Abstract

The mechanosensory lateral line of fishes is a flow sensing system and supports a number of behaviors, e.g. prey detection, schooling or position holding in water currents. Differences in the neuromast pattern of this sensory system reflect adaptation to divergent ecological constraints. The threespine stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus, is known for its ecological plasticity resulting in three major ecotypes, a marine type, a migrating anadromous type and a resident freshwater type. We provide the first comparative study of the pattern of the head lateral line system of North Sea populations representing these three ecotypes including a brackish spawning population. We found no distinct difference in the pattern of the head lateral line system between the three ecotypes but significant differences in neuromast numbers. The anadromous and the brackish populations had distinctly less neuromasts than their freshwater and marine conspecifics. This difference in neuromast number between marine and anadromous threespine stickleback points to differences in swimming behavior. We also found sexual dimorphism in neuromast number with males having more neuromasts than females in the anadromous, brackish and the freshwater populations. But no such dimorphism occurred in the marine population. Our results suggest that the head lateral line of the three ecotypes is under divergent hydrodynamic constraints. Additionally, sexual dimorphism points to divergent niche partitioning of males and females in the anadromous and freshwater but not in the marine populations. Our findings imply careful sampling as an important prerequisite to discern especially between anadromous and marine threespine sticklebacks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fish populations dwelling in habitats characterized by divergent hydrodynamic conditions are faced with different demands of the mechanosensory lateral line, a bilateral flow sensing system which responds to even very weak water movements (Kasumyan 2003; van Netten and McHenry 2013; McHenry and Liao 2013; Herzog et al. 2017). This sensory system is crucial for a number of behaviors, such as prey detection, schooling, position holding in water currents or predator avoidance and is, therefore, fundamental for individual fitness (Coombs and van Netten 2006; Bleckmann and Zelick 2009; van Netten and McHenry 2013; Schmitz et al. 2014).

The end organs and functional units of the lateral line system (LLS) are the neuromasts which are capable to detect mechanical stimuli caused by water movements (Dijkgraaf 1963; van Netten and McHenry 2013; Herzog et al. 2017). In teleost fishes, neuromasts are either enclosed in fluid-filled canals (canal neuromasts, CNs) or free standing on the surface of the body (superficial neuromasts, SNs), with the latter sometimes lowered in shallow pits and grooves (Webb, 2014). These two general neuromast types are sensitive to different hydrodynamic stimuli. While CNs respond to flow acceleration SNs are velocity sensitive (van Netten and McHenry 2013; Schmitz et al. 2014).

Gasterosteus aculeatus Linnaeus 1758, the threespine stickleback, is a small active swimming teleost fish which inhabits various ecosystems: from morphologically uniform habitats like the open water of oceans and large lakes to highly structured ones like rivers and brooks (Wootton 1984; Bell and Foster 1994). Characterized by a high phenotypic and ecotypic plasticity, it is, therefore, an excellent example of intraspecific segregation (summarized in Wootton 2009). The three major ecotypes which are discerned, marine, anadromous and freshwater, are adapted to divergent environments differing in hydrodynamic conditions and are characterized by distinct swimming modes (Wootton 2009; Bell and Foster 1994; Bell et al. 2004; Wund et al. 2012). As the freshwater ecotype evolved from the anadromous type (Schluter and Conte 2009), the marine type is ancestral to the anadromous ecotype (Dodson et al. 2009). Despite long-lasting research on threespine stickleback radiation (Raeymaekers et al. 2005; Spoljaric and Reimchen 2011; Leinonen et al. 2011; Aguirre and Bell 2012; Svanbäck and Schluter 2012; Wund et al. 2012; Vila et al. 2017) virtually nothing is known about the behavior and the habitat of the marine type (Demchuk et al. 2015; Ivanova et al. 2016; Ahnelt 2018; Lajus et al. 2019; Rind et al. 2020). However, knowledge of the ancestral form, its intraspecific variability and polymorphism, provides insight into radiation patterns, and thus might help explaining why the same phenotypes have evolved repeatedly under similar environmental constraints (Schluter 1996; Walker and Bell 2000; Pfennig et al. 2010).

There are only few studies which described intraspecific diversity of the lateral line system of fishes (e.g. Jollie 1975; Ahnelt and Göschl 2003; Fischer et al. 2013). But recently, this phenomenon has received more attention, especially concerning gasterosteid fishes (Wark and Peichel 2010; Jiang et al. 2015; Trokovic et al. 2011; Planidin and Reimchen 2019). These authors found that the LLS of the threespine stickleback varies in the number of its neuromasts among populations (Wark and Peichel 2010) and among sexes (Planidin and Reimchen 2019) and suggest that these numerical differences are the results of environmental constraints.

In this study, we investigated differentiation of the head LLS of G. aculeatus populations concerning the three general ecotypes, a strictly marine ecotype that spends the entire life cycle in the sea, an anadromous ecotype that migrates from the sea into freshwaters to spawn and returns as juveniles to the sea, and a freshwater ecotype that spends its entire life cycle in freshwater. We were interested if and to which extent the head LLS of these general ecotypes, varied related to their divergent ecology and habitat. Although virtually nothing is known about the life-style and the habitat of the marine threespine stickleback, we predicted that the population of marine sticklebacks differs in the number of superficial neuromasts from the population of the anadromous sticklebacks. We also tested for sexual dimorphism in the topography of this sensory system, because males and females of the freshwater type are spatially segregated in the wild at least in large water bodies (Aguirre and Akinpelu 2010; Cooper et al. 2011; Kitano et al. 2012). Additionally, we discuss differences in the pattern and the morphology of the LLS of east Pacific and east Atlantic (North Sea) sticklebacks.

Materials and methods

In this study, the head lateral line system of marine (marine spawning), anadromous (migrating from the sea into freshwater for spawning), resident freshwater and brackish (brackish water spawning) threespine sticklebacks from the North Sea (region) was investigated.

Sampling sites

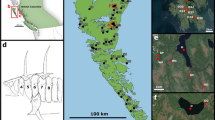

Threespine sticklebacks were sampled on four localities: (1) a strictly marine population in the German Wadden Sea (SPK), (2) an anadromous population (BKD), (3) a freshwater population (UPF) in upcountry Denmark and, additionally (4) a brackish water (euryhaline) population (RJF) (Fig. 1; Table 1). The marine population was sampled on a spawning site in a tidal creek in Königshafen, located in the Sylt-Rømø bight, at the Island of Sylt (Germany) with an annual mean salinity of 27.8 ‰. The anadromous population was sampled about 25 km upstream in Kisbæk, an inland creek of the Brede Å river system (Denmark). This river system discharges into the Sylt-Rømø bight and allows a barrier-free upstream migration. The freshwater population was sampled at Uge (Denmark) in a fishpond, constituting a groundwater fed former gravel pit with no surface afflux or efflux. The digging in the pit ended in the late 1980s. The fishpond measures approximately 5 ha and the maximal depth is 12 m. Because it originates from gravel dredging, it has a specific morphology with a short shallow shore and then a very steep slope. The coastal brackish water population was sampled on the island Rømø in the “put & take” fishpond north of Juvre (Denmark). This fishpond has a direct connection to the Wadden Sea, thus the salinity ranges between 13 and 20 ‰ depending on the tides and allows an unhindered migration of sticklebacks.

Fish sampling

Fish were sampled between March and May 2011 using dip nets (water depth 0.1–0.6 m) and seines (water depth up to 1.2 m). A total of 231 (116 males and 115 females) specimens were analyzed from the 4 populations (Table 1). Fish were euthanized with clove oil (one drop in one liter water) and further preserved in 4% formaldehyde. After 4 days and by passing an alcohol series the fish were transferred to 70% ethanol. Sex was determined by visual inspection of the gonads through laterally opening the abdomen.

Lateral line groove and neuromast analyses

The topography of the LLS was assessed on both sides of the head using a binocular microscope. Transparency of the mucus of the skin was ensured by initial preservation in formaldehyde. All neuromasts were large, of similar size and well visible under oblique lightning.

Gasterosteus aculeatus lacks lateral line canals and also canal neuromasts (Honkanen 1993; Wark and Peichel 2010). Consequently, the head lateral line is formed by superficial neuromasts only (Wark and Peichel 2010). These authors described in detail the pattern of these neuromasts for sticklebacks of the east Pacific region. Their arrangement and in part their position on the head of these populations differed from the North Sea sticklebacks of this study. Therefore, our nomenclature of the head LLS differs partly from the nomenclature used by Wark and Peichel (2010) (see below).

Lateral line grooves

In generalized teleost fishes, the head lateral line canal system is formed by seven canals, the (1) supraorbital, (2) infraorbital, (3) otic, (4) postotic, (5) supratemporal, (6) mandibular and (7) preopercular canals (Webb 1989; Adriaens et al. 1997). In many teleosts, these canals are interconnected with each other forming a more or less closed system (Jollie 1975; Webb 1989). Reduction of these bony canals enclosing the epithelial lateral line canal is not always complete and often resulting in bony grooves (e.g. Marshall 1986; Webb 2014). Therefore, lateral line grooves are interpreted as incompletely developed (bony) lateral line canals (Webb 1989, 2014). These grooves may either carry the epithelial lateral line canal like many gobioid fishes (e.g., Marshall 1986; Ahnelt and Duchkowitsch 2004), or superficial neuromasts sit on their floor (Marshall 1986; Ahnelt and Bohacek 2004).

The lateral line grooves of the North Sea threespine stickleback occur in the position of the seven lateral line canals but are generally not interconnected (e.g. the mandibular and the preopercular canals of G. aculeatus are distinctly separated from each other) (Figs. 2, 3). A tentative remnant of a former lateral line canal is the anterodorsal groove. This groove extends posteriorly to the supraorbital groove and—often although not regularly—joins its counterpart in the dorsal midline (Fig. 2). In many cypriniforms, the supraorbital canal extends posteriorly to the junction of the infraorbital and otic canals for a short distance (e.g. Northcutt et al. 2000; Ito et al. 2017) or is even reaching far behind on the head to the transversal supratemporal canal on the rear of the occipital region (e.g. Hensel, 1975; Bogutskaya, 1988). If short, a more or less long row of neuromasts extends caudally [termed e.g. ‘anterior head lines of pits’ (Pehrson 1922), ‘anterior pit line’ (Jollie 1975), ‘accessory pit line’ (Northcutt et al. 2000), ‘postotic group’ (Nakae et al. 2013) or dorsolateral series (Becker et al. 2016)]. As there is no consistent nomenclature for these neuromasts and to facilitate comparison, we stay with the term AP (anterior pit) introduced by Wark and Peichel (2010) for this neuromast unit of the threespine stickleback.

Schematic drawing of the lateral line grooves and pits in dorsal (a) and lateral (b) views. APG anterior pit groove, ETP ethmoidal pit, IOG infraorbital groove, MEP mental pit, MDG mandibular groove, ORP oral pit, OTG otic groove, POG postotic groove, PRG1 Vertical preopercular groove, PRG2 horizontal preopercular groove, PTG posttemporal groove, SOG supraorbital groove; STG supratemporal groove. The arrow indicates the separation of the two preopercular grooves (PRG1 and PRG2)

Pattern of the lateral line grooves and pits of a representative threespine stickleback from the Brede Å river system (BKD), lateral view. APG anterior pit groove, ETP ethmoidal pit, IOG infraorbital groove, MEP mental pit, MDG mandibular groove, ORP oral pit, OTG otic groove, POG postotic groove, PRG1 vertical preopercular groove, PRG2 horizontal preopercular groove PTG posttemporal groove, SOG supraorbital groove, STG supratemporal groove. Scale = 2 mm

We found no specimen without grooves or with a particular groove missing, although parts of grooves were reduced in some individuals. No neuromasts occurred in the course of these missing parts. To avoid a bias in neuromast numbers, we did not consider specimens with such reduced canal sections.

Lateral line neuromasts

The most conspicuous difference between the east Pacific and the east Atlantic (North Sea) threespine sticklebacks were lateral line grooves developed in the latter (see below) but absent in the former. As a result, the majority of superficial neuromasts sitting on the surface of the head in the east Pacific sticklebacks were lowered in grooves in the North Sea sticklebacks. Although in the threespine sticklebacks of our study, the neuromasts are not standing free on the head surface (‘superficial’) but are lowered in pits and grooves we stay with the term ‘superficial neuromasts’ of Wark and Peichel (2010). In many studies on the LLS of fishes, ‘superficial neuromast’ is used for neuromasts not enclosed in canals (‘canal neuromast’) (e.g., Kasumyan 2003; van Netten and McHenry 2013; Schmitz et al. 2014; Webb et al. 2014; Herzog et al. 2017). Nevertheless, it should be considered that canal neuromasts are not always enclosed in canals but are standing ‘superficial’ (Ahnelt and Bohacek 2004; Figs. 1, 2, 3; Ahnelt et al. 2004; Fig. 3).

Wark and Peichel (2010) distinguished nine neuromast rows on the head of the Pacific sticklebacks (ethmoidal, supraorbital, otic, supratemporal, anterior pit, infraorbital, mandibular, oral and preopercular). In this study, we discern 13 neuromast rows. We use the following nomenclature for these 13 units (differences to Wark and Peichel in bold): (1) ethmoidal (ET), (2) supraorbital (SO), (3) anterior pit (AP), (4) otic (OT), (5) postotic (PO), (6) supratemporal (ST), (7) posttemporal (PT), (8) infraorbital (IO), (9) mandibular (MD), (10) oral, (11–12) preopercular (PR1 and PR2) and (13) mental (ME).

Wark and Peichel (2010) united the neuromast rows on the lower jaw and on the ventral (horizontal) arm of the preopercle to a single row (‘mandibular’). We define the MD row as restricted to the lower jaw (mandible) as this row of neuromasts is distinctly separated from those on the preopercle in all investigated specimens. Additional to MD, we also found neuromasts ventrally on the symphysis (‘chin’) (ME) of the lower jaw, so far not reported from Pacific threespine sticklebacks. We address these neuromasts as a distinct unit, because these ‘chin’ neuromasts develop independently from the mandibular canal and its canal neuromasts in teleost fishes (Webb and Shirey 2003). We separated the neuromasts on the preopercle in two units, PR1 on the vertical and PR2 on the horizontal part of the reverse L-shaped preopercle by functional means, because neuromasts arranged in longitudinal and transversal rows respond to different water currents (Coombs et al. 1988). By the same reason, we differentiated between the longitudinal PO and the transversal ST rows which, together with the PT row were united to a single ST-unit by Wark and Peichel (2010). Although per definition the PT neuromasts are part of the trunk LLS, we included them into the array of head neuromasts but as a distinct unit (see below).

The general topography (pattern) of the head LLS is very similar among the investigated populations. Based on their arrangement, we identified 13 (12 + 1) neuromast units arranged in ten (9 + 1) distinct grooves and three units standing in pits on the surface of the head. ‘ + 1′ refers to the posttemporal groove and neuromasts, respectively (Fig. 4). As the posttemporal bone is part of the pectoral girdle, these neuromasts are per definition trunk neuromasts. Nevertheless, the posttemporal bone links the shoulder girdle of teleost fishes tightly to the occipital region of the skull. This close proximity to the postotic part of the head LLS functionally ties the neuromasts of the posttemporal to the head canal system. Therefore, these neuromasts (or canal in many teleosts) are often included in the mechano-sensory head LLS like e.g. in gobiid fishes (as posterior oculoscapular canal e.g., Akihito 1986; Miller 1986). In the investigated threespine sticklebacks, the posttemporal bone forms a short longitudinal groove which carries a row of neuromasts. This is contrary to the typical trunk lateral line of this fish which generally consists of small groups of pits on the bony lateral plates (Wark and Peichel 2010; Planidin and Reimchen 2019), or, if the plates are missing, of single neuromasts free standing on the skin (Wark and Peichel 2010). Nevertheless, it has to be noted that the separation of PO, PT and ST is just functional. These neuromasts are innervated by the ramus supratemporalis of the posterior lateral line nerve (Ahnelt and Bohacek 2004; Asaoka et al. 2011; Sato et al. 2019) which innervates the neuromasts on the trunk, the tail and the caudal fin (Asaoka et al. 2011; Ishida et al. 2015; Sato et al. 2019).

Lateral line grooves and superficial neuromasts of the postorbital region, lateral view. APG anterior pit groove, OTG otic groove, POG postotic groove, PRG1 vertical preopercular groove, PTG posttemporal groove, SOG supraorbital groove, STG supratemporal groove. White asterisks = first, 5th and last otic neuromasts; white vertical arrows = first and last postotic neuromast; vertical grey arrows = first and last posttemporal neuromast; black, short horizontal first, 4th and 7th preopercular neuromasts; black, long horizontal arrows = two last supraorbital neuromasts. Note that the neuromasts sit in pits on the floor of the canals, best visible in OTG, POG and SOG. a = anterior. Scale = 2 mm

The 13 neuromast units are generally formed by rows of consecutively arranged neuromasts except for ET on the snout (ethmoidal region) where neuromasts are arranged in a more irregular pattern (Fig. 2). The following three units are not arranged in grooves but sit in pits: ET on the snout, ME on the symphysis of the lower jaws and OR on the cheek ventral to the eyes and posterior to the angle of the mouth. The following ten units are arranged in grooves: SO and IO around the orbit, OT, PO and ST posterior to the orbit, AD dorsal on the head, PR on the reverse L-shaped preopercle divided in a vertical (PR1) and a horizontal (PR2) part, MD on the lower jaw and PT on the posttemporal bone. No double rows or aggregations (patches) of neuromasts were found on the head.

Statistical analysis

General linear models were used to test for differences in average neuromast numbers as a result of population, sex and their interaction, separately for each neuromast row. Pair-wise comparisons were realized via t tests. A p value of 0.05 or smaller was regarded as statistically significant. Corrections for multiple pairwise tests are specified in the text where applicable. All analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics 26. Also, the graphics were created in IBM SPSS Statistics 26.

Results

To assess the topography of the head LLS, we investigated four populations of the threespine stickleback from the North Sea representing the three general ecotypes, i.e. strictly marine, spending its entire life cycle in the sea (Sylt Königshafen (SPK)), anadromous, hatching in fresh water, migrating to the sea and returning to freshwater for spawning (Brede Å (BKD)) and resident freshwater (Uge (UPF)). Additionally, we included a fourth, euryhaline, population which spawns in brackish water (Rømø Juvre (RJF)). The marine and the anadromous population occur partly sympatric in a semi-enclosed bay of the North Sea, the Sylt-Rømø bight (Fig. 1).

General topography of the head lateral line system

Lateral line canals and canal neuromasts were lacking in all investigated specimens. Instead, bony grooves run in the course of the typically lateral line canals of teleost fishes. Consequently the head LLS of all investigated specimens were exclusively formed by superficial neuromasts. These neuromasts can be grouped in two general categories: (1) neuromasts running in bony grooves and (2) neuromasts single standing each lowered in a pit (Figs. 3, 4). Also within the grooves the neuromasts are lowered in pits, generally single but sometimes as short rows mostly of two to four neuromasts. These pits are roundish and formed by bone or by soft tissue.

The topography (pattern) of the head LLS is very similar among the investigated populations. Based on their arrangement we identified 13 neuromast rows (units). From these units, ten are lowered in grooves. The remaining three form a series of pits. We found no divergence between the populations and no sexual dimorphism in this general pattern of the head LLS. More specifically, neuromasts were identified in all individuals in 10 of the 13 units. For the supratemporal groove (STG), no neuromasts could be identified in 1 male specimen from the anadromous population (BKD) out of 26 specimens of the same population and sex. With regard to the mandibular groove (MDG), it was 1 male RJF (brackish water) individual out of 31 same-sex, same-population specimens, where no neuromasts were scored. The mental pit (MEP) showed the largest number of individuals that lack neuromasts in a unit. These individuals where distributed across both sexes and three of the four studied populations (percentages range between 16 and 57% across groups per sex and population). Only individuals from anadromous population (BKD) were never found to lack neuromasts in that pit.

Head lateral line grooves

We identified ten grooves carrying neuromasts on the head: the supra- and the infraorbital grooves (SOG, IOG) around the orbit, the otic, the postotic and the supratemporal grooves (OTG, POG, STG) posterior to the orbit, the anterior pit groove (APG) dorsal on the head, the preopercular groove (PRG, subdivided in the vertical PR1G and the horizontal PR2G, on the reverse L-shaped preopercle) and the mandibular groove (MDG) on the lower jaw (Fig. 3). The posttemporal groove (PTG) extended immediately posterior, and more or less in elongation of the postotic groove. The following 12 bones carry the 10 lateral line grooves: nasal and frontal bones (SOG), infraorbital bones 1–3 (IOG), sphenotic and pterotic bones (OTG), pterotic bone (POG), pterotic and epiotic bones (STG), frontal and supraoccipital bones (APG), preopercular bone (PRG1 + PRG2), dentary and angulo-articular bones (MDG) and posttemporal bone (PTG) (Fig. 2a, b).

All grooves were paired and developed left and right on the respective part of the head. They were distinctly separated from their counterparts except for the APG which formed a V opening anteriorly (Fig. 2). The majority of these grooves generally extended longitudinally. Only the STG and the vertical PRG1 extended transversally and vertically, respectively. We found no specimen without grooves or with a particular groove missing, although parts of grooves were reduced in some individuals. No neuromasts occurred in the course of these missing parts.

Head lateral line neuromast rows (Figs. 3, 4, 5)

Lateral line grooves and superficial neuromasts on the lower jaw, ventro-lateral view. MD, mandibular row of superficial neuromasts; MDG, mandibular grove; ME, mental neuromasts. Long black arrows = first and last mandibular neuromast; short black arrows = left and right mental neuromast. a = anterior. Scale = 1 mm

The superficial neuromasts were arranged in 13 single rows formed by consecutively arranged neuromasts. No double rows or aggregations (patches) of neuromasts were found. According to their arrangement in the lateral line grooves, these neuromasts were grouped in the following rows: the supra- and the infraorbital rows (SO and IO) around the orbit, the otic, postotic and supratemporal rows (OT, PO and ST) posterior to the orbit, the anterior dorsal row (AD) dorsal on the head, the mandibular row (MD) on the ventral side of the lower jaw, the preopercular row (PR) on the preopercle, divided in a vertical (PR1) and a horizontal (PR2) part and the posttemporal row (PT) on the posttemporal bone. The free-standing SNs were grouped in: the ethmoidal neuromasts (ET) on the snout, the mental neuromasts (ME) on the symphysis (‘chin’) of the lower jaws and the oral row (OR) on the cheek, posterior to the angle of the mouth.

Mental superficial neuromast unit

The mental (ME) neuromast unit on the symphysis ventral on lower jaws generally consists of two neuromasts, one on each side (Fig. 5). Just five specimens had on one or on both sides the number increased to two neuromasts, i.e. three or four in total.

ME neuromasts were found in all populations but not on all specimens and to a varying percentage (Table 2). Only in the anadromous population (BKD), all specimens had these SNs developed, at least on one side. In the remaining three populations, a varying number of these neuromasts was missing completely or on one side, respectively: SPK 44.8%, RJF 32.8%, BKD 7.3% and UPF 67.2% (Table 2).

ME neuromasts occurred close to the ventral midline of the head and not in elongation of the MDGs. Because this suggests an independent origin from the MD neuromasts, we address them as a distinct neuromast unit. If a second neuromast was developed left or right, these were aligned longitudinally. Possibly, these single neuromasts are the remnants of a former neuromast row.

Intrapopulation variation in neuromast number

The individual variation in the total number of SNs was relatively similar in all populations. The lowest and the highest number of SNs in each population differed between ~ 110 and 130 (Table 3). There was no size related variation in SN number. In all populations, some smaller specimens showed a higher total number of SNs than larger specimens.

Interpopulation variation in neuromast number

The four populations differed significantly in the total number of SNs (F = 57.5, p < 0.001, Table 4). The highest number was found in the resident freshwater (still water) population (UPF), while the lowest—and very similar in numbers (p = 1.000)—occurred in the both migrating populations (anadromous BKD and brackish RJF). The strictly marine population (SPK) had a significantly higher mean number of SNs than the two migrating populations (ps ≤ 0.001) but less than the still water population (p < 0.001). Descriptive statistics are given in Table 3. Mean differences between populations are given in Table 5. All the reported p values in the pairwise comparisons are Bonferroni adjusted.

The subsequent population breakdown by neuromast row (Figs. 7, 8) refines the picture. Table 4 shows that the corresponding uncorrected p values range between 0.013 and 1.8E − 32. With Bonferroni correction for 13 neuromast rows, 1 neuromast row (PO) was only a trend (p = 0.169), but the others remained significant at a 0.05 level. Pairwise post hoc tests, with Bonferroni correction within neuromast row (Table 5), showed that the marine SPK population has consistently less neuromasts per neuromast rows than the freshwater population UPF (Table 5). An exception from this common pattern was the neuromast row ME (more neuromasts in SPK). The marine SPK did not significantly differ from the brackish RJF population in the number of neuromasts in the anterior neuromast rows (IO, MD, ME, OR, OT) and AP (ps > 0.05), but had a generally higher number of neuromasts in the neuromast rows ET, PR1, PR2, PT, SO and ST (ps ≤ 0.05). All mean differences are given and flagged for Bonferroni-adjusted significance in Table 5. Compared with the anadromous BKD, SPK had on average more neuromasts in the following rows: AP, ET, IO, PR1, PR2, PT, SO, ST (ps ≤ 0.05). The differences did not reach statistical significance in the other rows. Only the ME row showed a different number with lower neuromast counts in SPK than in BKD (p ≤ 0.05).

The two migrating populations did not differ significantly in their neuromast counts, except for the two rows IO and ME (Table 5). For IO, RJF had a higher average number of neuromasts than BKD, whereas for ME, it showed a significantly lower average count than BKD. The freshwater population UPF showed significantly more neuromasts for all neuromast rows as compared to the two migrating populations RJF and BKD (Table 5; Figs. 6, 7, 8), with the exception of ME (Tables 2 and 5). Here, BKD showed the highest average count. Standard deviations per neuromast row, population and sex are depicted in Fig. 7.

Sexual dimorphism in the total number of neuromasts in four populations of North Sea threespine sticklebacks. There was no significant sexual dimorphism in the marine and the brackish water spawning populations, whereas males showed a larger total number of neuromasts in the anadromous and the freshwater populations. BKD anadromous population, RJF brackish water spawning population, SPK marine population, UPF freshwater population

Differences in average number of neuromast per neuromast row, population, and sex of North Sea threespine sticklebacks. The error bars depict plus and minus one standard deviation. The sample sizes range between 26 and 31 individuals of the same sex and population. Neuromast rows are listed alphabetically and spelled out in the material and method section. BKD anadromous population, RJF brackish water spawning population, SPK marine population, UPF freshwater population

Plotted means from Figure to ease cross-species comparisons along the ecologically and evolutionary meaningful gradient between marine and freshwater (from left to right). Measures of spread were omitted for better readability. Male averages are depicted in blue (o), female averages in red (△). Averages are connected with solid lines (for males) and dashed lines (for females)

Sexual dimorphism

The total number of head neuromasts varied significantly between the sexes in three of the four populations.

Sexual dimorphism in total numbers of SNs

We found no sexual dimorphism in the pattern of the head LLS in the studied populations. But we found sexual dimorphism in the number of SNs in three of the four populations, most distinct in the anadromous BKD (t = 4.331, p < 0.001), but missing in the marine SPK (t = 0.280, p = 0.781), Fig. 6. A significant difference between the sexes also occurred in the freshwater UPF (t = 3.120, p = 0.003), and a trend was observed in the brackish RJF (t = 1.524, p = 0.134), Fig. 6. The variance in neuromast number was similar in males and females for SPK (Levene F = 0.589, p = 0.446), BKD (F = 0.775, p = 0.383) and UPF (F = 0.003, p = 0.954), but differed in RJF (F = 7.354; p = 0.009). In this population, the variance in females was distinctly higher than in males (Fig. 7).

Sexual dimorphism in specific SNs rows

There was a significant main effect of sex in most neuromast rows (Figs. 7, 8). Males had a higher number of neuromasts. In 4 of the 13 rows, there was no significant main effect of sex (uncorrected p values > 0.05). These four rows were AP, ET (yet a trend in the same direction), ME and SO (Table 4). With a Bonferroni correction for 13 neuromast rows, the sexual dimorphism remained significant at a 0.05 level in 6 of the rows (IO, MD, OR, OT, PO, PT) and a trend (p ≤ 0.1) for ST. There was a significant interaction between population and sex in IO (F = 4.844, uncorrected p = 0.003), OR (F = 6.250, p < 0.001), OT (F = 2.963, p = 0.033; n.s. after Bonferroni correction for 13 neuromast rows), PR1 (F = 5.317, p = 0.001), and PR2 (F = 5.089, p = 0.002). Test statistics for all neuromast rows are given in Table 4. For IO, three populations showed a significant sexual dimorphism with males having on average 4.9–8.6 neuromasts more (all ps ≤ 0.004), but not the marine SPK (t = 0.244, p = 0.808). Also for OR, the marine SPK was the only population without a difference between males and females in the neuromast count (t = − 0.083, p = 0.934), whereas the other three populations had a male average count that was on average 3.2–4.2 neuromasts higher than the female count of the same population (BKD: t = 5.049, p < 0.001; RJF: t = 5.389, p < 0.001; UPF: t = 4.322, p < 0.001). In the OT row, the higher male count as compared to the females of the same population reached statistical significance only for BKD and UPF (ps < 0.001), but not for RJF (t = 1.001, p = 0.321). In SPK, it was marginally significant (t = 1.887, p = 0.064). The interaction effect in the row PR1 and PR2 was mainly the result of a pronounced sexual dimorphism in the BKD population (t = 5.031, p = 0.001 and t = 3.427, p = 0.001). BKD males had on average five additional neuromasts in these rows than BKD females. Figures 7 and 8 show that the female counts here were exceptionally low. In the other populations, there was no significant sexual dimorphism in the PR1 (RJF: t = 0.257, p = 0.798, UPF: t = 0.801, p = 0.426) and PR2 rows (RJF: t = − 0.995, p = 0.324, SPK: t = − 0.529, p = 0.599). There was a trend for a smaller count in male SPK in PR1 (t = − 1.795, p = 0.078), and for a higher male (on average + 2.4 neuromasts) than female count in UPF for PR2 (t = 1.730, p = 0.089, Fig. 8).

Discussion

In this study, the head lateral line system of marine (marine spawning), anadromous (migrating from the sea into freshwater for spawning), resident freshwater and, additionally brackish (brackish water spawning) threespine sticklebacks from the North Sea (region) was investigated. We found distinct differences in the head LLS between the populations representing the three general ecotypes (marine, anadromous and freshwater) and also between the sexes. Anadromous threespine sticklebacks had significantly more neuromasts developed than resident (freshwater) ones, and in all populations, the males had a higher neuromast count than the females except for the marine population. North Sea threespine sticklebacks also differed distinctly in the LLS from east Pacific sticklebacks. The North Sea populations had a second neuromast unit (ME) at lower jaws developed (missing in east Pacific populations) and the neuromasts were lowered in bony grooves or in pits (no grooves and pits were developed in east Pacific populations) (Wark and Peichel 2010).

Threespine sticklebacks are ecologically and morphologically diverse (Bell and Foster 1994; Wootton 2009) which results in different swimming behavior of e.g., streamlined migrating (sustained and prolonged swimming) and of deep-bodied resident populations (burst swimming, maneuverability) (Walker 1997). The swimming behavior of the strictly marine threespine sticklebacks is not known. The pattern of the LLS of teleost fishes is closely linked to the hydrodynamic conditions of the environment or to a specific style of locomotion (Engelmann et al. 2000; Schmitz et al. 2008; Webb 2014). Therefore, slow moving still water species or sedentary species often have a very high number of superficial neuromasts and a reduced lateral line canal system. E.g., the slow swimming goldfish Carassius auratus has about 1000 superficial neuromasts (Puzdrowski 1989) and the benthic American shadow goby Quietula guaymasiae about 1400 superficial neuromasts (Ahnelt and Göschl 2003) on the head. Contrary to this, fishes living in running waters or which are steadily swimming have generally a well developed lateral line canal system and relatively few superficial neuromasts, e.g. the rainbow trout (Dijkgraaf 1963; Jakubovsky 1967; Engelmann et al. 2002). This is based on the different response of canal neuromasts and superficial neuromasts to water currents (Vischer 1990; Schmitz et al. 2008; Kelley et al. 2017). Superficial neuromasts detect weak water movements (high frequency stimuli) in slow flow environments, whereas canal neuromasts detect high-frequency stimuli in environments with background noise (e.g., stimuli by turbulent water flow) (Engelmann et al. 2000; McHenry et al. 2008; Webb 2014).

Although G. aculeatus has no head lateral line canal system, some populations have remnants of it, bony grooves. Such grooves have been described for a Japanese stickleback population (Wark and Peichel 2010) and were also found in the North Sea populations of this study but were absent in east Pacific populations (Wark and Peichel 2010). Possibly, these differences are the result of divergent migration behavior. Wark and Peichel (2010) state that the east Pacific threespine sticklebacks are “…fairly slow swimming…” and “…live in characteristically slow-flow habitats”. Nevertheless, the anadromous threespine stickleback is generally a good and steady swimmer (Taylor and McPhail 1986) and able to overcome substantial distances (Quinn and Light 1989). Schools of Atlantic sticklebacks were found more than 200 km offshore and in a depth of 300 m (Jones and John 1978; Cowen et al. 1991). Additionally, adults migrate to their spawning grounds in fresh water (Wootton 1984, 2009), e.g., the anadromous threespine sticklebacks of this study were collected 25 km upstream of the river mouth. But to our knowledge, no such offshore records have been reported for east Pacific populations.

The freshwater ecotype of the threespine stickleback generally shows a resident behavior (Wootton 1984, 2009; Bell and Foster 1994). The relatively high number of neuromasts in the pond population of this study matches a LLS suited for still water and is in accordance with the results of Wark and Peichel (2010). Nevertheless, although the investigated freshwater population inhabits a stagnant water body, all lateral line grooves were developed. The origin of this population is not known but as many specimens still have rows of lateral plates from the head to the base of the caudal fin we assume an oceanic founder population.

Inter- and intrapopulation differences of the LLS of the threespine stickleback populations suggest an adaptation to different habitats and swimming modes. In a series of detailed studies, Cathrine Peichel and collaborators showed that habitat use of the threespine stickleback resulted in high interpopulation divergence in the LLS, namely in the number of neuromasts (Wark and Peichel 2010; Wark et al. 2011; Voje et al. 2013; Mills et al. 2014; Jiang et al. 2015, 2017). The steady and prolonged swimming threespine sticklebacks had less neuromasts than more resident and slow-swimming conspecifics. This is in accordance with our results. But the neuromast count of the marine population was significantly higher than in the anadromous and brackish water populations. Although the life-style of the strictly marine threespine stickleback is not known (Ahnelt 2018), the divergence in neuromast number suggests different swimming behavior compared to migrating conspecifics. The significantly lower number of neuromasts and the less distinct grooves indicate segregation in habitat use and swimming behavior between the marine and anadromous populations. Possibly, marine threespine sticklebacks stay close to the shore and undertake less long migrations. As a higher number of SNs increases, the sensitivity of the LLS and aid in detecting stimuli caused by water currents, we hypothesize that the marine population is more resident than the anadromous one.

The present study is the first to demonstrate sexual dimorphism of the head lateral line system of G. aculeatus. In three of the four populations, males had distinctly more neuromasts than females. This is an indication that, at least partly, habitat-specific differences are responsible for differences in the number of head neuromasts in the two migrating and in the freshwater population. This is supported by the fact that sexual dimorphism in body shape in anadromous and freshwater G. aculeatus is also the result of habitat specific segregation of sexes (e.g. Kitano et al. 2007; Aguirre et al. 2008; McGee and Wainwright 2013; Morris et al. 2018; Spoljaric and Reimchen 2011). This sexual dimorphism was explained by intraspecific competition resulting in streamlined pelagic females and deep-bodied benthic males in large freshwater bodies (Reimchen 1980; Walker 1997; Reimchen and Nosil 2001; Leinonen et al. 2011), because females exploit the open water feeding on zooplankton and males, which build and guard nests, preferably exploit the benthic niche (Reimchen and Nosil 2001). Such spatial niche differences between the two sexes should therefore also result in sexual dimorphism of the LLS. Actually, this was the case in the two migrating and in the freshwater population. But such sexual dimorphism in neuromast number did not occur in the marine population. We, therefore, assume that the sexes of the marine population are spatially not segregated.

These differences between the marine and the anadromous populations (higher total number of SNs and absence of sexual dimorphism in this trait in marine threespine sticklebacks) are a strong indication of segregation in habitat use and/or migrating behavior between individuals of these two populations of the North Sea threespine stickleback. Especially, this is because seemingly the number of neuromasts is genetically controlled (Wark et al. 2012; Archambeault et al. 2020).

Our results support the hypothesis that the number of superficial neuromasts is relatively low in threespine sticklebacks that migrate, that inhabit structurally open habitats and that have to deal with water flow. These findings on the LLS suggest segregation in habitat use and migrating behavior of the populations of the North Sea threespine stickleback as these ecotypes seemingly translate to distinct morphotypes. Therefore, our results are further proof to be careful at sampling as threespine sticklebacks are not threespine sticklebacks.

References

Adriaens D, Varraes W, Taverne L (1997) The cranial lateral-line system in Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822) (Siluroidei: Clariidae): morphology and development of canal related bones. European J Morphol 35:181–208

Aguirre WE, Akinpelu O (2010) Sexual dimorphism of head morphology in three-spined stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus. J Fish Biol 77:802–821. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02705.x

Aguirre WE, Bell MA (2012) Twenty years of body shape evolution in a threespine stickleback population adapting to a lake environment. Biol J Linn Soci 105:817–831. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.2011.01825.x

Ahnelt H (2018) Imprecise naming: the anadromous and the sea spawning threespine stickleback should be discriminated by names. Biologia 73:389–392. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11756-018-0038-1

Ahnelt H, Bohacek V (2004) The lateral line system of two sympatric eastern Pacific gobiid fishes of the genus Lythrypnus (Teleostei: Gobiidae). Bull Mar Sci 74:31–51

Ahnelt H, Duchkowitsch M (2004) The postcranial skeleton of Proterorhinus marmoratus with remarks on the relationship of the genus Proterorhinus (Teleostei: Gobiidae). J Nat Hist 38:913–924. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022293021000047873

Ahnelt H, Göschl J (2003) Morphological differences between the eastern Pacific gobiid fishes Quietula guaymasiae and Quietula y-cauda (Teleostei: Gobiidae) with emphasis on the topography of the lateral line system. Cybium 27:185–197

Ahnelt H, Göschl J, Dawson MN, Jacobs DK (2004) Geographic variation in the lateral line canals of Eucyclogobius newberryi (Teleostei, Gobiidae) and its comparison with molecular phylogeography. Folia Zool 53:385–389

Akihito (1986) Some morphological characters considered to be important in gobiid phylogeny. In: Uyeno T, Arai R, Taniuchi T, Matsuura K (eds) Indo-pacific fish biology. Proc sec Int Conf Indo-Pacific Fishes, Ichthyol Soc Japan, Tokyo, pp 629–639

Archambeault SL, Bärtschi LR, Merminod AD, Peichel CL (2020) Adaptation via pleiotropy and linkage: association mapping reveals a complex genetic architecture within the stickleback Eda locus. Evol Lett 4(4):281–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev13.175

Asaoka R, Nakae M, Sasaki K (2011) Description and innervation of the lateral line system in two gobioids, Odontobutis obscura and Pterogobius elapoides (Teleostei: Perciformes). Ichthyol Res 58:51–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10228-010-0193-z

Becker EA, Bird NV, Webb JF (2016) Post-embryonic development of canal and superficial neuromasts and the generation of two cranial lateral line phenotypes. J Morphol 277:1273–1291. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.20574

Bell MA, Foster SA (eds) (1994) The evolutionary biology of the threespine stickleback. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 571

Bell MA, Aguirre WE, Buck NJ (2004) Twelve years of contemporary armor evolution in a threespine stickleback population. Evolution 58:814–824

Bleckmann H, Zelick R (2009) Lateral line system of fish. Integr Zool 4:13–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-4877.2008.00131.x

Bogutskaya NG (1988) Canal topography of the seismosensory system of cyprinids of the subfamily Leuciscinae, Zenocyprininae and Cultrinae. J Ichthyol 28:91–107

Coombs S, van Netten S (2006) The hydrodynamics and structural mechanisms of the lateral line system. In: Shadwick RE, Lauder GV (eds) Fish Biomechanics. Fish Physiology. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 103–140

Coombs S, Janssen J, Webb JF (1988) Diversity of lateral line systems: evolutionary and functional considerations. In: Atema J, Fay RR, Popper AN, Tovolga WN (eds) Sensory biology of aquatic animals. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 553–593

Cooper IA, Gilman TR, Boughman JW (2011) Sexual dimorphism and speciation on two ecological coins: patterns from nature and theoretical predictions. Evolution 65:2553–2571. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01332.x

Cowen RK, Chiarella LA, Gomez CJ, Bell MA (1991) Offshore distribution, size, age, and lateral plate variation of late larval/early juvenile sticklebacks (Gasterosteus) off the Atlantic coast of New Jersey and New York. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 48:1679–1684. https://doi.org/10.1139/f91-199

Demchuk A, Ivanov M, Ivanova T, Polyakova N, Mas-Martí E, Lajus D (2015) Feeding patterns in seagrass beds of three-spined stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus juveniles at different growth stages. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 95:1635–1643. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025415000569

Dijkgraaf S (1963) The functioning and the significance of the lateral line organs. Biol Rev 38:51–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1963.tb00654.x

Dodson JJ, Laroche J, Lecomte F (2009) Contrasting evolutionary pathways of anadromy in euteleostean fishes. Am Fish Soc Symp 69:63–77

Engelmann J, Hanke W, Mogdans J, Bleckmann H (2000) Hydrodynamic stimuli and the fish lateral line. Nature 408:51–52

Engelmann J, Hanke W, Bleckmann H (2002) Lateral line reception in still- and running water. J Comp Physiol 188:513–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00359-002-0326-6

Fischer EK, Soares D, Archer KR, Ghalambor CK, Hoke KL (2013) Genetically and environmentally mediated divergence in lateral line morphology in the Trinidadian guppy (Poecilia rticulata). J Exp Biol 216:3132–3142. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.081349

Hensel K (1975) Morphology of lateral-line canal system of the genera Abramis, Blicca and Vimba with regard to their ecology and systematic position. Acta Univ Carol Biol 12:105–153

Herzog H, Klein B, Ziegler A (2017) Form and function of the teleost lateral line revealed using three-dimensional imaging an computational fluid dynamics. J R Soc Interface 14:20160898

Honkanen T (1993) Comparative study of the lateral-line system of the three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) and the nine-spined stickleback (Pungitius pungitius). Acta Zool 74:331–336

Ishida Y, Asaoka R, Nakae M, Sasaki K (2015) The trunk lateral line system and its innervation in Mugil cephalus (Mugilidae: Mugiliformes). Ichthyol Res 62:253–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10228-014-0433-8

Ito T, Fukuda T, Morimune T, Hosoya K (2017) Evolution of the connection patterns of the cephalic lateral line canal system and its use to diagnose opsariichthyin cyprinid fishes (Teleostei, Cyprinidae). ZooKeys 718:115–131. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.718.13574

Ivanova TS, Ivanov MV, Golovin PV, Polyakova NV, Lajus DL (2016) The White Sea threespine stickleback population: spawning habitats, mortality, and abundance. Evol Ecol Res 17:301–315

Jakubovsky M (1967) Cutaneous sense organs of fishes. Part VII. The structure of the system of lateral-line organs in the Percidae. Acta Biol Cracov 10:69–81

Jiang Y, Torrance L, Peichel CL, Bolnick DI (2015) Differences in rheotactic responses contribute to divergent habitat use between parapatric lake and stream threespine stickleback. Evolution 69:2517–2524. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12740

Jiang Y, Peichel CE, Torrance L, Rizvi Z, Thompson S, Palivela VV, Pham H, Ling F, Bolnick DI (2017) Sensory trait variation contributes to biased dispersal of threespine stickleback in flowing water. J Evol Biol 30:681–695. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13035

Jollie M (1975) Development of the head skeleton and pectoral girdle in Esox. J Morph 147:61–88

Jones DH, John AWG (1978) A three-spined stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus L. from the North Atlantic. J Fish Biol 13:231–236

Kasumyan AO (2003) The lateral line in fishes: structure, function, and role in behavior. J Ichthyol 43(Suppl 2):S175–S213

Kelley JL, Grierson PF, Davies PM, Collin SP (2017) Water flows shape lateral line morphology in arid zone freshwater fish. Evol Ecol Res 18:411–428

Kitano J, Mori S, Peichel CL (2007) Sexual dimorphism in the external morphology of the threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus). Copeia 2007:336–349

Kitano J, Mori S, Peichel CL (2012) Reduction of sexual dimorphism in stream-resident forms of three-spined stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus. J Fish Biol 80:131–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2011.03161.x

Lajus DL, Golovin PV, Yurtseva AO, Ivanova TS, Dorgham AS, Ivanov MV (2019) Fluctuating asymmetry as an indicator of stress and fitness in stickleback: a review of the literature and examination of cranial structures. Evol Eco Res 20:83–106

Leinonen T, Cano JM, Merilä J (2011) Genetic basis of sexual dimorphism in the threespine stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus. Heredity 106:218–227. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2010.104

Marshall NJ (1986) Structure and general distribution of free neuromasts in the Black goby, Gobius niger. J Mar boil Ass UK 66:323–333

McGee MD, Wainwright PC (2013) Sexual dimorphism in the feeding kinematics of threespine stickleback. J Exp Biol 216:835–840. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.074948

McHenry MJ, Liao JC (2013) The hydrodynamics of flow stimuli. In: Coombs S, Bleckmann H, Fay R, Popper A (eds) The Lateral line system. Springer handbook of auditory research 48. Springer, New York, pp 73–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/2506-2013-13

McHenry MJ, Strother JA, van Netten SM (2008) Mechanical filtering by the boundary layer and fluid-structure interaction in the superficial neuromast of the fish lateral line system. J Comp Physiol A 194:795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00359-008-0350-2

Miller PJ (1986) Gobiidae. In: Whitehead PJP, Bauchot M-L, Hureau J-C, Nielsen J, Tortonese E (eds) Fishes of the northeastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean, vol III. UNESCO, Paris, pp 1019–1085

Mills MG, Greenwood AK, Peichel CL (2014) Pleiotropic effects of a single gene on skeletal development and sensory system patterning in sticklebacks. EvoDevo 5:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/2041-9139-5-5

Morris MR, Bowles E, Allen BE, Jamnicky HA, Rogers SM (2018) Contemporary ancestor? Adaptive divergence from standing genetic variation in Pacific marine threespine stickleback. BMC Evol Biol 18:113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1228-8

Nakae M, Shinohara G, Miki K, Abe M, Sasaki K (2013) Lateral line system in Scomberomorus niphonius (Telesotei, Perciformes, Scombridae): recognition of 12 groups of superficial neuromasts in a rapidly-swimming species and a comment on function of highly branched lateral line canals. Bull Natl Mus Nat Sci Ser A 39:39–49

Northcutt RG, Holmes PH, Albert JS (2000) Distribution and innervation of lateral line organs in the Channel catfish. J Comp Neurol 421:570–592

Pehrson T (1922) Some points in the cranial development of teleostomian fishes. Acta Zool 3:1–63

Pfennig DW, Wund MA, Snell-Rood EC, Cruickshank T, Schlichting CD, Moczek AP (2010) Phenotypic plasticity’s impacts on diversification and speciation. Trends Ecol Evol 25:459–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2010.05.006

Planidin NP, Reimchen TE (2019) Spatial, sexual and rapid temporal differentiation in neuromast expression on lateral plates of Haida Gwaii threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus). Can J Zool 97:988–996. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjz-2019-0005

Puzdrowski RL (1989) Peripheral distribution and central projections of the lateral-line nerves in Goldfish, Carassius auratus. Brain Behav Evol 34:121–131

Quinn TP, Light JT (1989) Occurrence of threespine sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus) in the open North Pacific Ocean; migration or drift? Can J Zool 67:2850–2852

Raeymaekers JAM, Maes GE, Audenaert E, Volckaert FAM (2005) Detecting Holocene divergence in the anadromous-freshwater three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) system. Mol Ecol 14:1001–1014. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02456.x

Reimchen TE (1980) Spine deficiency and polymorphism in a population of Gasterosteus aculeatus: an adaptation to predators? Can J Zool 58:1232–1244

Reimchen TE, Nosil P (2001) Lateral plate asymmetry, diet and parasitism in threespine stickleback. J Evol Biol 14:632–645. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00305.x

Rind K, Rodriguez-Barucg Q, Nicolas D, Cucchi P, Lignot J-H (2020) Morphological and physiological traits of Mediterranean sticklebacks living in Camargue wetland (Rhone river delta). J Fish Biol 97:51–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.14323

Sato M, Nakae M, Sasaki K (2019) Convergent evolution of the lateral line system in Apogonidae (Teleostei: Percomorpha) determined from innervation. J Morph 280:1026–1045. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.20998

Schluter D (1996) Ecological causes of adaptive radiation. Am Nat 148(Suppl):S40–S64

Schluter D, Conte GL (2009) Genetics and ecological speciation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106:9955–9962. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901264106

Schmitz A, Bleckmann H, Mogdans J (2008) Organization of the superficial neuromast system in goldfish, Carassius auratus. J Morphol 269:751–761. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.10621

Schmitz A, Bleckmann H, Mogdans J (2014) The lateral line receptor array of cyprinids from different habitats. J Morphol 275:357–370. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.20219

Spoljaric M, Reimchen T (2011) Habitat-specific trends in ontogeny of body shape in stickleback from coastal archipelago: potential for rapid shifts in colonizing populations. J Morphol 272:590–597. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.10939

Svanbäck R, Schluter D (2012) Niche specialization influences adaptive phenotypic plasticity in the threespine stickleback. Am Nat 180:50–59. https://doi.org/10.1086/666000

Taylor EB, McPhail JD (1986) Prolonged and burst swimming in anadromous and freshwater threespine stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus. Can J Zool 64:416–420

Trokovic N, Herczeg G, Scott McCairns RJ, Izza Ab Ghani N, Merilä J (2011) Intraspecific divergence in the lateral line system in the nine-spined stickleback (Pungitius pungitius). J Evol Biol 24:1546–1558. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02286.x

Van Netten SM, McHenry MJ (2013) The biophysics of the fish lateral line. In: Coombs S, Bleckmann H, Fay R, Popper A (eds) The lateral line system. Springer handbook of auditory research 48. Springer, New York, pp 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/2506_2013_14

Vila M, Hermida M, Fernández C, Perea S, Doadrio I, Amaro R, Miguel ES (2017) Phylogeography and conservation genetics of the Ibero-Balearic three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus). PLoS ONE 12:e0170685. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170685

Vischer HA (1990) The morphology of the lateral line system in 3 species of Pacific cottoid fishes occupying disparate habitats. Experientia 46:244–250

Voje KL, Mazzarella AB, Hansen TF, Østbye KT, Bass A, Herland A, Bærum KM, Gregersen F, Vøllstad LA (2013) Adaptation and constraint in a stickleback radiation. J Evol Biol 26:2396–2414. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12240

Walker JA (1997) Ecological morphology of lacustrine threespine stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus L. (Gasterosteidae) body shape. Biol J Linn Soc 61:3–50

Walker JA, Bell MA (2000) Net evolutionary trajectories of body shape evolution within a microgeographic radiation of threespine sticklebacks. J Zool Lond 252:293–302

Wark AR, Peichel CL (2010) Lateral line diversity among ecologically divergent threespine stickleback populations. J Exper Biol 213:108–117. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.031625

Wark AR, Greenwood AK, Taylor EM, Yoshida K, Peichel CL (2011) Heritable differences in schooling behavior among threespine stickleback populations revealed by a novel assay. PLoS ONE 6:e18316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0018316

Wark AR, Mills MG, Dang L-H, Chan YF, Jones FC, Brady SD, Absher DM, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Myers RM, Kingsley DM, Peichel CL (2012) Genetic architecture of variation in the lateral line sensory system of threespine sticklebacks. G3 2:1047–1056. https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.112.003079

Webb JF (1989) Gross morphology and evolution of the mechanoreceptive lateral-line system in teleost fishes. Brain Behav Evol 33:34–53

Webb JF (2014) Morphological diversity, development, and evolution of the mechanosensory lateral line system. In: Coombs S, Bleckmann H, Fay R, Popper N (eds) The lateral line system. Springer, New York, pp 17–72

Webb JF, Shirey JE (2003) Postembryonic development of the cranial lateral line canals and neuromasts in Zebrafish. Dev Dynam 228:370–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/dvdy.10385

Webb JF, Bird NC, Carter L, Dickson J (2014) Comparative development and evolution of two lateral line phenotypes in Lake Malawi cichlids. J Morph 275:678–692. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.20247

Wootton RJ (1984) A functional biology of the sticklebacks. University of California Press, London Pp, p 265

Wootton RJ (2009) The Darwinian stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus: a history of evolutionary studies. J Fish Biol 75:1919–1942

Wund MA, Valena S, Wood S, Baker JA (2012) Ancestral plasticity and allometry in threespine stickleback reveal phenotypes associated with derived, freshwater ecotypes. Biol J Linn Soc 105:573–583. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.2011.01815.x

Acknowledgements

MØM is grateful for the support of Mathias Wegner and Moritz Pockberger from the Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung, List, Germany during her field work on Sylt.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Vienna. SW was supported by the Austrian Science Fund, FWF, P29397 and the Young Investigator Award of the Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be constructed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahnelt, H., Ramler, D., Madsen, M.Ø. et al. Diversity and sexual dimorphism in the head lateral line system in North Sea populations of threespine sticklebacks, Gasterosteus aculeatus (Teleostei: Gasterosteidae). Zoomorphology 140, 103–117 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00435-020-00513-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00435-020-00513-1