Abstract

Background

The overall benefit of intensive treatment strategies in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) remains uncertain. We explored how reductions in disability and improvements in quality of life scores are affected by alternative assessments of reductions in disease activity scores for 28 joints (DAS28) in two trials of intensive treatment strategies in active RA.

Methods

One trial (CARDERA) studied 467 patients with early active RA receiving 24 months of methotrexate monotherapy or steroid and disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) combinations. The other trial (TACIT) studied 205 patients with established active RA; they received 12 months of treatment with DMARD combinations or biologic agents. We compared changes in the health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) and Euroqol-5D (EQ5D) at trial endpoints in European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) good and moderate EULAR responders in patients in whom complete endpoint data were available.

Results

In the CARDERA trial 98 patients (26 %) were good EULAR responders and 160 (32 %) were EULAR moderate responders; comparable data in TACIT were 66 (35 %) and 86 (46 %) patients. The magnitude of change in the HAQ and EQ5D was greater in both trials in EULAR good responders than in EULAR moderate responders. HAQ scores had a difference in of –0.49 (95 % CI –0.66, –0.32) in the CARDERA and –0.31 (95 % CI –0.47, –0.13) in the TACIT trial. With the EQ5D comparable differences were 0.12 (95 % CI 0.04, 0.19) and 0.15 (95 % CI 0.05, 0.25). Both exceeded minimum clinically important differences in HAQ and EQ5D scores.

Conclusions

We conclude that achieving a good EULAR response with DMARDs and biologic agents in active RA results in substantially improved mean HAQ and EQ5D scores. Patients who achieve such responses should continue on treatment. However, continuing such treatment strategies is more challenging when only a moderate EULAR response is achieved. In these patients evidence of additional clinically important benefits in measures such as the HAQ should also be sought.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A key goal in treating rheumatoid arthritis (RA) with conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologic agents is reducing inflammatory synovitis, which reduces disability and maximises quality of life. Reductions in synovitis with treatment are assessed using the disease activity score for 28 joints (DAS28) [1]. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) classifies good responders as having DAS28 scores of 3.2 or less with reductions in DAS28 of more than 1.2 [2]. Patients with DAS28 scores over 3.2 who have reductions in DAS28 scores of more than 1.2 have moderate responses. Patients with reductions in DAS28 of less than 0.6 are non-responders. The treat-to-target initiative recommends increasing treatment until patients achieve remission or low disease activity [3].

High-cost biologic treatments such as tumour necrosis factor inhibitors are used within agreed guidelines. When patients achieve good EULAR responses there is strong rationale for maintaining treatment. Similarly, when patients do not respond there is no reason to continue treatment. However, there is uncertainty in patients with incomplete responses. The British Society for Rheumatology (BSR), recommends patients with active RA, who have not responded to methotrexate and another DMARD, should be considered for biologic therapy [4]. Provided they achieve reductions in DAS28 of over 1.2 by 6 months they should continue receiving biologic treatments. This approach was accepted by the National Institute for Health And Care Excellence (NICE) in its health technology appraisals of biologic treatments for RA [5, 6]. Initially NICE recommended only continuing treatment if DAS28 is reduced by 1.2 or more [5], though recent guidelines recommend patients achieve at least a moderate EULAR response for treatment to continue [6].

The impact on disability and quality of life of reducing disease activity are assessed using the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) [7] and EuroQol-5D (EQ5D) [8]. There are doubts about the value both to patients and the funders of healthcare from maintaining high-cost treatments if patients only achieve moderate EULAR responses. We hypothesised that patients with good EULAR responses have substantially larger improvements in HAQ and EQ5D scores than patients with moderate EULAR responses, who do not achieve low disease activity or remission, and in whom the final DAS28 scores remain over 3.2. We tested our hypothesis in secondary analyses of two published randomised controlled trials (RCTs). One trial, cost-effectiveness of treatment strategies using combination of disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and glucocorticoids in early rheumatoid arthritis (CARDERA), studied intensive DMARD treatment in early RA [9]. The other trial, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors against combination intensive therapy (TACIT), studied intensive treatment with DMARDs and biologic agents in established RA [10]. In both trials we compared changes in HAQ and EQ5D scores in patients achieving good EULAR responses with patients achieving reductions in DAS28 scores over 1.2, and who had only moderate EULAR responses.

Methods

Patients

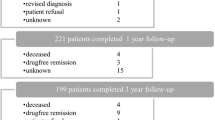

We undertook secondary analyses using data from two completed randomised controlled trials in RA. Details of the patients and treatments used have been published [8, 9]. The CARDERA trial randomised 467 patients to monotherapy or combination therapy with conventional DMARDs and steroids in early untreated active RA. The TACIT trial randomised 205 patients to intensive conventional DMARDs or biologic treatment strategies in established active RA. In TACIT all patients met the current NICE criteria for biologic treatments.

Assessments

Both trials used the DAS28 calculated with erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) to assess disease activity. We studied patients at the predefined final endpoints of each trial: 24 months for CARDERA and 12 months for TACIT. Both trials measured disability using the HAQ and quality of life using the EQ5D. We applied reported minimal clinically important differences (MCID) to assess benefits from reducing DAS28 scores. For the HAQ we used an MCID of 0.22 [11]. For the EQ5D we used an MCID of 0.07 [12]. We used the DAS28 to assess remission, which was defined by DAS28 < 2.6; this definition has been widely used [13].

Analyses

We used IBM SPSS statistical software (version 22). Descriptive statistics described means, standard error and confidence intervals. We studied patients with all data available at the trial endpoints. We divided patients into EULAR non-responders, moderate responders and good responders. We compared changes in HAQ and EQ5D scores between good and moderate EULAR responders for each trial using the independent samples t test. We also subdivided moderate and good EULAR responders by their final DAS28 scores. In addition, we used the previous NICE criterion for remaining on treatment (change in DAS28 score >1.2) to categorise patients, replicating EULAR response criteria by dividing patients into those who also achieved DAS28 low disease activity scores at the trial endpoint and those who did not. Finally, we assessed the numbers of patients who achieved different levels of improvement in HAQ and EuroQol scores in both trials in relation to moderate and good EULAR responses.

Results

Patients studied

In the CARDERA trial 121 patients (32 %) were EULAR non-responders, 160 (42 %) moderate responders and 98 (26 %) good responders. In the TACIT trial 34 patients (18 %) were EULAR non-responders, 86 (46 %) moderate responders and 66 (35 %) good responders. The trial designs differed, with all patients in TACIT but not CARDERA receiving intensive therapy; consequently, differences in response rates were expected. In both trials demographic characteristics, clinical variables like DAS28 scores and components of the DAS28, HAQ and EQ5D scores were similar across groups. As this secondary analysis does not assess treatment effects no comparative data between groups are presented.

Baseline and endpoint scores

Baseline and final endpoint data for DAS28 and HAQ and EQ5D scores in both trials for different EULAR responses are shown in Table 1. In the CARDERA trial there were no significant differences between baseline scores in any EULAR responder groups. In the TACIT trial the good EULAR responders had lower baseline HAQ scores and higher baseline EQ5D scores.

Differences in disability between EULAR moderate and good responders

Only patients with either moderate or good EULAR responses had significant reductions in HAQ scores at the trial endpoints (Table 2). Moderate responders had reductions in HAQ scores of 0.39 and 0.33 in the CARDERA and TACIT trials, respectively. Good responders had reductions of 0.88 and 0.64, respectively. In both trials the difference between moderate and good responders exceeded the MCID for HAQ scores (0.22) with differences in reductions of 0.49 and 0.30, respectively. These differences were significant (p < 0.01, unpaired t test).

Changes in quality of life

The mean EQ5D scores had a similar pattern. Only patients with moderate or good EULAR responses had significant improvements in EQ5D scores at the trial endpoints (Table 3). Moderate responders had increases in EQ5D scores of 0.18 and 0.15 in the CARDERA and TACIT trials, respectively. Good responders had increases of 0.30 in both trials. The difference between moderate and good responders exceeded the EQ5D MCID (0.07) in both trials with differences in increases in EQ5D scores of 0.12 and 0.15, respectively. These differences were significant (p < 0.01, unpaired t test).

Alternative assessments of response

Similar analyses based on patients achieving reductions in DAS28 > 1.2, subdivided by whether or not they also achieved low DAS28 at the trial endpoints, were similar in relation to both HAQ and EQ5D scores. Patients who did not achieve low disease activity scores had only modest improvements in both scores (detailed results not shown).

Additional benefits of achieving remission

Another analysis subdivided patients achieving good EULAR responses into those who were also in remission and those who were not at the trial endpoints. In the CARDERA trial 70/98 patients (71 %) with good responses were in remission and 28/98 (29 %) were not. There were non-significant benefits for both HAQ scores and EQ5D scores with remission; mean differences between groups were –0.29 (95 % CI –0.61, 0.02) for HAQ scores and 0.11 (–0.02, 0.24) for EQ5D scores. In the TACIT trial 41/66 patients (62 %) with good responses were in remission and 25/66 (38 %) were not. There were also non-significant benefits for both HAQ scores and EQ5D scores with remission. The mean differences between the groups were –0.13 (–0.41, 0.14) for HAQ and 0.08 (–0.07, 0.24) for EQ5D.

Categories of HAQ and EQ5D change with EULAR responses

In the CARDERA trial 63 % of patients with moderate EULAR responses had improvements in HAQ exceeding the MCID (0.22) compared with 79 % of patients with good EULAR responses. In the TACIT trial 57 % of patients with moderate EULAR responses had improvements in HAQ exceeding the MCID compared with 80 % of patients with good EULAR responses. On more detailed analysis (Fig. 1) there was a wide range in HAQ score improvements in both trials in moderate and good EULAR responders; more patients with large improvements in HAQ scores exceeding 1.0 had good EULAR responses, particularly in the early RA trial (CARDERA). In this trial 41 % of patients with good EULAR responses had improvements in HAQ over 1.0.

Changes in Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) scores in four categories in moderate and good European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) responders in both the cost-effectiveness of treatment strategies using combination of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and glucocorticoids in early rheumatoid arthritis (CARDERA), and tumour necrosis factor inhibitors against combination intensive therapy (TACIT) trials

Changes were similar with the EQ5D scores. In the CARDERA trial 59 % of patients with moderate EULAR responses had improvements in EQ5D scores exceeding the MCID (0.07) compared with 80 % of patients with good EULAR responses. In the TACIT trial 59 % of patients with moderate EULAR responses had improvements in EQ5D scores exceeding the MCID compared with 79 % of patients with good EULAR responses. On more detailed analysis (Fig. 2) there was a wide range in improvement in the EQ5D scores in both trials in moderate and good EULAR responders; more patients with good EULAR responses had large improvements in EQ5D scores. The benefits from achieving good EULAR responses were less marked with improvements in EQ5D scores.

Changes in EuroQol-5D (EQ5D) scores in four categories in moderate and good European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) responders in both the cost-effectiveness of treatment strategies using combination of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and glucocorticoids in early rheumatoid arthritis (CARDERA), and tumour necrosis factor inhibitors against combination intensive therapy (TACIT) trials

Discussion

Our secondary analyses of two large English RCTs in early and established active RA shows that patients with good EULAR responses have larger clinically meaningful improvements in disability and quality of life than patients with moderate EULAR responses. These findings support the concept of treat-to-target. They indicate that achieving low disease activity or remission states should be the treatment goal. The benefits of good EULAR responses are seen in both early and established RA. The findings were similar if we used the earlier NICE criterion of an improvement in DAS28 of more than 1.2.

The reliance of current NICE guidance on changes in DAS28 of more than 1.2 has been criticised by Jerram et al [14], who point out that this threshold was not used in clinical trials. This concern is ameliorated by the new NICE guidance. Judging patients’ responses to DMARDs and biologic therapy is challenging. EULAR response criteria were designed for use in individual patients and trials. The other major composite response criteria, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria, are only intended for trials. These two validated response criteria have been compared in several studies [15, 16]; they measure similar changes. However, their use in routine clinical practice and relating their findings to patients’ perceived responses requires more research. Gulfe et al. showed that when response criteria are used at the individual patient level the results are difficult to interpret [17]. Ward et al. [18] found patients’ perceptions of improvement may differ from conventional assessments like ACR20 responses, and that thresholds of minimal clinically important improvement may be larger than previously thought, including the need for a DAS28 improvement of at least 1.2 [19]. Among patients receiving treatment for active RA, three months may be the optimal time point to increase the intensity of treatment [20]. However, when assessing response to biologic therapy, real-world evidence suggests a six-month time point is needed to optimise patients’ responses [21].

Low disease activity optimises key patient-related outcomes like HAQ and EQ5D scores [22–24]. Our own findings mirror these previous reports. Remission is one potentially important outcome, although only a minority of our patients achieved this. Interestingly some other trials in early RA, such as the FIN-RACo trial [25], reported higher remission rates; the reasons for this heterogeneity are uncertain. When patients achieve sustained remission, they have less long-term work disability [26]. Some patients with moderate EULAR responses in our trials had good reductions in disability and improvements in quality of life. However, many did not and the best management of such patients is uncertain. Continuing to prescribe high-cost biologic therapy for patients with modest improvements in disease activity and little or no reduction in disability seems questionable. It may be preferable to continue biologic treatments in patients with moderate EULAR responses who have also had clinically meaningful reductions in disability.

Our report has several strengths. The two trials were large, there was reasonable patient retention on treatment, and they were based across many English specialist centres with a broad geographic spread. We found similar effects in trials of early and established RA. Our findings are therefore likely to be generalisable in guiding clinical practice decisions.

Our analyses also have limitations. First, we only considered differences at the trial endpoints. Different effects would have been seen by evaluating all time points. Second, choosing specific cutoff points, such as DAS28 of 3.2 or less may have over done similarly well. Third, some of the treatments used, particularly ciclosporin, which was used in the CARDERA trial, are not commonly prescribed in routine practice. Fourth, we combined the effects of a range of different treatments, and the relationship between disease activity and HAQ and EQ5D scores may be different across drug classes. Finally, our inference that patients who do not achieve low DAS28 scores with one treatment strategy may do better with another could be incorrect; some patients may achieve poor outcomes with all treatment strategies.

Conclusions

Achieving good EULAR responses to treatment with DMARDs and biologic agents leads to substantial improvements in HAQ and EQ5D scores. Patients who achieve such responses should continue on treatment. However, continuing patients on intensive treatment regimens, particularly using high-cost biologic agents, is more challenging if they only achieve moderate EULAR responses. Evidence of additional clinically important benefits in measures such as the HAQ should also be sought to justify continuing treatment in these patients.

Abbreviations

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; CARDERA, Cost-effectiveness of treatment strategies using combination of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and glucocorticoids in early rheumatoid arthritis; CI, confidence interval; DAS28, twenty-eight joint disease activity score; DMARD, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; EQ5D, Euroqol-5D (a standardized instrument for measuring generic health status); EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; MCID, minimal clinically important difference; NICE, National Institute of Health and Care Excellence; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TACIT, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors against combination intensive therapy

References

Prevoo MLL, Van ’T Hof MA, Kuper HHH, Van Leeuwen MA, Van De Putte LBA, Van Riel PLCM. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts: development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:44–8.

Fransen J, Van Riel PLCM. The Disease Activity Score and the EULAR response criteria. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:S93–9.

Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:3–15.

Deighton C, Hyrich K, Ding T, Ledingham J, Lunt M, Luqmani R, et al. BSR and BHPR rheumatoid arthritis guidelines on eligibility criteria for the first biological therapy. Rheumatology. 2010;49:1197–9.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Health Technology Appraisal). Adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (TA130), October 2007.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (guidelines in development). Final appraisal determination: Rheumatoid arthritis: adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab and abatacept (ID537), August 2015

Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: dimensions and practical applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:20.

Brooks R, Rabin R, de Charro F. The Measurement and Valuation of Health Status Using EQ-5D: A European Perspective: Evidence from the EuroQol BIO MED Research Programme. Rotterdam: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003.

Choy EH, Smith CM, Farewell V, Walker D, Hassell A, Chau L, et al. Factorial randomised controlled trial of glucocorticoids and combination disease modifying drugs in early rheumatoid arthritis. CARDERA Trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(5):656–63.

Scott DL, Ibrahim F, Farewell V, O’Keeffe AG, Ma M, Walker D, et al. Randomised controlled trial of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors against combination intensive therapy with conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in established rheumatoid arthritis: the TACIT trial and associated systematic reviews. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18(66):1–164.

Wells GA, Tugwell P, Kraag GR, Baker PR, Groh J, Redelmeier DA. Minimum important difference between patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the patient’s perspective. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:557–60.

Walters SJ, Brazier JE. Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1523–32.

Sokka T, Hetland ML, Mäkinen H, Kautiainen H, Hørslev-Petersen K, Luukkainen RK, et al. Questionnaires in Standard Monitoring of Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis Group. Remission and rheumatoid arthritis: data on patients receiving usual care in twenty-four countries. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2642–51.

Jerram S, Butt S, Gadsby K, Deighton C. Discrepancies between the EULAR response criteria and the NICE guidelines for continuation of anti-TNF therapy in RA: a cause for concern? Rheumatology. 2008;47:180–2.

van Gestel AM, Prevoo ML, van’t Hof MA, van Rijswijk MH, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Development and validation of the European League Against Rheumatism response criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Comparison with the preliminary American College of Rheumatology and the World Health Organization/International League Against Rheumatism Criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:34–40.

Gülfe A, Geborek P, Saxne T. Response criteria for rheumatoid arthritis in clinical practice: how useful are they? Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1186–9.

Gülfe A, Aletaha D, Saxne T, Geborek P. Disease activity level, remission and response in established rheumatoid arthritis: performance of various criteria sets in an observational cohort, treated with anti-TNF agents. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:41.

Ward MM, Guthrie LC, Alba MI. Rheumatoid arthritis response criteria and patient-reported improvement in arthritis activity: is an American College of Rheumatology twenty percent response meaningful to patients? Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66:2339–43.

Ward MM, Guthrie LC, Alba MI. Clinically important changes in individual and composite measures of rheumatoid arthritis activity: thresholds applicable in clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1691–6.

Aletaha D, Alasti F, Smolen JS. Optimisation of a treat-to-target approach in rheumatoid arthritis: strategies for the 3-month time point. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208324.

Kievit W, Fransen J, Adang EM, Kuper HH, Jansen TL, De Gendt CM, et al. Evaluating guidelines on continuation of anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment after 3 months: clinical effectiveness and costs of observed care and different alternative strategies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:844–9.

Linde L, Sørensen J, Østergaard M, Hørslev-Petersen K, Hetland ML. Does clinical remission lead to normalization of EQ-5D in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and is selection of remission criteria important? J Rheumatol. 2010;37:285–90.

Klarenbeek NB, Koevoets R, van der Heijde DM, Gerards AH, Ten Wolde S, Kerstens PJ, et al. Association with joint damage and physical functioning of nine composite indices and the 2011 ACR/EULAR remission criteria in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1815–21.

Alemao E, Samuel Joo S, Kawabata H, Al MJ, Allison PD, Rutten-Van Mölken MP, Frits ML, Iannaccone CK, Shadick NA, Weinblatt ME. Effects of achieving target measures in ra on functional status, quality of life and resource utilization: analysis of clinical practice data. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68(3):308–17. doi:10.1002/acr.22678.

Möttönen T, Hannonen P, Leirisalo-Repo M, Nissilä M, Kautiainen H, Korpela M, et al. Comparison of combination therapy with single-drug therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised trial. FIN-RACo trial group. Lancet. 1999;353:1568–73.

Puolakka K, Kautiainen H, Möttönen T, Hannonen P, Korpela M, Hakala M, et al. Early suppression of disease activity is essential for maintenance of work capacity in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: five-year experience from the FIN-RACo trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:36–41.

Acknowledgements

The paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) as one of its Programme Grants for Applied Research (Grant Reference Number: RP-PG-0610-10066; Programme Title: Treatment Intensities and Targets in Rheumatoid Arthritis Therapy: Integrating Patients’ and Clinicians’ Views – The TITRATE Programme). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Authors’ contributions

AM and FI carried out the analysis and drafted the manuscript. DS and JG conceived the study, participated in the design and coordination and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The CARDERA trial was approved by the South East Multicentre Research Ethics Committee ((MREC(1)99/04)). The TACIT trial was approved by University College London Hospital research ethics committee (MREC Ref: 07/Q0505/57). All patients gave written informed consent.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mian, A.N., Ibrahim, F., Scott, D.L. et al. Optimal responses in disease activity scores to treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: Is a DAS28 reduction of >1.2 sufficient?. Arthritis Res Ther 18, 142 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-1028-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-1028-8