Abstract

Rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) encompass a spectrum of degenerative, inflammatory conditions predominantly affecting the joints. They are a leading cause of disability worldwide and an enormous socioeconomic burden. However, worldwide deficiencies in adult and paediatric RMD knowledge among medical school graduates and primary care physicians (PCPs) persist. In October 2017, the World Forum on Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases (WFRMD), an international think tank of RMD and related experts, met to discuss key challenges and opportunities in undergraduate RMD education. Topics included needs analysis, curriculum content, interprofessional education, teaching and learning methods, implementation, assessment and course evaluation and professional formation/career development, which formed a framework for this white paper. We highlight a need for all medical graduates to attain a basic level of RMD knowledge and competency to enable them to confidently diagnose, treat/manage or refer patients. The importance of attracting more medical students to a career in rheumatology, and the indisputable value of integrated, multidisciplinary and multiprofessional care are also discussed. We conclude that RMD teaching for the future will need to address what is being taught, but also where, why and to whom, to ensure that healthcare providers deliver the best patient care possible in their local setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) encompass over 200 degenerative, inflammatory and autoimmune conditions predominantly affecting the musculoskeletal (MSK) system [1,2,3]. They are a leading cause of disability worldwide [4] and have a profound impact on quality of life through chronic pain, social exclusion, loss of employment and reduced productivity [1, 5, 6]. The economic burden of RMDs and the pressure they impose on healthcare services can be staggering [6, 7]. In Europe, RMDs are estimated to cost more than 200 billion Euros per year and are considered the most expensive diseases for healthcare systems [8]. Moreover, in the context of an ageing world population and increasingly sedentary and obesogenic lifestyles, the impact of RMDs on society is expected to increase further [6].

In an effort to raise global awareness of the burden of RMDs amongst policy makers and the public, a working group for the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) have developed a consensus statement defining RMDs: ‘A diverse group of diseases that commonly affect the joints, but can also affect any organ of the body. There are more than 200 different RMDs, affecting both children and adults. They are usually caused by problems of the immune system, inflammation, infections, or gradual deterioration of joints, muscle, and bones. Many of these diseases are long term and worsen over time. They are typically painful and limit function. In severe cases, RMDs can result in significant disability, having a major impact on both quality of life and life expectancy’ [2, 3].

The World Forum on Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases (WFRMD) [9] is an international think tank of rheumatology experts and related specialists, dedicated to increasing awareness of RMDs as a burden to society and to improving local and global RMD care. Our inaugural white paper [10, 11] identified education as a key priority due to the marked shortage of rheumatologists globally and the inadequacies in RMD knowledge and confidence documented among primary care physicians (PCPs) [10]. The implication of these findings is that PCPs are poorly prepared for diagnosing and managing RMDs, resulting in delays in referral.

The aims of this second white paper are to:

-

1.

Foster dialogue between rheumatologists and medical education specialists, and advocate that all medical school graduates should attain a basic level of RMD competency. This would ensure that PCPs are able to confidently diagnose, initiate appropriate treatment without delay or refer RMD patients to rheumatologists.

-

2.

Support improvement in undergraduate RMD education by providing stakeholders with an up-to-date needs assessment and an overview of evidence-based modern RMD learning methods with examples of best practice from around the world.

-

3.

Identify strategies to attract more medical students to a career in rheumatology and encourage the incorporation of these strategies into undergraduate medical school curricula.

Methods

A full-day meeting of the WFRMD was held in Abu Dhabi on 20 October 2017 to define the aims and scope of this white paper. A list of topics for discussion was circulated to meeting invitees in advance of the meeting, expanding on the key challenges, barriers, and opportunities in undergraduate RMD education identified in the previous white paper.

The discussions culminated in the development of a framework, based on the six-step approach to curriculum development by Kern et al. [12] addressing the following areas: (1) needs analysis, (2) curriculum content, (3) interprofessional education, (4) teaching and learning methods, (5) implementation, (6) assessment and course evaluation, (7) professional formation and career development.

A focused PubMed literature search was conducted based on the agreed framework. The search focused on publications from the year 2000 onwards, to more closely reflect current practices.

Needs analysis

Burden of RMDs

RMDs are estimated to account for 10–30% of primary care visits for both adults and children [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. According to a recent systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016, low back pain is the leading cause of years lived with disability across all 195 countries and territories studied, with serious implications for quality of life, work productivity and healthcare services globally [4] (Table 1).

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported that one in four adults in the USA now have arthritis. The report also emphasised that RMDs such as arthritis can negatively impact chronic comorbidities including obesity and type 2 diabetes [21]. Conversely, obesity has been implicated in the development or progression of a number of RMDs [22]. According to a recent global report, the number of adult women with obesity increased from 69 million in 1975 to 390 million in 2016. Over the same timeframe, the number of adult men with obesity increased from 31 to 281 million [23]. Worldwide, the number of girls and boys with obesity has increased from 5 and 6 million in 1975 to 50 and 74 million in 2016, respectively [23]. This rising prevalence of obesity, for both adults and children, has profound implications for RMD healthcare and the societal burden of RMD conditions.

Patient needs

The effective management of RMDs depends upon integrated, multidisciplinary and multiprofessional care centred around the needs of the individual. Optimal management of RMDs can often be provided within the community and primary care setting (e.g. regional pain, non-specific back pain and mild/moderate osteoarthritis). However, in many cases, the expertise of a rheumatologist and access to specialist services and facilities are also warranted [24]. A seamless continuum of health services encompassing all levels of care is therefore required to ensure the timely diagnosis and management of patients by healthcare professionals (HCPs) with the appropriate competency (UK National Health Service principles of ‘right care, right time, right place’ [24, 25]).

Workforce needs

Inadequacy in undergraduate RMD education

At the turn of the twenty-first century, undergraduate education in rheumatology was deemed to be inadequate across the globe [26]. In certain medical schools in Latin America, rheumatology accounted for ≤ 1% of the total programme credits [27]. Meaningful progress has since been made by virtue of global initiatives, such as the World Health Organization (WHO)-endorsed ‘Bone and Joint Decade’ (BJD) (2000–2010). A key priority for the BJD was to increase the education of all HCPs working in MSK medicine [28].

The US BJD’s ‘Project 100’ was founded to enhance recognition of MSK medicine as an ‘essential discipline’ by all medical schools, and to ensure that it is given equal emphasis to other organ systems [29]. This work led to the development of recommendations for core RMD curricula and some curricular reform [30,31,32,33,34]. Nevertheless, worldwide deficiencies in RMD knowledge and skills among medical school graduates and PCPs persist [27, 35, 36]. Surveys of students, graduates, PCPs and even young rheumatologists consistently reveal low confidence in MSK competencies [16, 37,38,39,40]. Furthermore, studies assessing RMD knowledge and clinical skills using the validated Freedman and Bernstein examination demonstrated poor competence among graduates and students irrespective of where they were educated [37, 41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49] (Table 2). Alarming deficiencies in the RMD knowledge of junior doctors and PCPs have also been widely reported [39, 43, 52,53,54].

Clinicians often lack confidence in diagnosing children and young adults presenting with MSK symptoms [55] (Table 2). This is particularly problematic as paediatric patients with MSK symptoms often present to non-specialist clinicians [18] and although most cases are minor, the differential diagnosis can include serious and even life-threatening conditions [33].

The importance of early diagnosis and appropriate treatment in improving long-term prognosis for patients with RMDs cannot be overstated. Developed countries have seen a substantial reduction in the time to diagnosis for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, indicating greater awareness of the importance of early diagnosis [58]. However, this is not the case in regions of economic inequality with disparities in access to public healthcare and restricted access to private medicine [58, 59]. As many patients with RMDs will ultimately present to non-specialists [60], gaining basic adult and paediatric RMD knowledge and competencies should be a fundamental requirement of global undergraduate medical education. This is especially pertinent in countries which are devoid of rheumatologists and/or where undergraduate medical education is the only training that a PCP will receive [41]. In many areas of the Americas, for example, patients with RMDs are often treated by non-specialists lacking training and/or experience in the management of such conditions.

Education regarding transitional care for children and young people who transfer to adult rheumatology care is also lacking. Recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance in the UK and EULAR recommendations for paediatric rheumatology [61] highlighted unmet education and training needs across the RMD workforce—not just for specialists but also allied health professions and PCPs. Recommendations from the literature for improving RMD education include increased exposure to adult and paediatric RMDs (including the more common MSK conditions) in undergraduate curricula [37, 38, 54, 62, 63], increased time and resources devoted to MSK anatomy [54], and clinical rotation in a MSK field [47].

Shortfalls in rheumatologists

Although an increase in the number of rheumatologists and training programmes has been observed in recent years [64], global and regional shortfalls remain (especially for paediatric rheumatologists) as well as pronounced disparities between urban and rural areas [10, 35, 60, 64,65,66]. Factors contributing to this shortage are complex and multifaceted. However, from the perspective of undergraduate education, more effort is needed to increase exposure to RMDs and improve understanding of what rheumatology is in order to attract medical students to this specialty.

Curriculum content

Core recommendations and curriculum design

Being dynamic, multi-dimensional, contextual and flexible are essential qualities for modern curricula. Educational goals and learning objectives for undergraduate MSK medicine have employed a range of methodologies [30, 31, 34, 67, 68]. In 2005, The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) provided an overview of learning objectives for the knowledge, skills and attitudes relevant to MSK conditions that all students should acquire during medical school [30]. This report also included the panel’s views on educational strategies, curriculum design, implementation and assessment, plus a description of tools to aid curriculum management [30].

One of the primary outcomes of the BJD was the publication of a set of global core curriculum recommendations for undergraduate RMD education, developed by experts from across 29 countries with a spectrum of relevant specialties [31]. The curriculum was subsequently validated by educators across Canada representing 77 accredited academic programmes [69]. Although the importance of certain items was rated differently by orthopaedic surgeons compared to rheumatologists, all 80 items proposed by Woolf et al. received a mean rank score of ≥ 3 out of 4, with 4 deemed to be most important [69]. Of note, 35 items received a mean score of ≥ 3.8 and were classified into three categories: (1) clinical assessment (accurate and thorough history-taking and physical examination), (2) emergency and red flag conditions and (3) common problems that any physician might encounter [69]. The study also identified additional topics which were incorporated into the multidisciplinary Canadian MSK Core Curriculum [69]. Based on the global core curriculum, the Australian Musculoskeletal Education Collaboration (AMSEC) also developed and published its own ‘National Core Competencies in Musculoskeletal Basic and Clinical Science’ [50].

In 2009, The Association of Academic Physiatrists (a partner of the US BJD Project 100) published their white paper on MSK education for medical students which advocated for an interdisciplinary model for education [68]. The publication provided examples of curricula that can be implemented during each year of medical school covering anatomy (year 1), physical examination (year 2), core clinical rotations (year 3) and advanced elective clerkships (year 4). They also provided guidelines and examples for assessing core clinical rotations and advanced electives [68]. In 2015, Jandial et al. published consensus-based learning outcomes for undergraduate paediatric MSK medicine [34]. The outcomes encompassed indicators of important RMDs, such as inflammatory arthritis, as well as common conditions presenting within primary care and paediatrics [34]. Paediatric MSK learning outcomes for GP trainees have also been produced [33].

The language around education is constantly evolving and with it, our interpretation and strategies of applying key principles. Following considerable discussion around the merits of ‘competency-based’ education [70] and implications surrounding assessment and accreditation, educational outcomes are increasingly being defined using ‘EPAs’ (entrustable professional activities) [71]. EPAs have been adopted by accreditation bodies in the USA and Canada, and are currently being discussed in Australia. Importantly, EPAs separate performance of job tasks from the more complex array of competencies that reflect the person delivering the care, making it easier to accredit readiness for work. They also incorporate milestones as a means of monitoring progress [72]. Initial work on the MSK standards described above employed the concept of competencies. However, incorporating EPAs into discussions at the medical student level could allow education goals to be more readily tailored to local workforce needs.

MSK anatomy and basic science

Over the past 20 years, many institutions have reduced time devoted to laboratory anatomy or discontinued dissection-based teaching altogether [54, 73, 74]. Although this may be appropriate in certain clinical scenarios, there is a consensus in the literature that RMD medicine relies heavily on a solid foundation in internal and surface MSK anatomy and the ‘sense of touch’ [54, 73, 75, 76]. Medical school educators and students have voiced concerns over the insufficient time allocated to MSK anatomy in undergraduate curricula [45, 50, 54, 73] and there is evidence that anatomy knowledge among HCPs in the field is lacking [75, 77]. A review of methodologies for the teaching of clinical anatomy in rheumatology was published by a Clinical Anatomy Study Group, which met at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the ACR [78]. Modern rheumatology also requires a good understanding of basic science and in particular, immunology. A detailed appreciation of the molecular disease pathways may, however, be unnecessary at undergraduate level.

GALS and pGALS

The Gait, Arms, Legs and Spine (GALS) examination [79, 80] is still regarded by many as a valid MSK screening method and is included in global recommendations for undergraduate RMD curricula [31, 63, 81]. However, evidence suggests that attitudes towards the GALS examination may be changing. A recent study from the UK revealed that although 77% of rheumatologists were taught using GALS, only 21% used this screening tool in clinical practice [82]. Furthermore, according to a 2014 PANLAR survey of Latin American rheumatologists, 32% were not familiar with the GALS examination [51]. A desire to simplify and standardise the teaching of undergraduate MSK clinical examination skills has emerged [82, 83]; the concept of a streamlined core physical examination has also received some support [84, 85].

The paediatric GALS (pGALS) [62, 86] examination tool was designed specifically for use by medical students and PCPs (paediatric Regional Examination of the Musculoskeletal System [pREMS] was developed for postgraduate training) [87]. To further support students and non-specialists who lack confidence in performing the pGALS examination and diagnosing paediatric MSK conditions, a free online resource called Paediatric Musculoskeletal Matters (PMM) [88, 89] was developed (Table 3). While simple paediatric MSK physical examination tools do exist, an adequate knowledge base is a prerequisite for the interpretation of clinical findings [33].

Interprofessional education

In today’s healthcare environment, optimal patient-centred care is dependent upon collaborative practice [96]. The care of patients with RMDs, who are managed by multidisciplinary teams, supports a need for all relevant HCPs to be adequately trained and supported to collaborate in delivering appropriate MSK healthcare: triage and early diagnosis, access to the right care and shared care following diagnosis.

Interprofessional education (IPE) is the process by which students across different disciplines come together to learn common curricular components, with the aim of ensuring effective future collaboration between HCPs and ultimately providing improved patient care. The WHO identified IPE as a key policy issue and is promoting interprofessional training and collaborative practice as part of its future workforce strategy [96, 97]. Specific aims of IPE include understanding different health professionals’ roles, competencies and mindsets and developing attitudes that facilitate effective teamwork [96].

Although RMD education lends itself to IPE, it rarely features in health education programmes, partly due to challenges associated with designing and implementing IPE in health science curricula [98]. A comprehensive literature review, which included 83 IPE studies (2005–2010), suggested that the most common barrier was scheduling (47%), followed by learner-level compatibility (18%) [99]. Among studies that reported administrative support as a key factor for success, financial support (e.g. institutional or grant support) was reported to have the largest positive influence (39%) [99].

The majority of studies investigating the impact of IPE activities focus on outcomes such as student learning about professional roles, team communication and student satisfaction [99]. Several studies have described interprofessional curricular activities at individual institutions. A study conducted in Düsseldorf, Germany, evaluated the implementation of an interprofessional curriculum (medical and physiotherapy students) across different stages of training [98]. The study reported high levels of student satisfaction, high examination pass rates (94%) and 100% student support for the continuation of the interprofessional unit [98].

Considerations for implementation of IPE curricula include identifying the best timing for its incorporation relative to student development, formation of professional identities and methods for learning team management skills. A recent review of 16 US medical schools discussed key issues around IPE implementation including: common IPE practices (simulation, didactic or team-based learning) and activities, IPE activity objectives, overcoming challenges, evaluation of whether learners were meeting planned objectives (instrumental and formative methods), effective faculty development strategies and general best IPE practices [100]. An important finding supported by previous publications [101] was that faculty development, which is crucial for IPE to be effective, was often neglected and under-resourced. The authors also emphasised the lack of broad consensus on measures of IPE as many instruments only measure short-term benefits.

From a broader global perspective, it may be important to expand the concept of IPE to include non-professional healthcare providers (transprofessional education), in recognition of the dependence of developing country healthcare systems on basic and ancillary health workers [102]. Ultimately, inter- and transprofessional teamwork is a fundamental aspect of best practice for the care of patients with RMDs. The more that education reflects this, the better equipped healthcare providers will be to deliver integrated, patient-centred care.

Teaching and learning methods

Curricular reform

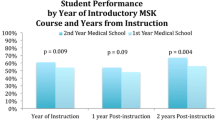

Many studies from the USA and Europe have described curricular reform and implementation at individual institutions, referring to both clinical and pre-clinical MSK courses of varied duration [103,104,105]. A multidisciplinary approach is encouraged [74]. A successful demonstration of this approach is the 6-week multidisciplinary course in MSK medicine for first year medical students, designed by faculty from the departments of orthopaedic surgery, rheumatology and anatomy at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center [105]. The objective-based and problem-centred course was well received. Evaluation revealed significant improvement in the mean score for the competency examination (77.8% vs 59.6% for a historical comparison group, p < 0.05), and all students passed the general MSK physical examination [105].

The University of Minnesota developed an integrated, multidisciplinary MSK course (orthopaedics, rheumatology and physical medicine and rehabilitation) for second year medical students [106]. The study concluded that students were more knowledgeable and confident in MSK examination and succeeded in retaining their physical examination skills after completing the course [106]. In 2006, the University Hospitals of Leicester, England, introduced a 7-week teaching programme in MSK medicine consisting of supervised clinical learning, weekly plenary sessions, a task-based workbook and special interest clinics/experiences [103]. At the end of the course, a small improvement in student performance was observed across all domains tested in a multiple choice question (MCQ) examination [103].

Based on the AMSEC competency standards, the University of Adelaide developed an intensive 6-week MSK medicine ward and outpatient-based clinical attachment integrating orthopaedics, rheumatology and rehabilitation in year 4 of a 6-year undergraduate degree. To address deficiencies in anatomy, three 4-h resource sessions were introduced covering spine, lower limb and upper limb clinical applications (physical examination, radiological interpretation, joint aspirations and joint relocations [107]. A blended learning, ‘flipped classroom’ approach was employed with online tasks and assessments preceding face-to-face interactive clinical problem- or case-based tutorials run by clinical staff. A marked improvement in MSK knowledge, examination skills and clinical reasoning was noted by senior clinicians involved in teaching and OSCE assessments. The students also reported increased confidence and preparedness for practice (M Chehade, Adelaide Medical School internal report data). The online resources trialled were developed to be freely available as part of the AMSEC project [50]. Videotaped OSCEs using simulated patients with asynchronous, annotated performance feedback have recently been introduced and are currently being evaluated with very positive initial impressions (M Chehade, personal communication).

Learning methods and interventions

Improvements in RMD education can only be achieved through a better appreciation of effective learning strategies. It is important to recognise that increasing teaching hours does not guarantee improvements in student competence (e.g. + 1.5-h physical diagnosis [total 10 h]; + 6.5-h lectures [total 18.5 h]; + 5-h laboratory [total 23 h]) [47].

Many interventions have been tested to investigate the effectiveness of different teaching methods, and comprehensive pragmatic and systematic reviews of evidence-based strategies for the teaching of undergraduate RMDs have been published [74, 104]. Examples of successful teaching strategies include the following: small interactive group sessions [81, 108, 109], flipped classroom learning [110], the use of patient educators/partners [109, 111,112,113], team-based learning [114, 115], peer-assisted learning [116, 117], e-learning or computer-assisted learning as a useful adjunct [118,119,120,121] and the use of MSK ultrasound to facilitate the learning of anatomy [122,123,124]. Educators in the field of RMDs have been encouraged to embrace new teaching strategies and learning styles [40, 82, 93].

Modern medicine evolves rapidly and requires graduates to be equipped with the skills to be independent, lifelong learners [97, 119]. The introduction of continuous learning methods should, therefore, begin early on. Strategies involving information science and/or computer technology can help facilitate the transition to active learning. Naranjo et al. present an elegant overview of rheumatology teaching innovations and online resources from the Spanish Society for Rheumatology and three Spanish universities [93] (Table 3). Freely accessible online and app-based educational materials (Table 3) can be especially useful when resources are limited. A subsidised, online course on paediatric rheumatology (postgraduate level) is also available via the EULAR website, with discounted prices for low- and middle-income countries [125].

E-learning materials and teaching apps are being increasingly relied upon as teaching aids; however, efforts are needed to evaluate their effectiveness at imparting desired learning outcomes. The AMSEC competency framework (developed with Mind-Mapping software) may provide an ideal platform for communicating and organising future teaching and learning content for MSK and IPE, from both competency and EPA perspectives [97, 126, 127].

Implementation

The implementation of any curriculum can present challenges and barriers to effective teaching, such as pressures on time and insufficient resources [74]. Undergraduate RMD education is not immune to these; in a recent study involving orthopaedic and rheumatology educators in the UK, 63% of clinicians stated insufficient time as the main barrier to providing effective skills teaching and 31.5% quoted organisational and institutional factors [82]. Challenges and recommendations specific to the teaching of MSK medicine are presented in Table 4.

Assessment and course evaluation

Assessment of learners

Assessment typically involves written MCQ-style tests in the pre-clinical years followed by subject-specific clerkship exams in the clinical years [74]. In their review of MSK education in the USA, Monrad et al. discuss the advantages of different exam formats including one-best-answer and script concordance, which permits assessment of clinical reasoning in a context of uncertainty better reflecting clinical practice [74] (Table 5). There is no doubt that assessment is an integral component of student engagement; hence, the adage ‘assessment drives learning’ [138]. Furthermore, the clinical importance of rheumatology is only likely to be appreciated by medical students if it is given commensurate weighting in examinations [45]. This is particularly relevant in the current climate of limited awareness of social accountability by medical students [139]. For these reasons, inclusion of RMDs in examinations is of paramount importance and rheumatologists should be advocating this [82].

There is also a need for adult rheumatologists, and paediatric rheumatologists, to act as examiners and to ‘teach the teachers’. In the UK, a discriminatory MSK station was introduced to the general paediatrics mandatory examination (MRCPCH) in 2009. However, it is mainly assessed by general paediatricians, who may require support from specialists due to a lack of confidence in MSK examination [55]. The importance of education and of paediatric rheumatology multidisciplinary teams engaging with teaching was highlighted in the UK BSPAR standards of care [140]. The 2016 European Syllabus for Training in Paediatric Rheumatology also stressed the importance of trainees having the skills to teach and be involved in teaching at all levels of medical education [141].

Course evaluation

Prior to implementation of any curriculum changes, it is essential to consider how the intended outcomes will be assessed with respect to both immediate and longer-term impact. Comprehensive frameworks for conducting meaningful evaluations of academic programmes have been provided elsewhere [142]. Commonly used metrics include student satisfaction and student performance, also referred to as ‘assessment gains’ [74] (Table 5).

Evaluation should be distinguished from academic assessment, although assessment gains are often used as part of the programme evaluation. This typically involves comparing examination scores of two groups of students: (1) students who completed a new curriculum versus the last group to complete the old curriculum [103, 143] and (2) students who volunteered or were randomly selected to participate in an intervention versus students who received standard tuition. Some studies have compared overall group performance before and after an intervention as an indicator of successful learning; however, the information provided by this strategy is more limited.

Professional formation and career development

While some RMDs can be managed in primary care, the management of more complicated, multi-system, progressive diseases (or complex examples of common conditions) requires specialist expertise [24]. The global shortfall in rheumatologists alongside the increasing burden of RMDs highlights the urgent need to attract more medical students to a career in rheumatology [66]. Increasing exposure of medical students to RMDs early on is key. Students also need to gain a clear understanding of what rheumatology is, to enable them to distinguish it from related disciplines. Appreciation of the more nuanced factors that influence career choice, such as the perceived distinguishing qualities of clinicians practicing in that field, or the high degree of professional satisfaction is also important [144].

A study reporting how rheumatology fellows defined the qualities of a rheumatologist identified phrases such as ‘intellectual’, ‘intelligent’ and ‘curious', ‘the detective work of fitting things together’ and ‘the ability to deal with uncertainty and complexity’ [144]. Trainees were also attracted to the ‘complexity, variety, and depth of the diseases’ which led them to develop an intellectual interest in rheumatology [144, 145]. Emphasising a ‘bench to bedside’ message may, therefore, be a successful recruitment strategy [145]. Lifestyle frequently features as an important factor in specialty choice; however, it was mentioned by only 14% of trainees when asked what attracted them to rheumatology [144]. While challenging to disentangle, rheumatology fellows appeared to value intellectual reward and a controllable lifestyle above remuneration [145].

A survey of US rheumatology trainees revealed that interest in the specialty typically developed during internship and residency (> 75%). Nevertheless, many residents began developing an interest in rheumatology relatively early on in their medical education (> 25% within the first 3 years of medical school) [144]. The most commonly cited influences on this decision were a clinical rotation in rheumatology (~ 35%), a clinical mentor (28%) and patient interaction (14%) [144]. The multiple factors contributing to career decisions provides opportunities for medical schools to target students using different approaches that rely on their individual strengths [144]. An alternative approach is to minimise the effect of negative factors, such as the shortage of training positions [145].

Recommendations for attracting students to rheumatology:

-

1.

Medical curriculum designers should be encouraged to build early clinical exposure to RMDs and interaction with patients into the undergraduate curriculum. However, it is important that this is approached carefully; patient contact should occur at a point when the student is able to understand and integrate knowledge of basic pathophysiology, disease symptoms, diagnostic tools and treatment pathways.

-

2.

It is the responsibility of rheumatologists to promote and convey enthusiasm for rheumatology and be good role models. Career talks should be incorporated into the curriculum to allow students to gain insight into rheumatology as a career including an accurate appreciation of the lifestyle associated. Rheumatologists should actively engage in teaching and mentoring to inspire the next generation of clinicians.

-

3.

During undergraduate medical education, rheumatology must be presented as the intellectually stimulating, fast-paced field that it is, referring to complex, intriguing clinical cases, sophisticated novel pharmacotherapies and exciting research opportunities [1, 111]. More students should be encouraged to attend congresses (e.g. ACR, EULAR, Advanced Academic Rheumatology Review Course [ADARRC]) which offer free places for students, to provide structured exposure to rheumatology research.

Conclusions

RMDs are a leading cause of disability worldwide [4] and have a profound impact on quality of life through chronic pain, social exclusion, loss of independence, discrimination, loss of employment and diminished work capacity. Recommendations concerning education of the RMD workforce must aim to meet the needs of people with or at risk of RMDs. Policy discussions should focus on how these needs can be met in light of current and future demographic changes, such as ageing, the increasing burden of chronic and non-communicable diseases, multi-morbidity and calls for better integrated patient care.

This white paper highlights the importance of attracting more medical students to a career in rheumatology to manage the more complex conditions. However, a balanced workforce with different levels and types of competency is of fundamental importance to provide holistic patient-centred care. It is therefore imperative that all medical school graduates attain a basic level of RMD competency to ensure that PCPs are able to confidently diagnose, initiate appropriate treatment without delay or refer RMD patients if possible and where necessary. The establishment of an international collaboration of RMD educators and other stakeholders to develop, share, disseminate and evaluate educational resources and strategies to promote the advancement of RMD care globally would be an important step forward.

Teaching for the future must reflect how healthcare will be delivered, which has implications not only on what is being taught but also where, why and to whom [96]. Inter- and transprofessional education are universally recognised as the direction for the future of medical education [102]. However, due to barriers identified herein, blueprints for their successful implementation have yet to be developed. This offers an opportunity for specialties to lead; the field of RMDs in particular has a great need for inter- and transprofessional teamwork and the delivery of RMD care showcases the expertise of this community in providing integrated care. Undergraduate RMD education must, therefore, ensure that all relevant healthcare providers are equipped to operate in this way to deliver the best patient care possible in their local healthcare setting.

References

European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) Taskforce 2017. RheumaMap: a Research Roadmap to transform the lives of people with Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases. Available at: https://www.eular.org/myUploadData/files/RheumaMap.pdf [Last accessed: 20.04.18]

van der Heijde D et al (2018) Common language description of the term rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) for use in communication with the lay public, healthcare providers and other stakeholders endorsed by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). Ann Rheum Dis 77(6):829–832

van der Heijde D et al (2018) Common language description of the term rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) for use in communication with the lay public, healthcare providers, and other stakeholders endorsed by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). Arthritis Rheum 70(6):826–831

GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (2017). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 390(10100): p. 1211–1259

Bevan S (2015) Economic impact of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) on work in Europe. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 29(3):356–373

Woolf AD, Pfleger B (2003) Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ 81(9):646–656

United States Bone and Joint Initiative. The burden of musculoskeletal diseases in the United States – prevalence, societal and economic cost. Available at: http://www.boneandjointburden.org/docs/The%20Burden%20of%20Musculoskeletal%20Diseases%20in%20the%20United%20States%20(BMUS)%203rd%20Edition%20(Dated%2012.31.16).pdf [Last accessed: 20.04.18]

European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR). Ten facts about rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) – 2017 Factsheet. Available at: https://www.eular.org/myUploadData/files/EULAR_Ten_facts_about_RMDs.pdf [Last accessed: 20.04.18]

World Forum on Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases (WFRMD). Available at: www.wfrmd.org [Last accessed: 20.04.18]

Al Maini M et al (2015) The global challenges and opportunities in the practice of rheumatology: white paper by the World Forum on Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases. Clin Rheumatol 34(5):819–829

Woolf AD, Gabriel S (2015) Overcoming challenges in order to improve the management of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases across the globe. Clin Rheumatol 34(5):815–817

Kern, D.E., et al., Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach. 1998: The Johns Hopkins University Press

United Kingdom Department of Health (2006). A joint responsibility: doing it differently. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130124073659/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4138412.pdf [Last accessed: 22.05.18]

Jordan KP, Kadam UT, Hayward R, Porcheret M, Young C, Croft P (2010) Annual consultation prevalence of regional musculoskeletal problems in primary care: an observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 11:144

Pinney SJ, Regan WD (2001) Educating medical students about musculoskeletal problems. Are community needs reflected in the curricula of Canadian medical schools? J Bone Joint Surg Am 83-a(9):1317–1320

Lynch JR, Gardner GC, Parsons RR (2005) Musculoskeletal workload versus musculoskeletal clinical confidence among primary care physicians in rural practice. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 34(10):487–491

Mulhall KJ, Masterson E (2005) Relating undergraduate musculoskeletal medicine curricula to the needs of modern practice. Ir J Med Sci 174(2):46–51

Gunz AC, Canizares M, MacKay C, Badley EM (2012) Magnitude of impact and healthcare use for musculoskeletal disorders in the paediatric: a population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 13:98

Al Saleh J et al (2016) The prevalence and the determinants of musculoskeletal diseases in Emiratis attending primary health care clinics in Dubai. Oman Med J 31(2):117–123

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2016). Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Available at: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ [Last accessed: 22.05.18]

Barbour KE, Helmick CG, Boring M, Brady TJ (2017) Vital signs: prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation - United States, 2013-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66(9):246–253

Anandacoomarasamy A, Caterson I, Sambrook P, Fransen M, March L (2008) The impact of obesity on the musculoskeletal system. Int J Obes 32(2):211–222

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) (2017) Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 390(10113):2627–2642

Woolf AD (2007) Healthcare services for those with musculoskeletal conditions: a rheumatology service. Recommendations of the European Union of Medical Specialists Section of Rheumatology/European Board of Rheumatology 2006. Ann Rheum Dis 66(3):293–301

National Quality Board (NQB) (2016) Supporting NHS providers to deliver the right staff, with the right skills, in the right place at the right time [Last accessed: 22.05.18].

Akesson K, Dreinhofer KE, Woolf AD (2003) Improved education in musculoskeletal conditions is necessary for all doctors. Bull World Health Organ 81(9):677–683

Munoz-Louis R, Medrano-Sanchez J, Montufar R (2015) Rheumatoid arthritis in Latin America: challenges and solutions to improve its diagnosis and treatment training for medical professionals. Clin Rheumatol 34(Suppl 1):S67–S70

Woolf AD (2000) The bone and joint decade 2000-2010. Ann Rheum Dis 59(2):81–82

US Bone and Joint Initiative – Project 100. Available at: https://www.usbji.org/programs/project-100 [Last accessed: 15.06.18]

Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) (2005) Report VII contemporary issues in medicine: Musculoskeletal medicine education, medical school objectives project. Available at: https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Contemporary%20Issues%20in%20Med%20Musculoskeletal%20Med%20Report%20VII%20.pdf [Accessed 20.04.18]

Woolf AD, Walsh NE, Akesson K (2004) Global core recommendations for a musculoskeletal undergraduate curriculum. Ann Rheum Dis 63(5):517–524

Bernstein J, Garcia GH, Guevara JL, Mitchell GW (2011) Progress report: the prevalence of required medical school instruction in musculoskeletal medicine at decade’s end. Clin Orthop Relat Res 469(3):895–897

Goff I, Boyd DJ, Wise EM, Jandial S, Foster HE (2014) Paediatric musculoskeletal learning needs for general practice trainees: achieving an expert consensus. Educ Prim Care 25(5):249–256

Jandial S, Stewart J, Foster HE (2015) What do they need to know: achieving consensus on paediatric musculoskeletal content for medical students. BMC Med Educ 15:171

Louthrenoo W (2015) An insight into rheumatology in Thailand. Nat Rev Rheumatol 11(1):55–61

DiGiovanni BF, Sundem LT, Southgate RD, Lambert DR (2016) Musculoskeletal medicine is underrepresented in the American medical school clinical curriculum. Clin Orthop Relat Res 474(4):901–907

Day CS, Yeh AC, Franko O, Ramirez M, Krupat E (2007) Musculoskeletal medicine: an assessment of the attitudes and knowledge of medical students at Harvard Medical School. Acad Med 82(5):452–457

Clawson DK, Jackson DW, Ostergaard DJ (2001) It’s past time to reform the musculoskeletal curriculum. Acad Med 76(7):709–710

Abou-Raya A, Abou-Raya S (2010) The inadequacies of musculoskeletal education. Clin Rheumatol 29(10):1121–1126

Bandinelli F et al (2011) Rheumatology education in Europe: results of a survey of young rheumatologists. Clin Exp Rheumatol 29(5):843–845

Nottidge TE, Ekrikpo U, Ifesanya AO, Nnabuko RE, Dim EM, Udoinyang CI (2012) Pre-internship Nigerian medical graduates lack basic musculoskeletal competency. Int Orthop 36(4):853–856

Ramani S, Ring BN, Lowe R, Hunter D (2010) A pilot study assessing knowledge of clinical signs and physical examination skills in incoming medicine residents. J Grad Med Educ 2(2):232–235

Queally JM, Kiely PD, Shelly MJ, O’Daly BJ, O’Byrne JM, Masterson EL (2008) Deficiencies in the education of musculoskeletal medicine in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci 177(2):99–105

Matzkin E, Smith MEL, Freccero CD, Richardson AB (2005) Adequacy of education in musculoskeletal medicine. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87(2):310–314

Menon J, Patro DK (2009) Undergraduate orthopedic education: is it adequate? Indian J Orthop 43(1):82–86

Jones JK (2001) An evaluation of medical school education in musculoskeletal medicine at the University of the West Indies. Barbados West Indian Med J 50(1):66–68

Weiss K, Curry E, Matzkin E (2015) Assessment of medical school musculoskeletal education. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 44(3):E64–E67

Skelley NW et al. (2012) Medical student musculoskeletal education: an institutional survey. J Bone Joint Surg Am 94(19): e146(1–7)

Schmale GA (2005) More evidence of educational inadequacies in musculoskeletal medicine. Clin Orthop Relat Res 437:251–259

Chehade MJ, Bachorski A (2008) Development of the Australian core competencies in musculoskeletal basic and clinical science project - phase 1. Med J Aust 189(3):162–165

Caballero-Uribe, C.V., Education in Rheumatology in Latin America. ACR 2014. [Latin American Study Group; oral presentation 153 B]

Cabrera Pivaral CE, Gutiérrez González TY, Gámez Nava JI, Nava A, Villa Manzano AI, Luce González E (2009) Clinical competence for autoimmune and non-autoimmune rheumatic disorders in primary care. Rev Alerg Mex 56(1):18–22

Homoud AH (2012) Knowledge, attitude, and practice of primary health care physicians in the management of osteoarthritis in Al-Jouf province. Saudi Arabia Niger Med J 53(4):213–219

Al-Nammari SS, James BK, Ramachandran M (2009) The inadequacy of musculoskeletal knowledge after foundation training in the United Kingdom. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 91(11):1413–1418

Myers A, McDonagh J, Gupta K, Hull R, Barker D, Kay LJ, Foster HE (2004) More ‘cries from the joints’: assessment of the musculoskeletal system is poorly documented in routine paediatric clerking. Rheumatology (Oxford) 43(8):1045–1049

Jandial S, Myers A, Wise E, Foster HE (2009) Doctors likely to encounter children with musculoskeletal complaints have low confidence in their clinical skills. J Pediatr 154(2):267–271

Jandial S, Rapley T, Foster H (2009) Current teaching of paediatric musculoskeletal medicine within UK medical schools--a need for change. Rheumatology (Oxford) 48(5):587–590

Pineda C, Caballero-Uribe CV (2015) Challenges and opportunities for diagnosis and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in Latin America. Clin Rheumatol 34(Suppl 1):S5–S7

da Mota LM et al (2015) Rheumatoid arthritis in Latin America: the importance of an early diagnosis. Clin Rheumatol 34(Suppl 1):S29–S44

Burgos Vargas, R. and M.H. Cardiel, Rheumatoid arthritis in Latin America. Important challenges to be solved. Clin Rheumatol, 2015. 34 Suppl 1: p. S1–3

Foster HE, Minden K, Clemente D, Leon L, McDonagh JE, Kamphuis S, Berggren K, van Pelt P, Wouters C, Waite-Jones J, Tattersall R, Wyllie R, Stones SR, Martini A, Constantin T, Schalm S, Fidanci B, Erer B, Dermikaya E, Ozen S, Carmona L (2017) EULAR/PReS standards and recommendations for the transitional care of young people with juvenile-onset rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 76(4):639–646

Foster HE, Jandial S (2013) pGALS - paediatric Gait Arms Legs and Spine: a simple examination of the musculoskeletal system. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 11(1):44

Khawaja K, Al-Maini M (2017) Access to pediatric rheumatology care for Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis in the United Arab Emirates. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 15(1):41

Reveille JD, Muñoz R, Soriano E, Albanese M, Espada G, Lozada CJ, Montúfar RA, Neubarth F, Vasquez GM, Zummer M, Sheen R, Caballero-Uribe CV, Pineda C (2016) Review of current workforce for rheumatology in the countries of the Americas 2012-2015. J Clin Rheumatol 22(8):405–410

Cox A, Piper S, Singh-Grewal D (2017) Pediatric rheumatology consultant workforce in Australia and New Zealand: the current state of play and challenges for the future. Int J Rheum Dis 20(5):647–653

Watad A, al-Saleh J, Lidar M, Amital H, Shoenfeld Y (2017) Rheumatology in the Middle East in 2017: clinical challenges and research. Arthritis Res Ther 19(1):149

Boyer MI (2005) Objectives of undergraduate medical education in musculoskeletal surgery and medicine. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87(3):684–685

Mayer RS, Baima J, Bloch R, Braza D, Newcomer K, Sherman A, Sullivan W (2009) Musculoskeletal education for medical students. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 88(10):791–797

Wadey VM, Tang ET, Abelseth G, Dev P, Olshen RA, Walker D (2007) Canadian multidisciplinary core curriculum for musculoskeletal health. J Rheumatol 34(3):567–580

Touchie C, ten Cate O (2016) The promise, perils, problems and progress of competency-based medical education. Med Educ 50(1):93–100

Ten Cate O et al (2015) Curriculum development for the workplace using Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs): AMEE Guide No. 99. Med Teach 37(11):983–1002

Tekian A, Hodges BD, Roberts TE, Schuwirth L, Norcini J (2015) Assessing competencies using milestones along the way. Med Teach 37(4):399–402

Day CS, Ahn CS (2010) Commentary: the importance of musculoskeletal medicine and anatomy in medical education. Acad Med 85(3):401–402

Monrad SU, Zeller JL, Craig CL, DiPonio LA (2011) Musculoskeletal education in US medical schools: lessons from the past and suggestions for the future. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 4(3):91–98

Navarro-Zarza JE et al (2013) AB1408 knowledge of clinical anatomy by rheumatology fellows and rheumatologists in Latin America. Ann Rheum Dis 71:718

Boon JM, Meiring JH, Richards PA (2002) Clinical anatomy as the basis for clinical examination: development and evaluation of an introduction to clinical examination in a problem-oriented medical curriculum. Clin Anat 15(1):45–50

Kalish RA, Canoso JJ (2007) Clinical anatomy: an unmet agenda in rheumatology training. J Rheumatol 34(6):1208–1211

Torralba KD, Villaseñor-Ovies P, Evelyn CM, Koolaee RM, Kalish RA (2015) Teaching of clinical anatomy in rheumatology: a review of methodologies. Clin Rheumatol 34(7):1157–1163

Plant MJ, Linton S, Dodd E, Jones PW, Dawes PT (1993) The GALS locomotor screen and disability. Ann Rheum Dis 52(12):886–890

European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) School of Rheumatology. Video production: undergraduate training in physical examination of the musculoskeletal system. Available at: https://www.eular.org/edu_training_dvd.cfm [Last accessed: 20.04.18]

Perrig M, Berendonk C, Rogausch A, Beyeler C (2016) Sustained impact of a short small group course with systematic feedback in addition to regular clinical clerkship activities on musculoskeletal examination skills -a controlled study. BMC Med Educ 16:35

Blake T (2014) Teaching musculoskeletal examination skills to UK medical students: a comparative survey of rheumatology and Orthopaedic education practice. BMC Med Educ 14:62

Coady D, Walker D, Kay L (2003) The attitudes and beliefs of clinicians involved in teaching undergraduate musculoskeletal clinical examination skills. Med Teach 25(6):617–620

Haring CM, van der Meer JW, Postma CT (2013) A core physical examination in internal medicine: what should students do and how about their supervisors? Med Teach 35(9):e1472–e1477

Gowda D, Blatt B, Fink MJ, Kosowicz LY, Baecker A, Silvestri RC (2014) A core physical exam for medical students: results of a national survey. Acad Med 89(3):436–442

Foster HE, Kay LJ, Friswell M, Coady D, Myers A (2006) Musculoskeletal screening examination (pGALS) for school-age children based on the adult GALS screen. Arthritis Rheum 55(5):709–716

Foster H, Kay L, May C, Rapley T (2011) Pediatric regional examination of the musculoskeletal system: a practice- and consensus-based approach. Arthritis Care Res 63(11):1503–1510

Paediatric Musculoskeletal Matters. Available at: http://www.pmmonline.org/ [Last accessed: 20.04.18]

Smith N, Rapley T, Jandial S, English C, Davies B, Wyllie R, Foster HE (2016) Paediatric musculoskeletal matters (pmm)--collaborative development of an online evidence based interactive learning tool and information resource for education in paediatric musculoskeletal medicine. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 14(1):1

EULAR Ultrasound Scanning App. Available at: http://ultrasound.eular.org/#/home [Last accessed: 28.03.18]

Paediatric Musculoskeletal Matters (pmm) India. Available at: http://www.pmmonlineindia.org/about-pmm [Last accessed: 20.04.18]

Pan-American League of Associations for Rheumatology (PANLAR). Panlar Edu. Available at: https://sites.google.com/reumati.co/reumatologia/ [Last accessed: 19.02.18]

Naranjo A, de Toro J, Nolla JM (2015) The teaching of rheumatology at the University. The journey from teacher based to student-centered learning. Reumatol Clin 11(4):196–203

Reumacademia. Available at: https://www.ser.es/profesionales/que-hacemos/formacion/otras-iniciativas/reumacademia/ [Last accessed: 28.03.18]

Youtube channel “Reumatologia chuac”. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJ70tZRtLcI1Y3xElP5BQ5A [Last accessed: 28.03.18]

World Health Organization (WHO) (2013). Transforming and scaling up health professionals’ education and training: guidelines 2013. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/93635/1/9789241506502_eng.pdf [Last accessed: 20.04.18]

Chehade MJ, Gill TK, Kopansky-Giles D, Schuwirth L, Karnon J, McLiesh P, Alleyne J, Woolf AD (2016) Building multidisciplinary health workforce capacity to support the implementation of integrated, people-centred models of care for musculoskeletal health. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 30(3):559–584

Sander, O., et al., Interprofessional education as part of becoming a doctor or physiotherapist in a competency-based curriculum. GMS J Med Educ, 2016. 33(2): p. Doc15

Abu-Rish E, Kim S, Choe L, Varpio L, Malik E, White AA, Craddick K, Blondon K, Robins L, Nagasawa P, Thigpen A, Chen LL, Rich J, Zierler B (2012) Current trends in interprofessional education of health sciences students: a literature review. J Interprof Care 26(6):444–451

West C, Graham L, Palmer RT, Miller MF, Thayer EK, Stuber ML, Awdishu L, Umoren RA, Wamsley MA, Nelson EA, Joo PA, Tysinger JW, George P, Carney PA (2016) Implementation of interprofessional education (IPE) in 16 U.S. medical schools: common practices, barriers and facilitators. J Interprofessional Educ Pract 4:41–49

Everard KM et al (2014) Exploring interprofessional education in the family medicine clerkship: a CERA study. Fam Med 46(6):419–422

Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, Fineberg H, Garcia P, Ke Y, Kelley P, Kistnasamy B, Meleis A, Naylor D, Pablos-Mendez A, Reddy S, Scrimshaw S, Sepulveda J, Serwadda D, Zurayk H (2010) Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 376(9756):1923–1958

Williams SC et al (2010) A new musculoskeletal curriculum: has it made a difference? J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 92(1):7–11

O’Dunn-Orto A et al (2012) Teaching musculoskeletal clinical skills to medical trainees and physicians: a best evidence in medical education systematic review of strategies and their effectiveness: BEME Guide No. 18. Med Teach 34(2):93–102

Bilderback K, Eggerstedt J, Sadasivan KK, Seelig L, Wolf R, Barton S, McCall R, Chesson AL Jr, Marino AA (2008) Design and implementation of a system-based course in musculoskeletal medicine for medical students. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90(10):2292–2300

Saleh K et al (2004) Development and evaluation of an integrated musculoskeletal disease course for medical students. J Bone Joint Surg Am 86-a(8):1653–1658

Au J, Palmer E, Johnson I, Chehade M (2018) Evaluation of the utility of teaching joint relocations using cadaveric specimens. BMC Med Educ 18(1):41

Kelly M et al (2017) Undergraduate clinical teaching in orthopedic surgery: a randomized control trial comparing the effect of case-based teaching and bedside teaching on musculoskeletal OSCE performance. J Surg Educ

Oswald AE et al (2008) The current state of musculoskeletal clinical skills teaching for preclerkship medical students. J Rheumatol 35(12):2419–2426

El Miedany, Y., et al., Flipped learning: can rheumatology lead the shift in medical education? Curr Rheumatol Rev, 2018

Raj N, Badcock LJ, Brown GA, Deighton CM, O’Reilly SC (2006) Undergraduate musculoskeletal examination teaching by trained patient educators--a comparison with doctor-led teaching. Rheumatology (Oxford) 45(11):1404–1408

Haq I, Fuller J, Dacre J (2006) The use of patient partners with back pain to teach undergraduate medical students. Rheumatology (Oxford) 45(4):430–434

Hassell A (2012) Patient instructors in rheumatology. Med Teach 34(7):539–542

Reimschisel T, Herring AL, Huang J, Minor TJ (2017) A systematic review of the published literature on team-based learning in health professions education. Med Teach 39(12):1227–1237

Luetmer, M.T., et al., Simulating the multi-disciplinary care team approach: enhancing student understanding of anatomy through an ultrasound-anchored interprofessional session. Anat Sci Educ, 2017

Graham K, Burke JM, Field M (2008) Undergraduate rheumatology: can peer-assisted learning by medical students deliver equivalent training to that provided by specialist staff? Rheumatology (Oxford) 47(5):652–655

Perry, M.E., et al., Can training in musculoskeletal examination skills be effectively delivered by undergraduate students as part of the standard curriculum? Rheumatology (Oxford), 2010. 49(9): p. 1756–61

D’Alessandro DM, Lewis TE, D’Alessandro MP (2004) A pediatric digital storytelling system for third year medical students: the virtual pediatric patients. BMC Med Educ 4:10

Wilson AS, Goodall JE, Ambrosini G, Carruthers DM, Chan H, Ong SG, Gordon C, Young SP (2006) Development of an interactive learning tool for teaching rheumatology--a simulated clinical case studies program. Rheumatology (Oxford) 45(9):1158–1161

Bateman HE, Sterrett AG, Alias A, Rodriguez EJ, Westphal L, Carter J, Vasey F, Valeriano-Marcet J (2012) Innovative virtual interactive teaching tool “Arthur” for clinical diagnosis of musculoskeletal diseases. J Clin Rheumatol 18(3):151–152

World Health Organization (2015). eLearning for undergraduate health professional education: a systematic review informing a radical transformation of health workforce development. Available at: http://www.who.int/hrh/documents/14126-eLearningReport.pdf [Last accessed: 28.02.18]

Wright SA, Bell AL (2008) Enhancement of undergraduate rheumatology teaching through the use of musculoskeletal ultrasound. Rheumatology (Oxford) 47(10):1564–1566

Walrod BJ et al (2017) Does ultrasound-enhanced instruction of musculoskeletal anatomy improve physical examination skills of first-year medical students? J Ultrasound Med

Tshibwabwa ET, Groves HM, Levine MA (2007) Teaching musculoskeletal ultrasound in the undergraduate medical curriculum. Med Educ 41(5):517–518

European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR). EULAR / PReS Online Course in Paediatric Rheumatology. Available at: https://www.eular.org/edu_online_course_paediatric.cfm [Last accessed: 19.02.18]

Chehade MJ, Burgess TA, Bentley DJ (2011) Ensuring quality of care through implementation of a competency-based musculoskeletal education framework. Arthritis Care Res 63(1):58–64

Chehade, M., D. Bentley, and T. Burgess, The AMSEC project--a model for collaborative interprofessional and interdisciplinary evidence-based competency education in health. J Interprof Care, 2011. 25(3): p. 218–20.a

Coady DA, Walker DJ, Kay LJ (2004) Teaching medical students musculoskeletal examination skills: identifying barriers to learning and ways of overcoming them. Scand J Rheumatol 33(1):47–51

Sivera F et al (2016) Rheumatology training experience across Europe: analysis of core competences. Arthritis Res Ther 18(1):213

Nikiphorou E, Alunno A, Carmona L, Kouloumas M, Bijlsma J, Cutolo M (2017) Patient-physician collaboration in rheumatology: a necessity. RMD Open 3(1):e000499

Mathieu S, Couderc M, Glace B, Tournadre A, Malochet-Guinamand S, Pereira B, Dubost JJ, Soubrier M (2013) Construction and utilization of a script concordance test as an assessment tool for DCEM3 (5th year) medical students in rheumatology. BMC Med Educ 13:166

Yudkowsky R, Otaki J, Lowenstein T, Riddle J, Nishigori H, Bordage G (2009) A hypothesis-driven physical examination learning and assessment procedure for medical students: initial validity evidence. Med Educ 43(8):729–740

Connell KJ, Sinacore JM, Schmid FR, Chang RW, Perlman SG (1993) Assessment of clinical competence of medical students by using standardized patients with musculoskeletal problems. Arthritis Rheum 36(3):394–400

Raj N, Badcock LJ, Brown GA, Deighton CM, O’Reilly SC (2007) Design and validation of 2 objective structured clinical examination stations to assess core undergraduate examination skills of the hand and knee. J Rheumatol 34(2):421–424

Siddharthan T, Soares S, Wang HH, Holt SR (2017) Objective structured clinical examination-based teaching of the musculoskeletal examination. South Med J 110(12):761–764

National Board of Medical Examiners. Musculoskeletal Subject Examination. Available at: http://www.nbme.org/Schools/Subject-Exams/Subjects/musculo.html [Last accessed: 20.04.18]

Basu S, Roberts C, Newble DI, Snaith M (2004) Competence in the musculoskeletal system: assessing the progression of knowledge through an undergraduate medical course. Med Educ 38(12):1253–1260

Newble DI, Jaeger K (1983) The effect of assessments and examinations on the learning of medical students. Med Educ 17(3):165–171

McCrea ML, Murdoch-Eaton D (2014) How do undergraduate medical students perceive social accountability? Med Teach 36(10):867–875

Davies K, Cleary G, Foster H, Hutchinson E, Baildam E, on behalf of the British Society of Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology (2010) BSPAR standards of care for children and young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 49(7):1406–1408

Paediatric Rheumatology European Society (PReS) and European Academy of Paediatrics (EAP) (2016). European Syllabus for Training in Paediatric Rheumatology (March 2016). Available at: http://eapaediatrics.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Pediatric-Rheumatology-Syllabus-2016-final-version-2.pdf [Last accessed: 20.02.18].

The Undergraduate Committee of the University Faculty Senate and the Faculty Council of Community Colleges of the State University of New York. Guide for the Evaluation of Undergraduate Academic Programs. Available at: https://www.delhi.edu/kenny/about/institutional-effectiveness/pdfs/program-eval-guide-2012.pdf [Last accessed: 20.04.18]

Day CS et al (2011) Early assessment of a new integrated preclinical musculoskeletal curriculum at a medical school. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 40(1):14–18

Kolasinski SL, Bass AR, Kane-Wanger GF, Libman BS, Sandorfi N, Utset T (2007) Subspecialty choice: why did you become a rheumatologist? Arthritis Rheum 57(8):1546–1551

Rahbar L, Moxley G, Carleton D, Barrett C, Brannen J, Thacker L, Waterhouse EJ, Roberts WN (2010) Correlation of rheumatology subspecialty choice and identifiable strong motivations, including intellectual interest. Arthritis Care Res 62(12):1796–1804

Funding

Financial support was provided by the World Forum on Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases (WFRMD), managed by the K.I.T. Group. Writing support and editorial assistance were provided by Arianna Psichas, PhD, and Debbie Nixon, DPhil, from Costello Medical, Cambridge, UK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mustafa Al Maini, MD, MSc, FRCPC, is Acting Chief Medical Officer at Mafraq Hospital, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Founder and Course Director of the Advanced Academic Rheumatology Review Course (ADARRC) and Chair of the World Forum on Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases (WFRMD).

Yousef Al Weshahi, MD, PhD, Director of Continuing Professional Development at the Oman Medical Specialty Board, Muscat, Oman.

Helen E. Foster, MD MBBS (Hons), FRCP, FRCPH, DCH, Cert Clin ED, is Professor of Paediatric Rheumatology at Newcastle University Medicine, Malaysia and Co-Chair of the Paediatric Task Force of the Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health.

Mellick J. Chehade, PhD, MBBS, FRACS, GCert. Online Learning (H.Ed), Associate Professor, Orthopaedic Surgeon and past President, Australasian Orthopaedic Trauma Society. He specialises in MSK education, fragility fractures and frailty transdisciplinary research and knowledge translation. He established AMSEC and chairs the Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health Education Task Force.

Sherine E. Gabriel, MD, MSc, is Distinguished Professor and Dean, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, USA. She was also Dean of Mayo Medical School, where she developed the Clinical Research Training and Career Development Programs, and Co-Principal Investigator and Director of Education, NIH-funded Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program.

Jamal Al Saleh, MD, FRCP, is Consultant Rheumatologist, Head of Unit and Director of Medical Affairs at Dubai Hospital, and Senior Lecturer at the Dubai Medical School, United Arab Emirates. He was formerly Chair of the Arab League Against Rheumatism (ArLAR).

Humaid Al Wahshi, MD, FRCP, is Senior Consultant Internist, Rheumatologist and Immunologist at the Royal Hospital, Muscat, and Senior Clinical Lecturer at the College of Medicine, Sultan Qaboos University, Sultanate of Oman. He is Chair of the Arab League Against Rheumatism (ArLAR) and President of the Oman Society of Rheumatology.

Johannes W. J. Bijlsma, MD, PhD, is Professor of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology at Utrecht University, Netherlands, and is President of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR).

Maurizio Cutolo, is Professor of Rheumatology, Director of the Research Laboratories and Clinical Academic Unit of Rheumatology, and of the Academic Postgraduate School of Rheumatology at the University of Genova, Italy. He is former President of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR).

Sharad Lakhanpal, is Clinical Professor of Internal Medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, USA, and immediate past President of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR).

Manda Venkatramana, FRCSEd, is Vice Provost Academics and Dean, College of Medicine, Gulf Medical University in Ajman, and Consultant Surgeon at Thumbay Hospital, Ajman, United Arab Emirates.

Carlos Pineda, MD, PhD, is Researcher at the National Institute of Rehabilitation, Mexico City, Mexico, and past President of the Pan-American League of Associations for Rheumatology (PANLAR) and past Coordinator of the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR).

Anthony D. Woolf, BSc, MD MBBS, FRCP, is Clinical Director, NIHR Clinical Research Network South West Peninsula, Consultant, Royal Cornwall Hospital, and Honorary Professor, University of Exeter Medical School, Truro, UK. He is Chair, Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance (ARMA), and founding member and former Chair, Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Declaration of interest

Mustafa Al Maini: None declared; Yousef Al Weshahi: None declared; Helen E. Foster: Advisory boards and/or unrestricted educational grants and/or honoraria from: Pfizer, AbbVie, Roche, Sobi, Sanofi Genzyme and BioMarin; Mellick J. Chehade: None declared; Jamal Al Saleh: None declared; Humaid Al Wahshi: None declared; Johannes W. J. Bijlsma: None declared; Maurizio Cutolo: None declared; Sherine E. Gabriel: None declared; Sharad Lakhanpal: None declared; Manda Venkatramana: None declared; Carlos Pineda: None declared; Anthony D. Woolf: None declared.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Part of the Topical Collection entitled ‘Empowering Medical Education to Transform: Learnings from an international perspective’

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Maini, M., Al Weshahi, Y., Foster, H.E. et al. A global perspective on the challenges and opportunities in learning about rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in undergraduate medical education. Clin Rheumatol 39, 627–642 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04544-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04544-y