Abstract

This paper shows that in a two-country two-overlapping-generations model with migration, capital mobility and an immobile production factor (land), a locally welfare-improving pension reform at the cost of the neighboring country is possible if land plays a minor role in production. Furthermore, differences in the size of the PAYG pension schemes between the countries distort the international allocation of labour and capital. As a result, a Pareto-improving pension reform is possible if countries employ PAYG pension schemes of different size, provided that a federal government exists that redistributes benefits and losses of the reform both intergenerationally and internationally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Or if the PAYG tax in both countries is lowered to a level below that in the country with the smallest PAYG scheme.

The utility function U t (· , ·) is assumed to be strictly increasing in both arguments.

Note that the assumption that labour supply is inelastic implies that the PAYG tax does not cause a distortion on the labour market. Hence, the assumption that the PAYG scheme provides a flat benefit instead of an earnings-related benefit is not important for our results.

These assumptions simplify the analysis as they eliminate short-run dynamics. Alternatively one could assume that the two countries form a closed economy or that financial capital (savings) is mobile but that once it is invested capital is not mobile any more. This would change the dynamics, but numerical simulation experiments show that it does not qualitatively affect the main results derived.

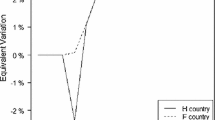

The illustration is based on a numerical simulation experiment assuming a logarithmic utility function: \(U_t=\log c_{t}^y+\frac {1}{1+\rho }\log c_{t+1}^{o} \) The parameters are set at values often used in the literature, or close to them (see for example Börsch-Supan et al. (2006), Ambler and Cardia (1998), and İmrohoroǧlu et al. (1999): α = 0. 3, β = 0. 65, ρ = 0. 4166 which approximately corresponds to 1 % annual discount rate. Initially, the tax rate in both countries is the same: \(\tau = \tilde {\tau }=0.25\). The interest rate on the world capital market is set at such a level that capital in both countries can exactly be financed from savings in these countries. At t = 0 the tax rate in the home country is reduced from τ = 0. 25 to τ = 0. 20

We use the term “globally welfare-improving reform” to indicate that all agents in both countries under consideration gain (or at least do not loose).

In general, PAYG contribution rates can be equalized to zero.

References

Adema Y, Meijdam AC, Verbon HAA (2009) The international spillover effects of pension reform. Int Tax Public Financ 16:670–696

Ambler S, Cardia E (1998) The cyclical behaviour of wages and profits under imperfect competition. Can J Econ 31(1):148–164

Börsch-Supan A, Ludwig A, Winter J (2006) Ageing, pension reform, and capital flows: a multicountry simulation model. Economica 73(292):625–658

Bräuninger D (2010) Pensions in a post-crisis world. Fully-funded provision is vital. Deut Bank Res

Breyer F (1989) On the intergenerational Pareto efficiency of pay-as-you-go financed pension systems. J Inst Theor Econ 145:643–658

Breyer F, Kolmar M (2002) Are national pension systems efficient if labor is (im)perfectly mobile? J Public Econ 83:347–374

Broadbent J, Palumbo M, Woodman E (2006) The shift from defined benefit to defined contribution pension plans—implications for asset allocation and risk management. Available on web: http://www.bis.org

Buškutė I, Medaiskis T (2011) Balancing the security and affordability of funded pension schemes: statements and comments. Paper presented at the Peer Review of the Netherlands Pension System. Hague, April 12–13

De Giorgi G, Pellizzari M (2009) Welfare migration in Europe. Labour Econ 16(4):353–363

Feehan JP, Batina RG (2007) Labor and capital taxation with public inputs as common property. Public Finance Rev 35(5):626–642

Fehr H, Jokisch S, Kotlikoff S (2003) The developed world’s demographic transition: the roles of capital flows, immigration and policy. NBER working paper series. Working paper No. 10096

Fenge R, Schwager R (1995) Pareto-improving transition from a pay-as-you-go to a fully funded pension system in a model with differing earning abilities. Z Wirtsc Sozialwiss 115:367–376

Geide-Stevenson D (1998) Social security policy and international labor and capital mobility. Rev Int Econ 6(3):407–416

Hange U (2000) Unfunded public pensions in the presence of perfect household mobility. Finanzarchiv 57(1):77–88

Haupt A, Peters W (1998) Public pensions and voting on immigration. Public Choice 95(3–4):403–413

Homburg S, Richter WF (1993) Harmonizing public debt and public pension schemes in the european community. J Econ Zeltschrift für Nationalökonomie 146:54–63

İmrohoroǧlu A, İmrohoroǧlu S, Joines D (1999) Social security in an overlapping generations economy with land. Rev Econ Dyn 2:638–665

Kemnitz A (2008) Can immigrant employment alleviate the demographic burden? The role of union centralization. Econ Lett 99:123–126

Kolmar M (2007) Beveridge versus Bismarck public pension systems in integrated markets. Reg Sci Urban Econ 37(6):649–669

Köthenbürger M, Poutvaara P (2006) Social security reform and investment in education: is there scope for a Pareto improvement?Economica 73:299–319

Krieger T (2001) Intergenerational redistribution and labour mobility: a survey. Finznzarchiv 58(3):339–361

Krieger T (2003) Voting on low-skill immigration under different pension regimes. Public Choice 117(1–2):51–78

Krieger T (2004) Fertility rates and skill distribution in Razin and Sadka’s migration-pension model: a note. J Popul Econ 17(1):177–182

Kunce M, Shogren JF (2007) Destructive interjurisdictional competition: firm, capital and labor mobility in a model of direct emission control. Ecol Econ 60:543–549

Lacomba JA, Lagos F (2010) Immigration and pension benefits in the host country. Economica 77:283–295

Leers T, Meijdam L, Verbon H (2003) Ageing, migration and endogenous public pensions. J Public Econ 88:131–159

Poutvaara P (2007) Social security incentives, human capital investment and mobility of labor. J Public Econ 91:1299–1325

Raudla R, Staehr K (2003) Pension reforms and taxation in Estonia. Baltic J Econ 4(1):64–92

Razin A, Sadka E (1999) Migration and pension with international capital mobility. J Public Econ 74:141–150

Rhee C (1991) Dynamic inefficiency in an economy with land. Rev Econ Stud 58:791–797

Vasile V, Zaman G (2005) Romanias pension system; between present restrictions and future exigencies. PIE Discussion Paper Series

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We are grateful to the anonymous referees of this journal for their useful comments. Furthermore, we would like to thank Bas van Groezen and the participants of the Netspar International Pension Workshop (June 16–17, 2011, Turin) for comments and discussion.

Appendix

Appendix

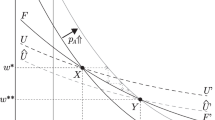

Lifetime income, i.e., the present value of an agent’s total income, is \(w_{t}(1-\tau )+(1+n_t)w_{t+1}\tau /(1+\bar {r})\). Using the fact that there is no migration in equilibrium ( n t = 0) and the wages are constant ( w t = w t + 1 ≡ w) lifetime income may be written as \(w(1+r-\tau \bar {r})/(1+\bar {r})\). As a higher lifetime income is equivalent to a higher utility, (this follows from the assumption, that utility function is strictly increasing in both arguments) perfect labour mobility implies:

Using (29), Eq. 30 can be rewritten as

Equation 10 then immediately follows. Equation 11 can be derived by inserting Eq. 10 into (29).

1.1 Proof of lemma 1

Proof

The equality of utilities is equivalent to the equality of present values of lifetime income, so:

Substituting w t and \(\tilde w_{t}\) from Eq. 2 and using Eqs. 3 and 7 to eliminate capital we can rewrite this as:

If L t + 1 = L t , then the system is in its steady state. Suppose that this is not the case. Write L t = L s + ΔL t , where L s is a steady state and ΔL t is a deviation from the steady state. Then \(\tilde L_{t}=\tilde L_{s}-\Delta L_{t}\), where \(\tilde L_s=\Lambda -L_{s}\). Rewrite Eq. 33

All values except ΔL t and ΔL t + 1 in Eq. 34 are constant, and the equation holds for ΔL t = ΔL t + 1 = 0. Suppose ΔL t > 0. Then Ψ 1 and Ψ 3 decrease and \(\tilde \Psi _{1}\), \(\tilde \Psi _{3}\) grow comparing to the equilibrium values. In order to keep the equality Ψ 2 shall grow and/or \(\tilde \Psi _{2}\) shall decrease. This is possible only if ΔL t + 1 is larger than ΔL t . Hence, at time t + 1 the deviation from the equilibrium values is even larger. Similarly ΔL t < 0 leads to a smaller ΔL t + 1, implying that the equilibrium in the model is a saddle point equilibrium. □

1.2 Continuity of consumption

Since, we are interested in parameter values α + β ≤ 1 only the continuity of consumption from below will be shown.

Lemma 2

Suppose conditions of lemma 1 are satisfied. Then the steady-state consumptions c o, c yare continuous from below in α and β at the points α + β = 1.

Proof

Consider Eqs. 9 and 10. In lemma 1 we suppose that \(\tau <\tilde \tau \), then L(α, β) = Λ if α + β = 1. Choose increasing sequences α k and β k , α k → α, β k → β when k → ∞. It is obvious that l i m k → ∞ L(α k , β k ) = Λ = L(α, β). Hence, labour in the home country is continuous on α and β from below at the point α + β = 1. Equation 13 then implies that wages are a continuous function of α and β. □

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fedotenkov, I., Meijdam, L. Pension reform with migration and mobile capital: is a Pareto improvement possible?. Int Econ Econ Policy 11, 431–450 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-013-0259-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-013-0259-2