Abstract

The studies on the characterisation of glucosinolates (GLs) and their breakdown products in Brassicaceae species focus mainly on the edible parts. However, other products, e.g., dietary supplements, may be produced also from non-edible parts such as roots or early forms of growth: seeds or sprouts. Biological activity of these products depends on quantitative and qualitative GL composition, but is also strictly determined by GL conversion rate to chemopreventive isothiocyanates (ITC) and indoles. The aim of this study was to evaluate the conversion rate of GLs to ITC and indoles for various plant parts of chosen Brassica species in relation to their biological activity. For this purpose, the composition of GLs and their degradation products was determined as well as activity of myrosinase. Toxicological part of studies involved: MTT assay, restriction analysis, comet assay and Ames test. The composition of GLs and conversion rate to ITC and indoles was found to differ significantly between Brassica species and individual parts of the plant. The highest efficiency of conversion was observed for edible parts of plants: more than 70%, while in sprouts, it reached less than 1%, though myrosinase activity did not differ. The conversion rate directly affected biological activity of plant material. Higher concentration of ITC/indoles in the sample led to the increase of cytotoxicity. Majority of tested samples were able to induce covalent DNA modification in cell-free system. It was also confirmed that the presence of indolic GLs and products of their degradation stimulated mutagenicity, but did not lead to DNA fragmentation in cultured cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

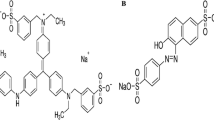

Brassicaceae vegetables are the most promising food components in cancer prophylaxis. As demonstrated in several epidemiologic studies, consumption of these plants significantly reduces the risk of common human cancers, including lung [1, 2] stomach [1], breast [3] or prostate cancer [4, 5]. The chemopreventive activity of Brassica plants is associated with the presence of secondary plant metabolites: glucosinolates (GLs) [6]. These phytochemicals, produced by plants for defence purposes, are hydrolysed by the enzyme myrosinase (β-thioglucoside glucohydrolase) to unstable intermediates: thiohydroxamate-O-sulfonates. Then, depending on environmental factors and activity of specifier proteins [7,8,9,10,11], GLs are converted to: isothiocyanates (ITC), thiocyanates, nitriles or epithionitriles (Fig. 1) [12, 13]. ITC with indolic side chains, because of their low stability, undergo further transformations to the corresponding alcohols [14]. One of them is indole-3-carbinol, well-known chemopreventive agent [15], which may give rise to further derivatives and/or condense to dimers and trimers, especially at low pH.

Scheme of enzymatic hydrolysis of glucosinolates by myrosinase depending on the environmental and protein factors and reactions of isothiocyanates with compounds containing nucleophilic groups. The acronyms refer to: ESP epithiospecifier protein, NSP nitrile-specifier protein, TFP thiocyanate-forming protein, ESM epithiospecifier modifying protein

The most promising GL breakdown products, considering chemoprevention of chronic diseases, are ITC and indolic derivatives [16, 17] owing to their well-established anti-inflammatory [18] and anti-carcinogenic properties [19,20,21,22]. The mechanisms behind health-promoting activities are strictly connected with strong electrophilicity and high bioavailability of ITC. For example, sulforaphane has been shown to be rapidly absorbed, achieving high absolute bioavailability at low doses in rats [23]. However, dose-dependent pharmacokinetics was evident, with bioavailability decreasing with increasing dosage. This was explained by the fact that at higher doses protein-binding sites become saturated, so that sulforaphane remains free and available for metabolism and excretion. The similar results were obtained for aromatic—phenethyl isothiocyanate [24]. For indoles, the mechanisms are not that well studied. Once in the cell, ITC are able to react with nucleophilic moieties of important biomolecules (Fig. 1), modifications of which often determine functioning of vital signalling pathways. For instance, ITC may cause imbalance in thiol-based redox homeostasis and lead to upregulation of transcription of cytoprotective proteins in two ways. First, by depleting glutathione (γ-Glu-Cys-Gly; GSH) which is a primary acceptor of ITC. In the reaction catalyzed by glutathione S-transferases [25], a stable thiocarbamate conjugate is formed, GSH concentration drops as a result and the cellular oxidation level increases. Oxidative stress triggers Nrf2-dependent signalling pathways, making ITC an indirect antioxidant [26, 27]. Second, ITC may directly react with sulphide groups of Keap1 protein, which abolishes its interaction with Nrf2 and makes the latter translocate to nucleus, where it triggers expression of cytoprotective genes. What need to be also mentioned is that the complex with cysteinyl residues of GSH is reversible. Dissociation may occur depending on environmental conditions [28, 29] and ITC may be transported through the body and can react with various protein targets, such as proteins of cytoskeleton, redox regulators, proteasome, and mitochondrial or signalling pathways’ components, as it was identified in experiments using 13C labelled sulforaphane and phenylethyl-ITC [30].

Although, reactions of ITC with thiols are almost one thousand times faster than with primary or secondary amino groups [31, 32], the latter have been also reported. It was demonstrated that ITC can react with amino groups and form stable conjugates under physiological conditions [33], e.g., with lysine residues of such blood proteins as albumin and haemoglobin [34]. Moreover, this type of reaction to thioureas may disrupt not only the structure of proteins, but also DNA. We have shown that ITC form conjugates with foodborne heterocyclic aromatic amines leading to the decrease of their mutagenicity [35]. It may be assumed that ITC are able to react also with such heterocyclic aromatic amines as purines and pyrimidines found in DNA. Indeed, the results of in vitro and in vivo investigations [21] suggested the genotoxicity and mutagenicity of some breakdown products of GLs. Alcoholic derivatives of indolic GLs—glucobrassicin, neoglucobrassicin, 4-methoxyglucobrassicin and 4-hydroxyglucobrassicin—readily formed DNA adducts and were highly mutagenic [36,37,38]. Furthermore, the degradation product of neoglucobrassicin (1-methoxy-indole-3-methanol) gave rise to substitutional DNA adducts with purines, both in vivo and in vitro, mainly N2-(1-methoxy-3-indolylmethyl)-dGua and N6-(1-methoxy-3-indolylmethyl)-dAde [39, 40].

The composition of GLs as well as myrosinase activity vary among individual parts of Brassica plants such as roots, leaves, stems, and is also diversified in different stages of growth of these plants [41,42,43]. This is due to the fact that these compounds are produced for protection against pathogens, and therefore, GL abundance changes depending on the stage of plant growth or function, Most of studies on the characterization of Brassicaceae species focused on edible parts of these plants [12, 44,45,46,47] and rarely considered non-edible parts such as roots or stalks [48,49,50]. Neither was the conversion rate of GLs to bioactive ITC and indoles evaluated, although it seems very crucial for biological activity. The lack of GL degradation or their degradation to other breakdown products such as nitriles and epithionitriles was shown not to trigger detoxification mechanisms responsible for the anti-carcinogenic properties of Brassica vegetables [51, 52].

In the present research, we have combined the chemical analysis and toxicological determinations for various parts and different stages of growth of Brassica plants to evaluate how GLs composition and their conversion rate is affecting the bioactivity of plant material.

Materials and methods

Materials

Seeds used in this research were produced by PNOS (Ożarowice Mazowieckie, Poland). All HPLC grade solvents were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) and MS grade solvents from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). Glucotropaeolin (GTL) was isolated from Cardamine pratensis (cuckooflower) in the Plant Breeding and Acclimatization Institute (IHAR), Poznań, Poland. Standard indolic compounds: indole-3-acetonitrile I3ACN and indole-3-acetic acid (I3AA) were purchased from Merck (Germany); 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM) and indole-3-carbinol (I3C) from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). The latter company also was the source of other chemicals used in this study: 3-butenenitrile, 4-pentenenitrile, 3-phenylpropanenitrile, allyl isothiocyanate, 3-(methylthio)propyl isothiocyanate, benzonitrile, 1,2-benzenedithiol, myrosinase from Sinapsis alba (EC 3.2.1.147), sulfatase from Helix Pomatia H1 (22,400 units/g solid) and DEAE Sephadex A-25 anion-exchange resin, as well as reagents for electrophoresis. The biochemicals were purchased from different sources: molecular DNA weight standards from DNA Gdansk (Poland), restriction endonucleases HpaII, Tru1I and buffers Tango®/R® from Fermantas (Lithuania), nucleic acid gel stain SYBR® Gold from Molecular Probes (USA), nucleic acid gel stain Gel Green® from Biotium (USA) and MTT, cell culture McCoy’s 5A medium, fetal bovine serum and streptomycin–penicylin antibiotics from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). MPF 98/100 Ames test with all necessary reagents and bacteria strains were obtained from Xenometrix (Switzerland). Other not listed chemicals and biochemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany) and were of the appropriate grade.

Plant material

Studied Brassica plants: radish (Raphanus sativus var. sativus), Brussel sprouts (Brassica oleracea var. gemmifera), savoy cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. sabauda L.) and white cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) were obtained from a local organic farm (Czapielsk, Poland). After harvest, individual parts of plants (e.g., leaves, stalk, and root) were separated and lyophilized, then ground and stored at − 20 °C until investigation. Seeds were divided into two parts. One portion was lyophilized, ground and stored at − 20 °C. The other was placed in germination plates for sprouting and transferred to a phytotron (photoperiod: 16 h of light, 8 h in the dark) with controlled temperature (25 °C). The seeds were sprinkled twice a day with 600 mL of mineral water (Żywiec Zdrój S.A.). After 7 days, sprouts were harvested, washed and kept freeze-dried at − 20 °C until investigation.

Glucosinolate (GL) analysis

To determine the content of GLs, the ISO 9167-1 method with modifications described previously [1] was used. For this purpose, 100 mg of each plant material was submitted to extraction and enzymatic desulfation. Obtained desulfo-glucosinolates (ds-GLs) were analyzed by an LC-DAD-ESI-MS system (Agilent Technologies) using a Grace Altima HP AQ RP-C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm, 3 µm). The mobile phase contained water (A) and acetonitrile/water (80:20 [v/v], B). Chromatographic separation was performed at 30 °C with 1 mL/min flow rate and the following gradient program: linear gradient from 5% B to 100% B for 10 min and isocratic elution with 100% B for 15 min. The injection volume of samples was 30 µL. The chromatographic peaks were first detected by DAD (Agilent 1200 series) at 229 nm, then the identity of individual ds-GLs was confirmed by ESI-MS (Agilent 6130 Quadrupole LC/MS). MS parameters were as follows: capillary voltage, 3000 V; fragmentor, 120 V; drying gas temperature, 350 °C; gas flow (N2), 12 L/min; nebulizer pressure, 35 psig. The instrument was operated both in positive and negative ion modes, scanning from m/z 100 to 800.

Determination of total isothiocyanate (ITC) content

The content of ITC was determined by a modified method developed by Zhang et al. [53] with modifications [54]. Lyophilized plant material (0.2 g) was mixed with 5 mL of 0.01M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C to achieve complete myrosinase catalyzed conversion of parent aliphatic and aromatic GLs into degradation products. The samples were concentrated on Bakerbond SPE C18 500 mg cartridges (J. T. Baker, Center Valley, PA). Concentrated ITC extracts (0.1 mL of the eluate) were submitted to cyclocondensation reaction in a mixture containing 0.5 mL of 2-propanol, 0.5 mL of 0.1M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.5), and 0.1 mL of 60 mM 1,2-benzenedithiol dissolved in 2-propanol. After 1 h at 65 °C, the product of reaction, 1,3-benzenedithiol-2-thione, was analyzed by reverse phase HPLC using an Agilent 1200 system coupled with a DAD detector. The reaction mixture (30 µL) was injected onto a 150 mm, 4.6 mm, 3.5 mm Zorbax Eclipse XDBC8 column. The mobile phase used was 4.8% [v/v] formic acid in water (A) and methanol (B) with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The gradient changed as follows: 60% B to 100% B within 12 min, then 100% B for 3 min. Chromatograms were traced at 365 nm.

Determination of hydrolysis products of indolic GLs

To determine the indole content in the plant samples, the same eluates as for ITC analysis were used. The HPLC-DAD-FLD system (Agilent Technologies 1200 Series) equipped with a Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C8 column was employed for the analysis of indolic compounds as described previously [54]. A linear gradient of acetonitrile in water changing from 10 to 100% within 30 min, the mobile phase flow 1 mL/min and the injection volume of 20 µL were applied. Monitoring of florescence of indolic analytes was carried out at 280/360 nm (Ex/Em).

Determination of other GL breakdown products

For the determination of other GL breakdown products, lyophilized plant powder (0.03 g) was dispersed in 0.75 mL of 0.01 M sodium phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.4) and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C to allow GL hydrolysis. Afterwards, benzonitrile (≥ 99.9%, Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Steinheim, Germany) was added as an internal standard. The hydrolysis products were extracted with methylene chloride as described previously [54] and subjected to analysis. GC–MS analysis was performed as reported previously [55].

Determination of myrosinase activity by pH-stat method

The determination of myrosinase activity was based on pH-static method optimized by us previously [52]. The lyophilized plant samples (0.5 g) were suspended in 15 mL of 80 mM NaCl (pH adjusted to 6.5 with 1 mM HCl), transferred into ice bath and homogenized (6500 rpm for 5 min) to completely liberate the enzyme. Initial hydrolysis of endogenous GLs was carried out by stirring the reaction mixture at 37 °C with monitoring pH value. When pH of the mixtures stabilized at the level of 6.5, 15 mL of 2.5 mM glucotropaeolin was added and its hydrolysis was carried out at 37 °C. To maintain constant pH at a 6.5, the 1 mM NaOH solution was dosed using T70 titrator (Mettler Toledo) set at pH-stating option. Myrosinase activity was calculated based on the quantity of 1 mM NaOH required to neutralize H + ions released during hydrolysis expressed as mmoles of hydrolysed GTL per min per 1 g of dry weight (U/g dw of plant sample).

MTT cytotoxicity assay

For preparation of water extracts for MTT assay, as well as for other biological tests, extracts were prepared by suspending 0.25 g of each ground or freeze-dried plant material in 5 mL of cold redistilled water. The suspension was homogenized (10,000 rpm, 5 min, 4 °C), the blade and vessel rinsed with 5 mL of new portion of cold redistilled water, combined with homogenate, and then the whole mixture was centrifuged (5000 rpm, 20 min, 4 °C). The supernatants were sterilized by filtration (Millex-GP 0.22 µm filters, Merck-Millipore) and stored in single-use portions at − 80 °C. HT29 (human colon adenocarcinoma) cells from ATCC collection were grown in McCoy’s medium supplemented with l-glutamine (2 mM), sodium pyruvate (200 mg/mL), fetal bovine serum (10% [v/v]) and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin). The cells were grown at 37 °C in humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 in a Smart cell incubator (Heal Force). Cells were seeded in 96-well tissue culture plates (about 15,000 cells/well in 0.15 mL) and allowed to settle for 24 h at 37 °C. Then, the cells were treated for 3 h, 6 h, 24 h and 72 h with 0.05 mL of different concentrations of tested water plant extracts diluted with redistilled water. In the case of shorter exposure, the medium was aspirated after 3 h, 6 h and 24 h from the wells, replaced with fresh medium and the cells were incubated at 37 °C up to 72 h. After 72 h of incubation, 0.05 mL of MTT solution (4 mg/mL) was added and cells were left for another 4 h at 37 °C. Finally, medium was carefully removed from wells, and formazan crystals formed were dissolved in 0.05 mL of DMSO. The absorption of the resultant solutions was determined at 540 nm using a TECAN Infinite M200 plate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Switzerland). The cytotoxicity was expressed as growth inhibition of cells exposed to tested water plant extracts compared to controls (non-treated cells whose growth was regarded as 100% cell growth). The results are presented as Accumulated Survival Index (ASI), calculated as the sum of areas under the cell growth curves for each time of exposure of cells on studied sample as proposed before [56].

Determination of genotoxicity by comet assay with simultaneous evaluation of cell growth inhibition

The influence of water plant extracts, the same that were used for MTT assay, on genetic material integrity in HT29 cell line was evaluated by comet assay. One day prior the experiments, the cells were seeded in 24-well plates using a volume of 1.8 mL and the density of 100 or 200 thousand cells per well for 3 or 18 h exposure, respectively. The cells were treated with the investigated extracts at concentrations equivalent to 0.5 mg dw/mL and 2.5 mg dw/mL for 3 h or at a concentration equivalent to 0.5 mg dw/mL for 18 h at 37 °C in incubator (Heal Force) maintaining humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Based on MTT assay results, non-cytotoxic concentrations were selected. For negative control, PBS buffer instead of water plant extracts was used and for positive control H2O2 diluted with PBS buffer to a concentration of 450 µM. After exposure, cells were trypsinized, re-suspended in 2 mL of fresh medium and 0.5 mL of this suspension was taken for cell counting, while 1 mL was used for comet assay. The remaining in the plate 0.5 mL of the suspension was filled up to 2 mL with fresh medium, left in the same plate for the additional 48 h in the same incubator and then cell number in each well was determined again. For comet assay, the cells were spun down (4000 rpm, 15 min, 4 °C), re-suspended in 1 mL of cold PBS and spun down again. Afterwards, 20 µL of cell suspension (density 106 cells/mL) was combined with 150 µL of LMP agarose (1% [w/v] warmed up to 37 °C). Two drops (volume of 35 µL each) of these suspensions were pipetted onto microscope slides protected with 0.5% NMP agarose and flattened with a coverslip. The prepared slides were placed on ice and left protected from light until LMP agarose solidified. The coverslips were carefully removed. The cells were lysed by submerging the slides in cold lysis buffer (9:1 A:B [v/v]; A: 2.5 M NaCl, 0.1 M EDTA, 10 mM Tris pH 10; B: 10% Triton X [v/v]) for 2 h at 4 °C in the dark. After lysis, the slides were transferred to the electrophoresis unit placed on ice and submerged in electrophoretic buffer (0.3 M NaOH, 1 mM EDTA, pH 13.3) for 30 min at 4 °C in a light protected container to unwind chromatin. Electrophoresis was carried out at 26 V (0.75 V/cm), 300 mA for 30 min. Finally, the slides were neutralized by rinsing three times with cold neutralization buffer (0.4 M Tris–HCl, pH 7.5), then once with cold water and 70% ethanol. The cell nuclei embedded on microscope slides were stained with fluorescent dye Gel Green® for 20 min at 4 °C and so called comets analyzed using fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Germany) equipped with Metafer4® software. The results are presented as mean per cent of DNA in tail determined in 200 consecutive nuclei per gel (2 gels per microscope slide).

Determination of mutagenicity by Ames MPF test

The induction of mutation was studied using microplate version of Ames test, performed in liquid bacterial culture [57]. Salmonella typhimurium TA98/TA100 strains were used with and without metabolic activation by rat liver microsomal fraction S9 isolated from phenobarbital 5/6 benzoflavone-induced (Xenometrix, Switzerland). The bacteria were exposed on water plant extracts prepared as described above, at a concentration equivalent to 1 mg dw/mL for 1.5 h at 37 °C. Positive controls used were: 2NF (2-nitrofluorene, for TA98 − S9), 4-NQO (4-nitroquinoline N-oxide, for TA100 − S9) and 2-AA (2-aminoanthracene, for TA98/TA100 + S9). The procedure followed strictly manufacturer’s recommendation available from the website: http://www.xenometrix.ch.

Covalent DNA modification in a cell-free system by restriction analysis

To determine the ability of compounds present in water plant extracts to modify DNA in a cell-free system, the restriction analysis technique described previously was employed [58]. Briefly, this method employs a 695 bp long DNA amplicon that contains two restriction sites: one consisting of GC base pairs recognized by restriction endonuclease HpaII and the other consisting of AT base pairs recognized by the enzyme Tru1I. The modification of the restriction sites abolishes their recognition and thus cleavage by the restriction enzymes. For the experiment, 55 µL of water plant extracts, from which the myrosinase enzyme (30 kDa) was removed by filtration (nanosep® filter, cut-off 10 kDa, PALL) was added to 5 µL of 25 ng/µL DNA amplicon (final concentration 2 ng/µL). For negative control, water instead of plant extracts was used. The reaction of DNA modification was carried out for 2 h at 37 °C. Afterwards, the samples were submitted to extraction with chloroform/isoamyl alcohol 24:1 [v/v] in a ratio of 1:1 [v/v] to remove the remaining proteins and unbound compounds. The mixtures were vortexed vigorously (30 min; at room temperature) and centrifuged for 15 min at 10,000 rpm. The water fractions were collected, divided into two separate portions of 20 µL each and submitted to cleavage by restriction endonucleases by adding 2 µL either digestion mixes containing HpaII or Tru1I. Digestion mixes included for HpaII: 1 U of enzyme per 40 ng of DNA and 1 µL of 10× buffer Tango® (33 mM Tris–acetate, pH 7.9; 10 mM Mg acetate; 66 mM K-acetate 0.1 mg/mL BSA) per each 10 µL of the sample and for Tru1I: 2 U of enzyme per 40 ng of DNA and 1 µL of 10× buffer R® (10 mM Tris HCl at pH 8.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mg/mL BSA) per each 10 µL of the sample. DNA cleavage was carried out for 4 h at 37 °C. For the analysis of DNA fragments generated as a result of DNA amplicon cleavage by the restriction enzymes, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in non-denaturing conditions (native-PAGE) was used. The samples (15 µL) combined with 5 µL of loading buffer (15% [w/v] Ficoll, 0.25% [w/v] bromophenol blue) were loaded onto 6% polyacrylamide gel. Electrophoretic separation was carried out for 90 min at 90 V in TBE buffer (89 mM Tris, 89 mM boric acid, 50 mM EDTA, pH 8.3). DNA bands were stained by submerging gels in SYBR® Gold solution (10 µL of commercial preparation per 100 mL of TBE buffer) for 20 min at 4 °C. DNA bands were visualised on UV transilluminator and gels were photographed using a digital camera (Canon EOS 1000D).

Results

Composition of GLs

Table 1 presents the composition of GLs found in different plant parts and stages of growth for four species of Brassica vegetables studied. As can be seen, not all possible GLs were biosynthesized in each sample. In most cases, a nearly complete utilization of genetic potential was observed in sprouts, while the lowest GL variety often occurred in the edible parts (marked in bold in Table 1). In addition, the quantitative composition of GLs differed significantly between individual parts of Brassica plants. For example, sinigrin concentration varied from 3.05 ± 0.007 µmol/g dw in leaves to 24.58 ± 5.84 µmol/g dw in sprouts of white cabbage and from 0.76 ± 0.02 in leaves to 17.20 ± 1.78 in seeds of savoy cabbage. In general, the highest content of GLs (Table 2) was determined in seeds (from 21.03 ± 3.52 to 41.09 ± 6.7 µmol/g dw) and sprouts (from 16.03 ± 1.76 to 41.30 ± 7.97 µmol/g dw); in the case of white cabbage also in roots (22.08 ± 1.97 µmol/g dw). Bellostas et al. have shown that total concentration of GLs in seeds of Savoy and white cabbage was approximately 120 µmol/g dw and decreased slightly in 7-day-old sprouts to 100 µmol/g dw [49], which is even 2–5 fold higher than detected by us (Table 2). In white cabbage leaves, according to Kusznierewicz et al., this value oscillated between 3.3 µmol/g dw and 7.7 µmol/g dw [44]. In studies on 5 varieties of radish, total GLs content ranged from 76.9 to 133.9 µmol/g dw in sprouts and from 17.1 to 100.1 µmol/g dw in bulb [59]. Moreover, every day after seed germination, as it was observed for nine Brassica species, the concentration of these organosulfur compounds was decreasing even by 80% [50]. Our samples were collected over several week periods, so most probably prolonged storage explains the lower abundance of GLs.

Of special interest were to us indolic GLs: neoglucobrassicin and 4-methoxyglucobrassicin, whose mutagenic properties are best documented [36,37,38,39,40]. In contrast to intuition, with the exception of radish, edible parts of plants studied contained the highest amounts of indolic GLs (Table 1). However, the most mutagenic neo-GBS was not the major indolic GL. Nonetheless, neo-GBS and/or 4-OMeGBS were found in almost all samples, e.g., concentration of neo-GBS differed from 0.08 ± 0.02 in white cabbage leaves up to 1.19 ± 0.15 in Brussels sprout heads, to as much as 2.95 ± 0.07 µmol/g dw in Savoy cabbage sprouts. Wiesner et al. reported that in pak choi (Brassica rapa spp. Chinensis) sprouts exposed on methyl jasmonate, the neo-GBS content in extract amounted to 158 nmoles/mL (approximately 0.23 µmol/g dw) and it caused high mutagenic effect against Salmonella typhimurium TA100 [60].

GL conversion to ITC and indoles

In this study, the total concentrations of main degradation products: isothiocyanates ITC, indoles, nitriles and epithionitriles, were determined for the investigated plant material obtained from individual parts or stages of growth for four representative crops from Brassica family (Table 2). In addition, the activity of myrosinase, the enzyme initializing degradation of GLs, was measured. The obtained results were used to calculate the rate of GL hydrolysis to the most bioactive derivatives, i.e., ITC and indoles.

The results collected in Table 2 and their graphic presentation (Fig. 2) clearly show that the conversion rate of GLs to ITC and indoles varied significantly between individual parts of investigated Brassica plants. With the exception of radish, ITC and indoles were the most abundant GL hydrolysis products in edible parts: 72.80% in white cabbage leaves; 59.08% in Brussels sprouts heads, 33.94% in Savoy cabbage leaves. Only radish sprouts were rich in these bioactive derivatives (conversion rate − 42.5%); the sprouts of other three plants contained mostly nitriles and epithionitriles. Hydrolysis products of indolic GLs were detected in their unconjugated form in amounts smaller than 50% of total indolic GLs; the remaining portion probably formed other oligomers than 3,3′-diindolylmethane [61] or reacted with ascorbigen [62] not detected in our analytical system. To date, the determination of conversion rate of GLs to degradation products has been performed only by few research groups. Similarly to our findings, De Nicola et al. showed that there was a difference in conversion rate of GLs to ITC in sprouts of various Brassica species from 18.7% in broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italic) 68.5% in kale (Brassica oleracea var. sabellica), up to 96.5% in Daikon (Raphanus sativus var. Longipinnatus) [63]. In studies on eight varieties of radish carried out by Hanlon and Barnes, the calculated conversion of GLs to ITC oscillated in sprouts from 17 to 69% and in bulbs from 6% to 44% [59]. In our studies, this value for radish sprouts and bulb was 42.5% and 5.74%, respectively.

Percentile conversion rate of glucosinolates to breakdown products: isothiocyanates and indoles, nitriles, epithionitriles and other derivatives that include various products of degradation as well as not degraded GLs. All values were calculated on the basis of data given in Table 2

Myrosinase activity seemed less variable (from 0.31 to 1.38 U/g dw) than the contents of its substrates. The conversion rate of GLs to ITC and indoles was not clearly correlated with myrosinase activity. For instance, in the case of Brussels sprouts, a very weak inverse correlation between this enzyme activity and conversion rate to bioactive derivatives was observed (Pearson coefficient − 0.63). In the case of Savoy cabbage, some positive correlation of these parameters could be seen (Pearson coefficient 0.6), while for white cabbage there was no correlation (Pearson coefficient − 0.23). Our previous study on broccoli, mustard and cabbage sprouts has also shown that low GLs degradation to ITC at the level of 1% cannot be ascribed to the lack of MYR activity, which was on the level from 0.8 to 1.3 U/g dw [54]. Moreover, at least some sprouts exhibit even higher or comparable activity of myrosinase as mature forms of the plants [52].

Cytotoxicity

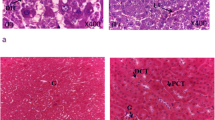

For determination of cytotoxicity, the human colon cancer cell line HT29 was chosen as a model of alimentary tract. The growth inhibition results are presented as Accumulated Survival Index (ASI) calculated as the sum of areas under the cell growth curves for each time of exposure of cells. Higher concentration of ITC/indoles in the sample led to the increase of cytotoxicity (lower ASI) (Fig. 3). The inverse correlation was found for the samples of Savoy cabbage and white cabbage (Pearson coefficient − 0.97 and − 0.98, respectively), but it was not the case for radish and Brussels sprouts. It can be explained that cabbages were rich in sinigrin (SIN) and gluconasturtiin (GST), that were hydrolysed to allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) and phenethyl isothiocyanate (PETIC), respectively, whereas in Brussels sprouts, GST and in radish SIN and GST were not detected. In addition, in radish samples, only two GLs were detected, the predominant: glucoraphanin (GRE) and glucoraphasatin (GRH), whose concentration was correlated with ASI (Pearson coefficient − 0.89). However, it appears that it was not related as such with concentration of ITC and indoles (Pearson coefficient − 0.47), but rather to nitriles (Pearson coefficient − 0.88). This result contrasts other recent reports, which suggest that mainly ITC are responsible for cytotoxicity in in vitro [64] and in vivo models [65]. Recently, it was shown that the differences in HPLC fingerprints obtained for cruciferous plant extracts, indicating the presence of different chemical constituents, were mirrored by the varying antiproliferative activity against the HCT116 cell line [66]. In the case of Brussels sprout samples, the strongest inhibition of HT29 cell growth was observed for heads and it seemed associated with the concentration of degradation products of indolic glucosinolates: GBS, 4-OH-GBS, 4-OMe-GBS and neo-GBS. Especially, for the latter, there are a number of reports demonstrating its genotoxicity and mutagenicity [36,37,38,39,40].

Cytotoxic effect induced by Brassica extracts in HT29 cells evaluated by MTT assay. The results are presented as Accumulated Survival Index (ASI) calculated as the sum of areas under the cell growth curves for each time of cells’ exposure (3–72 h) on Brassica extracts (0.25 ÷ 6.25 mg of dw/mL). All results presented are means ± SD of three independent experiments carried out in triplicates. In all cases SD ≤ 10

The ability to induce DNA damage

Covalent DNA modification in a cell-free system

The restriction analysis method can provide comprehensive knowledge about the ability of low-molecular weight compounds to bind covalently with DNA, including recognition of preferential binding site(s) [58]. The water extracts obtained from individual parts of Brassica plants displayed a variable ability to cause covalent DNA modification in cell-free system. In the case of white cabbage, the components of root and seed extracts modified DNA to the highest extent (Fig. 4). However, it was not possible to correlate this result neither with ITC nor with GL concentration. The similar level of ITC concentration was observed in leaves (4.88 µmol/g dw), roots (5.51 µmol/g dw) and seeds (4.14 µmol/g dw), but there was no inhibition of cleavage by restriction enzymes. In addition, the highest concentration of GLs was detected in sprouts, and again there was no effect of DNA modification. In the case of all extracts from individual parts of Brussels sprouts, the increased ability to cause DNA damage was shown. The strongest effect was determined for sprouts, where the total inhibition of enzymatic cleavage was observed and seeds, where total DNA degradation occurred. In both situations, the concentration of progoitrin (PRO) was high (seeds 13.09 and sprouts 5.51 µmol/g dw). Within the parts of Savoy cabbage and radish, that exhibited the smallest diversity when it comes to GL composition, the increase of DNA modification was also observed. However, it is difficult to find any significant link between GLs/ITC composition and effect on DNA. This may indicate the crucial role of environmental factors such as pH, redox conditions etc. Common for almost all extracts was the preferable site of DNA modification, which was AT base pairs (recognized by enzyme Tru1I). This may point to the nucleophilic nature of modifiers. Further interesting observation to be highlighted is that parts, which are recognized as edible ones, i.e., leaves of white and Savoy cabbages, heads of Brussel sprouts and bulb of radish, caused the lowest DNA modification in our experimental cell-free system, compared to parts regarded as non-edible.

Restriction analysis of covalent modification of DNA amplicon resulting from the treatment with Brassica extracts studied. DNA amplicon (695 bp) was incubated for 2 h at 37 °C with the extracts. Unbound compounds were removed before enzymatic digestion by extraction with chloroform:isoamyl alcohol 24:1 [v/v]. DNA fragments were generated as a result of endonucleolytic cleavage of DNA amplicon by restriction enzymes HpaII (GC specific) or Tru1I (AT specific). For the cleavage control, water was used instead of plant extracts. To avoid unspecific DNA degradation, myrosinase was removed from the extracts by ultrafiltration (MWCO 10 kDa)

In the next stage of this study, the ability of compounds present in the water extracts from the sprouts and the edible parts of investigated Brassica species to modify DNA after metabolic activation with S9 microsomal fraction isolated from rat liver was examined. The S9 fraction is enriched in cytochrome P450, thus phase I detoxification enzymes involved in activation of many xenobiotics. The obtained results did not show unequivocally that metabolic activation increases the ability of DNA modification (Fig. 5). Only the extract from white cabbage leaves increased significantly the inhibition of enzymatic cleavage. However, in none of the cases, the decrease of such an effect was observed.

Restriction analysis of covalent modification of DNA amplicon resulting from the treatment with Brassica extracts studied following their metabolic activation. For metabolic activation, Brassica extracts were incubated with rat liver microsomal fraction S9 for 15 min at 37 °C. Then, the extracts were mixed with DNA amplicon (2.5 ng/µL) and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Microsomal proteins and unbound compounds were removed by thermal heating (15 min, 55 °C) and extraction with chloroform:isoamyl alcohol 24:1 [v/v]. DNA fragments were generated as a result of endonucleolytic cleavage of DNA amplicon by restriction enzymes HpaII (GC specific) or Tru1I (AT specific). To avoid DNA degradation, myrosinase was removed from plant extracts studied by ultrafiltration (MWCO 10 kDa)

DNA fragmentation in eukaryotic cell culture

The influence of plant extracts studied on genetic material integrity in eukaryotic cell line HT29 was evaluated by comet assay. The obtained results showed that water extracts from seeds of investigated Brassica species displayed the highest ability to cause DNA fragmentation. It varied from 16.7% of DNA in comet tail for Savoy cabbage; 22.8% for white cabbage; 24.6% for Brussels sprouts to 37.20% for radish sprouts (Fig. 6). In addition, extracts from sprouts (with the exception of radish sprouts) and from heads of Brussels sprouts caused slight increase of % DNA in comet tail (± 10%) compared to other parts. However, this damage was observed only for 3-h long incubation at a relatively high concentration of 2.5 mg of dw/mL, for which only in the case of radish seed extract, the cell growth was inhibited. Thus, it can be presumed that 3 h period of exposure was sufficient to induce DNA fragmentation, but not to repair DNA. The strongest decrease in HT29 cell number in this series of experiments was determined for the extracts from radish seeds and sprouts, white cabbage stump and leaves and Savoy cabbage seeds for 18 h incubation at the concentration of 0.5 mg of dw/mL. These samples tended to be characterized by high amounts of ITC and indoles and/or substantial rate of GL conversion to these bioactive degradation products. Other researchers in in vivo studies demonstrated that cabbage extract (Brassica oleracea L. var. acephala) did not induce DNA strand breaks in mouse cells, neither was genotoxic [67]. Human studies showed that ITC and ITC-rich products induced DNA damage upon short-term treatment, but that damage disappeared quickly and without affecting DNA base excision repair [68].

Genotoxic effect (right charts) and cell growth inhibition (left charts) induced by Brassica water extracts at concentration of 0.5 or 2.5 mg/mL applied to HT29 cells for 3 or 18 h. The ability to induce DNA fragmentation was determined by comet assay. As negative control water (% of DNA in comet tail ≤ 8) and as positive control 450 µM H2O2 were used (% of DNA in comet tail ≥ 50%). Growth inhibition determinations are given as % of control assuming the number of non-treated cells as 100%. The cell numbers were evaluated first just after incubation with plant extracts and a second time after 48 h long post-incubation with fresh medium (+ 48 h). All results presented are means ± SD of three independent experiments carried out in duplicates

Mutagenicity in prokaryotic cell culture

There are reports indicating that Brassica vegetables contain compounds that may induce point mutations. For example, it has been shown almost two decades ago that crude juice from these plants as well as phytopharmaceutical preparations caused a dose-dependent mutagenicity in Salmonella typhimurium TA98 and TA100 strains [69]. The strongest effect was observed for Brussels sprouts. A similar effect was also observed for broccoli homogenate [70]. Although the composition of the mentioned samples was not evaluated, the mutagenicity was attributed to GLs and their degradation products. However, in both studies highly concentrated juices were used in which histidine concentration was high, up to 75 µg/mL, which might have led to false-positive results [71, 72]. The mutagenic effects generated in Ames test by allyl [73], phenethyl [69] and methyl [74] ITC have been also reported. The recent studies have indicated that derivatives of indolic GLs: neo-GBS, 4-OH-GBS and 4-OMe-GBS, were responsible for mutagenicity of Brassica species in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells [36,37,38]. Moreover, the level of neo-GBS mutagenicity was comparable with that of typical carcinogens such as benzo(a)pyrene and 2-acetylaminofluorene. In our study, the mutagenic effects were assessed for S. typhimurium strains: TA98 and TA100 with or without rat liver microsomal fraction S9 (Fig. 7). The induction of mutations was not observed in the case of TA98 strain and the presence of S9 seemed rather to inactivate the most mutagenic components present in some extracts. In TA100 strain without S9 fraction, the mutagenicity of several extracts was detected. These were parts of Brussels sprouts: heads (18.8 revertant colonies per plate) and sprouts (11.5 revertant colonies per plate), where this effect could be associated with high concentration of neo-GBS in these parts: 1.19 µmol/g dw and 0.46 µmol/g dw, respectively. These indolic GLs were found also in the parts of white and Savoy cabbage, for which also the slight increase of revertant colonies was seen. The exception was the extract from Savoy cabbage roots in which the highest concentration of neo-GBS was determined (2.95 µmol/g dw), but its mutagenicity did not reach the threshold.

Mutagenic activity of water extracts obtained from individual parts or stages of growth of Brassica species by a microplate version of Ames test against two Salmonella typhimurium strains: TA98 and TA100 with or without rat liver microsomal fraction S9. The values are means ± SD of 6 independent determinations. The acceptable values of negative (for TA100 − S9 ≤ 12; for TA100 + S9 and TA98 ± S9 ≤ 8 revertant colonies per plate) and positive control (for all strains ± S9 ≥ 25 revertant colonies per plate) were obtained as recommended by the test manufacturer

Discussion

The research on Brassica vegetables mostly considers edible parts of these plants. Our study focused on plant material obtained from different individual parts or stages of growth of Brassica species. Such an approach revealed, that there are significant differences in GL composition and their conversion rate to bioactive derivatives within not only one species, but even the same plant (Tables 1, 2). Understanding of both these elements is crucial, because the preferential degradation of GLs to ITC and indoles is believed to determine the health-beneficial potential of Brassica plant material [21]. We have shown before that the extract from white cabbage sprouts, in which the conversion rate of GLs to ITC and indoles, was at the level of 1% did not induce detoxification enzymes in human colon cancer HT29 cell line, while such an induction was clearly seen for the leaf extract from the same plant, where 72% of GLs were converted to these biologically active derivatives [54]. The presented here results confirmed the association between cytotoxicity and total concentration of ITC and indoles; only for samples with high conversion rates of GLs to ITC and indoles cytotoxic effect was observed (Fig. 3). In addition, for a number of other cancer cell lines such as lung, stomach, breast, colon, prostate cancer, it has been reported that the composition of ITC influenced the cell growth [1,2,3,4,5]. Moreover, red cabbage extract was demonstrated to selectively inhibit proliferation of HeLa and HepG2 cell lines, but did not have such an effect on normal cell PBMC [75]. This finding is extremely important for cancer chemoprevention, as it demonstrates the selectivity of ITC towards cancer cells.

The presented results also point to the fact that the efficient conversion of GLs to ITC and indoles depends not only on myrosinase activity, which was preserved in all samples examined (Table 2). The low GL conversion to ITC and indoles as in our study, especially for sprouts of white cabbage (0.72%), Brussels sprouts (3.29%) and savoy cabbage (5.43%), was also reported for broccoli and mustard [54]. However, it was not the case for radish (42.50%) and for Daikon (96.50%) [63]. Most probably, this diversity results from the changeable activity of additional enzymes such as ESP or NSP-like proteins. They react with the intermediary thiohydroximate sulfonate and redirect GL degradation towards other than ITC derivatives [59]. There are many studies showing how storage or processing influence formation of GL derivatives [76,77,78,79]. However, the issue of how additional proteins such as epithiospecifier modifier protein (ESM) [9] nitrile-specifier proteins (NSP) [8], thiocyanate-forming protein (TFP) [80] and epithiospecifier proteins (ESP) [81, 82], influence enzymatic hydrolysis has not been specifically addressed. Only recently Hanschen et al. [83], has identified ESP and NSP to favour nitrile formation, whereas the epithiospecifier modifier protein (ESM) to promote ITC formation.

As regards the toxicological part of our study, it could be presumed that cytotoxic activity of extracts obtained from individual parts of Brassica vegetables can be influenced by several factors. Our previous research on Brassica species sprouts, indicated that conversion rate decisive for the concentration of ITC/indoles is the factor directly affecting biological activity of plant extracts; their cytotoxicity and efficacy in the induction of detoxification enzymes [54]. The current, not always convincing, correlations between ITC/indoles content and cell growth inhibition suggest that these interdependencies are not necessarily so simple. One piece of information that is missing is the abundance of individual ITCs or indoles that most probably differ in biological activity. The same conclusion seems to hold in the case of experiments on genotoxic effects.

The presented results of the restriction analysis (Fig. 4) suggest that compounds present in the investigated extracts may modify DNA in a cell-free system, though it was not possible to clearly pinpoint the relationship between GLs/ITC content or composition and the ability of covalent modification of DNA besides progoitrin (PRO). The presence of the latter compound, which is a precursor of goitrin (responsible for decreasing level of thyroid hormones) lead to the increase of DNA damage. However, it must be remembered that at least some of the considered bioactive components are not stable compounds. Progoitrin under the influence of nitrite in the acidic environment may be converted to N-nitroso-oxazolidon with proven mutagenic properties [84]. Other phytochemicals present in the investigated extracts may interact with the matrix, e.g., nitrates, iron ions or amino acids, under the influence of which they can undergo a series of chemical reactions such as oxidation, reduction with altered chemical properties [49, 76].

The presence of indolic GLs and products of their enzymatic degradation resulted in the enhanced mutagenic effect in Ames test (Fig. 7). However, the cytochrome P450 isoenzymes seem to be able to reduce markedly the occurrence of mutagenic derivatives. This is consistent with the results of another research group [69] and somewhat contradict our restriction analysis results. However, the latter method gives no opportunity for further chemical transformations, in contrast to bacterial or eukaryotic cellular systems. Products of indolic GLs degradation, like many aromatic alcohols, heterocyclic amines, aromatic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [85] may be activated via conjugation with sulfuric acid catalyzed by SULTs, the enzymes belonging to second detoxification phase [38]. This metabolic pathway can often lead to the formation of reactive metabolites, including ultimate carcinogens and mutagens [86, 87] as was confirmed in in vitro and in vivo studies for N-methoxy-indole-3-carbinol (NI3C), a compound indicated as responsible for genotoxic effects of Brassica plants [36,37,38]. It was established that NI3C forms DNA adducts by nucleophilic substitution mainly with purine bases [39, 40]. However, the results of our comet assay experiments indicated that bioactive derivatives of GLs did not lead to persistent strands breaks or disintegration of DNA (Fig. 6). The increase of % DNA in comet tail was observed only for seed extracts after 3 h incubation and it was not convincingly related to the abundance of any specific components of extracts. Similarly, other studies showed that Brassica plants did not affect DNA integrity of mouse cells [67]. Human population studies revealed that high doses of ITC may lead to short-term DNA damage, but this was reversed quickly by DNA base excision repair [68]. In terms of consumer safety, derivatives of indolic neo-GBS that form DNA adducts with high efficiency, should in long-term perspective be avoided, at least until their safety is not unequivocally confirmed.

Conclusions

In the light of our study, consuming edible parts of Brassica vegetables does not seem to be of risk for the consumers. In contrary, health-beneficial anti-carcinogenic and anti-inflammatory effects are associated with the high conversion of GLs to ITC and indoles. However, depending on the part plant, the composition of GLs may vary and activity of specifier proteins may alter the conversion rate of GLs to ITC/indoles resulting in the formation of less active or even more toxic derivatives. Therefore, definitely more attention should be paid to dietary supplements. These phytopharmaceuticals may be produced from regarded as non-edible parts of Brassica vegetables or different stages of growth. They are rarely subjected to toxicological evaluation before launch into the market. In best-case-purely-beneficial scenario, concentration of non-mutagenic GLs is high and activity of myrosinase is preserved. However, if conversion of GLs to ITC/indoles is inhibited for any reason, then health-promoting effect will be reduced and limited to GL autohydrolysis or hydrolysis by intestinal microflora. In the worst-case scenario, the concentration of neoglucobrassicin and its derivatives will be high, which may increase risk of triggering carcinogenic processes. Our results suggest that Brassica plant extracts do not pose big genotoxic risk; however, there may be expected substantial variability between plant samples and thus toxicological assessment of concentrated preparations intended for human consumption is needed.

Abbreviations

- 4-OH-GBS:

-

4-Hydroxyglucobrassicin

- 4-OMe-GBS:

-

4-Methoxyglucobrassicin

- AITC:

-

Allyl isothiocyanate

- BITC:

-

Benzyl isothiocyanate

- ESM:

-

Epithiospecifier modifier protein

- ESP:

-

Epithiospecifier proteins

- GBS:

-

Glucobrassicin

- GIB:

-

Glucoiberin

- GIV:

-

Glucoiberverin

- GL(s):

-

Glucosinolate(s)

- GNA:

-

Gluconapin

- GRA:

-

Glucoraphanin

- GRE:

-

Glucoraphenin

- GRH:

-

Glucoraphasatin

- GSH:

-

Glutathione

- GST:

-

Gluconasturtiin

- I3C:

-

Indole-3-carbinol

- ITC:

-

Isothiocyanates

- MYR:

-

Myrosinase

- neo-GBS:

-

Neoglucobrassicin

- NI3C:

-

N-Methoxy-indole-3-carbinol

- NSP:

-

Nitrile-specifier proteins

- PEITC:

-

Phenethyl isothiocyanate

- PRO:

-

Progoitrin

- SFN:

-

Sulforaphane

- SIN:

-

Sinigrin

- TFP:

-

Thiocyanate-forming protein

References

Verhoeven DT, Goldbom RA, van Poppel GA (1996) Epidemiological studies on Brassica vegetables and cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 5:733–748

Tram KL, Gallicchio L, Boyd K, Shiels M, Hammond E, Tao X, Chen L, Robinson KA, Caulfield LE, Herman JG, Guallar E, Alberg AJ (2009) Cruciferous vegetable consumption and lung cancer risk: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 18:184–195

Terry P, Wolk A, Persson I, Magnusson C, Smith-Warner SA, Willet WC, Spiegelman D, Hunter D (2001) Brassica vegetables and breast cancer risk. JAMA 285:2975–2977

Kristal AR, Lampe JW (2002) Brassica vegetables and prostate cancer risk: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Nutr Cancer 42:1–9

Liu B, Mao Q, Cao M, Xie L (2012) Cruciferous vegetables intake and risk of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Urol 19:134–141

Mérrilon JM, Ramawat KG, Gopal K (eds) (2017) Glucosinolates. Reference series in phytochemistry, Springer International Publishing Switzerland

de Torres ZM, Grant M, Bones A, Bennett R, Yin SL, Kissen R, Rossiter J (2005) Characterisation of recombinant epithiospecifier protein and its overexpression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 66:859–867

Wittstock U, Agerbirk N, Stauber EJ, Olsen CE, Hippler M, Mitchell-Olds T, Gershenson J, Vogel H (2004) Successful herbivore attack due to metabolic diversion of a plant chemical defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:4859–4864

Zhang Z, Ober J, Kliebenstein D (2006) The gene controlling the quantitative trait locus epithiospecifier modifier 1 alters glucosinolate hydrolysis and insect resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18:1524–1536

Burow M, Wittstock U (2009) Regulation and function of specifier proteins in plants. Phytochem Rev 8:87–99

Williams D, Critchley C, Pun S, Chaliha M, O’Hare T (2009) Differing mechanisms of simple nitrile formation on glucosinolate degradation in Lepidium sativum and Nasturtium officinale seeds. Phytochem 70:1401–1409

Fahey JW, Zalcmann AT, Talalay P (2001) The chemical diversity and distribution of glucosinolates and isothiocyanates among plants. Phytochem 56:5–51

Piekarska A, Bartoszek A, Namieśnik J (2010) Biofumigation as an alternative method of crop protection. Ecol Chem Eng 17:527–547

Grubb CD, Abel S (2006) Glucosinolate metabolism and its control. Trends Plant Sci 11:89–100

Wenga J-R, Tsai C-H, Kulpc SK, Chenc C-S (2008) Indole-3-carbinol as a chemopreventive and anti-cancer agent. Cancer Lett 262:153–163

Clarke JD, Dashwood DH, Ho E (2008) Multi-targeted prevention of cancer by sulforaphane. Cancer Lett 269:291–304

Agerbirk N, De Vos M, Kim JH, Jander G (2009) Indole glucosinolate breakdown and its biological effects. Phytochem Rev 8:101–120

Surh YJ, Na HK (2008) NF-κB and Nrf2 as prime molecular targets for chemoprevention and cytoprotection with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant phytochemicals. Genes Nutr 4:313-317

Nair S, Li W, Kong AN (2007) Natural dietary anticancer chemopreventive compounds: redox-mediated differential signaling mechanisms in cytoprotection of normal cells versus cytotoxicity in tumor cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin 28:459–472

Herr I, Büchler MW (2010) Dietary constituents of broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables: implications for prevention and therapy of cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 36:377–383

Latté K, Appel KE, Lampen A (2011) Health benefits and possible risks of broccoli—an overview. Food Chem Toxicol 49:3287–3309

Dinkova-Kostova AT, Kostov RV (2012) Glucosinolates and isothiocyanates in health and disease. Trends Mol Med 18:337–347

Hanlon N, Coldham N, Gielbert A, Kuhnert N, Sauer MJ, King LJ, Ioannides C (2008) Absolute bioavailability and dose-dependent pharmacokinetic behavior of dietary doses of the chemopreventive isothiocyanate sulforaphane in rat. Brit J nutr 99:559–564

Ji Y, Kuo Y, Morris ME (2005) Pharmacokinetics of dietary phenethyl isothiocyanates in rats. Pharmac Res 22:1658–1666

Zhang Y, Callaway EC (2002) High cellular accumulation of sulforaphane, a dietary anticarcinogen, is followed by rapid transporter-mediated export as a glutathione conjugate. Biochem J 364:301–307

Dinkova-Kostova AT, Talalay P, Sharkey J, Zhang Y, Holtzclaw WD, Wang XJ, David E, Schiavoni KH, Finlayson S, Mierke DF, Honda H (2010) An exceptionally potent inducer of cytoprotective enzymes. J Biol Chem 285:33747–33755

Brown KK, Hampton MB (2011) Biological targets of isothiocyanates. Biochim Biophys Acta 1810:888–894

Baillie TA, Slatter JG (1991) Glutathione: a vehicle for the transport of chemically reactive metabolites in vivo. Acc Chem Res 24:264–270

Kassahun K, Davis M, Hu P, Martin B, Baillie T (1997) Biotransformation of the naturally occurring isothiocyanate sulforaphane in the rat: identification of phase I metabolites and glutathione conjugates. Chem Res Toxicol 10:1228–1233

Mi L, Hood BL, Stewart NA, Xiao Z, Govind G, Wang X, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Chung FL (2011) Identification of potential protein targets of isothiocyanates by proteomics. Chem Res Toxicol 24:1735–1743

Drobnica L, Kristian P, Augustin J (1997) The chemistry of the single bond –NCS group. In: Patai S (ed) The chemistry of cyanates and their thio derivatives, vol 2. Wiley

Hanschen FS, Brüggemann N, Brodehl A, Mewis I, Schreiner M (2012) Characterization of products from the reaction of glucosinolate-derived isothiocyanates with cysteine and lysine derivatives formed in either model systems or broccoli sprouts. J Agric Food Chem 60:7735–7745

Nakamura T, Kawai Y, Kitamoto N, Osawa T, Kato Y (2009) Covalent modification of lysine residues by allyl isothiocyanate in physiological conditions: plausible transformation of isothiocyanate from thiol to amine. Chem Res Toxicol 22:536–542

Kumar A, Sabbioni G (2010) New biomarkers for monitoring the levels of isothiocyanates in humans. Chem Res Toxicol 23:756–765

Lewandowska A, Przychodzeń W, Bartoszek A, Kołodziejski D, Namieśnik J, Kusznierewicz B (2014) Isothiocyanates may chemically detoxify mutagenic amines formed in heat processed meat. Food Chem 157:105–110

Baasanjav-Gerber C, Hollnagel H, Brauchmann J, Iori R, Glatt H (2011) Detection of genotoxicants in Brassicales using endogenous DNA as a surrogate target and adducts determined by 32P-postlabelling as an experimental endpoint. Mutagenesis 26:407–411

Baasanjav-Gerber C, Monien B, Mewis I, Schreiner M, Barillari J, Iori R, Glatt H (2011) Identification of glucosinolate congeners able to form DNA adducts and to induce mutations upon activation by myrosinase. Mol Nutr Food Res 55:783–792

Glatt H, Baasanjav-Gerber C, Schumacher F, Monien B, Schreiner M, Frank H, Seidel A, Engst W (2011) 1-Methoxy-3-indolylmethyl glucosinolate; a potent genotoxicant in bacterial and mammalian cells: Mechanisms of bioactivation. Chem-Biol Interact 192:81–86

Schumacher F, Engst W, Monien BH, Florian S, Schnapper A, Steinhauser L, Albert K, Frank H, Seidel A, Glatt H (2012) Detection of DNA adducts originating from 1-methoxy-3-indolylmethyl glucosinolate using isotope-dilution UPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Anal Chem 84:6256–6262

Schumacher F, Florian S, Schnapper A, Monien BH, Mewis I, Schreiner M, Seidel A, Engst W, Glatt H (2013) A secondary metabolite of Brassicales, 1-methoxy-3-indolylmethyl glucosinolate, as well as its degradation product, 1-methoxy-3-indolylmethyl alcohol, forms DNA adducts in the mouse, but in varying tissues and cells. Arch Toxicol 88:823–836

Brown PD, Tokuhisa JG, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J (2003) Variation of glucosinolate accumulation among different organs and developmental stages of Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochem 62:471–481

Velasco P, Soengas P, Vilar M, Cartea MA (2008) Comparison of glucosinolate profiles in leaf and seed tissues of different Brassica napus crops. J Am Soc Hortic Sci 133:551–558

Piekarska A, Kusznierewicz B, Kołodziejski D, Pilipczuk T, Szczygłowska M, Bodnar M, Bączek-Kwinta R, Konieczka P, Namieśnik J, Bartoszek A (2013) The innovative exploitation of Brassica vegetables in health quality food production chain. Acta Hortic 1005:71–85

Kusznierewicz B, Bartoszek A, Wolska L, Drzewiecki J, Gorinstein S, Namieśnik J (2008) Partial characterization of white cabbages (Brassica oleracea var. capitata f. alba). LWT 41:1–9

Kushad MM, Brown AF, Kurilich AC, Juvik AJ, Klein BP, Wallig MA, Jeffery EF (1999) Variation of glucosinolates in vegetable crops of Brassica oleracea. J Agric Food Chem 47:1541–1548

Ciska E, Martyniak-Przybyszewska B, Kozlowska H (2000) Content of glucosinolates in cruciferous vegetables grown at the same site for two years under different climatic conditions. J Agric Food Chem 48:2862–2867

Śmiechowska A, Bartoszek A, Namieśnik J (2010) Determination of glucosinolates and their decomposition products—indoles and isothiocyanates in cruciferous vegetables. Crit Rev Anal Chem 40:202–216

Maldini M, Baima S, Morelli G, Scaccini C, Natella F (2012) A liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry approach to study “glucosinolom” in broccoli sprouts. J Mass Spectrom 47:1198–1206

Bellostas N, Kachlicki P, Sørensen J, Sørensen H (2007) Glucosinolate profiling of seeds and sprouts of B. oleracea varieties used for food. Sci Hortic 114:234–242

Baenas N, Moreno DA, Garcia-Viguera C (2012) Selecting sprouts of Brassicaceae for optimum phytochemical composition. J Agric Food Chem 60:11409–11420

Hanschen FS, Herz C, Schlotz N, Kupke F, Bartolomé Rodríguez MM (2015) The Brassica epithionitrile 1-cyano-2,3-epithiopropane triggers cell death in human liver cancer cells in vitro. Mol Nutr Food Res 59:2178–2189

Piekarska A, Kusznierewicz B, Meller M, Dziedziul K, Namieśnik J, Bartoszek A (2013) Myrosinase activity in different plant samples; optimisation of measurement conditions for spectrophotometric and pH-stat methods. Ind Crop Prod 50:58–67

Zhang Y, Wade K, Prestera T, Talalay P (1996) Quantitative determination of isothiocyanates, dithiocarbamates, carbon disulfide, and related thiocarbonyl compounds by cyclocondensation with 1,2-benzenedithiol. Anal Biochem 239:160–167

Piekarska A, Kołodziejski D, Pilipczuk T, Bodnar M, Konieczka P, Kusznierewicz B, Hanschen FS, Schreiner M, Cyprys J, Groszewska M, Namieśnik J, Bartoszek A (2014) The influence of selenium addition during germination of Brassica seeds on health-promoting potential of sprouts. Int J Sci Food Nutr 65:692–702

Witzel K, Hanschen FS, Klopsch R, Ruppel S, Schreiner M (2015) Verticillium longisporum infection induces organ-specific glucosinolate degradation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front Plant Sci 6:508

Poleska-Muchlado Z, Piekarska A, Kusznierewicz B, Pilipczuk T, Szczygłowska M, Malinowska-Pańczyk E, Konieczka P, Namieśnik J, Bartoszek A (2013) The comparison of biological potential of white cabbage varieties using the Accumulated Survival Index (ASI) concept. Book of abstracts, 595, Eurofoodchem XVII conference, 07-10.05.2013 r., Istanbul, Turkey

Flückiger-Isler S, Kamber M (2012) Direct comparison of the Ames microplate format (MPF) test in liquid medium with the standard Ames pre-incubation assay on agar plates by use of equivocal to weakly positive test compounds. Mutat Res 747:36–45

Kołodziejski D, Brillowska-Dąbrowska A, Bartoszek A (2015) The extended version of restriction analysis approach for the examination of the ability of low-molecular-weight compounds to modify DNA in a cell-free system. Food Chem Toxicol 75:118–125

Hanlon P, Barnes D (2011) Phytochemical composition and biological activity of 8 varieties of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) sprouts and mature taproots. J Food Sci 76:185–192

Wiesner M, Schreiner M, Glatt H (2014) High mutagenic activity of juice from pak choi (Brassica rapa ssp. chinensis) sprouts due to its content of 1-methoxy-3-indolylmethyl glucosinolate, and its enhancement by elicitation with methyl jasmonate. Food Chem Toxicol 67:10–16

Grose KR, Bjeldanes LF (1992) Oligomerization of indole-3-carbinol in aqueous acid. Chem Res Toxicol 5:188–193

Hrncirik K, Valusek J, Velisek J (2001) Investigation of ascorbigen as a breakdown product of glucobrassicin autolysis in Brassica vegetables. Eur Food Res Technol 212:576–581

De Nicola G, Bagatta M, Pagnotta E, Angelino D, Gennari L, Ninfali P, Rollin P, Iori R (2013) Comparison of bioactive phytochemical content and release of isothiocyanates in selected Brassica sprouts. Food Chem 141:297–303

Kadir NHA, David R, Rossiter JT, Gooderham NJ (2015) The selective cytotoxicity of the alkenyl glucosinolate hydrolysis products and their presence in Brassica vegetables. Toxicol 334:59–71

Kupke F, Herz C, Hanschen FS, Platz S, Odongo GA, Helmig S, Rodríguez MMB, Schreiner M, Rohn S, Lamy E (2016) Cytotoxic and genotoxic potential of food-borne nitriles in a liver in vitro model. Sci Rep 6:37631

Pocasap P, Weerapreeyakul N (2016) Sulforaphene and sulforaphane in commonly consumed cruciferous plants contributed to antiproliferation in HCT116 colon cancer cells. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 6:119–124

Gonçalves AL, Lemos M, Niero R, de Andrade SF, Maistro EL (2012) Evaluation of the genotoxic and antigenotoxic potential of Brassica oleracea L. var. acephala D.C. in different cells of mice. J Ethnopharmacol 143:740–745

Charron CS, Clevidence BA, Albaugh GA, Kramer MH, Vinyard BT, Milner JA, Novotny JA (2013) Assessment of DNA damage and repair in adults consuming allyl isothiocyanate or Brassica vegetables. J Nutr Biochem 24:894–902

Kassie F, Parzefall W, Musk S, Johnson I, Lamprecht G, Sontag G, Knasmuller S (1996) Genotoxic effects of crude juices from Brassica vegetables and juices and extracts from phytopharmaceutical preparations and spices of cruciferous plants origin in bacterial and mammalian cells. Chem-Biol Interact 102:1–16

Martínez A, Ikken Y, Cambero M, Marín M, Haz A, Casas C, Morales P (1999) Mutagenicity and cytotoxicity of fruits and vegetables evaluated by the Ames test and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazo-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide 1941(MTT) assay. Food Sci Technol Int 5:431–437

Khandoudia N, Portea P, Chtouroua S, Nesslanyb F, Marzinb D, Le Curieux F (2009) The presence of arginine may be a source of false positive results in the Ames test. Mutat Res 679:65–71

Priva MJ, Simmon VF, Mortelamans KE (1991) Bacterial mutagenicity testing of 49 food ingredients gives very few positive results. Mutat Res 260:321–329

Kassie F, Knasmüller S (2000) Genotoxic effects of allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) and phenethyl isothiocyanate (PEITC). Chem-Biol Interact 127:163–180

Kassie F, Laky B, Nobis E, Kundi M, Knasmüller S (2001) Genotoxic effects of methyl isothiocyanate. Mut Res 490:1–9

Hafidha RR, Abdulamir AS, Abu Bakard F, Jaliliane FA, Abasd F, Sekawifa Z (2013) Novel anticancer activity and anticancer mechanisms of Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata f. rubr. Eur J Integr Med 5:450–464

Hanschen F, Platz S, Mewis I, Schreiner M, Rohn S, Kroh L (2012) Thermally induced degradation of sulfur-containing aliphatic glucosinolates in broccoli sprouts (Brassica oleracea var. italica) and model systems. J Agric Food Chem 60:2231–2241

Song L, Thornalley PJ (2007) Effect of storage, processing and cooking on glucosinolate content of Brassica vegetables. Food Chem Toxicol 45:216–224

Deng Q, Zinoviadou KG, Galanakis CM, Orlien V, Grimi N, Vorobiev E, Lebovka N, Barba FJ (2015) The effects of conventional and non-conventional processing on glucosinolates and its derived forms, isothiocyanates: extraction, degradation, and applications. Food Eng Rev 7:357–381

Barba FJ, Nikmaram N, Roohinejad S, Khelfa A, Zhu Z, Koubaa M (2016) Bioavailability of glucosinolates and their breakdown products: impact of processing. Front Nutr 3:24

Burow M, Bergner A, Gershenzon J, Wittstock U (2007) Glucosinolate hydrolysis in Lepidium sativum––identification of the thiocyanate-forming protein. Plant Mol Biol 63:49–61

de Torres ZM, Grant M, Bones A, Bennett R, Yin SL, Kissen R, Rossiter J (2005) Characterisation of recombinant epithiospecifier protein and its overexpression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochem 66:859–867

Foo H, Grönning L, Goodenough L, Bones A, Danielsen BE, Whiting D, Rossiter J (2000) Purifcation and characterisation of epithiospecifer protein from Brassica napus: enzymic intramolecular sulphur addition within alkenyl thiohydroximates derived from alkenyl glucosinolate hydrolysis. FEBS Lett 468:243–246

Hanschen FS, Klopsch R, Oliviero T, Schreiner M, Verkerk R, Dekker M (2017) Optimizing isothiocyanate formation during enzymatic glucosinolate breakdown by adjusting pH value, temperature and dilution in Brassica vegetables and Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci Rep 7:40807

Lfithy J, Carden B, Friederich U, Bachmann M (1984) Goitrin—a nitrosatable constituent of plant foodstuffs. Experientia 40:452–453

Zheng W, Xie D, Cerhan JR, Sellers TA, Wen W, Folsom AR (2001) Sulfotransferase 1A1 polymorphism, endogenous estrogen exposure, well-done meat intake, and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 10:89–94

Surh YJ (1998) Bioactivation of benzylic and allylic alcohols via sulfoconjugation. Chem Biol Interact 109:221–235

Glatt H, Meinl W (2004) Pharmacogenetics of soluble sulfotransferases (SULTs). Arch Pharmacol 369:55–68

Acknowledgements

The project was financed by the National Science Centre of Poland according to the decision nr DEC-2013/09/N/NZ9/01275.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethics requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kołodziejski, D., Piekarska, A., Hanschen, F.S. et al. Relationship between conversion rate of glucosinolates to isothiocyanates/indoles and genotoxicity of individual parts of Brassica vegetables. Eur Food Res Technol 245, 383–400 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-018-3170-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-018-3170-9