Abstract

Insect faunas from a Spanish and a Dutch shipwreck, Angra D and Angra C, recovered from a bay on Terceira island, Angra do Heroísmo, in the Azores, and dated to c. 1650 CE, provide information about the onboard ecology of seventeenth century shipping vessels and the role of these ships and of contemporary maritime routes in biological invasions. In addition to evidence for foul conditions, there is evidence for similar insect faunas on both these ships. The assemblages include the earliest records of the now cosmopolitan synanthropic scuttle fly Dohrniphora cornuta (Bigot) which was probably introduced through trade from southeast Asia to Europe. The presence of the American cockroach, Periplaneta americana (L.) from Angra D, in the context of other sixteenth and seventeenth century records from shipwrecks, gives information about its spread to North America and Europe through transatlantic and transpacific trade, hitching a ride with traded commodities. The insect data point to the importance of introduced taxa on traded commodities and ballast, transported from port to port, and the role of ports of call like Angra in the Azores, as hot spots for biological invasions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In a homogenized world where there are many thousands of species’ invasions showing little indication of a declining rate (Seebens et al. 2015, 2018), understanding the pathways and timing of initial introductions of insects to new areas provides the backdrop for assessing the ongoing process of biotic change. Introductions via maritime routes are responsible for continuous tranches of stowaways which eventually may become established in new areas often at the expense of the native fauna. Although the discussion on insect biological invasions tends to focus on recent decades, accidental travellers on shipping vessels have a long history. When it comes to historical biogeography, the suggestion that a wooden sailing vessel around 1750 could transport up to 156 species of invertebrates, algae and plants, provides a glimpse of the implications of maritime trade for biological invasions (Carlton 1999). In depth understanding of ecosystems on ships and conditions which facilitated these invasions is needed.

What is often called the Age of Discovery (15–18th century CE) led to the European exploration and colonization of much of the rest of the world, to new trading routes and transoceanic introductions of a large range of taxa. The limited data that we have for maritime introductions during this period, come from sparse records of insect stowaways from shipwrecks, often found sunk near a harbour, where they had been seeking to find shelter during a sudden storm, and the occasional ship’s log or diary entry (Banks 1797).

On these maritime routes, the islands which acted as obligatory revictualling stops during the long journey between the West Indies, Africa, Europe and the Americas (Garcia 2017a) played an important role as hubs also for invasive species. Imported taxa could become established on these, as a result of frequent introductions and spread from these hop-off/hop-on points to new destinations.

This paper presents new data on insect faunas from two seventeenth century shipwrecks, Angra C and Angra D, from one of the key ports for transatlantic trade, Angra do Heroísmo on Terceira island, in the Azores. It summarises evidence on previous maritime introductions via the sea during the late medieval period, discusses conditions on the shipping vessels and assesses the origins of some now cosmopolitan taxa in relation to the role of trade and maritime trading routes.

Study location

Terceira is an island in the Azorean archipelago, which is located to the west of the Iberian peninsula (Fig. 1). The Azores islands have been settled by the Portuguese since the fifteenth century in the context of the beginning of the European maritime expansion. Located on the south part of Terceira, Angra do Heroísmo is a settlement with a bay which provides shelter from southerly winds (Fig. 1). After Vasco de Gama stopped at Angra to bury his brother on his return from the West Indies in 1499 (Velho and de Sá 1898), it became the main port of call for Portuguese and Spanish trading ships, to take on water and restock (Garcia 2017b). As a result of its strategic position, despite royal protectionism for Portuguese and Spanish ships, this harbour was also used by vessels from other kingdoms, mainly after the seventeenth century (de Meneses 1984). The “carpenter winds”, sudden violent storms, have resulted in many ships being wrecked in the Azores. More than 100 shipwrecks are claimed from the area of the bay of Angra alone (Garcia and Barreiros 2018).

Location map of Angra do Heroísmo on Terceira Island, in the Azores with the shipwrecks of Angra D and Angra C indicated (based on Iñañez et al. 2020)

The shipwreck of Angra D (Fig. 2), dating to around 1650, was found around 50 m off the coastline of Angra (Fig. 1). It was excavated by the Portuguese Ministry of Heritage and Culture in 1997 (Garcia and Monteiro 2001; Garcia 2004; Bettencourt 2017). Several structural parts of Angra D, which was 29 m long, survived, including nine floor riders, deck beams, the main mast step, etc. (Bettencourt 2017). From its construction, Angra D was identified as a two masted Spanish vessel, possibly a Patacho (brigantine), a type of warship which was used to patrol the Spanish Empire’s territories, but also used as a merchant vessel (Garcia and Monteiro 2001; Bettencourt 2017). A variety of artefacts and organic remains were also recovered during excavation (Garcia 2004; Bettencourt 2017; Iñañez et al. 2020). These include items which would have been used every day on board and range from pins and a thistle to wooden combs, wicker baskets and two staved buckets. One of the buckets, a pail, with evidence for the use of metal hoops around it, holding together eleven lateral pieces, was found in the area of the mast step, close to the keelson; it was optimally preserved, still attached to rope, and contained organic material (Fig. 3b, c). The bucket’s use is thought to have been as a baler to remove sea water from the deck (Smith 2009; Garcia 2004).

Around 8 m away from Angra D, during the same archaeological excavation in 1998 were recovered the remains of a Dutch shipwreck also dating to around 1650 CE, Angra C (Garcia et al. 1999; Phaneuf 2003) (Fig. 2). It was originally discovered in 1996, as Angra D, in relatively shallow waters, c. 7 m of depth. Only a segment of the ship’s hull around 14.7 m long was preserved under 2 m of sediment. The excavation of the shipwreck unearthed a relatively small amount of ballast under which various parts of the ship were recovered, the lower hull, part of the stern and the bow ends, etc. Angra C had a double hull, similar to other seventeenth century Dutch ships navigating the Asian trade route (to Mauritius, Batavia, etc.), and it was therefore identified as a Dutch vessel (Maarleveld 1998; Garcia and Monteiro 2001; Phaneuf 2003), possibly an Urca, a type of a cargo vessel built for coastal trade, commissioned to stay in the archipelago and serve routes between Europe and the islands of the Azores and Madeira. The artefacts preserved from the wreck, including various ceramics, a cauldron made of copper, pipe stems, leather soles, wheat grains, corn, straw, fruit pits, etc., provided information about life on the ship.

Methodology

From Angra D, organic preservation was noted from several areas. A small quantity of organic material was sampled from a complete bucket on the mast step (S39b) (Figs. 2, 3), In addition, insect remains from the base of the bucket, visible with the naked eye, were collected. From Angra C what was thought to be a layer of seeds from under decking planks (S139b) (Fig. 2) was sampled. The organic residues were sorted under a stereomicroscope. The insect material which was well preserved was identified to the lowest taxonomic level using modern comparative specimens and entomological keys. Lack of taxonomic knowledge and the fragmented nature of the material prohibited identifications to the lowest taxonomic level in some cases. Insect data from other late medieval shipwreck were collated and compared with the faunas from Angra D and Angra C in order to understand better the role of these seventeenth century vessels in the introduction of exotic insect species.

The insect assemblages

The assemblage from Angra D (S39b) and Angra C (S139b) show strong similarities. In essence, Angra C includes a sub-set of taxa (with 4 taxa and 8 individuals), in comparison with Angra-D (12 taxa and 155 individuals), and fewer specimens (See Table 1). The most abundant taxon from Angra D is tentatively referred to the ephydrid genus Paracoenia. These flies are found from a variety of foul aquatic contexts, including mineral or hot springs, alkaline lakes, and in areas with saline water (Mathis 1975). Paracoenia fumosa (Stenhammar) breeds in rich organic mud, often on midden edges. As other ephydrids, it has been associated with yeast (Maksimova et al. 2020) and has not previously been recorded in fossil synanthropic assemblages. However the puparia of the genus have not been adequately described, and the present identification to P. fumosa relies mainly on the presence of (inter alia) a very strong apicoventral spur on the mid-tibiae of the adult.

Another ephydrid from both shipwrecks is Scatella. The genus is associated with algae (Foote 1977) which would have been found in abundance within the environments of medieval vessels. In the case of Angra C, in addition to Scatella sp., there is evidence for Teichomyza fusca (Macquart), an ephydrid which is associated with urine, dung and faeces (Vogler 1900; Vibe-Petersen 1998) and hence it has earned the common name urine fly. Its larvae thrive on urine-soaked wood of ancient buildings (Foote 1995) and its pupae can block sewage pipes and drains (Smith 1989; Vibe-Petersen 1998). Adults have been collected during winter and in addition to its European records, it has been described from western South America. It is a palaearctic species, and its first record comes from 200 to 400 CE Roman York (Hall and Kenward 1990) and it was later recorded from Cutler’s Gardens in London c. 1650–1750 CE (Girling 1982), shipped from Europe to the Americas (Wirth 1968).

Piophila casei L. is a cosmopolitan species which oviposits on cheeses, dry meat, smoked fish and can also be found in carrion (Benecke 1998; Merritt et al. 2009). It is associated with forensic cases and can be an important forensic indicator as it colonises corpses during caseous fermentation (Martin-Vega 2011). Mégnin (1894) noted its association with caseic fermentation in corpses and he detailed observation of its larvae jumping from a corpse; this leaping behaviour and its association with some types of cheese, where the larvae breed, has led to its common name cheese skipper. It has been implicated in cases of urinary myiasis (Saleh and el Sibae 1993) and intestinal infections by P. casei are a direct result of a consumption of food infested by this fly for example salted fish, cured meat, etc. (Zumpt 1965). The earliest records of P. casei come from a Ptolemaic Egyptian mummy (Curry 1979; Panagiotakopulu et al. 2015; Panagiotakopulu unpublished), suggesting a north African origin.

Several species of Ophyra and Hydrotaea, formerly referred to the genus Ophyra, are strongly synanthropic and have been transported widely through human commerce. Originally from the Old World, Ophyra capensis (Wiedemann) and Hydrotaea ignava (Harris) are well-known cosmopolitan "filth-inhabiting" synanthropes with a probably ancient association with man. H. capensis has a fourteenth century record from Italy, from the mummy of the Blessed Antonio Patrizi (Morrow et al. 2015), and probably originated in the Mediterranean area, while H. ignava is possibly from further north in Europe. However, another Hydrotaea species, this time of American origin, which appears only recently to have crossed the Atlantic to become established in the Palaearctic, is H. aenescens (Wiedemann). The earliest record from Europe is from refuse dumps in Italy in 1964, spreading to Norway by 1982 (Skidmore 1985). In 2000 it was also taken from a refuse dump at El Senbellawein in Egypt (Skidmore and El-Serwy, pers. com.). All Hydrotaea species are predatory in the larval stage (Skidmore 1985) and in this sample (Angra D 39b), they were probably feeding on maggots of other flies (Musca domestica, and, possibly, those of ephydrids).

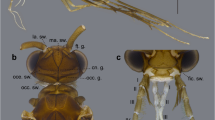

Dohrniphora cornuta (Bigot), a phorid and the most abundant taxon from the shipwrecks, probably originated from sub-tropical or tropical oriental areas (Disney and Bänziger 2009) and has been spread worldwide by commerce. The genus is otherwise restricted to warmer regions. D. cornuta is a filth inhabiting fly (Barnes 1990), recorded from rotting cargoes in ships, including rice bran, cow peas, etc., but is also known from sewage, compost, dead animals (snails, insects, vertebrates etc.). Its larvae are polyphagous but primarily sarcophagous and share the same habitat with adult females, feeding on decaying plants and dead and decaying animal matter (Disney 1983; Barnes 1990). One of the most interesting modern records comes from the cargo of a Burmese ship in Liverpool (Colyer unpublished notes in Disney et al. 2014). It has been noted for its synanthropic tendencies; adult females have been observed biting humans (Schmitz 1938, 1951), and it has also been observed living in human excrement (Skidmore 1978). Its larvae have been recorded causing myiasis in cattle (Patton 1922) but not from humans. D. cornuta has been recently recorded from forensic cases and there is a strong possibility that it will become an important forensic indicator in the near future (Disney et al. 2014).

The specific identity of the single incomplete Heleomyza puparium from Angra D cannot be ascertained, but three species, H. captiosa, H. serrata and H. borealis figure extremely prominently in archaeological contexts of Norse settlements in Britain, Iceland and West Greenland (Skidmore 1996; Panagiotakopulu et al. 2007) and it is most likely that they were widely dispersed by ships in the medieval period. Heleomyza spp. are troglodytic and have a strong preference for materials high in protein. They can be necrophagous, although they tend to breed in midden materials and in dung of omnivorous and carnivorous mammals (Skidmore 1996).

Spelobia spp. is a genus of lesser dung flies which tend to live in subterraneous habitats and are saprophagous, living on rotting substrates (Roháček 2011). Drosophila sp. is another taxon which frequents rotting fruit, decaying plant tissues and their fluxes (Carson 1971).

Amongst the species present on the Spanish ship (Angra D, S39b), this time of certain identity at the species level, is Musca domestica L., the common house-fly, which breeds in fermenting putrescent organic material and is most abundant in the company of man; it is eusynanthropic and is perhaps the most commonly recorded fly throughout the world. Through its effluvia and excreta it can spread mechanically a range of different pathogens, protozoa, bacteria, fungi and viruses. It can cause myiasis and one of the main diseases it is associated with is Chlamydia trachomatis, trachoma, which is endemic in Africa (Greenberg 1973; Brewer et al. 2021). The housefly has originated in the Old World, most probably in the Nile valley (Panagiotakopulu and Buckland 2017) from whence it has been distributed to Europe with early farmers and it later became cosmopolitan (Panagiotakopulu and Buckland 2018). Current research suggests that it was by far the most abundant fly breeding in human settlements in Egypt during Dynastic times, for instance at the Workmens’ village at Amarna during the construction of the tomb of Akhenaten in the fourteenth century BC (Panagiotakopulu et al. 2010). It was presumably taken to the Americas by commerce and this record aboard a seventeenth century ship in the mid-Atlantic is of interest in terms of its biogeography.

Apart from the dipterous material, the sample mainly consisted of fragments of various Coleoptera, including several larval urogomphi of Dermestes sp. and bits of adults of this genus. Its larvae have a capacity to feed on a variety of dried materials from dried meat to skin and bones (Peacock 1993). Also present was a head capsule of a parasitic Hymenopteran, probably belonging to the Diapriidae which are mainly parasitic on larvae of Diptera.

A piece of the tegmen of a cockroach was recovered from the sample, which probably belongs to Periplaneta americana (L.). This was in addition to several wings collected from the base of the bucket, during sampling (Fig. 4). P. americana is a nocturnal pest, sometimes called kakerlac, from the Danish word for cockroach, ship cockroach, Bombay canary (Guthrie and Tindall 1968) or waterbug in America, as a result of its proliferation in New York at the time of the arrival of a piped water supply in 1842 (Johnson 1928). It lives in a variety of different commodities and waste, from cheese, meat, mushrooms to detritus, hair, glue, cloth and dead insects (Bell and Adiyodi 1981). It thrives in humid environments and warm temperatures (Roth 1982) and is found in areas with suitable microclimate, (e.g. wood piles, hollow trees, etc. outdoors, or piped central heating systems, water pipes, sewers, etc., particularly indoors). This insect pest can mechanically spread a variety of different pathogens, and a range of food-borne pathogens such as Escherichia coli, Shigella dysenteriae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Salmonella enterica, have been associated with P. americana (Donkor 2020). Although it is called the American cockroach, its origins are thought to lie in tropical West and South Africa, where it is closely related to the African genus Pseudoderopeltis, and there is also an argument for an Indo Malaysian origin (Rehn 1945). The earliest records of its congeners P. japonica of Japanese origin and the synanthropic P. fuliginosa, of Asian origin, come from imprints on Jomon pottery, as early as 5300 years ago for the former and 4800–4000 years ago for the latter (Obata et al. 2022). P. americana appears for the first time from the shipwreck of the Spanish galleon San Esteban on Padre Island, Texas, in 1554 (Durden 1978), and there are additional records of the “American” cockroach from other shipwrecks from the sixteenth and the seventeenth century (see discussion below). It now has a cosmopolitan distribution and is perhaps the most common cockroach in houses in the United States (Cornwell 1976).

Discussion

Life on medieval carracks

Among the organic materials preserved from the Spanish vessel, botanical remains were recovered, including shells of coconuts, almonds, raisins and corn (de Matos 1998, p. 383) which provide information about life during the lengthy journey. In addition bones of cattle, pig and hog, chicken and also fish bones indicate that ships carried fowl, animals and diverse commodities for the food supply of the sailors on board (Phillips 1969; Earle 1998, p. 95; Miceli 1998). Although animals were banned on Iberian vessels in 1621, this ban was only on paper as there is mention of coops, hens and eggs reserved for the officers and the sick in accounts of Iberian ships sailing to the Indies (Phillips, ibid). Additional provisions would have been purchased during breaks in the journey for taking on freshwater and revictualling. Details about supplies and conditions on board are discussed in contemporary ship logs with mentions of boiled salt beef and salt fish as part of the daily food ratios and also suet, flour biscuits, soups, etc. (e.g. De Saussure 1995, p. 226, c. 1720; Gracias 1998). Provisions were similar for ships from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries on the same sailing routes (Pepys 1926; Bruijn 1967; Bruijn 1993; Macdonald 2006, 2010). Dutch ships had similar supplies to their Iberian counterparts, with butter, cheese, bread, biscuits, salted meat and fish, beer and wine, while living animals were kept on board to supplement the sailors’ diets and stops en route supplemented the sailors’ diets (Bruijn 1993; Söderlind 2006). Rotting supplies, unclean water, lack of cleaning of decks, cabins and clothing and unhygienic conditions, in particular when it comes to the ship’s bilge contributed to the proliferation of vermin, insects and rats, the last also recovered from Angra D (Bettencourt 2017).

Diptera recovered from the bucket, found next to the mast of Angra D, provide evidence for an alternative use for the bucket than the obvious interpretation for emptying water. They indicate the presence of high protein, decaying food materials and filthy conditions. The presence of dark loving flies, Heleomyza sp. and Spelobia spp., show that at least some of the taxa would have thrived in the gloomy conditions of the ship’s holds. Taking into account the species from this sample from Angra D, the synanthropes, such as D. cornuta, M. domestica, P. casei, and the fact that the majority of the assemblage are protein feeders, filth and dung inhabiting taxa, perhaps the bucket’s use, in addition to bailing water, was to throw garbage off the deck. An alternative explanation would be that the bucket, when not used as a bailer, but was a slop bucket (see Phillips 1969, p. 96; Navarro and Victoria 1997), used to empty urine, excrement and sick and/or collect waste and food leftovers for omnivorous animals on board.

The presence of P. periplaneta provides additional information for the contents of the bucket and confirms information from the literary record. Accounts from ship logs and journals mention cockroach infestations. De Salazar (1991) mentions “curianas” infestations during his travel across the Atlantic in 1573 (Pérez-Mallaína 1998, p. 133). It is not coincidental that in the “The Theatre of Insects” Moffett (1658, XVIII) refers to his compatriot, the English privateer Francis Drake. During the Anglo-Spanish war, in June of 1578, Drake near the island of San Miguel in the Azores, captured the Portuguese carrack São Filipe, on its return from the West Indies, stole its cargo of spices, gold and other commodities, and sank it: “In the Ship called the Philip, (which that noble other Neptune, Sir Francis Drake, took laden with spices) there was found a wonderful company of winged Moths, but somewhat bigger than ours, softer and of a more swarthy colour.”. In the seventeenth century, Domingo Navarrete noted that sailors on the Asiatic maritime route, thought that wind patterns could be predicted from the behaviour of the ship's cockroaches: 'the more restless they are, the higher the wind' (Cummins 1962, p. 356), a well-documented behavioural response of P. americana to wind puffs (e.g. Ritzmann 1984). Later in 1781, on the Princessa, Mourelle in his diary reported millions of cockroaches and he went on to state that they were devouring large quantities of biscuit leaving only dust (de la Perouse 1798).

The insect assemblage from Angra C comes from under the decking planks; this thin planking would have stopped cargo and ballast from falling between the frames (Steffy 1994), and also led to the preservation of the associated insect faunas. The flies on board of the Dutch ship, show strong similarities with the assemblage from the Spanish Angra D and indicate similar environments, with the ephydrid Scatella sp. showing wet environments and algae, the phorid D. cornuta and the piophilid P. casei pointing to filthy conditions, decaying plant and animal matter, dung and faeces. The faunas provide confirmation for the claim that on these vessels “most people did not take the trouble to go above to relieve themselves, which is partly to blame for so many deaths” (Monteiro and Castro 2015). However the presence of the urine fly from Angra C, shows that the deck may have been soaked with urine. Presumably foul materials from the deck of ships would have moved downward from floor to floor to end up in the bilge, which would be the equivalent of a floating cesspit.

Although lice were not recovered from either of the wrecks, ship logs and diaries repeatedly mention severe lice infestations to the extent that it was claimed that they could lead to death. Gaspar Ferreira in his logbook of the São Martinho (Monteiro 1985) also writes about “a boy [who had] died and was found dead under his blanket, riddled with lice”. Allegedly the death of Francis Forrest was due “to tis said eaten to death with lice (Teonge in Manwaring 1927 for HCA 15/48 5 August 1755 by the master and mate of the Deepsey brigantine).

Hitchhikers, carracks and trade

Up to the fifteenth century, the spice trade was dependent on intermediaries, through ports of the Red Sea, Syria and Egypt. The discovery of the Americas in 1492 led to the initiation of transatlantic West Indies route and the creation of the colony of Brazil during the sixteenth century (Bethell 1987) signaled a new era for exploration and subsequently trade. Vasco de Gama’s successful journey to Calicut and his ship’s return to Portugal with a cargo of Asian spices was a significant moment for the commence of the Iberian Asian maritime route. Urdaneta’s 1565 travel from the Philippines to Acapulco showed that transpacific trade was possible, establishing the so called Manila galleon route. A decade later Francis Drake’s circumnavigation (1577–80), from the straits of Magellan, along the west coast of America, west across the Pacific to the Spice islands in the southeast Indonesia and back via the Cape of Good Hope and West Africa, expanded commercial activities. After the sixteenth century, the Dutch broke the Iberian monopolies and with the use of innovations in ship construction and business, succeeded in extending the market of exotic goods, with the English navy also claiming part of the trade (Steensgaard 1990; Pedreira 1998).

In a biogeographic context the insect assemblages from the two shipwrecks from Angra bay, provide information related to the journeys of these ships. Species were transported on ballast, parts of the faunas were surviving in the bilge of the ship and other taxa were infesting cargo and food supplies. The vessels would not have been cleaned out at the end of each journey and this resulted to a residual fauna. Similar faunas would be expected in the same itineraries and the probability is that supply and trading hubs, like Angra, on the return routes from the East Indies or the West Indies, played a role for the eventual homogenization of the faunas of these ships.

Musca domestica, which was recovered from Angra D, was initially introduced to Europe with the introduction of domestic herbivores, as houseflies thrive on herbivore dung (Skidmore 1996; Panagiotakopulu and Buckland 2018). The spread of agriculture led to the establishment of houseflies as early as the Neolithic with records from Erkelenz-Kückhoven in the Rhine Valley c. 5300 BC (Schmidt 2010), from Schipluiden in the Netherlands at ca. 3500 BC (Hakbijl 2006) from Thyangen Weier in Switzerland ca. 3500–3000 BC (Nielsen et al. 2000), Federsee in southern Germany, ca. 3000 BC (Schmidt 2004) and the pile dwelling at Alvastra in southern Sweden ca. 3000 BC, (Skidmore in Lemdahl et al. 1995). However, when it comes to maritime pathways, it is only during the thirteenth century CE that the first record of houseflies comes from a shipwreck, that from Oskarshamn in Småland, Sweden (Lemdahl 1991; Lemdahl et al. 1995). After this, there is some evidence that houseflies were on board of larger ships, as it was found on the Mary Rose which was wrecked off Portsmouth on 1545 (Robinson 2005) (Fig. 5).

Location map with records of Periplaneta americana (L.) and Musca domestica L. from shipwrecks. P. americana was recovered from: San Esteban on Padre Island in 1554 (Durden 1978), Emanuel Point I and Emanuel Pont II in 1559 near Pensacola in Florida (Smith 2018). The 1564 wreck of Santa Clara (St John’s shipwreck site) on the western edge of the Little Bahama (Corey 2017), the wreck of San Antonio c. 1621 on the western reefs of Bermuda (Roth 1982), Angra D, Angra do Heroísmo, Terceira Island, 1650 CE (current paper), La Belle, sunk in in 1686 at Matagorda Bay (Bruseth and Turner 2005), Burgzand Noorg 4 in Waddenzee, in the Netherlands (Kuijper and Manders 2009). M. domestica was found at: Oskarshamn in Småland, Sweden 13th C (Lemdahl 1991), and in the Mary Rose wrecked off Portsmouth in 1545 (Robinson 2005), Angra D (current paper)

Heleomyza sp., another taxon recovered from Angra D, is a genus widely distributed in northern Europe, with H. borealis associated with the Viking farms, to the extent that it was christened by Skidmore (1996) the Viking house fly. The find from the Iberian vessel shows that heleomyzids were perhaps frequent accidental travellers in cargo and ballast. This probably resulted from the exchange system with the Low Countries and England and also the Baltic Sea; fur, wax and also wood from Scandinavian forests (Yun-Casalilla 2019; Jiménez-Montes 2022) through specialised merchants were among the commodities traded. The triangular Spanish, English and North American trade of cod and wool during this period (Lindroth 1957; Grafe 2003) could provide an additional explanation and it is no surprise that heleomyzids would find breeding areas in the dark corners of these vessels.

The most interesting species in terms of its biogeography is D. cornuta, with first records from Angra D and Angra C. Its presence on both these carracks is probably linked with Asian trade itineraries and perhaps similar cargoes for both these ships. These finds indicate that D. cornuta was probably transported onboard ships in the seventeenth century spice route east Asia together with traded commodities, then introduced to European ports on this route, and through transatlantic and transpacific trade it became cosmopolitan.

The American cockroach, P. americana, recovered from Angra D, is the taxon with the most records from the limited insect work from shipwrecks. Its earliest record, from the Spanish carrack San Esteban in 1554 was recovered together with B. orientalis (Durden 1978). The oriental cockroach is also considered to have an African origin. Its earliest archaeological occurence is an ootheca recovered from bandages from a Manchester Museum Ptolemaic period mummy (1767) c. 305-30 BC, while an additional record of an oriental cockroach wing from late Roman (4th century CE) Lincoln (Carrott et al. 1995) indicates a probable introduction from Africa. Literary records mention Roman commercial expeditions from c. 19 BC-90 CE, to areas of sub-Saharan Africa which are thought to have reached lake Chad and the Niger (Raven 1993), and also possibly maritime commerce with the Canary Islands (Roller 2006). Although there is there is lack of confirmation about these expeditions from the archaeological record, there is evidence for trade with Nubia (e.g. Kirwan 1957, 1980; Simpson et al. 2020) which includes African pests (Panagiotakopulu unpublished).

On the other hand, the introduction of P. americana via maritime routes as late as the sixteenth century could point towards an Indo-Malaysian origin (Rehn 1945) and its spread via the spice route from southeast Asia as opposed to an out of Africa hypothesis. Additional records during the sixteenth century (Fig. 5) include evidence from the wrecks near Pensacola in Florida, Emanuel Point I and Emanuel Pont II in 1559 (Smith 2018) and from the 1564 wreck of Santa Clara (St John’s shipwreck site) on the western edge of the Little Bahama (Corey 2017). During the seventeenth century P. americana was found in the wrecks of the Spanish ship San Antonio, sunk around 1621 on the western reefs of Bermuda (Roth 1982) and the French ship La Belle, the supply ship of the Texas colony established by La Salle, sunk in 1686 at Matagorda Bay (Bruseth and Turner 2005) (Fig. 5). These records, were probably linked to the Spanish treasure ship route, which brought bullion to Iberian ports from Havana. Whilst another maritime route during the same period, the Asian route via the Cape of Good Hope, was probably the pathway for its initial introduction and spread to trading stops on the way and highlights the importance of Angra as a port of call for this and other introductions (Fig. 6). From the eighteenth century, numerous oothecae of American cockroaches have been recovered from the shipwreck Burgzand Noorg 4 in Waddenzee, in the Netherlands (Kuijper and Manders 2009).

It is interesting that from the taxa recovered from Angra D and Angra C, the key species, M. domestica, D. cornuta, P. americana and P. casei are part of the modern fauna of the Azores (Borges et al. 2022), pointing to continuous introductions through shipments of infested commodities, and providing more data on the importance of trade (Capinha et al. 2023) for the establishment of introduced species on islands. H. ignava is also part of the modern fauna. It is possible that the individual recovered from Angra D could be H. ignava as opposed to O. capensis, perhaps transported to the Azores via trade with northern Europe. The taxa from the Angra wrecks primarily associated with conditions on board, P. fumosa, T. fusca and Diapriidae may be present in Azores but have not been recorded yet (Borges et al. ibid).

Looking at the broader context of these introductions and taking into account other species recovered, for example, the numerous rats from Angra D (Bettencourt 2017), which although unidentified are almost certainly black rat, Rattus rattus (L.), these taxa provided ample opportunities for the spread of infestation and infectious disease on board. They also provide some clues for the role of ships during the sixteenth century as reservoirs of pests, and as vectors of pathogens. From houseflies and cheese skippers to scuttle flies and cockroaches, large trading vessels and key ports guaranteed a continuous pest and vector traffic. Maritime trade routes and transatlantic and transpacific trade played an important role in the spread of a range of invasive species, some of which were responsible for vector borne diseases.

Conclusions

The fly faunas of two seventeenth century carracks, the Spanish Angra D and the Dutch Angra C were primarily shaped by trade. They include the first record of the oriental now cosmopolitan synanthropic fly Dohrniphora cornuta, probably introduced from southeast Asia.

The so-called American cockroach, Periplaneta americana, was also probably introduced via the Asian maritime route from southeast Asia. These data, in particular the presence of cockroaches, and the first record of the cheese skipper Piophila casei from a shipwreck, the finds of the housefly, Musca domestica, and the urine fly, Teichomyza fusca paint a grim picture for the conditions on board of these vessels, which is supported by the slim literary record. The presence of the American cockroach on sixteenth and seventeenth century vessels and its spread is probably associated with large scale transatlantic and transpacific trade. Based on the insect faunas, the role of the Azores port Angra do Heroísmo, as an intermediate station for return journeys from India, West Africa, Central America and Europe made it a hub for the dispersal of introduced insects from these continents to Europe and vice versa. Refueling ports like Angra during the Age of Discovery were probably the equivalent of hot spots for continuous introductions of invasive species. Their study will provide novel data for biological invasions, geographic expansion of introduced species and their establishment in new areas and a novel perspective of the process towards globalization.

References

Banks J (1797) The journal of the Hon. Sir Joseph Banks during Cook’s voyage with the Endeavour. Edited by Hooker JD (I896). London

Barnes JK (1990) Life History of Dohrniphora cornuta (Bigot) (Diptera: Phoridae), a Filth-Inhabiting Humpbacked Fly. J N Y Entomol 98:474–483

Bell WJ, Adiyodi KJ (1981) The American cockroach. Chapman and Hall, London

Benecke M (1998) Six forensic entomology cases: Description and commentary. JFS 43:797–780

Bethell L (1987) Colonial Brazil. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bettencourt JA (2017) Os naufrágios da baía de Angra (ilha Terceira, Açores): uma aproximação arqueológica aos navios ibéricos e ao porto de Angra nos séculos XVI e XVII. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Lisbon

Borges PAV, Lamelas-Lopez L, Andrade R et al (2022) An updated checklist of Azorean arthropods (Arthropoda). Biodivers Data J 10:e97682. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.10.e97682

Brewer N, McKenzie MS, Melkonian N, Zaky M, Vik R, Stoffolano JG, Webley WC (2021) Persistence and significance of Chlamydia trachomatis in the Housefly, Musca domestica L. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 21:11. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2021.0021

Bruijn IR (1967) Voeding op de Staatse vloot. Spieg Hist 2:175–183

Bruijn JR (1993) The Dutch navy of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, studies in maritime history. Univ. S. C Press, Columbia

Bruseth JE, Turner TS (2005) From a watery grave: the discovery and excavation of La Salle’s shipwreck, La Belle. Texas A&M University Press, College Station

Capinha C, Essl F, Porto M, Seebens H (2023) The worldwide networks of spread of recorded alien species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 120(1):e2201911120

Carlton JT (1999) The scale and ecological consequences of biological invasions in the world’s oceans. In: Sandlund OT, Schei PJ, Viken A (eds) Invasive species and biodiversity management. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, p 431

Carrott J, Issitt M, Kenward H, Large F, McKenna B, Skidmore P (1995) Insect and other invertebrate remains from excavations at four sites in Lincoln (site codes WN87, WNW88, WF89 and WO89). Reports from the Environmental Archaeology Unit, York, 95/10

Carson HL (1971) The ecology of Drosophila breeding sites. Harold L. Lyon Arboretum lecture, vol 2. Univ. Hawaii, Honolulu, pp 1–28

Corey M (2017) Solving a Sunken Mystery: the investigation and identification of a sixteenth-century shipwreck. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield

Cornwell PB (1976) The cockroach, vol. 2, insecticides and cockroach control. Associated Business Programmes LTD, London

Cummins JS (1962) (ed. and trans.) The travels and controversies of friar domingo navarrete, 1618–1886, 2 vols. Hakluyt Society, London

Curry A (1979) The insects associated with the Manchester mummies. In: David AR (ed) The Manchester Museum Mummy Project. Manchester University Press, Manchester, pp 113–118

de la Perouse JFDG (1798) A voyage round the world in the years 1785, 1786, 1787, and 1788. J. Johnson, London

de Matos AT (1998) "Quem vai ao mar, em terra se avia": preparativos e recomendações aos passageiros da carreira da Índia no século XVII. In: A carreira da Índia e as rotas dos estreito. Actas do VIII seminário internacional de história indo-portuguesa. Angra do Heroísmo: Centro de Estudos dos Povos e Culturas de Expressão Portuguesa da Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Centro de História de Além-Mar da Universidade Nova de Lisboa e Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical, pp 377–394

de Meneses AF (1984) Angra na rota da Índia: funções, cobiças e tempo. In Os Açores e o Atlântico (séculos XIV-XVII), Actas do Colóquio Internacional realizado em Angra do Heroísmo de 8 a 13 de Agosto de 1983. Angra do Heroísmo: Instituto Histórico da Ilha Terceira, pp 721–727

De Salazar E (1991) Seafaring in the Sixteenth Century: The Letter of Eugenio de Salazar, 1573 (trans: Frye J). Mellen Research University Press, San Francisco

De Saussure C (1995) A foreign view of England in 1725–1729. The letters of Monsieur César De Saussure to his family (trans: and ed. Van Muyden M). Caliban Books

Disney RHL (1983) Scuttle flies Diptera, Phoridae (except Megaselia). RES Handboook Identification of British Insects, vol 10, no 6, pp 1–81

Disney RHL, Bänziger H (2009) Further records of scuttle flies (Diptera: Phoridae) imprisoned by Aristolochia baenzigeri (Aristolochiaceae) in Thailand. Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen Entomologischen Gesellschaft 82:233–251

Disney RHL, Garcia-Rojo A, Lindström A, Manlove JD (2014) Further occurrences of Dohrniphora cornuta (Bigot) (Diptera, Phoridae) in forensic cases indicate likely importance of this species in future cases. Forensic Sci Int 241:e20–e22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.05.010

Donkor ES (2020) Cockroaches and food-borne pathogens. Environ Health Insights 14:1178630220913365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178630220913365

Durden J (1978) Appendix H. Fossil cockroaches from a 1554 Spanish shipwreck. In: Barto Arnold J, Weddle R (eds) The nautical archaeology of Padre Island, the Spanish shipwrecks of 1554: Texas Antiquities Committee Publ. 7. Academic Press, New York, pp 407–416

Earle P (1998) Sailors English merchant seamen 1650–1775. Methuen Publishing Ltd, London

Foote BA (1977) Utilization of blue-green algae by larvae of shore flies. Environ Entomol 6:812–814

Foote BA (1995) Biology of shore flies. Environ Sci 40:417–442

Garcia AC (2004) Preliminary assessment of the daily life on board of an Iberian ship from the beginning of the 17th century (Terceira, Azores). In: Pasquinucci M, Weski T (eds) Close encounters: sea- and riverborne trade, ports and hinterlands, ship construction and navigation in antiquity, the middle ages and in modern time, vol 1283. BAR-IS, Oxford, pp 163–169

Garcia ACB (2017a) New ports of the New World: Angra, Funchal, Port Royal and Bridgetown. IJMH 29(1):155–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0843871416677952

Garcia AC (2017b) Angra, an atlantic seaport in the seventeenth century. In: Polónia A, Antunes C (eds) Seaports in first global age. Portuguese agents networks and interactions. University of Porto Press, Porto, pp 1500–1800

Garcia C, Monteiro P (2001) The excavation and dismantling of Angra D, a probable seagoing ship, Angra bay, Terceira Island, Azores, Portugal. Preliminary assessment. In: Alves F (ed) Proceedings: international symposium on archaeology of medieval and modern ships of Iberian-Atlantic Tradition. Lisbon, Portugal, pp 431–447

Garcia AC, Barreiros JP (2018) Are underwater archaeological parks good for fishes? Symbiotic relation between cultural heritage preservation and marine conservation in the Azores. Reg Stud Mar Sci 21:57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsma.2017.10.003

Garcia C, Monteiro PA, Phaneuf E (1999) Os destroços dos navios Angra C e D descobertos durante a intervenção arqueológica subaquática realizada no quadro do projecto de construção de uma marina na baía de Angra do Heroísmo. Rev Port Arqueolog 2(2):211–232

Girling MA (1982) The arthropod assemblage from Cutler's Gardens. Ancient Monuments Laboratory Report No. 3670, pp 1–16

Gracias MFS (1998) Entre partir e chegar: saúde, higiene e alimentação a bordo da Carreira da India no séc. XVIII. A Carreira da Índia e as Rotas dos Estreitos. In: Actas do VIII Seminário Internacional de História Indo-Portuguesa, Artur Teodoro de Matos e Luís Filipe Reis Thomaz (coords), CEPCEP/Centro de História de Além-Mar/Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical, Angra do Heroísmo, pp 457–468

Grafe R (2003) The globalisation of codfish and wool: Spanish-English-North American triangular trade in the early modern period. London School of Economics, Dept. of Economic History, London

Greenberg B (1973) Flies and disease: II. Biology and disease transmission. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Guthrie DM, Tindall AR (1968) The biology of the cockroach. Edward Arnold, London

Hakbijl T (2006) Insects. In: Louwe Kooijmans LP, Jongste PFB (eds) Schipluiden, a Neolithic settlement on the Dutch North Sea coast c. 3500 CAL BC, vol 37/38. APL, pp 471-482

Hall AR, Kenward HK (1990) Environmental evidence from the Colonia. Archaeology of York, The environment, 14/6. Council for British Archaeology for York Archaeological Trust, London

Iñañez JG, Bettencourt J, Pinto I, Teixeira A, Arana G, Castro K, Sanchez-Garmendia U (2020) Hit and sunk: provenance and alterations of ceramics from 17th century Angra D shipwreck. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 12:182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-020-01109-y

Jiménez-Montes G (2022) Trade and traders of North European timber and other naval provisions in sixteenth-century Seville. In: Crespo Solana A, Castro F, Nayling N (eds) Maritime history and archaeology of the Global Iberian World (15th–18th centuries), vol 1. Springer, Berlin, pp 199–214

Johnson CW (1928) Some common insects of the household. Sci Mon 27:343–346

Kirwan LP (1957) Rome beyond the southern Egyptian frontier. Geogr J 123:13–19

Kirwan L (1980) The emergence of the United Kingdom of Nubia. SNR 61:134–139

Kuijper WJ, Manders M (2009) Coffee, cacao and sugar cane in a shipwreck at the bottom of the Waddenzee, the Netherlands. APL 41:73–86

Lemdahl G (1991) Insekter från Oskarshamkoggen - pilotundersökning av sedimentprover från vraket. Uppsat i Påbyggnadskurs i arkeologi vid Stockholms Universitet, pp 45–47

Lemdahl G, Aronsson M, Hedenäs L (1995) Insekter från ett medeltida handelsfartyg. Ent Tidskr 116:169–174

Lindroth CH (1957) The faunal connections between Europe and North America. Wiley, New York

Maarleveld TJ (1998) Archaeological heritage management in Dutch Waters: exploratory studies. Lelystad/Leiden

Macdonald J (2006) Feeding Nelson’s Navy: the true story of food at sea in the Georgian era. Chatham, London

Macdonald J (2010) The British Navy’s Victualling Board: management competence and incompetence. Boydell & Brewer, Woodbridge

Maksimova IA, Kachalkin AV, Yakovleva EY et al (2020) Yeast communities associated with Diptera of the white sea littoral. Microbiology 89:212–218. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0026261720020071

Manwaring, GE (1927) The Diary of Henry Teonge. Harper & Brothers; New York and London

Martin-Vega D (2011) Skipping clues: forensic importance of the family Piophilidae (Diptera). Forensic Sci Int 212:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.06.016

Mathis WN (1975) A systematic study of Coenia and Paracoenia (Diptera: Ephydridae). Great Basin Nat 35:65–85

Mégnin P (1894) La faune des cadavres, Application de l’entomologie a la médecine légale. In: Léauté M (ed) Encyclopédie Scientifique des Aide-Mémoire. Masson-Gauthier-Villars et Fils, Paris

Merritt RW, Courtney GW, Keiper JB (2009) Diptera (Flies, Mosquitoes, Midges, Gnats). In: Resh VH, Cardé RT (eds) Encyclopedia of insects, 2nd edn. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 284–297

Miceli P (1998) Navio: a historia e o lugar da historia (viver a bordo nas naus portuguesas da carreira da índia - seculo XVI). A Carreira da Índia e as Rotas dos Estreitos. In: Actas do VIII Seminário Internacional de História Indo-Portuguesa, Artur Teodoro de Matos e Luís Filipe Reis Thomaz (coords), CEPCEP/Centro de História de Além-Mar/Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical, Angra do Heroísmo, pp 395–414

Moffett T (1658) The theater of insects: or, lesser living creatures. E. C., London, UK. 1967. Volume 3 of Topsell and Moffett. The history of four-footed beasts and serpents and insects. De Capo Press, New York

Monteiro JRV (1985) Uma viagem redonda da Carreira da Índia (1597–1598). Biblioteca Geral da Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra

Monteiro A, Castro F (2015) Our ships at the bottom of the Ocean (Os nossos navios no fundo do oceano). In: Barros A (ed) Os Descobrimentos e as Origens da Convergência Global. Casa do Infante/Câmara Municipal do Porto, Porto, pp 275–304

Morrow JJ, Baldwin DA, Higley L, Piombino Mascali D, Reinhard KJ (2015) Curatorial implications of Ophyra capensis (Order Diptera, Family Muscidae) puparia recovered from the body of the Blessed Antonio Patrizi, Monticiano, Italy (Middle Ages). J Forensic Leg Med 36:81–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2015.09.005

Navarro JJ, de la Victoria M (1997) Diccionario demostrativo con la configuración y anatomía de toda la arquitectura naval moderna (Cádiz, 1719–1756). MNM, Ms.2653. Ed.Facsimil. Lunwerg, Madrid

Nielsen BO, Mahler V, Rasmussen P (2000) An arthropod assemblage and the ecological conditions in a byre at the Neolithic settlement of Weier Switzerland. J Archaeol Sci 27:209–218. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1999.0448

Obata H, Sano T, Nishizomo K (2022) The Jomon people cohabitated with cockroaches—the prehistoric pottery impressions reveal the existence of sanitary pests. J Archaeol Sci Rep 45:103599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2022.103599

Panagiotakopulu E, Skidmore P, Buckland PC (2007) Fossil insect evidence for the end of the Western Settlement in Greenland Sci Nat 94:300–306

Panagiotakopulu, E, Higham T, Buckland P, Tripp J, Hedges R (2015) AMS radiocarbon dating of insect chitin - A discussion of new dates, problems and potential. Quat Geochron 27:22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2014.12.001

Panagiotakopulu E, Buckland P (2017) A thousand bites—insect introductions and late Holocene environments. Quat Sci Rev 156:23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.11.014

Panagiotakopulu E, Buckland P (2018) Early invaders: farmers, the granary weevil and other uninvited guests in the Neolithic. Biol Invasions 20:219–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-017-1528-8

Panagiotakopulu E, Buckland PC, Kemp B (2010) Underneath Ra-Nefer’s house floors: archaeoentomological investigations of an elite household in the Main City at Amarna, Egypt. J Archaeol Sci 37:474–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2009.09.048

Patton WS (1922) Notes on some Indian Aphiochaetae. Indian J Med Res 9:683–691

Peacock ER (1993) Adults and larvae of hide, larder and carpet beetles and their relatives (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) and of Derodontid Beetles (Coleoptera: Derodontidae). In: Handbooks for the identification of British Insects. RES, London

Pedreira JM (1998) To have and to have not. The economic consequences of empire. Rev Hist Econ 1:93–122

Pepys S (1926) Samuel Pepys’s naval minutes. In: Tanner JR (ed) The Naval Records Society, London

Pérez-Mallaína PE (1998) Spain’s men of the sea: daily life on the indies fleets in the sixteenth century. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Phaneuf E (2003) Angra C, une épave Hollandaise en contexte Açoréen du XVIIe siècle. Unpublished thesis, University of Montréal

Phillips CR (1969) Six galleons for the King of Spain: Imperial defense in the early seventeenth century. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Raven S (1993) Rome in Africa, 3rd edn. Routledge, New York

Rehn JAG (1945) Man’s uninvited fellow traveler-the cockroach. Sci Mon 61(4):265–276

Ritzmann RE (1984) The cockroach escape response. In: Eaton RC (ed) Neural mechanisms of startle behavior. Plenum Press, New York, pp 93–131

Robinson MA (with Allen MJ) (2005) Insects. In: Gardiner J, Allen MJ (eds) Before the mast. Life and death aboard the Mary Rose. The archaeology of the Mary Rose, vol 4. Mary Rose Trust, Portsmouth, pp 615–617

Roháček J (2011) The fauna of Sphaeroceridae (Diptera) in the Gemer area (Central Slovakia). Čas Slez Muz Opava (A) 60:25–40

Roller DW (2006) Through the pillars of Herakles: Greco-Roman exploration of the Atlantic. Routledge, New York

Roth LM (1982) Introduction. In: Bell WJ (ed) The American cockroach. Chapman & Hall, London, pp 1–14

Saleh MS, el Sibae MM (1993) Urino-genital myiasis due to Piophila casei. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 23:737–739

Schmitz H (1938) 33. Phoridae (Lieferung 123). In: Lindner E (ed) Die Fliegen der Palaearktischen Region. Band IV. Schweizerbarfsche Verlagsbuchhandlung (Erwin Nagele), Stuttgart, pp 1–64

Schmitz H (1951) 33. Phoridae (Lieferung 165). In: Lindner E (ed) Die Fliegen der Palaearktischen Region, vol IV. Schweizerbarfsche Verlagsbuchhandlung (Erwin Nagele), Stuttgart, pp 241–272

Schmidt E (2004) Untersuchungen von Wirbellosenresten aus jung und endneolithischen Moorsiedlungen des Federsees. In: Schlichtherle H (ed) Ökonomischer und Ökologischer Wandel am Vorgeschichtlichen Federsee. Hemmenhofener Skripte 5, Janus, Freiburg, Landesdenkmalamt Baden-Württemberg, Archäologische Denkmalpflege, Referat 27, pp 160–86

Schmidt E (2010) Insektreste aus bandkeramischen Brunnen. Tote Käfer lassen eine bandkeramische Brunnenumgebung entstehen. In: Conference Abstract Mitteleuropa im 5. Jahrtausend vor Christus. Westfälische Wilhems-Universität, Münster, pp 32–33

Seebens H, Essl F, Dawson W, Fuentes N, Moser D, Pergl J, Pysek P, Van Kleunen M, Weber E, Winter M, Blasius B (2015) Global trade will accelerate plant invasions in emerging economies under climate change. Glob Change Biol 21:4128–4140

Seebens H, Blackburn TM, Dyer EE et al (2018) Global rise in emerging alien species results from accessibility of new source pools. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:E2264–E2273

Simpson A, Fernández-Domínguez E, Panagiotakopulu E, Clapham A (2020) Ancient DNA preservation, genetic diversity and biogeography: a study of house flies from Roman Qasr Ibrim, Lower Nubia, Egypt. J Archaeol Sci 120:105180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2020.105180

Skidmore P (1978) Some micro-habitats. Dung. In: Stubbs Α, Chandler P (eds) A Dipterist’s Handbook. Amateur Entomol 15:73–79

Skidmore P (1985) The biology of the Muscidae of the world. Series entomologica, vol 29. Junk, Dordrecht, pp 1–550

Skidmore P (1996) A dipterological perspective on the Holocene history of the North Atlantic Area. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Sheffield

Smith KGV (1989) An introduction to the immature stages of British flies. In: Dolling WR, Askew RR (eds) Handbooks for the identification of British Insects 10, Part 14. Dorset Press, Dorset

Smith KM (2009) Comparative analysis of cask material from late sixteenth through early nineteenth century shipwrecks. Unpublished Master thesis. East Carolina University

Smith RC (ed) (2018) Florida's Lost Galleon: The Emanuel Point Shipwreck. University Press of Florida, Gainesville

Steensgaard N (1990) Commodities, bullion and services in intercontinental transactions before 1750. Ιn: Pohl H (ed) The European discovery of the world and its economic effects on pre-industrial society. Papers of the tenth international economic history congress. Koch, Neff & Oetinger & Co, Stuttgart, pp 9-24

Steffy JR (1994) Wooden ship building and the interpretation of shipwrecks. College Station, Texas

Söderlind U (2006) Skrovmål: kosthållning och matlagning i den svenska flottan från 1500-tal till 1700-tal. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Stockholm

Velho Á, de Sá J (1898) A journal of the first voyage of Vasco da Gama, 1497–1499. Hakluyt Society, London

Vibe-Petersen S (1998) Development, survival and fecundity of the urine fly, Scatella (Teichomyza) fusca and predation by the blackdump fly, Hydrotaea aenescens. Entomol Exp Appl. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1570-7458.1998.00317.x

Vogler CH (1900) Beiträge zur Metamorphose derTeichomyzafusca. Illustrierte Zeitschrift für Entomologie 5:1–35

Wirth WW (1968) Family ephydridae. In: A catalogue of the Diptera of the United States, vol 77. Departamento da Zoologia, Secretaria de Agricultura, Sao Paulo, pp 1–43

Yun-Casalilla B (2019) Iberian world empires and the globalization of Europe 1415–1668. In: Palgrave studies in comparative global history. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Zumpt F (1965) Myiasis in man and animals in the Old World. Butterworths, London

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to the late Peter Skidmore whose work formed the core of the paper and inspired insect biogeographic research in the North Atlantic. The authors would like to thank Paul Buckland for his comments and discussions. Professor Jim Carlton and Professor Paulo Borges are also thanked for their useful comments which improved the manuscript. Thanks are due to the Regional Department of Culture Heritage of the Azores (DRaC) for the material availability, and the National Centre for Nautical and Underwater Archaeology (CNANS-Portugal), responsible for the archaeological intervention in 1998. Although this research has no funding to declare, Catarina Garcia was supported by ERC Synergy Grant 4- Oceans: Human History of Marine Life (Grant Agreement no. 951649) and CHAM Centro de Humanidades da Universidade NOVA de Lisboa.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EP devised the study concept and design with contributions from ACG. Data analysis was performed by EP based on material passed on to her by the late Peter Skidmore. The first draft of the manuscript was written by EP with contributions from ACG. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Panagiotakopulu, E., Garcia, A.C. Two Azores shipwrecks and insect biological invasions during the Age of Discovery. Biol Invasions 25, 2309–2324 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-023-03042-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-023-03042-2