life can be made better. Removing them from the camp, treating them, and caring for them, for starters, would benefit them.

The Indifference Intuition at the outset, may simply be incompatible with subjectivism (as Tully 2016 suggests). If so, this would be a bad outcome for subjectivism. After all, if Frankl is right, being depressed without having any pro-attitudes towards the world is not only a hypothetical counterexample to subjectivism, but a very real one. These individuals are not only conceptually possible, but have actually existed. If the Indifference Intuition is incompatible with subjectivism, subjectivism should be rejected. While we agree with Tully that the Indifference Intuition poses a significant challenge to subjectivism, the Absolute Model may be able to account for the Indifference Intuition. This brings us back to the Absolute Model.

5.3 The Absolute Model and the Disbenefit Constraint

The Absolute Model is much better at explaining the badness of the type of depression that we have discussed. The Absolute Model is able to account for the Depression Intuition. After all, depression reduces one’s pro-attitudes. Even if many of those pro-attitudes are satisfied, the total amount of satisfied pro-attitudes will still be low. Just like the Absolute Model counts Eve as having a low level of welfare, it would also count Mark as having a relatively low level of wellbeing. Depression disbenefits individuals, on this model, because they lose pro-attitudes that could, or would, have been satisfied if they were not depressed. And, consequently, depression causes one’s degree of wellbeing to decrease.

The Absolute Model may also account for Frankl cases and the Indifference Intuition. On this model, Frankl’s prisoners are doing poorly because they have no pro-attitudes that are satisfied, though they could be doing worse if they did hold contra-attitudes that were satisfied. These seem to be exactly the right type of conclusions.

However, the solution the Absolute Model offers also shows a problem with this model that goes back to the heart of subjectivism. This solution, using the Absolute Model, does not meet The (Disbenefit) Constraint. Recall that part of Indifference Intuition is that some things are good for individuals, even in the situation of Frankl’s prisoners. What would be good for one of Frankl’s prisoners on the Absolute Model is obtaining a set of pro-attitudes that can be satisfied. But, the Resonance Constraint maintains that something can only be good for individuals if they hold pro-attitudes towards them. The prisoners hold no pro-attitudes at all, so nothing could possibly be good for them.

Moreover, on this model, what explains the badness of the type of depression we have been concerned with is the lack of pro-attitudes that a depressed person can satisfy. In other words, what disbenefits her is that she is not attracted to value; she does not have pro-attitudes towards any goods in general. The Disbenefit Constraint states that in order to disbenefit from something, she has to care about it, either by disvaluing it, or by valuing the opposite. A depressed person may care about her lack of pro-attitudes towards life, satisfying the Disbenefit Constraint. However, this is not necessary for someone to disbenefit from a depression. On the Absolute Model, a person may be disbenefitted by losing a pro-attitude that is, or can (easily) be, satisfied, regardless of her attitudes towards these attitudes.

Again, take Mark. Say that he used to enjoy tennis, and was good at it, but has lost his appetite for it. Losing this appetite, on the Absolute Model, decreases his degree of wellbeing. After all, there used to be pro-attitudes that were satisfied, but now there are none. So, as decreasing one’s wellbeing constitutes a disbenefit, we can say that, on the Absolute Model, depression has disbenefitted Mark by causing him to lose his pro-attitude for tennis, which in turn decreased his welfare. But, Mark does not care for tennis, nor does he disvalue not playing tennis. So, by explaining the disbenefit of depressions in terms of a loss in satisfied pro-attitudes that one could have, but not yet has, the Absolute Model violates the Disbenefit Constraint.

Not all defenders of subjectivist theories of wellbeing are concerned about this problem. Tiberius, who seems to endorse the Absolute Model, writes:

“The value fulfillment theory says that something could be valuable for a person who doesn’t currently value that thing, because it could be that a certain value (for example, health or self-respect) is needed for that person to live a value-fulfilled life.” (2018, 62)

This reasoning may merely seem to suggest that certain pro-attitudes are instrumentally useful in achieving the satisfaction of pro-attitudes that one already has. But Tiberius also suggests that we can improve our lives by adopting pro-attitudes that may lead to value-fulfilment of pro-attitudes that we would otherwise not have had:

“For example, a person who values partying with hard drugs and lots of alcohol is not doing as well as they could if these values are going to cause an early death and the forfeiture of many other things they would come to value more.” (2018, 62).

Using a similar strategy, Tiberius could say about the depressed that a state of depression typically does not serve a person particularly well, and it can be improved by adopting pro-attitudes that a person does not yet have. On the Absolute Model, a depressed person such as Mark is not doing very well, and adopting a different set of pro-attitudes may lead to more absolute pro-attitude satisfaction. This would explain the harm of depression in a plausible way. This would, however, still violate the Disbenefit Constraint. It ascribes direct benefit to adopting certain pro-attitudes, even though currently someone holds no pro-attitudes towards these pro-attitudes. This is exactly what the Resonance Constraint is intended to avoid.

And indeed, Tiberius acknowledges that this aspect of her theory moves her theory towards objective theories. But, she also argues that ultimately, it still is a subjective theory:

The theory rejects the idea that certain things are good for people entirely independently of how they feel about them or could come to feel about them. In this respect (an important respect, I think) the value fulfillment theory is not an objective theory (2018, 63).

While we take no issue with this claim, we do take it as an acknowledgment of the idea that subjectivism can only account for the benefit of certain goods – e.g. the absence of depression or the lifestyle that Tiberius describes – by moving away from the Resonance Constraint.

To sum-up: subjectivism of the sort we are concerned with here faces a dilemma. It needs to account for degrees of wellbeing. We have introduced two ways to account for degrees of wellbeing on this model. But, both models face significant challenges. The Relative Model fails to account for the badness of depression and the Indifference Intuition. The Absolute Model, on the other hand, not only fails to account for the Epicurean Intuition, but can only account for the badness of depression and the Indifference Intuition in a way that is incompatible with the Resonance Constraint.

6 Objections

This conclusion is quite damaging for the subjectivist. What can the subjectivist reply?

A first objection is that the two models have so far been insufficiently motivated. Why are these two models the only ones considered? Is there no alternative model that can account for the badness of depression without the problems that we have discussed? It may seem, for instance, as if a hybrid model combining models 1 and 2 would be able to simultaneously capture the Epicurean Intuition and the badness of certain types of depression. One way to construct such a hybrid account is to multiply the result of model 1 by a factor α ∈ (0; 1), multiply the result of model 2 by a factor (1 − α), and add the results to each other. This would provide the following calculation for well-being:

We see multiple problems with this objection. For one, at least one of the two parts of this equation needs to be significantly rescaled, as the two are on two completely different scales. But, what’s more, while this model may appear to incorporate both intuitions, it also incorporates their problems. This is perhaps seen most clearly when we consider the way in which the value of α would have to be decided: Satisfying the Epicurean Intuition would tell in favor of making the value of α as high as possible. Satisfying the intuition that certain types of depression are bad, on the other hand, would tell in favor of making the value of α as low as possible.

The intuitions are fundamentally opposed. Accounting for the badness of depression in terms of short-fall of satisfied pro-attitudes, like the Absolute Model is able to do, will always fail to abide by the Disbenefit Constraint. If what is bad about depression is that it fails to achieve a sufficiently high number of satisfied pro-attitudes, it will always imply that what is bad about depression is that it does not provide something a person herself does not care about. And, any account that relativizes the value of pro-attitudes will allow for cases of depressed individuals who still have a relatively high number of satisfied pro-attitudes. This formula, at best, finds a balance between these problems, but it does not resolve them.

In a similar vein, someone may think that pro-attitudes neither count relatively or absolutely, but in some other way. As one anonymous referee suggested, preferences may count lexicographically. For instance, we may say that i is doing better than j if and only if (a) i satisfies more pro-attitudes than j and (b) if they satisfy the same number, j has more unsatisfied pro-attitudes than i.

Such a theory would be very similar to the absolute model, with the exception that in case of an equal amount of satisfied pro-attitudes the amount of unsatisfied pro-attitudes will determine the difference in wellbeing outcome.Footnote 14 Consequently, the problems with the model are the same as the problems with the absolute model. Eve does not have many satisfied pro-attitudes, but nevertheless appears to be doing well. Compare her with Steve:

Steve: Steve has a similar life to Eve, but is not quite as zen as she is. He wants to escape from this sober life, but is unable to. Some changes he has made in his life are already paying off, but he still has a long way to go. He has 11 satisfied pro-attitudes, but 20 unsatisfied ones.

It is clear where the lexicographical approach goes wrong. It only counts the unsatisfied pro-attitudes in case of a tie in satisfied pro-attitudes, but the unsatisfied pro-attitudes contribute to wellbeing, at least to some extent, in all cases.

There may of course still be alternative numerical structures subjective theories may take. But while formulating a plausible alternative structure may be the most promising way out of the argument that we have presented against subjective theories of wellbeing, it does appear to us that any plausible structure will either have to count pro-attitudes absolutely or relatively (or both), and thereby face the challenges that we have discussed at least to some significant extent.

Secondly, we have limited ourselves to unrestricted (monadic) subjective accounts of wellbeing. It may be suspected that this drives the substantive argument about the two models. For example, an anonymous referee of this journal suggested that on the Absolute Model, sophisticated theories of wellbeing may be able to account the Epicurean Intuition: if someone loses those pro-attitudes that would be disregarded on sophisticated theories, this may benefit someone. Consider a theory that excludes those pro-attitudes that are not endorsed by second-order pro-attitudes. This theory may conclude that losing those pro-attitudes that are not endorsed may improve total pro-attitude satisfaction by making more resources available to satisfy the pro-attitudes that are endorsed by second-order pro-attitudes.

We do not think this objection is promising. We believe that the examples that we have used to establish the intuitions, and the Epicurean Intuition in particular, work regardless of whether the described pro-attitudes are endorsed through second-order pro-attitudes or not. While we acknowledge that in some cases, the exclusion of unendorsed pro-attitudes may explain how these pro-attitudes may disbenefit someone on some sophisticated theories of wellbeing, if all the relevant pro-attitudes are endorsed by second-order pro-attitudes, this explanation would fail. It does not at all seem implausible that both Bill’s and Eve’s pro-attitudes are endorsed by their second-order pro-attitudes. And as long as that is the case, the problem for the absolute model remains. The same goes, we take it, for other types of idealizations.

Another version of this objection may target specifically the pro-attitudes of Mark. Someone may object by suggesting that the comparison between Mark and Eve fails on idealized accounts, because Eve’s pro-attitudes are more robust to idealizations than Mark’s. Perhaps Mark’s depression would not qualify as the type of ideal condition that sophisticated subjective theories require. And again, while depression is a mental illness, we do not think it is either a state of irrationality or misinformation, or that it would necessarily result in Mark not endorsing his first-order pro-attitudes for sitting on the couch and watching Youtube videos. Mark’s pro-attitudes towards sitting on the couch and watching Youtube video’s may thus pass all the typical tests sophisticated subjective accounts require. Moreover, even if Mark’s pro-attitudes would all be disqualified for this reason, it is not clear which pro-attitudes would determine his current wellbeing on such accounts. Some depressions lasts long, and may become part of one’s identity. There may very well not be an answer to the question which pro-attitudes a depressed person would have if they would not be depressed.

Third, the subjectivist may reply that the Resonance Constraint is only a constraint about intrinsic goods and bads, and by phrasing the Disbenefit Constraint more generally, in terms of disbenefit, it has become an unnecessarily strong a principle. Certain things that are merely instrumentally good or bad may decrease one’s degree of wellbeing. If that is so, a subjectivist may insist that depressions are not intrinsically bad, and consequently need not abide by the (Disbenefit) Constraint. Depressions are states in which one is prevented from satisfying many pro-attitudes, and are consequently instrumentally bad.

This reply is unattractive for two reasons. First, accounting for the badness of depression in instrumental terms does not do justice to direct negative impact on our wellbeing – it disbenefits us itself, not because of its instrumental impact on other goods. If a subjectivist can only account for the badness of depression in instrumental terms, it should still be seen as a significant failure of the account. Second, even if we narrow the meaning of the (Disbenefit) Constraint, the problem of accounting for the Epicurean Intuition remains. Only the Absolute Model could count individuals as Mark as having a low degree of wellbeing. But, the Absolute Model is implausible for independent reasons. There are at least some people, like Eve, who have very few satisfied pro-attitudes, but nevertheless live lives that are very high on wellbeing, higher than some who have more satisfied pro-attitudes, but also much more pro-attitudes in general. Narrowing the (disbenefit) constraint does not save the subjectivist. After all, the Absolute Model faces more problems than merely failing to satisfy the Disbenefit Constraint.

Fourth, we have not said much about the relationship between time and wellbeing. The subjectivist could respond that our focus on unspecified periods of time in which someone is depressed, and/or holds certain pro-attitudes that are or are not satisfied is too simplistic. In particular, the subjectivist might argue that the badness of depression is captured by the pro-attitudes a person has outside of the timeframe from which they are depressed.

To see how this could work, imagine Sarah, a very ambitious teenager. Sarah has plans to study biochemistry, start a family, and become the best lindy-hop dancer in the state of Georgia after she graduates from high school. After graduating, however, she gets severely depressed, requiring years of treatment. From the start of Sarah’s depression onwards, her pro-attitudes change: she no longer wants to study, start a family, and dance. The subjectivist could argue that the depression is still bad for Sarah, because pro-attitudes that she previously had about what would happen during the period in which is depressed are not satisfied.

We do not think this is a good response. The reason is that when it comes to the question when a person disbenefits from a pro-attitude frustration, the Disbenefit Constraint on subjectivism is time-sensitive: something can only be bad for an agent if she takes a disvaluing attitude towards it at the moment it disbenefits her (Dorsey 2013; see also Bruckner 2013). For Sarah, this would imply that her passive state – of not studying, starting a family, and dancing – would only be bad for her when she held those pro-attitudes, namely, before she was depressed. But, a depression is bad for someone when it is occurring. An account of wellbeing should be able to conclude that that a depression disbenefits someone at the moment, or in the time period, at which they are depressed.

There is a more fundamental concern with explaining the badness of depression by citing the pro-attitudes someone has in timeframes in which they are not depressed. Namely, there are some individuals, who, sadly, are depressed their whole lives. If we can only explain the badness of certain depressions by citing the pro-attitudes of periods outside of the depressed periods, this would have the implausible implication that a person who is depressed their whole life has a higher wellbeing than someone whose depression only affects part of their life.

Fifth, as an anonymous referee pointed out, we have focused our argument on cardinal interpersonal comparisons of wellbeing. It might be objected that our argument has not focused on intrapersonal comparisons of wellbeing, or on ordinal comparisons. We have, again, two responses to this objection. A first is that, as we explained in section III, the concept of wellbeing has numerous quantitative properties, and as substantive theories of wellbeing describe what wellbeing is, failing to account plausibly for one such property – e.g. interpersonal comparisons – constitutes a significant problem for such a theory. Secondly, our argument is easily extended to the intrapersonal case: Eve, Steve, Mark, Bill, and Will were now postulated to be different individuals. However, the argument would not change if they were the same individual at different timeframes. Moreover, the observations made on the basis of these cases – such as the observation that Eve is better off than Mark – is not made easier if we would only consider ordinal comparisons of wellbeing.

Finally, a subjectivist can always bite the bullet. Bill may be five times better off than Eve, and Will may be better off than Bill. If we would accept such claims, the Absolute Model may be salvaged. Or, depression may perhaps only be bad when the person who is experiencing the depression is disvaluing this depression, but not otherwise. This could salvage the Relative Model. Depressions that come with a loss of pro-attitudes for things to be different may not be bad for those that undergo them after all. We think that this response is implausible: Depressions are archetypical cases of ill-being, and disbenefit, and a theory of wellbeing that maintains that some depressions are not is too revisionist to be plausible. If subjectivism wants to bite the bullet on this – and deny that these types of depressions are bad for the individual – it should significantly raise the burden of proof for subjectivism.

But, this is not the only significant problem that subjectivism faces. In addition to the problem of accounting for the badness of depressions, numerous problems have been raised to subjectivist accounts of wellbeing. To name a few, subjectivist accounts face the problem of adaptation (Nussbaum 2009; Khader 2011; cf. Dorsey forthcoming; Bruckner 2009); the problem that it becomes paradoxical if people have a pro-attitude towards their life going badly (Bradley 2007, 2009); the problem that it is unable to account for the wellbeing of certain welfare subjects, such as small infants (Lin 2017; cf. Dorsey 2017b); and the problem that certain pro-attitudes seem irrelevant to wellbeing, for example, because they are too far removed from us (Sumner 1996, 2000; cf. Lukas 2009; Bruckner 2016). These problems cannot be treated separately, especially if it leads to bullet biting. The fact that the subjectivist account faces one type of problem raises the burden of proof when it comes to formulating an answer to other types of problems. The list of problems that raise the burden of proof for subjectivism is long. If that is correct, biting the bullet on this problem should be seen as a highly unattractive way forward.

7 Conclusion

In this article, we have defended and built on four different premises:

-

1)

Theories of wellbeing should be able to make sense of degrees of wellbeing: How do lives get relatively better and worse? How do benefits and harms compare to each other?

-

2)

Subjectivism is committed to the Resonance Constraint and the Disbenefit Constraint.

-

3)

Any theory of wellbeing should be able to make sense of the fact that depressions are bad – The Depression Intuition – and ascribe appropriate levels of wellbeing to those suffering from a complete lack of pro-attitudes – the Indifference Intuition.

-

4)

Theories of wellbeing should be able to account for the intrinsic benefit that may be achieved by reducing one’s unsatisfied pro-attitudes – the Epicurean Intuition.

We have put forward two models of how subjectivist theories of wellbeing can account for degrees of wellbeing. The Relative Model has attractive implications if it comes to the Epicurean Intuition, but falls short if it comes to explaining the badness of depression. The Absolute Model is able to explain the badness of depression, but fails to meet the Resonance Constraint and the Epicurean Intuition.

Subjectivist theories of wellbeing have many attractive features. However, subjectivism should be able to account for depressions as archetypical cases of ill-being. Similarly, it should account for the fact that even people with few wants can have wonderful lives. Doing so, we have argued, is a significant challenge to subjectivism.

Notes

According to operationalists about measurement, a quantity has no meaning unless there is a procedure by which we can arrive at this quantity (Bridgman 1927). For the purposes of this article, we suppose that this is false: even if there is no procedure by which we can arrive at reliable comparisons of wellbeing, we can still meaningfully say that some lives may be better or worse than others.

The precise quote in which Dorsey – who calls the Resonance Contraint the ‘deeply plausible thought’ – makes this claim is: “While the deeply plausible thought is not precisely theorized, I think it is no stretch to say that it captures the heart of subjectivism.” (2017a, 199, his emphasis)

Some have argued that the distinguishing feature of subjectivism is that according to subjectivism, our attitudes are at least sometimes sufficient for this good to contribute to wellbeing (see Van Weelden 2019 for a description of these two accounts). However, without the Resonance Constraint, this second description fails to describe the distinctive characteristic of subjective theories. Derek Parfit (1984, 498 appendix I) defined objective list theories as those theories according to which “certain things are good or bad for people, whether or not these people would want to have the good things, or to avoid the bad things”. The second criterion – the sometimes sufficiency criterion – is compatible with Parfit’s definition of objective list theories. The Resonance Constraint, on the other hand, is not. So, on pain of collapsing objective list theories and subjective theories, subjective theories need to abide by the Resonance Constraint.

This distinction between pro-attitudes and contra-attitudes may fail to make sense of preference-satisfaction theories of wellbeing, as there is no clear delineation between positive and negative pro-attitudes, but merely preference-rankings. In that case, the Resonance Constraint and the Disbenefit Constraint amount to saying that something cannot affect a person’s wellbeing if someone does not hold attitudes about that good, or is indifferent about that good.

Kagan (2015) is also concerned about the idea that failing to fulfil a desire is what is bad for someone on these subjective views of wellbeing. If that would be part of the view, events that leave someone indifferent, but fail to satisfy a desire (or other pro-attitude), would be bad for someone. The Disbenefit Constraints, however, draws a clear distinction from such events and events that do interfere with pro-attitudes, or realize contra-attitudes.

They are generally seen as representations of desires and beliefs, but for the present purpose, we can leave beliefs out of it.

To be clear, this is not to say that preferences cannot serve as an information basis for making intrapersonal comparisons of wellbeing well. In fact, on plausible interpretations of preferences and desire, intra-personal comparisons of preference-satisfaction and desire-satisfaction are identical. However, as we argued above, as wellbeing is a concept that is interpersonally comparable, if preference-satisfaction is the sole constituent of wellbeing, it should be interpersonally comparable in a plausible way. Furthermore, we are not denying that preferences may not constitute other valuable concepts, such as reasons (Dietrich and List 2013), or choice-prepensities (see Fumagalli 2013 for an overview of the many ways in which utilities can be understood.).

Because pro-attitudes are satisfied to certain degrees, we do not distinguish between frustrated pro-attitudes and unsatisfied pro-attitudes. We take the difference to be the following: unsatisfied pro-attitudes are pro-attitudes that are currently not satisfied. Frustrated pro-attitudes are pro-attitudes that are definitely not satisfied, and cannot be satisfied anymore. For instance, the desire that the sun shines at noon may be frustrated if it is cloudy and rainy at noon. However, the desire for world peace may be a general desire that is not tied to a particular timeframe. In that case, it may be currently unsatisfied, while there remains a possibility that it will change in the future.

The realization of contra-attitudes, on the Relative Model, counts negatively in the numerator, but having aversions increases the denominator. This way, contra-attitudes are treated similarly to pro-attitudes towards the opposite. If contra-attitudes would be subtracted in the denominator, the denominator would go towards zero if someone’s contra- and pro-attitudes are equally strong, which would push someone’s wellbeing upwards.

We do not intend for this qualification to limit the scope of our argument. This time period may very well be their whole life.

These vignettes fit better with the desire version of subjectivism than with alternatives. However, the vignettes can be changed such that they involve valuing attitudes or judgments, rather than desires, without this altering their role in the argument.

The usage of “five times better” relies on the ratio interpretation of pro-attitude satisfaction. However, even on a mere interval interpretation, we would be forced to say that Bill is much better off than Eve.

The quoted passage is as follows: “The day would come when [they] would simply lie on their bunks in the barracks, would refuse to rise for roll call or for assignment to a work squad, would not bother about mess call, and ceased going to the washroom. Once they had reached this state, neither reproaches nor threats could rouse them out of their apathy. Nothing frightened them any longer; punishments they accepted dully and indifferently, without seeming to feel them” (Frankl 1986, 117, quoted in Tully 2016).

And the fact that pro-attitudes are not weighted by their strength.

References

Alexandrova A (2017) Is well-being measurable after all? Public Health Ethics 10(2):129–137. https://doi.org/10.1093/phe/phw015

APA, American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub

Barrett J (2019) Interpersonal comparisons with preferences and desires. Politics Philos Econ 18(3):219–241

Bradley B (2007) A paradox for some theories of welfare. Philos Stud 133(1):45–53

Bradley B (2009) Well-Being and Death. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Bramble B (2013) The distinctive feeling theory of pleasure. Philos Stud 162(2):201–217

Bridgman PW (1927) The logic of modern physics, vol 3. Macmillan, New York

Bruckner DW (2009) In defense of adaptive preferences. Philos Stud 142(3):307–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-007-9188-7

Bruckner DW (2013) Present desire satisfaction and past well-being. Australas J Philos 91(1):15–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048402.2011.632016

Bruckner DW (2016) Quirky desires and well-being. J Ethics Soc Phil 10:1

Crisp R (2017) Well-being. In: Zalta EN (ed) The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2017 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/well-being/

Dietrich F, List C (2013) A reason-based theory of rational choice. Nous 47(1):104–134

Dorsey D (2012) Subjectivism without desire. Philos Rev 121(3):407–442. https://doi.org/10.1215/00318108-1574436

Dorsey D (2013) Desire-satisfaction and welfare as temporal. Ethical Theory Moral Pract 16(1):151–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-011-9315-6

Dorsey D (2017a) Idealization and the heart of subjectivism. Noûs 51(1):196–217

Dorsey D (2017b) Why should welfare ‘fit’? Philos Q 67(269):685–624

Dorsey D (forthcoming) Adaptive Preferences Are a Red Herring. J Am Philos Assoc

Feldman F (2002) The good life: a defense of attitudinal hedonism. Philos Phenomenol Res 65:604–628

Frankl VE (1986) The doctor and the soul: from psychotherapy to Logotherapy. Vintage

Fumagalli R (2013) The futile search for true Utility. Econ Philos 29(03):325–347

Greaves H, Lederman H (2017) Aggregating extended preferences. Philos Stud 174(5):1163–1190

Greaves H, Lederman H (2018) Extended preferences and interpersonal comparisons of well-being. Philos Phenomenol Res 96(3):636–667

Griffin J (1986) Well-being: its meaning, measurement, and moral importance. Oxford: Clarendon. http://philpapers.org/rec/griwim

Hausman DM (1995) The impossibility of interpersonal Utility comparisons. Mind 104(415):473–490

Hausman DM (2015) Valuing health: well-being, freedom, and suffering. New York: Oxford University Press. https://books.google.nl/books?hl=nl&lr=&id=nS1mBgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=hausman+valuing+health&ots=segQ06k0T4&sig=Bvf8N1_hgDYPNbyu8p33_vnstiI

Hawkins JS (2010) The subjective intuition. Philos Stud 148(1):61–68

Heathwood C (2006a) Desire Satisfactionism and hedonism. Philos Stud 128(3):539–563

Heathwood C (2006b) Desire Satisfactionism and hedonism. Philos Stud 128(3):539–563

Heathwood C (2014) Subjective Theories of Well-Being. In The Cambridge Companion to Utilitarianism., edited by Dale E. Miller and Ben Eggleston, 199–219. Cambridge University Press

Heathwood C (2015) Monism and pluralism about value. In The Oxford Handbook of Value Theory, edited by Iwao Hirose and Jonas Olsen, 136–157. New York: Oxford University Press

Kagan S (2015) An introduction to ill-being. Oxford Studies in Normative Ethics 4:261–288

Khader SJ (2011) Adaptive preferences and Women’s empowerment. OUP USA

Lin E (2016) How to use the experience machine. Utilitas 28(3):314–332. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0953820815000424

Lin E (2017) Against welfare subjectivism. Noûs 51(2):354–377

Lukas M (2009) Desire Satisfactionism and the problem of irrelevant desires. J Ethics Soc Phil 4:1–24

Nussbaum MC (2009) Frontiers of justice: disability, nationality. Harvard University Press, Species Membership

Parfit D (1984) Reasons and persons. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Raibley JR (2012) Welfare over time and the case for holism. Philos Pap 41(2):239–265

Railton P (1986) Facts and values. Philos Top 14:5–31

Rossi M (2011a) Degrees of preference and degrees of preference satisfaction. Utilitas 23(3):316–323

Rossi M (2011b) Transcendental arguments and interpersonal utility comparisons. Econ Philos 27(3):273–295. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266267111000216

Sen A (1980) Plural Utility. In Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 81:193–215. JSTOR

Smuts A (2011) The feels good theory of pleasure. Philos Stud 155(2):241–265

Sumner LW (1996) Welfare, happiness, and ethics. Clarendon Press

Sumner LW (2000) Something in between. Oxford University Press, New York

Tiberius V (2006) Well-being: psychological research for philosophers. Philos Compass 1(5):493–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-9991.2006.00038.x

Tiberius V (2018) Well-being as value fulfillment: how we can help each other to live well. Oxford University Press

Tully I (2016) Depression and the problem of absent desires. J Ethics Soc Phil 11:1

van der Deijl WJA (2017) Are measures of well-being philosophically adequate? Philos Soc Sci 47(3):209–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0048393116683249

van der Deijl WJA (2019) Is pleasure all that is good about experience? Philos Stud 176(7):1769–1787

Van Weelden J (2019) On two interpretations of the desire-satisfaction theory of Prudential value. Utilitas 31(2):137–156

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank audiences of Tilps research seminar in October 2019, and the OZSW conference in November 2019 for helpful comments. In particular we would like to thank Nathan Wildman, Bart Engelen, Christiaan Broekman, and the Rotterdam Axiology Group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Deijl, W., Brouwer, H. Can Subjectivism Account for Degrees of Wellbeing?. Ethic Theory Moral Prac 24, 767–788 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-021-10195-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-021-10195-3