Abstract

Agrifood scholars have long called for changes to the dominant food system, with the goal of making food systems more sustainable and just. This paper focuses on the ways in which recent and future food system shocks provide an opportunity for sustainable transitions in the food system. However, this requires strategic engagement on the part of alternative agrifood initiatives—agrifood niches—otherwise food systems are likely to return to business as usual. Drawing on the multi-level perspective (MLP) within the sustainability transitions framework, core themes that emerge from social science studies of disasters in agrifood systems are identified. These are summarized as resources, polices, and practices that can assist niches in transforming agrifood regimes in response to disasters. The results highlight that while niches are generally independent of governments, niches would be better positioned to engage in post disaster agrifood change if they have some pre-existing connections with local or regional governments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As a result of the current trends in climate change, and the likelihood of more frequent and intense disasters, there is renewed urgency in addressing agrifood systems response and adaptation to disasters. Simultaneously, within agrifood studies scholars have long called for changes to the dominant agrifood system, with an emphasis on making agrifood systems more sustainable and just (Morgan et al., 2006; Sachs 2020). Less explored, has been the ways in which disasters can provide opportunities for change in our agrifood systems (Becker and Reusser 2016; Werkheiser 2023; Davidson et al. 2016). Drawing on the multi-level perspective (MLP) within the sustainability transitions framework, I set out to identify core themes that emerge from studies of disasters in agrifood systems, and argue these themes should inform alternative agrifood initiatives—agrifood niches—as this can facilitate future food system changes that are more sustainable, resilient, and just.

By contrast, continuing to neglect the opportunities for “progressive change” in agrifood systems in the context of unexpected disasters, most likely ensures a return to the status quo or business as usual (Werkheiser 2023, 104). The maintenance of the status quo occurs due to lock-ins, which are path-dependent processes that inhibit change as the systemic level (Williams et al. 2024). There are several types of lock-ins within agrifood systems. For example, increasing returns to adoption at the production or processing level (i.e., technology, infrastructure, and/or knowledge). Williams et al. (2024), explain that risk aversion and the sunk costs of investments make it difficult to change the sociotechnicalFootnote 1 paradigm. The status quo is also maintained through powerful food system actors, which include food retailers (Bui et al. 2019) and industrial processors (Walton 2024). Finally, government policies, and the underlying knowledge that supports these policies, generally reinforce the dominant paradigm, making it difficult “for more transformative solutions to gain traction” (Williams et al. 2024, 5). Conversely, Williams et al. (2024) identifies alternative values that are in opposition to the existing paradigm and a degree of frustration with current conditions as facilitating sustainability transitions. My contribution is to assert that the disruptions caused by disasters offers opportunities for niches to disrupt the dominant regime, but to date the systematic study of disasters in agrifood systems has been neglected, which can limit the transformative potential of agrifood niches.

To date the disasters literature and the agrifood studies literature have had limited cross-fertilization, and neither field has engaged systematically in thinking about agrifood systems immediately following disasters. This article sets out to review the social science research that has focused on a wide range of disasters, with the objective of better understanding the types of issues that emerge within agrifood systems due to disasters. From these results, the goal is to identify core themes that emerge from disasters in agrifood systems to guide actors engaged with agrifood niches in how they can engage and respond in the context of disasters and catastrophes in order to advance more just and sustainable food systems in the future. These themes are summarized as the resources, policies, and practices that seem most relevant to niches for engaging in agrifood disaster response.

Thus, this article has four sections. First, identification of core ideas emanating from the social science disasters literature that can inform an analysis of disasters in the agrifood system. Second, I discuss the relevance of the sustainability transitions literature for thinking about agrifood system adaptation to disasters, especially at the point of production. Third, a review the existing social science literature focused on agrifood systems and disasters, summarizing key findings. The article closes with a discussion of the types of resources, policies, and practices needed for agrifood niches to disrupt the dominant regime based on the results of the literature focused on disaster recovery in agrifood systems.

Before moving forward, an explanation of the analytic focus and the terminology used in this review. This work is focused on recovery and response after disasters. In more protracted disasters, like conflict, there is a growing body of literature focused on agrifood systems during disasters (see Béné et al. 2024). The terms disaster and catastrophe will be used interchangeably in the discussion, although there are clear differences (see Table 1). In general catastrophes are the least frequent, and therefore have less literature focused on this subject. There are also situations where people and places can experience successive or repetitive disasters (e.g., Haiti) contributing to cumulative or convergent catastrophes (Tierney and Oliver-Smith 2012). This article analyzes disasters and catastrophes in agri-food systems, as I am interested in considering how sociotechnical niches can support more resilient food systems in the context of disasters and catastrophes that cannot be fully anticipated. In the context of climate change, and other anthropogenic threats (e.g., nuclear fallout), there is a need to consider how disaster response and recovery can contribute to—or prevent—transformative change of the agrifood system (McGreevy et al. 2022; Torhan et al. 2022).

Disaster studies—Scale and type, emergent groups, and vulnerability

Disasters as a field of study generally originated out of the 1940s nuclear events—U.S. deployment of nuclear weapons against Japan in WWII and the Soviet Union’s successful nuclear test in 1949 (Sylves 2019; Tierney 2019). The early disaster studies research generally focused on how social systems continue to function and adapt to disasters, whereas beginning in the 1980s the field began to embrace a more conflict-oriented approach, focusing more on the creation of and unequal experiences with disasters (Tierney 2019).Footnote 2 With a few exceptions, however, disaster studies has not focused on agrifood systems (Ransom and Raymond 2024). Despite this inattention to the subject, there are three themes from disaster literature that are extremely relevant for an analysis of agrifood systems: (1) scale and type of disaster; (2) emergent groups; and (3) vulnerability.

Scale and the type of disaster matter

In terms of scale, Tierney (2019) does a nice job of summarizing the difference between an emergency, a disaster, and a catastrophe (see Table 1). For our purposes the key point to understand is that as the impact becomes more widespread and severe—moving from an emergency to a catastrophe—the type of response required changes. In catastrophes, the local and regional level responses are generally paralyzed and the public is the only source for the initial response (Tierney 2019, 5). The involvement of the public at least initially is also true for disasters, but there is an assumption that disaster plans facilitate the introduction of local and regional assistance more quickly. In the context of thinking about how people will continue to procure food and water for consumption after a catastrophe, it is important to acknowledge that these things will emerge spontaneously (as disaster plans will be insufficient) and from local community members. Therefore, moving from emergencies towards catastrophes, relying on “top-down, ‘command and control’ models of disaster recovery” become extremely questionable (Matthewman and Uekusa 2021, 968, citing Tierney 2014).

Alongside scale is the type of disaster. The more applied disaster and emergency management literature focuses on preparation for different types of disasters (Fussell et al. 2017; Noy and duPont Iv 2018; Nordine and Zeuli 2022). Different disasters (e.g., flooding versus famine), demand different responses and resources (e.g., new farm inputs for flooded locations versus outside food aid to diminish famine). Unexpected events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, brought to light many vulnerabilities in food supply chains and social systems in the U.S., the United Kingdom, and globally (Biehl et al., 2018; Sanderson, 2020). Whereas dominant emergency response scenarios have people gathering at a designated location, the uniqueness of COVID requiring social isolation demanded creative solutions. For example several cities initially relied upon the online retailer company Amazon and later the national guard to help deliver food to the most vulnerable (Baltimore Food Policy Initiative 2020).

Emergence of individuals, groups, and organizations after a disaster

Emergence is one topic that, with a few exceptions, is relevant across different disasters. The study of disasters has generated conclusive evidence that social bonds do not break down even in frightening situations due to pro-social behavior and the resilience of social bonds (Tierney 2019). Instead, many scholars have documented that there is a range of emergent social phenomena, where people come together to form groups to help others (Matthewman and Uekusa 2021; Solnit 2010). This has been categorized as an almost euphoric state of people post disaster (Solnit 2010), and this can be a powerful resource after a disaster, but it is a temporary state of being (Matthewman and Uekusa 2021). While there is overlap between this emergent, pro-social bonding and the concept of social capital, Matthewman and Uekusa (2021) warn that the two concepts are not the same, although pre-existing social capital can contribute to emergent groups. Finally, within the concept of emergence, is the idea of improvisation that occurs in the midst of disaster response, but with an emphasis on the idea that improv works best when building on a repertoire of training or education, experience, and knowledge of the community (Glantz and Ramírez 2018; Kendra and Wachtendorf 2007; Tierney 2019). Despite emergence occurring across diverse disasters, disasters that unfold more slowly (i.e., an oil spill) and incidents where members of the public may not know how to protect themselves (i.e., nuclear event), can slow emergent social phenomenon (Tierney 2019). Finally, as discussed in the next section, emergence may not be experienced equally within communities.

Vulnerability matters

Vulnerable populations are an important dimension to disaster recovery. Populations deemed vulnerable prior to a disaster may also not have the same experience of emergent social phenomena due to a wide range of reasons, including fewer social connections (Tierney 2019). Existing research focused on the impact and recovery of disasters indicates that pre-existing inequalities are likely to be exacerbated by disasters (Bolin and Kurtz 2018; Enarson et al., 2018; Tierney 2019). Marginalized populations, including the poor, women and racial/ethnic minorities, are more likely to be harmed by a disaster and are slower to recover (Frankenberg et al. 2011; Klinenberg et al. 2020; Nagel 2012; Rahman 2013). Recognizing the importance of vulnerability is required when thinking about the impact and recovery from disasters in agrifood systems.

Sustainability transitions and the multi-level perspective

Transitions in our food system are necessary for the purposes of sustainably and needed to respond to the consequences of climate change and other disasters. Much of the work that has focused on governing transitions has recognized that this does not happen with a purely top-down approach (Köhler et al. 2019). The sustainability transitions research advocates for “governance and policy experimentation” that can advance social learning, challenge dominate values, bring in new actors, and accelerate diffusion of new solutions (Köhler et al. 2019, 9). Thus, a plurality of actors, not just governments, are involved in governing transitions. In the case of catastrophes, the larger the scale and scope, the more the public will be involved in initial recovery response. I argue that utilizing a transitions framework can better inform our thinking about shocks to agrifood systems and the role of a wide range of actors. Specifically, the multi-level perspective (MLP) can help us to reconsider the role of disaster response in moving us towards food systems that can be more resilient, sustainable, and just in the context of shocks.

Within the sustainability transitions literature there is a growing recognition that disruptive events can play a key role in inducing food systems transitions (Davidson et al. 2016). Yet, there is a need to be more intentional in cultivating niches that can possibly facilitate future food systems that are more sustainable (Hinrichs 2014; Werkheiser 2023), as there are structures, powerful interests, and path dependencies that work against significant change. With a growing number of disasters that threaten agrifood systems and food security, there is an opportunity to explore how niches can engage in disaster response thereby contributing to transformation of agrifood systems. Simultaneously, it is imperative that we appreciate the challenges of ensuring food security during periods of disasters. Below is a brief summary of the MLP literature before moving on to the methodology and analysis.

Multi-level perspective

MLP within sustainability transition theory focuses on the way “transitions come about through dynamic processes within and between three analytical levels” (Köhler et al. 2019, 4). Figure 1 provides an overview of the three levels, which are niches, sociotechnical regimes, and landscapes. Niches are considered protected spaces where radical innovations and learning occur (Geels 2004; Lawhon and Murphy 2011). In the context of food systems, alternative food initiatives, such as food hubs (Hinrichs 2014), and other grassroots groups fighting for change (Werkheiser 2023), have been identified as potential niche innovations. While historically, sustainability transition had a technological bias, more recent scholarship acknowledges the social and technological (sociotechnical) dimensions of niches (Hinrichs 2014). The next level are sociotechnical regimes, which are meso-level constructs that contain prevailing routines and practices that govern or stabilize existing systems (Davidson et al. 2016; Köhler et al. 2019). At the level of the regime there can be powerful interests protecting the status quo, as well as path dependencies and so-called lock-ins that make change difficult. Within the broader sustainability transition literature, several have focused on the interlocking combination of infrastructure, powerful interests, and long-standing subsidies that have locked in less sustainable energy generation and transmission systems. Within the agrifood system, food safety laws when combined with powerful interests can limit innovation (Bain et al. 2010; Ransom et al. 2017).

The MLP framework for sociotechnical regime transitions (Geels 2019)

Finally, at the macro level is the landscape, which consists of the political, social, and cultural values and institutions that form the “structural backbone of a society” and thus change can be considered slow (Davidson et al. 2016, 360). Nonetheless, landscapes do change, particularly as public opinion shifts around topics, like climate change (Hinrichs 2014). Ultimately, both landscapes and regimes can experience sudden exogenous and endogenous disruptive forces. As Davidson et al. (2016, 361) explain, “existing structures and relationships express a tendency for negative feedback and structural path-dependency, rendering contemporary social systems simultaneously highly resistant to change, and susceptible to crises.” Within this context, I summarize social science studies of specific disasters in agrifood systems to identify the types of resources, polices, and practices that can assist niches in transforming agrifood regimes in response to disasters and catastrophes.

Methodology

Academic articles identified and coded for this project occurred in two waves. Wave II is the focus of the analysis in this paper, as Wave I was previously reported out on (Ransom and Raymond 2024). However, for the purposes of clarity I include an overview of Wave I and II article identification, as a subset of articles from Wave I were added to the analysis in Wave II.

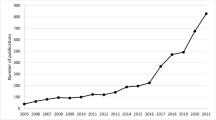

Wave I: social science articles focused generally on disasters and food were identified. Table 2 provides an overview of the key search terms used in identifying relevant articles. A total of 71 article citations were downloaded within these criteria, and all of these were articles published in English. The year of publication ranged from 1981 to 2021. Initial coding categories were created based on the knowledge of existing disaster literature. Subsequent coding categories were created as they emerged through an initial coding of ten articles.

Wave II: After completion of general disaster literature coding, there was a search for social science literature for specific disasters which included reference to agriculture and food security. The specific disasters included: famine, nuclear, COVID-19, hurricane, and flood. Like Wave I, all searches were limited to journal articles published in English. Once article titles for each type of disaster were downloaded, a random number generator was utilized to select a sub-sample of approximately 30% of the articles within each disaster category to read and code. There were 24 articles coded during Wave I that qualified as one of the disaster categories I searched in Wave II. Previously coded articles were subsequently added to the Wave 2 analysis.

All articles, both in Wave I and Wave II were coded quantitatively and qualitatively. Quantitively, the coding categories included the year of publication, the type of disaster (primary and secondary), the scale of data collection (e.g., individual, household, community), the type of data utilized in the article (e.g., survey data, secondary data, interviews), and as relevant: the dimensions of food security (e.g. availability, access, etc.), the vulnerable population of focus, the geographic focus (e.g. Africa, North America), and the type of food or commodity of focus. Each article was reviewed and the main findings summarized, in addition to identifying any policy relevant recommendations that were made.

There are a few limitations to this research, notably an English language bias and the search terms and databases utilized. There is non-English scholarship that would fit within the search criteria but did not appear in this search using English words. Additionally, except for COVID-19, Scopus, an abstract and citation database was not used in the search for articles.Footnote 3 Finally, while a wide-range of disasters have been included, there are additional disasters that optimally will be included in future analysis, including earthquakes and droughts. One disaster search term that was not included in the Wave II analysis is “climate change.” During the first wave of article collection, climate change was 25% of all the articles. However, upon closer inspection over 50% of these articles were commentaries, which means they were not based on studies or had no data to support conclusions drawn. For the remaining climate change articles that did focus on studies the majority included some type of disaster attributed to climate change, such as floods, hurricanes, or extreme temperatures. Thus, moving forward there was a focus on searching specific types of disasters, as opposed to going with the more general reference to climate change.

Themes within specific disasters

Famine—The state matters

Academic analyses of famines cover a wide time-period, dating from the 1315 (The Great European Famine) to present day analysis of famine in Somali and the Horn of Africa (see Table 3). While there are different variables that prove unique to each official famine, a dimension that cuts across all famines is the role of the State, and in more modern times, international governing bodies. In other words, to reach a stage of famine requires multiple concurrent shocks, but appropriate state or international intervention can prevent full-scale famine. Of course, some historical examples identify the State as purposely ignoring the famine (USSR), or in the case of China, the State lacked the appropriate information about what was occurring amongst the general population (Chang and Wen 1997). For famine to occur, it is usually a combination of factors, including negative weather events (i.e., too little rain) that contribute to reduced crop yields, rising market prices, and bottlenecks in importing foods.

A few articles using qualitative methods afford us a more nuanced analysis of famine survival and recovery. Rocheleau (1991) focuses on gendered knowledge systems, and how those changed as drought persisted and famine emerged. Specifically, the researchers, who were already engaged in agroforestry projects in Kathama, Kenya, documented changing interests in tree species and changing power dynamics. Specifically, indigenous knowledge became more valued and women’s groups that focused on reciprocity and mutual aid within the community using ethnobotany to feed and treat community members gained more legitimacy (Rocheleau 1991).

In the case of Somalia, external response was extremely delayed, due in large part to political instability the region. Through interviews with 260 individuals who survived, the authors establish that affected groups “drew support from their own communities, their business groups, their Diasporas, and their own neighbors and kin to survive prior to any outside assistance arriving” (Maxwell et al. 2016, 64). Overall, those that survived did so through what the authors call diversification, flexibility, and social connectedness.

Diversification refers to both livelihood strategies and assets, and they argue this mostly applies to reducing risks, not as a means of coping with shocks. So, for example, investing in camels that are more drought tolerant, or ensuring one’s social network is diverse. Flexibility applies to people’s ability to be mobile, either seeking employment opportunity, humanitarian aid, or migration with livestock. Finally, social connectedness is the strength of an individual or household’s social networks. Maxwell et al. (2016, 68) note that those most dependent on “the rural economy with fewest relatives and clan-members outside of these areas were most vulnerable.” Children under the age of five, as well as two social groups, the Rahanweyn and the Bantu/Jarer, which are social groups in Somalia that are considered as second- and third-class citizens were most negatively impacted. The authors note that changing gender relations allowed women to be less constrained in their mobility during this crises, thereby increasing their chances of survival. The authors conclude with policy relevant ideas, including international organizations better understanding social connections for the purposes of monitoring severity of the deteriorating conditions, providing targeted humanitarian assistance, and allowing for remittances to continue to arrive from diaspora communities.

Another indicator of deteriorating conditions are the types of assets households sell off (Baro and Deubel 2006). In their summary of twentieth century African famines, assets that take the form of self-insurance (e.g., jewelry) are liquidated well before productive assets (e.g., livestock, land, or tools). The sale of productive assets can be “considered a clear distress signal that indicates a lack of other options” (Baro and Deubel 2006, 529). Forced migration of a household is a last choice (Baro and Deubel 2006 citing; Corbett 1988).

Some dimensions that emerge not only in relation to famine, but of relevance to other disasters, are disease prevalence and land rights. Disease can contribute to famine, but also disease increases during famine due to a lack of healthcare systems and sanitation breakdowns (Mokyr and Gráda 2002). In the case of land rights, Azadi et al. (2022), argues for enhancing institutional and political support for land rights of local populations as way to ensure more investment in agriculture and increase overall productivity. In contrast, Rocheleau (1991) argues that privatized land rights contributed to women having to fight for access to lands controlled by men.

Hurricanes—The wrong kind of water

Water, water everyone, nor any drop to drink, a phrase from the 1798 poem, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, is appropriate for the purposes of focusing on agriculture and hurricanes (also includes typhoons and cyclones). There are many devasting consequences of hurricanes for people and agricultural production due to high winds and flooding, but the recovery from a hurricane can also be challenging due to higher levels of saline in soils and in freshwater and this damages crops and ecosystems (Williams 2010). Several articles recommend that more research needs to be done on saline tolerant crops, including rice and sweet potatoes (Iese et al. 2018; Stone 2009). Presumably, if more saline tolerant crops were available, the seeds could be strategically located in hurricane prone regions, to facilitate faster recovery.

Another common theme within the hurricane articles is a focus on vulnerable populations, including children, women, elderly, poor, and those dependent on agricultural livelihoods (Loebach 2019; Paul et al. 2012; Paul and Routray 2011; Trotman et al. 2009). Generally, vulnerable groups have a harder time recovering in the short- and long-term, often experiencing higher rates of food insecurity. In the case of smallholders, they often struggle to adapt or recover (Bacon et al. 2017; Harvey et al. 2018). In addition, many external programs put in place to assist in recovery often miss vulnerable populations, thus several studies focus on the need for targeted interventions in both developed and developing countries (Clay et al. 2018; Fitzpatrick et al. 2020; Loebach 2019).

One unique study focused on typhoon disasters pre-1945 finds that disaster politics are shaped by multiple dimensions of “distance” between citizen-victims and the state. Van Klinken (2021) explains:

This leads to two obvious but often neglected conclusions about the power dynamics surrounding historical typhoon disasters. The first is that the impact of a disaster on state politics is strong if the disaster strikes an urban industrial population close to the heart of power. Conversely, impact is weak if the disaster strikes an agrarian population in a peripheral rural area. The second is that protection from recurring typhoons is more likely if the state has high capacity (is wealthy) and if it practices [sic] democratic consultation. Protection is less likely if the state has low capacity (is poor) and if it is authoritarian. The latter situation is rife with collective action problems and results in state incoherence. (pp. 44)

VanKlinken’s analysis, while focused on historical data in the Philippines, Bengal, and Japan, proves relevant for thinking about future disaster response, particularly within the current time period of an increasing number of authoritarian regimes (Repucci and Slipowitz 2022).

In the hurricane literature a broader issue that emerges and has the potential to positively impact vulnerable populations recovery from disasters is the idea of building local capacity, so-called bottom-up approaches, to disaster planning and response. In part this is driven by a recognition that involvement of vulnerable populations in the planning and implementation process will better empower vulnerable populations (Trotman et al. 2009). But it is also built on the idea of improving social connections in advance of a disaster, as the more socially integrated a community is the better the community will be in responding to a disaster (Clay et al. 2018; Fitzpatrick et al. 2020; Le Dé et al. 2018; Rañola et al. 2015; Savage et al. 2020; Smith 2013; Toote 2016). One area that several articles focus on was the role of community gardens in post-hurricane recovery. Not only in providing fresh food and a sense of collective efficacy (Chan et al. 2015; Savage et al. 2020), but also as a political act to avert so-called “disaster capitalism” among historically marginalized populations (Kato et al. 2014).

Finally, while not discussed widely, there are a few additional topics worth highlighting. One was an emphasis on hurricane resilient structures and shelters, to reduce loss of life (Haque and Jahan 2016; Li et al. 2015). Another is the role of social media in communicating information during and after a hurricane (Niles et al. 2019). The authors find that average citizens are predominately the ones communicating helpful information (e.g., location of food banks in a community; Niles et al. 2019).

Flooding—Role of the state and the market

There are similar recommendations that emerge from studies focused on flooding and hurricanes, such as the need for identifying safe drinking water (Boori et al. 2017) and reducing water-borne illness (Reed et al. 2022). However, there is a key difference, flooding tends to be a much more regular occurrence in many regions, and there are clearly people and agricultural systems that exist, or have historically co-existed, in flood prone regions. Thus, a few studies identified the positive impacts of flooding, such as more available water for irrigation and soils that have high water-holding capacity (Pratiwi et al. 2020; Reed et al. 2022). Nonetheless, with climate change, the frequency and intensity of floods is increasing, and therefore, even for populations that are used to regular flooding, there are recommendations for offering education programs about climate change (Ajaero 2017; Sherman et al. 2016) and implementing advanced or early warning systems to reduce the negative impacts of the floods (Ajaero 2017; Ashraf et al. 2013; Rehman et al. 2016).

Generally, recommendations within the flooding articles focus on the role of the State in ensuring disaster planning and management. In contrast to the hurricane literature, only a small number of articles spoke of the importance of enrolling locals into the planning and management (Ahmad and Afzal 2021; Singh et al. 2021; Smith and Lawrence 2018), with most articles focused on high-level State engagement. For example, the need for strong institutional frameworks to coordinate large-scale response (Dorosh et al., 2010), including disaster management bodies that have well-planning disaster risk reduction strategies (Bang et al. 2018), and ensure stable food supplies through short-term interventions, but long-term price stability (Yiran et al. 2022). Another dimension of State involvement is a focus on infrastructure, both in advance of floods, but also in response to floods. In advance of floods, buildings and granaries and that can withstand flooding and after floods, restoration of communication networks, roads, and irrigation systems (Ashraf et al. 2013; Dorosh et al., 2010; Pratiwi et al. 2020; Sarker 2016).

There is also a sizable amount of attention on the role of the market and appropriate trade policies. Dorosh et al. (2010, 176) argue that the goal should be to restore private trade as quickly as possible, as it “can enhance price stability and food security more effectively and at far less cost.” More generally, especially in developing countries, there is a focus on improving market access for smallholders as a mechanism to increase their capacity to recover from flooding (Ashraf et al. 2013; Sherman et al. 2016). There is also a need for more investment (with some articles emphasizing private sector investment) in rural areas, such as post-harvest facilities, to again improve the livelihoods of smallholders, but also expand livelihood diversification in rural areas (Chimweta et al. 2022; Hussain et al. 2016; Yiran et al. 2022).

Specific recommendations to better support farmers and agricultural production in flood prone areas include ensuring farmers have “short-duration” seeds, which will expedite crop growth and reduce flood-related losses (Sarker 2016; Yiran et al. 2022), as well as modifying the types of crops grown due to changing weather temperatures and rain patterns (Hussain et al. 2016). Related to this is increasing the information farmers receive, especially weather information, so that farmers can make strategic decisions about when to harvest (Yiran et al. 2022). Two articles also focus on flood recession farming (FRF), a type of farming practiced since antiquity, where farmers use moisture and nutrient rich soil of the floodplains to grow crops after water levels recede (Chimweta et al. 2022; Singh et al. 2021). Both studies, one focused in Zimbabwe and the other in India, note that despite the long-term practice of FRF, this style of production system is understudied.

Finally, a sub-set of studies focused on vulnerable populations. Among the issues identified: targeted cash transfers and credit programs to ensure the poor avoid long-term debt (Del Ninno et al., 2003), rehabilitation of small-scale agriculture (Dorosh et al., 2010), improvement of women’s property rights, and ensuring food aid is provided immediately after an event (Ajaero 2017). More generally, there is an emphasis on livelihood diversification, with the idea that this will reduce food insecurity and improve long-term recovery (Ajaero 2017; Bang et al. 2018; Sherman et al. 2016; Yiran et al. 2022). Finally, children are especially vulnerable during flooding events and should be targeted to improve their nutritional status (Del Ninno et al., 2003).

Nuclear—Transparent communication and local engagement

The impact of nuclear events on humans and the environment is such that the first recommendation that should be highlighted is that we must work to reduce and eventually eliminate nuclear weapons globally (Helfand 2013; Robock and Toon 2010; Toon et al. 2017). The consequences of a nuclear fallout are so devastating, notably the presence of a nuclear winter, that life as we know it will cease to exist. Robock and Toon (2010, 74) describe a nuclear winter as “the smoke from vast fires started by bombs dropped on cities and industrial areas would envelop the planet and absorb so much sunlight that the earth’s surface would get cold, dark and dry, killing plants worldwide and eliminating our food supply.” Thus, it is recommended that everyone should be made aware of the devastating consequences of nuclear war (Scrimshaw 1984), with the goal of encouraging disarmament.

In the case of nuclear meltdowns (i.e., Chernobyl) and disasters (i.e., Fukushima), the core policy recommendations revolve around communication and transparency, as well as more local engagement and preparation. Several authors focus on the need for governments to offer clear and transparent messaging during and after an event, which includes acknowledging when the scientific evidence is uncertain (Belyakov 2015; Lee et al. 2017; Mabon and Kawabe 2018; Miller 2016; Paek and Hove 2019). Given the complex global supply chains that exists, there is also a concern around when trade in agriculture and food products should resume between nations and how best to ensure and communicate that food being imported/exported is safe for consumption (Chang and Takahashi 2021; Kaptan et al. 2018; Koyama and Ishii 2014; Lee et al. 2017). These same studies focus on the fear generated by misinformation. To counter misinformation, some suggestions include offering educational materials so the public can better understand food safety risks associated with radiation (Kaptan et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2017).

Finally, several scholars recommend more inclusion of the public in planning and response. In the case of planning, there is a need to revisit relocation plans for people and animals (Corbett 1983), and emergency food kits must be incorporated into management and policy to ensure people have access to food especially initially (Takebayashi et al. 2020). Given that the initial response to a nuclear event will almost always be local—as outside engagement will be slower to occur—it is suggested that local and provincial governments be involved in disaster planning and that laypeople be involved in the decision-making on food-safety after an event has occurred (Kerr et al. 1992).

COVID-19—Vulnerability and welfare safety nets matter

COVID-19 brought about mass sheltering in place, in combination with dramatic decrease in economic activity, creating a perfect storm of slowing food and agricultural supply chains and reducing people’s incomes, and therefore their capacity to purchase foods. Themes that emerge from these articles include the disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations in terms of food insecurity. There is a focus on vulnerable producers, including small scale fisheries (Grillo-Núñez et al. 2021), smallholder producers (Amjath-Babu et al. 2020; Bamidele and Amole 2021; Ceballos et al. 2020; Love et al. 2021; McBurney et al. 2021), rural poor (Gupta et al. 2021) and women farmers (Kulkarni et al. 2022). Many of these studies emphasized the importance of policies and safety nets being sensitive to local context. In the case of small scale fisheries, those fishers that supplied national markets recovered more quickly than those that supplied international markets (Grillo-Núñez et al. 2021). In India, it was found that farmers who had more mechanization and more access to markets had higher incomes during COVID-19, but their dietary diversity declined due to their reliance on longer supply chains that saw more disruptions (Ceballos et al. 2020). More generally, several studies identified that already vulnerable populations suffered increased vulnerability during COVID-19 (Amjath-Babu et al. 2020; Bamidele and Amole 2021; Kulkarni et al. 2022; McBurney et al. 2021).

Gupta et al.’s (2021) study is unique for being a cross-national examination of two countries’, India and Nepal, rural farming populations. Households in recent years have seen a diversification of income due to out-migration and increased off-farm work, which allowed households to be creative in ensuring that they navigated the pandemic, but they conclude “household-level responses by themselves are unlikely to be enough to avoid widespread economic dislocation” (Gupta et al. 2021, 10). Rather they assert “the state has been critical” (Ibid). In both countries the state being referenced are local and sub-national level governments, but the authors tentatively conclude that India was better able to roll out a more extensive and accessible support systems, especially in terms of public food distribution systems, due to the already existing government support schemes (Ibid).

Vulnerability on the consumption side was another major theme. With decreased money for purchasing food and in some locations decreasing supplies and subsequent increasing prices, consumer strategies included borrowing money, eating fewer meals, consuming cheaper foods, using food charities, going to homes of family and friends, sending children to relatives, bartering and trading for food, and sharing of land to make gardens (Escobar et al. 2021; Hoteit et al. 2021; Steenbergen et al. 2020). In Brazil, a study found that government supplied food baskets did not do enough to offset food insecurity, and it was recommended that the nutritional quality and quantity (based on family size) be increased (Rodrigues et al. 2022). A study in the U.S. found households that increased home food procurement (i.e., gardening, hunting) had higher rates of fruits and vegetables intake (Niles et al. 2021).

Supply-chains were another dimension that several articles focused on, with a few studies focused on how to safely resume operation of supply chains, either through improved safety protocols (Jaacks et al. 2021; Mor et al. 2020), or increasing mechanized service equipment to reduce the need for workers (Pu and Zhong 2020). Along these lines, one study found that subsistence systems were more resilient due to labor availability and local sourcing of inputs (Adhikari et al. 2021). Other studies propose increasing alternative community marketing to support farmers and reduce reliance on long supply chains (Love et al. 2021; Lioutas and Charatsari 2021), as well as purchasing from local farmers to provide local food baskets (Rodrigues et al. 2022). Finally, many articles suggested policies that better support more local food production. This included support of informal food and seed networks and agrobiodiversity in South America, improve smallholder poultry production systems in Nigeria through improved local breeds, and improving food security in Iran through improved seeds, agroecological training courses, and site-specific solutions for small-scale farmers struggling with drought and salinity problems (Bamidele and Amole 2021; Rad et al. 2021; Zimmerer and de Haan 2020).

Lessons for niche engagement post-disaster

Within the context of applying the MLP and thinking about how niches can contribute to longer term progressive change in our agrifood systems, below is a summary of the relevant resources, policies, and practices that cut-across studies of agrifood systems and disasters. Keeping in mind there are a wide range of agrifood niches, the relevance of these resources, policies, and practices will vary, but one thing most niches will have in common is the innovation offered will likely be social and organizational, not merely technical. This is because many of the “technologies” advanced by agrifood niches are older, well-tested, and/or low-tech (e.g., organics, agroecology, etc.; Bui et al. 2016). Certainly, there can be higher-tech solutions, but even these will likely involve social and organizational innovations if they are to ensure food security.

Resources

Areas where niches may already be engaged but could further expand their efforts after a disaster include food provisioning, farm supplies, education, and communication of available resources among affected communities. In the case of food provisioning, this can come in many forms, but food boxes are commonly mentioned to ensure people have a safe and accessible supply of food immediately following a disaster. Similarly, supplying producers with resources (e.g., seeds, animals) to quickly recover and resume production post-disasters is another area where some niches may be well positioned to effectively engage. Finally, niches may discover opportunities for education, such as focusing on alternative forms of farming that are more resilient (e.g., agroecology, flood recession farming). There may also be expanded opportunities for communication from niches. Communicating to the broader public about safe food or food preservation techniques, and the locations of available foods, as well as making the public aware of ways they can support local production systems are a few examples of themes that emerged from the agrifood disaster literature that fit well with niche activities.

Policies

Within MLP, niches are protected spaces where radical innovation can be created and nurtured in the periphery of existing systems (Geels 2019). However, a traditional challenge for niches is how to obtain resources to support growth and diffusion, without being coopted by the regime the niche seeks to change. In other words, how can niches stretch-and-transform the regime rather than simply fit-and-conform within it (Walton 2024; Smith and Raven 2012). The results of our literature review indicate that this tension is especially relevant for niches after a disaster. If niches remain completely isolated from government actors (especially at the local or regional level) they will miss opportunities to be involved in disaster response and recovery.

On the one hand, there is clearly a role for government in disaster preparedness and response. Beyond providing large-scale resources in a timely fashion, in the case of famine, government intervention is critical to preventing disaster. On the other hand, disaster response should not be solely in the hands of government, especially at the highest levels. Within the MLP approach to thinking about disasters, there is a need to be nimble and allow innovation to occur, and yet too often governments do not allow for such innovation (Broadhurst and Gray 2022; Becker and Reusser 2016). While not using the MLP framework, Smith and Lawrence (2018) similarly found that during a major flooding event in Australia a retailer-government coalition emerged that excluded other organizations already working in the area of food security. Such patterns suggest that niches, while generally independent of governments, could be better positioned to engage in post disaster agrifood change if they have some pre-existing connections with local and regional governments.

Bui et al. (2016) study of four agrifood niches can provide some guidance on this topic. Through their analysis of four diverse case studies, the authors found all the cases began as grassroot movements that contained a limited range of actors, usually of the same social group.Footnote 4 Only when the groups moved to phase 2 (see Fig. 1) and began to widen their group to enroll new actors to assist in achieving broader goals and a shared vision, did these groups become niches and gain stability. In their transition between phase 2 and phase 3, these niches successfully created an alternative model, linked with local authorities, and impacted local practices, strategies and alliances of some regime actors at the local level (Bui et al. 2016, 98). Similarly, Geels (2019, 197) calls for more work to be done on open and inclusive governance style, which would mean policymakers involving citizens, NGOs, and wider publics to “unleash bottom-up grassroots and community initiatives.” Niches being engaged with local governments in response to disasters present an opportunity to ensure long-term transformation of the food system, but such linkages raise concerns that this may dilute the radical potential of niches.

Practices

In conjunction with the potential for niche engagement working with local governments on disaster response, supply chains, especially short chains, are an area that many agrifood niches are already engaged. Within agrifood disaster literature, there is the idea of building more robust local agrifood chains; ensuring food safety and effectively communicating about food safety to restore trade; and re-establishing trade to facilitate lower prices for goods, thereby ensuring food security and livelihoods. An often-neglected dimension of agrifood systems is the middle, including transporters and retailers (Béné et al. 2024). Thus, sociotechnical niches that engage with the agrifood supply chains, especially the often-overlooked components that facilitate bringing food from the farm to the plate, increase their likelihood of influence during disaster recovery.

Another area of practice relevant to agrifood niches are the ways in which niches can help to cultivate social connections prior to a disaster and can work to integrate vulnerable populations into the cultivation of these connections. As mentioned under policies, one drawback of some grassroots movements is their homogeneity (i.e., race, class, gender, sexuality), but Bui et al. (2016) argue only once these movements have expanded to enroll new and diverse actors with broad goals and shared vision, would they be considered a niche. Several studies in the literature review focused on community gardens after hurricanes as facilitating recovery and social inclusion (Chan et al. 2015; Kato et al. 2014), yet within the MLP framework community gardens would need to be more intentional about cultivating broader support to ensure such initiatives gain stability commonly associated with phase 2. Another, less explored possibility, would be to consider ways in which local governments could facilitate or support niche engagement with local populations in disaster planning and preparedness. The incorporation of local populations in such efforts was identified across several types of disasters (i.e., hurricanes, nuclear, COVID-19) and could help to further build social capital prior to a disaster.

Vulnerable populations

Finally, niches interested in more sustainable and just food systems, should consider vulnerable populations, as vulnerable populations are ubiquitous within agrifood disasters and the broader disaster studies literature (Tierney 2019). But there is a danger in homogenizing vulnerability. In their comprehensive review of poverty and disasters Hallegatte et al. (2020, 240) are clear that “poor people suffer disproportionately from natural disasters.” However, they explain that the relationship between poverty and disaster exposure depends on the hazard, local geography, and institutions among other factors. For example, remote rural producers are vulnerable to losing their primary source of food and income in large-scale disasters, but in certain circumstances, the reliance on agriculture for income can afford poor households a faster recovery compared to their urban counterparts if they are able to resume production quickly (Hallegatte et al. 2020). Other types of vulnerability also demand nuance. For example, while gender inequality has often been attributed to women disproportionately being negatively impacted by disasters, including experiencing increased physical and sexual abuse (Enarson 2012; Rao 2020), this depends upon a variety of factors such as cultural norms, education levels, and economic status. In summary, reducing vulnerability before a disaster is the best solution to reducing vulnerability in disaster recovery (Hallegatte et al. 2020). Agrifood niches need to either directly or indirectly (i.e., coordinating with other non-agrifood niches) engage vulnerable populations in agrifood systems.

Conclusion

Agrifood niches contain a repertoire of knowledge and practices that can be valuable during disaster response. Yet, to ensure niches are not bypassed during recovery, niches need to have pre-existing connections to local and regional governments, which does raise concerns about cooptation of the radical potential of niches. Moreover, as mentioned in this review of existing disaster literature, there are unique concerns surrounding authoritarian regimes and disaster response. With an increasing number of authoritarian regimes, it may be beneficial for more studies to analyze agrifood niches outside of Western liberal democratic settings (Rut and Davies 2018). There are also other avenues for future research, including expanding the types of disasters (i.e., deforestation, earthquakes) analyzed, and additional case studies of agrifood movements that move to niche status and remain relevant in response to disasters.

Better understanding the types of resources, policies and practices that can assist niches in responding to disasters and catastrophes, can facilitate regime transformation. However, to ensure the transformation is sustainable and just, agrifood niches need to engage with vulnerable populations, either directly or indirectly, prior to disasters or catastrophes. In summary, disasters are a disruptive force, which if disaster response is strategically engaged can offer opportunities for progressive change in the agrifood system.

Notes

Sociotechnical systems are used by science and technology studies (STS) scholars to refer to complex systems of “social and technical components intertwined in mutually influencing relationships” (Johnson and Wetmore 2008, 574).

Agrifood scholars will recognize a similar turn occurred in the “new rural sociology” in the late 1970s and early 1980s (Buttel, 2001).

With the exception of COVID-19, a comparison was made between the results of specific disaster searches in Google Scholar and Scopus, and it was determined that Google Scholar was preferred, as Scopus tended to generate results that were less accurate to specific types of disasters.

Geels (2019, 193) also notes this is a challenge of grassroots movements for gaining wider appeal, as “despite their inclusive ethos,” they are often not very diverse.

References

Adhikari, J., J. Timsina, S.R. Khadka, Y. Ghale, and H. Ojha. 2021. COVID-19 impacts on agriculture and food systems in Nepal: Implications for SDGs. Agricultural Systems 186: 102990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102990.

Ahmad, D., and M. Afzal. 2021. Flood hazards, human displacement and food insecurity in rural riverine areas of Punjab, Pakistan: Policy implications. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28: 10125–10139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11430-7.

Ajaero, C.K. 2017. A gender perspective on the impact of flood on the food security of households in rural communities of Anambra state, Nigeria. Food Security 9 (4): 685–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-017-0695-x.

Amjath-Babu, T.S., T.J. Krupnik, S.H. Thilsted, and A.J. McDonald. 2020. Key indicators for monitoring food system disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights from Bangladesh towards effective response. Food Security 12 (4): 761–768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01083-2.

Ashraf, S., M. Iftikhar, B. Shahbaz, G.A. Khan, and M. Luqman. 2013. Impacts of flood on livelihoods and food security of rural communities: a case study of southern Punjab, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences 50 (4): 751.

Azadi, H., S. Burkart, S.M. Moghaddam, H. Mahmoudi, K. Janečková, P. Sklenička, P. Ho, D. Teklemariam, and H. Nadiri. 2022. Famine in the Horn of Africa: Understanding institutional arrangements in land tenure systems. Food Reviews International 38 (sup1): 829–845. https://doi.org/10.1080/87559129.2021.1888974.

Bacon, C.M., W.A. Sundstrom, I.T. Stewart, and D. Beezer. 2017. Vulnerability to cumulative hazards: Coping with the coffee leaf rust outbreak, drought, and food insecurity in Nicaragua. World Development 93: 136–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.12.025.

Bai, Y., and J.K. Kung. 2014. The shaping of an institutional choice: Weather shocks, the Great Leap Famine, and agricultural decollectivization in China. Explorations in Economic History 54: 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2014.06.001.

Bain, C., E. Ransom, and M.R. Worosz. 2010. Constructing credibility: Using technoscience to legitimate strategies in agrifood governance. Journal of Rural Social Sciences 25 (3): 9.

Baltimore Food Policy Initiative. 2020. COVID-19 Food Insecurity Response: Grocery and Produce Box Distribution Summary. Baltimore: City of Baltimore.

Bamidele, O., and T.A. Amole. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 on smallholder poultry farmers in Nigeria. Sustainability 13 (20): 11475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011475.

Bang, H., L. Miles, and R. Gordon. 2018. Enhancing local livelihoods resilience and food security in the face of frequent flooding in Africa: A disaster management perspective. Journal of African Studies and Development 10 (7): 85–100. https://doi.org/10.5897/JASD2018.0510.

Baro, M., and T.F. Deubel. 2006. Persistent hunger: Perspectives on vulnerability, famine, and food security in sub-Saharan Africa. Annual Review of Anthropology 35: 521–538. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123224.

Becker, S.L., and D.E. Reusser. 2016. Disasters as opportunities for social change: Using the multi-level perspective to consider the barriers to disaster-related transitions. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 18: 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.05.005.

Belyakov, Alexander. 2015. From Chernobyl to Fukushima: An interdisciplinary framework for managing and communicating food security risks after nuclear plant accidents. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 5 (3): 404–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-015-0284-2.

Béné, C., E.M. d’Hôtel, R. Pelloquin, O. Badaoui, F. Garba, and J.W. Sankima. 2024. Resilience—and collapse—of local food systems in conflict affected areas; reflections from Burkina Faso. World Development 176: 106521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106521.

Bernstein, T.P. 1984. Stalinism, famine, and Chinese peasants: Grain procurements during the great leap forward. Theory and Society 13: 339–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00213230.

Biehl, E., Buzogany, S., Baja, K., and Neff, R. A. 2018. Planning for a resilient urban food system: A case study from Baltimore City, Maryland. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 8(B): 39–53

Bolin, B., and L.C. Kurtz. 2018. Race, class, ethnicity, and disaster vulnerability. Handbook of disaster research. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63254-4_10.

Boori, M.S., K. Choudhary, M. Evers, and R. Paringer. 2017. A review of food security and flood risk dynamics in central dry zone area of Myanmar. Procedia Engineering 201: 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.09.600.

Brass, Paul R. 1986. The political uses of crisis: The Bihar famine of 1966–1967. The Journal of Asian Studies 45 (2): 245–267. https://doi.org/10.2307/2055843.

Broadhurst, K., and N. Gray. 2022. Understanding resilient places: Multi-level governance in times of crisis. Local Economy 37 (1–2): 84–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/02690942221100101.

Bui, S., A. Cardona, C. Lamine, and M. Cerf. 2016. Sustainability transitions: Insights on processes of niche-regime interaction and regime reconfiguration in agri-food systems. Journal of Rural Studies 48: 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.10.003.

Bui, S., I. Costa, O. De Schutter, T. Dedeurwaerdere, M. Hudon, and M. Feyereisen. 2019. Systemic ethics and inclusive governance: Two key prerequisites for sustainability transitions of agri-food systems. Agriculture and Human Values 36 (2): 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-019-09917-2.

Buttel, F.H. 2001. Some reflections on late twentieth century Agrarian political economy. Sociologia Ruralis 41 (2): 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9523.00176.

Ceballos, F., S. Kannan, and B. Kramer. 2020. Impacts of a national lockdown on smallholder farmers’ income and food security: Empirical evidence from two states in India. World Development 136: 105069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105069.

Chan, J., B. DuBois, and K.G. Tidball. 2015. Refuges of local resilience: Community gardens in post-sandy New York City. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 14 (3): 625–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2015.06.005.

Chang, T., and D. Takahashi. 2021. Taiwanese voter surveys on restrictions of food imports from five prefectures near fukushima, japan: An empirical analysis. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 10 (2): 280–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2021.1885111.

Chang, G.H., and G.J. Wen. 1997. Communal dining and the Chinese famine of 1958–1961. Economic Development and Cultural Change 46 (1): 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1086/452319.

Chimweta, M., I.W. Nyakudya, L. Jimu, L. Musemwa, A.B. Mashingaidze, J.P. Musara, and K. Kashe. 2022. Flood-recession cropping in the mid-Zambezi Valley: A neglected farming system with potential to improve household food security and income. The Geographical Journal 188 (1): 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12418.

Clay, L.A., M.A. Papas, K. Gill, and D.M. Abramson. 2018. Application of a theoretical model toward understanding continued food insecurity post Hurricane Katrina. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 12 (1): 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2017.35.

Corbett, J. 1983. Nuclear war and crisis relocation planning: A view from the grassroots. Impact Assessment 2 (4): 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/07349165.1983.9725997.

Corbett, J. 1988. Famine and household coping strategies. World Development 16 (9): 1099–1112. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(88)90112-X.

Dalrymple, D.G. 1964. The Soviet famine of 1932–1934: ‘Food is a weapon’—Maxim Litvinov, 1921. Europe-Asia Studies 15 (3): 250–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136408410364.

Davidson, D.J., K.E. Jones, and J.R. Parkins. 2016. Food safety risks, disruptive events and alternative beef production: A case study of agricultural transition in Alberta. Agriculture and Human Values 33 (2): 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9609-8.

de Loïc, L., T.R. Loïc, F. Leone, and D. Gilbert. 2018. Sustainable livelihoods and effectiveness of disaster responses: A case study of tropical cyclone Pam in Vanuatu. Natural Hazards 91: 1203–1221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3174-6.

Del Ninno, C., P.A. Dorosh, and L.C. Smith. 2003. Public policy, markets and household coping strategies in Bangladesh: Avoiding a food security crisis following the 1998 floods. World Development 31 (7): 1221–1238. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00071-8.

Devereux, S. 2002. The Malawi famine of 2002. IDS Bulletin 33 (4): 70–78.

Dorosh, P., S.J. Malik, and M. Krausova. 2010. Rehabilitating agriculture and promoting food security after the 2010 Pakistan floods: Insights from the south Asian experience. The Pakistan Development Review 49: 167–192.

Ellman, M. 2007. Stalin and the Soviet famine of 1932–33 revisited. Europe-Asia Studies 59 (4): 663–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668130701291899.

Enarson, E.P. 2012. Women confronting natural disaster: From vulnerability to resilience. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers Boulder, CO.

Enarson, E., A. Fothergill, and L. Peek. 2018. Gender and disaster Foundations and new directions for research and practice. In Handbook of disaster research, ed. H. Rodríguez, W. Donner, and J.E. Trainor, 205–223. Cham: Springer.

Escobar, M., A.D. Mendez, M.R. Encinas, S. Villagomez, and J.M. Wojcicki. 2021. High food insecurity in Latinx families and associated COVID-19 infection in the Greater Bay Area, California. BMC Nutrition 7 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-021-00419-1.

Fitzpatrick, K.M., D.E. Willis, M.L. Spialek, and E. English. 2020. Food insecurity in the post-Hurricane Harvey setting: Risks and resources in the midst of uncertainty. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (22): 8424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228424.

Frankenberg, E., T. Gillespie, S. Preston, B. Sikoki, and D. Thomas. 2011. Mortality, the family and the Indian Ocean tsunami. The Economic Journal 121 (554): F162–F182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2011.02446.x.

Fussell, E., S.R. Curran, M.D. Dunbar, M.A. Babb, L. Thompson, and J. Meijer-Irons. 2017. Weather-related hazards and population change: A study of hurricanes and tropical storms in the United States, 1980–2012. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 669 (1): 146–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716216682942.

Geels, F.W. 2004. Understanding system innovations: a critical literature review and a conceptual synthesis. System Innovation and the Transition to Sustainability: Theory, Evidence and Policy. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781845423421.

Geels, F.W. 2019. Socio-technical transitions to sustainability: A review of criticisms and elaborations of the multi-level perspective. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 39: 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2019.06.009.

Glantz, M.H., and J.R. Ivan. 2018. Improvisation in the time of disaster. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. 60 (5): 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2018.1495496.

Gooch, E. 2017. Estimating the long-term impact of the Great Chinese Famine (1959–61) on Modern China. World Development 89: 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.08.006.

Goodkind, D., and L. West. 2001. The North Korean famine and its demographic impact. Population and Development Review 27 (2): 219–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2001.00219.x.

Grillo-Núñez, J., T. Mendo, R. Gozzer-Wuest, and J. Mendo. 2021. Impacts of COVID-19 on the value chain of the hake small scale fishery in northern Peru. Marine Policy 134: 104808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104808.

Gupta, D., H. Fischer, S. Shrestha, S.S. Ali, A. Chhatre, K. Devkota, F. Fleischman, and P. Rana. 2021. Dark and bright spots in the shadow of the pandemic: Rural livelihoods, social vulnerability, and local governance in India and Nepal. World Development 141: 105370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105370.

Hallegatte, S., A. Vogt-Schilb, J. Rozenberg, M. Bangalore, and C. Beaudet. 2020. From poverty to disaster and back: A review of the literature. Economics of Disasters and Climate Change 4 (1): 223–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-020-00060-5.

Haque, A., and S. Jahan. 2016. Regional impact of cyclone sidr in Bangladesh: A multi-sector analysis. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 7: 312–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-016-0100-y.

Harvey, C.A., M. Milagro Saborio-Rodríguez, R. Martinez-Rodríguez, B. Viguera, A. Chain-Guadarrama, R. Vignola, and F. Alpizar. 2018. Climate change impacts and adaptation among smallholder farmers in Central America. Agriculture & Food Security 7 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-018-0209-x.

Helfand, I. 2013. Nuclear famine: Two billion people at risk. International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War 2.

Hinrichs, C.C. 2014. Transitions to sustainability: A change in thinking about food systems change? Agriculture and Human Values 31 (1): 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-014-9479-5.

Hoteit, M., Y. Al-Atat, H. Joumaa, S. El Ghali, R. Mansour, R. Mhanna, F. Sayyed-Ahmad, P. Salameh, and A. Al-Jawaldeh. 2021. Exploring the impact of crises on food security in lebanon: Results from a national cross-sectional study. Sustainability 13 (16): 8753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168753.

Hussain, A., G. Rasul, B. Mahapatra, and S. Tuladhar. 2016. Household food security in the face of climate change in the Hindu-Kush Himalayan region. Food Security 8: 921–937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-016-0607-5.

Iese, V., E. Holland, M. Wairiu, R. Havea, S. Patolo, M. Nishi, R. Taniela Hoponoa, M. Bourke, A. Dean, and L. Waqainabete. 2018. Facing food security risks: The rise and rise of the sweet potato in the Pacific Islands. Global Food Security 18: 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2018.07.004.

Jaacks, L.M., D. Veluguri, R. Serupally, A. Roy, P. Prabhakaran, and G.V. Ramanjaneyulu. 2021. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on agricultural production, livelihoods, and food security in India: Baseline results of a phone survey. Food Security 13 (5): 1323–1339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01164-w.

Johnson, D.G., and J.M. Wetmore. 2008. 23 STS and Ethics: Implications for engineering ethics. In The handbook of science and technology studies, ed. E.J. Hackett, O. Amsterdamska, M. Lynch, and J. Wajcman, 567. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Kaptan, G., A.R.H. Fischer, and L.J. Frewer. 2018. Extrapolating understanding of food risk perceptions to emerging food safety cases. Journal of Risk Research 21 (8): 996–1018. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2017.1281330.

Kato, Y., C. Passidomo, and D. Harvey. 2014. Political gardening in a post-disaster city: Lessons from New Orleans. Urban Studies 51 (9): 1833–1849. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013504143.

Kendra, J., and T. Wachtendorf. 2007. Improvisation, creativity, and the art of emergency management. In Understanding and Responding to Terrorism, ed. H. Durmaz, 324–335. Amsterdam, Netherlands: IOS Press.

Kerr, W.A., B.D. Boutin, A.S. Kwaczek, and S. Mooney. 1992. Nuclear accidents, impact assessment, and disaster administration: Post-chernobyl insights for agriculture in Canada. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 12 (4): 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/0195-9255(92)90028-V.

Kershaw, I. 1973. The great famine and agrarian crisis in England 1315–1322. Past & Present 59: 3–50.

Klinenberg, E., M. Araos, and L. Koslov. 2020. Sociology and the climate crisis. Annual Review of Sociology 46 (1): 649–669. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-121919-054750.

Köhler, J., F.W. Geels, F. Kern, J. Markard, E. Onsongo, A. Wieczorek, F. Alkemade, F. Avelino, A. Bergek, and F. Boons. 2019. An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 31: 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004.

Koyama, R., and H. Ishii. 2014. The systemization of radioactivity inspection for food products and steps to counteract reputational damage in Fukushima, Japan. Journal of Commerce, Economics and Economic History 82 (4): 15–22.

Kulkarni, S., S. Bhat, P. Harshe, and S. Satpute. 2022. Locked out of livelihoods: impact of COVID-19 on single women farmers in Maharashtra, India. Economia Politica. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-021-00240-w.

Lawhon, M., and J. Murphy. 2011. Socio-technical regimes and sustainability transitions: Insights from political ecology. Progress in Human Geography 36 (3): 354–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511427960.

Lee, D., S. Seo, M.K. Song, H.K. Lee, S. Park, and Y.W. Jin. 2017. Factors associated with the risk perception and purchase decisions of Fukushima-related food in South Korea. PLoS ONE 12 (11): e0187655. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187655.

Li, H.C., S.P. Wei, C.T. Cheng, J.J. Liou, Y.M. Chen, and K.C. Yeh. 2015. Applying risk analysis to the disaster impact of extreme typhoon events under climate change. Journal of Disaster Research 10 (3): 513–526.

Lioutas, E.D., and C. Charatsari. 2021. Enhancing the ability of agriculture to cope with major crises or disasters: What the experience of COVID-19 teaches us. Agricultural Systems 187: 103023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.103023.

Loebach, P. 2019. Livelihoods, precarity, and disaster vulnerability: Nicaragua and Hurricane Mitch. Disasters 43 (4): 727–751. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12402.

Love, D.C., E.H. Allison, F. Asche, B. Belton, R.S. Cottrell, H.E. Froehlich, J.A. Gephart, C.C. Hicks, D.C. Little, and E.M. Nussbaumer. 2021. Emerging COVID-19 impacts, responses, and lessons for building resilience in the seafood system. Global Food Security 28: 100494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100494.

Lucas, H.S. 1930. The great European famine of 1315, 1316, and 1317. Speculum 5 (4): 343–377. https://doi.org/10.2307/2848143.

Mabon, L., and M. Kawabe. 2018. Engagement on risk and uncertainty–lessons from coastal regions of Fukushima Prefecture, Japan after the 2011 nuclear disaster? Journal of Risk Research 21 (11): 1297–1312. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2016.1200658.

Mamdani, M. 1982. Karamoja: Colonial roots of famine in North-East Uganda. Review of African Political Economy 9 (25): 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056248208703517.

Matthewman, S., and S. Uekusa. 2021. Theorizing disaster communitas. Theory and Society 50 (6): 965–984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-021-09442-4.

Maxwell, D., N. Majid, G. Adan, K. Abdirahman, and J.J. Kim. 2016. Facing famine: Somali experiences in the famine of 2011. Food Policy 65: 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.11.001.

McBurney, M., L.A. Tuaza, C. Ayol, and C.A. Johnson. 2021. Land and livelihood in the age of COVID-19: Implications for indigenous food producers in Ecuador. Journal of Agrarian Change 21 (3): 620–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12417.

McGreevy, S.R., C.D.D. Rupprecht, D. Niles, A. Wiek, M. Carolan, G. Kallis, K. Kantamaturapoj, A. Mangnus, P. Jehlička, O. Taherzadeh, M. Sahakian, I. Chabay, A. Colby, J.L. Vivero-Pol, R. Chaudhuri, M. Spiegelberg, M. Kobayashi, B. Balázs, K. Tsuchiya, C. Nicholls, K. Tanaka, J. Vervoort, M. Akitsu, H. Mallee, K. Ota, R. Shinkai, A. Khadse, N. Tamura, K. Abe, Ml. Altieri, Y. Sato, and M. Tachikawa. 2022. Sustainable agrifood systems for a post-growth world. Nature Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00933-5.

Miller, D.S. 2016. Public trust in the aftermath of natural and na-technological disasters: Hurricane Katrina and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear incident. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 36 (5/6): 410–431.

Mokyr, J., and C.Ó. Gráda. 2002. What do people die of during famines: The Great Irish Famine in comparative perspective. European Review of Economic History 6 (3): 339–363. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1361491602000163.

Mor, R.S., P.P. Srivastava, R. Jain, S. Varshney, and V. Goyal. 2020. Managing food supply chains post COVID-19: A perspective. International Journal of Supply and Operations Management 7 (3): 295–298. https://doi.org/10.22034/IJSOM.2020.3.7.

Morgan, K., T. Marsden, and J. Murdoch. 2006. Worlds of food: Place, power, and provenance in the food chain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nagel, J. 2012. Intersecting identities and global climate change. Identities 19 (4): 467–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2012.710550.

Niles, M.T., B.F. Emery, A.J. Reagan, P.S. Dodds, and C.M. Danforth. 2019. Social media usage patterns during natural hazards. PLoS ONE 14 (2): e0210484. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210484.

Niles, M.T., K.B. Wirkkala, E.H. Belarmino, and F. Bertmann. 2021. Home food procurement impacts food security and diet quality during COVID-19. BMC Public Health 21 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10960-0.

Nordine, K, and Zeuli, K. 2022. Tactics to try for emergency food planning: Building knowledge and momentum for emergency food planning. The Food Foundation. https://foodfoundation.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-02/FOOD%20CITIES%202022%20Tactics%20to%20Try_FULL%20DOC.pdf.

Noy, I., and W. duPont IV. 2018. The long-term consequences of disasters: What do we know, and what we still don’t. International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics 12 (4): 325–354. https://doi.org/10.1561/101.00000104.

Okazaki, S. 1986. The great Persian famine of 1870–71. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 49 (1): 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0041977X00042609.

Paek, H., and T. Hove. 2019. Effective strategies for responding to rumors about risks: The case of radiation-contaminated food in South Korea. Public Relations Review 45 (3): 101762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2019.02.006.

Paul, S.K., and J.K. Routray. 2011. Household response to cyclone and induced surge in coastal Bangladesh: Coping strategies and explanatory variables. Natural Hazards 57: 477–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-010-9631-5.

Paul, S.K., B.K. Paul, and J.K. Routray. 2012. Post-cyclone Sidr nutritional status of women and children in coastal Bangladesh: An empirical study. Natural Hazards 64: 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-012-0223-4.

Pianciola, N. 2004. Famine in the steppe: The collectivization of agriculture and the Kazak herdsmen 1928–1934. Cahiers Du Monde Russe 45 (1–2): 137–192.

Pratiwi, E.P., E.L. Ari, F.N. Ramadhani, and D. Legono. 2020. The impacts of flood and drought on food security in central Java. Journal of the Civil Engineering Forum 6 (1): 69. https://doi.org/10.22146/jcef.51782.

Pu, M., and Y. Zhong. 2020. Rising concerns over agricultural production as COVID-19 spreads: Lessons from China. Global Food Security 26: 100409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100409.

Rad, A.K., R.R. Shamshiri, H. Azarm, S.K. Balasundram, and M. Sultan. 2021. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on food security and agriculture in Iran: A survey. Sustainability 13 (18): 10103. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810103.

Rahman, M. S. 2013. Climate change, disaster and gender vulnerability: A study on two divisions of Bangladesh. American Journal of Human Ecology 2(2): 72–82. https://doi.org/10.11634/216796221504315.

Rañola, R.F., M.A. Cuesta, B. Razafindrabe, and R. Kada. 2015. Building disaster resilience to address household food security: The case of Sta. rosa-silang subwatershed. Journal of Economics, Management & Agricultural Development 1 (2): 53–68. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.309267.

Ransom, E., and H. Raymond. 2024. Disaster and catastrophes in agrifood studies. In Agrifood transitions in the anthropocene: Challenges, contested knowledge, and the need for change, ed. D.H. Constance and A.M. Loconto, 200–226. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ransom, E., M. Hatanaka, J. Konefal, and A.M. Loconto. 2017. Science and Standards. In The Routledge handbook of the political economy of science, ed. D. Tyfield, R. Lave, S. Randalls, and C. Thorpe. London: Routledge.

Rao, S. 2020. A natural disaster and intimate partner violence: Evidence over time. Social Science & Medicine 247: 112804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112804.

Reed, C., W. Anderson, A. Kruczkiewicz, J. Nakamura, D. Gallo, R. Seager, and S.S. McDermid. 2022. The impact of flooding on food security across Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119 (43): e2119399119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2119399119.

Rehman, A., L. Jingdong, D. Yuneng, R. Khatoon, S.A. Wagan, and S.K. Nisar. 2016. Flood disaster in Pakistan and its impact on agriculture growth (a review). Environment and Development Economics 6 (23): 39–42.

Repucci, S., and A. Slipowitz. 2022. Freedom in the World 2022: The global expansion of auhtoriarian rule. Washington, D.C.: Freedom House.

Robock, A., and O.B. Toon. 2010. Local nuclear war, global suffering. Scientific American 302 (1): 74–81.

Rocheleau, D.E. 1991. Gender, ecology, and the science of survival: Stories and lessons from Kenya. Agriculture and Human Values 8: 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01579669.