Abstract

Purpose

Approximately 20 million individuals worldwide undergo inguinal hernia surgery annually. The Lichtenstein technique is the most commonly used surgical procedure in this setting. The objective of this study was to revisit this technique and present ten recommendations based on the best practices.

Methods

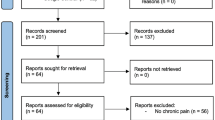

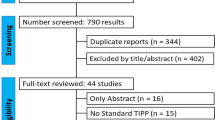

PubMed and Scientific Electronic Library Online were used to systematically search for articles about the Lichtenstein technique and its modifications. Literature regarding this technique and surgical strategies to prevent chronic pain were the basis for formulating ten recommendations for best practices during Lichtenstein surgery.

Results

Ten recommendations were proposed based on best practices in the Lichtenstein technique: neuroanatomical assessment, chronic pain prevention, pragmatic neurectomy, spermatic cord structure management, femoral canal assessment, hernia sac management, mesh characteristics, fixation, recurrence prevention, and surgical convalescence.

Conclusion

The ten recommendations are practical ways to achieve a safe and successful procedure. We fell that following these recommendations can improve surgical outcomes using the Lichtenstein technique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Inguinal hernias (IH) constitute 75% of abdominal wall defects, with a lifetime risk ranging from 27 to 43% in men and 3–6% in women [1, 2]. IH surgery is one of the most common procedures worldwide, with an estimated 20 million individuals undergoing it annually [1].

The Lichtenstein tension-free technique was introduced in 1984 by Dr. Irving Lichtenstein, who aimed to eliminate the adverse effects of suture tension observed using previous techniques. Understanding the metabolic origin of IH (i.e., collagen metabolism dysfunction and type 1/type 3 collagen ratio) is pivotal in developing this technique [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. The Lichtenstein technique involves placing a polypropylene mesh between the floor of the inguinal region and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle (EOM). This mesh eliminates the need for tension sutures and the use of compromised tissues to repair IH. Increased intra-abdominal pressure during effort leads to EOM contraction, which exerts counterpressure on the mesh, thus effectively utilizing the intra-abdominal pressure for repair [3, 6]. The surgical outcomes of this technique have proved highly promising, with a recurrence rate of less than 1% [5, 6, 8, 9].

A review of the initial cases identified four cases of recurrence (three resulting from juxtaposed mesh fixation in the pubic symphysis and one from ruptured mesh fixation in the inguinal ligament). Given these technical flaws, Amid et al. (1989) proposed modifications, including increasing the mesh size (7.5 × 15 cm), a 2 cm overlap in the pubic tubercle region, crossing the mesh edges in the spermatic cord (SC), and using interrupted stitches on the upper edge of the mesh. The proposed modifications enhanced surgical outcomes and resulted in the current Amid-modified Lichtenstein technique, a globally recognized surgical procedure [5,6,7,8, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

This technique presents five principles based on the dynamic physical characteristics of the abdominal wall and intra-abdominal pressure. The principles are influenced by modified intra-abdominal pressure, which can vary from 8 cm of water [H2O] when supine to 80 cm H2O with physical effort and mesh shrinkage in living tissue, resulting in contraction. Most authors describe the mesh shrinkage as approximately 20%. Shrinkage is linked to the scarring of the recipient tissue, which leads to mesh contraction as the tissue heals [4, 6, 13].

The five principles described by Lichtenstein are as follows: (i) use of a footprint-shaped mesh measuring approximately 7.5 × 15 cm, with a medial overlap of 2 cm in the pubic symphysis region, 3–4 cm above the inguinal triangle and 5–6 cm lateral to the internal inguinal ring; (ii) crossing the mesh edges behind the SC to avoid lateral recurrence; (iii) suturing the mesh with two separate stitches to the sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle and to the aponeurosis of the internal oblique muscle (IOM) to prevent iliohypogastric (IHG) nerve injury and suturing the lower edge of the mesh to the inguinal ligament with continuous nonabsorbable suture (passing the needle three to four times) to prevent mesh mobilization; (iv) maintaining the mesh slightly relaxed or shaped like a dome to contain transversalis fascia protrusion during physical effort, thus compensating for mesh counter-traction; and (v) visualizing and protecting the three inguinal nerves: the ilioinguinal (II) nerve, the IHG nerve, and the genital branch of the genitofemoral (GNF) nerve.

Recent data from Brazil reveals that almost all (99.2%) of the more than 700,000 IH surgeries conducted with the Unified Health System between 2017 and 2022 employed the open technique [15]. A recent population study with over 260,000 patients in Spain indicated an open surgery rate of 94.3% [17]. The review led by the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative also highlighted a significant rate of open surgery (42%) among North American surgeons [18]. Although precise recent data from all countries are unavailable, the Lichtenstein surgery remains the preferred choice for most surgeons [16]. The American College of Surgeons endorsed the Lichtenstein technique as the gold standard surgery [3, 6] for IH, and the main consensus statements from hernia and abdominal wall societies currently recommend the Lichtenstein technique as the preferred surgical approach for anterior IH repair with mesh [1,2,3, 5, 6, 10,11,12, 19].

Literature regarding technical steps of the Lichtenstein surgery, modifications, and chronic pain prevention measures are the utmost importance to achieve a safe and successful procedure. Studies have shown the need to improve neuroanatomical knowledge of the inguinal region and the technical steps of the Lichtenstein technique [12,13,14,15,16, 20]. This study aims to present ten recommendations grounded in the five principles of the Lichtenstein technique, supported by current scientific evidence. These recommendations aim to revisit the technique and outline best practices for treating IH using the Lichtenstein technique.

Methods

This descriptive-analytical study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of our university. PubMed and Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) were used to systematically search for articles about the Lichtenstein technique and its modifications. The search included studies published in English or Portuguese between 1987 and 2023. Literature regarding this technique and surgical strategies to prevent chronic pain were the basis for formulating ten recommendations for best practices during Lichtenstein surgery.

Results

This study presents ten recommendations for treating IH using the Lichtenstein technique. Following we described detailed 10 recommendations we consider a practical guide so that surgeons with all levels of expertise can achieve a safe and successful procedure.

Neuroanatomical assessment

Recommendation 1

Identification of the II nerve, the IHG nerve, and the genital branch of the GNF nerve.

Identifying the three nerves is fundamental step in IH surgery. (Figures 1 and 2) [1, 4,5,6, 8, 12,13,14]. These nerves can be identified by open repair in 70–90% of cases [20, 21, 23]. Although this technical step can increase the surgical time by approximately five minutes, it offers countless benefits to patients with chronic pain [21,22,23].

The II nerve is the most anterior and is easily identifiable at the opening of the EOM aponeurosis. It penetrates the IOM into the inguinal canal, runs ventrally parallel to the SC, and exits through an external inguinal ring. The IHG nerve is identified when the EOM layer is separated from the IOM. It has a visible part that passes laterally through the IOM aponeurosis (approximately 2.4 cm) and a hidden part that passes through the IOM fibers [20, 21, 23]. The genital branch of the GNF nerve, which has a small diameter, is the most challenging nerve to identify. In men, it generally penetrates the deep inguinal ring and descends to the lateral caudal zone of the SC, whereas in women, it follows the round ligament. The external cremasteric vein (blue line sign) is an anatomical landmark that helps identify the genital branch as they run alongside each other [16, 20, 21, 23, 24].

Several anatomical variations should be highlighted, including the early superficialization of the II nerve in the EOM aponeurosis between the deep and superficial rings, fusion of the II and IHG nerves or absence of one of these nerves, the aberrant II branch descending alongside the genital branch of the GNF, and the II nerve within the cremaster muscle, which is identifiable in up to 35% of patients [20, 23, 24].

Chronic pain prevention

Recommendation 2

Comprehensive and meticulous dissection, proper identification, and dissection of nerves, and covering fascia protection.

The surgical procedure begins with meticulous dissection of the inguinal region because complications such as hematoma, seroma, and infection are risk factors for chronic pain. Comprehensive dissection of the inguinal region is crucial. Minimal dissection, which may reduce the duration of the surgical procedure but compromise nerve identification, should be avoided [16, 20]. The subcutaneous cellular tissue is carefully dissected to avoid injuring the II and IHG nerve branches, which may be prematurely found in this topography. Careful opening of the EOM aponeurosis prevents inadvertent injury to the II nerve. The II and IHG nerves should be kept in their usual beds without manipulation to avoid damaging the neurolemma. The protective fascia (connective areolar tissue present in the IOM) covering these nerves should be kept intact (Fig. 3). This is achieved by dissecting the fascia from the upper and lower edges of the EOM aponeurosis as close to the aponeurosis as possible. This connective tissue prevents direct contact between the mesh and the nerve [16, 20, 23, 24].

Preserving the deep cremasteric fascia during SC dissection is vital because it shields the genital branch of the GNF nerve from perineural scarring and direct contact with the mesh. In females, avoiding cutting the round ligament of the uterus is essential to reduce the risk of injury to the genital branch of the GNF nerve [23, 24]. Ensuring that the deep inguinal ring is not excessively narrow is crucial to avoid direct contact between the II nerve and the mesh. Fixing the mesh to the IOM aponeurosis prevents the involvement or entrapment of the muscular segment—the most vulnerable part—of the IHG nerve. Fixing the mesh to the periosteum of the pubic bone should be avoided because it can cause chronic pain. The suture should be placed at the inguinal ligament at the level of the deep inguinal ring to prevent femoral nerve entrapment [1, 6, 7, 12, 13, 20].

Pragmatic neurectomy

Recommendation 3

Pragmatic neurectomy should be performed in cases of nerve injury, risk of entrapment, or nerve interference at the time of mesh fixation.

Pragmatic neurectomy has been adopted with the aim of minimizing the risks of nerve injury [1, 6, 12, 23, 24]. (Fig. 4) The II and IHG nerves are the most commonly used in neurectomy. Nerve injuries can be complete or partial (axonotmesis, neurotmesis, or neuropraxia). Axonotmesis, neurotmesis, and complete nerve injury can cause neuromas and increase the risk of chronic pain. A pragmatic neurectomy should be performed to prevent neuromas [22,23,24]. The injured nerves must be resected along their entire length, as distally and proximally as possible, and ligated with absorbable sutures to prevent exposure of the myelin sheath (Fig. 5). The proximal nerve stump (II or IHG) is implanted within the IOM fibers, thus preventing adhesion of the nerve stump to the inguinal ligament or IOM aponeurosis. Adhesion of the neural stump to these structures can result in nerve traction when walking or moving the hip, potentially triggering postoperative neuralgia. The proximal stump of the genital branch of the GNF nerve is ligated with slight traction to remove the stump from the deep inguinal ring [24].

Right inguinal region post-EOM aponeurosis opening The IHG nerve after dissection in its extension with proximal stump ligation using absorbable sutures (pragmatic neurectomy). (source: author). The yellow arrow shows the dissected IHG nerve, and the blue arrow shows nerve stump ligation with absorbable sutures

Prophylactic neurectomy of the II or IHG nerve is not recommended because it does not reduce the incidence of chronic pain but may increase the risk of sensory loss. However, if necessary, a prudent surgeon should discuss the risks and benefits of neurectomy with the patient [24,25,26,27,28].

Spermatic cord structure management

Recommendation 4

Protecting the cremasteric fascia and visualizing the external spermatic vein (blue line).

The SC must be isolated from the inguinal floor without injury using Mixter or Kelly forceps. Digital dissection by elevating and circling the SC with a finger should be avoided because of its traumatic nature, which increases the risk of cremasteric fascial injuries. The SC should be mobilized en bloc with all its structures and released from the inguinal floor approximately 2 cm beyond the pubic tubercle. It should be mobilized with a Penrose drain, as materials such as gauze or pads increase local trauma and the risk of injury to the genital branch of the GNF nerve. The cremaster muscle fibers are transversely incised at the level of the deep inguinal ring to identify an indirect hernia or cord lipoma. If a lipoma is detected, it must be resected. The cremaster muscle should not be resected and exposed, as in the original technique, because it can injure small blood vessels and paravasal nerves, leading to torsion of the vas deferens and increasing the risk of ischemic orchitis, chronic pain, and burning sensation after ejaculation [1, 6, 8, 16, 20, 23]. When associated with pragmatic neurectomy, cremaster resection can be considered in cases of inguinal scrotal hernia with SC enlargement, cremaster hypertrophy, or a dilated inguinal ring. This surgical tactic aims to reconstruct the internal inguinal ring to avoid chronic pain; however, insufficient evidence exists according to the consensus on the management of inguinal-scrotal hernias [29].

Femoral canal assessment

Recommendation 5

Femoral canal assessment is mandatory to prevent missed femoral hernias.

The canal is assessed through the space of Bogros or the hernial sac. In indirect hernias, the hernial sac is opened, and the femoral region is analyzed from within the hernial sac (Fig. 6). In direct hernias, a small opening is made in the transversalis fascia to expose the femoral canal [6, 8, 16].

If a femoral hernia is identified during these maneuvers, it must be corrected simultaneously by changing the mesh shape. The mesh must exhibit a triangular extension at its lower edge (Fig. 7). After opening the posterior wall and reducing the hernia content, this extension is sutured to Cooper’s ligament, and the body of the mesh is sutured to the inguinal ligament (dotted line) [6, 8, 16, 18].

Hernial sac management

Recommendation 6

Management of the hernial sac depends on the type of hernia: indirect, direct, or inguinal-scrotal.

In indirect hernias, the hernial sac is released from the SC beyond the neck and inverted or reduced into the abdominal cavity without ligation. This approach minimizes the risk of chronic pain without increasing recurrence or complication rates (Fig. 8). Ligation should be avoided, as it increases the likelihood of postoperative pain [3, 5,6,7,8,9, 29,30,31,32].

The transversalis fascia can be sutured in direct hernias using continuous or purse-string stitches with absorbable threads. This suture restores the anatomy and facilitates mesh placement [3, 5].

Inguinal-scrotal hernias are approached slightly differently. Ideally, the hernial sac should be reduced en bloc. When this is not feasible, the hernia should be transected at the midpoint of the inguinal canal, leaving the distal part of the sac open and opening the anterior wall to reduce the risk of hydrocele [29].

Mesh

Recommendation 8

Choosing the mesh with appropriate characteristics and format.

The standard mesh used in Lichtenstein surgery resembles a footprint. The medial end of the mesh has a sharp curve (on the great toe side of the foot), which fits the angle between the inguinal ligament and anterior rectus sheath, and a wider curve that spreads over the rectus sheath (Fig. 9). This mesh format has remained the same since its introduction in 1993 and is used in more than 95% of cases, regardless of the hernia size [1, 12, 13, 16].

One side has a sharp curve to fit between the inguinal ligament and the rectus sheath (yellow arrow), whereas the other has a wider curve to fit over the rectus abdominis sheath (red arrow). The blue dotted line shows where to cut the two edges of the mesh (top 2/3 and bottom 1/3).

The use of a mesh in IH surgery is well-established and reduces the risk of recurrence. Nevertheless, the impact of prostheses on the etiology of pain and foreign body sensations cannot be ignored. Commercially available meshes are composed of different materials and exhibit several characteristics (e.g., pore size, weight, pore effectiveness, strength, and elasticity). In IH repair, weight and porosity are crucial. The mesh weight is directly contingent on the weight of the polymer, which is measured in grams/m2 (grammage). These meshes are categorized as ultralow, low, medium, and heavy grammages [33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Light or low-grammage meshes weighing < 40 g/g/m2 tend to induce less inflammation and foreign body sensation. Porosity influences the biological behavior of the mesh, affecting the formation of fibrotic scar tissue and resistance to infection. Large-pore meshes are characterized by pores ranging from 1 to 1.5 mm [1, 12, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39].

The optimal recommendation for IH repair using the Lichtenstein technique is to employ monofilament synthetic meshes characterized by low weight, large pores, and a tensile strength exceeding 16 N/m2. Such meshes reduce the incidence of chronic pain and foreign-body sensation without increasing recurrence. Nevertheless, studies with extended follow-up periods have shown that the incidence of chronic pain appears to be equivalent between low- and heavy-weight meshes in later stages [1, 12].

The autoimmune syndrome induced by adjuvants is worth taking note of. This is a relatively unknown complication associated with the use of polypropylene mesh, particularly in women. Its diagnosis is complicated because it presents with non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia, and neurological disorders triggered by prosthesis use. The recommended treatment involves the removal of the prosthetic material [40].

Fixation

Recommendation 8

Correct fixation prevents chronic pain, mesh mobilization, or bending and reduces the risk of recurrence.

Proper fixation of the mesh is crucial for the Lichtenstein technique. The medial portion of the mesh should be secured with two interrupted absorbable stitches: one in the rectus abdominis sheath and the other in the IOM aponeurosis at the level of the deep inguinal ring. The IHG muscular segments must not be included. These stitches should be loosely tied to avoid tissue necrosis and chronic pain (Fig. 10) [41]. The mesh must be affixed to the inguinal ligament with a continuous nonabsorbable monofilament suture, passing the needle three to four times (Fig. 11). Beginning at the reflex inguinal ligament and avoiding the periosteum of the pubic bone, the suture ends at the level of the deep inguinal ring. The lower mesh edges should overlap (i.e., the upper end must cover the bottom), be fixed with nonabsorbable sutures to the inguinal ligament, and be juxtaposed to the last knot of the continuous suture (Fig. 11) [1, 4, 6,7,8, 13, 14, 16, 41].

Left inguinal region. Mesh fixation to the inguinal ligament with monofilament nonabsorbable suture. (source: author). Yellow arrow: last stitch of the continuous suture at the level of the deep inguinal ring; green arrow: fixation of the lower edges of the mesh to the inguinal ligament juxtaposed to the last stitch of the continuous suture

Anterior mesh repairs exhibit no significant differences regarding infection or recurrence between the fixation methods (traumatic or atraumatic). Atraumatic fixation, such as that using glue, sealants, cyanoacrylate, or self-fixing meshes appears to reduce postoperative pain only in the initial stages. Self-fixing meshes demonstrated only to lower operative time without clinical advantages over sutured mesh fixation [1, 20, 42]. Therefore, atraumatic fixation warrants only a weak recommendation according to the international consensus on hernia management [1].

Recurrence prevention

Recommendation 9

Proper fixation, appropriate mesh size, overlapping, wide dissection, and anatomical knowledge are essential to reduce the risk of recurrence.

The primary recurrence sites are the pubic region (owing to the lack of adequate mesh overlap on the pubic tubercle) and the region close to the deep inguinal ring (owing to the lack of crossing of the mesh edges behind the SC) for direct and indirect hernias, respectively [4,5,6,7,8, 12,13,14, 16].

The mesh dimensions (7.5 × 15 cm) should adequately cover vulnerable areas. A 1 cm incision may be necessary to properly fit the mesh in the inguinal region in some patients. To comprehensively cover this area, the mesh overlaps should extend 2 cm beyond the pubic symphysis, 5–6 cm lateral to the internal inguinal ring, and 3–4 cm beyond the inguinal triangle [3, 4, 6, 8, 13, 14, 43]. The mesh should be slightly relaxed or dome-shaped to accommodate the transversalis fascia protrusion when the patients exert themselves, thus compensating for mesh countertraction (Fig. 10). Crossing the mesh edges behind the SC is crucial to prevent recurrence lateral to the internal inguinal ring. The mesh must be cut into the distal region to create two edges. The upper and lower edges should be 2/3 and 1/3 of the mesh width, respectively. The upper edge must cover the lower edge [4,5,6,7,8, 12, 16, 42, 43]. Furthermore, the lower edges must be sutured to the inguinal ligament using a nonabsorbable monofilament thread and juxtaposed to the last knot of the continuous suture (Fig. 11). This fixation technique cannot be altered in patients undergoing surgery using a flat mesh. However, this type of fixation can be skipped when pre-loosened meshes are used. In such cases, the two edges can be sutured together with 0.5–1 cm of crossing, thus simplifying the procedure [6].

Surgical convalescence

Recommendation 10

Convalescence duration.

Patients should resume their activities without restriction as soon as they feel able or feel no pain during usual activities, typically three to five days after surgery [1, 8, 12]. In initial studies by Lichtenstein et al. (1989), patients were encouraged to cough intraoperatively and perform the Valsalva maneuver to assess the strength of the repair without compromising surgical outcomes related to recurrence [5, 8, 9]. Early return to activities does not adversely affect recurrence rates. Conversely, sedentary patients have a recurrence rate that is twice that of active patients [41].

Discussion

Recent extensive academic debates have discussed the superiority of IH repair techniques (open vs. laparoscopic) [16]. The literature indicates highly comparable recurrence, chronic pain, and complication rates [16, 20, 44,45,46,47,48]. Therefore, defining a technique as the gold standard is challenging [20]. Comparing personal and institutional results of the Lichtenstein technique remains challenging owing to individual variations within the surgical method [5]. A recent study published in Brazil shows interesting results regarding individual differences in this technique and highlights the need for increased knowledge regarding many technical steps used in Lichtenstein surgery [15]. Therefore, systematizing the surgical approach may facilitate result evaluation and comparison with other techniques.

Studies of chronic pain have proliferated with advances in neuroanatomical insights into the inguinal region. Chronic pain can affect up to 69% of patients undergoing IH surgery [20, 21]. Recent findings indicate that 12–16% of patients have moderate to severe pain six months post-surgery [1, 12, 22]. Given that approximately 20 million patients undergo IH surgery annually globally, the prevalence of chronic pain is assumed to be significant. Thus, the outcomes of patients with chronic pain should be improved [1, 12].

Identifying inguinal nerves is a logical, pivotal step to mitigate chronic inguinal pain post-herniorrhaphy since this technical step may reduce the incidence of chronic pain to less than 1% [21]. This approach serves a dual purpose: it protects the nerves and allows for a neurectomy in case of nerve interference with mesh placement [23]. Despite a lack of comprehensive anatomical and surgical understanding of the inguinal region, proficiency in inguinal neuroanatomy and inguinal canal topography is essential for all IH surgeons [2]. Chronic pain prevention measures must be incorporated into the surgical procedure, including wide dissection, preservation of the neural covering fascia, atraumatic manipulation, nerve identification, and pragmatic neurectomy [6, 7, 13].

Acquiring knowledge of the technical principles of the Amid-modified Lichtenstein technique and surgical strategies to prevent chronic pain can improve surgical outcomes, significantly impacting public health and patients’ quality of life [16].

The ten recommendations: neuroanatomical assessment, chronic pain prevention, pragmatic neurectomy, protecting the cremasteric fascia and visualizing the external spermatic vein (blue line), femoral canal assessment, hernial sac management, choosing the mesh with appropriate characteristics and format, proper fixation, recurrence prevention and convalescence duration are practical ways to achieve a safe and successful procedure. We fell that following these recommendations can improve surgical outcomes using the Lichtenstein technique.

Conclusion

Comprehensive knowledge of the technical steps of Lichtenstein technique is essential for IH surgery. Given the evolution and modifications of the technique since its initial description, this study lists ten recommendations as a practical guide for surgeons to enhance the outcomes of patients undergoing inguinal hernioplasty using the Lichtenstein technique.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

HerniaSurge Group (2018) International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia 22:1–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x. Epub 2018 Jan 12. PMID: 29330835; PMCID: PMC5809582

Hori T, Yasukawa D (2021) Fascinating history of groin hernias: Comprehensive recognition of anatomy, classic considerations for herniorrhaphy, and current controversies in hernioplasty. World J Methodol 11:160–186. https://doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v11.i4.160. PMID: 34322367; PMCID: PMC8299909

Lau WY (2002) History of treatment of groin hernia. World J Surg 26:748–759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-002-6297-5. Epub 2002 Mar 26. PMID: 12053232

Amid PK (2005) Groin hernia repair: open techniques. World J Surg 29:1046–1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-7967-x. PMID: 15983714

Lichtenstein IL, Shulman AG, Amid PK, Montllor MM (1989) The tension-free hernioplasty. Am J Surg 157:188–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9610(89)90526-6. PMID: 2916733

Amid PK (2004) Lichtenstein tension-free hernioplasty: its inception, evolution, and principles. Hernia 8:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-003-0160-y

Kurzer M, Belsham PA, Kark AE (2003) The Lichtenstein repair for groin hernias. Surg Clin North Am 83:1099–1117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00134-8. PMID: 14533906

Amid PK, Shulman AG, Lichtenstein IL (1993) Critical scrutiny of the open tension-free hernioplasty. Am J Surg 165:369–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80847-5. PMID: 8447547

Lichtenstein IL (1987) Herniorrhaphy. A personal experience with 6,321 cases. Am J Surg 153:553–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9610(87)90153-x

van Veenendaal N, Simons M, Hope W, Tumtavitikul S, Bonjer J, HerniaSurge Group (2020) Consensus on international guidelines for management of groin hernias. Surg Endosc 34:2359–2377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07516-5. Epub 2020 Apr 6. PMID: 32253559

Miserez M, Peeters E, Aufenacker T et al (2014) Update with level 1 studies of the European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia 18:151–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-014-1236-6. Erratum in: Hernia 2014;18:443–444

Claus CMP, Oliveira FMM, Furtado ML, Azevedo MA, Roll S, Soares G, Nacul MP, Rosa ALMD, Melo RM, Beitler JC, Cavalieri MB, Morrell AC, Cavazzola LT (2019) Guidelines of the Brazilian Hernia Society (BHS) for the management of inguinocrural hernias in adults. Rev Col Bras Cir 46:e20192226. Portuguese, English. https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-6991e-20192226. PMID: 31576988

Amid PK (2003) The Lichtenstein repair in 2002: an overview of causes of recurrence after Lichtenstein tension-free hernioplasty. Hernia 7:13–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-002-0088-7. Epub 2002 Oct 5. PMID: 12612791

Amid PK (2002) How to avoid recurrence in Lichtenstein tension-free hernioplasty. Am J Surg 184:259–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00936-4. PMID: 12354596

Messias BA, de Almeida PL, Ichinose TMS, Mocchetti ER, Barbosa CA, Waisberg J, Roll S, Ribeiro MF, Junior (2023) The Lichtenstein technique is being used adequately in inguinal hernia repair: national analysis and review of the surgical technique. Rev Col Bras Cir 50:e20233655. https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-6991e-20233655-en

Chen DC, Morrison J (2019) State of the art: open mesh-based inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 23:485–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-019-01983-z

Guillaumes S, Hoyuela C, Hidalgo NJ, Juvany M, Bachero I, Ardid J, Martrat A, Trias M (2021) Inguinal hernia repair in Spain. A population-based study of 263,283 patients: factors associated with the choice of laparoscopic approach. Hernia 25:1345–1354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-021-02402-y

AlMarzooqi R, Tish S, Huang LC, Prabhu A, Rosen M (2019) Review of inguinal hernia repair techniques within the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative. Hernia 23:429–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-019-01968-y

Öberg S, Jessen ML, Andresen K, Rothman JV, Rosenberg J (2020) High complication rates during and after repeated Lichtenstein or laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs in the same groin: a cohort study based on medical records. Hernia 24:801–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-019-02083-8. Epub 2019 Dec 9. PMID: 31820186

Alfieri S, Amid PK, Campanelli G, Izard G, Kehlet H, Wijsmuller AR, Di Miceli D, Doglietto GB (2011) International guidelines for prevention and management of post-operative chronic pain following inguinal hernia surgery. Hernia 15:239–249

Konschake M, Zwierzina M, Moriggl B, Függer R, Mayer F, Brunner W, Schmid T, Chen DC, Fortelny R (2020) The inguinal region revisited: the surgical point of view: an anatomical-surgical mapping and sonographic approach regarding postoperative chronic groin pain following open hernia repair. Hernia 24:883–894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-019-02070-z. Epub 2019 Nov 27. PMID: 31776877; PMCID: PMC7395915

Andresen K, Rosenberg J (2018) Management of chronic pain after hernia repair. J Pain Res 11:675–681. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S127820. PMID: 29670394; PMCID: PMC5896652

Lange JFM, Wijsmuller AR, van Geldere D, Simons MP, Swart R, Oomen J, Kleinrensink GJ, Jeekel J, Lange JF (2009) Feasibility study of three-nerve-recognizing Lichtenstein procedure for inguinal hernia. Br J Surg 96:1210–1214. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.6698

Amid PK (2004) Causes, prevention, and surgical treatment of postherniorrhaphy neuropathic inguinodynia: triple neurectomy with proximal end implantation. Hernia 8:343–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-004-0247-0

Charalambous MP, Charalambous CP (2018) Incidence of chronic groin pain following open mesh inguinal hernia repair, and effect of elective division of the ilioinguinal nerve: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hernia 22:401–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1753-9

Cirocchi R, Sutera M, Fedeli P, Anania G, Covarelli P, Suadoni F, Boselli C, Carlini L, Trastulli S, D’Andrea V, Bruzzone P (2021) Ilioinguinal nerve neurectomy is better than preservation in Lichtenstein Hernia Repair: a systematic literature review and Meta-analysis. World J Surg 45:1750–1760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-021-05968-x. Epub 2021 Feb 19. PMID: 33606079; PMCID: PMC8093155

Hsu W, Chen CS, Lee HC, Liang HH, Kuo LJ, Wei PL, Tam KW (2012) Preservation versus division of ilioinguinal nerve on open mesh repair of inguinal hernia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Surg 36:2311–2319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-012-1657-2

Picchio M, Palimento D, Attanasio U, Matarazzo PF, Bambini C, Caliendo A (2004) Randomized controlled trial of preservation or elective division of ilioinguinal nerve on open inguinal hernia repair with polypropylene mesh. Arch Surg 139:755–759. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.139.7.755

Tran HM, MacQueen I, Chen D, Simons M (2023) Systematic review and guidelines for management of Scrotal Inguinal Hernias. J Abdom Wall Surg 2:11195. https://doi.org/10.3389/jaws.2023.11195

Sharma M, Pathania OP, Kapur A, Thomas S, Kumar A (2019) A randomised controlled trial of excision versus invagination in the management of indirect inguinal hernial sac. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 101:119–122. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsann.2018.0160

Othman I, Hady HA (2014) Hernia sac of indirect inguinal hernia: invagination, excision, or ligation? Hernia 18:199–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-013-1081-z

Kao CY, Li CL, Lin CC, Su CM, Chen CC, Tam KW (2015) Sac ligation in inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg 19:55–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.02.043

Bakker WJ, Aufenacker TJ, Boschman JS, Burgmans JPJ (2020) Lightweight mesh is recommended in open inguinal (Lichtenstein) hernia repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery 167:581–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2019.08.021

Uzzaman MM, Ratnasingham K, Ashraf N (2012) Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing lightweight and heavyweight mesh for Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 16:505–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-012-0901-x

Zhong C, Wu B, Yang Z, Deng X, Kang J, Guo B, Fan Y (2013) A meta-analysis comparing lightweight meshes with heavyweight meshes in Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair. Surg Innov 20:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1553350612463444

Rutegård M, Lindqvist M, Svensson J, Nordin P, Haapamäki MM (2021) Chronic pain after open inguinal hernia repair: expertise-based randomized clinical trial of heavyweight or lightweight mesh. Br J Surg 108:138–144. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znaa049

Demetrashvili Z, Khutsishvili K, Pipia I, Kenchadze G, Ekaladze E (2014) Standard polypropylene mesh vs lightweight mesh for Lichtenstein repair of primary inguinal hernia: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Surg 12:1380–1384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.10.025

Nikkolo C, Murruste M, Vaasna T, Seepter H, Tikk T, Lepner U (2012) Three-year results of randomised clinical trial comparing lightweight mesh with heavyweight mesh for inguinal hernioplasty. Hernia 16:555–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-012-0951-0

Kenary AY, Afshin SN, Ahmadi Amoli H, Notash AY, Borjian A, Notash AY Jr, Shafaattalab S, Shafiee G (2013) Randomized clinical trial comparing lightweight mesh with heavyweight mesh for primary inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 17:471–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-012-1009-z

Dias ERM, Pivetta LGA, de Carvalho JPV, Furtado ML, de Freitas Amaral PH, Roll S (2021) Autoimmune [auto-inflammatory] syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA): Case report after inguinal hernia repair with mesh. Int J Surg Case Rep 84:106060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.106060Epub 2021 Jun 11. PMID: 34216916; PMCID: PMC8258851

Gopal SV, Warrier A (2013) Recurrence after groin hernia repair-revisited. Int J Surg 11:374–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.03.012

Singh A, Subramanian A, Toh WH, Bhaskaran P, Fatima A, Sajid MS (2023) Comprehensive systematic review on the self-gripping mesh vs sutured mesh in inguinal hernia repair. Surg Open Sci 17:58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sopen.2023.12.010PMID: 38293004; PMCID: PMC10826810

Seker D, Oztuna D, Kulacoglu H, Genc Y, Akcil M (2013) Mesh size in Lichtenstein repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the importance of mesh size. Hernia 17:167–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-012-1018-y

Bullen NL, Massey LH, Antoniou SA, Smart NJ, Fortelny RH (2019) Open versus laparoscopic mesh repair of primary unilateral uncomplicated inguinal hernia: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Hernia 23:461–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-019-01989-7. Epub 2019 Jun 3. PMID: 31161285

Koning GG, Wetterslev J, van Laarhoven CJ, Keus F (2013) The totally extraperitoneal method versus Lichtenstein’s technique for inguinal hernia repair: a systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of randomized clinical trials. PLoS One 8:e52599. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052599. Epub 2013 Jan 11. Erratum in: PLoS One. 2013;8(1). 0.1371/annotation/4775d24d-130e-40f8-a19e-fc4ad5adb738. PMID: 23349689; PMCID: PMC3543416

Scheuermann U, Niebisch S, Lyros O, Jansen-Winkeln B, Gockel I (2017) Transabdominal Preperitoneal (TAPP) versus Lichtenstein operation for primary inguinal hernia repair - A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Surg 17:55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-017-0253-7

Kargar S, Shiryazdi SM, Zare M, Mirshamsi MH, Ahmadi S, Neamatzadeh H (2015) Comparison of postoperative short-term complications after laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) versus Lichtenstein tension free inguinal hernia repair: a randomized trial study. Minerva Chir 70:83–89

Köckerling F, Koch A, Adolf D, Keller T, Lorenz R, Fortelny RH, Schug-Pass C (2018) Has Shouldice Repair in a selected group of patients with inguinal hernia comparable results to Lichtenstein, TEP and TAPP techniques? World J Surg 42:2001–2010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4433-5

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage for the English language editing.

Funding

This work was carried out with the support of Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel – Brazil (CAPES) – Financing Code 001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Bruno Amantini Messias, Erica Rossi Mocchetti, and Marcelo Augusto Fontenelle Ribeiro Junior. Methodology: Bruno Amantini and Jaques Waisberg. Formal analysis and investigation: Bruno Amantini Messias. Writing original draft: Bruno Amantini Messias. Review and editing: Bruno Amantini Messias, Rafael Goncalves Nicastro, Sergio Roll, and Marcelo Augusto Fontenelle Ribeiro Junior. Funding acquisition: Bruno Amantini Messias and Jaques Waisberg. Supervision: Sergio Roll, Jaques Waisberg, and Marcelo Augusto Fontenelle Ribeiro Junior.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of São Camilo University Center (CAAE no. 59271422.7.0000.0062).

Consent to participate

The present study is a review in which no research involving humans was undertaken and the need for informed consent was waived.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Messias, B.A., Nicastro, R.G., Mocchetti, E.R. et al. Lichtenstein technique for inguinal hernia repair: ten recommendations to optimize surgical outcomes. Hernia (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-024-03094-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-024-03094-w