Abstract

In this paper, we analyse a large, opportunistic dataset of responses (N = 219,826) to online, diagnostic multiple-choice mathematics questions, provided by 6–16-year-old UK school mathematics students (N = 7302). For each response, students were invited to indicate on a 5-point Likert-type scale how confident they were that their response was correct. Using demographic data available from the online platform, we examine the relationships between confidence and facility (the proportion of questions correct), as well as gender, age and socioeconomic disadvantage. We found a positive correlation between student confidence and mean facility, higher confidence for boys than for girls and lower confidence for students classified as socioeconomically disadvantaged, even after accounting for facility. We found that confidence was lower for older students, and this was particularly marked across the primary to secondary school transition. An important feature of the online platform used is that, when students answer a question incorrectly, they are presented with an analogous question about 3 weeks later. We exploited this feature to obtain the first evidence in an authentic school mathematics context for the hypercorrection effect (Butterfield & Metcalfe J EXP PSYCHOL 27:1491–1494, 2001), which is the observation that errors made with higher confidence are more likely to be corrected. These findings have implications for classroom practices that have the potential to support more effective and efficient learning of mathematics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The importance of school students’ confidence in their learning of mathematics has been increasingly recognised in recent years (e.g., Foster, 2016, 2021; Hannula, 2014). The mathematics education literature conceptualises students’ mathematics confidence within the affective domain (e.g., Code et al., 2016; Di Martino & Zan, 2010; Hannula et al., 2019; Kyriacou, 2005; Pepin & Roesken-Winter, 2014), where there is an abundance of similar and sometimes overlapping constructs relating to confidence (see Clarkson et al., 2017; Marsh et al., 2019). The focus for this study is on a fine-grained notion of confidence, corresponding to a student’s post hoc judgment on the probability that the answer that they have just given is correct (see Bandura, 1977; Foster, 2016, 2021; Stankov et al., 2012). However, we see this understanding of confidence as being situated within broader notions of “mathematics confidence” (Burton, 2004; Galbraith & Haines, 1998; Pierce & Stacey, 2004) that relate to positive feelings about mathematics in general and studying mathematics in particular (see Fennema & Sherman, 1976; Lim & Chapman, 2013).

Student confidence in mathematics is associated with higher attainment (Mullis et al., 2020), and, in an early meta-analysis of 113 primary studies, Ma and Kishor (1997) found evidence for a causal effect of attitude to mathematics on mathematics attainment. Since then, increasingly strong evidence has accumulated for a reciprocal, bidirectional relation between confidence and attainment (e.g., Ganley & Lubienski, 2016; Pinxten et al., 2014). Whether students feel confident about their learning of mathematics or not affects whether they find learning mathematics in school a happy or an unhappy experience (Foster, 2016; Hannula, 2014; Morsanyi et al., 2019), influences their success in this critical gatekeeping subject and predicts their future career choices (Franz-Odendaal et al., 2020; Paulsen & Betz, 2004).

In addition to the relationship with attainment, research has also found associations between students’ mathematics confidence and a variety of demographic variables, including gender, age and socioeconomic disadvantage. Students’ confidence is lower for girls, for older students and for students characterised as socioeconomically disadvantaged (e.g., Ganley & Lubienski, 2016; Mullis et al., 2020; OECD, 2013, 2019). However, the detailed relationships among these variables are not known, such as whether the relative under-confidence of girls varies with age or socioeconomic disadvantage, whether the decrease in student confidence with age can be fully accounted for by a decrease in attainment or whether the lower confidence of socioeconomically disadvantaged students can be fully accounted for by lower attainment. Understanding these relationships could give schools important insights into ways to support students’ learning of mathematics more effectively and equitably (see Foster, 2016, 2021).

The opportunistic dataset that forms the basis for this study derives from the Eedi online platform (eedi.co.uk), created by the second and third authors, which provides teachers with free access to over 50,000 multiple-choice diagnostic mathematics questions (e.g., see Fig. 1). As can be seen at the bottom of Fig. 1, a distinctive feature of the Eedi platform is its incorporation of a confidence assessment for every diagnostic question, with students invited to indicate after each response which of five confidence emojis (  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  or

or  ) best reflects their confidence level (Barton, 2020). Although confidence assessment instruments have been used frequently within the research literature, this feature is innovative from the point of view of assessment tools currently widely available to, and popular with, classroom teachers of mathematics. This study constitutes a response to calls for “the mathematics education research community to support companies to adopt more evidence-led approaches both in the design and evaluation of their products” (Clark-Wilson et al., 2020, p. 1237).

) best reflects their confidence level (Barton, 2020). Although confidence assessment instruments have been used frequently within the research literature, this feature is innovative from the point of view of assessment tools currently widely available to, and popular with, classroom teachers of mathematics. This study constitutes a response to calls for “the mathematics education research community to support companies to adopt more evidence-led approaches both in the design and evaluation of their products” (Clark-Wilson et al., 2020, p. 1237).

The platform is intended for use by teachers as a formative assessment tool (Barton, 2018a, b, 2020) and is currently used by students in over 5800 schools worldwide (over 4500 of which are in the UK). The Eedi platform is free to all teachers across the world and contains diagnostic questions designed for all ages from 5 to 16. While the site does include questions specifically tailored to the English national curriculum, the Eedi Ultimate Scheme of WorkFootnote 1 is designed to be suitable for use with any curriculum. There are more than 200 topics units, comprising more than 3000 questions that teachers can map to their curricula.

An Eedi Diagnostic Question is a multiple-choice question with one correct answer and three incorrect distractors. As usual with diagnostic questions, each distractor is carefully designed to provoke or reveal a different common error or misconception. A student responds by selecting one of four options (A, B, C or D), and an optional free-text box is available for the student’s explanation. For the example question shown in Fig. 1, the percentages of students responding to each of the options were as follows: A (17%), B (correct, 58%), C (19%) and D (6%). The diagnostic feature of this is that the two most common incorrect responses (A and C) may be taken to indicate very different kinds of student difficulties. Students responding with A might be experiencing confusion with negative numbers, whereas students responding with C might have confused “descending” with “ascending”. It is clear in this case that an appropriate teacher response could be quite different for these two groups of students: focusing teaching on directed numbers may be of no help at all to students who responded with C. The Eedi platform provides easy and cost-free access for teachers to a very large collection of such questions, which they can use formatively to enhance their classroom teaching. The dataset generated is large and suitable for research analysis.

Diagnostic Questions may be used to assess facts, procedures or concepts (see Fig. 2 for examples of each). Diagnostic Questions are particularly well suited to assessing recall of facts (Fig. 2a) or simple procedures (Fig. 2b). However, if carefully designed, they can also be used to assess performance on multi-step procedures, by isolating one stage in the procedure (Fig. 2c). This provides more helpful information for a teacher, as it reveals exactly where in a process a student has difficulty. Diagnostic Questions are designed with the intention that students spend no longer than 1 min considering their answer. If a fact- or procedure-based question takes longer to answer than this, then it is likely that the student is having to consider several sub-steps, which makes it difficult to capture the specific nature of their misunderstanding in the three distractors. Finally, Diagnostic Questions can also be used to assess conceptual understanding, as in the example shown in Fig. 2d. Here, students might spend longer considering their answer, potentially thinking about various examples and non-examples in order to reach their final decision.

Examples of diagnostic questions assessing (a) a fact (link to question: https://diagnosticquestions.com/Questions/Go#/93384); (b) a simple procedure (link to question: https://diagnosticquestions.com/Questions/Go#/107849); (c) a multi-step procedure (link to question: https://diagnosticquestions.com/Questions/Go#/106633); (d) a concept (link to question: https://diagnosticquestions.com/Questions/Go#/99575)

A further feature of the Eedi platform allows us to explore evidence for the hypercorrection effect, which is the observation that errors made with high confidence are more easily corrected than those made with low confidence (Butterfield & Metcalfe, 2001; see Barton, 2020). On the Eedi platform, teachers assign “quizzes”, each consisting of 5–20 Diagnostic Questions, and students complete these quizzes on the website or via the mobile app, either during school time or as part of home learning. Teachers may also assign their class a “scheme of work”, comprising a sequence of topic units, each of which includes two quizzes covering the same content, with the same level of difficulty. One is intended for use immediately after the topic has been taught (quiz A) and the other as a review quiz administered about 3 weeks later (quiz B). The questions in these two quizzes differ only in the numbers used and the order in which the responses are presented and are intended to test exactly the same constructs and reveal exactly the same misconceptions. Quiz B is intended to take advantage of spaced retrieval practice (Rohrer & Taylor, 2007) and to distinguish “learning” from “performance” (Soderstrom & Bjork, 2015) by revealing what knowledge has been retained and whether errors or misconceptions have remained or changed. For our purposes, the quiz A–quiz B structure also enables us to explore evidence for the hypercorrection effect in students’ responses on quiz B, administered 3 weeks after quiz A. We are not aware of any previous study examining the hypercorrection effect in school mathematics in authentic learning settings such as this.

Consequently, our research questions for this study, using the data obtained from the Eedi platform, are:

-

1.

How are students’ confidence ratings related to their mean facility, age, gender and socioeconomic disadvantage, and how do these variables interact?

-

2.

Is there evidence for the hypercorrection effect in students’ responses to a second set of questions (quiz B) administered 3 weeks after the first (quiz A)?

2 Confidence and learning mathematics

The affective domain in mathematics has been studied for at least 30 years, and the mathematics education literature conceives of students’ mathematical confidence as a component of the affective domain (see Code et al., 2016; Di Martino & Zan, 2010; Hannula et al., 2019; Kyriacou, 2005; Pepin & Roesken-Winter, 2014). Within this literature, there are multiple similar and overlapping confidence-related constructs, ranging in scope from broad to narrow (see Clarkson et al., 2017; Marsh et al., 2019). At the broad end, there are subject-level notions of “mathematics confidence” (e.g., Burton, 2004; Pierce & Stacey, 2004), such as Galbraith & Haines’s (1998, p. 278) definition that mathematically confident students “believe they obtain value for effort, do not worry about learning hard topics, expect to get good results, and feel good about mathematics as a subject”. Such constructs have often been measured using variations on the Confidence in Learning Mathematics Scale within the Fennema-Sherman Mathematics Attitudes Scales (Fennema & Sherman, 1976; Lim & Chapman, 2013). At the finer-grained level, more focused on specific tasks or items, are constructs such as mathematical self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977), which is a student’s belief about their chances of successfully performing a future mathematical task, and confidence of response, a student’s post hoc judgment on the probability that the answer that they have just given is correct (Foster, 2016, 2021; Stankov et al., 2012).

Previous research has identified associations between confidence and a variety of important demographic characteristics, which we attempt to replicate and build on in this study. In particular, the hypercorrection effect (Butterfield & Metcalfe, 2001), which is the observation that errors made with high confidence are more likely to be corrected than those made with low confidence, has been repeatedly demonstrated in laboratory settings (e.g., Butler et al., 2011; Metcalfe & Finn, 2011, 2012), but this study will be the first attempt to replicate it in an authentic mathematics learning situation.

2.1 Associations between confidence and facility, gender, socioeconomic disadvantage and age

The 2019 Trends in Maths and Science Study (TIMSS) found that for students in both years 5 and 9 (ages 9–10 and 13–14 respectively), there was a strong positive association between their confidence in their mathematical ability and their average attainment (Mullis et al., 2020). Quantitative studies have revealed the most likely model to be a reciprocal, bidirectional relation between confidence and attainment (Ganley & Lubienski, 2016; Ma & Kishor, 1997; Pinxten et al., 2014). Fischhoff et al. (1977, p. 552) defined a student as being well calibrated “if, over the long run, for all propositions assigned a given probability, the proportion that is true is equal to the probability assigned”; in other words, students accurately estimate the probability that their responses will be correct. Students have often been found to be well calibrated, and Foster (2016) previously reported a correlation of r = .546 between facility and mean confidence for 345 students aged 11–14 in the topic of directed numbers. However, children also often overestimate their performance, believing that this will lead others to view them more favourably (see Panaoura et al., 2009). Several additional factors are also known to be related to students’ confidence in mathematics, and principal among these are gender, socioeconomic disadvantage and age.

Research has repeatedly found that girls show lower confidence in mathematics than boys do (e.g., Frost et al., 1994; Ganley & Lubienski, 2016; Mullis et al., 2020), even when girls obtain higher mathematics grades than boys (Pomerantz et al., 2002). The 2019 TIMSS found that in England more 13–14-year-old boys than girls (18% compared to 10%) expressed being “very confident”, and more girls than boys (44% compared to 30%) expressed being “not confident” (Mullis et al., 2020). Similarly, the 2012 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) international comparative study found that, among 15-year-old students, more girls (35%) than boys (25%) reported feeling helpless when doing mathematics problems (OECD, 2013), and it seems likely that societal stereotypes about gendered roles contribute to girls’ lower confidence in mathematics (Mendick & Francis, 2012). More recent PISA studies have not asked students to judge their capabilities in particular subjects, such as mathematics, and instead have asked students to report on “their general sense of efficacy, or competence, particularly in the face of adversity” (OECD, 2019, p. 190). PISA 2018 found that, in almost every country, girls expressed greater fear of failure than boys did, and this gender gap was much wider among higher-achieving students. Despite a considerable body of research, it is not known to what extent the relative under-confidence of girls relates to other variables, such as age and socioeconomic disadvantage, and these are questions we will address in this study.

The same 2012 PISA study (OECD, 2013) also found that more socioeconomically disadvantaged students (35%) than advantaged students (24%) reported feeling helpless when doing mathematics problems, and the most recent 2018 PISA study found that, in almost every country, socioeconomically disadvantaged students reported lower general self-confidence than their more advantaged peers (OECD, 2019). Whether this lower confidence among socioeconomically disadvantaged students is simply related to lower attainment, or is more than would be predicted purely on the basis of attainment, is not known, and one of the aims of this study is to explore this.

Finally, students’ confidence in mathematics is known to reduce as they get older and progress through schooling (Galton et al., 2003; Greany et al., 2016; Zanobini & Usai, 2002). This may be a consequence of the mathematics that they are learning becoming perceived as increasingly abstract and difficult, leading to greater disaffection and a reduction in confidence. It may also be related to students’ developing metacognition and self-representation, as they become more conscious of any difficulties and limitations. The 2019 TIMSS study (Mullis et al., 2020) found that student confidence declined with age from primary to secondary school, with the proportion of students reporting themselves to be “very confident” or “somewhat confident” in mathematics decreasing from 76% in year 5 (age 9–10) to 63% in year 9 (age 13–14) (Mullis et al., 2020). Once again, it is not known the extent to which this decrease in confidence can be accounted for purely as a result of a decrease in success with mathematics, or whether additional factors are involved, and our analysis will also address that question.

2.2 The hypercorrection effect

A further focus of the present study is the hypercorrection effect, which is the observation that errors made with high confidence are more likely to be corrected than those made with low confidence (Butterfield & Metcalfe, 2001). The effect has been repeatedly demonstrated in laboratory settings, usually involving college students being tested on general-knowledge questions, but has also been found in young children (Metcalfe & Finn, 2012). The hypercorrection effect has been reported in studies using educationally relevant material in science (van Loon et al., 2015) and in an authentic classroom context with college students studying horticulture (Carpenter et al., 2018). However, we are not aware of any studies examining the hypercorrection effect in mathematics, or in authentic school settings as part of educationally relevant assessment, and exploring this, with a large dataset, is one of the main aims of this study.

The hypercorrection effect is surprising on theoretical grounds: it seems plausible that errors made with high confidence should be more difficult to correct, since we would expect them to be more deeply entrenched (Butterfield & Metcalfe, 2006). One possible mechanism for hypercorrection is that the surprise experienced when a person finds that their high confidence response is wrong heightens their attentional resources and so enhances memory (Butterfield & Metcalfe, 2006). Alternatively, it may be that high confidence errors might act as mediators to the correct response, by associating the correct response with the error (the semantic mediation hypothesis, see Metcalfe & Huelser, 2020). Finally, it may be that high confidence over an error suggests that it lies in a richly developed semantic landscape, where familiarity with the domain makes it more likely that the correct information is stored in semantic memory, even if not strongly enough to be given as the initial response (Butterfield & Metcalfe, 2006). Study participants are more likely to claim that they “knew it all along” when they are corrected after making an error with high confidence than when making a less confident error (Metcalfe & Finn, 2011). More recently, it has been suggested that error correction is mainly related to prior knowledge, and that confidence is primarily a proxy for prior knowledge (Sitzman et al., 2020).

Hypercorrection effects have been found to be persistent over time (Butler et al., 2011) and appear to offer the potential to improve learning in the classroom (Barton, 2020; de Bruin & van Gog, 2012; Efklides, 2012). Trying to avoid students making errors may be a counterproductive goal for the teacher, and it may be preferable to allow and even encourage students to make mistakes in low-stakes assessments. This may be especially valuable if, when these errors are made with high confidence, they are likely to be hypercorrected (Metcalfe, 2017). Consequently, the possibility of attempting to harness the hypercorrection effect for practical use in the mathematics classroom has recently been proposed (Barton, 2018a, 2020). However, it is not known to what extent the hypercorrection effect operates in authentic learning situations in mathematics, and testing this is an important aim of this study.

3 Method

3.1 Participants

Data were collected from students who used the Eedi online platform (eedi.co.uk)Footnote 2 between 7 March 2019 and 9 May 2020. A total of 327,737 students accessed the platform during this period, from a total of 3083 schools. This study draws its findings from a sample of UK students who were assigned two quizzes on the same topic, 3 weeks apart, completed the second quiz no later than 4 weeks after the first, answered at least one question from the first quiz and gave a measure of confidence. In between the two quizzes, students would typically work on different topics from those addressed in the quizzes.

We focused on UK students because these were the ones for whom we had access to additional metadata of gender, age and social disadvantage (Free School MealsFootnote 3 and Pupil PremiumFootnote 4 statuses). We excluded students who answered fewer than 5 questions in total, and we excluded answers which were more than a week late. This resulted in a dataset consisting of N = 7302 students from 152 schools, with a total of 219,826 responses (M = 30.1 responses per student, SD = 42.7). For 119,211 of these responses, there was a corresponding answer in quiz B, and these were from 4123 unique users.

For these students, demographic data revealed that 3586 were female (49.1%) and 1541 students (21.1%) were disadvantaged, as measured by eligibility for either Free School Meals (Gorard, 2012) or Pupil Premium (Gov.UK, 2020a) (see Table 1 for the breakdown of the sample by gender, disadvantage and age). Currently, across England, 17.3% of pupils are known to be eligible for Free School Meals (Gov.UK, 2020b), so, on this measure, our sample is slightly more disadvantaged than the national average.

For the analysis by age, we restricted the dataset to responses given between September 2019 and May 2020 (within one academic year), so that each student’s answers fell within a single academic year, allowing us to classify each student within a single year. This gave us a dataset consisting of N = 5382 students from 92 schools, with a total of 168,922 responses (see Table 1).

3.2 Instrument

Although the diagnostic questions on the Eedi platform are not formally trialled or calibrated with students before use in order to ascertain that the reasons for the students’ incorrect responses align precisely with those intended by the question writers, the students did have the opportunity to respond in a free-text box with a reason for their answers. Examination of these responses suggests that there is generally a very strong alignment between the students’ reasoning and the question writers’ intentions behind the distractors, which are founded on their extensive practice-based knowledge and experience. We are confident of the validity of these questions, since they have been very widely used in thousands of schools, and Eedi applies a robust quality-control process of internal peer review on all questions submitted.

As described above, if students choose to express how confident they are about their answer (A, B, C or D), then they select from one of 5 emojis, from sad to happy. Using emoji scales with children can lead to more reliable data, since the faces may be easier for children to interpret than words or numbers (see Kaye et al., 2017; Massey, 2021). We coded the five confidence emojis as 0  , 25

, 25  , 50

, 50  , 75

, 75  and 100

and 100  , so that their mean values could be directly compared with mean percentage facilities (percentage of questions answered correctly) for each student, assuming a linear scale of confidence.

, so that their mean values could be directly compared with mean percentage facilities (percentage of questions answered correctly) for each student, assuming a linear scale of confidence.

As explained above, our data for investigating the hypercorrection effect derived from students who answered both quiz A and quiz B. For this analysis, it is important that each pair of analogous questions should be of equal difficulty, and in the Appendix, we provide evidence that this is the case. Although the questions we analysed are grouped into quizzes, in this analysis, we make the assumption that the hypercorrection effect can be measured between paired questions, without considering the overall quiz performance.

3.3 Ethics

By using the Eedi website, all participants consented for their anonymised data to be used in this analysis. This paper uses personal data collected by Eedi under the lawful basis of legitimate interests (GDPR Art. 6 (1) (f)). The privacy notices provided to participants using the Eedi service explain that their data will be further analysed, under the same lawful basis, for research purposes, and that any results published will only include aggregated statistics. The dataset publicly available on GitHub contains only anonymised data. Because this study involved analysing only anonymous pre-existing data, and because all participants had consented for their data to be used for research purposes, no institutional ethical approval was required.

3.4 Overview of the analytic approach

We used a range of quantitative methods to address the two research questions, including linear and logistic regression, non-parametric tests and mediation analysis. Mediation analysis is a method for revealing whether the effect of one variable on another is direct or is transmitted partially or fully via a third variable.

For our first research question (How are students’ confidence ratings related to their mean facility, age, gender and socioeconomic disadvantage, and how do these variables interact?), we fitted two linear regression models for Confidence, both using all four predictors (Facility, Age, Gender, Advantaged), but the first with no interaction terms, and the second including all of the 2-way interactions. The results suggested that Advantaged may be partially mediated through the other predictors, and so we conducted a post hoc mediation analysis to investigate whether the effect of Advantage on Confidence operates via Facility, which was by far the strongest predictor. We also conducted a post hoc mediation analysis to see whether the effect of Age on Confidence also might be mediated by Facility.

We also conducted some additional analyses to help understand the nature of students’ calibration (the correlation between Facility and Confidence). We did this both (i) by student and (ii) by question.

For (i), we calculated the Pearson correlation between each student’s mean confidence on the questions on which they were correct and their mean confidence on the questions on which they were incorrect. We also used a Wilcoxon signed-rank test to determine whether there was a difference between students’ confidence levels on questions on which they were correct and those on which they were incorrect, and a Kruskal-Wallis test to determine whether the number of correct attempts differed by confidence level. Non-parametric tests were used in both cases, because the conditions for parametric tests, such as normality, were not satisfied (see Baguley, 2012).

For (ii), we carried out a similar Pearson correlation analysis, followed by a Mann-Whitney U test to determine whether the standard deviation of the confidence was greater for questions than for students. We also used Mann-Whitney U tests to determine whether there was a difference between boys and girls in the number of questions answered or in the number of questions answered correctly, and to determine whether disadvantaged students answered fewer questions than advantaged students, answered fewer questions correctly or had lower mean confidence. Again, non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests were appropriate here, because the conditions for parametric tests, such as normality, were not satisfied (see Baguley, 2012).

To address our second research question (Is there evidence for the hypercorrection effect in students’ responses to a second set of questions (quiz B) administered 3 weeks after the first (quiz A)?), we needed to account for the fact that higher confidence on quiz A could be a proxy for higher “ability” and therefore would be likely to correlate with higher success on quiz B even without a hypercorrection effect. So, in order to partial out facility on quiz A, we carried out a logistic regression–logistic this time, since the outcome variable (facility on quiz B) was dichotomous. We included all 5 predictors in the model, as a conservative strategy to avoid making unjustified assumptions about the character of the best-fitting model.

All data analysis was carried out using Python, with the statsmodels package (Seabold & Perktold, 2010), and all Python code is provided at https://github.com/Eedi/diagnostic-questions-and-student-confidence.

4 Results

We now report our findings under each of the two research questions set out above.

4.1 How are students’ confidence ratings related to their mean facility, age, gender and socioeconomic disadvantage, and how do these variables interact?

The correlation matrix given in Table 2 shows that there was a positive association between the mean facility (the proportion of questions correct) for each student, and their mean confidence (rs = .504, p < .001). In general, confidence was higher for boys (rs = .134, with female coded 0 and male coded 1) and for more socioeconomically advantaged students (rs = .094, with socioeconomically disadvantaged coded 0 and socioeconomically advantaged coded 1) but decreased with age (rs = −.140). Facility was higher for advantaged students (rs = .141) and decreased a little with age (rs = −.053, all ps < .001). The small p values in Table 2 for all of the correlations just mentioned, even those correlations that are small in absolute size, mean that the correlations are statistically significantly different from zero.

We fitted two linear regression models, with standardisedFootnote 5 mean confidence as the dependent variable, and, among the predictors, we standardised Facility and Age, but not the two binary categorical predictors, Gender and Advantaged. The first model contained just the four predictors (Table 3); the second model included all of the 2-way interactions (Table 4).

The regression coefficients for Facility and Age in this multiple regression model (Table 3) are consistent with the correlation matrix (Table 2). For Gender and Advantaged, it is not possible to directly compare the βs in Table 3 with the rs values in Table 2, since those variables were not standardised. However, by running models with single predictors of Confidence, we calculated that the regression coefficients for Gender and Advantaged (in separate single-predictor models) were 0.257 [95% CI = 0.212 to 0.303] and 0.245 [95% CI = 0.189 to 0.301]. Comparing these with the values in Table 3, we can see that the regression coefficient for Gender is very similar, but the coefficient for Advantaged has decreased considerably (0.245 to 0.081), suggesting that Advantaged may be partially mediated through the other predictors. Below, we conduct a post hoc mediation analysis to investigate this.

It is clear that Facility is the dominant predictor, so it is important to consider the possible interaction of other predictors with Facility. Table 4 shows results from the multiple regression model which includes all 2-way interactions. Including the interaction terms does not appreciably affect the regression coefficients for Facility, Age and Gender, but, again, the coefficient for Advantaged has now dropped a little further, from 0.081 to 0.056, also now becoming nonsignificant. This suggests that the effects of Advantaged are now fully mediated through some or all of the other predictors. The only significant 2-way interaction is between Facility and Gender, and the regression coefficient for this is small (−0.052).

We now present more detailed analysis relating to each predictor.

4.1.1 Facility

Facility was by far the strongest predictor of Confidence (β = 0.522, p < .001), and the positive association between mean facility and mean confidence for each student was rs = .504 (p < .001). This is close to Foster’s (2016) previously reported correlation of r = .546 between facility and mean confidence for 11–14-year-old students in the topic of directed numbers (N = 345), meaning students’ level of calibration (see Fischhoff et al., 1977, p. 552) in the current study is comparable to this. However, it is clear from Fig. 3 and Table 5 that there are students at every combination of facility and confidence.

To explore students’ calibration in more detail, we calculated each student’s mean confidence on the questions on which they were correct and their mean confidence on the questions on which they were incorrect (see scatterplot in Fig. 4a). To guard against extreme responses, in this analysis we only included students who had provided at least 50 answers, at least 5 of which were correct, and at least 5 of which were incorrect, giving a dataset of 115,437 answers from 1033 students. The fact that most of the points are above the diagonal line in Fig. 4a shows that students tended to show greater confidence on correct questions than on incorrect questions, but the strong positive correlation (rs(1031) = .889, p < .001) indicates that students who gave higher confidence scores tended to do so both for questions on which they were correct and for those on which they were incorrect. The histogram of differences in mean confidence score (Fig. 4b) is positively skewed, with a bulge near zero, indicating a large number of students who gave the same confidence level, whether or not their answer was correct. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated that, on average, students were more confident with questions on which they were correct (Mdn = 82.8) than with those on which they were incorrect (Mdn = 68.8, Z = 11,255, rs = .956, p < .001). The percentage of correct answers increased markedly with confidence (Table 5). A Kruskal-Wallis test found a difference in the number of correct attempts by answers with different confidence (H(4) = 20,487.1, p < .001).

Students’ mean confidence on questions that they answered correctly versus their mean confidence on questions that they answered incorrectly. In a scatterplot (a), each disc represents one student, and the size of the disc represents the number of questions the student answered. The differences are plotted as a histogram in (b). These plots are for students who each answered more than 50 questions, at least 5 of which were correct and 5 were incorrect (N = 1033)

A similar analysis but by question (Fig. 5) showed a positive but weaker correlation (rs(1,137) = .477, p < .001). Similar to before, for this analysis, we only included questions with at least 50 answers, at least 5 of which were correct and at least 5 of which were incorrect, giving 110,283 responses across 1139 questions. For each student and each question, we calculated the standard deviation of the confidence. A Mann-Whitney U test indicated that the standard deviation of the confidence was greater for questions (Mdn = 30.8) than for students (Mdn = 22.2, U = 284,839.5, p < .001). This indicated that the confidence rating given was more strongly associated with the student than with the question.

Scatterplot of each question’s mean confidence from students who were correct against the mean confidence from students who were incorrect. In a scatterplot (a), each disc represents one question, and the size of the disc represents the number of students who answered the question. The differences are plotted as a histogram in (b). Note that these plots are for questions with more than 50 answers, at least 5 of which were correct and 5 were incorrect (N = 1139). The number of answers to the questions ranged from 51 to 320 (M = 96.8, SD = 55.3)

4.1.2 Age

The correlation matrix given in Table 2 shows that mean confidence decreased with student age (rs = −.140, p < .001), and facility also decreased a little with age (rs = −.053, p < .001). To explore this further, we restricted the dataset to responses during one academic year: between September 2019 and May 2020 (N = 5382). We did this so that each student could be assigned to a single school year. We grouped the students into bands according to their school year: key stage 2 (ages 7–11), key stage 3 (ages 11–14) and key stage 4 (ages 14–16). Kruskal-Wallis tests comparing the parameter distributions between the groups found statistically significant differences among the key stages for the number of questions answered, the mean facility and also the mean confidence (see Table 6). For almost all facility levels, there is a clear decrease in confidence as age increases, and the drop in confidence from key stage 2 to key stage 3 appears to be generally larger than the drop from key stage 3 to key stage 4 (see Fig. 6).

Confidence against facility by key stage, with facility split into decades. The grouped histogram shows the distribution of students by key stage in the different facility decades. Above each group, we have added the results of a Mann-Whitney U test, two-sided with Bonferroni correction, for the key stage 2 and 4 groups. ns: .05 < p; *.01 < p ≤ .05; **.001 < p ≤ .01; ***.0001 < p ≤ .001

To investigate the possibility that the decrease in confidence with increasing age might be mediated by the difficulty of the mathematics, we conducted a post hoc mediation analysis using the statsmodels mediation package in Python (Seabold & Perktold, 2010) to compute 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) over 1000 simulations to test for significant indirect effects (Fig. 7). Age displayed a significant direct effect on Confidence (β = −0.117, 95% CI = −0.136 to −0.097, p < .001) and a significant indirect effect on Confidence, with Facility as mediator (β = −0.027, 95% CI = −0.046 to −0.008, p = .008). Age was associated with Confidence, but only 18.7% (95% CI = 6.2% to 29.4%, p = .008) of this relationship was mediated by decreased Facility.

Model to investigate mediation of the effect of age by facility. Note that for clarity in this figure, we did not include the predictors Advantage and Gender, but these were included in all of the statistical analyses. *** p < .001. This analysis was for the restricted dataset (September 2019–May 2020, N = 5382)

4.1.3 Gender

Table 7 indicates that mean confidence was higher for boys than for girls (rs = .134, p < .001) and, when analysed by decade of facility (see Fig. 8), the same pattern is striking across all levels of facility. Mann-Whitney U tests found no significant difference between boys and girls on the number of questions answered or on the number of questions answered correctly (Table 7), suggesting that boys’ higher confidence constitutes overconfidence. We found a significant interaction between Facility and Gender (β = −0.052, p = .011), meaning that confidence increases more slowly with Facility for boys than it does for girls. This means that the overconfidence of boys is more marked with lower-attaining students.

Confidence against facility by disadvantage, with facility split into decades. The paired histogram shows the distribution of students by disadvantage in the different facility decades. Above each group, we have added the results of a Mann-Whitney U test two-sided with Bonferroni correction. ns: .05 < p, *.01 < p ≤. 05, ** .001 < p ≤ .01, *** .0001 < p ≤ .001

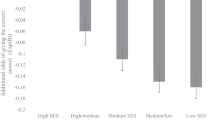

4.1.4 Advantage

As noted before, both Confidence and Facility were higher for more socioeconomically advantaged students (rs = .094 and rs = .141, respectively, both ps < .001). When we included all 2-way interactions in our multiple regression model, the coefficient for Advantaged became nonsignificant, suggesting that the effects of Advantaged were fully mediated through some or all of the other predictors. To investigate this, we again conducted a post hoc mediation analysis using the statsmodels mediation package in Python (Seabold & Perktold, 2010), this time on the full dataset (N = 7302), to compute 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) over 1000 simulations (Fig. 9). Advantage displayed a significant direct effect on Confidence (β = 0.082, 95% CI = 0.030 to 0.128, p < .001) and a significant indirect effect on Confidence with Facility as mediator (β = 0.166, 95% CI = 0.136 to 0.197, p < .001). Advantage was associated with Confidence, and 67.0% (95% CI = 55.0% to 84.4%, p < .001) of this relationship was mediated by increased Facility.

Figure 8 presents the distribution of students (advantaged and disadvantaged) by decade of facility, showing a peak for the disadvantaged students in the 40–50 facility interval, whereas for the advantaged students, the peak is in the 60–70 facility interval. Two-sided Mann-Whitney U tests found that disadvantaged students answered fewer questions than advantaged students (rs = −.086, p < .001), answered fewer questions correctly (rs = −.199, p < .001), and the mean confidence for disadvantaged students was significantly lower than for advantaged students (rs = −.133, p < .001) (Table 8). For most (but not all) decades of facility, confidence was lower for disadvantaged students (see Fig. 8).

4.2 Is there evidence for the hypercorrection effect in students’ responses to a second set of questions (quiz B) administered 3 weeks after the first (quiz A)?

The hypercorrection effect (Butterfield & Metcalfe, 2001) predicts that a student who answers a question incorrectly but with high confidence will be more likely to be successful with the same or a similar question subsequently. To test this in our data, we analysed the 86,144 answers from a total of N = 7002 students within quiz A sessions where the answer was incorrect, a confidence rating was given and an analogous question was subsequently assigned 3 weeks later in quiz B (see Section 3.1). Table 9 and Fig. 10 show that the percentage of students making second attempts increased with the confidence level expressed on the first attempt.Footnote 6 We see a clear increase in facility with confidence, which might seem to demonstrate the hypercorrection effect: the students who were more confident about their original incorrect answer were more likely to answer correctly 3 weeks later in quiz B. However, it is important to distinguish hypercorrection from regression to the mean (Baguley, 2012), where facility is a confounder. Students expressing high confidence in quiz A, despite being incorrect on that occasion, are likely on average to be higher-facility students, since facility and confidence are correlated. Consequently, even without a hypercorrection effect, they would be expected to be more likely to succeed on quiz B anyway. This means that, in order to tease out any hypercorrection effect of confidence over and above an “ability effect”, we need to carry out a logistic regression.

Students attempting a similar question 3 weeks later (quiz B), following an incorrect answer, and the proportion of these which were correct. Dashed lines indicate the percentages for students who provided no measure of confidence. These plots are for pairs for which the first answer was incorrect; this reduced the dataset to 7002 students and 86,144 answer pairs

The data consisted of 44,524 incorrect answers by 3838 students who had attempted analogous questions 3 weeks later in quiz B (see Table 10). Of these students, 19,885 (44.7%) answered the quiz B question correctly and 24,639 (55.3%) incorrectly. The hypercorrection hypothesis is that the probability that the quiz B question is answered correctly is higher when the student’s confidence in their original mistake was higher, after controlling for facility.

In order to make as few modelling assumptions as possible, we fitted a five-predictor logistic model, using the Logit method in the statsmodels package, version 0.10.1 (Seabold & Perktold, 2010), so as to allow effects of any of these predictors to be accounted for. The model may be expressed as:

where the outcome variable Y is whether the quiz B question was answered correctly (0 = incorrect, 1 = correct), X1 is the mean student facility on quiz A (0–100), X2 is the student’s confidence in their original incorrect response on quiz A (0–100), X3 is the student’s age (6–16), X4 indicates whether the student was advantaged (0 = disadvantaged, 1 = advantaged) and X5 is the student’s gender (0 = female, 1 = male).

The result was:

According to the model (see Table 11), the log odds of a student answering correctly was, as expected, positively related to their overall facility (p < .001). However, and confirming our hypercorrection hypothesis, it was also positively related to their confidence in their quiz A mistake (p < .001). The log odds of a student answering correctly was negatively related to their age (p < .001) and to gender (p = .019). Whether they were advantaged was not statistically significant (p = .105).

In other words, the higher the student’s confidence in their quiz A mistake, the more likely it was that the student answered the quiz B question correctly, even after accounting for overall facility. The odds ratio when increasing from one emoji (e.g., 25) to the next (e.g., 50) was \( {e}^{25{\beta}_2}=1.07 \). In this dataset, the hypercorrection effect appeared to be stronger for younger students than for older students, and stronger for girls than for boys.

Finally, we note that, as Fig. 11 suggests, confidence in quiz A is positively correlated with facility in quiz A, rs(1,654) = .509, p < .001, and the relationship for quiz B is almost identical, rs(1,654) = .502, p < .001, indicating that students were similarly well calibrated in both quizzes. Their calibration did not measurably change across the intervening 3-week period.

Student confidence versus facility in quiz A and quiz B. Each point represents one student. The size of the point indicates the number of answers for which the student answered the questions in quizzes A and B with confidence. These plots are for responses where confidence was given in both quiz A and quiz B. Then, we grouped by student and only retained students with 10 or more answers; the result was 1656 students

5 Discussion

Analysis of data from the Eedi platform succeeded in confirming several findings from previous studies, and did so using a large dataset in an authentic learning context, in which students were answering questions set by their teachers as a normal part of their school learning, not specifically for a research study. In addition to this, we were able to uncover greater detail concerning relationships between students’ confidence and a variety of demographic variables, including gender, age and socioeconomic disadvantage. Finally, we found the first evidence for the hypercorrection effect in an authentic mathematics learning context.

5.1 The relationship between confidence and other variables

Previous research has shown that confidence is lower for girls, for older students and for students characterised as socioeconomically disadvantaged (e.g., Ganley & Lubienski, 2016; Mullis et al., 2020; OECD, 2013, 2019). However, exactly how these variables are interrelated was not known; in particular, whether the relative under-confidence of girls varies depending on age or socioeconomic disadvantage, or whether the decrease in student confidence with age can be fully accounted for by decreasing attainment, or whether the lower confidence of socioeconomically disadvantaged students might be completely accounted for by lower attainment.

In line with previous research (e.g., Foster, 2016; Mullis et al., 2020), the students in this dataset were generally well calibrated (Fischhoff et al., 1977), showing a positive correlation between the mean facility (the proportion of questions correct) for each student and the mean confidence (rs = .504, p < .001). This means that in general, students showed good awareness of which questions they could answer correctly and which they could not. We also confirmed previous research showing a higher mean confidence for boys than for girls (e.g., Foster, 2016; Frost et al., 1994; Ganley & Lubienski, 2016; Mullis et al., 2020; OECD, 2013, 2019). Figure 12 shows that the mean confidence for boys was higher for every decade of facility, although boys did not answer more questions, or answer more questions correctly, than girls. It might be hoped that the overconfidence of boys, and under-confidence of girls, could both be addressed through repeated use of confidence assessment over time, where accurate placement of confidence is incentivised (Foster, 2016, 2021). For the students in this dataset, there was a significant interaction between facility and gender (β = −0.052, p = .011), indicating that the relative overconfidence of boys was greater for lower-attaining students, which is a new finding. Helping lower-attaining students, both boys and girls, to gain an accurate sense of their strengths and weaknesses could be important in enabling improved student metacognition as an important facet of more effective learning.

Confidence against facility by gender, with facility split into decades. The paired histogram shows the distribution of students by gender in the different facility decades. Above each pair, we show the results of a Mann-Whitney U test, two-sided with Bonferroni correction. ns: .05 < p, *.01 < p ≤ .05, ** .001 < p ≤ .01, *** .0001 < p ≤ .001, **** p ≤ .0001

We also confirmed previous research showing that attitudes to mathematics tend to decrease across the primary to secondary school transition and continue to fall throughout lower secondary school (Galton et al., 2003; Greany et al., 2016; Mullis et al., 2020; Zanobini & Usai, 2002). In our study, this pattern was present across almost all decades of facility but was particularly marked across the primary to secondary transition (see Fig. 6). A new result from our mediation analysis was that only 18.7% of the relationship between age and confidence was mediated by decreased facility, meaning that there would appear to be more to students’ decreasing confidence than merely experiencing harder mathematics as they progress through school. However, it is important to note that the present study was cross-sectional and did not track the same students over time, so it is possible that these effects could arise from other changes, such as in teaching or curriculum, that were not principally age-related. Further longitudinal research should explore how students’ progress in mathematics from primary to secondary school, as increasingly challenging and abstract concepts are introduced, might be achieved without detrimental effects on their confidence.

Finally, we confirmed the findings of studies reporting that confidence decreases with increasing socioeconomic disadvantage (OECD, 2013, 2019). In our study, students classified as socioeconomically disadvantaged (defined as being eligible for either Free School Meals [Gorard, 2012] or Pupil Premium [Gov.UK, 2020a]) answered fewer questions than advantaged students, answered fewer questions correctly and had lower mean confidence. The extensive dataset available for this study allowed us to probe this relationship in more detail than had previously been possible. Our mediation analysis found that 67.0% of the relationship between advantage and confidence was mediated by increased facility, meaning that the remaining 32.5% was either directly related to advantage or mediated by other variables (measured or not). Consequently, our model predicts that for two students of equal mathematics attainment, but differing in socioeconomic disadvantage, the more disadvantaged student would have lower confidence. This implies that the experience of a disadvantaged student studying mathematics at school may be considerably worse than for an advantaged student in multiple ways, since not only are disadvantaged students on average less successful in their mathematics, but they also on average feel less sure of their mathematics than an equally well-achieving more advantaged student does. This could be a consequence of messages conveyed through school, such as setting practices, for example (see Connolly et al., 2019), or of factors outside of school, or a combination.

5.2 The hypercorrection effect in an authentic learning context

We also found support in this study for the hypercorrection effect (Butterfield & Metcalfe, 2001, 2006), for the first time in an authentic mathematics learning context. We found that the higher a student’s confidence in their initial incorrect response in quiz A, the more likely they were to answer the subsequent analogous question in quiz B correctly, 3 weeks later, even after controlling for student facility. Each one-unit increase on our 5-point emoji confidence scale for the incorrect response in quiz A was associated with a 7% increase in the probability of a correct answer on quiz B. In this dataset, the hypercorrection effect was stronger for girls and for younger students, and validating these findings in a new data set would be valuable. One major benefit of incorporating confidence assessment into diagnostic questions may be to prompt students to reflect on their confidence level when incorrect and so take advantage of the hypercorrection effect (see Barton, 2018a, 2020). This study provides encouragement that this effect operates beyond the tightly controlled research studies previously reported.

5.3 Limitations

This study explored students’ responses online, and caution may be needed in generalising from this to face-to-face classroom situations. However, the data were derived from real students in normal learning situations that incorporate both in-school and out-of-school engagement with the platform, so the data derive from an authentic learning situation. The diagnostic mathematics questions used covered a broad range of mathematics topics, and, although the questions used were all short questions, they spanned factual, procedural and conceptual understanding, as outlined in Section 1.

An important limitation of analysing confidence scores is that students may exaggerate their confidence for strategic purposes, beyond what they truly think, in order to present themselves more favourably to their teacher or peers (see Foster, 2016, 2021). We cannot completely rule out this possibility; however, the fact that confidence scores ranged across all of the emojis is evidence that large numbers of students were willing to register low confidence. One way in which to collect confidence measures with higher validity could be to implement confidence-weighted assessment, in which the student’s mark is increased when the student expresses high confidence and is correct but is decreased when the student expresses high confidence but is incorrect (see Dirkzwager, 2003; Foster, 2016, 2021; Rosewell, 2011; Sparck et al., 2016). Such an approach is intended over time to incentivise truthful confidence ratings and is particularly easy to implement in a multiple-choice model, where students can be asked to allocate, say, 100 marks across the four options A–D. This would allow a student to give a response of 0, 0, 50, 50, for instance, to express their feeling that they were sure that neither A nor B was correct but were completely unsure regarding C and D. We plan to explore the effects of such a model in our future research.

6 Conclusion

Students’ confidence in the responses that they give to mathematics questions gives insight into an important aspect of their learning of mathematics (Barton, 2020; Foster, 2016, 2021). Students’ confidence has implications for their achievement, as well as for their experience of studying mathematics in school, and their inclination, or otherwise, to pursue mathematics-related study beyond school (Paulsen & Betz, 2004). Most previous research into students’ confidence in mathematics has been carried out on a small scale or in situations deliberately contrived for research purposes. In the present study, we used a large dataset of students’ responses to diagnostic multiple-choice mathematics questions, generated in the course of students’ ordinary school learning, to confirm previous findings about the relationships between students’ confidence and other variables. We were also able to report new findings, such as that the relative overconfidence of boys was greater for lower-attaining students, and that the decline in confidence with increasing age could not be fully accounted for by a decrease in students’ success on harder mathematics. We also found that socioeconomically disadvantaged students on average feel less confident than equally well-achieving more advantaged students, suggesting that targeted support to socioeconomically disadvantaged students to improve their confidence could be valuable, alongside attempts to help raise their attainment.

Finding the first support for the hypercorrection effect in an authentic school mathematics learning context suggests that there could be benefits to students’ learning in exploiting this effect in lessons, as has been previously suggested (Barton, 2020). Future studies should, unlike the present study, track the same students over time, to investigate whether changes in confidence are associated with changes in teaching or the curriculum. It would also be important to examine school-level data, and the ways in which the Eedi platform is used differently in different schools or classes or with different teachers. For example, we do not know the extent to which teachers may have encouraged the students to reflect on their confidence explicitly (see Barton, 2020). In further research, we intend to examine different ways in which teachers might harness the confidence assessment feature of the platform to help students become better calibrated over time and benefit more from the hypercorrection effect.

Notes

Students could answer quizzes on the Diagnostic Questions website (www.diagnosticquesitons.com), the Eedi website (www.eedi.co.uk) or the Eedi mobile app. Confidence could not be recorded on Diagnostic Questions and some versions of the Eedi mobile app, so we include here only answers given on the Eedi website.

Free School Meal eligibility is a measure of low parental income, often used as an individual indicator of socioeconomic disadvantage (see Gorard, 2012).

The pupil premium is extra funding given to schools in England to raise the attainment of disadvantaged pupils (Gov.UK, 2020a).

Standardisation was by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation.

We note that the ns for each confidence level suggest a preference for confidence ratings of 0, 50 and 100 over 25 and 75. For this dataset, 29% of students used 0, 50, 100 only for at least 90% of their answers. For the full dataset, 23% of students used 0, 50, 100 for at least 90% of their answers, suggesting that this reduction of a 5-point scale to a 3-point scale was fairly common.

References

Baguley, T. (2012). Serious stats: A guide to advanced statistics for the behavioral sciences. Macmillan International Higher Education.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Barton, C. (2018a). How I wish I’d taught maths: Lessons learned from research, conversations with experts, and 12 years of mistakes. John Catt Educational Limited.

Barton, C. (2018b). On formative assessment in math: How diagnostic questions can help. American Educator, 42(2), 33.

Barton, C. (2020). Reflect, expect, check, explain: Sequences and behaviour to enable mathematical thinking in the classroom. John Catt Educational Ltd.

Burton, L. (2004). “Confidence is everything”—Perspectives of teachers and students on learning mathematics. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 7(4), 357–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-004-3355-y

Butler, A. C., Fazio, L. K., & Marsh, E. J. (2011). The hypercorrection effect persists over a week, but high-confidence errors return. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18(6), 1238–1244. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-011-0173-y

Butterfield, B., & Metcalfe, J. (2001). Errors committed with high confidence are hypercorrected. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 27, 1491–1494. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.27.6.1491

Butterfield, B., & Metcalfe, J. (2006). The correction of errors committed with high confidence. Metacognition and Learning, 1(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-006-6894-z

Carpenter, S. K., Haynes, C. L., Corral, D., & Yeung, K. L. (2018). Hypercorrection of high-confidence errors in the classroom. Memory, 26(10), 1379–1384. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2018.1477164

Clarkson, L. M. C., Love, Q. U., & Ntow, F. D. (2017). How confidence relates to mathematics achievement: A new framework. In A Chronaki (Ed.), Mathematics Education and Life at Times of Crisis, Proceedings of the Ninth International Mathematics Education and Society Conference (Vol. 2, pp. 441–451). University of Thessaly Press.

Clark-Wilson, A., Robutti, O., & Thomas, M. (2020). Teaching with digital technology. ZDM-Mathematics Education, 52(7), 1223–1242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-020-01196-0

Code, W., Merchant, S., Maciejewski, W., Thomas, M., & Lo, J. (2016). The Mathematics Attitudes and Perceptions Survey: An instrument to assess expert-like views and dispositions among undergraduate mathematics students. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 47(6), 917–937. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2015.1133854

Connolly, P., Taylor, B., Francis, B., Archer, L., Hodgen, J., Mazenod, A., & Tereshchenko, A. (2019). The misallocation of students to academic sets in maths: A study of secondary schools in England. British Educational Research Journal, 45(4), 873–897. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3530

de Bruin, A. B., & van Gog, T. (2012). Improving self-monitoring and self-regulation: From cognitive psychology to the classroom. Learning and Instruction, 22(4), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.01.003

Di Martino, P., & Zan, R. (2010). ‘Me and maths’: Towards a definition of attitude grounded on students’ narratives. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 13(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-009-9134-z

Dirkzwager, A. (2003). Multiple evaluation: A new testing paradigm that exorcizes guessing. International Journal of Testing, 3(4), 333–352. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327574IJT0304_3

Efklides, A. (2012). Commentary: How readily can findings from basic cognitive psychology research be applied in the classroom? Learning and Instruction, 22(4), 290–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.01.001

Fennema, E., & Sherman, J. A. (1976). Fennema-Sherman mathematics attitudes scales: Instruments designed to measure attitudes toward the learning of mathematics by females and males. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 7(5), 324–326. https://doi.org/10.2307/748467

Fischhoff, B., Slovic, P., & Lichtenstein, S. (1977). Knowing with certainty: The appropriateness of extreme confidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3(4), 552–564. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.3.4.552

Foster, C. (2016). Confidence and competence with mathematical procedures. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 91(2), 271–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-015-9660-9

Foster, C. (2021). Implementing confidence assessment in low-stakes, formative mathematics assessments. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-021-10207-9

Franz-Odendaal, T. A., Blotnicky, K. A., & Joy, P. (2020). Math self-efficacy and the likelihood of pursuing a STEM-based career: A gender-based analysis. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 20, 538–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42330-020-00105-7

Frost, L. A., Hyde, J. S., & Fennema, E. (1994). Gender, mathematics performance, and mathematics-related attitudes and affect: A meta-analytic synthesis. International Journal of Educational Research, 21(4), 373–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(06)80026-1

Galbraith, P., & Haines, C. (1998). Disentangling the nexus: Attitudes to mathematics and technology in a computer learning environment. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 36(3), 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003198120666

Galton, M., Gray, J., & Rudduck, J. (2003). Transfer and transitions in the middle years of schooling (7-14): Continuities and discontinuities in learning. DfES.

Ganley, C. M., & Lubienski, S. T. (2016). Mathematics confidence, interest, and performance: Examining gender patterns and reciprocal relations. Learning and Individual Differences, 47, 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.01.002

Gorard, S. (2012). Who is eligible for free school meals? Characterising free school meals as a measure of disadvantage in England. British Educational Research Journal, 38(6), 1003–1017. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2011.608118

Gov.UK (2020a). Pupil premium. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pupil-premium/pupil-premium

Gov.UK (2020b). Schools, pupils and their characteristics. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/schools-pupils-and-their-characteristics-january-2020

Greany, T., Barnes, I., Mostafa, T., Pensiero, N., & Swensson, C. (2016). Trends in Maths and Science Study (TIMSS): National Report for England. UCL Institute of Education.

Hannula, M. (2014). Affect in mathematics education. In S. Lerman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of mathematics education (pp. 23–27). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4978-8_174

Hannula, M. S., Leder, G. C., Morselli, F., Vollstedt, M., & Zhang, Q. (2019). Affect and mathematics education: Fresh perspectives on motivation, engagement, and identity. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13761-8

Kaye, L. K., Malone, S. A., & Wall, H. J. (2017). Emojis: Insights, affordances, and possibilities for psychological science. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(2), 66–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.10.007

Kyriacou, C. (2005). The impact of daily mathematics lessons in England on pupil confidence and competence in early mathematics: A systematic review. British Journal of Educational Studies, 53(2), 168–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2005.00289.x

Lim, S. Y., & Chapman, E. (2013). Development of a short form of the attitudes toward mathematics inventory. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 82(1), 145–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-012-9414-x

Ma, X., & Kishor, N. (1997). Assessing the relationship between attitude toward mathematics and achievement in mathematics: A meta-analysis. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 28(1), 26–47. https://doi.org/10.2307/749662

Marsh, H. W., Pekrun, R., Parker, P. D., Murayama, K., Guo, J., Dicke, T., & Arens, A. K. (2019). The murky distinction between self-concept and self-efficacy: Beware of lurking jingle-jangle fallacies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(2), 331–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000281

Massey, S. (2021). Using emojis and drawings in surveys to measure children’s attitudes to mathematics. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 1-13. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2021.1940774

Mendick, H., & Francis, B. (2012). Boffin and geek identities: Abject or privileged? Gender and Education, 24(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2011.564575

Metcalfe, J. (2017). Learning from errors. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 465–489. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044022

Metcalfe, J., & Finn, B. (2011). People’s hypercorrection of high-confidence errors: Did they know it all along? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 37(2), 437–448. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021962

Metcalfe, J., & Finn, B. (2012). Hypercorrection of high confidence errors in children. Learning and Instruction, 22(4), 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.10.004

Metcalfe, J., & Huelser, B. J. (2020). Learning from errors is attributable to episodic recollection rather than semantic mediation. Neuropsychologia, 138, 107296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2019.107296

Morsanyi, K., Cheallaigh, N. N., & Ackerman, R. (2019). Mathematics anxiety and metacognitive processes: Proposal for a new line of inquiry. Psihologijske Teme, 28(1), 147–169. https://doi.org/10.31820/pt.28.1.8

Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Foy, P., Kelly, D. L., & Fishbein, B. (2020). TIMSS 2019 International Results in Mathematics and Science. Retrieved from Boston College, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center website: https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2019/international-results/

OECD. (2013). Mathematics self-beliefs and participation in mathematics-related activities. In PISA 2012 Results: Ready to learn (Volume III), Students’ engagement, drive and self-beliefs (pp. 87–112). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264201170-en

OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What school life means for students’ lives. PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/acd78851-en

Panaoura, A., Gagatsis, A., & Demetriou, A. (2009). An intervention to the metacognitive performance: Self-regulation in mathematics and mathematical modeling. Acta Didactica Universitatis Comenianae Mathematics, 9, 63–79.

Paulsen, A. M., & Betz, N. E. (2004). Basic confidence predictors of career decision-making self-efficacy. The Career Development Quarterly, 52(4), 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2004.tb00951.x

Pepin, B., & Roesken-Winter, B. (Eds.). (2014). From beliefs to dynamic affect systems in mathematics education: Exploring a mosaic of relationships and interactions. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-06808-4

Pierce, R., & Stacey, K. (2004). A framework for monitoring progress and planning teaching towards the effective use of computer algebra systems. International Journal of Computers for Mathematical Learning, 9, 59–93. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:IJCO.0000038246.98119.14

Pinxten, M., Marsh, H. W., De Fraine, B., Van Den Noortgate, W., & Van Damme, J. (2014). Enjoying mathematics or feeling competent in mathematics? Reciprocal effects on mathematics achievement and perceived math effort expenditure. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(1), 152–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12028

Pomerantz, E. M., Altermatt, E. R., & Saxon, J. L. (2002). Making the grade but feeling distressed: Gender differences in academic performance and internal distress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 396–404. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.2.396

Rohrer, D., & Taylor, K. (2007). The shuffling of mathematics problems improves learning. Instructional Science, 35(6), 481–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-007-9015-8

Rosewell, J. P. (2011) Opening up multiple-choice: Assessing with confidence. Presented at the 2011 International Computer Assisted Assessment (CAA) Conference: Research into e-Assessment, 5-6 July 2011, Southampton, UK. http://oro.open.ac.uk/32150

Seabold, S. & Perktold, J. (2010). Statsmodels: Econometric and statistical modeling with Python. 9th Python in Science Conference. https://doi.org/10.25080/Majora-92bf1922-011

Sitzman, D. M., Rhodes, M. G., Tauber, S. K., & Liceralde, V. R. T. (2020). The role of prior knowledge in error correction for younger and older adults: Correction. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 27(4), 636–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825585.2019.1640443

Soderstrom, N. C., & Bjork, R. A. (2015). Learning versus performance: An integrative review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 176–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615569000

Sparck, E. M., Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2016). On the learning benefits of confidence-weighted testing. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 1(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-016-0003-x

Stankov, L., Lee, J., Luo, W., & Hogan, D. J. (2012). Confidence: A better predictor of academic achievement than self-efficacy, self-concept and anxiety? Learning and Individual Differences, 22(6), 747–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.05.013

van Loon, M. H., Dunlosky, J., van Gog, T., van Merriënboer, J. J., & de Bruin, A. B. (2015). Refutations in science texts lead to hypercorrection of misconceptions held with high confidence. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 42, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.04.003

Zanobini, M., & Usai, M. C. (2002). Domain-specific self-concept and achievement motivation in the transition from primary to low middle school. Educational Psychology, 22(2), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410120115265

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their extremely helpful comments on previous versions of this paper.

Availability of data and material

All data is available at https://github.com/Eedi/diagnostic-questions-and-student-confidence.

Code availability

All Python code is provided at https://github.com/Eedi/diagnostic-questions-and-student-confidence.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The second and third authors are co-founders of Eedi.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

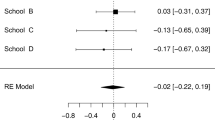

Appendix. Comparability of quiz A and quiz B questions

Appendix. Comparability of quiz A and quiz B questions

For the analysis of the hypercorrection effect, we need to know how similar the analogous questions are in quiz A and quiz B. We can test this by comparing the facility of questions in quiz A to the corresponding questions in quiz B. When calculating the facility of questions in quiz B, we excluded any answers from students who had already answered the corresponding question in quiz A. We might expect that quiz A, administered immediately after the teaching, would show higher facility than quiz B, which is a delayed test given some 3 weeks later. This might be expected to be particularly the case, given that, for quiz B, we include only those students who were not present for quiz A, and a likely reason for this could be that they were absent from school at that time, meaning that they are likely to have missed some of the teaching on that topic.

There were 6370 question pairs in the dataset from 7302 students in total. We identified N = 6232 for which there were at least 20 answers to the quiz A question, and at least 20 answers to the quiz B question where the student had not answered the question in quiz A. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test found no evidence that the distribution of the paired differences was unsymmetrical about the median (Mdn = −1.38, Z = 9,709,954.5, p = .994, see Fig. 13). Together with the fact that the median is very close to 0, this leads us to conclude that, despite the plausible concerns above, on average the difference in difficulty between quiz A and quiz B questions is too small to be of any concern.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Foster, C., Woodhead, S., Barton, C. et al. School students’ confidence when answering diagnostic questions online. Educ Stud Math 109, 491–521 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-021-10084-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-021-10084-7