Abstract

Purpose

To determine the risk factors and visual outcome of endophthalmitis associated with traumatic intraocular foreign body (IOFB) removal and its allied management.

Methods

A retrospective review was conducted of patients with penetrating eye trauma and retained IOFB with associated endophthalmitis managed at King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital over a 22 year period (1983 to 2004).

Results

There were 589 eyes of 565 patients (90.3% male; 9.7% female) which sustained ocular trauma and had retained IOFB that required management. Forty-four eyes (7.5%) developed clinical evidence of endophthalmitis at some point after trauma. From these 44 eyes, initial presenting visual acuity (VA) of 20/200 or better was recorded in 8 eyes (18.1%) and the remaining 36 eyes (81.9%) had VA ranging from 20/400 to light perception. Eleven eyes (25%) underwent IOFB removal and repair within 24 hours after trauma while 33 eyes (75%) had similar procedures done 24 hours or more after trauma. Thirty-one eyes (70%) underwent primary pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) at the time of removal of posteriorly located IOFBs. Definite positive cultures were obtained from 17 eyes (38.6%). Over a mean follow-up of 24.8 months, 21 eyes (47.7%) had improved VA, 6 eyes (13.6%) maintained presenting VA while 17 eyes (38.7%) had deterioration of their VA, including 10 eyes (22.7%) that were left with no light perception (NLP) vision. After the treatment of endophthalmitis, 20 eyes (45.4%) had VA of 20/200 or better at their last follow-up. Four eyes (12.9%) from the vitrectomy group (31 eyes) and 5 eyes (45.4%) from non-vitrectomy (11 eyes) group had final VA of NLP. Predictive factors for the good visual outcome included good initial presenting VA, early surgical intervention to remove IOFB (within 24 hours), and PPV. Predictors of poor visual outcome included IOFB removal 48 hours or later, posterior location and no PPV for the posteriorly located IOFB.

Conclusions

Delayed removal of IOFB following trauma may result in a significant increase in the development of clinical endophthalmitis. Other risk factors for poor visual outcome may include poor initial presenting VA, posterior location of IOFB and no vitrectomy at the time of IOFB removal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intraocular foreign body (IOFB) caused ocular trauma is a significant and unique type of trauma that requires skillful investigation and an early intervention. Endophthalmitis is an uncommon but potentially catastrophic complication of penetrating ocular injury with retained intraocular foreign bodies (IOFB) [1]. Studies have reported incidence of endophthalmitis ranging from none to as high as 13.5% [1–5]. Management of endophthalmitis associated with retained IOFB is a challenging subject. With advancement in vitreous surgery, a large number of eyes with ocular trauma and IOFB are being saved. Visual prognosis, however, is affected by the complexity of the confluent factors surrounding the IOFB, which include the size, site, material, trajectory, reactivity of foreign body, inflammatory response, degree and type of tissue damage, length of time since injury and any associated endophthalmitis [2]. Limited information is available regarding ocular trauma and IOFB-associated endophthalmitis outside of the United States and other developed countries [6–10]. In particular, very limited information on this entity is available from the Middle East. The current study was undertaken to analyze and report our experience at a large tertiary eye care referral center in the Middle East regarding the management of eyes with IOFBs and associated endophthalmitis. We identify the risk factors for the development of clinical endophthalmitis and visual outcome of such eyes at a major referral center in the Middle East.

Methods

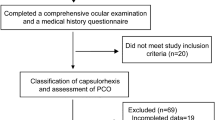

A detailed retrospective review was conducted of all patients who presented to King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital, a JCIA (Joint Commission International Accreditation, USA) accredited tertiary eye care referral center in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, from January 1983 to August 2004 with penetrating ocular trauma and retained intraocular foreign bodies (IOFB). Methods of IOFB extraction has varied during these years. For simplicity, the study period was divided into the first decade from 1983 to 1993 and the second decade from 1994 to 2004. For the past decade pars plana vitrectomy has been used more often for the posteriorly located IOFBs. Prior to removal of the foreign body (FB) all adhesions around the FB were released and it was freed from encapsulation where indicated. All IOFBs were removed by using IOFB forceps. Where necessary the sclerotomy was enlarged to facilitate easy removal of the FB. Endophotocoagulation was applied to the retina adjacent to the site of the IOFB. After removal of the FB, vitrectomy was utilized to remove any remains of FB capsule or fibrous tissue with the vitrectomy cutter. Only those eyes which showed any clinical evidence of endophthalmitis after trauma and retained IOFB were included in the study. Patients demographic studied included, age at presentation, sex, place of trauma, occupation, mode of injury and time between injury and repair. Other parameters included initial and final best corrected Snellen visual acuity, entry and location of IOFB and associated cataract, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, development of endophthalmitis, diagnostic studies performed, treatment rendered, type and size of IOFB. Complications such as cataract, retinal detachment and secondary procedures performed were also noted. Causes of visual loss such as corneal scarring, cataract, retinal detachment, retinal scars and loss of an eye were also investigated. In particular, all eyes with a retained IOFB and associated endophthalmitis were investigated and analyzed in detail.

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 10 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). We studied the association between the variables using the chi-square test because the data was categorical. Further multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted to predict the factors that were associated with favorable or poor visual outcome. A P < 0.05 was taken as a level of statistical significance.

Results

Among the 589 eyes of 565 patients (90.3% males; 9.7% females; 24 bilateral) with retained intraocular foreign bodies (IOFB) after trauma, 44 eyes (7.5%) had evidence of clinical endophthalmitis at the time of initial evaluation or subsequent to removal of the IOFB (Table 1). The setting of the injury resulting in IOFB varied, with the majority occurring at the place of employment in younger patients. The size of the IOFBs recovered ranged from 0.5 mm to 18 mm (average 4.2 mm). At presentation visual acuity (VA) of 20/200 or better was found in 8 eyes (18.1%), 20/400 to counting fingers in 6 (13.6%) and hand motion (HM) to light perception (LP) in 30 eyes (68.2%) (Table 2). Delay in treatment was mostly due to late patient referral after the trauma or lack of understanding on the part of the patient about the urgency in presentation to the primary care center. Endophthalmitis was recognized preoperatively in 32 eyes (72.7%) and post-operatively in 12 eyes (27.3%). In general, the size of the IOFB posed no significant risk of causing endophthalmitis except in cases where larger IOFB was associated with a significant trauma to the eye. The most important predictive factor of developing endophthalmitis was delayed repair of the globe and removal of IOFB. A delay in intervention of more than 24-hours was associated with a risk of clinical endophthalmitis (Fig. 1). In fact, only 11 eyes (25%) which developed endophthalmitis were repaired and IOFB removed within 24 hours after their trauma compared with 33 eyes (75%) that were repaired and IOFB removed more than 24 hours after trauma (range 2–42 days). In other words, a delay of more than 2 days in the repair of the traumatic globe and removal of IOFB was associated with a significant risk of endophthalmitis development (P < 0.05). The composition of IOFB had no significant effect on the development of clinical endophthalmitis. In particular, eyes with wood IOFB did not appear to be associated with increased risk of endophthalmitis compared to eyes with metallic IOFBs. The age of the patient had no bearing on the development of clinical endophthalmitis. However, when age and delayed repair of the trauma and removal of IOFB was correlated, an association with increased evidence of endophthalmitis was observed. The risk of endophthalmitis development and poor visual outcome was less common in eyes where the location of IOFB was in the anterior chamber or lens compared to the eyes having IOFB in the vitreous or retina. Among the 10 eyes where the final vision of no light perception (NLP) was recorded after the treatment of IOFB trauma and associated endophthalmitis, only 2 eyes had anterior location of foreign bodies compared with 8 eyes where IOFB were found in the posterior chamber, the difference being significant (P < 0.05). There were 24 cases of endophthalmitis during the first decade (1983–1993) and 20 cases of endophthalmitis during the second decade (1994–2004) of the study; the difference however was not statistically different.

Positive cultures were obtained from 17 eyes (38.6%) with clinical signs of endophthalmitis (Fig. 1). In addition, 10 eyes showed evidence of microorganisms on the Gram stain but no growth was observed in cultures. Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species were most often recovered (9 eyes); the other species included Hemophilus, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Eikenella, Corynebacterium, Propionebacterium acnea and Escherichea coli. None of the eyes with Bacillus, Pseudomonas or Corynebacterium attained any useful vision. All eyes suspected of endophthalmitis were administered intravitreal antibiotics and in some cases the treatment was repeated to obtain resolution of the signs. Most common intraocular antibiotics administered included vancomycin, ceftazidime and amikacin. Systemic preoperative antibiotics were administered in eyes with signs of endophthalmitis at approximately the same frequency as eyes without any signs of clinical endophthalmitis. However, systemic antibiotics were continued postoperatively for longer duration in eyes with signs of infectious endophthalmitis.

Thirty-one eyes (70%) underwent primary pars plana vitrectomy and 20 eyes (45%) had pars plana lensectomy at the time of IOFB removal and primary repair. Secondary procedures included scleral buckle around 8 globes, endolaser or external cryotherapy in 10 eyes and gas tamponade using SF6/C3F8 in 10 eyes for retinal breaks or retinal detachments. In addition, 11 eyes required cataract surgery, 12 eyes developed retinal detachment requiring additional treatment after the removal of IOFB and treatment of endophthalmitis. Vitreous hemorrhage was noted in 24 eyes that were associated with posteriorly located IOFBs but none among the eyes with IOFBs located in the anterior part of the eye. The final VA was 20/200 or better (defined as a good visual outcome) in 20 eyes (45%). Twenty-four eyes (55%) had final VA of less then 20/200 (defined as poor visual outcome). Twenty eyes (45%) had a final VA of hand motion or worse (Fig. 2). The causes of final vision of HM or worse in 20 eyes were phthisis (Fig. 3) or enucleation in 10 eyes, retinal detachment with proliferative vitroretinopathy in 5 eyes and corneal or macular scar in 5 eyes. Overall, 22 eyes (50%) that developed endophthalmitis due to trauma and retained IOFB had improvement in their VA. Ten eyes (22.7%) with endophthalmitis became NLP compared to 58 eyes (10.6%) from the larger group which became NLP but had no evidence of endophthalmitis, the difference being significant (P < 0.05). Among the 10 eyes with endophthalmitis where the final vision of NLP was recorded after the treatment of IOFBs and associated endophthalmitis, only 2 eyes had anterior location of FBs compared to 8 eyes where FBs were found in the posterior chamber. Among the patients with endophthalmitis, 4 eyes (12.9%) from the vitrectomy group (31 eyes) had final vision of NLP, while from the eyes without vitrectomy (11 eyes), 5 eyes (45.4%) had final vision of NLP, the difference between these two groups being significant (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Ocular trauma associated with retained intraocular foreign bodies (IOFB) constitutes a significant proportion (18–40%) of all ocular injuries requiring surgical management [1, 2]. Despite advances in vitreoretinal and microsurgical techniques, the management of these injuries remains a challenge. The risk of endophthalmitis developing after penetrating ocular injury with retained IOFB is relatively low with the current techniques of surgical repair [1]. The incidence of infectious endophthalmitis after retaining an IOFB has been reported to be as low as 0% to as high as 13.5% [3–5, 13], the mean incidence being 6.8% (Table 1). The results from the present study are in agreement with the above studies of endophthalmitis associated with retained IOFB. A delay in management of more than 24 hours was found to increase the risk of infectious endophthalmitis in the present study. From a large study of the National Eye Trauma System Registry, 91% of the eyes in which infectious endophthalmitis developed had such evidence at the time of initial evaluation [1]. Delay in primary repair at our tertiary care eye hospital in the Middle East was either due to the patient presenting late or being referred to our facility later in the course of trauma and retained IOFB. Despite methods of improved transportation, early diagnosis and referral to properly trained eye care professionals, morbidity due to IOFB associated trauma has not decreased over the last decade.

The risk of an infectious endophthalmitis developing with IOFB has been reported to increase with age [1]; although, no such trend was observed in the present study. However, when age and delayed repair of the trauma and removal of IOFB was correlated, an association with increased evidence of endophthalmitis in our group of patients was observed. These results are in agreement with previous observations that older patients with delayed primary repair do appear to have an increased susceptibility to developing infectious endophthalmitis compared with younger patients [1].

Visual acuity (VA) appears to be significantly affected in the eyes with IOFB that subsequently developed endophthalmitis. From a previous large study of retained IOFB, Roper-Hall [14] reported 555 cases over a 19 year period, where there were no bilateral cases: in 60 eyes IOFB was not removed, size of IOFB was recorded in only 89 eyes and the enucleation rate was 20%. From a more recent report of 96 cases of posterior segment IOFBs studied over a 14 year period with 8.6 months of average follow-up, endophthalmitis was recorded in 13.5% of cases [4]. The overall rate of 7.5% cases with endophthalmitis in the current study are within the reported range of larger series [1, 3–5, 14, 12].

Several preoperative and operative factors have been found to have prognostic value in the final visual outcome of the traumatized eye with retained IOFB and endophthalmitis. Initial VA is an indicator of final VA and is a well recognized predictor of visual outcome in most of the previously published studies on IOFBs [4, 15]. In our study, poor initial VA of HM or light perception was significant in predicting a poor visual outcome (Table 2). The risk of endophthalmitis development and poor visual outcome appeared to be significantly increased when the IOFBs were recovered from the posterior chamber (vitreous or retina), compared to the IOFBs recovered from the anterior chamber. Among the 10 eyes with endophthalmitis where the final vision of NLP was recorded after the treatment of IOFBs and associated endophthalmitis, only 2 eyes had anterior location of foreign bodies compared to 8 eyes where foreign bodies were found in the posterior chamber.

In our study, positive cultures were obtained in slightly more then one-third of the eyes with clinical signs of endophthalmitis. In general, the culture is often positive in clinically diagnosed endophthalmitis secondary to trauma than due to intraocular surgery. However, considering that our hospital is a tertiary eye care referral center, most of these patients were on topical as well as systemic antibiotics prior to their referral and obtaining cultures at the time of IOFB removal. This view is corroborated by the observations that 10 additional patients who had evidence of microorganisms on Gram stain showed no growth in culture. The microorganisms isolated from the eyes in the present study were similar to those reported in previous studies on the development of infectious endophthalmitis after IOFB trauma [1, 4]. Although, from many eyes suspected of infectious endophthalmitis, no definite organism was recovered. The fact that these eyes showed clinical improvement after intravitreal injection of antibiotics supports the notion that an infectious process was involved. In a recent study, reasonable visual outcomes with immediate intravitreal injection of antibiotics and delayed vitrectomy in patients with clinical features of endophthalmitis and retained IOFB have been achieved [16].

The role of vitrectomy in the treatment of penetrating ocular trauma has been considered a major advance in the last two decades [17]. Early vitrectomy has helped in attaining useful functional vision in 25–51% of the eyes with posterior segment trauma [17, 13], and in some series it has helped in significant survival of eyes without improvement of final visual outcome [17]. In our hospital, during the last decade, pars plana vitrectomy had been used more frequently for the posteriorly located IOFBs. Although there were fewer cases of IOFB-associated endophthalmitis during the second decade of the study period, statistically we did not find a difference between the two decades. In our study of endophthalmitis, only 12.9% of the eyes in which vitrectomy had been performed initially did the vision later become NLP compared to 38.5% in which the vision became NLP in the eyes which had not undergone vitrectomy as an initial procedure at the time of IOFB removal and repair of ocular trauma. Vitrectomy removes the vitreous and blood clot scaffold that provides a framework to the visual localization of IOFB; it helps to find retinal breaks and detachments which may not be visible in the setting of vitreous hemorrhage. Our results corroborate previous reports of beneficial effects of early vitrectomy in the setting of ocular trauma associated with IOFBs [13]. Removal of lens was not necessary in all cases with corneal entry wound because the lens injury was localized without interfering with view for vitrectomy. Removal of posterior segment IOFB by pars plana vitrectomy has been advocated because it provides direct viewing and controlled removal of the IOFB [3, 18]. With the advent of advanced instrumentation and viewing systems used in vitrectomy, most vitrectomies in our hospital were performed in the second decade compared to the first.

The size of IOFB has been found to be a significant predictive factor of poor visual outcome in the previous studies of IOFB removal [18]. A large IOFB is more likely to inflict severe damage at the time of entry because of its higher kinetic energy, leading to a poor visual prognosis [18]. However, when considering similar sized IOFBs, no particular association between the visual outcome and the size of IOFB in eyes which developed endophthalmitis was found in our study.

A preoperative retinal detachment may be present in 5–21% of the eyes with IOFB and has been reported to be an important risk factor for poor visual outcome [3, 19]. The timing of surgery in these eyes for the removal of IOFBs has been found to be an important prognostic factor for better visual outcome. Without delay, removal of IOFB has been found to reduce the chances of endophthalmitis [15, 19, 20]. In the absence of endophthalmitis, many studies have found no significant difference on the visual outcome when IOFB removal was delayed for several weeks [3, 18, 21]. Ahmadieh et al. reported a delay in IOFB removal of more then 4 weeks in 85% of their patients because a majority of their patients had war related IOFBs [22]. Lack of suspicion of IOFBs by primary care physicians has led to the delay in the treatment of up to 44% of patients resulting in a delay of up to 3 years in the diagnosis, treatment, or both, of IOFB [18, 21].

In conclusion, the data from this retrospective study reiterate the importance of prompt recognition of retained IOFBs and early repair of related injuries to prevent endophthalmitis and associated complications of visual loss. Final vision appears to be considerably determined by the presenting VA and severity of injury. Eyes with IOFBs in the anterior segment appear to have better prognosis compared to eyes having IOFBs in the posterior segment. Early vitrectomy at the time of IOFB removal may be beneficial for overall visual outcome of the operated eyes. Owing to the retrospective nature of our study and most of the reported studies and the various types of injuries in different settings, results from these studies are difficult to compare. It is hoped that with the advent of modern instruments such as wide-angle viewing systems and high-speed cutters, the chances of complications such as retinal detachment may be greatly reduced. A multi-center prospective study may be required to address some of the confounding factors in the management of IOFB and associated endophthalmitis.

References

Thompson JT, Parver LM, Enger CL et al (1993) Infectious endophthalmitis after penetrating injuries with retained intraocular foreign bodies. National Eye Trauma System. Ophthalmology 100:1468–1474

Azad RV, Kumar N, Sharma YR, Vohra R (2004) Role of prophylactic scleral buckling in the management of retained intraocular foreign bodies. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 32:58–61

Williams DF, Mieler WF, Abrams GW, Lewis H (1988) Results and prognostic factors in penetrating ocular injuries with retained intraocular foreign bodies. Ophthalmology 90:1318–1322

El-Asrar AM, Al-Amro SA, Khan NM, Kangave D (2000) Visual outcome and prognostic factors after vitrectomy for posterior segment foreign bodies. Eur J Ophthalmol 10:304–311

Behrens-Baumann W, Praetorius G (1989) Intraocular foreign bodies: 297 consecutive cases. Ophthalmologica 198:84–88

Katz J, Tielsch JM (1993) Lifetime prevalence of ocular injuries from the Baltimore Eye Survey. Arch Ophthalmol 111:1564–1568

Klopfer J, Tielsch JM, Vitale S et al (1992) Ocular trauma in the United States: Eye injuries resulting in hospitalization, 1984 through 1987. Arch Ophthalmol 110:838–842

Blomdhal S, Norell S (1984) Perforating eye injury in the Stockholm population. Acta Ophthalmol 62:378–390

McCarty CA, Fu CL, Taylor HR (1999) Epidemiology of ocular trauma in Australia. Ophthalmology 106:1847–1852

Wong TY, Tielsch JM (1999) A population-based study on the incidence of severe ocular trauma in Singapore. Am J Ophthalmol 128:345–351

Brinton GS, Topping TM, Hyndiuk RA et al (1984) Post-traumatic endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol 192:547–550

Khan MD, Kundi M, Mohammed Z, Nazeer AF (1987) A 6-year survey of intraocular and intraorbital foreign bodies in the Northwest Frontier Province, Pakistan. Br J Ophthalmol 71:716–719

Coleman DJ, Lucas BC, Rondeau MJ, Chang S (1987) Management of intraocular foreign bodies. Ophthalmology 94:1647–1653

Roper-Hall MJ (1954) Review of 555 cases of intra-ocular foreign bodies with special reference to prognosis. Br J Ophthalmol 38:65–99

Jonas JB, Knorr HL, Budde WM (2000) Prognostic factors in ocular injuries caused by intraocular or retrobulbar foreign bodies. Ophthalmology 107:823–828

Knox FA, Best RM, Kinsella F et al (2004) Management of endophthalmitis with retained intraocular foreign body. Eye 18:179–182

Esmaeli B, Elner SG, Schork MA, Elner VM (1995) Visual outcome and ocular survival after penetrating trauma. A clinicopathologic study. Ophthalmology 102:393–400

Wani VB, Al-Ajmi M, Thalib L et al (2003) Vitrectomy for posterior segment intraocular foreign bodies: visual results and prognostic factors. Retina 23:654–660

Greven CM, Engelbrecht NE, Slusher MM, Nagy SS (2000) Intraocular foreign bodies: management, prognostic factors, and visual outcomes. Ophthalmology 107:608–612

Mieler WF, Ellis MK, Williams DF, Han DP (1990) Retained intraocular foreign bodies and endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology 97:1532–1538

De Souza S, Howcroft MJ (1999) Management of posterior segment intraocular foreign bodies: 14 years’ experience. Can J Ophthalmol 34:23–29

Ahmadieh H, Sajjadi H, Azarmina M et al (1994) Surgical management of intraretinal foreign bodies. Retina 14:397–403

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Chaudhry, I.A., Shamsi, F.A., Al-Harthi, E. et al. Incidence and visual outcome of endophthalmitis associated with intraocular foreign bodies. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 246, 181–186 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-007-0586-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-007-0586-5