Abstract

Across the European Union, the receipt of agricultural subsidisation is increasingly being predicated on the delivery of public goods. In the English context, in particular, these changes can be seen in the redirection of money to the new Environmental Land Management scheme. Such shifts reflect the changed expectations that society is placing on agriculture—from something that provides one good (food) to something that supplies many (food, access to green spaces, healthy rural environment, flood resilience, reduced greenhouse gas emissions). Whilst the reasons behind the changes are well documented, understanding how these shifts are being experienced by the managers expected to deliver on these new expectations is less well understood. Bourdieu’s social theory and the good farmer concept are used to attend to this blind spot, and to provide timely insight as the country progresses along its public goods subsidy transition. Evidence from 65 interviews with 40 different interviewees (25 of whom gave a repeat interview) show a general willingness towards the transition to a public goods model of subsidisation. The optimisation and efficiency that has historically characterised the productivist identity is colouring the way managers are approaching the delivery of public goods. Ideas of land sparing and land sharing (and the farming preference for the former over the latter) are used to help understand these new social and attitudinal realities. The policy implications of these findings are discussed, with reference to the new scheme’s ‘priority themes’.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Catalysed by the Brexit process, England is set to experience major shifts in the design of its agricultural subsidy system (Helm 2017). Of these, the changes to the provision of direct agricultural subsidisation, historically financed and delivered through Pillar One of the European Union’s (EU) Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), are amongst of the most significant. England’s Department for the Environment and Rural Affairs (Defra) have revealed the direction of travel for the country’s system of farm subsidies. Direct payments are to be tapered off over the 2021–2027 transition period, with the money being redirected to an ambitious agri-environment scheme (AES): Environmental Land Management (ELM). In describing these plans, Defra has availed of language that reveals the principles behind the changes. The scheme will “free up” (Defra 2018a, p. 7) funds from the current subsidy model in which payments are “skewed towards the largest landowners and are not linked to any specific public benefits” (Defra 2018a, p. 5).

These dynamics reveal the changing expectations that civic society is projecting onto the farming sector. Namely, as something whose worth is rooted exclusively in its capacity to produce food to something valued for its provision of recreational spaces for an increasingly urbanised population (Oueslati and Salanié 2011), a healthy rural environment (Kantelhardt 2006), reduced contribution to greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs; Westhoek et al. 2013) and the protection of cultural landscape features (Junge et al. 2011).

The idea of public goods can be used to help conceptualise these changes. Public goods are things that are non-excludable and non-rival (something that is available to all, irrelevant of who has accessed the supply of the good, or to what extent it has been accessed) (Cooper et al. 2009). The need to encourage behaviours that provides public goods arises because of the market failure to supply them autonomously (Jaffe et al. 2005). So, whilst the agricultural industry is being valued for its capacity to provide public goods (Arriaza et al. 2004; Zasada 2011), without appropriate intervention, land managers are unable or unwilling to supply them (Hodge 2000). The need is most clear in the context of agriculture’s biodiversity and GHG footprint (Buller and Morris 2004; Nelson et al. 2010; Willett et al. 2019). These anxieties and ambitions are manifest across ELMs scheme policy briefings (Defra 2020a), the UK Government’s 25 Year Environment Plan (Defra 2018b) and the Agriculture Bill and Environment Bill (see, for example, Houses of Parliament 2020).

By making the full receipt of direct payments contingent on minimum environmental standards, and by offering AESs that remunerate the voluntary adoption of environmental management practices, the public goods model is one that has already, in part, been operationalised (Dobbs and Pretty 2004; Meyer et al. 2014). The sorts of changes being made through the Brexit process can be seen as part of more long-standing shifts in agricultural policy design (Wilson 2001; Ward et al. 2008).

What is significant, though, is the speed and scale of the overhaul. As it stands, 61% of farm business income in England is derived from direct agricultural subsidisation (Defra 2018d), without which 42% of the country’s farms would not be profitable (Defra 2018c). Reliance on direct support varies across farm systems—with poultry, pig and horticultural units most profitable without support, and cereals, mixed and grazing units typically loss making without it (Defra 2018c). There are major worries around the viability of constituent farm businesses, and the sector as a whole (Hubbard et al. 2018), not least because of the modest adjustment period afforded to the country’s farmers (with CAP payments guaranteed only up until the end of 2022).

To contextualise the challenge of the transition in another way, uptake figures for targeted AES contracts are also instructive. By the end of 2018, just 1.6 m ha—18% of the country’s agricultural land—was being managed under a targeted AES scheme contract (National Statistics 2019). In contrast, Defra hopes that 82,500 land managers will be enrolled into ELMs by 2028 (NAO 2019)—around three quarters of the country’s farm holdings. Although it will be the only support available (compared to previous voluntary schemes that have sat alongside direct Pillar One support), ELMs must be able to attract significantly more of the country’s farmers if it is to deliver on the scale of public goods being asked of it.

These dynamics are introducing a new urgency to the study of how farming attitudes and identities interface with the delivery of non-agricultural goods. What are the sector’s attitudes towards the provision of public goods, and how might these attitudes shift as other forms of support are removed? Insofar as they are going to be the major providers of these varied public goods, farmers’ attitudes towards their provision will be an important determinant in the success of the new-look breed of agricultural regime (Howley et al. 2014).

The aim of the paper is to add a timely insight into these questions, and to look into the dangers and opportunities manifest in the country’s agricultural policy transition. The paper is adding to the nascent literature dedicated to understanding how the public goods model is being experienced by the land managers at the front line of the agricultural policy transition. It is looking to compliment the largely quantitative survey work done in this area (Howley et al. 2014; Kvakkestad et al. 2015) with research predicated on a qualitative in-depth interview methodology and the ‘good farmer’ concept. In doing so, the paper is also able to contribute to ongoing sociological inquiry into the identities and attitudes represented in the farming sector. The paper uses England as a case study, although given the political and social factors common across the devolved nations, the findings have broader UK-relevance. Similarly, as the EU reflects on the potential merits of prioritising public goods in its own subsidy system (Czyzewski and Stepien 2018; EPRS 2018; Vilke and Gedminaite-Raudone 2018), the paper is able to speak to broader EU dynamics.

Conceptualising the ‘good farmer’ and public goods subsidisation

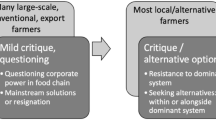

Whilst there is willingness amongst the general public to pay land managers for the provision of public goods (Kallas et al. 2007), the attitudes of the farmers towards the landscapes associated with their provision have historically been less favourable (Lobley and Potter 2004; Howley et al. 2012). There is a lag between the policy changes that are re-orientating agricultural subsidies from agricultural production to the provision of public goods, and the farmers’ internalisation of the identities those policy changes imply (Gorton et al. 2008). This is especially pertinent for the supply of environmental goods and the un-farmed appearances with which they are associated (Burton 2004).

The body of research revolving around the ‘good farmer’ concept is well placed to shed light on how farming identities interface with the prospect of engaging in public goods-orientated subsidisation. The concept reveals the farming styles that are held in high esteem by agricultural community, and the varied motivational factors that influence practice. The behaviours associated with the good farmer are not necessarily those that deliver the highest economic returns, but can be about the meeting of other existential, stylistic or moral goals (Silvasti 2003). Whilst some behaviour may be amply remunerated (say through subsidisation), if that practice, or if the landscape that practice creates, is in conflict with other objectives, there will be a resistance towards its adoption (Burton et al. 2008).

Earlier papers using the concept revealed an incompatibility between the landscape preferences of the farming community and the management practices promoted through AES schemes (Burton 2004). Farmers’ productivist ideals of high yields and intensification were antithetical to the removal of land from production, and the adoption of less intensive management practices (Burton 2004). The lack of skill and expertise associated with delivering the scheme options, combined with their high visibility also meant the schemes were experienced as lost opportunities to demonstrate their farming competence, and so represented a culturally unattractive prospect (Burton et al. 2008; Burton and Paragahawewa 2011).

Through changing conditions in agricultural economics and widening awareness around the environmental issues associated with intensive agriculture, that cultural resistance has abated (Sutherland and Darnhofer 2012). The price premiums associated with organic produce, for example, have facilitated an increased respect for those pursuing an organic model as a means of improving a farm’s economic viability (Sutherland 2013). The same changes have been experienced with regards to participation in an AES. Due to the economic benefits a scheme contract can secure, and due to the growing recognition of the skill required to deliver the constituent management practices, participation in an AES has become a fruitful opportunity to attract the respect of farming peers (Riley 2016). In this social and economic setting, environmental negligence rather than environmental proactivity has become associated with a loss of prestige (Cusworth 2020).

Such research is predicated on the sense that a given manager’s farming decisions are being scrutinised by other members of their community (Seabrook and Higgins 1988; Moran et al. 2013). Such social evaluation is as an important feature in the suite of motivational factors that influences a given land manager’s decision-making process (Kuhfuss et al. 2016). To help capture this socialised aspect of the farmers’ decision-making processes, most of the work in the good farmer literature is carried out with the theoretical underpinning of Bourdieu’s social theory.

Bourdieu explains how individuals, who occupy space in a given ‘field’, look to achieve favourable social standing through the reproduction of symbolic capital (Bourdieu 1986; Hilgers and Mangez 2015). Symbolic capital is itself generated through possession of three other forms of capital: economic, social and cultural. Economic capital is the type typically and most readily understood as something with motivational significance. It refers to things of direct financial value (money, shares, a high wage). Social capital relates to the network of social contacts in which an individual operates. The scale of social capital reproduced through one’s membership to a group is calibrated to the sum of capitals that the other group members can themselves lay claim. Participation in a rich or culturally powerful group will reproduce more social capital, therefore, than membership in a group with less economic or cultural influence. Cultural capital is broken down further into three subcategories—embodied, objectivised and institutionalised. Embodied cultural capital relates to bodily dispositions and habits; objectivised cultural capital to physical artefacts; and institutionalised cultural capital to awards and qualifications (Bourdieu 1986). Using Bourdieu’s theory can, in this way, help understand the full range of economic and non-economic capitals that shape practice (Moore 2008).

Bourdieu leans on the metaphor of the ‘rules of the game’ to capture the social code that determines which behaviours or artefacts are respected, and how different capitals are reproduced (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992; Thomson 2008). According to those rules, certain skills, practices, artefacts or institutions are considered legitimate, and will be those best able to reproduce the different capitals. The amount of capital to which an individual can lay claim determines the position they occupy in a field’s hierarchy. The field is, thus, the arena in which individuals struggle to occupy favourable social standing (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992).

An individual’s habitus is central to the internalisation and navigation of these rules (Bourdieu 1983). The habitus is the sum of an individual’s behaviours, experiences, outlooks, beliefs and dispositions. The habitus is defined as “structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures” (Bourdieu 1990, p. 53). It is structured insofar as it is the thing subconsciously shaped by an individual’s life experiences, education, and exposure to a field’s rules and conditions; and it is something predisposed to act as structuring structure insofar as it is the thing that allows for an individual’s agential participation in the world, and as something that allows for an individual to creatively and autonomously interact with the field’s constituent members, conditions and rules (Wacquant 1989). The habitus is the thing upon which one’s experiences are impressed, as well as the lens through which one processes and analyses a field’s rules and the behaviour of other field members (Maton 2008). Forged through one’s experience of the world, and through one’s internalisation of the field’s rules, it is the key to an individual’s attempt to successfully strategise their way through the field and to reproduce capital. It also the tool an individual uses to evaluate the performance of the other members of the field with regards to the field’s rules and the social position they occupy (Bourdieu 1977; Wacquant 1989).

The rules of the game change in response to new attitudes, knowledges and conditions prominent in a field. This can be seen in the context of the agricultural field, described above. There has been a historical prioritisation of the productivist goals of productivity and intensification, and the symbols best able to secure cultural capital were those that pertained to their attainment—straight ploughing lines, well-kept machinery, neat hedgerows (Burton 2004, 2012). More recently, the farmers adopting organic practices or participating in an AES revealed themselves to be the ones creatively responding to the policy, economic and social landscape that is increasingly favouring the delivery of more diverse farming objectives (Sutherland and Darnhofer 2012; Riley 2016). Such practices have achieved a new legitimacy and recognition in the rules of the game, and cultural capital can, accordingly, be reproduced through their adoption.

Bourdieu’s conceptualisation of the habitus has been central to understanding how these changes work. The habitus subconsciously mutates itself around the field’s conditions and rules—even when they are in flux (Bourdieu 1983; Wacquant 2011). An individual can, in periods of change, creatively adapt and strategise in a given field, even when the conditions and rules to which their habitus was accustomed have since changed. New artefacts and different behaviours can, in accordance with the changing field conditions, enjoy new legitimacy and become better able to reproduce different sorts of capital. Cultural capital is, in particular, available to those quickest and most adept at strategising their way through the shifting social landscape (Bourdieu 1996; David 2015).

In combining Bourdieu’s social theory and the good farmer concept, researchers have been able to examine which behaviours and landscapes reproduce (or lose) which capitals, what motivational influence these social codes exert, and how these forces change over time. By using the good farmer concept and Bourdieu’s social theory, this paper provides some answers to the research questions described in the paper’s introduction.

Methodology and research context

The analysis presented here comes from a PhD project co-funded by Natural England (NE), designed to look into the long-term social and management changes catalysed through participation in an AES. The research is based on 65 in-depth semi-structured interviews with 40 different interviewees (25 of the 40 gave a repeat interview 1 year after the initial interview), all of which lasted between 45 and 90 min. Interviews took place in the summers of 2017 and 2018. Collection was capped to 65 interviews primarily because the data had reached a saturation point—although limitations imposed by the PhD timeline were also a minor factor. Although data from both interviews and repeat interviews are used in this analysis, their sequential aspect relates to topics not relevant here and so where respondents gave two interviews, they are analysed and presented here as one. The repeat interviews did, however, facilitate a members check, improving the robustness and trustworthiness of data analysis (Birt et al. 2016): second interviews were partially framed around the comments made in the first interviews, allowing interviewees to refine or revise the perception the interviewer had generated about their attitudes and behaviours. To further add to the trustworthiness of the analysis, a post-data collection peer debriefing process was also completed (Morse et al. 2002; Janesick 2007). Following the guidelines described by Barber and Walczak (2009), unprocessed and unannotated interview transcripts were provided to the manuscript’s second author, with only general research themes being provided to initiate the coding and analysis process. A full data set of interview transcripts was provided, not just the 25% Barber and Walczak (2009) recommend as a minimum. The similarities and discrepancies between the respective analyses were then scrutinised, allowing room to challenge biases and verify findings.

For both authors, an inductive-deductive hybrid process was used for coding. Pre-determined nodes relating to agricultural attitudes towards ELMs and public goods provision were used, with additional nodes getting added during successive rounds of coding. Not all of the 40 interviewees have their contributions used in the presentation of this analysis—although the excerpts used here are reflective of the attitudes of the research sample as a whole. Discussion of the project’s other findings can be seen at Cusworth (2019) and Cusworth (2020). Interviews were kept relevant by a set of conversational questions orientated around target themes. The interview schedules were subject to the scrutiny of the Defra’s survey control unit. As part of the studentship sponsorship arrangement, the contact details of the ELS participants were provided by NE.

The interview sample was heterogenous with arable mixed and livestock units all represented. To allow for meaningfully comparable data, the interview schedule allowed the interviewees to self-identify which particular public goods were relevant to their own farms, and which goods represented the most and least attractive prospects for them. The majority of the discussion revolved around the provision of environmental public goods and, to a lesser extent, access to natural areas for recreation, and the preservation of cultural heritage. Certain good (animal welfare, for example) were only raised by a few interviewees. This aspect of the interview design allowed participants to discuss their attitudes towards the provision of public goods through the lens of the good(s) most compelling or relevant to them. Systematic research would be well placed to offer higher-resolution analysis on the ways in which farming identities interface with different public goods.

A note is needed on the extent to which the paper is able to interrogate the specifics of the country’s transition to the public goods model. At the time of interviewing, details around the design of ELMs, the Agriculture Bill and the Environment Bill were sparse. Although enough was known about the policy changes (removal of direct support, prioritisation of public goods) for relevant and insightful discussion to take place, certain elements of the post-Brexit agricultural regime were not systematically included in the interview schedule. These include the 3-tier approach (farm-, local-, and landscape-scale interventions) of ELMs (Defra 2020a); collaborative scheme contracts (Defra 2020b); and the inclusion of animal welfare and carbon sequestration as public goods (Houses of Parliament 2019).

Although these themes were present in the public discourse, particularly for the 2018 interviews, they were not part of the deductive pre-determined research remit. The political situation at the time was highly fluid, with different ideas and anxieties around agricultural policy design continually coming in and out focus. To avoid the interviews becoming overly weighed down with speculation, the questions of the interview schedule were restricted to the higher-level themes that were less subject to frenetically changeable political developments. Whilst it would have been preferable to orientate the research around a more ‘finished product’, these omissions did not prevent the data collection or analysis from critically engaging with many of the major themes of the agricultural policy transition.

The interviews were conducted with participants of the Entry Level Stewardship (ELS) portion of the Environmental Stewardship (ES) scheme (excluding those with a targeted higher-level component). ES was the main AES in England from 2005 to 2014. The author recognises the biasing influence this methodology may have created. By canvassing opinions from land managers already engaging in the provision of public goods, it could be argued that the research is bound to generate an unrepresentatively positive account of the attitudes towards the varied roles that the agricultural industry is being asked to adopt.

The complaint has mileage. ELS’s design, however, combined with characteristics of its participant-base serve to mitigate against such biasing effects. ELS was a ‘broad and shallow’ scheme, intended to attract high participation by offering non-competitive, whole-farm contracts that promoted the adoption of simple management practices (Hodge and Reader 2010). At its peak in 2013, ELS covered 72% of Utilisable Agricultural Area in England (JNCC 2017). The amount of ‘deadweight’ in the scheme was high—with many contracts requiring little to no management change (Defra 2012). The motivations for participation were not, typically, an expression of farmers’ environmentalist commitments or about radical re-orientations of their farm businesses. Instead, participation was about unlocking easy-to-access finance for the adoption of simple management changes (Cross and Franks 2007; Defra 2012; Hodge and Reader 2010). For most participants—amongst the interviewees and across the scheme more generally—ELS was their first engagement in an AES. Speaking to its participants was used, therefore, as a methodological tool to gauge the attitudes of managers engaging in an AES located towards the start of the spectrum of the public goods model, and to assess their attitudes as the subsidy system progresses along that continuum. The author nevertheless recognises the influencing impact of this research design.

The interviews were split evenly across two case study areas shown in Fig. 1. The case study areas were made up of groupings of National Character Areas—the administrative units used in the administration of AESs. The two areas were chosen to reflect areas of different farm systems—with the Eastern area having a higher concentration of arable farming and the Midlands area, livestock and mixed farming. The interviewees represented an even spread of small and large farms, operating a range of livestock, mixed and arable farms. The responses from the two case study areas are not contrasted with each other, nor are the responses of interviewees with different farm sizes or systems.

This particular decision mirrors a methodology employed in previous good farmer related research (Burton et al. 2008; Burton 2012). Namely, to use different case study areas to identify which features of the good farmer are common amongst farmers in different areas, on different systems and of different sizes—not as a means of generating a comparative study of which ideals exist where in the industry. To reflect this, the interviews from the different areas are presented and analysed as one. Again, future research would be well placed to develop more granular analysis of the good farmer concept and how it might apply to farmers from different area operating farms of different sizes or systems.

In the presentation of the data, interviewee’s attributable details are removed, and each interviewee is assigned a random interview number. To give some character to the interviewee’s comments, though, a brief precis of their farming biography is given (size, system, tenancy).

Findings and discussion

The ‘good farmer concept’ and the provision of public goods

The relationship the interviewed farmers had towards the provision of public goods was, by and large, positive. That positivity was, however, contingent on the financial remuneration associated with the provision of those goods and the perceived benefits it could offer for the maintenance of a financially viable farm. Especially given the sub-text of the public goods transition in which ELMs participation is set to be the only financing made available to farmers, this is perhaps unsurprising. Consider the following excerpts:

Interviewee 28, a large arable farmer who undertakes a lot of local contracting work explained:

I don’t give a damn so long as we’re paid for it… If I can make as much money growing flowers, I’m happy to grow flowers.

Interviewee 18, who manages a medium-sized mixed-farm with a significant diversification arm to the business:

If you paid us more to have a wild meadow full of lovely flowers than grow wheat, I’d be terribly happy with that.

And Interviewee 3, who manages a large estate with traditional parkland grazing and arable land, speaks to the implications the policy transition has on farming identities:

It [reduction in direct subsidisation, introduction of ELMs] is definitely a step towards becoming environmental stewards rather than farmers which doesn’t bother me…I’ve been brought up that the farm is a business and if they’re going to pay you to crop it environmentally, then that’s the niche to go into.

The cultural resistance historically associated with the provision of public goods and the landscapes they produce (Burton et al. 2008) has abated to the extent that the farmers are willing to engage in that model, provided the financial remuneration is pitched at the correct level. Even the problematic ‘untidiness’ reported by various studies about the willingness to deliver environmental goods (Kohler et al. 2014) do not appear to be relevant. The “meadow full of lovely flowers” cited by Interviewee 18 is the precise sort of untidy, unfarmed aesthetic that has elsewhere been recorded as the type of management practice that undermines farmers’ inclination to deliver public goods. That management practice is used here, however, to exemplify a willingness to engage.

Shifting agro-economic conditions have propelled changes elsewhere in the rules of the agricultural field. The consumer preferences that have carved out a viable marketing niche for organic produce have seen organic management become capable of reproducing embodied cultural capital for participating managers (Sutherland and Darnhofer 2012). The primacy of managing a viable business in the good farmer concept (Sutherland 2013), is here recasting the reputation and prestige associated with the delivery of public goods. The managers are mindful of the increasing economic importance of having a public goods element on the farm and are projecting their respect onto the practices that can help unlock that money. The good farmer is sufficiently agile to respond to these changing economic realities such that cultural capital is not risked, as it once was, through the adoption of practices that pertain to the production of non-agricultural goods and untidy landscapes. The reformulated rules do not imply a conflation of public goods provisioning and cultural capital reproduction; but rather, a more complete integration of agricultural productivity and the delivery of public goods as behaviours integral to running a viable farm business.

In Bourdieusian terms, the rules of the game have shifted to accommodate the field conditions that increasingly dictate how participation in public goods schemes pertains to the financial sustainability of a farm unit. Although the Brexit transition has provided an additional injection of impetus, the economic and policy transition towards the public goods model, has happened at such a rate that the changes have been internalised into habituses of the managers. ELS’s widespread uptake has been particularly noteworthy in normalising public goods subsidisation in the agricultural sector (Cusworth 2020). As a result, none of the interviewed farmers expressed concerns around the principles of the shift to a public goods model, or the practices or landscapes associated with public goods provisioning (although it is important to remember that the interviewees were engaged with the ‘broad and shallow’ design of ELS, and so didn’t have to make any drastic public goods-orientated changes in how they managed their farms). Concerns were, instead, raised around the scale of remuneration set to be made available through the new scheme.

Interviewee 22, a younger farmer who had recently taken charge of the family’s medium-sized arable farm, explained some of these reservations. Despite being highly receptive to the idea of basing his farm’s business on the provision of public goods, he explained that:

Any time they’re going to taking down money [through direct subsidisation] you’re never going to get as much out the other end [for providing public goods].

Such findings stand in contrast to those of Howley et al. (2014), who found that farmers’ willingness to provide public goods was outweighed by the public’s willingness to finance them. The difference in findings is neatly summed up by the assessment offered by Interviewee 21, an arable farmer with rented and owned land:

My quandary is whether society is happy to pay for those goods, because there’s a large part of society feels entitled to them.

And by Interviewee 17, who manages a medium-sized dairy herd, referring to one public good in particular—providing access to the environment. Again, the grievance is not about undertaking the work to provide the good, but a mismatch between people’s willingness to pay and the goods they expect agriculture to be providing:

People think ‘why should they [farmers] get all this money?’ But people expect to drive through the countryside, and expect the bridal paths to be open, to be able to walk through it, with everything pretty and nice!

Whilst the public may be theoretically amenable to the idea of paying for public goods, because of the managers’ understanding of the how expensive those goods are, they remain sceptical that sufficient funds will be on offer. Other fears about the move to the public goods model were also highlighted. Here, Interviewee 37, another larger arable unit with both owned and rented land, explains his fears around the increased surveillance that comes when accepting money through public financing:

The whole policy seems to be “we are giving you public money for public goods.” Fine. “We will enforce that by penalising you if you get it wrong, we won’t come and help you, we won’t come and advise you.” It’s a small carrot and a big stick.

Interviewee 21, who runs an arable farm and takes on contract work for other farmers, raises a similar point. The interaction with government services that comes with the public money for public goods model may frustrate the sector’s willingness to engage once the direct support has been removed:

[Once direct subsidisation is gone] there’s less reason to get the interaction with the government agencies – the further arm’s length the better… It’s the triggering of inspections.

There was, however, a general acceptance around the need to demonstrate the additionality of public goods subsidy. Comparing the evidence needed for his ELS and subsequent CS contract, Interviewee 4’s reflections are more representative of the research sample’s attitude towards subsidisation, evidence provisioning and government interaction:

The ELS scheme… you weren’t really answerable to anybody. With the mid-tier, they are asking for a lot more proof for what you’ve done.

Justifiably do you think? [interviewer]

Well if it’s public money, yeah definitely!

Interviewee 26—who manages a mixed farm with his son—typifies the pragmatism the interviewees felt towards the changing subsidy arrangement. As public goods money becomes the only support available to a sector that has grown accustomed to some income support, the industry’s willingness to engage will surely follow:

If farmers have an opportunity to get paid to do something, and they believe it makes commercial sense, a lot of farmers, once you get over the transition will say “if it’s do this and get some money versus do nothing and get no money, as long as the money is reasonable, I’d better do that.”

Land sparing, land sharing and the re-orientation of productivist dispositions

That farmers are amenable to the public goods model, and that it is compatible with the good farmer ideal does not fully capture the more complex reality. Consider the comments of Interviewee 29, who manages a large mixed-farming estate, discussing his perspective on the sector’s willingness to engage in future subsidisation. The discussion here was conducted in relation to the repurposing of ELS options for use in a future CS or for ELMs contract:

If you pick a farm in the middle of the Fens, I think those guys will be taking their strips out [of any future scheme and back into production], because I think they’ll take a view that they can grow a high value crop because it’s still pretty good land. But if you take a rural estate, perhaps one that has been an ex-livestock farm and has gone all arable, with some small fields, and shady corners by the sides of woods, I think those will be the guys who will be leaving what they put in [through ELS].

Interviewee 16, a farmer with a small mixed farm, responds to a similar question:

If the money is good enough, it means you haven’t got to do the [agricultural] work. It’s a win–win for everybody. And there’s parts of the farm – everybody has got them – that are so marginal it’s not worth producing.

Certain management practices are expected or acceptable on certain parts of the farm that are not respected or acceptable on others. The rules of the game are subtly tuned to the land in question, such that the management decisions that are best placed to reproduce cultural capital on some farm, or on some part of a farm, are different to the management decisions best able to reproduce cultural capital on others. These reflections are primarily rooted in the economics of farm management. If there are areas of poor land that offer lower economic returns through agricultural production, then the opportunity to be paid to provide some public good represents savvy farm business management. For a farm’s prime agricultural land, where economic capital is best secured through traditional agricultural production, there is recognition and respect for those prioritising food production. Admitting and integrating some public goods orientated subsidisation onto certain areas of the farm lends an additional legitimacy to other areas dedicated to food production. The judgements passed by the above interviewees reveal how cultural capital is available for managers embodying this management adaptability.

Whilst this ‘public goods-land quality-cultural capital’ matrix may seem intuitive, it warrants some unpacking. The idea of land sharing and land sparing can here be used to give expression to this particular aspect of the good farmer ideal. Land sharing relates to the practice of co-locating agricultural production and other public goods provision on the same land. Land sparing relates to the practice of separating where food is produced, and where other public goods are delivered (Fischer et al. 2008). The two are frequently presented as binary and opposing visions for how agriculture might best meet the competing pressures to produce food and provide a healthy environment. Should the negative externalities of agriculture be reduced, per unit area of land, by ‘de-intensifying agricultural’ production, thereby providing a more generous allowance for biodiversity and water quality to recover on farmland (land sharing); or should good agricultural land be focussed on maximising food production, leaving the remainder to be put to dedicated environmental or other public goods usage (land sparing)?

The responses of the interviewees—typified in the above excerpts—show how a preference for the land sparing model has been encoded into the rules of the game. The regard the above interviewees expressed for managers maintaining or removing their ELS scheme features is calibrated to the quality and type of land put in in the first place. If the land is of high quality, and can be easily integrated into a field’s cultivation, then its appropriate use is in agricultural production—hence the recognition and regard for managers returning such land previously in the ELS scheme into production. For marginal land, or land that is not easily farmed, there is a recognition of its poor agricultural potential and its appropriate use is for it to be contributing to the environmental ‘output’ of the farm and to be used in some public goods-orientated subsidisation. Embodied cultural capital is, in this way, available for the managers identifying these varied and appropriate potentials and maximising their respective outputs.

This preference for land sparing options, it is argued, is the result of conflicting claimants on agricultural identities. The historical preference for productivist objectives and the corresponding food-producing identity that previous research has attributed to the farming population (Silvasti 2003; Burton 2004) is clearly still in effect. Where food can be effectively produced, then the appropriate use is for it to be committed to concerted food production. Cultural capital flows accordingly. The above farmers nevertheless recognise the business value of integrating some public goods element onto their farm, and accept the implicit duty that agriculture has to better manage its environmental impact (Cusworth 2020). The finances made available through AESs, especially as they allow participants to choose where on the farm the scheme options are located, offer farmers the opportunity to live out these dual personalities, allowing them to service the broader imperative of running a successful farm business. This ‘public goods provider’ identity has been integrated—or, more accurately, been given good room to co-exist—with the extant productivist farming identity.

These findings also make for heartening reading for those interested in the wider objectives of the policy transition. Whilst ELMs and the Agriculture Bill are frequently discussed in terms of their prioritisation of public goods (Bateman and Balmford 2018), agricultural productivity remains an important element in the country’s farming strategy (Defra 2018b, 2020a). The above analysis demonstrates the important role farmers have in brokering and delivering on the sometimes antithetical objectives of having a highly productive and sustainable food production system. Especially given the additional decision-making influence applicants are being afforded in ELMs’ more results-orientated and the targeted application design (Defra 2020a), the expertise individuals farmers have in knowing how agricultural productivity and public goods provisioning can be optimised on their farms will be of major value.

The account of Interviewee 17 neatly captures the interplay of the public goods provider and food producer identities—and how the finances available for the provision of public goods lubricates their co-existence as two forces contributing to the farm’s financial stability. Again, the preference for the land sparing model, in which one’s food production and one’s public goods delivery are located on different parts of the farm (cf. the delivery of both on the same parcels) are in evidence when he explains that:

You only do that for a proportion of the farm – it’s nice to see the flowers up there on the wispy meadow, but you wouldn’t want to see it all over the place.

A note here is needed about scale and resolution. There is ongoing debate—and considerable ambiguity—around the spatial scale at which land sparing interventions occur. As Fischer et al. (2013, p. 153) note, “sparing is often assumed to imply a large geographic extent and a coarse spatial grain… However land sparing has also been used to refer to conservation measures only visible at a fine spatial grain, including field margins or land set aside… [so] it is often unclear when sharing becomes sparing”. It is important to understand that in attributing a preference for land sparing interventions to the good farmer ideal, this more general definition (one that includes both fine and coarse spatial grain strategies) is employed.

Larger-scale resolution land sparing interventions were, however, also well regarded. Interviewees discussed how the need for the sector to produce both agricultural and public goods played out across different regional and inter-farm (from farm to farm), as well as intra-farm (within a given farm) scales. Whole farms operating in certain landscape types were identified as those that should be adopting a business model predicated on the delivery of public goods, whilst others were identified as those that can legitimately be making no public goods allowances. Interviewee 4, who manages a medium-sized arable farm, offers his assessment of the role future subsidies will play in how he manages his farm:

I’m quite happy on a farm like this to go down the environmental route, because it isn’t a productive farm, and it isn’t a viable arable farm in its own right. Not like some of the farms in East Anglia, huge farms – they probably stand up on their own right.

His neutral assessment of both the hypothetical East Anglian farms adopting a model predicated on productivity, and the management plans he has for his own farm is revealing. He is not critical or supportive of either model in abstract, and his respect is not necessarily earnt through the pursuit of one model or the other. Instead, the legitimacy of each model is predicated on the landscape characteristics of the farm, and the determining role this has in selecting which management practices are able to deliver on the farm’s potential. The good farmer concept implies an ability to step back from one’s unit to assess where it fits in with the broader strategic ambitions for the country’s agricultural sector, and how the farm’s business model (i.e., the extent to which it produced public goods and/or agricultural outputs) should be designed. The censure or respect a farmer is liable to receive vis-à-vis their engagement with public goods subsidisation is highly context-dependent—an equation that cannot happen in isolation from the quality of the land and its different potentials. Similar to the analysis of Sutherland and Darnhofer (2012), being able to ‘creatively respond’ to the changing conditions in the agriculture field (here concerning the dual pressures of contributing to a productive and sustainable industry) is an important predictor in the reproduction of cultural capital.

Reflecting on how the farm sector’s varied obligations can be met, Interviewee 33, who runs a medium-sized owned arable unit, explains:

You’ve got to sort of ring fence it [subsidisation for public goods] and say “actually we need to have a balanced agricultural world, where there’s some that’s really commercial and some that’s less commercial.”

This location-sensitive vision of what constitutes good and appropriate management mirrors the research of Jongeneel et al. (2008). They found that Dutch farmers’ willingness to adopt non-food orientated business models, especially regarding tourism- and environmental-related goods were location dependent. Farmers in the west of the country, in areas of higher environmental and tourism value, were more willing to adopt such public goods orientated business models than those in the east, where the agricultural output is traditionally higher and more intensive.

This balancing act is captured by Interviewee 12, who runs a small farm consisting mostly of grazing land:

Not every farm would suit that [a business model predicated on subsidisation and the provision of public goods]. My land suits it, because it’s that type of farm, small fields, plenty of hedges, and the spinney [a small wooded area]. But if you’ve just got 130 acres of flat arable land, why are they going to get anything for environmental?

And Interviewee 26, who owns and runs a large arable holding:

If you look at a Norfolk farmer farming on light sandy soils, compared to a Somerset farmer doing mainly dairy, and worried about not having too much rain –the two are so totally different that you couldn’t conceivably think they would have the same thoughts on these things [providing public goods, and going into ELM].

The above accounts are, in part, prompted by the economic turbulence that the removal of direct subsidy will deliver for many farmers across the UK (Helm 2017; Defra 2018c; Mason 2019). The above interviewees are engaging in some speculative accounts-keeping, working out how their—and other’s—farms might avoid the economic bottom-line. Namely, by boosting the agricultural and public goods arms of their business, or the prioritisation of one at the expense of the other. Similar to the comments Arnott et al. (2019) make in relation to the Brexit process, the perils for farm businesses manifest in the redirection of direct support to public goods subsidisation has a natural fit with land sparing interventions in which farmers can more effectively maximise their different revenue streams—a synergy made more plausible by the amenability of farming psychologies to land sparing practices.

Some key elements of the productivist identity are, it is argued, being repurposed to navigate modern economic and social pressures. There is a mission creep of the productivist aspect of the good farmer concept (with its attendant preference for efficiency, scale, intensification, and specialisation) resulting in the annexation of the provision of public goods into the list of accepted and valorised outputs. Or seen from the obverse, the budding public goods provider identity is being coloured by the long-standing regard for efficiency and productivity.

Bourdieu’s conceptualisation of how the habitus performs in periods of social change is instructive. The habitus is an inscription of history that provides an inertia in determining who an individual is and how they act over time (Bourdieu 1990; Maton 2008). Changes in an individual’s habitus occur only to the extent required by the shifting field conditions (Bourdieu 2000). Individuals creatively respond to those changes (Reay 2004; Sutherland and Darnhofer 2012) whilst preserving, as much as is practicable, pre-existing modes of being (Kerr and Robinson 2009). Here, the long-standing preference for, and celebration of, scale and efficiency are being maintained in farming habituses as they creatively respond to the new social and economic realities manifest in the transition to a public goods model of subsidisation. Farmers are looking to maximise their output, engage in economies of scale, intensify and make efficient—although here in a setting in which public goods and agricultural commodities are all implicated. Related to the analysis of farm benchmarking groups, the competitiveness and desire for performance improvements embedded in farming communities can be harnessed for environmental and public goods gains (de Snoo 2006).

This excerpt from Interviewee 22—the younger farmer who now manages the family’s large arable farm—captures how extant productivist preferences for specialisation and efficiency, historically reserved for agricultural productivity, are being extended to the delivery of public goods.

We’re trying to do [pollinator and bird mix plots] on a field scale. We’ve got an 11-acre field and a 3-acre field, and we just do the whole lot. We treat it like a crop [emphasis added].

Conclusion

Alongside the paper’s contribution to the iterative study of agricultural attitudes and identities, the paper’s findings have direct policy implications, including for some of the ‘priority themes’ in ELMs research and development (Defra 2020c). The synergy between farming identities and land sparing strategies might have a telling influence on the country’s agricultural policy transition. ELMs is being designed to afford farmers greater autonomy in mediating and delivering the dual needs for a sustainable and productive agricultural sector on their farms. The proclivity for farmers to seek maximisation, efficiency and optimisation may help get the most out of the country’s farmland—both in terms of food produced and public goods provided.

The preference for ‘sparing’ parcels of less-productive land for public goods provision augurs well for other aspects of ELMs design, too. A number of ELMs trials are exploring approaches to Land Management Plans, which at the farm scale will include some form of natural capital audit and accompanying farm business plan. See Northern Uplands ELMs Test and Trial report (Landscapes for Life 2020) for an example. In reviewing and mapping their land, managers will have to actively consider the areas of the farm where the production of environmental, cultural and agricultural goods are most suited. In doing so, they may acknowledge new kinds of value in areas of their farms they might previously have discounted—a prospect already attracting some excitement in the farming press (Harris 2019). Although the natural capital approach represents the further expansion of market logics into environmental protection (and thus inherits a whole host of criticism—see Arsel and Buscher 2012 for discussion), it is a model that has good fit with the business-minded and efficiency-seeking aspects of agricultural identities.

Many previous studies have linked a willingness to participate in an AES with the level of financial remuneration (Lastra-Bravo et al. 2015). That the good farmer’s amenability to public goods provisioning stems primarily from the business advantages a scheme can offer, the link is here re-iterated. The (perceived) imbalance between the “small carrot and big stick” (to quote Interviewee 37 again) must be redressed if ELMs is to represent an attractive payment opportunity for the country’s farmers. The authors share Defra’s concern that basing payment rates in Tier 1 of ELM on income foregone alone may not encourage the desired level of uptake (Defra 2020a): payments must also offset the more intangible costs of participation, such as the negative pressures of scheme bureaucracy and threat of scheme penalties.

Abbreviations

- EU:

-

European Union

- CAP:

-

Common Agricultural Policy

- Defra:

-

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

- AES:

-

Agri-environment scheme

- GHGs:

-

Greenhouse gases

- ELM:

-

Environmental Land Management

- NE:

-

Natural England

- ES:

-

Environmental Stewardship

- ELS:

-

Entry Level Stewardship

References

Arnott, D., D. Chadwick, S. Wynne-Jones, and D. Jones. 2019. Vulnerability of British farmers to post-Brexit subsidy removal and implications for intensification, extensification and land sparing. Land Use Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104154.

Arriaza, M., J.F. Canas-Ortega, J.A. Canas-Maduenoa, and P. Ruiz-Aviles. 2004. Assessing the visual quality of rural landscapes. Landscape and Urban Planning 69 (1): 115–125.

Arsel, M., and B. Buscher. 2012. Nature Inc.: Changes and continuities in neoliberal conservation and market-based environmental policy. Development and Change 43 (1): 53–78.

Barber, J., and K. Walczak. 2009. Conscience and critic: Peer debriefing strategies in grounded theory research. In Discussion paper presented at the annual meeting of American Educational Research Association 2009.

Bateman, I., and B. Balmford. 2018. Public funding for public goods: A post-Brexit perspective on principles for agricultural policy. Land Use Policy 79 (1): 293–300.

Birt, L., S. Scott, D. Cavers, C. Campbell, and F. Walter. 2016. Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness of merely a not to validation? Qualitative Health Research 26 (13): 1802–1811.

Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of a theory of practice. Trans. Richard Nice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. 1983. The field of cultural production, or: The economic world reversed. Poetics 12 (4–5): 311–356.

Bourdieu, P. 1986. The forms of capital. In Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education, ed. J. Richardson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood Press.

Bourdieu, P. 1990. The logic of practice. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P. 1996. The rules of art: Genesis and structure of the literary field. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P. 2000. Making the economic habitus: Algerian workers revisited. Ethnography 1 (1): 17–41.

Bourdieu, P., and L. Wacquant. 1992. An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Buller, H., and C. Morris. 2004. Growing goods: The market, the state, and sustainable food production. Environment and Planning a: Economy and Space 36 (6): 1065–1084.

Burton, R. 2004. Seeing through the ‘Good Farmer’s’ eyes: Towards developing an understanding of the social symbolic value of ‘Productivist’ behaviour. Sociologia Ruralis 44 (1): 195–215.

Burton, R. 2012. Understanding farmers’ aesthetic preference for tidy agricultural landscapes: A Bourdieusian perspective. Landscape Research 37 (1): 51–71.

Burton, R.J., C. Kuczera, and G. Schwarz. 2008. Exploring farmers’ cultural resistance to voluntary agri-environmental schemes. Sociologia Ruralis 48 (1): 16–37.

Burton, R.J.F., and U.H. Paragahawewa. 2011. Creating culturally sustainable agri-environmental schemes. Journal of Rural Studies 27 (1): 95–104.

Cooper, T., K. Hart, and D. Baldock. 2009. The provision of public goods through agriculture in the European Union. Report Prepared for DG Agriculture and Rural Development, Contract No. 30-CE-0233091/00-28. London: Institute for European Environmental Policy.

Cross, M., and J. Franks. 2007. Farmer’s and advisor’s attitudes towards the Environmental Stewardship Scheme. Journal of Farm Management 13 (1): 47–68.

Cusworth, G. 2019. Exploring the long-term social and land management impacts on participants of the Entry Level Stewardship Scheme. PhD Dissertation, University of Gloucestershire. http://eprints.glos.ac.uk/9268/. Accessed Jan 2021.

Cusworth, G. 2020. Falling short of being the ‘good farmer’: Losses of social and cultural capital incurred through environmental mismanagement, and the long-term impacts of agri-environment scheme participation. Journal of Rural Studies 75 (1): 164–173.

Czyzewski, A., and S. Stepien. 2018. Discovering economics in the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy. Recommendations for the new period 2021–2026. In Proceedings of the international scientific conference “Economic Sciences for Agribusiness and Rural Economy No. 2”.

David, C. 2015. Learning to fly: Entering the youth mobility field and habitus in Ireland and Portugal. In Bourdieu, habitus and social research: The art of application, ed. C. Costa and M. Murphy, 111–125. Londres: Palgrave MacMillan.

Defra (Department for the Environment Food and Rural Affairs). 2012. Dynamic deadweight in Environmental Stewardship—Towards a better understanding of the added benefits of the scheme. Report compiled by GHK, in consultation with Land Use Consultants.

Defra (Department for the Environment Food and Rural Affairs). 2018a. Health and Harmony: The future for food, faring and the environment in a Green Brexit—policy statement. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/684003/future-farming-environment-consult-document.pdf. Accessed June 2019.

Defra (Department for the Environment Food and Rural Affairs). 2018b. A green future: Our 25 year plan to improve the environment. Government Plan https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/693158/25-year-environment-plan.pdf. Accessed Aug 2020.

Defra (Department for the Environment Food and Rural Affairs). 2018c. The Future Farming and Environment Evidence Compendium, Statistical compendium. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/683972/future-farming-environment-evidence.pdf. Accessed Aug 2020.

Defra (Department for the Environment Food and Rural Affairs). 2018d. Moving away from direct payments, statistical review. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/740669/agri-bill-evidence-slide-pack-direct-payments.pdf. Accessed Aug 2020.

Defra (Department for the Environment Food and Rural Affairs). 2020a. Environmental Land Management: Policy discussion. document https://consult.defra.gov.uk/elm/elmpolicyconsultation/. Accessed Sep 2020.

Defra (Department for the Environment Food and Rural Affairs). 2020b. Farming for the future: Policy and progress update. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/868041/future-farming-policy-update1.pdf. Accessed Aug 2020.

Defra (Department for the Environment Food and Rural Affairs). 2020c. Environmental Land Management Tests and Trials: Quarterly Evidence Report. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/environmental-land-management-tests-and-trials. Accessed Jan 2021.

Dobbs, T., and P. Pretty. 2004. Agri-Environmental Stewardship Schemes and “Multifunctionality.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 26 (2): 220–237.

EPRS (European Parliamentary Research Service). 2018. CAP reform post-2020: Setting the scene. Policy research brief. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/621906/EPRS_BRI%282018%29621906_EN.pdf. Accessed June 2019.

Fischer, J., B. Brosi, G.C. Daily, P.R. Ehrlich, R. Goldman, J. Goldstein, D.B. Lindenmayer, A.D. Manning, H.A. Mooney, L. Pejchar, J. Ranganathan, and H. Tallis. 2008. Should agricultural policies encourage land sparing or wildlife-friendly farming? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 6 (1): 380–385.

Fischer, J., D. Abson, V. Butsic, M. Chappell, J. Ekroos, J. Hanspach, T. Kuemmerle, H. Smith, and H. Wehrden. 2013. Land sparing versus land sharing: Moving forward. Conservation Letters 7 (3): 149–157.

Gorton, M., E. Douarin, S. Davidova, and L. Latruffe. 2008. Attitudes to agricultural policy and farming futures in the context of the 2003 CAP reform: A comparison of farmers in selected established and new Member States. Journal of Rural Studies 24 (3): 322–336.

Harris, L. 2019. Natural Capital: what is it and how to value it on your farm. Farmers Weekly, 24 May, published on the Farmers Weekly website. https://www.fwi.co.uk/business/payments-schemes/environmental-schemes/natural-capital-on-farms-what-it-is-and-how-to-value-it. Accessed Jan 2021.

Helm, D. 2017. Agriculture after Brexit. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 33 (1): s124–s133.

Hilgers, M., and E. Mangez. 2015. Introduction to Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of social fields. In Bourdieu’s theory of social fields: Concepts and applications, ed. M. Hilgers and E. Mangez. London: Routledge.

Hodge, I. 2000. Agri-environmental relationships and the choice of policy mechanism. The World Economy 23 (2): 257–273.

Hodge, I., and M. Reader. 2010. The introduction of Entry Level Stewardship in England: Extension or dilution in agri-environment policy? Land Use Policy 27 (2): 270–282.

Houses of Parliament. 2020. Agriculture Bill, Explanatory Notes. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/58-01/0007/en/20007en.pdf. Accessed Jan 2021.

Houses of Parliament. 2019. PostNote Climate change and agriculture, Number 600. Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology.

Howley, P., C. Donoghue, and S. Hynes. 2012. Exploring the general publics’ preferences for traditional farm landscapes. Landscape and Urban Planning 104 (1): 66–74.

Howley, P., L. Yadav, S. Hynes, C.O. Donoghue, and S.O. Neill. 2014. Contrasting the attitudes of farmers and the general public regarding the “multifunctional” role of the agricultural sector. Land Use Policy 38 (1): 248–256.

Hubbard, C., J. Davis, S. Feng, D. Harvey, A. Liddon, A. Moxey, M. Ojo, M. Patton, G. Philippidis, C. Scott, S. Shrestha, and M. Wallace. 2018. Brexit: How will UK agriculture fare? EuroChoices 17 (2): 19–26.

Jaffe, A., R. Newell, and R. Stavins. 2005. A tale of two market failures: Technology and environmental policy. Ecological Economics 54 (2–3): 164–174.

Janesick, V.J. 2007. Peer debriefing. In The Blackwell encyclopaedia of sociology, ed. G. Ritzer. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing.

JNCC, Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC). 2017. UK Biodiversity Indicators, Supplementary Data.

Jongeneel, R., N. Polman, and L. Slangen. 2008. Why are Dutch farmers going multifunctional? Land Use Policy 25 (1): 81–94.

Junge, X., P. Lindemann-Matthies, M. Hunziker, and B. Schüpbach. 2011. Aesthetic preferences of non-farmers and farmers for different land-use types and proportions of ecological compensation areas in the Swiss lowlands. Biological Conservation 144 (5): 1430–1440.

Kallas, Z., J.A. Gómez-Limón, and M. Arriaza. 2007. Are citizens willing to pay for agricultural multifunctionality? Agricultural Economics 36 (1): 405–419.

Kantelhardt, J. 2006. Impact of the European Common Agricultural Policy Reform on future research on rural areas. Outlook on Agriculture 35 (2): 143–148.

Kerr, R., and S. Robinson. 2009. The hysteresis effect as creative adaptation of the habitus: Dissent and transition to the ‘Corporate’ in Post-Soviet Ukraine. Organization 16 (6): 829–853.

Kohler, F., C. Thierry, and G. Marchand. 2014. Multifunctional agriculture and farmers’ attitudes: two case studies in rural France. Human Ecology 42 (6): 929–949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-014-9702-4.

Kuhfuss, L., R. Preget, S. Thoyer, N. Hanley, and P. Le Coent. 2016. Nudges, social norms and permanence in agri-environmental schemes. Land Economics 92 (4): 641–655.

Kvakkestad, V., P.K. Rorstad, and A. Vatn. 2015. Norweigan farmers’ perspectives on agriculture and agricultural payments: Between productivism and cultural landscapes. Land Use Policy 42 (1): 83–92.

Landscapes for Life. 2020. ELM Test and Trial Update, April–June 2020. https://landscapesforlife.org.uk/about-us/farming-nation-environmental-land-management-scheme/latest-updates. Accessed Jan 2021.

Lastra-Bravo, X., C. Hubbard, G. Garrod, and A. Tolon-Becerra. 2015. What drives farmers’ participation in EU agri-environment schemes? Results from a qualitative meta-analysis. Environmental Science and Policy 54 (1): 1–9.

Lobley, M., and C. Potter. 2004. Agricultural change and restructuring: Recent evidence from a survey of agricultural households in England. Journal of Rural Studies 20 (4): 499–510.

Mason, R. 2019. Half of UK farms could fail after no-deal Brexit, report warns. The Guardian, 15 December. Published online at https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/aug/15/half-of-uk-farms-could-fail-after-no-deal-brexit-report-warns. Accessed Jan 2021.

Maton, K. 2008. Habitus. In Pierre Bourdieu: Key concepts, ed. M. Grenfell, 49–66. Stocksfield: Acumen Publishing.

Meyer, C., B. Matzdorf, K. Muller, and C. Schleyer. 2014. Cross compliance as a payment for public goods? Understanding EU and US agricultural policies. Ecological Economics 107 (1): 185–194.

Moore, R. 2008. Capital. In Pierre Bourdieu: Key concepts, ed. M. Grenfell, 101–118. Stocksfield: Acumen Publishing.

Moran, D., A. Lucas, and A. Barnes. 2013. Mitigation win–win. Nature Climate Change 3 (1): 611–613.

Morse, J., M. Barrett, M. Mayan, K. Olson, and J. Spiers. 2002. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690200100202.

NAO (National Audit Office). 2019. Early review of the new farming programme. Press release published on https://www.nao.org.uk/press-release/early-review-of-the-new-farming-programme/. Accessed Sep 2020.

National Statistics. 2019. Agricultural and forest area in environmental management schemes. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/925443/22_Agrienvironment_and_forestry_2020_accessible.pdf. Accessed Aug 2020.

Nelson, G., and 11 others. 2010. Food security, farming and climate change to 2050. Scenarios, results, policy options. IFPRI research monograph, International Food Policy Research Institute.

Oueslati, W., and J. Salanié. 2011. Landscape valuation and planning. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 54 (1): 1–6.

Reay, D. 2004. ‘It’s All Becoming a Habitus’: Beyond the habitual use of habitus in educational research. British Journal of Sociology of Education 25 (4): 431–444.

Riley, M. 2016. How does longer term participation in agri-environment schemes [re]shape farmers’ environmental dispositions and identities? Land Use Policy 52 (1): 62–75.

Seabrook, M.F., and C.B. Higgins. 1988. The role of the farmer’s self-concept in determining farmer behaviour. Agricultural Administration and Extension 30 (1): 99–108.

Silvasti, T. 2003. The cultural model of “the good farmer” and the environmental question in Finland. Agricultural and Human Values 20 (2): 143–150.

de Snoo, G. 2006. Benchmarking the environmental performances of farms. The International Journal of Lifecycle Assessment 11 (1): 22–25.

Sutherland, L.-A., and I. Darnhofer. 2012. Of organic farmers and ‘good farmers’: Changing habitus in rural England. Journal of Rural Studies 28 (3): 232–240.

Sutherland, L.-A. 2013. Can organic farmers be ‘good farmers’? Adding the ‘taste of necessity’ to the conventionalization debate. Agricultural and Human Values 30 (3): 429–441.

Thomson, P. 2008. Field. In Pierre Bourdieu: Key concepts, ed. M. Grenfell, 67–82. Stocksfield: Acumen Publishing.

Vilke, R., and Z. Gedminaite-Raudone. 2018. To whom belongs the future of rural prosperity 2020+? In The CAP and national priorities within the EU budget after 2020, Monographs of multi-annual programme 75:1, ed. M. Wigier and A. Kowalski, 50–60. Warsaw: IAFE-NRI.

Wacquant, L. 1989. Towards a reflexive sociology: A workshop with Pierre Bourdieu. Sociological Theory 7 (1): 26–63.

Wacquant, L. 2011. Habitus as topic and tool: Reflections on becoming a prizefighter. Qualitative Research in Psychology 8 (1): 81–92.

Ward, N., P. Jackson, P. Russell, and K. Wilkinson. 2008. Productivism, post-productivism and European agricultural reform: The case of sugar. Sociologica Ruralis 48 (2): 118–132.

Westhoek, H., K. Overmars, and H. van Zeijts. 2013. The provision of public goods by agriculture: Critical questions for effective and efficient policy making. Environmental Science and Policy 32 (1): 5–13.

Willett, W., and 36 others. 2019. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 393 (10170): 447–492.

Wilson, G. 2001. From productivism to post-productivism… and back again? Exploring the (un)changed natural and mental landscapes of European agriculture. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 26 (1): 77–102.

Zasada, I. 2011. Multifunctional peri-urban agriculture—A review of societal demands and the provision of goods and services by farming. Land Use Policy 28 (1): 639–648.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose comments have substantially improved the quality of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cusworth, G., Dodsworth, J. Using the ‘good farmer’ concept to explore agricultural attitudes to the provision of public goods. A case study of participants in an English agri-environment scheme. Agric Hum Values 38, 929–941 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10215-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10215-z