Abstract

Detrimental circumstances (e.g., poverty, homelessness) may affect parents, parenting, and children. These circumstances may lead to children being labeled “at risk” for school failure. To ameliorate this risk, more school and school earlier (e.g., Head Start) is offered. To improve child outcomes, Head Start teachers are expected to bolster children?s academic readiness in a manner that is beneficially warm, circulating warmth in their classrooms to sustain positive teacher-child relationships and the positive climate of the classroom. The Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS; Pianta et al., 2008) is one tool by which these domains of warmth are assessed. There are, however, significant personal and professional stressors with which Head Start teachers contend which the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) does not consider in its scoring methods. Uplifting the voices of six Head Start teachers, the present study implemented individual and focus group interviews during the summer and fall months of 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, asking (a) What were the stories, histories, and lived experiences of these Head Start teachers with regard to stress and warmth in a time of crisis? and (b) How did these teachers understand and approach the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) and its measures of their warmth? Data demonstrated Head Start teachers engaged in a type of performativity to 1) mask their stress, potentially worsening their levels of stress in order to maintain warmth for their students’ sake, and 2) outwit the prescribed CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) observations. Implications and insights are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Increasing and potentially detrimental circumstances (e.g., poverty, lack of quality childcare) exist for some children in the United States (Mersky et al., 2021; Pianta, 1999; Walsh et al., 2019) and globally (Ulke et al., 2021; Wong et al., 2021). These factors may negatively affect parents and parenting (Brooks-Gunn et al., 2013; Jones et al., 2021), thereafter affecting children (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997; Hiilamo et al., 2021; Metcalf et al., 2022). As a result, children may be labeled “at risk” for school failure before kindergartenFootnote 1. In response, schooling writ large conceives and implements a paradigm in which children labeled at risk are welcomed to classrooms before Kindergarten in programming called pre-kindergarten (e.g., Universal Pre-Kindergarten, Head Start) in an attempt to “close the gap;” to be spaces where children find the academic and socioemotional support which may not, for many reasons (e.g., socioeconomic status, racial injustice, systemic societal inequality and inequity), be available in the home context.

Although the at-risk label is contentious (Ladson-Billings, 2007), the intention behind the implementation of such early childhood programming is not wrong and has been consistently demonstrated as beneficial for the long-term well-being and outcomes of the children for whom it is designed (Heckman & Karapakula, 2019). However, schools may be rife with structural issues (Anyon, 1980; Bowles & Gintis, 2011; Galindo, 2021; Phillips & Gichiru, 2021) which prevent labeled children from being fully served (Anderson & Ritter, 2017; Ferri & Connor 2010; Ladson-Billings, 2012). The demands of accountability and efficiency, for example, in United States public schools (Howard & Rodriguez-Minkoff, 2017; Pinar, 2012) may undercut efforts to ameliorate the at-risk label. Such structural issues may be particularly salient in how they affect teacher warmth and the teacher-child relationship, each demonstrated to be important to bolstering child outcomes in academic (Pakarinen et al., 2021; Pianta & Walsh, 1996; Rojas & Abenavoli, 2021) and self-regulation (Jones et al., 2014; Phillips et al., 2022) domains, for example.

Interrogating these assertions with an ecological lens of development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) revealed potentially powerful systems of reciprocal influence in classrooms by which teachers may be impinged and, thereafter, children disadvantaged. External factors, proximal (e.g., low pay, lack of agency) and distal (e.g., socioeconomic status), serve as forces that may affect the well-being of teachers of young children ultimately reverberating within the developmental influences of children. While this study sought to examine teachers’ well-being, it should be situated contextually in the theoretical understanding that the outwardly extending influences of teacher well-being, or lack thereof, may permeate the classroom context with downstream, cascading effects for children.

Teacher Stress

One such structural issue and factor of influence over teacher well-being can be found in increasing levels of stress (Darling-Hammond, 2001; Montgomery & Rupp, 2005; von Haaren-Mack et al., 2020). Even though the ECE industry was projected to be one of the fastest growing (Lockard & Wolfe, 2012), teachers are demonstrated to leave the field at rates of up to 25% per year (Bassok et al., 2021; Whitebook et al., 2014). These levels of attrition are demonstrated to be related to the particular conditions under which they operate (e.g., compensation, managing children; Curbow et al., 2000; Deery-Schmitt & Todd, 1995; Herman et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2022). In addition to these described teacher stressors which affect teachers, generally, ECE teachers also deal with teaching stress (Abidin et al., 2004, as cited in Gagnon et al., 2019)—stress stemming from the emotionality of working with young children (Buettner et al., 2016; Jeon et al., 2016). Importantly, ECE teacher (e.g., Head Start, Early Head Start) well-being has recently been centered and demonstrated as predictive in the decision to leave the profession (McCormick et al., 2022; McMullen et al., 2020).

Not unlike other ECE teachers, Head Start teachers are expected to manage the daily facets of a busy and productive classroom. Yet, as Head Start remains the main source of ECE for children and families in need in the United States (Watts et al., 2018), Head Start teachers are held to further considerations. Pessimistically, children enrolled in Head Start programming have demonstrated greater conduct problems and been deemed as less skilled in terms of social competence (Driscoll et al., 2011) when compared to children who attend other types of programming (Kaiser et al., 2002; Randolph et al., 2000; Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1998, all cited in Driscoll et al., 2011)—which may result in additional stress for teachers. Moreover, Head Start teachers are important stakeholders in reshaping the narrative around the at-risk label. It is understood that they play a significant role in ensuring that children from historically overlooked and marginalized communities are kindergarten-ready by creating rigorous curricula, creating individualized plans for children, working with local, state, and federal funding agencies, and meeting standards of quality and success. Yet, they have little voice in the processes of school programming writ large.

The current COVID-19 global pandemic has added an additional layer of stress for ECE teachers. Research undertaken during the pandemic demonstrated that teachers experienced upheaval regarding approaches and methods of teaching (Kim, 2020), including the change from in-person to remote learning (Dias et al., 2020; Steed & Leech, 2021). Important to this investigation, overall teaching experiences (Kim et al., 2021), how teachers interacted with students (Szente, 2020), and the emotional toll (Bigras et al., 2021) of the pandemic additionally burden stressed ECE teachers. As a result, national data indicated that 35% of the ECE workforce was laid off between February and April of 2020 (U.S. Department of Labor, 2022). Most saliently, ECE teachers of color in urban centers were demonstrated to experience additional stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public school teachers working at urban schools, for example, are demonstrated to experience stress and burnout at levels beyond that of peers working in non-urban settings (Bottiani et al., 2019). During the COVID-19 pandemic, ECE teachers in urban centers were demonstrated to be similarly taxed: quantitative and qualitative data indicated their ability to care for themselves or attend to their own mental well-being was reduced over and above typical baseline levels (Souto-Manning & Melvin, 2022). Given that, for troubling reasons, the COVID-19 pandemic most greatly affected brown and black populations in the United States (Enriquez et al., 2021; Lawton et al., 2021) early on, ECE teachers working in these neighborhoods and communities were likely witness to the suffering of the children and families in their classrooms. The total toll on these individuals may remain incalculable; another invisible scar on the early childhood workforce.

These stressors, similar and distinct from those that may exist in a child’s home, potentially impact the relationship between a teacher and child (Chen & Phillips, 2018; Pianta, 1999; Sandilos et al., 2018), much as they may the relationship between parent and child. For example, the way the teacher-child relationship is described as either close or conflicted has bearing on how teachers understand, and are affected by, teaching stress (Gagnon et al., 2019). The literature demonstrates non-White children to be disproportionately represented in special education (Kramarczuk Voulgarides et al., 2017) and to disciplinary measures (e.g., suspensions, arrests; Anderson & Ritter, 2017; Gilliam & Shahar 2006). It may be hypothesized that one mechanism by which these issues have become problematic in ECE classrooms may be, at least in part, due to the effects of teacher stress fueling a potentially dangerous disconnect between teachers and their students.

Early childhood education teacher stress is a reality that may stifle the success of children characterized as at-risk in programming like Head Start. In fact, the demonstrated effects of stress on the parent-child relationship (Brooks-Gunn et al., 2013; Conger et al., 1999, as cited in Conger & Conger 2008; Shonkoff et al., 2012; Ward & Lee, 2020), those which ECE programming like Head Start attempt to ameliorate, may in fact be mirrored in the context of the classroom. For example, when examining the associations between teacher-reported job stress and observed interactions between teachers and children, control group teachers who reported higher stress were less emotionally supportive of students when compared to teachers in the treatment group who reported less stress (Sandilos et al., 2018). These effects of stress on teachers are of material concern as the classroom is demonstrated to be a space where teacher emotional and physical well-being may be imperiled (Guglielmi & Tatrow, 1998; Harmsen et al., 2018; Phillips et al., 2016), potentially rupturing the relationship between teacher and child (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009; Gagnon et al., 2019).

Teacher-Child Relationships and Teacher Warmth

Early childhood programming, like Head Start, is ideally warm, nurturing, social, and relational (Acar et al., 2018; Bergin & Bergin, 2009; Pianta, 1999). Emotionally supportive teachers can be observed as warm, kind, and sensitive to the socioemotional needs of each child, and thoughtful about how they respond to children. They offer gentle guidance, engage in positive communication, and demonstrate respect through eye contact, respectful language, and a warm and calm voice. (Merritt et al., 2012, as cited in Pianta et al., 2008). Examination of the teacher-child relationship has roots in the work of Brophy & Good (1974) who characterized this union as more than the impartation of lessons. Their argument suggests that teaching is nuanced; more complex and relationally-based than what may be portrayed as merely dolling out lessons.

The key qualities of these relationships [between teacher and child] appear to be related to the ability or skill of the adult to read the child’s emotional and social signals accurately, respond contingently based on these signals (e.g., to follow the child’s lead), convey acceptance and emotional warmth, offer assistance as necessary, model regulated behavior, and enact appropriate structures and limits for the children’s behavior. (Pianta et al., 2003, p. 204)

Offering “emotional warmth,…assistance as necessary, [and] model[ing] regulated behavior,” (p. 204) then, may be a heavy lift for ECE teachers, and specifically Head Start teachers, given the contextual circumstances of stress under which they operate. Yet establishing this warmth may be of critical importance given the literature demonstrates that children potentially depend on teachers as surrogates for mothers at the nursery school age (Ainsworth, 1969; Jennings, 2019), children in classrooms, as in life, looking to adults in the environment to provide experiences that educate (Belsky, 1984). The literature demonstrates that relationships forged between teachers and children considered at risk have the potential to ameliorate the associated risks of academic and socioemotional failure in school (Burchinal et al., 2002 as cited in Driscoll et al., 2011; Varghese et al., 2019). For example, children labeled at risk in kindergarten and who were subsequently placed in first grade classrooms with teachers who offered instructional and emotional support demonstrated the type of relationship with their first-grade teacher and achievement scores in line with peers who were not previously labeled at risk (Hamre & Pianta, 2005). Conversely, those children labeled at risk in kindergarten and who were subsequently placed in classrooms which were not described as instructionally and emotionally supportive did not show similar gains (Hamre & Pianta, 2005). The classroom environment, its social and emotional ethos, and the approach teachers engender matter in bolstering students (Wang et al., 2020).

The Classroom Scoring Assessment System (CLASS)

To ensure necessary teacher and classroom environment warmth is sustained, observation instruments categorizing teacher-child relationships and interactions between these groups (i.e., Classroom Assessment Scoring System; CLASS; Pianta et al., 2008) are implemented in Head Start classrooms. Widely used, the CLASS is an instrument used to record three domains of interaction between teacher and child: (1) Emotional Support, (2) Classroom Organization, and (3) Instructional Support. The Emotional Climate domain is composed of subscales of teacher sensitivity, behavior management, positive climate, and negative climate (La Paro et al., 2004; Pianta et al., 2008).

To implement the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008), trained individuals observe and record interactions between teachers and children. Implementing a 7-point Likert scale, the CLASS measures teacher sensitivity as responsiveness to child needs, behavior management as teachers’ ability to structure the classroom so that children understand what is expected at different times, positive climate as the enjoyment expressed in instructing, and being directly with, children, and negative climate (reversed scored) as how teachers demonstrate displeasure or frustration (e.g., anger; Raver et al., 2008). The higher the CLASS score in each domain, the more effective the teachers are rated.

To consider the opposing forces at play in ECE classrooms, this investigation sought to center the voices of six Head Start teachers. Operationalizing teacher stress as the independent variable and teacher warmth as the dependent variable, then, this investigation asked (a) What were the stories, histories, and lived experiences of these Head Start teachers with regard to stress and warmth in a time of crisis? and (b) How did these teachers understand and approach the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) and its measures of their warmth?

Consistent with qualitative methodologies, in particular that of Bogdan & Biklen (2007), Creswell and Clark (2018), and Luttrell (2009), it is important to note that this investigation did not attempt to establish causality. Rather, its purpose was to secure the rich and layered understandings of participating Head Start teachers’ conceptions of stress and warmth, and the means by which they pushed back against the structural and/or institutional forces which burdened them with stress and, it is hypothesized, limited the warmth circulating in the classroom context.

Materials and Methods

Head Start Teacher Data

Informed consent was obtained from participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as well as Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols, ensuring participants’ rights and privacy. The research was conducted in accordance with APA ethical standards in the treatment of the study sample.

Participants

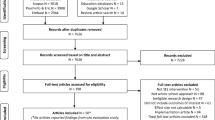

To recruit study participants, ECE leaders, policy makers, community programs, and colleges of education in the city of study were contacted. Recruitment materials approved by the IRB were provided to these people and institutions via email. These were then distributed to Head Start faculty. Nine Head Start teachers in seven different programs indicated their participation interest. After initial contact, six female teachers participated in this protocol; the remaining three did not return emails, calls, and/or text messages which attempted to engage participation. Of the six participating teachers, one self-identified as Asian, one as Black, and four as White. Five of the six teachers completed a master’s degree; the remaining teacher received a certification (see Table 1).

In addition to demographic data, recruited teachers provided data with regard to socioeconomic status (see Table 2).

Teacher Interviews

Each teacher participated in two individual interviews (Bogdan & Biklen, 2007) which were interspersed by one focus group interview (Krueger et al., 2001; Morgan, 1996). Both individual and focus group interviews were semi-structed (Bogdan & Biklen, 2007). Themes for the first individual interview were centered on well-being and were conceived using Spradley’s (1979) method of interview. Once transcribed, interview data were analyzed to pull emerging themes (Bogdan & Biklen, 2007; Horvat, 2013; Seidman, 2013) and to create questions for the focus group interview (Krueger et al., 2001; Morgan, 1996). Similarly, responses from the focus group interview were analyzed to create questions for the final individual interview. (See Appendix for a sampling of interview questions.)

As to timing, the first individual interviews were conducted in August of 2020, the two focus groups (each with three teachers) occurred in October, and the second individual interviews were conducted in November and early December. While it may be the case that some Head Start teachers and programming have a summer vacation, the teachers of this study were employed at year-round Head Start centers. As such, there was no distinction in teacher availability or vacation between individual or focus group interviews. As a result of the on-going COVID-19 pandemic, interviews were conducted and recorded over a teleconferencing application (i.e., Zoom). Teachers were compensated with an electronic gift card and a selection of children’s books for their classroom.

Analysis

Upon completion of individual and focus group interviews, recordings were transcribed and inductively analyzed for emerging themes (Bogdan & Biklen, 2007; Horvat, 2013; Seidman, 2013). Although the same criteria of quality typically applied to quantitative data (i.e., internal validity, generalizability, reliability, objectivity) cannot easily be applied to qualitative data, the criteria of trustworthiness (i.e., credibility, transferability, dependability, confirmability; Lincoln & Guba 1985) can (Korstjens & Moser, 2018). Therefore, to ensure the trustworthiness of the qualitative data of this investigation, Investigator Triangulation (Denzin, 1978) and Data Source Triangulation (Carter et al., 2014) were employed. The former speaks to the cooperation and comparison of thinking and coding between the members of the research team (Denzin, 1978). The latter speaks to the multiple sources from which the qualitative data were collected (i.e., individual, focus group interviews; Carter et al., 2014), These separate sources provided distinct opportunities allowing participating teachers to share thinking and experiences in answering the questions of this investigation. These two sources allowed for corroboration in the data and a wider perspective of the teachers who shared independent thoughts (Fontana & Frey, 2005), and as a part of the group, spoke collectively on issues and topics that held importance (Morgan, 1996).

Findings

The current study aimed to record the stories, histories, and lived experiences of Head Start teacher stress and the ways stress influenced classroom warmth. Additionally, the study sought to determine what role, if any, the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) played in how teachers managed and abated stress while imbuing their classroom with warmth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Individual and focus group interviews with participating teachers qualitatively revealed opposing forces in Head Start classrooms that required teachers to compromise their authenticity in interactions with children, parents, and administration. Administrative expectations, for example, were countered with teacher-reported limitations in latitude to meet children where they were emotionally, socially, and developmentally. What follows is an accounting of the ways teachers described these expectations, and the subversive ways they challenged them.

Theme 1: Performativity Prevailed Over Teacher Honesty and Vulnerability

On the one hand, participating teachers noted issues they characterized as important to the development of children (e.g., modeling of emotion, partaking in honest, vulnerable conversations, centering teacher-child relationships), especially in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. To illustrate this point, one teacher, RH noted the importance of expressing personal emotions with students in order to teach emotion. Displaying the range of emotions for her students, she illustrated the fact that “adults also not only feel…happy or they’re not always calm. They might feel upset, or…frustrated and they might feel annoyed at times, just like everybody else” (Focus Group 1). Another teacher, SS, added:

The [children] can see that it’s okay to feel frustrated. It’s okay to feel annoyed and that there’s nothing wrong with feeling these things. And I might talk about how, “Well, right now I want to scream. Right now, I want to pound. Right now, I want to…but that’s not okay. It’s okay to do the breathing right now,” or “It’s okay for me to stomp my feet.” (Interview 1)

However, the participating teachers of this study identified several obstacles limiting the described factors they understood to be valuable for child development inside their Head Start classrooms: curricular mandates and the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) assessment, for example.

Theme 2: Curricular Mandates Prevented Following a Child’s Lead

The Head Start teachers of this study spoke at great length about the required curriculum in their classrooms. Briefly, one such example of this mandated curriculum described by the teachers of this study is Creative Curriculum (Dodge, 1988; Dodge et al., 2002). Created in the 1970s, more than half of public pre-kindergarten teachers participating in a National Center for Early Development and Learning (NCDEL) study indicated they were using either Creative Curriculum or HighScope curriculum by 2012 (Michael-Luna & Heimer, 2012). Each curriculum was espoused for its focus on the child and how classroom practices were centered on development and socio-cultural understanding. However, criticism followed. For example, these curricula have been critiqued with regard to how they may (not) account for diverse populations of English language learners (Michael-Luna & Heimer, 2009). More recently, the literature has demonstrated reliance on Creative Curriculum or Responsive Classroom, a third example of curriculum in classrooms, as limiting the expression of emotions between teachers and children (Garner et al., 2019). In response to these criticisms, new curricula continue to flood the market. Frog Street, for example, brands itself as bilingual in design, and as “a comprehensive, research-based program that integrates instruction across developmental domains and early learning disciplines” (Schiller, n.d.). As was the case for previously developed curricula, evaluating whether new curricula account for teacher well-being and whether they offer teachers the necessary freedom to follow a child’s lead will be critical work for the future.

The most senior participating teacher of this study, AM, spoke to this idea of limited emotional relations by stating, “Any teacher who is following everything that’s on her lesson plan, is not [following] the kids” (Interview 1). AM continued by stating that she understood program curriculum as a tool designed to assist teachers. However, she also spoke to obvious problems with such methods of management. She noted that the continued implementation and layering of curriculum into classrooms served to prohibit the fullness of teacher-child relationships, as well as to inhibit teachers from attending to children’s individual needs (Interview 1).

AM opined that the tenets of Creative Curriculum, for example, suggested that no two classrooms should be the same – in look, sound, or feel. AM continued her description of the necessary differences in classrooms as a function of different children in these spaces – each arriving with different needs, knowledges, histories, and abilities. Yet, the described tension between curricular goals and the reality of what occurred in her Head Start classroom persisted (Interview 1). RH reflected, for example, on the necessity “to do lots of Mighty Minutes,” a component of Creative Curriculum, in order to fulfill administratively-set expectations. Designed as a quick and easy means of introducing objectives for learning and development (e.g., letter, number awareness) to students, these flashcard-like props created unintended consequences for children and teachers (Interview 1). Regarding Mighty Minutes, a fourth teacher, AN, suggested these served as a divisive point between teachers and administrators:

Thinking about…Creative Curriculum, when we were being super harped on [by the administration] about…you had to follow the curriculum, “You have to show me you’re doing a Mighty Minute every second of the day and doing those instructional teaching cards.” And it was like, “If we don’t get this, we will not have funding.” That was at the beginning of last year, and it was really interesting. So, I’m like, “Well, I wasn’t able to get to that. I’m not going to just ignore my students and do something that they’re not into.” That, to me, seems like a terrible teacher. (Focus Group 2)

Theme 3: Assessments Induced Teacher Stress

With regard to the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) assessment, teachers cited the tool as an unrealistic judgement of their abilities, one that served the purposes of program funding more so than an authentic assessment of their warmth or their ability to engender warmth in the classroom, one that induced stress.

And same thing with the CLASS assessment that we all have to do. It’s you know, the director is like, “We need to be at seven!” And I’m like, “Yeah, you’re not supposed to be at seven. Like that is like literally impossible. So, I don’t know what to tell you.” But, you know, I get that her job is about the money. She’s trying to make sure we all have jobs and I appreciate that. And then it’s up to us to be like, “Well, this is the reality.” (Focus Group 2)

Powerfully, RH noted

If I’m being a hundred percent honest here like, you know, the kids’ assessment or CLASS assessment, they’re coming…they’re coming to observe you. And, you know, of course, you know when the kids’ observation scores come, you want the best score, you want the high score, you want them to rate you at the best. So, I think that...with that score, it’s kind of unwritten, but you kind of have to consider...[take] into consideration teachers are trying to put up their best, you know, best self, you know, best classroom-self because that…that one day of observation is coming. (RH, Focus Group 1)

.

This desire for the idealized “best score, the high score” (RH, Focus Group 1) revealed the impossibility of the pressure teachers put upon themselves in consideration of the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008), and the limitations which it engendered in classrooms where warmth and relationships were paramount. These two factors, curricular mandates and the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008), instituted additional stress for teachers working under already stressful conditions and in the stressful zeitgeist which was (and remains) the COVID-19 pandemic. RH described her method of coping as follows:

I guess dealing with that stress, speaking solely from my experience, dealing with the stress, I feel like now I reflect back and I think I didn’t...handle it very... I didn’t handle it very well because sometimes I will have a very stressed face... and families will come in and see that, like see on my expression that I’m stressed, but it’s not because I don’t love the job...or I don’t love the kids or I don’t want to see them.... It’s just like there’s just so many changes that needs to be, you know, that are happening that I need to quickly be flexible and adapt. I’m just like, “Oh my god.” (Interview 1)

When it was…[a] stressful day, it would be all over my face and I should have done better at…masking that, but I wasn’t able to. And, parents [and administrators] can see my face, and I looked stressed out and…drained, and they’re probably thinking, “Ugh, does she not like [her] job?” (RH, Interview 1)

In conflict with her expressed understanding of the importance of the demonstration of emotion, RH noted that she could not reveal her true self to school leadership or parents. It was better to “mask” and conceal the uncertainty, stress, and fatigue she endured. To accommodate the tension created between these two circumstances, it was the case that teachers engaged in a form of performativity whereby they necessarily feigned warmth, “masking” their stress, with children, parents, and members of their administration. In doing so, the participating teachers obscured the purposeful and authentic processes they acknowledged as important to teach children skills that may ultimately help abate behavior problems and advance academic gains. When probed as to why they felt compelled to perform or engage in inauthentic ways, teachers revealed that child emotions and the management of child emotions were diminished in importance (1) when compared to academic readiness (e.g., literacy, mathematics) for the purposes of Kindergarten testing and entry, and (2) as a result of classroom assessments (e.g., CLASS; Pianta et al., 2008), a necessary component of program funding, for example.

As an example of this performativity, RH described a practice by which she ran previously instructed lessons in order to be able to maintain her classroom in a functional, cooperative, and warm way.

You kind of do the practice routines, you kind of do what…what you’ve already done before, so [the children] are not, like, confused, “What are we doing now?” and then that...that brings up more problematic behaviors or like, you know, they’re like confused or they’re out of routines or they’re like, “What’s going on?” Like, “This is different.” (Focus Group, 1)

This performativity was discussed by both RH and JM in separate circumstances as donning a mask as needed for the sake of convincing children and parents of their well-being, for the sake of CLASS outcome scores, program funding and continuity, and job security.

JM described:

[When] it came to my co-teachers, who were typically old school, they would wear the mask. Okay, so we had like two hundred, I don’t know, how many days of school, where [the lead teacher is] being herself [no mask], but when the observers come in she knows she...she switches. So, she would wear the mask, and that bothers me. And I’m trying to tell her, you know, “Maybe we should try to implement this all through the year so we won’t confuse the kids.” So...and I think the observers see it. They will see a disconnect with me and her because you can’t...Even though she’s wearing a mask, they could tell that she’s wearing a mask, and that’s not real and we’re not in sync. (Focus Group 2)

Further, JM echoed RH’s sentiment in a follow-up interview.

It’s like when you think about the student’s performance decreasing, even though there’s warmth in the classroom [according to CLASS scoring] apparently there’s something that that student is missing. And maybe that warmth that they see, I guess when the...the evaluators come in and they see it, we might be just putting on the mask. Because we’re not, like I, aren’t dealing with the real issues involved. One thing I think that warmth comes with being honest and being real. Because in a…in a…in a community, in an environment, is the relationship. In a relationship, there are gonna be problems. There’re going to be fights. [There’s] going to be friction. And just yesterday, I told my kids that, you know, “We’re working together and we’re gonna...we’re gonna disagree.” The kids, we’re going to disagree, but there’s a way we have to learn how to disagree. (Interview 2)

Taken collectively, the qualitative data were analyzed to reveal that the stories, histories, and lived experiences the teachers shared were in tension with, and perhaps in direct opposition to, the necessary workings of the school in which these teachers operated. This tension, therefore, resulted in acts of subversion through which teachers could hold two truths at the same time: their understanding of the importance of warmth and teacher-child relationships and accomplishing mandated tasks as per their schools’ direction.

Discussion

The present study qualitatively interviewed six Head Start teachers during the summer and fall of 2020, at the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, asking (a) What are the stories, histories, and lived experiences of these HS teachers with regard to stress and warmth? and (b) How do these teachers understand and approach the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) and its measures of their warmth and the circulating warmth in their classrooms? Teachers revealed that they engaged in a type of performativity to (1) mask their stress, potentially worsening their own levels of stress in order to maintain a personal and environmental warmth for their students’ sake, and (2) outwit the required CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) observations in an effort to secure their jobs, secure school/program funding, and maintain the status quo expected of them. Why would the participating Head Start teachers of this study feel compelled to do such things? For the sake of parsimony, the remaining discussion section is focused on the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) and the ways it required Head Start teachers to mask their authentic selves, to engage in a type of performativity for the sake of engendering warmth in teacher-child relationships and in the Head Start classrooms where they worked.

The CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) was demonstrated to be problematic in this study. A tool of assessment meant to capture warmth, in part, in interactions between teachers and children as well as that which circulates in the classroom environment. It was also demonstrated to be a tool that may instead (a) capture a prescribed form of warmth, perhaps not accounting for all the varied forms of warmth circulating in a classroom; (b) may be overexposed and overemphasized, perhaps no longer serving as the trustworthy measure of classroom and teacher warmth which it was intended; and (c) may have counterproductively induced teacher stress while attempting to assess teacher warmth.

The problematic findings of this study regarding the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) mirror issues previously demonstrated in the literature. In the Australian context, for example, Thorpe et al. (2022) demonstrated the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) as an instrument designed to quantify the relational value of the classroom context, and yet one which may suffer from measurement error, both, in terms of its design and its implementation by observers and those who interpret and report outcomes. Further, the CLASS has been demonstrated to have tenuous associations with measures of child outcomes (Zaslow et al., 2010) perhaps as a result of rater effects (Styck et al., 2021). Perhaps most importantly, given the fact that the demographics of the United States continues to increase in numbers of culturally, ethnically, racially, and linguistically diverse children (Colby & Ortman, 2015), the literature demonstrates that instruments of classroom assessment, like the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008), may be culturally amiss (Osei-Twumasi & Pinetta, 2019). As a result, expanded thinking and scholarship around new forms of measurement like the Classroom Assessment of Cultural Interactions (CASI; Jensen et al., 2018) may be taking the lead. Although by no means exhaustive, these highlighted limitations of the CLASS were brought to bear in the findings of this investigation. The impacts and implications of such factors are discussed below.

Some Types of Warmth “Count” and Others Do Not

While the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) is validated to assess, in part, warmth in interactions between teachers and children as well as in the classroom environment, it may be the case that there are other forms of warmth for which the CLASS does not and cannot assess. Developed in alignment with normative, Global North, White standards, and as a result of Likert scale scoring, the CLASS may miss positively coding for warmth which may not reflect that which is detailed in its manual. This may have pronounced effects in Head Start classrooms for teachers who are of differing cultural, ethnic, linguistic, or racial backgrounds, differing from that which the CLASS’s standards were composed (i.e., teacher sensitivity, behavior management, positive climate, and negative climate; La Paro et al., 2004; Pianta et al., 2008).

Ware (2006), for example, demonstrated qualities of teachers, evoking the term warm demanders, and describing the exemplary traits of African American teachers to include “an ethic of caring, beliefs about students and community, and instructional practices” (p. 428). Irvine & Fraser (1998) include teachers who “provide a tough-minded, no-nonsense, structured and disciplined classroom environment for kids whom society had psychologically and physically abandoned” (p. 56). Ware (2006) and Irvine & Fraser (1998) reject the notion that qualities of warmth and discipline are mutually exclusive. Particularly relevant in the African American communities of teachers and children, communities for whom research that bolstered their relationships and work has been lacking, this duality was particularly relevant. Ware (2006) argued that “there are unique and culturally specific teaching styles that contribute to the academic success of African American children and other children of color” (p. 428). Bondy & Ross (2008) go further stating, “a teacher stance that communicates both warmth and a nonnegotiable demand for student effort and mutual respect…is central to sustaining academic engagement in high-poverty schools” (p. 54).

Additionally, Falicov (1999) demonstrated authoritarian speech among Latinx children and families as an accepted part of the community. Yet, this type of speech, distinct from White communities and from that which would merit regard according to the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) manual, is generally considered common and inoffensive in Latinx communities. However, demanding and authoritarian speech directed at children in classrooms under CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) observation may be regarded, and therefore misinterpreted, as negative, counting against teachers’ assessments. There is an obvious tension here with regard to Head Start classrooms as the demographics of the United States (Colby & Ortman, 2015) and those of Head Start classrooms (44% White; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.) continue to change. These statistical changes have, in fact, warranted a body of literature that centers on the means of approaching early childhood education, in all ways, through a multicultural lens (Arzubiaga et al., 2009; Souto-Manning, 2013). Hand in hand with non-White, non-Western theoretical framings of early childhood development and education (Rogoff, 2003), the approach to early childhood education is broadening, as ought to be the case given the discussed changes of demography, allowing for variability in perspective, for affordances for non-White children, and for the learning that can powerfully take shape in their ECE classrooms.

The CLASS as Overused and Overly Relied Upon

In addition to the critique of the lack of cultural variance of warmth, the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) may also suffer from issues of trustworthiness. As demonstrated in this study, it may be the case that the CLASS, although widely in use (Gordon & Peng, 2020), may be overused in the context of early childhood classrooms. Used as a form of professional development, CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) observations may be “comprised of a monthly cycle of video-based self-reflection, peer coaching, and mentoring and bimonthly workshops focused on selected…CLASS dimensions;” it may also be implemented as year-long professional development (Zan & Donegan-Ritter, 2014, p. 93), for example. Described and elevated on the Head Start website, such consistent use of the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) as a tool of measuring teacher-child interactions and classroom warmth, for example, may have unintended consequences which the teachers of this study spoke to freely. The participating teachers of this study represented the CLASS as not only a predictable event, but also one that predictably induced stress. Returning to RH, she shared the manner by which she outwitted the observation and assessment: she reran lessons already conducted so as to make sure that the children in her classroom “would know what to do, there wouldn’t be any chaos” (RH, Interview 1). The teachers of this study spoke to an idealized “best score, the high score” (RH, Focus Group 1) which they hoped to achieve. These conversations also revealed the impossibility of these thoughts and desires, ultimately bringing forward the stress that teachers deal with when contending with the CLASS.

Feedback Loop: Wearing a Mask of Warmth to Hide Stress

Hills et al., (2019) demonstrated that simply being observed was enough to induce stress, and to reduce the ability of the one being observed to perform the task in question. The participating teachers of this study applied this same logic to the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008). Not only were the teachers stressed as a result of the observation, but so too because of how the CLASS results were interpreted: job security and Head Start program funding. AN, for example, described her administration’s attention on training teachers to the generalities and specifics of the CLASS assessment, all connected to outcomes for the program. Teachers, then, were left with a choice according to the themes of this study: act genuinely during CLASS observations, revealing levels of stress, understanding the likelihood of scoring poorly and risking funding and job security or act disingenuously, performing for the sake of the CLASS assessor, obscuring stress, scoring well and elevating program success. Their choice of performing or not was really no choice at all. They felt compelled to act inauthentically, despite their cognitive understanding of the many reasons why this behavior was problematic for them and for their students, in order to follow the, perhaps, tacit direction of the Head Start program.

The demonstrated stress findings of this study were not surprising to me, a former preschool teacher. Having been routinely observed by administrators, other faculty members, and by parents, the teachers’ descriptions conjure memories of nerves and anxiety, sweaty palms, and a dry throat. The psychological literature around observational stress (Hills et al., 2019), for example, helped to demonstrate why this may be the case for classroom teachers. The difference, however, is that the teachers of this study operated under tacit and/or explicit expectations of success with regard to their performance on the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) and, according to them, thereafter associated these observations with program funding and their own job security – reasons that may amplify whatever naturally occurring stress response may result from being observed. And while some stress is naturally occurring and even productive for adults, chronic stress of the type reported by the teachers of this study, is demonstrated to be detrimental (Shonkoff et al., 2012).

The three raised issues of these findings are supported by the existing literature and add further color to the potential of implications for early childhood education teacher and/or classroom practice and policy (Maier et al., 2020). While the necessity of quantifying pre-kindergarten as being high-quality for all children, and especially so for children who have been historically and structurally overlooked and marginalized, is critical, this task remains elusive given the inherent limitations imbedded in such instruments. In addition to the previously noted lack of cultural awareness, for example, the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) has also been demonstrated to be limited in predicting pre-kindergarten skills of math, language, and executive function (Guerrero-Rosado et al., 2021; McDoniel et al., 2022) for children, and as not individualized to children’s specific learning (Maier et al., 2022; Moffett el al., 2021). There is more recently a growing body of literature that puts forward alternatives to strictly measuring quality by the narrow delineation which is the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008). Recommendations are now being made by think tanks like MDRC, for example, who offer guidelines of newer scales meant to capture information where the CLASS falls short (Weiland & Guerrero-Rosada, 2022). It is wise to remember at this junction, however, when new instruments are coming to the fore, that teachers, those who work closest to children, those who know the students best, remain outside of the privileged circles of researchers and change-makers who design and enact the very vehicles which, in ways, mandate their teaching, dictate their performance, and determine, to large extent, the pressures they may feel while working in the classroom. Real change, perhaps, begins by listening to teachers first, acting as partners with them in the creation of such measures, and thereafter supporting them in daily experiences that bolster them rather than debase them by requiring them to perform. It does not have to be the case that measuring classroom quality in order to promote the well-being of children who may be deemed at risk for school failure and listening to and engaging with teachers’ voices, stories, histories, and lived experiences are mutually exclusive. The more proficient we, researchers, become at combining these, I argue, the greater the likelihood for beneficial gains for all stakeholders, and especially for children.

Conclusion

Although the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) was intended to serve as a means of feedback and support for teachers, it may be the case that the tool has become somewhat of a liability for teachers, for school programs, and potentially for child outcomes. The participating teachers of this study revealed that a reliance on the CLASS for administrative purposes, for funding decisions, for program direction resulted in additional stress causing teachers to be inauthentic. This outcome, although potentially associated with a higher score on the CLASS, translated to inauthentic experiences with children, with parents, and for what? What good is more school and school earlier for children characterized as at risk of school failure if the programming is influenced in ways that are problematic? What good is a higher CLASS score for teachers or for schools if the score is simply an inaccurate outer expression masking inner turmoil for teachers? Who is benefitting? JM wisely noted that warmth was best conveyed in classrooms through honest conversations, honest interactions, the honest give and take between the members of a school community. In this spirit, this manuscript concludes with a call to look at the types of warmth that circulate in classrooms in more honest ways: those that value diversity, collaborate with teachers, and protect the genuine nature of relationships between teachers and children.

Like any study, this study has several limitations. The first and perhaps most important to note is that this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and as such, the sample size of participating teachers was limited. Six teachers is not a great quantity from which to draw comprehensive conclusions as to the faults of a validated and reliable instrument like the CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008). However, as a qualitative study, the goal was not to seek generalizability, but rather to explore the narratives of Head Start teachers in depth and in a manner that, it is hoped, illuminated their individual and collective stories and histories, those which may defiantly stand against the curated narrative of what a Head Start teacher is and does, can be and will do. It would be important moving forward to speak to ever-increasing numbers of Head Start teachers to reveal their stories and histories with regard to their ability to flex their authentic selves in spite of the necessary CLASS (Pianta et al., 2008) measure.

As well, this study was limited in that there was no opportunity to visit classrooms as an observer to the daily workings of teachers and children doing school. Regrettably, the COVID-19 pandemic did not allow for the Head Start classrooms of this investigation to remain fully open and in-person, let alone to welcome outside observers. It would be important, however, in the future to provide anecdotes that reflect the ways that teachers, both, reveal and conceal their authentic selves. Additionally, there were no validated measures of COVID included at the time of this study.

Despite these limitations, the study adds to the literature by centering teacher voices, offering these six Head Start teachers one outlet by which they explained to an interested researcher exactly that which they have endured, and exactly what they need in order to continue to abate stress and promote well-being. The Great Resignation is real (Sull et al., 2022) with teachers bearing a heavy burden (Goldhaber & Theobald, 2022). As such, this study also challenges the status quo of quality measures in an effort to reveal the nuance that must be accounted for when considering these instruments. It cannot stand that teachers, understanding the importance of emotion, are made to perform for the sake of mandated curriculum or quality ratings. Perhaps most importantly, this study provides policy makers and early childhood education stakeholders data which can be used to advocate for ECE teachers, their lived experiences at the helm of classrooms designed to be vehicles of opportunity for the advancement of children labeled as at risk for school failure. Why should it be the case that we continue to declare more school and school earlier as panaceas when in reality these classrooms may be toxic for educators and likely so for children? More qualitative and mixed-methods research is needed in this space so that greater perspective is taken into consideration when considering PreKindergarten programming, its teachers and children.

Notes

In the context of the United States, Kindergarten is the first year of typical public school programming, K-12. Although most children in the United States begin Kindergarten at the age of 5 years old, it should be noted there are still states where full-day Kindergarten is not mandatory (e.g., Wyoming). Interestingly, Wyoming also has no state-funded preschool programming in place for children (Friedman-Krauss et al., 2021).

References

Acar, I. H., Torquati, J. C., Garcia, A., & Ren, L. (2018). Examining the roles of parent-child and teacher-child relationships on behavior regulation of children at risk. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 64(2), 248–274. https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.64.2.0248

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1969). Object relations, dependency, and attachment: A theoretical review of the infant-mother relationship. Child Development, 969–1025. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1127008

Anderson, K., & Ritter, G. (2017, May). Disparate use of exclusionary discipline: Evidence on inequities in school discipline from a US state. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 25(49), https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.25.2787

Anyon, J. (1980). Social class and the hidden curriculum of work.Journal of Education,67–92. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42741976

Arzubiaga, A. E., Noguerón, S. C., & Sullivan, A. L. (2009). The education of children in im/migrant families. Review of Research in Education, 33(1), 246–271. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40588124

Bassok, D., Hall, T., Markowitz, A. J., & Doromal, J. B. (2021, August). Teacher turnover in child care: Pre-pandemic evidence from Virginia. The Study of Early Education Through Partnerships. Virginia PDG B-5 Evaluation SEE-Partnerships Report. www.researchconnections.org

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 51(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129836

Bergin, C., & Bergin, D. (2009). Attachment in the classroom. Educational Psychology Review, 21(2), 141–170. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-009-9104-0

Bigras, N., Lemay, L., Lehrer, J., Charron, A., Duval, S., & Robert-Mazaye, C. (2021). Early childhood educators’ perceptions of their emotional state, relationships with parents, challenges, and opportunities during the early stage of the pandemic. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(5), 775–787. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01224-y

Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. (2007). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theory and methods (5th ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

Bondy, E., & Ross, D. D. (2008). The teacher as warm demander. Educational Leadership, 66(1), 54–58.

Bottiani, J. H., Duran, C. A., Pas, E. T., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2019). Teacher stress and burnout in urban middle schools: Associations with job demands, resources, and effective classroom practices. Journal of School Psychology, 77, 36–51. doi.10.1016/j.jsp.2019.10.002

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (2011). Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reform and the contradictions of economic life. Haymarket.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Duncan, G. J. (1997). The effects of poverty on children. The Future of Children, 7(2), Children and poverty (Summer-Autumn) (pp. 55–71). Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/1602387

Brooks-Gunn, J., Schneider, W., & Waldfogel, J. (2013). The Great Recession and the risk for child maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 37(10), 721–729. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.08.004

Brophy, J. E., & Good, T. L. (1974). Teacher-student relationships: Causes and consequences. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Buettner, C. K., Jeon, L., Hur, E., & Garcia, R. E. (2016). Teachers’ social-emotional capacity: Factors associated with teachers’ responsiveness and professional commitment. Early Education and Development, 27(7), 1018–1039. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2016.1168227

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), 545–547.

Chen, S., & Phillips, B. (2018). Exploring teacher factors that influence teacher-child relationships in Head Start: A grounded theory. The Qualitative Report, 23(1), 80–97. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715.2018.2962

Colby, S. L., & Ortman, J. M. (2015). Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060. Population Estimates and Projections: Current Population Reports (pp. P25-1143). U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/

Conger, R. D., & Conger, K. J. (2008). Understanding the processes through which economic hardship influences families and children. In D. R. Crane, & T. B. Heaton (Eds.), Handbook of families and poverty (pp. 64–81). Sage

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage

Curbow, B., Spratt, K., Ungaretti, A., McDonnell, K., & Breckler, S. (2000). Development of the Child Care Worker Job Stress inventory. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15(4), 515–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2006(01)00068-0

Darling-Hammond, L. (2001). The challenge of staffing our schools. Educational Leadership, 58(8), 12–17.

Deery-Schmitt, D. M., & Todd, C. M. (1995). A conceptual model for studying turnover among family child care providers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 10(1), 121–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/0885-2006(95.) 90029–2

Denzin, N. K. (1978). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. Transaction.

Dias, M. J., Almodóvar, M., Atiles, J. T., Vargas, A. C., & Zúñiga León, I. M. (2020). Rising to the challenge: Innovative early childhood teachers adapt to the COVID-19 era. Childhood Education, 96(6), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2020.1846385

Driscoll, K. C., Wang, L., Mashburn, A. J., & Pianta, R. C. (2011). Fostering supportive teacher–child relationships: Intervention implementation in a state-funded preschool program. Early Education and Development, 22(4), 593–619. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/104092n89.2010.502015

Dodge, D. T. (1988). The creative curriculum for early childhood. Teaching Strategies.

Dodge, D. T., Colker, L. J., Heroman, C., & Bickart, T. S. (2002). The creative curriculum for preschool. Teaching Strategies.

Enriquez, M., Remy, L., & Dickson, E. (2021). Two years in: The COVID-19 pandemic and Hispanic health. Hispanic Health Care International, 19(4), 210–211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/15404153211045658

Falicov, C. J. (1999). Latino families in therapy: A guide to multicultural practice. Libra.

Ferri, B. A., & Connor, D. J. (2010). ‘I was the special ed. girl’: Urban working-class young women of colour. Gender and Education, 22(1), 105–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250802612688

Fontana, A., & Frey, J. H. (2005). The interview: From neutral stance to political involvement. In N. Denzin & Lincoln, Y. (Ed.). Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials (3rd ed.) (pp.115–160). Sage.

Friedman-Krauss, A. H., Barnett, W. S., Garver, K. A., Hodges, K. S., Weisenfeld, G. G., & Gardiner, B. A. (2021). The state of preschool 2020: State preschool yearbook. National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER).

Gagnon, S. G., Huelsman, T. J., Kidder-Ashley, P., & Lewis, A. (2019). Preschool student-teacher relationships and teaching stress. Early Childhood Education Journal, 47(2), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s106430018-0920-z

Galindo, C. L. (2021). Taking an equity lens: Reconceptualizing research on Latinx students’ schooling experiences and educational outcomes. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 696(1), 106–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162211043770

Garner, P. W., Bolt, E., & Roth, A. N. (2019). Emotion-focused curricula models and expressions of and talk about emotions between teachers and young children. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 33(2), 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2019.1577772

Gilliam, W. S., & Shahar, G. (2006). Preschool and child care expulsion and suspension: Rates and predictors in one state. Infants and Young Children, 19(3), 228–245. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001163-200607000-00007

Gordon, R. A., & Peng, F. (2020). Evidence regarding the domains of the CLASS PreK in Head Start classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.01.008

Goldhaber, D., & Theobald, R. (2022). Teacher attrition and mobility in the pandemic. Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research.

Guerrero-Rosada, P., Weiland, C., McCormick, M., Hsueh, J., Sachs, J., Snow, C., & Maier, M. (2021). Null relations between CLASS scores and gains in children’s language, math, and executive function skills: A replication and extension study. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 54, 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.202007.009

Guglielmi, R. S., & Tatrow, K. (1998). Occupational stress, burnout, and health in teachers: A methodological and theoretical analysis. Review of Educational Research, 68(1), 61–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170690

Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2005). Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development, 76(5), 949–967. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00889.x

Harmsen, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Maulana, R., & Van Veen, K. (2018). The relationship between beginning teachers’ stress causes, stress responses, teaching behaviour and attrition. Teachers and Teaching, 24(6), 626–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2018.1465404

Heckman, J. J., & Karapakula, G. (2019). The Perry Preschoolers at late midlife: A study in design-specific inference (No. w25888). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Herman, E. R., Breedlove, M. L., & Lang, S. N. (2021). December). Family child care support and implementation: Current challenges and strategies from the perspectives of providers. Child & Youth Care Forum, 50(6), 1037–1062. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09613-5

Hiilamo, A., Hiilamo, H., Ristikari, T., & Virtanen, P. (2021). Impact of the Great Recession on mental health, substance use and violence in families with children: A systematic review of the evidence. Children and Youth Services Review, 121, 105772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105772

Hills, P. J., Dickinson, D., Daniels, L. M., Boobyer, C. A., & Burton, R. (2019). Being observed caused physiological stress leading to poorer face recognition. Acta Psychologica, 196, 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2019.04.012

Horvat, E. (2013). Making sense of what you are seeing: Writing and analysis. In E. Horvat (Ed.), The beginner’s guide to doing qualitative research (pp. 105–125). Teachers College Press.

Howard, T. C., & Rodriguez-Minkoff, A. C. (2017). Culturally relevant pedagogy 20 years later: Progress or pontificating? What have we learned and where do we go? Teachers College Record, 119(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811711900104

Irvine, J. J., & Fraser, J. W. (1998). Warm demanders. Education Week, 17(35), 56–57.

Jennings, P. A. (2019). Teaching in a trauma-sensitive classroom: What educators can do to support students. American Educator, 43(2), 12.

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325693

Jensen, B., Grajeda, S., & Haertel, E. (2018). Measuring cultural dimensions of classroom interactions. Educational Assessment, 23(4), 250–276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10627197.2018.1515010

Jeon, L., Buettner, C. K., & Hur, E. (2016). Preschool teachers’ professional background, process quality, and job attitudes: A person-centered approach. Early Education and Development, 27(4), 551–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2016.1099354

Jones, S. M., Bub, K., & Raver, C. C. (2014). Unpacking the black box of the CSRP intervention: The mediating roles of teacher-child relationship quality and self-regulation. Early Education and Development, 24(7), 1043–1064. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1049289.2013.825188

Jones, J. H., Call, T. A., Wolford, S. N., & McWey, L. M. (2021). Parental stress and child outcomes: The mediating role of family conflict. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(3), 746–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-01904-8

Kim, J. (2020). Learning and teaching online during COVID-19: Experiences of student teachers in an early childhood education practicum. International Journal of Early Childhood, 52(2), 145–158.

Kim, J., Wee, S. J., & Meacham, S. (2021). What is missing in our teacher education practices: A collaborative self-study of teacher educators with children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Studying Teacher Education, 17(1), 22–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-020-00272-6

Kim, L. E., Oxley, L., & Asbury, K. (2022). “My brain feels like a browser with 100 tabs open”: A longitudinal study of teachers’ mental health and well-being during the COVID‐19 pandemic. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1), 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12450

Korstjens, I., & Moser, A. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. European Journal of General Practice, 24(1), 120–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092

Kramarczuk Voulgarides, C., Fergus, E., & King Thorius, K. A. (2017). Pursuing equity: Disproportionality in special education and the reframing of technical solutions to address systemic inequities. Review of Research in Education, 41(1), 61–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X16686947

Krueger, R. A., Casey, M. A., Donner, J., Kirsch, S., & Maack, J. N. (2001). Social analysis: Selected tools and techniques. Social Development Paper, 36. World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/568611468763498929/Social-analysis-selected-tools-and-techniques

Ladson-Billings, G. (2007). From the achievement gap to the education debt: Understanding achievement in U.S. schools. [Address to the Urban Sites Network Conference by Gloria Ladson-Billings] [Speech audio recording]. https://archive.nwp.org/audio/comm/Ladson-Billings_Final_Cut.mp3

Ladson-Billings, G. (2012). Through a glass darkly: The persistence of race in education research and scholarship. Educational Researcher, 41(4), 115–120. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12440743

La Paro, K. M., Pianta, R. C., & Stuhlman, M. (2004). The classroom assessment scoring system: Findings from the prekindergarten year. The Elementary School Journal, 104(5), 409–426. https://www.jstor.org/stable/ 3202821?seq = 1&cid = pdf-reference#references_tab_contents

Lawton, R., Zheng, K., Zheng, D., & Huang, E. (2021). A longitudinal study of convergence between Black and White COVID-19 mortality: A county fixed effects approach. The Lancet Regional Health-Americas, 1, 100011. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2021.100011

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

Lockard, C. B., & Wolf, M. (2012). Employment projections by occupational group, 2010–2020. Monthly Labor Review, 135, 84.

Luttrell, W. (2009). The promise of qualitative research in education. Qualitative educational research: Readings in reflexive methodology and transformative practice (pp. 1–17). Routledge.

Maier, M. F., Hsueh, J., & McCormick, M. (2020). Rethinking classroom quality: What we know and what we are learning. MDRC.

Maier, M. F., McCormick, M. P., Xia, S., Hsueh, J., Weiland, C., Morales, A., & Snow, C. (2022). Content-rich instruction and cognitive demand in PreK: Using systematic observations to predict child gains. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 60, 96–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.12.010

McCormick, K. I., McMullen, M. B., & Lee, M. S. C. (2022). Early childhood professional well-being as a predictor of the risk of turnover in Early Head Start and Head Start settings. Early Education and Development, 33(4), 567–588.

McDoniel, M. E., Townley-Flores, C., Sulik, M. J., & Obradović, J. (2022). Widely used measures of classroom quality are largely unrelated to preschool skill development.Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 59,243–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.12.005

McMullen, M. B., Lee, M. S., McCormick, K. I., & Choi, J. (2020). Early childhood professional well-being as a predictor of the risk of turnover in child care: A matter of quality. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 34(3), 331–345. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2019.1705446

Mersky, J. P., Choi, C., Lee, C. P., & Janczewski, C. E. (2021). Disparities in adverse childhood experiences by race/ethnicity, gender, and economic status: Intersectional analysis of a nationally representative sample. Child Abuse and Neglect, 117, 105066. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105066

Metcalf, S., Marlow, J. A., Rood, C. J., Hilado, M. A., DeRidder, C. A., & Quas, J. A. (2022). Identification and incidence of child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology Public Policy and Law, 28(2), 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000352

Michael-Luna, S., & Heimer, L. (2009, April). Early childhood English language learners: Unpacking the dominant discourse of commonly used UPK Curriculum. Paper presented at annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA.

Michael-Luna, S., & Heimer, L. G. (2012). Creative curriculum and highscope curriculum: Constructing possibilities in early education. Curriculum in early childhood education (pp. 133–145). Routledge.

Moffett, L., Weissman, A., Weiland, C., McCormick, M., Hsueh, J., Snow, C., & Sachs, J. (2021). Unpacking pre-K classroom organization: Types, variation, and links to school readiness gains. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 77, 101346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2021.101346

Montgomery, C., & Rupp, A. A. (2005). A meta-analysis for exploring the diverse causes and effects of stress in teachers. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue canadienne de l’éducation, 28(3), 458–486. https://doi.org/10.2307/4126479

Morgan, D. L. (1996). Focus groups as qualitative research (16 vol.). Sage.

Osei-Twumasi, O., & Pinetta, B. J. (2019). Quality of classroom interactions and the demographic divide: Evidence from the measures of effective teaching study. Urban Educationhttps://doi.org/10.1177/0042085919893744

Pakarinen, E., Lerkkanen, M. K., Viljaranta, J., & von Suchodoletz, A. (2021). Investigating bidirectional links between the quality of teacher-child relationships and children’s interest and pre-academic skills in literacy and math. Child Development, 92(1), 388–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13431

Phillips, D., Austin, L. J., & Whitebook, M. (2016). The early care and education workforce. The Future of Children, 26(2), 139–158. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43930585

Phillips, D. A., Hutchison, J., Martin, A., Castle, S., Johnson, A. D., Tulsa, S. E. E. D., & Study Team. (2022). First do no harm: How teachers support or undermine children’s self-regulation. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 59, 172–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.12.001

Phillips, E. N., & Gichiru, W. (2021). Structural violence of schooling: A genealogy of a critical family history of three generations of African American women in a rural community in Florida. Genealogy, 5(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5010020

Pianta, R. C. (1999). Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. American Psychological Association.

Pianta, R. C. (2003). Standardized classroom observations from pre-K to third grade: A mechanism for improving quality classroom experiences during the P-3 years. University of Virginia, Curry School of Education.

Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B., & Stuhlman, M. (2003). Relationships between teachers and children. In W. M. Reynolds, & G. E. Miller (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychology (7 vol., pp. 199–234). Wiley.

Pianta, R. C., Paro, L., K. M., & Hamre, B. K. (2008). Classroom Assessment Scoring System™: Manual K-3. Paul H. Brookes.

Pianta, R. C., & Walsh, D. (1996). High-risk children in schools: Constructing sustaining relationships. Routledge.

Pinar, W. F. (2012). What is curriculum theory? (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Raver, C. C., Jones, S. M., Li-Grining, C., Metzger, M., Smallwood, K., & Sardin, L. (2008). Improving preschool classroom processes: Preliminary findings from a randomized trial implemented in Head Start settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(1), 10–26. doi:10/1016/j.ecresq.2007.09.001

Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford University Press.

Rojas, N. M., & Abenavoli, R. M. (2021). Preschool teacher-child relationships and children’s expressive vocabulary skills: The potential mediating role of profiles of children’s engagement in the classroom. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 56, 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.04.005

Sandilos, L. E., Goble, P., Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., & Pianta, R. C. (2018). Does professional development reduce the influence of teacher stress on teacher-child interactions in pre-kindergarten classrooms? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 42, 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.10.009

Schiller, P. A. (n.d.) A Quantum Leap: Frog Street Pre-K and Improving Head Start School Readiness to Sustain Program Effectiveness.

Seidman, I. E. (2013). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences (4th ed.). Teachers College Press.

Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., Siegel, B. S., Dobbins, M. I., Earls, M. F., & McGuinn, L. (2012). & Wood, D. L. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress.Pediatrics, 129(1),e232-e246. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3048

Souto-Manning, M. (2013). Multicultural teaching in the early childhood classroom: Approaches, strategies, and tools, preschool-2nd grade. Teachers College Press.

Souto-Manning, M., & Melvin, S. A. (2022). Early childhood teachers of color in New York City: Heightened stress, lower quality of life, declining health, and compromised sleep amidst COVID-19. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 60, 34–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcresq.2021.11.005

Spradley, J. P. (1979). The ethnographic interview. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Steed, E. A., & Leech, N. (2021). Shifting to remote learning during COVID-19: Differences for early childhood and early childhood special education teachers. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(5), 789–798. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01218-w

Styck, K. M., Anthony, C. J., Sandilos, L. E., & DiPerna, J. C. (2021). Examining rater effects on the Classroom Assessment Scoring System. Child Development, 92(3), 976–993. doi:10.111/cdev.13460

Sull, D., Sull, C., & Zweig, B. (2022). Toxic culture is driving the Great Resignation. MIT Sloan Management Review, 63(2), 1–9.

Szente, J. (2020). Live virtual sessions with toddlers and preschoolers amid COVID-19: Implications for early childhood teacher education. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 373–380

Ulke, C., Fleischer, T., Muehlan, H., Altweck, L., Hahm, S., Glaesmer, H., & Speerforck, S. (2021). Socio-political context as determinant of childhood maltreatment: A population-based study among women and men in East and West Germany. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 30, e72, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000585

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Head Start Program facts fiscal year 2019. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/no-search/hs-program-fact-sheet-2019.pdf

U.S. Department of Labor. BLS Data Viewer (retrieved July 29, 2022). Available online: https://beta.bls.gov/dataViewer/view/timeseries/CES6562440001

Varghese, C., Vernon-Feagans, L., & Bratsch-Hines, M. (2019). Associations between teacher-child relationships, children’s literacy achievement, and social competencies for struggling and non-struggling readers in early elementary school. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.09.005

von Haaren-Mack, B., Schaefer, A., Pels, F., & Kleinert, J. (2020). Stress in physical education teachers: A systematic review of sources, consequences, and moderators of stress. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 91(2), 279–297. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2019.1662878

Walsh, D., McCartney, G., Smith, M., & Armour, G. (2019). Relationship between childhood socioeconomic position and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 73(12), 1087–1093. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2019-212738

Wang, M. T., Degol, J. L., Amemiya, J., Parr, A., & Guo, J. (2020). Classroom climate and children’s academic and psychological wellbeing: A systematic review and meta-analysis.Developmental Review, 57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2020.100912

Ward, K. P., & Lee, S. J. (2020). Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress, responsiveness, and child wellbeing among low-income families. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020. 105218

Ware, F. (2006). Warm demander pedagogy: Culturally responsive teaching that supports a culture of achievement for African American students. Urban Education, 41(4), 427–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085906289710

Watts, T. W., Gandhi, J., Ibrahim, D. A., Masucci, M. D., & Raver, C. C. (2018). The Chicago School Readiness Project: Examining the long-term impacts of an early childhood intervention. PloS One, 13(7), doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200144

Weiland, C., & Guerrero-Rosada, P. (2022). Widely used measures of Pre-K classroom quality: What we know, gaps in the field, and promising new directions. [Policy Brief]. MDRC. https://www.mdrc.org/

Whitebook, M., Phillips, D., & Howes, C. (2014). Worthy work, STILL unlivable wages: The early childhood workforce 25 years after the National Child Care Staffing Study. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment.

Wong, J. Y. H., Wai, A. K. C., Wang, M. P., Lee, J. J., Li, M., Kwok, J. Y. Y., & Choi, A. W. M. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on child maltreatment: Income instability and parenting issues. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1501. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041501