Abstract

Cancer metabolic heterogeneity develops in response to both intrinsic factors (mutations leading to activation of oncogenic pathways) and extrinsic factors (physiological and molecular signals from the extracellular milieu). Here we review causes and consequences of metabolic alterations in cancer cells with focus on hypoxia and acidosis, and with particular attention to carbonic anhydrase IX (CA IX). CA IX is a cancer-associated enzyme induced and activated by hypoxia in a broad range of tumor types, where it participates in pH regulation as well as in molecular mechanisms supporting cancer cells’ invasion and metastasis. CA IX catalyzes reversible conversion of carbon dioxide to bicarbonate ion plus proton and cooperates with a spectrum of molecules transporting ions or metabolites across the plasma membrane. Thereby CA IX contributes to extracellular acidosis as well as to buffering intracellular pH, which is essential for cell survival, metabolic performance, and proliferation of cancer cells. Since CA IX expression pattern reflects gradients of oxygen, pH, and other intratumoral factors, we use it as a paradigm to discuss an impact of antibody quality and research material on investigating metabolic reprogramming of tumor tissue. Based on the validation, we propose the most reliable CA IX-specific antibodies and suggest conditions for faithful immunohistochemical analysis of molecules contributing to heterogeneity in cancer progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

During cancer progression, tumor cells are exposed to multiple physiological constraints present in the growing tumor tissue. These constraints dynamically change in spatial and temporal manner, generating selection pressures and adaptive responses leading to expansion of cancer cells that are able to survive and sustain proliferation. Selected cancer cell subpopulations exhibit phenotypic plasticity and invasive/pro-metastatic behavior, and contribute to complex tissue architecture with various physiological gradients. One of key adaptations to fluctuating supplies and demands for survival and proliferation of cancer cells is their metabolic reprogramming.

2 Causes and consequences of metabolic alterations and heterogeneity

2.1 Oncogenic activation

Initial tumor growth is associated with mutations that trigger deregulated oncogenic signaling. Activated oncoproteins and/or inactivated tumor suppressor proteins promote abnormal cell proliferation not only by activating positive regulators and counteracting negative regulators of the cell cycle, but also by redirecting cellular metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis [1,2,3]. They do so through signal transduction pathways leading to enhanced transcription, translation, and/or catalytic activation of the glycolytic enzymes (including glucose transporter GLUT, lactate dehydrogenase LDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase PDK, and monocarboxylate transporter MCT) as explained in more detail elsewhere. Classical examples of this phenomenon include activated MYC and RAS and inactivated p53, von Hippel-Lindau (VHL), and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), but also many other regulatory molecules [4, 5]. In addition, activating mutations can occur directly in the components of the metabolic pathways, such as isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH), fumarate hydratase (FH), and/or succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) [6,7,8]. Albeit glycolysis is not as efficient as respiration in energy production, it allows for synthesis of cellular biomass that is particularly important for uncontrolled proliferation of cancer cells [1, 2]. Yet, most cancer cells retain functional mitochondria that are essential for lipid synthesis and protein acetylation [6].

2.2 Stresses in tumor microenvironment

Proliferative advantage of cancer cells enables in situ expansion of tumor lesion until the demands for nutrients and oxygen exceed their supply from the nearest functional blood vessel [9,10,11]. Long-lasting lack of oxygen (i.e., anoxia) is incompatible with the survival of cells and generates necrotic regions that are histological surrogates of poor cancer prognosis. Lowered oxygenation (i.e., hypoxia) reinforces the shift of cancer cells to glycolytic metabolism and induces additional phenotypic changes, such as angiogenesis generating aberrant tumor vasculature, cell–cell deadhesion linked with migration-invasion, and genomic instability facilitating accumulation of mutations [12]. Mechanisms behind these phenotypic changes include both transcriptional and translational reprogramming governed principally by the hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIFs) and by the unfolded protein response (UPR)-driven pathways, as reviewed in [13,14,15,16].

Importantly, these adaptations are not uniform. They vary depending on many circumstances including cancer type/origin, position of cells in the diffusion gradients, and time of their exposure to the hypoxic stress [11, 17]. Thus, metabolic preferences of the peri-necrotic cancer cells chronically suffering from severe hypoxia considerably differ from the preferences of the moderately hypoxic cells as well as from the oxygenated cells located proximally to the vasculature [18].

In a simplified interpretation, cells in the region of severe hypoxia are highly dependent on glycolysis, while the moderately hypoxic cells can utilize tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and oxidative phosphorylation system (OXPHOS) by consuming lactate exported from the highly glycolytic cells, a phenomenon known as metabolic symbiosis [19, 20]. Normoxic cells exploit glycolysis in the presence of oxygen (so-called Warburg effect) along with TCA/OXPHOS, driven by various fuels available in the tumor microenvironment (TME), including amino acids and lipids [11, 17].

Oncogenic metabolism produces an excess of acidic metabolic products, such as lactate, protons, and carbon dioxide. Although these metabolites are primarily generated intracellularly, machinery protecting cancer cells from an intracellular acidosis extrudes them to the pericellular space either by the active export mechanisms or by altering/reversing their gradients across the plasma membrane [21]. Consequently, these acidic products accumulate in TME (especially when distant from the blood flow) and generate an extracellular acidosis, which has a significant impact on metabolic performance as well as on additional phenotypic characteristics of tumor cells contributing to their pro-metastatic behavior and to cancer progression [18, 22]. Acidosis was shown to directly affect protonation states of important regulatory proteins with pH-sensitive amino acids, as exemplified by p53, sodium-proton exchanger 1 (NHE1), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), ß-catenin, etc., thereby causing structural changes that results in their altered functions [23]. Moreover, intracellular acidosis leads to increased accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and enhanced ferroptosis, a non-apoptotic form of iron-dependent cell death [24, 25]. Acidic pH is also linked with immune cells’ anergy and resistance to anticancer drugs [26].

Metabolic heterogeneity is also developing along the cancer progression stages. Invasive and circulating cancer cells depend on the acquisition of an anchorage-independence to avoid anoikis and gain metabolic phenotype overcoming excessive ROS production and bioenergetic crisis caused by the loss of attachment signals. These non-adherent cells require high amounts of ATP for survival (and not the biomass for proliferation), thus relying more on mitochondrial metabolism during their detachment, invasion, and flow within the blood stream or in lymphatics [27,28,29].

2.3 Tumor-stroma cross-talk

Diversity of responses to physiological stresses in TME by cancer cell subpopulations is not the only determinants of the metabolic heterogeneity in tumors. This phenomenon gains complexity through the cross-talk of cancer cells with the cells in stroma. Stroma is a connective component of the tumor tissue showing highly variable extent and composition depending on the organ of residence, tumor type, and cancer stage. Different stromal cells communicate with cancer cells via multiple signaling entities including growth factors, exosomes, and micro-/nanotubular structures, but also via metabolites [17, 30, 31]. Cancer and stromal cells can live in a metabolic symbiosis not only by releasing/consuming lactate, but also by venting of cancer cells-produced CO2 via gap junctions of stromal cells and potentially through additional mechanisms that still remain to be elucidated [32, 33].

2.4 Links between pH control and metabolism

Successful adaptation of tumor cells to oncogenic metabolism and/or hypoxia strongly depends on activation of the pH control machinery [18, 34]. Its prime role is to maintain a slightly alkaline intracellular pH (pHi ~ 7.2 to 7.7) that is required for the effective biosynthesis, ATP production, and signaling [35]. Major components of this pH control machinery can be induced by hypoxia and/or are pH-sensitive molecules, including sodium-proton exchangers (e.g., NHE1), anion exchangers (e.g., AE2), sodium-bicarbonate transporters (e.g., NBCe1), monocarboxylate transporters (MCT1 and MCT4), and related molecules. Moreover, MCTs can also affect the glycolytic flux by mediating co-extrusion of lactate and protons and therefore represent one of the intersecting points of metabolism and pH control [20, 22, 36].

Besides extrusion of lactate and protons, pHi control also involves removal of the intracellular CO2 by diffusion to extracellular space as well as the import of bicarbonate ions generated by the hydration of pericellular CO2 to cytoplasm, leaving protons from the same reaction outside the cells. These processes lead to extracellular acidosis that often persists in tumor microenvironment because the acidic metabolic products cannot be effectively removed by the aberrant tumor vasculature. Extracellular acidosis can activate proteolytic enzymes that degrade extracellular matrix and facilitate invasion and metastasis. Moreover, cancer cells with activated pH-regulating machinery can resist toxic effects of extracellular acidosis generated by oncogenic metabolism and even benefit from an acidosis-supported acquisition of aggressive tumor phenotypes. Thus, cancer cells gain selective advantage against surrounding normal cells that cannot adapt [37].

Acidosis strongly influences tumor metabolic preferences, reducing glycolysis while promoting mitochondrial activity. It supports progression-related processes such as angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis and is linked to cellular phenomena including aneuploidy and mutation rate, autophagy and survival, cell migration, and release of exosomes [18]. Moreover, acidosis is enriched at tumor-stroma interfaces (in addition to regions of chronic hypoxia) and cells within the acidic front are invasive and proliferative [33, 38]. From the clinical point of view, intratumoral acidosis is associated with resistance to chemo-, radio-, and immuno-therapies.

3 Carbonic anhydrase IX and its role in tumor metabolism

3.1 CA IX essentials

Carbonic anhydrase IX (CA IX) has been initially cloned as a cancer-associated transmembrane enzyme with an active site facing the extracellular space and catalyzing the reversible conversion of carbon dioxide to bicarbonate ion and proton [39, 40]. CA IX shows very high catalytic activity, comparable to the CA II isoform that belongs to the most active enzymes in general. Interestingly, CA IX activity culminates at acidic pH around 6.5, typical for tumor microenvironment [41, 42]. Moreover, CA IX is strongly responsive to hypoxia both at the level of expression by the HIF-mediated transcriptional activation [43], and at the level of catalytic activity by the protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated phosphorylation [44]. In addition, available experimental data show that the expression of CA IX can be induced under normoxic conditions in connection with oncogenic activation of the RAS, SRC, or RET pathway, and upon treatment with glucose, lactate, and glutamine (particularly in combination with serum growth factors) that are important substrates of tumor metabolism [45,46,47,48,49].

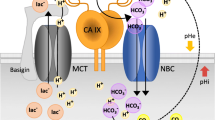

CA IX is an important constituent of pH regulation in tumor cells via contribution to intracellular neutralization/alkalization and extracellular acidification [50,51,52]. Indeed, CA IX cooperates with a number of genuine pH regulators mentioned above, including NBCe1 and NBCn1, MCT1 and MCT4, NHE1, AE2, and NCX1 (Fig. 1) [53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. These cooperative activities are mainly dependent on the enzyme active site in the CA domain localized in the central part of the CA IX ectodomain near its transmembrane region, as described in [53,54,55] and depicted below. However, the N-terminal part (so-called PG region) protruding to the extracellular space participates in the non-catalytic pH regulation, as an antenna enhancing export of protons coupled with export of lactate ions via MCTs [56,57,58]. In fact, CA IX acts as an extracellular pH–stat, maintaining an acidic tumor extracellular pH that is tolerated by cancer cells and supports their pro-metastatic behavior [52]. CA IX-mediated extracellular acidosis is also associated with decreased immune activity in the tumors of patients with a broad spectrum of solid malignancies [60]. At the same time, CA IX stabilizes intracellular pH that is conducive to survival and proliferation [6, 51]. Recently, Chafe et al. have demonstrated that the role of CA IX in maintaining an alkaline intracellular pH is critical for suppression of ferroptosis [25].

Schematic view of the CA IX position in molecular pathways driving metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells. Oncogenic activation and hypoxia drive metabolic reprogramming in part via HIF-mediated induction and/or activation of certain glycolytic enzymes (LDHA) and transporters of glucose (GLUT), lactate (MCT), and amino acids (AAT). This allows cancer cells to generate energy and biomass for survival and proliferation. At the same time, HIF induces key components of pH regulating machinery, including ion transporters (NBC and NCX) as well as carbonic anhydrase IX (CA IX), in order to protect cancer cells from intracellular acidosis generated by the oncogenic metabolism. CA IX cooperates with these molecules via its extracellular domains either in a catalytic or in a non-catalytic manner thereby regulating pH and supporting metabolic adaptations of cancer cells

The effects of CA IX on tumor phenotype can be blunted either by the silencing/suppression of the CA IX expression, or by the small molecule inhibitors of the CA IX catalytic activity, or by the CA IX-specific antibodies as documented in a number of published studies and reviews [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. Moreover, the knowledge obtained in pre-clinical studies of CA IX inhibitors and/or antibodies has opened the window for novel anticancer strategies, some of which have been translated into the clinical trials (reviewed in [69] and listed in https://clinicaltrials.gov].

3.2 CA IX and metabolic reprogramming

Since hypoxia and acidosis are intimately coupled with expression and activities of enzymes involved in oncogenic metabolism, it is not surprising that CA IX can play a role in metabolic pathways, echoing intratumoral oxygen and pH gradients in metabolic heterogeneity of tumor tissue. CA IX expression and/or activity appears to be required for accelerated lactate efflux via MCTs [57, 58], for full expression and activity of PDK1, a gate-keeping enzyme to the TCA cycle in mitochondria [70, 71], for full expression and activity of a key glycolytic enzyme LDHA [72], and ultimately for maximizing glycolytic flux and facilitating cell proliferation in hypoxic/acidic TME [73]. This conclusion is in line with the fact that glycolysis both generates and senses pH changes caused by the formation and accumulation of acidic metabolites [74, 75].

CA IX also plays a role in molecular mechanisms mediating cell adhesion-migration-invasion [76, 77]. On one hand, CA IX can affect the assembly and maturation of focal adhesion contacts during cell attachment and spreading on solid support [78, 79], and on the other one, it can destabilize E cadherin-mediated intercellular contacts [80] and facilitate migration/invasion. CA IX re-localizes to cellular leading-edge structures, namely filopodia during migration and invadopodia during invasion, where it contributes to pH regulation at both sides of the plasma membrane [54, 81]. It operates via coordinated regulation of an interactome composed of bicarbonate transporters and amino acid transporters as well as cortactin, integrins, and metalloproteinases [81,82,83]. This also implies possible involvement of CA IX in metabolic processes that supply energy both to (1) formation and growth of these highly dynamic subcellular structures potentially via podosome-confined glycolysis, as suggested by Stock and Schwab [84], and (2) movement and protrusion of individual cells or cell clusters via enhanced respiration, mitochondrial biogenesis, and reduced lipogenesis [85, 86].

3.3 CA IX as a surrogate marker of hypoxia, acidosis, and glycolytic metabolism

CA IX is mostly viewed as a biomarker of hypoxia and/or acidosis. It is expressed in many tumor types and shows highly heterogeneous expression pattern, as reviewed in [68]. It is usually localized in broader peri-necrotic zones involving both highly and moderately hypoxic cells that are viable and possess a strong metastatic potential. Because of the responsiveness to both severe and moderate hypoxia, CA IX distribution only partly overlaps with that of HIF-1α and of other hypoxia-regulated proteins induced at different hypoxic thresholds [43, 87, 88]. Occasionally, CA IX distribution is diffused, presumably as a sign of oncogene activation or inactivating mutation of tumor suppressor. CA IX can be also found in HIF-1α negative areas possibly because reoxygenation leads to instantaneous degradation of the HIF-1α but not of the highly stable CA IX. In accord with the CA IX role in pH regulation, its expression is increased at the interface between tumor and stroma, in the acidic front containing invasive and proliferative cells that rely on glycolysis [9, 38].

In light of the data connecting CA IX to glycolytic metabolism, CA IX can be viewed as a surrogate indicator of glycolytic metabolic phenotype. Indeed, data from the literature show that in patients’ specimens of tumors derived from diverse tissue types, CA IX is often correlated, co-expressed, and/or spatially overlapped with the traditional biomarkers of the glycolytic metabolism (GLUT1, MCTs, LDH) and glucose consumption rate (18FDG). For example, significant overall correlation and co-localization of CA IX with GLUT1, MCT4, and MCT1 was demonstrated by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in advanced head and neck carcinomas [89]. Considerable spatial overlap between CA IX and GLUT1 was found in areas of diffusion-limited hypoxia in glioblastomas and astrocytomas [90]. CA IX correlation with GLUT1 was also found in papillary renal cell carcinomas [91], in bladder cancer [92], and in cervical carcinomas [93]. In addition, higher expression of CA IX was linked with the stronger 18FDG uptake in non-small cell lung cancer [94]. CA IX expression was also correlated with LDH5 expression in gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas [95]. Interestingly, analysis of transcriptional profiles of different tumor types fully supports these links (Fig. 2). Altogether, these data reinforce the existence of in vivo link between CA IX and glycolysis.

A heatmap visualizing differential expression of genes coding for the CA IX (CA9) and for the glycolytic enzymes LDHA (supporting glycolysis), LDHB (supporting TCA cycle), and MCT4 (extruding lactate ions and protons) in various tumor samples (the number of samples is indicated in brackets). The color scale ranges from blue (lowest mean expression) through white (average mean expression) to red (highest mean expression). Data were analyzed and extracted through IST (in silico transcriptomics) online (MediSapiens; https://medisapiens.com/), the largest fully integrated and annotated human gene expression data source

4 Challenges for characterizing metabolic heterogeneity in tumor tissues

Current research of cancer metabolism and metabolic heterogeneity in cancer progression focuses primarily on technologically advanced methods of metabolomics, as reviewed by [96]. However, identification of underlying molecular mechanisms still depends on approaches of molecular/cell biology and cancer physiology. Due to a complex nature of this topic, it is extremely important to employ validated research tools and correct methodical approaches as well as appropriate research material.

The need for antibody validation is particularly evident for molecules that are functionally involved in metabolic pathways, irrespective of whether they are detected in cellular extracts, cultured cells, or in tumor tissues [97]. Once the antibody does not fulfill strict specificity and quality requirements, it can provide false data leading to inaccurate interpretation of results. This can eventually obscure the recognition of a real biological role and/or clinical value of the studied molecule. In addition, such situation can result in impairment of data reproducibility and failure of therapeutic targeting strategies, as witnessed in nowadays’ science and clinical R&D. There are also additional challenges including inappropriate tissue material and data presentation that have to be addressed in order to improve the way towards unraveling tumor heterogeneity.

4.1 Quality of antibodies

Looking at the investigations of CA IX as a molecule that contributes to tumor heterogeneity and metabolic reprogramming through response to hypoxia and acidosis, it is evident that researchers use diverse antibodies from various sources, often without proper characterization, just relying on the recommendations in datasheet. To date, more than 1,310 (from 45 providers) and 959 anti-CA IX antibodies are listed in Antibodypedia [98] and CiteAb [99], respectively. Many of these antibodies are routinely used in basic research for detection and quantification of CA IX, as well as for determination of its distribution and interactions within cells. A subgroup of antibodies is also used in clinical studies to reveal the CA IX expression in tissues and its prognostic, diagnostic, and therapeutic potential. However, not all of these antibodies can comply with high standards of performance and reliability.

To clarify this situation, eight commercially available antibodies that are most frequently cited in the numerous clinical studies of CA IX were subjected to a comprehensive validation in our laboratory. Overall reactivity of the antibodies was compared with the providers’ recommendations in the datasheets. Table 1 summarizes an overview of the antibody validation results obtained in five applications, namely WB, ELISA, FACS, IF/ICC, and IHC (see the original validation data in the Supplementary information). Antibody binding regions on the CA IX molecule are depicted in Fig. 3. The antibodies were selected predominantly on the basis of meta-analysis performed by van Kuijk and colleagues [100]. There, the data from 147 clinical studies encompassing more than 24,000 cancer patients were evaluated with respect to CA IX expression assessed by IHC in relationship to several endpoints, including overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), and progression-free survival (PFS). Meta-analysis confirmed the correlation of high CA IX expression to disease progression, locoregional failure, and development of metastasis, independently of tumor type or site. Since most of the included clinical studies (46%) employed M75 monoclonal antibody, it was used as a reference antibody. Moreover, its CA IX specificity and excellent performance was proven in many other research papers from a number of laboratories. Representative IHC staining with M75 antibody is shown in Fig. 4.

Schematic illustration of binding sites of M75 and eight validated antibodies. The positions of antibody binding regions are shown on the schematic model of the CA IX protein comprising a proteoglycan-like (PG) region, carbonic anhydrase (CA) domain, transmembrane (TM) anchor, and intracytoplasmic (IC) tail. Antibody arrangement reflects the information available in the datasheets. Monoclonal and polyclonal type of antibody is depicted using full and dashed line, respectively. No information regarding the immunogen used for the generation of 2D3 monoclonal antibody is available in its datasheet. According to “Ten basic rules of antibody validation” [101], all selected antibodies are correctly described by providers and, with exception of 2D3, have a defined immunogen

Representative images from tumor (CCRCC) and normal kidney tissue stained using M75 reference antibody. Tissue sections were directly incubated with M75 monoclonal antibody for 1 h at RT. Following the incubation with anti-mouse secondary antibody, positive reaction was visualized using DAB as a chromogen. Sections were counterstained with Mayer hematoxylin. A, C Original magnification × 100. B, D Original magnification × 400

Because IHC is (except metabolomics) a key approach in determining tissue expression of regulators/executors of metabolic reprogramming in tumors and in elucidating their clinical value as potential biomarkers and therapy targets, our validation was focused primarily on this application. Specificity of anti-CA IX antibodies in IHC was examined using serial tissue sections of the clear cell renal cell carcinoma (CCRCC) with proven high expression of CA IX compared to the CA IX-negative normal kidney tissue (Supplementary information). In addition to the M75 reference, additional 3 commercial antibodies were found more or less suitable for IHC, considering specific methodical adjustments, such as requirement for antigen retrieval (citrate or EDTA) as well as duration and temperature of staining (1 h at RT versus O/N at 4 °C). Assessment of these methodical details for each particular antibody and their precise description in related publication is extremely important for the reliability and reproducibility of data.

In brief, the validation performed in our laboratory revealed that monoclonal D10C10 and polyclonal antibodies ab15086 and NB100-417 are reliable alternatives to monoclonal antibody M75, while the antibodies H-11 and AF2188 suffer from non-specific reactivity and high background that may potentially lead to false positivity. The antibodies GT12 and 2D3 are not suitable for the detection of CA IX by IHC.

4.2 Identification of antibodies and data presentation

Almost 30% of the IHC studies involved in the meta-analysis by van Kuijk et al. (2016) [100] contain insufficient description of the used anti-CA IX antibody, missing its unambiguous identification and just mentioning the provider (if at all). In some cases, authors declare an incorrect source of the antibody (see Table 2). Since some providers offer a number of different antibodies to CA IX, this introduces a lot of confusion and questions the data interpretation as well as their reproducibility. However, this drawback is not limited to CA IX—it is a generally occurring and persisting problem in the entire biomedical research, since the antibody cannot be recognized in more than a half of all respective publications (as reviewed by [101]).

Moreover, about 14% of papers included in the meta-analysis [100]do not display even the representative images of the IHC stained tissues (neither in the articles themselves, nor in their Supplementary data), thus precluding a visual inspection of the staining intensity and pattern.

4.3 Tissue specimens

Deeper analysis of all CA IX-dedicated IHC studies summarized by van Kuijk and colleagues [100] revealed another problem. Whole tissue blocks were used in 40% of studies, the rest was performed using either biopsy or tissue microarray (TMA). Although there are several advantages favoring the utilization of TMAs in IHC, this approach can lead to loss of important information due to intratumoral heterogeneity, especially when only one TMA core is included in the staining. This is supported by the observation that only 4.7% of breast cancer TMA cores were found CA IX-positive compared to 18.1% of whole tissue blocks [138]. Another factor negatively impacting results of IHC lies in omitting perinecrotic regions from TMA construction. It is well-known that intratumoral hypoxia is reflected histologically by the presence of necrosis, which is considered a bad prognostic factor in cancer patients [176, 177]. Staining pattern of the hypoxia-induced CA IX is very heterogeneous, often confined to perinecrotic areas, and therefore, use of TMAs devoid of necrotic regions is not appropriate for the CA IX IHC analysis. The same is true for other molecules related to cancer metabolism, which is a phenomenon with inherent heterogeneity.

In case of TMA, the best way how to overcome the problem of tumor tissue heterogeneity is to analyze multiple cores. According to several studies, up to 98% consistency with the results from full-block sections can be achieved when at least three TMA cores are stained. Lower concordance is observed with only 1 or 2 cores (as reviewed in [178]). In meta-analysis presented by van Kuijk et al. (2016), 3 or more cores were used in 41.7% of TMA-based IHC studies, and less than three cores were used in 38.3% cases, whereas in the rest of the studies, tissue selection was not properly defined.

While insufficient identification and quality of antibodies clearly contribute to replication crisis in general, use of inappropriate tissue material particularly jeopardizes understanding of tumor heterogeneity including its metabolic aspects.

Deeper analysis of the 147 clinical studies mentioned in the meta-analysis by van Kuijk and colleagues revealed some general weak points frequently occurring in multiple clinical studies, e.g., insufficient description of antibody (clone name, source, dilution) and staining procedure (antigen retrieval, staining kit, positive/negative control), and tissue selection (whole tissue block vs TMA). As shown in Table 2, reevaluation of these studies with respect to their reliability and reproducibility using a “reproducibility index” (RI) based on inspection of the antibody properties and staining methodology showed remarkable discrepancies with an established Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) (which was used by van Kuijk and colleagues) [100, 179]. The traditional NOS evaluation system puts emphasis on the scoring methodology, the cohort characteristics, and the disease outcome, while it ignores the abovementioned important aspects of IHC studies, such as precise description of antibody, type of tissue specimen, and details of staining procedure. This can significantly impact on the interpretation of data and ultimately affect their translation to clinical side.

5 Conclusion

Understanding physiological and molecular mechanisms of cancer metabolic plasticity requires not only technologically advanced high-throughput metabolomic, proteomic, and genomic approaches, but also classical methods of molecular and cellular biology. The latter approaches have already uncovered spectrum of molecules and pathways driving metabolic reprogramming that facilitates survival and proliferation of cancer cells in the process of tumor tissue growth as well as during metastatic dissemination. These molecules include metabolic enzymes, transporters, and regulators that often display highly heterogeneous expression pattern reflecting dynamically changing selection-adaptation forces in tumor microenvironment. Using the example of CA IX, we provide a basic insight into the interplay of these molecules. Through the validation of CA IX-specific antibodies, we explain that well-characterized research tools/materials and sufficient technical details are important prerequisites for acquisition of reliable/reproducible data and for building of new knowledge translatable from bench to bedside.

Abbreviations

- AAT:

-

Amino acid transporter

- AE:

-

Anion exchanger

- CA IX:

-

Carbonic anhydrase IX

- CCRCC:

-

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma

- DSF:

-

Disease-free survival

- ECD:

-

Extracellular domain

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FACS:

-

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- FL:

-

Full length

- GLUT:

-

Glucose transporter

- HIF:

-

Hypoxia-inducible factor

- HRE:

-

Hypoxia-responsive element

- IC:

-

Intracytoplasmic

- IF:

-

Immunofluorescence

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MCT:

-

Monocarboxylate transporter

- NBC:

-

Sodium bicarbonate cotransporter

- NHE:

-

Sodium-proton exchanger

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- OXPHOS:

-

Oxidative phosphorylation

- PDK:

-

Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PG:

-

Proteoglycan

- RI:

-

Reproducibility index

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- TCA:

-

Tricarboxylic acid

- TM:

-

Transmembrane

- TME:

-

Tumor microenvironment

- WB:

-

Western blotting

References

Vander Heiden, M. G., Cantley, L. C., & Thompson, C. B. (2009). Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science, 324(5930), 1029–1033. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1160809

Levine, A. J., & Puzio-Kuter, A. M. (2010). The control of the metabolic switch in cancers by oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Science, 330(6009), 1340–1344. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1193494

Nagarajan, A., Malvi, P., & Wajapeyee, N. (2016). Oncogene-directed alterations in cancer cell metabolism. Trends Cancer, 2(7), 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2016.06.002

Hsieh, A. L., Walton, Z. E., Altman, B. J., Stine, Z. E., & Dang, C. V. (2015). MYC and metabolism on the path to cancer. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 43, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.08.003

Mukhopadhyay, S., Vander Heiden, M. G., & McCormick, F. (2021). The metabolic landscape of RAS-driven cancers from biology to therapy. Nat Cancer, 2(3), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-021-00184-x

Schulze, A., & Harris, A. L. (2012). How cancer metabolism is tuned for proliferation and vulnerable to disruption. Nature, 491(7424), 364–373. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11706

Sciacovelli, M., & Frezza, C. (2016). Oncometabolites: Unconventional triggers of oncogenic signalling cascades. Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 100, 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.025

Schmidt, C., Sciacovelli, M., & Frezza, C. (2020). Fumarate hydratase in cancer: A multifaceted tumour suppressor. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 98, 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2019.05.002

Lloyd, M. C., Cunningham, J. J., Bui, M. M., Gillies, R. J., Brown, J. S., & Gatenby, R. A. (2016). Darwinian dynamics of intratumoral heterogeneity: Not solely random mutations but also variable environmental selection forces. Cancer Research, 76(11), 3136–3144. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2962

Gillies, R. J., Brown, J. S., Anderson, A. R. A., & Gatenby, R. A. (2018). Eco-evolutionary causes and consequences of temporal changes in intratumoural blood flow. Nature Reviews Cancer, 18(9), 576–585. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-018-0030-7

Elia, I., & Haigis, M. C. (2021). Metabolites and the tumour microenvironment: From cellular mechanisms to systemic metabolism. Nature Metabolism, 3(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-020-00317-z

Harris, A. L. (2002). Hypoxia–A key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2(1), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc704

Ratcliffe, P. J. (2013). Oxygen sensing and hypoxia signalling pathways in animals: The implications of physiology for cancer. Journal of Physiology, 591(8), 2027–2042. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2013.251470

Semenza, G. L. (2012). Hypoxia-inducible factors: Mediators of cancer progression and targets for cancer therapy. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 33(4), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2012.01.005

Wouters, B. G., & Koritzinsky, M. (2008). Hypoxia signalling through mTOR and the unfolded protein response in cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer, 8(11), 851–864. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2501

Sebestyen, A., Kopper, L., Danko, T., & Timar, J. (2021). Hypoxia signaling in cancer: From basics to clinical practice. Pathology Oncology Research, 27, 1609802. https://doi.org/10.3389/pore.2021.1609802

Li, F., & Simon, M. C. (2020). Cancer cells don’t live alone: Metabolic communication within tumor microenvironments. Developmental Cell, 54(2), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2020.06.018

Corbet, C., & Feron, O. (2017). Tumour acidosis: From the passenger to the driver’s seat. Nature Reviews Cancer, 17(10), 577–593. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2017.77

Sonveaux, P., Vegran, F., Schroeder, T., Wergin, M. C., Verrax, J., Rabbani, Z. N., et al. (2008). Targeting lactate-fueled respiration selectively kills hypoxic tumor cells in mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 118(12), 3930–3942. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI36843

Payen, V. L., Mina, E., Van Hee, V. F., Porporato, P. E., & Sonveaux, P. (2020). Monocarboxylate transporters in cancer. Mol Metab, 33, 48–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2019.07.006

Swietach, P. (2019). What is pH regulation, and why do cancer cells need it? Cancer and Metastasis Reviews, 38(1–2), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-018-09778-x

Wojtkowiak, J. W., Verduzco, D., Schramm, K. J., & Gillies, R. J. (2011). Drug resistance and cellular adaptation to tumor acidic pH microenvironment. Molecular Pharmaceutics, 8(6), 2032–2038. https://doi.org/10.1021/mp200292c

Schonichen, A., Webb, B. A., Jacobson, M. P., & Barber, D. L. (2013). Considering protonation as a posttranslational modification regulating protein structure and function. Annual Review of Biophysics, 42, 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102349

Dixon, S. J., Lemberg, K. M., Lamprecht, M. R., Skouta, R., Zaitsev, E. M., Gleason, C. E., et al. (2012). Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell, 149(5), 1060–1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042

Chafe, S. C., Vizeacoumar, F. S., Venkateswaran, G., Nemirovsky, O., Awrey, S., Brown, W. S., et al. (2021). Genome-wide synthetic lethal screen unveils novel CAIX-NFS1/xCT axis as a targetable vulnerability in hypoxic solid tumors. Sci Adv, 7(35). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abj0364.

Korenchan, D. E., & Flavell, R. R. (2019). Spatiotemporal pH heterogeneity as a promoter of cancer progression and therapeutic resistance. Cancers (Basel), 11(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11071026.

Mason, J. A., Hagel, K. R., Hawk, M. A., & Schafer, Z. T. (2017). Metabolism during ECM detachment: Achilles heel of cancer cells? Trends Cancer, 3(7), 475–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2017.04.009

Sciacovelli, M., & Frezza, C. (2017). Metabolic reprogramming and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cancer. FEBS Journal, 284(19), 3132–3144. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.14090

Mosier, J. A., Schwager, S. C., Boyajian, D. A., & Reinhart-King, C. A. (2021). Cancer cell metabolic plasticity in migration and metastasis. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis, 38(4), 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-021-10102-1

Chen, Y., McAndrews, K. M., & Kalluri, R. (2021). Clinical and therapeutic relevance of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nature Reviews. Clinical Oncology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-021-00546-5

Fiaschi, T., Marini, A., Giannoni, E., Taddei, M. L., Gandellini, P., De Donatis, A., et al. (2012). Reciprocal metabolic reprogramming through lactate shuttle coordinately influences tumor-stroma interplay. Cancer Research, 72(19), 5130–5140. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1949

Hulikova, A., & Swietach, P. (2014). Rapid CO2 permeation across biological membranes: Implications for CO2 venting from tissue. The FASEB Journal, 28(7), 2762–2774. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.13-241752

Rohani, N., Hao, L., Alexis, M. S., Joughin, B. A., Krismer, K., Moufarrej, M. N., et al. (2019). Acidification of tumor at stromal boundaries drives transcriptome alterations associated with aggressive phenotypes. Cancer Research, 79(8), 1952–1966. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1604

Chiche, J., Brahimi-Horn, M. C., & Pouyssegur, J. (2010). Tumour hypoxia induces a metabolic shift causing acidosis: A common feature in cancer. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 14(4), 771–794. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00994.x

Reshkin, S. J., Greco, M. R., & Cardone, R. A. (2014). Role of pHi, and proton transporters in oncogene-driven neoplastic transformation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 369(1638), 20130100. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0100

Parks, S. K., Chiche, J., & Pouyssegur, J. (2011). pH control mechanisms of tumor survival and growth. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 226(2), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.22400

Fang, J. S., Gillies, R. D., & Gatenby, R. A. (2008). Adaptation to hypoxia and acidosis in carcinogenesis and tumor progression. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 18(5), 330–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.011

Gillies, R. J. (2021). Cancer heterogeneity and metastasis: Life at the edge. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-021-10101-2

Pastorek, J., Pastorekova, S., Callebaut, I., Mornon, J. P., Zelnik, V., Opavsky, R., et al. (1994). Cloning and characterization of MN, a human tumor-associated protein with a domain homologous to carbonic anhydrase and a putative helix-loop-helix DNA binding segment. Oncogene, 9(10), 2877–2888.

Opavsky, R., Pastorekova, S., Zelnik, V., Gibadulinova, A., Stanbridge, E. J., Zavada, J., et al. (1996). Human MN/CA9 gene, a novel member of the carbonic anhydrase family: Structure and exon to protein domain relationships. Genomics, 33(3), 480–487. https://doi.org/10.1006/geno.1996.0223

Innocenti, A., Pastorekova, S., Pastorek, J., Scozzafava, A., De Simone, G., & Supuran, C. T. (2009). The proteoglycan region of the tumor-associated carbonic anhydrase isoform IX acts as anintrinsic buffer optimizing CO2 hydration at acidic pH values characteristic of solid tumors. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 19(20), 5825–5828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.08.088

Mahon, B. P., Bhatt, A., Socorro, L., Driscoll, J. M., Okoh, C., Lomelino, C. L., et al. (2016). The structure of carbonic anhydrase IX is adapted for low-pH catalysis. Biochemistry, 55(33), 4642–4653. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00243

Wykoff, C. C., Beasley, N. J., Watson, P. H., Turner, K. J., Pastorek, J., Sibtain, A., et al. (2000). Hypoxia-inducible expression of tumor-associated carbonic anhydrases. Cancer Research, 60(24), 7075–7083.

Ditte, P., Dequiedt, F., Svastova, E., Hulikova, A., Ohradanova-Repic, A., Zatovicova, M., et al. (2011). Phosphorylation of carbonic anhydrase IX controls its ability to mediate extracellular acidification in hypoxic tumors. Cancer Research, 71(24), 7558–7567. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2520

McDonald, P. C., Chafe, S. C., Brown, W. S., Saberi, S., Swayampakula, M., Venkateswaran, G., et al. (2019). Regulation of pH by carbonic anhydrase 9 mediates survival of pancreatic cancer cells with activated KRAS in response to hypoxia. Gastroenterology, 157(3), 823–837. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.004

Takacova, M., Holotnakova, T., Barathova, M., Pastorekova, S., Kopacek, J., & Pastorek, J. (2010). Src induces expression of carbonic anhydrase IX via hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Oncology Reports, 23(3), 869–874.

Takacova, M., Bullova, P., Simko, V., Skvarkova, L., Poturnajova, M., Feketeova, L., et al. (2014). Expression pattern of carbonic anhydrase IX in Medullary thyroid carcinoma supports a role for RET-mediated activation of the HIF pathway. American Journal of Pathology, 184(4), 953–965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.01.002

Panisova, E., Kery, M., Sedlakova, O., Brisson, L., Debreova, M., Sboarina, M., et al. (2017). Lactate stimulates CA IX expression in normoxic cancer cells. Oncotarget, 8(44), 77819–77835. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.20836

Kappler, M., Pabst, U., Weinholdt, C., Taubert, H., Rot, S., Kaune, T., et al. (2019). Causes and consequences of a glutamine induced normoxic HIF1 Activity for the tumor metabolism. Int J Mol Sci, 20(19). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20194742.

Svastova, E., Hulikova, A., Rafajova, M., Zat’ovicova, M., Gibadulinova, A., Casini, A., et al. (2004). Hypoxia activates the capacity of tumor-associated carbonic anhydrase IX to acidify extracellular pH. FEBS Letters, 577(3), 439–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.043

Swietach, P., Patiar, S., Supuran, C. T., Harris, A. L., & Vaughan-Jones, R. D. (2009). The role of carbonic anhydrase 9 in regulating extracellular and intracellular ph in three-dimensional tumor cell growths. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 284(30), 20299–20310. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.006478

Lee, S. H., McIntyre, D., Honess, D., Hulikova, A., Pacheco-Torres, J., Cerdan, S., et al. (2018). Carbonic anhydrase IX is a pH-stat that sets an acidic tumour extracellular pH in vivo. British Journal of Cancer, 119(5), 622–630. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0216-5

Morgan, P. E., Pastorekova, S., Stuart-Tilley, A. K., Alper, S. L., & Casey, J. R. (2007). Interactions of transmembrane carbonic anhydrase, CAIX, with bicarbonate transporters. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology, 293(2), C738-748. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00157.2007

Svastova, E., Witarski, W., Csaderova, L., Kosik, I., Skvarkova, L., Hulikova, A., et al. (2012). Carbonic anhydrase IX interacts with bicarbonate transporters in lamellipodia and increases cell migration via its catalytic domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 287(5), 3392–3402. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.286062

Orlowski, A., De Giusti, V. C., Morgan, P. E., Aiello, E. A., & Alvarez, B. V. (2012). Binding of carbonic anhydrase IX to extracellular loop 4 of the NBCe1 Na+/HCO3- cotransporter enhances NBCe1-mediated HCO3- influx in the rat heart. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology, 303(1), C69-80. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00431.2011

Jamali, S., Klier, M., Ames, S., Barros, L. F., McKenna, R., Deitmer, J. W., et al. (2015). Hypoxia-induced carbonic anhydrase IX facilitates lactate flux in human breast cancer cells by non-catalytic function. Science and Reports, 5, 13605. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13605

Ames, S., Pastorekova, S., & Becker, H. M. (2018). The proteoglycan-like domain of carbonic anhydrase IX mediates non-catalytic facilitation of lactate transport in cancer cells. Oncotarget, 9(46), 27940–27957. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.25371

Ames, S., Andring, J. T., McKenna, R., & Becker, H. M. (2019). CAIX forms a transport metabolon with monocarboxylate transporters in human breast cancer cells. Oncogene. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-019-1098-6

Liskova, V., Hudecova, S., Lencesova, L., Iuliano, F., Sirova, M., Ondrias, K., et al. (2019). Type 1 sodium calcium exchanger forms a complex with carbonic anhydrase IX and via reverse mode activity contributes to pH control in hypoxic tumors. Cancers (Basel), 11(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11081139.

Chafe, S. C., McDonald, P. C., Saberi, S., Nemirovsky, O., Venkateswaran, G., Burugu, S., et al. (2019). Targeting hypoxia-induced carbonic anhydrase IX enhances immune-checkpoint blockade locally and systemically. Cancer Immunology Research, 7(7), 1064–1078. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0657

Chiche, J., Ilc, K., Laferriere, J., Trottier, E., Dayan, F., Mazure, N. M., et al. (2009). Hypoxia-inducible carbonic anhydrase IX and XII promote tumor cell growth by counteracting acidosis through the regulation of the intracellular pH. Cancer Research, 69(1), 358–368. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2470

McIntyre, A., Hulikova, A., Ledaki, I., Snell, C., Singleton, D., Steers, G., et al. (2016). Disrupting hypoxia-induced bicarbonate transport acidifies tumor cells and suppresses tumor growth. Cancer Research, 76(13), 3744–3755. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1862

Parks, S. K., Cormerais, Y., Durivault, J., & Pouyssegur, J. (2017). Genetic disruption of the pHi-regulating proteins Na+/H+ exchanger 1 (SLC9A1) and carbonic anhydrase 9 severely reduces growth of colon cancer cells. Oncotarget, 8(6), 10225–10237. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.14379

Pacchiano, F., Carta, F., McDonald, P. C., Lou, Y., Vullo, D., Scozzafava, A., et al. (2011). Ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamides potently inhibit carbonic anhydrase IX and show antimetastatic activity in a model of breast cancer metastasis. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 54(6), 1896–1902. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm101541x

Lock, F. E., McDonald, P. C., Lou, Y., Serrano, I., Chafe, S. C., Ostlund, C., et al. (2013). Targeting carbonic anhydrase IX depletes breast cancer stem cells within the hypoxic niche. Oncogene, 32(44), 5210–5219. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2012.550

Ledaki, I., McIntyre, A., Wigfield, S., Buffa, F., McGowan, S., Baban, D., et al. (2015). Carbonic anhydrase IX induction defines a heterogeneous cancer cell response to hypoxia and mediates stem cell-like properties and sensitivity to HDAC inhibition. Oncotarget, 6(23), 19413–19427. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.4989

Neri, D., & Supuran, C. T. (2011). Interfering with pH regulation in tumours as a therapeutic strategy. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 10(10), 767–777. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3554

Pastorek, J., & Pastorekova, S. (2015). Hypoxia-induced carbonic anhydrase IX as a target for cancer therapy: From biology to clinical use. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 31, 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.08.002

Strapcova, S., Takacova, M., Csaderova, L., Martinelli, P., Lukacikova, L., Gal, V., et al. (2020). Clinical and pre-clinical evidence of carbonic anhydrase IX in pancreatic cancer and its high expression in pre-cancerous lesions. Cancers (Basel), 12(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12082005.

Kery, M., Oravcova, N., Radenkovic, S., Iuliano, F., Tomaskova, J., & Golias, T. (2018). Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 and carbonic anhydrase IX targeting in hypoxic tumors. Neoplasma, 66(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.4149/neo_2018_180531N357

Gibadulinova, A., Bullova, P., Strnad, H., Pohlodek, K., Jurkovicova, D., Takacova, M., et al. (2020). CAIX-mediated control of LIN28/let-7 axis contributes to metabolic adaptation of breast cancer cells to hypoxia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21124299

Benej, M., Svastova, E., Banova, R., Kopacek, J., Gibadulinova, A., Kery, M., et al. (2020). CA IX stabilizes intracellular pH to maintain metabolic reprogramming and proliferation in hypoxia. Frontiers in Oncology, 10, 1462. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.01462

Becker, H. M. (2020). Carbonic anhydrase IX and acid transport in cancer. British Journal of Cancer, 122(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-019-0642-z

Harguindey, S., Arranz, J. L., Polo Orozco, J. D., Rauch, C., Fais, S., Cardone, R. A., et al. (2013). Cariporide and other new and powerful NHE1 inhibitors as potentially selective anticancer drugs–An integral molecular/biochemical/metabolic/clinical approach after one hundred years of cancer research. Journal of Translational Medicine, 11, 282. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-11-282

Lamonte, G., Tang, X., Chen, J. L., Wu, J., Ding, C. K., Keenan, M. M., et al. (2013). Acidosis induces reprogramming of cellular metabolism to mitigate oxidative stress. Cancer Metab, 1(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-3002-1-23

Svastova, E., & Pastorekova, S. (2013). Carbonic anhydrase IX: A hypoxia-controlled “catalyst” of cell migration. Cell Adhesion & Migration, 7(2), 226–231. https://doi.org/10.4161/cam.23257

McDonald, P. C., Swayampakula, M., & Dedhar, S. (2018). Coordinated regulation of metabolic transporters and migration/invasion by carbonic anhydrase IX. Metabolites, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo8010020.

Csaderova, L., Debreova, M., Radvak, P., Stano, M., Vrestiakova, M., Kopacek, J., et al. (2013). The effect of carbonic anhydrase IX on focal contacts during cell spreading and migration. Frontiers in Physiology, 4, 271. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2013.00271

Radvak, P., Repic, M., Svastova, E., Takacova, M., Csaderova, L., Strnad, H., et al. (2013). Suppression of carbonic anhydrase IX leads to aberrant focal adhesion and decreased invasion of tumor cells. Oncology Reports, 29(3), 1147–1153. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2013.2226

Svastova, E., Zilka, N., Zat’ovicova, M., Gibadulinova, A., Ciampor, F., Pastorek, J., et al. (2003). Carbonic anhydrase IX reduces E-cadherin-mediated adhesion of MDCK cells via interaction with beta-catenin. Experimental Cell Research, 290(2), 332–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00351-3

Debreova, M., Csaderova, L., Burikova, M., Lukacikova, L., Kajanova, I., Sedlakova, O., et al. (2019). CAIX regulates invadopodia formation through both a pH-dependent mechanism and interplay with actin regulatory proteins. Int J Mol Sci, 20(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20112745.

Swayampakula, M., McDonald, P. C., Vallejo, M., Coyaud, E., Chafe, S. C., Westerback, A., et al. (2017). The interactome of metabolic enzyme carbonic anhydrase IX reveals novel roles in tumor cell migration and invadopodia/MMP14-mediated invasion. Oncogene, 36(45), 6244–6261. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2017.219

Venkateswaran, G., & Dedhar, S. (2020). Interplay of carbonic anhydrase IX with amino acid and acid/base transporters in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment. Front Cell Dev Biol, 8, 602668. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2020.602668

Stock, C., & Schwab, A. (2009). Protons make tumor cells move like clockwork. Pflugers Archiv. European Journal of Physiology, 458(5), 981–992. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-009-0677-8

LeBleu, V. S., O'Connell, J. T., Gonzalez Herrera, K. N., Wikman, H., Pantel, K., Haigis, M. C., et al. (2014). PGC-1alpha mediates mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation in cancer cells to promote metastasis. Nat Cell Biol, 16(10), 992–1003, 1001–1015. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb3039.

Jiang, L., Xiao, L., Sugiura, H., Huang, X., Ali, A., Kuro-o, M., et al. (2015). Metabolic reprogramming during TGFbeta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene, 34(30), 3908–3916. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2014.321

Hui, E. P., Chan, A. T., Pezzella, F., Turley, H., To, K. F., Poon, T. C., et al. (2002). Coexpression of hypoxia-inducible factors 1alpha and 2alpha, carbonic anhydrase IX, and vascular endothelial growth factor in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and relationship to survival. Clinical Cancer Research, 8(8), 2595–2604.

Tomes, L., Emberley, E., Niu, Y., Troup, S., Pastorek, J., Strange, K., et al. (2003). Necrosis and hypoxia in invasive breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 81(1), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025476722493

Rademakers, S. E., Lok, J., van der Kogel, A. J., Bussink, J., & Kaanders, J. H. (2011). Metabolic markers in relation to hypoxia; Staining patterns and colocalization of pimonidazole, HIF-1alpha, CAIX, LDH-5, GLUT-1, MCT1 and MCT4. BMC Cancer, 11, 167. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-11-167

Mayer, A., Schneider, F., Vaupel, P., Sommer, C., & Schmidberger, H. (2012). Differential expression of HIF-1 in glioblastoma multiforme and anaplastic astrocytoma. International Journal of Oncology, 41(4), 1260–1270. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2012.1555

Rohan, S. M., Xiao, Y., Liang, Y., Dudas, M. E., Al-Ahmadie, H. A., Fine, S. W., et al. (2011). Clear-cell papillary renal cell carcinoma: Molecular and immunohistochemical analysis with emphasis on the von Hippel-Lindau gene and hypoxia-inducible factor pathway-related proteins. Modern Pathology, 24(9), 1207–1220. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2011.80

Ord, J. J., Streeter, E. H., Roberts, I. S., Cranston, D., & Harris, A. L. (2005). Comparison of hypoxia transcriptome in vitro with in vivo gene expression in human bladder cancer. British Journal of Cancer, 93(3), 346–354. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602666

Airley, R. E., Loncaster, J., Raleigh, J. A., Harris, A. L., Davidson, S. E., Hunter, R. D., et al. (2003). GLUT-1 and CAIX as intrinsic markers of hypoxia in carcinoma of the cervix: Relationship to pimonidazole binding. International Journal of Cancer, 104(1), 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.10904

Dooms, C., van Baardwijk, A., Verbeken, E., van Suylen, R. J., Stroobants, S., De Ruysscher, D., et al. (2009). Association between 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose uptake values and tumor vitality: Prognostic value of positron emission tomography in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology, 4(7), 822–828. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a97df7

Koukourakis, M. I., Pitiakoudis, M., Giatromanolaki, A., Tsarouha, A., Polychronidis, A., Sivridis, E., et al. (2006). Oxygen and glucose consumption in gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas: Correlation with markers of hypoxia, acidity and anaerobic glycolysis. Cancer Science, 97(10), 1056–1060. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00298.x

Schmidt, D. R., Patel, R., Kirsch, D. G., Lewis, C. A., Vander Heiden, M. G., & Locasale, J. W. (2021). Metabolomics in cancer research and emerging applications in clinical oncology. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(4), 333–358. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21670

Muir, A., Danai, L. V., & Vander Heiden, M. G. (2018). Microenvironmental regulation of cancer cell metabolism: implications for experimental design and translational studies. Dis Model Mech, 11(8). https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.035758.

Bjorling, E., & Uhlen, M. (2008). Antibodypedia, a portal for sharing antibody and antigen validation data. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics, 7(10), 2028–2037. https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.M800264-MCP200

Helsby, M. A., Leader, P. M., Fenn, J. R., Gulsen, T., Bryant, C., Doughton, G., et al. (2014). CiteAb: A searchable antibody database that ranks antibodies by the number of times they have been cited. BMC Cell Biology, 15, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2121-15-6

van Kuijk, S. J., Yaromina, A., Houben, R., Niemans, R., Lambin, P., & Dubois, L. J. (2016). Prognostic significance of carbonic anhydrase IX expression in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Oncology, 6, 69. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2016.00069

Weller, M. G. (2018). Ten Basic Rules of Antibody Validation. Analytical Chemistry Insights, 13, 1177390118757462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177390118757462

Dungwa, J. V., Hunt, L. P., & Ramani, P. (2012). Carbonic anhydrase IX up-regulation is associated with adverse clinicopathologic and biologic factors in neuroblastomas. Human Pathology, 43(10), 1651–1660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2011.12.006

Korkolopoulou, P., Perdiki, M., Thymara, I., Boviatsis, E., Agrogiannis, G., Kotsiakis, X., et al. (2007). Expression of hypoxia-related tissue factors in astrocytic gliomas. A multivariate survival study with emphasis upon carbonic anhydrase IX. Hum Pathol, 38(4), 629–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2006.07.020

Ameis, H. M., Drenckhan, A., Freytag, M., Izbicki, J. R., Supuran, C. T., Reinshagen, K., et al. (2016). Carbonic anhydrase IX correlates with survival and is a potential therapeutic target for neuroblastoma. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry, 31(3), 404–409. https://doi.org/10.3109/14756366.2015.1029471

Jarvela, S., Parkkila, S., Bragge, H., Kahkonen, M., Parkkila, A. K., Soini, Y., et al. (2008). Carbonic anhydrase IX in oligodendroglial brain tumors. BMC Cancer, 8, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-8-1

Nordfors, K., Haapasalo, J., Korja, M., Niemela, A., Laine, J., Parkkila, A. K., et al. (2010). The tumour-associated carbonic anhydrases CA II, CA IX and CA XII in a group of medulloblastomas and supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumours: An association of CA IX with poor prognosis. BMC Cancer, 10, 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-148

Haapasalo, J. A., Nordfors, K. M., Hilvo, M., Rantala, I. J., Soini, Y., Parkkila, A. K., et al. (2006). Expression of carbonic anhydrase IX in astrocytic tumors predicts poor prognosis. Clinical Cancer Research, 12(2), 473–477. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0848

Erpolat, O. P., Gocun, P. U., Akmansu, M., Ozgun, G., & Akyol, G. (2013). Hypoxia-related molecules HIF-1alpha, CA9, and osteopontin: Predictors of survival in patients with high-grade glioma. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie, 189(2), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-012-0262-5

Proescholdt, M. A., Merrill, M. J., Stoerr, E. M., Lohmeier, A., Pohl, F., & Brawanski, A. (2012). Function of carbonic anhydrase IX in glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro-Oncology, 14(11), 1357–1366. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nos216

Yoo, H., Sohn, S., Nam, B. H., Min, H. S., Jung, E., Shin, S. H., et al. (2010). The expressions of carbonic anhydrase 9 and vascular endothelial growth factor in astrocytic tumors predict a poor prognosis. International Journal of Molecular Medicine, 26(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm_00000427

Abraham, S., Hu, N., & Jensen, R. (2012). Hypoxia-inducible factor-1-regulated protein expression and oligodendroglioma patient outcome: Comparison with established biomarkers and preoperative UCSF low-grade scoring system. Journal of Neuro-oncology, 108(3), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-012-0839-y

Jensen, R., & Lee, J. (2012). Predicting outcomes of patients with intracranial meningiomas using molecular markers of hypoxia, vascularity, and proliferation. Neurosurgery, 71(1), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182567886

Sooman, L., Freyhult, E., Jaiswal, A., Navani, S., Edqvist, P. H., Ponten, F., et al. (2015). FGF2 as a potential prognostic biomarker for proneural glioma patients. Acta Oncologica, 54(3), 385–394. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2014.951492

Flynn, J. R., Wang, L., Gillespie, D. L., Stoddard, G. J., Reid, J. K., Owens, J., et al. (2008). Hypoxia-regulated protein expression, patient characteristics, and preoperative imaging as predictors of survival in adults with glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer, 113(5), 1032–1042. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23678

Preusser, M., Wolfsberger, S., Haberler, C., Breitschopf, H., Czech, T., Slavc, I., et al. (2005). Vascularization and expression of hypoxia-related tissue factors in intracranial ependymoma and their impact on patient survival. Acta Neuropathologica, 109(2), 211–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-004-0938-8

Couvelard, A., O’Toole, D., Turley, H., Leek, R., Sauvanet, A., Degott, C., et al. (2005). Microvascular density and hypoxia-inducible factor pathway in pancreatic endocrine tumours: Negative correlation of microvascular density and VEGF expression with tumour progression. British Journal of Cancer, 92(1), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602245

Couvelard, A., O’Toole, D., Leek, R., Turley, H., Sauvanet, A., Degott, C., et al. (2005). Expression of hypoxia-inducible factors is correlated with the presence of a fibrotic focus and angiogenesis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. Histopathology, 46(6), 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02160.x

Chang, D. T., Chapman, C. H., Norton, J. A., Visser, B., Fisher, G. A., Kunz, P., et al. (2010). Expression of p16(INK4A) but not hypoxia markers or poly adenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase is associated with improved survival in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer, 116(22), 5179–5187. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25481

Hiraoka, N., Ino, Y., Sekine, S., Tsuda, H., Shimada, K., Kosuge, T., et al. (2010). Tumour necrosis is a postoperative prognostic marker for pancreatic cancer patients with a high interobserver reproducibility in histological evaluation. British Journal of Cancer, 103(7), 1057–1065. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605854

Li, Y., Dong, M., Sheng, W., & Huang, L. (2016). Roles of carbonic anhydrase IX in development of pancreatic cancer. Pathology Oncology Research, 22(2), 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12253-015-9935-6

Schmitt, A. M., Schmid, S., Rudolph, T., Anlauf, M., Prinz, C., Kloppel, G., et al. (2009). VHL inactivation is an important pathway for the development of malignant sporadic pancreatic endocrine tumors. Endocrine-Related Cancer, 16(4), 1219–1227. https://doi.org/10.1677/ERC-08-0297

Yu, M., Zhou, Q., Zhou, Y., Fu, Z., Tan, L., Ye, X., et al. (2015). Metabolic phenotypes in pancreatic cancer. PLoS ONE, 10(2), e0115153. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115153

Trastour, C., Benizri, E., Ettore, F., Ramaioli, A., Chamorey, E., Pouyssegur, J., et al. (2007). HIF-1alpha and CA IX staining in invasive breast carcinomas: Prognosis and treatment outcome. International Journal of Cancer, 120(7), 1451–1458. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.22436

Hussain, S. A., Ganesan, R., Reynolds, G., Gross, L., Stevens, A., Pastorek, J., et al. (2007). Hypoxia-regulated carbonic anhydrase IX expression is associated with poor survival in patients with invasive breast cancer. British Journal of Cancer, 96(1), 104–109. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603530

Betof, A. S., Rabbani, Z. N., Hardee, M. E., Kim, S. J., Broadwater, G., Bentley, R. C., et al. (2012). Carbonic anhydrase IX is a predictive marker of doxorubicin resistance in early-stage breast cancer independent of HER2 and TOP2A amplification. British Journal of Cancer, 106(5), 916–922. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.32

Aomatsu, N., Yashiro, M., Kashiwagi, S., Kawajiri, H., Takashima, T., Ohsawa, M., et al. (2014). Carbonic anhydrase 9 is associated with chemosensitivity and prognosis in breast cancer patients treated with taxane and anthracycline. BMC Cancer, 14, 400. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-400

Lou, Y., McDonald, P. C., Oloumi, A., Chia, S., Ostlund, C., Ahmadi, A., et al. (2011). Targeting tumor hypoxia: Suppression of breast tumor growth and metastasis by novel carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors. Cancer Research, 71(9), 3364–3376. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4261

Tan, E. Y., Yan, M., Campo, L., Han, C., Takano, E., Turley, H., et al. (2009). The key hypoxia regulated gene CAIX is upregulated in basal-like breast tumours and is associated with resistance to chemotherapy. British Journal of Cancer, 100(2), 405–411. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604844

Brennan, D. J., Jirstrom, K., Kronblad, A., Millikan, R. C., Landberg, G., Duffy, M. J., et al. (2006). CA IX is an independent prognostic marker in premenopausal breast cancer patients with one to three positive lymph nodes and a putative marker of radiation resistance. Clinical Cancer Research, 12(21), 6421–6431. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0480

Generali, D., Fox, S. B., Berruti, A., Brizzi, M. P., Campo, L., Bonardi, S., et al. (2006). Role of carbonic anhydrase IX expression in prediction of the efficacy and outcome of primary epirubicin/tamoxifen therapy for breast cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer, 13(3), 921–930. https://doi.org/10.1677/erc.1.01216

Kyndi, M., Sorensen, F. B., Knudsen, H., Alsner, J., Overgaard, M., Nielsen, H. M., et al. (2008). Carbonic anhydrase IX and response to postmastectomy radiotherapy in high-risk breast cancer: A subgroup analysis of the DBCG82 b and c trials. Breast Cancer Research, 10(2), R24. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr1981

Neumeister, V. M., Sullivan, C. A., Lindner, R., Lezon-Geyda, K., Li, J., Zavada, J., et al. (2012). Hypoxia-induced protein CAIX is associated with somatic loss of BRCA1 protein and pathway activity in triple negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 136(1), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-012-2232-0

Doyen, J., Trastour, C., Ettore, F., Peyrottes, I., Toussant, N., Gal, J., et al. (2014). Expression of the hypoxia-inducible monocarboxylate transporter MCT4 is increased in triple negative breast cancer and correlates independently with clinical outcome. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 451(1), 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.07.050

Pinheiro, C., Sousa, B., Albergaria, A., Paredes, J., Dufloth, R., Vieira, D., et al. (2011). GLUT1 and CAIX expression profiles in breast cancer correlate with adverse prognostic factors and MCT1 overexpression. Histology and Histopathology, 26(10), 1279–1286. https://doi.org/10.14670/HH-26.1279

Garcia, S., Dales, J. P., Charafe-Jauffret, E., Carpentier-Meunier, S., Andrac-Meyer, L., Jacquemier, J., et al. (2007). Poor prognosis in breast carcinomas correlates with increased expression of targetable CD146 and c-Met and with proteomic basal-like phenotype. Human Pathology, 38(6), 830–841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2006.11.015

Bane, A. L., Whelan, T. J., Pond, G. R., Parpia, S., Gohla, G., Fyles, A. W., et al. (2014). Tumor factors predictive of response to hypofractionated radiotherapy in a randomized trial following breast conserving therapy. Annals of Oncology, 25(5), 992–998. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu090

Kim, H. M., Jung, W. H., & Koo, J. S. (2014). Site-specific metabolic phenotypes in metastatic breast cancer. Journal of Translational Medicine, 12, 354. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-014-0354-3

Lancashire, L. J., Powe, D. G., Reis-Filho, J. S., Rakha, E., Lemetre, C., Weigelt, B., et al. (2010). A validated gene expression profile for detecting clinical outcome in breast cancer using artificial neural networks. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 120(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-009-0378-1

Kornegoor, R., Verschuur-Maes, A. H., Buerger, H., Hogenes, M. C., de Bruin, P. C., Oudejans, J. J., et al. (2012). Fibrotic focus and hypoxia in male breast cancer. Modern Pathology, 25(10), 1397–1404. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.101

Noh, S., Kim, J. Y., & Koo, J. S. (2014). Metabolic differences in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer based on androgen receptor status. Tumour Biology, 35(8), 8179–8192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-014-2103-x

Currie, M. J., Beardsley, B. E., Harris, G. C., Gunningham, S. P., Dachs, G. U., Dijkstra, B., et al. (2013). Immunohistochemical analysis of cancer stem cell markers in invasive breast carcinoma and associated ductal carcinoma in situ: Relationships with markers of tumor hypoxia and microvascularity. Human Pathology, 44(3), 402–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2012.06.004

Deb, S., Johansson, I., Byrne, D., Nilsson, C., kConFab, I., Constable, L., et al. (2014). Nuclear HIF1A expression is strongly prognostic in sporadic but not familial male breast cancer. Mod Pathol, 27(9), 1223–1230. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.231

Beketic-Oreskovic, L., Ozretic, P., Rabbani, Z. N., Jackson, I. L., Sarcevic, B., Levanat, S., et al. (2011). Prognostic significance of carbonic anhydrase IX (CA-IX), endoglin (CD105) and 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) in breast cancer patients. Pathology Oncology Research, 17(3), 593–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12253-010-9355-6

Kaya, A. O., Gunel, N., Benekli, M., Akyurek, N., Buyukberber, S., Tatli, H., et al. (2012). Hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha and carbonic anhydrase IX overexpression are associated with poor survival in breast cancer patients. Journal of B.U.ON., 17(4), 663–668.

Silva, P., Slevin, N. J., Sloan, P., Valentine, H., Ryder, D., Price, P., et al. (2010). Use of multiple biological markers in radiotherapy-treated head and neck cancer. Journal of Laryngology and Otology, 124(6), 650–658. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215110000228

Koukourakis, M. I., Giatromanolaki, A., Sivridis, E., Simopoulos, K., Pastorek, J., Wykoff, C. C., et al. (2001). Hypoxia-regulated carbonic anhydrase-9 (CA9) relates to poor vascularization and resistance of squamous cell head and neck cancer to chemoradiotherapy. Clinical Cancer Research, 7(11), 3399–3403.

Koukourakis, M. I., Bentzen, S. M., Giatromanolaki, A., Wilson, G. D., Daley, F. M., Saunders, M. I., et al. (2006). Endogenous markers of two separate hypoxia response pathways (hypoxia inducible factor 2 alpha and carbonic anhydrase 9) are associated with radiotherapy failure in head and neck cancer patients recruited in the CHART randomized trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24(5), 727–735. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7474

Bernstein, J. M., Andrews, T. D., Slevin, N. J., West, C. M., & Homer, J. J. (2015). Prognostic value of hypoxia-associated markers in advanced larynx and hypopharynx squamous cell carcinoma. The Laryngoscope, 125(1), E8-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24933

Choi, S. W., Kim, J. Y., Park, J. Y., Cha, I. H., Kim, J., & Lee, S. (2008). Expression of carbonic anhydrase IX is associated with postoperative recurrence and poor prognosis in surgically treated oral squamous cell carcinoma. Human Pathology, 39(9), 1317–1322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2007.10.026

De Schutter, H., Landuyt, W., Verbeken, E., Goethals, L., Hermans, R., & Nuyts, S. (2005). The prognostic value of the hypoxia markers CA IX and GLUT 1 and the cytokines VEGF and IL 6 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated by radiotherapy +/- chemotherapy. BMC Cancer, 5, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-5-42

Douglas, C. M., Bernstein, J. M., Ormston, V. E., Hall, R. C., Merve, A., Swindell, R., et al. (2013). Lack of prognostic effect of carbonic anhydrase-9, hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha and bcl-2 in 286 patients with early squamous cell carcinoma of the glottic larynx treated with radiotherapy. Clinical Oncology (Royal College of Radiologists), 25(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2012.07.004

Heo, K., Kim, Y. H., Sung, H. J., Li, H. Y., Yoo, C. W., Kim, J. Y., et al. (2012). Hypoxia-induced up-regulation of apelin is associated with a poor prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Oral Oncology, 48(6), 500–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.12.015

Kim, S. J., Shin, H. J., Jung, K. Y., Baek, S. K., Shin, B. K., Choi, J., et al. (2007). Prognostic value of carbonic anhydrase IX and Ki-67 expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 37(11), 812–819. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hym121

Perez-Sayans, M., Suarez-Penaranda, J. M., Pilar, G. D., Supuran, C. T., Pastorekova, S., Barros-Angueira, F., et al. (2012). Expression of CA-IX is associated with advanced stage tumors and poor survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Journal of Oral Pathology and Medicine, 41(9), 667–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.2012.01147.x

Wachters, J. E., Schrijvers, M. L., Slagter-Menkema, L., Mastik, M., de Bock, G. H., Langendijk, J. A., et al. (2013). Prognostic significance of HIF-1a, CA-IX, and OPN in T1–T2 laryngeal carcinoma treated with radiotherapy. The Laryngoscope, 123(9), 2154–2160. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.23831

Eriksen, J. G., Overgaard, J., Danish, H., Neck Cancer Study, G. (2007). Lack of prognostic and predictive value of CA IX in radiotherapy of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck with known modifiable hypoxia: An evaluation of the DAHANCA 5 study. Radiother Oncol, 83(3), 383–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2007.05.009

Le, Q. T., Shi, G., Cao, H., Nelson, D. W., Wang, Y., Chen, E. Y., et al. (2005). Galectin-1: A link between tumor hypoxia and tumor immune privilege. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(35), 8932–8941. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0206

Nordsmark, M., Eriksen, J. G., Gebski, V., Alsner, J., Horsman, M. R., & Overgaard, J. (2007). Differential risk assessments from five hypoxia specific assays: The basis for biologically adapted individualized radiotherapy in advanced head and neck cancer patients. Radiotherapy and Oncology, 83(3), 389–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2007.04.021

Winter, S. C., Shah, K. A., Han, C., Campo, L., Turley, H., Leek, R., et al. (2006). The relation between hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha and HIF-2alpha expression with anemia and outcome in surgically treated head and neck cancer. Cancer, 107(4), 757–766. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21983

Koukourakis, M. I., Giatromanolaki, A., Danielidis, V., & Sivridis, E. (2008). Hypoxia inducible factor (HIf1alpha and HIF2alpha) and carbonic anhydrase 9 (CA9) expression and response of head-neck cancer to hypofractionated and accelerated radiotherapy. International Journal of Radiation Biology, 84(1), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/09553000701616114

Kondo, Y., Yoshikawa, K., Omura, Y., Shinohara, A., Kazaoka, Y., Sano, J., et al. (2011). Clinicopathological significance of carbonic anhydrase 9, glucose transporter-1, Ki-67 and p53 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncology Reports, 25(5), 1227–1233. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2011.1216

Brockton, N., Dort, J., Lau, H., Hao, D., Brar, S., Klimowicz, A., et al. (2011). High stromal carbonic anhydrase IX expression is associated with decreased survival in P16-negative head-and-neck tumors. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics, 80(1), 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.059

Brockton, N. T., Klimowicz, A. C., Bose, P., Petrillo, S. K., Konno, M., Rudmik, L., et al. (2012). High stromal carbonic anhydrase IX expression is associated with nodal metastasis and decreased survival in patients with surgically-treated oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncology, 48(7), 615–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.01.018

Zheng, G., Peng, C., Jia, X., Gu, Y., Zhang, Z., Deng, Y., et al. (2015). ZEB1 transcriptionally regulated carbonic anhydrase 9 mediates the chemoresistance of tongue cancer via maintaining intracellular pH. Molecular Cancer, 14, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-015-0357-6

Sakata, K., Someya, M., Nagakura, H., Nakata, K., Oouchi, A., Takagi, M., et al. (2008). Brachytherapy for oral tongue cancer: An analysis of treatment results with various biological markers. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 38(6), 402–407. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyn050