Abstract

An understanding of how the convective boundary layer (CBL) is mixed under heterogeneous surface forcing is crucial for the interpretation of area-averaged turbulence measurements. To determine the height and degree to which a complex heterogeneous surface affects the CBL, large-eddy simulations (LES) for two days of the LITFASS-2003 experiment representing two different wind regimes were undertaken. Spatially-lagged correlation analysis revealed the turbulent heat fluxes to be dependent on the prescribed surface flux pattern throughout the entire CBL including the entrainment layer. These findings prompted the question of whether signals induced by surface heterogeneity can be measured by airborne systems. To examine this question, an ensemble of virtual flights was conducted using LES, according to Helipod flight measurements made during LITFASS-2003. The resulting ensemble-averaged heat fluxes indicated a clear dependence on the underlying surface up to the top of the CBL. However, a large scatter between the flux measurements in different ensemble runs was observed, which was the result of insufficient sampling of the largest turbulent eddies. The random and systematic errors based on the integral length scale did not indicate such a large scatter. For the given flight leg lengths, at least 10–15 statistically independent flight measurements were necessary to give a significant estimate of heterogeneity-induced signals in the CBL. The need for ensemble averaging suggests that the observed blending of heterogeneity-induced signals in the CBL can be partly attributed to insufficient averaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The blending height, \(z_{\mathrm{b}}\), refers to the height at which the influence of a heterogeneous surface gradually decreases below some threshold because of an increase in eddy size accompanied by the increased mixing of surface properties with height (Mahrt 2000). For both observational and modelling purposes it is often assumed that \(z_{\mathrm{b}}\) exists. For example, the interpretation of area-averaged flux measurements and footprint analysis is based on the assumption that the convective boundary layer (CBL) is well mixed. Therefore, a knowledge of the extent to which the CBL is mixed above a heterogeneous surface is crucial for appropriate interpretations (Meijninger et al. 2002). In numerical weather prediction (NWP) models surface heterogeneities smaller than the numerical grid size are often parametrized by flux aggregation methods such as the mosaic or tile approach, where the flux of a quantity at the first grid level is an average of the calculated surface fluxes for each patch or surface type within the grid box (Ament and Simmer 2006). This, in turn, implies that \(z_{\mathrm{b}}\) exists at the first grid level, independent of the atmospheric conditions. Other proposed aggregation methods, e.g. by Blyth (1995) or Molod et al. (2003), use an explicit blending height that does not depend on the grid size, but require explicit knowledge at which level the surface heterogeneity signals are blended.

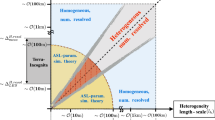

The blending-height concept is a scale-dependent issue, where blending over smaller scales occurs at lower levels compared to blending over larger scales. Depending on the scale of the surface heat-flux or roughness heterogeneity, as well as dynamic and thermodynamic parameters of the flow, various analytically derived estimates of \(z_{\mathrm{b}}\) exist and have been described in detail by Mahrt (2000) and Strunin et al. (2004).

For neutral conditions Bou-Zeid et al. (2007) confirmed the existence of \(z_{\mathrm{b}}\) in their large-eddy simulations (LES) over surface roughness heterogeneities. They also found an agreement between the observed \(z_{\mathrm{b}}\) and common analytically derived estimates. However, for convective conditions there is still no consensus on whether \(z_{\mathrm{b}}\) exists. Using LES, Brunsell et al. (2011) investigated the interaction between the atmosphere and the underlying surface for different length scales of surface heterogeneity. A wide range of length scales was covered from small-scale heterogeneities to scales up to ten times larger than the boundary-layer depth, \(z_\mathrm{i}.\) A spectral analysis showed that turbulent heat fluxes are distributed at similar length scales within the CBL, independent of the underlying heterogeneity length scale, with the exception of the lowest 100–200 m. This suggests that heat fluxes are blended above this level. However, although a spectral analysis provides information regarding the spectral energy at a certain scale, it does not indicate the flow organization with respect to the underlying surface, which might be completely different above heterogeneous surfaces compared to homogeneous surfaces. Albertson and Parlange (1999), in their LES of idealized surface heterogeneities, showed that \(z_{\mathrm{b}}\) also exists under convective conditions, except for strong convective conditions and surface heterogeneities with a horizontal length scale significantly \({>}z_\mathrm{i}.\) For such situations an influence of surface heterogeneity on the entrainment processes was also found.

If the heterogeneity length scale is \({>}z_\mathrm{i},\) secondary circulations (SC) develop that extend throughout the CBL (Shen and Leclerc 1995; Raasch and Harbusch 2001; Patton et al. 2005). Patton et al. (2005) showed that the strongest SCs occur if the ratio between the heterogeneity length scale and \(z_\mathrm{i}\) is between 4 and 9. Maronga and Raasch (2013), hereafter MR13, reported that the SCs contributed up to 20 % of the total sensible heat flux and up to 39 % of the total latent heat flux in their LES for the complex heterogeneous terrain of the LITFASS-2003 experiment (Beyrich and Mengelkamp 2006). In general, the existence of SCs throughout the bulk of the CBL conflicts with the concept of a blending height.

Using LES, van Heerwaarden and de Arellano (2008), Fesquet et al. (2009), Wang et al. (2011) and MR13 found a correlation between the local boundary-layer depth \(z_\mathrm{i,local}\) and the underlying sensible surface heat flux that produced larger values of \(z_\mathrm{i,local}\) over warmer patches and smaller values over colder patches. van Heerwaarden and de Arellano (2008) attributed the varying values of \(z_\mathrm{i,local}\) in their study of idealized heterogeneities to rising SC updrafts that led to increased entrainment above the more strongly heated patches. In contrast, MR13 attributed the varying spatial values of \(z_\mathrm{i,local}\) to the encroachment effect (Stull 1988) because the SCs correlated with the edges of the underlying surface patches in their LES and not with the centres of the surface patches as did \(z_\mathrm{i,local}\) . Both mechanisms indicate that the CBL is not well-mixed horizontally up to the top of the CBL.

The effect of heterogeneous surface forcing on the CBL was also investigated using airborne measurements. Strunin et al. (2004) observed surface heterogeneity-induced internal boundary layers that extended throughout the bulk of the CBL. Kang et al. (2007) reported spatial variations in \(z_\mathrm{i,local}\) and inferred that \(z_{\mathrm{b}}\) exceeds \(z_\mathrm{i,local}.\)Gorska et al. (2008) found spatial variability in potential temperature \(\theta \) and specific humidity \(q\) in the upper part of the CBL that correlated with the underlying surface fluxes. They attempted to estimate the local entrainment rate from airborne measurements and suggested slightly higher values above stronger heated patches. Airborne flux measurements made during LITFASS-2003 were analyzed by Bange et al. (2006) with respect to heterogeneity-induced signals in the CBL. Near the surface, sensible heat fluxes were found to be dependent on the underlying surface type. In the upper flight levels between \(0.3z_\mathrm{i}\) and \(0.6z_\mathrm{i},\) fluxes were dependent on the underlying surface type, but in some situations the fluxes indicated a well-mixed CBL. However, no clear connection could be determined between the occurrence of a well-mixed CBL and the time of day, wind speed, or wind direction. Because flight measurements are only one-dimensional samples over a limited distance and at a certain point in time, the question arises of how representative are these flux measurements.

In the present study we analyze how the correlation between the complex surface heterogeneity and the turbulent heat-flux patterns changes with height and in particular if there is a height at which the correlation vanishes. To answer these questions we conducted a spatially-lagged correlation analysis (Lohou et al. 1998, 2000) between the prescribed surface heat-flux pattern and the turbulent heat-flux patterns above the surface. The analysis was based on an ensemble of LES runs for the heterogeneous LITFASS terrain (see MR13) using forcing data from the LITFASS-2003 experiment. In a second step we identify the requirements for detecting heterogeneity-induced spatial variations in the turbulent heat fluxes from flight measurements within the CBL. An ensemble of virtual flight measurements within the LES was conducted according to the method used by Schröter et al. (2000) and compared to the flight measurements during LITFASS-2003 presented by Bange et al. (2006). On the basis of these virtual flights, we investigated why the observations during LITFASS-2003 do not show clear heterogeneity-induced spatial heat-flux variations at the upper flight levels.

Section 2 briefly describes the LES model, the heterogeneous surface forcing, and the simulated LITFASS cases. Results of the spatially-lagged correlation analysis between the prescribed surface fluxes and the turbulent fluxes within the CBL are presented in Sect. 3. The results of the virtual flight measurements are discussed in Sect. 4, and a summary and ideas for future studies are presented in Sect. 5.

2 LES Model and Simulation Set-Up

2.1 Model Description

The PArallelized LES Model (PALM) was used for the numerical simulations in this study; it solves the non-hydrostatic incompressible Boussinesq equations, with the advection terms discretized by a fifth-order scheme (Wicker and Skamarock 2002). For the time integration a third-order Runge–Kutta scheme by Williamson (1980) was used. For the simulations cyclic lateral boundary conditions were applied. Between the surface and the first grid level, Monin–Obukhov similarity theory (MOST) was applied. Detailed descriptions of PALM have been provided by Raasch and Etling (1998) and Raasch and Schröter (2001). PALM has been successfully applied for investigations of the neutrally (Letzel et al. 2008) and weakly stably stratified boundary layer (Beare et al. 2007; Steinfeld et al. 2007) as well as the homogeneously heated (Schröter et al. 2000; Raasch and Franke 2011) and heterogeneously heated CBL (Raasch and Harbusch 2001; Letzel and Raasch 2003; Inagaki et al. 2006; Steinfeld et al. 2008; Maronga and Raasch 2013) and is therefore well suited for this study.

2.2 Case Description and Simulation Set-Up

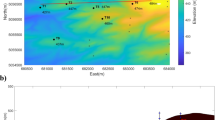

A series of LES runs for the heterogeneous LITFASS terrain and its surroundings, presented in Fig. 1 (see also Beyrich and Mengelkamp 2006, Figs. 2, 3; MR13, Fig. 1), were conducted for a daily cycle from 0500 to 1700 UTC. The initial vertical profiles of \(\theta \) and \(q\) for the entire model domain were derived from radiosonde measurements during the LITFASS-2003 experiment. The aerodynamic roughness length \(z_{0}\) for the different surface types was estimated using \(z_{0} \approx 0.1h\) after Shuttleworth et al. (1997), where \(h\) is crop height. To obtain initial steady-state profiles of the horizontal velocity components, a one-dimensional version of the PALM code was applied, using the initial profiles of \(\theta \) and \(q,\) and a mixing-length approach after Blackadar (1997). Modelling the initial wind profiles was found to be the best approach for the simulations (instead of prescribing initial wind profiles derived from radiosondes) to obtain local daytime wind profiles that were in agreement with measurements from a wind profiler and from a 99-m tower, as well as measurements from radiosondes. During LITFASS-2003, sensible and latent surface heat fluxes were measured at energy balance stations located over different surface types. The measured surface fluxes were used as surface fluxes in the LES for all patches of the respective surface type in the entire model domain. Because the surface heat-flux data are available on a 30-min basis, the values were linearly interpolated in time. Following MR13, prescribing the observed surface fluxes was found to be the best approach for the simulations, because the usage of a soil–vegetation–atmosphere transfer model would have required the input of several local vegetation and soil parameters, which were not available. As already mentioned, we applied MOST as the lower boundary condition for the momentum equations, which is actually not valid over heterogeneous terrain, even though it is commonly used. It should be noted that this might result in erroneous turbulence statistics at the lowest grid levels (which are also largely affected by the subgrid-scale model), and so should be interpreted very carefully. For a more detailed description of the initialization and implementation of surface flux and roughness heterogeneities for the different surface types, see MR13. Two LITFASS days were simulated: May 30 and June 13, which are hereafter written as LIT2E and LIT6NW, respectively; the denotation is the same as that in MR13. LIT2E was characterized by a low geostrophic wind speed of \(2\ \mathrm{m\,s^{-1}}\) from the east during the day. Figure 2 displays the surface heat fluxes for the different surface types during the course of the day. For LIT2E, the forest patches displayed the largest sensible surface heat fluxes of up to \(0.4\ \mathrm{K\,m\,s^{-1}}\) at noon, followed by barley and triticale with kinematic fluxes up to \(0.24\ \mathrm{K\,m\,s^{-1}},\) and grass, maize, as well as rape with fluxes up to \(0.16\ \mathrm{K\,m\,s^{-1}}.\) Compared to the other surface patches, the sensible heat input from the water patches was small during the whole day.

Distribution of surface types of the centred \(20 \times 20\, \mathrm{km}^2\) LITFASS terrain and surroundings (after Beyrich and Mengelkamp 2006). The white solid lines above the water, farmland and forest patches display the location of the flight legs used for the virtual measurements for LIT2E

The different surface types exhibited highly varying latent heat fluxes during the day. Rape patches displayed the largest values, whereas forest patches displayed the lowest values. In general, the differences in the surface latent heat flux between the different surface patches were less pronounced than differences in the surface sensible heat flux.

For LIT6NW the geostrophic wind was directed from the north-west at a speed of \(6\ \mathrm{m\,s^{-1}}.\) Each surface type displayed a pronounced daily cycle for the surface sensible heat flux, except for the water patches. Compared to LIT2E, the surface latent heat flux was generally larger and exhibited fewer temporal variations, with the exception of the striking peak for the forest patches at about 1000 UTC.

Detailed descriptions of the main features of the simulated CBL, the corresponding daily cycles, their agreement with the observational data, and the structure of the heterogeneity-induced SCs for the selected cases have been reported by MR13. MR13 determined a fetch that was dependent on wind speed and characterized the length scale at which SCs are affected by the upstream surface heterogeneity. For this reason, MR13 stressed the need to extend the model domain in the upwind direction to obtain a realistic local CBL structure within the domain of interest. This is of particular interest in the present comparison of the virtual flight measurements (see Sect. 4) with the flight measurements made during LITFASS-2003. Therefore, model domains of \(40 \times 40 \times 4\, \mathrm{km}^3\) for LIT2E and \(56 \times 56 \times 4\, \mathrm{km}^3\) for LIT6NW were simulated. A grid length of \(\mathrm{\Delta } x_\mathrm{i} = 40\ \mathrm{m}\) in each spatial direction was used; beyond the top of the CBL, the vertical grid was stretched to save computational resources. To enhance the statistical significance of the virtual measurements (see Sect. 4), 20 ensemble runs with individual development of the turbulent eddies but identical mean conditions were performed by imposing different initial random perturbations on the horizontal velocity fields in each ensemble run.

The three-dimensional data of vertical velocity \(w,\) \(\theta ,\) \(q,\) and the vertical heat fluxes for the entire model domain, which are required for the spatially-lagged correlation analysis (see Sect. 3), were sampled for each ensemble run. Because the LITFASS-2003 airborne flux measurements were made between 1300 and 1330 UTC, this time period was also used for the analysis of the three-dimensional data in the next section. For scaling the vertical coordinate, we used the mean boundary-layer depth during the analysis period, derived from the height of the maximum gradient of the local \(\theta \) profile following Sullivan et al. (1998). This was 1,800 m for LIT2E and 1,610 m for LIT6NW (see also MR13).

3 Spatially-Lagged Correlation Analysis

3.1 Method

In order to analyze how the turbulent vertical heat-flux patterns within the CBL depend on the underlying heterogeneous terrain, three-dimensional data for the turbulent vertical heat fluxes were required. The turbulent fraction of a quantity is defined as the deviation from a reference value; usually, in LES the horizontal mean of the respective quantity is used as a reference value. However, under horizontally heterogeneous conditions this method might fail, because the horizontal mean does not necessarily represent local conditions. Therefore, the temporal mean at each location was used as a reference value. Thus, the vertical turbulent flux of a scalar \(\psi \in \left( \theta ,q\right) \) was calculated for each discrete location in the model domain by the temporal eddy-covariance method:

where the overbar denotes a value averaged over 30 min. After calculating \(\overline{w^{\prime }\psi ^{\prime }}\) for each of the 20 ensemble runs, ensemble averaging was applied in order to eliminate randomly distributed turbulent structures that exist for longer than 30 min.

The first term on the right-hand side in Eq. 1 represents the total transport, and the second term on the right-hand side represents the mean vertical transport at a certain location. The mean vertical transport, hereafter the mesoscale flux contribution, is non-zero for the investigated cases because the SCs are nearly stationary in space for the given averaging interval. Hence, the calculated turbulent flux is only a part of the total vertical transport. However, the correlation analyses using the total fluxes produced almost identical results when only the turbulent fluxes were used, which might be due to the smaller mesoscale fluxes compared to the turbulent fluxes for the simulated days as reported in MR13. For this reason the impact of the mesoscale flux on our further analysis is of only minor importance and will be not discussed further. It should be emphasized that \(\overline{w^{\prime }\psi ^{\prime }}\) is only the resolved scale part of the flux, and in LES the turbulent transport on the grid scale is parametrized. The subgrid-scale flux contribution is negligibly small, except for the grid layers close to the surface. This is because turbulent transport is not well resolved by the numerical grid in this region due to the limited eddy size. Data analysis has shown that the subgrid-scale flux contribution is below \(5\,\%\) of the total flux above the third vertical grid layer (see also Steinfeld et al. 2007). Therefore, the subgrid-scale flux contribution is not considered further in calculations of the turbulent flux.

To investigate the dependence of the vertical turbulent flux patterns on the underlying surface fluxes, a spatially-lagged two-dimensional correlation analysis as presented by Lohou et al. (1998, 2000) was applied

where \(\varrho _{\psi _\mathrm{s},\phi }\left( \delta x,\,\delta y,\,z\right) \in [-1,1]\) is the correlation coefficient between the surface flux \(\psi _\mathrm{s}\) and the turbulent flux \(\phi \) considering the spatial displacement \(\delta x,\,\delta y\) between \(\psi _\mathrm{s}\) and \(\phi \) in the x- and y-directions. The tilde indicates the deviation from the horizontal mean value of the respective quantity; \(\delta x,\,\delta y\) as well as \(x,\,y,\,z\) are integer multiples of the numerical grid lengths \(\mathrm{\Delta } x,\,\mathrm{\Delta } y,\,\mathrm{\Delta } z,\) and \(x_{\mathrm{l}},\,x_{\mathrm{u}},\,y_{\mathrm{l}},\,y_{\mathrm{u}}\) denote the lower and upper lateral bounds of the model domain. The correlation analysis was performed for the entire domain, and cyclic conditions were applied at the lateral boundaries. For zero lag \(\varrho _{\psi _\mathrm{s},\phi }\left( 0, 0, z\right) \) is equivalent to a one-point correlation. In contrast to the one-point correlation analysis used by Albertson and Parlange (1999), the spatially-lagged correlation analysis considers the spatial displacement by horizontal advection during vertical transport and is therefore better suited for conditions with a mean flow.

3.2 Results

Henceforth the correlation coefficient between the turbulent fluxes of sensible and latent heat \(\overline{w^{\prime }\theta ^{\prime }},\) \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }},\) and the respective surface fluxes \(\overline{w^{\prime }\theta ^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0},\) \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0},\) will be abbreviated as \(\varrho _\mathrm{sens}\) and \(\varrho _\mathrm{lat},\) respectively. Figure 3a, b shows horizontal cross-sections of \(\varrho _\mathrm{sens}\) at \(0.25z_\mathrm{i}\) for LIT2E and LIT6NW; the black solid lines indicate the axis parallel to the mean wind direction that is the corresponding intersection plane in Fig. 3c and d, respectively. A significant correlation between \(\overline{w^{\prime }\theta ^{\prime }}\) and \(\overline{w^{\prime }\theta ^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) is evident at this level. The maximum of the correlation is shifted downstream along the mean wind direction because any convective plume triggered by the surface is advected downstream while moving vertically. For this reason, it is obvious that a one-point correlation would fail, especially for higher wind speeds such as for LIT6NW. Figure 3c, d shows \(\varrho _\mathrm{sens}\) as a function of height and spatial lag along the mean wind direction. Because the spatial lag along the mean wind direction does not necessarily coincide with the spatial lag \(\delta x,\,\delta y\) along the x- and y-directions, \(\varrho \) was interpolated from Cartesian to polar coordinates to obtain values along the angle corresponding with the mean wind direction. The spatial shift of the maximum correlation increases with increasing height, indicating that the turbulent heat-flux patterns are inclined along the mean wind direction. Owing to the higher mean wind speed for LIT6NW, the spatial shift is larger than that on LIT2E (inclination angle is smaller), which is particularly evident from the areas with negative values of \(\varrho _\mathrm{sens}\) that appear at the top of the CBL. The mean inclination angle determined by the surface and the lag of the maximum correlation at the top of the CBL is \(51^\circ \) and \(25^\circ \) for LIT2E and LIT6NW, which is in agreement with the angle determined by the ratio between the convective velocity scale (\(w_{*}\)) and the horizontal mean wind speed, i.e. \(\arctan (w_{*}|u|^{-1}),\) respectively. In particular for LIT6NW it is obvious that the inclination angle changes with height, indicated by the slope between the black circles that display the horizontal lag of the maximum correlation at certain height levels. From the surface up to the middle part of the CBL the inclination angle increases with increasing height, while in the upper CBL the inclination angle decreases up to the top of the CBL. Near the surface the vertical wind speed of the eddies that are responsible for the bulk of the vertical transport (thermals) is small, i.e. the horizontal shift by the horizontal mean wind is large compared to the vertical upward transport (inclination angle is small). Due to positive buoyancy the thermals are vertically accelerated, resulting in larger inclination angles with increasing height in the middle part of the CBL, while the thermals are decelerated at the top of the CBL, resulting in smaller inclination angles of the maximum correlation.

Correlation coefficients between \(\overline{w^{\prime }\theta ^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) and \(\overline{w^{\prime }\theta ^{\prime }}\) for a horizontal cross-section at \(0.25z_\mathrm{i}\) a for LIT2E, and b LIT6NW. (c) and (d) show the correlation coefficients for LIT2E and LIT6NW depending on the height and spatial lag along the mean wind direction. The black solid lines in (a) and (b) indicate the respective intersection plane for (c) and (d) and vice versa. The black circles in (c) and (d) display the lag of the maximum correlation at certain height levels. Only absolute values larger than \(0.2\) are depicted

Except for these upper parts of the CBL, \(\varrho _\mathrm{sens}\) is positive for most of the CBL for both LIT2E and LIT6NW. This implies that more strongly heated surface patches generate larger values of \(\overline{w^{\prime }\theta ^{\prime }}\) in the downstream area. The negative correlation in the entrainment layer indicates that the turbulent exchange processes at the top of the CBL are still affected by the surface heterogeneity. More strongly heated patches generate a stronger entrainment at the top of the CBL than less heated patches.

The correlation decreases with height and becomes zero at about \(0.8z_\mathrm{i}\) in both cases. This does not mean that the surface heterogeneity signal is blended. These low values are simply caused by the general linear decrease in the local sensible heat-flux profiles over different surface types, which all have zero crossing at about the same height (see Fig. 9 where the local heat-flux profiles above farmland, forest, and water patches obtained from virtual flight measurements are shown). This results in less pronounced sensible heat-flux patterns, and hence the correlation appears to decrease with height.

Furthermore, the intersection of the different local heat-flux profiles directly implies that the heat-flux divergences vary horizontally, which in turn, generates spatially differential heating and subsequent spatial variations in \(z_\mathrm{i,local}.\) These variations can be attributed to the encroachment effect, which describes the growth of \(z_\mathrm{i}\) due to pure thermodynamic heating (Stull 1988). Therefore, both entrainment and encroachment might be responsible for the spatial variations in \(z_\mathrm{i,local}\) presented by MR13. To identify which is the dominant mechanism is beyond the scope of this study, but will be investigated in a follow-up study.

Figure 4 shows the correlation coefficient between the latent heat flux \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}\) and \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) for LIT2E and LIT6NW. For LIT2E, where \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) for the different surface types varies substantially over time, a positive correlation between \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}\) and \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) exists only in the lower CBL up to \(0.1z_\mathrm{i}.\) This suggests that the surface signal is already blended above this level for the latent heat flux. However, negative values of \(\varrho _\mathrm{lat}\) occur in the upper CBL. Bange et al. (2006) and MR13 noted that \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}\) was more affected by the entrainment of dry air from the free atmosphere than by \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) during LITFASS-2003. Because the entrainment is mainly steered by \(\overline{w^{\prime }\theta ^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) with larger entrainment fluxes of sensible heat above more strongly heated patches, it can be assumed that more strongly heated patches also generate larger entrainment fluxes of latent heat. To confirm this, the correlation between \(\overline{w^{\prime }\theta ^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) and \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}\) is shown in Fig. 5. For both days a positive correlation between both quantities is evident at the top of the CBL, indicating that larger entrainment fluxes of latent heat occur above more strongly heated patches. Therefore, it can be assumed that the significant correlation in Fig. 4 between \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}\) and \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) at the top of the CBL, as well as its sign, is merely due to the Bowen ratio of the surface fluxes, instead of implying a direct physical relationship between \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) and \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}.\)

In contrast to LIT2E, LIT6NW exhibits positive values of \(\varrho _\mathrm{lat}\) throughout the CBL (see Fig. 4b), suggesting that \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}\) is controlled by \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) up to the top of the CBL. However, the entrainment effect discussed for LIT2E is also active here, making it difficult to distinguish between the two mechanisms, and in particular to decide if the direct correlation between \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}\) and \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) is lost above a certain level. Even though the direct correlation may be lost, the surface still affects the patterns in \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}\) through the entrainment at the CBL top, which correlates with \(\overline{w^{\prime }\theta ^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0},\) revealing that there is no blending height for \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}\) too.

4 Turbulent Fluxes from Virtual Flight Measurements

4.1 Flight Strategy

During the LITFASS-2003 experiment, helicopter-borne turbulence measurements with the Helipod (Bange and Roth 1999) were made. Bange et al. (2006) used the experimental data collected from flights above the main LITFASS surface types of forest, water, and farmland to investigate the blending of sensible and latent heat fluxes at different heights. For the near-surface flights between 100–160 m (about \(0.1z_{\mathrm{i}}\)), a clear dependence between the turbulent fluxes and the underlying surface type was determined. However, for LIT2E no correlation between the heat fluxes and the underlying surface types was found at the upper flight level at \(780\ \mathrm{m}\) (about \(0.45z_\mathrm{i}\)). An analysis of flights on other LITFASS days also showed no clear correlation between the heat fluxes and the underlying surface at the upper flight level.

On the basis of our previous analysis showing that heterogeneity-induced patterns in the turbulent heat fluxes extend up to the top of the CBL, we investigated whether and how heterogeneity-induced spatial variations in the heat fluxes over different land surface types can be measured and why the corresponding Helipod measurements do not show any heterogeneity-induced signals in the middle of the CBL. Therefore, virtual flight measurements were performed using the method of Schröter et al. (2000), which is described further below. To compare the virtual measurements with the Helipod measurements during LITFASS-2003, we focused on flights for LIT2E only because data from flight measurements over uniform surface patches were not available for LIT6NW.

The length of a flight leg in the LITFASS-2003 experiment was limited by the length scale of the surface heterogeneity of the LITFASS area. To keep the statistical flux error, which depends on the inverse of the leg length (Lenschow and Stankov 1986), as small as possible, only flight legs above the largest patches of the main surface types (water, farmland and forest) were chosen during LITFASS-2003 (Bange et al. 2006). The flight leg length is \(9.7\ \mathrm{km}\) for water, \(15.1\ \mathrm{km}\) for farmland, and \(13.0\ \mathrm{km}\) for forest. In terms of space and time, the virtual flight legs in the LES were the same as the actual Helipod flight legs. The locations of the legs for LIT2E are given in Fig. 1 (see also Bange et al. 2006). The virtual flights were performed between 1300 and 1330 UTC and, in contrast to the Helipod flights that had a temporal offset between flights at different height levels, virtual flights were performed simultaneously at each grid level height. On the basis of the Helipod flight speed, a virtual flight speed of \(40\ \mathrm{m\,s^{-1}}\) was chosen. During the LES, space–time series of \(w,\) \(\theta \) and \(q\) were sampled along the corresponding flight legs. Because the virtual flight positions typically did not coincide with the numerical grid of the LES, the grid point data had to be interpolated bi-linearly to the actual flight position. A sampling rate of \(1\ \mathrm{s^{-1}}\) was selected for the efficient use of the LES-generated data with respect to the mean flight speed and the horizontal grid spacing of \(40\ \mathrm{m}.\) A higher sampling rate would create aliasing effects (Schröter et al. 2000) without increasing the amount of physical information. To increase the statistical significance of the virtual flux measurements, the virtual flights were performed for each of the 20 ensemble runs. Repeating the measurement along the same flight leg within short time intervals in a single simulation was no alternative because these measurements were not statistically independent from each other due to the relatively long time scale of the large randomly distributed updrafts and downdrafts.

The spatial correlation analysis (see Sect. 3.2) for LIT2E indicated that the maximum horizontal shift of the surface signal by the mean wind was approximately \(2.5\ \mathrm{km}\) between the top of the CBL and the surface. The horizontal distance between the flight legs above farmland and forest and the next adjacent different surface type in the upwind region of the respective legs was about twice the distance of this maximum horizontal shift. Therefore, the adjacent surface types should not have affected the virtual flux measurements on these flight legs. However, the leg over water might have been affected at higher levels by the adjacent forest and farmland patches east of the lake, because the lake is narrow in width and the horizontal distance between the leg and the eastern lakeside was partly less than \(2.0\ \mathrm{km}.\)

For the sake of clarity we will briefly outline the rest of Sect. 4. Section 4.2 is concerned with the flux calculation and error estimation, as well as with the necessity of ensemble averaging to reduce the uncertainty of the virtually measured fluxes. In Sect. 4.3 the ensemble-averaged fluxes are compared with the observations. Section 4.4 shows that single legs are not capable of capturing heterogeneity-induced signals and discusses the reasons for this, while Sect. 4.5 is concerned with the failure of the inferred error estimates to indicate the large uncertainty of the single leg flux measurements.

4.2 Flux Calculation and Error Estimation

Turbulent vertical sensible and latent heat fluxes were determined from the virtually sampled space–time series using the eddy-covariance method. The turbulent fluctuations were calculated by removing the linear trend and the mean value from the space–time series of the respective variable. The instantaneous turbulent vertical scalar flux

was calculated by multiplying the resulting space–time series of the turbulent fluctuations \(w^{\prime \prime }\) and \(\psi {^{\prime \prime }}.\) Finally, the kinematic fluxes of sensible and latent heat were determined by averaging \(\langle \,\,\rangle \) over the leg length:

where it is important to note that \(F\) is only the resolved scale part of the turbulent flux. However, as already mentioned in Sect. 3.1, the subgrid-scale flux contribution becomes negligibly small above the third vertical grid level (\(120\ \mathrm{m}\)). Therefore, the subgrid-scale flux contribution was not considered in the flux and error calculations.

The flux itself is subject to errors. Owing to limited leg lengths, sampling is often inadequate across all the scales that contribute to the flux, especially on the largest turbulence scales that scale with \(z_\mathrm{i}\) (Mahrt 1998). A systematic difference between the flux \(F\) and the ‘true flux’ \(F_{\mathrm{true}}\)

is referred to as the systematic error \(\mathrm{\Delta } F\) (Lenschow et al. 1994). Generally, the ‘true flux’ is unknown in experiments and an estimation of \(\mathrm{\Delta } F\) is required. Lenschow et al. (1994) derived \(\mathrm{\Delta } F\) on the basis of Lumley and Panofsky (1964), and Lenschow and Stankov (1986):

where \(L_\mathrm{av}\) denotes the size of the averaging interval (leg length) and \(\rho _{w,\psi }\) is the correlation coefficient between \(w\) and \(\psi \) at temporal lag zero. It should be noted that \(\rho _{w,\psi }\) is based on the values of the respective space–time series and should not be confused with the spatial correlation coefficient \(\varrho \) used in Sect. 3. The integral length scale \(I_{f}\) of the instantaneous flux \(f\) can be considered as the maximum spatial shift for which \(f\) is relatively well correlated with itself (Lothon et al. 2007). \(I_{f}\) was calculated from the integral of the spatial autocorrelation function of \(f\)

where \(\langle {f}^{^{\prime \prime }2}\rangle \) denotes the variance of flux \(F,\) \(r\) is the location in the space–time series, \(r^{\prime }\) is the spatial shift, and \(r_\mathrm{0}\) is the spatial shift of the first zero crossing of the autocorrelation function of \(f.\)Mann and Lenschow (1994) noted that the autocorrelation function of \(f\) often behaves in a ‘wild’ fashion, which is the reason why \(I_f\) is difficult to determine, especially if the flux is small (Lothon et al. 2007) and the autocorrelation function does not cross zero. Therefore, Lenschow et al. (1994) defined an upper limit for \(I_{f}\)

using the more commonly available and robust integral length scales, \(I_w,\,I_{\psi }\) for \(w\) and \(\psi ,\) respectively. Inserting Eq. 8 into Eq. 6 leads to the final expression for the upper limit of the systematic error

Furthermore, the random flux error \(\sigma _F\) is defined as the standard deviation of the flux

which is expressed in terms of the integral length scale and the averaging length. Lenschow et al. (1994) used a different approximation for \(I_{f}\) that is smaller than the approximation in Eq. 8 to estimate \(\sigma _F.\) So as to not underestimate \(\sigma _F,\) the approximation of \(I_{f}\) for \(\sigma _F\) by Lenschow et al. (1994) was replaced by Eq. 8 according to Bange et al. (2002). The resulting estimate we used for the upper limit of the random flux error is

The total flux error \(E\) of the flux measurement is the sum of \(\mathrm{\Delta } F\) and \(\sigma _F.\)

Figure 6 shows the ensemble-averaged integral length scales for the sensible and latent heat fluxes, \(I_{{w^{\prime \prime }\theta ^{\prime \prime }}}\) and \(I_{{w^{\prime \prime }q^{\prime \prime }}},\) respectively. The largest integral length scales occur in the middle of the CBL, whereas the smallest scales occur near the surface as well as around the top of the CBL. For the forest and the farmland leg \(I_{{w^{\prime \prime }q^{\prime \prime }}}\) is slightly larger than \(I_{{w^{\prime \prime }\theta ^{\prime \prime }}}\) within the CBL, according to the results of Uhlenbrock et al. (2004) and MR13, who found that the spatial scales in \(q\) are larger than those in \(\theta \) above the heterogeneous LITFASS terrain.

Figure 7 shows the random and systematic errors of the virtually measured sensible heat-flux profiles for each of the 20 ensemble runs for the forest leg. In general, the largest errors occur in the lower CBL as well as at the top of the CBL. \(\mathrm{\Delta } F\) is about one order of magnitude smaller than \(\sigma _F\) for the different ensemble members. This suggests that the virtually measured fluxes do not deviate substantially from the ‘true flux’ due to insufficient sampling of the largest turbulent eddies. At the top of the CBL some of the measurements exhibit a peak in \(\mathrm{\Delta } F\) and \(\sigma _F.\) These peaks are attributed to the low absolute values of \(\rho _{w,\psi }\) in the stably stratified region within and above the entrainment zone.

In contrast to the small systematic errors, the random errors of the 20 single flight leg measurements show a much larger scatter, ranging from relatively small values up to values of \(0.14\ \mathrm{K\,m\,s^{-1}},\) which is on the order of the flux itself.

To investigate how the fluxes depend on the underlying surface type, it is essential to reduce this large uncertainty in the measured flux. In LES, this can be easily achieved by averaging over different realizations of the flux. The ‘true flux’ is calculated by ensemble-averaging over the 20 statistically independent virtual flux measurements. Figure 8 shows how the ensemble average converges to the value of the ‘true flux’ with an increasing number of ensemble members. Because the convergence of the ensemble average depends on the choice and the order of the ensemble members, those combinations of ensemble members are shown that give the maximum deviation of all possible combinations, i.e. the worst case. With more than 10–15 ensemble members, the change in the ensemble average becomes small, which indicates a sufficient convergence. A further increase in the number of ensemble members would not significantly change the ensemble-averaged flux. This justifies the use of the flux averaged over 20 ensemble members to represent the ‘true flux.’

Maximum possible deviation of the flux \(F_\mathrm{i},\) averaged over \(i\) ensemble members, from the flux \(F_\mathrm{20},\) averaged over 20 ensemble members, shown for a \(\langle w^{\prime \prime }\theta ^{\prime \prime }\rangle \) and b \(\langle w^{\prime \prime }q^{\prime \prime }\rangle \) for each surface type. The height levels of the depicted virtual legs are identical to the height levels of the Helipod legs during LITFASS-2003

Figure 8 also indicates that some single leg flux measurements deviate substantially from the ensemble-averaged values (for example, for the farmland, the single leg measured sensible heat flux deviates by about \(0.1\ \mathrm{K\,m\,s}^{-1}\) from the ‘true flux’). Before the flux measurements from single flight legs and their representativeness of the ‘true flux’ are further investigated in Sect. 4.4, the ensemble-averaged flux profiles are discussed.

4.3 Comparison of Ensemble-Averaged LES Fluxes and Observed Fluxes

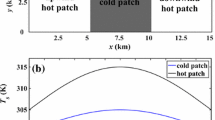

Figure 9 shows the ensemble-averaged sensible and latent heat-flux profiles calculated from the virtual flight measurements for LIT2E. The sensible heat-flux profiles for the three surface types differ throughout the CBL. The near-surface flux is largest above the forest \((0.3\ \mathrm{K\,m\,s^{-1}}),\) significantly smaller above the farmland \((0.15\ \mathrm{K\,m\,s^{-1}}),\) and almost negligible above water. The sensible heat fluxes above the forest and farmland decrease almost linearly with height, which is typical for the CBL, and display a minimum with negative values in the entrainment layer. Both profiles almost coincide within the entrainment layer, but the forest profile indicates a slightly larger entrainment, which is in agreement with the results of the spatially-lagged correlation analysis in Sect. 3.2. In contrast, the profile over water has mostly positive values at these heights, indicating no entrainment at all. These three sensible heat-flux profiles clearly show that a well-mixed layer in the middle of the CBL does not exist.

Ensemble-averaged vertical profiles of a \(\langle w^{\prime \prime }\theta ^{\prime \prime }\rangle \) and b \(\langle w^{\prime \prime }q^{\prime \prime }\rangle ,\) calculated from 20 virtual flights during the LES for LIT2E above water, farmland and forest. Coloured symbols represent the measured fluxes during LITFASS-2003 including their corresponding flux errors. It should be noted that the error bars for the measurements above water are smaller than the symbol. The thin black vertically orientated lines indicate the zero line

In contrast to these ensemble-averaged virtual measurements, the Helipod fluxes plotted in Fig. 9a (see also Bange et al. 2006) suggest that the CBL is already well mixed at \(0.45z_\mathrm{i}.\) For the water and farmland leg the Helipod and the ensemble-averaged virtual measurements agree fairly well. However, the Helipod flux for the forest leg at the upper level deviates substantially from the virtually measured ‘true flux’ and is even smaller than the farmland flux measured at the same level. Because the respective Helipod flux errors indicate only a small uncertainty, Bange et al. (2006) concluded that the measured fluxes are close to the respective ‘true fluxes.’ These discrepancies between the Helipod fluxes and the virtual ensemble-averaged fluxes raise issues regarding how representative a single leg flux measurement for the ‘true flux’ is, and how reliable the respective calculated flux errors really are. We will present detailed analyses of these issues in Sects. 4.4 and 4.5, respectively.

The real and ensemble-averaged virtual measured latent heat fluxes in Fig. 9b clearly do not have a large dependence on the underlying surface type below \(0.5z_\mathrm{i}.\) This is attributed to the relatively small differences in \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) among the different surface types (see Fig. 2). Above \(0.5z_\mathrm{i}\) the flux profiles start to differ significantly with increasing height. In particular, within the CBL, the latent heat flux over the farmland and forest increases, whereas it remains close to zero above water. This behaviour is not attributed to \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0},\) but rather to \(\overline{w^{\prime }\theta ^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0},\) as mentioned in Sect. 3.2. The increased entrainment of sensible heat at the top of the CBL over warmer surface patches causes a stronger entrainment of dry air from the free atmosphere into the CBL. As a result, the largest latent heat-flux values in the upper CBL can be found above the forest, and the lowest above water.

For the sake of completeness, the positive and negative peaks in the sensible and latent heat flux above water between \(0.9z_\mathrm{i}\) and \(1.1z_\mathrm{i}\) are addressed. Further LES data analysis (not shown) indicated that these peaks can be explained by thermals that originate from the adjacent forest patches east of the lake (see Fig. 1). These thermals penetrate deeply into the stably stratified layer and due to negative buoyancy, cold and moist downdrafts develop downstream of the updrafts. Owing to the westward shift caused by the mean wind, these local cold and moist downdrafts coincide with the location of the water leg and are captured as a turbulent flux. Because there is almost no convection from below above the lake (the flux is nearly zero throughout the complete CBL), there is no other flux contribution, e.g., by uprising thermals that compensate for flux contributions from cold and moist downdrafts, resulting in such peaks.

4.4 How Representative are Single Leg Turbulent Heat-Flux Measurements?

Figure 10a–c shows the 20 single leg flux profiles above the three surface types. At a certain height the single leg fluxes above a certain surface display a large degree of scatter. In particular, for the farmland and forest legs, the scatter between the respective single leg fluxes above one surface type can be larger than the absolute difference between the respective ‘true fluxes’ of different surface types. This can easily lead to the situation that a single leg measured flux above the forest is smaller than a single leg measured flux above the farmland. The possibility that such situations occur becomes greater with increasing height, where the absolute difference between the ‘true fluxes’ above forest and farmland decreases with height, while the scatter between single leg measurements above the same surface type remains large. These results clearly indicate that single leg flux measurements are not suitable for capturing heterogeneity-induced signals within the CBL. This is particularly true for the Helipod fluxes at the upper flight level that indicate a well-mixed CBL, whereas the ‘true fluxes’ indicate that the CBL at this height is not mixed at all.

Vertical profiles of \(\langle w^{\prime \prime }\theta ^{\prime \prime }\rangle \) for the virtual single leg flux measurements (thin dashed lines) as well as for the respective ensemble average (thick solid line) above a water, b farmland and c forest. The gray shaded area shows the total flux error for one of the 20 single leg flux profiles. The Helipod fluxes and their corresponding total errors are also shown as blue symbols

The ratio between the length of the legs and \(z_\mathrm{i}\) is about 6–8. It is obvious that the convective plumes and thermals that scale with \(z_\mathrm{i}\) and that are responsible for the bulk of the vertical transport are not adequately sampled on such short legs. Depending on how many convective elements are sampled along the leg, the measured flux will be overestimated or underestimated, which explains the large scatter between the single leg measurements from different ensemble runs.

For this reason, the single leg Helipod flux measurements during LITFASS-2003, presented by Bange et al. (2006), may have much larger uncertainties than originally assumed. Therefore, the conclusions that Bange et al. (2006) derived from the data, e.g., that the signals from the larger surface patches of the LITFASS terrain blend within the lower half of the CBL, should be carefully reviewed.

To overcome the problem of insufficient sampling over limited averaging lengths, averaging over statistically independent flux measurements is required. Figure 8 reveals that several flights are necessary to significantly reduce the influence of the insufficient sampling on the resulting flux. Although it is difficult to exactly determine the number of flights required, it is obvious that for the given leg lengths of about \(10\ \mathrm{km}\) at least 10–15 statistically independent measurements are required. While obtaining statistically independent measurements for a given leg is relatively simple with LES, it is quite difficult in field campaigns, where additional measurements can only be obtained by carrying out further flights with a temporal offset. Considering the non-stationarity due to the daily cycle, these flight measurements should be carried out during a limited time period. However, measurements along the same leg within a limited time period are statistically not independent, if the time interval between the measurements is smaller than the convective time scale that determines the lifetime of the randomly distributed large updrafts and downdrafts. For a typical convective time scale of 30 min, 10 independent flight legs would require a time interval of 5 h, which is a significant part of the daily cycle.

Strong mean boundary-layer flow may improve the situation by rapidly advecting updrafts and downdrafts so that consecutive flights would not measure the same drafts, even if the interval between the flights is smaller than the convective time scale.

Another way to conduct the required number of flights during a limited time period would be to fly several legs above different patches of identical surface type and comparable size. However, depending on the local structure of the SCs, which might be different over different patches, the success of this procedure is not necessarily guaranteed because flux contributions from the SCs can introduce an additional variability.

4.5 How Reliable are the Estimated Flux Errors?

The grey-shaded areas in Fig. 10 show the range of the total flux error for a sensible heat-flux profile from a single leg of one of the ensemble runs. It is evident that the ‘true flux’ (the average over the 20 ensemble runs, depicted by the thick solid line in Fig. 10) often lies outside of the error range. In particular, over water the ‘true flux’ is almost always outside the depicted error range of the single leg flux profile. Data analysis of the single leg fluxes and the errors indicated that in about \(50\,\%\) of all cases the ‘true flux’ is outside the error range of the single leg flux measurements for each of the three legs (not shown). This shows that the total flux error does not necessarily indicate how large the uncertainties of the flux measurements really are. This, in turn, contradicts the common assumption that large deviations of a single leg measurement from the ‘true flux’ coincide with a large total flux error, i.e., that there is a strong positive correlation between the total flux error \(E\) and the deviation \(\mathrm{\Delta }\!F_\mathrm{true}\) of the single leg flux from the ‘true flux.’ In order to quantify the real relationship between these quantities, the correlation coefficient \(\rho _{_{E,\mathrm{\Delta }\!F_\mathrm{true}}}\) was calculated from the LES data and is presented in Fig. 11; \(\rho _{_{E, \mathrm{\Delta }\!F_\mathrm{true}}}\) clearly varies with height, but with no obvious trend. Values of \(\rho _{_{E, \mathrm{\Delta }\!F_\mathrm{true}}}\) range between \(0\) and \(0.5,\) except for the forest leg where even negative values occur. This clearly demonstrates that the calculated total flux error is not an appropriate measure to quantify the uncertainty of the flux measurement for the given legs.

Vertical profiles of the correlation coefficient between the total flux errors and the deviations of the single leg measured fluxes from the ‘true flux’ at the respective height for a \(\langle w^{\prime \prime }\theta ^{\prime \prime }\rangle \) and b \(\langle w^{\prime \prime }q^{\prime \prime }\rangle \)

This unexpected conclusion can be attributed to the following reasons. The calculation of the flux error is based on the assumption that all turbulent scales contributing to the flux are sufficiently well sampled (Lenschow et al. 1994). However, this is not the case for the given legs because their lengths are too short to sufficiently capture the large convective eddies in the CBL. Because the error estimates do not consider this additional systematic flux sampling error, they are also not capable of indicating this additional uncertainty. Furthermore, the calculated systematic and random flux errors, which are expressed in terms of the integral length scale \(I_{f}\) of the flux, are based on the measurement itself; hence they are also subject to sampling errors like the flux itself (Mahrt 1998). For these reasons, the resulting systematic and random error estimates are not adequate for such short legs.

In order to capture heterogeneity-induced heat-flux patterns within the CBL at different heights with airborne measurements, the flight legs have to be located above different surface types. Because the length scale of the underlying surface types is limited, the lengths of the legs are also limited. This, in turn, leads to insufficient sampling resulting in a large uncertainty of the fluxes. However, for the aforementioned reasons, the flux errors cannot indicate this large uncertainty. Since errors based on the integral length scale provide no reliable information about the uncertainty of the flux measurement, these estimated uncertainties should be interpreted very carefully for short legs. Although the small errors calculated for the Helipod fluxes (see Fig. 9) suggest that the measured fluxes can be trusted, our analysis clearly demonstrates the failure of the error estimates to quantify the large flux uncertainties, which can result in incorrect physical interpretations of CBL structure. Therefore, the uncertainty of the measured flux has to be better quantified for short legs, by carrying out more statistically independent flights at a certain level to increase the statistical significance of the measurement.

5 Summary

This study investigated how the turbulent heat fluxes in the CBL correlate with the heterogeneous surface heat-flux patterns. Using LES, two days of the LITFASS-2003 experiment were simulated, one characterized by a low wind speed of \(2\ \mathrm{m\,s^{-1}},\) the other by a larger wind speed of \(6\ \mathrm{m\,s^{-1}}.\) A spatially-lagged correlation analysis between the prescribed sensible and latent surface heat fluxes and the corresponding turbulent vertical heat fluxes above the surface indicated that the surface heterogeneity pattern extends throughout the complete CBL for both fluxes, but particularly for the sensible heat flux. A correlation was even found between \(\overline{w^{\prime }\theta ^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) and the entrainment fluxes, indicating that stronger entrainment occurs above more strongly heated surface patches. In contrast to the sensible heat flux, the correlation between \(\overline{w^{\prime }q^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}\) and the latent heat-flux patterns vanished in the lower half of the CBL. In the upper half of the CBL the latent heat-flux patterns were largely correlated with the entrainment fluxes, which in turn correlated with \(\overline{w^{\prime }\theta ^{\prime }}_\mathrm{0}.\) The correlation analysis revealed that a blending height for the sensible and latent heat fluxes does not exist. We emphasize that this should be mainly interpreted with respect to the larger-scale heterogeneities of the LITFASS terrain and not for scales in the range of a few hundred metres.

In larger-scale models the heterogeneous land surface and its interaction with the atmosphere is commonly treated by flux aggregation methods that assume blending below or at the first grid level for each atmospheric situation. Hence, the use of aggregation methods with explicit blending heights would improve the representation of land-atmosphere interactions in larger-scale models, as already reported by Molod et al. (2003), who found more realistic precipitation patterns when using an aggregation method with an explicit blending height. Furthermore, the correlation analysis showed that a heterogeneous surface forcing affects the entrainment processes, which in turn can affect the dynamics and even the mean state of the CBL. For example, a locally increased entrainment above more strongly heated patches can slightly stabilize the CBL from above, which in turn could counteract the convective updrafts. However, it has not been sufficiently clarified in the literature whether and how heterogeneous surface forcing affects the area-averaged entrainment. This issue will be further analysed in a follow-up study.

To investigate whether airborne measurements are able to capture surface heterogeneity-induced heat-flux patterns in the CBL, an ensemble of 20 statistically independent virtual flight measurements was carried out and compared to Helipod flight measurements during LITFASS-2003. The ensemble-averaged virtual measurements showed that the vertical turbulent heat fluxes clearly depend on the underlying surface type throughout the entire CBL. However, the scatter between single leg flux measurements above a certain surface from different ensemble runs was quite large and partly even larger than the differences between the ‘true fluxes’ above the different surface types. Since the length of the legs was limited by the extent of the underlying surface patches, the ratio between the length of the given legs and \(z_\mathrm{i}\) was only about 6–8, leading to an insufficient sampling of the largest turbulent eddies contributing to the flux, which in turn caused the large scatter. This clearly demonstrates that single leg flights are not suitable for capturing heterogeneity-induced turbulent heat-flux patterns in the CBL.

Based on the integral length scale of the flux, systematic and random errors for the virtual single leg fluxes were calculated according to Lenschow et al. (1994). It was shown that the flux errors are not appropriate for quantifying the uncertainty of the flux measurement for the given legs. Because the calculation of the integral length scale is based on the measurement itself, it is also subject to insufficient sampling of the largest turbulent eddies in the CBL. Furthermore, the calculation of the flux error is based on the assumption that all turbulent scales contributing to the flux are sufficiently sampled. However, this assumption was not valid for the given legs. For these reasons, the resulting systematic and random errors were not capable for indicating the large uncertainty in the single leg flux measurements.

It was shown that for the given legs at least 10–15 statistically independent flux measurements at a certain height would be required to determine the ‘true flux,’ which is in turn necessary to confirm heterogeneity-induced flux differences within the CBL. For real measurements it would be quite challenging to carry out the required number of flights. To ensure statistically independent flux measurements, the time interval between the measurements has to be larger than the convective time scale. Because the fluxes will change due to the daily cycle, a possible way to conduct the required number of flights during a limited time period would be to fly several legs above different patches of identical surface type and comparable size. However, depending on the local structure of the SCs, which might vary over different patches, the success of this procedure is not necessarily guaranteed because flux contributions from the SCs can introduce an additional variability.

This study has shown that LES combined with virtual measurements is a useful tool for interpreting observations as well as for detecting systematic errors. In particular, it has shown that fluxes calculated from single legs of limited length are not capable of capturing heterogeneity-induced effects on the CBL structure. Further research is needed to optimize strategies for turbulence measurements in order to provide observational evidence of heterogeneity-induced effects on the CBL.

References

Albertson J, Parlange M (1999) Natural integration of scalar fluxes from complex terrain. Adv Water Res 23:239–252

Ament F, Simmer C (2006) Improved representation of land-surface heterogeneity in a non-hydrostatic numerical weather prediction model. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 121:153–174

Bange J, Roth R (1999) Helicopter-borne flux measurements in the nocturnal boundary layer over land—a case study. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 92:295–325

Bange J, Beyrich F, Engelbart D (2002) Airborne measurements of turbulent fluxes during a case study about method and significance. Theor Appl Climatol 73:35–51

Bange J, Spieß T, Herold M, Beyrich F, Hennemuth B (2006) Turbulent fluxes from Helipod flights above quasi-homogeneous patches within the LITFASS area. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 121:127–151

Beare R, Cortes M et al (2007) An intercomparison of large-eddy simulations of the stable boundary-layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 118:247–272

Beyrich F, Mengelkamp H (2006) Evaporation over a heterogeneous land surface: \(\text{ Eva }\_\text{ GRIPS }\) and the LITFASS-2003 experiment: an overview. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 121:5–32

Blackadar A (1997) Turbulence and diffusion in the atmosphere. Springer, Berlin, 185 pp

Blyth EM (1995) Using a simple SVAT scheme to describe the effect of scale on aggregation. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 72:267–285

Bou-Zeid E, Parlange M, Meneveau C (2007) On the parameterization of surface roughness at regional scales. J Atmos Sci 64:216–227

Brunsell N, Mechem D, Anderson M (2011) Surface heterogeneity impacts on boundary layer dynamics via energy balance partitioning. Atmos Chem Phys 11:3403–3416

Fesquet C, Dupont S, Drobinski P, Dubos T, Barthlott C (2009) Impact of terrain heterogeneity on coherent structure properties: numerical approach. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 133:71–92

Gorska M, Vila-Guerau de Arellano J, LeMone M, van Heerwaarden C (2008) Mean and flux horizontal variability of virtual potential temperature, moisture, and carbon dioxide: aircraft observations and LES study. Mon Weather Rev 136:4435–4451

Inagaki A, Letzel MO, Raasch S, Kanda M (2006) Impact of surface heterogeneity on energy imbalance: a study using LES. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 84:187–198

Kang S, Davis K, LeMone M (2007) Observations of the ABL structures over a heterogeneous land surface during \(\text{ IHOP }\_\text{2002 }\). J Hydrometeorol 8:221–244

Lenschow DH, Stankov B (1986) Length scales in the convective boundary layer. J Atmos Sci 43:1198–1209

Lenschow DH, Mann J, Kristensen L (1994) How long is long enough when measuring fluxes and other turbulence statistics. J Atmos Ocean Technol 11:661–673

Letzel MO, Raasch S (2003) Large eddy simulation of thermally induced oscillations in the convective boundary layer. J Atmos Sci 60:2328–2341

Letzel MO, Krane M, Raasch S (2008) High resolution urban large-eddy simulation studies from street canyon to neighbourhood scale. Atmos Environ 42:8770–8784

Lohou F, Druilhet A, Campistron B (1998) Spatial and temporal characteristics of horizontal rolls and cells in the atmospheric boundary layer based on radar and in situ observations. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 89:407–444

Lohou F, Druilhet A, Campistron B, Redelspergers K, Said F (2000) Numerical study of the impact of coherent structures on vertical transfers in the atmospheric boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 97:361–383

Lothon M, Couvreux F, Donier S, Guichard F, Lacarrere P, Lenschow DH, Noilhan J, Said F (2007) Impact of coherent eddies on airborne measurements of vertical turbulent fluxes. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 124:425–447

Lumley L, Panofsky H (1964) The structure of atmospheric turbulence. Wiley, New York, 299 pp

Mahrt L (1998) Flux sampling errors for aircraft and towers. J Atmos Ocean Technol 15:416–429

Mahrt L (2000) Surface heterogeneity and vertical structure of the boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 96:33–62

Mann J, Lenschow DH (1994) Errors in airborne flux measurements. J Geophys Res D 99:14519–14526

Maronga B, Raasch S (2013) Large-eddy simulations of surface heterogeneity effects on the convective boundary layer during the LITFASS-2003 experiment. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 146:17–44

Meijninger W, Hartogensis O, Kohsiek W, Hoedjes K, Zuurbier R, de Bruin H (2002) Determination of area-averaged sensible heat fluxes with a large aperture scintillometer over a heterogeneous surface—Flevoland field experiment. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 105:37–62

Molod A, Salmun H, Waugh DW (2003) A new look at modeling surface heterogeneity: extending its influence in the vertical. J Hydrometeorol 4:810–825

Patton E, Sullivan P, Moeng C (2005) The influence of idealized heterogeneity on wet and dry planetary boundary layers coupled to the land surface. J Atmos Sci 62:2078–2097

Raasch S, Etling D (1998) Modeling deep ocean convection: large eddy simulation in comparison with laboratory experiments. J Phys Oceanogr 28:1786–1802

Raasch S, Franke T (2011) Structure and formation of dust devil-like vortices in the atmospheric boundary layer: a high-resolution numerical study. J Geophys Res 116: D16 120

Raasch S, Harbusch G (2001) An analysis of secondary circulations and their effects caused by small-scale surface inhomogeneities using large-eddy simulation. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 101:31–59

Raasch S, Schröter M (2001) Palm—a large-eddy simulation model performing on massively parallel computers. Meteorol Z 10:363–372

Schröter M, Bange J, Raasch S (2000) Simulated airborne flux measurements in a LES generated convective boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 95:437–456

Shen S, Leclerc M (1995) How large must surface inhomogeneities be before they influence the convective boundary layer structure? A case study. Q J R Meteorol Soc 121:1209–1228

Shuttleworth W, Yang Z, Arain M (1997) Aggregation rules for surface parameters in global models. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 1:217–226

Steinfeld G, Letzel MO, Raasch S, Kanda M, Inagaki A (2007) Spatial representativeness of single tower measurements and the imbalance problem with eddy-covariance fluxes: results of a large-eddy simulation study. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 123:78–98

Steinfeld G, Raasch S, Markkanen T (2008) Footprints in homogeneously and heterogeneously driven boundary layers derived from a Lagrangian stochastic particle model embedded into large-eddy simulation. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 129:225–248

Strunin M, Hiyama T, Asanuma J, Ohata T (2004) Aircraft observations of the development of thermal internal boundary layers and scaling of the convective boundary layer over non-homogeneous land surfaces. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 111:491–522

Stull R (1988) An introduction to boundary layer meteorology. Kluwer, Dordrecht, 666 pp

Sullivan P, Moeng C, Stevens B, Lenschow D, Mayor S (1998) Structure of the entrainment zone capping the convective atmospheric boundary layer. J Atmos Sci 55:3042–3064

Uhlenbrock J, Raasch S, Hennemuth B, Zittel P, Meijninger W (2004) Effects of land surface heterogeneities on the boundary layer structure and turbulence during LITFASS-2003: large-eddy simulations in comparison with turbulence measurements. In: 16th Symposium on boundary layers and turbulence, American Meteorological Society, Portland (Maine), paper 9,3

van Heerwaarden C, Vila-Guerau de Arellano J (2008) Relative humidity as an indicator for cloud formation over heterogeneous land surfaces. J Atmos Sci 65:3263–3277

Wang C, Tian W, Parker D, Marsham J, Guo Z (2011) Properties of a simulated convective boundary layer over inhomogeneous vegetation. Q J R Meteorol Soc 137:99–117

Wicker L, Skamarock W (2002) Time-splitting methods for elastic models using forward time schemes. Mon Weather Rev 130:2088–2097

Williamson JH (1980) Low-storage Runge–Kutta schemes. J Comput Phys 35:48–56

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under grant RA 617/21-1. All simulations were performed on the IBM Power6 at The German Climate Computing Center (DKRZ), Hamburg. We appreciate the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive and valuable comments that helped to improve the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sühring, M., Raasch, S. Heterogeneity-Induced Heat-Flux Patterns in the Convective Boundary Layer: Can they be Detected from Observations and is There a Blending Height?—A Large-Eddy Simulation Study for the LITFASS-2003 Experiment. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 148, 309–331 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-013-9822-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-013-9822-1