Abstract

Congestive heart failure developing after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Clinical trials of cell-based therapy after AMI evidenced only a moderate benefit. We could show previously that suspensions of apoptotic peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) are able to reduce myocardial damage in a rat model of AMI. Here we experimentally examined the biochemical mechanisms involved in preventing ventricular remodelling and preserving cardiac function after AMI. Cell suspensions of apoptotic cells were injected intravenously or intramyocardially after experimental AMI induced by coronary artery ligation in rats. Administration of cell culture medium or viable PBMC served as controls. Immunohistological analysis was performed to analyse the cellular infiltrate in the ischaemic myocardium. Cardiac function was quantified by echocardiography. Planimetry of the infarcted hearts showed a significant reduction of infarction size and an improvement of post AMI remodelling in rats treated with suspensions of apoptotic PBMC (injected either intravenously or intramoycardially). Moreover, these hearts evidenced enhanced homing of macrophages and cells staining positive for c-kit, FLK-1, IGF-I and FGF-2 as compared to controls. A major finding in this study further was that the ratio of elastic and collagenous fibres within the scar tissue was altered in a favourable fashion in rats injected with apoptotic cells. Intravenous or intramyocardial injection of apoptotic cell suspensions results in attenuation of myocardial remodelling after experimental AMI, preserves left ventricular function, increases homing of regenerative cells and alters the composition of cardiac scar tissue. The higher expression of elastic fibres provides passive energy to the cardiac scar tissue and results in prevention of ventricular remodelling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Within the last decades early reperfusion therapy significantly reduced mortality following acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and also improved survival and prognosis of patients. However, the development of chronic ischaemic heart disease and congestive heart failure represents one of the most frequent causes of hospitalisation in developed countries, particularly in patients with a large myocardial infarction [7, 41]. New therapeutic concepts were developed to reduce the risk of heart failure after an ischaemic event, ranging from the use of steroids in the 70s up to cell therapeutic strategies which were assessed in clinical trials over the last few years [6, 23, 34, 44]. More recently, new concepts were developed in cardiovascular research as how to modulate the paracrine and cellular response after myocardial ischaemia and by doing so reducing the loss of vital myocardium [15, 35]. It was shown that tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) acts as a major player in the post AMI paracrine microenvironment in a bidirectional way by not only causing transient contractile dysfunction but also by inducing cardioprotective effects. Concomitantly, regulating factors for TNF are up-regulated in stressed cardiac myocytes [8]. Moreover, TNF-alpha signalling also interacts with scar tissue formation after AMI by targeting fibroblasts, angiogenesis and also the system of matrixmetalloproteinases (MMP) and their inhibitors [2, 19, 36, 40]. More recently, studies further elucidated how paracrine factors mediate not only the tight regulation of post AMI inflammation but also cardioprotection after ischaemia which subsequently influences the formation of scar tissue and ventricular remodelling after AMI [5, 25].

These observations indicate that a rapid transition to the reparative phase after AMI mediated by cytokines, macrophages and myofibroblasts is a prerequisite for the preservation of cardiac function after ischaemia. Nevertheless, the fibrotic scar represents a thin, weakened area that is unable to withstand the pressure and volume load on the heart in the same manner as healthy myocardium would. The intraventricular pressure stresses the infarcted area with each contraction of the heart, the scar expands and the left ventricular chamber dilates over time [33]. Recent research has suggested that cardiac function may be improved after AMI by modifying the composition of myocardial scar tissue. One way of doing so could be to alter the ratio of elastic and collagenous fibres within the scar tissue in a positive way which would support the contractility of the damaged heart. Elastin is one of the major insoluble extracellular matrix components and consists of a core of tropoelastin surrounded by fibrillin and microfibrils. The elastin fibre network provides (scar) tissue with a critical property of elasticity and resilient recoil and maintains the architecture against repeated expansion. The elasticity of the myocardium highly depends on the ratio of muscle fibres to fibrotic tissue composed of cross-linked collagen [22]. A higher ratio of elastin expression in the myocardial scar may be able to alter the composition of the ventricular scar tissue in a way to preserve the elasticity of the infarcted heart. Based on these aspects, Mizuno et al. [27, 28] have shown that endothelial cells transfected with a plasmid vector containing the elastin gene increased elastic fibre expression within the scar significantly and preserved ventricular function in a rat model of AMI.

Another approach to prevent ventricular remodelling was investigated in an abundance of (pre-)clinical trials of stem cell therapy after AMI. Recently, this concept came under critical investigation since most clinical trials showed only inconsiderable beneficial results compared to control patients or these effects lasted only for a short period of time [3, 26]. Based on these results we sought to investigate an alternative approach namely whether injection of apoptotic cell suspensions shortly after AMI can prevent ventricular remodelling by combining immunomodulatory and pro-angiogenic effects. In 2005, this therapeutic principle was first described in a hypothesis by Thum et al. [38]. Several reports have substantiated this perception by showing the protective potential of stressed or apoptotic cell suspensions in various ischaemic disease entities [1, 11]. Moreover, experimental pre-treatment of spontaneously hypertensive rats with apoptotic cells reduced severe renal ischaemia reperfusion injury [39]. In a model of acute inflammatory lung injury, the administration of apoptotic cells enhanced the resolution of inflammation via increased TGF-beta secretion [17]. Of mechanistic relevance are also reports that demonstrate that infusion of apoptotic cells lead to allogeneic hematopoietic cell engraftment in a transplantation model and to a delay of lethal acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) [4, 31]. Moreover, infusion of donor apoptotic cells increased heart graft survival in a solid organ transplantation model [37].

However, the exact mechanism by which apoptotic cells can alter immune reactions after AMI and interfere with post-AMI tissue remodelling still remains to be elucidated. In our previous research, we have provided evidence that irradiation and induction of apoptosis in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) increased mRNA transcripts of Interleukin-8 and MMP9, two important factors for progenitor cell liberation from the bone marrow and their homing to sites of ischaemia [1]. Therefore, we sought to further elucidate the pleiotropic effects which apoptotic cells can induce when injected as a suspension in an experimental model of AMI. Here we show that suspensions of irradiated apoptotic PBMC injected either intravenously or intramyocardially cause progenitor cell homing to sites of myocardial ischaemia, prevent ventricular remodelling and alter the composition of cardiac scar tissue after AMI. This new concept evidences many convenient characteristics which are particularly of relevance compared to the therapeutic strategies mentioned earlier.

Methods

Acquisition of syngeneic rat PBMC suspensions for in vivo experiments

Animal experiments were approved by the committee for animal research, Medical University of Vienna (vote: BMBWK-66.009/0278-BrGT/2005). All experiments were performed in accordance to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). Syngeneic rat PBMC for in vivo experiments were separated by density gradient centrifugation from whole blood obtained from prior heparinized rats by direct punctuation of the heart. Cells were separated by Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Sweden) density gradient centrifugation. Apoptosis of PBMC was induced by Caesium-137 irradiation (Department of Transfusion Medicine, General Hospital Vienna) with 45 Gray (Gy). Cells were resuspended in serum-free UltraCulture Medium (UltraCulture, Lonza, Switzerland) and cultured in a humidified atmosphere for 18 h. Induction of apoptosis was measured by Annexin-V/propidium iodine (FITC/PI) co-staining (Becton–Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) on a flow cytometer. Annexin-positivity of PBMC was determined as >80% and these cells were consequently termed apoptotic PBMC (irradiated apoptotic PBMC, IA-PBMC).

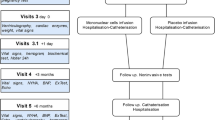

Experimental rat model of acute myocardial infarction

Acute myocardial infarction was induced in adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (weight 300–350 g) by ligating the left anterior descending artery (LAD) as described previously [1]. In short, animals were anaesthetized intraperitoneally with a mixture of xylazine (1 mg/100 g bodyweight) and ketamine (10 mg/100 g bodyweight) and ventilated mechanically. A left lateral thoracotomy was performed and a ligature using 6-0 prolene was placed around the LAD beneath the left atrium. Immediately after the onset of ischaemia, cell suspensions of 8.5 × 106 cells viable or apoptotic PBMC suspended in 0.3 mL UltraCulture Medium were injected in the femoral vein. Furthermore, apoptotic cells (8.5 × 106 cells) were also injected directly into the myocardium at five different sites of the peri-infarct zone. Injection of cell culture medium alone and sham operation served as controls in this experimental setting.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Animals were killed either 72 h or 6 weeks after experimental infarction. Hearts were explanted and then sliced at three layers at the level of the largest extension of infarcted area (n = 6 for 72 h analyses, n = 10–12 for 6 weeks analyses). Slices were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. The tissue samples were stained with hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) and Elastica van Gieson (EVG). Immunohistochemical evaluation 72 h after AMI was performed using the following antibodies directed to CD68 (MCA 341R, AbD Serotec, Kidlington, UK), c-kit (sc-168, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA), FLK1 (sc-6251, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA), IGF-I (sc-9013, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA) and FGF-2 (sc-79, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA). Tissue samples were evaluated on an Olympus AX70 microscope (Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 200× magnification and captured digitally using Meta Morph v4.5 Software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, USA). Image J planimetry software (Rasband, W.S., Image J, U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA) was utilised to determine the area of necrosis after 3 days and the size of myocardial infarct after 6 weeks. The extent of infarcted myocardial tissue (% of left ventricle) was calculated by dividing the area of the circumference of the infarcted area by the total endocardial and epicardial circumferenced areas of the left ventricle. Planimetric evaluation after 6 weeks was carried out on tissue samples stained with EVG for better comparison of vital myocardium and fibrotic areas. Infarction size was expressed as a percentage of the total left ventricular area. EVG stained tissue specimens were analysed microscopically for the ratio of elastic and collagen fibres. Using Image J Planimetry software, the ratio was calculated by dividing the area occupied by elastic fibres by the total area of scar tissue.

Assessment of cardiac function by echocardiography

Six weeks after induction of myocardial infarction, rats were anaesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 20 mg/kg xylazine. The sonographic examination was conducted on a Vivid 7 system (General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, USA). Analyses were performed by an experienced observer blinded to the treatment groups to which the animals were allocated. M-mode tracings were recorded from a parasternal short-axis view and functional systolic and diastolic parameters were obtained (shortening fraction, SF; left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, LVEDD; left ventricular end-systolic diameter, LVESD). Shortening fractional was calculated as follows: SF(%) = ((LVEDD − LVESD)/LVEDD) × 100.

Cell culture of human PBMC

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained from young healthy volunteers after informed consent. All experimental procedures were approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics (ethics committee vote: EK-Nr 2010/034) and were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki Principles. Cells were separated by Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Sweden) density gradient centrifugation. Apoptosis of PBMC was induced by Caesium-137 irradiation with 60 Gray (Gy) for in vitro experiments. Cells were resuspended in serum-free UltraCulture Medium and cultured in a humidified atmosphere for 24 h at a density of 2.5 × 106 cells/mL, n = 5. Induction of apoptosis was measured by Annexin-V/propidium iodine (FITC/PI) co-staining (Becton–Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) on a flow cytometer. Annexin-positivity of PBMC was determined to be >80% in order to characterise apoptotic cells.

Fibroblast cell culture, RNA isolation and cDNA preparation

Cell Culture supernatants were obtained from viable PBMC, IA-PBMC and mixed co-cultures of viable cells and IA-PBMC after 24 h (cell density 2.5 × 106 suspended in UltraCulture Medium). 1 × 105 human primary fibroblasts (Cascade Inc., Portland, USA) were exposed to supernatants obtained from viable PBMC, apoptotic PBMC and mixed cultures of viable and apoptotic cells for 24 h. Fibroblasts were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, USA) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS, PAA, Linz, Austria), 25 mM l-glutamine (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) and seeded in 12 well plates. After RNA extraction of fibroblasts (using RNeasy, QiIAGEN, Vienna, Austria) following the manufacturer’s instruction, cDNAs were transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad, Hercules, USA) as indicated in the instruction manual.

Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

mRNA expression was quantified by real time PCR with LightCycler Fast Start DNA Master SYBR Green I (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The primers for Elastin (forward: 5′-CCTACTTACGGGGTTGG-3′, reverse: 5′-GCCGAGCAGACAAGAA-3′), Collagen Type I (forward: 5′-GTGCTAAAGGTGCCAATGGT-3′, reverse: 5′-CTCCTCGCTTTCCTTCCTCT-3′), Collagen Type III (forward: 5′-GTCCATGGATGGTGGTTTTC-3′, reverse: 5′-CACCTTCATTTGACCCCATC-3′), Collagen Type V (forward: 5′-GTCCATACCCGCTGGAAA-3′, reverse: 5′-TCCATCAGGCAAGTTGTGAA-3′), IL-8 (forward: 5′-CTCTTGGCAGCCTTCCTGATT-3′, reverse: 5′-TATGCACTGACATCTAAGTTCTTTAGCA-3′), MMP1 (forward: 5′-GGTCTCTGAGGGTCAAGCAG-3′, reverse: 5′-CCGCAACACGATGTAAGTTG-3′), MMP3 (forward: 5′-TGCTTTGTCCTTTGATGCTG-3′, reverse: 5′-GGCCCAGAATTGATTTCCTT-3′), MMP9 (forward: 5′-GGGAAGATGCTGGTGTTCA-3′, reverse: 5′-CCTGGCAGAAATAGGCTTC-3′) and β-2-microglobulin (β2M, forward: 5′-GATGAGTATGCCTGCCGTGTG-3′, reverse: 5′-CAATCCAAATGCGGCATCT-3′) were designed as described previously [18]. The relative expression of the target genes was calculated by comparison with the house keeping gene β2M using a formula described by Pfaffl et al. [32]. The efficiencies of the primer pairs were determined as described [18].

Evaluation of cytokines and growth factors secreted by apoptotic PBMC

Membrane arrays for the detection of cytokines and growth factors in pooled cell culture supernatants derived from non-irradiated and IA-PBMC (cultured at a density of 2.5 × 106/ml, cells obtained from 4 healthy volunteers) were performed to scan the protein content (AAH-CYT-G4000, RayBiotech, Norcross, USA). Experiments were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, USA). All data are given as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney-Test was utilised to calculate significances between the groups. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant (p values were expressed as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Results

Histological and immunohistological analysis of explanted hearts 3 days after AMI

Since the inflammatory response after acute ischaemia determines the road map to ventricular dilation, we performed histological analysis after 72 h after AMI in order to study short term effects of intravenous (IV) or intramyocardial (IM) injection of apoptotic cell suspensions. H&E stained specimens obtained from control AMI animals evidenced a mixed cellular infiltrate in the wound areas in accordance with granulation tissue with abundance of neutrophils, macrophages/monocytes, lymphomononuclear cells admixed to dystrophic cardiomyocytes within the first 72 h after AMI (Fig. 1a,b). In contrast, rats treated with apoptotic PBMC suspensions evidenced a dense monomorphic infiltrate in wound areas (Fig. 1c,d). Furthermore, the total area of necrosis was significantly smaller in rats injected with apoptotic cells in comparison to controls (Fig. 1e). Immunohistological analysis revealed that the cellular infiltrate in both treatment groups (intravenous and intramyocardial injection) was composed of abundant CD68+ monocytes/macrophages that was much weaker in the control group (Fig. 1f–j). Cell counts quantified per high power-field (HPF) were 28.6 ± 2.4 (±SEM) in control, 36.0 ± 3.5 (±SEM) in animals injected with non-irradiated viable cells compared to 55.3 ± 3.4 and 76.5 ± 5.9 (± SEM) in rats treated with apoptotic cells (IV or IM, respectively). In addition, most of the medium-sized monocytoid cells were identified to be highly positive for c-kit (CD117) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (FLK-1). High power-field (HPF) cell counts for c-kit were 68.0 ± 3.1(±SEM) in controls, 77.0 ± 4.6 (±SEM) in the group injected with viable cell versus 121.2 ± 9.4 (±SEM) in IV and 168.6 ± 12.4 (±SEM) in IM injected rats (Fig. 1k–o). For FLK-1, values were 58.3 ± 5.6 (±SEM) in controls, 86.0 ± 7.0 (±SEM) for viable cell injected rats, 170.3 ± 7.1 (±SEM) for IV and 202.0 ± 9.4 (±SEM) for IM injected rats (Fig. 1p–t). Expression of these three cellular markers was more accentuated in rats injected with apoptotic cell suspensions compared to the control AMI group. (see representative images Fig. 1, n = 5–6 per group).

Results 3 days after AMI induction: H&E stained rat myocardium 3 days after LAD ligation. The cellular infiltrate appears to be more consolidated in apoptotic PBMC treated animals (a–d). The total area of necrosis was significantly reduced in both treatment groups compared to controls (e). Below, myocardial tissue stained for CD68 is shown (f–i). Quantification of positively stained cells per high power-field (HPF) indicated higher numbers of macrophages in both treatment groups (h–j). When tissue specimens were stained for c-kit (k–n), more of these cell populations could be detected in the epicardial zone in rats injected with apoptotic cells (m–o). Concomitantly, more cells staining positive for FLK-1/VEGF receptor 2 were found in the same areas (p–t)

Histological analysis 6 weeks after induction of AMI

Cardiac tissue specimens obtained 6 weeks after ligation of the LAD and stained according to the Elastica van Gieson protocol showed that hearts from rats injected with apoptotic PBMC suspensions showed a highly significant reduction of infarction area. Figure 3a shows representative images which evidence that rats treated with apoptotic cells demonstrate a significantly greater extent of viable myocardium within the anterior free wall of the left ventricle. In contrast, collagen deposition and scar formation extended through almost the entire left ventricular wall thickness in rats receiving control medium. Compared to controls and viable injected animals the left ventricular geometry was almost completely preserved in rats treated with irradiated apoptotic cell suspensions. The area of fibrosis as calculated by planimetry was 25% (percent of the left ventricle) in medium injected controls, 14% in viable cell injected animals compared to 6% (IV) and 8% (IM) in rats treated with apoptotic PBMC suspensions (p < 0.01 vs. controls, p < 0.05 vs. viable cell injected animals, n = 10–12 per group) (Fig. 2a,b).

Results of in vivo rat experiments after 6 weeks. a Hearts of apoptotic cell injected animals explanted 6 weeks after LAD ligation evidence less myocardial damage compared to controls. Hearts from medium or viable cell injected animals appear more dilated and show a greater extension of fibrotic tissue. b Statistical analysis of data obtained from planimetric evaluation of specimens collected 6 weeks after LAD ligation shows a mean scar extension of 25% in medium injected controls, 14% in viable cell injected animals compared to 6% (IV) and 8% (IM) in rats treated with apoptotic PBMC. c–e Results obtained by echocardiography 6 weeks after AMI (shortening fraction; left ventricular enddiastolic diameter, LVEDD; left ventricular endsystolic diameter, LVESD). Functional parameters were improved in comparison to medium or viable cell injected animals

Evaluation of functional parameters by echocardiography

Cardiac function was evaluated by means of echocardiography. Six weeks after ligation of the LAD the mean left ventricular shortening fractions (SF), left ventricular end-diastolic diameters (LVEDD), left ventricular end-systolic diameters (LVESD) were determined to be 19% ± 1 (SF), 10.4 mm ± 0.2 (LVEDD), 8.5 mm ± 0.2 (LVESD) in animals that received culture medium alone (±SEM). In animals injected with viable cells similar values were obtained: 18% ± 2 (SF), 11.0 mm ± 0.4 (LVEDD), 9.0 mm ± 0.5 (LVESD),

Noteworthy, rats with intravenous injection of apoptotic cell suspensions evidenced significantly improved functional parameters: 25% ± 3 (SF), 8.9 mm ± 0.3 (LVEDD), 6.8 mm ± 0.4 (LVESD). In animals with direct intramyocardial injection of apoptotic cells these parameters were improved as well: 26% ± 2 (SF), 9.8 mm ± 0.4 (LVEDD), 7.4 mm ± 0.5 (LVESD). Mean levels of cardiac function of healthy rats without myocardial infarction (sham operated) were as follows: 29% ± 2 (SF), 9.2 mm ± 0.4 (LVEDD), 6.5 mm ± 0.3 (LVESD), (p < 0.05 vs. viable cell injected animals and medium injected controls, n = 10–12 per group) (Fig. 2c–e).

These findings indicate a significant improvement or preservation of cardiac function in both treatment groups that were injected with apoptotic cell suspensions. Rats that were injected with viable non-irradiated PBMC or fresh culture medium showed signs of dilation which were accompanied by a considerable loss of ventricular function.

Alterations in the composition of the fibrotic scar tissue

Six weeks after AMI the composition of the fibrotic scar tissue was analysed microscopically (Elastica van Gieson staining). Especially within the border zone between viable myocardium and scar tissue a highly remarkably accumulation of elastic fibres was detected in animals injected with suspensions of apoptotic cells compared to controls (Fig. 3a–d). A planimetric analysis revealed that the fibrotic scar in apoptotic cell (IV and IM) injected rats was composed by 5.5% ± 1.1 and 8.9% ± 2.2 of elastic fibres compared to 0.2% ± 0.1 in controls and 2.9% ± 0.2 in viable injected animals (Fig. 3e), (p < 0.001 vs. control, n = 10–12 per group). This finding stands in relation to higher levels of cells stained positive for insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) in treated animals (Fig. 3i–k) compared to controls (Fig. 3f–h). In animals that were injected with apoptotic cell suspensions 36.0 ± 3.3 cells staining positive for IGF-I and 49.8 ± 5.2 for FGF-2 were found in immunohistological analyses of myocardial specimens 72 h after LAD ligation. In controls only 7.0 ± 1.6 IGF-I and 31.5 ± 2.3 FGF-2 positive cells were detectable.

Composition of fibrotic scar tissue. a–d Representative images of tissue specimens obtained 6 weeks after LAD ligation and stained according to the Elastica van Gieson protocol. Significantly more elastic fibres were found within the scar tissue of AMI rats injected with apoptotic PBMC. f, g Specimens stained for IGF-I in controls and treated animals. i, j Immunohistological staining for FGF-2. More cells staining positive for IGF-I and FGF-2 were found in hearts from rats injected with apoptotic cells. l, m Data from RT-PCR analyses. When fibroblasts were exposed to cell culture supernatants obtained from apoptotic PBMC the expression of elastin, collagen type III and IV, IL-8, MMP1, MMP3 and MMP9 was up-regulated

In order to specify the association of elastin and collagen production within myocardial scar tissue and mechanisms induced by apoptotic cells RT-PCR analyses were conducted. When exposing fibroblasts to cell culture supernatants obtained from apoptotic PBMC or apoptotic cells co-incubated with viable cells elastin expression increased only slightly by 1.2- to 1.4-fold. The expression of collagen type III and IV increased moderately by 1.9- to 2.5-fold compared to controls (Fig. 3l). Supernatants derived from apoptotic cells also increased the expression of IL-8 (4- to 6.5-fold), MMP1 (18- to 31-fold), MMP3 (10- to 16-fold) and MMP9 (4- to 7-fold) in fibroblasts indicating a mechanistic cross-talk between apoptotic cells, their secretome and resident cells that could be accounted for alterations of the compositions of the extracellular matrix (Fig. 3m).

Analysis of paracrine factors secreted by non-irradiated and irradiated apoptotic cells

Based on the finding that the expression of transcripts for IL-8 and MMPs were up-regulated in apoptotic cells we screened the supernatant obtained from irradiated and non-irradiated cell for 274 cytokines and growth factors. Considerable differences were observed (amongst others) for IL-8, VEGF, MMP3, MMP9, IL-16, ENA-78 and MIP-1alpha (see supplementary table).

Discussion

Over the last decade, cardiovascular research has focused on determining clinical protocols for stem cell therapy in order to salvage damaged myocardium after AMI. Here we present evidence that suspensions of apoptotic cells can serve as a potent therapeutic entity for preserving ventricular function after ischaemia when being injected shortly after occlusion of a coronary artery. We could show that apoptotic PBMC act in a cardioprotective manner by pleiotropic effects, first of all, the expression of the pro-angiogenic chemokine IL-8 and various matrixmetalloproteinases is induced in cells when being exposed to the conditioned medium of apoptotic PBMC. IL-8 and MMP9 are factors which are of great importance for reparative processes in the ischaemic heart by enabling progenitor cell populations of the bone marrow to enter the circulation and home to sites of myocardial damage [14, 20]. Consequently, more cells staining positive for c-kit and FLK-1/VEGF receptor 2 were detected in the myocardium of rats injected with apoptotic cells. This phenomenon was detectable even to a much greater extent when irradiated cells where injected directly into the ischaemic tissue. Furthermore, also higher numbers of macrophages where found in the ischaemic myocardium 3 days after induction of AMI, suggesting an accelerated repair phase in both treatment groups. When interpreting our data obtained by immunohistology correctly, we believe that injection of apoptotic cell suspensions shortly after AMI results in quicker changeover from an inflammatory phase to tissue infiltration of c-kit+/FLK-1 cells into the ischaemic myocardium causing increased angiogenesis in the early phase after AMI [30]. Previous work has confirmed that bone marrow progenitor cells improve cardiac function after AMI, regardless of whether transdifferentiation of the cells to cardiomyocytes occurs or not [29]. Fazel et al. defined the significant role of bone marrow derived c-kit+ cells as an essential population for cardiac repair. In a knock-out model of c-kit it has been shown that the triggering of this receptor is a necessary prerequisite for bone marrow progenitor cell mobilization after ischaemia since c-kit dysfunction led to a reduced myofibroblast repair response and subsequently to cardiac failure after experimental AMI. It was also determined that c-kit activation requires the activity of MMP9 within the bone marrow compartment [9, 12, 13]. Regarding our own data this correlates with an up-regulation of MMP transcripts in fibroblasts when exposed to conditioned medium obtained from cell cultures of apoptotic cells.

Six weeks after ligation of the LAD, a further important finding was that the treatment with apoptotic cells also attenuated the extent of infarction in this experimental AMI model. This also became apparent in echocardiography. Animals injected with irradiated apoptotic cell suspensions evidenced a significant improvement of all tested functional parameters.

Also of great interest was the finding that the composition of the extracellular matrix within the scar tissue was evidently altered compared to the controls. In Elastica van Gieson stained specimens, a considerable accumulation of elastic fibres, especially, in the border zone between vital cardiomyocytes and the fibrotic scar was detected. This alteration in the elastin/collagen ratio could be a major factor contributing to the improvement of cardiac function parameters in rats injected with apoptotic cells. This was even more pronounced when these cell suspensions were injected directly into the ischaemic myocardium. Together with the increased accumulation of elastic fibres we also found higher numbers of cells staining positive for insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2). It has been reported that these two growth factors contribute directly to the synthesis of elastic fibres within the extracellular matrix and regulate cardiac repair mechanisms after AMI [10, 21, 24, 42, 43]. There are a number of possible mechanisms by which a favourable ratio of elastic and collagenous fibres in the myocardial scar tissue could delay the onset of ventricular dysfunction and remodelling. A cardiac scar tissue showing more elastic properties and being more resistant could function as a shock absorbing cushion thus reducing the tractive effects of the acute increase in intraventricular pressure on the scar during systole. The recoil of the elastic fragments in the scar could provide passive energy to return the scar size and ventricular chamber volume to precontractile dimensions. These mechanistic characteristics are important for preventing or reducing the risk for ventricular remodelling.

Conclusion

In summary, we believe that PBMC undergoing apoptotic cell death feature many pleiotropic effects which evidence multiple beneficial characteristics in the setting of (experimental) AMI. Based on these data we conclude that apoptotic cells induce the expression of pro-angiogenic factors necessary for attraction of regenerative cells to sites of ischaemia. An additional mechanistic concept has already been discussed in the scientific literature and states that apoptotic cells interact with surrounding cells causing immunomodulation [16]. A modulatory effect on invading inflammatory cells into the ischaemic myocardium could also prove to be beneficial by reducing the secondary damage caused by neutrophils in the early stages after AMI. The combination of these mechanisms leads to a quicker resolution of the inflammatory phase after AMI, induces the homing of CD68+, c-kit+ and FLK-1+ cells, accelerates reparative processes, alters the elastin/collagen ratio within the scar tissue in a beneficial way and in the end improves ventricular function.

References

Ankersmit HJ, Hoetzenecker K, Dietl W, Soleiman A, Horvat R, Wolfsberger M, Gerner C, Hacker S, Mildner M, Moser B, Lichtenauer M, Podesser BK (2009) Irradiated cultured apoptotic peripheral blood mononuclear cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Eur J Clin Invest 39:445–456. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02111.x

Arras M, Strasser R, Mohri M, Doll R, Eckert P, Schaper W, Schaper J (1998) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is expressed by monocytes/macrophages following cardiac microembolization and is antagonized by cyclosporine. Basic Res Cardiol 93:97–107. doi:10.1007/s003950050069

Beitnes JO, Hopp E, Lunde K, Solheim S, Arnesen H, Brinchmann JE, Forfang K, Aakhus S (2009) Long-term results after intracoronary injection of autologous mononuclear bone marrow cells in acute myocardial infarction: the ASTAMI randomised, controlled study. Heart 95:1983–1989. doi:10.1136/hrt.2009.178913

Bittencourt MC, Perruche S, Contassot E, Fresnay S, Baron MH, Angonin R, Aubin F, Hervé P, Tiberghien P, Saas P (2001) Intravenous injection of apoptotic leukocytes enhances bone marrow engraftment across major histocompatibility barriers. Blood 98:224–230. doi:10.1182/blood.V98.1.224

Breivik L, Helgeland E, Aarnes EK, Mrdalj J, Jonassen AK (2011) Remote postconditioning by humoral factors in effluent from ischemic preconditioned rat hearts is mediated via PI3K/Akt-dependent cell-survival signaling at reperfusion. Basic Res Cardiol 106:135–145. doi:10.1007/s00395-010-0133-0

Bush CA, Renner W, Boudoulas H (1980) Corticosteroids in acute myocardial infarction. Angiology 31:710–714. doi:10.1177/000331978003101007

Cantor WJ, Ohman EM (1999) Results of recent large myocardial infarction trials, adjunctive therapies, and acute myocardial infarction: improving outcomes. Cardiol Rev 7:232–244. doi:10.1061/5377/99/704-232/0

Chorianopoulos E, Heger T, Lutz M, Frank D, Bea F, Katus HA, Frey N (2010) FGF-inducible 14-kDa protein (Fn14) is regulated via the RhoA/ROCK kinase pathway in cardiomyocytes and mediates nuclear factor-kappaB activation by TWEAK. Basic Res Cardiol 105:301–313. doi:10.1007/s00395-009-0046-y

Cimini M, Fazel S, Zhuo S, Xaymardan M, Fujii H, Weisel RD, Li RK (2007) c-kit dysfunction impairs myocardial healing after infarction. Circulation 116:I77–I82. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.708107

Conn KJ, Rich CB, Jensen DE, Fontanilla MR, Bashir MM, Rosenbloom J, Foster JA (1996) Insulin-like growth factor-I regulates transcription of the elastin gene through a putative retinoblastoma control element. A role for Sp3 acting as a repressor of elastin gene transcription. J Biol Chem 271:28853–28860. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.46.28853

Di Santo S, Yang Z, Wyler von Ballmoos M, Voelzmann J, Diehm N, Baumgartner I, Kalka C (2009) Novel cell-free strategy for therapeutic angiogenesis: in vitro generated conditioned medium can replace progenitor cell transplantation. PLoS One 4:e5643. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005643

Fazel S, Cimini M, Chen L, Li S, Angoulvant D, Fedak P, Verma S, Weisel RD, Keating A, Li RK (2006) Cardioprotective c-kit + cells are from the bone marrow and regulate the myocardial balance of angiogenic cytokines. J Clin Invest 116:1865–1877. doi:10.1172/JCI27019

Fazel SS, Chen L, Angoulvant D, Li SH, Weisel RD, Keating A, Li RK (2008) Activation of c-kit is necessary for mobilization of reparative bone marrow progenitor cells in response to cardiac injury. FASEB J 22:930–940. doi:10.1096/fj.07-8636com

Heissig B, Hattori K, Dias S, Friedrich M, Ferris B, Hackett NR, Crystal RG, Besmer P, Lyden D, Moore MA, Werb Z, Rafii S (2002) Recruitment of stem and progenitor cells from the bone marrow niche requires MMP-9 mediated release of kit-ligand. Cell 109:625–637. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00754-7

Heusch G, Kleinbongard P, Böse D, Levkau B, Haude M, Schulz R, Erbel R (2009) Coronary Microembolization: from bedside to bench and back to bedside. Circulation 120:1822–1836. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.888784

Hoffmann PR, Kench JA, Vondracek A, Kruk E, Daleke DL, Jordan M, Marrack P, Henson PM, Fadok VA (2005) Interaction between phosphatidylserine and the phosphatidylserine receptor inhibits immune responses in vivo. J Immunol 174:1393–1404

Huynh ML, Fadok VA, Henson PM (2002) Phosphatidylserine-dependent ingestion of apoptotic cells promotes TGF-beta1 secretion and the resolution of inflammation. J Clin Invest 109:41–50. doi:10.1172/JCI0211638

Kadl A, Huber J, Gruber F, Bochkov VN, Binder BR, Leitinger N (2002) Analysis of inflammatory gene induction by oxidized phospholipids in vivo by quantitative real-time RT-PCR in comparison with effects of LPS. Vascul Pharmacol 38:219–227. doi:10.1016/S1537-1891(02)00172-6

Kleinbongard P, Heusch G, Schulz R (2010) TNFalpha in atherosclerosis, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion and heart failure. Pharmacol Ther 127:295–314. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.05.002

Kocher AA, Schuster MD, Bonaros N, Lietz K, Xiang G, Martens TP, Kurlansky PA, Sondermeijer H, Witkowski P, Boyle A, Homma S, Wang SF, Itescu S (2006) Myocardial homing and neovascularization by human bone marrow angioblasts is regulated by IL-8/Gro CXC chemokines. J Mol Cell Cardiol 40:455–464. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.11.013

Kothapalli CR, Ramamurthi A (2008) Benefits of concurrent delivery of hyaluronan and IGF-1 cues to regeneration of crosslinked elastin matrices by adult rat vascular cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2:106–116. doi:10.1002/term.70

Li DY, Brooke B, Davis EC, Mecham RP, Sorensen LK, Boak BB, Eichwald E, Keating MT (1998) Elastin is an essential determinant of arterial morphogenesis. Nature 393:276–280. doi:10.1038/30522

Lunde K, Solheim S, Aakhus S, Arnesen H, Abdelnoor M, Egeland T, Endresen K, Ilebekk A, Mangschau A, Fjeld JG, Smith HJ, Taraldsrud E, Grøgaard HK, Bjørnerheim R, Brekke M, Müller C, Hopp E, Ragnarsson A, Brinchmann JE, Forfang K (2006) Intracoronary injection of mononuclear bone marrow cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 355:1199–1209. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055706

Matthews KG, Devlin GP, Conaglen JV, Stuart SP, Mervyn Aitken W, Bass JJ (1999) Changes in IGFs in cardiac tissue following myocardial infarction. J Endocrinol 163:433–445. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1630433

Mersmann J, Habeck K, Latsch K, Zimmermann R, Jacoby C, Fischer JW, Hartmann C, Schrader J, Kirschning CJ, Zacharowski K (2011) Left ventricular dilation in toll-like receptor 2 deficient mice after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion through defective scar formation. Basic Res Cardiol 106:89–98. doi:10.1007/s00395-010-0127-y

Meyer GP, Wollert KC, Lotz J, Pirr J, Rager U, Lippolt P, Hahn A, Fichtner S, Schaefer A, Arseniev L, Ganser A, Drexler H (2009) Intracoronary bone marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: 5-year follow-up from the randomized-controlled BOOST trial. Eur Heart J 30:2978–2984. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp374

Mizuno T, Yau TM, Weisel RD, Kiani CG, Li RK (2005) Elastin stabilizes an infarct and preserves ventricular function. Circulation 112:I81–I88. doi:10.1161/01.CIRCULATIONAHA.105.523795

Mizuno T, Mickle DA, Kiani CG, Li RK (2005) Overexpression of elastin fragments in infarcted myocardium attenuates scar expansion and heart dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288:H2819–H2827. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00862.2004

Möllmann H, Nef HM, Kostin S, von Kalle C, Pilz I, Weber M, Schaper J, Hamm CW, Elsässer A (2006) Bone marrow-derived cells contribute to infarct remodelling. Cardiovasc Res 71:661–671. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.06.013

Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Limana F, Jakoniuk I, Quaini F, Nadal-Ginard B, Bodine DM, Leri A, Anversa P (2001) Mobilized bone marrow cells repair the infarcted heart, improving function and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:10344–10349. doi:10.1073/pnas.181177898

Perruche S, Kleinclauss F, Bittencourt Mde C, Paris D, Tiberghien P, Saas P (2004) Intravenous infusion of apoptotic cells simultaneously with allogenic hematopoietic grafts alters anti-donor humoral immune responses. Am J Transplant 4:1361–1365. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00509.x

Pfaffl MW (2001) A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29:e45. doi:10.1093/nar/29.9.e45

Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E (1990) Ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Experimental observations and clinical implications. Circulation 81:1161–1672

Schächinger V, Erbs S, Elsässer A, Haberbosch W, Hambrecht R, Hölschermann H, Yu J, Corti R, Mathey DG, Hamm CW, Süselbeck T, Assmus B, Tonn T, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM (2006) Intracoronary bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 355:1210–1221. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060186

Schuh A, Liehn EA, Sasse A, Schneider R, Neuss S, Weber C, Kelm M, Merx MW (2009) Improved left ventricular function after transplantation of microspheres and fibroblasts in a rat model of myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol 104:403–411. doi:10.1007/s00395-008-0763-7

Skyschally A, Gres P, Hoffmann S, Haude M, Erbel R, Schulz R, Heusch G (2007) Bidirectional role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in coronary microembolization: progressive contractile dysfunction versus delayed protection against infarction. Circ Res 100:140–146. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000255031.15793.86

Sun E, Gao Y, Chen J, Roberts AI, Wang X, Chen Z et al (2004) Allograft tolerance induced by donor apoptotic lymphocytes requires phagocytosis in the recipient. Cell Death Differ 11:1258–1264

Thum T, Bauersachs J, Poole-Wilson PA, Volk HD, Anker SD (2005) The dying stem cell hypothesis: immune modulation as a novel mechanism for progenitor cell therapy in cardiac muscle. J Am Coll Cardiol 46:1799–1802. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.053

Tremblay J, Chen H, Peng J, Kunes J, Vu MD, Der Sarkissian S, deBlois D, Bolton AE, Gaboury L, Marshansky V, Gouadon E, Hamet P (2002) Renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in the rat is prevented by a novel immune modulation therapy. Transplantation 74:1425–1433. doi:10.1097/01.TP.0000034208.20704.E1

Valeur HS, Valen G (2009) Innate immunity and myocardial adaptation to ischemia. Basic Res Cardiol 104:22–32. doi:10.1007/s00395-008-0756-6

Velagaleti RS, Pencina MJ, Murabito JM, Wang TJ, Parikh NI, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Kannel WB, Vasan RS (2008) Long-term trends in the incidence of heart failure after myocardial infarction. Circulation 118:2057–2062. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.784215

Virag JA, Rolle ML, Reece J, Hardouin S, Feigl EO, Murry CE (2007) Fibroblast growth factor-2 regulates myocardial infarct repair: effects on cell proliferation, scar contraction, and ventricular function. Am J Pathol 171:1431–1440. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2007.070003

Wolfe BL, Rich CB, Goud HD, Terpstra AJ, Bashir M, Rosenbloom J, Sonenshein GE, Foster JA (1993) Insulin-like growth factor-I regulates transcription of the elastin gene. J Biol Chem 268:12418–12426

Wollert KC, Meyer GP, Lotz J, Ringes-Lichtenberg S, Lippolt P, Breidenbach C, Fichtner S, Korte T, Hornig B, Messinger D, Arseniev L, Hertenstein B, Ganser A, Drexler H (2004) Intracoronary autologous bone-marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: the BOOST randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet 364:141–148. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16626-9

Acknowlegments

The study was funded by the Christian Doppler Research Association, APOSCIENCE AG and the Medical University Vienna. The Medical University Vienna has claimed financial interest (patent number EP2201954). H.J.A. is a shareholder of APOSCIENCE AG.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lichtenauer, M., Mildner, M., Baumgartner, A. et al. Intravenous and intramyocardial injection of apoptotic white blood cell suspensions prevents ventricular remodelling by increasing elastin expression in cardiac scar tissue after myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol 106, 645–655 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00395-011-0173-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00395-011-0173-0