Abstract

The influence of unit Reynolds number (\(Re_1=17.5\times 10^{6}\)–\(80\times 10^{6}\,\text {m}^{-1}\)), Mach number (\(M= 0.35\)–0.77) and incompressible shape factor (\(H_{12} = 2.50\)–2.66) on laminar–turbulent boundary layer transition was systematically investigated in the Cryogenic Ludwieg-Tube Göttingen (DNW-KRG). For this investigation the existing two-dimensional wind tunnel model, PaLASTra, which offers a quasi-uniform streamwise pressure gradient, was modified to reduce the size of the flow separation region at its trailing edge. The streamwise temperature distribution and the location of laminar–turbulent transition were measured by means of temperature-sensitive paint (TSP) with a higher accuracy than attained in earlier measurements. It was found that for the modified PaLASTra model the transition Reynolds number (\(Re_{\text {tr}}\)) exhibits a linear dependence on the pressure gradient, characterized by \(H_{12}\). Due to this linear relation it was possible to quantify the so-called ‘unit Reynolds number effect’, which is an increase of \(Re_{\text {tr}}\) with \(Re_1\). By a systematic variation of M, \(Re_1\) and \(H_{12}\) in combination with a spectral analysis of freestream disturbances, a stabilizing effect of compressibility on boundary layer transition, as predicted by linear stability theory, was detected (‘Mach number effect’). Furthermore, two expressions were derived which can be used to calculate the transition Reynolds number as a function of the amplitude of total pressure fluctuations, \(Re_1\) and \(H_{12}\). To determine critical N-factors, the measured transition locations were correlated with amplification rates, calculated by incompressible and compressible linear stability theory. By taking into account the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations at the frequency of the most amplified Tollmien–Schlichting wave at transition location, the scatter in the determined critical N-factors was reduced. Furthermore, the receptivity coefficients dependence on incidence angle of acoustic waves was used to correct the determined critical N-factors. Thereby, a found dependency of the determined critical N-factors on \(H_{12}\) decreased, leading to an average critical N-factor of about 9.5 with a standard deviation of \(\sigma \approx 0.8\).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Natural laminar flow (NLF) technology is a functional technology to reduce wall shear stress and fuel consumption of commercial aircraft (Crouch 2015; Fujino et al. 2003). It is implemented on aerodynamic surfaces with zero to moderate sweep angles, where the predominant instabilities leading to transition to turbulence are Tollmien–Schlichting (T–S) waves. In particular, T–S waves are the main instability mechanism for two-dimensional laminar boundary layers developing on smooth surfaces. They are excited via the receptivity process and the initial stage of their amplification can be described by linear stability theory; in a second amplification stage, the T–S waves become unstable to three-dimensional perturbations, described by secondary instability theory. The secondary instabilities lead to the formation of \(\Lambda\)-structures which cause ‘hair-pin’ vortices close to the wall and result in the break down to turbulence (Schlichting and Gersten 2000). This transition process is also referred to as ‘natural’ laminar–turbulent transition which is typical for low freestream disturbance environments, as encountered in flight (Joslin 1998).

However, many conventional wind tunnels have disturbance levels higher than in flight, which can cause the mechanism of ‘natural transition to be changed or bypassed and can lead to discrepancies between transition locations measured in wind tunnels and in flight (Fisher and Dougherty 1982; Michel and Froebel 1988) Results from Meier et al. (1987) indicate that the movement of transition location is not determined by the root mean square (RMS) turbulence level, but instead by the spectral level in the frequency range, in which the T–S waves are most unstable. Therefore, they concluded from their experiments that “the Reynolds number at which the transition onset was detected can be correlated perfectly with the spectral level in the frequency range representative for the Tollmien–Schlichting waves” (Meier et al. 1987).

1.1 Unit Reynolds number effect

The described correlation can be used to explain the so-called ‘unit Reynolds number effect’, which refers to an increase in transition Reynolds number with unit Reynolds number, measured in self-similar boundary layers.Footnote 1 A concise explanation of the unit Reynolds number effect was given by Arnal and Délery (2004) with the words “when the unit Reynolds number increases (for a fixed value of the Mach number), the range of unstable waves shifts to higher frequencies. In the freestream, the energy of the corresponding pressure fluctuations decreases, so that the transition Reynolds number increases”.

1.2 Mach number effect

By the systematic variation of M, \(Re_1\) and \(H_{12}\) in combination with a spectral analysis of freestream disturbances, it was also possible to investigate the so-called ‘Mach number effect’ on laminar–turbulent transition in two-dimensional boundary layers. The Mach number effect refers to a stabilizing effect of compressibility on boundary layer transition, as predicted by linear stability theory: the consideration of compressibility effects in linear stability theory leads to reduced growth rates of Tollmien–Schlichting waves (Arnal and Vermeersch 2011). Under the assumption of a constant critical N-factor (see below) the reduced growth rates will lead to a delay of laminar–turbulent transition (Arnal and Vermeersch 2011). However, in wind tunnel experiments, the stabilizing compressibility effect is opposed by an increased initial amplitude of the T–S waves, due to an increased freestream disturbance level with Mach number (Arnal 1989). Therefore, the direct comparison of transition Reynolds numbers, measured at different Mach numbers, is not meaningful, due to changes in the disturbance spectrum, as shown in Sect. 3.1.

1.3 Transition prediction by the \(e^N\)-method and correction of determined critical N-factors

The \(e^N\)-method is based on linear stability theory (Schlichting and Gersten 2000) and was first published in 1956 (van Ingen 1956; Smith and Gamberoni 1956). Since then, it has been widely used for transition prediction on aircraft surfaces (Hue et al. 2015, 2018; Schrauf 1994, 2000, 2005; Schrauf et al. 1996, 1998; Streit et al. 2011; van Ingen 2008; Voogt 1996). The N-factor method uses growth rates of T–S waves in a laminar boundary layer calculated by linear stability theory and assumes that transition takes place where the most unstable disturbances are amplified by a factor of \(e^N\), where N is assumed to be a universal constant. However, it has been found that the critical N-factor is not a universal constant, but instead depends strongly on the flow conditions (van Ingen 2008). Therefore, it varies for each wind tunnel and model and has to be determined by a semi-empirical method, based on a correlation of stability calculations with experimental data (van Ingen 2008).

It has been concluded, that the major drawback of the \(e^N\)-method, is its implicit assumption that all unstable waves have the same initial amplitude, which is not possible in practical applications due to variations in the external disturbance spectrum and receptivity (Arnal 1989). This observation was succinctly worded by Stetson et al. (1986) who stated that “knowledge of the stability characteristics of a boundary layer is only part of the problem. The external disturbances must be prescribed in order to make boundary layer transition prediction based upon stability considerations”.

To improve the N-factor method Mack (1977) made one of the earliest attempts to take the turbulence level of velocity fluctuations, \(Tu_u = \sqrt{\frac{1}{3}\left( u'^2+v'^2+w'^2\right) }/U_\infty\), into account and corrected the critical N-factor with

For a turbulence intensity of \({0.07}{\%}\) [which is typical of low turbulence subsonic wind tunnels (Michel and Froebel 1988)] Mack’s correlation gives a critical N-factor of \(N_{\text {crit}}=9\). However, it has been found that Mack’s method is most useful at high turbulence levels above \(Tu_u \approx {0.1}{\%}\), while it shows much scatter in low-turbulence environments, as relevant for this study (van Ingen 2008).

The low reliability in low-turbulence environments may be explained by the fact that the RMS turbulence level is not sufficient to describe the disturbance environment. Instead, the spectral level in the frequency range representative for Tollmien–Schlichting waves leading to transition has to be considered as described above.

Besides total pressure fluctuations also static pressure fluctuations have to be considered. However, the static pressure fluctuations in DNW-KRG remain almost constant for the investigated frequency, Mach number and Reynolds number ranges (Koch 2004).

1.4 Compressible and incompressible N-factor analysis

The linear stability analysis, used for the N-factor method, can be carried out either with or without incorporation of compressibility effects (Schrauf 2006). It has been found that critical N-factors exhibit a larger scatter when they are calculated with compressible linear stability theory, than in the case of incompressible linear stability theory (Schrauf 1994, 2000; Schrauf et al. 1998). This observation contradicts the general expectation that a model which incorporates more physical processes (i.e., compressibility effects) produces more consistent results. Therefore, it has been conjectured that compressibility effects in linear stability theory may be compensated by another physical mechanism that leads to less consistent results of the determined compressible critical N-factors (Schrauf 2000).

1.5 Scope of the work

1.5.1 Unit Reynolds number effect

The unit Reynolds number effect has been observed in various hypersonic facilities (Stainback 1967; Stainback et al. 1974; McCauley et al. 1966; Softley et al. 1969) and was carefully investigated by Stetson et al. (1986). However, it has never been investigated in a large subsonic flow regime before, which is most relevant for commercial aircraft today. To examine the unit Reynolds number effect for the transonic Cryogenic Ludwieg-Tube Göttingen (DNW-KRG), a systematic experimental investigation of the influences of unit Reynolds number (\(Re_1 = {17.5\times 10^{6}}\)–\(80\times 10^{6}\,\text {m}^{-1}\)), incompressible shape factor (\(H_{12} = 2.50\)–2.66) and Mach number (\(M = 0.35\), 0.50 and 0.65) on transition Reynolds number was conducted in this study. In DNW-KRG unit Reynolds numbers of up to \(Re_1 = {400\times 10^{6}}\,\text {m}^{-1}\) can be achieved for two-dimensional test models by decreasing temperature down to 100 K and increasing pressure up to 10 bar (Rosemann 1997). In the current study the charge temperature was kept constant at about 283 K, while the charge pressure of the wind tunnel was varied to adjust the unit Reynolds number.Footnote 2 The Mach number of the flow was varied by adjusting the cross section of the sonic throat downstream of the test section (Koch 2004), while a variation of the shape factor was achieved by varying the angle-of-attack of the model (Costantini 2016; Risius et al. 2018). Limitations to the test envelope were due to: (a) the maximal charge pressure of DNW-KRG, which limited the maximal unit Reynolds number, (b) boundary-layer separation downstream of a pressure minimum in the leading-edge area at high angles-of-attack, (c) blockage effects of the model inside the test section at large negative angles-of-attack, which limited the range of examinable pressure gradients (shape factors), and (d) the chord length of the model, which limited the detectable transition location.

Due to the systematic approach, the current work exceeds earlier investigations on the unit Reynolds number effect, as it does not only give a qualitative explanation, but allows a quantitative calculation of the transition Reynolds number as a function of incompressible shape factor and unit Reynolds number for three different Mach numbers.

1.5.2 Mach number effect

Due to the inherent coupling of Mach number and freestream disturbance spectrum the direct comparison of transition Reynolds numbers, measured at different Mach numbers, is not meaningful. However, in this paper it will be shown that a comparison of transition Reynolds numbers, obtained at different Mach numbers, can be conclusive if the total pressure disturbance spectrum is approximated as a function of \(Re_1\), \(H_{12}\) and M and if this approximation is used to express the transition Reynolds number as a function of the incompressible shape factor and of the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations.

1.5.3 Correction of compressible and incompressible critical N-factors

Incompressible and compressible stability theory was employed to calculate critical N-factors for all available Mach and Reynolds numbers. To conduct a correction of the determined critical N-factors, the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations in the frequency range of T–S waves leading to transition was used. It will be shown that this correction leads to a significantly better correlation of the determined compressible critical N-factors.

To correct the influence of acoustic disturbances in the present study, the dependence found by Heinrich et al. (1988) was approximated linearly and used to correct the influence on the determined critical N-factors of the incidence angle of acoustic waves reaching the boundary layer. It was assumed that this incidence angle of the acoustic waves is equal to the angle-of-attack of the model in the wind tunnel.

1.6 Outline of the paper

In the next section of the paper (Sect. 2), the experimental setup, TSP data analysis, boundary layer computations and linear stability calculations are described.

In Sect. 3, first a spectral analysis of total pressure fluctuations, measured in the freestream of the wind tunnel, is presented (Sect. 3.1). Afterwards a method to correct the influence of non-adiabatic surface temperatures on the transition location, is shown (Sect. 3.2). Then, the influence of the incompressible shape factor on transition Reynolds number is approximated linearly for all Mach and unit Reynolds numbers (Sect. 3.3). These relations are used to calculate the transition Reynolds number as a function of the unit Reynolds number with the help of a power law approximation (Sect. 3.4). Afterwards, a function is derived which gives the most amplified frequency of T–S waves at transition location depending on unit Reynolds number and incompressible shape factor (Sect. 3.5). In the last part of Sect. 3, the above relations are combined to give the transition Reynolds number as a function of the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations for both approximations derived (Sect. 3.6). These relations allow a comparison of the transition Reynolds numbers measured at different Mach numbers and, therefore, different total pressure turbulence levels.

In Sect. 4, the determined critical N-factors of incompressible and compressible linear stability theory are presented. The correction of compressible critical N-factors is carried out by correcting initial amplitudes with the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations in the frequency range relevant for T–S induced transition (Sect. 4.1). Furthermore, the receptivity coefficients dependence on incidence angle is used to correct determined critical N-factors (Sect. 4.2).

Measurement uncertainties and repeatability of the results are analyzed and discussed in Sect. 5. In the last parts of the paper the main outcome of the analysis is summarized and discussed (Sect. 6) and finally a conclusion is drawn (Sect. 7).

2 Experimental setup and boundary layer computations

The experimental data presented in this paper originates from six different measurement campaigns of the modified PaLASTra wind tunnel model that were carried out over a time span of two years. Most of the data presented was taken during the first wind tunnel entry, while later measurements, marked as ‘later entry’ (abbreviation: ‘l.e.’), were used only for completion of the data and check of repeatability.

2.1 The Cryogenic Ludwieg-Tube Göttingen

The experiments were performed in the transonic Cryogenic Ludwieg-Tube Göttingen (Rosemann 1997; Koch 2004). The blow down wind tunnel is operated intermittently with gaseous nitrogen as driving gas and has good flow quality. The total temperature turbulence level,Footnote 3 \(Tu_{T_0}\), in the center of the test section, is lower than 0.04% at Mach number \(M = 0.8\), at unit Reynolds number of \(Re_1 = {30\times 10^{6}}\,\text {m}^{-1}\) and a charge temperature, \(T_\text {c} \approx {282}\) K, and it decreases with lower Mach numbers. The mass flux turbulence level3, \(Tu_{\rho u}\), in the center of the test section is approximately \({0.06}{\%}\) at \(M = 0.8\), \(T_\text {c} \approx {283}\) K and \({30\times 10^{6}}< Re_1 < {77\times 10^{6}}\,\text {m}^{-1}\); it increases slightly at lower Mach numbers, but remains smaller than \({0.08}{\%}\) (Koch 2004). To guarantee an interference-free flow around the wind tunnel model, the upper and lower test section walls were adapted (Rosemann 1997). The uncertainties in the inflow Mach and Reynolds numbers in the present work were within \(M =\pm \,0.002\) and \(Re_1=\pm \,{0.25\times 10^{6}}\,{\text {m}^{-1}}\).

2.2 The two-dimensional wind tunnel model PaLASTra

The wind tunnel model used for the present study was the two-dimensional PaLASTra model (Costantini et al. 2015b, 2016a, b; Costantini 2016). On the lower surface of the original PaLASTra model an abrupt contour change was imposed at \(x/c = {80}{\%}\) (Fig. 1) to fix boundary layer separation (Costantini et al. 2016a). However, the large separation region, originating downstream of the original PaLASTra model, leads to strong pressure fluctuations (i.e., acoustic noise) inside the test section; these are likely to increase the initial amplitude of the disturbances within the laminar boundary layer (through the receptivity process) and thus reduce transition Reynolds numbers (Costantini et al. 2016a).

To reduce the separation region, an additional aft part was designed and attached to the original PaLASTra model as shown in Fig. 1. This modification of the model reduces the size of the separation region and the magnitude of the emitted pressure fluctuations. After modification, the separation-induced pressure fluctuations were below the minimum observable quantity of a Kulite pressure transducer (CCQ-093), which was operated at up to 200 kHz and mounted flush with the test section side wall at a location upstream of the model.Footnote 4

A typical pressure distribution on the upper side of the modified PaLASTra model, measured by pressure taps (with 0.25 mm diameter), is shown in Fig. 2. Downstream of the leading edge region with \(x/c>{20}{\%}\), the pressure gradient is essentially uniform on a large portion of the upper surface. Only around \(x/c = {35}{\%}\) the pressure distribution shows some slight variations from an ideally smooth one, due to a model part junction (Costantini et al. 2015b, 2016a; Costantini 2016).

Because T–S waves and the transition position are very sensitive to the surface quality great care was taken to achieve smooth surface conditions. The surface waviness was less than \(h/a \le 0.0025\), where h is half the amplitude of the wave and a corresponds to its quarter wavelength in streamwise direction, thus fulfilling the criteria for allowable waviness for laminar flow (Fage 1943; Gluyas 1967; Carmichael 1959). The model surface was polished to an average roughness of \(R_a = {0.038} {\,\upmu {\text {m}}}\) with a standard deviation of 0.01\({\,\upmu {\text {m}}}\), while the mean roughness depth was \(R_z = {0.32}{\,\upmu {\text {m}}}\) with a standard deviation of 0.11 \({\,\upmu {\text {m}}}\). In the leading edge region the average roughness and mean roughness depth were even further reduced to \(R_a = {0.027}{\,\upmu {\text {m}}}\) and \(R_z = {0.20}{\,\upmu {\text {m}}}\). The step at the model part junction at \(x/c={35}{\%}\) was less than 0.5 \(\,\upmu {\text {m}}\) (Costantini 2016).

Chordwise evolution of pressure coefficient, \(c_\text {p}\), on model upper side at \(Re_1 = {30\times 10^{6}}\,\text {m}^{-1}\), \(M = 0.65\) and an angle-of-attack of \(-\,1.5^\circ\). The measurement uncertainty of the pressure tap measurement leads to an error of \(c_p \lesssim \pm \,0.005\) (not shown in the plot). The flow conditions are the same as in Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8

Non-intrusive global measurement of the surface temperature distribution was carried out using a temperature-sensitive paint (Ondrus et al. 2015). TSP formulation, surface quality, optical setup, acquisition and evaluation of the TSP images were similar to the ones described in Costantini et al. (2016a). Enhancements were made in the data acquisition by installation of new LEDs to illuminate the TSP, leading to an increased temporal resolution and contrast of TSP result images. Furthermore, a new camera setup was developed; it was used during the later entries of the PaLASTra model and increased the spatial resolution, temporal resolution and contrast of the result images even further.

TSP result image where bright and dark areas correspond to laminar and turbulent regions, respectively. The flow direction is from left to right. The whitened strips indicate metallic surfaces of the model where no TSP had been applied. Markers indicating every \({10}{\%}\) chord are visualized by thin white lines. The two turbulent wedges in the mid-span domain are caused by pressure taps in the leading edge region. The red line indicates the detected transition location by the maximal gradient technique at the undisturbed flow locations (Costantini et al. 2016a; Costantini 2016). The flow conditions are the same as in Fig. 2

The transition detection in the current study was conducted by the maximum gradient technique, which has been described by Costantini (2016) and Costantini et al. (2016a). However, it was not only conducted at ten spanwise locations, as in earlier studies (Costantini et al. 2015b, 2016a; Costantini 2016), but in this work it was extended to almost the complete span. Side wall effects, turbulent wedges and significant flow disturbances were excluded from the transition detection, as shown in Fig. 3. The RMS of the variation in transition location along the span was determined for each data point and plotted as an error bar in Fig. 10.

To determine the surface temperature distribution on the upper side of the model, the TSP was calibrated in an external calibration chamber (Egami et al. 2012). Surface temperature distributions in the streamwise direction, which were extracted from the TSP data at five spanwise sections, are shown in Fig. 4.

The described improvements in the measurement technique allowed the determination of transition locations with a higher accuracy than in earlier measurements (Costantini et al. 2012, 2015b, 2016a, b; Costantini 2016) as well as the correction of temperature effects (see Sect. 3.2). These advances made it possible to conduct a systematic analysis of unit Reynolds number, Mach number and pressure gradient effects on transition, as described in Sect. 3.

Left image: the same TSP result image as shown in Fig. 3 with temperature evaluation of TSP (Risius et al. 2018). Red circles indicate the location of thermocouples embedded in the TSP (Costantini et al. 2016a). Right image: temperature distribution measured by TSP (colored lines, correspond to those in left image) and their average (black line) as a function of chordwise coordinate (Risius et al. 2018). The transition location is detected at the maximal temperature gradient at \(x/c \approx {61}{\%}\), marked by a vertical orange line. The flow conditions are the same as in Fig. 2

2.3 Boundary layer computations

Laminar boundary layer computations were performed using the compressible boundary layer solver COCO (Schrauf 1998), which was modified in order to incorporate not only the measured surface pressure but also the measured surface temperature distributions as inputs. Thus, it was accounted for the influence of the non-adiabatic surface temperature on the boundary layer. COCO calculates a fully laminar boundary layer, which was used to determine incompressible displacement (\(\delta _{1}\)) and momentum thickness (\(\delta _{2}\)) of the laminar boundary layer. The average incompressible shape factor,Footnote 5 \(H_{12} = \delta _{1} / \delta _{2}\), was determined by averaging the incompressible shape factor curve between \({24} < x/c < {90}{\%}\) to characterize the boundary layer velocity profile (Fig. 5).Footnote 6 As an alternative to the use of \(H_{12}\) to quantify the influence of the pressure gradient, it is also possible to use the Hartree parameter \(\beta _\text {H}\), based on the average pressure gradient, \(\partial c_p/\partial x\), over the region \({24} < x/c < {90}{\%}\) (see Fig. 5) with (Meyer and Kleiser 1989):

Figure 6 shows the relationship between \(H_{12}\) and \(\beta _\text {H}\), which can be approximated for all Mach and unit Reynolds numbers by \(\beta _\text {H} = -0.687 \cdot H_{12} + 1.810\). The use of \(\beta _\text {H}\) for the quantification of the pressure gradient leads to similar results as the use of \(H_{12}\) (Risius et al. 2018). However, it can be seen from Fig. 6 that the intercept with the y-axis of the linear approximation depends on the Mach number. Furthermore, it should be noted that \(\beta _\text {H}\) is not constant over the complete upper surface (Costantini et al. 2016a). For these reasons, the use of \(H_{12}\) appears more appropriate for the analysis presented in this paper.

The results of boundary layer computations are also plotted as streamwise flow velocity, u, normalized by streamwise velocity at the boundary layer edge, \(u_e\), against the normalized distance from the wall, \(y/\delta _1\), at different chordwise coordinates, x/c (Fig. 7). It can be seen that the upper side of the modified PaLASTra model exhibits a nearly self-similar boundary layer profile downstream of \(x/c = {5}{\%}\) (under the assumption of laminarity over the whole model surface). The same trend was observed for other unit Reynolds numbers. The boundary layer flow developing along the PaLASTra model can be regarded as self-similar for the current investigation.

2.4 Linear stability analysis

The boundary-layer velocity profiles that were calculated with COCO are used to conduct a local linear stability analysis by solving the Orr–Sommerfeld equation, which is a fourth-order differential equation, used to calculate amplification rates of T–S waves (Orr 1907; Sommerfeld 1908). It has been shown that for incompressible two-dimensional flow configurations the two-dimensional perturbations are most unstable (Squire 1933). This assumption, known as Squire’s theorem, is strictly only valid for incompressible flows. However, it has been shown that it is also valid for the flow conditions investigated in this study (Costantini et al. 2015a, 2016a; Arnal 1992). The ratio between the amplitude A at a streamwise position x and the initial amplitude \(A_0\) at the initial position \(x_0\) is given by \(A/A_0 = e^N\), where N is determined by the envelope strategy which uses the most amplified T–S wave at the transition location. Amplification rates of T–S waves for the computed boundary layer were determined by means of LILO (Schrauf 2006). According to linear, local stability theory and the quasi-parallel flow assumption, compressible and incompressible stability computations were carried out and their results were correlated with the measured transition location to assess critical N-factors (Fig. 8). Furthermore, the frequency of the most amplified T–S wave at the transition location, \(f_{\text {tr}}\), was determined.

Distribution of incompressible shape factor, \(H_{12}\), on the model upper side, computed for the same test conditions as in Fig. 2 under the assumption of a completely laminar boundary layer. The continuous green lines at \(x/c = 0.24\) and 0.9 indicate the region where the shape factor was averaged to determine \(H_{12}\), which is used for the further analysis. The average value of \(H_{12}\) is visualized by the green dotted line. For quantification of the measurement uncertainty, the RMS was also determined (as shown in Figs. 10, 15)

Hartree parameter, \(\beta _\text {H}\), as a function of shape factor, \(H_{12}\), for all available Mach numbers [\(M =0.35\) (blue), 0.50 (red), 0.65 (green/yellow) and 0.77 (purple)] and unit Reynolds numbers (\(Re_1={17.5\times 10^{6}}\)–\(80\times 10^{6}\,\text {m}^{-1}\)). The legend is shown in Fig. 22

Streamwise flow velocity, u, normalized by streamwise velocity at the boundary layer edge, \(u_e\), plotted against distance from the wall, y, normalized by incompressible boundary layer displacement thickness, \(\delta _1\), for different chordwise coordinates, x/c. Beyond a chordwise coordinate of about x/\(c = {5}{\%}\) the normalized velocity profile remains almost identical. The flow conditions are the same as in Fig. 2

Compressible N-factors of Tollmien–Schlichting waves from compressible linear stability analysis as a function of normalized chordwise coordinate x/c, computed for the same test conditions as in Fig. 2

The black lines correspond to different amplified frequencies ranging from \(f_{\text {min}} \approx {6}\) kHz–\(f_{\text {max}} = {83}\) kHz. The envelope N-factor curve, indicating the maximal amplification, is marked by a red line. By reading off the maximum amplification at the transition location (blue line at \(x/c \approx 0.6\)) the compressible critical N-factor was determined (\(N_{\text {comp}} \approx 8\)). When maximal possible variations of the transition location (\(\pm {10}{\%}\)) are projected on the N-factor curve (green lines) an uncertainty of about \(N\approx \pm 1\) can be estimated

3 Analysis of stability modifiers

The influences of pressure gradient and unit Reynolds number on transition Reynolds number were analyzed separately for \(M = 0.35\), 0.50 and 0.65. Detailed results will be mainly shown for \(M = 0.35\), while data from the other Mach numbers will be summarized in tables and shown in Figs. 24, 25, 26 and 27 in "Appendix". For better readability, unit Reynolds numbers and transition Reynolds numbers will be normalized, leading to the definition of \(Re_1^* = Re_1/({ 10^{6}}{\,\text {m}})\) and \(Re_{\text {tr}}^* = Re_{\text {tr}}/10^6\), respectively.

In the following analysis, important equations are labeled with roman numbers, to allow easier referencing of the coefficients later on. Slopes are labeled with \(\alpha\) and intercepts with \(\beta\). Coefficients that are used directly in the approximation of the shape factor are labeled with \(h_{i}\), where \(i = 0\), 1, or 2, depending on the degree of \(H_{12}^i\), to which \(h_{i}\) corresponds.

3.1 Spectral analysis of total pressure fluctuations

To quantify flow disturbances relevant for the amplification of T–S waves leading to transition, the normalized spectral level of total pressure fluctuations, \(p^\star = {p_0^{\prime }}/{\bar{p_0}}\), of a measurement conducted by Koch (2004) was reanalyzed. In the log–log plot the frequency dependency of \(p^\star\) was approximated between 390 and 10 kHz by the following relation (shown by black dashed lines in Fig. 9):

To calculate \(\alpha _{\mathrm{I},M}\) and \(\beta _{\mathrm{I},M}\) at any Mach number, the coefficients \(\alpha _{\mathrm{I},M}\) and \(\beta _{\mathrm{I},M}\), measured at \(M = 0.45\), 0.50, 0.55, 0.60 and 0.65 (Koch 2004), were approximated by another set of linear functions, with \(\alpha _{\mathrm{I},M} = 0.036\cdot M-0.458\) and \(\beta _{\mathrm{I},M} = 1.537\cdot M-3.462\), which leads to the following approximation of \(p^\star\):Footnote 7

The approximated coefficients \(\alpha _{\mathrm{I},M}\) and \(\beta _{\mathrm{I},M}\) are summarized in Table 1 and shown by a yellow line for \(M = 0.35\) in Fig. 9.Footnote 8

Power spectrum of total pressure fluctuations of DNW-KRG for different Mach numbers and a unit Reynolds number of \(Re_1= {30\times 10^{6}}\,\text {m}^{-1}\). The measured curves at \(M = 0.50\) (blue) and \(M = 0.65\) (red) were averaged from measurements at \({15}{\%}\) and \({50}{\%}\) test section width [see Fig. 4.37 of Koch (2004)]. The decline of energy at frequencies between \(f_{\text {min}} \approx {10^{2.6}}\,{\text {Hz}}\approx {390}{Hz}\) and \(f_{\text {max}} = {10^{4}}\) Hz was approximated by Eq. (3), as shown by the dashed black lines. The function at \(M = 0.35\) (dashed yellow line) was calculated by Eq. (I). Data is based on Koch (2004)

It can be seen from Fig. 9 that \(p^\star\) increases with Mach number in the investigated frequency range. Therefore, also the RMS total pressure turbulence level increases with M (Koch 2004). This fact prohibits a direct comparison of transition Reynolds numbers measured at different Mach numbers (Risius et al. 2018).

Concerning the unit Reynolds number influences, it has been shown that the total pressure turbulence level (RMS-value) of DNW-KRG increases with unit Reynolds number (Koch 2004). However, the turbulence level growth is exclusively due to an increasing energy of pressure fluctuations at frequencies below 1.5 kHz. When the spectral distribution is analyzed, it can be seen that the energy contained in higher frequencies is independent of the unit Reynolds number and decreases with increasing frequencies (Koch 2004). The described increase of the total pressure turbulence level (RMS-value) is thus only caused by frequencies below the relevant frequency range of Tollmien–Schlichting waves (\({5000}\,{\text {Hz}} \lesssim f_{\text {TS}} \lesssim {30,000}\,{\text {Hz}}\)) and has no relevant influence on the current experiment. Therefore, a spectral distribution of total pressure fluctuations which is independent of unit Reynolds number can be assumed in this analysis.

3.2 Correction of non-adiabatic surface temperature

Due to the working principle of DNW-KRG, the expanding flow leads to a pressure and temperature drop at the beginning of each test run, which causes a temperature difference between the flow and the surface of the model. Therefore, the (non-adiabatic) model surface temperature, \(T_{\text {naw}}\), is generally higher than the adiabatic wall temperature, \(T_{\text {aw}}\), which enhances boundary layer instability and can cause transition to occur further upstream than in the adiabatic case (Boehman and Mariscalco 1976; Costantini et al. 2015b, 2016a; Costantini 2016; Fisher and Dougherty 1982; Liepmann and Fila 1947; Mack 1984; Özgen 2004; Schlichting and Gersten 2000). However, the influence of a non-adiabatic surface temperature on the transition Reynolds number can be corrected (Costantini 2016; Costantini et al. 2016a). To correct the measured non-adiabatic transition Reynolds number, \(Re_{\text {tr,naw}}^\star\), and calculate the adiabatic transition Reynolds numbers, \(Re_{\text {tr}}^\star\), the following approximation is used, based on a linearized fit of the data from Costantini (2016):Footnote 9

Because the temperature difference between non-adiabatic and adiabatic model surface temperature, \(\Delta T = T_{\text {naw}}-T_{\text {aw}}\), is small compared to the adiabatic surface temperature, with \(\Delta T/T_{\text {aw}} \lesssim 0.05\ll 1\) (Costantini 2016), the linearization is valid for all Mach numbers and wall temperature ratios investigated in this study.Footnote 10 The exponent \(\varphi\) was found to take different values, depending on Mach number, with \(\varphi = -\,7\) (for \(M = 0.35\)), \(\varphi = -\,6\) (for \(M = 0.50\)) and \(\varphi = -\,3.5\) (for \(M = 0.65\)) at the original PaLASTra model in DNW-KRG, which may be due to an increase in turbulence level with Mach number (Costantini 2016).

3.3 Influence of shape factor on transition Reynolds number

It was found that the transition Reynolds number increases linearly with a more pronounced favourable pressure gradient, corresponding to a shape factor decrease, which is shown in Fig. 10 for \(M=0.35\). The graphs for \(M=0.50\) and \(M=0.65\) are available in "Appendix". Consequently a linear function

with an intercept, \(h_{\mathrm{II},0}\), and a slope, \(h_{\mathrm{II},1}\), was fitted through each combination of Mach and Reynolds number (shown by solid lines in Fig. 10). The coefficients \(h_{\mathrm{II},0}\) and \(h_{\mathrm{II},1}\) are summarized in Tables 2, 3, respectively. It can be seen that for a fixed value of \(H_{12} \lesssim 2.6\) an increasing unit Reynolds number leads to an increasing transition Reynolds number (Fig. 10, Table 2). Furthermore, an increasing unit Reynolds number leads to a decreasing slope \(h_{\mathrm{II},1}\) (Fig. 10, Table 3).Footnote 11

The transition Reynolds number as a function of the incompressible shape factor, \(H_{12}\), for different unit Reynolds numbers at \(M =0.35\). The vertical and horizontal error bars are RMS values of the transition location variation along the span (Fig. 3) and the chordwise shape factor approximation (Fig. 5), respectively. Black circles mark the calculated transition Reynolds numbers with the help of Eq. (III)

3.4 Influence of unit Reynolds number (\(Re_1^\star\)) on transition Reynolds number (\(Re_{\text {tr}}^\star\))

The approximation of the double logarithmic relation between the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations, \(p^\star\), and the frequency (Eq. 3) motivates the use of a power law approach to approximate the transition Reynolds number as a function of the unit Reynolds number. It is known (Arnal 1989) that in ‘noisy’ hypersonic wind tunnels a power relation exists with

The exponent \(\alpha _{\mathrm{III}}\) is an empirical constant which was found to range between 0.1 and 0.6 for hypersonic flows (Arnal 1989). To find the value of \(\alpha _{\mathrm{III}}\) for PaLASTra in DNW-KRG, the transition Reynolds number was plotted as a function of the unit Reynolds number, calculated with Eq. (II), for different values of \(H_{12}\) in a log–log plot (Fig. 11). In agreement with the hypersonic results, it was found in the present work that \(\alpha _{\mathrm{III}}\) takes values between 0.1 and 0.6 for accelerated flows, depending on Mach number and \(H_{12}\) (also see Fig. 26 in "Appendix"). The dependence of \(Re_{\text {tr}}^*\) on \(Re_{1}^*\) was approximated via

where quadratic functions were used to approximate \(\alpha _{\mathrm{III}}\) and \(\beta _{\mathrm{III}}\) with \(\alpha _{\mathrm{III}} = h_{\mathrm{III},\alpha ,2} \cdot H_{12}^2 + h_{\mathrm{III},\alpha ,1} \cdot H_{12} + h_{\mathrm{III},\alpha ,0}\) and \(\beta _{\mathrm{III}} = h_{\mathrm{III},\beta ,2} \cdot H_{12}^2 + h_{\mathrm{III},\beta ,1} \cdot H_{12} + h_{\mathrm{III},\beta ,0}\). A plot of the approximated quadratic functions is shown in Fig. 12 for \(M=0.35\) (and in Fig. 26 for \(M=0.50\) and \(M=0.65\) in "Appendix"). The coefficients \(h_{\mathrm{III},\alpha ,i}\) and \(h_{\mathrm{III},\beta ,i}\) with \(i = 0\), 1, 2 are summarized in Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

Transition Reynolds number as a function of unit Reynolds number in a double logarithmic plot for different values of \(H_{12}\) at \(M =0.35\). The symbols correspond to transition Reynolds numbers computed with Eq. (II) for \(Re_1^\star = 17.5\), 30, 40 and 50, corresponding to \(\log (Re_1^\star ) \approx 1.24\), 1.48, 1.60 and 1.70, respectively. The approximations are shown by solid lines

Coefficients \(\alpha _{\mathrm{III}}\) and \(\beta _{\mathrm{III}}\) as a function of \(H_{12}\) at \(M =0.35\) with approximations based on quadratic functions with \(\alpha _{\mathrm{III}} = h_{\mathrm{III},\alpha ,2} \cdot H_{12}^2 + h_{\mathrm{III},\alpha ,1} \cdot H_{12} + h_{\mathrm{III},\alpha ,0}\) and \(\beta _{\mathrm{III}} = h_{\mathrm{III},\beta ,2} \cdot H_{12}^2 + h_{\mathrm{III},\beta ,1} \cdot H_{12} + h_{\mathrm{III},\beta ,0}\)

The dependency of the transition Reynolds number on the unit Reynolds number, approximated by the power law approach (Eq. III), is shown for each Mach number in Fig. 13 for constant values of \(H_{12} = 2.51\), 2.54 and 2.59, while the found dependency of \(Re_{\text {tr}}^\star\) on \(H_{12}\) is shown in Fig. 14 for \(Re_1^\star = 10\), 50 and 80. It can be seen that the transition Reynolds number increases with \(Re_1^\star\) and decreases with \(H_{12}\). It can also be seen that the transition Reynolds number decreases with increasing Mach number, mainly because of the increasing level of total pressure fluctuations with Mach number (Sect. 3.1).

Transition Reynolds number, \(Re_{\text {tr}}^\star\), as a function of unit Reynolds number, \(Re_1^\star\), based on the power law approximation (Eq. III) with \(H_{12} = 2.51\), 2.54 and 2.59

Transition Reynolds number, \(Re_{\text {tr}}^\star\), as a function of shape factor, \(H_{12}\), based on the power law approximation (Eq. III) with \(Re_1^\star = 10\), 50 and 80

3.5 Relation between frequency of most amplified T–S wave at the transition location (\(f_{\text {tr}}\)) and the unit Reynolds number (\(Re_1^\star\))

The frequency of the most amplified T–S wave at the transition location, \(f_{\text {tr}}\), was calculated using LILO as described in Sect. 2.3.Footnote 12 In Fig. 15 \(f_{\text {tr}}\) is plotted as a function of the shape factor, \(H_{12}\), for different unit Reynolds numbers. To find the dependency of \(f_{\text {tr}}\) on \(Re_1^\star\) the following analysis was carried out: linear functions were used to approximate the relationship between \(f_{\text {tr}}\) and \(H_{12}\) with \(f_{\text {tr}} = a_{Re_1^\star } \cdot H_{12} + b_{Re_1^\star }\) for each \(Re_1^\star\). The average slope, \(\bar{a} = \frac{1}{n} \Sigma _{Re_1^\star } a_{Re_1^\star }\), was determined and a linear function with the slope \(\bar{a}\) was plotted through the mean values of \(H_{12}\) and \(f_{\text {tr}}\), for each \(Re_1^\star\). These functions were used to find linear relations between \(f_{\text {tr}}\) and \(Re_1^\star\) for selected values of \(H_{12}\). The dependency of \(f_{\text {tr}}\) on the \(Re_1^\star\) can then be written as:

where the coefficient \(\beta _\mathrm{IV}\) was approximated linearly by \(\beta _{\mathrm{IV}} = h_{\mathrm{IV},\beta ,1} \cdot H_{12} + h_{\mathrm{IV},\beta ,0}\). The coefficients \(\alpha _{\mathrm{IV}}\), \(h_{\mathrm{IV},\beta ,0}\) and \(h_{\mathrm{IV},\beta ,1}\) are summarized in Table 6. The dependence of \(f_{\text {tr}}\) on \(Re_1^*\) is visualized in Fig. 16 for a fixed value of \(H_{12} = 2.59\). It can be seen that the unstable frequencies increase linearly with \(Re_1^\star\). The linear increase of \(f_{\text {tr}}\) with \(Re_1^\star\) agrees with expectations from the definition of the dimensionless frequency, F, used in instability computations: \(F=2\pi \cdot f\cdot \nu / u_e^2\) (Arnal et al. 1997; Schlichting and Gersten 2000). This observation is also in agreement with previous results presented in the literature (Masad and Zurigat 1994; Reed et al. 1996; Zurigat et al. 1992). The relationship given in Eq. (IV) can also be expressed with a dimensionless frequency,

which leads to:

The resulting relationship (Eq. IVa) is shown in Fig. 17 and can be approximated by \(F_{\text {tr}} = {1.140\times 10^{-4}}\cdot H_{12} - {2.746e-4}\). Equation (IVa) reveals no dependency on Mach and unit Reynolds numbers since they were integrated into \(F_{\text {tr}}\). However, to perform a combination of the equations, as shown in the next section (Sec. 3.6), it is necessary to express the unit Reynolds number dependency explicitly, as done in Eq. (IV), to eliminate \(Re_1^\star\) in Eq. (III) (see Sect. 3.6.2).Footnote 13 Therefore, dimensional frequencies will be used in the following.

Frequency of the most amplified T–S wave at the transition location as a function of \(H_{12}\) for different values of unit Reynolds numbers at \(M = 0.35\). The same analysis has been carried out and is presented in Fig. 27 of "Appendix" for \(M=0.50\) and \(M=0.65\). Error bars are RMS values of the \(H_{12}\) approximation as shown in Fig. 5. For comparison the black circles show the approximated value of \(f_{\text {tr}}\) with the help of Eq. (IV)

Frequency of the most amplified T–S wave at the transition location as a function of unit Reynolds number for a constant value of \(H_{12} = 2.59\) at \(M =0.35\), \(M =0.50\) and \(M =0.65\). The data of later tunnel entries, which was also used for approximation, is in agreement with data of the first tunnel entry

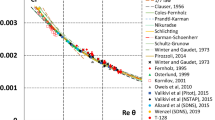

Dimensionless frequency \(F_{\text {tr}}\) of the most amplified T–S wave at the transition location as a function of \(H_{12}\) for all available Mach (\(M = 0.35\) to 0.77) and unit Reynolds numbers (\(Re_1={17.5\times 10^{6}}\,\text {m}^{-1}\) to \(80\times 10^{6}\,\text {m}^{-1}\)). The legend is shown in Fig. 22

3.6 Combination of equations

The equations labeled with Roman numbers can be combined to express the transition Reynolds number as a function of the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations and \(H_{12}\). Therefore, the unit Reynolds number is first expressed as a function of the frequency of the most amplified T–S wave at transition location. Then, the resulting function is inserted into Eq. (III).

Transition Reynolds number, calculated by Eq. (7), is plotted as a function of \(H_{12}\) for a constant value of \(p^\star = 10^{-4.5} \approx {3.162\times 10^{-5}}{}\). \(Re_{\text {tr}}^\star\) decreases with increasing \(H_{12}\) and \(Re_{\text {tr}}^\star\) increases with M

Transition Reynolds number, calculated by Eq. (7), is plotted as function of \(p^\star\) for a constant value of \(H_{12} = 2.54\). \(Re_{\text {tr}}^\star\) decreases with increasing \(p^\star\) and \(Re_{\text {tr}}^\star\) increases with M

3.6.1 Relationship between the unit Reynolds number (\(Re_1^\star\)) and the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations (\(p^\star\))

The relation between unit Reynolds number, \(Re_1^\star\), and the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations, \(p^\star\), for the frequency of the most amplified T–S wave at transition location can be found by combination of Eqs. (IV) and (I) with \(f = f_{\text {tr}}\) and solving for \(Re_1^\star\):

3.6.2 Transition Reynolds number (\(Re_{\text {tr}}^\star\)) as a function of spectral level of total pressure fluctuations (\(p^\star\)) and \(H_{12}\)

To gain the transition Reynolds number as a function of spectral level of total pressure fluctuations Eq. (V) can be inserted into Eq. (III):

Equation (7) is plotted as function of \(H_{12}\) for a constant value of \(p^\star = 1\cdot 10^{-4.5} \approx {3.162\times 10^{-5}}{}\) in Fig. 18. It can be seen from Fig. 18, that the calculated transition Reynolds numbers increases with increasing flow acceleration (corresponding to decreasing \(H_{12}\)).

At a fixed spectral level of total pressure fluctuations (\(p^\star = 10^{-4.5}\)) the transition Reynolds numbers at different Mach numbers can finally be compared: it can be seen that the transition Reynolds numbers increase significantly with Mach number. This observation may be explained by compressibility effects, as predicted by linear stability theory (see Sect. 1.2), which were now isolated.

Transition Reynolds numbers, calculated by Eq. (7), are plotted as function of \(p^\star\) with a constant value of \(H_{12} = 2.54\) in Fig. 19. It can be seen that for all \(p^\star\), shown in Fig. 19, the calculated transition Reynolds numbers also show a significant increase with Mach number, which may also be accounted to compressibility effects.

4 Compressible and incompressible critical N-factors and methods for correction

The critical N-factors were determined for all available data points with compressible and incompressible stability theory and shown in the top graphs of Figs. 20 and 21, respectively. It can be seen that in both cases the determined critical N-factors generally decrease with decreasing \(H_{12}\).

For comparison of the Mach number influence on the determined critical N-factors, the N-factors of the first tunnel entry were analyzed separately for each Mach number and their mean and standard deviation are compared in Table 7. Furthermore, the determined mean critical N-factors are plotted as a function of M in Fig. 23. While the compressible critical N-factors decrease over the whole Mach number range, the incompressible critical N-factors remain almost constant for \(M = 0.50\) and 0.65. Therefore, the standard deviation over all Mach numbers of the compressible critical N-factor is larger than in the incompressible case (see Table 7 last row). However, when the Mach numbers are analyzed separately, the compressible critical N-factors exhibit a smaller variation (standard deviation, \(\sigma\), and maximal variation, \(\Delta N = N_{\text {max}} - N_{\text {min}}\)) than in the incompressible case.

Incompressible critical N-factors, \(N_{\text {inc}}\), \(N_{\text {inc},p^\star }\) and \(N_{\text {inc},p^\star ,C}\) (from top to bottom) as a function of \(H_{12}\) at all available Mach (\(M = 0.35\)–0.77) and unit Reynolds numbers (\(Re_1={17.5\times 10^{6}}\,\text {m}^{-1}\) to \(80\times 10^{6}\,\text {m}^{-1}\)). The legend is shown in Fig. 22

Compressible critical N-factors, \(N_{\text {comp}}\), \(N_{\text {comp},p^\star }\) and \(N_{\text {comp},p^\star ,C}\) (from top to bottom) as a function of \(H_{12}\) at all available Mach (\(M = 0.35\)–0.77) and unit Reynolds numbers (\(Re_1={17.5\times 10^{6}}\,\text {m}^{-1}\) to \(80\times 10^{6}\,\text {m}^{-1}\)). The legend is shown in Fig. 22

To capture the expected increase in initial disturbance amplitude by an increased spectral level of total pressure fluctuations, a correction method of the critical N-factor was developed. The correction method is founded on three basic assumptions of linear stability theory and receptivity (van Ingen 2008):

-

1.

The critical N-factor relates the starting amplitude of the T–S wave, \(A_0\), to the amplitude of the T–S wave at which transition occurs, \(A_{TS,tr}\) (van Ingen 2008):

$$\begin{aligned} N = \ln \left( \frac{A_{TS,tr}}{A_0}\right) = \ln \left( A_{TS,tr}\right) - \ln \left( A_0\right) \end{aligned}.$$(8) -

2.

The Tollmien–Schlichting waves become unstable and lead to transition at a certain amplitude. [Often an amplitude of about \({1}{\%}\) of the freestream velocity, \(A_{TS,tr} \approx 0.01 \cdot U_{\infty }\) is assumed (Herbert 1997; Würz et al. 2012b)].

-

3.

The receptivity process remains unchanged and a linear relation between initial amplitude of the T–S wave, \(A_0\), and the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations, \(p^\star\), exists with \(A_0 \sim p^\star\) (Fuciarelli et al. 2000; Lin et al. 1992; Saric and White 1998; Saric et al. 1999).

4.1 Correction of the critical N-factors with the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations (\(p^\star\)-correction)

A corrected critical N-factor was defined for an arbitrary reference spectral level of \(p^\star _{ref} = {1.5\times 10^{-5}}{}\), in parallel with Eq. (8):

To gain a reference critical N-factor, Eq. (8) was subtracted from Eq. (9). The reference critical N-factor, \(N_{p^\star }\), was then calculated under the assumption of a linear relationship between \(A_0\) and \(p^\star\), with:

The spectral level (\(p^\star\)) corresponding to the critical N-factor was determined by inserting the frequency of the most amplified T–S wave at transition location and the Mach number into Eq. (I).

It can be seen from Fig. 23 and Table 7 that the dependency of the corrected compressible critical N-factor (\(N_{comp,p^\star }\)), exhibits much less variation with Mach number than the compressible critical N-factor without correction. Table 7 also shows that the corrected critical N-factors (\(N_{\text {comp},p^\star }\) and \(N_{\text {inc},p^\star }\)) exhibit smaller standard deviations and maximal variations than the compressible and incompressible N-factors (\(N_{\text {comp}}\) and \(N_{\text {inc}}\)). However, it can also be seen from the plots in the middle of Figs. 20 and 21 that the critical N-factors corrected by the corresponding spectral level (\(N_{\text {comp},p^\star }\) and \(N_{\text {inc},p^\star }\)) still show a dependency on \(H_{12}\). Therefore, the influence of acoustic disturbances is analyzed in the next section.

4.2 Correction of the determined critical N-factors by receptivity dependency of acoustic disturbances on incidence angles (C-correction)

Random fluctuations can be decomposed into three distinct modes: vorticity, sound and entropy (Michel and Froebel 1988; Kovasznay 1953). While the influence of total pressure fluctuations which correspond to non-isentropic variations that constitute the entropy mode, acoustic disturbances, which correspond to isentropic fluctuations, will be investigated in this section. In the following, the dependence of receptivity on the incidence angle of acoustic disturbances is used to correct the determined critical N-factor. The correction method is founded on the following four assumptions:

-

1.

The acoustic disturbances remain constant for the investigated ranges of frequency, Mach and Reynolds numbers.

-

2.

The receptivity of acoustic disturbances depends strongly on the incidence angle by which disturbances are coupled into the boundary layer (Erturk and Corke 2001; Fuciarelli et al. 2000; Goldstein and Hultgren 1989; Haddad and Corke 1998; Hammerton and Kerschen 1996; Heinrich et al. 1988). The receptivity coefficient, C, is defined as the ratio of T–S wave amplitude to acoustic wave amplitude. It increases with increasing incidence angle, \(\theta\), and can be approximated linearly for small angles (Heinrich et al. 1988), with a slope, c, via

$$\begin{aligned} C = 1 + c \cdot \theta \end{aligned}.$$(11) -

3.

Acoustic disturbances in the wind tunnel are assumed to originate mainly from the storage tube. Therefore, they can be assumed to be aligned with the flow direction. Hence, the incidence angle, \(\theta\), is assumed to have the same magnitude as the angle-of-attack of the model, \(\alpha\), with \(\theta = |\alpha |.\)

-

4.

A constant value of \(c = 0.1818/^\circ\) is assumed, which is based on an approximation of results by Heinrich et al. (1988) for a flat plate with sharp leading edge at \(M= 0.1.\)Footnote 14

Based on these assumptions a receptivity corrected N-factor, \(N_{C}\), can be derived in parallel with Eq. (10). Under the assumption of a reference receptivity coefficient, \(C_{\text {ref}} = 1\), these assumptions lead to the following correction:

The N-factor corrections of total pressure fluctuations (Eq. 10) and acoustic disturbances (Eq. 12) can be combined to calculate corrected N-factors, \(N_{p^\star ,C}\), via:

The results are compared in Figs. 20, 21 (bottom) and Table 7. By correcting the angular dependency of the receptivity coefficient, the dependency of the determined critical N-factors on \(H_{12}\) is reduced but not completely eliminated. It can be seen that the corrected compressible N-factors, \(N_{\text {comp},p^\star ,C}\), show the smallest maximal variations.

Comparison of determined mean critical N-factors as a function of Mach number. Compressible critical N-factors, \(N_{\text {comp}}\), decrease with increasing Mach numbers (data from Table 7)

5 Uncertainties and repeatability

This section contains four parts: In the first part, uncertainties of the measured variables are described (Sect. 5.1). In the second part, uncertainties of the transition Reynolds number analysis are discussed (Sect. 5.2), while, in the third part, uncertainties in the analysis of critical N-factors are specified (Sect. 5.3). In the last part of this section, the repeatability for different wind tunnel entries is discussed (Sect. 5.4).

5.1 Uncertainties of measured parameters

The influence of measurement uncertainties of the flow parameters (unit Reynolds number, Mach number, freestream and wall temperatures) are so small that they can be neglected in the current analysis. To quantify the uncertainties in transition Reynolds number and shape factor, their root mean square (RMS) were determined (Sect. 2.2, 2.3), leading to \((Re_{\text {tr}}^\star )_{\text {RMS}} = 0.5\) and \((H_{12})_{\text {RMS}} = 0.01\), which corresponds to relative errors of about 5 and \({0.5}{\%}\), respectively. Based on Figs. 9 and 15, the uncertainties in the spectral level (\(p^\star\)) and in the most amplified frequency at transition location (\(f_{\text {tr}}\)) are estimated to be about \({10}{\%}\).

5.2 Uncertainties in the transition Reynolds number analysis

In the relation between the unit Reynolds number and the transition Reynolds number (Sect. 3.4) where a power law is used (\(Re_{\text {tr}}^* = \left( Re_1^*\right) ^{\alpha _{\mathrm{III}}} \cdot 10^{\beta _{\mathrm{III}}}\) with \(\alpha _{\mathrm{III}}\) and \(\beta _{\mathrm{III}}\) approximated by quadratic functions), variations are about \({5}{\%}\), as shown in Fig. 12.

Further uncertainties are induced by the calculated transition Reynolds number, based on the correction of the non-adiabatic surface temperature (Sect. 3.2): the used coefficients for correction were measured with the original PaLASTra model which induces additional pressure fluctuations inside the test section. The influence of these pressure fluctuations on the transition location is too complex to be quantified, so that the approximations should be checked with the modified PaLASTra model in the future.

Due to large uncertainties in the quantification of (a) nose bluntness and (b) receptivity effects, they were not included in the transition Reynolds number analysis. These effects may lead to further uncertainties in the determined transition Reynolds numbers, which are difficult to estimate. Based on the above discussions, a rigorous error calculus is not possible for the derived equation (Eq. 7), but may be assumed to be in the order of about 10%.

The derived function (Eq. 7) can also be extrapolated to other spectral levels and shape factors; however, this should be done with great caution as it is not based on measurements. Furthermore, it should be noted that the power spectrum of total pressure fluctuations was only measured up to 10 kHz and extrapolated for higher frequencies. In this context, it would of course be useful to extend the measurement to larger measurement ranges, or repeat them with a higher accuracy. Nevertheless, the presented results are an important step to describe the Mach number and unit Reynolds number effect quantitatively.

5.3 Uncertainties in the critical N-factor analysis

Even more difficult is the quantification of uncertainties of the determined critical N-factors, because additionally uncertainties in the receptivity process (discussed in Sect. 6.3.2) and linear stability analysis would have to be considered.

Due to the many unknown factors the description of uncertainties shall be restricted to the found variations in N-factors. When the maximum possible variations of the transition location (\(\pm \, {10}{\%}\)) are projected onto the N-factor curve, an uncertainty of about \(N = \pm \,1\) can be estimated (Fig. 8). Hence, the value of \(\pm 1\) can be seen as a meaningful estimation for the uncertainty of the determined critical N-factors.

At a fixed value of \(H_{12}\) a scatter of the determined critical N-factors between \(\Delta N = 3\) (without corrections) and \(\Delta N = 1.5\) (with corrections applied) was found. When the dependence on \(H_{12}\) is included and all available data points are analyzed, variations between \(\Delta N = 4.9\) (without corrections) and \(\Delta N = 3.5\) (with corrections applied) are found.

In general, it should be emphasized that the scatter of the found N-factors is smaller than in most previous investigations conducted at high Reynolds numbers (Schrauf 1994, 2000, 2005; Schrauf et al. 1996, 1998).

5.4 Repeatability of wind tunnel entries

As mentioned in Sect. 2, the modified PaLASTra model was repeatedly tested in DNW-KRG in six different measurement campaigns over a time span of two years. Between the second entry and later entries the test section of the wind tunnel was consolidated and slightly modified. Also the PaLASTra model was disassembled several times within this time range. However, it can be seen from Figs. 6, 17, 20 and 21, that in general a good repeatability of the results can be found when a sufficient amount of data points are acquired.

6 Discussion of results

In this study the influence of unit Reynolds number, Mach number and pressure gradient (quantified by the incompressible shape factor) on the transition Reynolds number was investigated; these effects will be summarized and discussed in the first part of this section (Sect. 6.1). Furthermore, a correction of the determined compressible and incompressible critical N-factors was carried out as is summarized and discussed in the second part of this section (Sect. 6.2).

6.1 Factors influencing transition Reynolds number

6.1.1 Unit Reynolds number effect

A concise summary of the observed increase of \(Re_{\text {tr}}\) with \(Re_1\) was given by Arnal (1989), who stated that “the relative motion of the environmental disturbances spectrum and of the linearly unstable frequency range can give rise to a strong unit Reynolds number effect”. Arnal also noted that the cause for the unit Reynolds number effect may be a combined response to many factors, such as changes in (a) nose bluntness, (b) the receptivity of the model boundary layer, (c) the freestream disturbance spectrum and (d) the range of potentially unstable frequencies (Arnal 1989).

Based on the factors (c) and (d), Stetson et al. (1986) gave a good schematic explanation of the unit Reynolds number effect with the following words: “With increasing unit Reynolds number, generally it is expected that the frequencies of the most unstable boundary layer disturbances will increase more rapidly than the upper frequency excitation limit of the environment. The result is that disturbances above some frequency may not grow even though they are unstable”.

Founded on the same approach, the unit Reynolds number effect was investigated in this work. However, instead of assuming an upper frequency excitation limit of the environment (like Stetson et al. 1986), in this investigation the excitation intensity of the environment is quantified by the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations. Furthermore, it is not assumed that disturbances above some frequency will not grow at all [as done by Stetson et al. (1986)] instead it is assumed that the initial amplitude of disturbances in the boundary layer varies, depending on Mach number and frequency. With this approach it was not only possible to give a qualitative explanation of the unit Reynolds number effect, but also to describe it quantitatively. To achieve this quantitative description, two approximations were carried out in this paper:

-

1.

The spectral level of total pressure fluctuations was approximated as a function of frequency and Mach number (Eq. I).

-

2.

The dependence of \(Re_{\text {tr}}^\star\) on \(Re_1^\star\) was approximated with the help of a power law approach (Eq. III).

The power law used to quantify the dependence of \(Re_{\text {tr}}^\star\) on \(Re_1^\star\) is given by \(Re_{\text {tr}}^* = \left( Re_1^*\right) ^{\alpha _{\mathrm{III}}} \cdot 10^{\beta _{\mathrm{III}}}\) (Eq. III). The exponents found for accelerated flows (\(\alpha _{\mathrm{III}} = 0.1\)–0.6), agree with findings in hypersonic wind tunnels (Arnal 1989) The coefficients \(\alpha _{\mathrm{III}}\) and \(\beta _{\mathrm{III}}\) were calculated with the help of quadratic approximations, \(\alpha _{\mathrm{III}} = h_{\mathrm{III},\alpha ,2} \cdot H_{12}^2 + h_{\mathrm{III},\alpha ,1} \cdot H_{12} + h_{\mathrm{III},\alpha ,0}\) and \(\beta _{\mathrm{III}} = h_{\mathrm{III},\beta ,2} \cdot H_{12}^2 + h_{\mathrm{III},\beta ,1} \cdot H_{12} + h_{\mathrm{III},\beta ,0}\), for each Mach number separately.

6.1.2 Mach number effect

As discussed in Sect. 1.2, a stabilizing effect of compressibility on boundary layer transition is predicted by linear stability theory. However, an increased initial amplitude of the T–S waves, due to an increased freestream disturbance level, prohibits a direct comparison of transition Reynolds numbers measured at different Mach numbers (Arnal 1989). To allow a comparison of transition Reynolds numbers measured at different Mach numbers, which have a different freestream disturbance level, an additional third approximation was carried out (Sects. 3.5, 6.1.1):

-

3.

The frequency of the most amplified T–S wave at the transition location was approximated as a function of \(H_{12}\) and \(Re_1^\star\) (Eq. IV).

By combination of the above equations (labeled with roman numbers) the unit Reynolds number was eliminated, and the transition Reynolds number was expressed as functions of the freestream disturbance environment, characterized by \(p^\star\), and by the shape factor, \(H_{12}\) (Eq. 7). For a comparison of different Mach numbers, a fixed spectral level of total pressure fluctuations (\(p^\star = 10^{-4.5}\)) or a fixed shape factor (\(H_{12} = 2.54\)) were entered into Eq. (7) and visualized in Figs. 18 and 19. Within the measurement range (\(2\times 10^{-5} \le p^\star \le {5\times 10^{-5}}\) and \(2.51 \le H_{12} \le 2.6\)) the resulting functions show similar trends. It was found that the transition Reynolds number decreases with increasing \(p^\star\) (Fig. 19) and also with increasing \(H_{12}\) (Fig. 18), as expected (Schlichting and Gersten 2000).

Since the different freestream disturbance levels are corrected in Figs. 18 and 19, the transition Reynolds numbers at different Mach numbers can be compared conclusively. It can be seen that the transition Reynolds number increases significantly with Mach number. This result reveals the expected trend of larger Mach numbers leading to larger transition Reynolds numbers at the same freestream disturbance level, the reason being the stabilizing effect of compressibility on T–S waves (Arnal and Vermeersch 2011).

6.2 Calculation and correction of the critical N-factor

The N-factor method is a widely used method for transition prediction on two-dimensional boundary layers (van Ingen 2008). However, large discrepancies have been found in the determined critical N-factors (Schrauf 1994, 2000, 2005; Schrauf et al. 1996, 1998). In the first part of this section, the results of compressible and incompressible critical N-factors are compared and the influences of unit Reynolds number, Mach number and shape factor on \(Re_{\text {tr}}^\star\) are discussed (Sects. 6.2.1, 6.2.2). In the second part, two approaches for the correction of determined critical N-factors, based on the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations (Sect. 6.3.1), and the incidence angle dependent receptivity of acoustic disturbances (Sect. 6.3.2) are summarized and discussed.

6.2.1 Mach number influence on compressible and incompressible critical N-factors

Local linear stability analysis was used to determine critical N-factors with compressible and incompressible theory for all available data points. An average compressible critical N-factor of \(N_{\text {comp}} = 8.50\), with a standard deviation of \(\sigma _{\text {comp}} = 1.14\), and an average incompressible critical N-factor of \(N_{\text {inc}} = 8.99\), with a standard deviation of \(\sigma _{\text {inc}} = 0.95\), were found for PaLASTra in DNW-KRG. When all data points are compared, the maximal variations (\(\Delta N = N_{\text {max}} - N_{\text {min}}\)) show the same trends as the standard deviations: the determined compressible critical N-factor exhibit larger variations (\(\Delta N_{\text {comp}} = 4.90\)) as compared to the incompressible critical N-factor (\(\Delta N_{\text {comp}} = 4.29\)). The same trends have been found by Schrauf (1994, 2000) and Schrauf et al. (1998), who report that critical N-factors calculated with incompressible theory exhibit a better correlation than critical N-factors calculated with compressible theory. The larger fluctuations of compressible critical N-factors are due to their Mach number dependence, as shown in Fig. 23: the compressible critical N-factors decrease with increasing Mach number, which agrees with findings by Schrauf (2000).

At first sight, the observed decrease of compressible critical N-factors with M appears to be contradictory to what one would expect physically: as the compressible N-factor analysis also captures the stabilizing effect of compressibility on the boundary layer, a smaller variation with Mach number would be expected (Arnal and Vermeersch 2011; Schrauf et al. 1996). However, it is very likely that the stabilizing effect of compressibility is compensated by a destabilizing effect of increasing flow disturbances with Mach number (Arnal 1989), which may explain the better correlation of the determined incompressible critical N-factors. Therefore, the influence of pressure fluctuations on the determined critical N-factor is discussed in more detail below (Sect. 6.3).

It is also interesting to note that, if critical N-factors of different Mach numbers are compared separately, as done in Sect. 4, compressible critical N-factors exhibit a smaller standard deviation and a smaller maximal variation than the incompressible critical N-factors (Table 7). This observation is in line with the Mach number dependence as discussed above. Furthermore, it shows that, it is not valid to assume, in general, a better correlation of the incompressible critical N-factor as compared to the compressible critical N-factor. Instead, the influence of the external disturbance spectrum has to be considered and corrected. However, in case the influence of the external disturbance spectrum on the critical N-factor is not corrected, actually incompressible critical N-factors were found to show a better correlation.

6.2.2 Influence of unit Reynolds number on critical N-factors

In a wind tunnel test, as reported by Schrauf (2000), it has been found that compressible and incompressible critical N-factors depend on unit Reynolds number. However, the trends Schrauf (2000) found in the wind tunnel, contradict the trends that were found in flight tests. This observation was explained by an increasing disturbance amplitude of the wind tunnel tests with unit Reynolds number (Schrauf 2000). In the current investigation a slight increase (with a maximum of \(\Delta N \approx 1\)) of the critical N-factor with unit Reynolds number at small \(H_{12}\) was found (see also Figs. 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 and 33 in "Appendix"). However, when all data points were compared (Figs. 20, 21) the trend was not found to be stringent and lies within the measurement accuracy, as discussed below (see Sect. 5.3). This observation can be explained by the fact that the disturbance amplitude of pressure fluctuations in DNW-KRG is independent of unit Reynolds number in the relevant frequency range (see Sect. 3.1).

6.3 Correction of the determined critical N-factors

In Sect. 4 two steps were made to correct the influence of pressure fluctuations on the determined critical N-factors. The first step, which was described in Sect. 4.1, aims to correct the critical N-factor values taking into account the Mach number dependence of the amplitude of freestream total pressure fluctuations whose frequency corresponds to the T–S wave responsible for transition and will be discussed in Sect. 6.3.1. The second step, which was described in Sect. 4.2, focuses on the receptivity dependency of acoustic disturbances, which varies with incidence angle and will be discussed in Sect. 6.3.2.

6.3.1 Correction of total pressure fluctuations

As explained above, it is likely that the found Mach number dependency of the compressible critical N-factors is caused by an increasing spectral level of total pressure fluctuations with Mach number (analyzed in Sect. 3.1). Furthermore, the frequency dependency of the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations is likely to be at least partially responsible for the described influence of unit Reynolds number and shape factor on the determined critical N-factors.

To correct the influence of an increasing level of total pressure fluctuations with Mach number, the compressible and incompressible critical N-factors were corrected by relating the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations to the initial amplitude of the T–S waves linearly (Sect. 4.1). By this correction, the standard deviations and maximal variations were reduced for the incompressible (\(N_{\text {inc},p^\star } = 9.60\pm 0.84\) (4.06)) and compressible critical N-factors (\(N_{\text {comp},p^\star } = 9.11\pm 0.87\) (4.02)).Footnote 15 The improvement in \(\sigma\) and \(\Delta N\) is significantly larger in the compressible case (an average improvement of about \({21}{\%}\)) than in the incompressible case (an average improvement of about \({8}{\%}\)), when all data points are compared. By comparing the \(p^\star\)-corrected critical N-factors, shown in the middle of Figs. 20 and 21, it can be seen that the variation is significantly reduced, compared to \(N_{\text {inc}}\) and \(N_{\text {comp}}\), shown at the top of Figs. 20 and 21.

Furthermore, it should be noted that the correction of the incompressible critical N-factor (\(N_{\text {inc},p^\star }\)) produces new outliers. This observation is also resembled by the (slightly) smaller maximal variation of the compressible case (\(\Delta N_{\text {comp},p^\star } = 4.02\)) compared to the incompressible case (\(\Delta N_{\text {inc},p^\star } = 4.06\)), which is even more significant when Mach numbers are compared individually (Table 7). Therefore, it can be conjectured that the \(p^\star\)-corrected compressible critical N-factors (\(N_{\text {comp},p^\star }\)) capture more of the relevant physical processes leading to transition. In contrast, it can also be conjectured that the incompressible critical N-factors capture in general less physical processes and are, therefore, less suitable for transition prediction when the spectral level of total pressure fluctuations are incorporated.

6.3.2 Correction of the dependence on incidence angle of receptivity of acoustic disturbances

Apart from total pressure fluctuations, also acoustic disturbances have a significant influence on T–S induced transition, as discussed in Sect. 4.2. Since receptivity of acoustic disturbances depends strongly on the incidence angle (which was assumed to correspond to the angle-of-attack), a linear approximation based on calculations of Heinrich et al. (1988) was used to correct the determined critical N-factors.

It was found that the determined critical N-factors, \(N_{p^\star ,C}\), with corrected influence of total pressure fluctuations (\(p^\star\)) and receptivity of acoustic disturbances (C), exhibit the smallest standard deviations (\(\sigma\)) and the smallest maximal variations (\(\Delta N\)) of all cases. The values of \(\Delta N\) and \(\sigma\) are smaller for \(N_{\text {comp},p^\star ,C}\) compared to \(N_{\text {inc},p^\star ,C}\) (except for a slightly smaller standard deviation of \(N_{\text {inc},p^\star ,C}\), when all data points are compared). It can, therefore, be conjectured that the C- and \(p^\star\)-corrected compressible critical N-factors (\(N_{\text {comp},p^\star ,C}\)) capture the most relevant physical processes in this study.

Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the dependence of the C-corrected critical N-factors (\(N_{p^\star ,C}\)) on \(H_{12}\) could be reduced by the employed corrections, but it could not be removed completely. A better cancellation would be possible if a significantly larger dependence of receptivity on the angle-of-attack would be assumed. The slope c in Eq. (11) would be required to be about twenty times larger, which appears to be too large to be reasonable at first sight. However, the assumption that the angle-of-attack is identical with the angle of incidence (assumption 3 of Sect. 4.2) might not be fully valid, since acoustic waves may not be aligned with the flow direction. Furthermore, the receptivity process is still not completely understood and the receptivity coefficients determined in past work have been found to vary by an order of magnitude (Heinrich et al. 1988; Shahriari et al. 2016). Additionally, it must be considered that the freestream disturbances in the experiment might not enter the boundary layer only at the leading edge, but also at discontinuities of the model surface, such as model part junctions (see also Sect. 2.2). Also non-parallel effects, non-linear mechanisms and influences of nose bluntness would need to be considered (Arnal et al. 1997). The knowledge of this missing information would probably further improve the prediction of transition.

In this context it should be emphasized that the concept of a universal critical N-factor is based on the assumption of linear growth of Tollmien–Schlichting waves. However, the transition from laminar to turbulent flow is a non-linear process (Würz et al. 2012a, b). Therefore, the existence of a universal N-factor, which is completely independent of M, \(Re_1\) and \(\alpha\) cannot be expected.

7 Conclusion

The described improvements in the spatial and temporal transition detection method of TSP and the quantitative surface temperature measurement allowed the determination of the transition Reynolds number with a high accuracy. Since the measured surface temperature distribution was also incorporated into boundary layer calculations, it was also possible to account for temperature effects on the N-factor calculation. These advances in the measurement technique allowed the systematic investigation of unit Reynolds number, Mach number and pressure gradient effects on laminar–turbulent transition in two-dimensional boundary layers.