Abstract

“One hundred worst” lists of alien species of the greatest concern proved useful for raising awareness of the risks and impacts of biological invasions amongst the general public, politicians and stakeholders. All lists so far have been based on expert opinion and primarily aimed at representativeness of the taxonomic and habitat diversity rather than at quantifying the harm the alien species cause. We used the generic impact scoring system (GISS) to rank 486 alien species established in Europe from a wide range of taxonomic groups to identify those with the highest environmental and socioeconomic impact. GISS assigns 12 categories of impact, each quantified on a scale from 0 (no impact detectable) to 5 (the highest impact possible). We ranked species by their total sum of scores and by the number of the highest impact scores. We also compared the listing based on GISS with other expert-based lists of the “worst” invaders. We propose a list of 149 alien species, comprising 54 plants, 49 invertebrates, 40 vertebrates and 6 fungi. Among the highest ranking species are one bird (Branta canadensis), four mammals (Rattus norvegicus, Ondatra zibethicus, Cervus nippon, Muntiacus reevesi), one crayfish (Procambarus clarkii), one mite (Varroa destructor), and four plants (Acacia dealbata, Lantana camara, Pueraria lobata, Eichhornia crassipes). In contrast to other existing expert-based “worst” lists, the GISS-based list given here highlights some alien species with high impacts that are not represented on any other list. The GISS provides an objective and transparent method to aid prioritization of alien species for management according to their impacts, applicable across taxa and habitats. Our ranking can also be used for justifying inclusion on lists such as the alien species of Union concern of the European Commission, and to fulfill Aichi target 9.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Human global activities enable an increasing number of species to reach regions outside of their native range, establish self-sustaining populations and spread into natural habitats, a phenomenon known as biological invasion (Elton 1958). Some alien species exert considerable impact on the environment and socio-economy in their new range, leading to large efforts to mitigate these negative effects (Vilà et al. 2008, 2010).

Environmental impacts include not only changes to biodiversity such as a decrease in native species, but also alterations in nutrient or water pools and fluxes leading to changes of whole ecosystem properties (Pyšek et al. 2012; Blackburn et al. 2014; Cameron et al. 2016). The impacts of some alien species go beyond changes to the environment, as they negatively affect production in agriculture, forestry, aquaculture or fisheries. Moreover, they can be of concern for human well-being, for example if they transmit diseases or damage infrastructure (Vilà and Hulme 2017). Therefore, for management to be most effective we need to consider impacts across sectors and taxa. Furthermore, not all alien species cause large impacts, and even among those that do, managers need to prioritize species because there are too many to manage them all (DAISIE 2008).

Lists of the most harmful alien species have been developed to raise awareness amongst the general public, politicians and stakeholders. The most popular amongst these lists are “100 of the world’s worst invasive alien species”, a global list compiled by the IUCN Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG 2017) (hereafter called ISSG-100) and “100 of the most invasive alien species in Europe”, composed by the EU DAISIE consortium (DAISIE 2008; Vilà et al. 2008; hereafter called DAISIE-100). These lists are based on expert opinion and cover a variety of taxonomic groups and environments. They were also compiled so as to be representative of a broad range of origins, pathways of introduction, and diversity of impacts. A different type of list also features the worst invaders, but its function is regulatory as it is directly used for management—a so-called “black list” (EU 2016, 2017).

The general value of 100-worst lists is considerable as they provide the argument why certain alien species need management interventions, and showcase a wide variety of potential impacts. The problem of such lists, as well as black lists, is the non-quantitative (and therefore potentially biased) basis for inclusion of species, which makes the applied criteria unclear and relying on expert opinions and preferences (Kumschick et al. 2016). This is largely due to the lack of a generic and reproducible method to compare impacts among taxa, and across regions and habitats. This deficiency might hinder the applicability and usefulness of expert-based lists for science, and in the case of black lists also for management and policy. For prioritization of costly and time-intensive management of harmful alien species, objective and transparent methods of species selection are needed.

Fortunately, in the last decade much progress has been made in this regard and various quantitative and semi-quantitative impact scoring tools have been developed that can be applied across habitats and taxa (e.g. Blackburn et al. 2014; Nentwig et al. 2016; Bacher et al. 2017). Specifically, Nentwig et al. (2016) propose a tool that quantifies both environmental and socioeconomic impacts.

The aim of this study is to produce an as complete as possible list, based on current knowledge, of the worst alien species in Europe using a scoring system applied to animal, plant and fungal taxa, considering all habitats and including environmental and socioeconomic impacts. We present, for the first time, an objective, semi-quantitative, transparent and ranked list to raise awareness of the worst alien species in Europe and facilitate management and policy of biological invasions on this continent.

Materials and methods

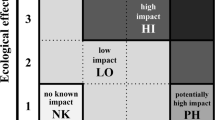

The generic impact scoring system (GISS) is a semi-quantitative tool which relies on published evidence of impact of alien species. Impacts are quantified in 12 categories on a scale from level 0 (no impact detectable) to level 5 (the highest impact possible) with verbal descriptions attached to each level to avoid assessor bias (Nentwig et al. 2016). Several reasons may lead to an impact of 0 (no data available, no impacts known, not detectable, or not applicable) but this does not affect the final result. We discussed this in detail in Kumschick et al. (2015). To perform the GISS assessment, see Table S1.

For the selection of the worst alien species in Europe, we gathered all GISS-assessed taxa from previously published studies including birds (Kumschick and Nentwig 2010; Kumschick et al. 2016; Turbé et al. 2017), mammals (Nentwig et al. 2010), amphibians (Measey et al. 2016), fishes (Van der Veer and Nentwig 2014), terrestrial invertebrates (Vaes-Petignat and Nentwig 2014), spiders (Nentwig 2015), aquatic invertebrates (Laverty et al. 2015), and plants (Rumlerová et al. 2016). We included an additional 52 species assessed by González-Moreno et al. (pers. comm.). The species listed under ISSG-100 (ISSG 2017), DAISIE-100 (DAISIE 2008) and all other species from relevant EU regulations or related publications (EC 2000; ECDC 2012; EU 2010, 2014, 2016) were also assessed for the present study. In total, we compiled impact scores for 486 species alien to Europe (Table S2). As for the EU Regulation on invasive alien species (EU 2014), we only considered species with their entire native distribution outside of Europe, i.e. introduced from other continents, thus excluding species that are native to some region in Europe. We also excluded most pathogens and parasites of humans and livestock because their native range is usually unknown.

To identify the worst of the 486 species assessed we used two complementary independent criteria. We first ranked species according to the total sum of impacts, as obtained from the impact levels for the 12 impact categories (method SUM). The highest impact a species can achieve is a score of 60 (12 impact categories × 5 impact levels). Secondly, we conducted a ranking according to the maximum impact of a species per category (method MAX), similar to the procedure suggested for EICAT classification (Blackburn et al. 2014). Prioritizing the maximum scores is based on the argument that a high impact in one category could be considered as more relevant than multiple impacts with lower scores. This argument is justified by the fact that level 5 impact is defined as “major large-scale impact with high damage and complete destruction, threat to native species including local extinctions, or high economic costs”, thus it is largely irreversible. In contrast, level 4 impact is defined as “major impact with high damage, major changes in ecosystem functions, decrease of native species, or major economic loss”, but such strong impact still can be considered as reversible (Nentwig et al. 2016). Thus, we first ranked all species according to the number of impact categories in which they scored 5. Then we ranked those without a score of 5 in any category according to their frequency of level 4 scores; afterwards the frequency of level 3 scores and so on. For each of the two ranking methods (i.e. SUM and MAX), we selected the 100 highest scoring aliens (or more if ranks were tied). Because both ranking methods have their merits and are complementary, both lists were merged for the final list, i.e. species that occurred on either list or on both were considered for the final list.

Results

From our list of 486 assessed alien species (Table S2), the scores of the total impact of the 100 highest-ranking species (method SUM) ranged from 38 to 16. The total score of 16 was found in 19 species covering positions 88–106, thus making it impossible to select exactly 100 species. According to the second ranking method (method MAX), the 100 highest-ranking species had either at least a score of level 5 in one impact category or a score of level 4 in at least two impact categories. Merging all species from these two lists yielded 149 species. Of these, 75 species were present on both lists, 43 only on the MAX list, and 31 only on the SUM list. Thus, each ranking method missed alien species that the other method considered as having a high impact. For example, the MAX method did not include hogweed species (Heracleum spp.) that scored a total impact sum of 24 but did not score 5 or 4 in any particular impact category (Table 1). Conversely, the SUM method did not include 12 species with scores of 5 in at least one impact category, indicating that their invasion can have devastating consequences through at least one mechanism. Examples include the ruddy duck (Oxyura jamaicensis) which hybridize with the native white-headed duck (Oxyura leucocephala), and two species of crayfish (Oronectes spp.) which transmit the crayfish plague (Table 1). The combination of the two methods therefore leads to the most inclusive list of the worst aliens. Our procedure identified 54 plants (6 non-vascular plants and algae, 48 vascular plants), 49 invertebrates (among them 18 insects, 12 crustaceans, 8 mollusks, and 6 nematodes), 40 vertebrates (18 mammals, 14 fish, 6 birds, 2 amphibians) and 6 fungi as the worst aliens, thus including representatives from all major taxonomic groups. The terrestrial environment is represented by 64% of these species, freshwater by 26%, and marine habitats by 10% (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the here proposed list of 149 alien species in Europe is the most comprehensive, transparent and objective list developed to date that ranks alien species across various taxa according to their overall impacts. However, we are aware that no list will meet all expectations. Some of the species that do not appear on our list, but are included in other expert-based lists are Ailanthus altissima, Impatiens glandulifera, Diabrotica virgifera, Drosophila suzukii, Leptinotarsa decemlineata, Trachemys scripta elegans or Vespa velutina. These species do not rank highly on our list as currently their total demonstrated impacts are “only” in the range of 11–14 sum of scores and their maximal scores do not exceed a single score of 4. This indicates that we currently lack rigorous scientific proof that impacts of some of these flagship invaders are as serious as perceived by experts. Impatiens glandulifera for example, introduced over 100 years ago from India to Europe, was shown to have rather low impacts on species diversity despite its high cover (Hejda et al. 2009). Herbivorous insects such as Diabrotica virgifera or Drosophila suzukii have a high (score 4) but not devastating impact in their specialized niche but no or only low impacts in other GISS impact categories. However, the impact of a given species may change over time, thus in the future these species might cause higher impacts or additional impacts might be discovered. This also points to the fact that we need more research on the effects of many alien species, and new results might call for updating the list presented here. The same is true for future new arrivals of alien species with high impact: they may also qualify for a list of the worst alien species. Thus both aspects, improved knowledge and more alien species, are likely to generate the need for regular reanalysis, perhaps at 10 years intervals.

The comparison with other 100 worst lists reveals that our selection identifies most of the alien species that were considered as problematic by experts. Our list includes 59 of the DAISIE-100 list (DAISIE 2008). Among the excluded DAISIE-100 species, 19 are marine species, 8 herbivorous insects and 7 plants; for neither of them we found large overall impacts. Four DAISIE-100 species are of European origin, thus cannot be considered here. From the 32 species on the ISSG-100 that fit our selection criteria and occur in Europe, only 6 species (19%) did not make it on our list because their documented impacts were not high enough compared to other aliens in Europe.

The European Union published a list of “alien species of Union concern” initially containing 37 species (EU 2016). Further additions increased the list to 49 species after a complex political process (EU 2017), but more than 100 species were proposed by experts (Roy et al. 2014). Four of these 49 species do not currently occur in Europe, but although they could establish, they cannot be considered for a list of the worst aliens in Europe. Thirteen of the remaining 45 species are not on our list as they were excluded prior to screening or because they scored too low. What is more alerting, however, is that besides the overlapping 32 species found in the EU regulation and on our list, none of the remaining 117 high impact species from our list were included into the EU list of “species of Union concern” and only 16 of our first 49 species with the highest impact made it on the EU list of 49 species. Obviously, it takes more than a high impact for a species to be included on a regulated list. The EU lists a species only if it is likely that its inclusion will effectively prevent, minimize or mitigate its impact (EU 2016), and often the most widespread and/or highly impacting species are too costly to be managed effectively. Also economic interests such as with Acacia, Robinia and Eucalyptus species in forestry can prevent the inclusion on such a regulatory list.

The EU is very stringent in species selection and they require the support from their member states to be approved, therefore, such a list can only be seen as the lowest common denominator after a long compromise searching process. This could be a reason for the complete lack of marine species on the list of “EU concern”, whereas aquatic plants (10 species), crayfish (5 species) and squirrels (4 species) are well represented. In addition, the EU list does not include species which are “regulated elsewhere”, such as alien species with impact on agriculture, forestry or human health. All other mentioned 100-lists include such species which aggravates a direct comparison between political and scientific lists.

Our 149 worst species list contains 64 species that do not appear in other worst lists (DAISIE-100, ISSG-100, EU 2017). Examples include Varroa destructor (rank 8 on our list), an Asian ectoparasite of the honey bee that has been implicated in the global pollinator crisis (Potts et al. 2010); Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus (rank 18), the fungus responsible for ash dieback, changes in forest composition and related diversity loss (Gross et al. 2014); Carassius auratus (rank 20), the Chinese gold fish, which causes decline of native amphibians (Cats and Ferrer 2003); and the oomycete Phytophthora plurivora (rank 26), responsible for the dieback of numerous tree species, among them beech and oak (Schoebel et al. 2014). This indicates that even high-impacting alien species may escape the perception of experts. The selection process behind the list presented here, including screening of large databases of alien species and a semi-quantitative assessment with GISS which considers the published literature, is time-consuming but provides some guarantee that important species are not missed. Therefore, it is justified to recommend that many species from our list should be considered for inclusion on regulatory lists.

Many alien species on our 149 worst list do not yet have an EU-wide distribution. For a national strategy, therefore, regionalized lists would be very important. However, such subsets require detailed distribution maps and targeted collection of data on impact that are applicable to individual regions. So far, the majority of impact assessments did not follow such an approach because there is simply not enough regionally specific information.

Each of the two complementary approaches (SUM, MAX) identified slightly different sets of alien species with high impacts. The SUM approach favors species with multiple impacts in different categories while the MAX approach favors species with very high impacts in a single category. About half of the species on the final list were identified by only one of these two approaches. Depending on the stakeholders’ aim for the prioritization, one or the other might be more appropriate, but both have their merits (Nentwig et al. 2016; Blackburn et al. 2014; Bacher et al. 2017). Thus, we suggest applying either method or their combination depending on the specific needs of the stakeholders.

Our list of the worst aliens in Europe is the first compiled by using a semi-quantitative assessment across taxa and habitats. Such a transparent and reproducible procedure is crucial to ensure the authority of the resulting list. Furthermore, its broad basis of 486 analyzed species makes it less likely that important species are missed. For management purposes, it is increasingly relevant to prioritize alien species. Also politicians have to focus on key species, either for financial or for consensus reasons. In all such regards, an objective list such as the one given here, that is unbiased by expert opinion, taxonomy and environments, can be the basis for evidence based decision making. Such a list is also an ideal tool to fulfill the Aichi biodiversity target 9 that requires prioritization of invasive alien species based on scientific evidence by 2020 (CBD 2017).

Change history

02 February 2018

Unfortunately, the following names of plant species in Table 1 were spelled incorrectly.

References

Bacher S, Blackburn TM, Essl F, Genovesi P, Heikkilä J, Jeschke JM, Jones G, Keller R, Kenis M, Kueffer C, Martinou AF, Nentwig W, Pergl J, Pyšek P, Rabitsch W, Richardson DM, Roy HE, Saul WC, Scalera R, Vilà M, Wilson JRU, Kumschick S (2017) Socio-economic impact classification of alien taxa (SEICAT). Methods Ecol Evol. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12844

Blackburn TM, Essl F, Evans T, Hulme PE, Jeschke JM, Kühn I, Kumschick S, Markova Z, Mrugala A, Nentwig W, Pergl J, Pyšek P, Rabitsch W, Ricciardi A, Richardson DM, Sendek A, Vilà M, Wilson JRU, Winter M, Genovesi P, Bacher S (2014) A unified classification of alien species based on the magnitude of their environmental impacts. PLoS Biol 12(5):e1001850. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001850

Cameron EK, Vilà M, Cabeza M (2016) Global meta-analysis of the impacts of terrestrial invertebrate invaders on species, communities and ecosystems. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 25:596–606

Cats LB, Ferrer RP (2003) Alien predators and amphibian declines: review of two decades of science and the transition to conservation. Divers Distrib 9:99–110

CBD (2017) Strategic plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020. Target 9. Convention on biological diversity. https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/rationale/target-9/

DAISIE (2008) Species accounts of 100 of the most invasive alien species in Europe. In: Handbook of alien species in Europe. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 269–474

EC (2000) Council Directive 2000/29/EC of 8 May 2000 on protective measures against the introduction into the community of organisms harmful to plants or plant products and against their spread within the community. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/29/2014-06-30

ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control) (2012) Guidelines for the surveillance of invasive mosquitoes in Europe. ECDC, Stockholm

Elton CS (1958) The ecology of invasions by animal and plants. Methuen, London

EU (2010) Commission Regulation (EU) No 206/2010 of 12 March 2010 laying down lists of third countries, territories or parts thereof authorised for the introduction into the European Union of certain animals and fresh meat and the veterinary certification requirements (Text with EEA relevance). Official Journal of the European Union L 73/1. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32010R0206

EU (2014) Regulation (EU) No 1143/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 on the prevention and management of the introduction and spread of invasive alien species. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1417443504720&uri=CELEX:32014R1143

EU (2016) Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1141 of 13 July 2016 adopting a list of invasive alien species of Union concern pursuant to Regulation (EU) No 1143/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1468477158043&uri=CELEX:32016R1141

EU (2017) Invasive alien species of Union concern. Luxembourg, Publication Office of the European Union (http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/pdf/IAS_brochure_species.pdf

Gross A, Holdenrieder O, Pautasso M, Queloz V, Sieber TN (2014) Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus, the causal agent of European ash dieback. Mol Plant Pathol 15:5–21

Hejda M, Pyšek P, Jarošík V (2009) Impact of invasive plants on the species richness, diversity and composition of invaded communities. J Ecol 97:393–403

ISSG (2017) 100 of the world’s worst invasive alien species. Invasive Species Specialist Group. http://www.issg.org/worst100_species.html

Kumschick S, Nentwig W (2010) Some alien birds have as severe an impact as the most effectual alien mammals in Europe. Biol Conserv 143:2757–2762

Kumschick S, Bacher S, Marková Z, Pergl J, Pyšek P, Vaes-Petignat S, van der Veer G, Vilà M, Nentwig W (2015) Comparing impacts of alien plants and animals using a standard scoring system. J Appl Ecol 52:552–561

Kumschick S, Blackburn TM, Richardson DM (2016) Managing alien bird species: time to move beyond “100 of the worst” lists? Bird Cons Int 26:154–163. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270915000167

Laverty C, Nentwig W, Dick JTA, Lucy FE (2015) Alien aquatics in Europe: assessing the relative environmental and socio-economic impacts of invasive aquatic macroinvertebrates and other taxa. Manag Biol Invasions 6:341–350

Measey GJ, Vimercati G, de Villiers FA, Kokhatla M, Davies SJ, Thorp CJ, Rebelo AD, Kumschick S (2016) A global assessment of alien amphibian impacts in a formal framework. Divers Distrib 22:970–981. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12462

Nentwig W (2015) Introduction, establishment rate, pathways and impact of spiders alien to Europe. Biol Invasions 17:2757–2778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-015-0912-5

Nentwig W, Kühnel E, Bacher S (2010) A generic impact scoring system applied to alien mammals in Europe. Conserv Biol 24:302–311

Nentwig W, Bacher S, Pyšek P, Vilà M, Kumschick S (2016) The generic impact scoring system (GISS): a standardized tool to quantify the impacts of alien species. Environ Monit Assess 188:315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-016-5321-4

Potts SG, Biesmeijer JC, Kremen C, Neumann P, Schweiger O, Kunin WE (2010) Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol Evol 25:345–353

Pyšek P, Jarošík V, Hulme PE, Pergl J, Hejda M, Schaffner U, Vilà M (2012) A global assessment of invasive plant impacts on resident species, communities and ecosystems: the interaction of impact measures, invading species’ traits and environment. Glob Change Biol 18:1725–1737. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02636.x

Roy H, Schonrogge K, Dean H, Peyton J, Branquart E, Vanderhoeven S, Copp G, Stebbing P, Kenis M, Rabitsch W, Essl F, Schindler S, Brunel S, Kettunen M, Mazza L, Nieto A, Kemp J, Genovesi P, Scalera R, Stewart A (2014) Invasive alien species—framework for the identification of invasive alien species of EU concern. Brussels, European Commission (ENV.B.2/ETU/2013/0026). http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/invasivealien/docs/Final%20report_12092014.pdf

Rumlerová Z, Vilà M, Pergl J, Nentwig W, Pyšek P (2016) Scoring environmental and socioeconomic impacts of alien plants invasive in Europe. Biol Invasions. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-016-1259-2

Schoebel CN, Stewart J, Grünwald NJ, Rigling D, Prospero S (2014) Population history and pathways of spread of the plant pathogen Phytophthora plurivora. PLoS ONE 9:e85368. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085368

Turbé A, Strubbe DE, Mori E, Carrete M, Chiron F, Clergeau P, González-Moreno P, Le Louarn M, Luna A, Menchetti Mattia, Nentwig W, Pârâu LG, Postigo JL, Rabitsch W, Senar JC, Tollington S, Vanderhoeven S, Weiserbs A, Shwartz A (2017) Assessing the assessments: evaluation of four impact assessment protocols for invasive alien species. Divers Distrib. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12528

Vaes-Petignat S, Nentwig W (2014) Environmental and economic impact of alien terrestrial arthropods in Europe. NeoBiota 22:23–42

Van der Veer G, Nentwig W (2014) Environmental and economic impact assessment of alien and invasive fish species in Europe using the generic impact scoring system. Ecol Freshw Fish 24:646–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/eff.12181

Vilà M, Hulme PE (eds) (2017) Impact of biological invasions on ecosystem services. Springer, Heidelberg

Vilà M, Basnou C, Gollasch S, Josefsson M, Pergl J, Scalera R (2008) One hundred of the most invasive alien species in Europe. In: Handbook of alien species in Europe. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 265–268

Vilà M, Basnou C, Pyšek P, Josefsson M, Genovesi P, Gollasch S, Nentwig W, Olenin S, Roques A, Roy D, Hulme PE, DAISIE Partners (2010) How well do we understand the impacts of alien species on ecosystem services? A pan-European, cross-taxa assessment. Front Ecol Environ 8:135–144. https://doi.org/10.1890/080083

Acknowledgements

The support from COST Action TD1209 Alien Challenge is gratefully acknowledged. MV acknowledges the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad projects IMPLANTIN (CGL2015-65346R) and the Severo Ochoa Program for Centres of Excellence (SEV-2012-0262). PP was supported by long-term research development project RVO 67985939 (The Czech Academy of Sciences), and project no. 14-36079G, Centre of Excellence PLADIAS (Czech Science Foundation). SK acknowledges funding from the South African National Department of Environmental Affairs through its funding of the South African National Biodiversity Institute’s Invasive Species Programme, and the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence for Invasion Biology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised: (The detailed corrections has been provided in the Correction article).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10530_2017_1651_MOESM1_ESM.xlsx

Supplementary Table S1. Self-explanatory spreadsheet table (in Microsoft Excel) for performing the GISS impact assessment (Nentwig et al. 2016). (XLSX 63 kb)

10530_2017_1651_MOESM2_ESM.docx

Supplementary Table S2. List of all species assessed by the generic impact scoring system GISS with scores. (DOCX 70 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nentwig, W., Bacher, S., Kumschick, S. et al. More than “100 worst” alien species in Europe. Biol Invasions 20, 1611–1621 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-017-1651-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-017-1651-6