Abstract

Objective

To retrospectively compare the long-term clinical, functional, and cost outcomes for early RA patients (symptoms < 1 year) who did or did not achieve early remission in a treat-to-target strategy.

Method

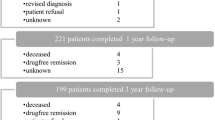

Five-year data of 471 patients included in the DREAM remission induction cohort were used. Patients were treated according to a pre-specified 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) remission driven step-up treatment strategy starting with methotrexate, addition of sulfasalazine, and exchange of sulfasalazine for biological medication in case of failure. Two- and 3-year healthcare costs were available for selected subsamples of patients only.

Results

DAS28 remission was achieved in 27.7%, 38.2%, and 51.6% of patients at 2, 3, and 6 months, respectively. Achieving DAS28 remission at 2, 3, or 6 months was consistently associated with significantly lower DAS28 and Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability scores at 1, 3, and 5 years of follow-up (all P values < 0.02). Patients in remission at 2, 3, or 6 months also had significantly lower medication costs per patient over the first 2 and 3 years of treatment, mainly due to lower biologic use, but differences in total healthcare resource costs (hospital admissions plus consultations) were less pronounced. Mean total medication and total healthcare resource costs at 3 years were €1131 and €1757 for patients in remission at 6 months vs. €7533 (P < 0.01) and €2202 (P = 0.09) for those not in remission.

Conclusion

Achieving early remission was associated with beneficial clinical outcomes for early RA patients and lower costs in the long term.

Key Points • Previous studies in rheumatoid arthritis patients have demonstrated that early good response is associated with sustained remission and better long-term clinical outcomes. • This study extents these findings by examining the long-term benefits of achieving early remission on clinical, patient-reported, and economic outcomes in a real-world cohort of patients with very early rheumatoid arthritis treated according to treat-to-target principles. • The findings of this study clearly demonstrate that aiming for early remission in rheumatoid arthritis patients is beneficial in the long-term in terms of better clinical and functional outcomes and lower healthcare costs |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Early diagnosis with prompt initiation of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), tight control monitoring of disease activity, and treatment adjustments aiming at the target of clinical remission, or at least low disease activity, is currently considered the standard of care in the management of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [1]. Clinical trials have provided consistent evidence that this so-called treat-to-target (T2T) strategy results in superior clinical outcomes compared with routine care and enhances long-term functional and quality of life outcomes [2, 3]. More recently, observational cohort studies have demonstrated that implementation of T2T is also realistic in daily clinical practice [4,5,6] and results in improved short- and long-term outcomes, similar to those found in clinical trials [7].

Despite these promising results, the effects of T2T vary among patients [8] and a relevant proportion of patients may still experience poor long-term outcomes [2]. Unfortunately, not much is currently known about factors associated with good long-term outcomes. One of these factors may be the time needed to achieve remission. Previous studies in early RA patients receiving different treatments have repeatedly found that early good response or remission was associated with sustained remission [9, 10], better long-term clinical and radiographic outcome [11, 12], and even decreased all-cause mortality [13]. This is consistent with the “window of opportunity” concept, which suggests that the long-term disease process can be altered by early successful disease control [14].

With the exception of the study by Bakker et al. [12], however, these studies were not performed specifically in “true” early RA patients already being treated to the target of remission. Moreover, the long-term benefits of achieving early remission in terms of patient-reported outcomes and actual costs in real-world T2T settings in this population are still unknown. Finally, previous studies have not explored if rapidity to achieve early remission (e.g., achieving remission within 2 months vs. 6 months) matters in the long term. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to, retrospectively, compare the long-term clinical, functional, and cost outcomes for early RA patients who did or did not achieve early remission in a real-world treat-to-target strategy.

Methods

Data selection and study design

Data were used from early RA patients included in the observational, multicenter Dutch RhEumatoid Arthritis Monitoring (DREAM) remission induction cohort [4, 5, 7]. In this observational, multicenter T2T strategy study, adult patients with a clinical diagnosis of RA (made by an experienced rheumatologist) were included if they had a symptom duration (time from the first reported symptom to the diagnosis of RA) ≤ 1 year, at least moderate disease activity (28-joint Disease Activity Score using erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) ≥ 2.6) [15] and had not previously received DMARDs and/or prednisolone. Patients were included at the time of the clinical diagnosis and started T2T immediately. The remission induction cohort study is registered in the Dutch trial register (NTR578).

Patients were recruited in this cohort from January 2006 until 2012, and follow-up is still ongoing. For the current retrospective study, patients with at least 5 years of follow-up data at the time of analysis (i.e., patients that were included before September 2010) were selected. Healthcare resource usage costs were available for a subset of patients for whom these data were collected as part of a previous study [16]. These data were collected over the first 2 years of treatment for some patients (n = 257) and the first 3 years for other patients (n = 124), depending on the time of inclusion in the study.

Treat-to-target protocol

Patients were treated to the target of remission using a step-up medication scheme (Fig. 1). Remission was defined as DAS28-ESR < 2.6. Patients were evaluated at baseline and after 8, 12, 20, 24, 36, and 52 weeks and every 3 months thereafter. Medication strategy advised adjustments of DMARDs based on the DAS28-ESR, with intensification of treatment if the predefined targets had not been met. The first step was starting methotrexate (MTX) monotherapy in a weekly dose of 15 mg. The dosage was increased to 25 mg/week in week 8 in case of insufficient response (DAS28-ESR ≥ 2.6). Prescription of folic acid was advised weekly at least 24 h after MTX intake. In case of uncontrolled disease activity (DAS28-ESR ≥ 2.6) in week 12, sulfasalazine (SSZ) was added, starting at a dosage of 2000 mg/day and if necessary increased to 3000 mg/day at week 20. In accordance with the national reimbursement guidelines at the time of the study, which required RA patients to have at least moderate disease activity for initiation of biologic treatment, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) treatment was prescribed at week 24 or later, when remission or low disease activity was not met (DAS28-ESR remained ≥ 3.2). In these cases, SSZ was replaced with subcutaneous administration of 40 mg of adalimumab biweekly. At week 36, the frequency of TNFi was increased to adalimumab 40 mg/week for patients with DAS28-ESR ≥ 2.6. At 1 year, or later when applicable, adalimumab was exchanged for etanercept 50 mg/week for patients with DAS28 ≥ 3.2. If at any time point, the target of DAS28-ESR < 2.6 was reached, medication was left unchanged. In the case of sustained remission (DAS28 < 2.6 for ≥ 6 months), medication was tapered and eventually stopped [17]. In the case of a disease flare (DAS28 ≥ 2.6), the last effective medication or medication dose was prescribed again and treatment could subsequently be intensified if necessary at the discretion of the attending rheumatologist. Obviously, deviations of this strategy were allowed in individual patients with contraindications for specific drugs, although adherence to the treatment strategy as observed was overall very high [18]. Concomitant treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, prednisolone at a dosage of ≤ 10 mg/day, and intra-articular corticosteroid injections was permitted.

Assessments

Patients were evaluated at the outpatient rheumatology clinic at the time of study entry and at every follow-up visit at weeks 8, 12, 20, 24, 36, and 52 and every 3 months thereafter. If a patient was in clinical remission after at least 2 years follow-up, the visit frequency was reduced to every 6 months. Informed consent, patient characteristics (e.g., symptom duration, marital status, education, employment, children, housing, alcohol use, smoking, soft drug use), and the ACR 1987 criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis were completed at the baseline visit.

At each visit, clinical data were collected, including the DAS28 (consisting of a 28 tender joint count (TJC28), 28 swollen joint count (SJC28), ESR, and the patient rating for general health on a 100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS-GH) [15]. DAS28 assessments were performed by trained rheumatology nurses. Additionally, patients completed several patient-reported outcome measures, including the Dutch version of the Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI) [19, 20]. The HAQ-DI measures physical disabilities over the past week in 8 categories of daily living. The total score ranges from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more disability. Data collection was facilitated by a web-based entry and monitoring application for the physicians and nurses as well as for the patients.

Healthcare costs were collected and calculated based on the methods used in a previous study in this cohort [16]. In this study, costs were determined by retrieving volumes of hospital-related care (i.e., consultations with the rheumatologist and the rheumatology nurse, telephonic consultations, and hospital admissions) from the hospital information system, and medication (based on dosage and administration period) use was retrieved from the study database. Medications included in the cost analysis were MTX, SSZ, adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab. Each visit, telephone consultation, hospital admission, and medication were multiplied by the cost prices for each volume of care to calculate costs. The standard cost prices from the Dutch Guideline for Cost Analyses were used for hospital-related care [21]. The price, based on personnel, material, and overhead costs of day care hospital admissions required for treatment with infliximab or rituximab, was estimated at a mean of €122 per day (on top of the medication costs). Cost prices for medication were retrieved from the Dutch national tariff list provided by the Dutch Board of Health Insurances. The base year was 2011 for all prices. Prices retrieved from other years were converted to 2011 Euros using the general Dutch consumer price index [22].

Since previous studies used different time frames for defining early remission, three cutoffs (2, 3, and 6 months after baseline) were considered for all analyses of early remission. For long-term follow-up, only the 1-, 3-, and 5-year data were used. As the DREAM remission induction cohort is an observational study in daily clinical practice, the following time windows were used for the different fixed time points in the current analysis: 0 to 2 weeks (baseline), 6 to 10 weeks (2 months), 10 to 14 weeks (3 months), 20 to 28 weeks (6 months), 42 to 54 weeks (1 year), 18 to 30 months (2 years), 30 to 42 months (3 years), and 54 to 66 months (5 years). In case of multiple records within a time window, the record closest to the actual time point was retained for analysis.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are summarized as mean and standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages of observations with non-missing values. Baseline and 1-, 3-, and 5-year disease activity and disability scores were compared between patients categorized as early responders, i.e., being in early clinical remission defined as DAS28-ESR < 2.6 or not at 2 months, 3 months, or 6 months, respectively. Similarly, for the subsample of patients with available healthcare resource usage cost data, cumulative medication costs and resource costs at 2 and 3 years were compared between patients using the same definitions of early remission. Statistical differences in baseline characteristics and long-term clinical and cost outcomes between remission status groups were performed using the Pearson chi-square tests for categorical variables and Welch’s t tests for continuous variables. Since the cost data were non-normally distributed, additional non-parametric bootstrapping was used to check on the robustness of the parametric standard tests. For this, 95% bootstrap (1000 samples) bias-corrected accelerated (BCa) intervals were calculated for group mean differences in costs. Missing values were not imputed, and for the analyses of both continuous and categorical endpoints, only patients who had a baseline and at least one subsequent post-baseline valid observation for the variable of interest were included in the analysis.

Results

Population and follow-up

Out of 534 patients included in the DREAM remission induction cohort, data from 471 patients with a potential follow-up of 5 years were available for analysis. Baseline characteristics of the patients are listed in Table 1. All patients had active disease at baseline. Median symptom duration was 13 (IQR = 8–30) weeks. More than half of the patients were anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (anti-CCP)–positive and more than 75% fulfilled the 1987 ACR criteria for RA [23]. Using the current European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) definition [24], 16.1% of the patients already had erosive disease at baseline.

There were no dropouts during the first year of the study, but at 3 and 5 years, 103 (21%) and 150 (32%) patients, respectively, had no follow-up measurements. Patients who dropped out had significantly lower mean DAS28-ESR scores than non-dropouts at baseline (4.27 vs. 4.64, P = 0.03), but not at 12 months (2.42 vs. 2.46, P = 0.77). None of the other continuous baseline or 12-month variables were associated with dropping out.

Mean (SD) DAS28-ESR scores decreased from 4.56 (SD = 1.38) at baseline to 2.46 (1.04; n = 431) at 1 year. Similar mean DAS28-ESR scores were observed at years 3 (mean = 2.36; SD = 1.11; n = 365) and 5 (mean = 2.29; SD = 1.05; n = 321). Mean HAQ-DI scores showed a similar pattern, with mean scores decreasing from 0.91 (0.65; n = 429) at baseline to 0.52 (0.55; n = 371), 0.53 (0.58; n = 296), and 0.55 (0.56: n = 231) at 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively.

Remission rates

The percentage of patients in early remission was 27.7% (120/433), 38.2% (169/442), and 51.6% (228/442) at 2, 3, and 6 months, respectively. At 1, 3, and 5 years of follow-up, remission rates were 61.7% (266/431), 63.0% (230/365), and 68.8% (221/321), respectively.

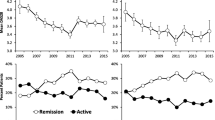

Association between early remission and clinical outcomes

As might be expected, patients being in remission at 2, 3, or 6 months had, on average, lower baseline DAS28-ESR and HAQ-DI scores (Table 1). However, for all definitions of early remission, disease activity scores and functional disability scores for patients not achieving early remission scores remained substantially higher throughout the full follow-up (Table 2). One-year, 3-year, and 5-year DAS28-ESR and HAQ scores tended to be lowest in those patients who were already in remission at 2 months. Although the absolute difference in follow-up disease activity and disability between early responders and non-early responders tended to decrease over the follow-up time points, differences were still statistically significant for those patients completing the 5-year follow-up. Similarly, being in early remission was significantly associated with being in remission at 1 and 3 years (Fig. 2). Across the different time points of early remission, 74.3 to 83.0% of patients with early remission were also in remission at 1 and 3 years. In contrast, of those patients not in early remission, only 37.7 to 56.7% achieved remission later on. This difference was still present, but no longer significant, for remission status at 5 years.

Proportions of patients in remission (DAS28-ESR < 2.6) at 1, 3, and 5 years of follow-up, stratified by having achieved early remission at 2 months (top), 3 months (middle), or 6 months (bottom). P values are for chi-square tests of differences in proportions of patients in follow-up remission (yes/no) by early remission status (yes/no)

Association between early remission and healthcare costs

Mean (SD) total medication costs per patient were €3342.09 (€7203.19) and €4427.07 (€10,767.48) for 0–2 years and 0–3 years, respectively. Mean total resource costs (consultations and admissions) were €1488.31 (€1281.90) per patient at year 2 and €1984.51 (€1496.59) at year 3. Across all different time points, patients who failed to achieve early remission had substantially higher cumulative medication costs over the first 2 years (Table 3). The absolute difference was mainly driven by biologic medication use, although mean costs for conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs) were also significantly higher in patients not achieving early remission. Two-year total medication costs tended to be lowest for those who already achieved remission within 2 months of treatment. Mean consultation costs were also slightly, but significantly, higher for those not achieving early remission. Cumulative total resource costs at 2 years were only significantly different between patients with or without early remission at 3 or 6 months. Mean costs in the subgroup of patients with cumulative 3-year cost data showed very similar results, with still significantly higher total medication costs and consultation costs for those who did not achieve early remission (Table 4).

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to, retrospectively, describe the long-term outcomes for early RA patients who did or did not achieve early remission in a real-world T2T strategy. Taken together, the findings consistently suggest that achieving early remission in T2T patients is associated with better clinical and functional outcomes and lower healthcare costs in the long term.

This study is, to our knowledge, the first to explore the benefits of early remission in real-world patients receiving protocolized T2T therapy. The findings confirm previous studies that have demonstrated the importance of early remission for long-term outcomes in clinical trials [11, 12] and in observational studies [9, 10, 13] of early RA patients receiving conventional, non-protocolized treatment and suggest that the level of early treatment response in T2T may determine a patient’s future outcomes and costs.

Since previous studies have used different time frames for defining early remission or response, this study also examined different time cutoffs for early remission. Regardless of using a cutoff of 2, 3, or 6 months, the results showed similar associations with long-term disease activity, functional disability, and costs. Outcomes tended to be best for those already in remission at 2 months.

First of all, early remission was consistently associated with lower disease activity up to 5 years and a significantly higher proportion of patients in clinical remission up to 3 years of follow-up. This corresponds with previous studies that showed that the level of disease activity during the first 3 months [11] or response during the first 6 months [12, 25] of treatment was strongly related to the level of disease activity at 1-, 2-, and 5-year follow-up, respectively. Moreover, a study in daily care patients showed that sustained remission was mainly determined by time to remission, irrespective of the type of treatment [9]. The association between time to remission and sustained remission in early RA patients was recently confirmed in another observational cohort study [10]. Patients achieving early remission in the current study also had better functional ability for up to 5 years of follow-up. Although previous studies did not specifically examine associations with long-term self-reported physical function, this finding indicates that early remission is also beneficial for patient-reported outcomes.

Interestingly, in the current study, aCCP-positive patients tended to be more likely to achieve remission at 6 months than aCCP-negative patients. These patients may be more representative of the core disease processes of RA and therefore more responsive to DMARDs than aCCP-negative patients with polyarthritis.

Besides clinical and functional outcomes, the study also explored potential cost benefits of achieving early remission. No previous studies have attempted to relate the clinical benefits of early remission in T2T to achieve healthcare cost reductions. The findings of this study showed that early remission was, as would be expected based on the treatment protocol, indeed associated with substantially lower medication costs, especially when comparing patients in remission vs. not in remission at 2 months. For patients not in remission at 2 months, 2- and 3-year medication costs were around ten times higher. This difference was mainly driven by the use of more biologics in this group, but the 2- and 3-year costs associated with csDMARDs were also significantly higher for patients not achieving early remission.

The current finding that early remission—even in a treatment strategy that is already specifically targeted at achieving remission as soon as possible—is still associated with better long-term outcomes for patients and lower costs may have implications for current T2T treatment guidelines and protocols. For instance, Aletaha et al. [11] suggested that it may be beneficial to already switch to alternative therapies if patients are not in remission after 3 months of therapy with csDMARDs. In 2012, DREAM started a new remission induction cohort in which early RA patients are treated according to an even more intensive T2T remission protocol, starting with initial csDMARD combination therapy and switching to biologic after 4 months, in the case of moderate to high disease activity [26]. First-year results showed that this new protocol indeed resulted in an even shorter median time until remission [27].

A strength of the DREAM remission induction cohort and the current study is the short symptom duration of the patients at the time of inclusion and treatment initiation. In the literature, the time durations used to define early RA have varied widely, with durations as long as 2–3 years [28]. The window of opportunity hypothesis, however, refers to the very early phase of the disease. With a median symptom duration of only 13 weeks, patients in the current study can be considered to represent “true” early RA patients.

It should be noted that the analyses were done retrospectively, using a relatively small sample of patients. However, the DREAM remission induction cohort is an observational study of early RA patients treated in daily clinical practice, in contrast to clinical trials with often strict inclusion criteria, potentially making the results more generalizable to patients seen in real-life routine care [29, 30]. Also, the DREAM remission induction cohort had already started in 2006 at which timeless evidence was available about the effectiveness of different T2T strategies. Consequently, several treatment steps of this specific protocol are not fully in line with the current EULAR recommendations for the management of RA [17]. For instance, the protocol did not include the option of leflunomide as an alternative or additional csDMARD in the case of non-response to MTX and allowed low-dose prednisolone administration only. Therefore, some caution should be taken in generalizing the current findings to other, more recent T2T strategies.

Given the exploratory nature of this post hoc study, analyses were mostly descriptive and statistical tests were applied independently to the different follow-up time points. Also, because values were likely not to be missing at random, missing data were not imputed. Finally, given the limited sample size, group comparisons were not adjusted for potentially confounding response modifiers. Taken together, these limitations could have biased the results and limits the inferences that can be drawn.

In future studies examining the impact of early remission in real-world T2T settings, propensity score matching or adjustment in larger datasets may be useful to compare early remission status groups or other relevant subgroup analyses. For instance, we explored differences in outcomes between patients who remained on csDMARDs vs. those who were moved to bDMARD therapy, but the sample sizes of the subgroups in the current dataset were too small to allow a meaningful analysis.

For the current study, cost data were only available for a subgroup of patients and only for arthritis-related medications, rheumatology visits, and consultations. The latter limitation means that the current healthcare costs presented in this study may underestimate the true healthcare costs of early RA patients receiving T2T therapy. Moreover, there were no data on other costs of RA such as costs associated with work disability, and the potential benefits of achieving early remission for those costs. For instance, Puolakka et al. [31] showed that early induction of remission predicted a patient’s ability to continue working, thus lowering the costs to society. Therefore, the actual total benefits of achieving early remission in terms of both economic costs and patient-related consequences are likely to be larger than the findings reported in this study.

In summary, this retrospective study showed that achieving early remission in T2T patients was associated with beneficial outcomes for patients and lower costs in the long term. This finding in a real-world cohort of patients suggests that there may be opportunities to even further improve the treatment of early RA patients in daily clinical care.

References

Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, Bykerk V, Dougados M, Emery P, Kvien TK, Navarro-Compán MV, Oliver S, Schoels M, Scholte-Voshaar M, Stamm T, Stoffer M, Takeuchi T, Aletaha D, Andreu JL, Aringer M, Bergman M, Betteridge N, Bijlsma H, Burkhardt H, Cardiel M, Combe B, Durez P, Fonseca JE, Gibofsky A, Gomez-Reino JJ, Graninger W, Hannonen P, Haraoui B, Kouloumas M, Landewe R, Martin-Mola E, Nash P, Ostergaard M, Östör A, Richards P, Sokka-Isler T, Thorne C, Tzioufas AG, van Vollenhoven R, de Wit M, van der Heijde D (2016) Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 75:3–15. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207524

Solomon DH, Bitton A, Katz JN, Radner H, Brown EM, Fraenkel L (2014) Review: treat to target in rheumatoid arthritis: fact, fiction, or hypothesis? Arthritis Rheumatol 66:775–782. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.38323

Stoffer MA, Schoels MM, Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Breedveld FC, Burmester G, Bykerk V, Dougados M, Emery P, Haraoui B, Gomez-Reino J, Kvien TK, Nash P, Navarro-Compán V, Scholte-Voshaar M, van Vollenhoven R, van der Heijde D, Stamm TA (2016) Evidence for treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: results of a systematic literature search update. Ann Rheum Dis 75:16–22. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207526

Vermeer M, Kuper HH, Hoekstra M, Haagsma CJ, Posthumus MD, Brus HLM, van Riel PLCM, van de Laar MAFJ (2011) Implementation of a treat-to-target strategy in very early rheumatoid arthritis: results of the Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis Monitoring remission induction cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 63:2865–2872. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30494

Vermeer M, Kuper HH, Moens HJB, Drossaers-Bakker KW, van der Bijl AE, van Riel PLCM, van de Laar MAFJ (2013) Sustained beneficial effects of a protocolized treat-to-target strategy in very early rheumatoid arthritis: three-year results of the Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis Monitoring remission induction cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 65:1219–1226. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21984

Brinkmann GH, Norvang V, Norli ES, Grøvle L, Haugen AJ, Lexberg ÅS, Rødevand E, Bakland G, Nygaard H, Krøll F, Widding-Hansen IJ, Bjørneboe O, Thunem C, Kvien T, Mjaavatten MD, Lie E (2018) Treat to target strategy in early rheumatoid arthritis versus routine care - a comparative clinical practice study. Semin Arthritis Rheum S0049-0172:30184–30187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.07.004

Versteeg GA, Steunebrink LMM, Vonkeman HE, ten Klooster PM, van der Bijl AE, van de Laar MAFJ (2018) Long-term disease and patient-reported outcomes of a continuous treat-to-target approach in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis in daily clinical practice. Clin Rheumatol 37:1189–1197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3962-5

Siemons L, ten Klooster PM, Vonkeman HE, Glas CAW, van de Laar MAFJ (2014) Distinct trajectories of disease activity over the first year in early rheumatoid arthritis patients following a treat-to-target strategy. Arthritis Care Res 66:625–630. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22175

Schipper LG, Fransen J, den Broeder AA, Van Riel PLCM (2010) Time to achieve remission determines time to be in remission. Arthritis Res Ther 12:R97. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3027

Kuriya B, Xiong J, Boire G, Haraoui B, Hitchon C, Pope J, Thorne JC, Tin D, Keystone EC, Bykerk V, CATCH Investigators (2014) Earlier time to remission predicts sustained clinical remission in early rheumatoid arthritis -- results from the Canadian Early Arthritis Cohort (CATCH). J Rheumatol 41:2161–2166. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.140137

Aletaha D, Funovits J, Keystone EC, Smolen JS (2007) Disease activity early in the course of treatment predicts response to therapy after one year in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum 56:3226–3235. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22943

Bakker MF, Jacobs JWG, Welsing PMJ, Vreugdenhil SA, van Booma-Frankfort C, Linn-Rasker SP, Ton E, Lafeber FPJG, Bijlsma JWJ, on behalf of the Utrecht Arthritis Cohort Study Group (2011) Early clinical response to treatment predicts 5-year outcome in RA patients: follow-up results from the CAMERA study. Ann Rheum Dis 70:1099–1103. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2010.137943

Scirè CA, Lunt M, Marshall T, Symmons DPM, Verstappen SMM (2014) Early remission is associated with improved survival in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis: results from the Norfolk Arthritis Register. Ann Rheum Dis 73:1677–1682. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203339

Quinn MA, Emery P (2003) Window of opportunity in early rheumatoid arthritis: possibility of altering the disease process with early intervention. Clin Exp Rheumatol 21:S154–S157

Prevoo ML, van ‘t Hof MA, Kuper HH et al (1995) Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts: development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 38:44–48

Vermeer M, Kievit W, Kuper HH, Braakman-Jansen LMA, Bernelot Moens HJ, Zijlstra TR, den Broeder AA, van Riel PLCM, Fransen J, van de Laar MAFJ (2013) Treating to the target of remission in early rheumatoid arthritis is cost-effective: results of the DREAM registry. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 14:350. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-14-350

Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M, Nam J, Ramiro S, Voshaar M, van Vollenhoven R, Aletaha D, Aringer M, Boers M, Buckley CD, Buttgereit F, Bykerk V, Cardiel M, Combe B, Cutolo M, van Eijk-Hustings Y, Emery P, Finckh A, Gabay C, Gomez-Reino J, Gossec L, Gottenberg JE, Hazes JMW, Huizinga T, Jani M, Karateev D, Kouloumas M, Kvien T, Li Z, Mariette X, McInnes I, Mysler E, Nash P, Pavelka K, Poór G, Richez C, van Riel P, Rubbert-Roth A, Saag K, da Silva J, Stamm T, Takeuchi T, Westhovens R, de Wit M, van der Heijde D (2017) EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 76:960–977. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210715

Vermeer M, Kuper HH, Bernelot Moens HJ, Hoekstra M, Posthumus MD, van Riel PLCM, van de Laar MAFJ (2012) Adherence to a treat-to-target strategy in early rheumatoid arthritis: results of the DREAM remission induction cohort. Arthritis Res Ther 14:R254. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4099

Bruce B, Fries JF (2005) The health assessment questionnaire (HAQ). Clin Exp Rheumatol 23:S14–S18

Boers M, Jacobs JW, van Vliet Vlieland TP, van Riel PL (2007) Consensus Dutch health assessment questionnaire. Ann Rheum Dis 66:132–133

Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Tan S, Bouwmans C (2011) Handleiding voor kostenonderzoek. Methoden en standaard kostprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg

Statistics Netherlands. Consumer price index. www.cbs.nl. Accessed 2 May 2019

Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, Mcshane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, Healey LA, Kaplan SR, Liang MH, Luthra HS, Medsger TA, Mitchell DM, Neustadt DH, Pinals RS, Schaller JG, Sharp JT, Wilder RL, Hunder GG (1988) The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 31:315–324

van der Heijde D, van der Helm-van Mil AHM, Aletaha D et al (2013) EULAR definition of erosive disease in light of the 2010 ACR/EULAR rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria. Ann Rheum Dis 72:479–481. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202779

Vázquez I, Graell E, Gratacós J, Cañete JD, Viñas O, Ercilla MG, Gómez A, Hernández MV, Rodríguez-Cros JR, Larrosa M, Sanmartí R (2007) Prognostic markers of clinical remission in early rheumatoid arthritis after two years of DMARDs in a clinical setting. Clin Exp Rheumatol 25:231–238

Steunebrink LMM, Vonkeman HE, Ten Klooster PM et al (2016) Recently diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis patients benefit from a treat-to-target strategy: results from the DREAM registry. Clin Rheumatol 35:609–615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-016-3191-3

Steunebrink LMM, Versteeg GA, Vonkeman HE, ten Klooster PM, Kuper HH, Zijlstra TR, van Riel PLCM, van de Laar MAFJ (2016) Initial combination therapy versus step-up therapy in treatment to the target of remission in daily clinical practice in early rheumatoid arthritis patients: results from the DREAM registry. Arthritis Res Ther 18:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-0962-9

Mitchell KL, Pisetsky DS (2007) Early rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 19:278–283. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0b013e32805e87bf

Garrison LP, Neumann PJ, Erickson P et al (2007) Using real-world data for coverage and payment decisions: the ISPOR real-world data task force report. Value Health 10:326–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00186.x

Saturni S, Bellini F, Braido F, Paggiaro P, Sanduzzi A, Scichilone N, Santus PA, Morandi L, Papi A (2014) Randomized controlled trials and real life studies. Approaches and methodologies: a clinical point of view. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 27:129–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pupt.2014.01.005

Puolakka K, Kautiainen H, Möttönen T, Hannonen P, Korpela M, Hakala M, Järvinen P, Ahonen J, Forsberg S, Leirisalo-Repo M, FIN-RACo Trial Group (2005) Early suppression of disease activity is essential for maintenance of work capacity in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: five-year experience from the FIN-RACo trial. Arthritis Rheum 52:36–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.20716

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Publication of the study results was not contingent on the sponsor’s approval or censorship of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

In accordance with Dutch Law on medical-scientific research with humans, no ethical approval was required because all data were collected in the course of regular daily clinical practice. Nonetheless, patients were fully informed and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Disclosures

Walid Fakhouri, Inmaculada de la Torre, and Claudia Nicolay are employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. The other authors have no disclosures to report.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

ten Klooster, P.M., Oude Voshaar, M.A.H., Fakhouri, W. et al. Long-term clinical, functional, and cost outcomes for early rheumatoid arthritis patients who did or did not achieve early remission in a real-world treat-to-target strategy. Clin Rheumatol 38, 2727–2736 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04600-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04600-7