Abstract

β-Glucan phosphorylases are carbohydrate-active enzymes that catalyze the reversible degradation of β-linked glucose polymers, with outstanding potential for the biocatalytic bottom-up synthesis of β-glucans as major bioactive compounds. Their preference for sugar phosphates (rather than nucleotide sugars) as donor substrates further underlines their significance for the carbohydrate industry. Presently, they are classified in the glycoside hydrolase families 94, 149, and 161 (www.cazy.org). Since the discovery of β-1,3-oligoglucan phosphorylase in 1963, several other specificities have been reported that differ in linkage type and/or degree of polymerization. Here, we present an overview of the progress that has been made in our understanding of β-glucan and associated β-glucobiose phosphorylases, with a special focus on their application in the synthesis of carbohydrates and related molecules.

Key points

• Discovery, characteristics, and applications of β-glucan phosphorylases.

• β-Glucan phosphorylases in the production of functional carbohydrates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

β-Glucan phosphorylases (β-GPs) are carbohydrate-active enzymes that catalyze the degradation of β-glucans (β-Gs) with the use of inorganic phosphate, yielding α-d-glucose 1-phosphate (α-G1P) and a shorter carbohydrate chain as products (Fig. 1). Because of the high energy content of the glucosyl phosphate, the reaction is readily reversible and can be used for the synthetic purposes of β-glucans in vitro. In that case, the donor substrate α-G1P serves as a shorter and, more importantly, cheaper version of the UDP-Glc required by the corresponding “Leloir” glycosyltransferases (e.g., β-1,3-glucan synthase) and can be conveniently prepared through the phosphorolysis of cheap and abundant resources like starch or sucrose (De Winter et al. 2011). Interestingly, the donor can even be generated in situ by coupling the action of starch or sucrose phosphorylases and β-GPs in a one-pot reaction (Fig. 1) (Abe et al. 2015; Müller et al. 2017b; Zhong and Nidetzky 2019). In addition to sucrose phosphorylase, β-GPs can simultaneously or consecutively be coupled with β-glucobiose phosphorylases, such as cellobiose or laminaribiose phosphorylase, to enable β-glucan production starting from glucose as an inexpensive acceptor (Fig. 1) (Abe et al. 2015; Müller et al. 2017b; Zhong and Nidetzky 2019). Finally, β-glucan and β-glucobiose phosphorylases can be used for the enzymatic glycosylation of non-carbohydrate acceptors (e.g., drugs) to increase their activity, pharmacokinetic properties, and solubility, or to reduce their toxicity (Desmet et al. 2012; De Winter et al. 2015a; De Winter et al. 2015b).

Example of the coupled reaction by β-glucobiose (cellobiose) phosphorylase, β-glucan (cellodextrin) phosphorylase, and sucrose phosphorylase for cellodextrin synthesis. Adapted from Ubiparip et al. (2020)

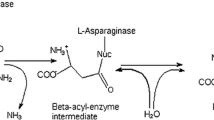

The majority of the known β-GPs are classified in glycoside hydrolase family 94 (GH94), which includes five different phosphorylase specificities (Table 1), as well as cyclic β-1,2-glucan synthase, which has both glycosyl transferase 84 (GT84) and GH94 domains (Lombard et al. 2014; Kitaoka 2015) (www.cazy.org). Recently, glycoside hydrolase families 149 (GH149) and 161 (GH161) have been established (Table 1). They comprise four characterized enzymes that act on β-1,3-linked oligo and polysaccharides (Kuhaudomlarp et al. 2018; Kuhaudomlarp et al. 2019b) (Table 2). Members of all three families utilize the same single displacement mechanism that results in inversion of the anomeric configuration (Fig. 2).

In 2013, Nakai et al. summarized the general use of phosphorylases for oligosaccharide synthesis (Nakai et al. 2013). The last comprehensive review on the diversity of these enzymes and their applications was published in 2015 by Kitaoka (Kitaoka 2015). Since then, the collection of novel β-glucan phosphorylases has expanded significantly, and numerous authors described their use in the synthesis of functional oligosaccharides. To encourage future discoveries involving β-GPs and to emphasize their potential for the easy, sustainable, and cost-friendly synthesis of valuable carbohydrates, we present a comprehensive overview of their features and current applications.

Discovery of β-glucan and β-glucobiose phosphorylases

The earliest work on potential sources, isolation, purification, and characterization of β-glucan phosphorylases was carried out in the 1960s and 70s. The first β-GP was isolated from the versatile phototrophic protist Euglena gracilis (Maréchal and Goldemberg 1963; Maréchal 1967), followed by the extraction and partial purification of another homolog from the unicellular algae Poterioochromonas malhamensis (Table 2) (Kauss and Kriebitzsch 1969). Both enzymes are active on β-1,3-oligoglucans and are, together with the enzyme from Paenibacillus polymyxa, the only known β-1,3-oligoglucan phosphorylases that cannot use glucose as acceptor (Table 2). Today, three different phosphorylase specificities have been described that involve the disaccharide laminaribiose or β-1,3-glucans, i.e., laminaribiose phosphorylase (LBP), β-1,3-oligoglucan phosphorylase (BOP), and β-1,3-polyglucan or laminarin phosphorylase (BGP) (Table 1). Although all can degrade the characteristic β-1,3-glycosidic linkage, they exhibit a different preference for the chain length of their substrate (Nakai et al. 2013; Yamamoto et al. 2013). In the CAZy-classification (Lombard et al. 2014) (www.cazy.org), these enzymes are organized into three distinctive families (GH94, GH149, and GH161), which comprise eight described enzymes (Table 2). The inability of some BOPs and BGPs to use glucose as an acceptor for β-G synthesis can be overcome through coupled reactions with laminaribiose phosphorylases. Two LBPs have been characterized to date. One originates from Acholeplasma laidlawii (Nihira et al. 2012) and the other from Paenibacillus sp. (Kitaoka et al. 2012; Kuhaudomlarp et al. 2019c), with the former displaying a far higher affinity for glucose (Table 2). Most β-1,3-GPs show a fairly broad acceptor specificity, which could diversify their application potential in the carbohydrate industry (Table 2). Their optimal operational temperature ranges from 25 °C for β-GP from Ochromonas danica (OdBGP), up to 75 °C for the homolog from Thermosipho africanus (TaBGP) (Table 2). TaBGP is the only known and well-described thermostable β-1,3-glucan phosphorylase (Kuhaudomlarp et al. 2019a). Interestingly, the enzyme was initially believed to synthesize β-1,4-linkages to yield cellodextrins, but that was later found to be a mistake (Wu et al. 2017). Indeed, structural analysis of the oligosaccharide products revealed that TaBGP is specific to β-1,3-oligosaccharides, and the enzyme was subsequently reclassified into a newly established GH161 family (Kuhaudomlarp et al. 2019a).

Shortly after the discovery of the first β-GP from E. gracilis, a related enzyme that catalyzes the reversible phosphorolysis of cellobiose into α-G1P and glucose was identified (Fig. 1; Table 2) (Alexander 1968). The enzyme was isolated from the cellulolytic bacterium Clostridium thermocellum and designated as cellobiose phosphorylase (CBP). This specificity remains the most studied one in family GH94, with numerous variants, crystal structures, production processes, and engineering studies reported in the scientific literature (Kitaoka 2015). The first cellodextrin phosphorylase (CDP) was discovered a year later in another member of the Clostridium genus (Fig. 1; Table 2) (Sheth and Alexander 1969). CDPs can be used to synthesize longer β-1,4-oligosaccharides or cellodextrins, but cellobiose is typically the shortest carbohydrate that they can recognize as acceptor substrate. The majority of the known cellobiose and cellodextrin phosphorylases originate from the same genus, comprising mainly anaerobic cellulolytic bacteria where these enzymes play a role in a complex multi-enzymatic cluster that enables the utilization of cellulose as a carbon source (Table 2) (Liu et al. 2019). Concerning their biochemical features, most CBPs and CDPs are stable at high temperatures, and their pH optima are in line with those of other known phosphorylases, ranging between 6 and 8 (Table 2) (Ubiparip et al. 2018). Interestingly, both CBP and CDP have the broadest acceptor and donor substrate specificity of all GH94 enzymes, making them suitable candidates for the biocatalytic synthesis of diverse carbohydrates and related molecules (Table 2).

Finally, β-1,2-GPs (sophoro-oligosaccharide-GPs, SOGPs) have been reported, but these specificities are somewhat understudied (Table 2). Quite recently, Nakajima et al. identified the only two representatives known to date, originating from Listeria innocua (LiSOGP) (Nakajima et al. 2014) and Lachnoclostridium phytofermentans (LpSOGP) (Nakajima et al. 2017). Both enzymes are classified in GH94 and have a relatively narrow substrate specificity with low affinities for natural β-1,2-oligosaccharide acceptors (Km ≥ 6 mM) (Table 2). In contrast to the β-1,3- and β-1,4-GPs, no thermostable β-1,2-glucan phosphorylase has been identified so far (Table 2).

While linear β-1,6-glucans (from Umbilicaria pustulata) (Barreto-Bergter and Gorin 1983) and their O-acetylated (from Gyrophora esculenta, Lasallia papulosa, Sticta sp.) (Shibata et al. 1968; Da Silva et al. 1993), and malonic ester forms (from Penicillium luteum) (Anderson et al. 1939) can be found in nature, the corresponding β-glucan phosphorylases have yet to be discovered.

β-Glucan phosphorylases in β-glucan synthesis

β-Glucans are polysaccharides consisting of β-d-glucose monomers linked by β-1,2, β-1,3, β-1,4, or β-1,6 glycosidic linkage that show a diverse range of physicochemical properties depending on the source, type of glycosidic bond, and the length of the polysaccharide chain (Fig. 3).

Characteristic structures of several β-glucans. a β-Glucans originating from cereals contain a mixture of β-1,4 and β-1,3 linkages, typically β-1,3-linked cellotriosyl or tetraosyl blocks, b β-glucans originating from fungi contain a characteristic linear β-1,3 backbone, branched with β-1,6 linkages, c the structure of linear β-1,2-, d β-1,3-, and e β-1,4-oligosaccharides, which can respectively be synthesized by SOGP, BGP/BOP, and CDP

Most of the β-glucans produced on a commercial scale today are extracted from the cell walls of yeasts, fungi, and plants, although some are synthesized by fermentation (Zhu et al. 2016; Liang et al. 2018). The purified β-Gs are typically obtained by acidic hydrolysis steps, followed by selective precipitation using organic solvents (Shi 2016; Zhu et al. 2016). The extraction process and biological origin of β-Gs lead to significant variations in their physicochemical and functional properties, including their branching pattern, molecular weight distribution, viscosity, and concentration in the biological matrix (Zhu et al. 2016).

Enzymatic production processes would likely provide tighter control over the product composition while also eliminating the need for organic solvents. Although certain glycosyltransferases are specialized in the synthesis of β-Gs (Douglas 2001), the high cost of their nucleotide-activated donor sugars is a serious limitation for their commercial exploitation (Mikkola 2020). Due to their ability to use the easily accessible donor α-G1P, β-glucan phosphorylases seem better suited for cost-effective industrial use.

β-1,2-Glucan phosphorylases

In nature, β-1,2-glucans are produced by bacteria and play an important role in the invasion and immunomodulation of infected mammalian or plant cells (Zhang et al. 2016). Furthermore, the β-1,2-linked disaccharide sophorose is a potent inducer of cellulase gene expression in the host Trichoderma reesei (Sternberg and Mandels 1979). Sophorose can be easily isolated and purified as a side product during commercial sophorolipid production by the yeast Candida bombicola (Claus and Van Bogaert 2017). These sophorolipids can serve as biosurfactants in, for instance, biological detergents and are known to have antibacterial, antifungal, spermicidal, and virucidal activities (Geys et al. 2014).

Two authors described the synthesis of β-1,2-glucans on a small scale using the β-1,2-oligoglucan phosphorylase from Listeria innocua (LiSOGP) (Nakajima et al. 2014). In comparison with the enzyme from Lachnoclostridium phytofermentans (LpSOGP), LiSOGP has a higher affinity for β-1,2-oligosaccharides as acceptors and might be more suitable for β-1,2-G synthesis, though its catalytic efficiency is somewhat lower (Table 2). For example, 167 g of β-1,2-G could be obtained through a coupled reaction with sucrose phosphorylase from Bifidobacterium longum in a 1 L reactor starting from 1 M sucrose, 0.5 M glucose, and 0.1 M inorganic phosphate (Abe et al. 2015). The current bottleneck in β-1,2-G production is the low affinity of β-1,2-GPs for glucose. Indeed, the enzyme has a strong preference for sophorose, but this substrate is too expensive to justify its use in large-scale productions (Table 2) (Nakajima et al. 2014; Nakajima et al. 2017). To overcome those drawbacks, a three-step process was designed (Kobayashi et al. 2019). First, β-1,2-gluco-oligosaccharides were generated from a very small amount of sophorose (20 μg) by the combined action of sucrose phosphorylase, β-1,2-glucanase, and LiSOGP. This reaction was sequentially repeated two more times in increasing volumes, each time using the product from the previous reaction as an acceptor substrate. After the third and final cycle, 140 g/L of β-1,2-glucan was obtained on a 1 L scale (Kobayashi et al. 2019). The discovery or engineering of SOGPs with higher thermostability and affinity towards glucose, as well as additional synthesis of β-1,2-glucans, is expected to facilitate investigation of their physiological functions, physicochemical properties, and their use as functional carbohydrates.

β-1,3-Glucan phosphorylases

β-1,3-Glucans draw considerable attention for their proven beneficial effects on immunomodulation, cholesterol levels, and glycemic control, and their use as additives in food or moisturizing personal care products (Rahar et al. 2011; Nie et al. 2018; Vetvicka et al. 2019). In the USA, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA, 1997, 2003) has allowed a heart health claim for products containing β-Gs from oat or barley, typically comprised of mixed β-1,3:1,4-linkages (Fig. 3). The EU approved the health claim related to the regular consumption of these β-Gs for the maintenance of normal blood cholesterol levels and the reduction of blood glucose increase after the meal (Sibakov et al. 2012). Currently, there are various commercial β-glucan-containing food products already on the market, such as Glucagel (Morgan and Ofman 1998), Oatrim (Greenway et al. 2007), and Viscofiber (Colla et al. 2018), where β-Gs from oat and barley serve as functional additives, fat replacers, or aid in weight loss. Moreover, the disaccharide laminaribiose has prebiotic properties (Kumar et al. 2020) and is a powerful germination agent (Jamois et al. 2008).

The first enzymatic production process of laminari-oligosaccharides from glucose and α-G1P was reported in 1991, more than 20 years after the enzyme’s discovery, using EgBOP crude cell extract (Kitaoka et al. 1991b). The authors showed that the concentration of glucose could be used to control the product’s degree of polymerization (DP) since the average DP of laminari-oligosaccharides was 1.8 with 100 mM glucose, while the reaction with 5 mM glucose yielded a product with an average DP of 8.4 (Kitaoka et al. 1991b). In 1992, a first patent was submitted describing a similar process to obtain laminari-oligosaccharides of DP2-4 using Euglena cell extracts (Ito et al. 1994), followed by another that made use of a thermotolerant laminaribiose phosphorylase from the Bacillus genus (Mitsuyoshi et al. 2001). More recently, Yamamoto and co-workers reported the production and characterization of BGP from Ochromonas danica (Yamamoto et al. 2013). The enzyme was also biochemically characterized and could phosphorolyze β-1,3-linked oligo- and polysaccharides but not the disaccharide laminaribiose (Table 2). Similarly, glucose does not serve as an acceptor in the synthetic reaction (Yamamoto et al. 2013). The results of this research led to a patent describing the operating conditions for the manufacture of β-1,3-glucans of different degrees of polymerization (Isono et al. 2013). In 2017, it was reported that laminaribiose could be generated from sucrose and glucose, using EgBOP and sucrose phosphorylase (Müller et al. 2017b). The covalent immobilization of cell extract of Euglena gracilis on Sepabeads EC-EP/S resulted in a high retained activity of EgBOP (65%) and 14 g/L of laminaribiose (Müller et al. 2017b). The method was further improved by combined immobilization and entrapment in chitosan, allowing complete preservation of the enzymatic activity after 12 reuses (Müller et al. 2017a; Müller et al. 2017b). Coupling of this hybrid-immobilization with reaction-integrated laminaribiose extraction by adsorption on zeolites yielded 32 g/L of laminaribiose (Müller et al. 2017a). Another system made use of a packed bed reactor to immobilize EgBOP and sucrose phosphorylase, enabling the production of 0.4 g/(L·h) of laminaribiose (Abi et al. 2018). The system was operationally stable during 10 days of processing, and both enzymes exhibited a half-life time of more than 9 days (Abi et al. 2018). Combined with integrated downstream processing by zeolites, it led to the production of over 0.5 g of laminaribiose per 1 g of sugar used as a substrate (Abi et al. 2019). A simplified preparation method of linear water-insoluble β-1,3-glucans of DP30, using sucrose phosphorylase and EgBOP cell extract, led to a reaction system that requires only 0.1 mM glucose, 200 mM sucrose, and 20 mM phosphate as substrates (Ogawa et al. 2014). Thanks to its low solubility in water, approximately 1 mg/mL of glucan was conveniently isolated by precipitation (Ogawa et al. 2014). Finally, the production of EgBOP in bioreactor has been optimized as well, resulting in around 2-fold higher activity compared to the flask cultivation, thus facilitating future applications of this enzyme in laminaribiose and β-Gs synthesis (Abi et al. 2017).

β-1,4-Glucan phosphorylases

Cellulose or insoluble β-1,4-glucan is the major polysaccharide found in nature with an essential role as a structural polymer and material, while soluble cellodextrins of DP ≤ 6 have promising applications as nutritional ingredients, excipients in medicines, and texturizers in cosmetics (Sakamoto et al. 2017; Putta et al. 2018; Brucher and Häßler 2019; Zhong and Nidetzky 2019). Such soluble cellodextrins were proven to be useful dietary fibers and prebiotics (Otsuka et al. 2004; Pokusaeva et al. 2011) that stimulate the growth of a number of healthy human gut bacteria more efficiently than inulin, trans-galacto-oligosaccharides, and cellobiose alone (Zhong et al. 2020b).

Well-researched enzymatic pathways for cellulose synthesis mostly involved trans-glycosylation by glycoside hydrolases and synthesis by glycosynthases (Kitaoka 2015; O’Neill and Field 2015; Nidetzky and Zhong 2020). Samain and co-authors described the synthesis of crystalline cellulose II by CDP from Clostridium thermocellum using 2.5 mM cellobiose and 100 mM α-G1P (Samain et al. 1995). Years later, an alternative route starting from 50 mM glucose and 200 mM α-G1P was reported (Hiraishi et al. 2009). The average DP of cellulose in both studies ranged from 8 to 10, suggesting that CDP cannot elongate precipitated cellodextrin chains. Others later succeeded in producing cellulose with increased chain length (DP ≤ 14) by using very low concentrations of cellobiose (0.2 mM) (Petrović et al. 2015). Nonetheless, several authors have described the use of cellulases that, under specific conditions, can elongate chains to DP ≥ 100 and, therefore, could represent better biocatalysts for cellulose synthesis than CDP (Kobayashi et al. 1991; Egusa et al. 2007; Egusa et al. 2009; Egusa et al. 2010).

Nippon Petrochemicals and the National Food Research Institute in Japan were the first to patent the cellobiose production process (Kitaoka et al. 1991a). It was synthesized from 200 mM sucrose by the combined one-pot action of glucose isomerase and sucrose and cellobiose phosphorylase resulting in a yield of around 70% (relative to the concentration of donor substrate) (Kitaoka et al. 1991a). The synthesis of cellobiose from starch in a two-step reaction using α-glucan-phosphorylase from a rabbit muscle and cellobiose phosphorylase from Cellvibrio gilvus resulted in a relatively low yield of 24% (Suzuki et al. 2009). Pfeifer & Langen (Germany), one of the largest sugar manufacturers in Europe, developed a process to synthesize cellobiose from 750 mM sucrose in a one-pot reaction using sucrose phosphorylase from Bifidobacterium adolescentis (BaSP) and an engineered CBP variant from Cellulomonas uda (CuCBP) that resulted in 70% yield (Brucher and Häßler 2019). The cellobiose was subsequently purified by ultrafiltration for the separation and recycling of the enzymes and electrodialysis to recover phosphate and α-G1P, and finally, pure cellobiose was obtained by crystallization. Moreover, upscaling of the process was initiated by Savanna Ingredients GmbH (Germany) to about 100 tonnes per year (Brucher and Häßler 2019). Both the production process (Koch et al. 2016) and the CuCBP variant (Koch et al. 2017) have been protected by a patent. Despite its promising applications as prebiotic and texturizer in food and feed products, cellobiose still requires approval as “Novel Food” by EFSA, the European Food Safety Authority (Brucher and Häßler 2019).

Several studies reported CDP catalyzed synthesis of soluble cello-oligosaccharides at the milligram scale. However, these studies were not envisaged for the efficient cellodextrin synthesis in terms of yields or high product concentrations (Samain et al. 1995; Zhang and Lynd 2006; Nakai et al. 2010). Recently, there has been an increasing interest in tailoring the bottom-up synthesis of soluble cellodextrins using CDPs as a cost-effective and ecologically friendly tool (Nidetzky and Zhong 2020). Zhong and co-authors obtained 36 g/L of soluble cellodextrins (DP3-6) from acceptor glucose using CDP from Clostridium cellulosi coupled with CuCBP (Zhong et al. 2019). Moreover, a three-enzyme glycoside phosphorylase cascade was developed by introducing the BaSP for in situ generation of α-G1P, which lead to 40 g/L of soluble cellodextrins produced (Zhong and Nidetzky 2019). Finally, an efficient synthesis of 93 g/L of soluble cellodextrins was demonstrated. The final product consisted of DP3, DP4, DP5, and DP6 with a distribution of 33, 34, 24, and 9 wt%, respectively, a purity of over 95%, and a yield of 88% (Zhong et al. 2020b). We previously described the synthesis of predominantly cellotriose from both glucose and cellobiose by using a cellobiose phosphorylase variant (Ubiparip et al. 2020). Facilitated synthesis of cellodextrins from glucose will certainly unlock further application studies, especially related to the use of these carbohydrates as food and feed additives.

It should be mentioned that β-glucan phosphorylases could also be employed to degrade β-glucans by phosphorolysis and produce α-G1P using inorganic phosphate as co-substrate, but their role in carbohydrate synthesis is industrially more valuable. Though α-G1P alone can be used as a substitute for inorganic phosphate in parenteral nutrition and as a supplement in medical conditions that involve phosphate deficiency, there is a limited need for it as a fine chemical (Ronchera-Oms et al. 1995; Luley-Goedl and Nidetzky 2010). Moreover, other enzymes such as α-glucan phosphorylases can be used for the same purpose and are active on cheaper and easily accessible substrates such as starch and maltodextrins (Ubiparip et al. 2018). As described, sucrose phosphorylase was already successfully exploited in various coupled reactions to produce α-G1P in situ, which subsequently served as a substrate for β-glucan synthesis (Abe et al. 2015; Müller et al. 2017b; Zhong and Nidetzky 2019).

β-Glucan and β-glucobiose phosphorylases as promiscuous biocatalysts

Most (β-glucan) phosphorylases show promiscuity towards various alternative donors and/or acceptors (Table 2) (Singh et al. 2020). For example, the cellodextrin phosphorylase from Clostridium thermocellum was shown to successfully utilize anomeric phosphates of xylose (Shintate et al. 2003), galactose (Tran et al. 2012), and glucosamine (O’Neill et al. 2017), although only a single monomer could be added to the acceptor substrate in these cases (Singh et al. 2020). In turn, a variety of sugar phosphates (of glucose, galactose, glucosamine, and mannose) could be offered to the β-1,3-oligoglucan phosphorylase Pro_7066 for the synthesis of new-to-nature analogs of human milk oligosaccharides (HMO) (Singh et al. 2020). These studies highlighted the innate ability of β-glucan phosphorylases to synthesize smaller glycans (Singh et al. 2020). Although the kinetic efficiencies of these processes are frequently over 100-fold lower than those of their natural reaction, they enable single turnover that is not typical for the enzymes naturally prone to build carbohydrate polymers (Singh et al. 2020).

Similar to CDP, the related cellobiose phosphorylases also have a broad acceptor and donor specificity (Table 2) and can be used in a number of alternative production processes that go beyond cellobiose synthesis. The first described CBP from Clostridium thermocellum was found to be active on a wide range of d- and l-glycosyl acceptors: d-glucose, 2-deoxyglucose, 6-deoxyglucose, d-glucosamine, d-mannose, d-altrose, l-galactose, l-fucose, d-arabinose, and d-xylose (Alexander 1968). Moreover, the enzyme successfully catalyzed the synthesis of a range of β-glucosides when adding solvents as reaction additives since disaccharide phosphorylases typically have a very low affinity for non-carbohydrate acceptors (De Winter et al. 2015b). Cellobiose phosphorylase from Cellvibrio gilvus was also successfully tested against 1,6-linked disaccharides (melibiose, gentiobiose, and isomaltose) as acceptors resulting in the corresponding β-1,4-capped trisaccharides (Percy et al. 1998).

Regarding β-1,3-glucan and glucobiose phosphorylases, BOP from Euglena gracilis and LBP from Paenibacillus sp. were shown to have the broadest acceptor specificity (Table 2). Laminaribiose phosphorylase from Paenibacillus sp. was able to use the alternative donor α-d-mannose 1-phosphate for the synthesis of mannosyl-β-1,3-glucose disaccharide (Kuhaudomlarp et al. 2019c). Moreover, the enzyme showed activity on various alternative acceptors, including mannose, methyl β-glucoside, 2-deoxyglucose, and 6-deoxyglucose, albeit with a 50- to 100-fold reduction in activity (Table 1) (Kitaoka et al. 2012). Laminarin phosphorylase from Poterioochromonas malhamensis could not use the alternative donor substrates glucose-1,6-diphosphate, fructose-l-phosphate, and fructose-1,6-diphosphate (Albrecht and Kauss 1971).

From all β-GPs reported so far, SOPGs have the narrowest substrate specificity, being highly specific to β-1,2-linked oligosaccharides (Table 2) (Nakajima et al. 2014; Nakajima et al. 2017). While α-G1P was the only sugar 1-phosphate used as a donor by LiSOGP, the enzyme showed some activity only on acceptors laminaribiose and glucose to, presumably, synthesize long-chained polysaccharides (Nakajima et al. 2014). Other monosaccharides such as mannose, galactose, xylose, fructose, N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetylgalactosamine, as well as a range of disaccharides (sucrose, maltose, lactose, cellobiose, etc.) were not utilized (Nakajima et al. 2014). Similarly, LpSOGP showed only limited synthetic activity on laminaribiose, while no synthetic or phosphorolytic activity was observed on other tested substrates (Nakajima et al. 2017).

Engineering of β-glucobiose and β-glucan phosphorylases

Relatively narrow substrate specificity prevents wide-range applications of disaccharide phosphorylases for glycoside synthesis (De Groeve et al. 2010a). Nonetheless, cellobiose and laminaribiose phosphorylase can be used for β-glucosylation or β-galactosylation of various molecules (Table 2) (De Groeve et al. 2010a; De Winter et al. 2015b). Lower affinity, acceptor and donor specificity, or specific activity of these enzymes related to non-natural substrates could be improved via enzyme engineering.

A decade ago, the acceptor specificity of CBP from Cellulomonas uda was successfully expanded through random mutagenesis. A double mutant (T508I/N667A) that no longer required a glucosyl acceptor with a free anomeric hydroxyl group and, hence showed some activity on cellobiose as acceptor was slightly improved (0.113 U/mg) by three additional mutations (N156D, N163D, and E649G) (De Groeve et al. 2010b). Most recently, it was determined that the mutant enzyme synthesizes mostly cellotriose with both glucose and cellobiose as acceptors (Ubiparip et al. 2020). The finding became particularly interesting since cellotriose was shown to be the most potent prebiotic among soluble cellodextrins (DP2-6) when tested against bifidobacteria of the human gut (Pokusaeva et al. 2011). The addition of M52R substitution improved the variant’s kinetic properties for the acceptor cellobiose and slightly increased the cellotriose yield (Ubiparip et al. 2020). This study was the first to demonstrate the possibility of controlled, bottom-up, enzymatic synthesis of cellodextrins with a specific degree of polymerization. In addition, the created CuCBP variants showed activity on a range of alternative substrates (De Groeve et al. 2010b). The T508I and N667A mutations resulted in a 10-fold increase of lactose phosphorolysis by CuCBP, which can be used to synthesize α-galactose 1-phosphate from the cheap and ample substrate lactose (De Groeve et al. 2010b). Quite recently, CuCBP has been engineered to tolerate high substrate concentrations required by the industry in a coupled reaction process with CuCBP and BaSP. The variant contained eleven mutations (Q161M, R188K, D196N, A220L, L705T, Y164F, K283A, A512V, F164Y, S169V, and T788V) and showed greatly improved activity for the synthesis of cellobiose at higher substrate concentrations of up to 750 mM α-G1P and glucose, which in turn allowed efficient production of cellobiose in a one-pot reaction starting from 750 mM sucrose (Brucher and Häßler 2019). The Y47H substitution in the CBP from the yeast Saccharophagus degradans and the bacterium Cellulomonas gilvus significantly improved cellobiose consumption in the presence of xylose, a known inhibitor of the cellobiose phosphorylase, which is synthesized during enzymatic plant-biomass degradation (Chomvong et al. 2017). Finally, the stability of CBP from Clostridium thermocellum was increased by combining eight mutations (R48R, Q130H, K131Y, K142R, S411G, A423S, V526A, and A781K), therefore extending the enzyme’s inactivation halftime at 70 °C from 8 to 25 min (Ye et al. 2012).

Contrary to the engineering of CuCBP, single-point mutagenesis of CDP from Clostridium cellulosi did not result in a change of the enzyme’s preference to synthesize specific cellodextrins, most probably due to its broader active site (Ubiparip et al. 2020). The creation of the C485A, Y648F, and Y648V mutants of the CDP from Ruminococcus albus resulted in the higher preference for d-glucosamine, more rapid synthesis of 4-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-d-mannose, and synthetic activity on 4-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, respectively (Hamura et al. 2013). Since most CDPs have a low affinity for poorly soluble cellodextrin acceptors (Table 2), future engineering efforts might be directed towards decreasing the Km for cellobiose or enabling the effective usage of more affordable acceptor glucose.

To this point, no authors described the engineering of the β-1,2- or β-1,3-(oligo)glucan phosphorylases. Recently solved crystal structures of both specificities are expected to encourage engineering efforts on these enzymes (Table 2) (Nakajima et al. 2017; Kuhaudomlarp et al. 2019b).

Conclusions and perspectives

Since the discovery of the first β-glucan phosphorylase over half a century ago, several new specificities have been identified, including LBP, BGP, and SOGP during the last decade. Elucidation of the first crystal structures of CDP, BOP, and SOGP has recently also been achieved. The cumulative research interest in β-glucan and glucobiose phosphorylases has led to biosynthetic routes for laminaribiose, cellobiose, soluble cellodextrins, as well as β-1,2- and β-1,3-glucans. Increasingly, these enzymes are recognized as valuable biocatalysts for the production of such carbohydrates, which can be used as ingredients and additives in the food, feed, and cosmetic industry. A prime example is the development and scale-up of a process for the production of cellobiose by Pfeifer & Langen and Savanna Ingredients GmbH.

Although a number of β-glucan and glucobiose phosphorylases have been characterized so far, future studies could focus on the discovery of novel specificities such as β-1,6-glucan and β-1,6- or β-1,2-glucobiose phosphorylase. Undoubtedly, the biotechnological potential of these phosphorylases will continue to rise in the coming years. Enzyme engineering could lead to new and improved variants, as already demonstrated by the example of the cellobiose phosphorylase from Cellulomonas uda. The research focused on fine-tuning of operating conditions could result in industrially relevant and scalable production processes, which could, in turn, allow in-depth characterization of the properties and applications of the β-glucan products. Further investigations of the structure-function relationships of both β-glucan phosphorylases as well as the synthesized β-glucans will go hand in hand and lead to the upcoming commercialization of both β-GPs and β-Gs. Finally, these developments could result in the production of healthier carbohydrates (i.e., functional foods), now more relevant than ever due to the global rise in obesity and related health problems.

References

Abe K, Nakajima M, Kitaoka M, Toyoizumi H, Takahashi Y, Sugimoto N, Nakai H, Taguchi H (2015) Large-scale preparation of 1,2-β-glucan using 1,2-β-oligoglucan phosphorylase. J Appl Glycosci 62:47–52. https://doi.org/10.5458/jag.jag.jag-2014_011

Abi A, Müller C, Jördening HJ (2017) Improved laminaribiose phosphorylase production by Euglena gracilis in a bioreactor: a comparative study of different cultivation methods. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng 22:272–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12257-016-0649-8

Abi A, Wang A, Jördening HJ (2018) Continuous laminaribiose production using an immobilized bienzymatic system in a packed bed reactor. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 186:861–876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-018-2779-2

Abi A, Hartig D, Vorländer K, Wang A, Scholl S, Jördening HJ (2019) Continuous enzymatic production and adsorption of laminaribiose in packed bed reactors. Eng Life Sci 19:4–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/elsc.201800110

Albrecht GJ, Kauss H (1971) Purification, crystallization and properties of a β-(1→3)-glucan phosphorylase from Ochromonas malhamensis. Phytochemistry 10:1293–1298. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9422(00)84330-7

Alexander JK (1968) Purification and specificity of cellobiose phosphorylase from Clostridium thermocellum. J Biol Chem 243:2899–2904. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)93356-9

Anderson CG, Haworth WN, Raistrick H, Stacey M (1939) Polysaccharides synthesized by micro-organisms: the molecular constitution of luteose. Biochem J 33:272–279. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj0330272

Barreto-Bergter E, Gorin PAJ (1983) Structural chemistry of polysaccharides from fungi and lichens. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem 41:67–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2318(08)60056-6

Bianchetti CM, Elsen NL, Fox BG, Phillips GN Jr (2011) Structure of cellobiose phosphorylase from Clostridium thermocellum in complex with phosphate. Acta Crystallogr Sect F 67:1345–1349. https://doi.org/10.1107/S1744309111032660

Brucher B, Häßler T (2019) Enzymatic process for the synthesis of cellobiose. In: Vogel A, May O (eds) Industrial enzyme applications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp 167–178

Chomvong K, Lin E, Blaisse M, Gillespie AE, Cate JHD (2017) Relief of xylose binding to cellobiose phosphorylase by a single distal mutation. ACS Synth Biol 6:206–210. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.6b00211

Claus S, Van Bogaert INA (2017) Sophorolipid production by yeasts: a critical review of the literature and suggestions for future research. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 101:7811–7821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-017-8519-7

Colla K, Costanzo A, Gamlath S (2018) Fat replacers in baked food products. Foods 7:192. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods7120192

Da Silva Mde L, Iacomini M, Jablonski E, Gorin PA (1993) Carbohydrate, glycopeptide and protein components of the lichen Sticta sp. and effect of storage. Phytochemistry 33:547–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9422(93)85446-X

De Groeve MRM, Desmet T, Soetaert W (2010a) Engineering of cellobiose phosphorylase for glycoside synthesis. J Biotechnol 156:253–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.07.006

De Groeve MRM, Remmery L, Van Hoorebeke A, Stout J, Desmet T, Savvides SN, Soetaert W (2010b) Construction of cellobiose phosphorylase variants with broadened acceptor specificity towards anomerically substituted glucosides. Biotechnol Bioeng 107:413–420. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.22818

De Winter K, Cerdobbel A, Soetaert W, Desmet T (2011) Operational stability of immobilized sucrose phosphorylase: continuous production of α-glucose-1-phosphate at elevated temperatures. Process Biochem 46:2074–2078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2011.08.002

De Winter K, Dewitte G, Dirks-Hofmeister ME, De Laet S, Pelantová H, Křen V, Desmet T (2015a) Enzymatic glycosylation of phenolic antioxidants: phosphorylase-mediated synthesis and characterization. J Agric Food Chem 63:10131–10139. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04380

De Winter K, Van Renterghem L, Wuyts K, Pelantová H, Křen V, Soetaert W, Desmet T (2015b) Chemoenzymatic synthesis of β-d-glucosides using cellobiose phosphorylase from Clostridium thermocellum. Adv Synth Catal 357:1961–1969. https://doi.org/10.1002/adsc.201500077

Desmet T, Soetaert W, Bojarová P, Křen V, Dijkhuizen L, Eastwick-Field V, Schiller A (2012) Enzymatic glycosylation of small molecules: challenging substrates require tailored catalysts. Chem Eur J 18:10786–10801. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201103069

Douglas CM (2001) Fungal β(1,3)-d-glucan synthesis. Med Mycol 39:55–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/mmy.39.1.55.66

Egusa S, Kitaoka T, Goto M, Wariishi H (2007) Synthesis of cellulose in vitro by using a cellulase/surfactant complex in a nonaqueous medium. Angew Chem Int Ed 46:2063–2065. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200603981

Egusa S, Yokota S, Tanaka K, Esaki K, Okutani Y, Ogawa Y, Kitaoka T, Goto M, Wariishi H (2009) Surface modification of a solid-state cellulose matrix with lactose by a surfactant-enveloped enzyme in a nonaqueous medium. J Mater Chem 19:1836–1842. https://doi.org/10.1039/b819025a

Egusa S, Kitaoka T, Igarashi K, Samejima M, Goto M, Wariishi H (2010) Preparation and enzymatic behavior of surfactant-enveloped enzymes for glycosynthesis in nonaqueous aprotic media. J Mol Catal B Enzym 67:225–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.08.010

Fushinobu S, Hidaka M, Hayashi AM, Wakagi T, Shoun H, Kitaoka M (2011) Interactions between glycoside hydrolase family 94 cellobiose phosphorylase and glucosidase inhibitors. J Appl Glycosci 58:91–97. https://doi.org/10.5458/jag.jag.jag-2010_022

Geys R, Soetaert W, Van Bogaert INA (2014) Biotechnological opportunities in biosurfactant production. Curr Opin Biotechnol 30:66–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2014.06.002

Goldemberg SH, Maréchal LR, De Souza BC (1966) β-1,3-oligoglucan: orthophosphate glucosyltransferase from Euglena gracilis. J Biol Chem 241:45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-2744(67)90226-4

Greenway F, O’Neil CE, Stewart L, Rood J, Keenan M, Martin R (2007) Fourteen weeks of treatment with Viscofiber® increased fasting levels of glucagon-like peptide-1 and peptide-YY. J Med Food 10:720–724. https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2007.405

Hamura K, Saburi W, Abe S, Morimoto N, Taguchi H, Mori H, Matsui H (2012) Enzymatic characteristics of cellobiose phosphorylase from Ruminococcus albus NE1 and kinetic mechanism of unusual substrate inhibition in reverse phosphorolysis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 76:812–818. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.110954

Hamura K, Saburi W, Matsui H, Mori H (2013) Modulation of acceptor specificity of Ruminococcus albus cellobiose phosphorylase through site-directed mutagenesis. Carbohydr Res 379:21–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carres.2013.06.010

Hidaka M, Kitaoka M, Hayashi K, Wakagi T, Shoun H, Fushinobu S (2004) Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of cellobiose phosphorylase from Cellvibrio gilvus. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr 60:1877–1878. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444904017767

Hidaka M, Kitaoka M, Hayashi K, Wakagi T, Shoun H, Fushinobu S (2006) Structural dissection of the reaction mechanism of cellobiose phosphorylase. Biochem J 398:37–43. https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20060274

Hiraishi M, Igarashi K, Kimura S, Wada M, Kitaoka M, Samejima M (2009) Synthesis of highly ordered cellulose II in vitro using cellodextrin phosphorylase. Carbohydr Res 344:2468–2473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carres.2009.10.002

Isono N, Tamamoto Y, Saburi W (2013) β-1,3-glucan manufacturing method. US8530202B2

Ito F, Iwasaki T, Mikami T (1994) Production of laminarioligosaccharide. JPH06113874A

Jamois F, Le Goffic F, Yvin JC, Plusquellec D, Ferrières V (2008) How to improve chemical synthesis of laminaribiose on a large scale. Open Glycosci 1:19–24. https://doi.org/10.2174/1875398100801010019

Kauss H, Kriebitzsch C (1969) Demonstration and partial purification of A β-(1→3)-glucan phosphorylase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 35:926–930. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-291X(69)90713-X

Kitaoka M (2015) Diversity of phosphorylases in glycoside hydrolase families. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:8377–8390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-015-6927-0

Kitaoka M, Sasaki T, Taniguchi H (1991a) Production of cellobiose. JPH03130086A

Kitaoka M, Sasaki T, Taniguchi H (1991b) Synthesis of laminarioligosaccharides using crude extract of Euglena gracilis Z cells. Agric Biol Chem 55:1431–1432. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb1961.55.1431

Kitaoka M, Sasaki T, Taniguchi H (1992) Synthetic reaction of Cellvibrio gilvus cellobiose phosphorylase. J Biochem 112:40–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123862

Kitaoka M, Sasaki T, Taniguchi H (1993) Purification and properties of laminaribiose phosphorylase (EC 2.4. 1.31) from Euglena gracilis Z. Arch Biochem Biophys 304:508–514. https://doi.org/10.1006/abbi.1993.1383

Kitaoka M, Matsuoka Y, Mori K, Nishimoto M, Hayashi K (2012) Characterization of a bacterial laminaribiose phosphorylase. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 76:343–348. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.110772

Kobayashi S, Kashiwa K, Kawasaki T, Shoda S (1991) Novel method for polysaccharide synthesis using an enzyme: the first in vitro synthesis of cellulose via a nonbiosynthetic path utilizing cellulase as catalyst. J Am Chem Soc 113:3079–3084. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00008a042

Kobayashi K, Nakajima M, Aramasa H, Kimura S, Iwata T, Nakai H, Taguchi H (2019) Large-scale preparation of β-1,2-glucan using quite a small amount of sophorose. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 83:1867–1874. https://doi.org/10.1080/09168451.2019.1630257

Koch TJ, Häßler T, Kipping F (2016) Process for the enzymatic preparation of a product glucoside and of a co-product from an educt glucoside. WO2016038142A1

Koch TJ, Häßler T, Brucher B, Vogel A (2017) Cellobiose phosphorylase. EP3191586B1

Krishnareddy M, Kim Y-K, Kitaoka M, Mori Y, Hayashi K (2002) Cellodextrin phosphorylase from Clostridium thermocellum YM4 strain expressed in Escherichia coli. J Appl Glycosci 49:1–8. https://doi.org/10.5458/jag.49.1

Kuhaudomlarp S, Patron NJ, Henrissat B, Rejzek M, Saalbach G, Field RA (2018) Identification of Euglena gracilis β-1,3-glucan phosphorylase and establishment of a new glycoside hydrolase (GH) family GH149. J Biol Chem 293:2865–2876. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA117.000936

Kuhaudomlarp S, Pergolizzi G, Patron NJ, Henrissat B, Field RA (2019a) Unraveling the subtleties of β-(1→3)-glucan phosphorylase specificity in the GH94, GH149, and GH161 glycoside hydrolase families. J Biol Chem 294:6483–6493. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA119.007712

Kuhaudomlarp S, Stevenson CEM, Lawson DM, Field RA (2019b) The structure of a GH149 β-(1→3) glucan phosphorylase reveals a new surface oligosaccharide binding site and additional domains that are absent in the disaccharide-specific GH94 glucose-β-(1→3)-glucose (laminaribiose) phosphorylase. Proteins 87:885–892. https://doi.org/10.1002/prot.25745

Kuhaudomlarp S, Walpole S, Stevenson CEM, Nepogodiev SA, Lawson DM, Angulo J, Field RA (2019c) Unravelling the specificity of laminaribiose phosphorylase from Paenibacillus sp. YM-1 towards donor substrates glucose/mannose 1-phosphate by using X-ray crystallography and saturation transfer difference NMR spectroscopy. ChemBioChem 20:181–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.201800260

Kumar K, Rajulapati V, Goyal A (2020) In vitro prebiotic potential, digestibility and biocompatibility properties of laminari-oligosaccharides produced from curdlan by β-1,3-endoglucanase from Clostridium thermocellum. 3 Biotech 10:241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-020-02234-0

Liang Y, Zhu L, Gao M, Wu J, Zhan X (2018) Effective production of biologically active water-soluble β-1,3-glucan by a coupled system of Agrobacterium sp. and Trichoderma harzianum. Prep Biochem Biotechnol 48:446–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826068.2018.1452259

Liu N, Fosses A, Kampik C, Parsiegla G, Denis Y, Vita N, Fierobe HP, Perret S (2019) In vitro and in vivo exploration of the cellobiose and cellodextrin phosphorylases panel in Ruminiclostridium cellulolyticum: implication for cellulose catabolism. Biotechnol Biofuels 12:208. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-019-1549-x

Lombard V, Golaconda RH, Drula E, Coutinho P, Henrissat B (2014) The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res 42:D490–D495. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt1178

Lou J, Dawson KA, Strobel HJ (1996) Role of phosphorolytic cleavage in cellobiose and cellodextrin metabolism by the ruminal bacterium Prevotella ruminicola. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:1770–1773. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.62.5.1770-1773.1996

Luley-Goedl C, Nidetzky B (2010) Carbohydrate synthesis by disaccharide phosphorylases: reactions, catalytic mechanisms and application in the glycosciences. Biotechnol J 5:1324–1338. https://doi.org/10.1002/biot.201000217

Maréchal LR (1967) β-1,3-Oligoglucan: orthophosphate glucosyltransferases from Euglena gracilis. II. Comparative studies between laminaribiose- and β-1,3-oligoglucan phosphorylase. Biochim Biophys Acta 146:431–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-2744(67)90227-6

Maréchal LR, Goldemberg SH (1963) Laminaribiose phosphorylase from Euglena gracilis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 13:106–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-291X(63)90172-4

Mikkola S (2020) Nucleotide sugars in chemistry and biology. Molecules 25:5755. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25235755

Mitsuyoshi S, Okamoto K, Yamada K (2001) Laminaribiose phosphorylase, process for producing the same and process for producing laminarioligosaccharide by using the enzyme. WO2001079475

Morgan KR, Ofman DJ (1998) Glucagel, a gelling β-glucan from barley. Cereal Chem 75:879–881. https://doi.org/10.1094/CCHEM.1998.75.6.879

Müller C, Hartig D, Vorländer K, Sass AC, Scholl S, Jördening H-J (2017a) Chitosan-based hybrid immobilization in bienzymatic reactions and its application to the production of laminaribiose. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 40:1399–1410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00449-017-1797-8

Müller C, Ortmann T, Abi A, Hartig D, Scholl S, Jördening H-J (2017b) Immobilization and characterization of E. gracilis extract with enriched laminaribiose phosphorylase activity for bienzymatic production of laminaribiose. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 182:197–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-016-2320-4

Nakai H, Hachem MA, Petersen BO, Westphal Y, Mannerstedt K, Baumann MJ, Dilokpimol A, Schols HA, Duus JØ, Svensson B (2010) Efficient chemoenzymatic oligosaccharide synthesis by reverse phosphorolysis using cellobiose phosphorylase and cellodextrin phosphorylase from Clostridium thermocellum. Biochimie 92:1818–1826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2010.07.013

Nakai H, Kitaoka M, Svensson B, Ohtsubo K (2013) Recent development of phosphorylases possessing large potential for oligosaccharide synthesis. Curr Opin Chem Biol 17:301–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.01.006

Nakajima M, Toyoizumi H, Abe K, Nakai H, Taguchi H, Kitaoka M (2014) 1,2-β-Oligoglucan phosphorylase from Listeria innocua. PLoS One 9:e92353. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0092353

Nakajima M, Tanaka N, Furukawa N, Nihira T, Kodutsumi Y, Takahashi Y, Sugimoto N, Miyanaga A, Fushinobu S, Taguchi H, Nakai H (2017) Mechanistic insight into the substrate specificity of 1,2-β-oligoglucan phosphorylase from Lachnoclostridium phytofermentans. Sci Rep 7:42671. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42671

Nidetzky B, Zhong C (2020) Phosphorylase-catalyzed bottom-up synthesis of short-chain soluble cello-oligosaccharides and property-tunable cellulosic materials. Biotechnol Adv 107633: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107633

Nie S, Cui SW, Xie M (2018) Beta-glucans and their derivatives. In: Cui SW, Xie M (eds) Nie S. Academic Press, Bioactive polysaccharides, pp 99–141

Nihira T, Saito Y, Kitaoka M, Nishimoto M, Otsubo K, Nakai H (2012) Characterization of a laminaribiose phosphorylase from Acholeplasma laidlawii PG-8A and production of 1,3-β-d-glucosyl disaccharides. Carbohydr Res 361:49–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carres.2012.08.006

O’Neill EC, Field RA (2015) Enzymatic synthesis using glycoside phosphorylases. Carbohydr Res 403:23–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carres.2014.06.010

O’Neill EC, Pergolizzi G, Stevenson CEM, Lawson DM, Nepogodiev SA, Field RA (2017) Cellodextrin phosphorylase from Ruminiclostridium thermocellum: X-ray crystal structure and substrate specificity analysis. Carbohydr Res 8:118–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carres.2017.07.005

Ogawa Y, Noda K, Kimura S, Kitaoka M, Wada M (2014) Facile preparation of highly crystalline lamellae of (1→3)-β-D-glucan using an extract of Euglena gracilis. Int J Biol Macromol 64:415–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.12.027

Otsuka M, Ishida A, Nakayama Y, Saito M, Yamazaki M, Murakami H, Nakamura Y, Matsumoto M, Mamoto K, Takada R (2004) Dietary supplementation with cellooligosaccharide improves growth performance in weanling pigs. Anim Sci J 75:225–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-0929.2004.00180.x

Percy A, Ono H, Hayashi K (1998) Acceptor specificity of cellobiose phosphorylase from Cellvibrio gilvus: synthesis of three branched trisaccharides. Carbohydr Res 308:423–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-6215(98)00109-8

Petrović DM, Kok I, Woortman AJJ, Ćirić J, Loos K (2015) Characterization of oligocellulose synthesized by reverse phosphorolysis using different cellodextrin phosphorylases. Anal Chem 87:9639–9646. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.5b01098

Pokusaeva K, O’Connell-Motherway M, Zomer A, MacSharry J, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D (2011) Cellodextrin utilization by Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:1681–1690. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01786-10

Putta S, Yarla NS, Lakkappa DB, Imandi SB, Malla RR, Chaitanya AK, Chari BPV, Saka S, Vechalapu RR, Kamal MA, Tarasov VV, Chubarev VN, Kumar KS, Aliev G (2018) Probiotics: supplements, food, pharmaceutical industry. In: Grumezescu AM, Holban AM (eds) Therapeutic, probiotic, and unconventional foods, 1st edn. Academic Press, London, pp 15–25

Rahar S, Swami G, Nagpal N, Nagpal M, Singh G (2011) Preparation, characterization, and biological properties of β-glucans. J Adv Pharm Technol Res 2:94–103. https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-4040.82953

Rajashekhara E, Kitaoka M, Kim YK, Hayashi K (2002) Characterization of a cellobiose phosphorylase from a hyperthermophilic Eubacterium, Thermotoga maritima MSB8. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 66:2578–2586. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.66.2578

Reichenbecher M, Lottspeich F, Bronnenmeier K (1997) Purification and properties of a celiobiose phosphorylase (CepA) and a cellodextrin phosphorylase (CepB) from the cellulolytic thermophile Clostridium stercorarium. Eur J Biochem 247:262–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00262.x

Ronchera-Oms CL, Jiménez NV, Peidro J (1995) Stability of parenteral nutrition admixtures containing organic phosphates. Clin Nutr 14:373–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5614(95)80055-7

Sakamoto K, Lochhead RY, Maibach HI, Yamashita Y (2017) Cosmetic science and technology: theoretical principles and applications, 1st edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Samain E, Lancelon-Pin C, Férigo F, Moreau V, Chanzy H, Heyraud A, Driguez H (1995) Phosphorolytic synthesis of cellodextrins. Carbohydr Res 271:217–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/0008-6215(95)00022-L

Sawano T, Saburi W, Hamura K, Matsui H, Mori H (2013) Characterization of Ruminococcus albus cellodextrin phosphorylase and identification of a key phenylalanine residue for acceptor specificity and affinity to the phosphate group. FEBS J 280:4463–4473. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.12408

Sheth K, Alexander K (1969) Purification and glucosyltransferase properties: orthophosphate glucosyltransferase from Clostridium thermocellum. J Biol Chem 244:457–464

Shi L (2016) Bioactivities, isolation and purification methods of polysaccharides from natural products: a review. Int J Biol Macromol 92:37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.06.100

Shibata S, Nishikawa Y, Takeda T, Tanaka M, Fukuoka F, Nakanishi M (1968) Studies on the chemical structures of the new glucans isolated from Gyrophora esculenta Miyoshi and Lasallia papulosa (Ach.) Llano and their inhibiting effect on implanted sarcoma 180 in mice. Chem Pharm Bull 16:1639–1641. https://doi.org/10.1248/cpb.16.1639

Shintate K, Kitaoka M, Kim YK, Hayashi K (2003) Enzymatic synthesis of a library of β-(1→4) hetero-d-glucose and d-xylose-based oligosaccharides employing cellodextrin phosphorylase. Carbohydr Res 338:1981–1990. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-6215(03)00314-8

Sibakov J, Myllymäki O, Holopainen U, Kaukovirta-Norja A, Hietaniemi V, Pihlava JM, Lehtinen P, Poutanen K (2012) β-Glucan extraction methods from oats: minireview. Agro Food Ind Hi Tech 23:10–12 https://www.teknoscienze.com/tks_article/minireview-glucan-extraction-methods-from-oats/

Singh RP, Pergolizzi G, Nepogodiev SA, De Andrade P, Kuhaudomlarp S, Field RA (2020) Preparative and kinetic analysis of β-1,4- and β-1,3-glucan phosphorylases informs access to human milk oligosaccharide fragments and analogues thereof. ChemBioChem 21:1043–1049. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.201900440

Sternberg D, Mandels GR (1979) Induction of cellulolytic enzymes in Trichoderma reesei by sophorose. J Bacteriol 139:761–769. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.139.3.761-769.1979

Suzuki M, Kaneda K, Nakai Y, Kitaoka M, Taniguchi H (2009) Synthesis of cellobiose from starch by the successive actions of two phosphorylases. New Biotechnol 26:137–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbt.2009.07.004

Tanaka K, Kawaguchi T, Imada Y, Ooi T, Arai M (1995) Purification and properties of cellobiose phosphorylase from Clostridium thermocellum. J Ferment Bioeng 79:212–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/0922-338X(95)90605-Y

Tran GH, Desmet T, De Groeve MRM, Soetaert W (2011) Probing the active site of cellodextrin phosphorylase from Clostridium stercorarium: kinetic characterization, ligand docking, and site-directed mutagenesis. Biotechnol Prog 27:326–332. https://doi.org/10.1002/btpr.555

Tran GH, Desmet T, Saerens K, Waegeman H, Vandekerckhove S, D’hooghe M, Van Bogaert INA, Soetaert W (2012) Biocatalytic production of novel glycolipids with cellodextrin phosphorylase. Bioresour Technol 115:84–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2011.09.085

Ubiparip Z, Beerens K, Franceus J, Vercauteren R, Desmet T (2018) Thermostable alpha-glucan phosphorylases: characteristics and industrial applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102:8187–8202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-018-9233-9

Ubiparip Z, Moreno DS, Beerens K, Desmet T (2020) Engineering of cellobiose phosphorylase for the defined synthesis of cellotriose. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 104:8327–8337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-020-10820-8

Van Hoorebeke A, Stout J, Kyndt J, De Groeve MRM, Dix I, Desmet T, Soetaert W, Van Beeumen J, Savvides SN (2010) Crystallization and X-ray diffraction studies of cellobiose phosphorylase from Cellulomonas uda. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 66:346–351. https://doi.org/10.1107/S1744309110002642

Vetvicka V, Vannucci L, Sima P, Richter J (2019) Beta glucan: supplement or drug? From laboratory to clinical trials. Molecules 24:1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24071251

Wu Y, Mao G, Fan H, Song A, Zhang Y-HP, Chen H (2017) Biochemical properties of GH94 cellodextrin phosphorylase THA_1941 from a thermophilic eubacterium Thermosipho africanus TCF52B with cellobiose phosphorylase activity. Sci Rep 7:4849. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05289-x

Yamamoto Y, Kawashima D, Hashizume A, Hisamatsu M, Isono N (2013) Purification and characterization of 1,3-β-d-glucan phosphorylase from Ochromonas danica. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 77:1949–1954. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.130411

Ye X, Zhang C, Zhang Y-HP (2012) Engineering a large protein by combined rational and random approaches: stabilizing the Clostridium thermocellum cellobiose phosphorylase. Mol BioSyst 8:1815–1823. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2mb05492b

Yernool DA, McCarthy JK, Eveleigh DE, Bok JD (2000) Cloning and characterization of the glucooligosaccharide catabolic pathway α-glucan glucohydrolase and cellobiose phosphorylase in the marine hyperthermophile Thermotoga neapolitana. J Bacteriol 182:5172–5179. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.182.18.5172-5179.2000

Zhang Y-HP, Lynd LR (2006) Biosynthesis of radiolabeled cellodextrins by the Clostridium thermocellum cellobiose and cellodextrin phosphorylases for measurement of intracellular sugars. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 70:123–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-005-0278-1

Zhang H, Palma AS, Zhang Y, Childs RA, Liu Y, Mitchell DA, Guidolin LS, Weigel W, Mulloy B, Ciocchini AE, Feizi T, Chai W (2016) Generation and characterization of β1,2-gluco-oligosaccharide probes from Brucella abortus cyclic β-glucan and their recognition by C-type lectins of the immune system. Glycobiology 26:1086–1096. https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cww041

Zhong C, Nidetzky B (2019) Three-enzyme phosphorylase cascade for integrated production of short-chain cellodextrins. Biotechnol J 15: https://doi.org/10.1002/biot.201900349

Zhong C, Luley-Goedl C, Nidetzky B (2019) Product solubility control in cellooligosaccharide production by coupled cellobiose and cellodextrin phosphorylase. Biotechnol Bioeng 116:2146–2155. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.27008

Zhong C, Duić B, Bolivar JM, Nidetzky B (2020a) Three-enzyme phosphorylase cascade immobilized on solid support for biocatalytic synthesis of cello-oligosaccharides. ChemCatChem 12:1350–1358. https://doi.org/10.1002/cctc.201901964

Zhong C, Ukowitz C, Domig K, Nidetzky B (2020b) Short-chain cello-oligosaccharides: intensification and scale-up of their enzymatic production and selective growth promotion among probiotic bacteria. J Agric Food Chem 68:8557–8567. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.0c02660

Zhu F, Du B, Xu B (2016) A critical review on production and industrial applications of beta-glucans. Food Hydrocoll 52:275–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2015.07.003

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (CARBAFIN, grant No. 761030), from Agency for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (VLAIO) (Baekeland doctoral scholarship assigned to M.D.D., grant No. HBC.2019.2175), and from Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen) (postdoctoral scholarship assigned to J.F, grant No. 12ZD821N).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.U. was responsible for writing and the original draft preparation. M.D.D assisted in the writing of the manuscript and was responsible for the design of figures. T.D., K.B., and J.F were responsible for reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This mini-review does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

All authors consented to the publication of this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ubiparip, Z., De Doncker, M., Beerens, K. et al. β-Glucan phosphorylases in carbohydrate synthesis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 105, 4073–4087 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-021-11320-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-021-11320-z