Abstract

Despite the economic, social, and environmental importance of emerging countries, most existing research into ethical consumerism has focused on developed market contexts. We introduce this Special Issue (SI) and provide a comprehensive thematic literature review considering three broad categories or aspects of ethical consumerism research, (1) contexts of ethical consumption, (2) forms of ethical consumerism, and (3) approaches to explaining ethical consumer behavior. We summarize the articles of this SI as part of the thematic literature review to provide an understanding of how these articles and this SI’s overall contribute to ethical consumerism research. Each article in this SI offers new insights into a specific field of ethical consumerism while focusing on emerging market contexts. Overall, this SI expands knowledge related to the dynamics and challenges of ethical consumerism and offers future research directions in this area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The term “ethical consumerism” has been used with different meanings in various business management disciplines (Carrington et al., 2021; Papaoikonomou et al., 2023). For example, earlier, Cooper-Martin and Holbrook (1993, p. 113) defined ethical consumerism in terms of buyer characteristics, namely as “decision-making, purchases and other consumption experiences that are affected by the consumer’s ethical concerns”. Similarly, Summers (2016, p. 303) defines it as “the deliberate purchase, or avoidance, of products for political, ethical, or environmental reasons.” In contrast, Irwin (2015) defined it as a characteristic of firms, notably a broad label for companies providing self-appealing products (e.g., fair-trade coffee or charitable giving). More recently, Papaoikonomou et al., (2023, p. 1) introduced the concept of ethical consumer literacy, referred to as the “consumer's ability to consume in a way that will not have a negative social, animal, or environmental impact”. While these perspectives vary in terms of focus on the consumers or companies, the common thread in these definitions is the agreement on the relationship between consumption and its wider impact on society and environment.

The call for papers (CFP) that we issued in June 2020 for this Special Issue (SI) on “Ethical Consumerism in Emerging Markets: Opportunities and Challenges” was not limited to a particular definition of what ethical consumerism is or a specific social sciences discipline. Rather, we aimed to encourage submissions tackling various aspects of ethical consumerism, but with a specific focus on the understudied contexts of emerging markets. Emerging markets are countries (a) with accelerated economic growth, (b) open to global markets, and (c) in a transitional (developing to more developed) status (Shankar & Narang, 2020). Hoskisson et al., (2000, p. 249) defined emerging markets as “low-income, rapid-growth countries using liberalization as their primary engine of growth.” The focus on emerging market contexts is relevant for at least four important reasons.

First, emerging markets are powerful drivers of global economic development and represent great business opportunities (Arunachalam et al., 2020; Cuervo-Cazurra & Pananond, 2023; Deloitte, 2020). As established markets are saturated, multinational firms are increasingly turning toward emerging markets, where they expect to enjoy economic growth (London & Hart, 2004). Notably, while the global GDP is foreseen to grow by 1.7% in 2023, the GDP for advanced economies is projected to be 0.5%, while emerging markets excluding China are predicted to grow at 2.7% in the same year (World Bank, 2023). Companies targeting emerging markets have initially focused mostly on the wealthy elites, foremost to market high-priced luxury items, but they are now increasingly considering the bottom of the economic pyramid (BoP)—the world’s largest and fastest-growing consumer segment (Hammond & Prahalad, 2004; London & Hart, 2004; Shankar et al., 2008).

Second, emerging markets are gaining economic power as developed economies are increasingly dependent on emerging ones, given the delocalization of manufacturing in categories such as fashion or electronics (e.g., Gillani et al., 2023), or the supply of raw materials such as rare earth elements or energy (e.g., Schmid, 2019). Two events demonstrating the high interdependency of developed and emerging market economies are the COVID-19 crisis with a dramatic shortage of medical masks in many Western countries because of global supply problems related to masks produced in China, and the 2022 shutting down of Russian gas supply to Europe.

Third, while emerging markets are drivers of global economic development, the benefits of globalization arise frequently at the expense of producers, people, and the environment in emerging countries. Such benefits are contingent upon lower manufacturing costs, minimal wages, or undesirable working conditions in emerging countries, and contribute to furthering marginalization of BoP consumers (cf., Ridley-Duff & Southcombe, 2012; Gillani et al., 2023). Governments, the media, and producers face great ethical responsibility for the economic development of emerging markets with significant implications for the “triple bottom line”—People, Planet, and Profit (cf., Carrington et al., 2021; Narasimhan et al., 2015; Rauch et al., 2016).

Fourth, emerging markets take increasing responsibility for global sustainability (Cheung & To, 2021; Dermody et al., 2018). Moreover, ethical consumption is frequently seen as a means for consumers to address social and ecological problems (Johnston et al., 2011). In key emerging markets such as Brazil, China, India, Mexico, South Africa, and Turkey, socially responsible consumption is gaining traction (Jung et al., 2016; Papaoikonomou & Alarcon, 2017). The rise of the new middle class in emerging markets (Kravets & Sandikci, 2014) is driving increased consumer spending, coupled with a growing awareness of ethical and environmental practices and implications. As consumers are more aware and are increasingly considering ethical aspects in their consumption choices, they also expect greater transparency from firms and demand more frequently an end to exploitative practices, aiming for a fairer society.

Ideas revolving around ethical consumerism draw increasing attention from government bodies, journalists, activist organizations, marketers, as well research interests across disciplines (Carrington et al., 2021). Debates exist, for example, in relation to the fair-trade movement, consumer responses to CSR communication, anti-consumption and boycotting behavior, or social entrepreneurship. Our CFP for this SI was motivated by the fact that most ethical consumerism research, across disciplines, focuses on developed countries' contexts, but surprisingly little is known about ethical consumerism within emerging markets. Hassan et al. (2022) recently found that a significant majority (> 75%) of published studies into consumer ethics were conducted in developed markets contexts. It remains unclear whether important research ideas, devised for developed country contexts, can be generalized to emerging market contexts (e.g., Pels & Sheth, 2017). For example, Li et al. (2024), in this SI, found that most of their study participants in China were even not aware of the term “ethical consumption.” This concurs with the view that terms such as ethical, socially conscious, or green consumers may be viewed as a “cultural phenomenon within affluent consumer cultures” (Newholm & Shaw, 2007, p. 259).

To address these gaps in the ethical consumerism literature, this SI aimed to explore the relatively under-researched context of ethical consumerism in emerging markets. In May 2021, we organized an online paper development workshop which attracted 20 papers from 49 participants and 14 countries. Attending the paper development workshop was not a requirement for the inclusion of a manuscript in the Special Issue. The CFP ultimately resulted in a large number of journal submissions that we handled as guest editors and that underwent the peer-review process. After multiple rounds of reviews, the resulting selected manuscripts along with this introductory essay comprise our SI on ethical consumerism in emerging markets. The SI contains a wide variety of contributions that enhance our understanding of ethical consumerism in emerging markets and offer new perspectives. These include various conceptual and empirical contributions, focusing on diverse emerging country contexts that the authors sometimes contrast with developed market contexts. The authors of the finally accepted papers are affiliated with universities from emerging economies (China, India, Oman, Pakistan, United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia), and from developed economies (Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand, South Korea, Singapore, UK, and the US).

This essay is structured as follows. We first briefly present the articles published in this SI. The next section offers a thematic literature review to structure the existing ethical consumerism research and map the articles from this SI into the wider field. We then present key future research directions and conclude the essay. In doing so, we contribute to the ethical consumerism literature in two main ways. First, through a thematic review of the ethical consumerism literature, we classify three broad categories—contexts of ethical consumerism; forms of ethical consumerism, and understanding ethical consumer behavior, which help us to identify areas of convergence and divergence within the extant research. Further, we position the articles within these themes to highlight how their findings add to the existing ethical consumerism literature. Second, while the papers included in this SI offer many relevant insights and advance our knowledge and understanding of the field, opportunities for further research remain. Our paper provides key future research directions which can serve as a basis for more studies in this field.

The Articles in This Special Issue

Research on ethical consumerism is diverse and varied, and so are the topics that the authors of the articles published in this SI tackle. In this section, we briefly introduce the articles, we then draw upon them further in the thematic review and demonstrate how they add to the extant ethical consumerism literature, particularly in emerging markets. Table 1 summarizes these papers and we map their placement within the extant ethical consumerism research in Fig. 1.

The opening article by Li et al. (2024) focuses on the Chinese practice of Danshari to clarify how differently morality is understood in Chinese and Western contexts, emphasizing that researchers should interpret ethical behaviors against the backdrop of specific country or cultural contexts. Using data from the International Social Survey Program (ISSP), the next article authored by Prikshat et al. (2024) offers new insights into consumers’ socio-cultural capital and country-level affluence as drivers of ethical behaviors in 34 countries. The following article by Osburg et al. (2024) demonstrates significant differences in sustainable luxury consumption in emerging (Brazil, Indonesia, and South Africa) and developed (the United Kingdom) markets. After this is the article by Gupta et al. (2024) who study US and Indian consumers’ expectations about Bottom-of-the-Pyramid (BoP) consumption appropriateness and implications for new product introductions and brand communication. Using consumer data from China, India, the UK, and the US, the next article by Cheng et al. (2024) explores cross-culturally how the COVID-19 pandemic has shaped consumers’ ethical orientations. After this is the article by Besharat et al. (2024), which enhances our understanding of how and why consumers from emerging markets (India, South Africa, and Iran) chose organic food products (tea, coffee). Using field data from Chinese campaigns, the next study by Xing et al. (2024) investigates the success drivers of reward-based crowdfunding for poverty alleviation in China. Following this is the article by Nayak et al. (2024) which explores Indian consumers’ involvement with social networking sites as an antecedent of consumer intentions to purchase ethically. Next, Mehmood et al. (2024) offer new insights into how the publicity of information on plastic recycling affects Chinese consumers’ plastic waste recycling intentions. Lastly, the article by Chan et al. (2024) uses consumer data to explore and empirically test the idea that ethical ideologies (idealism and relativism) indirectly drive ethical behaviors through cultural values, suggesting that ethical ideologies are “culture-free” universals from which cultural values are nurtured.

A Thematic Literature Review

The objective of our thematic literature review is to provide a broader picture of how ethical consumerism research has evolved in terms of recurrent themes and topics, as well as show how the articles in this SI add to various existing debates. We do not intend to provide here a detailed and all-inclusive overview of the literature on ethical consumerism. The sheer volume of published articles in various disciplines and from the most diverse fields (cf., Carrington et al., 2021) prevents an all-encompassing thematic literature review. We signpost below various existing review articles that the readers can consult for further in-depth or specific information on ethical consumerism research (Table 2).

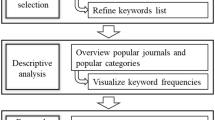

Thematic literature reviews are well suited to identifying overarching themes or categories with common meaning, from various sources. Researchers approach thematic reviews in myriad ways, such as theory-based reviews (e.g., Hassan et al., 2022), meta-analysis (e.g., Dixon-Fowler et al., 2013; Waples et al., 2009), or thematic reviews (e.g., Ford & Richardson, 1994). We aimed to identify suitable structures to represent the diversity of ethical consumerism research in general, into which we embedded the articles in this SI. We drew up initial lists of themes and topics through discussions within the SI editorial team. We identified literature references through keyword searches (e.g., “ethics & consumption”) through pertinent literature sources such as Web of Science (WoS) and the references related to issues on ethical consumerism in the SI. Subsequent discussions within the author team uncovered new themes which led us to restructure our previous ideas. This ongoing process lasted until a suitable structure of themes and topics appeared and no new major themes that were not already specifically or broadly covered emerged.

We, thus, decided to categorize ethical consumerism research broadly in terms of (1) contexts of ethical consumption, (2) forms of ethical consumerism, and (3) approaches to understanding ethical consumer behavior. Through our literature review, we identified various specific topics within these broad categories. We offer short introductions to the selected themes or topics, summarize relevant debates, as well as demonstrate how the articles in this SI enhance our understanding of ethical consumerism in emerging market contexts.

Contexts of Ethical Consumerism

Authors have studied ethical consumerism in numerous different contexts such as ethical investment (e.g., Pilaj, 2017), ethical tourism and hospitality (Fleckenstein & Huebsch, 1999; Ma et al., 2020), fast-fashion (Pedersen et al., 2018; Perry et al., 2015), hybrid vehicles (e.g., Bhutto et al., 2022), biodiversity protection and conversation (Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2017), climate change (e.g., Habib et al., 2021), sharing platforms (Nadeem et al., 2021) as well as institutional contexts of ethical consumerism (e.g., Adeleye et al., 2020; Ariztia et al., 2014). Five contexts relevant to the articles in this SI are globalization, organic food consumption, sustainable luxury, crowdfunding, and online social networking. We briefly summarize the relevance of these contexts and the contributions of this SI.

Globalization

The contributions of this SI to ethical consumerism research are strongly related to globalization and the increasing importance of emerging countries for global sustainable development. Researchers in this vein regularly emphasize the importance of culture (Bartikowski et al., 2018; Belk et al., 2005; Husted & Allen, 2008; Swaidan, 2012) and have reported significant differences in ethical behaviors across countries or cultures (Auger et al., 2010; Bucic et al., 2012; Chu et al., 2020; Davis et al., 1998; Lu et al., 1999; Oreg & Katz-Gerro, 2006; Walsh & Bartikowski, 2013). Cultural values or dimensions account for such differences (e.g., Lu et al., 1999; Vitell et al., 1993). For example, Gregory‐Smith et al. (2017) found heterogeneities in the willingness to pay for environmentally-friendly products across 28 EU countries.

The following articles in this SI are concerned with globalization or conduct cross-cultural comparisons. Prikshat et al. (2024) offer insights into the role of individual socio-cultural capital and country-level affluence as drivers of ethical consumer behavior across 34 countries. The findings indicate that ethical consumerism varies between emerging and developed markets, and cultural capital is a significant predictor of ethical consumerism, even stronger than social capital. Li et al. (2024) emphasize that morality is very differently understood in Chinese and Western contexts, requiring very different interpretations of forms of ethical consumer behaviors. Osburg et al. (2024) compare sustainable luxury consumption in emerging and developed countries. Further, Gupta et al. (2024) study mainstream consumers’ expectations about consumption appropriateness in emerging and developing countries, and Cheng et al. (2024) offer a cross-cultural comparison of how the COVID-19 pandemic shaped people’s ethical orientations.

Organic Food Consumption

Food consumption is one of the mainstream contexts for ethical consumerism research. Eating and drinking are central to human life and have an important impact on our health, which may explain the popularity of research in food contexts, and related aspects such as organic-, vegetarian-, meat-free, or vegan food. For example, Aertens et al. (2011) found that consumers are motivated to buy organic vegetables primarily because they are without pesticides, better for the environment, better for children, and more animal friendly. Studies report that consumers tend to be positively disposed toward organic food, and factors such as greater awareness of and additional knowledge about organic food can reinforce such positive attitudes (Aertsens et al., 2011; Chryssochoidis, 2000; Padel & Foster, 2005). Besharat et al. (2024), in this SI, enhance our understanding of how and why emerging market consumers (India, South Africa, and Iran) chose organic food products (tea, coffee). The authors demonstrate that marketers may trigger mental categorizations within consumers of organic food (e.g., tea, coffee) and how such mental categorizations affect consumers’ brand choices.

Sustainable Luxury

The study of ethical or sustainable luxury emerged only recently (Davies et al., 2012; Kapferer, 2010), and research interest is recently gaining traction (Athwal et al., 2019; Osburg et al., 2021). Sustainable luxury is a broad term that englobes various ideas such as responsible luxury, green luxury, eco-luxury, or organic luxury (Athwal et al., 2019; Janssen et al., 2014). Simplified, sustainable luxury is luxury marketing integrating ideas on ethics and sustainability. The context of emerging countries is particularly relevant to sustainable luxury marketing, given that emerging markets such as China and India are important driving forces behind market growth in various luxury categories such as cars, fashion or cosmetics (Bai et al., 2022; Bartikowski et al., 2019). One relevant discussion revolves around the compatibility of luxury consumption with ethics and sustainability ideas (Achabou & Dekhili, 2013; Kapferer & Michaut-Denizeau, 2014). Work by Janssen et al. (2014) suggests that the “Catch-22 of responsible luxury” relies on two key factors, the scarcity and the ephemerality of luxury products. Other research focused on explaining how luxury brands’ CSR initiates affect consumers' brand perceptions and behavior, such as willingness to pay higher prices for sustainable luxury brands (Amatulli et al., 2018; Diallo et al., 2021).

Adding to this literature, Osburg et al. (2024), in this SI, study how differently a product’s sustainability characteristics shape consumers’ product perceptions and preferences for luxury as compared to mass-market products in developed (UK) versus emerging markets (Brazil, Indonesia and South Africa). Considering watches as a product category, the authors show that sustainability (vs. conventional) product features lead to more positive consumer reactions (value perceptions and behavioral intentions). The effects tend to be stronger for luxury products in developed country contexts, and stronger for mass-market than luxury products.

Social Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding has emerged as a new marketing channel (Calic & Mosakowski, 2016; Fassin & Drover, 2017). Entrepreneurs can sell products to businesses- or end-consumers through campaigns that they establish on specific crowdfunding platforms through which they can reach backers worldwide. Crowdfunding is particularly promising to social entrepreneurs and poverty alleviation, given that pro-social crowdfunding campaigns, as compared to ordinary ones, tend to be more successful (reach funding goals faster, create more demand) (Calic & Mosakowski, 2016; Dai & Zhang, 2019; Simpson et al., 2021). However, such results are not conclusive, and social crowdfunding campaign success may also be contingent on factors such as the type of crowdfunding (e.g., donation-, lending- or reward-based crowdfunding), or the crowdedness of the platform (Defazio et al., 2021; Figueroa-Armijos & Berns, 2021).

Adding to this literature, Xing et al. (2024), in this SI, explore success drivers of reward-based crowdfunding for poverty alleviation. Data from 4375 reward-based crowdfunding campaigns (2014–2020) in China shows that campaigns tagged as poverty alleviation, compared to ordinary ones, tend to be more successful, particularly for products that originate from poorer regions and when prices are lower. The authors corroborate findings from their field study with an experimental study, additionally demonstrating that engaging in poverty alleviation crowdfunding raises Chinese consumers’ feelings of warm glow which, in turn, enhances the purchasing amount. Activation of a warm glow is a psychological process that accounts for the success of reward-based crowdfunding for poverty alleviation in China. Given that China has long faced significant problems of wealth inequality, the results from this study may serve China’s government in furthering crowdfunding and targeted poverty alleviation policies to improve income for the poor.

Social Networking Sites

Social networking sites (SNS) such as Facebook, Instagram, or Qzone provide consumers with a large amount of information about others (friends, family), as well as about products and services. Researchers have studied ethical consumer behavior on SNS for example about harmful misbehaviors such as identity theft, cyberstalking, or cyberbullying (e.g., Freestone & Mitchell, 2004; Rauf, 2021), or focused on ethical issues such as greenwashing or employee surveillance through SNS (Clark & Roberts, 2010; Lyon & Montgomery, 2013). SNS are also the home for ethical social media communities (e.g., green communities or responsible consumption communities), which are groups of interconnected people that attempt to encourage some form of ethical behavior, such as ecological behavior (Steg et al., 2014) or ethical consumption (Gummerus et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021). For example, Shen et al. (2023) found that informational benefits that arise from community participation reinforce consumers’ ethical consumption behavior, whereas social and entertainment benefits affect loyalty to the community.

Adding to this literature, in this SI, Nayak et al. (2024) study consumer involvement with SNS as an antecedent of consumer intentions to purchase ethically. Based on a series of qualitative studies (observations, interviews, and focus group discussions) with consumers from India, the authors identify seven dimensions or aspects of SNSs that account for consumer attitudes, norms, and behavioral control about purchasing ethically. The seven dimensions include SNS efficacy (convenience, information abundance, availability, and immediateness), online communities (common shared interests), online word of mouth (timeliness, relevance, and comprehensiveness), consumer knowledge (objective information and subjective knowledge), social support (relational and informational), SNS communication (content and positive or negative valence) and price sensitivity (informational cue and assessment of sacrifice).

Forms of Ethical Consumerism

Ethical consumerism manifests in various types of ethical consumption behaviors such as the buying of ethical product options (Xing et al., 2024), consumer preferences for more ethical brands (Gupta et al., 2024; Osburg et al., 2024), or types of ethically questionable consumption practices (Chan et al., 2024). Ethical consumerism may also manifest in anti-consumption- or boycotting behaviors (e.g., García-de-Frutos et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2009), or in charitable giving (e.g., Bock et al., 2018; Jamal et al., 2019; Simpson et al., 2018).

Moreover, new forms of economic models are increasingly popular, with firms putting people and the planet first, in contrast to interpreting their mission in terms of profit-primacy and -maximization. These models englobe, for example, ideas on economic democracy or democratic economies—the idea of a shift of power and benefits from corporate shareholders and managers to larger groups of stakeholders and the broader public, leading to new forms of ethical consumer behavior. Related ideas appear in research into the fair-trade movement (e.g., Andorfer & Liebe, 2012; Gillani et al., 2021), the circular economy (Kutaula et al., 2022) or the sharing economy (Chi et al., 2020). Various authors have studied ethical consumerism from the perspective of ethical corporate behaviors. Related work revolves around moral values and organizational ethical culture (e.g., Barnett et al., 1994; Chun, 2019; Forsyth, 1992; York, 2009). For example, Drumwright and Murphy (2004) studied advertiser’s view of ethics or Al‐Khatib et al. (2016) differentiated global marketing negotiators based on their ethical profiles.

Resource-Efficient Ethical Behaviors

One prominent form of ethical consumerism is behaviors that consumers engage in for reasons such as utilizing given resources more ethically or more sustainably. Resource-efficient behaviors include energy-saving, waste, and recycling behaviors. Energy saving is the set of practices that reduce energy consumption, for example as a socially responsible response to climate change. For example, Gadenne et al. (2011) and Yue et al. (2013) offer insights into factors influencing consumers' energy-saving behaviors. Focusing on waste behavior, Roe et al. (2020) emphasize that nearly one-third of food produced on the planet never meets its intended purpose of human nourishment. The authors discuss the ethics of food waste in relation to food donation behavior or buying food with cosmetic imperfections (i.e., “ugly food”). Aschemann-Witzel et al. (2018) studied consumer characteristics influencing food waste behavior (choice of price-reduced suboptimal food) among consumers in Uruguay. Focusing on recycling, Hornik et al. (1995) offer a synthesis of research results from 67 studies on the determinants of recycling behavior, finding that “internal facilitators” (consumer knowledge and commitment to recycling) count among the strongest predictors of consumers’ propensity to recycle. Other studies predicted recycling behavior based on consumers’ environmental attitudes (Vining & Ebreo, 1992), moral orientations (Culiberg, 2014; Culiberg & Bajde, 2013), or recycling habits (learned automatic behaviors) (Aboelmaged, 2021). One sub-stream of the recycling literature is concerned with “bringing your own shopping bag” BYOB behavior (Chan et al., 2008; Karmarkar & Bollinger, 2015).

Adding to this literature, as part of this SI, Mehmood et al. (2024) offer new insights into how the publicity of information on plastic recycling affects Chinese consumers’ plastic waste recycling intentions. China is among the world’s largest plastic-producing countries, and the Chinese government regularly launches initiatives that disseminate information to encourage plastic recycling. Their findings suggest that the publicity of information about plastic recycling affects consumers’ perceived social pressure and recycling intentions positively, although the effects depend on media richness and the trustworthiness of the message content. Chinese officials may benefit from these ideas as they offer new insights into the effectiveness of information that encourages plastic recycling.

Another article in this SI contributing to the literature on resource-efficient behaviors is authored by Li et al. (2024). The authors suggest that seemingly ethical behaviors among Chinese may be motivated by factors other than morality, noting that morality is conceptualized differently in Asian (Chinese) than in Western cultures. Their study findings suggest very little awareness of ethical consumption ideas among Chinese participants. Instead, the concept of Danshari (separating, detaching, and departing from possessions) can efficiently explain seemingly ethical behaviors such as reuse or recycling behaviors.

BoP Marketing

The idea that multinational firms could grow profits and help relieve poverty by doing business with the poor has gained significant attention in the management literature since the work of Prahalad and colleagues (Prahalad & Hart, 1999; Prahalad & Lieberthal, 1998) (cf., Kolk et al., 2014). “Bottom of the Pyramid” (BoP) consumers from developing and emerging markets are among the world’s largest and fastest-growing consumer segments (Hammond & Prahalad, 2004; London & Hart, 2004; Shankar et al., 2008). Kolk et al. (2014) offer a systematic review of 104 BoP articles published over 10 years (2000–2009). According to the authors, BoP research has evolved dramatically since Prahalad et al.’s initial work, deemphasizing the role of multinational firms over time and portraying wide variations in terms of BoP contexts, BoP initiatives, and the impacts of the BoP approach. Among others, authors have tackled topics such as BoP business models (e.g., Pels & Sheth, 2017) or the role of CSR as a success driver of BoP marketing (Davidson, 2009).

One stream of BoP research discusses issues on adequate or permissible consumption concerning BoP consumers (e.g., Hagerty et al., 2022; Hill, 2005; Martin & Paul Hill, 2012). Adding to this literature, Gupta et al. (2024), in this SI, suggest that the proliferation of global media may make mainstream consumers more aware of multinational’s BoP marketing, and make them judge the firm for its BoP efforts. Mainstream consumers may have ideas about what BoP consumers should or should not consume and judge firms negatively for BoP marketing that deviates from these expectations. The findings from two experimental studies show that mainstream consumers in developed markets (i.e., the US) respond less favorably to companies launching hedonic (as compared to utilitarian) products in BoP markets, but no such differences exist for mainstream consumers in emerging (i.e., India) markets. For mainstream consumers in emerging markets, these effects are contingent on the brand’s country of origin (developed vs. emerging market) and the company's profit orientation (for- vs. non-profit).

Approaches to Explaining Ethical Consumer Behavior

The study of consumer behavior is concerned with individual or collective behaviors in purchasing contexts (e.g., why people buy or don’t buy ethical products) and is essential for a deeper understanding of ethical consumerism (e.g., Vitell, 2015). There are various review articles or meta-analyses on ethical consumer behavior, such as Bamberg and Möser’s (2007) meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behavior, Klöckner’s (2013) meta-analysis about the psychology of environmental behavior or White et al.’s (2020) review and framework about the drivers of pro-social consumer behavior. Hassan et al.’s (2022) review of 106 articles on consumer ethics finds that personal factors, social and interpersonal factors, and consumer emotions are the most frequently studied variables in explaining ethical consumer behaviors. We review key approaches to understanding ethical consumer behavior and summarize how the articles of this SI contribute to the respective fields (see Fig. 1).

Consumer Segmentation

Consumer segmentation is a central concept in marketing that numerous authors have applied to achieve a better understanding of ethical consumer behavior, including demographic segmentations of ethical consumers (e.g., Belbağ et al., 2019; Perera et al., 2018) or psychographic segmentations (e.g., Burke et al., 2014; Walsh et al., 2010). Such approaches to segmentation can also be noted in practitioner reports based on extensive market research. For example, Crowe and Williams (2000) identified five clusters of consumers based on individuals’ attitudes to, and actions on, ethical issues. Moreover, Shaw and Newholm (2002) proposed that contemporary consumers should be divided into two categories according to their level of consumption: consumers who maintain a certain level of consumption; and consumers who reduce the level of their consumption. Others have argued that consumers can be located on a continuum of ethics while moving between three main categories i.e., non-voluntary simplifiers, beginner voluntary simplifiers, and voluntary simplifiers (McDonald et al., 2006) that can be used as main segmentation groups.

Consumer Motivation and Personality

Motivation is an internal psychological force that drives people to act to fulfill some goals or satisfy needs. Besides physiological needs, researchers consider various psychological or psychogenic needs for a better understanding of ethical consumer behavior. Psychological needs may derive from consumers' individual traits and identity and include goals such as creating a positive self-perception or social recognition, both of which may be satisfied through ethical consumption (e.g., Cherrier, 2007; Dermody et al., 2018). Authors have considered various individual characteristics such as personality traits (Lu et al., 2015) or materialism (Kilbourne & Pickett, 2008) to explain some type of ethical consumer behavior. For example, Song and Kim (2018) found that virtuous traits of self-efficacy, courage, and self-control, as well as the personality traits of openness and conscientiousness, predict socially responsible purchase and disposal behavior.

Significant research considers that consumers’ moral principles and ethical values guide the adoption of pro-social or ethical behaviors (e.g., Chen & Moosmayer, 2020; Hassan et al., 2022). For example, Brinkmann (2004) suggested that ethical marketing initiatives invite consumers to take moral responsibility for the consequences of their buying behavior (i.e., how other people, animals, or the natural environments are affected). Morality is broadly about the internal norms, values, and beliefs that define to an individual what is right and wrong (cf., Crane & Desmond, 2002). Moral principles or motivations that support pro-social consumer behaviors may not be the same moral motivations for condemning unethical actions (Chowdhury, 2019). Researchers consider that individuals differ in terms of their moral maturity, with a significant impact on the adoption of ethical behaviors (e.g., Bray et al., 2011).

Adding to our understanding of how moral principles affect ethical consumer behavior, Chan et al. (2024), in this SI, developed a new conceptual model suggesting that ethical ideologies (idealism and relativism) indirectly affect Chinese consumers’ ethical behavior through cultural values. Although numerous authors acknowledge the important role of ethical ideologies and cultural values in explaining ethical consumer behavior, only a few studies have integrated the two as determinants of ethical consumer behavior (e.g., Culiberg, 2015) and it is conceptually unclear how they are interrelated. Considering ideologies as an individual’s unconscious motivational processes, they assert that idealism and relativism are “culture-free” or universal and form the soil from which cultural values are nurtured. Results from a large-scale online consumer survey in China are consistent with the postulated impact of ethical ideology on forming an individual’s beliefs and cultural values, as well as highlight the importance of a thorough understanding of ethical ideologies for an enhanced understanding of ethical consumer behavior.

Moral principles and ethical values provide a conceptual background to studies considering consumers’ religiosity and spirituality as drivers of ethical consumer behavior. The link between morality and religiosity can be traced back to the theoretically unresolved discussion of whether morality can exist without belief in God or not (cf., Arli & Pekerti, 2017). Indeed, most religions largely agree on moral norms for good doing such as charity, honesty, or justice. More religious consumers may, therefore, be thought to be more ethical than less religious ones, but past research has suggested mixed results (Arli & Pekerti, 2017; Arli et al., 2021; Ramasamy et al., 2010; Vitell et al., 2016).

Consumer Attitude Formation and Change

Attitudes are learned predispositions about objects, ideas, or people and are central to understanding consumer behavior. Attempting to explain ethical consumer behavior, some authors have studied the antecedents of consumer attitudes toward CSR. For example, in the context of business students, Kolodinsky et al. (2010) found that CSR attitudes were positively related to ethical idealism, and negatively to ethical relativism and materialism, but there was no relationship with spirituality. Others have focused on the attitudinal consequences of consumers’ CSR perceptions in terms of attitudes toward the brand or other behavioral dispositions (e.g., word-of-mouth behavior, or purchasing intentions) (e.g., Ferrell et al., 2019).

One specific topic that has received significant research attention in ethical consumerism research is the “attitude–behavior gap”—the phenomenon that consumers may hold positive attitudes toward some type of ethical behavior, but frequently fail to execute them through attitude-consistent behaviors (e.g., Auger & Devinney, 2007; Carrington et al., 2010; Hassan et al., 2016). The phenomenon has led to significant theorizing about its socio-psychological origins (e.g., Carrington et al., 2010, 2014), ethical decision processes (e.g., Hunt & Vitell, 1986, 1993), or the processing of ethical information and believe formation (Shaw & Clarke, 1999). Researchers have studied the attitude–behavior gap in various contexts, including organic food consumption (Padel & Foster, 2005) and fair-trade consumption (Chatzidakis et al., 2007; De Pelsmacker et al., 2005).

Closely related to the study of attitudes is the role of emotions as drivers of ethical behavior (Aertsens et al., 2011; Camerer & Fehr, 2006). Authors have considered various types of emotions such as guilt and pride (Antonetti & Maklan, 2014; Chen & Moosmayer, 2020; Gregory-Smith et al., 2013), anticipated emotions (Escadas et al., 2019) or feelings of warm glow (Bhattacharya et al., 2021) to explain ethical consumer behaviors. Adding to our understanding of how emotions affect ethical consumer behavior, Cheng et al. (2024), in this SI, explore how global crises affect people’s ethical orientations. According to the authors, the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered terror (emotions of fear, death-related anxiety) within consumers, and ethical consumption may serve as a form of psychological defense mechanism against such terror. Moreover, ethical consumer responses may be affected by consumers’ belief in a negotiable fate, a characteristic that is particularly prevalent in Asian countries. The results from two studies with data collected from consumers in China, India, the UK, and the US show that perceived pandemic severity increased consumers’ intention to consume ethically. Ethical consumption can mitigate consumers’ mortality anxieties during crises, but this effect is reduced in tight (China, India) as compared to loose (UK, US), cultures. Consumers’ belief in negotiable fate is found to enhance ethical consumption but alleviates the effect of pandemic severity on ethical consumption in tight cultures.

Communication and Persuasion

Numerous researchers have explored consumers’ CSR perceptions (e.g., perceptions of firms’ CSR initiatives or CSR communication) as drivers of consumer behavior, broadly finding that positive CSR tends to positively impact relationships between firms and stakeholders (e.g., Bhattacharya et al., 2009; Osburg et al., 2020). This relationship is moderated by various company-specific or individual-specific factors (Cheung & To, 2021; Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001). For example, Ramasamy and Yeung (2009) studied the importance placed on Chinese consumers’ perceptions of firms’ economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities, finding that economic responsibilities are most important while philanthropic responsibilities are of least importance.

Most companies today recognize the important role of brands for business success and strive to enhance brand awareness as well as cultivate a positive brand image and reputation in the minds of consumers. Not surprisingly, numerous studies have focused on the role of signaling CSR or ethical corporate behaviors to enhance brand image and positioning both in business-to-consumer (e.g., Balmer et al., 2011; Bartikowski et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2012) and business-to-business settings (Su et al., 2016). For example, Brunk (2012) conceptualized the construct of consumer perceived ethicality (CPE) of a company or brand and developed scales to measure CPE empirically. Alwi et al. (2017) found for industrial buyers from Malaysia that perceived price and service quality affect brand reputation through ethical branding (i.e., the positioning of the brand with and “ethical identity”).

Consumers’ CSR perceptions result from information that they learn from sources such as the press, social media, or advertising. Numerous studies have focused on message effects (message appeals and framing) for an enhanced understanding of ethical consumerism. For example, White and Simpson (2013) studied how and why various types of normative message appeals (i.e., what others think one should do vs. what others are doing vs. benefits of the action) encourage consumers to engage in sustainable behaviors, finding that appeal effects depend on whether the individual or collective level of the self is activated. Message framing broadly refers to communication techniques that stimulate a certain interpretation of a given piece of information. Studies concerned with message framing in CSR communication tend to conclude that positively framed CSR messages (i.e., highlighting the positive) lead to more positive consumer reactions, although factors such as the product category (high vs. low risk) or the message specificity (concrete vs. vague) can moderate such message effects (Bartikowski & Berens, 2021; Olsen et al., 2014).

Consumer researchers frequently think of belief formation and persuasion in terms of a learning process and consider categorical learning (or categorization) to explain consumer behavior. Categorization means that people learn, remember, and integrate new information as they assign new incoming information in terms of how well it fits with existing knowledge categories (e.g., Bartikowski et al., 2022; Rosch & Lloyd, 1978). Drawing upon categorization ideas, the article by Besharat et al. (2024), in this SI, enhances our understanding of how and why emerging market consumers choose ethical products, focusing on the context or organic products (tea, coffee), and considering consumer data from three emerging markets (India, South Africa, and Iran). According to the authors, marketers may present products in terms of broader or narrower categories. For example, coffee may be presented to consumers either broadly by roast only (e.g., light, medium, dark) or narrowly by roast and origin (e.g., light roast, Argentina; light roast, Colombia). Such categories that marketers can easily create may lead to different product categorizations in the minds of consumers and inform their information processing and persuasion. In particular, they expect that consumers will notice more details when presented with narrow (as compared to broad) product options. A series of four experimental studies show that when consumers see narrow (vs. broad) product categories, they are more likely to engage in deeper processing and incorporate both salient (self-focused) and non-salient (other-focused) attributes into their choice decision. The findings are relevant to marketers of consumer-packaged goods aiming to overcome resistance against ethical consumption in emerging market contexts. Narrowly presented products encourage consumers to consider ethical attributes to a greater extent than they normally would and can encourage ethical consumption in emerging markets.

Future Research Areas

While the articles in this special issue have made significant headway into advancing new perspectives within the area of ethical consumerism in emerging markets, there remains scope for further research. In this section, we proffer some avenues for future research, drawing on insights from the submissions for this SI (outlined in Table 1) and our reflections. First, conceptually, while this SI explicates what constitutes ethical consumerism, it is also important to examine related constructs such as consumer social responsibility (Vitell, 2015), political consumption (Gohary et al., 2023), or green consumerism (Akhtar et al., 2021) to explore how these concepts intersect, which can often generate innovative insights. Further, the research could investigate the potential interactions between some of the themes we have identified in this essay—for instance, globalization and ethical consumerism, and how reshoring impacts ethical consumption in emerging markets as opposed to developed countries (Gillani et al., 2023).

Second, theoretically, going forward, studies could review more novel antecedents, mediators/moderators, and outcomes, which can drive more context-dependent theorizing. In this SI, Chan et al. (2024) advocate studies to use all four Chinese cultural value (CVS) dimensions, namely integration, moral discipline, human-heartedness, and Confucian work dynamism, and examine their effects on ethical consumption. Similarly, Prikshat et al. (2024) in this SI propose that researchers can consider using different indicators of ethical consumerism and trust and examine various individual-level values, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors.

Third, contextually, future research could focus on comparative studies with other emerging markets and developed countries to identify commonalities and differences and offer a wider context for the findings from these articles in the SI (e.g., Besharat et al., 2024; Chan et al., 2024; Mehmood et al., 2024). This can be done by studying the role of other relevant cultural factors that the studies in this SI do not consider, such as—autonomy, egalitarianism, and interdependent self-construal in shaping ethical consumption (Cheng et al., 2024) or assessing variables such as collectivism at a cultural level (Mehmood et al., 2024). We also urge researchers to integrate, replicate, and build upon work from this SI. An example is Nayak et al. (2024), who present a comprehensive model through their in-depth qualitative study, which can be tested on different types of consumers or in varied research settings.

Finally, methodologically, studies could be designed longitudinally to consider changes over time. For instance, Li et al. (2024) in this SI suggest examining Danshari among consumers over a period of time to provide insights into such culturally nuanced phenomena. We also recommend researchers expand causal associations, e.g., undertake field experiments, longitudinal surveys, and case studies (Chan et al., 2024; Gupta et al., 2024; Prikshat et al., 2024). Further, Cheng et al. (2024) in this SI encourage researchers to examine other constructs such as pandemic-related death thoughts, self-esteem, and symbolic immortality, and identify their temporal impact on ethical consumption.

Conclusions

Research on ethical consumerism is diverse and varied. Our thematic literature analysis has provided readers with a broad overview of existing research on ethical consumerism, as well as contextualizing the findings and contributions that the articles published in this SI are offering. Given the increasing economic importance of emerging markets and their impact on sustainable development, it is important that studies continue to explore and test the validity of concepts, models, or phenomena of ethical consumerism considering the specificities of emerging market contexts. The articles in this SI expand on important future research directions.

References

Aboelmaged, M. (2021). E-waste recycling behaviour: An integration of recycling habits into the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Cleaner Production, 278, 124182.

Achabou, M. A., & Dekhili, S. (2013). Luxury and sustainable development: Is there a match? Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1896–1903.

Adeleye, I., Luiz, J., Muthuri, J., & Amaeshi, K. (2020). Business ethics in Africa: The role of institutional context, social relevance, and development challenges. Journal of Business Ethics, 161, 717–729.

Aertsens, J., Mondelaers, K., Verbeke, W., Buysse, J., & Van Huylenbroeck, G. (2011). The influence of subjective and objective knowledge on attitude, motivations, and consumption of organic food. British Food Journal, 113(11), 1353–1378.

Akhtar, R., Sultana, S., Masud, M. M., Jafrin, N., & Al-Mamun, A. (2021). Consumers’ environmental ethics, willingness, and green consumerism between lower and higher income groups. Resources, Conservation and Recycling,. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105274

Al-Khatib, J. A., Al-Habib, M. I., Bogari, N., & Salamah, N. (2016). The ethical profile of global marketing negotiators. Business Ethics: A European Review, 25(2), 172–186.

Alwi, S. F. S., Ali, S. M., & Nguyen, B. (2017). The importance of ethics in branding: Mediating effects of ethical branding on company reputation and brand loyalty. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(3), 393–422.

Amatulli, C., De Angelis, M., Korschun, D., & Romani, S. (2018). Consumers’ perceptions of luxury brands’ CSR initiatives: An investigation of the role of status and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Cleaner Production, 194, 277–287.

Andorfer, V. A., & Liebe, U. (2012). Research on fair trade consumption—A review. Journal of Business Ethics, 106, 415–435.

Antonetti, P., & Maklan, S. (2014). Feelings that make a difference: How guilt and pride convince consumers of the effectiveness of sustainable consumption choices. Journal of Business Ethics, 124, 117–134.

Ariztia, T., Kleine, D., Maria das Graças, S., Agloni, N., Afonso, R., & Bartholo, R. (2014). Ethical consumption in Brazil and Chile: Institutional contexts and development trajectories. Journal of Cleaner Production, 63, 84–92.

Arli, D., & Pekerti, A. (2017). Who is more ethical? Cross-cultural comparison of consumer ethics between religious and non-religious consumers. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 16(1), 82–98.

Arli, D., Septianto, F., & Chowdhury, R. M. (2021). Religious but not ethical: The effects of extrinsic religiosity, ethnocentrism, and self-righteousness on consumers’ ethical judgments. Journal of Business Ethics, 171, 295–316.

Arunachalam, S., Bahadir, S. C., Bharadwaj, S. G., & Guesalaga, R. (2020). New product introductions for low-income consumers in emerging markets. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48, 914–940.

Aschemann-Witzel, J., Giménez, A., & Ares, G. (2018). Convenience or price orientation? Consumer characteristics influencing food waste behaviour in the context of an emerging country and the impact on the future sustainability of the global food sector. Global Environmental Change, 49, 85–94.

Athwal, N., Wells, V. K., Carrigan, M., & Henninger, C. E. (2019). Sustainable luxury marketing: A synthesis and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 21(4), 405–426.

Auger, P., & Devinney, M. (2007). Do what consumers say matter? The misalignment of preferences with unconstrained ethical intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 76, 361–383.

Auger, P., Devinney, T. M., Louviere, J. J., & Burke, P. F. (2010). The importance of social product attributes in consumer purchasing decisions: A multi-country comparative study. International Business Review, 19(2), 140–159.

Bai, H., McColl, J., & Moore, C. (2022). Luxury fashion retailers’ localised marketing strategies in practice—Evidence from China. International Marketing Review, 39(2), 352–370.

Balmer, J. M., Powell, S. M., & Greyser, S. A. (2011). Explicating ethical corporate marketing. Insights from the BP deepwater horizon catastrophe: The ethical brand that exploded and then imploded. Journal of Business Ethics, 102, 1–14.

Bamberg, S., & Möser, G. (2007). Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(1), 14–25.

Barnett, T., Bass, K., & Brown, G. (1994). Ethical ideology and ethical judgment regarding ethical issues in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 13, 469–480.

Bartikowski, B., & Berens, G. (2021). Attribute framing in CSR communication: Doing good and spreading the word—But how? Journal of Business Research, 131, 700–708.

Bartikowski, B., Fastoso, F., & Gierl, H. (2019). Luxury cars made-in-China: Consequences for brand positioning. Journal of Business Research, 102, 288–297.

Bartikowski, B., Fastoso, F., & Gierl, H. (2021). How nationalistic appeals affect foreign luxury brand reputation: A study of ambivalent effects. Journal of Business Ethics, 169, 261–277.

Bartikowski, B., Gierl, H., Richard, M.-O., & Fastoso, F. (2022). Multiple mental categorizations of culture-laden website design. Journal of Business Research, 141, 40–49.

Bartikowski, B., Laroche, M., Jamal, A., & Yang, Z. (2018). The type-of-internet-access digital divide and the well-being of ethnic minority and majority consumers: A multi-country investigation. Journal of Business Research, 82, 373–380.

Belbağ, A. G., Üner, M. M., Cavusgil, E., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2019). The new middle class in emerging markets: How values and demographics influence discretionary consumption. Thunderbird International Business Review, 61(2), 325–337.

Belk, R., Devinney, T., & Eckhardt, G. (2005). Consumer ethics across cultures. Consumption Markets and Culture, 8(3), 275–289.

Besharat, A., Nardini, G., & Mesler, R. M. (2024). Bringing ethical consumption to the forefront in emerging markets: The role of product categorization. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05667-2

Bhattacharya, A., Good, V., Sardashti, H., & Peloza, J. (2021). Beyond warm glow: The risk-mitigating effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Journal of Business Ethics, 171, 317–336.

Bhattacharya, C. B., Korschun, D., & Sen, S. (2009). Strengthening stakeholder–company relationships through mutually beneficial corporate social responsibility initiatives. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 257–272.

Bhutto, M. H., Tariq, B., Azhar, S., Ahmed, K., Khuwaja, F. M., & Han, H. (2022). Predicting consumer purchase intention toward hybrid vehicles: Testing the moderating role of price sensitivity. European Business Review, 34(1), 62–84.

Bock, D. E., Eastman, J. K., & Eastman, K. L. (2018). Encouraging consumer charitable behavior: The impact of charitable motivations, gratitude, and materialism. Journal of Business Ethics, 150, 1213–1228.

Boiral, O., & Heras-Saizarbitoria, I. (2017). Managing biodiversity through stakeholder involvement: Why, and for what initiatives? Journal of Business Ethics, 140(3), 403–421.

Bray, J., Johns, N., & Kilburn, D. (2011). An exploratory study into the factors impeding ethical consumption. Journal of Business Ethics, 98, 597–608.

Brinkmann, J. (2004). Looking at consumer behavior in a moral perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 51, 129–141.

Brunk, K. H. (2012). Un/ethical company and brand perceptions: Conceptualising and operationalising consumer meanings. Journal of Business Ethics, 111, 551–565.

Bucic, T., Harris, J., & Arli, D. (2012). Ethical consumers among the millennials: A cross-national study. Journal of Business Ethics, 110(1), 113–131.

Burke, P. F., Eckert, C., & Davis, S. (2014). Segmenting consumers’ reasons for and against ethical consumption. European Journal of Marketing., 48(11/12), 2237–2261.

Calic, G., & Mosakowski, E. (2016). Kicking off social entrepreneurship: How a sustainability orientation influences crowdfunding success. Journal of Management Studies, 53(5), 738–767.

Camerer, C. F., & Fehr, E. (2006). When does “economic man” dominate social behavior? Science, 311(5757), 47–52.

Carrington, M., Chatzidakis, A., Goworek, H., & Shaw, D. (2021). Consumption ethics: A review and analysis of future directions for interdisciplinary research. Journal of Business Ethics, 168, 215–238.

Carrington, M. J., Neville, B. A., & Whitwell, G. J. (2010). Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 97, 139–158.

Carrington, M. J., Neville, B. A., & Whitwell, G. J. (2014). Lost in translation: Exploring the ethical consumer intention–behavior gap. Journal of Business Research, 67(1), 2759–2767.

Chan, R. Y., Wong, Y., & Leung, T. K. (2008). Applying ethical concepts to the study of “green” consumer behavior: An analysis of Chinese consumers’ intentions to bring their own shopping bags. Journal of Business Ethics, 79, 469–481.

Chan, R. Y. K., Sharma, P., Alqahtani, A., Leung, T. Y., & Malik, A. (2024). Mediating role of cultural values in the impact of ethical ideologies on Chinese consumers’ ethical judgments. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05669-0

Chatzidakis, A., Hibbert, S., & Smith, A. P. (2007). Why people don’t take their concerns about fair trade to the supermarket: The role of neutralisation. Journal of Business Ethics, 74, 89–100.

Chen, Y., & Moosmayer, D. C. (2020). When guilt is not enough: Interdependent self-construal as moderator of the relationship between guilt and ethical consumption in a Confucian context. Journal of Business Ethics, 161, 551–572.

Cheng, J., Huang, Y., & Chen, B. (2024). Are we becoming more ethical consumers during the global pandemic? The moderating role of negotiable fate across cultures. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05660-9

Cherrier, H. (2007). Ethical consumption practices: Co-production of self-expression and social recognition. Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review, 6(5), 321–335.

Cheung, M. F., & To, W. M. (2021). The effect of consumer perceptions of the ethics of retailers on purchase behavior and word-of-mouth: The moderating role of ethical beliefs. Journal of Business Ethics, 171(4), 771–788.

Chi, M., George, J. F., Huang, R., & Wang, P. (2020). Unraveling sustainable behaviors in the sharing economy: An empirical study of bicycle-sharing in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 260, 120962.

Chowdhury, R. M. (2019). The moral foundations of consumer ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 158, 585–601.

Chryssochoidis, G. (2000). Repercussions of consumer confusion for late introduced differentiated products. European Journal of Marketing, 34, 705–722.

Chu, S.-C., Chen, H.-T., & Gan, C. (2020). Consumers’ engagement with corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication in social media: Evidence from China and the United States. Journal of Business Research, 110, 260–271.

Chun, R. (2019). How virtuous global firms say they are: A content analysis of ethical values. Journal of Business Ethics, 155, 57–73.

Clark, L. A., & Roberts, S. J. (2010). Employer’s use of social networking sites: A socially irresponsible practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 507–525.

Cooper-Martin, E., & Holbrook, M. E. (1993). Ethical consumption experiences and ethical space. Advances in Consumer Research, 20(1), 113–118.

Crane, A., & Desmond, J. (2002). Societal marketing and morality. European Journal of Marketing, 36(5/6), 548–569.

Crowe, R., & Williams, S. (2000). Who are the ethical consumers? Ethical Consumerism Report. Co-operative Bank.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Pananond, P. (2023). The rise of emerging market lead firms in global value chains. Journal of Business Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113327

Culiberg, B. (2014). Towards an understanding of consumer recycling from an ethical perspective. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(1), 90–97.

Culiberg, B. (2015). The role of moral philosophies and value orientations in consumer ethics: A post-transitional European country perspective. Journal of Consumer Policy, 38, 211–228.

Culiberg, B., & Bajde, D. (2013). Consumer recycling: An ethical decision-making process. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 12(6), 449–459.

Dai, H., & Zhang, D. J. (2019). Prosocial goal pursuit in crowdfunding: Evidence from Kickstarter. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(3), 498–517.

Davidson, K. (2009). Ethical concerns at the bottom of the pyramid: Where CSR meets BoP. Journal of International Business Ethics, 2(1), 22–32.

Davies, I. A., Lee, Z., & Ahonkhai, I. (2012). Do consumers care about ethical-luxury? Journal of Business Ethics, 106, 37–51.

Davis, M. A., Johnson, N. B., & Ohmer, D. G. (1998). Issue-contingent effects on ethical decision making: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(4), 373–389.

De Pelsmacker, P., Driesen, L., & Rayp, G. (2005). Do consumers care about ethics? Willingness to pay for fair-trade coffee. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 39(2), 363–385.

Defazio, D., Franzoni, C., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2021). How pro-social framing affects the success of crowdfunding projects: The role of emphasis and information crowdedness. Journal of Business Ethics, 171, 357–378.

Deloitte. (2020). Consumer 2020: Reading the consumer signs. Deloitte. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/ru/Documents/consumer-business/consumer_2020.pdf.

Dermody, J., Koenig-Lewis, N., Zhao, A. L., & Hanmer-Lloyd, S. (2018). Appraising the influence of pro-environmental self-identity on sustainable consumption buying and curtailment in emerging markets: Evidence from China and Poland. Journal of Business Research, 86, 333–343.

Diallo, M. F., Ben Dahmane Mouelhi, N., Gadekar, M., & Schill, M. (2021). CSR actions, brand value, and willingness to pay a premium price for luxury brands: Does long-term orientation matter? Journal of Business Ethics, 169, 241–260.

Dixon-Fowler, H. R., Slater, D. J., Johnson, J. L., Ellstrand, A. E., & Romi, A. M. (2013). Beyond “does it pay to be green?” a meta-analysis of moderators of the CEP–CFP relationship. Journal of Business Ethics, 112, 353–366.

Drumwright, M. E., & Murphy, P. E. (2004). How advertising practitioners view ethics: Moral muteness, moral myopia, and moral imagination. Journal of Advertising, 33(2), 7–24.

Escadas, M., Jalali, M. S., & Farhangmehr, M. (2019). Why bad feelings predict good behaviours: The role of positive and negative anticipated emotions on consumer ethical decision making. Business Ethics: A European Review, 28(4), 529–545.

Fassin, Y., & Drover, W. (2017). Ethics in entrepreneurial finance: Exploring problems in venture partner entry and exit. Journal of Business Ethics, 140, 649–672.

Ferrell, O., Harrison, D. E., Ferrell, L., & Hair, J. F. (2019). Business ethics, corporate social responsibility, and brand attitudes: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Research, 95, 491–501.

Figueroa-Armijos, M., & Berns, J. P. (2021). Vulnerable populations and individual social responsibility in prosocial crowdfunding: Does the framing matter for female and rural entrepreneurs? Journal of Business Ethics, 177, 1–18.

Fleckenstein, M. P., & Huebsch, P. (1999). Ethics in tourism—Reality or hallucination. Journal of Business Ethics, 19, 137–142.

Ford, R. C., & Richardson, W. D. (1994). Ethical decision making: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 13, 205–221.

Forsyth, D. R. (1992). Judging the morality of business practices: The influence of personal moral philosophies. Journal of Business Ethics, 11, 461–470.

Freestone, O., & Mitchell, V. (2004). Generation y attitudes towards e-ethics and internet-related misbehaviours. Journal of Business Ethics, 54, 121–128.

Fukukawa, K. (2003). A theoretical review of business and consumer ethics research: Normative and descriptive approaches. The Marketing Review, 3(4), 381–401.

Gadenne, D., Sharma, B., Kerr, D., & Smith, T. (2011). The influence of consumers’ environmental beliefs and attitudes on energy saving behaviours. Energy Policy, 39(12), 7684–7694.

García-de-Frutos, N., Ortega-Egea, J. M., & Martínez-del-Río, J. (2018). Anti-consumption for environmental sustainability: Conceptualization, review, and multilevel research directions. Journal of Business Ethics, 148, 411–435.

Gillani, A., Kutaula, S., & Budhwar, P. S. (2023). Heading home? Reshoring and sustainability connectedness from a home-country consumer perspective. British Journal of Management, 34(3), 1117–1137.

Gillani, A., Kutaula, S., Leonidou, L. C., & Christodoulides, P. (2021). The impact of proximity on consumer fair trade engagement and purchasing behavior: The moderating role of empathic concern and hypocrisy. Journal of Business Ethics, 169, 557–577.

Gohary, A., Madani, F., Chan, E. Y., & Tavallaei, S. (2023). Political ideology and fair-trade consumption: A social dominance orientation perspective. Journal of Business Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113535

Gregory-Smith, D., Manika, D., & Demirel, P. (2017). Green intentions under the blue flag: Exploring differences in EU consumers’ willingness to pay more for environmentally-friendly products. Business Ethics: A European Review, 26(3), 205–222.

Gregory-Smith, D., Smith, A., & Winklhofer, H. (2013). Emotions and dissonance in ‘ethical’ consumption choices. Journal of Marketing Management, 29(11–12), 1201–1223.

Gummerus, J., Liljander, V., & Sihlman, R. (2017). Do ethical social media communities pay off? An exploratory study of the ability of Facebook ethical communities to strengthen consumers’ ethical consumption behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 144, 449–465.

Gupta, R., Chandrasekaran, D., Sen, S., & Gupta, T. (2024). Marketing to bottom-of-the-pyramid consumers in an emerging market: The responses of mainstream consumers. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05664-5

Habib, R., White, K., Hardisty, D. J., & Zhao, J. (2021). Shifting consumer behavior to address climate change. Current Opinion in Psychology, 42, 108–113.

Hagerty, S. F., Barasz, K., & Norton, M. I. (2022). Economic inequality shapes judgments of consumption. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 32(1), 162–164.

Hammond, A. L., & Prahalad, C. K. (2004). Selling to the poor. Foreign Policy, 142(May-June), 30–37.

Hassan, L. M., Shiu, E., & Shaw, D. (2016). Who says there is an intention–behaviour gap? Assessing the empirical evidence of an intention–behaviour gap in ethical consumption. Journal of Business Ethics, 136, 219–236.

Hassan, S. M., Rahman, Z., & Paul, J. (2022). Consumer ethics: A review and research agenda. Psychology and Marketing, 39(1), 111–130.

Hill, R. P. (2005). Do the poor deserve less than surfers? An essay for the special issue on vulnerable consumers. Journal of Macromarketing, 25(2), 215–218.

Hornik, J., Cherian, J., & Madansky, M. (1995). Determinants of recycling behavior: A synthesis of research results. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 24(1), 105–127.

Hoskisson, R. E., Eden, L., Lau, C. M., & Wright, M. (2000). Strategy in emerging economies. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 249–267.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. (1986). A general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of Macromarketing, 6(1), 5–16.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. (1993). The general theory of marketing ethics: A retrospective and revision. In N. C. Smith & J. A. Quelch (Eds.), Ethics in marketing (pp. 775–784). Irwin.

Husted, B. W., & Allen, D. B. (2008). Toward a model of cross-cultural business ethics: The impact of individualism and collectivism on the ethical decision-making process. Journal of Business Ethics, 82, 293–305.

Irwin, J. (2015). Ethical consumerism isn’t dead, it just needs better marketing. Harvard Business Review, 12(January). https://hbr.org/2015/2001/ethical-consumerism-isnt-dead-it-just-needs-better-marketing

Jamal, A., Yaccob, A., Bartikowski, B., & Slater, S. (2019). Motivations to donate: Exploring the role of religiousness in charitable donations. Journal of Business Research, 103, 319–327.

Janssen, C., Vanhamme, J., Lindgreen, A., & Lefebvre, C. (2014). The catch-22 of responsible luxury: Effects of luxury product characteristics on consumers’ perception of fit with corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 119, 45–57.

Johnston, J., Szabo, M., & Rodney, A. (2011). Good food, good people: Understanding the cultural repertoire of ethical eating. Journal of Consumer Culture, 11(3), 293–318.

Jung, H. J., Kim, H., & Oh, K. W. (2016). Green leather for ethical consumers in China and Korea: Facilitating ethical consumption with value–belief–attitude logic. Journal of Business Ethics, 135, 483–502.

Kapferer, J. N. (2010). All that glitters is not green: The challenge of sustainable luxury. European Business Review, 2(4), 40–45.

Kapferer, J.-N., & Michaut-Denizeau, A. (2014). Is luxury compatible with sustainability? Luxury consumers’ viewpoint. Journal of Brand Management, 21(1), 1–22.

Karmarkar, U. R., & Bollinger, B. (2015). BYOB: How bringing your own shopping bags leads to treating yourself and the environment. Journal of Marketing, 79(4), 1–15.

Kilbourne, W., & Pickett, G. (2008). How materialism affects environmental beliefs, concern, and environmentally responsible behavior. Journal of Business Research, 61(9), 885–893.

Klöckner, C. A. (2013). A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 1028–1038.

Kolk, A., Rivera-Santos, M., & Rufín, C. (2014). Reviewing a decade of research on the “base/bottom of the pyramid” (BoP) concept. Business and Society, 53(3), 338–377.

Kolodinsky, R. W., Madden, T. M., Zisk, D. S., & Henkel, E. T. (2010). Attitudes about corporate social responsibility: Business student predictors. Journal of Business Ethics, 91, 167–181.

Kravets, O., & Sandikci, O. (2014). Competently ordinary: New middle class consumers in the emerging markets. Journal of Marketing, 78(4), 125–140.

Kutaula, S., Gillani, A., Leonidou, L. C., & Christodoulides, P. (2022). Integrating fair trade with circular economy: Personality traits, consumer engagement, and ethically-minded behavior. Journal of Business Research, 144, 1087–1102.

Lee, M. S., Fernandez, K. V., & Hyman, M. R. (2009). Anti-consumption: An overview and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 62(2), 145–147.

Li, C. X., Liu, X.-X., Ye, J., Zheng, S., & Cai, S. (2024). Ethical pursuit or personal nirvana? Unpacking the practice of Danshari in China. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05663-6

London, T., & Hart, S. L. (2004). Reinventing strategies for emerging markets: Beyond the transnational model. Journal of International Business Studies, 35, 350–370.

Lu, L.-C., Chang, H.-H., & Chang, A. (2015). Consumer personality and green buying intention: The mediate role of consumer ethical beliefs. Journal of Business Ethics, 127, 205–219.

Lu, L.-C., Rose, G. M., & Blodgett, J. G. (1999). The effects of cultural dimensions on ethical decision making in marketing: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Ethics, 18, 91–105.

Lyon, T. P., & Montgomery, A. W. (2013). Tweetjacked: The impact of social media on corporate greenwash. Journal of Business Ethics, 118, 747–757.

Ma, S., Gu, H., Hampson, D. P., & Wang, Y. (2020). Enhancing customer civility in the peer-to-peer economy: Empirical evidence from the hospitality sector. Journal of Business Ethics, 167, 77–95.

Martin, K. D., & Paul Hill, R. (2012). Life satisfaction, self-determination, and consumption adequacy at the bottom of the pyramid. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(6), 1155–1168.

McDonald, S., Oates, C. J., Young, C. W., & Hwang, K. (2006). Toward sustainable consumption: Researching voluntary simplifiers. Psychology and Marketing, 23(6), 515–534.

Mehmood, K., Iftikhar, Y., Jabeen, F., Khan, A. N., & Rehman, H. (2024). Energizing ethical recycling intention through information publicity: Insights from an emerging market economy. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05671-6

Nadeem, W., Juntunen, M., Hajli, N., & Tajvidi, M. (2021). The role of ethical perceptions in consumers’ participation and value co-creation on sharing economy platforms. Journal of Business Ethics, 169, 421–441.

Narasimhan, L., Srinivasan, K., & Sudhir, K. (2015). Marketing science in emerging markets. Marketing Science, 34(4), 473–479.

Nayak, S., Pereira, V., Kazmi, B. A., & Budhwar, P. (2024). To buy or not to buy? Exploring ethical consumerism in an emerging market—India. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05670-7

Newholm, T., & Shaw, D. (2007). Studying the ethical consumer: A review of research. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 6(5), 253–270.

Olsen, M. C., Slotegraaf, R. J., & Chandukala, S. R. (2014). Green claims and message frames: How green new products change brand attitude. Journal of Marketing, 78(5), 119–137.

Oreg, S., & Katz-Gerro, T. (2006). Predicting proenvironmental behavior cross-nationally: Values, the theory of planned behavior, and value–belief–norm theory. Environment and Behavior, 38(4), 462–483.

Osburg, V.-S., Davies, I., Yoganathan, V., & McLeay, F. (2021). Perspectives, opportunities and tensions in ethical and sustainable luxury: Introduction to the thematic symposium. Journal of Business Ethics, 169, 201–210.

Osburg, V.-S., Yoganathan, V., Bartikowski, B., Liu, H., & Strack, M. (2020). Effects of ethical certification and ethical eWOM on talent attraction. Journal of Business Ethics, 164, 535–548.

Osburg, V.-S., Yoganathan, V., Bartsch, F., Fall Diallo, M., & Liu, H. (2024). How sustainable luxury influences product value perceptions and behavioral intentions: A comparative study of emerging vs. developed markets. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05661-8

Padel, S., & Foster, C. (2005). Exploring the gap between attitudes and behaviour—Understanding why consumers buy or do not buy organic food. British Food Journal, 107, 606–625.

Papaoikonomou, E., & Alarcon, A. (2017). Revisiting consumer empowerment: An exploration of ethical consumption communities. Journal of Macromarketing, 37(1), 40–56.

Papaoikonomou, E., Ginieis, M., & Alarcón, A. A. (2023). The problematics of being an ethical consumer in the marketplace: Unpacking the concept of ethical consumer literacy. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1177/07439156231202746

Pedersen, E. R. G., Gwozdz, W., & Hvass, K. K. (2018). Exploring the relationship between business model innovation, corporate sustainability, and organisational values within the fashion industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 149, 267–284.

Pels, J., & Sheth, J. N. (2017). Business models to serve low-income consumers in emerging markets. Marketing Theory, 17(3), 373–391.

Perera, C., Auger, P., & Klein, J. (2018). Green consumption practices among young environmentalists: A practice theory perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 152, 843–864.

Perry, P., Wood, S., & Fernie, J. (2015). Corporate social responsibility in garment sourcing networks: Factory management perspectives on ethical trade in Sri Lanka. Journal of Business Ethics, 130, 737–752.

Pilaj, H. (2017). The choice architecture of sustainable and responsible investment: Nudging investors toward ethical decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics, 140, 743–753.

Prahalad, C. K., & Hart, S. (1999). Strategies for the bottom of the pyramid: Creating sustainable development. Working paper. University of Michigan. http://www.bus.tu.ac.th/usr/wai/xm622/conclude%620monsanto/strategies.pdf

Prahalad, C. K., & Lieberthal, K. (1998). The end of corporate imperialism. Harvard Business Review, 76(4), 68–80.

Prikshat, V., Patel, P., Kumar, S., Gupta, S., & Malik, A. (2024). Role of socio-cultural capital and country-level affluence in ethical consumerism. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05662-7

Ramasamy, B., & Yeung, M. (2009). Chinese consumers’ perception of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Journal of Business Ethics, 88, 119–132.

Ramasamy, B., Yeung, M. C., & Au, A. K. (2010). Consumer support for corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of religion and values. Journal of Business Ethics, 91, 61–72.

Rauch, E., Dallasega, P., & Matt, D. T. (2016). Sustainable production in emerging markets through distributed manufacturing systems (DMS). Journal of Cleaner Production, 135, 127–138.