Abstract

Use of microfluidic devices in the life sciences and medicine has created the possibility of performing investigations at the molecular level. Moreover, microfluidic devices are also part of the technological framework that has enabled a new type of scientific information to be revealed, i.e. that based on intensive screening of complete sets of gene and protein sequences. A deeper bioanalytical perspective may provide quantitative and qualitative tools, enabling study of various diseases and, eventually, may offer support for the development of accurate and reliable methods for clinical assessment. This would open the way to molecule-based diagnostics, i.e. establish accurate diagnosis and disease prognosis based on identification and/or quantification of biomacromolecules, for example proteins or nucleic acids. Finally, the development of disposable and portable devices for molecule-based diagnosis would provide the perfect translation of the science behind life-science research into practical applications dedicated to patients and health practitioners. This review provides an analytical perspective of the impact of microfluidics on the detection and characterization of bio-macromolecules involved in pathological processes. The main features of molecule-based diagnostics and the specific requirements for the diagnostic devices are discussed. Further, the techniques currently used for testing bio-macromolecules for potential diagnostic purposes are identified, emphasizing the newest developments. Subsequently, the challenges of this type of application and the status of commercially available devices are highlighted, and future trends are noted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The technological advances of the last century enabled scientific clarification of several major mysteries of life, i.e. all organisms are made of cells, which are chemical systems composed mainly of complex carbon chains and sharing the same information system [1]. A deeper insight into the cells, on the nanometre scale, highlights the main components: nucleic acids—the source of genetic information—and proteins—the main executive molecules. Elucidation of the way in which sub-cellular components work together to form functional cells and organisms will enable complete understanding of cellular processes and the way the cell responds to the environment [1]. Eventually, the deciphering of cellular processes will help us to understand disease mechanisms, and to find the proper way to diagnose and cure them.

Fast assessment of bio-macromolecules such as proteins, peptides, over/under expression of gene markers, and gene mutations can be extremely valuable information for diagnosis and prognosis of several pathologies [2, 3]. For example, the presence of various cancers and diseases is sometimes linked to abnormal concentrations of specific proteins [4]. Also, investigation of nucleic acid sequences, especially for identification of a genetic mutation, is a practical approach used to identify or confirm different pathologies [4, 5]. In infectious diseases, the main cause of mortality in developing countries and one of the major causes in developed countries [6], the pathogenic source becomes even more traceable and is perfect candidate for molecule-based diagnostics. In all these situations, complex samples, available in small amounts, have to be processed rapidly, preferably near the patient’s bedside, and a clinically significant response has to be obtained. In this case, the medical response can be adjusted more rapidly to the patient’s reaction, enabling a personalized medical approach.

For years, consistent efforts have been made to develop analytical applications enabling fast, accurate, precise, and reproducible insights into the world of macro-biomolecules. Pandora’s box in the biosciences was opened around the 1990s, when advances in incremental technology, the miniaturization boom, and progress in engineering emerged in microfluidic devices [7]. Microfluidics can be regarded as a framework, an enabling technology [8] related to fluid flowing in channels of micro or nano-size, offering the possibility of developing products with better performance and additional features (Fig. 1). The dawn of expectations started with the concept of the micro-total analytical system (μTAS) [9]. μTAS was supposed to perform automatic sampling, sample transport, any necessary chemical reactions, and detection on a single, miniaturized, platform [9]. The concept was declared the state-of-art strategy, because of its amazing advantages, i.e. faster separations, shorter transport time, lower sample and reagent consumption and the possibility of multi-component testing under the same conditions [9].

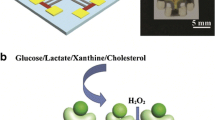

Several commercially available microfluidics-based devices used for bio-analytical purposes a. Dynaflow System for ion-channel drug discovery (Cellectricon, Mölndal, Sweden); b. LC–MS microfluidics-based chip (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA); c. Nanotiter plates (microfluidic ChipShop, Jena, Germany); d. 15-cycles continuous-flow polymerase chain reaction (PCR) chip (microfluidic ChipShop); e. 96-sample Sentrix Array Matrix (top) and the multi-sample Sentix Bead Chips (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA); f. Disposable chip for generation of picoliter-volume droplets. Each droplet is further used as a PCR reactor (RainDance Technologies, Lexington, MA, USA)

Since the concept of μTAS was announced, there was an explosive interest on the topic, as shown by the huge amount of papers published so far (7745 accordingly to Scopus database, December 2009), of which almost a fifth is related to the life sciences and medical applications (Fig. 2). Over 70% of all papers on the use of microfluidic devices in the life sciences and medicine are targeted on the characterization of biological systems at the molecular level (Fig. 2). The use of microfluidics was perceived as a possible new dimension in bioanalysis. Microfluidic device-based applications shifted the perspective from the general to the cellular and sub-cellular level and enabled the measurement of molecular variation, the dynamics of seconds-long processes, and bio-macromolecular motion [10]. Valuable bio-molecules were isolated, characterized, quantified, and used to explore interactions with other molecules.

Once the euphoria generated by this promising new solution for old unsolved problems became transformed into a chase for application development, a long list of practical problems was revealed. Because a completely new platform was to be developed, choice of the material and the design of the device were the first problems to occur. Further, applications development revealed that the technology required for production of fully integrated devices was not yet mastered. Also, solutions were needed for the extremely sensitive and miniaturized detection systems, while the complexity of samples emphasized the need for sample clean-up or enrichment of analytes of interest. Some technical problems have already been answered, or at least better understood, while several are still open challenges for the technology available.

This review tries to give an overview, from an analytical perspective, of the impact of microfluidics on the detection and characterization of the bio-macromolecules involved in pathological processes, focussing especially on those with a high potential to be developed as diagnostic devices for infectious diseases and cancer. Given the importance of the field, in which volume of literature doubles every four years, manuscripts mainly published during the last three years are discussed.

We will first review the main requirements for developing diagnostically relevant applications. Further, on-chip sample treatment, on-chip PCR, separation, and immunoaffinity techniques, and detection schemes will be identified. Subsequently, the challenges of this type of application and the status of commercially available devices will be discussed. We will conclude with future opportunities of the research. Throughout the review, examples of the newest research, promising approaches, and opportunities will be emphasized.

Manuscripts reporting the use of microfluidics for microvascular network chips, the isolation of biomacromolecules on chips, and applications related to cells other than pathogens are beyond the scope of this review. High-density microarrays, although a source of clinically valuable information, are also not included because of disadvantages such as complexity, high cost, lack of robustness, and difficulty of interpretation.

Main requirements for developing diagnostic relevant applications

An impressive amount of research has focused on developing applications that can help medical practitioners achieve faster and more accurate diagnosis, reliably assess disease prognosis, or monitor treatment, on a solid quantitative basis [11]. The final objective would be the development of portable automatic devices able to provide fast laboratory grade results without the need for special reagents. The devices should be able to provide results not only for patient bedside use but also in major public health threats such as pandemics risk and suspicions of biowarfare agents use [12]. The application of μTAS concept would fit perfectly to such an application—a sample of bodily fluid, for example blood, urine, or nasal secretion, is collected and is introduced into the workstation where minimal treatment is applied (e.g. a blood sample is diluted with EDTA to prevent clotting) and separation is performed if necessary (e.g. plasma is separated from whole blood or cells are lysed). Furthermore, multiple analytes are then captured at the receptor site. After washing and introduction of secondary reagents, analyte levels are read using the workstation read out [13].

During the development of molecular miniaturized diagnostics, bioanalysis should provide two solutions:

-

1.

extraction of the analyte of interest from the sample, and

-

2.

conversion of analyte properties into a readable signal.

Finding these solutions would be equivalent to translation of the science into practical applications dedicated to mass consumers and health practitioners.

The technology available today has enabled the development of a number of biosensors for cancer biomarkers analysis, whereas most of the multi-array sensor chips for testing at or near the patient bedside are still in development or research stage [3]. Unfortunately, the use of proteins for diagnostic tests is limited by current detection methods, which are only sensitive enough when the disease is significantly advanced and protein concentrations have already reached critical thresholds [4]. The development of microfluidic devices enabling differential proteomic profiling and detection of a panel of several proteins has the potential to revolutionize the biomedical research and to increase the sensitivity of tests [14]. Viral detection is another field where the use of microfluidic devices has the potential to improve detection limits, simplify procedures, and reduce the time needed for confirmation of a viral infection [15].

Current techniques used to study and/or identify macro-biomolecules for diagnostic relevant applications

Several macro-biomolecules are routinely tested for diagnostic purposes using a number of classical molecular biology tools, for example slab gel electrophoresis or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Usually, the methods involve multiple manual steps, with several critical steps and long incubation times, and use large volumes of buffers and expensive reagents available in minute amounts (antibodies). For a more precise assessment, blotting can be performed by transferring the bands from the slab gel electropherogram to a nitrocellulose or Nylon membrane using a high electric field. The membrane containing the transferred bands is then incubated with functionalized antibodies for specific proteins. Detection is generally achieved using functionalized antibodies, either radioactively or fluorescently labelled or covalently bound to an enzyme the activity of which can be easily measured.

Nucleic acids have a huge advantage over proteins, because use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) enables signal increases through target-based amplification and reliable detection of just a few copies of nucleotide sequences [2, 16]. For proteins, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is the most used technique. Limits of detection (LOD) for ELISA are in the picomolar range, but large volumes are needed and the technique is rather complicated involving target capturing by an antibody and sandwiching with a second antibody, which is also responsible for signal generation [2].

Within this context, applications developed using the microfluidic devices would bring portability, higher sensitivity, cost reduction, shorter analysis time, and less laboratory space consumption, overcoming most of the inconveniences of the classical tools of molecular biology [17].

In microfluidics, the reduction in size results in a high surface area-to-volume ratio and surface effects become extremely prominent. The physics underlying microfluidic devices has been excellently described by Squires and Quake [18]. The paper emphasizes the variety of phenomena and the manner in which they had been exploited to develop microfluidic devices.

The initial promise of microfluidics—the development of a μTAS that would integrate all analytical operations on a single platform [9]—is only partially fulfilled at the moment. The number of manuscripts reporting the development of a complete application, integrating sample treatment is equal to or below the number of manuscripts reporting partial applications, for example the analysis of an already processed sample or the development of a method of sample preparation. In this context the integration of the pre-separation sample processing is currently the weakest link [16, 19]. Expectations have become more mature and realistic and the solution has been found by changing the perception of μTAS: the omnipotent chip is now seen as a microfluidics platform, composed of a set of combinable building blocks, where each block performs a single operation [17]. Almost all devices reported in the literature can be further integrated in such a microfluidics platform. This approach enables the implementation of bio-analytical assay in a better, foreseeable and less risky manner [17]. The development of single-unit blocks avoids conflicts between the technical requirements for various operations; for example, in sample treatment high throughput is the main demand whereas for analytical separations high resolution is most important [16].

The transport of samples and reagents in microfluidic channels is performed by routine approaches for separation science, for example high pressure, vacuum, or electrical field. The last is preferred for most applications, either uniform, as in electrophoretic separations, or non-uniform, as in dielectrophoresis in which a force is exerted on a dielectric particle subjected to a non-uniform electric field. Dielectrophoresis is mostly used for analytes such as dielectric particles, without the need for them to be charged. The selectivity of dielectrophoresis can be easily tuned by altering the field frequency. Other researchers are trying to use the magnetic field for controlled transport of paramagnetic particles [20]. An alternative lab-on-a-chip technology is droplet technology, also called digital microfluidics. In this case, the flow is not continuous but as discrete droplets. The devices operate similarly to bench-top equipment, only with a significant volume reduction to the nL range and more automation. Generation and manipulation of droplets are performed in accordance with three main principles—electrowetting, dielectrophoresis, and immiscible-fluid flows. Detailed characterization of different microfluidic platforms and recommendations for selection of the most appropriate approach based on application can be found elsewhere [17].

For analytical purposes, two main approaches are used for separation of the analyte of interest, from the samples—affinity-based separation and capture, based for example antigen–antibody reactions, and physicochemical-based separations, for example capillary electrophoresis (CE) or liquid chromatography (LC).

Sampling and sample treatment

Sampling and even minimal sample preparation, for example separating plasma from whole blood, are performed off-microfluidic device. The main interests in using microfluidic devices for sample treatment are related to the isolation and/or concentration of analytes or the removal of interfering components. Therefore methods involving continuous phase separations should be favoured, because they have no need for careful sample loading [16]. However, the processing of larger sample volumes (sometimes even hundreds of microliters) is still a problem.

Antigen–antibody and streptavidin–biotin affinity are the favourite approaches for isolating target analytes. The isolations are performed within a magnetic field using magnetic beads or in electrical fields using polystyrene beads (Table 1). Sometimes, the successful isolation described in the literature is more a proof of concept shown for standard solutions and not yet tested on real clinical samples (Table 1). A trial for alternative ways to avoid the use of antibodies [31] has been reported, but in some cases the use of immobilized antibodies can result in extremely sensitive devices [32–35]. A very interesting example, with an intended use for single nucleotide polymorphism diagnosis, is presented in Fig. 3. Dielectrophoresis [36], solid-phase extraction (SPE) [21, 37–41] or size-exclusion based separations with nanopores [42] and microfabricated plastic membranes [43] are other possible methods reported for target isolation.

a A photograph of assembled magnetic-bead-based microfluidic system performing on-chip single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping associated with genetic diseases. gDNA is extracted from leukocytes in the DNA extraction /PCR chamber. b A hand-held system including a microfluidic chip, an ASIC controller, a control circuit board, and EMVs has been developed. (Reproduced, with permission, from Ref. [26])

Isolation and concentration is particularly important for proteins, usually present in complex mixtures (for instance in serum there are over 10 000 different types) and in high dynamic ranges (the protein of interest is present at picomolar levels, while less interesting proteins can be present at 30–50 g L−1 concentrations). For the particular case of nucleic acid isolation, commonly used procedures with commercially available kits are cumbersome, and include a substantial number of manual steps. For example, some purification kits require approximately ten pipetting steps, three mechanical mixing steps, six centrifugation steps, and ten tube-transfer steps [44]. The common automation approaches for these tests are benchtop-dependent, and therefore not suited to emerging bedside applications that require compact, automated, and robust operational settings [19]. Still, several successful attempts to automate nucleic acids extraction using microfluidic devices have been reported. A plastic chip has been used for viral RNA extraction from a lysate of mammalian cells infected with influenza A (H1N1) virus [40]. The RNA isolation was achieved by μSPE, by reversible binding of the nucleic acids to silica particles trapped in a porous polymer monolith [40]. The procedure is extremely simple and only requires 10 min. A solid-phase method to isolate PCR-amplifiable genomic DNA from chemically lysed blood cells has also been used [37]. In this case, a porous silicon matrix integrated in the biochip was used to perform the DNA extraction in 20 min [37].

Blood was initially regarded as the main target for the development of diagnostic tests. More and more applications focus on development of tests for less invasive and complex body fluids, for example urine, saliva, or nasal secretions. However, whole blood and plasma samples remain a constant target for sample-preparation devices using DNA extraction [37, 45, 46], pathogen capturing [47], protein depletion [38, 48], or plasma separation from whole blood [49].

Microfluidics may also offer solutions for manipulation of samples ranked as highly bio-hazardous. An interesting application consists in the manipulation and disruption of bacterial cells and viruses in a closed system and with minimum intervention from the operator [37, 39, 47, 50–52]. Dielectrophoresis (DEP) has been used for manipulation and disruption of cells of Bordella pertussiss, a bacterial respiratory pathogen [36], and for capture and lysis of Vaccinia virus particles [51]. The disintegration of the virus outer layer was proved by revealing the damaged and exposed tubules networks by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [51].

Rapid isolation and counting of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) from only 10 μL unprocessed whole blood has been performed on a microfluidic platform [47]. The chip surface was coated with anti-gp120 antibodies to capture HIV by binding to the gp120-glycoprotein on the surface of HIV envelope. The research group that developed the on-chip isolation of HIV intends to develop a rapid (<10 min), handheld, low-cost, and disposable microfluidic HIV monitoring platform for rapid, bedside, clinical HIV monitoring. Another research group reported capture of HIV on a microchip based on CD4+ T-lymphocyte affinity [53].

PCR on a chip

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is possibly the most used tool in molecular biology [1]. It amplifies specific DNA sequences (target) in the presence of a pair of primers that hybridize with the flanking sequences of the target, the four deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), and a heat-stable DNA polymerase [54]. The amplification is performed in cycles of three steps: strand separation, hybridization of primers and DNA synthesis. Each step is isothermal and requires a specific temperature, i.e. 95 °C, 54 °C, and 72 °C, respectively. The amplification is carried out repetitively just by changing the temperature of the reaction mixture [54]. For RNA amplification, either a reverse-transcriptase (RT) PCR approach or a nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA) procedure can be used. NASBA is a transcription-based RNA amplification system, which is more sensitive, “user friendly”, and faster than PCR [55].

As proved also by clinical standards, PCR is an invaluable tool for nucleic acids analysis, especially in viral diseases and cancer diagnosis [56]. Analysis of heterogeneous nucleic acid mixtures is a source of important clinical information, especially in assessment of antiretroviral resistant mutations or early cancer detection [57]. Individually, genotypic investigation of minority viral populations might be a source of valuable information such as the tendency to develop drug resistance.

Integration of PCR on microfluidic platforms reduces cost by reducing reagent volumes to tens of nanolitres. It also reduces complexity by integration of several assay steps into a single device, and reduces the times required for thermocycling [58]. In the current mode of operation of PCR, sample processing, amplification, and analysis of the PCR mixtures are stand-alone operations.

The miniaturization of PCR has the potential to identify the missing link that integrates sample processing with downstream PCR and analysis of PCR mixtures [56]. In this mode, sample manipulation, with potential effects on the measurement, can be tightly regulated and accounted for. Moreover, avoiding conventional extraction and manipulation limits sample loss. The integration of these operations would be beneficial for characterization of cancers at the molecular level, enabling meaningful quantitative assessment of cancer pathogenesis and development of more effective therapy [56]. Miniaturization also brings other potential benefits, for example multi-parallel treatment of a defined numbers of cells, single cell-based analysis, or even single gene analysis [56].

The feasibility of rapid, single-molecule amplification of nucleic acids was established using a microfluidic system developed to enable rapid PCR analysis of individual DNA molecules with precise temperature control [57]. PCR was performed on heterogeneous samples containing synthetic CYP2D6.6 wild-type and mutant templates, on a quartz chip designed to enable adequate mixing by Brownian diffusion after each stage of reagent dispensing. Samples were loaded from a microtitre plate on to the microchip through an integrated capillary, which minimizes the contamination risk. The chip design allowed eight parallel PCR reactions. Thermocycling was performed by heating with nine embedded resistive heaters built from platinum tracers and cooling by recirculating water underneath the chip. The system had an impressive detection set-up comprising two different lasers for excitation, i.e. a 488 nm optically pumped solid-state laser and the 633-nm line of an HeNe laser, a series of dichroic mirrors and band pass filters, and three charged-coupled device (CCD) cameras, each collecting light of a different wavelength, i.e. 515, 550, and 685 nm. Thermocouples and optical DNA melt analysis were used to demonstrate the chip’s ability to rapidly thermocycle. When the desired temperature was 68.5 °C, seven out of the eight channels managed accurate control within a 1° range. The efficiency of amplification was proved by measuring the fluorescence emission resulting from amplification of a 1:1 mixture of wild and mutant templates of CYP2D6.6 using two Taqman probes. The procedure is fast, reproducible and able to amplify a heterogeneous sample containing two templates without mixing the amplification products between templates. Use of the proposed microfluidic setup overcomes the high reagent cost and cumbersome reaction assembly requirements of plate-based limiting dilution PCR methods and the low throughput and manual handling of current microchip methods. Almost 96 templates were analyzed in 25 min by use of ∼1 μL PCR reaction volume. Compared with digital PCR this operation was performed almost five times faster and using a PCR reaction volume a factor of 1 400 lower [57]. Small channel-to-channel differences in amplification were noticed, but these are potentially reducible by refinement of the heating procedure.

When transfer-messenger (tm) RNA purification, nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA), and real-time detection were integrated on a microfluidic device for the first time (Fig. 4), the chip was able to identify crude E. coli bacterial lysates in less than 30 min [59]. Cell lysis was performed off-chip, using a commercially available device. tmRNA, from 100 lysed E. coli cells, was purified by SPE using silica beads immobilized on the chip surface. Device clogging by debris, or bubble formation because of passage of air were avoided by immobilization of silica beads in a thin layer that leaves enough free space within the channel. RNA was eluted in 5-μL fractions by flow of deionized water through the silica bed chamber. The amplification used custom-designed high-selectivity primers and real-time detection was performed at 530 nm using molecular beacon probes (oligonucleotides with an FAM fluorophore at the 5′ end and a BHQ1 quencher at the 3′ end) [59].

Integrated microfluidic device for RNA purification and real-time NASBA. a Photograph of the device. Each chip can perform two separate reactions with the same reagents, but different samples, to incorporate controls. b Single-device architecture showing the distinct functional microfluidic modules: RNA purification chamber (RPC) and real-time NASBA chamber. (Reproduced, with permission, from Ref. [59])

An infrared temperature control system has been described for completely contactless temperature control PCR in microfluidic chips in a fluidic channel too small to enable conventional temperature control using thermocouple-based sensing [60]. The system comprised an IR pyrometer sensing the surface temperature above a PCR chamber. The design of the system ensured rapid equilibration between the PCR solution and the chamber surface [60]. For non-contact temperature control, the surface temperature relative to that of the PCR solution temperature was calibrated using the boiling point of water and an azeotrope within the chip. Successful PCR of a fragment of a Bacillus anthracis gene was performed by use of the described system [60].

For the first time, reverse transcription PCR has been performed on single-copy viral RNA in monodisperse isolated pico-droplet reactors using a fused-silica chip with hydrophobic coating. The device was coupled with an off chip valving system for generation of mono-disperse droplets with ∼70 nL volume [61]. RNA was isolated in monodisperse picoliter droplets emulsified in oil. In each droplet, real-time reverse transcription PCR with fluorescence detection of amplification was performed. After approximately 23 amplification cycles, RNA from 0.05–47 plaque forming units (pfu)/droplet was detected by real-time fluorescence [61]. The use of microdroplet technology limits the interaction between the microfluidic surface and PCR sample/reagents; this is responsible for PCR inhibition and carry-over contamination.

Several other manuscripts (Table 2) have reported fully integrated devices with impressive lowest amplified concentration, but a real μTAS is still in its research phase.

Separation techniques

On chip capillary electrophoresis (CE) is the most used separation technique. Detection is frequently achieved by fluorescence, although electrochemical methods involving amperometric detection [73] and contactless conductivity detection [74] have also been reported. Separations are performed on home-made, hybrid glass-polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [65, 73] chips or poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) chips [74–77]. A few applications use commercially available devices [75, 78, 79].

CE on chip has been used to quantify PCR products [65, 80], oxidative stress biomarkers in urine [73], hepatic cancer biomarkers in spiked serum [77, 81, 82], thrombin—a marker for various haemostasis-related diseases and conditions—in diluted plasma [76], viruses, for example human rhinovirus (HRV) or swine influenza virus [75, 78, 83], inflammatory biomarkers [84], and K-ras, the oncogene for mutations closely associated with colorectal cancer [79] (Table 3). The separation modes involved free-solution electrophoresis [73, 75, 77–79, 84], capillary gel electrophoresis (CGE) [65, 73–75, 80, 82, 86, 87], or affinity capillary electrophoresis [42, 77, 78, 81, 88].

CGE has been performed to resolve and investigate the abundance of proteins in complex samples in order to identify viruses and bacteriophages [89], to detect the presence of food-borne pathogenic bacteria in decayed food samples [80], or to analyse of RNA–RNA interactions [90], as alternatives to cell culture or PCR.

Several manuscripts report the use of on-chip transient isotachophoresis (ITP) to achieve preconcentration of analytes [82, 85, 88]. Using ITP, human serum albumin (HSA) and its immunocomplex with a monoclonal antibody were preconcentrated 800-fold [85] and 2000-fold [88] online on standard cross-channel PMMA microchips. Another interesting application uses an integrated nanoporous membrane to perform simultaneous concentration and detection of the inactivated swine influenza virus. Detection was achieved by coupling with a fluorescent labelled antibody. The fluorescent antibody complex was electrophoretically separated from the unbound antibody in 6 min by use of less than 50 μL clinical sample [83].

Intact protein separations from E. coli cell lysate have been performed on a two-dimensional microfluidic system with ten channels combining isoelectric focusing (IEF) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) [86]. Protein profiling was used for bacterial identification and characterization using a microchip separation platform [87]. The method is potentially universally applicable, especially for bio threat agents, and overcomes the disadvantages of PCR, i.e. high cost and the need for special working procedures to avoid contamination. The method includes four steps—the bacteria or spores are harvested and lysed, and the constituent proteins are solubilized, labelled with a fluorescent tag, and analyzed using chip gel electrophoresis (CGE). The protein fingerprints from the model organisms were used for bacterial identification or characterization.

Microchip LC coupled with MS has been reported for identification of autoantigens [91], defining a proteome signature for invasive ductal breast carcinoma [92], and biomarker screening applications in MCF-7 breast cancer cellular extracts [14]. A method very applicable in a clinical environment was also developed [92].

Immunoaffinity techniques

Affinity-based methods exploit the specific binding of biomolecules in order to isolate and characterize them in the presence of thousands of other compounds [93]. The main actors are antibodies, but aptamers, for example cell-surface receptors and oligonucleotides, are also valuable alternatives [94]. Low-molecular-mass aptamers have several advantages over antibodies—faster tissue penetration, longer shelf-life, sustaining reversible denaturation, lower toxicity, the possibility of being produced against targets such as membrane proteins, and use of highly automated technology [95].

A wide array of clinical diagnostic tests employs immunoassays and immunoblotting approaches [96]. Performing immunoassays on microfluidic devices has the advantages of high throughput, short analysis time, small volume and high sensitivity, and fulfils most of the important criteria for clinical diagnoses [97]. The main advantages of microfluidics as enabling technology has been clearly proved by several applications [77, 98, 99] with similar or improved performance compared with ELISA but much simpler and faster and with lower volumes. Future developments will increase even more the advantages over ELISA, creating fully integrated devices [100].

Analysis of inflammatory biomarkers, C-reactive protein (CRP), prostate-specific antigen (PSA), arginine vasopressin (AVP), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) cancer cells, and infection markers are just some of the clinically important applications currently implemented on microfluidic immunoassay chips. A chip has been used for rapid isolation and quantification of inflammatory biomarkers in microdissected areas of a skin biopsy. The biomarkers were isolated by immunoaffinity capture within the extraction port of the chip by use of a panel of 12 antibodies immobilized on a disposable glass fibre disk [84].

A specific aptamer, i.e. an oligonucleotide, has been used for highly selective capture and enrichment of arginine vasopressin (AVP) and possible diagnosis of immunological shock or congestive heart failure based on AVP quantification [101]. Trace amounts of AVP were enriched, eluted isocratically using a microfluidic platform, and detected label-free by coupled matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS). The aptamer–analyte binding was thermally disruptable enabling easy device regeneration [101].

Affinity-based isolation has enabled the first steps from the bench top to the clinic in the development of aptameric biosensors for cancer cells. Prostate tumour cells were successfully isolated and identified on a PMMA microchip [32]. The procedure managed to discriminate rare circulating prostate tumour cells resident in a peripheral blood matrix without staining, using antibodies and aptamers for prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) immobilized on the surface of a capture bed fixed within the chip [32]. Similarly, the efficacy of on-chip recognition and capture of breast cancer cells using an antibody-based microfluidic device has been reported [34]. The procedure used a biochip etched on to PDMS with the inner surface of the microchannels coated with epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) [34].

Applying the same principle but from a reversed perspective, virus-bound magnetic bead complexes have been used for rapid serological analysis of antibodies associated with an infection by the Dengue virus [30]. Dengue virus infection was confirmed by use of a microfluidic system that integrated one-way micropumps, a four-membrane-type micromixer, two-way micropumps, and an on-chip microcoil array [30]. Detection is achieved using fluorescence-labelled secondary antibodies. The procedure was performed automatically on a single chip within 30 min, which is a factor of eight faster than the traditional method. Also, the LOD (21 pg) was reduced by a factor of approximately 38 compared with the traditional method [30].

C-reactive protein (CRP), a general inflammation and cardiovascular disease risk assessment marker, has been detected in a one-step sandwich immunoassay using a fluorescence microscope [35]. Sample collection and immunoreaction were integrated on a microfluidic chip. CRP was detected from 5 μL human serum at concentrations of 10 ng mL−1 in less than 3 min, and after 13 min for concentrations below 1 ng mL−1 [35]. Another manuscript reported CRP assay in a simulated serum matrix by on-chip immunoaffinity chromatography [102]. CRP was fluorescently labelled in a one-step reaction and injected directly into the immunoaffinity capillary containing monoclonal anti-CRP attached to a 5.0-μm streptavidin-coated silica bead. The limit of detection was 57.2 ng mL−1 and chromatographic run times were less than 10 min [102].

An important step in the miniaturization and integration of laboratory operations in self-contained devices was made by designing a microfluidic chip for combinatorial library screening (Fig. 5) [25]. The chip was used to map a combinatorial peptide library of possible epitopes for anti-T7•tag antibody and anti-FLAG •tag antibody. The peptides were displayed on E. coli cells as insertions within an external loop of the outer membrane protein OmpX. The binding peptides were selected in several steps (Fig. 5). In the first step, the library was incubated off-chip with the target biotinylated antibodies. Cells with the binding peptides were captured on streptavidin-functionalized 5.6-μm polystyrene microspheres. In the second step, a disposable chip was used for serial dieletrophoresis activated cell sorting to separate cells with binding peptides from cells with non-binding peptides. The sorting was performed on the basis of size, in continuous-flow, with a sorting speed of more than 108 cells h−1. The antibody-binding target cells captured on microspheres were funnelled dielectrophoretically because of their different polarization [25]. In the third step, the collected beads with attached cells were grown overnight and the sorting in the second step was repeated. The DNA of the sorted cells was sequenced automatically to determine the sequence of the binding peptides. Cell library screening using microfluidic sorting was comparable with a combination of conventional cell sorting-methods, i.e. one round of sequential magnetic selection and two rounds of fluorescence activated cell sorting. The microfluidic sorting chip [25] had increased tolerance of flow disturbances and microbubbles and more robust purity performance using high cell concentrations at the inlet. The authors also mention a possibility of increased throughput by optimization of chip architecture, using parallel channels fabricated on a single chip. The technique could be further developed to monitor polyclonal signatures of serum antibodies for disease profiling, for other affinity-based screening using substrate-functionalized beads, and for automated reagent generation, wherein ligands for a given protein or cell type could be discovered using self-regenerating libraries.

Schematic depiction of antibody fingerprinting using a microfluidic sorting device, cassette B (not to scale). Left: Micrograph of the sorting device in operation showing the first sorting stage. Right: Micrograph of the second stage at the collection point. (Reproduced, with permission, from Ref. [25])

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) has been rapidly and sensitively quantified in human serum samples using an immunosensor coupled to a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) modified with multiwall carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) (CNT–GCE) integrated with microfluidic systems [103]. PSA was captured immunologically with the immobilized anti-tPSA and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) enzyme-labelled second antibodies specific to PSA. The detection relies on back electrochemical reduction of 4-tert-butylcatechol catalyzed by HRP in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. The procedure had an LOD of 0.08 μg L−1 when electrochemical detection was used [103].

A new approach to immunoblotting combines on-chip integration of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) with subsequent in-situ immunoblotting [98]. The manuscript reports “hands free” electrophoretic transfer of resolved species to a blotting membrane as a directed, efficient method for protein identification without a need for pressure-driven flow and valving [98]. alpha-Actinin and PSA were identified and quantified from multi-protein samples in the 101–105 nmol L−1 range with LODs of 0.05 pg and 1.8 pg, respectively. Moreover, detection sensitivity was enhanced approximately fivefold by target protein enrichment on the blotting membrane [98].

An interesting application of affinity-based methods is the development of encoded microbeads. These are smart microstructures with both molecular recognition ability and build-in codes for rapid microbeads identification [104]. The codes can be optical, electronic, graphical, or physical signatures creating combinations similar to the black and white stripes of traditional bar codes [105, 106]. The most popular approach uses combinations of quantum dots (QDs) to generate fluorescent codes. QDs are inorganic nano-crystals with fluorescent properties which depend on both their composition and size [106]. They have several amazing properties, for example high fluorescence yield, remarkable stability, and extremely narrow emission, enabling many non-overlapping colours to be used simultaneously [106]. Moreover, the use of the encoded microbeads can add multiplexing capability to the assay by enabling multi-analyte analysis [97].

Detection schemes

Optical detection schemes are still the favourite choice for measurements in microfluidic systems [107–109]. There are two major approaches—coupling of the macro-scale optical infrastructure as “off-chip approach” or integration of micro-optical functions on to microfluidic devices as “on-chip approach” [110]. Several solutions for integration, for example planar waveguides, coupling schemes to the outside world, evanescent-wave based detectors, and optical fluidics integration problems, and perspectives and limitations of these different solutions have been discussed in detail [107]. Irrespective of the detection approach, the LODs achieved are profoundly affected by sensor size and shape, because of analyte transport limitations rather than signal transduction limitations [110]. Production of inexpensive, sensitive, and portable optical detection systems is, therefore, currently of major importance in the manufacture of commercial devices for portable diagnostic devices [108].

Laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) is the most popular detection technique in microchip-based applications. Because the number of fluorescent analytes is rather limited, a derivatization step with a fluorescent dye is usually involved [42, 51, 65, 89, 111]. Unlike UV detection, an alternative to “diode array detectors” enabling simultaneous data acquisition at multiple wavelengths is not that accessible for fluorescent detection. Fluorescent detectors are bulky and expensive. In some cases, the ability to combine the available detection technology with the most appropriate label is a real challenge, but also the labelling itself is a major analytical burden. In many cases the detection relies on measurement of fluorescence intensity, performed by capturing the signal with a CCD camera coupled to a fluorescence microscope and followed by graphical analysis of the captured images. For instance, CCD cameras have been used to monitor, capture, and specifically isolate viruses and bacteria [112, 113], to control DNA hybridization [114], to type Staphylococcus aureus strains [115], to quantify proteins after separation [98], or to screen and identify new serological biomarkers for inflammatory bowel disease [62].

As fluorescent probes, fluorescein’s derivatives are still extremely popular [89, 116–119], but the cyanine family (Cy)dyes [75, 120, 121] and Alexa Fluor type dyes [31, 33, 120, 122, 123] are also used. In most immunoassays, the detection problem is solved by using fluorescent labelled antibodies. The use of fluorophores with higher intensity yield, for example QDs, has enabled visualisation of HIV after capture on a microfluidic device using only a standard 10× fluorescence microscope [47]. Similarly, the use of QD probes resulted in 30-fold signal amplification, which implied a reduction in observed limits of detection by nearly two orders of magnitude [124].

A combination of two dyes with different colours has been used to study Vaccinia virus infection [51]. A blue fluorescent cell-permeable DNA counterstain dye and a green-fluorescent cell-permeable lipophilic dye were used [51]. Evolving to more complex hardware, a two-colour detection system was incorporated for the first time into a CE–LIF chip to measure simultaneously fluorescence from reference standards (650 nm) and the analyte (450 nm) in the sample [89]. This approach enabled location of standard peaks without interference from sample or background peaks [89].

Fluorescence detection has the advantage of sensitivity, but the derivatization steps required are a major drawback. Alternatives enabling label-free detection are, therefore, always of interest. When an immediate answer from an unprocessed sample is needed, fluorescence detection is of limited value. To combine the advantages of fluorescence with label-free detection, the gene for green fluorescent protein has been incorporated into the Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) genome to monitor the infection on a chip [125].

Another approach enabled rapid detection of bacteria by monitoring off-chip bioluminescence [126]. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) extracted from bacterial cells was treated with luciferin to induce the bioluminescence reaction of firefly, luciferin-ATP [126].

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) tends to be the method of choice for label-free optical detection as an alternative to fluorescence. The technique detects variations in refractive index by observing changes in an optimum plasmon coupling angle or wavelength when binding occurs at metal–dielectric interfaces. The main disadvantage of this technique is the non-specific measure for mass accumulation, thus any change due to non-specifically loaded molecules cannot be differentiated from the target [127]. In case of surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), the absorption and scattering of properties of metallic nanoparticles enable their use as enhanced chromophores in molecular labelling [128]. In this way, the disadvantages of SPR are overcome. SERS applications for microfluidic devices are described in detail elsewhere [127]. The technique has been used to identify Dengue virus serotype 2 on chip at levels higher than 30 pmol L−1 and with excellent specificity against other serotypes [129].

The combination of liquids and optics in the same physical volume is one way to enrich the functionality of the sensors [123]. Qβ phages have been detected and monitored on an optofluidic chip using anti-resonant reflecting optical waveguides [123]. Time-dependent fluorescence correlation spectroscopy data were used to calculate diffusion coefficients, flow velocities, and concentrations of viruses. The device can also be used as an inexpensive and portable sensor capable of discriminating between viruses of different sizes. The technique is sensitive to picomolar concentrations and can be used to detect and distinguish fluorescent objects in the size range of viruses, e.g. phages of 26 nm [123].

Electrochemical detection is an alternative with growing popularity. It is sensitive, compatible with a wide array of biochemical reactions, and easily miniaturized. There are three possibilities: voltammetric, conductometric, and potentiometric detection. This detection approach is not affected by scale reduction and has an excellent performance even when micrometer-size electrodes are employed. An overview of the available approaches is given elsewhere [130]. Several interesting applications using electrochemical detection, SERS, and SPR are listed in Table 4.

Mass spectrometry (MS) enables detailed qualitative and quantitative assessment of cellular biomarkers with high sensitivity and reliability. The fabrication of mass spectrometers and interfaces between microfluidic platforms and MS detectors on micro and nano scales is currently one of the most investigated topics [140–142]. The reduction in scale brings advantages such as improved process control and automation, shorter analysis times (minutes or seconds), reduced sample consumption, amenability to multiplexing and high-throughput processing, and lower analysis costs [9, 140–142]. Unfortunately, MS requires multi-step sample pre-treatment procedures, sometimes including liquid chromatographic (LC) separations [14]. Two main MS strategies are currently successfully implemented for quantitative proteomics, namely label-free and stable isotope labelling. These strategies are described in detail elsewhere [140–142].

Analysis of a complex cellular extract on a fully integrated microfluidic system using MS detection has been reported [14]. Proteins from breast cancer cellular extracts were tryptically digested, cleaned from salts and labelled with an isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) reagents. Bovine proteins were also added to the sample as standards. The separation was performed using a glass microchip LC–MS, designed in-house and enclosing four distinctive functional elements including a pump, a sampling valve, a separation channel, and an electrospray ionization (ESI) interface. Mobile phase propulsion through the LC channel and ESI interface was achieved by EOF pumping. The pumping unit consisted of two arrays of 200 microchannels, each of 2 cm length and 1.5–1.8 μm depth, connected in parallel. The large number of channels ensured sufficient flow rate and the small size resulted in sufficient hydraulic resistance to pressurize a back-flow leakage. The EOF generated in the multichannels pump ensured mobile phase propulsion. The valving had a similar design. Separation was performed in a channel packed with 5 μm Zorbax C18 particles. Sample injection was performed electrokinetically and a gradient was generated to perform the separation. Quantitative analysis of an entire protein extract has been performed without any sample pre-fractionation and differential protein expression analysis in MCF-7 cells cultured in the presence of β-oestradiol and tamoxifen [14]. The chip enabled reliable identification of 40–50 proteins and, in another experiment, was able to identify five proteins of several previously reported human putative cancer biomarkers that were up or downregulated [14].

Challenges and trends

Researchers developing applications or techniques useful for molecular diagnosis employing microfluidics are facing challenges at three levels—the device level, the sample level, and the application level.

Challenges at the device level

The device itself is a source of challenges resulting from design, fabrication and operation. Several commercial solutions are available, but home-made adapted devices are very popular and it is impressive to see that the creativity of researchers has no boundaries. In the academic world, lack of funds sometimes results in good brain activity. However, in several cases, the enthusiasm of researchers leads to complicated solutions, which are not tested for reproducibility and enlarge the gap between academia and industry.

The devices are fabricated in various ways, and fabrication is a significant part of microfluidics-related manuscripts. Artificial polymers, PDMS [33, 36, 51, 113, 114, 125, 143–145], PMMA [47, 77, 80, 132] or cyclic polyolefin [40, 99] are the materials of choice for mass production and most home-made applications. Polymers have a “Jekyll and Hyde” character in comparison with other material classes [146]. They have several advantages, i.e. are biocompatible and UV–visible transparent, and their use enables relatively inexpensive fabrication of complex micro and nanostructures, with high reproducibility. Moreover, huge numbers of materials and methods are available for microstructure fabrication. Selection of the appropriate material and microfabrication method for a given application is, therefore, extremely difficult, especially for scientists unfamiliar with polymer chemistry. This explains why the scientific literature is dominated by a few favourite materials only [146].

Polymeric materials can also be a source of challenges, especially those containing polyimide, which is incompatible with aggressive steps that might occur during manufacture [147]. A modular approach has been used for manufacturing an electrical biosensor composed of single-stranded modified DNA probe used to perform simultaneous monitoring and differentiation of DNA sequence representatives of PCR amplicons derived from human (H1N1) and avian (H5N1) influenza. Initially, the electrode and chamber substrates were individually processed; the two substrates were then bonded to complete the processing of the device. The modular approach was a solution to the relatively harsh conditions occurring as a result of the use of sulfuric acid for in situ cleaning and preparation of the electrodes [147].

The design of the device should be kept as simple as possible to enable mass production, but sometimes it is problematic to control the accurate delivery of many reagents simultaneously, to ensure adequate mixing, and to avoid contamination. Some researchers have managed to find simple solutions, for example integration of separate reservoirs for sample and reference solutions [77], hence reducing the number of washing steps and the risks of contamination. A simple solution has been described in which magnetic beads used throughout the application were effectively retained by placing a magnet on a side of the chip [126].

Although technological advances in recent decades have enabled ready access to micro-components, fabrication on a micrometer scale (typical surface areas for micro-electromechanical systems are 100–10.000 μm2 [120]) with or without the use of biological reagents is a challenge that cannot be neglected. When surfaces are functionalized with biological macromolecules, supplementary aspects such as biomolecule stability and compatibility also become critical. A wide range of biomolecules have been immobilized on the inner surfaces of devices, e.g. anti-Micoplasma pneomoniae antibodies [148], anti-gp120 antibodies [47], anti-AFP antibodies [77], bacterial cells [149], DNA [114, 147], H1N1 probe [147], and Hsp60 [113]. A microspotting tool has been reported for sequential deposition of biomolecules at the same location on an active surface [120]. The technique enables proper coating of the sensing surface with bioactive layers and parallel deposition of three different biomolecules in a single run [120]. Another technique, the “layer-by-layer” (LbL) technique [150], enables polyelectrolyte coatings to be applied to the surface of digitally encoded microcarriers. The coating of microcarriers with antibodies, and the use of the coated microcarriers as capturing agents, have been reported [150].

Microfluidic devices are characterized by large surface area-to-volume ratios. Large capillary forces are hence generated, which may drive fluids into unwanted areas of the device, risking contamination of other fluid streams. Within the channels, the mixing of liquids can only be performed by diffusion, because of the laminar flows. To perform adequate mixing, long channels are needed. A new membrane-type micromixer has been described [112]. Mixing was achieved by injecting compressed air controlled by an electromagnetic valve (EMV). The micromixer was used in the process of incubation of the viral samples and the magnetic beads [112]. Other approaches for mixing liquids include the use of centrifugal force and capillary action [114], and magnetic force [151].

Real sample analysis involves the complete integration of sample preparation, and analyte separation and detection [19]. Several manuscripts have reported integrated detection devices, for example a miniature laser-induced fluorescence detection module [89], a prototype of an integrated fluorescence detection system, and an optical fibre light guide on a laminate-based multichannel chip [117], and even a new design of a controllable micro-lens structure capable of enhancing an LIF detection system [116].

Challenges at the sample level

Bioanalytical samples are well known for their complexity, i.e. often a large number of different molecules is present over wide ranges of concentration in different matrices. Moreover, available sample volumes are usually low, i.e. in the microlitre range. Also, biological colloids, for example macromolecular solutions and viral or bacterial suspensions, are known for wide distributions of charges, sizes, and shapes, which can be affected also by the experimental conditions. Compared with these, small-molecule species are a homogenous population composed of virtually identical entities. The distribution of analyte properties will generate a distribution of electrophoretic mobilities, for example, when capillary electrophoresis is used as separation technique. This is one of the causes of the broad and often irregular peak shapes sometimes obtained for samples of biological origin [152].

Occasionally, the non-uniformity of analyte properties requires alternative solutions, for example use of an asymmetric electrical field for electrophoretic separations. Dielectrophoresis was the solution found for separation of cells or particles, when the large size variations turned into a separation asset [36, 51, 113, 144].

Wall interactions are another common problem for samples of biological origin, especially for protein-containing samples. BSA-FITC has been used as model protein to demonstrate how protein molecules are adsorbed and distributed on the inner wall surface of the PMMA microchannel [132]. The surface of the channels was initially coated with polyethyleneimine (PEI) containing abundant amino groups to covalently immobilize AFP monoclonal antibody. BSA–FITC binding within the channels was then studied to enable optimization of the system to reduce non-specific binding, and quantification of AFP was achieved with LOD down to 1 pg mL−1. The utility of the chip to detect AFP from healthy human serum was demonstrated [132].

Gonzales et al. [153] studied the adsorption of major polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mixture components on the capillary channel wall. None of the polymeric materials or flow velocities tested was found to affect subsequent PCR amplification. PCR inhibition occurred only after exposure of the mixture to tubing lengths of 3 m or when the sample volume was reduced. Individual testing of PCR products revealed significant DNA adsorption and an even greater adsorption of the fluorescent dye used. These findings imply that adsorption of reaction components by wall surfaces is responsible for inhibition of PCR in polymeric tubing. These phenomena increase substantially with increasing tubing lengths or with sample volume reduction, but not with contact times or typical flow velocities for dynamic PCR amplification [153]. These results indicate the need for careful consideration of chemical compatibility between polymeric capillaries and DNA dyes when quantitative microfluidic devices are developed [153].

Challenges at the application level

Development of applications is usually focused on maintaining the stability of samples and reagents, preventing false-positive results because of non-specific binding, increasing precision, and reducing the LOD.

To avoid non-specific binding, more sensitive and selective approaches are used for the design of devices. Molecular-imprinted polymers (MIP), for instance, are artificial recognition materials designed to interact noncovalently with the analyte. A cross-linked polymer containing highly selective recognition sites created by means of soft-lithography has been used for specific recognition of viruses [154, 155]. The shape and surface chemistry of the MIP facilitated highly specific interaction with the virus, and non-specific interactions were thus eliminated [154, 155].

In some cases, the applications are more than routine analyses such as separation, identification, or assay—for instance, a device used for cell growth and on-chip infectivity assay of swine influenza virus [125].

Trends

The huge number of research projects on the development of portable diagnostics is an objective means of quantifying the great expectations of microfluidics in the molecular diagnosis field.

Paper is increasingly regarded as a promising support for inexpensive, portable, fully disposable, and easy to use devices for complicated molecular diagnostics—as easy to interpret as the home-used pregnancy test. Photolithography can be used to build selectively hydrophobic barriers in the filter paper, enabling the hydrophilic paper channels to control the transport of aqueous solutions by capillary forces without the need for external pumping [156]. Several other research groups focused on the calibration of paper-based microfluidic devices [157], on the techniques used to generate hydrophilic channels in filter paper [158], on the application of electrochemical detection [159], or on the development of a hand-held optical colorimeter [160].

Use of microfluidic devices gives deeper insight into the life sciences and medicine because it enables, for instance, study of the proteins in a single cell [161], quantification of multiple proteins in a single sample [33, 162], identification of a single nucleotide polymorphism [135], or detection below the limits of classical methods, for example the “bio-bar code” assay [163–165]. The “bio-bar code” assay (Fig. 6) uses two types of functionalized particles:

-

1.

magnetic particles functionalized with recognition elements, i.e. monoclonal antibodies or a hapten-modified oligonucleotide; and

-

2.

gold nanoparticles functionalized with a second recognition element and a bifunctional oligonucleotide bar-code DNA [2].

Biobar code assay developed for quantification of PSA in patient serum. Schematic representation of the PSA Au–NP probes (A) and the PSA bio-barcode assay (B). For details, see text (reproduced with permission from Ref. [166])

The analyte of interest, the target, usually a protein, is initially captured and enriched by the magnetic microparticle (Fig. 6). Further, the target is sandwiched between magnetic microparticle and the gold nanoparticles. The sandwiches are easily separated from the sample in a magnetic field. In a further step, the DNA of the bar code is released by heating. Signal amplification is achieved because for each target recognition thousands of bar-codes are released. Half of the released DNA is detected by use of a scanometric assay based on the affinity of the released DNA for a complementary “universal” scanometric gold nanoparticle DNA probe. The other part is complementary to the chip immobilized DNA, responsible for sorting and binding barcodes complementary to the target sequence. The concept has unparalleled sensitivity for target detection, i.e. it can be between one and six orders of magnitude more sensitive than conventional ELISA. By use of this method, PSA was measured in the serum of patients after radical prostatectomy, even in cases when the available immunoassays were not able to detect it [166].

At the crossroad of four major scientific fields, i.e. biology, physics, chemistry, and medical science, biosensors are one of the most studied subjects of recent years. Although significant progress has been achieved, and analysis at the single-molecule level [5] or based on single-cell composition [161, 167] is possible, viable solutions for real-time, bedside diagnostic devices are still awaited.

Recent progress in technology opens the way toward mass production of biosensors and bedside devices. The use of polymeric materials for fabrication of microfluidic systems will simplify manufacturing processes [168]. New transducing and biocompatible interfaces are expected to be developed based on composites which integrate nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and nanoengineered “smart” polymers [168]. The difficulty in producing low-cost, sensitive, and portable optical detection systems limits the number of the commercial devices for bedside diagnostics, but several technological solutions for biomolecule-compatible optofluidic integration have already been described [169].

Linder [170] has described two types of technology expected to extend the use of microfluidic devices outside clinical laboratories, i.e. amplification chemistry that results in the accumulation of an opaque material at the surface of reaction site, and a solution for long-term storage of multiple reagents and for the sequential delivery of the reagents to the reaction site inside a microfluidic device. Innovative techniques involving nanoengineered materials have been used to develop potentially less expensive detection systems without alignment requirements, without miniaturization disadvantages, and which are more readily adapted for bedside use [108]. The combination of progress in technology and the life sciences brings us one step closer to microfluidic devices with higher sensitivity, and improved biocompatibility and stability of the immobilized molecules, which makes them feasible biosensors and bedside devices.

The use of protein biomarkers for development of micro-electrical sensors, and the underlying technical concepts, have been described [171]. Similarly, emerging optical and microfluidic technology suitable for bedside genetic analysis systems [169] and DNA biosensors [172] have been reviewed. Some early stage commercial products based on electrochemical DNA biosensors integrated in analytical microfluidic devices have also been reported [172].

There is currently a discrepancy between the molecular based diagnostic tests approved by regulatory agencies such as the FDA (Table 5) within the last three years, and the literature and the available technology. The approved tests are rather traditional, and mostly based on immunoassays. Several tests use PCR for confirmation of viral infection, cancer diagnosis, and for prognosis or diagnosis of genetic diseases, for example cystic fibrosis in new-borns (Table 5). Still, compared with the number of published papers (hundreds or even thousands) FDA-cleared diagnostic devices involving microfluidics are restricted mostly to immunochromatographic assays to confirm several viruses and bacteria, and several other devices intended for measurement of cholesterol level in blood control or for glycaemic control in people with diabetes. All the other tests make use of highly specialized reagents and equipment. The whole situation is even more contradictory if we consider that more than hundred companies are producing and commercializing miniaturized analytical devices [173].

According to a study published by Analytical Chemistry [8], microfluidics is now at the “slope of enlightenment” stage of the Gartner hype cycle model of the life cycle of technology (Fig. 7a). If the yearly change in papers published on microfluidics (Fig. 7b) is considered, it is clear that major events in science and technology also acted as triggers for microfluidics. The technology was redefined, a new cycle started, more powerful applications were defined, and deeper insight was obtained.

Concluding remarks

Microfluidics are currently among the most fashionable research topics. Much of the research exploits the advantages of microfluidics to solve current problems in bioanalysis, e.g. small volumes, limited stability, and high cost. An overwhelming number of manuscripts is devoted to trying to extend research findings into routine clinical use.

However, only a few diagnostic devices are available commercially, and the increase in the number of registered devices is not following the number of published papers or funding of biomarker analysis on microfluidic platforms. There are two different views on the evolution of these devices: the optimistic view is that microfluidics will become a integral part of the future of bioanalysis; the pessimistic view is that microfluidics will remain a niche preoccupation for research without any practical consequences [8].

Although a “killer application” has not yet been developed [8], small steps towards it are taken every day. The beginning is complete, and applications, for example MammaPrint (Table 5), that uses a microfluidic platform to give a prognosis of the future evolution of breast cancer, will increasingly become part of our life. Technically, applications within the life sciences are increasingly trying to resemble the world depicted in ’70s–’80s science fiction movies: devices were always small (handheld), incredibly sleek, and provided all the information necessary at a moment’s notice [173]. Use of microfluidics devices in life science and medicine have revealed new perspectives and enabled deeper investigation, but they have still to find their way to more generalized and commercialized applications.

References

Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2008) Molecular biology of the cell, 5th edn. Garland Science, New York

Giljohann DA, Mirkin CA (2009) Drivers of biodiagnostic development. Nature 462:461–464

Tothill IE (2009) Biosensors for cancer markers diagnosis. Semin Cell Dev Biol 20:55–62

Rosi NL, Mirkin CA (2005) Nanostructures in Biodiagnostics. Chem Rev 105:1547–1562

Shen YP, Wui BL (2009) Microarray-based genomic DNA profiling technologies in clinical molecular diagnostics. Clin Chem 55:659–669

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ (2006) Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 367:1747–1757

Fields S (2001) The interplay of biology and technology. PNAS 98:10051–10054

Mukhopadhyay R (2009) Microfluidics: on the slope of enlightenment. Anal Chem 81:4169–4173

Manz A, Graber N, Widmer HM (1990) Miniaturized total chemical analysis systems: a novel concept for chemical sensing. Sensors and Actuators: B Chemical 1:244–248

Arata HF, Kumemura M, Sakaki N, Fujita H (2008) Towards single biomolecule handling and characterization by MEMS. Anal Bioanal Chem 391:2385–2393

Amur S, Frueh FW, Lesko LJ, Huang SM (2008) Integration and use of biomarkers in drug development, regulation and clinical practice: a US regulatory perspective. Biomark Med 2:305–311

Weigl B, Domingo G, LaBarre P, Gerlach J (2008) Towards non- and minimally instrumented, microfluidics-based diagnostic devices. Lab Chip 8:1999–2014

Sorger PK (2008) Microfluidics closes in on point-of-care assays. Nat Biotechnol 26:1345–1346

Armenta JM, Dawoud AA, Lazar IM (2009) Microfluidic chips for protein differential expression profiling. Electrophoresis 30:1145–1156

Cheng XH, Chen G, Rodriguez WR (2009) Micro- and nanotechnology for viral detection. Anal Bioanal Chem 393:487–501

Han J, Fu J, Wang YC, Song YA (2008) Biosample preparation by Lab-on-a-chip devices. In: Li D (ed) Encyclopedia of microfluidics and nanofluidics. Springer, Berlin

Mark D, Haeberle S, Roth G, von Stetten F, Zengerle R (2010) Microfluidic lab-on-a-chip platforms: requirements, characteristics and applications. Chem Soc Rev 39:1153–1182

Squires TD, Quake SR (2005) Microfluidics: fluid physics at the nanoliter scale. Rev Mod Phys 77:977–1026

Mariella R Jr (2008) Sample preparation: the weak link in microfluidics-based biodetection. Biomed Microdevices 10:777–784

Lai JJ, Nelson KE, Nash MA, Hoffman AS, Yager P, Stayton PS (2009) Dynamic bioprocessing and microfluidic transport control with smart magnetic nanoparticles in laminar flow devices. Lab Chip 9:1997–2002

Lien KY, Lin JL, Liu CY, Lei HY, Lee GB (2007) Purification and enrichment of virus samples utilizing magnetic beads on a microfluidic system. Lab Chip 7:868–875

Morozov VN, Groves S, Turell MJ, Bailey C (2007) Three minutes-long electrophoretically assisted zeptomolar microfluidic immunoassay with magnetic-beads detection. J Am Chem Soc 129:12628–12629

Lien KY, Lee WC, Lei HY, Lee GB (2007) Integrated reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction systems for virus detection. Biosens Bioelectron 22:1739–1748

Bunyakul N, Edwards KA, Promptmas C, Baeumner AJ (2009) Cholera toxin subunit B detection in microfluidic devices. Anal Bioanal Chem 393:177–186

Bessette PH, Hu X, Soh HT, Daugherty PS (2007) Microfluidic library screening for mapping antibody epitopes. Anal Chem 79:2174–2178

Lien KY, Liu CJ, YF LYC, Kuo PL, Lee GB (2009) Extraction of genomic DNA and detection of single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping utilizing an integrated magnetic bead-based microfluidic platform. Microfluid Nanofluidics 6:539–555

Maeng JH, Lee BC, Ko YJ, Cho W, Ahn Y, Cho NG, Lee SH, Hwang SY (2008) A novel microfluidic biosensor based on an electrical detection system for alpha-fetoprotein. Biosens Bioelectron 23:1319–1325

Maeng Ko YJ, JH AY, Hwang SY, Cho NG, Lee SH (2008) Microchip-based multiplex electro-immunosensing system for the detection of cancer biomarkers. Electrophoresis 29:3466–3476

Huang H, Zheng XL, Zheng JS, Pan J, Pu XY (2009) Rapid analysis of alpha-fetoprotein by chemiluminescence microfluidic immunoassay system based on super-paramagnetic microbeads. Biomed Microdevices 11:213–216

Lee YF, Lien KY, Lei HY, Lee GB (2009) An integrated microfluidic system for rapid diagnosis of dengue virus infection. Biosens Bioelectron 25:745–752

Choi S, Chae J (2009) A microfluidic biosensor based on competitive protein adsorption for thyroglobulin detection. Biosens Bioelectron 25:118–123

Dharmasiri U, Balamurugan S, Adams AA, Okagbare PI, Obubuafo A, Soper SA (2009) Highly efficient capture and enumeration of low abundance prostate cancer cells using prostate-specific membrane antigen aptamers immobilized to a polymeric microfluidic device. Electrophoresis 30:3289–3300

Diercks AH, Ozinsky A, Hansen CL, Spotts JM, Rodriguez DJ, Aderem A (2009) A microfluidic device for multiplexed protein detection in nano-liter volumes. Anal Biochem 386:30–35

Du Z, Cheng KH, Vaughn MW, Collie NL, Gollahon LS (2007) Recognition and capture of breast cancer cells using an antibody-based platform in a microelectromechanical systems device. Biomed Microdevices 9:35–42

Gervais L, Delamarche E (2009) Toward one-step point-of-care immunodiagnostics using capillary-driven microfluidics and PDMS substrates. Lab Chip 9:3330–3337

De La Rosa C, Tilley PA, Fox JD, Kaler KVIS (2008) Microfluidic device for dielectrophoresis manipulation and electrodisruption of respiratory pathogen Bordetella pertussis. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 55:2426–2432

Chen X, Cui DF, Liu CC (2008) On-line cell lysis and DNA extraction on a microfluidic biochip fabricated by microelectromechanical system technology. Electrophoresis 29:1844–1851

Lee EZ, Huh YS, Jun YS, Won HJ, Park HYK, TJ LSY, Hong WH (2008) Removal of bovine serum albumin using solid-phase extraction with in-situ polymerized stationary phase in a microfluidic device. J Chromatogr A 1187:11–17

Doebler RW, Erwin B, Hickerson A, Irvine B, Woyski D, Nadim A, Sterling JD (2009) Continuous-flow, rapid lysis devices for biodefense nucleic acid diagnostic systems. JALA Charlottesv Va 14:119–125

Bhattacharyya A, Klapperich CM (2008) Microfluidics-based extraction of viral RNA from infected mammalian cells for disposable molecular diagnostics. Sens Actuators B Chem 129:693–698

Mandal S, Goddard JM, Erickson D (2009) A multiplexed optofluidic biomolecular sensor for low mass detection. Lab Chip 9:2924–2932

Reichmuth DS, Wang SK, Barrett LM, Throckmorton DJ, Einfeld W, Singh AK (2008) Rapid microchip-based electrophoretic immunoassays for the detection of swine influenza virus. Lab Chip 8:1319–1324

Cho YK, Kim S, Lee K, Park C, Lee JG, Ko C (2009) Bacteria concentration using a membrane type insulator-based dielectrophoresis in a plastic chip. Electrophoresis 30:3153–3159

GmbH PreAnalytiX (2009) PAXgene® blood mini RNA kit handbook. PreAnalytiX GmbH, Hombrechtikon

Mahalanabis M, Al-Muayad H, Kulinski MD, Altman D, Klapperich CM (2009) Cell lysis and DNA extraction of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria from whole blood in a disposable microfluidic chip. Lab Chip 9:2811–2817

Cho YK, Lee JG, Park JM, Lee BS, Lee Y, Ko C (2007) One-step pathogen specific DNA extraction from whole blood on a centrifugal microfluidic device. Lab Chip 7:565–573

Kim YG, Moon S, Kuritzkes DR, Demirci U (2009) Quantum dot-based HIV capture and imaging in a microfluidic channel. Biosens Bioelectron 25:253–258

McKenzie KG, Lafleur LK, Lutz BR, Yager P (2009) Rapid protein depletion from complex samples using a bead-based microfluidic device for the point of care. Lab Chip 9:3543–3548

Qin L, Vermesh O, Shi Q, Heath JR (2009) Self-powered microfluidic chips for multiplexed protein assays from whole blood. Lab Chip 9:2016–2020

Moon HS, Nam YW, Jae CP, Jung HI (2009) Dielectrophoretic separation of airborne microbes and dust particles using a microfluidic channel for real-time bioaerosol monitoring. Environ Sci Technol 43:5857–5863

Park K, Akin D, Bashir R (2007) Electrical capture and lysis of vaccinia virus particles using silicon nano-scale probe array. Biomed Microdevices 9:877–883