Abstract

Teachers’ social-emotional competence has received increasing attention in educational psychology for about a decade and has been suggested to be an important prerequisite for the quality of teacher-student interactions and student outcomes. In this review, we will summarize the current state of knowledge about the association between one central component of teachers’ social-emotional competence—their empathy—with these indicators of teaching effectiveness. After all, empathy appears to be a particularly promising determinant for explaining high-quality teacher-student interactions, especially emotional support for students and, in turn, positive student development from a theoretical perspective. A systematic literature research yielded 41 records relevant for our article. Results indicated that teachers reporting more empathy with victims of bullying in hypothetical scenarios indicated a greater likelihood to intervene. However, there was neither consistent evidence for a relationship between teachers’ empathy and the degree to which they supported students emotionally in general, nor with classroom management, instructional support, or student outcomes. Notably, most studies asked teachers for a self-evaluation of their empathy, whereas assessments based on objective criteria were underrepresented. We discuss how these methodological decisions limit the conclusions we can draw from prior studies and outline perspective for future research in teachers’ empathy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Students experience a range of emotions—such as enjoyment, anxiety, and boredom—while they attain new knowledge, take exams, or strive to connect with their classmates (Ahmed et al., 2010; Hascher, 2008; Martin & Huebner, 2007; Pekrun et al., 2002). Teachers are confronted with these emotions in the classroom and beyond, and their ability to read their students’ emotional signals and attend to them sensitively is vital to form positive teacher-student relationships (Pianta, 1999). Therefore, teachers’ social-emotional characteristics have been suggested as essential for the quality of teacher-student interactions and, in turn, students’ psychosocial outcomes (Brackett & Katulak, 2007; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009; Rimm-Kaufman & Hamre, 2010). Empathy is one component of teachers’ social-emotional characteristics that appears particularly relevant for the quality of teacher-student interactions from a theoretical perspective. First, empathy is considered as the origin of human’s prosocial behavior (Preston & de Waal, 2002). Second, in contrast to social-emotional characteristics such as emotional self-awareness or emotion regulation, empathy explicitly refers to other people rather than to the self, more specifically, to the ability to perceive and understand students’ emotions and needs (Zins et al., 2004).

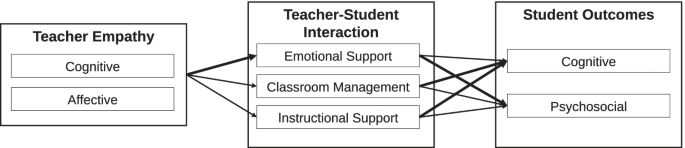

Because of these theoretical arguments and a recent increase in empirical studies on this topic, the goal of this article is to review prior research investigating the relationship of teachers’ empathy with the quality of teacher-student interactions and, in turn, with student outcomes (see heuristic working model in Figure 1). We use effective teaching here as an umbrella term to refer to both interaction quality and student outcomes. Summarizing the current level of knowledge on this topic appears particularly useful for the following reasons. First, various meanings have been attached to the term empathy, and the diversity of concepts that have been used to refer to concepts closely related to empathy (e.g., emotional intelligence, perspective taking, and emotion recognition; also see Batson, 2009; Olderbak & Wilhelm, 2020) make it difficult to oversee prior research at first glance. Second, the research field has rapidly grown throughout the last decade. Thus, to understand foci of prior research and widely neglected questions is important; for example, the review will uncover possible specific underrepresented student outcomes (e.g., cognitive vs. psychosocial). Third, researchers have applied different methodological approaches. For example, self-report scales and objective tests are available and it is debatable whether both are equally valid considering the risk of self-serving bias in questionnaires (Brackett et al., 2006). Against this background, it is important to summarize not only the results from prior studies but also the assessment methods they applied to inform future studies in terms of which methodological approaches are best suited to obtain valid results.

A General Theoretical Perspective on Empathy

Historically, two distinct lines of research have evolved around empathy (for an overview see, e.g., Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004; Davis, 1983). First, from the affective perspective, empathy describes the emotional reactions to another person’s affective experiences. According to Eisenberg and Miller (1987), this means that one experiences the same emotion as the other person. Hatfield et al. (1993) described the phenomenon of “catching” other people’s emotions as emotional contagion. Affective empathy can elicit both positive and negative emotions, and because emotions are multi-componential, the subjective feelings, thoughts, expressions, and physiological and behavioral reactions can differ depending on the type of emotion (Olderbak et al., 2014; Scherer, 1984). Empathy from the affective perspective can also mean to feel something that is appropriate but not identical with the other person’s emotion, for instance, responding with concern and sympathy to another person’s sadness (e.g., Batson et al., 2002).

Second, from the cognitive perspective, empathy reflects a person’s ability to understand how other people feel by taking their perspective and reading their nonverbal signals (e.g., Wispé, 1986). Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright (2004) pointed out that theory of mind largely converges with the cognitive definition of empathy. Furthermore, models of emotional intelligence, such as the four-branch-model (Mayer & Salovey, 1997), include qualities resembling empathy as defined in the cognitive perspective: the ability to perceive emotions in other people’s faces accurately and to understand emotions, that is, knowing when specific emotions are likely to arise.

In accordance with Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright (2004), we define empathy as including both affective and cognitive components (for similar approaches, also see Davis, 1983; Decety & Jackson, 2004; Preston & de Waal, 2002). This allows for a more comprehensive understanding of empathy and its consequences because the affective component of empathy explains why we care for other people in need and are motivated to react sensitively, whereas the cognitive component explains what enables people to know and name the feelings of others (Batson, 2009). Preston and de Waal (2002) also support the idea that cognitive and affective empathy are entangled and complement each other in explaining prosocial behavior. They suggest that the development of cognitive empathy promotes the “effectiveness of empathy by helping the subject to focus on the object, even in its absence, remain emotionally distinct from the object, and determine the best course of action for the object’s needs” (Preston & de Waal, 2002, p. 20).

Considering the central role of empathy in human relationships, which has also been supported empirically (Eisenberg & Miller, 1987; Kardos et al., 2017; Mitsopoulou & Giovazolias, 2015; Sened et al., 2017; Vachon et al., 2014), its importance in social occupations has been recognized for a long time. For instance, Rogers (1959) proposed that the therapists’ ability to accurately perceive their clients’ point of view will facilitate the therapeutic process and, in turn, produce change in personality and behavior. In line with this assumption, studies with psychotherapists and also with physicians showed that their empathy predicted their patients’ satisfaction and clinical outcomes (Elliott et al., 2018; Hojat et al., 2011). Like psychotherapists or physicians and their clients, teachers are in close interpersonal contact with their students. Hence, it seems plausible to assume a central role of empathy in their professional lives as well.

The Role of Teacher Empathy

Caring for students and establishing positive teacher-student relationships are a central part of teachers’ professional roles (Butler, 2012; O’Connor, 2008; Watt et al., 2021). Furthermore, providing high levels of emotional support as indicated by a positive emotional tone in the classroom, sensitive responses to students’ emotional, social, and academic needs, and consideration of their interests is one aspect of high-quality classrooms (Pianta & Hamre, 2009). To achieve this, the ability to read students’ (non-)verbal signals—in others words: empathy—is vital (Pianta, 1999). For instance, teachers’ cognitive empathy will help them better identify from a student’s facial expressions if he or she is sad about a bad grade, angry about an argument with friends, or bored with specific learning activities. Empathic teachers will know that students may feel anxious when confronted with challenging tasks or embarrassed and frustrated when repeatedly unable to answer the teacher’s questions. Having recognized negative affective states in their students, teachers’ affective empathy should motivate them to react sensitively to their students’ emotional needs, provide comfort, and encouragement (Batson, 2009; Weisz et al., 2020). The prosocial classroom model (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009) also integrates these ideas and further states that teachers’ social-emotional competence, of which empathy is one part, should facilitate classroom management.

Effective classroom management means that teachers establish rules and order, apply appropriate strategies to prevent student behavior problems, and maximize time on task (Emmer & Stough, 2001). The ability to understand reasons for classroom disturbances could facilitate behavior management. For example, noticing students’ boredom could initiate teachers to choose a different instructional approach before students start off-task activities (Nett et al., 2010). Furthermore, taking the perspective of adolescents, teachers will be able to recognize their need for autonomy, which would collide with a controlling classroom management strategy (Aelterman et al., 2019; Eccles & Midgley, 1989). Yet, effective classroom management may be less dependent on teacher empathy than emotional support is. After all, classroom management includes several facets that go beyond empathy, for example, productive use of time and establishment of rules. For these tasks, specific classroom management knowledges is a key prerequisite (Kunter et al., 2013; Shulman, 1986).

Finally, even though not mentioned in the prosocial classroom model, teacher empathy could also play a role in instructional support, which is the third key aspect of high-quality teacher-student interaction in addition to emotional support and classroom management (Klieme et al., 2009; Pianta & Hamre, 2009). Instructional support comprises clear and engaging instruction that promotes content understanding and presents cognitive challenges. In addition, teachers scaffold learning by providing feedback and initiating content-related class discussions (Pianta et al., 2012). To adapt instruction to students’ learning needs and design engaging lessons, it is necessary to recognize when students struggle understanding content and which activities they find particularly interesting or boring (Bieg et al., 2017; Parsons et al., 2018). However, in addition instructional support requires high levels of (pedagogical) content knowledge so again one could assume that empathy plays a less central role than it does for emotional support (Kunter et al., 2013; Shulman, 1986).

In summary, from a theoretical perspective, a relationship between teachers’ empathy and the quality of teacher-student interactions, in particular with emotional support, appears plausible. By increasing interaction quality, empathy should also indirectly promote student development. Here, we distinguish between cognitive development, that is, outcomes related to students’ learning of subject matter, and psychosocial development, that is, motivational, emotional, and social variables. Prior research consistently shows that emotional support is positively associated with psychosocial outcomes, such as academic interest, self-concept, peer relatedness, and behavioral engagement, whereas classroom management and instructional support are most closely related to student achievement (Aldrup et al., 2018; Downer et al., 2014; Fauth et al., 2014b; Kunter et al., 2013; Nie & Lau, 2009; Ruzek et al., 2016; Scherer et al., 2016; Wagner et al., 2016; Yildirim, 2012). Our heuristic working model in Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesized associations between teacher empathy, the quality of teacher-student interactions, and student outcomes. To test these theoretical assumptions, different methodological approaches are available, which we will explain next.

Assessment Approaches in Researching Teacher Empathy

Researchers interested in investigating teacher empathy can choose between different measurement approaches that are distinct in terms of two key dimensions: objective assessment versus self-report questionnaires and general versus profession-specific tools. On the one hand, researchers can apply objective assessments such as the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT; Mayer et al., 2002). The MSCEIT comprises subtests measuring a person’s ability to perceive and understand emotions in others. For example, participants see pictures of faces and are requested to select the degree to which it expresses each of five emotions. On the other hand, several self-report questionnaires are available. One prominent scale is the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (Davis, 1980) including subscales on empathic concern (“I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me.”) and perspective taking (“I sometimes try to understand my friends better by imagining how things look from their perspective.”). Emotional intelligence questionnaires typically include subscales on empathy as well. For example, the other-emotion appraisal subscale of the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (Wong & Law, 2002) assesses the ability to perceive emotions in others (“I am sensitive to the feelings and emotions of others.”).

However, it is unclear if people can validly evaluate their own empathy and especially regarding the cognitive component, which consists of knowledge and skills, a performance-based approach seems more valid. In line with these concerns, Ickes (2001) concluded that performance-based measures of empathic accuracy predict performance in social situations whereas self-report measures do not. Likewise, Brackett et al. (2006) found no association between undergraduate students’ self-reported emotional intelligence and the extent to which others perceived them as friendly and socially engaged but using an emotional intelligence test yielded statistically significant associations. Self-serving bias could be one issue reducing the validity of people’s self-reported empathy. For teachers, in particular, exaggerating their empathy appears likely because establishing close, caring connections with students is an important aspect of their professional identities (O’Connor, 2008; Wubbels et al., 1993). Finally, the use of self-report questionnaires not only poses the risk of reduced correlations due to validity issues but also of inflated correlations due to common method bias when participants report on their empathy and the dependent variables at the same time (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Thus, whether researchers use an objective empathy assessment or a self-report questionnaire can largely affect the results and the degree to which the findings allow for valid conclusion.

In addition, researchers in teacher empathy have to decide on the context-specificity of their instrument. On the one hand, they can use one of the tools described above that were designed for use in the general population. On the other hand, they can choose profession-specific instruments asking teachers about their empathy for students. A profession-specific assessment has several advantages. Generally, performance in specific contexts is best predicted by variables that refer to the same context (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977; Weinert, 2001). Furthermore, in contrast to day-to-day interactions with other social partners, teacher-student interactions are unique and characterized by an asymmetric nature (Pianta, 1999). Teachers and students differ substantially in terms of their knowledge and experiences and this lack of similarity may impede empathy (Preston & de Waal, 2002). Accordingly, teachers likely require profession-specific knowledge about their students’ developmental needs and concerns to facilitate empathy (Eccles & Midgley, 1989; Voss et al., 2011).

Present Study

The present study provides a systematic review of prior empirical research on the role of teachers’ empathy in effective teaching, which comprises the quality of teacher-student interactions and student development. The relevance of teachers’ empathy and related qualities has been highlighted from a theoretical perspective for over a decade (e.g., Brackett & Katulak, 2007; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009; Rimm-Kaufman & Hamre, 2010). Therefore, our goal was to gather what we have learned so far and whether the empirical evidence is in line with the theoretical claim that teacher empathy is positively associated with effective teaching. Furthermore, we aimed to identify questions that have remained unanswered to date in prior research on the association between teacher empathy and the quality of teacher-student interactions and student outcomes. For instance, reviewing the literature enabled us to carve out consequences of empathy that have been underrepresented in prior research (e.g., specific domains of teacher-student interaction quality or specific student outcomes) or methodological challenges that still need to be solved for ensuring the validity of results. From our perspective, this is an important step to research that can eventually support teachers, teacher educators, school psychologists, principals, and other stakeholders in the education system in evaluating the benefits of promoting teacher empathy.

The heuristic working model (Fig. 1), which is largely based on the prosocial classroom model (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009), illustrates the hypothesized role of teachers’ empathy in the quality of teacher-student interactions and student outcomes. As outlined above, we expected to find a positive relationship between teachers’ empathy and the quality of teacher-student interactions, in particular, with emotional support. After all, empathy allows teachers to understand students’ perspectives, read their nonverbal signals, and react with concern to students needing help—these qualities are all indicators of emotional support (Pianta et al., 2012). In turn, by promoting high-quality teacher-student interactions, teachers’ empathy can be assumed to foster student development. However, because student outcomes are more distal to teachers’ empathy than teacher-student interactions are, we expected less pronounced associations. Furthermore, because we speculated that empathy plays a role especially in teachers’ emotional support and because prior research revealed more consistent association between emotional support and psychosocial rather than cognitive student outcomes (e.g., Fauth et al., 2014b; Kunter et al., 2013), we hypothesized that empathy would have the weakest relationship with student achievement.

Moreover, we speculated that methodological decisions could affect the magnitude of the relationships between teachers’ empathy, the quality of teacher-student interactions, and student outcomes. Thus, our first goal was to determine which methodological approaches have been applied in the field and consider them in reviewing the results from prior work. Based on the principle of correspondence, we expected particularly close associations when a profession-specific rather than a general assessment tool was used to measure teachers’ empathy (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977). In addition, we hypothesized that the reliance on self-report measures to assess empathy and its consequences leads to larger correlations because of common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Method

Literature Search

We conducted our literature search in PsycINFO and Web of Science in October 2020 without date restrictions. To identify relevant articles on teachers’ empathy we used the following search terms: empathy OR “perspective taking” OR compassion OR “emotion* intelligence” OR “emotion* knowledge” OR “emotion* awareness” OR “emotion* understanding” OR “emotion* accuracy” OR “emotion* perception” OR “emotion* detection” OR “emotion* identification” OR “emotion* recognition” OR “teacher* sensitivity”. Using a broad set of search terms allowed us to capture constructs which show substantial conceptual overlap with empathy and are frequently discussed in independent strands of research using different terminology (Mayer et al., 2008; Olderbak & Wilhelm, 2020).

In PsycINFO, among others titles, abstracts, heading words, tables of contents, and key concepts were searched for the defined terms. We conducted a thesaurus search using the exp Teachers/ command to limit results to teacher samples. Furthermore, we limited our search to quantitative studies using the quantitative study.md command. In Web of Science, the defined terms were searched in titles, abstracts, and keywords. To limit results to teacher samples, we entered our central search terms in combination with teacher* / professor* / educator* / lecturer* / faculty*. We applied the NEAR/3 command, which identifies studies mentioning two terms close to one another (in our case, three words or less in between empathy and teacher synonyms) in any order. Moreover, we excluded the following publication types: meeting abstracts, reviews, book reviews, editorial material, letters, and biographical items. In both databases, we excluded studies written in a language not based on the Latin alphabet (e.g., Chinese, Hebrew). For studies not written in English, we used Google Translate to retrieve the necessary information. This yielded 533 records from PsycINFO and 474 records from Web of Science, resulting in 931 records in total after removing duplicates.

We pursued two strategies to supplement our database search and to identify relevant articles we may have missed. First, we screened the reference list of all studies identified as eligible for our synthesis after evaluating the full-text. Second, we conducted a Google Scholar search in December 2020 to find articles citing the studies we had identified as relevant. These strategies produced 134 additional records.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included studies in our research synthesis if they met the following criteria. First, empathy had to be measured in accordance with our definition of empathy. For instance, we neither included studies measuring empathy in rather broad terms (e.g., teacher sensitivity assessed with the Classroom Assessment Scoring System; Pianta et al., 2012) nor did we code effects pertaining to fantasy and personal distress. Fantasy and personal distress are subscales of the frequently used Interpersonal Reactivity Index (Davis, 1980). However, Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright (2004) argued that these scales do not measure empathy. For example, the personal distress scale only partly refers to interpersonal situations (e.g., “In emergency situations, I feel apprehensive and ill-at-ease.”). Second, studies had to measure an outcome relevant to our article, that is, aspects of teacher-student interaction or student outcomes. Third, it was necessary to report the statistical significance of bivariate correlations or another statistic convertible to a bivariate correlation. However, we retained studies that reported that an effect was not statistically significant without providing the exact size of the effect. Fourth, results had to be based on a sample of at least ten teachers. Regular and special education teachers of all grade levels were included (i.e., preschool to tertiary education). Importantly, even though teachers demonstrate different behaviors to realize high-quality teacher-student interactions, the three overarching domains of emotional support, classroom management, and instructional support remain relevant from preschool to tertiary education, making the inclusion of a broad range of education levels possible (Langenbach & Aagaard, 1990; Pianta & Hamre, 2009; Schneider & Preckel, 2017). Fifth, we only retained the study that provided the most information if multiple articles were based on the same sample and variables.

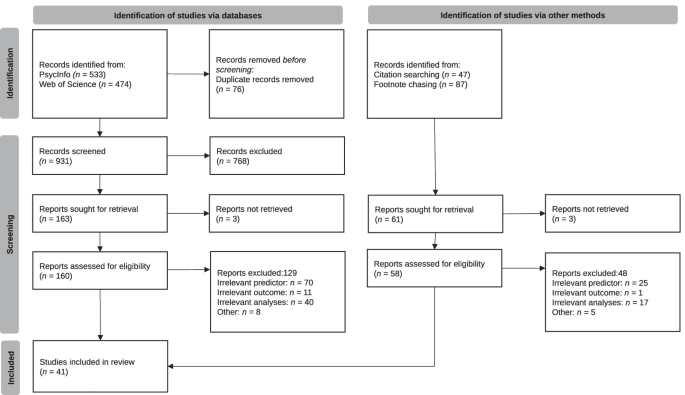

Based on these criteria and as illustrated in the PRISMA diagram (Page et al., 2021) in Figure 2, 768 records were excluded after pre-screening the abstracts of the 931 records obtained through database searching. Pre-screening the abstracts of the 134 records from citation searching and footnote chasing left 61 potentially relevant records. In total, we could not retrieve a full text for six records. Thus, we proceeded screening the full-texts of the remaining 160 records from database searching and 58 records from citation searching and footnote chasing for eligibility. These steps were conducted by the first author, and in addition, the second author read 25% of the records to verify the inter-rater reliability. Cohen’s κ was .81, and we agreed in 98% of the articles regarding the questions of whether none versus any of the exclusion criteria were met. Considering reasons for exclusion via the multiple search strategies jointly, twelve did not include a relevant outcome and 13 were excluded for other reasons (e.g., eight articles did not present quantitative results and one article was based on a duplicate sample). In contrast, a comparably large number of 95 articles did not include a relevant predictor. Most often, this was due to emotional intelligence instruments not including empathy-related subscales (e.g., Trait Meta-Mood Scale, Salovey et al., 1995; Emotional Quotient Inventory: Short Form; Bar-On, 2002). Similarly, we would have needed to exclude 58 articles because they assessed relevant variables but did not report bivariate correlations or other statistics to estimate the relationship of teacher empathy with the quality of teacher-student relationships and student outcomes. Most often these studies used an emotional intelligence instrument including empathy-related subscales (e.g., Trait Emotional Intelligence Qustionnaire, Petrides & Furnham, 2003; MSCEIT, Mayer et al., 2002), but the analyses were conducted based on the total emotional intelligence scores. Due to the large number of studies that were relevant for our synthesis but that did not report the necessary statistics, we decided to contact the authors and ask for the correlation coefficients if we considered the study particularly informative for our research questions (i.e., the independent or dependent variable was measured with instruments going beyond teacher self-report). We contacted 15 authors, six responded, and one was able to provide the information we requested. Thus, 57 articles were excluded because no relevant analyses were available. Finally, 31 articles remained after full-text reading and citation searching and footnote chasing yielded ten additional records.

Processing of Search Results

For the final set of records, we extracted information on the authors, the year and type of publication, and the sample (i.e., sample size, teachers’ gender, age, and years of job experience, school level, and country). Regarding our independent variable, teacher empathy, we retrieved information on (1) the components of empathy (i.e., affective, cognitive, composite); (2) the instrument; (3) whether a teacher self-report questionnaire, an objective assessment, or other approaches were used; and (4) whether the instrument took a general, a profession-specific, or a situation-specific perspective. For our dependent variables, teacher-student interactions, and student outcomes, we retrieved information on (1) the components of teacher-student interaction (i.e., emotional support, classroom management, instructional support) and student outcomes (i.e., cognitive, psychosocial) and (2) whether a teacher self-report questionnaire, student questionnaires, student achievement tests, classroom observations, or other measurements were conducted. Again, the first author performed these steps and the second author coded 20% of the records to estimate the inter-rater reliability regarding the coding of the components of empathy and the outcome categories. Both assigned the same category to 89% of the predictor and outcome variables. Finally, we retrieved correlation coefficients and information on statistical significance. To answer our research questions, we primarily relied on vote-counting and determined the number of effects that were statistically significant at α < .05. However, we also wanted to give the reader an impression of the size of the effects. Thus, in the few cases where effect sizes other than correlations were reported, we converted them to allow for between-study comparisons. More specifically, we used the formulas provided by Thalheimer and Cook (2002) to convert F-statistics and t-statistics to Cohen’s d and the formulas provided by Borenstein (2009) to convert odds ratios to Cohen’s d and to convert Cohen’s d to r. In addition, we recoded the correlations between empathy and negative qualities of teacher-student interactions and maladaptive student outcomes to facilitate the interpretation of the correlation coefficients. Thus, positive correlation coefficients can now be interpreted as indicative of effects in line with our heuristic working model (Figure 1). Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4 provide a summary of the reviewed articles organized depending on the methodological approach that was used. The data and the review protocol are available at PsychArchives (Aldrup et al., 2021).

Results

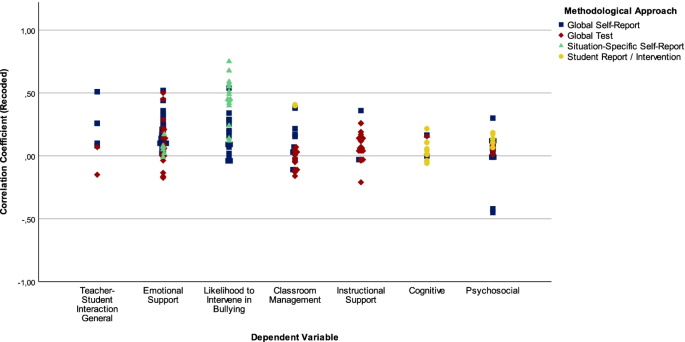

In the following, we will first describe general characteristics of the records included in this article and will then provide details about the methodological approaches used. The main part of this section is dedicated to outlining results from prior research on the relationship of teacher empathy with teacher-student interactions and student outcomes. Table 5 gives a summary of the statistically significant effects and the effect sizes for each dependent variable, and Figure 3 provides an overview of the effect sizes depending on the methodological type of study and the dependent variable.

General Study Characteristics

This research synthesis is based on 23 journal articles, 15 theses, two proceedings papers, and one book chapter, which were published between 2004 and 2020 (Md = 2014, M = 2014, SD = 3.92).The 41 included records reported results from 42 independent samples from 12 different countries—mostly the USA (n = 22), followed by Australia and China (n = 4). The teacher samples comprised between 11 and 467 teachers (M = 119.02, SD = 103.10). On average, the teachers were M = 36.12 years old and 76.8% were female. The majority of studies included only in-service teachers (n = 35), who had M = 9.08 years of job experience on average. Most samples were composed either of only secondary school teachers (n = 16) or a combination of secondary school, elementary school, and, in some cases, early childhood teachers (n = 8). Each five to six samples included exclusively early childhood teachers, elementary school teachers, or educators at the tertiary level. Only 14 studies provided information on the school subject the participants taught: seven samples included teachers from different subject domains, three assessed English, two mathematics, one physical education, and one law teachers.

The majority of studies (93%) reported only cross-sectional analyses regarding the link between teacher empathy and teacher-student interactions or student outcomes. However, Franklin (2014) measured empathy at one time point but included two waves of student outcomes and Aldrup et al., (2020) used longitudinal data across three time points. We only considered the within-wave correlations to make results from these studies comparable to the majority of articles that were cross-sectional. Finally, using a randomized pre-post-control group design, Okonofua et al. (2016) investigated the effects of an empathic mindset intervention.

Aspects of Empathy and Measurement

In most samples, the focus was on the cognitive (n = 28) as opposed to the affective component (n = 8) of empathy. In five samples, both cognitive and affective empathy were assessed and in one sample, a composite measure was used. In terms of measurement instruments, self-report questionnaires were predominant (n = 29 samples/studies). In the following, we will list the self-report tools that were used in more than one study. The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (Davis, 1980) was applied ten times followed by the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (Wong & Law, 2002), which was used four times. Three other studies measured the ability to perceive emotions in others as well, but based on the Self-Rated Emotional Intelligence Scale (Brackett et al., 2006). Three studies used the BarOn Emotional Quotient-Inventory, which measures the ability to understand and respect other people’s feelings (Bar-On, 1997). In contrast to these questionnaires designed for use in the general population, only one study applied a profession-specific instrument asking teachers, for example, “I am happy for students if they enjoy happy moments” (Wu et al., 2019). Likewise, the Bullying Attitudes Questionnaire (Craig et al., 2000; Yoon, 2004), which was employed in seven studies, measures teachers’ self-reported empathic concern for student victims of bullying and is therefore situated in the professional context as well.

Nine studies used approaches based on objective criteria to discriminate between more and less empathic teachers rather than using teacher questionnaires. Four studies employed the MSCEIT (Mayer et al., 2002). Similar tests—the Amsterdam Emotion Recognition Test (van der Schalk et al., 2011), the Situational Test of Emotional Understanding (MacCann & Roberts, 2008), and the Test of Emotional Intelligence (Śmieja et al., 2014)—were each used in one study. Friedman (2014) pursued a slightly different strategy and applied the newly developed Teacher Emotional Intelligence Measure, which asks teachers about their likely response to a hypothetical disciplinary incident in class in an open format. A coding manual is used to determine the teacher’s ability to perceive and understand the disputant’s emotions and to identify how other students in class would feel. Zinsser et al. (2015) conducted teacher focus groups on the role of emotions in classrooms. Based on teachers’ responses to semi-structured questions, trained coders detected the teachers’ emotion knowledge, that is, their ability to recognize and understand emotions in their students. Moreover, two studies asked students to report on their teachers’ empathy (Aldrup et al., 2020; Latchaw, 2017). Thus, like in the studies by Friedman (2014) and Zinsser et al. (2015), the focus was on teachers’ empathy in the professional context and even more specifically in the respective subject domain. Finally, one article including two samples (Okonofua et al., 2016) reported results from an intervention aimed to induce an empathic mindset in their teacher-student interactions. However, the intervention study did not include a treatment check so it remains unknown whether it actually changed teacher empathy.

Effects on Teacher-Student Interactions

We identified 33 studies (34 samples) investigating the role of empathy in teacher-student interactions: 28 studies measured aspects of emotional support, ten measured classroom management, and six measured instructional support. Five studies applied measures of teacher-student interaction that we could not clearly assign to one of the interaction domains.

General Teacher-Student Interaction

Three out of five studies measuring blended aspects of teacher-student interactions found statistically significant associations (57% of the investigated effects were significant and positive; see Table 5). Secondary school teachers who rated their own ability to perceive other’s emotions higher evaluated their teaching performance (r = .26, p < .001) more positively (Wu et al., 2019). In addition, in two studies with English as a foreign language teachers at high schools and private language institutes (Ghanizadeh & Moafian, 2010; Khodadady, 2012), teachers’ self-reported empathy was linked to their students’ ratings of teacher qualification (i.e., knowledge, self-confidence, comprehensibility; r = .10, p < .01) and students’ overall ratings of instruction (r = .26, p < .05). In contrast, Corcoran and Tormey (2013) found no, or even counterintuitive associations of teachers’ test scores in perceiving (r = –.15, p < .01) and understanding emotions (r = .07, p > .05) with student teachers’ practicum performance evaluations, for example, the use of appropriate pedagogic strategies and material or the quality of teacher-student relationships. Petsos and Gorizidis (2019) did not find a relationship between secondary school teachers’ self-reported perception of other’s emotions and the extent to which students felt their teacher assigned students responsibility (r = .08, p > .05).

Emotional Support

The number of studies finding a statistically significantly positive association between teachers’ empathy and their emotional support for students (n = 15) slightly outweighed the number of studies not supporting this link (n = 11) or finding mixed evidence (n = 2). Because a substantial number of studies focused on teachers’ reactions to bullying among students as one specific aspect of emotional support, we will summarize results from this line of research separately after describing the findings for emotional support.

Emotional Support

Six studies found statistically significant positive associations with teachers’ empathy but eleven found mixed or no evidence (25% of the investigated effects were significant and positive, 73% were not significant; see Table 5). Abacioglu et al. (2020) revealed that primary school teachers evaluating their perspective taking more positively reported using more culturally (r = .33, p < .01) and socially sensitive teaching practices (r = .24, p < .01). Similarly, teachers reporting a greater ability to perceive others’ emotions considered their attention to students needs as more pronounced (r = .24, p < .01) (Nizielski et al., 2012). Furthermore, the theses by Gottesman (2016) and Metaxas (2018) showed that teachers reporting more empathy were more likely to choose emotionally supportive strategies in response to a hypothetical student exhibiting challenging behavior (r = .36 and r = .24, p < .01). In these studies, teachers from different grade levels participated spanning pre- to high school. Finally, there were two studies using not only teacher self-report questionnaires and finding a relationship between empathy and emotional support. Khodadady (2012) found that high school students perceived better rapport with their teacher (r = .10, p < .01) and greater teacher fairness (r = .11, p < .01) when teachers reported greater empathy. Moreover, secondary school students reported more positive teacher-student relationships if their teacher attained higher test scores in perceiving (r = .50, p = .02) and understanding emotions (r = .45, p = .04) (Barłożek, 2015). However, neither Khodadady (2012) nor Barłożek (2015) accounted for the nesting of students in classrooms, which is associated with a higher risk of false positive findings (Snijders & Bosker, 2012).

Notably, eleven other studies that were not exclusively using teacher self-report questionnaires provided evidence that was less clear. Hu et al. (2018) assessed preschool teachers’ self-evaluations of their ability to perceive other’s emotions and asked both teachers and external observers to evaluate the quality of emotional support. Emotional perception was statistically significantly related only to teachers’ self-reported emotional support (r = .31, p < .001). Swartz and McElwain (2012) asked pre-service early childhood teachers about their perspective taking and observed their responses to children’s emotional displays. Teachers’ perspective taking was unrelated to their strategies when dealing with positive emotions, but when children displayed anger or sadness, empathic teachers were more likely to show supportive (r = .52, p < .01) rather than non-supportive behavior (r = –.44, p < .05). Friedman (2014) also conducted classroom observations to assess the quality of emotional support. Middle and high school teachers with higher scores in a newly developed emotional intelligence test regarding their awareness, perception, and understanding of students’ emotions did not establish a more positive climate and did not show more sensitivity or regard for students’ perspectives. In addition, preschool teachers demonstrating superior emotion knowledge in a focus group were not observed to show more emotional support in the study by Zinsser et al. (2015). In a similar vein, Heckathorn (2013) did not find a statistically significant positive and even one negative correlation between teachers’ perception and understanding of emotions as assessed with the MSCEIT (Mayer et al., 2002) and the degree to that nontraditional evening graduate adult master’s level students perceived affiliation among learners, opportunities to influence lessons, and teacher support in terms of sensitivity and encouragement. Furthermore, high school teachers’ tests scores in emotion understanding were unrelated to their self-reported quality of teacher-student relationships (O’Shea, 2019) and participation in an empathic mindset intervention did not make middle school students feel more respected by their teacher—however, the intervention had an effect for students with a history of suspension (Okonofua et al., 2016). In the thesis by Fults (2019), there was no association between middle school teachers’ self-reported empathy and students’ perception of proximity and Wen (2020) did not establish a link between college teachers’ self-reported ability to recognize other people’s emotions and student-reported receptivity and liking of the teacher. Likewise, Petsos and Gorizidis (2019) found no statistically significant correlation between junior high school teachers’ self-reported emotion perception of others and students’ perceptions of their teachers’ helpful and friendly behavior and their understanding of students as opposed to displaying dissatisfaction and admonishing students. Finally, middle school teachers reporting greater empathy with victims of bullying or general perspective taking and empathic concern were not more likely to perceive their teacher-student relationship as close and free of conflict (Hammel, 2013; only empathic concern and closeness: r = .27, p < .05). To summarize, teachers who perceived themselves as empathic reported providing more emotional support. However, this impression was rarely evident in students’ and observers’ perspectives. Furthermore, higher test scores in empathy were unrelated to the quality of emotional support.

Likelihood to Intervene in Bullying

Nine of the twelve studies in this strand of research found an effect (62% of the investigated effects were significant and positive; see Table 5). Seven studies, including teachers from preschool to the secondary school level, found that teachers feeling empathic concern for a hypothetical student who was a victim of bullying reported a greater likelihood of intervening in the bullying situation (Byers et al., 2011; Dedousis-Wallace & Shute, 2009; Hines, 2013; Huang et al., 2018; Sokol et al., 2016; VanZoeren, 2015; Yoon, 2004). In these studies, the effect sizes were moderate to large (all rs > .30; see Figure 3). Likewise, teachers’ self-reported general empathic concern, perspective taking, and tendency to experience the feelings of others were positively associated with their likelihood to intervene in bullying from early childhood to college education (Dedousis-Wallace & Shute, 2009; Fifield, 2011; Huang et al., 2018; Singh, 2014). One exception of this pattern was the thesis by Hammel (2013). Only when the hypothetical student was the victim of social exclusion, but not when students became victims of gossip or when friends threatened to end a relationship, was there a statistically significant correlation between middle school teachers’ empathy with the victim and their likelihood to intervene. Moreover, teachers’ general empathic concern and perspective taking were not statistically significantly related with the likelihood to intervene. Similarly, Garner et al. (2013) did not find a relationship between prospective teachers’ self-reported cognitive empathy and their likelihood to intervene in bullying scenarios. Finally, when pre-service elementary and secondary teachers did not indicate their likelihood to intervene in bullying via self-report, but when they were asked in an open-format with researchers coding their responses, there was less evidence of a relationship between teachers’ self-reported empathic concern and perspective taking with their responses to bullying (Tettegah, 2007; 3 of 12 statistically significant effects).

Classroom Management

In seven of ten studies spanning early childhood to tertiary education, there was no statistically significant relationship between teachers’ empathy and classroom management (Abacioglu et al., 2019; Friedman, 2014; Fults, 2019; Gottesman, 2016; Hall, 2009; Heckathorn, 2013; Petsos & Gorizidis, 2019). As Table 5 shows, 83% of the investigated effects were not statistically significant. Except for Gottesman (2016), these studies used other than teacher self-report measures for either empathy or classroom management. In line with the trend to find an association especially when both predictor and outcome are measured via teacher self-report, Hu et al. (2018) found no association between preschool teachers’ self-reported emotional perception and observer ratings of their classroom management (r = .03, p > .05), but they did find a link with teachers’ own perceptions of their classroom management (r = .38, p < .001). However, two studies revealed a positive association between empathy and classroom management. In her thesis, Metaxas (2018) showed that primary and secondary school teachers reporting being more empathic were less likely to choose punitive behavior (r = −.22, p < .01) in response to a hypothetical challenging student. Relatedly, Okonofua et al. (2016) revealed that middle school teachers participating in an empathic mindset intervention were more likely to consider empathic disciplinary strategies (r = .40, p < .01) rather than punitive approaches (r = −.41, p < .01). However, these results are again based on teachers’ evaluations of hypothetical scenarios.

Instructional Support

In three of six studies, all relying not only on teacher self-report questionnaires, there was no evidence (85% of the investigated effects were not significant; see Table 5) for a relationship between teachers’ empathy and the levels of instructional support they provide for students in secondary school or for college students (Friedman, 2014; Hall, 2009; Wen, 2020). Even though Heckathorn (2013) found that adults in an evening master’s program rated those teachers who obtained higher test scores in perceiving emotions as providing more organized and clear instruction (r = .26, p < .01), there was no statistically significant correlation with understanding emotions. Moreover, neither perceiving nor understanding emotions were associated with personal goal attainment defined as the degree to which the teacher attended to students’ individual learning needs and interests. Notably, these results are based on only N = 11 teachers. Again, Hu et al. (2018) found a link between preschool teachers’ self-reported emotional perception with their self-reported quality of instructional support (r = .36, p < .001), but not with observers’ ratings of instructional support (r = −.03, p > .05). Khodadady (2012) obtained a small, but statistically significant positive relationship between high school teachers’ self-reported empathy and student-reported facilitation (r = .05, p < .05). However, the nesting of students within classes was not considered in the analyses so caution is warranted in interpreting this finding.

Effects on Student Outcomes

We identified twelve studies investigating the role of empathy in student outcomes: four studies measured cognitive student outcomes and ten measured psychosocial student outcomes including, for example, student engagement, conduct problems, or prosocial behavior.

Cognitive Student Outcomes

Two of four studies, which assessed teacher empathy via student report and a test instrument, provided less support (64% of the investigated effects were not significant; see Table 5) for the role of secondary school teacher empathy in students’ cognitive outcomes in terms of achievement test scores, grades, and students’ self-reported abilities in mathematics (Aldrup et al., 2020; Curci et al., 2014). Franklin (2014) found a positive relationship between elementary school teachers’ self-reported empathic concern and students’ reading (r = .17, p < .05), but not mathematics achievement growth (r = .00, p > .05). Latchaw (2017) revealed that college students rating their teachers’ awareness of others’ emotions higher expected a better end-of-course grade (r = .22, p < .01).

Psychosocial Student Outcomes

Seven of ten studies found little evidence of a relationship between teacher empathy and students’ psychosocial outcomes (72% of the investigated effects were not significant; see Table 5). More specifically, preschool teachers who reported a greater ability in perceiving the emotions of others neither noticed more social skills nor fewer peer problems, general anxiety, emotional problems, aggressiveness, conduct problems, or hyperactivity among their students (Poulou, 2017; Poulou et al., 2018). Contrary to expectations, students even reported more frequent bullying in middle schools employing teachers who rated their empathic concern and perspective taking higher (Underwood, 2010). Moreover, teachers at integrated schools who perceived themselves as more empathic did not rate their students as showing less misconduct in class (Nizielski et al., 2012) and students did not indicate greater receptivity and involvement in these teachers’ courses (Wen, 2020). Likewise, in two small studies (N ≤ 12) with teachers at a junior high school and in an adult evening master’s program, respectively, there was no association between teachers’ ability to perceive and understand emotions as measured with the MSCEIT (Mayer et al., 2002) and student-reported involvement in class (Heckathorn, 2013), their scholastic self-esteem, metacognitive beliefs, and goal setting (Curci et al., 2014; one of 14 correlations was statistically significant, but all rs < .12).

In contrast, Aldrup et al., (2020) showed that secondary school students who perceived their mathematics teacher as more sensitive reported lower mathematics anxiety and were appraised as less anxious by their parents (−.18 ≤ r ≤ −.07). Okonofua et al. (2016) found that middle school students’ suspension rates were statistically significantly lower among teachers who had participated in an empathic mindset intervention (r = –.10, p < .001). Furthermore, Polat and Ulusoy-Oztan (2009) showed that primary school students rated their emotional intelligence higher when their teachers evaluated their own ability to perceive other people’s emotions more positively (r = .30, p < .01).

Discussion

Empathy is considered one factor determining prosocial behavior among all humans (Preston & de Waal, 2002) and argued to be relevant for teachers’ professional effectiveness given the high social and emotional demands inherent to daily interactions with students (Brackett & Katulak, 2007; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009). Against this background, we aimed to review the empirical evidence for these theoretical assumptions and identified 41 journal articles, theses, chapters, and conference papers providing insights to the role of teacher empathy in the quality of teacher-student interactions and student outcomes. To date, most research has accumulated on the relationship between teachers’ empathy and their emotional support for students, whereas we know much less about other domains of teacher-student interactions and student outcomes. Overall, there was limited evidence for a statistically significant positive association between empathy and any of the dependent variables considered in this research synthesis. The exception were studies relying exclusively on teacher self-report for assessing empathy and their own (likely) behavior in terms of quality of teacher-student interactions (e.g., Abacioglu et al., 2020). In this regard, the most consistent finding was that teachers reporting greater empathy for a bullied student in a hypothetical scenario indicated a greater likelihood to intervene in the situation (e.g., Sokol et al., 2016; Yoon, 2004). Even though these studies show that feeling concerned for students in specific situations makes teachers more motivated to help them, it remains unknown whether teachers would actually behave as intended in a real classroom situation and whether they would choose appropriate interventions. Thus, at first glance, these findings do not support the theoretical assumptions of an association of teacher empathy with the quality of teacher-student interactions and student outcomes.

One explanation might be that other social-emotional characteristics are more important for predicting the quality of teacher-student interactions, emotional support in particular, and student outcomes. For example, recent studies linked teachers’ mindfulness—a nonjudgmental awareness and acceptance of one’s present experiences (Brown & Ryan, 2003)—to higher levels of emotional support for students (Jennings, 2015; Jennings et al., 2017). Furthermore, there is growing evidence regarding the importance of teacher well-being. Prior studies found a positive association between teachers’ work enthusiasm with emotional support, student motivation, and achievement, whereas the reverse was true for burnout symptoms (Arens & Morin, 2016; Klusmann et al., 2016; Keller et al., 2016; Kunter et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2015). However, it is also possible that researchers have not been able to discover a relationship between empathy, the quality of teacher-student interactions, and student outcomes because they have not attended to some key methodological and conceptual issues that we consider vital for obtaining valid results in future research.

Avenues for Future Research

Dealing with Common Method Bias and the Valid Assessment of Empathy

The majority of studies we reviewed applied teacher self-report measures of empathy in combination with self-report measures of interaction quality and student outcomes. This poses the risk of common method bias, which can cause positively biased associations between predictor and outcome variables (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Therefore, research can only provide valid conclusions about the role of teacher empathy in the quality of teacher-student interactions and student outcomes if more studies combine different data sources. To achieve this, researchers in the field have pursued different strategies.

One approach is to treat common method bias by measuring the dependent variable via student questionnaires, classroom observations, or achievement tests (e.g., Hu et al., 2018). This approach enables researchers to investigate whether teacher empathy becomes manifest in teachers’ actions and whether others notice differences between teachers with higher versus lower empathy. Considering the perspectives of other raters except for the teacher appears particularly important because students and external observers often perceive interaction quality differently than the teachers themselves do (e.g., Fauth et al., 2014a; Kunter & Baumert, 2006). In this review, ten studies combined teacher self-report measures with other sources for assessing the outcome. The evidence in these studies was mixed and some found at least partial support for the hypothesis that empathy is associated with effective teaching (Franklin, 2014; Ghanizadeh & Moafian, 2010; Khodadady, 2012; Polat & Ulusoy-Oztan, 2009; Swartz & McElwain, 2012) whereas others did not (Fults, 2019; Hu et al., 2018; Petsos & Gorizidis, 2019; Underwood, 2010; Wen, 2020).

One explanation for the heterogeneous results could lie in the comparably small sample sizes. Only two of the studies were based on more than 100 participants—a sample size that is required for detecting medium effects—and five included 50 or less. Small sample sizes reduce the statistical power to detect meaningful effects. Yet, there is also evidence that effect sizes are larger in small samples, perhaps, because they are less likely to be published when yielding insignificant results than expensive larger studies (Slavin & Smith, 2009). Thus, future studies should include a sufficient number of teachers to avoid these issues.

Another reason for the inconsistent findings could be the construct validity of self-report empathy measures. Caring for others is at the core of teachers’ professional identity so self-serving bias could cause teachers to describe themselves more positively in terms of their empathy level (O’Connor, 2008; Wubbels et al., 1993). Furthermore, the self-assessment of social-emotional abilities is now questioned as correlations with objective tools are rather small but objective tools appear more closely related to social behavior (Brackett & Mayer, 2003, Brackett et al., 2006). Therefore, the use of tests rather than self-report questionnaires (e.g., Hall, 2009) could improve the measurement of empathy in future research. At the same time, this strategy provides the opportunity to avoid common method bias. However, the few studies that have pursued this strategy have mostly yielded insignificant results. Again, only two of nine studies included more than 100 participants and five drew on only 32 teachers or less. Thus, studies with appropriate power are needed to evaluate the potential of objective empathy assessments.

In addition, we expected the closest relationship between empathy and emotional support, but as evident in Figure 3, many of the methodologically sophisticated studies included either other domains of teacher-student interaction quality or student outcomes (e.g., Corcoran & Tormey, 2013; Hall, 2009). Thus, it was less likely to find pronounced effects in these studies from a conceptual point of view.

Finally, except for Friedman (2014), previous work with objective assessments has relied on tools that appear rather distant from teachers’ daily work with students. For example, in one subtest of the frequently used MSCEIT (Mayer et al., 2002), participants see images of landscapes and artwork and evaluate the degree to which the pictures express certain emotions. Consequently, it appears necessary to use measurement instruments more closely aligned with teachers’ professional tasks.

A Profession-Specific Perspective on Teacher Empathy

As the findings from our review showed, studies investigating the relationship between empathy with victims of bullying and the likelihood to intervene yielded the most robust and substantial correlations. In addition to the fact that both were assessed from the teacher perspective, one explanation for the close association could be that independent and dependent variable refer to the same situation. Another finding supporting the value of a profession-specific approach is that among the few studies of this kind, which either asked students about their teachers’ sensitivity for their emotions or intervened in teachers’ empathy with students (Aldrup et al., 2020; Okonofua et al., 2016), found statistically significant associations with interaction quality and student outcomes. However, only a few researchers have adapted and developed empathy questionnaires and tests that explicitly ask teachers to refer to the professional context; hence, more instruments of this kind are needed (Friedman, 2014; Wu et al., 2019; Zinsser et al., 2015). To go beyond paper-pencil formats and for a realistic assessment of cognitive empathy, the dyadic interaction paradigm (Ickes, 2001), which is frequently applied in empathic accuracy research, could serve as a guideline. Here, a dyad’s interaction is videotaped and each participant individually writes down their thoughts and feelings during specific episodes. Then, the partner’s task is to indicate what their counterpart experienced. In researching teachers’ empathy, one could videotape teacher-student interactions. Furthermore, teachers’ affective empathy has been only assessed via questionnaires thus far, which appears reasonable because it reflects a person’s subjective experiences. Nonetheless, one could also consider using teachers’ facial expressions in response to students’ emotions as an indicator of their affective empathy (e.g., Marx et al., 2019).

Moreover, in developing profession-specific instruments, considering different levels of specificity would allow us to gain additional insights about the degree to which teacher empathy is context-dependent. One option would be a situation-specific assessment as was done in bullying research (e.g., Yoon, 2004). Likewise, Friedman (2014) developed a tool for measuring teachers’ ability to perceive and understand students’ emotions during a hypothetical disciplinary incident in class. Another option would be a class-specific assessment. At the secondary school level in particular, teachers see different groups of students each day and it may be easier for them to empathize with some than with others, for example, depending on the students’ age or the number of lessons they see each other per week. Furthermore, Frenzel et al. (2015) showed that teachers’ emotions largely depend on the class they teach. Being in a class that elicits enjoyment rather than anger or anxiety could facilitate cognitive empathy because positive emotions promote cognitive processes (e.g., broaden-and-build theory, Fredrickson, 2001). Of course, one could think of several other relevant specific situations such as empathy with students struggling with content or with students from specific backgrounds who are at risk of adverse developmental trajectories. For example, Warren (2015) developed a scale measuring teacher empathy for African American males.

Importantly, when using situation- or class-specific assessments, we suggest aligning the specificity of the empathy measure and the dependent variable of interest. We will give an example to illustrate this point: The instrument developed by Friedman (2014) measures empathy in a very specific situation, but does not tell us about the teachers’ ability to recognize their students’ emotions and take their perspectives in other contexts. Hence, finding an association with dependent variables closely connected to the specific situation of the empathy measure is most likely, whereas a relationship with broader variables appears less probable. Finding no relationship between Friedman’s (2014) measure of empathy and classroom observations of teacher-student interactions is in line with this idea. Inversely, this means that one should refrain from using situation- or class-specific instruments when the research interest is in explaining teaching effectiveness more broadly.

Interplay with Other Teacher Characteristics and Students’ Prerequisites

In addition to methodological challenges, our unexpected finding could be because teacher empathy alone is not sufficient to achieve high-quality teacher-student interactions and positive student outcomes. First, a hierarchical organization of social-emotional competence is hypothesized with empathy being a precursor of more advanced abilities such as emotion and relationship management (Joseph & Newman, 2010; Mayer & Salovey, 1997). From this perspective, it can be argued that teacher empathy can only be effective in combination with knowledge and skills about effective behavior in social situations. In line with this, Aldrup, Carstensen et al. (2020) showed that teachers with greater knowledge about relationship management reported providing more emotional support and perceived their relationships with students more positively.

Second, it is possible that teacher empathy only shows when teachers are motivated to act accordingly. In other words, they may not always display their full empathic potential. Considering the finding that teachers’ emotions largely depend on the group of students they teach (Frenzel et al., 2015), one could speculate that teachers will be more motivated to demonstrate empathic behavior in a class they like, making a class-specific assessment of empathy particularly interesting in this line of research. Further aspects, such as emotional stability, pro-sociality, or self-efficacy, have been suggested as relevant determinants of the degree to which people perform empathic behavior (Cavell, 1990; DuBois & Felner, 2003; Rose-Krasnor, 1997). Furthermore, teacher empathy may interact with their well-being such that burnout and the lack of emotional resources impair teachers’ empathy (Trauernicht et al., 2021). Likewise, other teacher characteristics may mask their empathy. For instance, the belief that strict discipline is needed because children are naturally rebellious and lazy could lead teacher to suppress empathic tendencies (c.f., Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2006).

Third, empathy may not always be beneficial as is evident in the phenomenon of compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue denotes a loss of interest in empathizing with others and a lack of energy, which can result from self-giving work with people who are in pressing need for help (Adams et al., 2006; Knobloch Coetzee & Klopper, 2010). In other words, excessive empathy puts people at risk of suffering themselves. For example, teachers with greater empathy for victims of bullying also feel angrier and sadder when witnessing bullying incidents (Sokol et al., 2016). To alleviate negative feelings and protect one’s emotional resources, teachers may eventually distance themselves from their students (for a similar line of reasoning, also see Maslach et al., 2001). In line with this, prior research showed that people who feel distressed by seeing other people suffering avoid the situation or even show aggressive reactions (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1990). Hence, both low and extremely high levels of teacher empathy might be problematic potentially causing a nonlinear relationship with the quality of teacher-student interactions and student outcomes. Considering this, teachers may only benefit from extremely high levels of empathy if they are able to distance themselves from the emotional demands of their work. Potentially interesting moderators of the empathy-outcome relationship include emotion regulation and mindfulness. Prior research shows that they reduce negative emotions so they could be a protective resource for highly empathic teachers (Klingbeil & Renshaw, 2018; Lee et al., 2016).

In addition to investigating the interplay between empathy and other social-emotional teacher characteristics, we suggest considering whether students’ prerequisite moderate the role of empathy in the quality of teacher-student interactions and student outcomes. For example, prior research shows that teachers play a more prominent role in the development of students at risk of adverse educational trajectories (Hamre & Pianta, 2005; Klusmann et al., 2016). Hence, teacher empathy might be particularly relevant for students with a low socioeconomic status or with cognitive or social-emotional difficulties. Another important aspect might be students’ age. On the one hand, one could assume that teacher empathy is particularly relevant for young students, for example, because they are still more dependent on adult support to regulate their emotions (Calkins & Hill, 2009). On the other hand, student disengagement represents a particular challenge during adolescence and teachers often struggle to meet adolescents’ developmental needs (Eccles & Midgley, 1989; Wang & Eccles, 2012). Thus, teachers who consider adolescents’ perspectives and care for their feelings might be particularly important during this phase. In line with this assumption, meta-analytic evidence shows that the association between the teacher-student relationship and student engagement and achievement gets closer for older students (Roorda et al., 2017).

Limitations

In this article, we aimed to provide the first comprehensive overview of prior research on the relationship between teacher empathy, teacher-student interactions, and student outcomes. Therefore, we included studies from different lines of research that diverge in their operationalization of empathy. For example and as outlined in the Results section, even though both the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (Davis, 1980) and the MSCEIT (Mayer et al., 2002) were designed to measure whether one is able to consider other’s perspectives, the types of questions/tasks differ substantially. Thus, it is unclear whether all studies actually measured the same underlying construct. A similar problem applies to our dependent variables where there was large heterogeneity in terms of the instruments.

Furthermore, we decided to consider theses, proceedings papers, and book chapters in addition to studies from peer-reviewed journals. Almost half of the studies were not from journal articles. Thus, our approach allowed for a more exhaustive overview of the field and helped to reduce the risk of publication bias. The large number of studies with insignificant results let us conclude that our strategy for reducing publication bias was successful. However, it may have reduced the quality of the included studies. Even though follow-up analyses revealed no differences between the publication types in terms of sample size or the avoidance of common method bias, we cannot rule out other potential limitations such as lower quality of data collection, preparation, and analyses in studies from sources other than journals.

In addition, a large number of studies assessed constructs relevant for our review without reporting correlation analyses. Due to our concerns about the reliance on teacher self-report measures for assessing the independent and dependent variables, we decided to contact the authors only when they had pursued a different methodological approach. Because studies that included only teacher questionnaires typically found closer associations, we should note that our decision might have reduced the number of statistically significant results.

Finally, a meta-analytical analysis would have been ideal to investigate the extent to which methodological study characteristics moderate the size of effects (Borenstein, 2009). Nonetheless, we decided against this approach as we identified only a relatively small number of relevant studies for most dependent variables. In addition, we had the impression that computing an overall effect size was not appropriate because of the huge heterogeneity in the research field. The different methodological approaches are not equally valid for assessing empathy and sophisticated studies typically included small samples reducing their weight in meta-analyses.

Conclusion

Theoretical models (e.g., Jennings & Greenberg, 2009) emphasize the relevance of teachers’ empathy for high-quality teacher-student interactions and positive student outcomes, but to date, only limited evidence supports this claim. Nonetheless, rather than abandoning the idea that teacher empathy is a relevant construct, we call for methodologically sophisticated studies that go beyond teacher self-report and allow for robust conclusions. Perhaps, we would otherwise overlook an important social-emotional teacher characteristic, where there is an urgent need for action given that teachers frequently struggle to recognize student emotions (Karing et al., 2013; Spinath, 2005).

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the review

*Abacioglu, C. S., Volman, M., & Fischer, A. H. (2019). Teacher interventions to student misbehaviors: The role of ethnicity, emotional intelligence, and multicultural attitudes. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00498-1

Adams, R. E., Boscarino, J. A., & Figley, C. R. (2006). Compassion fatigue and psychological distress among social workers: A validation study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(1), 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.103

*Abacioglu, C. S., Volman, M., & Fischer, A. H. (2020). Teachers’ multicultural attitudes and perspective taking abilities as factors in culturally responsive teaching. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(3), 736–752. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12328

Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Haerens, L., Soenens, B., Fontaine, J. R. J., & Reeve, J. (2019). Toward an integrative and fine-grained insight in motivating and demotivating teaching styles: The merits of a circumplex approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(3), 497–521. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000293

Ahmed, W., van der Werf, G., Minnaert, A., & Kuyper, H. (2010). Students’ daily emotions in the classroom: Intra-individual variability and appraisal correlates. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(4), 583–597. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709910X498544

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84(5), 888–918. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888

Arens, A. K., & Morin, A. J. S. (2016). Relations between teachers’ emotional exhaustion and students’ educational outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(6), 800–813. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000105

Aldrup, K., Carstensen, B., & Klusmann, U. (2021). Is empathy the key to effective teaching? A systematic review of its association with teacher-student interactions and student outcomes. PsychArchives.https://doi.org/10.23668/PSYCHARCHIVES.5209

Aldrup, K., Carstensen, B., Köller, M. M., & Klusmann, U. (2020). Measuring teachers’ social-emotional competence: Development and validation of a situational judgment test. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 217. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00892

Aldrup, K., Klusmann, U., Lüdtke, O., Göllner, R., & Trautwein, U. (2018). Social support and classroom management are related to secondary students’ general school adjustment: A multilevel structural equation model using student and teacher ratings. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(8), 1066–1083. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000256

*Aldrup, K., Klusmann, U., & Lüdtke, O. (2020). Reciprocal associations between students’ mathematics anxiety and achievement: Can teacher sensitivity make a difference? Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(4), 735–750. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000398

*Barłożek, N. (2015). EFL Teachers’ affective competencies and their relationships with the students. In Piechurska-Kuciel, Ewa & Szyszka, Magdalena (Ed.), The ecosystem of the foreign language learner (pp. 97–115). Springer.

Bar-On, R. (1997). BarOn Emotional Quationt Inventory (EQ-i): Technical manual. Multi-Health Systems.

Bar-On, R. (2002). Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory: Short (EQ-i:S): Technical manual. Multi-Health Systems.

Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelwright, S. (2004). The empathy quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(2), 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADD.0000022607.19833.00

Batson, C. D. (2009). These things called empathy: Eight related but distinct phenomena. In J. Decety & W. J. Ickes (Eds.), Social neuroscience series: The social neuroscience of empathy (pp. 3–16). MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262012973.003.0002

Batson, C. D., Ahmad, N., Lishner, D. A., & Tsang, J.-A. (2002). Empathy and altruism. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 485–498). Oxford University Press.

Bieg, M., Goetz, T., Sticca, F., Brunner, E., Becker, E., Morger, V., & Hubbard, K. (2017). Teaching methods and their impact on students’ emotions in mathematics: An experiencesampling approach. ZDM, 49(3), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-017-0840-1

Borenstein, M. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

Brackett, M. A., & Katulak, M. A. (2007). Emotional intelligence in the classroom: Skill-based training for teachers and students. In J. Ciarrochi & J. D. Mayer (Eds.), Applying emotional intelligence: A practitioner’s guide (pp. 1–27). Psychology Press.

Brackett, M. A., & Mayer, J. D. (2003). Convergent, discriminant, and incremental validity of competing measures of emotional intelligence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(9), 1147–1158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203254596

Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., Shiffman, S., Lerner, N., & Salovey, P. (2006). Relating emotional abilities to social functioning: A comparison of self-report and performance measures of emotional intelligence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(4), 780–795. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.780

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Butler, R. (2012). Striving to connect: Extending an achievement goal approach to teacher motivation to include relational goals for teaching. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 726–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028613

*Byers, D. L., Caltabiano, N., & Caltabiano, M. (2011). Teachers’ attitudes towards overt and covert bullying, and perceived efficacy to intervene. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(11), 8. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2011v36n11.1