Abstract

Aim

The programme “Join the Healthy Boat” promotes amongst other things a healthy diet in primary school children. In order to evaluate the programme’s effectiveness, this study longitudinally investigated children’s nutrition behaviour.

Subject and methods

A total of 1564 children (7.1 ± 0.6 years) participated in a cluster-randomised study. Teachers delivered lessons including behavioural contracting and budgeting. Nutritional behaviours of parents and child were assessed via parental report. Anthropometrics were measured on site.

Results

After one year, children in the intervention group (IG) showed a significant reduction in the consumption of pure juices (p ≤ 0.001). Soft drink consumption reduced in both groups, although with a trend towards a slightly greater reduction in the IG. Children with fathers of normal weight as well as first graders showed a significant reduction of soft drink consumption in the IG (p = 0.025 and p = 0.022 respectively). Fruit and vegetable intake increased significantly for first graders (p = 0.050), children from families with a high parental education level (p = 0.023), and for children with an overweight father (p = 0.034). Significant group differences were found for fruit and vegetable intake of children with migration background (p = 0.01) and children of parents with a high school degree could be observed (p = 0.019).

Conclusion

This shows that the programme appeals to a wider range of children, and is therefore more likely to compensate for differences due to origin or other social inequalities, which also shows that active parental involvement is vital for successful interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For a healthy physical and mental childhood development, not only are sufficient (everyday) physical activity and active leisure activities (Poitras et al. 2016) necessary, but a balanced, wholesome diet is also of crucial importance (Borrmann and Mensink 2015). An unhealthy diet can lead to concomitant or secondary diseases such as overweight and obesity (Golpour-Hamedani et al. 2020) and diabetes mellitus (Romaguera et al. 2013), but also to a lower cognitive performance (DiGirolamo et al. 2020) and can promote the development of caries (Armfield et al. 2013).

A healthy diet consists, amongst other items, of sufficient fruit and vegetable consumption. Children across the world however eat on average two to three servings of fruit and vegetables per day instead of the recommended five (Evans 2017). One European study found as few as 8.8% of the children reaching the five-a-day target (Kovács et al. 2014). A large German study shows that of 3–17-year-olds, no more than 12% of girls and 9% of boys eat the recommended daily amount of fruit and vegetables (Borrmann and Mensink 2015). Moreover, a negative trend towards older children consuming significantly less fruit and vegetables than younger children (Borrmann and Mensink 2015) adds to this situation. Yet a regular high consumption of fruit and vegetables reduces the risk of ischaemic heart disease and stroke (Boeing et al. 2012), contributes to a wholesome diet, and is particularly important in children and adolescents, due to the positive effects it can have on their physical development and school performance (DiGirolamo et al. 2020), and on the prevention of diet-related diseases such as cardiovascular diseases (Schönbach and Lhachimi 2021).

Nevertheless, not only a lack of fruit and vegetables intake has been reported in Germany, but also the problematic increase in consumption of sweets and sugar-sweetened beverages in almost all children (Graffe et al. 2020). Around one-third of children’s daily energy intake is due to energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods and drinks (Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee 2020; Reedy and Krebs-Smith 2010). On average, 2–9-year-old boys in Europe get 23% of their daily energy from free sugars; girls take in 77 grams of free sugars per day, amounting to 18% of their daily energy intake (Graffe et al. 2020). The foods that contribute most to this free sugar intake are fruit juices, soft drinks, and sweets (Graffe et al. 2020). In Germany, the intake of added sugar ranges between 15.2% and 17.5% in children and adolescents aged 3 to 18 years (Perrar et al. 2019). The main source of dietary added sugar is sugar-sweetened beverages. In Germany, 23% of children consume sugar-sweetened soft drinks such as soda, cola, iced tea, or malt beer daily (Schneider et al. 2020), and the proportion of children increases with age (Schneider et al. 2020; Mensink et al. 2018). Regular and high consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with overall poor diet quality (Louie 2020), weight gain (Qin et al. 2020), and increased risk for diabetes (Drouin-Chartier et al. 2019) as well as for cardiovascular diseases (de Koning et al. 2012; Fung et al. 2009).

Since taste preferences and eating habits develop in childhood (Schwartz et al. 2011), health- and nutrition-related interventions must begin as early as possible in childhood or adolescence, before preferences and habits have developed and solidified (Nicklaus 2016), and they must begin before health-related nutritional problems such as overweight or obesity or deficiency symptoms arise.

Parents, however, are often overwhelmed with the mass of available food and do not know how to help their child to a more favourable and balanced diet. Especially parents in vulnerable subgroups are often inadequately informed about their children’s dietary needs, so that increased obesity occurs in adolescence at the latest (Schienkiewitz et al. 2018). This highlights the immense importance of early support and intervention programmes. Parents and schools must be assisted in their work and support one another.

Parents must be actively involved in setting-based interventions (Waters et al. 2011). Even though children can try out new flavours at school and learn about new foods and how to prepare them, they are still dependent on their parents for regular purchase, selection, and preparation.

In order to achieve permanent change in attitudes and to be able to implement new eating habits in everyday life, interventions aimed at changing eating habits should not only involve parents but also aim at long-term duration of the measures (Waters et al. 2011).

One programme incorporating those aspects is “Join the Healthy Boat”. This low-threshold programme promotes a healthy lifestyle in primary school children in South West Germany. The programme’s contents and materials are integrated into the primary school curriculum, aiming at health-promoting behaviour change. Amongst other objectives, it focuses on a healthier diet, especially targeting a reduction of sugar-sweetened beverages and an increase in fruit and vegetable intake.

In order to evaluate the programme’s effectiveness, this study longitudinally investigated children’s nutritional behaviour. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to assess children’s nutrition behaviours after a 1-year intervention in respect of their consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and intake of fruit and vegetables. The secondary aim was to ascertain whether the intervention programme equally addresses vulnerable subgroups at increased risk for unfavourable eating habits.

Materials & methods

Intervention and evaluation design

“Join the Healthy Boat” is a school-based, teacher-centred health promotion programme, which focuses on sufficient physical activity, reduction of screen media use, and healthy nutrition in primary school children.

This study only concentrates on the part of the intervention concerning children’s healthy diet, which is addressed mainly by a reduction of sugar-sweetened beverages as well as a promotion of daily fruit and vegetable intake. Other aspects of the intervention have been published elsewhere (Kobel et al. 2014, 2017, 2020).

For the programme’s development, the protocol-based planning model Intervention Mapping Approach (Bartholomew et al. 2006) was used. Bandura’s social-cognitive theory (Bandura 2001) and Bronfenbrenner’s socio-ecological approach (Bronfenbrenner 2012) form the theoretical frameworks for this intervention. Methods used in social cognitive theory (such as imparting knowledge, model learning, observing behaviour, reinforcing, promoting self-efficacy, presenting action alternatives, and setting goals (Bandura 2001)) were incorporated, as they are well suited to achieving changes in children’s health behaviours. The socio-ecological approach (Bronfenbrenner 2012), on the other hand, highlights the great importance of including the immediate environment, such as family and peer group, for the perpetuation of new behaviours. With the combination of both frameworks, measures towards behaviour as well as environmental change can be initiated (and possibly sustained).

Behaviour-oriented interventions such as this one aim to directly influence behaviour; the focus here is on the imparting of action, but also knowledge-oriented content (getting to know and trying out healthy foods, acquiring knowledge regarding preparation, origin, and significance for the human body). Relational interventions, on the other hand, start with direct everyday life and the environment (e.g., break sales, healthy breakfast together, supply of water). It is essential to combine both approaches, as there are gender-specific differences in their mode of action: girls are increasingly reached through the behaviour-oriented approach, boys through the relationship-oriented approach (Kropski et al. 2008).

Therefore, and to ensure sustainable health promotion, contents and materials were integrated into regular lessons of the primary school curriculum, which include behavioural contracting and budgeting but primarily the offer of action alternatives paired with knowledge. Classroom teachers delivered those lessons regularly for 1 year after taking part in a detailed training course.

Intervention materials are structured in a spiral curriculum, which means that contents are adapted to the respective level of children’s development and are repeatedly presented or deepened in different grades. In order to involve parents, parents’ letters and parents' evenings provide background knowledge and present action alternatives for a healthy diet (e.g., healthy midday snack ideas, the importance of drinking...). Additionally, family homework was introduced, which are regular tasks primary school children have to solve together with their parents. These tasks are aimed at shaping everyday family life and at transporting topics dealt with in class into the home environment and thus initiating changes in the children's immediate environment: in their own homes.

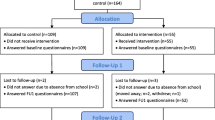

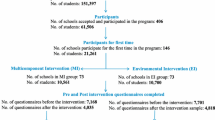

The evaluation of this intervention was designed as a prospective, stratified, cluster-randomised, and longitudinal study including intervention and control groups. After baseline measurements had been taken, the programme’s intervention was carried out in the intervention group, whereas the control group followed the regular school curriculum. Follow-up measurements were taken after 1 year. Details on teacher and pupil recruiting, teaching materials, and organisation of randomisation and stratification can be found elsewhere (Dreyhaupt et al. 2012). The study was approved by the University’s Ethics Committee and the Ministry of Culture and Education, and was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. The study was also registered at the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS-ID: DRKS00000949).

Participants and instruments

At baseline, 1943 primary school children (7.1± 0.6 years; 51.2% male) in 86 schools were assessed, and 1733 of them at follow-up again. In this investigation, children whose baseline and follow-up data was available as well as a defined migration background were included, resulting in 1564 children (7.1 ± 0.6 years; 50.0% male). Parents provided written, informed consent and children their assent to taking part in the study. Children’s anthropometrics were taken by trained technicians during a school visit (height and weight to ISAK standards (Stewart et al. 2011); Seca 213 and Seca 862, Seca Weighing and Measuring Systems, Hamburg, Germany). Children’s weight status was determined by body mass index (BMI) percentiles based on German reference values (Kromeyer-Hauschild et al. 2001). Cut-off points for overweight children were determined above the 90th percentile; for obese children above the 97th percentile.

Parents received and completed a questionnaire about the children’s health behaviours, including details on their children’s nutritional habits. In addition, parental anthropometric data and their socio-economic background were assessed. The included questions are based on a large German study (KiGGS) which assessed health behaviour in more than 45,000 children and adolescents (Kurth and Schaffrath Rosario 2010) (for more details: Dreyhaupt et al. 2012). Eighty-seven percent of parents returned the questionnaire at baseline and follow-up.

Data analysis

Baseline characteristics were analysed separately for intervention and control group for all the variables included in the analysis. Descriptive statistics for continuous variables were displayed in mean values and standard deviations. Categorical variables were described with absolute and relative frequencies. To determine the group differences, each beverage and food was transferred into a three-valued variable (for assessment of follow-up — baseline): value of 1 for increase in consumption, zero represents unchanged consumption, and −1 for reduced consumption of drink/food. Group differences were examined using chi2 or Fisher’s exact test with a two-sided significance level of α = 0.05. Within group changes for ordinal variables were determined with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. For further statistical analysis, all relevant variables were dichotomised. Parental data providing information on juice, soft drink, and sugar-sweetened tea consumption as well as the frequency of eating fruit and vegetables and snacks and sweets were dichotomised as “often/always” versus “never/rarely.” Subsequently, logistic regression analyses were carried out controlling for gender, age, migration background, parental education level, household income, parental overweight, and baseline values. The latter were dichotomised as follows: gender (male vs female), age (first grade vs second grade), migration background (at least one parent was born abroad or the child was spoken to in another language than German for the first 3 years of their life vs parents born in Germany), parental education level (primary and secondary education levels vs tertiary education level, i.e., high school degree), household income (net household income <1750 €/month vs ≥ 1750 €/month), and parental overweight (BMI ≤ 25 kg/m2 vs > 25 kg/m2). Analyses were carried out using SPSS Statistics 28 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, US).

Results

A summary of the participant’s baseline characteristics concerning socio-demographic and anthropometric details can be found in Table 1. The prevalence of overweight including obesity in this sample was 8.4%, and of obesity alone 3.4% of children.

Group comparison to check if the randomisation was successful revealed no differences between control and intervention group for all relevant variables with the exception of migration background, which was significantly higher in the intervention group (p = 0.004).

(Sugar-sweetened) beverages

Pure juice

At baseline, 15.5% of children drank regularly pure juice (13.7% vs 17.0% in control and intervention group respectively, p = 0.091), which was reduced significantly to 12.4% in the total sample (p ≤ 0.001; see Table 2). This reduction is mainly due to children in the intervention group decreasing their consumption of pure juices significantly by 5.5% (vs 0.2% in the control group; p ≤ 0.016). However, when analysed using logistic regression models, controlling for baseline values, gender, age, migration status, parental education level, household income, and parental overweight, this significance was lost (Table 3).

The described reduction in the consumption of pure juices was especially noticeable in children who are brought up by both parents (p = 0.007), from a household with a monthly income of less than € 1750 (p = 0.012), with a migration background (p = 0.015) and for children with a mother of normal weight (p = 0.020). Examining other subgroups (gender, grade, parental education level, father’s weight status), the decrease in consumption of pure juices was significant for the control group as well as the intervention group.

Children with a migration background in the intervention group showed the largest reduction of consumption of pure juices. At baseline, 29.2% of parents of children with migration background in the intervention group stated that their children regularly drink pure juices. At follow-up, this decreased to 20.2% (p = 0.004). In the control group, a slight, non-significant increase in consumption was observed at follow-up, compared to baseline (p = 0.480). In children without a migration background, the consumption of pure juices decreased slightly in both groups; however, no significance was reached (intervention: p = 0.061; control: p = 0.768).

Likewise, a reduction of pure juice consumption among children from households with low incomes could be observed. While in the intervention group 22.4% of children from households with low incomes consumed pure juices regularly at follow-up (32.9% at baseline; change from follow-up to baseline: −10.5%, p = 0.012), in the control group, 28.8% of children drank regularly pure juices at follow-up (20.5% at baseline, p = 0.061), resulting in an increase in the control group of 8.3% within a year.

Soft drinks

With regard to the change in consumption of lemonades and iced tea, no significant difference could be observed in either group (p = 0.414). At baseline, 15.1% of children consumed soft drinks regularly (15.5% vs 14.2% for intervention and control group respectively), which reduced slightly to 13.1% at follow-up for both groups. Therefore, a trend towards a reduction of soft drink consumption was seen more in the intervention group.

In spite of this, children with fathers of normal weight showed a significant reduction of soft drink consumption in the intervention group, compared to the control group (p = 0.025). Comparing the percentages of children who drink sugary lemonades and have a father of normal weight, it can be seen that the proportion of baseline to follow-up decreased in the intervention group (p = 0.083), while the control group recorded an increase in consumption for this period (p = 0.144). Yet, those changes do not reach significance.

A significant decrease can, however, be determined with a separate analysis of grades for first graders in the intervention group (p = 0.022). While at baseline 14.5% of children in first grade normally drank sugar-sweetened beverages, at follow-up 10.9% stated this. In the control group, a slight but non-significant increase could be observed (p = 0.752). For second graders, no significant change could be seen after 1 year in either intervention or control group (p = 0.793 and p = 0.612 respectively).

Sugar-sweetened tea

For sugar-sweetened tea, no significant changes can be seen for either group (intervention: p = 0.759; control: p = 0.798). If the groups are subdivided, a significant increase in consumption of sugar-sweetened tea can be seen in the control group for children from households with a monthly income of less than 1750 € (p = 0.029). However, if this subgroup is examined for changes between intervention and control group, changes remain non-significant (p = 0.616).

Fruit and vegetables, sweets, and snacks

Fruit and vegetables

At baseline, 18.7% of parents indicated their children eat fruit and vegetables never or rarely (19.2% vs 18.1% for intervention and control group respectively). At follow-up, these values changed slightly to 18.8% for the total sample, 18.6% and 19.1% for intervention and control group respectively (Table 4). No significant changes between intervention and control group were found in children’s fruit and vegetables consumption when comparing baseline and follow-up (p = 0.202). Additionally, analysed using logistic regression models, controlling for baseline values, gender, age, migration status, parental education level, household income, and parental overweight, no significance was found either (Table 5).

Nevertheless, significant differences were found for first graders (p = 0.050), children from families with a high parental education level (p = 0.023), and for children with an overweight father (p = 0.034). However, the proportion of children in the intervention group who never or rarely eat fruit and vegetables decreased from baseline to follow-up, whereas an opposite trend could be observed in children in the control group (see Table 4).

An isolated analysis of intervention and control group with regard to fruit and vegetable consumption does not reveal any significant change for either group (intervention: p = 0.441; control: p = 0.307).

However, considering children with migration background only, there is a significant change. While in the intervention group, for children with migration background, the proportion of those who never or only rarely eat fruit and vegetables decreased significantly from baseline to follow-up (p = 0.010), this remained constant for the control (p = 1.000). For German children, there was no significant change in either control or intervention group (p = 0.439 and p = 0.211, respectively).

In addition, in the control group, a significant reduction of the consumption of fruit and vegetables in the children of parents with a high school degree could be observed (p = 0.019). While at baseline, 12.0% of parents with a tertiary education level stated that their children would never or only rarely eat fruit and vegetables, at follow-up, 18.0% mentioned that. In the intervention group, this proportion decreased slightly, but not significantly, for the bespoke subgroup (p = 0.411)

Sweets and snacks

According to parental information, at baseline, 94.9% of children rarely or never consumed sweets or snacks while at school. At follow-up, no change in sweets and snacks’ consumption was seen between intervention and control group (p = 0.48; Table 4).

Discussion

The cluster-randomised effectiveness trial of a low-threshold, teacher-centred health promotion intervention shows that the intervention programme “Join the Healthy Boat” has a visible impact on the consumption of pure juices in children. In other aspects of nutritional behaviour examined, changes can only be ascribed to specific subgroups. In some of those groups, which are often assigned an increased risk of poor eating habits, particularly positive effects were seen; e.g., in children with migration background (pure juices), in children from households with a low income (pure juices), and in children with an overweight father (fruit and vegetables consumption).

In the 1-year intervention programme, this study evaluated and integrated nutrition education as well as alternatives to existing dietary habits into the school curriculum. It was aimed to improve not just children’s knowledge, attitudes, and eating behaviours, but also their parents’ attitudes and practices on nutrition among primary school children.

In the intervention group, a significant change in the consumption of pure juices in all children (without restriction to certain subgroups) could be recorded, which occurred most likely as a result of the intervention. Because of their high content of free sugars, pure juices are suspected of being associated with the development of excess body weight and obesity (Keller and Bucher Della Torre 2015), cardiovascular diseases (Yang et al. 2014) and increased risk of type 2 diabetes (Malik et al. 2010; Greenwood et al. 2014), as well as developing caries (Sheiham and James 2015). Therefore, the programme attaches great importance to parental involvement, who play a key role in children's eating habits (Schwartz et al. 2011). Parents are involved in the intervention programme via parents' nights, letters, and family homework. They are shown ways and measures to improve their children's eating habits, which they can also transfer to their own. Among other things, they are informed about pure juices and sugar-sweetened beverages, and how they should be substituted. In training courses, teachers were encouraged to make regular drinking breaks during their lessons, to set up classroom rules as to which drinks to bring from home, and received ideas to animate children to drink more water (in order to drink fewer sugar-sweetened beverages). Methods such as the bespoke were used in an intervention study in the Netherlands in which primary school children reduced their sugar-sweetened beverages consumption within the space of 1 year (van de Gaar et al. 2014).

In this study, although drinking behaviour improved in all age-groups, the analysis of subgroups shows that the reduction of pure juice applies especially to children in second grade, children brought up by both parents, from a family with low household income or a migration background, and for children with a normal weight mother. In order to avoid inequality, methods should therefore be adapted so all children and parents (in this case especially single and overweight parents) can be reached in future. Reducing pure juice consumption among children with a migration background is particularly gratifying because those tend to have unfavourable eating habits more often than German children (Mensink et al. 2007). So far, however, the relative consumption of pure juices between children with and without migration background has been insufficiently researched. For example, the national Germany health survey KiGGS included juice spritzers in its question category on the consumption of juices, which led the researchers to the conclusion that children of German origin drink more juice than children with migration background (Mensink et al. 2007b). In contrast, however, the results of this study show that pure juices are more than twice as likely to be regularly consumed by children with migration background compared to German children. This gap was reduced after 1 year of intervention. In the control group at follow-up, three times as many children with migration background consumed pure juices compared to children without a migration background. Yet, it can be seen that despite the reduced number of children with migration background in the intervention group at follow-up compared to baseline, the proportion of regular juice consumers compared to children of German origin is still more than twice as high at follow-up. Because even children without a migration background were able to benefit from the intervention programme, this also reduced their consumption of pure juices after one year of intervention.

Apart from a reduction in pure juice consumption, children with a father of normal weight consumed a lower level of lemonades and iced tea, which is very likely a consequence of the intervention. Apparently, fathers’ weight status plays a subordinate role, which could possibly be due to the fact that fathers in particular offer their children bespoke drinks more often than mothers, as these are also more often consumed by men themselves (Max Rubner Institute and Federal Research Institute for Nutrition and Food 2008). It is well known that the responsibility for children’s food choices falls to parents as key food-socialisation agents (Moore et al. 2017), who serve as role models for children to observe and imitate. Therefore, “Join the Healthy Boat” offers thought-provoking impulses for parents in order to reflect their own behaviours. Possibly, there are more intense methods needed to reach all parents.

In addition to the above-mentioned intervention results with regard to sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit and vegetable consumption in children in first grade, children with at least one academic parent, and children with an overweight father were positively affected by the intervention. Fruit and vegetables provide the body with plenty of nutrients, fibre, and secondary plant substances, which is why they should be consumed at least five times a day. Frequent consumption of fruit and vegetables is associated with a reduction of overweight and obesity (Schlesinger et al. 2019) and the prevention of weight gain (Boeing et al. 2012), as well as a reduced risk for the development of hypertension (Schwingshackl et al. 2017) and it also has a blood pressure-lowering effect (Boeing et al. 2012). For these reasons, “Join the Healthy Boat” aims to increase children’s regular fruit and vegetable intake.

In this sample, 18.8% of children ate fruit and vegetables never or rarely. The German Survey of Children’s Health (KiGGS) was able to show that 17.2% of girls and 15.5% of boys aged 3–10 years eat five portions of fruit and vegetables per day; most of the children (50.7% and 51.3% for girls and boys respectively) in that age group, however, eat one or two portions of fruit and vegetables per day; 7.3% and 8.5% for girls and boys respectively eat no fruit or vegetables (Krug et al. 2018). In this study, comparing age groups, only children in first grade increased their consumption of fruit and vegetables. This could possibly be related to the different intervention topics addressed in lessons of grades one and two. While fruit and vegetables are explicitly discussed as a lesson topic in first grade, they play a subordinate role in second grade. The parental letter on healthy snacks at school is also only sent to parents of first graders, so that these parents may pay more attention to a healthy second breakfast at school. Moreover, an increase of fruit and vegetable intake could only be achieved in children with at least one academic parent and among children with overweight fathers. However, it should be noted that children without an academic parent also ate more fruit and vegetables at follow-up. It must also be taken into account that the proportion of children who never or only rarely eat fruit and vegetables (12% at baseline) is much lower than in the comparison groups (Krug et al. 2018). Possibly, a socially desirable response behaviour must be assumed.

Also, a more intense and more encouraging intervention might have been benefited all children more, with regard to an increase in their fruit and vegetables consumption. A study in ten primary schools across five European countries was able to record an increase in children’s fruit and vegetables intake after a 6-week intervention, using motivational incentives (Gwozdz et al. 2020). Children were encouraged to choose a more healthy side option and rewarded that with a smiley stamp every time (Gwozdz et al. 2020). Children in the intervention group chose significantly more often fruit and vegetables than those in the control group, even when school differences were accounted for (Gwozdz et al. 2020). The authors conclude, therefore, that a motivational incentive can increase primary school children’s fruit and vegetables consumption (Gwozdz et al. 2020). In “Join the Healthy Boat”, such motivational incentives were used for the sufficient amount of daily water consumption (drink diary), the increase of physical activity (stamp card for an active transport to school, data not shown), and a reduction of screen media use (reward for an active, non-screen day, data not shown).

Further, the consumption of snacks and sweets did not change, either in intervention or control group. No more than 10% of the total energy should be absorbed from these foods, including sugar-sweetened drinks, cakes, and the like, as these are declared unhealthy due to their high-energy content but low nutrient density (Mensink et al. 2007a). However, almost all children take in more energy from these foods than recommended (Richter et al. 2007), which does not represent this data, where parents stated that nearly 95% of their children never or rarely eat sweets, candy, or snacks. Therefore, it is very possible that parents demonstrated a socially desirable response behaviour and data were distorted. Then again, “Join the Healthy Boat” showed no effect on the children's snack and sweets consumption.

Although this study has a large sample size, which increases the likelihood of having sufficient power to detect intervention effects, some aspects should be considered when interpreting these findings. One of the study's major strengths is the large sample size and the fact that it received data from all of the south-west of Germany. The response rate for the parental questionnaire was exceptionally high at 87%. In addition, the longitudinal design, with its randomised control group, through which different development paths of subgroups could be recorded, is another advantage of this study. However, the study also has its limitations. Participation in the study was voluntary, possibly resulting in certain children not being taken into account due to language or social barriers. It is also likely that mainly committed teachers and parents interested in the topic took part in the study. In addition, subjective data assessed via a questionnaire always carries the risk that socially desirable response behaviour leads to a distortion of results. Additionally, intervention programmes that may have taken place in parallel (such as the European School Fruit, Vegetables, and Milk Scheme) in both the intervention and the control group may have shown different effects on the nutritional behaviour of the children, which could also have distorted the data. In addition, parental nutritional behaviour was not assessed in this study, which should be taken into account in future studies. A more intense intervention and possibly a different time of assessment (baseline and follow-up measurements were taken directly after a 7-week summer break) may have resulted in different outcomes, but it should be noted that effects of health promotion are usually not detected in a short time frame such as the one of the present evaluation study. “Join the Healthy Boat” covers the entire period of primary school of 4 years. In contrast, the corresponding study could only investigate 1 year because the control group could not be denied the intervention any longer. Moreover, according to a microsimulation model, health gains from interventions targeting children occur in the long term (Cecchini et al. 2010).

Conclusion

As shown, intervention programmes in the field of nutrition are particularly important in today's world in order to help children lead a more favourable way of life. With the intervention programme “Join the Healthy Boat”, a positive reduction in the consumption of pure juices could be achieved among the participating children. Furthermore, it could be shown that “Join the Healthy Boat” can positively affect children of certain subgroups, who are said to have an increased risk of poor eating habits. Above all, these are children with a migration background, in whom an improvement was evident in drinking pure juices and eating more fruit and vegetables.

In addition, for children with an overweight parent and for children from a household with low income, a favourable change in aspects of nutritional behaviour could be achieved. However, no change was seen in children of single parents and children whose parents do not have a high school degree. In addition, it became apparent that children in first grade or their parents were able to benefit more from the intervention programme and were more likely to change aspects of their nutritional behaviour than those in second grade.

However, the programme shows weaknesses in the consumption of snacks and sweets. “Join the Healthy Boat” does, however, seem to appeal to a wider group of children and thus rather balances out differences related to origin. Nevertheless, it is important to continue to improve the programme in future through constant evaluation in order to reach as many children as possible and their parents, so that a generally healthier way of life can be achieved. As has been shown, there is still a need for research in some aspects in order to be able to close the identified gaps in the collection and evaluation of the data and to provide further information about the nutritional behaviour of children.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Armfield JM, Spencer AJ, Roberts-Thomson KF et al (2013) Water fluoridation and the association of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and dental caries in Australian children. Am J Pub Health 103(3):494–500

Bandura A (2001) Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol 52:1–26

Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G et al (2006) Planning health promotion programs: an intervention mapping approach. Jossey–Bass, San Francisco, pp 191–472

Boeing H, Bechthold A, Bub A et al (2012) Critical review: vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases. Eur J Nutr 51:637–663

Borrmann A, Mensink G (2015) Obst- und Gemüsekonsum von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland [Consumption of fruit and vegetables by children and adolescents in Germany]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforscung Gesundheitsschutz 58:1005–1014

Bronfenbrenner U (2012) Ökologische Sozialisationsforschung. Ein Bezugsrahmen. In: Bauer U, Bittlingmayer U, Scherr A (eds) Handbuch Bildungs- und Erziehungssoziologie [Handbook of sociology of education]. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, pp 167–176

Cecchini M, Sassi F, Lauer JA, Lee YY, Guajardo-Barron V, Chisholm D (2010) Tackling of unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, and obesity: health effects and cost-effectiveness. Lancet 376(9754):1775–1784

de Koning L, Malik VS, Kellogg M, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB (2012) Sweetened beverage consumption, incident coronary heart disease, and biomarkers of risk in men. Circulation 125:1735–1741

Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (2020) Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/ScientificReport_of_the_2020DietaryGuidelinesAdvisoryCommittee_first-print.pdf. Accessed 25 November 2021

DiGirolamo AM, Ochaeta L, Flores RMM (2020) Early childhood nutrition and cognitive functioning in childhood and adolescence. Food Nutr Bull 41(1):31–40

Dreyhaupt J, Koch B, Wirt T, Schreiber A, Brandstetter S, Kesztyüs D et al (2012) Evaluation of a health promotion program in children: study protocol and design of the cluster-randomized Baden-Wuerttemberg primary school study [DRKS-ID: DRKS00000494]. BMC Pub Health 12(1):157

Drouin-Chartier JP, Zheng Y, Li Y, Malik V, Pan A, Bhupathiraju SN, Tobias DK, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB (2019) Changes in consumption of sugary beverages and artificially sweetened beverages and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes: results from three large prospective U.S. cohorts of women and men. Diabetes Care 42:2181–2189

Evans CEL (2017) Sugars and health: a review of current evidence and future policy. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 76:400–407

Fung TT, Malik V, Rexrode K, Manson J, Willett WC, Hu FB (2009) Sweetened beverage consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Am J Clin Nutr 89:1037–1042

Golpour-Hamedani S, Rafie N, Pourmasoumi M, Saneet P, Safavi SM (2020) The association between dietary diversity score and general and abdominal obesity in Iranian children and adolescents. BMC Endocr Disord 20(1):181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-020-00662-w

Graffe MIM, Pala V, De Henauw S et al (2020) Dietary sources of free sugars in the diet of European children: the IDEFICS Study. Eur J Nutr 59:979–989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-01957-y

Greenwood DC, Threapleton DE, Evans CE, Cleghorn CL, Nykjaer C, Woodhead C, Burley VJ (2014) Association between sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened soft drinks and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br J Nutr 112(5):725–734. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114514001329

Gwozdz W, Reisch L, Eiben G, Hunsberger M, Konstal K, Kovacs E et al (2020) The effect of smileys as motivational incentives on children’s fruit and vegetable choice, consumption and waste: a field experiment in schools in five European countries. Food Policy 96:101852

Keller A, Bucher Della Torre S (2015) Sugar-sweetened beverages and obesity among children and adolescents: a review of systematic literature reviews. Child Obes 11(4):338–346. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2014.0117

Kobel S, Wirt T, Schreiber A, Kesztyüs D, Kettner S, Erkelenz N, Wartha O, Steinacker JM (2014) Intervention effects of a school-based health promotion programme on obesity related behavioural outcomes. J Obes 2014:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/476230

Kobel S, Lämmle C, Wartha O, Kesztyüs D, Wirt T, Steinacker JM (2017) Effects of a randomised controlled school-based health promotion intervention on obesity related behavioural outcomes of children with migration background. J Immigr Minor Health 19(2):254–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0460-9

Kobel S, Kesztyüs D, Steinacker JM (2020) Lehrerbasierte Gesundheitsförderung bei Grundschulkindern in Baden-Württemberg: Effekte auf Ausdauerleistungsfähigkeit und Inzidenz abdominaler Adipositas. Das Gesundheitswesen 82(11):901–908. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0921-7076

Kovács E, Siani A, Konstabel K et al (2014) Adherence to the obesity-related lifestyle intervention targets in the IDEFICS Study. Int J Obes 38:144–151. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.145

Kromeyer-Hauschild K, Wabitsch M, Kunze D, Geller F, Geiß HC, Hesse V et al (2001) Perzentile für den Body-mass-Index für das Kindes- und Jugendalter unter Heranziehung verschiedener deutscher Stichproben [Percentiles of body mass index in children and adolescents evaluated from different regional German studies]. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 149:807–818

Kropski JA, Keckley PH, Jensen GL (2008) School-based obesity prevention programs: an evidence-based review. Obesity 16(5):1009–1018

Krug S, Finger JD, Lage C, Richter A, Mensink GBM (2018) Sport- und Ernährungsverhalten bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland — Querschnittsergebnisse aus Welle 2 und Trends [Sports and eating behaviour among children and adolescents in Germany — cross-sectional results from wave 2 and trends]. J Health Monitor 3(2):3–22

Kurth BM, Schaffrath Rosario A (2010) Übergewicht und Adipositas bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland [Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents in Germany]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 53:643–652

Louie JC (2020) Objective biomarkers for total added sugar intake—are we on a wild goose chase? Adv Nutr 11:1429–1436

Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després JP, Willett WC, Hu FB (2010) Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 33(11):2477–2483

Max Rubner Institute and Federal Research Institute for Nutrition and Food (2008) Nationale Verzehrs Studie II. Ergebnisbericht, Teil 1. Die bundesweite Befragung zur Ernährung von Jugendlichen und Erwachsenen [National Consumption Study II. Results report, part 1. The nationwide survey on the nutrition of adolescents and adults]. Max Rubner Institute,Karlsruhe. https://www.bmel.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/_Ernaehrung/NVS_Ergebnisbericht.pdf;jsessionid=7F52488906BAA02B129D0E1209B524B1.live842?__blob=publicationFile&v=2. Accessed 25 November 25 2021

Mensink GBM, Heseker H, Richter A, Stahl A, Vohmann C (2007a) Ernährungsstudie als KiGGS-Modul (EsKiMo). Forschungsbericht. [Nutrition study as KiGGS Module (EsKiMo). Research Report]. Bundesministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Verbraucherschutz [Federal Ministry for Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection] Referat 22, Bonn

Mensink GBM, Kleiser C, Richter A (2007b) Lebensmittelverzehr bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Ergebnisse der Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurveys (KiGGS) [Food consumption among children and adolescents in Germany. Results of the child and adolescent health survey (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 50(5/6):609–623. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-007-0222-x

Mensink GBM, Schienkiewitz A, Rabenberg M, Borrmann A, Richter A, Haftenberger M (2018) Consumption of sugary soft drinks among children and adolescents in Germany. Results of the cross-sectional KiGGS Wave 2 study and trends. J Health Monitoring 3(1):31–37

Moore ES, Wilkie WL, Desrochers DM (2017) All in the family? Parental roles in the epidemic of childhood obesity. J Consumer Res 43(5):824–859

Nicklaus S (2016) The role of food experiences during early childhood in food pleasure learning. Appetite 104:3–9

Perrar I, Schmitting S, Della Corte KW, Buyken AE, Alexy U (2019) Age and time trends in sugar intake among children and adolescents: results from the DONALD study. Eur J Nutr 59:1043–1054

Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Borghese MM, Carson V, Chaput JP, Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Pate RR, Connor Gorber S, Kho ME et al (2016) Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 41(6 Suppl 3):197–239

Qin P, Li Q, Zhao Y, Chen Q, Sun X, Liu Y, Li H, Wang T, Chen X, Zhou Q et al (2020) Sugar and artificially sweetened beverages and risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and all-cause mortality: A dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol 35:655–671

Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM (2010) Dietary sources of energy, solid fats, and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc 110(10):1477–1484

Richter A, Vohmann C, Stahl A, Heseker H, Mensink GBM (2007) Der aktuelle Lebensmittelverzehr von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Teil 2: Ergebnisse aus EsKiMo [The current food consumption of children and adolescents in Germany. Part 2: Results from EsKiMo]. Ernährungs Umschau 55(1):28–36

Romaguera D, Norat T, Wark PA et al (2013) Consumption of sweet beverages and type 2 diabetes incidence in European adults: results from EPIC-InterAct. Diabetologia 56(7):1520–1530

Schienkiewitz A, Brettschneider AK, Damerow S, Schaffrath Rosario A (2018) Overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in Germany. Results of the cross-sectional KiGGS Wave 2 study and trends. J Health Monitoring 3(1). https://doi.org/10.17886/RKI-GBE-2018-022

Schlesinger S, Neuenschwander M, Schwedhelm C et al (2019) Food groups and risk of overweight, obesity, and weight gain: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Adv Nutr 10:205–218

Schneider S, Mata J, Kadel P (2020) Relations between sweetened beverage consumption and individual, interpersonal, and environmental factors: a 6-year longitudinal study in German children and adolescents. Int J Public Health 65(5):559–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01397-0

Schönbach J, Lhachimi S (2021) To what extent could cardiovascular diseases be reduced if Germany applied fiscal policies to increase fruit and vegetable consumption? A quantitative health impact assessment. Pub Health Nutr 24(9):2570–2576. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020000634

Schwartz C, Scholtens P, Lalanne A, Weenen H, Nicklaus S (2011) Development of healthy eating habits early in life: review of recent evidence and selected guidelines. Appetite 57:796–807

Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G et al (2017) Food groups and risk of hypertension: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Adv Nutr 8:793–803

Sheiham A, James WP (2015) Diet and dental caries: the pivotal role of free sugars reemphasized. J Dent Res 94(10):1341–1347

Stewart A, Marfell-Jones M, Olds T, de Ridder H (2011) International standards for anthropometric assessment. ISAK, Lower Hutt, New Zealand

van de Gaar VM, Jansen W, van Grieken A, Borsboom GJJM, Kremers S, Raat H (2014) Effects of an intervention aimed at reducing the intake of sugar-sweetened beverages in primary school children: a controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-014-0098-8

Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ et al (2011) Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011(12):CD001871. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub3

Yang Q, Zhang Z, Gregg EW, Flanders WD, Merritt R, Hu FB (2014) Added sugar intake and cardiovascular diseases mortality among US adults. JAMA Intern Med 174(4):516–524

Acknowledgements

The school-based health promotion programme “Join the Healthy Boat“ and its evaluation study was financed by the Baden-Württemberg Foundation, which had no influence on the content of this manuscript.

Further, the authors would like to thank all members of the research group for their input: the Institute of Epidemiology and Medical Biometry, Ulm University, the Institute of Psychology and Pedagogy, Ulm University, all assistants who were involved in the performance of measurements, and especially all teachers and families for their participation.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The school-based health promotion programme “Join the Healthy Boat“ and its evaluation study was financed by the Baden-Württemberg Foundation, which had no influence on the content of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Susanne Kobel, Olivia Wartha, and Jürgen M Steinacker contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Susanne Kobel, Olivia Wartha, and Katie E Feather. Analyses were performed by Susanne Kobel, Katie E Feather, and Jens Dreyhaupt. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Susanne Kobel, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ulm University (126/10), the Ministry of Culture and Education, and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Parents provided written, informed consent and children their assent to taking part in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kobel, S., Wartha, O., Dreyhaupt, J. et al. Intervention effects of a school-based health promotion programme on children’s nutrition behaviour. J Public Health (Berl.) 31, 1747–1757 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-022-01726-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-022-01726-y