Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of these recommendations is to spread the available evidence for evaluating and managing spinal tumours among clinicians who encounter such entities.

Methods

The recommendations were developed by members of the Development Recommendations Group representing seven stakeholder scientific societies and organizations of specialists involved in various forms of care for patients with spinal tumours in Poland. The recommendations are based on data yielded from systematic reviews of the literature identified through electronic database searches. The strength of the recommendations was graded according to the North American Spine Society’s grades of recommendation for summaries or reviews of studies.

Results

The recommendation group developed 89 level A-C recommendations and a supplementary list of institutions able to manage primary malignant spinal tumours, namely, spinal sarcomas, at the expert level. This list, further called an appendix, helps clinicians who encounter spinal tumours refer patients with suspected spinal sarcoma or chordoma for pathological diagnosis, surgery and radiosurgery. The list constitutes a basis of the network of expertise for the management of primary malignant spinal tumours and should be understood as a communication network of specialists involved in the care of primary spinal malignancies.

Conclusion

The developed recommendations together with the national network of expertise should optimize the management of patients with spinal tumours, especially rare malignancies, and optimize their referral and allocation within the Polish national health service system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Initially, the only purpose of our project was to develop recommendations for the evaluation and management of spinal tumours among clinicians caring for such entities. To the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive recommendations regarding the full spectrum of spinal tumours have been published thus far. Soon after starting the project, we added another goal: the development of a network of expertise at a national level for the management of primary malignant spinal tumours in Poland with a plan to incorporate this network into the existing organizational structure of the Polish national cancer care system. Such a network will follow recommendations of the European Union Joint Action on Cancer and the European Partnership for Action Against Cancer (EPAAC) [1].

The EPAAC recommends the establishment of networks of expertise in the management of soft tissue and bone sarcomas in regions where it is not possible to establish comprehensive centres for their management. In Poland, similar to the majority of other countries, such centres offering comprehensive expertise under the one roof do not exist or are very rare. Our expertise network seems to be a reasonable alternative given the lack of such centres and a good response to the EPAAC recommendations.

We believe that with the national expertise network, our recommendations have an increased chance to be fully met in everyday clinical practice.

Incorporation of our expertise network into the existing national system of cancer care in Poland should be straightforward. This is because in Poland, interdisciplinarity in the management of cancer is a fundamental principle and a statutory requirement of a Polish national cancer care system. This principle is executed with relative ease for most oncology patients in Poland, but clinicians and patients can experience problems in regard to very rare malignancies, such as spinal sarcomas and chordomas. Access to the expertise network for both patients and clinicians encountering spinal tumours should complement the Polish cancer care system in the management of rare primary spinal malignancies. Currently, specialists with expertise in these tumours are dispersed across the country and, consequently, problems with coordinated referral and interdisciplinary management of these patients exist. In practice, interdisciplinary services for the management of rare spinal tumours are not available under the one roof, even at quaternary or university hospitals. Furthermore, the interdisciplinary management of these tumours may not be available, even within a single broader region of the country. Complex oncologic spine surgery can be performed by a specialist in one corner of the country, molecular histology of sarcomas in another corner, and proton beam therapy or radiosurgery in yet another corner. Similar dispersions of expertise and facilities for the management of rare malignancies can be found worldwide, including in highly developed countries. We believe that a dedicated expertise network for rare spinal tumours at the national level will improve the coordinated interdisciplinary management of patients, despite the dispersion of experts and facilities across the country.

Methods

The recommendations development group

The project to develop such recommendations was an initiative of the Executive Committee of the Polish Society of Spine Surgery. The Committee invited some stakeholder organizations to the project to ensure broad representation of all specialties involved in the care of patients with spinal tumours. Ultimately, seven organizations, including the Polish Society of Spine Surgery, agreed to participate in the project: the Polish Society of Oncology, the Polish Society of Neurosurgeons, the Polish Society of Oncologic Surgery, the Polish Society of Oncologic Radiotherapy, the Polish Society of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, and the Department of Soft Tissue/Bone Sarcoma and Melanoma at the Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, Warsaw, Poland. Each one nominated representatives to serve on the Recommendation Development Group. In total, 20 volunteers participated in this effort, including the following specialists: (1) neurosurgeons and orthopaedic surgeons with expertise in the field of spine surgery, (2) radiation oncologists, (3) medical oncologists, and (4) experts in the field of sarcoma from the Department of Soft Tissue, Bone Sarcoma and Melanoma at the Maria Sklodowska-Curie Institute Oncology Center in Poland.

Grading recommendations and level of evidence

The recommendations were based on systematic reviews of the literature identified from searching electronic databases. The strength of the recommendations was graded according to the North American Spine Society’s Grades of Recommendation for Summaries or Reviews of Studies (Tables 1 and 2). A: good evidence (level I studies with consistent findings) for or against recommending intervention; B: fair evidence (level II or III studies with consistent findings) for or against recommending intervention; C: poor quality evidence (level IV or V studies) for or against recommending intervention; and I: insufficient or conflicting evidence not allowing for a recommendation for or against intervention [2, 3].

Each identified source of evidence was rated in terms of the strength of yielded evidence with the use of levels of evidence for primary research questions as adopted by the North American Spine Society in January 2005 and other societies and journals, namely, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America, Clinical, Orthopaedics and Related Research, Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery and Spine (Table 2) [3].

Organization of the literature search

Members of the Recommendation Development Group were divided into several working teams, each performing a database search for one or more topics allocated to them in accordance with the specialties of the team members. There were 11 core topics: epidemiology of spinal tumours, aetiology and classification of spinal tumours, imaging diagnostics of spinal tumours, clinical diagnosis and grading scales, biopsy and management of biopsy samples, histological diagnosis, chemotherapy and radiotherapy of primary tumours in particular, chemotherapy and radiotherapy of metastatic tumours, surgical treatment of primary malignant spinal tumours, surgical treatment of benign spinal tumours, and surgical treatment of metastatic tumours. Most malignant primary tumours, namely, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, chordoma, osteoblastoma, and solitary plasmocytoma, and many benign tumours, aneurysmal cysts and giant cell tumours in particular, were searched for separately and reviewed by working teams according to the specialties of the team members. Each team had the freedom to identify papers relevant to the allocated topic. It was a duty of each team to critically assess the quality of the identified studies and downgrade their levels of evidence if any shortcomings were present in the execution of the reviewed study.

Formulation of recommendations

All members of the Recommendation Development Group participated in the recommendation development process. Each team proposed preliminary recommendations in a structured way that included formulating the recommendation and the following: (1) classifying the strength of the formulated recommendation, (2) classifying the quality of the study that the recommendation was based on, (3) referencing the source of the study, and (4) stating the type of the study, e.g., randomized controlled trial, retrospective study, and expert opinion. The preliminary recommendations were summarized in a table by each working team (Table 3). Tables with preliminary recommendations from all working teams were compiled into one table embedded in a Word file that was available online for all members of the Recommendation Development Group. The teams were asked to review the table and provide written remarks, comments, objections or opinions in the comments panel of the Word file based on their areas of expertise. This process was supervised by four chairs who were members of the development group but were not involved in the literature search and instead chaired all the meetings and voting sessions of the group. Once the preliminary recommendations were reviewed, each single recommendation was separately subjected to voting during a series of meetings of the whole Recommendation Development Group. Every single preliminary recommendation was separately accepted as a final recommendation when at least 75% of members voted positively. Recommendations that did not achieve this result during the first round of voting were returned to the appropriate working team for revision. Based on the revision, the recommendation could be either rejected or reformulated by the working team and subjected to the second review and vote by the whole Development Group during the subsequent meetings. Those preliminary recommendations that were not accepted during a second vote were ultimately rejected or when representing a crucial issue, put on a discrepancy list.

Expertise network for multidisciplinary management of rare primary spinal tumours

Based on internal surveys in the stakeholder societies represented in the development group, we created a list of institutions, hospitals, teams and individual colleagues with expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of rare malignant spinal tumours. Specifically, we inquired about facilities offering in-depth molecular histological diagnostics, stereotactic body radiation therapy of the spine, proton beam therapy, and complex oncologic spine surgery. Each scientific society was asked to provide such a list with regard to its specialties. A survey among the members of the Polish Society of Spine Surgery concerning their experience in complex oncologic spine surgery, namely, en bloc Enneking-appropriate resections, allowed us to create a list of centres and individual colleagues who have expertise in this type of surgery. These experts were also asked about their willingness and readiness to accept patients requiring this type of surgery from other institutions/colleagues on a regular basis.

Results

Eighty-nine recommendations were developed and accepted by the Recommendation Development Group and divided into four sections: (1) diagnostics, (2) primary tumours, (3) metastatic tumours, and (4) discrepancies (Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 respectively). The list of recommendations will be available on the homepages of stakeholder organizations participating in the development of recommendations and accompanied by an appendix including a list of institutions, teams and individual specialists with expertise in the diagnostics and management of rare primary malignant tumours to optimize patient referral and allocation within the cancer care system of Poland (Table 28).

Discussion

As mentioned above, interdisciplinarity in the management of cancer is a fundamental principle and a statutory requirement of the Polish national cancer care system.

While the principle of interdisciplinarity in the management of most spinal tumours is relatively easy to execute, this is not the case for primary malignant spinal tumours requiring sophisticated molecular diagnostics as well as complex oncologic spine surgery.

No single centre in Poland provides complete management of rare primary malignant spinal tumours from in-depth molecular histological diagnosis through complex oncologic spine surgery to spine radiosurgery and chemotherapy in one institution.

Currently, patients with such tumours and some clinicians involved in the care of such patients may not be aware of the centres offering unique molecular diagnosis or top-level oncologic surgical treatment of the spine. With the dispersion of these highly specialized services across Poland, it may take time and effort to find an institution with the required facilities. A patient may undergo surgical treatment in one place and radiotherapy or chemotherapy in another, while having molecular diagnosis done in yet another place. In everyday practice, such patients and clinicians may both feel lost in regard to deciding which referral centre can offer the most appropriate diagnostics and treatment. Based on internal surveys within scientific societies represented in the development group, we prepared a list of institutions and colleagues with expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of rare malignant spinal tumours, namely sarcomas and chordomas. The list will be available as an appendix to the recommendations on the homepages of the stakeholder organizations. The list aims to give clinicians involved in the care of patients with spinal tumours clues on where to refer patients with rare spinal malignancies for optimal management, especially in regard to complex oncologic spine surgery. The colleagues experienced in this type of surgery declared they would be ready to accept such cases on a regular basis. The appendix will also include a list of institutions with expertise in performing molecular pathology of sarcomas and a list of places and colleagues providing radiosurgery. Therefore, we recommend referring patients with primary malignant tumours to these centres or colleagues. This approach should not be a problem, as in Poland, allocation and free referrals to any institution within the Polish national health service system are protected by the patients’ right to freely choose primary care doctors, specialists, hospitals, and medical institutions anywhere in the country. Free referrals within the system are by no means restricted, and patients, regardless of their place of residence in Poland, who are entitled to free services of the national health system (NHS) have the freedom to choose the place and physician for treatment. Additionally, we believe that the allocation of patients with spinal sarcomas and chordomas to the recommended centres will not burden colleagues with expertise in oncologic spine surgery, and it is unlikely that these surgeons will be swamped by these additional cases, as these tumours are extremely rare. With the incidence of spinal sarcomas being 0,19–0,38 per 1,000,000 people, only approximately 7–15 new cases can be expected in Poland per year. The slightly higher incidence of spinal chordoma, 1 per 1,000,000 population, means approximately 38 new cases can be expected in Poland [22,23,24].

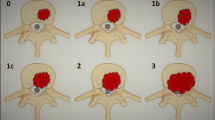

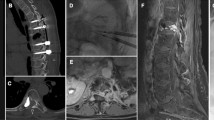

The list is not intended to mandate referrals to the recommended places and specialists, especially in regard to surgical management. Additionally, these specialists will not be obliged to accept such referrals. The estimated number of yearly referrals for spinal sarcomas and chordomas should not exceed 50. Thus, even if only a dozen colleagues have expertise in oncologic spine surgery, each one would potentially accept no more than 3–5 cases if the allocation is evenly distributed across the country. These colleagues declared that they are happy to accept such referrals. Conversely, colleagues who did not declare expertise in complex oncologic spine surgery but will eventually gain such skills with increasing experience should not feel an obligation to refer spinal sarcoma/chordoma patients to colleagues renowned for their expertise in oncologic spine surgery. We understand that complex oncologic spine surgery follows the principles of the Weinstein–Boriani–Biagini (WBB) surgical system used for planning en bloc resections of spinal tumours [25,26,27]. The WBB systems were developed based on the Enneking principles of four types of surgical margins for musculoskeletal sarcoma [28]. Some may confuse true extralesional en bloc resection according to the WBB/Enneking principles with Tomita’s en bloc spondylectomy, which is excision of the whole vertebra in two pieces from the spine, with the cut line dividing the vertebra into two pieces running through the pedicles [29]. An increasing number of colleagues performing spine surgery are skilled in these techniques and apply them for nonneoplastic pathologies of the spine, such as spinal deformities or infections [30, 31]. These skills do not necessarily translate into expertise in truly extralesional resections because the latter may require different combinations of surgical strategies, including combinations of two, three or even more separate routes of surgical access. Only a few colleagues among spine surgeons have expertise in this type of spine surgery due to the extreme rarity of primary malignant spinal tumours. The chance that an average spine surgeon will encounter a patient with spinal sarcoma or chordoma during his or her career is minimal. The majority of excellent spine surgeons will never operate on such spinal tumours, except of a few colleagues specializing in complex oncological spine surgery. Our recommendation for Enneking’s wide and marginal excision of spinal sarcomas and chordomas implies that surgical treatment should ideally be performed by surgeons with expertise in oncological spine surgery. This in turn imposes that a biopsy be performed by the surgeon operating on the tumour because the biopsy must be performed with the surgery plan in mind, as the biopsy tract will have to be removed en bloc with the tumour. Similarly, we recommend that the histopathological diagnostics of spine lesions suspected to be a primary malignancy be performed in recommended centres with expertise in malignant bone tumours. The list of such centres where a sample can be sent for evaluation as well as instructions on how to maintain and fix the biopsied sample will be included in the appendix to our recommendations.

Malignant spinal tumours, in particular sarcomas, provide a particular diagnostic dilemma due to their variety, with more than 100 histological subtypes that often correspond to different biological behaviours and eventually respond differently to chemotherapeutic agents as well as targeted therapy and immunotherapy [32]. This heterogeneity in classification is accompanied by a broad spectrum of biological behaviour, from locally aggressive and nonmetastatic tumours to tumours that behave relatively indolently in the metastatic state to those that are highly aggressive and rapidly metastasise. Histological evaluations of sarcomas require advanced molecular diagnostics [32, 33].

Advanced molecular diagnostics of rare musculoskeletal tumours, especially sarcomas, are available in very few places dispersed across Poland. This is also the case in other European countries, as documented by the EPAAC through an assessment of the quality of cancer care in Europe [1]. That is why in many countries, there is a trend to concentrate expertise for certain tumour types, including sarcomas, in dedicated centres or units [1].

In Poland, there is a Department of Soft Tissue, Bone Sarcoma and Melanoma at the Maria Sklodowska-Curie Institute Oncology Centre in Warsaw dedicated to the complex management of sarcomas. This department covers the majority of sarcoma cases in regard to molecular diagnostics and surgical treatment in Poland. However, the department mostly encounters only appendicular sarcomas, while spinal sarcomas are randomly operated on elsewhere across the country, often without a preceding biopsy or even radiological diagnosis or radiological suspicion of sarcoma. Therefore, most if not all spinal sarcomas are not operated on compliantly with the WBB/Enneking principles of extralesional excision. Once the preliminary histology of the operated spinal tumour confirms or suggests sarcoma, the sample may be sent for further in-depth diagnosis to another institution with better facilities and expertise in molecular pathology. Sometimes the sample may circulate from institution to institution before it reaches one that eventually establishes a thorough molecular diagnosis. To ensure a timely histological diagnosis and prevent patients from receiving an incomplete diagnosis of sarcoma, we identified all institutions and colleagues in Poland with expertise in molecular pathology techniques for sarcomas. These institutions will be listed in the appendix to the recommendations. Although few exist in the country, these institutions are able to cover the histological diagnostics of all spinal and appendicular sarcomas occurring in Poland. The EPAAC expert group recommends that for an institution to be considered a sarcoma centre, it should treat at least 100 new sarcoma patients (both soft tissue and bone) per year [1]. Similarly, guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in England and Wales states that multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) managing either soft tissue sarcoma or bone sarcoma should manage the care of at least 100 new patients per year (100 soft tissue and 50 bone sarcomas if the MDT manages both types) [34].

Therefore, we recommend sending biopsied and intraoperative samples suspected of being spinal sarcoma to the institutions listed in the appendix. This is in accordance with the recommendation of the European Cancer Organization (ECCO) expert group, who stresses that a diagnosis must only be made in dedicated sarcoma centres [1]. In addition, we added instructions to the appendix on how samples from tumours suspected to be a sarcoma should be fixed immediately after harvesting in the operating room.

Only two recommendations were placed on the discrepancy list (Table 28). These recommendations refer to emergency/urgent decompression of the spinal canal to counteract irreversible neurologic deficits in cases where no histological diagnosis was obtained. As everyday practice proves, emergency decompression surgeries are not uncommon in spinal tumours. Urgent or emergency decompression does not conflict with the principles of treatment of spinal tumours as long as the tumour is a metastasis. However, such decompression may conflict with the treatment principles when a tumour appears to be a primary tumour, especially haematopoietic tumours. Surgical treatment of haematopoietic tumours has no proven benefit compared with medical treatment, which usually provides excellent long-term outcomes. The view of some medical colleagues in the group clashed with the views of surgical colleagues. The first view stressed that surgery on haematopoietic malignancies of the spine can reduce or even deprive patients of a chance for a complete cure, even if adequate medical treatment is continued after the operation. The second view noted the impact of permanent complete or severe neurological deficits on quality of life, even if the patient receives state-of-the-art medical treatment. Whether patients with spinal tumours and a risk of permanent neurological deficit should undergo surgery without a biopsy should be discussed with the patient.

The majority of recommendations developed were graded as B and C, while the levels of the identified sources of evidence received grades of II–III, especially in regard to primary malignant spinal tumours. The rarity of these tumours is responsible for the paucity of data regarding their management and lack of higher levels of evidence usually achieved through high-quality therapeutic studies including larger numbers of analysed patients.

Conclusions

The developed recommendations together with the national network of expertise should optimize the management of patients with spinal tumours, especially those with rare malignancies, and optimize their referral and allocation within the Polish NHS.

References

Andritsch E, Beishon M, Bielack S et al (2017) ECCO essential requirements for quality cancer care: soft tissue sarcoma in adults and bone sarcoma. A critical review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 110:94–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.12.002

Grades of recommendation. https://www.spine.org/Research-Clinical-Care/Research/Grades-of-Recommendation

https://www.spine.org/Portals/0/assets/downloads/ResearchClinicalCare/LevelsOfEvidence.pdf

Buhmann S, Becker C, Duerr HR, Reiser M, Baur-Melnyk A (2009) Detection of osseous metastases of the spine: comparison of high resolution multi-detector-CT with MRI. Eur J Radiol 69:567–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.11.039

Sutcliffe P, Connock M, Shyangdan D, Court R, Kandala NB, Clarke A (2013) A systematic review of evidence on malignant spinal metastases: natural history and technologies for identifying patients at high risk of vertebral fracture and spinal cord compression. Health Technol Assess 17:1–274. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta17420

Algra PR, Bloem JL, Tissing H, Falke TH, Arndt JW, Verboom LJ (1991) Detection of vertebral metastases: comparison between MR imaging and bone scintigraphy. Radiographics 11:219–232. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.11.2.2028061

Kim JK, Learch TJ, Colletti PM, Lee JW, Tran SD, Terk MR (2000) Diagnosis of vertebral metastasis, epidural metastasis, and malignant spinal cord compression: are T1-weighted sagittal images sufficient? Magn Reson Imaging 18:819–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0730-725x(00)00181-8

Venkitaraman R, Sohaib SA, Barbachano Y, Parker CC, Khoo V, Huddart RA, Horwich A, Dearnaley DP (2007) Detection of occult spinal cord compression with magnetic resonance imaging of the spine. Clin Oncol 19:528–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2007.04.001

Bayley A, Milosevic M, Blend R, Logue J, Gospodarowicz M, Boxen I, Warde P, McLean M, Catton C, Catton P (2001) A prospective study of factors predicting clinically occult spinal cord compression in patients with metastatic prostate carcinoma. Cancer 92:303–310. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(20010715)92:2%3c303::aid-cncr1323%3e3.0.co;2-f

Bilsky MH, Laufer I, Fourney DR, Groff M, Schmidt MH, Varga PP, Vrionis FD, Yamada Y, Gerszten PC, Kuklo TR (2010) Reliability analysis of the epidural spinal cord compression scale. J Neurosurg Spine 13:324–328. https://doi.org/10.3171/2010.3.spine09459

Fourney DR, Frangou EM, Ryken TC et al (2011) Spinal instability neoplastic score: an analysis of reliability and validity from the spine oncology study group. J Clin Oncol 29:3072–3077. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2010.34.3897

Fisher CG, Schouten R, Versteeg AL et al (2014) Reliability of the spinal instability neoplastic score (SINS) among radiation oncologists: an assessment of instability secondary to spinal metastases. Radiat Oncol 9:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717x-9-69

Shi YJ, Li XT, Zhang XY, Liu YL, Tang L, Sun YS (2017) Differential diagnosis of hemangiomas from spinal osteolytic metastases using 3.0 T MRI: comparison of T1-weighted imaging, chemical-shift imaging, diffusion-weighted and contrast-enhanced imaging. Oncotarget 8:71095

Amini B, Patel K, Westmark RM, Westmark KD, Gonzalez A (2020) 27 approach to the solitary vertebral lesion on magnetic resonance imaging. Radiol Key. https://doi.org/10.1055/b-0040-17686327

Yin H, Zhou W, Yu H, Li B, Zhang D, Wu Z, Liu T, Xiao J (2014) Clinical characteristics and treatment options for two types of osteoblastoma in the mobile spine: a retrospective study of 32 cases and outcomes. Eur Spine J 23:411–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-013-3049-1

Veltri A, Bargellini I, Giorgi L, Almeida PAMS, Akhan O (2017) CIRSE guidelines on percutaneous needle biopsy (PNB). CardioVasc Interv Radiol 40:1501–1513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-017-1658-5

Tehranzadeh J, Tao C, Browning CA (2007) Percutaneous needle biopsy of the spine. Acta Radiol 48:860–868. https://doi.org/10.1080/02841850701459783

Ravikanth R (2020) Diagnostic yield and technical aspects of fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous transpedicular biopsy of the spine: a single-center retrospective analysis of outcomes and review of the literature. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine 11:93–98. https://doi.org/10.4103/jcvjs.JCVJS_43_20

Schweitzer ME, Gannon FH, Deely DM, O’Hara BJ, Juneja V (1996) Percutaneous skeletal aspiration and core biopsy: complementary techniques. Am J Roentgenol 166:415–418. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.166.2.8553958

Liang Y, Liu P, Jiang LB, Wang HL, Hu AN, Zhou XG, Li XL, Lin H, Wu D, Dong J (2019) Value of CT-guided core needle biopsy in diagnosing spinal lesions: a comparison study. Orthop Surg 11:60–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/os.12418

Springfield DS, Rosenberg A (1996) Editorial—biopsy. J Bone Jt Surg 78:639–643. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-199605000-00001

Mukherjee D, Chaichana KL, Gokaslan ZL, Aaronson O, Cheng JS, McGirt MJ (2011) Survival of patients with malignant primary osseous spinal neoplasms: results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from 1973 to 2003. J Neurosurg Spine 14:143–150. https://doi.org/10.3171/2010.10.spine10189

Oitment C, Bozzo A, Martin AR, Rienmuller A, Jentzsch T, Aoude A, Thornley P, Ghert M, Rampersaud R (2021) Primary sarcomas of the spine: population-based demographic and survival data in 107 spinal sarcomas over a 23-year period in Ontario, Canada. Spine J 21:296–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2020.09.004

Heery CR (2016) Chordoma: the quest for better treatment options. Oncol Ther 4:35–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-016-0016-0

Boriani S (2018) En bloc resection in the spine: a procedure of surgical oncology. J Spine Surg 4:668–676. https://doi.org/10.21037/jss.2018.09.02

Boriani S, Weinstein JN, Biagini R (1997) Primary bone tumors of the spine terminology and surgical staging. Spine 22:1036–1044. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199705010-00020

Chan P, Boriani S, Fourney DR et al (2009) An assessment of the reliability of the enneking and Weinstein–Boriani–Biagini classifications for staging of primary spinal tumors by the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine 34:384–391. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0b013e3181971283

Enneking WF, Spanier SS, Goodman MA (1980) A system for the surgical staging of musculoskeletal sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 153:106–120. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-198011000-00013

Tomita K, Kawahara N, Baba H, Tsuchiya H, Fujita T, Toribatake Y (1997) Total en bloc spondylectomy. A new surgical technique for primary malignant vertebral tumors. Spine 22:324–333. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199702010-00018

Wang Y, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Huang P, Xiao S, Wang Z, Liu Z, Liu B, Lu N, Mao K (2008) A single posterior approach for multilevel modified vertebral column resection in adults with severe rigid congenital kyphoscoliosis: a retrospective study of 13 cases. Eur Spine J 17:361–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-007-0566-9

Wang Y, Zhang YG, Zhang XS, Wang Z, Mao K, Chen C, Zheng GQ, Li G, Wood KB (2009) Posterior-only multilevel modified vertebral column resection for extremely severe Pott’s kyphotic deformity. Eur Spine J 18:1436–1441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-009-1067-9

Grunewald TG, Alonso M, Avnet S et al (2020) Sarcoma treatment in the era of molecular medicine. EMBO Mol Med 12:e11131. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.201911131

Brown HK, Schiavone K, Gouin F, Heymann MF, Heymann D (2018) Biology of bone sarcomas and new therapeutic developments. Calcif Tissue Int 102:174–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-017-0372-2

National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (2006) Improving outcomes for people with sarcoma. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/csg9/resources/improving-outcomes-for-people-with-sarcoma-update-773381485

WHO Classification of Tumours (2020) Bone and soft tissue tumours. IARC Press, Lyon

Casali PG, Bielack S, Abecassis N et al (2018) Bone sarcomas: ESMO-PaedCan-EURACAN clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 29:iv79–iv95. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy310

Marina NM, Smeland S, Bielack SS et al (2016) Comparison of MAPIE versus MAP in patients with a poor response to preoperative chemotherapy for newly diagnosed high-grade osteosarcoma (EURAMOS-1): an open-label, international, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 17:1396–1408. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30214-5

Whelan JS, Bielack SS, Marina N et al (2015) EURAMOS-1, an international randomised study for osteosarcoma: results from pre-randomisation treatment. Ann Oncol 26:407–414. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu526

Ferrari S, Smeland S, Mercuri M et al (2005) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with high-dose Ifosfamide, high-dose methotrexate, cisplatin, and doxorubicin for patients with localized osteosarcoma of the extremity: a joint study by the Italian and Scandinavian Sarcoma Groups. J Clin Oncol 23:8845–8852. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2004.00.5785

Bajpai J, Chandrasekharan A, Talreja V, Simha V, Chandrakanth MV, Rekhi B, Khurana S, Khan A, Vora T, Ghosh J, Banavali SD, Gupta S (2017) Outcomes in non-metastatic treatment naive extremity osteosarcoma patients treated with a novel non-high dosemethotrexate-based, dose-dense combination chemotherapy regimen ‘OGS-12.’ Eur J Cancer 85:49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2017.08.013

Piperno-Neumann S, Ray-Coquard I, Occean BV et al (2020) Results of API–AI based regimen in osteosarcoma adult patients included in the French OS2006/Sarcome-09 study. Int J Cancer 146:413–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.32526

Ferrari S, Bielack SS, Smeland S et al (2018) EURO-BOSS: a European study on chemotherapy in bone-sarcoma patients aged over 40: outcome in primary high-grade osteosarcoma. Tumori J 104:30–36. https://doi.org/10.5301/tj.5000696

Bielack SS, Smeland S, Whelan JS et al (2015) Methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MAP) plus maintenance pegylated interferon alfa-2b versus MAP alone in patients with resectable high-grade osteosarcoma and good histologic response to preoperative MAP: rirst results of the EURAMOS-1 good response randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 33:2279–2287. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.60.0734

van Doorninck JA, Ji L, Schaub B, Shimada H, Wing MR, Krailo MD, Lessnick SL, Marina N, Triche TJ, Sposto R, Womer RB, Lawlor ER (2010) Current treatment protocols have eliminated the prognostic advantage of type 1 fusions in Ewing sarcoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 28:1989–1994. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.24.5845

Schuck A, Ahrens S, Paulussen M, Kuhlen M, Könemann S, Rübe C, Winkelmann W, Kotz R, Dunst J, Willich N, Jürgens H (2003) Local therapy in localized Ewing tumors: results of 1058 patients treated in the CESS 81, CESS 86, and EICESS 92 trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 55:168–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0360-3016(02)03797-5

Womer RB, West DC, Krailo MD, Dickman PS, Pawel BR, Grier HE, Marcus K, Sailer S, Healey JH, Dormans JP, Weiss AR (2012) Randomized controlled trial of interval-compressed chemotherapy for the treatment of localized Ewing sarcoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 30:4148–4154. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.41.5703

Le Deley MC, Paulussen M, Lewis I et al (2014) Cyclophosphamide compared with ifosfamide in consolidation treatment of standard-risk Ewing sarcoma: results of the randomized noninferiority Euro-EWING99-R1 trial. J Clin Oncol 32:2440–2448. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.54.4833

Brennan B, Kirton L, Marec-Berard P, Martin-Broto J, Gelderblom H, Gaspar N, Strauss SJ, Sastre Urgelles A, Anderton J, Laurence V, Whelan J, Wheatley K (2020) Comparison of two chemotherapy regimens in Ewing sarcoma (ES): overall and subgroup results of the Euro Ewing 2012 randomized trial (EE2012). J Clin Oncol 38:11500. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2020.38.15_suppl.11500

DuBois SG, Krailo MD, Gebhardt MC et al (2014) Comparative evaluation of local control strategies in localized Ewing sarcoma of bone: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer 121:467–475. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29065

Schuck A, Ahrens S, von Schorlemer I, Kuhlen M, Paulussen M, Hunold A, Gosheger G, Winkelmann W, Dunst J, Willich N, Jürgens H (2005) Radiotherapy in Ewing tumors of the vertebrae: treatment results and local relapse analysis of the CESS 81/86 and EICESS 92 trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 63:1562–1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.036

DeLaney TF, Liebsch NJ, Pedlow FX et al (2014) Long-term results of phase II study of high dose photon/proton radiotherapy in the management of spine chordomas, chondrosarcomas, and other sarcomas. J Surg Oncol 110:115–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23617

Talac R, Yaszemski MJ, Currier BL, Fuchs B, Dekutoski MB, Kim CW, Sim FH (2002) Relationship between surgical margins and local recurrence in sarcomas of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res 397:127–132. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-200204000-00018

Ruengwanichayakun P, Gambarotti M, Frisoni T, Gibertoni D, Guaraldi F, Sbaraglia M, Dei Tos AP, Picci P, Righi A (2019) Parosteal osteosarcoma: a monocentric retrospective analysis of 195 patients. Hum Pathol 91:11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2019.05.009

Fisher CG, Saravanja DD, Dvorak MF, Rampersaud YR, Clarkson PW, Hurlbert J, Fox R, Zhang H, Lewis S, Riaz S, Ferguson PC, Boyd MC (2011) Surgical management of primary bone tumors of the spine. Spine 36:830–836. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0b013e3181e502e5

Amendola L, Cappuccio M, De Iure F, Bandiera S, Gasbarrini A, Boriani S (2014) En bloc resections for primary spinal tumors in 20 years of experience: effectiveness and safety. Spine J 14:2608–2617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2014.02.030

Sciubba DM, Ramos RDLG, Goodwin CR, Xu R, Bydon A, Witham TF, Gokaslan ZL, Wolinsky JP (2016) Total en bloc spondylectomy for locally aggressive and primary malignant tumors of the lumbar spine. Eur Spine J 25:4080–4087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4641-y

Luzzati AD, Shah S, Gagliano F, Perrucchini G, Scotto G, Alloisio M (2015) Multilevel en bloc spondylectomy for tumors of the thoracic and lumbar spine is challenging but rewarding. Clin Orthop Relat Res 473:858–867. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-3578-x

Goda JS, Ferguson PC, O’Sullivan B, Catton CN, Griffin AM, Wunder JS, Bell RS, Kandel RA, Chung PW (2011) High-risk extracranial chondrosarcoma: long-term results of surgery and radiation therapy. Cancer 117:2513–2519. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25806

Noël G, Feuvret L, Ferrand R, Boisserie G, Mazeron JJ, Habrand JL (2004) Radiotherapeutic factors in the management of cervical-basal chordomas and chondrosarcomas. Neurosurgery 55:1252–1262. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.neu.0000143330.30405.aa

Ares C, Hug EB, Lomax AJ, Bolsi A, Timmermann B, Rutz HP, Schuller JC, Pedroni E, Goitein G (2009) Effectiveness and safety of spot scanning proton radiation therapy for chordomas and chondrosarcomas of the skull base: first long-term report. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 75:1111–1118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.055

Hug EB, Loredo LN, Slater JD, Devries A, Grove RI, Schaefer RA, Rosenberg AE, Slater JM (1999) Proton radiation therapy for chordomas and chondrosarcomas of the skull base. J Neurosurg 91:432–439. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1999.91.3.0432

Krochak R, Harwood AR, Cummings BJ, Quirt IC (1983) Results of radical radiation for chondrosarcoma of bone. Radiother Oncol 1:109–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-8140(83)80014-0

McNaney D, Lindberg RD, Ayala AG, Barkley HT, Hussey DH (1982) Fifteen year radiotherapy experience with chondrosarcoma of bone. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 8:187–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-3016(82)90512-0

Dekutoski MB, Clarke MJ, Rose P et al (2016) Osteosarcoma of the spine: prognostic variables for local recurrence and overall survival, a multicenter ambispective study. J Neurosurg Spine 25:59–68. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.11.spine15870

Pombo B, Ferreira AC, Cardoso P, Oliveira A (2019) Clinical effectiveness of Enneking appropriate versus Enneking inappropriate procedure in patients with primary osteosarcoma of the spine: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur Spine J 29:238–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-06099-7

Ciernik IF, Niemierko A, Harmon DC, Kobayashi W, Chen Y-L, Yock TI, Ebb DH, Choy E, Raskin KA, Liebsch N, Hornicek FJ, Delaney TF (2011) Proton-based radiotherapy for unresectable or incompletely resected osteosarcoma. Cancer 117:4522–4530. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26037

Matsunobu A, Imai R, Kamada T, Imaizumi T, Tsuji H, Tsujii H, Shioyama Y, Honda H, Tatezaki SI (2012) Impact of carbon ion radiotherapy for unresectable osteosarcoma of the trunk. Cancer 118:4555–4563. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27451

Spałek MJ, Poleszczuk J, Czarnecka AM et al (2021) Radiotherapy in the management of pediatric and adult osteosarcomas: a multi-institutional cohort analysis. Cells 10:366. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10020366

DeLaney TF, Park L, Goldberg SI, Hug EB, Liebsch NJ, Munzenrider JE, Suit HD (2005) Radiotherapy for local control of osteosarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 61:492–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.051

Nesbit ME, Gehan EA, Burgert EO, Vietti TJ, Cangir A, Tefft M, Evans R, Thomas P, Askin FB, Kissane JM (1990) Multimodal therapy for the management of primary, nonmetastatic Ewing’s sarcoma of bone: a long-term follow-up of the First Intergroup study. J Clin Oncol 8:1664–1674. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1990.8.10.1664

Foulon S, Brennan B, Gaspar N et al (2016) Can postoperative radiotherapy be omitted in localised standard-risk Ewing sarcoma? An observational study of the Euro-EWING group. Eur J Cancer 61:128–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.075

Rombi B, DeLaney TF, MacDonald SM, Huang MS, Ebb DH, Liebsch NJ, Raskin KA, Yeap BY, Marcus KJ, Tarbell NJ, Yock TI (2012) Proton radiotherapy for pediatric Ewing’s sarcoma: initial clinical outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 82:1142–1148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.03.038

Gokaslan ZL, Zadnik PL, Sciubba DM et al (2016) Mobile spine chordoma: results of 166 patients from the AOSpine Knowledge Forum Tumor database. J Neurosurg Spine 24:644–651. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.7.SPINE15201

Zhou J, Yang B, Wang X, Jing Z (2018) Comparison of the effectiveness of radiotherapy with photons and particles for chordoma after surgery: a meta-analysis. World Neurosurg 117:46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.05.209

Rutz HP, Weber DC, Sugahara S, Timmermann B, Lomax AJ, Bolsi A, Pedroni E, Coray A, Jermann M, Goitein G (2007) Extracranial chordoma: outcome in patients treated with function-preserving surgery followed by spot-scanning proton beam irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 67:512–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.08.052

Carpentier A, Polivka M, Blanquet A, Lot G, George B (2002) Suboccipital and cervical chordomas: the value of aggressive treatment at first presentation of the disease. J Neurosurg 97:1070–1077. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2002.97.5.1070

Kabolizadeh P, Chen YL, Liebsch N, Hornicek FJ, Schwab JH, Choy E, Rosenthal DI, Niemierko A, DeLaney TF (2017) Updated outcome and analysis of tumor response in mobile spine and sacral chordoma treated with definitive high-dose photon/proton radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 97:254–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.10.006

Boriani S, Amendola L, Bandiera S, Simoes CE, Alberghini M, Di Fiore M, Gasbarrini A (2012) Staging and treatment of osteoblastoma in the mobile spine: a review of 51 cases. Eur Spine J 21:2003–2010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-012-2395-8

Cao S, Chen K, Jiang L, Wei F, Liu X, Liu Z (2022) Intralesional marginal resection for osteoblastoma in the mobile spine: experience from a single center. Front Surg 9:838235. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2022.838235

Versteeg AL, Dea N, Boriani S et al (2017) Surgical management of spinal osteoblastomas. J Neurosurg Spine 27:321–327. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.1.spine16788

Ozsahin M, Tsang RW, Poortmans P et al (2006) Outcomes and patterns of failure in solitary plasmacytoma: a multicenter Rare Cancer Network study of 258 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 64:210–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.06.039

Reed V, Shah J, Medeiros LJ, Ha CS, Mazloom A, Weber DM, Arzu IY, Orlowski RZ, Thomas SK, Shihadeh F, Alexanian R, Dabaja BS (2011) Solitary plasmacytomas: outcome and prognostic factors after definitive radiation therapy. Cancer 117:4468–4474. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26031

Frassica DA, Frassica FJ, Schray MF, Sim FH, Kyle RA (1989) Solitary plasmacytoma of bone: mayo clinic experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 16:43–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-3016(89)90008-4

Gouin F, Rochwerger AR, Di Marco A, Rosset P, Bonnevialle P, Fiorenza F, Anract P (2014) Adjuvant treatment with zoledronic acid after extensive curettage for giant cell tumours of bone. Eur J Cancer 50:2425–2431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2014.06.003

Chawla S, Blay JY, Rutkowski P et al (2019) Denosumab in patients with giant-cell tumour of bone: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 20:1719–1729. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(19)30663-1

Rutkowski P, Gaston L, Borkowska A et al (2018) Denosumab treatment of inoperable or locally advanced giant cell tumor of bone—multicenter analysis outside clinical trial. Eur J Surg Oncol 44:1384–1390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.03.020

Rutkowski P, Ferrari S, Grimer RJ, Stalley PD, Dijkstra SPD, Pienkowski A, Vaz G, Wunder JS, Seeger LL, Feng A, Roberts ZJ, Bach BA (2015) Surgical downstaging in an open-label phase II trial of denosumab in patients with giant cell tumor of bone. Ann Surg Oncol 22:2860–2868. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4634-9

Müther M, Schwake M, Suero Molina E, Schroeteler J, Stummer W, Klingenhöfer M, Ewelt C (2021) Multiprofessional management of giant cell tumors in the cervical spine: a systematic review. World Neurosurg 151:53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2021.04.006

Gupta AK, Phukan P, Bodhey N (2021) Percutaneous vertebroplasty for the treatment of symptomatic vertebral hemangioma with long-term follow-up. Interdiscip Neurosurg 23:100968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inat.2020.100968

Heyd R, Seegenschmiedt MH, Rades D, Winkler C, Eich HT, Bruns F, Gosheger G, Willich N, Micke O (2010) Radiotherapy for symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas: results of a multicenter study and literature review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 77:217–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.055

Kato S, Kawahara N, Murakami H, Demura S, Yoshioka K, Okayama T, Fujita T, Tomita K (2010) Surgical management of aggressive vertebral hemangiomas causing spinal cord compression: long-term clinical follow-up of five cases. J Orthop Sci 15:350–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00776-010-1483-z

Sagoo NS, Haider AS, Chen AL et al (2022) Radiofrequency ablation for spinal osteoid osteoma: a systematic review of safety and treatment outcomes. Surg Oncol 41:101747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2022.101747

Izzo A, Zugaro L, Fascetti E, Bruno F, Zoccali C, Arrigoni F (2021) Management of osteoblastoma and giant osteoid osteoma with percutaneous thermoablation techniques. J Clin Med 10:5717. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10245717

Aiba H, Hayashi K, Inatani H, Satoshi Y, Watanabe N, Sakurai H, Tsuchiya H, Otsuka T (2014) Conservative treatment for patients with osteoid osteoma: a case series. Anticancer Res 34:3721–3725

Tsoumakidou G, Thénint MA, Garnon J, Buy X, Steib JP, Gangi A (2016) Percutaneous image-guided laser photocoagulation of spinal osteoid osteoma: a single-institution series. Radiology 278:936–943. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2015150491

Meng L, Zhang X, Xu R, Wu B, Zhang X, Wei Y, Li J, Shan H, Xiao Y (2021) A preliminary comparative study of percutaneous CT-guided cryoablation with surgical resection for osteoid osteoma. PeerJ 9:e10724. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10724

Yakkanti R, Onyekwelu I, Carreon LY, Dimar JR (2018) Solitary osteochondroma of the spine-a case series: review of solitary osteochondroma with myelopathic symptoms. Glob Spine J 8:323–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568217701096

Boriani S, De Iure F, Campanacci L, Gasbarrini A, Bandiera S, Biagini R, Bertoni F, Picci P (2001) Aneurysmal bone cyst of the mobile spine: report on 41 cases. Spine 26:27–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200101010-00007

Zhao Y, He S, Sun H, Cai X, Gao X, Wang P, Wei H, Xu W, Xiao J (2019) Symptomatic aneurysmal bone cysts of the spine: clinical features, surgical outcomes, and prognostic factors. Eur Spine J 28:1537–1545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-05920-7

Zileli M, Isik HS, Ogut FE, Is M, Cagli S, Calli C (2013) Aneurysmal bone cysts of the spine. Eur Spine J 22:593–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-012-2510-x

Parker J, Soltani S, Boissiere L, Obeid I, Gille O, Kieser DC (2019) Spinal aneurysmal bone cysts (ABCs): optimal management. Orthop Res Rev 11:159–166. https://doi.org/10.2147/ORR.S211834

Elsayad K, Kriz J, Seegenschmiedt H, Imhoff D, Heyd R, Eich HT, Micke O (2016) Radiotherapy for aneurysmal bone cysts: a rare indication. Strahlenther Onkol 193:332–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-016-1085-6

Charest-Morin R, Fisher CG, Varga PP et al (2017) En bloc resection versus intralesional surgery in the treatment of giant cell tumor of the spine. Spine 42:1383–1390. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0000000000002094

Luksanapruksa P, Buchowski JM, Singhatanadgige W, Rose PC, Bumpass DB (2016) Management of spinal giant cell tumors. Spine J 16:259–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2015.10.045

Boriani S, Cecchinato R, Cuzzocrea F, Bandiera S, Gambarotti M, Gasbarrini A (2019) Denosumab in the treatment of giant cell tumor of the spine. Preliminary report, review of the literature and protocol proposal. Eur Spine J 29:257–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-05997-0

Stanton RP, Ippolito E, Springfield D, Lindaman L, Wientroub S, Leet A (2012) The surgical management of fibrous dysplasia of bone. Orphanet J Rare Dis 7(Suppl 1):S1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-7-S1-S1

Hassan BW, Moon BJ, Kim YJ, Kim SD, Choi KY, Lee JK (2016) Langerhans cell histiocytosis in the adult lumbar spine: case report. Springerplus 5:1398. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-3006-7

Chen L, Chen Z, Wang Y (2018) Langerhans cell histiocytosis at L5 vertebra treated with en bloc vertebral resection: a case report. World J Surg Oncol 16:96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1399-1

Kim SD, Moon BJ, Choi KY, Lee JK (2017) Primary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) in the adult cervical spine: a case report and review of the literature. Interdiscip Neurosurg 7:56–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inat.2016.11.008

Conti A, Acker G, Kluge A, Loebel F, Kreimeier A, Budach V, Vajkoczy P, Ghetti I, Germano AF, Senger C (2019) Decision making in patients with metastatic spine. The role of minimally invasive treatment modalities. Front Oncol 9:915. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00915

Ahmed AK, Goodwin CR, Heravi A, Kim R, Abu-Bonsrah N, Sankey E, Kerekes D, Ramos RDLG, Schwab J, Sciubba DM (2018) Predicting survival for metastatic spine disease: a comparison of nine scoring systems. Spine J 18:1804–1814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2018.03.011

Pennington Z, Ahmed AK, Westbroek EM, Cottrill E, Lubelski D, Goodwin ML, Sciubba DM (2019) SINS score and stability: evaluating the need for stabilization within the uncertain category. World Neurosurg 128:e1034–e1047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.05.067

Laufer I, Rubin DG, Lis E, Cox BW, Stubblefield MD, Yamada Y, Bilsky MH (2013) The NOMS framework: approach to the treatment of spinal metastatic tumors. Oncologist 18:744–751. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0293

Takagi T, Katagiri H, Kim Y et al (2015) Skeletal metastasis of unknown primary origin at the initial visit: a retrospective analysis of 286 cases. PLoS One 10:e0129428. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129428

Vecht CJ, Haaxma-Reiche H, van Putten WLJ, Visser M, Vries EP, Twijnstra A (1989) Initial bolus of conventional versus high-dose dexamethasone in metastatic spinal cord compression. Neurology 39:1255–1257. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.39.9.1255

Skeoch GD, Tobin MK, Khan S, Linninger AA, Mehta AI (2017) Corticosteroid treatment for metastatic spinal cord compression: a review. Glob Spine J 7:272–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568217699189

Weber M, Kumar A (2015) Spinal metastases and steroid treatment: a systematic review. Glob Spine J 5:s-003-51554325-s−1550035-1554325. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1554325

Orenday-Barraza JM, Cavagnaro MJ, Avila MJ, Strouse IM, Dowell A, Kisana H, Khan N, Ravinsky R, Baaj AA (2022) 10-year trends in the surgical management of patients with spinal metastases: a scoping review. World Neurosurg 157:170-186.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2021.10.086

Spiessberger A, Arvind V, Gruter B, Cho SK (2020) Thoracolumbar corpectomy/spondylectomy for spinal metastasis: a pooled analysis comparing the outcome of seven different surgical approaches. Eur Spine J 29:248–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-06179-8

Pennington Z, Ahmed AK, Molina CA, Ehresman J, Laufer I, Sciubba DM (2018) Minimally invasive versus conventional spine surgery for vertebral metastases: a systematic review of the evidence. Ann Transl Med 6:103. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2018.01.28

Germano IM, Carai A, Pawha P, Blacksburg S, Lo YC, Green S (2016) Clinical outcome of vertebral compression fracture after single fraction spine radiosurgery for spinal metastases. Clin Exp Metastasis 33:143–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-015-9764-8

Kato S, Demura S, Shinmura K, Yokogawa N, Shimizu T, Murakami H, Kawahara N, Tomita K, Tsuchiya H (2021) Surgical metastasectomy in the spine: a review article. Oncologist 26:e1833–e1843. https://doi.org/10.1002/onco.13840

Domenicucci M, Nigro L, Delfini R (2018) Total en-bloc spondylectomy through a posterior approach: technique and surgical outcome in thoracic metastases. Acta Neurochir 160:1373–1376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-018-3572-2

Tomita K, Kawahara N, Murakami H, Demura S (2006) Total en bloc spondylectomy for spinal tumors: improvement of the technique and its associated basic background. J Orthop Sci 11:3–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00776-005-0964-y

Nas ÖF, İnecikli MF, Hacıkurt K, Büyükkaya R, Özkaya G, Özkalemkaş F, Ali R, Erdoğan C, Hakyemez B (2016) Effectiveness of percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients with multiple myeloma having vertebral pain. Diagn Interv Radiol 22:263–268. https://doi.org/10.5152/dir.2016.15201

Papanastassiou ID, Vrionis FD (2016) Is early vertebroplasty/kyphoplasty justified in multiple myeloma given the rapid vertebral fracture progression? Spine J 16:833–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2015.12.083

Fan Y, Zhou X, Wang H, Jiang P, Cai S, Zhang J, Liu Y (2016) The timing of surgical intervention in the treatment of complete motor paralysis in patients with spinal metastasis. Eur Spine J 25:4060–4066. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4406-7

Laufer I, Zuckerman SL, Bird JE, Bilsky MH, Lazáry Á, Quraishi NA, Fehlings MG, Sciubba DM, Shin JH, Mesfin A, Sahgal A, Fisher CG (2016) Predicting neurologic recovery after surgery in patients with deficits secondary to MESCC: systematic review. Spine 41(Suppl 20):S224–S230. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000001827

Boriani S, Tedesco G, Ming L, Ghermandi R, Amichetti M, Fossati P, Krengli M, Mavilla L, Gasbarrini A (2017) Carbon-fiber-reinforced PEEK fixation system in the treatment of spine tumors: a preliminary report. Eur Spine J 27:874–881. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5258-5

Krätzig T, Mende KC, Mohme M, Kniep H, Dreimann M, Stangenberg M, Westphal M, Gauer T, Eicker SO (2020) Carbon fiber–reinforced PEEK versus titanium implants: an in vitro comparison of susceptibility artifacts in CT and MR imaging. Neurosurg Rev 44:2163–2170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-020-01384-2

Trungu S, Ricciardi L, Forcato S, Scollato A, Minniti G, Miscusi M, Raco A (2021) Anterior corpectomy and plating with carbon-PEEK instrumentation for cervical spinal metastases: clinical and radiological outcomes. J Clin Med 10:5910. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10245910

Berjano P, Baroncini A, Cecchinato R, Langella F, Boriani S (2021) En-bloc resection of a chordoma in L3 by a combined open posterior and less invasive retroperitoneal approach: technical description and case report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-021-04177-4

Murthy NK, Wolinsky JP (2021) Utility of carbon fiber instrumentation in spinal oncology. Heliyon 7:e07766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07766

Wagner A, Haag E, Joerger A-K, Jost P, Combs SE, Wostrack M, Gempt J, Meyer B (2021) Comprehensive surgical treatment strategy for spinal metastases. Sci Rep 11:7988. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87121-1

Brookes MJ, Chan CD, Baljer B, Wimalagunaratna S, Crowley TP, Ragbir M, Irwin A, Gamie Z, Beckingsale T, Ghosh KM, Rankin KS (2021) Surgical advances in osteosarcoma. Cancers 13:388. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13030388

Park SJ, Lee KH, Lee CS, Jung JY, Park JH, Kim GL, Kim KT (2020) Instrumented surgical treatment for metastatic spinal tumors: is fusion necessary? J Neurosurg Spine 32:456–464. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.8.spine19583

Hong CG, Cho JH, Suh DC, Hwang CJ, Lee DH, Lee CS (2017) Preoperative embolization in patients with metastatic spinal cord compression: mandatory or optional? World J Surg Oncol 15:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-017-1118-3

Ryu S, Deshmukh S, Timmerman RD et al (2019) Radiosurgery compared to external beam radiotherapy for localized spine metastasis: phase III results of NRG oncology/RTOG 0631. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 105:S2–S3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.06.382

Sahgal A, Myrehaug SD, Siva S et al (2020) CCTG SC.24/TROG 17.06: a randomized phase II/III study comparing 24Gy in 2 stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) fractions versus 20Gy in 5 conventional palliative radiotherapy (CRT) fractions for patients with painful spinal metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 108:1397–1398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.09.019

Gerszten PC, Burton SA, Ozhasoglu C, Welch WC (2007) Radiosurgery for spinal metastases: clinical experience in 500 cases from a single institution. Spine 32:193–199. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000251863.76595.a2

Tao R, Bishop AJ, Brownlee Z et al (2016) Stereotactic body radiation therapy for spinal metastases in the postoperative setting: a secondary analysis of mature phase 1–2 trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 95:1405–1413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.03.022

Ryu S, Pugh SL, Gerszten PC, Yin F-F, Timmerman RD, Hitchcock YJ, Movsas B, Kanner AA, Berk LB, Followill DS, Kachnic LA (2014) RTOG 0631 phase 2/3 study of image guided stereotactic radiosurgery for localized (1–3) spine metastases: phase 2 results. Pract Radiat Oncol 4:76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prro.2013.05.001

Miller JA, Balagamwala EH, Berriochoa CA, Angelov L, Suh JH, Benzel EC, Mohammadi AM, Emch T, Magnelli A, Godley A, Qi P, Chao ST (2017) The impact of decompression with instrumentation on local failure following spine stereotactic radiosurgery. J Neurosurg Spine 27:436–443. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.3.spine161015

Husain ZA, Sahgal A, De Salles A et al (2017) Stereotactic body radiotherapy for de novo spinal metastases: systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine 27:295–302. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.1.spine16684

Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S et al (2020) Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for the comprehensive treatment of oligometastatic cancers: long-term results of the SABR-COMET phase II randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 38:2830–2838. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.00818

Myrehaug S, Sahgal A, Hayashi M, Levivier M, Ma L, Martinez R, Paddick I, Régis J, Ryu S, Slotman B, De Salles A (2017) Reirradiation spine stereotactic body radiation therapy for spinal metastases: systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine 27:428–435. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.2.spine16976

Spratt DE, Beeler WH, de Moraes FY et al (2017) An integrated multidisciplinary algorithm for the management of spinal metastases: an international spine oncology consortium report. Lancet Oncol 18:e720–e730. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30612-5

Thirion PG, Dunne MT, Kelly PJ et al (2020) Non-inferiority randomised phase 3 trial comparing two radiation schedules (single vs. five fractions) in malignant spinal cord compression. Br J Cancer 122:1315–1323. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-0768-z

Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, Payne R, Saris S, Kryscio RJ, Mohiuddin M, Young B (2005) Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet 366:643–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)66954-1

George R, Jeba J, Ramkumar G, Chacko AG, Tharyan P (2015) Interventions for the treatment of metastatic extradural spinal cord compression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006716.pub3

Di Perna G, Cofano F, Mantovani C, Badellino S, Marengo N, Ajello M, Comite LM, Palmieri G, Tartara F, Zenga F, Ricardi U, Garbossa D (2020) Separation surgery for metastatic epidural spinal cord compression: a qualitative review. J Bone Oncol 25:100320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbo.2020.100320

Barzilai O, Amato MK, McLaughlin L, Reiner AS, Ogilvie SQ, Lis E, Yamada Y, Bilsky MH, Laufer I (2018) Hybrid surgery–radiosurgery therapy for metastatic epidural spinal cord compression: a prospective evaluation using patient-reported outcomes. Neurooncol Pract 5:104–113. https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npx017

Itshayek E, Cohen JE, Yamada Y, Gokaslan Z, Polly DW, Rhines LD, Schmidt MH, Varga PP, Mahgarefteh S, Fraifeld S, Gerszten PC, Fisher CG (2014) Timing of stereotactic radiosurgery and surgery and wound healing in patients with spinal tumors: a systematic review and expert opinions. Neurol Res 36:510–523. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743132814y.0000000380

Azad TD, Varshneya K, Herrick DB, Pendharkar AV, Ho AL, Stienen M, Zygourakis C, Bagshaw HP, Veeravagu A, Ratliff JK, Desai A (2021) Timing of adjuvant radiation therapy and risk of wound-related complications among patients with spinal metastatic disease. Glob Spine J 11:44–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568219889363

Degen JW, Gagnon GJ, Voyadzis J-M, McRae DA, Lunsden M, Dieterich S, Molzahn I, Henderson FC (2005) CyberKnife stereotactic radiosurgical treatment of spinal tumors for pain control and quality of life. J Neurosurg Spine 2:540–549. https://doi.org/10.3171/spi.2005.2.5.0540

Roesch J, Cho JBC, Fahim DK et al (2017) Risk for surgical complications after previous stereotactic body radiotherapy of the spine. Radiat Oncol 12:153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-017-0887-8

Versteeg AL, van der Velden JM, Hes J, Eppinga W, Kasperts N, Verkooijen HM, Oner FC, Seravalli E, Verlaan JJ (2018) Stereotactic radiotherapy followed by surgical stabilization within 24 h for unstable spinal metastases; a stage I/IIa study according to the IDEAL framework. Front Oncol 8:626. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2018.00626

Lin PC, Hsu FM, Chen YH, Xiao F (2018) Neoadjuvant stereotactic body radiation therapy for spine metastases. J Spine Neurosurg 7(2). https://doi.org/10.4172/2325-9701.1000298

Kumar N, Madhu S, Bohra H, Pandita N, Wang SSY, Lopez KG, Tan JH, Vellayappan BA (2020) Is there an optimal timing between radiotherapy and surgery to reduce wound complications in metastatic spine disease? A systematic review. Eur Spine J 29:3080–3115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06478-5

Lee RS, Batke J, Weir L, Dea N, Fisher CG (2018) Timing of surgery and radiotherapy in the management of metastatic spine disease: expert opinion. J Spine Surg 4:368–373. https://doi.org/10.21037/jss.2018.05.05

Wang X, Yang JN, Li X, Tailor R, Vassilliev O, Brown P, Rhines L, Chang E (2013) Effect of spine hardware on small spinal stereotactic radiosurgery dosimetry. Phys Med Biol 58:6733–6747. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/58/19/6733

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA wrote the manuscript, MA, GR, KD, RP were chairs of the Recommendation Development Group, formulated recommendations, supervised voting, AK, DM, DK, GR, GL, GG, MH, JW, JP, ŁD, MA, MT, PT, RM, TŁ, ZR: literature search, formulation of recommendations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maciejczak, A., Gasik, R., Kotrych, D. et al. Spinal tumours: recommendations of the Polish Society of Spine Surgery, the Polish Society of Oncology, the Polish Society of Neurosurgeons, the Polish Society of Oncologic Surgery, the Polish Society of Oncologic Radiotherapy, and the Polish Society of Orthopaedics and Traumatology. Eur Spine J 32, 1300–1325 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07546-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07546-2