Abstract

The tumour-stroma ratio (TSR) and tumour budding (TB) are two high-risk factors with potential to be implemented in the next TNM classification. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the practical application of the two biomarkers based on reproducibility, independency and prognostic value. Patients diagnosed with stage II or III colon cancer who underwent surgery between 2005 and 2016 were included. Both TSR and TB were scored on haematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue sections. The TSR, based on the relative amount of stroma, was scored in increments of 10%. TB was scored following the consensus guidelines; a bud was defined as ≤ 4 tumour cells. For analysis, three categories were used. Cohen’s kappa was used for reproducibility. The prognostic value was determined with survival analysis. In total, 246 patients were included. The TSR distribution was N = 137 (56%) stroma-low and N = 109 (44%) stroma-high. The TB distribution was TB-low N = 194 (79%), TB-intermediate N = 35 (14%) and TB-high N = 17 (7%). The reproducibility of the TSR was good (interobserver agreement kappa = 0.83 and intraobserver agreement kappa = 0.82), whereas the inter- and intraobserver agreement for scoring TB was moderate (kappa 0.47 and 0.45, respectively). The survival analysis showed an independent prognostic value for disease-free survival for TSR (HR 1.57; 95% CI 1.01–2.44; p = 0.048) and for TB-high (HR 2.01; 95% CI 1.02–3.96; p = 0.043). Based on current results, we suggest the TSR is a more reliable parameter in daily practice due to better reproducibility and independent prognostic value for disease-free survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The prognosis and selection for adjuvant treatment of colon cancer patients is largely based on the Tumour Node Metastasis (TNM) classification [3]. Patients diagnosed with stage III or stage II with one or more high-risk (ASCO) criteria will usually be selected for adjuvant chemotherapy [3]. However, among patients staged II without any high-risk factors, approximately 30% will suffer from recurrent disease within 3 to 5 years after surgery [28]. To better predict which patients will develop recurrence, additional high-risk factors next to the ASCO criteria have been described [3]. These “new” high-risk factors should improve the selection of patients who will likely benefit from adjuvant therapy. Thus, high-risk criteria should not only select stage II patients at high risk for recurrence, but also select patients at stage III who are likely to be overtreated with adjuvant therapy.

New prognostic parameters have been identified not only on the basis of molecular pathology (for example CMS analysis) [13] and lymph node assessment (for example one-step nucleic acid amplification assay (OSNA)) [1, 5], but also on simple morphologic parameters. Morphologic parameters are tissue based and can be evaluated during routine pathology practice.

The tumour-stroma ratio (TSR) is a biomarker based on the microenvironment of the tumour and has proven to be a strong prognostic parameter [29, 30]. The TSR is based on the relative amount of stroma in the primary tumour. Patients with a tumour containing > 50% stroma (stroma-high) have a worse prognosis, compared to patients with a tumour of ≤ 50% stroma (stroma-low). The TSR is validated by many international study groups and is prognostic in multiple epithelial cancer types [29, 30]. The TSR is scored on haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections used in routine diagnostics; the scoring method is easy to learn and well reproducible and takes about 1–2 min [27].

Tumour budding (TB), the propensity of the primary tumour to bud off single cells and cell clusters (≤ 4 cells) at the invasive front, correlates with prognosis and is also frequently evaluated as a new biomarker in colon cancer. According to the guidelines, TB scoring should be performed at the invasive front of a tumour on an H&E-stained section [20]. The reproducibility of TB on H&E sections shows highly variable results [7, 12, 17, 18]. Therefore, some studies use cytokeratin-stained sections to identify the tumour buds for better interobserver agreement [10, 16]. Various studies showed TB to be an independent prognostic biomarker for overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) in stage I and stage II colon cancer patients [9, 16, 24]. Patients with tumours with high budding have a worse prognosis compared to patients with low budding. Recently, it was recommended to report TB in T1 tumours for decision-making about additional resection after biopsy or removal of a polyp [2].

Both TSR and TB have shown to be prognostic biomarkers in several series of colon cancer patients and both seem potentially suitable to use in routine pathology diagnostics. In order to implement TSR and/or TB as prognostic factors in daily clinical practice, their robustness and reproducibility should be thoroughly assessed [4]. TB has recently been added to the guidelines for locally advanced colon cancer [2]. The prospective validation of the TSR as a biomarker is currently under investigation in the UNITED study [25, 26].

Here, we analyse the value of TSR and TB by comparing their reproducibility, independency from one another and the prognostic value in stage II and stage III colon cancer patient samples.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

Patients who underwent curative surgery for colon cancer, between January 2005 up to and including December 2016 at the LUMC, were retrospectively included in this cohort study. Patients were included when they met the following inclusion criteria: pathological stage II or stage III colon cancer and age ≥ 18 years. The following exclusion criteria were met: rectal cancer, neo-adjuvant treatment, a medical history of cancer 10 years prior to colon cancer (except for basal cell skin cancer or cervical carcinoma in situ) or any colon cancer in history, double tumours, and/or deceased within 3 months after surgery (Supplementary table 1). The H&E-stained slides used for routine diagnostics were collected from the Department of Pathology and the slides were anonymised and scanned with the Panoramic 250 scanner (3DHistech, Hungary) (tissue level pixel size ~ 0.33 µm/pixel) for digital analysis. The observers were blinded for clinical and pathological data and for each other’s results during biomarker scoring.

Tumour-stroma ratio

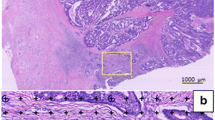

The TSR was scored on H&E-stained sections from the primary tumour by two observers (MS and GvP, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden). The TSR was scored at a 100 × magnification. The stroma percentage was scored in increments of 10, in a field with as much as possible tumour-stroma and with tumour cells on four opposite sides of the vision field [22, 23, 27]. If no agreement was reached, a third observer was consulted (HvK, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen). One of the observers (MS) scored the TSR also digitally, using a circular annotation of 3.4mm2 to mimic the field of view of a 100 × magnification. For analysis, the TSR was dichotomised. A tumour with an amount of stroma of ≤ 50% was classified as stroma-low, and a percentage > 50% was classified as stroma-high, in line with previous studies [15, 22, 23, 27]. In Fig. 1, an example of a stroma-low (A) and a stroma-high tumour (B) is shown.

Tumour budding

TB was scored, on exactly the same slides as the TSR, by two observers (VT (Haaglanden Medical Center, the Hague) and HvK) as recommended by the consensus [20]. HvK scored TB both microscopically and digitally, and VT scored TB only digitally. A tumour bud was determined as a single cell or a small cluster of cells to a maximum of four cells. TB was scored at the invasive front, at a single vision field by a magnification of 200 × . The number of buds was normalised as described in the conversion table in the consensus. When TB was scored digitally, an annotation with an area of 0.785mm2 was used. For survival analysis, the microscopic numbers were used, and the continuous numbers were categorised for statistical analysis. The three categories were TB-low (0–4 buds), TB-intermediate (5–9 buds) and TB-high (≥ 10 buds) [20]. In Fig. 1, an example of a TB-low (C) and a TB-high tumour (D) is shown.

Statistics

Descriptive variables are presented with mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed continuous variables. Non-normally distributed continuous variables are presented by median and range. The chi-square test is used for measuring associations between categorical variables. Cohen’s kappa is used to determine the interobserver agreement of scoring TSR and TB (digitally) and to determine the intraobserver agreement for scoring TSR and TB (microscopic vs digital).

The prognostic value of the two individual parameters was explored. DFS was defined as the time from surgery to recurrence or death, depending on what occurred first. OS was defined as the time from surgery to death of any cause.

Univariate survival analysis was performed using a Kaplan-Meijer curve and a log rank test. Cox regression analysis was performed for univariate and multivariate analysis for hazard ratios (HR) and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

All tests were 2-sided and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient cohort

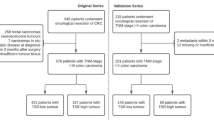

In total, 381 colon cancer stage II or stage III patients underwent surgery in the time period 2005–2016. Of these, 135 patients were excluded because one of the exclusion criteria was met, most often (N = 70) due to a medical history of cancer, and 246 patients were included in the cohort (Fig. 2). The tumours of these patients were scored for both TSR and TB.

The patient population in the cohort had a mean age of 68 years (SD 12 years) and 54% males (N = 134). Fifty-three per cent (N = 131) of the patients had pathological stage (p-Stage) II and 92 patients (37%) received adjuvant therapy. The TSR distribution was N = 137 (56%) stroma-low and N = 109 (44%) stroma-high. TB was divided in 3 categories: TB-low (N = 194 (79%)), TB-intermediate (N = 35 (14%)) and TB-high (N = 17 (7%)). All baseline characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Interobserver variability

The interobserver agreement for scoring TSR between the two observers was good to almost perfect (kappa = 0.83). The TSR was also scored digitally by one observer (MS), and a good to almost perfect intraobserver agreement was reached (kappa = 0.82).

The interobserver agreement for scoring TB was moderate with a kappa of 0.47. One of the observers (HvK) scored the sections microscopically and digitally for TB, with a moderate intraobserver agreement of kappa 0.45. A wide variety of scoring was observed when reviewing the discrepancies, even within one case, and no trends or obvious reason for discrepancy could be detected that could explain the inter- or intraobserver variation.

Association

Of the 246 patients, 120 (49%) were categorised as stroma-low and TB-low (low-risk patients), and 10 (4%) patients were classified as stroma-high and TB-high (high-risk patients). The distribution of TSR and TB is shown in supplementary Table 2. An association between TSR and TB was found (chi-square p = 0.001).

Survival analysis

The median follow-up time was 47 months (range 4–158). During follow-up, 48 (20%) patients had recurrence of disease, and 68 (28%) patients died. In total, 83 (34%) DFS events occurred, due to the fact that some patients deceased with recurrence.

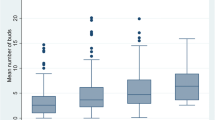

There was no significant difference in OS for TSR (HR 1.36; 95% CI 0.84–2.19; p = 0.206). However, the TSR was prognostic for DFS (HR 1.59; 95% CI 1.03–2.45; p = 0.036). Univariate analysis showed that TB was prognostic for OS (TB-high HR 2.36; 95% CI 1.16–4.81; p = 0.018) and for DFS (TB-high HR 2.40; 95% CI 1.23–4.70; p = 0.011). Kaplan-Meijer survival curves for TSR and TB are shown in Fig. 3.

Based on the results from the univariate Cox regression analysis (Table 2), in the multivariate Cox regression model, the results were corrected for age and pT-status. TSR remained a significant prognostic parameter for DFS (HR 1.57; 95% CI 1.01–2.44; p = 0.048), but this prognostic value was not found for OS. For TB, the prognostic value did not retain/remain significant in multivariate analysis for OS, but for DFS, TB-high remained prognostic (HR 2.01; 95% CI 1.02–3.96; p = 0.043) (Table 3).

Discussion

In the current study, two morphology-based histological parameters were evaluated and correlated with the prognosis of stage II and stage III colon cancer patients. Both parameters are easy to assess in daily routine pathology, as they are scored on H&E-stained sections. This study showed that TSR was an independent prognostic parameter for DFS, but not for OS. TB was a prognostic parameter for OS as well as for DFS in the univariate analysis, but did not remain significant as an independent prognostic parameter after multivariate analysis. No clear explanation could be found why the OS for TSR was not significantly different between the stroma-low and stroma-high group. When observing the survival curves, in the first year after surgery, more people died in the stroma-low group. At baseline, the stroma-low group was slightly older and more often at stage III; however, these groups were not significantly different. Elderly patients are generally at higher risk for developing late surgery-related complications and may die due to these complications [8, 11]. TB was probably not prognostic due to the fact that the group TB-high was small (N = 17 (7%)). However, TB is recommended by the ESMO guidelines for localised colon cancer to score in daily diagnostics [2]. The prognostic significance of TB was evaluated by Landau et al. in a cohort of stage III colon cancer patients, showing TB to be an independent prognostic parameter for recurrence-free survival [19]. In contrast, analysing the prognostic effect of TB in all stages of colon cancer TB failed to be significant as an independent prognostic factor, except when stage II patients were analysed separately [6]. In the current study, we did not analyse stage II and stage III separately, due to the low number of patients with TB-high score (stage II 10 patients, stage III 7 patients).

The TSR and TB were both scored by two observers, as is preferred in the research setting. The interobserver agreement of scoring TSR was good to almost perfect (kappa = 0.83), and this result is comparable with current literature [27]. The interobserver agreement for scoring TB has shown to be moderate (kappa = 0.47), as was the intraobserver agreement (kappa = 0.45). The interobserver variability for TB is diverse [7, 12, 17, 18], and our results are consistent with previous research [14, 21].

In daily pathology practice, there is currently a shift towards digital microscopy. Therefore, we compared the microscopical and digital scoring for both TSR and TB. The TSR was well reproducible (intraobserver agreement of kappa = 0.82). TB however showed only a moderate agreement between the microscopical assessment and the digitalised image assessment (intraobserver agreement of kappa = 0.45).

It is remarkable that TB-low and TB-intermediate show similar overall survival curves. Only TB-high showed a significant worse prognosis compared to the other two groups. In our study, the TB-high group is small with 7% (N = 17) of the cases in this group, which is comparable with the findings of Eriksen et al. [10]. In their study, TB was scored on cytokeratin-stained sections and the score was divided into two groups with the cut-off point at 10 buds (≥ 10 buds = budding-high). Here, TB was not significant for survival. We may conclude that TB-high is a prognostic factor, but only for a small subgroup of the patient population. Eriksen et al. also investigated the prognostic value of the TSR and showed that the TSR was independently prognostic for survival (DFS and OS).

An association between TSR and TB was found. The hypothesis is that patients who are stroma-high and TB-high have a significant worse survival compared to stroma-low and TB-low patients. It would be interesting to investigate this combined parameter for impact on survival, but the patient groups in our study were too small to draw reliable conclusions.

As all retrospective cohort studies, this design is a limitation of the current study. As a benefit of the retrospective design, long-time follow-up data was available for all patients in the cohort. The number of patients in the cohort should preferentially be larger and needs validation in an independent validation cohort. The UNITED study, a multicentre prospective study, could serve as a good potential [25].

Both TB and TSR are scored on H&E-stained sections and can thus be scored during routine diagnostics. Comparing both methods, TSR is a fast and easy parameter to score and is highly reproducible compared to TB. Some pathologists prefer to score TB after the slide is stained for cytokeratin for better visualisation of the tumour buds. This certainly helps to increase the reproducibility, but also makes the scoring more costly and time consuming.

Regarding the simplicity and consistency of assessing TSR and its independent prognostic value for disease-free survival of stage II and III colon cancer patients, we suggest that adding TSR as a biomarker in the pathology report could be of value in clinical decision policy.

Data availability

The dataset analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aldecoa I, Atares B, Tarragona J, Bernet L, Sardon JD, Pereda T, Villar C, Mendez MC, Gonzalez-Obeso E, Elorriaga K, Alonso GL, Zamora J, Planell N, Palacios J, Castells A, Matias-Guiu X, Cuatrecasas M (2016) Molecularly determined total tumour load in lymph nodes of stage I-II colon cancer patients correlates with high-risk factors. A multicentre prospective study. Virchows Arch 469:385–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-016-1990-1

Argiles G, Tabernero J, Labianca R, Hochhauser D, Salazar R, Iveson T, Laurent-Puig P, Quirke P, Yoshino T, Taieb J, Martinelli E, Arnold D (2020) Localised colon cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.06.022

Benson AB 3rd, Schrag D, Somerfield MR, Cohen AM, Figueredo AT, Flynn PJ, Krzyzanowska MK, Maroun J, McAllister P, Van Cutsem E, Brouwers M, Charette M, Haller DG (2004) American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 22:3408–3419. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.05.063

Califf RM (2018) Biomarker definitions and their applications. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 243:213–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1535370217750088

Croner RS, Geppert CI, Bader FG, Nitsche U, Spath C, Rosenberg R, Zettl A, Matias-Guiu X, Tarragona J, Guller U, Sturzl M, Zuber M (2014) Molecular staging of lymph node-negative colon carcinomas by one-step nucleic acid amplification (OSNA) results in upstaging of a quarter of patients in a prospective, European, Multicentre study. Br J Cancer 110:2544–2550. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.170

Dawson H, Galuppini F, Trager P, Berger MD, Studer P, Brugger L, Zlobec I, Inderbitzin D, Lugli A (2018) Validation of the international tumor budding consensus conference (ITBCC 2016) recommendations on tumor budding in stage I-IV colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2018.10.023

De Smedt L, Palmans S, Sagaert X (2016) Tumour budding in colorectal cancer: what do we know and what can we do? Virchows Arch 468:397–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-015-1886-5

Dekker JW, Gooiker GA, Bastiaannet E, van den Broek CB, van der Geest LG, van de Velde CJ, Tollenaar RA, Liefers GJ. Steering Committee of the 'Quality Information System Colorectal Cancer P (2014) Cause of death the first year after curative colorectal cancer surgery; a prolonged impact of the surgery in elderly colorectal cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 40:1481–1487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2014.05.010

Eriksen AC, Andersen JB, Lindebjerg J, dePont CR, Hansen TF, Kjaer-Frifeldt S, Sorensen FB (2018) Does heterogeneity matter in the estimation of tumour budding and tumour stroma ratio in colon cancer? Diagn Pathol 13:20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-018-0697-9

Eriksen AC, Sorensen FB, Lindebjerg J, Hager H, dePont CR, Kjaer-Frifeldt S, Hansen TF (2018) The prognostic value of tumour stroma ratio and tumour budding in stage II colon cancer. A nationwide population-based study. Int J Colorectal Dis 33:1115–1124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-018-3076-9

Gooiker GA, Dekker JW, Bastiaannet E, van der Geest LG, Merkus JW, van de Velde CJ, Tollenaar RA, Liefers GJ (2012) Risk factors for excess mortality in the first year after curative surgery for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 19:2428–2434. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2294-6

Graham RP, Vierkant RA, Tillmans LS, Wang AH, Laird PW, Weisenberger DJ, Lynch CF, French AJ, Slager SL, Raissian Y, Garcia JJ, Kerr SE, Lee HE, Thibodeau SN, Cerhan JR, Limburg PJ, Smyrk TC (2015) Tumor budding in colorectal carcinoma: confirmation of prognostic significance and histologic cutoff in a population-based cohort. Am J Surg Pathol 39:1340–1346. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000504

Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, de Reynies A, Schlicker A, Soneson C, Marisa L, Roepman P, Nyamundanda G, Angelino P, Bot BM, Morris JS, Simon IM, Gerster S, Fessler E, De Sousa EMF, Missiaglia E, Ramay H, Barras D, Homicsko K, Maru D, Manyam GC, Broom B, Boige V, Perez-Villamil B, Laderas T, Salazar R, Gray JW, Hanahan D, Tabernero J, Bernards R, Friend SH, Laurent-Puig P, Medema JP, Sadanandam A, Wessels L, Delorenzi M, Kopetz S, Vermeulen L, Tejpar S (2015) The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med 21:1350–1356. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3967

Hacking S, Angert M, Jin C, Kline M, Gupta N, Cho M, Thomas R, Lee L, Chavarria H, Nasim M (2019) Tumor budding in colorectal carcinoma: an institutional interobserver reliability and prognostic study of colorectal adenocarcinoma cases. Ann Diagn Pathol 43:151420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2019.151420

Huijbers A, Tollenaar RA, Pelt GW, Zeestraten EC, Dutton S, McConkey CC, Domingo E, Smit VT, Midgley R, Warren BF, Johnstone EC, Kerr DJ, Mesker WE (2013) The proportion of tumor-stroma as a strong prognosticator for stage II and III colon cancer patients: validation in the VICTOR trial. Ann Oncol 24:179–185. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mds246

Koelzer VH, Assarzadegan N, Dawson H, Mitrovic B, Grin A, Messenger DE, Kirsch R, Riddell RH, Lugli A, Zlobec I (2017) Cytokeratin-based assessment of tumour budding in colorectal cancer: analysis in stage II patients and prospective diagnostic experience J Pathol. Clin Res 3:171–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjp2.73

Koelzer VH, Zlobec I, Berger MD, Cathomas G, Dawson H, Dirschmid K, Hadrich M, Inderbitzin D, Offner F, Puppa G, Seelentag W, Schnuriger B, Tornillo L, Lugli A (2015) Tumor budding in colorectal cancer revisited: results of a multicenter interobserver study. Virchows Arch 466:485–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-015-1740-9

Koelzer VH, Zlobec I, Lugli A (2016) Tumor budding in colorectal cancer–ready for diagnostic practice? Hum Pathol 47:4–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2015.08.007

Landau MA, Zhu B, Akwuole FN, Pai RK (2019) Histopathological predictors of recurrence in stage III colon cancer: reappraisal of tumor deposits and tumor budding using AJCC8 criteria. Int J Surg Pathol 27:147–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066896918787275

Lugli A, Kirsch R, Ajioka Y, Bosman F, Cathomas G, Dawson H, El Zimaity H, Flejou JF, Hansen TP, Hartmann A, Kakar S, Langner C, Nagtegaal I, Puppa G, Riddell R, Ristimaki A, Sheahan K, Smyrk T, Sugihara K, Terris B, Ueno H, Vieth M, Zlobec I (2016) Quirke P (2017) Recommendations for reporting tumor budding in colorectal cancer based on the International Tumor Budding Consensus Conference (ITBCC). Mod Pathol 30:1299–1311. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.46

Martin B, Schafer E, Jakubowicz E, Mayr P, Ihringer R, Anthuber M, Schenkirsch G, Schaller T, Markl B (2018) Interobserver variability in the H&E-based assessment of tumor budding in pT3/4 colon cancer: does it affect the prognostic relevance? Virchows Arch 473:189–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-018-2341-1

Mesker WE, Junggeburt JM, Szuhai K, de Heer P, Morreau H, Tanke HJ, Tollenaar RA (2007) The carcinoma-stromal ratio of colon carcinoma is an independent factor for survival compared to lymph node status and tumor stage. Cell Oncol 29:387–398

Mesker WE, Liefers GJ, Junggeburt JM, van Pelt GW, Alberici P, Kuppen PJ, Miranda NF, van Leeuwen KA, Morreau H, Szuhai K, Tollenaar RA, Tanke HJ (2009) Presence of a high amount of stroma and downregulation of SMAD4 predict for worse survival for stage I-II colon cancer patients. Cell Oncol 31:169–178. https://doi.org/10.3233/CLO-2009-0478

Nakamura T, Mitomi H, Kanazawa H, Ohkura Y, Watanabe M (2008) Tumor budding as an index to identify high-risk patients with stage II colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 51:568–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-008-9192-9

Smit M, van Pelt G, Roodvoets A, Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg E, Putter H, Tollenaar R, van Krieken JH, Mesker W (2019) Uniform noting for international application of the tumor-stroma ratio as an easy diagnostic tool: protocol for a multicenter prospective cohort study. JMIR Res Protoc 8:e13464. https://doi.org/10.2196/13464

Smit M vPG, Tollenaar R, Mesker W (2020) Uniform noting for international application of the tumour-stroma ratio as easy diagnostic tool (UNITED) study website. http://watchstroma.com/. Accessed 27 July 2020

van Pelt GW, Kjaer-Frifeldt S, van Krieken J, Al Dieri R, Morreau H, Tollenaar R, Sorensen FB, Mesker WE (2018) Scoring the tumor-stroma ratio in colon cancer: procedure and recommendations. Virchows Arch 473:405–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-018-2408-z

Vogelaar FJ, van Pelt GW, van Leeuwen AM, Willems JM, Tollenaar RA, Liefers GJ, Mesker WE (2016) Are disseminated tumor cells in bone marrow and tumor-stroma ratio clinically applicable for patients undergoing surgical resection of primary colorectal cancer? The Leiden MRD study. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 39:537–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13402-016-0296-2

Wu J, Liang C, Chen M, Su W (2016) Association between tumor-stroma ratio and prognosis in solid tumor patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 7:68954-68965https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.12135

Zhang R, Song W, Wang K, Zou S (2017) Tumor-stroma ratio(TSR) as a potential novel predictor of prognosis in digestive system cancers: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta 472:64–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2017.07.003

Funding

Marloes Smit and Gabi van Pelt received (partly) financial support from a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF)/Alpe d’HuZes fund (project 2016–10174).

Furthermore, this research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS, RT, HvK and WM contributed to the study conception and design. Data acquisition was performed by MS, GvP, VT and HvK. Statistical analysis was performed by MS and supervised by HP. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MS and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The medical ethics committee of the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) in Leiden (the Netherlands) approved this retrospective cohort study (protocol number B18.052). All data and patient material were handled in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments, and the Code of conduct.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smit, M.A., van Pelt, G.W., Terpstra, V. et al. Tumour-stroma ratio outperforms tumour budding as biomarker in colon cancer: a cohort study. Int J Colorectal Dis 36, 2729–2737 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-021-04023-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-021-04023-4